#motorbus

Text

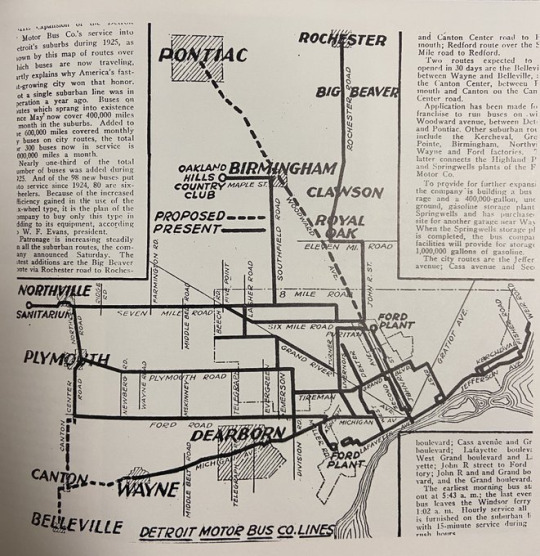

Map: Detroit Suburban Bus Service 1925

Detroit hasn’t always been a bus city (which I guess is still questionable based on current bus performance). David Gifford shared this map from Book 3, When Eastern Michigan Rode The Rails by Schramm, Henning and Andrews. In 1925, the Western suburbs really stand out with multiple bus lines stretching across Wayne County. There was similar heavy bus service in the Westside of Detroit, but not…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another dimension of improvement was speed. By 1870 intercity trains traveled at 25 miles per hour and horse-drawn streetcars with their six-mile per hour pace were beginning to replace less efficient horse-drawn omnibuses that traveled only half as fast. Within a few years the horse-drawn streetcar was replaced by the electric streetcar and the motorbus. All of a sudden in the 1890s and 1900s appeared the Chicago elevated and the New York City subway system, with similar improvements in many other cities.

None of the transportation inventions of the 1870-1900 period were more important than the automobile. Prior to its invention, there was almost no chance for travel by working class families either from the farm to the city, or from the city to the countryside. Ownership of horses and carriages was a privilege limited to the rich and the elite. The automobile changed all that, and even more for farmers than city residents; by 1926 fully 93 percent of Iowa farmers owned motor cars. The range of indirect benefits provided by the automobile is suggested in this quote from Flink (1972, p. 460):

"The benefits of automobility were overwhelmingly more obvious: an antiseptic city, the end of rural isolation, improved roads, better medical care, consolidated schools, expanded recreational opportunities, the decentralization of business and residential patterns, a suburban real estate boom, and the creation of a

standardized middle-class national culture."

IS U.S. ECONOMIC GROWTH OVER? FALTERING INNOVATION CONFRONTS THE SIX HEADWINDS by Robert J. Gordon (NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH)

0 notes

Photo

a motorbus

“A motorbus on flanged wheels runs between Cusco and Machu Picchu.”

October 1950

Quote taken from original text included with the image in the magazine

0 notes

Text

“Motorbus Change”

Cram yourself into “The People’s Chariot” and go for a ride to the end of the line. Listen to Motorbus Change on Apple Music, and don’t forget your bus pass next time.

LINK: music.apple.com/ca/album/motorbus-change/1669403955

View On WordPress

#computer music#electronic music#future music#Music#music production#new music#sexy singles#single#techno

0 notes

Text

A bus (contracted from omnibus with variants multibus, motorbus, autobus, etc.) is a road vehicle that carries significantly more passengers than an average car or van. It is most commonly used in public transport, but it is also in use for charter purposes, or through private ownership. Although the average bus carries between 30 and 100 passengers, some buses have a capacity of up to 300 passengers. The most common type is the single-deck rigid bus, with double-decker and articulated buses carrying larger loads, and midibuses and minibuses carrying smaller loads. Coaches are used for longer-distance services. Many types of buses, such as city transit buses and inter-city coaches, charge a fare. Other types, such as elementary or secondary school buses or shuttle buses within a post-secondary education campus, are free. In many jurisdictions, bus drivers require a special large vehicle license above and beyond a regular driving license.

Buses may be used for scheduled bus transport, scheduled coach transport, school transport, private hire, or tourism; promotional buses may be used for political campaigns and others are privately operated for a wide range of purposes, including rock and pop band tour vehicles.

Horse-drawn buses were used from the 1820s, followed by steam buses in the 1830s, and electric trolleybuses in 1882. The first internal combustion engine buses, or motor buses, were used in 1895. Recently, interest has been growing in hybrid electric buses, fuel cell buses, and electric buses, as well as buses powered by compressed natural gas or biodiesel. As of the 2010s, bus manufacturing is increasingly globalised, with the same designs appearing around the world.

The name 'Bus' is a shortened form of the Latin adjectival form omnibus ("for all"), the dative plural of omnis/omne ("all"). The theoretical full name is in French voiture omnibus ("vehicle for all"). The name originates from a mass-transport service started in 1823 by a French corn-mill owner named Stanislas Baudry in Richebourg, a suburb of Nantes. A by-product of his mill was hot water, and thus next to it he established a spa business. In order to encourage customers he started a horse-drawn transport service from the city centre of Nantes to his establishment. The first vehicles stopped in front of the shop of a hatter named Omnés, which displayed a large sign inscribed "Omnes Omnibus", a pun on his Latin-sounding surname, omnes being the male and female nominative, vocative and accusative form of the Latin adjective omnis/-e ("all"), combined with omnibus, the dative plural form meaning "for all", thus giving his shop the name "Omnés for all", or "everything for everyone".

His transport scheme was a huge success, although not as he had intended as most of his passengers did not visit his spa. He turned the transport service into his principal lucrative business venture and closed the mill and spa. Nantes citizens soon gave the nickname "omnibus" to the vehicle. Having invented the successful concept Baudry moved to Paris and launched the first omnibus service there in April 1828. A similar service was introduced in Manchester in 1824 and in London in 1829.

Regular intercity bus services by steam-powered buses were pioneered in England in the 1830s by Walter Hancock and by associates of Sir Goldsworthy Gurney, among others, running reliable services over road conditions which were too hazardous for horse-drawn transportation.

The first mechanically propelled omnibus appeared on the streets of London on 22 April 1833. Steam carriages were much less likely to overturn, they travelled faster than horse-drawn carriages, they were much cheaper to run, and caused much less damage to the road surface due to their wide tyres.

However, the heavy road tolls imposed by the turnpike trusts discouraged steam road vehicles and left the way clear for the horse bus companies, and from 1861 onwards, harsh legislation virtually eliminated mechanically propelled vehicles from the roads of Great Britain for 30 years, the Locomotive Act of that year imposing restrictive speed limits on "road locomotives" of 5 mph (8.0 km/h) in towns and cities, and 10 mph (16 km/h) in the country.

In parallel to the development of the bus was the invention of the electric trolleybus, typically fed through trolley poles by overhead wires. The Siemens brothers, William in England and Ernst Werner in Germany, collaborated on the development of the trolleybus concept. Sir William first proposed the idea in an article to the Journal of the Society of Arts in 1881 as an "...arrangement by which an ordinary omnibus...would have a suspender thrown at intervals from one side of the street to the other, and two wires hanging from these suspenders; allowing contact rollers to run on these two wires, the current could be conveyed to the tram-car, and back again to the dynamo machine at the station, without the necessity of running upon rails at all."

The first such vehicle, the Electromote, was made by his brother Dr. Ernst Werner von Siemens and presented to the public in 1882 in Halensee, Germany.[13] Although this experimental vehicle fulfilled all the technical criteria of a typical trolleybus, it was dismantled in the same year after the demonstration.

Max Schiemann opened a passenger-carrying trolleybus in 1901 near Dresden, in Germany. Although this system operated only until 1904, Schiemann had developed what is now the standard trolleybus current collection system. In the early days, a few other methods of current collection were used. Leeds and Bradford became the first cities to put trolleybuses into service in Great Britain on 20 June 1911.

In Siegerland, Germany, two passenger bus lines ran briefly, but unprofitably, in 1895 using a six-passenger motor carriage developed from the 1893 Benz Viktoria. Another commercial bus line using the same model Benz omnibuses ran for a short time in 1898 in the rural area around Llandudno, Wales.

Germany's Daimler Motors Corporation also produced one of the earliest motor-bus models in 1898, selling a double-decker bus to the Motor Traction Company which was first used on the streets of London on 23 April 1898. The vehicle had a maximum speed of 18 km/h (11.2 mph) and accommodated up to 20 passengers, in an enclosed area below and on an open-air platform above. With the success and popularity of this bus, DMG expanded production, selling more buses to companies in London and, in 1899, to Stockholm and Speyer. Daimler Motors Corporation also entered into a partnership with the British company Milnes and developed a new double-decker in 1902 that became the market standard.

The first mass-produced bus model was the B-typedouble-decker bus, designed by Frank Searle and operated by the London General Omnibus Company – it entered service in 1910, and almost 3,000 had been built by the end of the decade. Hundreds of them saw military service on the Western Front during the First World War.

The Yellow Coach Manufacturing Company, which rapidly became a major manufacturer of buses in the US, was founded in Chicago in 1923 by John D. Hertz. General Motors purchased a majority stake in 1925 and changed its name to the Yellow Truck and Coach Manufacturing Company. GM purchased the balance of the shares in 1943 to form the GM Truck and Coach Division.

Models expanded in the 20th century, leading to the widespread introduction of the contemporary recognizable form of full-sized buses from the 1950s. The AEC Routemaster, developed in the 1950s, was a pioneering design and remains an icon of London to this day. The innovative design used lightweight aluminium and techniques developed in aircraft production during World War II. As well as a novel weight-saving integral design, it also introduced for the first time on a bus independent front suspension, power steering, a fully automatic gearbox, and power-hydraulic braking.

Formats include single-decker bus, double-decker bus (both usually with a rigid chassis) and articulated bus (or 'bendy-bus') the prevalence of which varies from country to country. High-capacity bi-articulated buses are also manufactured, and passenger-carrying trailers—either towed behind a rigid bus (a bus trailer) or hauled as a trailer by a truck (a trailer bus). Smaller midibuses have a lower capacity and open-top buses are typically used for leisure purposes. In many new fleets, particularly in local transit systems, a shift to low-floor buses is occurring, primarily for easier accessibility. Coaches are designed for longer-distance travel and are typically fitted with individual high-backed reclining seats, seat belts, toilets, and audio-visual entertainment systems, and can operate at higher speeds with more capacity for luggage. Coaches may be single- or double-deckers, articulated, and often include a separate luggage compartment under the passenger floor. Guided buses are fitted with technology to allow them to run in designated guideways, allowing the controlled alignment at bus stops and less space taken up by guided lanes than conventional roads or bus lanes.

Bus manufacturing may be by a single company (an integral manufacturer), or by one manufacturer's building a bus body over a chassis produced by another manufacturer.

Transit buses used to be mainly high-floor vehicles. However, they are now increasingly of low-floor design and optionally also 'kneel' air suspension and have ramps to provide access for wheelchair users and people with baby carriages, sometimes as electrically or hydraulically extended under-floor constructs for level access. Prior to more general use of such technology, these wheelchair users could only use specialist para-transit mobility buses.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#joseeduardorodrigues #joserodrigues #eduardorodrigues #reboconortracing #reboconorttruckracingteam #sermec #motul #motorbus #man #mantrucks #fiaetrc2018 #32gpcamiondeespana #gpcamion #espana #jarama #fiaetrc #onetruckfamily #gpcamiondeespana #welovetruckracing #automotivemarketing #worldtruckracingpromotion #ceskytrucker https://www.instagram.com/p/BxnXVubCIIy/?igshid=12epqtlwnyxep

#joseeduardorodrigues#joserodrigues#eduardorodrigues#reboconortracing#reboconorttruckracingteam#sermec#motul#motorbus#man#mantrucks#fiaetrc2018#32gpcamiondeespana#gpcamion#espana#jarama#fiaetrc#onetruckfamily#gpcamiondeespana#welovetruckracing#automotivemarketing#worldtruckracingpromotion#ceskytrucker

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ray #Conklin, #president of the New #York #Motorbus #Company, (in #bow tie) and entourage drove this #custom #bus from Long #Island to the Pan-Pacific #Exposition in San #Francisco, 1915. #Year1915 #Ano1915 #Anos10 #XX #RayConklin #CustonBus #LongIsland #SanFrancisco #Exposição De #Veículos em #SãoFrancisco #EUA #USA ... https://www.instagram.com/p/Bw7gKdlFh-Q/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=14pg7viusr3kg

#conklin#president#york#motorbus#company#bow#custom#bus#island#exposition#francisco#year1915#ano1915#anos10#xx#rayconklin#custonbus#longisland#sanfrancisco#exposição#veículos#sãofrancisco#eua#usa

0 notes

Photo

Prohibition Research Committee of New York's motorbus 'Diogenes' stops in Chicago while on a national tour in search of a 'drunkard' who has been reformed by the 18th Amendment, June 11, 1932.

According to published reports, the Committee was unable to find a reformed 'drunkard.'

Chicago Tribune Historical Photo.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

captcha just asked me to identify every image with a “motorbus”

what the fuck is that? just a bus?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fic: Here We Are Together (My Fair Lady, Eliza/Henry)

I wrote three stories this year for Yuletide! I was assigned to write for alestar, and what I ended up writing (My Fair Lady) wasn't what I wanted to write. They had some excellent prompts in other fandoms, and I'm not a Henry/Eliza fan in general. Their prompt for Dr. Facilier in The Princess and the Frog was really interesting, but I couldn't get good enough reference material on Voodoo practices to feel comfortable writing it. (Everything in the library system was written by outsiders.) They also had interesting prompts for the movie Hancock, which I remember fondly but only ever saw once years ago, and I couldn't find a copy to watch, and I wasn't about to write a fic based on a decade-old memory and clips on youtube. So My Fair Lady it was, and I'm pleased with what I ended up with.

Title: Here We Are Together

Author: beatrice_otter

Fandom: My Fair Lady

Rating: G

Warnings: none

Written For: alestar in yuletide 2019

Betaed by: kalypsobean

Summary: Eliza and Freddy are working together. Henry isn't happy, and makes sure everyone knows it.

At AO3. Dreamwidth. Pillowfort.

"If we could but get the funding, Mrs. Doolittle, so much more might be accomplished," Freddy said earnestly. "Your contributions, both financial and practical, do so much good, and of course your greatest contribution is the time you and your husband give to veterans who cannot pay for your services, but unfortunately the scale of the situation—"

"Yes, yes, the number of men who returned with severe wounds is alarming, and their needs are many and great," Eliza said. "You would think that the thanks of a grateful nation would extend to paying for treatment for the injuries taken in the service of that nation."

"I sometimes think they would prefer if we had died, so that they could take out our pictures once a year on Armistice Day, and not have to deal with the inconvenient reality of our survival." It was a touch of the old, romantic, dramatic Freddy she had first met over a decade ago, although of course far bitterer than anything that young fop could have imagined.

"Perhaps I should mention the subject to my father," Eliza mused. "Much as he hates it, he needs respectable causes to mix in with his disreputable ones, if he wants to get anyone else in Parliament to actually work with him. And one can hardly get more respectable than poor veterans in need of medical care and other aid."

"It cannot hurt," Freddy said, "although far too many politicians are willing to give flowery speeches in public, and then tighten the purse strings in private. I begin to understand your preference for actions over words."

"Mm," Eliza said, making a note to write to her father. "Now, about—"

"ELIZA!"

Freddy twitched at the sound of her husband's stentorian bellow, and he turned pale so quickly she was afraid he might faint. Repeated calls did not help, but roaring back at her husband to be quiet would hardly be any better. Freddy, like so many veterans of the Great War, did not handle startlement well.

"Eliza, where are you, that great clod Bloxham was unbearable, he's the son of a grocer, he's no call to treat me like the help!" Henry strode through the door of the drawing room like a motorbus through Picadilly, coming to a crashing halt when he saw she was not alone. "Freddy," he said, wrinkling his nose. "I didn't know you were visiting."

"You are setting a poor example for the children," Eliza said firmly.

"I most certainly am not," Henry scoffed, flopping into one of the armchairs by the fireplace. He swung his legs up over the arm of the chair, twisting his body in a position that might have been leonine in a more graceful man, and he pouted. He would not call it that, but in that moment he might have been any one of their four offspring.

Eliza stared at him for a few seconds. Long experience had taught her that while immediately answering such a flat denial would only bring a round of squabbling to rival the worst the children were capable of, pinning his attention and then speaking firmly had a high rate of success. "You were shouting down the house. This is not a fishmarket, and you are not a fishmonger, though you may bellow like one. And then you were rude to a guest."

"Freddy?" Henry said incredulously. "I'm to be polite to Freddy Eynsford-Hill in my own home?" He shifted his shoulders slightly and sagged further down in the chair, a sure sign that he knew he was in the wrong but determined to be so. It was a legacy of his mother constantly demanding that he sit up straight. In Henry's mind, Eliza knew, sullen defiance and slouching were inextricable.

"Yes," Eliza said. "To his face and behind his back, both. Certainly whenever the children are present."

"Are the children present?" Henry frowned; he'd probably lost track of time and hadn't realized they were home from school. He peered around the room and found Aurelia in the windowseat with a book, Emily playing with her stuffed dog on the floor by Eliza's feet, and Edward and Andrew playing chess in the corner. All had stopped what they were doing to watch their father's dramatic entrance. "Shouldn't you be in school?" he asked.

"It's over for the day, father," Andrew pointed out.

"I should be going," Freddy said, as if he hadn't noticed the awkwardness. "We've covered the main points, and in any case Anne will fuss if I'm not home for dinner."

Normally, Eliza would say that he shouldn't let Henry drive him off, but they were mostly finished, and she could see how his hands were trembling on the head of his cane. "I shall definitely contact my father about funding, and if there's anything else I can do for your organization, please let me know."

"Your expertise is more than enough," Freddy said. "Good day, Mrs. Higgins. Professor." With gracious nods to both of them he left, leaning on his walking stick more than he usually did.

"Freddy," Henry said with distaste as soon as the front door had closed on him. "What does he want now, more charity cases to fob off on us?"

"You like working with veterans who have developed speech impediments or vocal wounds," Eliza pointed out. "It's a much more interesting challenge than teaching parvenus like Bloxham how to pretend they've always been upper-class."

"Yes, but it doesn't pay well," Henry pointed out.

"And the parvenus pay more than enough to cover the time we spend on charity cases," Eliza said. "What is it really? You've been like a bear with a sore head about Freddy for months, and frankly I'm sick of it."

"I'm volunteering my valuable time, and I don't like how he keeps asking for more."

"Not from you," Eliza pointed out. "And mostly he's asking for organizational help. I'd send him to your mother, if her health were better."

"Mother would have had him settled weeks ago," Henry grumbled.

"Possibly, but she has many more decades of experience organizing charities than I do, and a great many more contacts."

"Then Freddy should go find someone else to bother for help, someone like Mother who's spent the last fifty years organizing everyone else's lives," Henry shot back.

Eliza sat bolt upright as enlightenment dawned. "You're jealous!" she said in astonishment.

"No I'm not!" Henry said, voice climbing querulously.

"You," Eliza said, enunciating very clearly, "are jealous of Freddy Eynsford-Hill."

"Why would Papa be jealous of Mr. Eynsford-Hill?" Emily asked.

"Because Mr. Eynsford-Hill is more handsome than he is," Edward answered her.

"He is not!" Henry declaimed. "His profile is insipid."

Aurelia snickered at Henry's words.

"Aurelia, you shouldn't snicker, it's not polite," Eliza said. "And Henry, you shouldn't lie to your children. Or to yourself. Freddy is far more handsome than you are, but if that were important to me, I'd have married him instead of you."

"Was that an option, mother?" Emily asked, closing her book with a finger to hold her place.

"It certainly was," Eliza said. "He asked me before your father did. And I certainly considered it; besides his looks, he would have been far easier to live with than your father is."

"Then why did you marry me, if I am such a trial?" Henry said, with a mixture of curiosity and sarcasm.

"Because I don't have to hold back with you," Eliza said simply.

"Hah!" Henry said, sitting up straighter. "And yet you complain about my manners!"

"One can be assertive without being rude; your mother is the most forceful person I know, and her manners are impeccable," Eliza said. She turned to Emily, who at fourteen was beginning to notice men, and explained further. "You see, it is very unpleasant to live with someone who steamrolls over you, who dominates you, who controls you, even if they are not trying to hurt you. And when two people are not equals in that way—when one is always the leader and the other is always the follower, or when one is stronger and more forceful than the other—it is not healthy for either. At the time, Freddy was pleasant, but … easily led, shall we say. If he had any great depth of thought or character, he never showed them to me. I could have always had my way with very little effort, which would have been pleasant for me, but perhaps not good for me. And certainly not good for him."

"Whereas with me," Henry said, "you knew I would never let you have your way without a fight."

"With you the question was, could I get you to stop being a bully and a tyrant," Eliza said, turning back to him. "Fortunately, your bark is worse than your bite, and once you knew that I would simply leave if your conduct became intolerable, you amended your ways. I can keep you from running me over like a motor-bus, and I certainly don't have to worry about dominating you. If you'd kept treating me as you did when we first met, I'd have married Freddy and learned to be gentler."

"Mr. Eynsford-Hill doesn't seem shallow to me," Andrew said.

That was probably the source of Henry's jealousy, Eliza realized. Henry had been amused at Freddy's puppy love when they were first married. "He's changed quite considerably since he asked me to marry him," Eliza said. "He is much quieter and more thoughtful since he came home from the war."

"The Army was the making of him," Henry proclaimed, an opinion he had picked up from Colonel Pickering.

Eliza considered the way Freddy's hands sometimes shook, and how he flinched at loud noises that came unexpectedly, and the haunted look she sometimes caught in his eyes if he thought no one was looking at him. "No," she said soberly, "I think it was the breaking of him."

After dinner that evening, Eliza worked on her plans for the next day's clients, while Henry helped the children with their schoolwork, their education being far more like his had been than Eliza's.

"I still think we should send the boys to school, at least, even if we keep the girls here," Henry said as he got ready for bed that evening.

"What can they learn there that they can't learn from the perfectly good school they go to now?" Eliza asked, laying her gown neatly on the dressing room chair for Susan the maid to take care of in the morning. "Or from you?"

Henry grumbled, because he knew better than she did that the school the boys attended was as strong academically as any of the more prestigious schools they could have sent the boys to, and it was almost as distinguished. The difference was, in their current school the boys could live at home instead of boarding. "They could make good connections," he said at last, grasping at straws.

"Hah!" Eliza said as she climbed into bed. "That's rich, that is. How many connections did you make at school that were of any lasting value?"

Henry grumbled some more and climbed into bed beside her.

"Besides," Eliza said, "you'd miss them as much as I would, and you'd hate being outnumbered by women."

"True," Henry said at last. "Bloxham's going to send his boys to Eton and his girls to Cheltenham. He was bragging all about it. The blasted fool had never even heard of Tonbridge." Henry sniffed at this slight to his old school.

"You're one to talk about foolishness, wanting to send our boys away to school just because a fatuous idiot who made a fortune during the war is a snob," Eliza said. "Not to mention being jealous of Freddy, of all people."

"Oh, Eliza, must we go into that again?" Henry said, running a hand down his face. "I know I'm an old fool, you needn't rub it in."

Eliza paused and looked at him, really looked. He was so familiar to her, she knew his face better than anything in the world, and yet it suddenly struck her how old he was. When they'd married, he'd seemed ageless, powerful, in the prime of his life. And that was how she'd always thought of him; his force of personality had certainly not diminished. But he was in his seventies, now, and his face was deeply creased with age. Though his hair was receding, it was almost as dark as ever.

"I knew you were almost thirty years older than I am when I married you," she said at last. "If I'd wanted a younger man, I could have had one then. Freddy, or some other chap your mother could have found for me. I chose you, and you know how stubborn I am. You're mine, now, and I'm not about to give you up."

Henry sighed. After a few seconds he turned off the lamp on his side of the bed and slid down under the covers. Eliza followed suit, and waited to see if he'd say anything. In bed, in the dark, he was sometimes willing to be more honest than during the daylight hours.

"I feel old, Eliza," he said at last, staring up at the ceiling. "Old, and useless. I look at the men we treat, the veterans, and I'm glad Edward and Andrew are the age they are. If they'd been born a decade earlier ... All those young men chewed up at the front and spat out with their lives destroyed, and for what? So idiots like Bloxham could make their fortune in the munitions factories? So all of Europe could be laid waste? And then I read the papers and look at the fashions and the books and plays and art that are being made these days, and I don't understand it. It's all so different. All the rules of how things work that I've known all my life, they just don't seem to apply any longer." He fell silent.

Eliza waited to see if he would say any more. When it was clear he wasn't going to, she spoke. "You never liked the rules anyway."

"But I knew what they were, and how to break them," Henry said. "Now … you understand things much better than I do. You fit better than I do. You could bob your hair and go find a man who fits better than this old Victorian relic lying next to you."

"I'm not that much younger than you are, dear," Eliza pointed out dryly. "I doubt there are very many forty-year-old mothers of four with bobbed hair and short skirts in the dance halls even these days. And while I could throw you over and find a younger man, why would I want to? I've got you trained just the way I want, and I'd have to start all over again. You're mine, and you may not fit the world very well but then you never did—and you fit me quite nicely."

Henry reached over and took her hand. Eliza snuggled closer to him, and they fell asleep like that.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

@dark-eyed-elegance.

Right to the heart of Grand and Olive, they promised. In one month’s time, the People’s Motorbus Company would install their grand lines of rail and bring access to the theatre district with a speed and convenience like nothing seen before in all of Ol’ Lou, the Gateway City. All the city’s bigwigs self-congratulated themselves, rubbing elbows and mingling in the heady atmosphere of the evening’s leisures. Women charmed with their diamonds and pearls and ermine stoles: oil rich, newly-moneyed, and wealthier than generations of European nobility.

The party was noisome and stimulating, an inviting and strange melange of glamour and reckless abandon at the dawn of 1923. So did St. Louis’ finest clink their crystal flutes and cheers to the new year, popping corks of contraband champagne smuggled in by the crate from last evening’s freight.

Laurent was largely enjoying himself in this dazzling new decade, such a far cry from the shell-blasted continent he left behind, the desolation of a lost generation. Here he was slicked in his fitted grey suit and polished spats, seen as some French diplomat’s son, an impression he failed to correct.

He had hunted before the hour cleared midnight, and was flush with warmth and a bit of color to his cheeks, all the better to walk among the revelers as one of their own. The attitude was decadent and joyous, and he felt half compelled to take yet another into the upstairs suite: one of the pretty young men or one of the pretty young women, intoxicated and enticingly drowsy. His last victim had already imbibed the sibylline green fairy, and Laurent felt himself carried away, half-dazed and deliciously lazy, feeling a queer and wonderful lightness take him. He drifts through the party, light on his feet despite his curious and delightful tipsiness - still the actor’s grace, the supernatural’s perfect balance.

For some time, his pulse thundered loud in his ears, a mystifying symptom of the absinthe-laden blood from which he partook, but it reached such a clamour in his head that he could no longer ignore it, pulling away from his gay conversations, carried as though by some external, ineffable thread.

Laurent flows from the ballroom to the smoking room, awash in light from the tiffany electric lamps, a magic in this modern age.

And it is then he comes to the terrible realization that he recognizes that silhouette, that wash of auburn hair even in this bold new illumination. He would recognize it anywhere.

“Est-ce vraiment vous?“

#darkeyedelegance#verse: 20th century.#(omg this got long /// don't feel you have to match it! was just setting the scene)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Good Paws - Redwall Fanficiton

That Friday was undoubtedly one of the most exciting days in Matthew Fieldmouse’s young life. School trips were not a frequent occurrence, much less trips that brought his class to the city. They had taken the locomotive from their town to the north, riding for several hours until they had arrived at Sojourn. Matthew had ridden the train for the first time that day. He had also seen an automobile in-person for the first time, as well as the 20-story skyscrapers that sprung up from the city’s skyline.

All of the sights and sounds of Sojourn were wondrous things to behold, but Matthew was even more excited to be visiting the place at the forefront of his hopes and dreams: The Redwall Abbey Museum.

Mossflower Park was set in the center of Sojourn. Three miles on each side, the park formed a perfect square of untouched nature, save for the dirt road which allowed vehicles to access the Abbey, which sat in the dead center of the park.

From the train station, Matthew had ridden with his class of 15 on a motorbus through the park. Matthew spent his time glued to the windows, just as he had on the locomotive.

As a city, Sojourn was unique in that it was long and narrow, rather than more-or-less circular. Nobeast seemed to be particularly keen on penetrating too deep into the ancient Mossflower Wood.

Matthew had been first off the bus when it stopped at the Abbey. After rolling up his sleeves and loosening his tie to ward off the heat of the day, he eagerly drank in every detail of the ancient building. He had read all about the preservation and restoration efforts at Redwall and could name each and every feature that was either original or restored. The wooden main gates had rotted and decayed long ago. A replica pair of gates had been installed, but they were seldom closed. The only things that now separated Redwall from the outside world were a velvet rope and a sign which could be flipped to read “Open” or “Closed: No Trespassing.”

Most of the stonework was original. The walls were as solid as they had been centuries before, but many of the statues and gargoyles had become weathered with time. A few restored examples would be within the main gallery.

As Matthew continued examining every visible exterior feature with curious eyes, he heard his teacher calling out.

“Children, back in your lines please,” Mrs. Burrows called to the students who had begun wandering around. “It’s much more interesting inside than in the parking lot.”

The meandering students made their way back into the group. The class was a mix of creatures: mice, squirrels, rats, weasels, foxes, moles; most of them from farming families. The historical conflicts between the species had long ended, and the social divide between Woodlanders and the “Vermin” was no longer in place. Even the term “Vermin” had slowly been falling out of usage as a means of describing whole groups of creatures.

When the students were all together again and formed three lines of five, their hare teacher led them to the main gates where they were met by a tall, slender ferret whose nametag identified him as Jeremy.

“Students, this is Mr. Jeremy Blackfoot,” Mrs. Burrows said, introducing him. “He will be taking us on a brief tour through the Abbey. Afterward you will be free to explore on your own.”

Matthew had recognized Mr. Blackfoot before he even read his nametag. Mr. Blackfoot was widely recognized as one of the foremost historians of early and mid-Mossflower History and the most prolific author of Redwall-related material. Matthew had all of his books and copies of most of his journal articles (he was having trouble finding some of his earlier writings). He had a thousand questions he wanted to ask Mr. Blackfoot, but he knew that Mrs. Burrows wouldn’t appreciate him holding up the entire group. She, like the rest of the class, knew that Redwall was Matthew’s obsession. Though she appreciated his enthusiasm, she often tried to encourage him to explore other subjects.

The first stop on their tour was the gatehouse. Just as Matthew had read, it was kept purposefully disorganized with books stacked haphazardly on the shelves and scrolls shoved in boxes. Records from Redwall’s active days suggested that any effort at keeping everything in a proper order rapidly failed. The books and scrolls were all props, of course. All the surviving materials were kept elsewhere in display cases in the Abbey, placed in storage, or displayed at other museums.

Mr. Blackfoot next led them around the Abbey’s grounds. The orchards, berry-bushes, and gardens were still maintained by members of the museum staff. Harvested produce was offered as a snack to hungry guests or sold to interested buyers. It was said that food grown at Redwall had a special flavor that no one could replicate. Wines and ales made from the Abbey’s fruits fetched a high price at market.

The Abbey pond was also carefully maintained. In former days, large fish like greylings had lived in the pond and been eaten at feasts, but now only minnows and a few small perch darted around.

After the grounds, Mr. Blackfoot led the students up into the Abbey itself, passing through the Great Hall and up the stairs to the dormitories. One of the bedrooms was a recreation of how the room would have looked in its prime. A bed, blankets, and clothing from that period were on display. The rest of the bedrooms housed artifacts gathered from the Abbey and old dwellings in Mossflower.

The old infirmary was entirely dedicated to the old healing practices of the brothers and sisters of Redwall. Samples of medicinal herbs and berries filled shelves. Old books on the healing arts were displayed on tables. Many of the techniques the exhibits described were now long outdated, if not completed defunct.

“Class,” Mrs. Burrows called out, “we are heading back downstairs now. You will be free to explore afterwards. Remember to take notes for your reports.”

The students followed Mrs. Burrows and Mr. Blackfoot down into the Great Hall.

“Here is the pride and joy of the Redwall Abbey Museum: the famous tapestry.” Mr. Blackfoot gestured to the magnificent tapestry behind him.

The tapestry hung from the same wall where it had hung for centuries, though it was separated from the rest of the Great Hall by a barrier of glass and a chord of rope. The entire tapestry stretched from one wall to the other, and at the center was the figure of Martin the Warrior. The depiction of the warrior had a certain radiance to it. All around him, villains were shown fleeing from the warrior’s might.

“Of course,” Mr. Blackfoot continued, “what everyone really wants to see is the Sword.” He led them away from the tapestry to the center of the Hall.

The Sword rested on a cushion of velvet on an altar-like pedestal beneath a glass case.

“And no,” Mr. Blackfoot commented with a smile, “you can’t hold it. Seasons, they don’t even let me hold it.”

“That’s the end of our tour,” Mrs. Burrows informed the students. “You are free to explore the Abbey and grounds for the next two hours. Everyone thank Mr. Blackfoot for his assistance.”

“Thank you, Mr. Blackfoot,” the class chorused.

Matthew, of course, lingered near the Sword. Several other students stayed as well, examining the ancient blade, but they eventually departed to see more of the Abbey.

“You look like you could spend the next two hours looking at that,” Mr. Blackfoot said, approaching Matthew from behind.

“Mr. Blackfoot!” Matthew spluttered, startled at his sudden appearance. “Yes, I-um-yes, it is quite a beautiful artifact and a very important one too.”

Blackfoot smiled. He could see the intensity and excitement in the young mouse’s eyes. “Is there something you wanted to ask?”

Matthew practically shook with excitement. “A thousand things, if we had the time! I’ve read all of your books Mr. Blackfoot. I’ve read everything about Redwall and Mossflower that I could get my paws on. Before the Abbey, Heroes of Redwall, A History of Mossflower, all three biographies on Martin the Warriors (yours was the best of course). I suppose…I suppose I really want to know if the legends are true. All the books repeat the story of the Sword being made of a falling star. Is there anything to suggest that is true?”

Blackfoot ran his paws along the edge of the case, admiring the contents. “The metal composition of the sword has been analyzed. There is nothing non-terrestrial inside that blade. The steel is very durable and incredibly hard, more so than carbon-steel and even some conventional alloys. Whether or not the metal of the sword’s blade came from a meteorite, who can say? Martin himself stated it was so in his account of his journey to the east, and brothers and sisters of Redwall were not known to be in the habit of lying. I can’t say for certain that the metal came from the heavens, but I certainly like to think it did. At the very least, we can say that this is indeed a finely made sword.”

Matthew nodded, following every single word. “I want to believe the legend too. Do you think we’ll ever really know?”

“I’m always hopeful,” Blackfoot said. “The Salamandastron excavation project is getting underway. Maybe we’ll find some records there that confirm what the Redwall accounts tell us. I’m not working on the project myself, but I have colleagues there who will keep me informed of any developments.”

“I can’t wait to hear about what they find,” Matthew agreed. “I’d like to be one of them someday.”

“A future archeologist, eh? I saw how closely you looked at everything during the tour. I bet you’d be a terrific historian.” Blackfoot knelt down so he was at Matthew’s eye level. “How about I make you a deal? If I hear anything about exciting finds at Salamandastron, I’ll send a letter to your school.”

“I’d be honored, sir!” Matthew was practically bouncing in place. “What do I do in return?”

Blackfoot grinned, “When you’re getting ready to go to University, send me a letter. I know a few academics who could use an enthusiastic youngster.”

“Absolutely, Mr. Blackfoot! Thank you so much.”

“Anything for a fellow historian. Now let me know your name so I know who I’m writing to.”

“Right. Matthew Fieldmouse, Year 8…”

“Hold on a moment.” Blackfoot closed his eyes, trying to remember something. “You’ve written to me before, haven’t you?”

“Oh no,” Matthew covered his face. “Very long ago, sir. I was in Year 3. We had to write a letter to someone we wanted to be like. I can’t even imagine what I wrote.”

“I have had many excited young ones write me, though I believe the 10 pages you sent made yours quite memorable. Did I ever write back?”

“Oh yes, sir. I still have it with my things at home. Though at the time I received it, I’m sure I wanted to frame it.”

Blackfoot laughed as he walked away to see to another group. “You’re one-of-a-kind Matthew Fieldmouse. Keep up the good work. Remember to write me when you’re ready for University. I expect to be reading your books someday.”

Matthew’s heart was pounding like a drum. Between visiting the Abbey and meeting one of his heroes, it was almost too much. After taking a few deep breaths he decided to look at the Sword for a little longer before going back upstairs to look in the infirmary again.

As Matthew started at the Sword, someone stepped up to the other side of the case.

“It is a beautiful sword, isn’t it?”

Matthew looked up. Standing opposite him was a strangely-clad mouse. He was wearing the forest-green habit the inhabitants of Redwall had once worn as their uniform. Matthew knew that the order still existed to a small extent, but most of the active members worked at St. Ninian’s Hospital to the south as physicians and nurses. Even they wore more modern garb, save for a green sash worn around the waist as a tribute to their origins. Matthew reasoned the mouse must be one of the reenactors the museum often had around for special events.

“Yes, it is beautiful, Matthew responded. “I’ve often wondered how heavy it feels. I mean, I know it weighs 3.78 pounds, but I’ve always wanted to really feel it.”

The habit-clad mouse’s gaze met Matthew’s in the reflection of the blade. “Holding it feels surprisingly light. Baring it, however, is a far heavier burden.”

“You’ve held it! Do you work he-?” Matthew’s voice cut off. He looked around, but there was no sign of the strange mouse.

Puzzled, Matthew sought out one of the uniformed employees and asked about any reenactors on site. The worker in questions responded that there weren’t any historical reenactments scheduled for that week.

While he didn’t like leaving a puzzle unsolved, Matthew was more interested in seeing the rest of the Abbey. He set off up the stairs.

Hours later, Matthew was asleep on the locomotive heading northward towards home, lulled to sleep by the click-clack of the train on the rails. In his dreams, he was a great explorer and archeologist, finding the lost treasures of antiquity and solving the mysteries of the past.

*

Jeremy Blackfoot took his paws off the typewriter, leaned back in his chair, and yawned. Outside of his office window, he could see the sun was disappearing beneath the horizon. He had promised the Mossflower Historical Society that he’d have a rough-draft of his piece for the annual publication by the next day, and he was barely halfway done. At the start of his career, he could have turned out an equivalent piece over lunch. Between his slowness, the greying of his fur, and the aches in his joints, it seemed his body was intent on reminding him that he was not getting any younger.

The ferret-scholar prepared to get back to work when there was a knock at the door.

“Come in.” He reached for his thick-rimmed spectacles and balanced them on the bridge of his nose.

A tall, lean mouse walked through the door.

Blackfoot smiled when he saw his guest. “Matthew Fieldmouse, it’s been ages. I’ve read your letters, of course, but there’s nothing like a surprise visit.”

Matthew nodded. “How have you been, Mr. Blackfoot?”

“Old. Old is how I’ve been and how I continue to be. And must I remind you to call me Jeremy?”

Matthew grinned. “It feels so strange calling my idol by his first name.”

“Please, formality will never be necessary between us. You’re no longer a student. You’re just as good a scholar as I am, and I dare say you’ll be an even better one in not too long. Second authorship on three papers while working on your bachelor’s, that’s quite a feat. But enough small talk, what brings you to my office?”

“I’ve got something I’d like you to read,” Matthew said, pulling a bundle of paper from his satchel. “Mind you, it’s a bit longer than ten pages. It’s my doctoral thesis. I’ll be submitting it for review before the end of the semester. If you could look it over and tell me your thoughts, I’d be greatly indebted.”

Blackfoot flipped through the papers. “I’ll certainly give it a read, though you could have just mailed this to me. We’re quite a ways from the coast. How is the dig at Salamandastron nowadays? You’re far better connected there than I am.”

“It goes well. It’s one thing I wanted to talk to you about. About a month ago we tunneled into a cavern. The walls were covered in carvings covering the entire history of the mountain. We started photographing each set of carvings not long after that. (Took us ages to convince the University to buy enough film.) Take a look at these.” Matthew pulled out a series of enlarged photographic prints and placed them on the desk.

“The figures in this photograph,” Matthew pointed, “coincide with Martin’s arrival at Salamandastron. See the broken Sword around his neck? There with Dinny the Mole, the shrew Log-a-Log, and Gonff the Thief.”

“Prince of Mousethieves,” Blackfoot commented.

“Right. Prince of Mousethieves. The series in this photograph,” Matthew indicated, “takes place upon his departure; the Sword is now intact. There were a number of other carvings in the same general area, mostly pertaining to the badger lord at that time, but I thought one particular figure would interest you.”

Matthew flipped over the third photograph. The picture showed three carvings. In the first: a burning rock flew from the sky toward an anvil. In the second: a badger was beating a rock upon the anvil. In the third: a badger held a magnificent sword in his paws, presenting it to a mouse.

Blackfoot looked up from the photos. “Forged of a falling star?”

“Forged of a falling star.”

“Have the rest of the carvings been found to be accurate?”

“Those which we’ve been able to identify, yes. These are probably some of the earliest which we can corroborate. Mossflower and Redwall records start at this time as well. If the carvings continue to align with what we know, than we may very well be looking at an entirely new portion of history.”

Blackfoot took another look at the photographs. “I envy you, Matt. Finds like these can give you enough material for a lifetime of study.”

“That is my hope. Though I have been giving some thought toward taking to the seas. A few colleagues and I believe we might be able to find some of the old island settlements mentioned in Redwall’s archives. Anyway, I’m heading back to the coast tomorrow morning. Do you want to join me for breakfast?”

“I wouldn’t miss it. You remember where I live?”

Matthew nodded. “I’ll call a cab a meet you there at 7. Goodnight, Jeremy.”

“Goodnight, Dr. Fieldmouse.”

Matthew chuckled and closed the door. Blackfoot adjusted himself in his chair and prepared to resume typing. He took a look at his title, The Future of Archaeology and Historiography. He thought for a moment and adjusted the typewriter. Keys clacking, he added a subtitle:

In Good Paws.

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1915: Ray Conklin (in bow tie) and entourage drove this custom bus from Long Island to the Pan-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. (He was President of the New York Motorbus Company) [1000x748] Check this blog!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

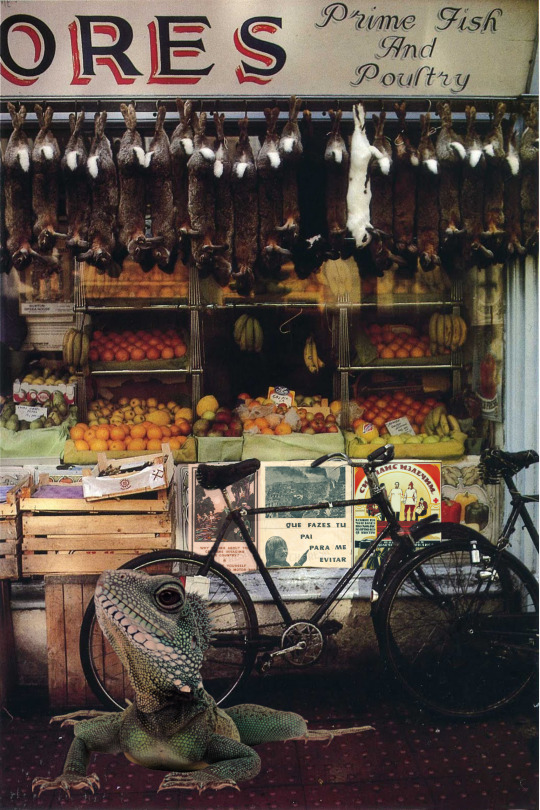

"Market Day" by Meghan Carrier. July 31, 2022. Digital collage.

Background image by Annie Griffiths for National Geographic.

Details on propaganda posters (left to right):

“Why bother about the Germans invading the country? Invade it yourself by underground and motorbus” - London Underground 1915.

"What are you doing, dad, to avoid this future for me?" - Brazil, 1960.

And I'm having a really hard time tracking down the third.

#collage#digitalcollage#collageart#collagecollective#collageoftheday#artoftheday#surrealism#photography#photoshop#adobeexpress#hyperfixation#adhdcreatives#neurodivergentcreativecommunity#collageartwork#surrealist art#mixed media#contemporary art#collageartist#propaganda posters

1 note

·

View note

Text

Despair by Vladimir Nabokov

’Tis time, my dear, ’tis time. The heart demands repose.

Day after day flits by, and with each hour there goes

A little bit of life; but meanwhile you and I

Together plan to dwell . . . yet lo! ’tis then we die.

There is no bliss on earth: there’s peace and freedom, though.

An enviable lot I long have yearned to know:

Long have I, weary slave, been contemplating flight

To a remote abode of work and pure delight. (Pushkin poem translated by VN in the foreword, p. xiv)

***

It may look as though I do not know how to start. Funny sight, the elderly gentleman who comes lumbering by, jowl flesh flopping, in a valiant dash for the last bus, which he eventually overtakes but is afraid to board in motion and so, with a sheepish smile, drops back, still going at a trot. Is it that I dare not make the leap? It roars, gathers speed, will presently vanish irrevocably around the corner, the bus, the motorbus, the mighty montibus of my tale. Rather bulky imagery, this. I am still running. (pp. 3-4)

***

Every man with a keen eye is familiar with those anonymously retold passages from his past life: false-innocent combinations of details, which smack revoltingly of plagiarism. (p. 70)

***

Hermann (playfully): “Ah, you are a philosopher, I see.”

That seemed to offend [Felix] a little. “Philosophy is the invention fo the rich,” he objected with deep conviction. “And all the rest of it has been invented too: religion, poetry . . . oh, maiden, how I suffer, oh, my poor heart! I don’t believe in love. Now, friendship—that’s another matter. Friendship and music.” (p. 75)

***

Did it actually go on like this? Am I faithfully following the lead of my memory, or has perchance my pen mixed the steps and wantonly danced away? There is something a shade too literary about that talk of ours, smacking of thumb-screw conversations in those stage taverns where Dostoevski is at home; a little more of it and we should hear that sibilant whisper of false humility, that catch in the breath, those repetitions of incantatory adverbs—and then all the rest of it would come, the mystical trimming dear to that famous writer of Russian thrillers.

It even torments me in a way; that is, it does not only torment me, but quite, quite muddles my mind and, I dare say, is fatal to me—the thought that I have somehow been too cocksure about the power of my pen—do you recognize the modulations of that phrase? You do. As for me, I seem to remember that talk of ours admirably, with all its innuendoes, and vsyu podnogotnuyu, “the whole subunguality,” the secret under the nail (to use the jargon of the torture chamber, where fingernails were prized off, and a favorite term—enhanced by italics—with our national expert in soul ague and the aberrations of human self-respect). (p. 88)

***

Old birds like Orlovius are wonderfully easy to lead by the beak, because a combination of decency and sentimentality is exactly equal to being a fool. (p. 133)

***

Dreadful thing—a hypertrophied imagination. So it is quite easy to understand that a man endowed with my acute sensitiveness gets into the devil of a state about such trifles as a reflection in a dark looking glass, or his own shadow, falling dead at his feet, und so weiter. Stop short, you people—I raise a huge white palm like a German policeman, stop! No sighs of compassion, people, none whatever. Stop, pity! I do not accept your sympathy; for among you there are sure to be a few souls who will pity me—me, a poet misunderstood, “Mist, vapor . . . in the mist a chord that quivers.” No, that’s not verse, that’s from old Dusty’s great book, Crime and Slime. Sorry: Schuld und Sühne (German edition). Any remorse on my part is absolutely out of the question: an artist feels no remorse, even when his work is not understood, not accepted. (p. 177)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

June 16, 1962 - Two U.S. Army officers were slain this morning when Communist guerrillas ambushed an armored convoy 35 miles north of Saigon. The ambush was planned and executed with a precision that was considered remarkable. All seven vehicles in the convoy were destroyed. At least 15 Vietnamese troops were killed along with several civilian occupants of a motorbus. The bus was blown up by a land mine immediately ahead of the military convoy. The two Americans, a first lieutenant and a captain, had been attached since April to the Seventh Regiment of the Fifth Division as military advisors. Capt. Walter R. McCarthy Jr. (pictured), of Columbia, S.C., formerly of Brooklyn, was one of the officers. The lieutenant’s name was withheld pending word to his next of kin. Captain McCarthy was killed immediately. His body was found in his jeep riddled with machine-gun bullets. The lieutenant, although wounded, made his way 500 yards into the woods, where it is believed pursuers overtook him. He apparently died of a bullet wound in the head.

0 notes