#now we're talking about the difference between mass and weight

Text

The rest of my math class : * learning trigonometry*

Me who has stopped absorbing any kind of math past chapter one: *trying to figure out if my teacher actually writes her S's upsidedown or if the ungodly amount of caffeine I consume has actually gotten to me*

#trigonometry#mathclass#shit post#collage is weird#college#i dont know what im doing#on no now theres a word problem#guys i dont know how to do any of the math#why is there science#now we're talking about the difference between mass and weight#this is a trigg class wtf

0 notes

Text

The Consort - Chapter 13 - Part 1

*Warning Adult Content*

Finn

As the weeks pass, the world around us transforms into a macabre whirlwind of chaos, fear and war.

Up until last Thursday, Leo would turn on the news every day so we knew what was happening.

But now the TV announcements have stopped.

Mass communication has stopped.

The last thing we heard from our leader was that all contact between vampires and their consorts was hereby banned.

Above all else, his reinforcing words never wavered, stay hidden and keep safe.

We are at war.

"I'm heading to the store," Fiona announces, shoving away from the kitchen table.

Leo hunches beside the water heater, tinkering with the levers at the top.

A tool belt hangs lazily on his narrow hips.

He doesn't bother glancing up at her before saying no.

"We're running out of food," she argues.

"We'll make do."

"We have been 'making do,' Leo. It's not enough."

Leo sighs and stands, wiping off his hands on the length of his frayed blue jeans.

If it was just the three of us here, we'd have enough food to last another month.

Over the past week, however, seven additional people have shown up at Leo's doorstep... all of them loyal followers to his radical idea of a revolution.

I recognize some of them from class but the rest are all strangers that I no longer have the strength to make small-talk with.

"It's too dangerous," Tony chimes in.

"The last broadcast told us that the vampires are being ruthless. They're dressing up like humans, blending in until they get a chance to advance."

"I'd rather they just attack us," Midge comments from the couch.

She flips a page of her magazine and stares off into the distance.

"Just get it over with, you know? At least then we wouldn't have to be afraid all the time."

All of us glance around at one another.

For the first few days she was here, Midge reminded me of myself.

She's quiet and pensive, not usually one to ruffle feathers.

I even tried approaching her one night after dinner but five minutes into the conversation, I quickly realized we are more different than night and day.

Where my personality is filled with understanding and the netting of an open mind, hers is closed off and wired shut around one thought... kill all the vampires.

"Well while all of you sit around and pilfer through your magazines or debate about your deep-rooted fear of the undead, I'm going to check the store for food. Anyone want to come with me?"

I immediately jump to my feet.

"I'm coming with you."

"No, you're not," Leo says, shutting me down.

Normally Fiona agrees with him and writes me off.

My spirits sink, expecting this time to be no different.

But to my surprise, my old friend meets my gaze from across the room, her eyes dancing over me thoughtfully before smiling softly.

The sight makes me ache.

I haven't seen Fiona smile since the day she found out Kelly changed.

Truthfully, I haven't even really talked to her since that day, either.

Seeing her smile, just briefly, reminds me all the warm memories I shared with her and Kelly.

So much has changed since then and yet in one, slight smile, hope manages to swell in my chest.

"He can come with me," Fiona offers quietly.

Leo walks over to her, his eyes squinting with frustration.

"No, he can't. It's too dangerous."

Fiona rolls her shoulders, unfazed by the foot and a half height difference between the two of them.

"It is dangerous, Leo. You're right. But Finn stays here of his own accord. Our freedom is running thin as it is. If he wants to come with me, that's his choice. Not yours."

Midge gasps from the couch.

There aren't many people who stand up to Leo.

We're staying at his house, after all and he could kick us out at any time.

Not only that but many of us still view him as our Professor, a role where his opinion holds more weight than ours.

Leo purses his lips, staring down at Fiona with a look akin to betrayal.

Then he turns to me and his eyes relax.

"You really want to go?" he asks me.

I nod.

His nostrils flare and he looks down at his tool belt.

This will be the first time I've left his side since the day he brought me here after what happened at the University.

It's not that I'm ungrateful for all that Leo's done for us because I appreciate it more than he realizes.

Really, I do.

I just can't keep hiding in this house without ever getting a chance to really breathe.

"Fine," he grits out.

"Mark, you're going with them."

Mark, an old family friend of Leo's, agrees without protest.

He gets to his feet and starts heading towards the garage door.

Fiona throws me a triumphant wink, one that thankfully goes unnoticed by Leo.

She turns towards the car but Leo catches her by the elbow and yanks her back.

"You keep him safe," he warns.

His tone is minimal but terrifying.

"And if you can't? Don't bother coming back."

Fiona's stumbles back a step.

Neither of us has seen Leo act like this before.

Kelly used to tell me that in tough times everyone's ugliest colors start to show and that the strongest people are the ones who find the courage to overpower it.

"Let's go, Finn," Fiona says.

Her shoulders become rigid as she makes her way to the car.

I follow behind her but hesitate as I pass Leo.

Will he have any warnings for me too?

But Leo doesn't say anything.

Instead his arms wrap around me, pulling me against him so tightly that I can smell the sandalwood soap he used this morning in the shower.

When he releases me, I notice his cheeks are red.

"Be safe," he murmurs.

"I will."

Leo steps aside to let me pass and minutes later, I am in the back seat of Mark's SUV while he pulls out of Leo's driveway.

Once we're out of the subdivision, he cracks the window open just a hair.

The cool air from outside rushes in and I breathe it in longingly.

There isn't a single car on the road but ours.

It's unsettling, the type of thing you'd expect to see in an apocalyptic movie.

I try to shut down the fear as best I can.

My eyes lap up the view of the outdoors, appreciating every color and house that we pass.

"I'm thinking we stop at that little grocery store on Maple," Fiona says from the passenger seat.

Mark's dark eyes dance along the road ahead of us.

"Fine. Just tell me where to go."

Fiona navigates the three of us into town, avoiding the major roads when she can to play it safe.

Mark never questions her directions,but every once in a while I notice his knuckles tightening over the wheel.

A single car passes us just before we reach the grocery store.

There's two women in the car, both of them looking about as terrified as I feel.

Even though I promised myself I wouldn't be afraid, I'm suddenly second-guessing my willingness to come on this little grocery trip.

"We're here," Fiona announces.

Mark pulls into the deserted parking lot.

The grocery store is dark and the front glass doors have been shattered.

Apparently we aren't the first people to come up with this idea.

Fiona grabs a handful of plastic bags and disperses them to both of us.

"We're looking for canned goods, especially," she says.

"But really, anything that is edible and has some sort of nutritional value will be good."

Mark takes the bags from her hands and hops out of the car.

Fiona watches him, her eyes brightening with every step he takes.

I expect her to get out of the car but instead she sits back in her seat and glances at me from the rear view mirror.

"Finn," she says quietly.

"I'm going to ask you this once and only once."

Mark gets closer to the door and turns to make sure we're following.

When he sees we're still in the car, he frowns with confusion.

"When you kissed your vampire, did he kiss you back?"

1 note

·

View note

Note

lmao I used to have a binge eating disorder and ate like 7k calories a day. Crazily enough when I started eating a normal amount of food for my gender/height/activity level I lost weight and my sleep apnea went away, I can now walk up the stairs in my house without excruciating pain, and I have 500x the energy that I used to and my brain fog is 99% gone. But I'm sure being 190lbs overweight and eating until I felt like I was going to vomit was totally healthy and my pain was just a manifestation of my internalized fatphobia or w/e lmao

People must have somehow magically evolved to be morbidly obese in only a few decades, it can't possibly have anything to do with insane portion sizes, mass production and availability of unhealthy food, a food pyramid sponsored by companies wanting to sell you their trash and food now being full of sugar, corn syrup, artificial colors and other garbage. We're also so magical that being fat is totally fine for us unlike the thousands of other animal species in existance.

Keto and intermittent fasting literally saved my life. I was able to go down from 10 DIFFERENT MEDICATIONS to only needing 4 of them. I've literally talked to hundreds of people with the exact same story.

“I traded my BAD eating disorder for a GOOD eating disorder” is not the flex you think it is anon.

By your own admission your issue was having an eating disorder, not being fat, if you think every fat person also has an eating disorder you are projecting your own trauma and insecurities onto other people because you apparently think your experiences are universal. Most fat people do not eat until they puke actually.

The reason obesity is dangerous for a lot of animals is because, get this, animal physiology and adaptations vary greatly between species. Do you think you have the same needs as a flea? Bears, seals, whales, hippos, boars, and several other species have to carry a lot of fat to survive. Humans are bipedal and have fat stores that build up away from organs and joints. This keeps a lot of the strain off the back and prevents many of the issues you will see in quadrupeds and birds from emerging.

Ease and rate of storing fat in humans is largely due to genetics. People who were born by a starving mother naturally hold fat more easily because this is an adaptation to prevent starvation in famines. Increased fat stores is also hereditary so people who had ancestors that were starving will carry weight more often than those whose ancestors had an easy access of food for several generations. Because this was something humans adapted to over the course of millennia as nomadic groups who had to deal with inconsistent food availability due to different climates, flooding cycles, droughts, etc, humans did in fact evolve to have a fluid metabolism and hold stores of fat just fine. If you think fat people are a new invention, I have insane news for you about noble and royal families in Europe for hundreds of years. Being fat was a status symbol to show off how much money you had and that you had no need to toil in fields. This is documented very well.

Keto and [starving yourself] is not healthy. If your entire argument is that being some arbitrary level of “overweight” is unhealthy, you should consider not promoting a diet that causes you to have calcium absorption complications, chronic arterial diseases, kidney stones, and other serious issues long term. Anorexia is not a health trick either, once again, that is an eating disorder.

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to another one of my lectures. Today we're gonna talk about

Galaxy Collisions

The dance of the universe

Featuring L.I.S.A.

As some of you might know (or might not know) pur galaxy is in a course of collision with the galaxy of Andromeda. Of course this colission is gonna happen in about 4 billion years and we're probably not gonna be alive as a species, let alone as individuals. But even if we were, the sun would not collide with anything as proven by computational simulations and observing other collisioms happening right now far far away in our universe. Like, a chance of 1 in 100000000000. You have way more chances winning the lottery when each person on the planet has bought a ticket.

So

What happens?

Let's imagine 2 galaxies. Each one is caught in the gravitational pull of the other, much like everything else in the world. As they draw closer, that pull becomes stronger.

The first thing to part each galaxy is the interstellar gas and dust. This acts like a fluid, particles moving closely together, and is very light in weight so it is easily separated by the main disk of the galaxy. This phenomenon does not require the galaxies to collide, but merely to pass close enough. It results in the creation of "tails" of gas and dust, coming out of the galaxy and stretching out to where the other galaxy passed by.

Here we have an example. This pair of interracting galaxies is called "The Mice" for obvious reasons

Preety huh?

Now. As i said the two galaxies can collide. According to the difference in mass between them we have two cases:

Galaxies significantly smaller are absorbed by the larger one. This is called "galactic cannibalism" (💀). We're currently doing this to the magellanic clouds (if you live in the southern hemisphere you have probably seen them in the sky). Thìs is also probably what andromeda is gonna do to us (Andromeda is visible in the northern hemisphere and about the only galaxy you can really see with the naked eye)

If they're about the same size they crash. Boom:

In any case, interstellar gas and dust are exchanged, the two galaxies become one, the tidal waves compress matter near the center of the galaxy and star formation is triggered. There is a whole category of galaxies called "Starburst galaxies" which are very bright in infrared light (they appear normal in the sky through your optical telescope). These galaxies we predict are the result of such colissions.

Explosive star formation however means that the "fuel" of the galaxy is spend very quickly, and so the galaxy "dies" (meaning no new stars are formed) pretty quickly (meaning a few hundred million years).

MOREOEVER

mg favourite part cause that's what I'm currently specializing in my studies

After such a collisions we end up with two centers of galaxies (meaning their supermassive black holes - enter song by MUSE-) in a common disk. These two INCREDIBLY HEAVY objects orbit each other and affect the orbits of nearby stars. Those stars are so light compared to the black holes tgat are actually SHOT OUT of the galaxy. If the combined mass of lost stars is comparable in terms of size with the mass of the black holes then those two begin to lose torque and end up getting closer. After getting close enough they start producing gravitational waves, causing them to lose even more energy and bringing them closer, until in the end they become one.

Now,

We can't yet detect those. The frequency they produce is too low for our ground detectors and so it is burried under noise and the limitations of the instrument itself.

BUT

in the 2030s a new detector will launch. And i mean that quite litterally, as they will launch it in SPACE. The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA for short. Nice lady) will be comprised of 3 ships positioned equidistantly in the angles of a triangle and will follow a specific path, following the earth around the sun but far enough from the planet. The three ships will be like 50km apart. A laser beam connects them all.

An interferometer uses a phenomenon of light called symbolometry. Depending on the wave's phase, we either see light or darkness in our screens. This is a ground detector:

Ground detectors have "arms" of length of 5km and detect frequencies like 10Hz to 1000Hz or smth like that, i don't actually remember the number. LISA tho, will bave much bigger arms (50km long) covering more space, interracting with a wave more fully and more easily. So, LISA aims to detect waves between 0.1 mHz and 1Hz. It will also be away from other earthly noise, like earthquakes.

One time they almost mistook a signal for a truck passing by and causing the mirrors reflecting the light back to tremble. Yeah. Don't worry, they noticed.

But the future is looking bright. Cause galaxy collisions are a window to the past (since the rate of stat formation is similar to the one we had in the first steps of the universe) and to the future (as i said, it'll happen to us too)

More science

#galaxy colissions#physics#astrophysics#daily lectures#have fun i guess#science#astronomy#gravitational waves#lisa#esa#nasa

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

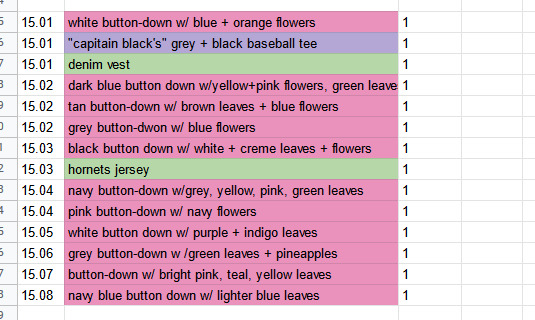

the spreadsheet i keep on mac's wardrobe has been fully updated for s15 ! here are some thoughts about his costume this season bc. idk when you do something like this you start thinking about it a lot

- SO many button downs....

out of 14 shirts this season (vaguely on the higher side but still within average) mac wears eleven button-downs- more or less 78% of his shirts. that's the highest number since their introduction in s7, which is their second most popular season with eight of sixteen/50%. i DO have thoughts about this but they're related to my next point so ill get to them in a second

- another point about these button-downs is that there's a lot of colour. the button-downs have never been muted, perse, but they're particularly bright this season, especially using a lot more pink/purple tones & just generally more vibrant shades.

now. my thoughts.

look back a few lines to what I said about s7- the button-downs are introduced in 07.01 (the a-plot of which is about frank loving the woman he loves no matter what """greater society""" thinks, even if the relationship is unconventional, just by the way) when mac and dennis go pick some up after mac's gotten fat between seasons. mac continues to wear them regularly, dennis, done with the desire to break through from the rigid, emotionally + physically straining/painful labour he puts himself through to adhere to what he believes is expected of him that he expresses during the episode, does not.

in season eight, mac has lost the weight he had gained for season seven. he clearly expresses, primarily in 08.05 the gang gets analyzed though also in throwaway moments throughout the season, that he misses his weight (mass, as he calls it). he's lost it because of (likely dangerous) diet pills that he's tricked into taking by dennis. mac looks back on his fatness as a time of freedom and pride for him, clearly viewing the weight loss as (to a degree) having made him a shell of his former self.

two of mac's ten shirts in season eight are button-downs, putting the rate there at exactly 20%, down 30%. from s8-s14, mac wears five button-downs out of ninety-two shirts, for a rate of roughly 0.05%.

I think that if we're talking about mac's self-expression there's a pretty clear line in the sand to be drawn- 08.01 through 12.06, and 12.07 through 14.10. pre-coming out, and afterward. pre-coming out has a rate of three of sixty-six/0.054%, and afterward has two of twenty-six/0.095%. keep in mind that these numbers should be taken with a grain of salt as they only account for shirts worn for the first time, but a) the number of rewears starts to go down a lot in the later seasons so they're not far off, and b) I believe that they do still accurately represent that the quantity of button-downs is low.

so where's mac at during s8-14?

well, pre-coming out it's pretty obvious what the issue is. he's pre-coming out. coming out is something that isn't inherently necessary for happiness as a queer person, of course, but mac is really really actively repressing who he is pre-hohc, and he's fucking miserable about it.

that middle area of the show, around s7/8/9, is where mac starts to be really actively queer-coded. there's this vague gay aura that's always been present in the show (and still is), but it starts to really focus in with mac around this time, and as a result we get more and more of him being this ball of repression wound so tight that he's about to snap. so there's our answer- despite the freedom he feels in s7 when he lets go of what he's been holding himself to (in a sense), he loses that in s8, and the freedom of the button-downs goes with it.

but from 12.07 onwards, it's a bit of a different beast. mac doesn't know how to be gay.

so much of mac's character is about how he's struggling to fit into his identity. I think there's a bit of a disadvantage here because the handling of mac's character (particularly his identity) in s13/14 is just remarkably horrible, but there is a really interesting thing to be pulled from the wreckage there where mac spent what. forty-odd years ? denying who he is and now doesn't know what to do with himself. so he's free from his denial, yes, but he's not free.

so what's changed with s15 ?

I think that he's finally settling into being gay.

his whole thing in s15 is about finding which part of his identity is most "significant", right? which is it's own identity problem, yeah, but he's almost shockingly comfortable with the fact that being gay is part of him. he tosses it around brazenly in conversation, he openly tells a priest (A CATHOLIC PRIEST IN HIS HOME COUNTRY !!) about his various sexual experiences with men & his attraction to the hot priest, he very openly expresses excitement about "a priest like me" when he thinks the priest he's following is gay.

mac hasn't exactly been shy about his sexuality up until this point, but there's always been this edge to it that.... ok like i said i despise what was done with his character in s13/14 and im loathe to give rcg kudos for it, but i think there's a totally reasonable reading of that where he's weaponizing his outward expression/discussion of his sexuality so that he doesn't have to think about the unresolved pain that's still there. mfhip is a significant step re: catharsis/reconciling his hurt, but there's still that last stretch before he gets to where he is in s15.

and so that's what the shirts are. he's back to the freedom of s7- not only are the button-downs in abundance, but they're brighter than ever before. he feels like himself again, except this time it's on the inside.

#mac mcdonald#iasip#it's always sunny in philadelphia#meta#literally been writing this off and on since eleven am (its five thirty) so there's my day gone i guess#like i got up watched the eps with breakfast went back and skimmed 15.04-08 to finish the spreadsheet and then wrote this#like i did some other things but. yknow#ben.txt

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Delve In The Depths. Chapter II.

Word Count. 1.5k

a/n. Just a quick btw, Meno gave Xiao the nickname "Emerald duck" because emerald ducks have greenish teal stripes on their heads and Xiao has teal undertones in his hair.

Trigger Warnings. Mentions of death and violence

Series Masterlist

Chapter II.

Again and again these waves crash over Xiao's subconscious. Riptides of lost human dreams, the tsunamis of guilt, and the eons of pain build each other up, growing larger as they drown him in endless suffering. Waves of black vapor cloud his person. He clutches his mask

He can hear their screams now as he writhes on the top floor of Wangshu Inn in agony, barely supporting the weight of his body with his arms leaning on the balcony rails.

"Xiao, Xiao!" he turns his head to see Verr Goldet franticly searching for him.

"There's someone downstairs, the-they, Verr Goldet stutters on her words, waving her arms around unlike her usual composed self.

Xiao doesn't wait for to finish, he grabs his pole arm by reflex prepared to strike the threat down.

Instead he's met with a person grappling with pain on the floor.

"Why slime condensate exactly?"

"Hm?" Xiangling gives you a genuinely confused look despite it not exactly being the social norm to add slime liquids to a meal. She was climbing up a sandbearer tree. The striped squirrels on the ground scatter upon her arrival.

"What gave you the idea to add slime into your dishes?" you clarify, trying not to come off as rude. Tossing the wicker basket between your hands as a form of entertainment while your culinary friend ducked her head underneath a branch.

The trees ruffle and flocks of crimson flinches and golden flinches fly off to the sky as Xiangling forages around in the tree branches for bird eggs.

"What gave you the idea that not everything is edible?" she playfully teases, now placing bird eggs by sets of two in the basket she previously gave you in Wanmin Restaurant.

You giggle, covering your hands with your mouth. She motions for you to put the basket down and come over while she grabs you by the shoulders ("Don't you dare-") and hops down. Unfortunately, you aren't heavy enough to support her body weight when she jumps down with her full force.

"Ugh!" you groan as you both tumble down to the floor. You raise a hand to your head and cover your forehead. "Was that really necessary?" you sigh, already far too used to her antics. She snickers.

As you regain your footing, you ask, "How far along are we exactly? My mother will have an aneurysm if we step foot in Moon City.*" Xiangling had already run off, and with the basket no doubt.

You look to your right and find her by the lake counting hydro slimes behind a crack between a few slabs of stone. You crouch down besides her. Her charcoal hair brushes against your mulberry silk skirt.

"1,2,3,4." Yes! this is definitely enough for my new dish!" she pumps her fist in the air.

You don't remember there being a lake to the far right in the places your mother told you to stick to.

"Let me guess," you strike a thinking pose, you want me to set up a new shop here for your new culinary competition?" you sarcastically muse.

She rolls her eyes. "No, silly I-," she stops at your amused expression. "Ah- well go on than."

You reach your arm to summon your now unsheathed dagger attached to the leather belt on your waist, ignoring the long bow and arrows attached on your back and rather choosing a melee weapon,

Standing up from your hiding spot, the group hydro slime flock, well bounce towards you.

The air turns frosty and Xiangling's teeth chatter while she rubs her arms in hopes of warming up. "Don't turn me into a chef popsicle before I get the slime condensate [Name]!"

As you kneel down to slam the stiletto dagger into sand, sharp edged flower patterns appear on the ground. The slimes teeter back at the sound chill between their mass before large icicles spring up, piercing their bodies and turning them into goo.

"Woo!" Xiangling jumps above the rock pile and excitedly cheers. Pumping her arms up. "That's my girl!"

"It was nothing really. What was it you needed next again? Of course after you've collected the slime condensate of course." you stop talking as Xiangling sweeps the slightly frozen slime fluids off the crystals you've created into a glass bottle.

"Well talking about other ingredients, I actually wanted to try something." she mentions with a certain twinkle in her eyes.

"You have my attention." You wave your hand at her to go on.

"You know that cooking competition? The one I had in the Mondstadt with the chef named Brooke?"

"I don't recall you telling me that, can you specify?" racking your brain for memories of Xiangling's rantings about food. You suddenly feel drops of sweat on your back despite not being lukewarm at the very best. It must just be from the excitement from fighting the slimes, you think pushing away your other thoughts on the matter.

"Well anyways, we found this extinct species of boar with the help of the traveler, I believe they're called the honorary knight now?" she taps her chin. "That's besides the point but, anyways, it made me think of the different varieties of possible meat options I could use with different monsters. Can you go with me north of Jueyun Karst with me to find a Stonehide Lawachurl?" She claps her hands together into a begging motion. "Please, Please?"

"Mhm, I'm not sure how fast we can make it there? You didn't hear my question before when I was asking where we were before. I'm planning on packing my bags early when I go home overmorrow." you say counting the possible time it would take you to pack all your belongings. Black spots appear in your vision. You open your mouth to speak, but nothing comes out.

"Hmm, I'd say if we're lucky, a few hours? It's lucky that it's still the early morning huh?" Xiangling turned her attention to you from the mushrooms she was picking underneath the trees.

"[Name]?"

She looks over to see you on your knees, black substance withering out of your body. Sweat drips down your forehead.

She frantically shakes you, but your vision has gone black.

"[Name]!"

The blood on Bosacius' arm dripped to the ground creating a thin string trailing only to be diluted by the pouring rain water behind Bosacius and a certain teal haired adeptus. Bosacius gripped his injured arm with his other.

"You need to treat that wound," Xiao said, glaring at his fellow adeptus' wound. He could see the majority of Bosacius bone creeping out of his flesh. A familiar sight.

"Rest assured, I've been in worse state. I just never expect it to hurt as much as it always does," grimaced Bosacius through his smiling expression. The water soaked through his garments and drenched his hair.

"You sound like one of those mortals, trying to fight through their deathly injuries only not to see the next day," replied Xiao looking forward to their destination of Jueyun Karst. He could see the towering peaks getting larger and larger as they move on despite the misty atmosphere.

"We're all too mortal for our liking these days." said Bosacius, his expression unreadable.

The sound of steps softly crushing the blades of grass underneath them and thunder rumbling filled the air while their owners remained silent.

"Have you told Rex Lapis about the constant pain you've been experiencing?" said Xiao, breaking the silence.

Bosacius bit his bottom lip while his working hands, well, what was left of them tensed up. "No, I didn't see the need to bother him. I'm sure he has other pressing matters to attend to now, especially with the incline in aggression from monsters around Liyue Harbor recently. It's strange," The older man looked up to the sky, while Xiao had a distracted look on his face from thinking about the increased monster attacks. "I have yet to figure out the cause behind it."

"I believe Cloud Retainer and Mountain Shaper are free this evening, I'll ask them for their input on the situation later."

They had arrived at Jueyun Karst, the floating island in the middle of the adepti abode was lit up, symbolizing the availability of Cloud Retainer.

"I'd imagine we don't have the need to place an offering in the middle of the lake huh?" Bosacius winks at Xiao. Xiao looks down at the lake, full of ripple currently from the cloudburst. The empty bowl in the middle overflowed with liquid.

Bosacius gave a forced smile at his correct prediction of their fellow adepti's availability. "Well, I suppose it's best for me to head off and find Indarias to heal my wounds."

"That would be for the best." confirmed Xiao

"Thank you for accompanying me for this trip."

Xiao turned his back and Bosacius was gone

"Hey! Emerald duck!"

Xiao swore he heard the inter layers of hell again as he pinched the bridge of his nose

"Oh archons," he cursed under his breath. Menogias tumbled towards him, no grace or posture in her current childlike state.

*Moon City refers to Mondstadt as Mondstadt translates to Moon City in German.

a/n. Incase anyone was wondering the reader's constellation is "The Maiden" or "Virgo". I'm planning on making a character sheet for the reader soon, so watch out for that!

#genshin impact#genshin imagines#genshin xiao#genshin Zhongli#genshin x reader#xiao x reader#childe x reader#la signora#delve into the depths

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

《Original post here》

Part 2 HERE

SUMMARY: [Supernatural TWD AU] In which Negan is a kinky incubus, Rick Grimes is your secret guardian angel, and Daryl Dixon is a gruff monster/demon hunter. Three drastically different men who can only agree on one thing: making you theirs.

PAIRINGS: Reader x Negan, Reader x Rick Grimes, Reader x Daryl Dixon (Polyamorous Ships)

RATING: Mature/18+/Romance & Smut. Please be prepared and do NOT report.

NOTE: This is actually my first time ever writing an xReader story series as well as writing on Tumblr (I usually only write on Wattpad). As such, it probs won't be perfect though I would SERIOUSLY appreciate your *respectful* feedback and support!

I understand writing xReader content can get a lil tricky, so please just keep in mind that not everything Y/N says or does would be something that you'd do IRL or even approve of. Also, sometimes I may not help but put a teeny bit of myself in Y/N...

Lastly, I recently got back into the TWD fandom after a looong ass time and I'm taking a while re-watching the whole show. So I apologize in advance if my portrayal of any of the characters are rusty or I may not remember too much of the events from the show, but I promise to do my very best and hope y'all enjoy~!! \(^o^)/

DEDICATED TO: The wonderful @blccdyknuckles and @negans-attagirl 💖

"Heavenly Sins"

Part 1

The sounds of laughter and easygoing chatter filled your ears as you walked closer to the church, a light breeze blowing through your F/C floral dress and the sun blinding your eyes. It was Sunday, most residents of the small town of Alexandria having gathered for mass.

It was a day like any other; peaceful and happy, children giggling and chasing each other around as their parents socialized outside before church could start.

Your heels clacking rhythmically on the pavement, you were just about to enter the building before a familiar voice called out.

"Y/N!"

Spinning, a huge smile instantly reached your ears as you saw none other than Carl Grimes waving enthusiastically at you as he jumped out of a car. From the driver's seat, his father soon followed as he stepped out.

Rick Grimes--dedicated sheriff of this fine town. His usual uniform forgone, instead replaced with a casual navy coloured suit. His baby blues met your E/C, flashing you a bright smile of his own that rivalled the sun itself.

Carl was running towards you now, and once in front he gave you a big hug.

"Settle down, cowboy! It's as if you haven't seen me in forever." You chuckled, ruffling Carl's hair affectionately.

"That's 'cause it did feel like forever." Carl pouted, eventually letting go as he looked up at you.

Before you can reply, Rick patted Carl's head and greeted you. "Hey, Y/N. How are things?" He asked in that endearing Southern accent of his.

"Just fine." You nodded, grinning before you couldn't help but let your gaze wander around a bit. "No Judith?"

It was then that Rick's smile faltered, but just barely. You nearly didn't catch it. "No. She's with her mom."

Rick was divorced from his ex-wife, Lori, after he discovered her cheating on him with his also now ex-bestfriend Shane Walsh. After the divorce, Shane and Lori quickly moved to the neighbouring community of Woodbury together and agreed on joint custody of the kids.

It really made your blood boil; you've interacted with Lori only a few times before so you didn't really have much of an opinion on her...that is, until, you learned what had happened between her and Rick. You knew it wasn't any of your business, but you cared about Rick a lot and he sure as hell didn't deserve to get cheated on.

"Oh." Was all you could say, quite stupidly. Your cheeks reddened, mentally slapping yourself before clearing your throat. "Will I see her in the daycare tomorrow, though?" You were a daycare teacher and even though you loved all of the kids, Judith was your favourite. She was simply such a sweetheart.

Rick nodded, his smile softening. "You got it."

You couldn't continue the conversation as the bells rang, making you jump out of your skin. Carl, noticing this, laughed which made you playfully roll your eyes before slinging an arm around him as all of you went inside.

♡♡♡

You took your place near the back of the church with Carl and Rick. Once everyone was settled and done singing, the service began and Father Gabriel stood on top of the podium. A few minutes into his sermon, the interruption of a motorcycle revving loudly outside sliced through the air. Gabriel flinched in surprise, and it was obvious he was desperately trying to keep his cool. Finally, when it was silent again, you found yourself biting back a smile knowing all too well who had caused the ruckus.

It seems Rick knew, too, judging from how his jaw clenched and his hands turned into tight fists.

The doors were thrown open, making Gabriel flinch once more and some of the congregation turning in the pews to look. But poor Gabriel quickly fumbled with his Bible, raising his voice just a tad to regain their attention.

There was a low whistle accompanying the approaching footsteps, but the congregation did their damn hardest to ignore the latest visitor.

"Damn... I assumed the church would be a lot more welcoming than this." A husky voice whispered, and you at last couldn't hold back as a smile broke through.

"Negan." You whispered back, turning slightly in your seat to see he has taken the spot behind you. His leather clad arms lackadaisically resting on your chair, the musky scent of his cologne invading your senses oh so wonderfully. "Fancy seeing you here."

"What? Is it really that surprising, darlin'?" He grinned, presenting a row of perfectly straight white teeth. "I go to church."

"Not all the time." You pointed out.

"Ah..." He chuckled softly, hazel eyes twinkling. "That's 'cause Father Creepy McGee over there is just that. Creepy. As. Shit."

You bit the inside of your cheeks, suppressing your laughter. True, Gabriel did have his moments, but he wasn't that bad. That didn't change the fact that Negan knew exactly how to tickle your funny bone, though.

He was new to Alexandria. It was a lovely town, but since it was relatively small not a lot of people want to move here not unless it was families looking for their children to grow up in a safe environment. Which was why it was quite a shock to find out that a single man like Negan chose this destination, and even more so when he took everyone aback with his infamous pottymouth and rather inappropriate charisma.

He had moved just a couple of houses down from yours, and you made it your mission to befriend him. Right from the get-go, he had piqued your interest and curiousity. He was different from everyone else--even possessing an air of mystery about him--and that definitely intrigued you. And also, perhaps you were just too nice and didn't want him to feel outcasted. Although, that didn't seem like an issue to him at all.

"Want one?" You were brought back to reality when you saw Negan's hand outstretched with a pack of cigarettes.

"Dude, we're in church." You reprimanded, frowning.

Negan didn't say anything, only cocking a brow and still with that same shit-eating grin. You sighed, finally giving in as you swiftly grabbed one and stashed it away in your purse for later.

"Y/N." You turned to the left, Rick's icy gaze piercing you. "Pay attention."

"R-Right. Sorry..." You mumbled sheepishly.

Carl, who was sitting in the middle of you and Rick, had dozed off. Rick nudged him, but the brunette only groaned softly and snuggled into Rick's chest. Defeated, the sheriff sighed and was just about to listen again to Gabriel before Negan cut in.

"Rick!" Negan purposely raised his voice, knowing it would get a rise out of the other man. "Didn't even see ya there. Howdy, cowboy!"

Rick grimaced, and it looked like he was just going to ignore Negan though he knew that if he did that then Negan would just irritate him even further. "Good to see you, Negan." He forced himself to say.

"Only you can say that while giving me such a deadly side eye, Grimes." Negan snickered. "How have you been? How's the wife?"

Rick flushed, his fists in a tight ball again and it looked like his nails would be digging into his skin. You abruptly swung into action, placing a hand on Rick's own.

"Rick..." You said gently. "It's okay. Calm down."

Rick did, his shoulders drooping as if a heavy weight had been lifted. He can barely pay any attention to Gabriel now, then you suddenly stood up and grabbed Negan's arm.

"We need to talk. Now."

"What, we going for a quickie?" Negan smirked, but that soon faded when he saw your serious expression. He sighed dramatically, reaching his full height as he towered over you before following you out.

At this point, you didn't care if people saw what transpired or would even start gossiping. No one, not even Negan, was allowed to harass Rick. He has helped you through so much shit--more than you'd like to admit--and you at least owed him this much.

Once outside, next to where Negan parked his motorcycle, you exploded. "What the fuck is with you?! You leave Rick alone, or I swear to fucking Christ I will--"

"Woah, woah, woah! Hold your horses, missy!" Negan guffawed, his hands up in mock surrender. "I mean, I like 'em feisty, but goddamn! Watch your fucking language."

"Tch. You're one to talk."

"Did you just scoff at me?" He raised his brows, putting his hands in his pockets as he slowly drew closer to you. A devilish grin tugged at the corners of his mouth, tilting his head slightly. "No one's ever fucking scoffed at me and didn't regret it soon after."

You frowned, letting out a huff as you met his gaze challengingly. "As if you'd do anything to me."

He was silent for several moments before chuckling, leaning back against his motorcycle. "You're right. I have too much of a soft spot for ya." He pulled out a cigarette, lighting it then taking a drag. He drew his head upwards, puffing out the smoke. "Whaddya say we just forgive and forget? I truly am sorry. You can even tell Rick that I am metaphorically down on my goddamn knees begging for forgiveness~"

"I'm not forgiving or forgetting anything until you actually face Rick and apologize yourself." You muttered. And without another word, you spun on your heel and strutted back inside the church with your head held high.

Negan's intent stare lingered where your ass had just been, taking another long drag and letting out a small laugh to himself.

His eyes suddenly glowed a crimson red, a smirk playing on his lips.

Oh, he really did pick a GREAT one.

#The Walking Dead#TWD#The Walking Dead AU#TWD AU#Alternate Universe#AU#Romance#Smut#Mature#Story Series#Reader#Female Reader#x Reader#Negan#Rick Grimes#Daryl Dixon#Jeffrey Dean Morgan#JDM#Andrew Lincoln#Norman Reedus#Incubus!Negan#Guardian Angel!Rick Grimes#Monster/Demon Hunter!Daryl Dixon#Negan x Reader#Rick Grimes x Reader#Daryl Dixon x Reader#Reader x Negan#Reader x Rick Grimes#Reader x Daryl Dixon

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding Obesity (Part 2): Whose responsibility for obesity?

Now that we know obesity is a public health crisis requiring urgent action, we may wonder - what causes it? After all, effective solutions require tackling the root causes of the problem. This part therefore aims to shed light on five of the many contributing factors to obesity.

1. Choices

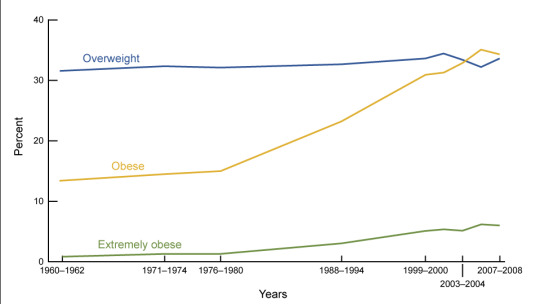

Nothing much to elaborate here; choosing to eat more and moving less will result in weight gain. More calories in, less calories out - basic law of thermodynamics. Boring. However, many people are quick to go down the reductionist route by placing ALL the blame on the individual’s personal choices. If it’s just a matter of people needing to make the right choices, if it’s really that simple, we would have tackled obesity long ago. Blaming obesity solely on individual choices does not answer WHY we are increasingly eating more and moving less. Take a look at this timeline of adult obesity in the U.S below by the CDC, similarly reported in other countries across the globe.

The rate of obesity has tripled worldwide since the late 1970s. If obesity is simply caused by a lack of personal responsibility, what happened in the late 1970s? Did everyone collectively lose their rationale - maybe everyone got together, decided to YOLO and go buffet in life? Definitely possible (cue the entrance of conspiracy theorists), but highly unlikely. Did some form of transcendent power strike the DNA of humans collectively that made us evolve into a bunch of lazier and much more ravenous creatures? Scientists have studied evolutionary changes during this period and concluded that nope, our gene pool has remained constant; any changes in the gene pool would take hundreds of years to produce an obvious effect across a global population anyway. This means that:

the global rise in obesity is not because of any significant genetic changes,

people did not willingly choose to eat more and move less,

there are other external factors that mainly drives the obesity epidemic.

Consider a class of 10 pupils. When only one pupil gets very low grades in an exam and the other nine got full marks, the one pupil is considered mainly at fault. Perhaps they need to study more and work harder to get a good mark. But when six out of ten got very low grades, is it still the pupils’ fault? Would we then tell the children to study more, while everyone else (i.e the teacher, parents, education system) just remain in inertia, or goyang kaki?

Similarly, when 63% of the people in Brunei are living with overweight and obesity -- is it still entirely their fault?

2. Environment

(Please bear with me, I’m trying my best not to turn this section into a whole thesis).

The environment is one of the largest contributors of the rise in the obesity epidemic. This is based on rigorous academic evidence and decades of research. Essentially, the environment has generally promoted the increased consumption of unhealthier food through a rapid increase in its:

availability : since the 1970s, the food environment underwent a shift from predominantly fresh produce to a more ultra processed diet. Food are being processed to the point where they look nothing like what they originally look like, stuffing them with cheap ingredients such as sugar, salt, trans-fats and flavourings to enable mass production to be sold at cheap prices and for easy consumption. These products are called ultra processed food, and examples include soda, sausages, nuggets, sugary cereals, instant noodles, crisps, chocolates and so on. Because of its poor nutritional profile, ultra processed food has confidently been associated with higher risks of obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer, depression, asthma, etc. And we, especially young people, are consuming more of this than ever.

exposure : we're talking about the aggressive marketing strategies that has been employed especially by the fast food industry and beyond. I remember going back home from the airport after my 14-day COVID quarantine being bombarded by roughly 10 billboard ads, majority of which are advertising for fast food. As I went out and about for the next few months, I realised that we are exposed to food companies constantly fighting for our attention through their advertisements, whether in the form of billboard ads, physical outlets, leaflets, newspaper ads, TV ads, social media ads, social media influencers, event sponsorships, - the list just goes on! In fact, 46% of the annual advertising budget in the UK goes to soda, confectionery and snacks, while only 2.5% goes to fruits and vegetables. Imagine if it was the other way around.. One can only dream... The point is, we as humans are constantly being tempted with unhealthier food rather than healthier food, which in turn, drives up our purchase and consumption of unhealthier food products. I also particularly like this photo taken in the UK that just showcases the pedestal unhealthier food ads are being placed on, i.e. same level as public health ads. Oh, the irony! (Good news for Bruneians - a code of conduct on responsible food marketing has been implemented recently to shield our children from these ads! Just what we need, priority on children’s health > anything else.)

portion sizes : certain food such as pizza and soft drinks underwent a significant increase in portion sizes from the 1970s to 2000s. Just a few days ago I went to to a fast food outlet and noticed that, as usual, the default drink choice is soda, but the default size is now the large one as compared to the smaller one that I remember seeing 3 years ago before I left the country. I was also informed that some other outlets have been asking customers to upsize their drinks by default. Just how necessary is this? We may think this is not a problem because people supposedly eat according to their physiological needs and can simply stop when they’re full, and so they wouldn’t need to finish the whole portion. But research leading to the discovery of what is known as the portion size effect (PSE) has suggested otherwise; the more energy-dense food people are served, the more they tend to eat.

The 21st century environment is also promoting physical inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle compared to the past centuries. Opportunities for physical activity especially in high-income countries have declined possibly due to the rapid urbanisation, rise in 9-5 jobs and more people relying on motorised transportation methods. Although research has shown that physical activity (PA) among adults done during free time have increased in the past ~30 years, a simultaneous decrease was found in physical activity done while working in the past ~50 years. Young people are also observed to be more physical inactive levels throughout the years, though locally... I like to think that our younger people are getting more physical-activity-conscious nowadays since applaudable efforts to widen opportunities for PA such as the launch of Bandarku Ceria and the opening of numerous hiking sites and gyms booming in 2019-2020. But this could just be my skewed perception looking at a small and specific demographic of the population - more formal research needs to be done.

So, we know that the environment is the main factor that drives up the obesity pandemic. But if we are all living in an environment which predisposes us to develop obesity, why don't we ALL have obesity? This tells us that there are other factors that makes an individual more likely to act on the environment's impulses - such as their socioeconomic status (income, education) and especially their genes.

3. Income

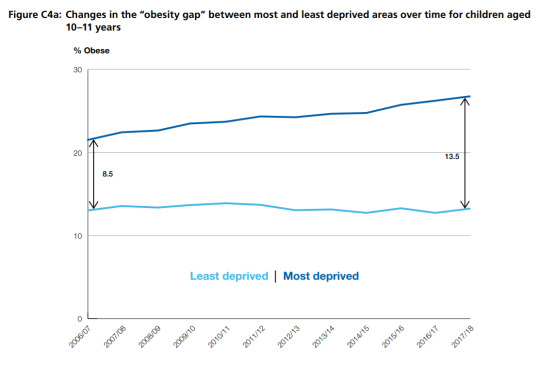

Research among developed countries such as the UK, Australia, Germany and Singapore has shown that people who are from lower income level are significantly associated with a higher risk of obesity. This graph below just shows how stark the inequality is between the most and least deprived areas of the UK. Note also how rapidly-widening the gap is over the years!

Why are poorer families in developed countries more likely to live with obesity?

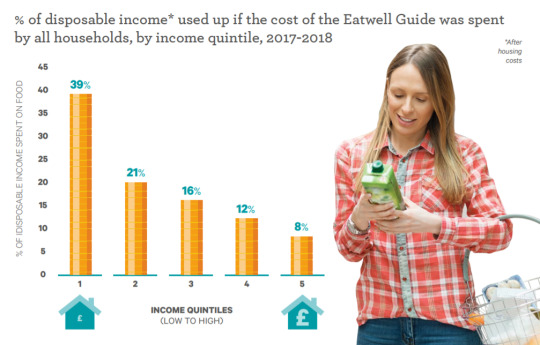

Food that are more nutritious are often less affordable than nutritious food. I particularly love this infographic showing how in order to meet the general recommendation of a healthy diet in the UK, the poorer families would have to spend 39% of their income on food alone, while this percentage steadily decreases as your income increases, to as low as 8% for the richer families. The same pattern is reflected in many other countries including the USA, Australia and

This inequality is not just seen within countries, but also across countries. One study across 18 countries identified that in order to meet the recommended guideline of 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day, families in lower income countries would need to spend 52% of their income on them, those in middle income countries would need to spend 17% while those in higher income countries would need to spend a mere 2% of their income.

The price gap between healthier and unhealthier food can then affect people's purchasing behaviour, where families from lower income are forced to prioritise quantity of food over quality. For some of us, we are privileged enough to be able to choose food that are delicious, nutritious, and of different variety each time. But for some others, especially among families with poorer background battling food insecurity, they can only afford to eat in order to feel full and get through the day. Research has shown how poorer families always have to 1) balance out their choices of food with the utilisation of scarce resources, and 2) make judgment of food prices relative to other food prices. Combining this with the known fact discussed above that unhealthier food are FAR more aggressively marketed (almost 20 times more) than healthier food - we are left with a group of the population who are predisposed to choosing food that are mainly satiating, and less nutritious than the recommended guideline.

In fact, we know that even more factors than those discussed above can contribute to people from poorer families having an unhealthier diet. One of them is, on top of the price gap of groceries, we have the price gap of fast food. Parents who are busy and don't have much time to cook nutritious and homemade food often resort to fast food to sustain their family. Sure, we have a plethora of fast food options to choose from (and they just keep increasing - don't get me started). But what kind of fast food is both affordable and nutritious? Nasi katok costs $1 while a balanced meal costs $5 (minimum), and this disparity is seen all around the world.

Given all this, we still have the audacity to say that obesity is simply caused by a lack of willpower?

Gimme a break. It is clear that people who are not as financially privileged requires additional support in order to maintain a healthy weight. If not through finance, through education (further explained in Cause 4), or even better - both!

Side note: Despite the overwhelming evidence that having low income is associated with higher risk of obesity, there is also emerging evidence showing the possibility of the opposite (reverse causality); living with obesity is ALSO associated with having low income due to stigmatisation and discrimination. So basically... living with low income may cause people to live with obesity, and likewise living with obesity may cause people to live with low income. This syndemic is similar to the that of obesity and mental health issues discussed in Part 1.

4. Education

Health is not formally taught in most schools. Health starts at home. Because of this varying education level and awareness about health across the population, each family has very different approaches of ensuring how their family can grow up adopting healthy behaviours.

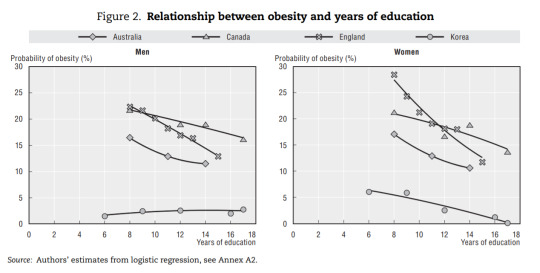

Generally, the likelihood of having obesity increases with decreasing level of education. This was observed in many countries including Taiwan, Saudi Arabia and Iran. The trend is similarly reported in OECD countries such as Australia, Canada, England and Korea as shown below.

This may be because more educated families tend to have healthier lifestyles and are more aware of what the causes and consequences are of obesity. If a family is lacking awareness and knowledge on certain aspects of health, such as in nutrition - eg: what the importance of consuming enough fibre is, what exactly constitutes a balanced diet, how to cook nutritious meals under time constraint etc - then their family will be less likely to adopt healthy (protective) behaviours.

Awareness on the causes and consequences of obesity indeed remain low within many communities. In one study, 76% of young people surveyed believe that "obesity has a genetic cause and that there is nothing much one can do to prevent obesity". Almost 30% of them also believe that even when substantial changes were made to one's lifestyle, obesity cannot be prevented. In the UK, around 3 in 4 people didn't know that obesity can cause cancer - the leading cause of death worldwide.

Not only are people unaware of the causes and consequences of obesity, many people even show a general lack of understanding of obesity itself. It was found that among 401 Malaysians surveyed, 92% of those with obesity underperceive their weight, thinking that their weight is at a normal range or lower than it actually is. This is particularly concerning, because any intervention efforts to reduce obesity rate within a community will just bounce back by the majority of the target group who think the messages are 'not for them because they don't have obesity' when they actually do.

All in all, if you come from an educated family background - good for you. If you have the opportunity to study more about health, or human/medical sciences - good for you. But what about those who do not have all these privileges?

Side note: There is also evidence showing how having lower education level is not just associated with higher level of obesity in a direct manner, but also indirectly where having a low education level may contribute to households having a lower income, and as discussed above in No.3 -> may result in a stacked effect on obesity. This is called the mediation effect and more explanation can be found here (pg 133).

5. Genetics

Over 200 genes influence our body shape and size. This include genes that affects how frequently we feel hungry, the rate that we burn calories, our metabolism rate, and many more! Some of these individual genes can increase our likelihood of becoming heavier while some other genes tend to make us lighter depending on whether it is 'switched on or off'. And this mix of 'on and offs' for EACH gene is always going to be different between individuals (polymorphism).

Because of our own 'mixed bag' of ~200 obesity-related genes interacting with each other, some people will find it much harder to resist that bar of Kinder Bueno sitting on the cashier till, while some others wouldn't even bat an eye. Some people naturally feels full after a bowl of rice, while some others would need three bowls. Some people can store a large amount of fats while some others can store only half of that amount before those fats (lipids) seep into other tissues instead such as muscles and potentially cause diseases (lipotoxicity).

Our genetic differences within the population explains why some people respond differently to the obesogenic environment we live in. It is not as simple as our genes determining whether we develop obesity or not. We simply can't be saying "Oh it's in my genes, got it from my parents~" to justify our lack of effort to address obesity. There's no single gene that makes people develop obesity. But rather, our mixed bag of genes determine our susceptibility to obesity. For people with many of those genes that makes it likely for them to gain weight easily 'switched on' -> they will be more susceptible to obesity because their own biology makes it much harder for them to fight back the temptations of the obesogenic environment.

Because this concept is so difficult to be understood by people who have always had a healthy weight all their life, privileged with not having the genes raising the likelihood of obesity 'switched on' -> they tend to blame obesity solely on the individual's personal choice. Because their own biology makes it easier for them to resist the temptations of the obesogenic environment.

As Joslin - an American doctor - described almost a century ago which pretty much summarises the role of genetics in obesity:

Genetics probably loads the gun, while lifestyle in our obesogenic environment pulls the trigger for the spreading of the obesity epidemic.

Does this mean that people who have genes that makes it more susceptible to develop obesity can simply blame their genes for their weight?

No! Not entirely. They can and should apply the same general concept of weight loss to counteract the risk of obesity, i.e. - eating balanced meals, doing plenty of physical activity (going back to the boring law of thermodynamics: more calories out than in = weight loss). However, it will be especially harder for these people to achieve it due to their obesity-encouraging genes. They have to put in more effort to lose 1kg than someone with less of the obesity-encouraging genes.

What this means for those with obesity: Your own genes and biology is one of the factors why your BMI is considered high at the moment and why it feels so difficult to lose weight. It is important for you to understand this, so that you don't beat yourself up too often! It is not entirely your fault. It will be hard, and in fact it will be harder than many people, but what matters is for you stay focused in putting in the work to get there!

What this means for those with healthy weight: It's about time for you to stop blaming everything on the individual's personal choice when you don't even know how difficult they have it and how much they have been trying to fight their own biology. Don't act like you know their struggles just to shame and stigmatise them because you don't and neither do I. Leave it to their close family and personal doctor to consult them.

What this means for policymakers: We have a duty in making sure that 1) the environment is as conducive as possible to live a healthy lifestyle to avoid 'triggering the gun', and 2) people are aware that genes play a big factor too (of around 40-70%) in determining someone's weight and its not just entirely down to the individual.

Side note: The genetic explanation above which acknowledges the role of hundreds of different genes in the development of obesity is applicable to the majority of people living with obesity (polygenic obesity). However, there are also the minority of people who develop obesity due to mutation in single genes (monogenic obesity / syndromic obesity) which warrants a separate and more technical explanation.

Bottom Line

To summarise the cause of obesity:

As mentioned in Cause 1, how we develop obesity is always down to the individual eating more and moving less. But as explained in Cause 2, 3, 4 & 5, the complex interaction between the environment, the individual's socioeconomic conditions, and their own biology explains why it is so difficult for some people to eat less and move more.

To summarise the cause of the obesity pandemic:

Personal choice explains why one individual may develop obesity, but the environment explains why more people across the whole world is developing obesity. Our socioeconomic conditions and especially our genetics then explains why not ALL people develop obesity as a response to the change in environment.

So what should I do with all these information?

That's entirely up to you and how much you understood! But the reason why I brought this topic up is because I'm personally sick and tired of hearing people living with obesity being blamed for their "poor choices in life", "lack of self-control", for "being gluttonous", "lazy", etc.

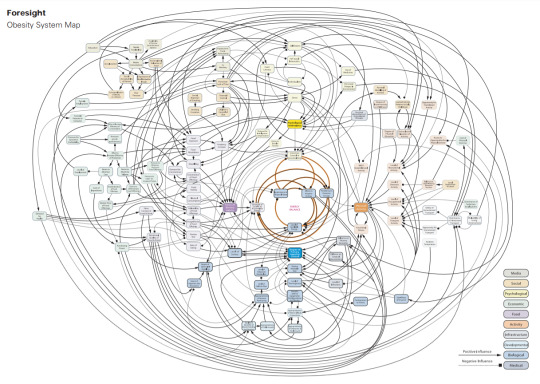

As I have hopefully explained, obesity is undoubtedly very complex and a result of so many factors. These five things I mentioned above? There's. So. Much. More.

Click here for a clearer view.

So the next time we blame it all on people with obesity - check your privileges. You're rich? You're naturally slim? You're educated? You don't have as much obesity-encouraging genes? Good for you. Perhaps that tends to make you feel entitled to say that people who are living with obesity just needs to make "better choices".

But understand that you have it easier in maintaining your healthy weight, while people with obesity most likely have it harder. The least you could do is really be sympathetic and understanding, acknowledge their struggles, and certainly avoid shaming and stigmatising them. Make it easier for them by providing healthier choices and support them physically and emotionally in their goals of achieving a healthy weight!

Aren't you just giving an excuse for people to live with obesity?

Disclaimer: My BMI sits quite well on the healthy range at 23 kg/m^2. I am nowhere close to having obesity, nor do I have any family members, partners or close friends living with obesity. I literally gain NOTHING to be making up an excuse for people to live with obesity. Quite on the contrary, I understand its dire consequences as I have outlined in Part 1, and I have even mentioned personal choice as one of the causes above. It's not about giving excuses, but simply an effort to give voice and justice to those who has been silenced.

I hope I have gotten my point across through this post and the previous one in my Obesity Series! Let's all be more-informed members of the society and support each other in achieving our health goals :)

*Note: For simplicity purposes, ‘unhealthier food’ in this post refers generally to food lower in nutritional profile, and food high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS). In reality, we should understand that food does not exist in a binary manner.

Unlinked References:

Gene Eating by Giles Yeo (Book)

CMO Independent Report: Time to Solve Childhood Obesity by Professor Dame Sally Davies

#obesity#brunei#child obesity#childhood obesity#causes of obesity#obesogenic environment#health#healthy lifestyle

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voices in AI – Episode 7: A Conversation with Jared Ficklin

Today's leading minds talk AI with host Byron Reese

.voice-in-ai-byline-embed { font-size: 1.4rem; background: url(https://voicesinai.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/cropped-voices-background.jpg) black; background-position: center; background-size: cover; color: white; padding: 1rem 1.5rem; font-weight: 200; text-transform: uppercase; margin-bottom: 1.5rem; } .voice-in-ai-byline-embed span { color: #FF6B00; }

In this episode, Byron and Jared talk about rights for machines, empathy, ethics, singularity, designing AI experiences, transparency, and a return to the Victorian era.

-

-

0:00

0:00

0:00

var go_alex_briefing = { expanded: true, get_vars: {}, twitter_player: false, auto_play: false }; (function( $ ) { 'use strict'; go_alex_briefing.init = function() { this.build_get_vars(); if ( 'undefined' != typeof go_alex_briefing.get_vars['action'] ) { this.twitter_player = 'true'; } if ( 'undefined' != typeof go_alex_briefing.get_vars['auto_play'] ) { this.auto_play = go_alex_briefing.get_vars['auto_play']; } if ( 'true' == this.twitter_player ) { $( '#top-header' ).remove(); } var $amplitude_args = { 'songs': [{"name":"Episode 7: A Conversation with Jared Ficklin","artist":"Byron Reese","album":"Voices in AI","url":"https:\/\/voicesinai.s3.amazonaws.com\/2017-09-28-(01-04-09)-jared-ficklin.mp3","live":false,"cover_art_url":"https:\/\/voicesinai.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2017\/09\/voices-headshot-card-6.jpg"}], 'default_album_art': 'https://gigaom.com/wp-content/plugins/go-alexa-briefing/components/external/amplify/images/no-cover-large.png' }; if ( 'true' == this.auto_play ) { $amplitude_args.autoplay = true; } Amplitude.init( $amplitude_args ); this.watch_controls(); }; go_alex_briefing.watch_controls = function() { $( '#small-player' ).hover( function() { $( '#small-player-middle-controls' ).show(); $( '#small-player-middle-meta' ).hide(); }, function() { $( '#small-player-middle-controls' ).hide(); $( '#small-player-middle-meta' ).show(); }); $( '#top-header' ).hover(function(){ $( '#top-header' ).show(); $( '#small-player' ).show(); }, function(){ }); $( '#small-player-toggle' ).click(function(){ $( '.hidden-on-collapse' ).show(); $( '.hidden-on-expanded' ).hide(); /* Is expanded */ go_alex_briefing.expanded = true; }); $('#top-header-toggle').click(function(){ $( '.hidden-on-collapse' ).hide(); $( '.hidden-on-expanded' ).show(); /* Is collapsed */ go_alex_briefing.expanded = false; }); // We're hacking it a bit so it works the way we want $( '#small-player-toggle' ).click(); $( '#top-header-toggle' ).hide(); }; go_alex_briefing.build_get_vars = function() { if( document.location.toString().indexOf( '?' ) !== -1 ) { var query = document.location .toString() // get the query string .replace(/^.*?\?/, '') // and remove any existing hash string (thanks, @vrijdenker) .replace(/#.*$/, '') .split('&'); for( var i=0, l=query.length; i<l; i++ ) { var aux = decodeURIComponent( query[i] ).split( '=' ); this.get_vars[ aux[0] ] = aux[1]; } } }; $( function() { go_alex_briefing.init(); }); })( jQuery ); .go-alexa-briefing-player { margin-bottom: 3rem; margin-right: 0; float: none; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-header { width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; min-height: 50px; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-large-album { width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; height: auto; margin-right: auto; margin-left: auto; z-index: 0; margin-top: 50px; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#top-large-album img#large-album-art { width: 100%; height: auto; border-radius: 0; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player { margin-top: 38px; width: 100%; max-width: 1000px; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player div#small-player-full-bottom-info { width: 90%; text-align: center; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player div#small-player-full-bottom-info div#song-time-visualization-large { width: 75%; } .go-alexa-briefing-player div#small-player-full-bottom { background-color: #f2f2f2; border-bottom-left-radius: 5px; border-bottom-right-radius: 5px; height: 57px; }

Voices in AI

Visit VoicesInAI.com to access the podcast, or subscribe now:

RSS

.voice-in-ai-link-back-embed { font-size: 1.4rem; background: url(https://voicesinai.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/cropped-voices-background.jpg) black; background-position: center; background-size: cover; color: white; padding: 1rem 1.5rem; font-weight: 200; text-transform: uppercase; margin-bottom: 1.5rem; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed:last-of-type { margin-bottom: 0; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo { margin-top: .25rem; display: block; background: url(https://voicesinai.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/voices-in-ai-logo-light-768x264.png) center left no-repeat; background-size: contain; width: 100%; padding-bottom: 30%; text-indent: -9999rem; margin-bottom: 1.5rem } @media (min-width: 960px) { .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed .logo { width: 262px; height: 90px; float: left; margin-right: 1.5rem; margin-bottom: 0; padding-bottom: 0; } } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:link, .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed a:visited { color: #FF6B00; } .voice-in-ai-link-back a:hover { color: #ff4f00; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links { margin-left: 0 !important; margin-right: 0 !important; margin-bottom: 0.25rem; } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:link, .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:visited { background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.77); } .voice-in-ai-link-back-embed ul.go-alexa-briefing-subscribe-links a:hover { background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.63); }

Byron Reese: This is Voices in AI, brought to you by Gigaom. I’m Byron Reese. Today, our guest is Jared Ficklin. He is a partner and Lead Creative Technologist at argodesign.

In addition, he has a wide range of other interests. He gave a well-received mainstage talk at TED about how to visualize music with fire. He co-created a mass transit system called The Wire. He co-designed and created a skatepark. For a long while, he designed the highly-interactive, famous South by Southwest (SXSW) opening parties which hosted thousands and thousands of people each year.

Welcome to the show, Jared.

Jared Ficklin: Thank you for having me.

I’ve got to start off with my basic, my first and favorite question: What is artificial intelligence?

Well, I think of it in the very mechanical way of, that it is a machine intelligence that has reached a point of sentience. But I think it is just a broad umbrella where we kind of apply it to any case where the computerization is attempting to solve problems with human-like thoughts or strategies.

Well, let’s split that into two halves, because there was an aspirational half of sentience, and then there was a practical half. Let’s start with the practical half. When it tries to solve problems that a person can solve, would you include a sprinkler that comes on when your lawn is dry as being an artificial intelligence? Because I don’t have to keep track of when my lawn is dry; the sprinkler system does.

First of all, this is my favorite half. I like this half of the procedural side more than the sentience side, although it’s fun to think about.

But, when you think of this sprinkler that you just talked about, there’s a couple of ways to arrive at this. One, it can be very procedural and not intelligent at all. I can have a sensor. The sensor can throw off voltage when it sees soil is of a certain dryness. That can connect on an electrical circuit which throws off a solenoid, and water begins spraying everywhere.

Now, you have the magic, and a person who doesn’t know that’s going on might look at that and say, “Holy cow! It’s intelligent! It has watered the lawn.” But it’s not. That is not machine intelligence and that is not AI. It’s just a simple procedural game.

There would be another way of doing that, and that’s to use a whole bunch of computations to study, and bring in a lot of factors of the weather coming in, the same sensor telling what soil dryness is… Run it through a whole lot of algorithms and make a decision based on the probability and the threshold of whether to turn on that sprinkler or not, and that would be a form of machine learning.

Now, if you look at the two, they seem the same on the face but they’re very different—not just in how they happen, but in the outcome. One of them is going to turn on the sprinkler, even though there are seven inches of rain coming tomorrow, and the other is not going to turn on the sprinkler because it’s aware that seven inches of rain are coming tomorrow. That little added extra judgment, or intelligence as we call it, is the key difference. That’s what makes all the difference in this, multiplied by a million times. To me.

Just to be clear, you specifically invoked machine learning. Are you saying there is no AI without machine learning?

No, I’m not saying that. That was just the strategy that applied in this situation.

Is the difference between those two extremes, in your mind, evolutionary? It’s not a black-and-white difference?

Yeah, there’s going to be scales and gradients. There’s also different strategies and algorithms that breed this outcome. One had a certain presumption of foresight, and a certain algorithmic processing. In some ways, it’s much smarter than a person.

There’s a great analogy. Matthew Santone, who is a co-worker here, is the first one who introduced me to the analogy. And I don’t know who came up with it, but it’s the ten thousand squirrels analogy around artificial intelligence in its state today.

On the face of it, you would think humans are much smarter than squirrels, and in many ways we are, but a squirrel has this particular capability of hiding ten thousand nuts in a field and being able to find them the next spring. When it comes to hiding nuts, a squirrel is much more intelligent than we are.

That’s another one of the key attributes of this procedural side of artificial intelligence, I think. It’s that these algorithms and intelligence become so focused on one specific task that they actually become much more capable and greater at it than humans.

Where do you think we are? Needless to say, the enthusiasm around AI is at a fevered pitch. What do you think brought that about, and do you think it’s warranted?

Well, it’s science fiction, I think, that has brought it about—everything from The Matrix in film, to books by John Varley or even Isaac Asimov—have given us a fascination about machines and artificial intelligence and what they can produce.

Then, right now, the business world is just talking all about it, because, I think, we’re at the level of the ten thousand squirrels. They can see a lot of value of putting those squirrels together to monitor something—you know, find those nuts in a way better than a human can. When you combine the two, it’s just on everyone’s lips and everywhere.

It doesn’t hurt that some of the bigwigs of thinkers of our time are out there talking about how dangerous it could possibly be, and that captures everyone’s attention as well.

What do you think of that? Why do you think that there are people who think we’re going to have an artificial general intelligence in a few years—five years is the earliest—and it’s something we should be concerned about? And then, there are people who say it’s not going to come for hundreds of years, and it’s not something we should be worried about. What is different in how they’re viewing the world?