#new york manumission society

Note

I think the reason why Hamilton never addressed slavery or abolition after John's death was because it all reminded him too much of his partnership with John and would have been really painful to go back to. but I think if John was still around he definitely would have worked more on ending slavery then what he did

That is actually quite far far from the truth.

Hamilton didn't just completely dismiss slavery or abolition after Laurens's death. After the Revolution, Hamilton became a founding member of the New York Manumission Society. Hamilton, Robert Troup, and William Matlack, proposed imposing strict timetables on when a member of the Society would be required to free any slaves they owned. Hamilton was a loyal and hardworking member of the New York Manumission Society. He remained a member until his death in 1804, and he also served as legal counsel for them when he was in desperate need of money and had turned down jobs with payment. Additionally, Hamilton prioritized his work at the Society enough so that he would stay nights working there instead of returning to his family at the Grange. [x] Also when the Manumission Society was established in 1785, the society sought both to agitate the New York legislature for a gradual abolition law and to protect freedmen from the scourge of kidnappings plaguing the city. [x] All of which Hamilton helped contribute to. [x]

And I don't even think Laurens has any relation as to why Hamilton didn't make as much of a commitment in antislavery proposals and opportunities. When Hamilton was Treasury Secretary, he undermined the plantation system of the South that perpetuated the institution of slavery in favor of industrialization, which he had initially hoped would eventually get resolved into a thriving economy—And in extension, would no longer rely on slaves labor. Hamilton's lack of assistance in abolitionism was arguably due to his belief - that eventually proved wrong - that such activism wouldn't be necessary (Although that also could have just been his excuse when associating with other planation or slave owners like Washington or the Schuylers'). The Massachusetts's courts had abolished slavery entirely, while Pennsylvania and New York were already instituting gradual abolition laws. Also influential men like Washington were setting examples of manumitting slaves upon their death (That didn't work out so well). The Industrial Revolution took hold, even inventions like Whitney's Cotton Engine were coming to light, and the need for financial investments like plantations were seemingly becoming unnecessary. Unlike England, the US didn't have such a large population of the landless lower class to supply labor for industry. So, for a period of time, the inevitable demise of industrial slavery seemed concrete. Hamilton didn't even mention slavery once in his report of exploration in labor forces on Manufactures. [x] Because if slavery was indeed going to slide down the landside of declining need over the same time as manufacturing and industry increased in need, then it wasn't even worth a thought in his solution to the foreseeable labor shortages.

It is true that Hamilton didn't prioritize putting an end to slavery as much as he passionately felt about other issues at the time, but I think it's just ridiculous to tack on grievance as an excuse to not speak out or do anything against human suffrage and bondage. This is Hamilton, who wrote several pamphlets during his life time, and was notorious for doing so with such a passionate drive and talented skill—he should have written about it far more, but he also didn't throw it all out the window due to Laurens's death. I mean, I'm sure Laurens would have given him that push to do more, but I don't think it's relevant to why Hamilton didn't do more.

#amrev#american history#alexander hamilton#historical alexander hamilton#historical john laurens#john laurens#slavery#new york manumission society#history#queries#sincerely anonymous#cicero's history lessons

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ira Frederick Aldridge (July 24, 1807 – August 7, 1867) was a stage actor and playwright who made his career after 1824 largely on the London stage and in Europe, in Shakespearean roles. Born in New York City, he is the only actor of African American descent among the 33 actors on the English stage honored with bronze plaques at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon. He was popular in Prussia and Russia, where he received top honors from heads of state. At the time of his sudden death, while on tour in Poland, he was arranging a triumphant return to America, with a planned 100-show tour to the US.

At the age of 13, he went to the African Free School in New York City, established by the New York Manumission Society for the children of free African Americans and slaves. They were given a classical education, with the study of English grammar, writing, mathematics, geography, and astronomy. His classmates at the African free school included Charles L. Reason, George T. Downing, and Henry Highland Garnet. His early exposure to theater included viewing plays from the high balcony of the Park Theatre, New York’s leading theater of the time, and seeing productions of Shakespeare’s plays at the African Grove Theatre.

He married Margaret Gill, an Englishwoman (1824-64). He married his mistress Sweedish countress Amanda von Brandt (1865-67). They had four children. He had a son. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would Laurens have joined Hamilton in the Manumission Society if he lived?

Nope - at least not the same one.

Hamilton was a member of the New-York Manumission Society (NYMS), and if Laurens had lived, he would most likely have settled in South Carolina - so even if he was eligible for membership, it would have been in name only. Instead, Laurens would likely have founded one of his own (to my knowledge, South Carolina never had one), or more likely, taken a political office to actively work against the institution of slavery.

It's worth noting that Hamilton's interest in manumission and the abolishment of slavery was predominantly fanned by Laurens, and he did not seem to have a particular drive to continue that mission after Laurens' death.

There's a superb article by Arthur Scherr called Alexander Hamilton and slavery: a closer look at the Founder that spells this out (DM me if you can't get access and I'll send you the PDF). Essentially, his argument is that Hamilton's antislavery credentials have been vastly overstated recently, focusing on two main pieces of evidence:

The letter Hamilton writes to John Jay, in support of Laurens' plan to enlist enslaved men into a batallion and then emancipate them after the war. In it, you can see Laurens' philosophical influence, and even so, Hamilton puts the proposal into practical, expedient terms rather than more ideological ones.

Hamilton's membership to the NYMS - even though his participation was fairly minimal, and he often worked at odds with the society's mission.

If Laurens had lived, he would likely have continued to push Hamilton into supporting his antislavery activities - whether he would have been successful is another question.

#historical john laurens#john laurens#historical alexander hamilton#alexander hamilton#amrev#slavery

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is the worst founding father?

Round 2: Button Gwinnett vs Robert Troup

Button Gwinnett (March 3, 1735 – May 19, 1777) was a British-born American Founding Father who, as a representative of Georgia to the Continental Congress, was one of the signers (first signature on the left) of the United States Declaration of Independence. Gwinnett was killed in a duel by rival Lachlan McIntosh following a dispute after a failed invasion of East Florida.

Gwinnett's business activities took him from Newfoundland to Jamaica. Never very successful, he moved to Savannah, Georgia in 1765, and opened a store. When that venture failed, he bought (on credit) St. Catherine's Island, as well as a large number of enslaved people, in order to attempt to become a planter. Though his planting activities were also unsuccessful, he did make a name for himself in local politics and was elected to the Provincial Assembly.

During his service in the Continental Congress, Gwinnett was a candidate for a brigadier general position to lead the 1st Regiment in the Continental Army but lost out to McIntosh. The loss of the position to his rival embittered Gwinnett greatly.

He became Speaker of the Georgia Assembly, a position he held until the death of the President (Governor) of Georgia Archibald Bulloch. Gwinnett was elevated to the vacated position by the Assembly's Executive Council. In this position, he sought to undermine the leadership of McIntosh. Tensions between Gwinnett and McIntosh reached a boiling point when the General Assembly voted to approve Gwinnett's attack on British Florida in April 1777.

Gwinnett had McIntosh's brother arrested and charged with treason. He also ordered McIntosh to lead an invasion of British-controlled East Florida, which failed. Gwinnett and McIntosh blamed each other for the defeat, and McIntosh publicly called Gwinnett "a scoundrel and lying rascal". Gwinnett then challenged McIntosh to a duel, which they fought on May 16, 1777. The two men exchanged pistol shots at twelve paces, and both were wounded. Gwinnett died of his wounds on May 19, 1777. McIntosh, although wounded, recovered and went on to live until 1806.

Robert Troup (1757 – January 14, 1832) was a soldier in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of New York. He participated in the Battles of Saratoga and was present at the surrender of British General John Burgoyne.

Troup was secretary of the Board of War starting in February 1778, and secretary of the Board of Treasury from May 29, 1779 to February 8, 1780.

Troup was a lifelong personal friend of Alexander Hamilton, with whom he had roomed at King's College and served in the Hearts of Oak militia unit, and he continued to support Hamilton in politics.

Troup was a co-founder in 1785 of the New York Manumission Society, which promoted the gradual abolition of slavery in New York, and protection of the rights of free black people. Despite being a slaveholder himself, Troup presided at the first meeting of the Society. Together with Hamilton, who joined the Society at its second meeting, Troup led an unsuccessful effort to adopt a rule requiring members of the Society to free any slaves that they themselves owned. In the absence of such a resolution, Troup himself waited to manumit his slaves, freeing four between 1802 and 1814.

#founding father bracket#worst founding father#founding fathers#amrev#brackets#polls#button gwinnett#robert troup

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 Accomplishments of Alexander Hamilton:

1. **Founding Father:** Alexander Hamilton was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, playing a key role in the drafting of the U.S. Constitution.

2. **The Federalist Papers:** Hamilton co-authored a significant portion of "The Federalist Papers," a series of essays advocating for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

3. **First Secretary of the Treasury:** As the first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton established the foundation of the U.S. financial system, including the creation of the First Bank of the United States.

4. **Establishment of the U.S. Mint:** Hamilton played a crucial role in establishing the U.S. Mint, contributing to the development of the country's currency and financial infrastructure.

5. **Assumption of State Debts:** Hamilton's financial plan included the assumption of state debts by the federal government, helping to stabilize the nation's finances and gain support for his economic policies.

6. **Report on Manufactures:** Hamilton's "Report on Manufactures" advocated for protective tariffs and industrial development, laying the groundwork for future economic policies.

7. **Co-Founder of the New York Post:** Hamilton co-founded the New York Post, one of the oldest continually published newspapers in the United States.

8. **Military Service:** During the American Revolution, Hamilton served as a senior aide to General George Washington, demonstrating leadership and strategic acumen.

9. **Establishment of the Coast Guard:** Hamilton played a role in the creation of the Revenue Cutter Service, the precursor to the United States Coast Guard, to enforce customs and protect maritime interests.

10. **Contributions to the Judiciary:** While not a Supreme Court Justice, Hamilton's ideas and influence on the judiciary system are evident in his role in shaping the structure and independence of the federal judiciary through the Judiciary Act of 1789.

11. **Creation of the National Gazette:** Hamilton was involved in the establishment of the National Gazette, a newspaper that supported the Federalist cause and provided a platform for political discourse.

12. **Orchestrating Compromises:** Hamilton played a key role in brokering important compromises during the Constitutional Convention, contributing to the successful framing of the U.S. Constitution.

13. **Formation of the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures:** Hamilton founded the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures, promoting industrial and economic development in the United States.

14. **Establishment of the U.S. Army:** As the nation's first Secretary of War, Hamilton contributed to the development and organization of the U.S. Army.

15. **Jay Treaty Negotiations:** Hamilton was involved in negotiating the Jay Treaty with Great Britain, helping to ease tensions and improve trade relations between the two nations.

16. **Creation of the New York Manumission Society:** Hamilton was a co-founder of the New York Manumission Society, advocating for the abolition of slavery and promoting the rights of free black individuals.

17. **Role in the Constitutional Convention:** Hamilton's active participation in the Constitutional Convention included delivering a six-hour speech outlining his vision for a strong central government.

18. **Authorship of Military Strategies:** During the Revolutionary War, Hamilton demonstrated his military acumen through his strategic writings and plans, influencing military tactics.

19. **The American System:** Hamilton's economic vision, known as the American System, emphasized protective tariffs, a national bank, and internal improvements to foster economic development.

20. **Contributions to the Whiskey Rebellion:** As a response to the Whiskey Rebellion, Hamilton played a role in formulating a peaceful resolution, showcasing the federal government's ability to maintain law and order.

10 Controversies of Alexander Hamilton:

1. **Reynolds Pamphlet Scandal (1797):** Hamilton's extramarital affair with Maria Reynolds became public when he published a pamphlet admitting to the affair to clear his name from charges of financial misconduct. This damaged his reputation and political standing.

2. **Opposition to John Adams (1800):** Hamilton's criticisms of fellow Federalist John Adams during the presidential election of 1800 contributed to Adams' defeat and strained relations within the Federalist Party.

3. **Disagreements with Thomas Jefferson:** Hamilton had ongoing ideological clashes with Thomas Jefferson, primarily over issues such as the power of the federal government, interpretation of the Constitution, and the role of banks.

4. **Bank of the United States Controversy:** Hamilton's push for the creation of the First Bank of the United States faced opposition from those who believed it exceeded federal authority, leading to heated debates over the interpretation of the Constitution.

5. **Alien and Sedition Acts (1798):** Hamilton's Federalist Party supported the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts, which aimed to suppress political dissent and limit the influence of immigrants, sparking opposition and debates over civil liberties.

6. **Accusations of Monarchism:** Hamilton was accused by political rivals of harboring monarchist tendencies due to his support for a strong central government and his advocacy for lifetime appointments of senators and the president.

7. **Role in the Whiskey Rebellion:** Hamilton's role in suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion raised concerns about the federal government's use of military force to quell domestic unrest, leading to accusations of authoritarianism.

8. **Tensions with Aaron Burr:** Hamilton's long-standing personal and political conflicts with Aaron Burr culminated in a fatal duel in 1804, resulting in Hamilton's death and damaging Burr's political career.

9. **Criticism of Adams' Military Leadership:** During the Quasi-War with France, Hamilton publicly criticized President John Adams' military leadership, causing further divisions within the Federalist Party.

10. **Economic Policies and Class Divide:** Hamilton's economic policies, while stabilizing the nation's finances, faced opposition from those who believed they favored the wealthy, contributing to early class divisions and political polarization.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Can you go into more detail on Hamilton's life-long passion against slavery? From what I've read, he really didn't speak out that much against slavery, especially not for a man who wrote excessively about everything he was passionate about. I know he was part of the manumission society but didn't seem to put much effort into it. His interest as an abolitionist seemed to stem mostly from Laurens' influence and deteriorated after Laurens' death. Thanks!

I think life-long passion is probably putting it too strongly, but he also didn’t completely let the issue drop after Laurens’ death, either. As for his participation in the Manumission Society, he did remain a member from the Society’s inception until his death in 1804, continuing to serve as legal counsel for them even at times when he was so pressed for time and money he refused other pro bono work. He even ranked his obligation to the Society high enough to keep him away from his family; in a letter he wrote to Eliza on September 23, 1801, he wrote that a meeting of the Society was keeping him from going back to the Grange for another night:

“I am vexed and chagrined, My beloved Eliza, that I cannot come out2 to day as I intended. I had requested a Meeting of the Manumission Society for this forenoon; but for some reason unknown to me, it is called for this Evening seven oClock. I cannot of course help attending and I have little hope that it will break up in time to make the journey this Evening.”

I also think that Hamilton believed his work at the Treasury to help usher in what we now term the Industrial Revolution would help bring about an end to slavery in America. Northern states were already abolishing slavery through the courts or by statute, some immediately and some gradually. George Washington and other prominent figures were setting an example of manumitting their slaves upon their death. As industrialization swept in, an mechanization eased the need for manual labor upon farmers, I think Hamilton expected slavery as an institution was in its death throes. Unfortunately, that didn’t turn out to be at all true. (I went into more of this argument in my post a while back, which you can read here.)

So, while I agree with you that had Hamilton felt as passionately about ending slavery as he did about other issues he championed, he would have written about it far more, he also didn’t completely abandon the cause after Laurens’ death. He volunteered his time on an off for almost two decades with an organization that gave legal assistance to free Black men and women in danger of being kidnapped into slavery and helped agitate for a gradual abolition law in New York. His work as Treasury Secretary was set to undermine the plantation system of South that perpetuated the institution of slavery in favor of industrialization, which he hoped would create a thriving, diverse economy no longer reliant on slave labor. He may not have been passionately committed to ending slavery in such a way that he deserves the badge of abolitionist today, but he was also far from indifferent.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Debunking and, in my Humble Opinion, Superior Version of Weird History’s “Hardcore Facts About Alexander Hamilton”

I haven’t updated my blog in quite some time, and that is due to my schedule being primarily dominated by school. So, I decided my first step into posting semi-regularly once more shall be a more casual, more fun endeavor.

If you have not heard of the Weird History youtube channel, good for you. It is yet another social media platform that misconstrues history to appeal to the public’s enjoyment of extremes and strangeness. I saw The Historical Fashion Queens make a video responding to their highly misinformed documentary on corsetry on Miss Abby Cox’s youtube channel, which I highly recommend. This intrigued me, and I decided to find a video I could dissect off my expertise, at first only for fun in my own time. This resulted in the production in a very long bullet list in the notes app of my phone. So here is my informal destruction of this godforsaken video.

Disclaimer: I am not at all excusing any of the awful things Alexander Hamilton did during his lifetime. I am absolutely the last person who would even come near to claiming that many of the things he did were justifiable in the slightest. Although, he might be the only historical figure which I have a very strong interest in the life of, as he was incredibly complex, and the part of me with a love of psychology finds him absolutely fascinating. There is also something to be said about the way we consider moral standards of historical figures. We are quite lucky to believe in the time that we do, and not all of our standards can apply to historical figures. This does not mean they should not be held accountable. I find that a way to criticize people while also praising them where it is due is by judging them based upon their intentions. In my opinion, Hamilton’s intentions were not to harm anyone in most situations, so I don’t think he was a terrible person, nor do I think he was a particularly good one. Then again, I don’t think either of those things about a mass majority of people, so let us proceed without further delay. (Note: I will also be referring to the collective Weird History channel as the Narrator to avoid any mental gymnastics, and all of my knowledge is coming from my memory of Hamilton’s writing and some biographies.)

Automatically, the video starts with mention of the musical, but that just reminds me that many use Ron Chernow’s biography of Hamilton as a basis of their statements about him without utilizing much critical thinking, so I am slightly nervous.

The Narrator then refers to Hammy Ham man as “...one of America’s most undervalued founding fathers...” Now, it is debatable whether or not Mr. Hamilton is undervalued per se, but when it comes to the founding fathers, they are usually undervalued or overvalued. At this point, Hamilton is both.

I shall not subscribe, thank you for the offer though, Mr. Narrator.

Now for the first fact: “Historians don’t know when Hamilton was born.” Yes, this is correct, but I don’t believe this should be labeled as “hardcore”, but perhaps that is just me. One early document indicates that Hamilton was born in 1755, while all later ones point to 1757 as his year of birth. We know Hamilton was not always a completely honest man, so it is possible that he lied.

Also, they show an image of a baby, and I do not know if this is actually Hamilton, but they use a lot of strange imagery, which I found humorous.

“A self-made man born out of wedlock.” Now, this fact could indeed be “hardcore”, if this was not colonial America we are discussing. Hamilton actually wasn’t really special in this regard. Yes, his rise to fame was impressive considering his circumstances, but this wasn’t unheard of.

The Narrator then says that Hamilton’s mother, Rachel Faucette, was “estranged from her husband.” This caused me some confusion as it is a vast understatement. Her ex-husband was absolutely awful to her.

Additionally, they claim that James Hamilton left his family behind for some reason that I did not write in my notes, but the most likely reason that he actually left was because of his awesome debt. James Hamilton also had a history of ambitious pursuits for money, so it would not be extreme to claim that he moved to another island to attempt to make a fortune in some trading endeavor.

They also cease to mention the Stevens family, who housed young Alexander while he was working for Beekman and Cruger, and had a great influence on him, but I digress.

“A college dropout who joined the Revolution.” Once again, this isn’t special. Many rowdy young Whigs left behind their careers and educations for pursuit of military fame in the Continental Army. They also do not mention anything of Hamilton’s expansive military career, which aside from being indicative of primitive research, but would produce more “hardcore facts.”

Although, they do discuss his application to Princeton college, which is interesting enough I suppose, although everyone who has heard the first two songs of the musical knows this story. His proposal for an “accelerated course of study” was likely inspired by Aaron Burr, as claimed by Chernow and Miranda, or James Madison, as supported by evidence provided by author Noah Feldman in his novel, The Three Lives of James Madison, which is an excellent read. Young Madison, having already completed a course, decided to do so again, but compacting a usually three year course into a shorter period of time. He hardly slept during this period, which was stressful upon his health, making Princeton more disinclined to allow a similar course to be taken.

The Narrator then claims that Hamilton “formed his own militia of 25 men.” Technically, yes? But not exactly. Hamilton joined a paramilitary group called the Hearts of Oak, and they drilled in Trinity Churchyard. This became ironic later. He then became a captain in the New York Artillery Company, and enlisted his own men, which was at one time around thirty or so, if my memory serves me correctly.

“Founded a bank that existed for over two centuries.” Ah, yes, a very hardcore fact indeed. Yes, Hamilton did establish the Bank of America, but Robert Morris was the one who inspired him to do so. Though, I do think the financial plan is a product of his own genius, but I will get into that much later.

I got an ad. :(

The Narrator also says that the misfortunes done to the New York shipping industry by the Articles of Confederation were the most prominent, if not sole, motivation for Hamilton to concoct his financial plan. He first recognized the need for a sound financial plan when he was in the army. You know, when he was watching men die of inadequate supplies because the government couldn’t tax the states.

This video, like Chernow’s biography and Miranda’s musical, claims that Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr were friends when, in actuality, they weren’t really. Yes, they knew each other, and they didn’t hate each other until the end of Hamilton’s life, but they really didn’t think about each other much before the Election of 1800.

“Hamilton authored over half of the Federalist Papers.” Indeed, he did! I enjoy this fact. It isn’t very “hardcore” but it is very impressive. The Federalist Papers were arguably Hamilton’s greatest accomplishment, as he organized the entire thing and, as previously stated, authored much of them. I very much enjoy the Federalist Papers, as they give some insight as to Hamilton’s political and philosophical theories, as well as how he thought of the world. It makes for an interesting read if you have something you’re looking for.

Now, this may be a hot take, but Madison’s essays are by far more effective, as they were better organized. Hamilton and I share a common flaw, and that is the lack of brevity.

“Involved in America’s first sex scandal.” Yes, we all know. I’ll get into the Reynold’s affair later because it’s its own beast to conquer. Basically what you need to understand information I shall provide later in this post is that James Reynolds extorted money from Hamilton, and if Hamilton failed to pay, Reynolds would expose the affair Hamilton was having with his wife, Maria. Hamilton paid, but when Reynolds was arrested for something else, he exposed Hamilton anyway.

“He worked with Aaron Burr to defend a man.” Once again, this isn’t very surprising. They were both capable lawyers in the same area, so it was basically inevitable. Though there was this one instance where Hamilton and Burr were working on a case together and Hamilton, being himself, insisted upon having the last word. Well, Burr was tired of him, and I can’t say I blame him, so he made every possible argument in his finishing speech, leaving Hamilton with virtually nothing.

The Narrator also mentions Hamilton’s opposition to slavery, but he didn’t really outwardly oppose it as much as you would think listening to the musical or reading Chernow’s biography. Far from being the “fervent abolitionist” Chernow and Miranda glorify, Hamilton didn’t really do much for the enslaved. He helped John Laurens in his Black Plan and joined the Manumission Society, but other than that, he never made any attempt to progress the abolition of slavery. He also “purchased” slaves for his in-laws, and some argue that he “owned” some himself, but there is no contemporary evidence to support this that I have seen. The enslaved and servants that were in his household likely belonged to his wife.

“Founded a newspaper that still exists.” Ok.

“Died by duel.” I swear, this fact is by far the most unnecessary. They mention the duel so many times that it is already redundant. I completely skipped over this part, and the video ended, so I was thoroughly underwhelmed.

Well, seeing as this post is already longer than my attention span, I shall save you the pains of having to read any more in just one post. I shall make a follow-up to this where I give my own facts, which I believe are far more hardcore than “he founded a newspaper.” I hope you have enjoyed and this isn’t too terribly boring. I hope to get back to posting soon.

#alexander hamilton#eliza hamilton#hamilton#hamilton the musical#hamilton the movie#lin manuel miranda#ron chernow#aaron burr#maria reynolds#james reynolds#james madison#thomas jefferson#john jay#weird history#abby cox#American Revolution#amrev#amrev history#american history#american colonies#america#the american revolution#The American War of Independence#colonial america#hamilton burr duel#duel#omg im so tired of planning and writing this but im pushing through for the sake of accurate portrayals of real people#im carrying the weight of the world all of you should be thanking me#is it awkward if i listen to how stands the glass around while i write this

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

scandalous star: ira aldridge - an analysis

“A child of the sun, black my countenance, yet I stand before you in the light of my soul.” - Ira Aldridge

He was the most visible black man in a white world in the middle of the nineteenth century. This remarkable man, Ira Aldridge, was a black freedman New Yorker who moved to England when he was in his teens, and achieved immense fame in mid-nineteenth-century Europe as a Shakespearean actor, mesmerizing kings, emperors, and, it would seem, Richard Wagner with his renditions of Shakespeare. He was especially popular in Prussia (now modern-day northern Germany) and Russia, where he received top honours from heads of state. Aldridge's acting career took off at the height of the abolition movement. He chose to play a number of anti-slavery roles and often addressed his audiences on closing night, speaking passionately about the injustice of slavery. During his lifetime, Aldridge successfully challenged preconceived notions about the capabilities of Black people, but unfortunately his legacy faded from public consciousness after his death; he is now much more obscure, revealing the paradoxes of a man who falsified his biography, toyed with audiences, and undermined the racial assumptions of his age. Considered the first Black tragedian, Aldridge is an icon of the African-American theater and a source of inspiration for African-American actors, especially those of the stage.

Ira Aldridge, according to astrotheme, was a Leo sun and Pisces moon (the moon is speculative). Aldridge was born in New York to free African Americans, his father was a reverend at a local Black church and encouraged his son to follow in his footsteps. Aldridge studied at the New York African Free School, where he cultivated an interest in theater. Founded by the Manumission Society and abolitionists such as Alexander Hamilton, the institution intended to educate the children of enslaved individuals and free people of colour. As a teenager, Aldridge became affiliated with a Black theater community in lower Manhattan, and by the age of 15, he joined the short-lived African Company in 1821. Due to extreme racial discrimination in the United States, and finding no adequate outlet for his ambition in New York, Aldridge decided to set sail for Britain in 1824. While both Aldridge and his reviewers downplayed his American identity, Aldridge emphasized his African heritage, allowing it to become part of his theatrical trademark. In 1825, at the age of 17, he debuted as Othello in a small London theater and continued to star in abolitionist melodramas. He became known as a brilliant tragedian and comedian on stage and was dubbed the 'African Roscius' (referring to the great Roman actor) by enthusiastic theater reviewers. The British public's reception towards Aldridge was mixed. While his fame and popularity swelled, he was also shunned and ridiculed for his accent, mannerisms and skin colour. In African-American circles, Aldridge quickly became a legendary figure.

Before earning the part of Othello, Aldridge had been cast as a mythical African prince in an adaptation of Thomas Southerne's Oroonoko; his impressive skill, charisma and oratory capabilities inevitably swayed public opinion. He became known for directly addressing the audience about the injustices of slavery on the closing night of his play at a given theater. After Aldridge's debut at London's most prestigious theater, some reviewers protested about a Black actor appearing on stage. It is likely that the rare sighting of a person of colour on stage – and not as an enslaved person or servant – fascinated British audiences, especially as Aldridge's eloquence and talent would have undermined racist assumptions underpinning nineteenth-century attitudes. Aldridge spent much of the 1850s on the Continent, touring the Austro-Hungarian empire, Germany, Prussia, Switzerland, Poland and eventually travelling to Russia in 1858 where he was well received. Upon returning to England in the 1860s, he applied for British citizenship. His personal life was just as eventful as his professional one –in 1856 Aldridge was successfully sued by actor William Stothard, who alleged Aldridge had had an affair with his wife Emma three years before, resulting in the birth of a son. Although his white English wife, Margaret Gill, bore no children (their marriage angered the pro-slavery lobby, which attempted to end Aldridge's career), it is believed that he fathered at least six children by three other women, one of whom became his second wife, a Swede named Amanda von Brandt. Two of his daughters, Luranah and Amanda, became professional operatic singers. By the time of his death in 1867 visiting Łódź, Poland, Aldridge was an acclaimed and award-winning stage actor and the most visible Black figure in Europe. He had appeared on stage in more than 250 theatres across Britain and Ireland, and more than 225 theaters in Europe.

Next, I focus on a light-skinned black actress who was “too light to be black” yet not accepted in the white world; she instead fought on the front lines for civil rights for blacks. The criminally forgotten Capricorn Fredi Washington.

STATS

birthdate: July 24, 1807*

*note*: due to the absence of a birth time, this analysis will be even more speculative

major planets:

Sun: Leo

Moon: Pisces

Rising: unknown

Mercury: Leo

Venus: Virgo

Mars: Libra

Midheaven: unknown

Jupiter: Aquarius

Saturn: Scorpio

Uranus: Libra

Neptune: Scorpio

Pluto: Pisces

Overall personality snapshot: He had star quality but privately preferred to be a wallflower. He had a strong need for excellence and social approval, yet he honoured his own private, individual values more – and perhaps even came to expect there to be a conflict between his moral integrity and the demands of his audience. Very impressionable and easily moved by suffering, he was a mixture of self-assured certainty and oversensitive, confused uncertainty. Sometimes self-denying and withdrawn, other times autocratic and wilful, he had a great longing to belong as well as a strong need to be actively useful. When he combined these two sides, he was one of the most poetic and creative of all combinations with a spontaneous and childlike delight in the world, an immense sense of fun and a capacity to translate experience into words and colourful images. He could sometimes feel torn between his desire for plenty of peace and privacy, and his need for worldly success and the affection and approval of people he loved and respected. He had an essentially artistic temperament and needed to learn how to be his own best friend – how to look after his own best interests – as he was so easily drawn towards looking after others.

Whether or not he was overtly religious, there was a strongly reflective and devotional side to his nature. He may have even felt that it was nothing less than every human being’s duty to realize his or her immense spiritual potential. At the same time, he never lost his compassion for people and their problems and failures. He knew himself how he went through phases of striving and then retreat, successful self-expression and then, perhaps, a refusal to play the game if the cost to his integrity was too high. He could be severely shaken by the ways of the world, and yet it would be unhealthy for him to relinquish her active role altogether. Full of ardour and deep feeling for life, he was the lion-hearted mystic, the gentle king, the gullible sweetheart who would not harm a fly, the flamboyant, fiercely loyal friend who shared others’ sorrows and successes with equal intensity. He was courageous in the face of difficulties, ever true to his word through thick and thin, and dignified and hopeful even when pain absorbed him utterly as it was wont to do quite often. Changes of mood were his way of life, and if he could make them fodder for his creative imagination, they would have served her well. As a writer, a poet, an actor or any kind of artist, he indulged in his feelings dramatically, and readily transposed his inner life out into the world.

He was ambitious, sound at giving orders, carried responsibility well and was a good teacher, especially able to bring out the best in children. He believed in himself and generally knew the right thing to say at the right time, although he could show a stubborn and dogmatic side. He had a high opinion of his mental powers, and it was certainly true to say that he had plenty of mental energy. His sometimes erratic behaviour depended on his mood. He tended to have very strong intuitions about things and generally felt optimistic about the future. This gave him faith in his ability to succeed, and he could be very impatient with those who gave up without at least trying. He showed strong imagination and originality, and felt that by using his intellect to create, analyze and develop new ideas, he was allowing herself to grow. His mental abilities were likely to be the strongest and best expressed in the sciences, music and philanthropy. He was socially adept and enjoyed an extensive social life, although it may have operated on a fairly superficial level. He had strong reserves and a powerful sense of purpose. He was very serious when he set about achieving something, not wasting his time with useless efforts. He had enormous expectations of himself and of other people, and could be an extremely hard taskmaster. Sometimes he lacked flexibility and had a tendency to brood. He had a strong will, deep strength and force to his personality. Although he had great depth of feeling, he had enormous difficulty in expressing it.

He belonged to a generation that brought unconventional attitudes to marriage and close emotional relationships, believing in the equality and freedom of both partners. Personal relationships tended to be made and unmade fairly quickly. Civil rights were also an extremely important issue. As a member of this generation, he had some unusual artistic talents. He belonged to generation that showed a great interest in occult and metaphysical matters, but it was a generation that never seemed to be able to find complete satisfaction. As a part of this generation, he had a strong imaginative energy source, coupled with a very strong personal morality. As a child of this generation, Aldridge expressed an emotional intensity in his beliefs. Aldridge was part of a generation that was easily led astray by fantasy, and drugs and other addictive substances. Spirituality and religion were important to this generation, as well as compassion and the welfare of those around them, in particular their emotional welfare.

Love/sex life: He wanted sex to be real, tangible, and easily accessible. For this reason he was prone to divide his sexual contacts between those that served his physical needs and those that involved his search for the perfect relationship. His approach to the former was practical and matter-of-fact while he would look to the latter with dreamy fascination. This dual approach certainly did not make sense to everyone. Many people, including some potential partners, were apt to call him insensitive, along with a few other, less printable names. His attitude toward sex was essentially passive and downright lazy. Whether he was looking for love or just a good time he was easily led, emotionally lazy, and sometimes opportunistic. This lack of initiative made it difficult for him to find the perfect love that was always his utmost goal. Relationships of this sort require great energy and determination and there was a part of him that would always balk at such extraordinary effort. But if he was lucky enough to find a partner who was willing to do most or even all the work for him, he could be a lover well worth keeping.

minor asteroids and points:

North Node: Sagittarius

Lilith: Pisces

His North Node in Sagittarius dictated that he needed to prevent his idealism from influencing his thoughts to such a high degree. He needed to consciously develop a more clear-minded and analytical approach involving his thought processes. His Lilith in Pisces was a powerful muse in his life as an innovative male thinker; he was dangerously attracted to women who were natural born mystics and cultivated their own myth.

elemental dominance:

water

fire

He had high sensitivity and elevation through feelings. His heart and his emotions were his driving forces, and he couldn’t do anything on earth if he didn’t feel a strong effective charge. He needed to love in order to understand, and to feel in order to take action, which caused a certain vulnerability which he should (and often did) fight against. He was dynamic and passionate, with strong leadership ability. He generated enormous warmth and vibrancy. He was exciting to be around, because he was genuinely enthusiastic and usually friendly. However, he could either be harnessed into helpful energy or flame up and cause destruction. Confident and opinionated, he was fond of declarative statements such as “I will do this” or “It’s this way.” When out of control—usually because he was bored, or hadn’t been acknowledged—he was be bossy, demanding, and even tyrannical. But at his best, his confidence and vision inspired others to conquer new territory in the world, in society, and in themselves.

modality dominance:

fixed

He liked the challenge of managing existing routines with ever more efficiency, rather than starting new enterprises or finding new ways of doing things. He likely had trouble delegating duties and had a very hard time seeing other points of view; he tried to implement the human need to create stability and order in the wake of change.

house dominants:

10th

1st

2nd

His ambition in relation to the outside world, the identity he wished to achieve in regard to the community at large, and his career aspirations were all themes that were emphasized throughout his life. All matters outside the home, his public image and reputation were very important to him. His attitude to people in authority, and how he viewed the outside world, as well as the influence of his mother and his own attitude to her was highlighted. His personality, disposition and temperament is highlighted in his life. The manner in which he expressed himself and the way he approached other people is also highlighted. The way he approached new situations and circumstances contributed to show how he set about his life’s goals. The general state of his health is also shown, as well as his early childhood experiences defining the rest of his life. The material side of life including money and finances, income and expenditure, and worldly goods was emphasized in his life. Also the areas of innate resources, such as his self-worth, feelings and emotions were paramount in his life. What he considered his personal security and what he desired was also paramount.

planet dominants:

Sun

Saturn

Venus

He had vitality and creativity, as well as a strong ego and was authoritarian and powerful. He had strong leadership qualities, he definitely knew who he was, and he had tremendous will. He met challenges and believed in expanding his life. He believed in the fact that lessons in life were sometimes harsh, that structure and foundation was a great issue in his life, and he had to be taught through through experience what he needed in order to grow. He paid attention to limitations he had and had to learn the rules of the game in this physical reality. He tended to have a practical, prudent outlook. He also likely held rigid beliefs. He was romantic, attractive and valued beauty, had an artistic instinct, and was sociable. He had an easy ability to create close personal relationships, for better or worse, and to form business partnerships.

sign dominants:

Leo

Scorpio

Capricorn

He loved being the center of attention and often surrounded himself with admirers. He had an innate dramatic sense, and life was definitely his stage. His flamboyance and personal magnetism extended to every facet of his life. He wanted to succeed and make an impact in every situation. He was, at his best, optimistic, honorable, loyal, and ambitious. He was an intense, passionate, and strong-willed person. He was not above imposing his will on others. This could manifest in him as cruelty, sadism, and enmity, which had the possibility to make him supremely disliked. He needed to explore his world through his emotions. He was a serious-minded person who often seemed aloof and tightly in control of his emotions and his personal domain. Even as a youngster, there was a mature air about him, as if he was born with a profound core that few outsiders ever see. He was easily impressed by outward signs of success, but was interested less in money than in the power that money represents. He was a true worker—industrious, efficient, and disciplined. His innate common sense gave his the ability to plan ahead and to work out practical ways of approaching goals. More often than not, he succeeded at whatever he set out to do. He possessed a quiet dignity that was unmistakable.

Read more about him under the cut:

Ira Frederick Aldridge was the first African American actor to achieve success on the international stage. He also pushed social boundaries by playing opposite white actresses in England and becoming known as the preeminent Shakespearean actor and tragedian of the 19th Century.

Ira Frederick Aldridge was born in New York City, New York on July 24, 1807 to free blacks Reverend Daniel and Lurona Aldridge. Although his parents encouraged him to become a pastor, he studied classical education at the African Free School in New York where he was first exposed to the performance arts. While there he became impressed with acting and by age 15 was associating with professional black actors in the city. They encouraged Aldridge to join the prestigious African Grove Theatre, an all-black theatre troupe founded by William Henry Brown and James Hewlett in 1821. He apprenticed under Hewlett, the first African American Shakespearean actor. Though Aldridge was gainfully employed as an actor in the 1820s, he felt that the United States was not a hospitable place for theatrical performers. Many whites resented the claim to cultural equality that they saw in black performances of Shakespeare and other white-authored texts. Realizing this, Aldridge emigrated to Europe in 1824 as the valet for British-American actor James William Wallack.

Aldridge eventually moved to Glasgow, Scotland and began studies at the University of Glasgow, where he enhanced his voice and dramatic skills in theatre. He moved to England and made his debut in London in 1825 as Othello at the Theatre Royal Covent Garden, a role he would remain associated with until his death. The critic reviews gave Aldridge the name Roscius (the celebrated Roman actor of tragedy and comedy). Aldridge embraced it and began using the stage name “The African Roscius.” He even created the myth that he was the descendant of a Senegalese Prince whose family was forced to escape to the United States to save their lives. This deception erased Aldridge’s American upbringing and cast him as an exotic and almost magical being.

Throughout the mid-1820s to 1860 Ira Aldridge slowly forged a remarkable career. He performed in London, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Bath, and Bristol in King Lear, Othello, Macbeth, and The Merchant of Venice. He also freely adapted classical plays, changing characters, eliminating scenes and installing new ones, even from other plays. In 1852 he embarked on a series of continental tours that intermittently would last until the end of his life. He performed his full repertoire in Prussia, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Hungary, and Poland. Some of the honors he received include the Prussian Gold Medal for Arts and Sciences from King Frederick, the Golden Cross of Leopold from the Czar of Russia, and the Maltese Cross from Berne, Switzerland.

Aldridge died on August 7, 1867 while on tour in Lodz, Poland. He was 60 at the time of his death. Aldridge had been married twice and left behind several children including a daughter named Luranah who would, in her own right, go on to become a well-known actress and opera singer. There is a memorial plaque at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stafford-upon-Avon, in honor of his contributions to the performing arts. In 2014 a second plaque was unveiled in Lodz, Poland to honor his memory and legacy. (x)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

To judge from anecdotal evidence, this emphasis on commercial success, alongside or in lieu of pedigree, permitted considerable social mobility, at least by the standards of mainland societies. The future syahbandar of Banten arrived in the city with “nothing to live on, so that he busied himself with vile things to earn his living.”135 The grandfather of the lord of Jepara was “a working man [who] . . . went to Malacca with very little nobility and less wealth.”136 The ruler of Demak descended from a slave, as did the admiral of Melaka.137 Although all Malay-speaking city-states used slave labor, such bondsmen were readily assimilated to the free population through a mix of Muslim conversion, frequent manumission, and the custom whereby slaves hired themselves out, keeping up to half of the profits for themselves.138

135 Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 240, citing an early Dutch account.

136 Cortesao, Suma Oriental, vol. I, 187. 809

137 Cortesao, Suma Oriental, vol. I, 184, and vol. II, 249.

138 Reid, “Negeri,” 424–26; Anthony Reid, ed., Slavery, Bondage and Dependency in Southeast Asia (New York, 1983), 1–43, 156–215; Lombard, Carrefour Javanais, vol. II, 131–62.

1 note

·

View note

Note

curious as to your take on the current debate going on in hamiltonia re: hamilton a slaver vs hamilton not a slaver?

Whew, this is going to be a long answer. Since Jessie Serfilippi’s “As Odious and Immoral A Thing” was first published (I posted a few brief quotes here), likely as part of an ongoing interest in the Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site with the subject of the Schuyler and Hamilton families and slavery (see here for blogposts labeled ‘slavery’ including a couple about AH specifically), there have been three versions of a rebuttal by Michael E. Newton and some people calling themselves Philo (”Love”) Hamilton, one of whom is Doug Hamilton*. The ongoing engagement on this topic also brings up issues of historiography and hagiography.

In this whole discussion there is only one new piece of evidence that Serfilippi has referenced on Twitter but is not part of her article - I’ll get into that below. Everything else is a re-analysis of known and fairly popular sources, so I don’t think going through it point by point would be helpful.

But let’s be clear about something. This discussion around AH is in large part because of this Chernow falsehood: “[f]ew, if any, other founding fathers opposed slavery more consistently or toiled harder to eradicate it than Hamilton.” Chernow also calls AH a “fierce abolitionist” and a “staunch abolitionist” because Chernow doesn’t know what abolitionism is. This lie got tons of mileage with Lin-Manuel Miranda, whose musical character AH may have personal moral defects, but not blind spots as huge and disastrous to a modern audience as a lackadaisical approach to the owning of other human beings. (That Miranda’s approach totally riled some Black artists and scholars is well-known, and I wrote briefly about it here.) Serfilippi’s article doesn’t get the media play it does without the popularity of the abolitionist Founding Father myth that Miranda put on stage. So this conflict and news-cycle interest arose from Chernow’s need to give AH the moral high ground by claiming that he was the best best best abolitionist because Chernow is interested in hagiography, not biography. Unfortunately, Newton-Hamilton seem interested in the same thing.

A brief note on word usage: an enslaver, in most current usage, is defined as someone who participated in any aspect of the slavery enterprise. Considering AH’s undisputed role as money-handler (or the more laughable ‘he was a banker’ assertion in the Newton-Hamilton essay) for members of the Schuyler family acquiring enslaved persons, AH was an enslaver.

In my opinion, on the issue of slavery, AH is damned by his extensive ties from 1780 onwards to the Schuyler family. There’s nothing that can explain away the fact that AH at times lived with, visited, and sent his wife and children for extended stays and to be educated by his slave-owning in-laws. AH did not somehow become innocently involved in slave trading and ownership. Rather, he knew what he was doing when he married into the heavy slave-trading and owning Schuyler family and when he engaged in business acts for that family, including helping them to acquire/sell enslaved persons. These were morally weighty - and abominable acts, argued even in his day - and he did them anyway. There is not any record that remains that he had a problem having his children reared within an abhorrent system/household where people were enslaved and served them; in fact, given the number of times he sent his children to his father- and mother-in-law’s home for extended periods, it could be suggested he found nothing morally objectionable going on there. Philip Hamilton even thanked his enslaver grandfather for his advice on how to “be a good man.” P. Schuyler’s wealth and trading was through the slavery economy. Moreover, AH’s economic concerns were also inextricably tied to slavery - keep in mind that every mention of tariffs on sugar is connected to the slave trade. Almost everything led back to that evil institution.

During AH’s lifetime, a number of white AND Black persons articulated that all enslaved Black and Indigenous persons should be freed, that the practice of enslavement was a grave moral failing. AH was well-informed enough to know that Black Americans were articulating how freedom should be applied to them - indeed, many of the manumission policies of the original states arose from these efforts. So AH was fully aware of the arguments. (His son was involved!) Maybe this helped inspire him and his slave-owning friends and political colleagues to form the NY Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, although none of this group agreed to give up their own enslaved persons as part of the organization of this group.

Or, as Newton-Hamilton audaciously state, “[AH] was more involved in building a nation” sotto voce based on enslavement and racial distinction than he could be bothered to care about the lives of enslaved people. This shouldn’t be a surprise when it comes to AH’s major moral failings/blind spots - he didn’t care about the lives of the people affected by his whiskey tax either. If one wants to nevertheless call this a “good man,” we’re probably looking at each other from across a void.

But this is well-trod territory. Several articles post-Chernow have evaluated and summarized positions on AH and slavery that I share:

“Hamilton's position on slavery is more complex than his biographers' suggest. Hamilton was not an advocate of slavery, but when the issue of slavery came into conflict with his personal ambitions, his belief in property rights, or his belief of what would promote America's interests, Hamilton chose those goals over opposing slavery. In the instances where Hamilton supported granting freedom to blacks, his primary motive was based more on practical concerns rather than an ideological view of slavery as immoral. Hamilton's decisions show that his desire for the abolition of slavery was not his priority.” Michelle DuRoss, “Somewhere in Between: Alexander Hamilton and Slavery,” Early American Review, 2011 [part 1, part 2]

“But it does illustrate something that his primary modern biographers have been reluctant to concede: Hamilton routinely subordinated his antislavery inclinations to other family and political concerns, and he did not ever approach even a modest level of engagement on the issue in his otherwise voluminous published works.” Phil Magness, “Alexander Hamilton’s Exaggerated Abolitionism,” 2015

“He was not an abolitionist...[h]e bought and sold slaves for his in-laws, and opposing slavery was never at the forefront of his agenda.” Annette Gordon-Reed, “Correcting ‘Hamilton’,” Harvard Gazette, 2016.

Serfilippi extends this:

When those sources are fully considered, a rarely acknowledged truth becomes inescapably apparent: not only did Alexander Hamilton enslave people, but his involvement in the institution of slavery was essential to his identity, both personally and professionally.

I have no objection to her statement. We simply have no record of AH strongly challenging the institution of slavery, while several of his colleagues and friends most certainly did. Instead, we have the financial transactions, the possible use of enslaved labor, and the possible ownership of enslaved persons, alongside his strong personal, professional, and political ties to owners of enslaved persons. And the new evidence: the inclusion of the following in a list of persons dead of Yellow Fever in NYC 1798, “Hamilton Alexander, major-general, the black man of, 26 Broadway” An Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in the City of New-York, 1799. We cannot know if this was an enslaved man or a free Black man who lived and labored for the Hamiltons, but it should eliminate anyone confidently stating that the Hamiltons did not own enslaved persons.

Thus, Serfilippi has successfully accomplished at least one important goal: bringing to the forefront the names (as we have them) of persons, servant or enslaved, connected to the Hamiltons.

I wrote above that part of the problem here is hagiography. If his concern is with the truth, I certainly look forward to Newton’s chapter-by-chapter repudiations of books written by Chernow, Brookhiser, and Knott on AH and the AH/GW relationship.This leads to the second issue that has arisen: the unprofessional, and frankly gross, glee in trying to punch down on a young female scholar. In my own field (an ex-partner is a military historian so I’ll speak for their field too), the approach when one believes a colleague is publishing in error and one has additional information that could illuminate the issues is to contact them and seek to work together to analyze and draw conclusions. Newton and the anonymous Love Hamilton clan didn’t treat Serfilippi as if she were deserving of this respect. Moreover, Newton has never, to my knowledge - and I purchased his books! - gone this hard after Chernow, who certainly deserves it even more.

But Newton-Hamilton betray their own concerns here: “Considering the era in which Hamilton lived, the challenges he faced, and his accomplishments, it is not difficult to understand why Hamilton did not make opposition to slavery his primary focus. His attention was on building a nation.” And what kind of nation was that? At the Constitutional Convention, AH’s lengthy speeches on the formation of the government have been recorded. There is no record of him offering any statements about the slavery issue, unlike his friend Gouverneur Morris.

Newton-Hamilton continue: “Unfortunately, that meant neglecting other important matters, not just slavery but also his own financial well-being.” Wow, a comparison is made between AH’s personal finances and the ownership of human beings. Could these authors be any clearer that the slavery issue is an inconvenience that they are ultimately unconcerned about? I’m unsure if Newton-Hamilton realize just how gross their attempt at addressing this issue has been, and that it’s hard to take their interpretation and analysis of the evidence seriously when these are the kinds of statements making their way into the rebuttal essays.

Now there is an interesting discussion about how even later abolitionists did not see a conflict in the employment of enslaved labor, but that too isn’t something that Newton-Hamilton show interest in. Instead, their approach seems to be that AH needs to be celebrated at all costs, and thankfully, those days are passing into history.

*It’s ridiculous that a group of people have given themselves a stupid pseudonym to avoid attaching their actual names to a so-called scholarly article. And I’m aware that I’m writing this anonymously, but on tumblr where maybe 5 people have made it to the end of this (I’m not publishing it on my real blog).

**I will not link it, but it can be found on Newton’s blog discoveringhamilton.

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

First of all I want to say that I am new to this fandom so if the question is wrong or bothers you, please understand and I sincerely apologize.

When I was on AO3 I saw a fic about Henry Laurens/Alexander Hamilton, I was surprised and curious. I thought that Henry (or Harry?) was John's brother until I read it.

So I just want to ask if Henry Laurens (the father) and Alexander Hamilton have any relationship or not? Because this is history, real people, sometimes I can't understand some ships (I respect it if it's yours but I just don't get it)

Once again, thanks for listening to me.

(sorry for my bad English)

There were three Henry Laurens'. Henry Laurens Senior, the father; Henry Laurens II, the firstborn of the Laurens family who died at age of fifteen; and Henry Laurens Jr., who was the sixth born of the Laurens children.

Hamilton and Henry had met a couple of times throughout the revolution, and of course, Henry heard about Hamilton from his son, John Laurens, who was a fellow soldier and romantic lover to Hamilton. There was brief correspondence between the two, but any actual bond between them would have been post-war.

In April 1785, Hamilton represented a man named Frederick, who petitioned the Manumission Society, claiming that he was being unlawfully detained as a runaway slave in a New York jail, despite having fought in the Revolution alongside Colonel John Laurens in South Carolina — and thereby winning his freedom. Perhaps drawn to the case due to his close relationship with Laurens, Hamilton immediately sent a letter to Henry Laurens about the case. You can read a summary about that all here though. Although it's not determined wether Hamilton ever found this out or not; but Henry did lie and manipulate Hamilton during that case.

He writes to Hamilton claiming;

“—the time is when I only wish to collect my Family. It would grieve me to hear he was enslaved by any one, who has a shorter claim of property in him than I have. I wish to give him a chance of being rescued from Slavery.”

(source — To Alexander Hamilton from Henry Laurens, [April 19, 1785])

But just later, Henry had told a different story to his attorney, Jacob Read;

“I hereby vest you with full power to act therein on my behalf, by selling the said Negro for the best price to be obtained, or if practicable to Ship him for Charleston will be best.”

(source — Henry Laurens to Jacob Read, [July 16, 1785]. Via; The Papers of Henry Laurens)

And I believe they never spoke to each other, or worked on any cases again. As for ships, there's a lot of them; many weird, gross, adorable, etc. Like any fandom, it has its bad apples of just downright odd ships — and the Amrev fandom is no exception.

#amrev#american history#american revolution#alexander hamilton#historical alexander hamilton#henry laurens#history#letters#new york manumission society#queries#sincerely anonymous#Cicero's history lessons

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

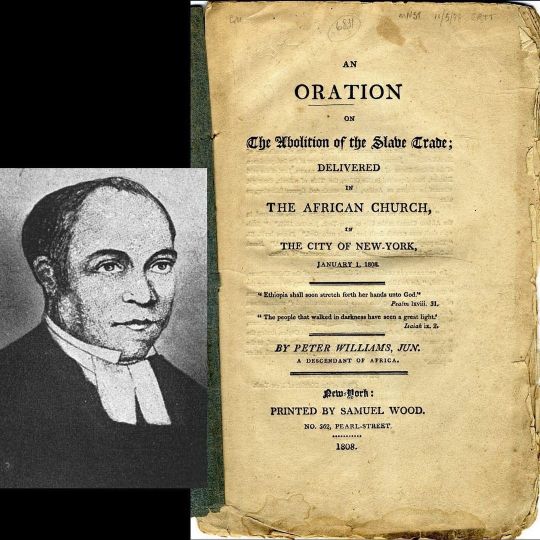

Peter Williams Jr. (1786–1840) was an African-American Episcopal priest, the second ordained in the US and the first to serve in New York City. He was an abolitionist who supported free African American emigration to Haiti, the black republic that had achieved independence in 1804 in the Caribbean. In the 1820s and 1830s, he strongly opposed the American Colonization Society's efforts to relocate free African Americans to the colony of Liberia in West Africa. In 1808 he organized St. Philip's African Church in lower Manhattan, the second African American Episcopal church in the US. In 1827 he was a co-founder of Freedom's Journal, the first African-American-owned and operated newspaper. In 1833 he founded the Phoenix Society, a mutual aid society for African Americans; that year he was elected to the executive board of the interracial American Anti-Slavery Society. He was born in New Brunswick, New Jersey, the son of Peter Williams, a Revolutionary War Veteran, and his wife, an indentured servant from St. Kitts. After his family moved to New York City, he attended the African Free School, founded by the New York Manumission Society. He was taught privately by Rev. Thomas Lyell, a prominent Episcopal priest. In 1796, his father was among the organizers of the AME Zion in New York. It developed as an independent African American denomination, the second in the US after the AME, which was founded in Philadelphia. After the American Civil War, the AME Zion Church sent missionaries to the South and planted many congregations there among freedmen. In 1808 he was chosen to give a speech on the first anniversary of the US' abolition of the international slave trade; his talk was An Oration on the Abolition of the Slave Trade; Delivered in the African Church in the City of New York, January 1, 1808. His speech was published as a pamphlet; it was one of the earliest publications by an African American about abolition. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/CfoQbo5rDlI5VksCMU6sWQh4Io0ya7GtAZsgMI0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m actually curious if there’s exists any assertion about Hamilton owning slaves that predates the musical and the subsequent backlash to it.

Like, you don’t need to assert the claim that Hamilton *owned* slaves to critique his complicity in the wider system of slavery especially since working off historical fact alone you are more than able to critique the milquetoast moderate anti-slavery position Hamilton seems to have had. Maybe it’s because people get things confused with Jefferson and Washington who were plantation owners and owned many slaves or maybe it’s because “Hamilton owned slaves” is just catchier and easier to assert than “Alexander Hamilton was personally opposed to slavery and spoke about this but his actions both personally and publicly demonstrate a widespread, frequent and seemingly at-ease collaboration with the system of a slave society”.

But for me not only do you lose the benefit of being able to rely on historical evidence with the claim Hamilton owned slaves but you lose an opportunity to critique the efficacy of moderate anti-slavery figures such as Hamilton or John Jay (first Chief Justice of SCOTUS and who founded the New York Manumission Society that Hamilton joined and who actually did own slaves) and the notion the institution could easily and gradually be ended in a way agreeable to masters and slaves

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is the worst?

Round 1: Robert Troup vs Henry Knox

Robert Troup (1757 – January 14, 1832) was a soldier in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of New York. He participated in the Battles of Saratoga and was present at the surrender of British General John Burgoyne.

Troup was secretary of the Board of War starting in February 1778, and secretary of the Board of Treasury from May 29, 1779 to February 8, 1780.

Troup was a lifelong personal friend of Alexander Hamilton, with whom he had roomed at King's College and served in the Hearts of Oak militia unit, and he continued to support Hamilton in politics.

Troup was a co-founder in 1785 of the New York Manumission Society, which promoted the gradual abolition of slavery in New York, and protection of the rights of free black people. Despite being a slaveholder himself, Troup presided at the first meeting of the Society. Together with Hamilton, who joined the Society at its second meeting, Troup led an unsuccessful effort to adopt a rule requiring members of the Society to free any slaves that they themselves owned. In the absence of such a resolution, Troup himself waited to manumit his slaves, freeing four between 1802 and 1814.

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following the revolution, he oversaw the War Department under the Articles of Confederation, 1785–1789. Washington, at the start of his first administration, appointed Knox the nation's first Secretary of War, a position he held from 1789 to 1794.

He was formally responsible for the nation's relationship with the Indian population in the territories it claimed, articulating a policy that established federal government supremacy over the states in relation to Indian nations and called for treating Indian nations as sovereign. Knox's idealistic views on the subject were frustrated by ongoing illegal settlements and fraudulent land transfers of Indian lands. He retired to Thomaston, District of Maine in 1795, where he oversaw the rise of a business empire built on borrowed money. He died in 1806, leaving an estate that was bankrupt.

#worst founding father#founding fathers bracket#founding fathers#brackets#amrev#robert troup#henry knox#why do they look like the same man 💀

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

With great satisfaction we communicate to the society the agreeable accounts of the exertions made in different states, and also in Great Britain, towards the emancipation of the unfortunate Africans—That to this end public orations have been made and received with great applause at the colleges of New Haven and Princeton and of Cambridge, in Great Britain, in which the injustice of holding Africans in slavery, hath been depicted in the most lively colors that sound judgment and elegant imaginations could form.

Committee report to the New York Manumission Society, December 9, 1796

#1790s#slavery#abolition#abolitionism#manumission#Princeton#Yale#Harvard#New York#quote#Princetonquote

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

i was reading through your blog and i noticed on one of your posts about whether the hamiltons owned slaves that he expressed life long antislavery sentiments. i've seen it said though that because of his origins that he necessarily wouldn't have been against it, but i'm interested in knowing of evidence for either argument

The development of Hamilton’s antislavery beliefs and their seeming drop off in his later life is a topic to which I’ve given it a lot of thought–hope you’re ready for an essay! Hamilton’s relationship with slavery is complicated. It’s true that Hamilton’s origins don’t seem to lend themselves to his being an opponent of slavery. Slavery was ubiquitous in the Caribbean where Hamilton grew up; in the year 1770, three years before Hamilton left for America, the island of St. Croix held 18,884 enslaved people to 1,515 whites and freedmen.[1] Hamilton himself was raised in a slave owning household: his mother, Rachel Faucette, inherited five female slaves and their children from her father, all of whom she held until her death in 1768. Only the laws of inheritance barring property from passing to illegitimate children stopped him from owning slaves himself at the age of eleven.

After his mother’s death, Hamilton went to work as a clerk for the trading firm Beekman and Cruger. Downstairs behind the firm’s King’s Street office there stood “a large enclosed yard where the newly arrived slaves were auctioned.”[2] Hamilton’s duties as a clerk included writing advertisements for these slave auctions, and recording the sales for the firm. As Willard Sterne Randall summarizes, “In his early life especially, Hamilton benefited from the Caribbean’s slave based economy. He learned to trade and socialize with its richest benefactors, who included not only his own relatives but all his business colleagues.”[3]

However, it’s also during his youth in the Caribbean that the first hints of his opposition to slavery appear. Part of these early leanings away from slavery may have come from the influence of Presbyterian minister Hugh Knox, a close mentor to Hamilton. Though far from an abolitionist, Knox preached against the horrific mistreatment inflicted upon enslaved people by their masters. For example, in one of his published sermons, Knox asked, “If we shew no mercy to those whom God hath put under us, can we expect any other than judgement without mercy from him whose creatures we abuse?”.[4] The imagery of God as a vengeful master wreaking abuse upon the white inhabitants of the Caribbean, as they abused their own servants is echoed in Hamilton’s famous hurricane letter, published in the Royal Danish American Gazette: “That which, in a calm unruffled temper, we call a natural cause, seemed then like the correction the Deity. Our imagination represented him as an incensed master, executing vengeance on the crimes of his servants.”[5] These early stirrings of conscience would only be heightened upon his arrival in America.