Text

Morocco, Redux - LuxeApocalypse, bron_yr_aur - Led Zeppelin [Archive of Our Own]

#the boys are back in town#farm frolics#jimbert fanfiction#jimmy page#robert plant#beautiful men#jimbert#new year in Morocco - chaos ensues

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

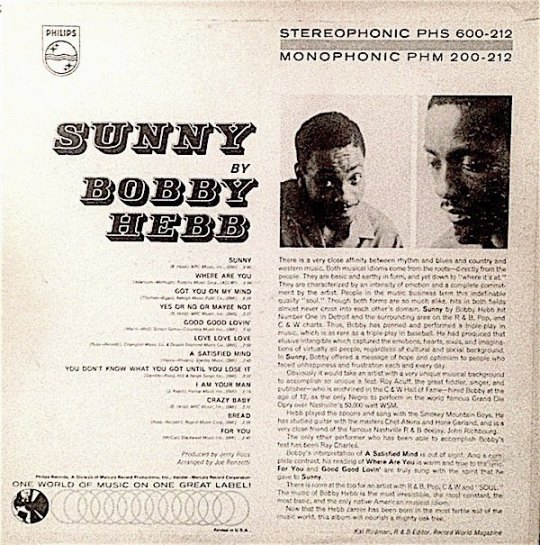

Bobby Hebb - Sunny

In the summer of 1966 the sun warmed the Earth, in part because Bobby Hebb’s compelling song, Sunny, was released that June by Phillips Records. An uplifting ode to celebration of life and perseverance; it is one the most recorded and performed popular songs. In a 2000 interview with Jonathan Marx of Nashville Scene Hebb estimated that there was some 500 recorded versions of the song. Recorded in February ’66, it entered the Billboard Top 100 at the end of June and in late August peaked at No. 2 for three weeks. It was ranked No. 27 in the Top 100 for the year. It also hit No.3 on the Billboard R&B chart and was ranked No.17 for the year. In BMI’s Top 100 Songs of the Century it is at No.25. In this particular case century represented the period of time that BMI - Broadcast Music, Inc. had existed since the 1930s. The tally also represented those songwriters and publishers that were licensed through BMI, which has had a significant share of artists in rock and roll, blues, jazz, r&b, gospel, country, folk, latin and classical styles of music as opposed to their main competitor ASCAP which has been more focused on pop artists. The ensuing Sunny album was released in September. It topped out at No.17 on the Billboard R&B during a brief period on that chart, but appears to have not broken through the Billboard Top 200 chart. Another track from the album, A Satisfied Mind b/w Love Love Love, was released later in the fall and reached No.39 on the Hot 100 and No. 40 on R&B in Billboard. A non-album song, Love Me b/w Crazy Baby (which was on the album) was released in late ’66 and only reached No.84 on the Top 100.

About the time I graduated from David Starr Jordan Junior High School, and summer days were upon me, radio jocks started spinning Sunny, a beautifully written and performed song with such wonderful positive message. I wasn’t really considering buying 45s at the time and the song lead me to buying the album when it came out in late summer making it the tenth LP of my small, but growing collection. I enjoyed some of the songs on the album and listened to it quite a bit after I first got it, less so as I started getting more records that kept me busy listening to them. It appears that the album didn’t have big sales so it must be comparatively rare these days, although I don’t get a sense that it is collectively in big demand. Since there was no internet back then, and I didn’t know about trade magazines and such, I had always wondered about what happened to Bobby. I basically heard nothing about him after 1966. It turns out that within five years he was basically out of the recording business, but still did some performing, although on a more local basis in the locations where he lived. His song still brings me sunshine when I hear it.

One of the stranger things I’ve ever come upon is that a single of Bobby Hebb’s Sunny was released by a Japanese label in 1971 backed with Summertime Blues by Blue Cheer. As soon as I saw the track times I knew it was for real. I used to put both songs on cassette tapes and have the song lengths indelibly stuck in my brain. Don’t get me wrong, I love both those songs, but I don’t think I would ever play them back to back, let alone expect them to be on the same 45 record. Just to clarify, Sunny is an R&B/Pop song as opposed to Blue Cheer’s version of Summertime Blues, which is arguably one of, if not, the earliest heavy metal songs on radio or anywhere else.

Robert “Bobby” Von Hebb was born in Nashville, Tennessee, one of eight children. His parents were both blind, and they were musicians. Bobby started performing at the age of three when he was introduced to an audience by his nine-year old brother, who was tap dancing at the time. They were both members of their gospel group Hebb’s Kitchen Cabinet Orchestra which included his siblings and parents. His brother Harold and he continued performing as a song-and-dance team, mostly in local nightclubs. Meanwhile Bobby learned to play guitar and other instruments. Being in Nashville meant that Hebb was also surrounded by “hillbilly music”, which is what later became known as country music. He was about 16 when, after playing on a local TV show hosted by record producer Owen Bradley, he was given an opportunity to perform with Roy Acuff’s Smoky Mountain Boys, playing the spoons among other instruments. He was one of the first African-Americans to play at The Grand Old Opry, performing regularly with the Acuff band, having played there before Charlie Pride.

A few years later he went to Chicago, drawn by the jazz scene, but drawn in by the blues. He ended up hanging out with Bo Diddley and is “said to have appeared on a Bo Diddley recording, Diddley Daddy…singing back-up or playing spoons, but there is no aural evidence of the latter”, according to the Richard Williams’ August 2010 Bobby Hebb obituary article in The Guardian.

By the next year he was in the U.S. Navy and assigned to the seaplane tender USS Pine Island. He learned to play trumpet while in the band, the Pine Island Pirates. After his stint in the Navy he returned to Nashville where he performed in Nashville jazz and R&B nightclubs playing guitar and trumpet. Hebb recorded his first record, Night Train to Memphis. It was a song written by Owen Bradley and performed by Acuff’s Smoky Mountain Boys. Bobby gave this country song an R&B edge, even a bit of gospel, proving that the hillbilly/country and race/rhythm & blues styles were quite compatible. The song was released on Rich Records by owner/DJ John “R” Richbourg. A few years later Bobby went to New York after he had worked in some sessions with Dr. John and James Booker, where Richbourg got him a gig at Sylvia Robinson’s (nee Vanderpool) Blue Morocco Club. As Hebb put it, “I went for two weeks and stayed for two years.” Sylvia was one half of Mickey & Sylvia and after Mickey relocated to Paris she worked with Hebb for awhile as Bobby & Sylvia.

It was while Bobby Hebb was in New York that he wrote Sunny. It was not long after the death of his brother Harold which occurred outside a Nashville nightclub the day after President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. It has been claimed by some that he wrote the song as a response to the murder of his brother, perhaps to both men, but Hebb put it another way in his interview with Jonathan Marx: “Very few people know what I really meant when I said “Sunny.” The other things, yes, but who I was talking to, or what I was talking about when I said “Sunny”—that still remains a mystery because it can be taken in quite a few ways.” After being asked if it was written for his brother he said, “Everyone seems to think that, because of the love, I suppose. But the love is always there. Sunny is your disposition. You either have a sunny disposition or you have a lousy disposition. Either you’re screaming at someone and angry, or you say, ‘No, uh-uh, I’m not angry. Let’s discuss this thing in a nice and pleasant way.’ Well, that pleasant way is a sunny disposition. Instead of confusing, and building chaos, let’s make this day a nice day for everyone. Spread that type of news so that you can become a little more relaxed and not filled with chaos, because chaos can become a killer.” In a sense, it still was in reaction to the tragic death of his brother, even if not consciously. He wrote Sunny in 1964 and, according to Richard Williams’ obituary article, it is explained, “The song came to him one morning when he had just returned to his home in Harlem from an all-night music session and a bout of heavy drinking, the sight of a purple dawn being its immediate inspiration.”

Not long after Hebb started being represented by Buster Newman, who started shopping the song around to publishers, but kept getting turned down. It did finally get picked up and was first recorded by a Japanese singer, Mieko Hirota, and as an instrumental by vibraphonist Dave Pike. Hebb was finally persuaded by eventual producer Jerry Ross to record it in New York studio Bell Sounds and it was included in an eighteen song demo. The recording of it was completed in the last moments in the session. Among those who were back up singers for the recording are names that eventually made their own marks in the music world: Melba Moore, and Nicholas Ashford and Valerie Simpson, soon to known simply as Ashford and Simpson. The album was released three months after the single and included two other Hebb-penned songs.

Sunny was Bobby’s only big hit, but it came at a very special moment. So special that he was offered the opportunity to be on the bill as The Beatles toured America. Some have said that he was the opener, but it was in fact a co-bill. At the time of the tour his song, Sunny, was ranked higher than The Beatles’ songs. Here is what he had to say about it in the interview with Jonathan Marx in 2000, “I went on the Beatles tour—but I did not open up for The Beatles. Barry and the Remains opened the show for The Beatles. Then you had The Ronettes. Then you had The Cyrcle—“Red Rubber Ball.” Then I came on, and The Beatles came on. I was the costar of that show.”

Bobby Hebb also recorded three other singles after Night Train to Memphis, one on the Rich label, and two more on a couple of other labels in the ‘60s. In addition to the three singles that charted in ’66-’67 five more unsuccessful ones were released in the U.S, through 1968, primarily on Phillips. Mercury Records released another single that didn’t chart in 1972. The album Love Games was released in 1970 on Epic Records with all songs written or co-written by Hebb. It failed to chart in any manner. In 1975 the last single Hebb released, on Laurie Records, was a disco-ized version his hit called Sunny ’76 which only reached No.94 on the Billboard R&B chart i 1976. After 35 years of non-recording Hebb issued an album on a German label in 2005.

Bobby Hebb wrote hundreds of songs, and as his recording days faded, in a large part due to alcoholism, he begun working with comedian/composer Sandy Baron on a musical that never made it to Broadway. Two of the songs, A Natural Man (originally titled Natural Resource) and His Song Shall Be Sung, made their way to Lou Rawls after they had done some re-writes to the former one. A Natural Man was a big hit for Rawls in 1971, while His Song Shall Be Sung was the B-side to Rawls’ ’71 single Believe in Me.

Bobby had gotten married and has one daughter who, as of this writing is around 35 years old. He also had a son in the mid-fifties. After a move to the Boston area, where he played in a few clubs, Hebb’s liqueur issues were coming to a head, literally. Per Charles Goldsmith’s UPI article in the South Florida Sun-Sentinel, Nov. 2, 1987, Hebb said he "was drinking a quart a day, Green Chartreuse, 110 proof.” In 1978 he was arrested for shooting his wife in the shoulder, and served two years for assault. Hebb said, “it was “an accident, my wife and I are still friends,” In the ‘80s he was working a maintenance job with the state Public Works Department and, as a recovering alcoholic, was singing in a lounge in North Boston. He had stopped drinking in 1981. Eventually returning to Nashville, Bobby Hebb died while being treated for lung cancer.

Thank you, Bobby, thank you for the gleam that shows its’ grace.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bobby_Hebb

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunny_(Bobby_Hebb_song)

https://www.nashvillescene.com/arts-culture/article/13004879/one-so-true

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/bobby-hebb-mn0000075683/biography

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/aug/05/bobby-hebb-obituary

https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-1987-11-02-8702030189-story.html

https://books.google.com/books?id=qYtz7kEHegEC&pg=PA159&lpg=PA159&dq=bobby+hebb+and+Dr.+John&source

https://www.bmi.com/news/entry/19991214_bmi_announces_top_100_songs_of_the_century

R&B top albums Bobby Hebb Sunny No. 17 https://books.google.com/books?id=hSIEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA43&dq=billboard+top+records+of+1966+december

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broadcast_Music,_Inc.

https://www.discogs.com/Bobby-Hebb-Sunny-By-Bobby-Hebb/release/14985370

https://www.discogs.com/Bobby-Hebb-Blue-Cheer-Sunny-Summertime-Blues/release/12366602

Sunny https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J-5xGXpNt74

Sunny Live with Ron Carter https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uRWyxzmNdJc

A Satisfied Mind https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shs74PDun2Q

Night Train to Memphis https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URYxTHTNKkM

A Natural Man Live with Ron Carter https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_TYrc3tjePI

Bobby Hebb Playing Sam Cooke’s You Send Me Live https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=342QerUE-og

LP10

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art review: 'Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913-1917' @ Art Institute of Chicago

If the world is coming apart at the seams and society's provisional fabric is being shredded, how does an artist respond? With anger? Analysis? Denial? Disinterest?

That's a question that thrums through a breathtaking exhibition, newly opened at the Art Institute of Chicago. And in the case of its subject, the great French painter Henri Matisse (1869-1954), the answer is not so simple.

The show is a concentrated look at a nearly five-year period between Matisse's last visit to Morocco, where the saturated light had such a deep impact on his color sense, and his departure from Paris, where he made his career, to live in the ancient Mediterranean resort at Nice. It includes some of the greatest, most enigmatic works of his long career but has never been the focus of a show.

The period also roughly coincides with World War I. When the German army advanced on Paris in 1914, having already occupied the town in northern France where the artist grew up (and members of his family still lived), and as the mountain of gruesome corpses in the most horrific conflict Europe had known since the Middle Ages piled ever higher in ensuing years, Matisse did something unexpected: He reinvented his art.

One painting places his young son Pierre by an open window, seated at a piano awaiting a lesson. Another shows the willowy figure of a dark-haired Italian woman, the wall behind her miraculously wrapping around her right shoulder like a consoling shawl. A studio interior juxtaposes a painter's palette, propped on a table, with a big cylindrical glass vase filled with water, in which a couple of goldfish swim.

Perhaps most remarkably, a huge canvas poses four monumental nudes by a river. The four stone-colored, monolithic figures might also be a single woman, seen from different sides. Statuesque, they're like prehistoric goddesses in a landscape at once lush and forbidding. And if that narrow, pointed white shape rising from the bottom edge of the 12-foot-wide canvas is indeed a serpent, are these "Bathers by a River" meant to conjure up an archaic Eve?

Matisse made several exceptional bronze sculptures too. One series began as a life-size bust of a young woman, its richly modeled surface appealing to a viewer's sense of touch through the intricate play of light and shadow. That bust becomes progressively more abstract through each of the next four iterations until, by the end, it consists of two enormous eyes split by a nose that rises into a bulbous brow. "Jeannette (V)," made in 1916, bristles with the formal power of the African tribal sculptures Matisse admired and collected.

Another series of 6-foot bronze reliefs resonates with "Bathers by a River." In each, a nude woman seen from the back, presses her body against a wall. Her head rests in the crook of her upraised left arm, and the fingers of her right hand are splayed. The pressure between body and wall seems to energize both, until finally the structure of the body, the wall and the entire relief fuse into one.

Matisse also produced prints. The most surprising are little monotypes, made by covering small copper plates with black ink, incising a linear drawing of a still life or head and pressing the plate into paper for a single quick impression. You peer into the dark surface, and the black glows with an inner light.

How do these and other of the 117 works assembled for the exhibition respond to the cruel chaos of war? The show's title says it: "Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913-1917."

Invention was not new to his art, but after 1913 he cranked up the visual volume. Matisse was 44 and already successful as war broke out, but he was turned down when he volunteered for military service. Friends did march off to fight, and some did not return. They gave their all, and he did too.

It's not a question of subject matter. In a quotation posted in the show, the artist told an interviewer in 1951: "Despite pressure from certain conventional quarters, the war did not influence the subject matter of painting, for we were no longer merely painting subjects." Instead, Matisse just never let up. The intensity of wartime Paris is matched by the fervor of his experiments.

The show begins with a necessary, even lengthy throat-clearing -- more than two dozen works that precede 1913, including 1907's still-startling "Blue Nude (Memory of Biskra)," with its transformation of a classical odalisque into something formidable and aggressive, and "Le Luxe (II)," with its sumptuous trio of female bathers abstracted from observable form. They resonate with the small Cézanne painting of bathers that Matisse owned -- the only work not made by him included in the show -- a picture of primitive paradise.

A weirdly beautiful 1913 still life, "Flowers and Ceramic Plate," is an almost entirely blue canvas with a green disk (the ceramic plate) hovering like some exotic sun above a vase of red, yellow and orange flowers below. A loose sheet of paper, perhaps a drawing or print, hangs suspended, tucked between the plate and the wall. Raking black shadows connect the disparate objects, while the colors breathe optical space into flattened shapes.

Look slowly, and the history of this painting's fabrication soon emerges -- circular echoes of larger green plates, for example, which Matisse painted over to make the shape smaller and smaller. Finally the painting assumed an existence independent of the actual still life he looked at in his studio. Color, structure and aesthetic decisions combine to assemble this amazing picture, and Matisse displays them all.

Art is not an image here, but a complex process of becoming.

He called his radical invention the development of "methods of modern construction." First inspired by color, then by the Cubism of his friend and rival Picasso, he made painting analogous to sculpture as a physical art form with distinctive material qualities. Using a variety of tools, Matisse scumbled, scored, layered, scratched and incised the paint; he scraped, scuffed and wiped the paintings' surfaces. Black and gray became voluptuous colors, rather than a void or neutral space.

Things reach a crescendo in 1916. One gallery holds the newly monumental canvases "The Piano Lesson," "Bathers by a River" and "The Moroccans" -- the last a memory of his final trip to Tangier -- plus the bronze relief "Back (III)" and that final head of Jeannette. They propose complex themes of art, sensuality and Arcadian accord.

Curators Stephanie d'Alessandro and John Elderfield note that these "radically inventive" paintings and sculptures date from the war's most menacing moment. Ferocious battles in nearby Verdun, where the German army chief Erich von Falkenhayn promised to "bleed France white," and in the region of the Somme threatened to let rivers of blood flow to Paris.

Matisse was not, as is sometimes claimed, indulging in escapist fantasy. Instead, the show's remarkable example (and first-rate catalog) suggests a profound understanding: Great artists know that the world is always already in the process of unraveling. During the epic convulsion of World War I, Matisse made sure his radical inventiveness was commensurate to the gravity of the circumstance.

~ Christopher Knight · March 22, 2010.

#matisse#painting#fauvism#art article#exibition review#review#ww1#los angeles times#Bathers by a River

0 notes

Text

How Chase Bank Chairman Helped the Deposed Shah of Iran Enter the U.S.

One late fall evening 40 years ago, a worn-out white Gulfstream II jet descended over Fort Lauderdale, Fla., carrying a regal but sickly passenger almost no one was expecting.

Crowded aboard were a Republican political operative, a retinue of Iranian military officers, four smelly and hyperactive dogs and Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the newly deposed shah of Iran.

Yet as the jet touched down, the only one waiting to receive the deposed monarch was a senior executive of Chase Manhattan Bank, which had not only lobbied the White House to admit the former shah but had arranged visas for his entourage, searched out private schools and mansions for his family and helped arrange the Gulfstream to deliver him.

“The Eagle has landed,” Joseph V. Reed Jr., the chief of staff to the bank’s chairman, David Rockefeller, declared in a celebratory meeting at the bank the next morning.

Less than two weeks later, on Nov. 4, 1979, vowing revenge for the admission of the shah to the United States, revolutionary Iranian students seized the American Embassy in Tehran and then held more than 50 Americans — and Washington — hostage for 444 days.

The shah, Washington’s closest ally in the Persian Gulf, had fled Tehran in January 1979 in the face of a burgeoning uprising against his 38 years of iron-fisted rule. Liberals, leftists and religious conservatives were rallying against him. Strikes and demonstrations had shut down Tehran, and his security forces were losing control.

The shah sought refuge in America. But President Jimmy Carter, hoping to forge ties to the new government rising out of the chaos and concerned about the security of the United States Embassy in Tehran, refused him entry for the first 10 months of his exile. Even then, the White House only begrudgingly let him in for medical treatment.

Now, a newly disclosed secret history from the offices of Mr. Rockefeller shows in vivid detail how Chase Manhattan Bank and its well-connected chairman worked behind the scenes to persuade the Carter administration to admit the shah, one of the bank’s most profitable clients.

For Mr. Carter, for the United States and for the Middle East it was an incendiary decision.

The ensuing hostage crisis enabled Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to consolidate his theocratic rule, started a four-decade conflict between Washington and Tehran that is still roiling the region and helped Ronald Reagan take the White House. To American policymakers, Iran became a parable about the political perils in the fall of a friendly strongman.

Although Mr. Carter complained publicly at the time about the pressure campaign, the full, behind-the-scenes story — laid out in the recently disclosed documents — has never been told.

Mr. Rockefeller’s team called the campaign Project Eagle, after the code name used for the shah. Exploiting clubby networks of power stretching deep into the White House, Mr. Rockefeller mobilized a phalanx of elder statesmen.

They included Henry A. Kissinger, the former secretary of state and the chairman of a Chase advisory board; John J. McCloy, the former commissioner of occupied Germany after World War II and an adviser to eight presidents as well as a future Chase chairman; a Chase executive and former C.I.A. agent, Archibald B. Roosevelt Jr., whose cousin, the C.I.A. agent Kermit Roosevelt Jr., had orchestrated a 1953 coup to keep the shah in power; and Richard M. Helms, a former director of the C.I.A. and former ambassador to Iran.

Charles Francis, a veteran of corporate public affairs who worked for Chase at the time, brought the documents to the attention of The Times.

“Today’s corporate campaigns are demolition derbies compared to this operation,” he said. “It was smooth, smooth, smooth and almost entirely invisible.”

Records of Project Eagle were donated to Yale by Mr. Reed, the campaign’s director. But he deemed the material so potentially embarrassing to his patron that Mr. Reed, who died in 2016, stipulated that the records remain sealed until Mr. Rockefeller’s death. Mr. Rockefeller died in 2017 at the age of 101.

Some of the information may embarrass others as well. Hawkish critics have often faulted Mr. Carter as worrying too much about human rights and thus failing to prop up the shah.

But the papers reveal that the president’s special envoy to Iran had actually urged the country’s generals to use as much deadly force as needed to suppress the revolt, advising them about how to carry out a military takeover to keep the shah in power.

A spokeswoman for Mr. Carter did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesman for Mr. Carter at the time of the crisis was not immediately available.

After the hostages were taken, the Carter administration worked desperately to try to free the captives, and on April 24, 1980, authorized a rescue mission that collapsed in disaster: A helicopter crash in the desert killed eight service members, whose charred bodies were gleefully exhibited by Iranian officials.

The hostage crisis doomed Mr. Carter’s presidency. And the team around Mr. Rockefeller, a lifelong Republican with a dim view of Mr. Carter’s dovish foreign policy, collaborated closely with the Reagan campaign in its efforts to pre-empt and discourage what it derisively labeled an “October surprise” — a pre-election release of the American hostages, the papers show.

The Chase team helped the Reagan campaign gather and spread rumors about possible payoffs to win the release, a propaganda effort that Carter administration officials have said impeded talks to free the captives.

“I had given my all” to thwarting any effort by the Carter officials “to pull off the long-suspected ‘October surprise,’” Mr. Reed wrote in a letter to his family after the election, apparently referring to the Chase effort to track and discourage a hostage release deal. He was later named Mr. Reagan’s ambassador to Morocco.

Mr. Rockefeller then personally lobbied the incoming administration to ensure that its Iran policies protected the bank’s financial interests.

The records indicate that Mr. Rockefeller hoped for the restoration of a version of the deposed government.

At the start of the Iranian upheaval, the papers show, Mr. Kissinger advised Mr. Rockefeller that the probable conclusion would be “a sort of Bonapartist counterrevolution that rallies the pro-Western elements together with what was left of the army.”

Mr. Kissinger, in a recent email, acknowledged that the prediction “reflects my thinking at the time” but said “it was a judgment, not a policy proposal.”

But Mr. Rockefeller evidently continued to advocate for some form of restoration long after the shah fled Tehran.

As late as December 1980, Mr. Rockefeller personally urged the incoming Reagan administration to encourage a counterrevolution by stopping “rug merchant type bargaining” for the hostages and instead taking military action to punish Iran if the hostages were not released. He suggested occupying three Iranian-controlled islands in the Persian Gulf.

“The most likely outcome of this situation is an eventual replacement of the present fanatic Shiite Muslim government, either by a military one or a combination of the military with the civilian democratic leaders,” Mr. Rockefeller argued, according to his talking points for meetings with the Reagan transition team.

An heir to his family’s oil fortune, Mr. Rockefeller styled himself a corporate statesman and personally knew many White House officials, including Mr. Carter. He had known the shah since 1962, socializing with him in New York, Tehran and St. Moritz, Switzerland.

As Tehran’s coffers swelled with oil revenues in the 1970s, Chase formed a joint venture with an Iranian state bank and earned big fees advising the national oil company.

By 1979, the bank had syndicated more than $1.7 billion in loans for Iranian public projects (the equivalent of about $5.8 billion today). The Chase balance sheet held more than $360 million in loans to Iran and more than $500 million in Iranian deposits.

Mr. Rockefeller often insisted that his concern for the shah was purely about Washington’s “prestige and credibility.” It was about “the abandonment of a friend when he needed us most,” he wrote in his memoirs.

His only advocacy for the shah, Mr. Rockefeller wrote, had been in a brief aside to Mr. Carter during an unrelated White House meeting in April 1979.

“I did nothing more, publicly or privately, to influence the administration’s thinking.”

Yet the Project Eagle papers show that Mr. Rockefeller received detailed updates on the risks to Chase’s holdings, and that even his aside to Mr. Carter in April had been planned out the previous day with Mr. Reed, Mr. McCloy and Mr. Kissinger.

Over lunch at the Knickerbocker Club in New York, Mr. Carter’s special envoy to Tehran, Gen. Robert E. Huyser, told the Project Eagle team that he had urged Iran’s top military leaders to kill as many demonstrators as necessary to keep the shah in power.

If shooting over the heads of demonstrators failed to disperse them, “move to focusing on the chests,” General Huyser said he told the Iranian generals, according to minutes of the lunch. “I got stern and noisy with the military,” he added, but in the end, the top general was “gutless.”

Mr. Rockefeller had his own special envoy to try to help the shah: Robert F. Armao, a Republican operative and public relations consultant who had worked for Mr. Rockefeller’s brother Nelson, the former governor of New York and former vice president.

Mr. Armao became one of the shah’s closest advisers, and after Nelson Rockefeller died at the start of 1979, he reported to the Project Eagle team at Chase nearly every day for more than two years.

“Everybody had the hope that there would be a repeat of the 1953 events,” Mr. Armao recalled recently, referring to the American-backed coup that restored the shah the first time he fled.

When the shah’s rule became untenable at the start of 1979, the State Department first turned to David Rockefeller for help relocating the Iranian monarch in the United States.

“Not large enough for my very special client,” Mr. Reed wrote to a Greenwich, Conn., broker who had offered two estates priced at around $2 million each — about $7.4 million today.

But while the shah tarried in Egypt and Morocco, an Iranian mob briefly seized the American Embassy in February. Diplomats warned that admitting the shah risked another assault, and Mr. Carter changed his mind about offering haven.

Mr. Rockefeller refused to deliver this bad news to the shah, afraid that it would hurt the bank by alienating a prized client.

“The risks were too high relating to the CMB position in Iran,” he responded, referring to Chase Manhattan Bank, according to the records.

Instead, Mr. Rockefeller scrambled to find accommodations elsewhere — first in the Bahamas, and then in Mexico — while strategizing with Mr. Kissinger, Mr. McCloy and others about how to persuade the White House to let in the shah.

During a three-day push in April, Mr. Kissinger made a personal appeal to the national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and a follow-up phone call to Mr. Carter. Mr. Rockefeller buttonholed the president at the White House.

And in a speech, Mr. Kissinger publicly accused the Carter administration of forcing a loyal ally to sail the world in search of refuge, “like a flying Dutchman looking for a port of call” — the seed of what became a “who lost Iran” campaign theme for the Republicans.

Mr. McCloy flooded the White House with lengthy letters to senior officials, often arguing about the danger of demoralizing other “friendly sovereigns.” “Dear Zbig,” he addressed his old friend Mr. Brzezinski.

Finally, in October, Mr. Reed sent his personal doctor to Cuernavaca, Mexico, “to take a ‘look-see’” at the shah.

He had been hiding a cancer diagnosis. The doctor, Benjamin H. Kean, determined that the shah needed sophisticated treatment within a few weeks — in Mexico, if necessary, Dr. Kean later said he had concluded.

But when Mr. Reed put the doctor in touch with State Department officials, they came away with a different prognosis: that the shah was “at the point of death” and that only a New York hospital “was capable of possibly saving his life,” as Mr. Carter described it at the time to The Times.

With that opening, the Chase team began preparing the flight to Fort Lauderdale.

“When I told the Customs man who the principal was, he almost fainted,” the waiting executive, Eugene Swanzey, reported the next morning.

The plane’s bathroom was malfunctioning. The shah and his wife hunted in vain for a missing videocassette to finish a movie. And their four dogs — a poodle, a collie, a cocker spaniel and a Great Dane — jumped on everyone. The Great Dane “hadn’t been washed in weeks,” Mr. Swanzey said. “The aroma was just terrible.”

When Mr. Reed met the plane on its final arrival in New York, he recalled the next day, the shah seemed to be thinking, “‘At last I am getting into competent hands.’”

But as he checked the shah into New York Hospital, Mr. Reed was circumspect.

“I am the unidentified American,” he told the inquisitive staff.

Mr. Reed, Mr. Rockefeller and Mr. Kissinger met again three days after the hostages were taken.

“Noted was the feeling of indignation as being high and nothing useful to say,” read the minutes.

The White House said the shah had to depart as soon as possible, but Project Eagle continued.

“The ideal place for the Eagle to land,” Mr. Reed wrote to Mr. Armao on Nov. 9, forwarding a brochure for a 350-acre Hudson Valley estate.

A week later, Mr. Rockefeller personally urged Mr. Carter in a phone call to direct the secretary of state to meet with the shah about “the current situation.” Mr. Carter did not and the shah soon departed, for Panama, then Egypt.

Only after the death of the shah, on July 27, 1980, nine months after his landing in Fort Lauderdale, did the Project Eagle team shift to new objectives. One was protecting Mr. Rockefeller from blame for the crisis.

Over roast loin of veal and vintage wine at the exclusive River Club in New York, Mr. Rockefeller and nine others on the team gathered on Aug. 19. Amid discussion of a laudatory biography of the shah by a Berkeley professor that the team had commissioned, some warned that a Rockefeller link to the embassy seizure would be hard to escape.

Why was the shah admitted? “Medical treatment/DR recommended,” one said, using Mr. Rockefeller’s initials, according to minutes of the dinner. “This association cannot be ignored.”

But Mr. Kissinger was reassuring. Congress would never hold an investigation during an election campaign.

“I don’t think we are in trouble any more, David,” Mr. Kissinger told him.

The hostages were released on Inauguration Day, Jan. 20, 1981, and a few days later Mr. Carter’s departing White House counsel called Mr. Rockefeller to inquire about how the release deal affected Chase bank.

“Worked out very well,” Mr. Rockefeller told him, according to his records. “Far better than we had feared.”

Sahred From Source link World News

from WordPress http://bit.ly/2tfntWs via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

The Tortured 136-Year History of Building Gaudí’s Sagrada Família

Exterior view of La Sagrada Familia, Barcelona. Photo by Danil Sorokin. Courtesy of Danil Sorokin.

Last month, 136 years and seven months after its first stone was laid, the Sagrada Família basilica finally got its construction permits in order. It was just the latest hurdle for Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí’s spectacular Gesamtkunstwerk to overcome, to the tune of €36 million ($40.7 million) in payments to be made to the city of Barcelona over the next decade.

By the time the city has been fully paid back, the structure of the Sagrada Família will finally be complete—assuming, of course, that construction stays on track. The structure of the eye-popping temple is currently projected to be completed by 2026, in time to mark the centennial of Gaudí’s death, with detailing and interior work expected to take another four to six years. As of 2015, when that schedule was announced, and principal construction on the remaining six towers began, chief architect Jordi Faulí i Oller said the basilica was 70 percent complete.

This year, the Sagrada Família’s dramatic Passion façade was completed (it only took 64 years), and its tallest spire, the Tower of Jesus Christ—which will make it the tallest church in the world—began to rise. In other words, Gaudí’s magnum opus is finally beginning to resemble the scale models that have long teased the 10,000-plus daily visitors to the site. As construction on the Sagrada Família enters its home stretch, it finally seems safe to look back at some of the gravest challenges this temple (technically a “minor basilica,” per a 2010 dedication by Pope Benedict XVI) has faced since that first stone was laid on March 19, 1882.

Gaudí gets called up

La Sagrada Familia under construction, 1887. Photo by PHAS/UIG via Getty Images.

Gaudí was not the Sagrada Família’s original architect. When plans for the basilica were first conceived, Gaudí was in his early twenties and just starting out as an architect, without a finished building to his name.

The campaign for the temple was started in 1874 by Josep Maria Bocabella i Verdaguer, a devout Catholic and seller of religious books, who wanted a temple devoted to the Holy Family in Barcelona. In 1877, a religious organization that Bocabella founded hired Francisco de Paula del Villar y Lozano, the official architect of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Barcelona, to start drawing up plans. Del Villar proposed a neo-Gothic building, in keeping with the dominant tastes of the time, and in 1881, Bocabella’s association secured a parcel of land that, at the time, sat just outside of the official city limits of Barcelona. The following year, on Saint Joseph’s feast day, the first stone of del Villar’s Sagrada Família was laid.

It didn’t take long for Bocabella to fire del Villar. (They disagreed on details such as the width of the columns in the temple’s crypt.) Gaudí, now 31 years old and a rising figure in Catalonia’s architectural community, could have come to his attention through any number of mutual acquaintances. But popular myth has it that in a dream, Bocabella was rescued by a knight with red hair and facial features perfectly matching Gaudí’s. However, it came to be that when he was offered the job, in November 1883, Gaudí accepted.

Gaudí gets called all the way up

Exterior view of La Sagrada Familia, Barcelona. Photo by Angela Compagnone. Courtesy of Angela Compagnone.

Photo by Bernard Hermant. Courtesy of Bernard Hermant.

By the first decade of the 20th century, Gaudí had become one of Spain’s most respected—and sought-after—architects. While the Sagrada Família slowly began to rise, he was also working on major public and private commissions. But in the late summer of 1909, at age 57, he turned his full attention to the basilica.

That summer, Barcelona descended into chaos as anarchists and striking workers clashed with military and police forces across makeshift barricades erected in the streets. Amid the violence, which came to be known as the Semana Trágica, more than 50 religious buildings were torched, and three priests were killed. The Sagrada Família, however, was spared; in the midst of the riots, a strike committee even held a meeting there, as art historian Gijs van Hensbergen recounts in his book The Sagrada Família: The Astonishing Story of Gaudí’s Unfinished Masterpiece (2017).

Over the next 15 years, Gaudí became increasingly ascetic and monk-like in his singular devotion to the Sagrada Família. In 1925, the first of its spectacular bell towers was completed—it would be the only one finished in Gaudí’s lifetime. On June 7th of the following year, on his way from the construction site to confession at a nearby church, Gaudí was struck by a tram. He died three days later, at 73 years old. On June 12, 1926, he was buried in the chapel of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in the Sagrada Família crypt.

After Gaudí’s death, Domènec Sugrañes—one of his closest assistants—took the helm. Over the next decade, Sugrañes oversaw the completion of the remaining three bell towers over the dazzling Nativity façade and its Faith portico. Ten years after the loss of the Sagrada Família’s visionary architect, the project would face a much bigger challenge.

Anarchists in the crypt

Interior view of La Sagrada Familia, Barcelona. Photo by Eleonora Abasi. Courtesy of Eleonora Abasi.

In July 1936, a nationalist military coup was launched from Spanish Morocco, setting off the Spanish Civil War. In Barcelona, anarchist labor unions quickly seized control of the city. Churches and other religious buildings were among the most popular targets in the celebratory violence that followed, and this time, the Sagrada Família did not escape unscathed.

On July 20th, members of the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) torched the temple’s provisional school, laid waste to Gaudí’s former studio—destroying countless drawings, photographs, plans, and other papers—smashed the construction site’s model and sculpture studios, and set fire to the crypt. The vandals also smashed the lid of Gaudí’s tomb. The FAI rebels returned later that day with dynamite, intending to obliterate the Nativity façade. For whatever reason, they did not go through with their plan, and the Sagrada Família was left severely damaged, but standing. In the final pages of his Homage to Catalonia (1938), novelist George Orwell—evidently not a Gaudí fan—alluded to the failed dynamiting with some regret.

“I went to have a look at the cathedral—a modern cathedral and one of the most hideous buildings in the world,” he wrote. “Unlike most of the churches in Barcelona it was not damaged during the revolution—it was spared because of its ‘artistic value,’ people said. I think the Anarchists showed bad taste in not blowing it up when they had the chance.”

While the damage to the building may not have been irreparable, the Sagrada Família’s community was terrorized and decimated. All in all, amid the anti-Catholic violence of the Spanish Civil War, 12 people involved in the operation and construction of Gaudí’s building were killed, according to van Hensbergen. And a little over two years after the outbreak of the Civil War, Sugrañes died. He was just 59, and many blamed his death on the despair brought on by the bleak outlook for the Sagrada Família.

In March 1939, less than two months after Franco’s victorious troops had marched into Barcelona, Francesc de Paula Quintana was named the Sagrada Família’s new chief architect. An assistant to both Gaudí and Sugrañes, he’d spend most of the following decade repairing the extensive damage wrought during the Civil War and plotting a course forward.

Low rumblings and high praise

Photo by Illustra Ciencia, via Flickr.

In the 1950s and ’60s, just as the global architecture community began to recognize the genius of Gaudí’s work—which had begun to fall out of favor in Catalonia in the 1920s—Spain became an increasingly popular tourist destination. In 1955, a year after the foundation work for the church’s Passion façade began, the basilica’s first public fundraising drive was terrifically successful. More than seven decades after its first stone was laid, Gaudí’s masterwork was moving forward again.

The building’s progress and increasingly global profile also made it a target for critics. On January 9, 1965, the Catalan paper La Vanguardia published a letter signed by an international coterie of artists, architects, and intellectuals—including Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto, Joan Miró, and Antoni Tàpies—calling for work on the building to be put on hold. The letter deemed continued work on Gaudí’s project a bastardization of the architect’s original vision, bemoaning the idea that one would continue an artist’s unfinished work after his death. Nevertheless, work continued, and towers and visitor numbers continued to rise.

Over the ensuing decades, steadily rising visitor numbers provided plentiful funding for construction. In 2005, the Sagrada Família was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, but a couple of years later, a new project threatened to bring everything crashing down.

In 2007, the Spanish government announced plans to bore a 39-foot-wide high-speed train tunnel under Barcelona, passing near the foundations of the Sagrada Família. Jordi Bonet i Armengol, the director of construction on the temple at the time, warned that creating the tunnel “could prove fatal” to Gaudí’s building, causing “irreversible damage,” and that vibrations caused by the regular passage of high-speed trains beneath the building could cause fissures and loosen tiles from its walls.

In response, special provisions were made to reduce the tunnel’s possible impact on the Sagrada Família. Construction on the tunnel began in 2010, and trains began rolling through it three years later—to date, no damage has been reported.

A few weeks after the tunnel-boring machine passed under the Sagrada Família’s foundations, Pope Benedict XVI consecrated the temple. On November 7, 2010, the pope told those assembled for the service: “I have been moved above all by Gaudí’s confidence when, in the face of many difficulties, filled with trust in providence, he would exclaim, ‘Saint Joseph will finish this church.’”

While, at times, it has seemed that it would take a miracle to finish the Sagrada Família, it may indeed come down to the willpower of one very determined saint. And, as luck would have it, Gaudí’s candidacy for sainthood is gathering momentum.

from Artsy News

0 notes

Text

The Islamic World Doesn't Need a Reformation

New Post has been published on https://usnewsaggregator.com/the-islamic-world-doesnt-need-a-reformation/

The Islamic World Doesn't Need a Reformation

Various Western intellectuals, ranging from Thomas Friedman to Ayaan Hirsi Ali, have argued over the past decades that Muslims need their own Martin Luther to save themselves from intolerance and dogmatism. The Protestant Reformation that Luther triggered exactly 500 years ago, these intellectuals suggest, can serve as a model for a potential Muslim Reformation. But is there such a connection between the Reformation in Christendom and the “reform” that is arguably needed in Islam?

To start with, it’s worth recalling that Islam, in the form of the Ottoman Empire, helped Protestantism succeed and survive. In the 16th century, much of Europe was dominated by the Holy Roman Empire, which had ample means to crush the Protestant heretics. But the same Catholic empire was also constantly threatened and kept busy by “the Turks” whose own empire-building inadvertently helped the Protestants. “The Turk was the lightning rod that drew off the tempest,” noted J. A. Wylie in his classic, History of Protestantism. “Thus did Christ cover His little flock with the shield of the Moslem.”

Related Stories

More importantly, some early Protestants, desperately seeking religious freedom for themselves, found inspiration for that in the Ottoman Empire, which was then more tolerant to religious plurality than were most Catholic kingdoms. Jean Bodin, himself a Catholic but a critical one, openly admired this fact. “The great empereour of the Turks,” the political philosopher wrote in the 1580s, “detesteth not the straunge religion of others; but to the contrarie permitteth every man to live according to his conscience.” That is why Luther himself had written about Protestants who “want the Turk to come and rule because they think our German people are wild and uncivilized.”

Surely those days are long gone. The great upheavals that began in the West with the Protestant Reformation ultimately led to the Enlightenment, liberalism, and the modern-day liberal democracy—along with the darker fruits of modernity such as fascism and communism. Meanwhile, the pre-modern tolerance of the Muslim world did not evolve into a system of equal rights and liberties. Quite the contrary, it got diminished by currents of militant nationalism and religious fundamentalism that began to see non-Muslims as enemies within. That is why it is the freedom-seeking Muslims today who look at the other civilization, the West, admiring that it does “permitteth every man to live according to his conscience.”

And that is also why there are people today, especially in the West, who think that “a Muslim Martin Luther” is desperately needed. Yet as good-willed as they may be, they are wrong. Because while Luther’s main legacy was the breakup of the Catholic Church’s monopoly over Western Christianity, Islam has no such monopoly that needs to be challenged. There is simply is no “Muslim Pope,” or a central organization like the Catholic hierarchy, whose suffocating authority needs to be broken. Quite the contrary, the Muslim world—at least the Sunni Muslim world, which constitutes its overwhelming majority—has no central authority at all, especially since the abolition of the Caliphate in 1924 by Republican Turkey. The ensuing chaos in itself seems be a part of “the problem.”

In fact, if the Muslim world of today resembles any period in Christian history, it is not the pre-Reformation but rather the post-Reformation era. The latter was a time when not just Catholics and Protestants but also different varieties of the latter were at each other’s throats, self-righteously claiming to be the true believers while condemning others as heretics. It was a time of religious wars and the suppression of theological minorities. It would be a big exaggeration to say that the whole Muslim world is now going through such bloody sectarian strife, but some parts of it—such as Iraq, Syria, and Yemen—undoubtedly are.

Besides, various “reform” movements have already emerged in the Muslim world in the past two centuries. Just like Luther’s Reformation, these movements claimed to go back to the scriptural roots of the religion to question the existing tradition. While some of the reformists took this step with the intention of rationalization and liberalization, giving us the promising current called “Islamic modernism,” others did it with the exact opposite goal of dogmatism and puritanism. The latter trend gave us Salafism, including its Saudi version Wahhabism, which is more rigid and intolerant than the traditional mainstream. And while most Salafis have been non-violent, violent ones formed the toxic blend called “Salafi Jihadism,” which gave us the savagery of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State.

Because there is no central religious authority, consider the only definitive authority available, which is the state.

That is why those who hope to see a more tolerant, free, and open Muslim world should seek the equivalent not of the Protestant Reformation but of the next great paradigm in Western history: the Enlightenment. The contemporary Muslim world needs not a Martin Luther but a John Locke, whose arguments for freedom of conscience and religious toleration planted the seeds of liberalism. In particular, the more religion-friendly British Enlightenment, rather than the French one, can serve as a constructive model. (And, as I argued elsewhere, special attention should also be given to the Jewish Enlightenment, also called Haskalah, and its pioneers such as Moses Mendelssohn. Islam, as a legalist religion, has more commonalities with Judaism than with Christianity.)

Luckily, efforts toward a Muslim Enlightenment have been present since the 19th century, in the form of the above-mentioned “Islamic modernism.” British historian Christopher de Bellaigue deftly demonstrated the achievements of this trend in his recent book, The Islamic Enlightenment. He also rightly noted that this promising era—also called “the liberal age” of Arabic thought by the late historian Albert Hourani—experienced a major step back in the 20th century with Western colonialism and the reactions it provoked. Then came a wave of “counter-Enlightenment,” which is the fundamentalist revival that created Islamism and jihadism.

As a result, the Muslim world of today is a very complex place, where secularists, liberal reformists, illiberal conservatives, passionate fundamentalists, and violent jihadists all enjoy varying degrees of influence from region to region, nation to nation. The pressing question is how to move this world in a positive direction.

Because there is no central religious authority to lead the way, one should consider the only definitive authority available, which is the state. Whether we like it or not, the state has been quite influential on religion throughout the history of Islam. It has become even more so in the past century, when Muslims overwhelmingly adopted the modern nation-state and its powerful tools, such as public education.

It really matters, therefore, whether the state promotes a tolerant or a bigoted interpretation of Islam. It really matters, for example, when the Saudi monarchy, which for decades has promoted Wahhabism, vows to promote “moderate Islam,” as Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman recently did, giving some hope for the future. It is especially significant that this call for moderation implies not just fighting terrorism, but also liberalizing society by curbing the “religion police,” empowering women, and being “open to the world and all religions.”

This argument may sound counterintuitive to some Western liberals, who are prone to think that the best thing for a state is to just stay out of religion. But in a reality where the state is already deeply involved in religion, its steps toward moderation and liberalization should be welcome. It’s also worth remembering that the success of the Enlightenment in Europe was partly thanks to the era of “Enlightened despots,” the monarchs who preserved their power even as they realized crucial legal, social, and educational reforms.

When we look at the Middle East we see that countries with enlightened monarchies, such as Morocco or Jordan, promote and exemplify religious moderation, unlike the many “revolutionary” republics that end up as authoritarian one-party states or tyrannies of the illiberal majority. (Only Tunisia stands out as an exceptionally bright spot.) And in Malaysia, where I recently had the unexpected chance to become acquainted with the “religion enforcement police,” it is the sultans that try to keep such zealots, and their popular support, in check.

A full-fledged Islamic Enlightenment would require other features, such as the rise of the Muslim middle class (which would itself require market-based economies rather than rentier states) and an atmosphere of free speech in which novel ideas can be discussed without persecution. Yet even those very much depend on political decisions that states will make or not make.

If the Protestant Reformation teaches us anything, it is that the road from religious fracturing to religious tolerance is long and winding. The Muslim world is somewhere on that road at the moment, and more twists and turns probably await us in the decades to come. In the meantime, it would be a mistake to look at the darkest forces within the current crisis of Islam and to arrive at pessimistic conclusions about its supposedly immutable essence.

Original Article:

Click here

0 notes

Text

ISIS claims responsibility for Turkey terror attack

ISTANBUL (AP) -- The Islamic State group on Monday claimed responsibility for the New Year's attack at a popular Istanbul nightclub that killed 39 people and wounded scores of others. The IS-linked Aamaq News Agency said the attack was carried by a "heroic soldier of the caliphate who attacked the most famous nightclub where Christians were celebrating their pagan feast." It said the man opened fire from an automatic rifle and also detonated hand grenades in "revenge for God's religion and in response to the orders" of IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. The group described Turkey as "the servant of the cross" and also suggested it was in retaliation for Turkish military offensives against the Islamic State group in Syria and Iraq. "We let infidel Turkey know that the blood of Muslims that is being shed by its airstrikes and artillery shelling will turn into fire on its territories," the statement said. Earlier, Turkish media reports had said that Turkish authorities believed the IS group was behind the attack and that the gunman, who is still at large, comes from a Central Asian nation and is likely to be either from Uzbekistan or Kyrgyzstan. According to Hurriyet and Karar newspapers, police had also established similarities with the high-casualty suicide bomb and gun attack at Istanbul's Ataturk Airport in June and was investigating whether the same IS cell could have carried out both attacks. The gunman killed a policeman and another man outside the Reina club in the early hours of 2017 before entering and firing at an estimated 600 people partying inside with an automatic rifle. Nearly two-thirds of the dead in the upscale club, which is frequented by local celebrities, were foreigners, Turkey's Anadolu Agency said. Many of them hailed from the Middle East. Citing Justice Ministry officials, Anadolu reported that 38 of the 39 dead have been identified and 11 of them were Turkish nationals, and one was a Turkish-Belgian dual citizen. The report says seven victims were from Saudi Arabia; three each were from Lebanon and Iraq; two each were from Tunisia, India, Morocco and Jordan. Kuwait, Canada, Israel, Syria and Russia each lost one citizen. Relatives of the victims and embassy personal were seen walking into an Istanbul morgue to claim the bodies of the deceased. Turkish officials haven't released the names of those identified. The mass shooting followed more than 30 violent acts over the past year in Turkey, which is a member of the NATO alliance and a partner in the U.S.-led coalition fighting against the Islamic State group in Syria and Iraq. The country endured multiple bombings in 2016, including three in Istanbul alone that authorities blamed on IS, a failed coup attempt in July and renewed conflict with Kurdish rebels in the southeast. The Islamic State group claims to have cells in the country. Analysts think it was behind suicide bombings last January and March that targeted tourists on Istanbul's iconic Istiklal Street as well as the attack at Ataturk Airport in June, which killed 45 people. In August, Turkey sent troops and tanks into northern Syria, to clear a border area from the IS and also curb the territorial advances of Syrian Kurdish forces in the region. The incursion followed an IS suicide attack on an outdoor wedding party in the city of Gaziantep, near the border with Syria, that killed more than 50 people. In December, IS released a video purportedly showing the killing of two Turkish soldiers and urged its supporters to "conquer" Istanbul. Turkey's jets regularly bomb the group in the northern Syrian town of Al-Bab. Turkish authorities haven't confirmed the authenticity of the video. Last week, Turkey and Russia brokered a cease-fire for Syria that excludes the IS and other groups considered to be terrorist organizations. On Monday, Anadolu said more than 100 Islamic State targets in Syria have been hit by Turkey and Russia in separate operations. Citing the Turkish Chief of General Staff's office, Anadolu said Turkish jets struck eight IS group targets while tanks and artillery fired upon 103 targets near Al Bab, killing 22 extremists while destroying many structures. The Russian jets also attacked IS targets in Dayr Kak, eight kilometers (five miles) to the southwest of Al Bab. Prime Minister Binali Yildirim said the attacker left a gun at the club and escaped by "taking advantage of the chaos" that ensued. Some customers reportedly jumped into the waters of the Bosporus to escape the attack. ___ Bassem Mroue reported from Beirut. Suzan Fraser in Ankara, and Cinar Kiper in Istanbul, contributed to this report. Copyright 2017 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed. http://dlvr.it/N1KbMY

0 notes