#operator's polemic

Text

the distinction between board games and TTRPGs only exists in your heart baby

17K notes

·

View notes

Note

Why are communists against postmodernism?

in very crude terms: 'postmodernism' has historically been defined / defined itself by the rejection of claims to access 'objective' truths, narratives, and knowledge. in its strongest form, this stance precludes the defence of a materialist (including marxist) theory of history or society: if we cannot truly access an objective reality or know for sure that we are doing so, then clearly any discourse referring to 'real' material conditions or relations is rendered untenable, or at least heavily asterisked. in other words, a strict 'postmodernist' sees marxism as defending only a naïve realist position, à la feuerbach. the strict marxist, in turn, considers the postmodernist position to be a reactionary discourse that invokes the social construction of knowledge in order to defend (knowingly or not) ruling class interests by denying the possibility of understanding and therefore changing the material conditions of the world.

in practice, few people beyond a select few polemical academics have ever committed to the 'strong' versions of these claims. in particular, to read marxism as naïve in this manner is fundamentally a misunderstanding of marx's appropriation of hegel, which entailed not just 'turning him on his head' (that is, reversing the relationship between material world and ideal Spirit) but theorising dialectically. marx's claim was not that material reality could be known naïvely, or independently of our ideological schemata or modes of thought; nor was it that materiality (base) operated independently of, or solely in determination of, ideality (superstructure). and, though you may still hear some communists / marxists shitting on postmodernism, that term is mostly unfashionable these days anyway, and any serious communist analysis is itself predicated on quite a bit of social constructivist critique.

so although it's certainly true that communists are (rightfully) scornful of reactionary bourgeois postmodernist ideology that denies the basic premises of material / class analysis, in truth any decent communist these days is already making fruitful use of constructivist and post-structuralist critiques, and is also hostile to crude positivist / determinist ideology even when it brands itself as marxism. which is just to say that like a lot of philosophical debates, this one looks very different when we consider the substance of the arguments imputed to each 'side', and are attentive to when and how those arguments are actually deployed, rather than accepting at face value the sort of ideological coherence and consistency that is often implied by labels like "postmodernist" or debate parameters like "communist v. postmodernist".

437 notes

·

View notes

Text

The plain fact is that whatever Homer or Aeschylus might have had to say about the Persians or Asia, it simply is not a reflection of a ‘West’ or of ‘Europe’ as a civilizational entity, in a recognizably modern sense, and no modern discourse can be traced back to that origin, because the civilizational map and geographical imagination of Antiquity were fundamentally different from those that came to be fabricated in post-Renaissance Europe.

[...] It is also simply the case that the kind of essentializing procedure which Said associates exclusively with ‘the West’ is by no means a trait of the European alone; any number of Muslims routinely draw epistemological and ontological distinctions between East and West, the Islamicate and Christendom, and when Ayatollah Khomeini did it he hardly did so from an Orientalist position. And of course, it is common practice among many circles in India to posit Hindu spirituality against Western materialism, not to speak of Muslim barbarity. Nor is it possible to read the Mahabharata or the dharmshastras without being struck by the severity with which the dasyus and the shudras and the women are constantly being made into the dangerous, inferiorized Others. This is no mere polemical matter, either. What I am suggesting is that there have historically been all sorts of processes – connected with class and gender, ethnicity and religion, xenophobia and bigotry – which have unfortunately been at work in all human societies, both European and non-European. What gave European forms of these prejudices their special force in history, with devastating consequences for the actual lives of countless millions and expressed ideologically in full-blown Eurocentric racisms, was not some transhistorical process of ontological obsession and falsity – some gathering of unique force in domains of discourse – but, quite specifically, the power of colonial capitalism, which then gave rise to other sorts of powers. Within the realm of discourse over the past two hundred years, though, the relationship between the Brahminical and the Islamic high textualities, the Orientalist knowledges of these textualities, and their modern reproductions in Western as well as non-Western countries have produced such a wilderness of mirrors that we need the most incisive of operations, the most delicate of dialectics, to disaggregate these densities.

Aijaz Ahmed, In Theory: Nations, Literatures, Classes

632 notes

·

View notes

Text

take me back (take me with you) | f. megumi x fem! reader | chapter 8: late

ao3 link for additional author’s notes | playlist | prev | m.list

chapter synopsis:

' “Kugisaki Nobara. Be honoured, boys,” she says, stance confident, “I’m your group’s girl.”

She’s so cool. '

---

You meet the girl of steel, though you've yet to get closer to her. Luckily, you have friends around the corner like Yuuji— and Megumi, too, but it's a little different with him.

word count: ~7k; tws: none for now :)!!

short a/n: hi i’m sorry i was away for so long!! life got a little busy and this chapter took a while to write. I will preface it by saying that this one is quite boring, though, but the chapters to look forward to a bit more are the two next ones!! lots will happen there :). thank you for your patience and i’m so sorry again!

25-6-2018

By the time you’re back in Jujutsu High’s campus, night time has already shed its shadow against the world, black over Tokyo's fulgid skyscrapers like a veil, the sky devoid of any stars. Tokyo is a metropolis of glittery, coruscant lights that litter the land, with parks and crepe shops and cafes galore. And oh, how you love it every time you come back, from its 90s movie mood to its futuristic innovations.

Dr Ieiri really had planned everything, as if she’d always expected you to be here: she’d got you a room near her office, even helped to clean some of it up, and promised you that you’d still be merely a room away from the one other female student currently in the school. Once the last first year— a girl— arrived, she’d be staying right next to you.

“So? How long do you think you’ll be staying?” Dr Ieiri asks, “I know you’re planning on just giving someone something, but you’re going to be here for much longer, right?”

“Yeah.”

“Alright, but I’ll give you a heads up first. Staying here and operating as an actual sorcerer here, or a doctor for sorcerers like me or your father— it’s a far cry from the last time you were there. I won’t force you to help me when I need it, but you’re still going to be demanded of at almost all times, and I know you’d be the type of person to try to save people as much as you can. You have to be ready for that— the strain and all.”

So she knew what you wanted better than you did. “I am.” You’ll ask that of your father later, to tell Sugisawa Third that you’re transferring to a religious school in Tokyo. They knew too little of you to think of whether you were religious or not anyway.

“I’ll help you so you can still take things easy, okay?”

“...okay. Thank you, doctor.”

26-6-2018

Dr Ieiri smokes less than you thought. Really, the night that you first met her was the first time she’d smoked again in five years, according to her. She attributed it to nostalgia and reminiscing on old memories before asking you to just go to bed— it was almost two in the morning. But you thought it made sense that the ones who were made to heal were the ones who mourned what was unhealed the most; you weren’t the only one stuck playing long-gone memories like a panoramic film on loop, a permanent backdrop in your mind.

“You need to get a good night’s rest,” she’d said, but now you’re walking down the desolate hallways again. It’s fine— if there’s one thing about actually going against your parents for the first time instead of solely refuting them verbally in heated, mangled arguments, it’s that it’s insanely liberating. Before this, you’d have never even considered it an option, yet now it suddenly exists— that autonomy; suddenly, there isn’t a need to follow whatever order you’ve been given. And yes, you do respect Dr Ieiri and probably everyone else in your life, but you can choose not to abide by what they tell you just because you don’t want to— you decide it. No justifications, no reasons or polemics. Just pure responsibility and autonomy of yourself. You can’t fathom now, why you’d been scared of it before, or whether you’d even realised you were. It still feels unfamiliar, like a thrill, like adrenaline from treading on a tightrope above pits of deep, all-encompassing water, but in a week or so you’re going to have become used to it.

From your room, if you walked all the way to the end of the hallway, you’d see the first year boys’ dorms. You don’t take the letter with you— that’s a bridge to either burn or cross another time, when you’re not right about to sleep.

Careful to make as little sound as possible, you knock the door, hoping he’s awake.

You hear his groggy steps as he seems to trudge himself along, before the door opens with a creaky whine. “—it’s one in the morning,” he frowns, “What do you want—”

“Hi, Megumi.”

He closes the door. You wait outside for a moment.

Megumi opens the door again.

“...I should’ve told you I was here, actually,” you say.

“It’s one in the morning,” he goes, “Why aren’t…” he blinks his eyes awake a little, groaning as he rubs his temples, “Why aren’t you asleep? —no, why are you even here, really…”

You’re going to regret your replies come morning, probably; they’ll sound stupid by then. Maybe it’s the sleep deprivation, but that doesn’t really bother you. “I’m sorry. It’s just, um, I actually wanted to give you something, I mean— I’ll give it to you tomorrow or one of these days, but I was just bored. I just got here, and I’m just going to help Dr Ieiri with some things, um. …sorry, did I wake you? You should rest, actually, it helps your injuries heal faster; sorry for waking you—”

“—no, not… not really. Don’t worry about that,” he states, “But you should still go to sleep anyway. It’s late.”

“I can’t sleep.”

He opens the door and heads inside. An invitation for you to enter, it seems, because he turns and waits for you, the door ajar as you hesitate in front of it.

You come in.

His dorm room seems quite similar to the one in his old home, actually, the only difference being how his room now is only just a little larger than the one you were in at fourteen. (You wonder what happened to it, whether Tsumiki still lies on her bed with her phone for a maximum of five minutes at the same time every day.) The two of you sit on the foot of the bed, the lack of light unquestioned. Just like things were two years ago. With the lights outside his window, the bustling city still abuzz with their izakayas and night clubs, your eyes can trace over an outline of his sharp face and spiky hair.

“How long will you be staying?”

“Quite a while, I think.”

“...which is?”

“Probably more than a week.”

“Wh— then what about school?”

“Oh, I kind of, um… threw it away. I don’t know, um. My parents knew I’d be here for a long time. I think I’m just going to transfer here. I’ll leave it all behind that way.”

He sighs, “I know, but that… that just sounds like a thoughtless decision.”

“The only part of it that I put thought into was whether I’d run away and live or stay and rot there. So when Dr Ieiri gave me a chance I just took it. And I’ll keep taking what she gives me. If not, then… I’ll be stuck dwelling on it for the rest of my life, I think.” For so long, you’d been trying not to do so; to not take that life-determining chance, to decide to dwell yearningly instead of live, and to appease your parents so at least your mother would have that sliver of assurance, but not anymore. They wouldn’t be in your life forever.

“So you’re doing this just so you won’t live a life of regret? You’re doing this just for yourself?”

“It’s the same thing as doing this so that I can help people. It’s two sides of the same coin. Not everyone has what I do.”

“You sound like Itadori,” he says. The way he does so makes your chest ache slightly and you don’t know why. But nobody is as selfless or as much of an unstoppable force as Yuuji is. Nobody, ever. You turn your eyes away from him even if he can’t see you do so in the dark.

“But Yuuji takes that to the extreme, I’m…pretty sure. I’m just trying to do what I can because I can.”

You move your right hand to the side, fiddling with yourself, empty hands trying to find something to do. It bumps into something— something warm and soft. Skin.

With imaginary chills running along your body, you feel Megumi’s left pinky finger loop itself around yours. He clears his throat, breaking the silence, and you look at him again, at the vague shadow before you. “—that’s…that’s my hand.”

“Oh. Ah, okay,” you say. It feels right this way— comfortable, nervous, jumbled, calm—

Your hands move slowly, your fingers trying to steady it like steering around an old, shaky wooden boat with only a paddle, set and ready to embark on a journey. Quivering, you pull your right pinky finger away before your hand is fully enveloped under the hold of his. The heat from his palm on the back of your hand transfers itself right to your face and neck. It’s summer, but it feels cold and hot in the best way possible. “Do… do you want me to let go? Do you want me to stop?”

“...no. I don’t think so. Do you?”

“No. I want to stay.”

“Okay. Me too.”

He does.

In the silence you sit up, biting your bottom lip, your nerves like jelly and your brain probably fried if not for the lack of sleep. For a moment you decide to look at him, and you see him swifty turn his head away from you as soon as you do so.

(—so he’d been looking at you?)

What wakes you up is the sunrise, an early morning. It’s been embedded into your brain to wake up at seven sharp no matter how late you slept.

He’s sleeping, his face down, water in his eyelashes— you suppose that’s why he has such crystalline eyes, viridian ones that remind you of summer and life and protection. Jade and grass. Shifting into rather uncomfortable positions so as to not wake him, you pull yourself away.

His hand still remains snug over yours.

‘Just friends’ don’t do things like this, you think. But at the same time, ‘just friends’ don’t fight curses or heal those who do so, and ‘just friends’ don’t have a third person they had better relationships with before they broke apart while constantly thinking of each other and decided to at the very least become active figures in each others’ lives again.

This is scary, moving all too quickly. You’re being grabbed by the waist and thrust into a paraglider; you’re flying in the vast expanse of a boundless, unnavigable sky, manning a paramotor with no previous warning or idea of how to do so.

But he's very beautiful like this. Hair so black it’s blue, eyelashes woven of silk, a jaw so sharp yet so smooth. The sun greeting the sky as it ejects itself from the inky-hued horizon. You don’t know if there’s a creator, or if there’s a god— you’ve heard of Christianity and many other kinds of faith, though you’d never really dabbled in any of them. But you’d definitely thank someone like that, because scenes like these are proof that someone like that exists, and that that someone is an artist, a masterful artist. So he must have created you and given you an apt appreciation for beauty and art, too, as well as someone like Megumi who was beauty and art.

‘Just friends’ don’t think like that.

But you still will anyway. You can allow yourself that.

He makes a tired little noise as he wakes up, taking in a deep inhale. “...did we really—”

“Yeah. Um. —wait! I should, um, probably brush my teeth first, my breath probably smells horrible right now, sorry—”

“Oh. No, it’s fine, I should too—”

“Yeah, I think I’ll go back to my room too; I don’t want doctor suspecting anything, ah—”

“Oh— okay,” he releases his hand.

It’s strange to have things like these— little snippets and moments that remind you to just have fun and be a kid. For years— maybe your whole adolescent experience so far— every day hailed with it a new matter to tend to and worry about, and every day you subconsciously wondered if you were wasting your life away, doing nothing but fantasise of a faraway fancy in which you could use the only potential you had for something.

But who knew that it was so simple, yet so profound: that the excitement and memories that you yearned for could be obtained just from wanting to do so? That if you wanted to do something, you could just up and do it?

You like it, though. The paralysing, dizzying feeling of it all, breaths caught in your throat and you can’t say anything without stuttering. The last time you’d felt it, it was Yuuji: you’d had yourself emotionally constipated to the point you choked it all up within you, toned things down and muted the intensity of it all before you even felt it. But it was fun then, and now this is much better. It would seem delusional to hope for anything else. There’s not much of a fantasy for you to look to and put yourself into a deluge of daydreams about, but for once you want to feel something without the implications. That must be what being a teenager is like— you’d seen it time and time again in movies, with cliques and girlfriends and gossip sessions, but you’d never had the luxury to have them yourself and be a girl like that. So this must be what it’s like, at least a semblance of it, with its fun and frivolities and feelings straight from familiar flicks.

Not quite the time to put a name to it just yet, but it’s fun. At least, you can do it a little longer. It feels like a breath of fresh air after chaining yourself down like an anchor to the seabed.

You rush to the door. “I’ll see you later? For breakfast,” you try to smile as calmly as you can while you turn back to look at him again.

Thank goodness Dr Ieiri wakes up at eight whenever there isn't much work for her to tend to.

You set a mission for yourself: hold Megumi’s hand again at least once in your high school career.

Now that’s how to live without regrets, be a teenager, and have fun.

Are you being delusional?

You don’t know what Fushiguro Megumi is to you now, because ‘friend’ doesn’t sum it up well enough, ‘stranger’ doesn’t do the two of you your deserved justice, classmates isn’t the actual term, and ‘boyfriend’ is way too far from the truth.

So to have dreams like that; thoughts like that, you think as you brush your teeth, you’re probably making a fool of yourself again.

There’s something going on here and you don’t know what it is. And even if you’d told yourself you were fine with it, you don’t know how long everything else will be.

It makes you feel like an idiot.

But in your head you're filled with thoughts and, for a lack of a better term, hindrances. Did he sleep well? Do friends do that? Or was it just the two of you who’d do that? Was there even any meaning behind it all, any implications on your relationship due to this? This way you’d drive yourself insane before you could even get to breakfast.

Did he like it, though? Could he have liked it, the sight of you sleeping next to him? Of vulnerability? No, he couldn’t, right? Yet, if he did, then—

You needed to calm down.

(What about the letter?)

Maybe this was adrenaline: you’d run and take a few bites of breakfast before anyone else did, heading back to your room after you had done so. This way, nobody would see you. (You weren’t calm enough to do this, what made you think, in your sleep-deprived mind, that you’d be mature enough to handle this the next morning?)

Just as you’re planning strategies to spend the whole day holed up in your room and avoid contact with anyone for it all, there’s a knock on your door.

“Took so much to talk to the dad alone—” he says, his voice muffled as he speaks to someone else, “I could never stand that old geezer! If he’s like that I’m glad I never had to know how much worse his wife is.”

It’s Gojo, you can tell. There’s a slight mocking tone in the way he does everything, in the way he says and laughs about the most out-of-pocket shit ever— this is one of those times, because you can almost hear what you think is a feral maniac with the voice of an idol laughing like a loon as he bangs against your door as if he’s trying to kill it.

“You probably shouldn’t hit it so hard.” Dr Ieiri’s voice.

You open the door. “Yes?”

“He’s saying that you should come as backup, and I thought it would help you be put on the spot. It’ll teach you how to operate with clarity as you work,” Dr Ieiri explains.

“Besides, you won’t even need to help that much. It’s just that this way, you’ll be able to do so if it’s needed while we’re here to guide you. Think of a baby taking its first steps with the help of its parents. If it gets dangerous for them, I’ll step in and you can heal them, but if you can’t heal them enough, we’ll just bring them back to Shoko,” Gojo cheerfully adds. Dr Ieiri nods along with him.

“Ah… okay.” Your first “actual” lesson as an “apprentice”, then.

“But first, you should change,” Gojo tells you, handing you a set of clothes, “Here. It’s a spare standard uniform that we keep for special cases. Now you can match with Megumi!”

Your eyes widen, unsure of whether to laugh nervously or slap him or dash in the opposite direction— shawty a runner, she a track star.

“I’m so sorry that he’s like this,” Dr Ieiri goes. Joking or not, she’s right. You’re sorry she’s dealt with him for so long, too.

“...thanks.”

“Don’t bully my student, Satoru,” Dr Ieiri orders, and you kind of like the sound of your new title.

You wonder how Gojo got used to teleporting with his cursed technique, but you suppose that it comes with the innate ability to switch from one scene to another so rapidly without feeling at least a little sick— like how the shift from the quiet of the dormitories to the bustle outside of Harajuku has you feeling right now. The brightness of the summer sunlight feels like an intrusion as Gojo sets you down and you open your eyes again.

“Wow.”

“Oh, it’s [Name]!”

Megumi looks away. He’s probably embarrassed to hell and back right now— angry at you, even, maybe. You weren’t sure anymore; you couldn’t even think. You try to let the heat rising up to your face subside without fanning it, steadying yourself beside Gojo, swearing that you’d like to be invisible just this once.

“Sorry for the wait! I had to take up a call. I brought [Name] over here for backup too to get a grasp of the on-field experience.” Gojo says, waving at them, “Oh! Your uniform made it in time.”

“Yeah! It fits great! Though I noticed it’s slightly different from Fushiguro’s. Mine has got a hood.”

It does fit him, you think, as you look at Yuuji. It looks better on him than it did when he sent you pictures of it over text. It’s easier to look at him now than Megumi.

“That’s because the uniforms can be customised upon request.”

“Huh?” Yuuji tilts his head to the side, “But I never put in any requests.”

“You’re right!” Gojo smiles, “I was the one who put in the custom order.”

“Huh… oh. Well, cool!”

“Be careful,” Megumi goes, “Gojo has a habit of doing that kind of stuff. So why are we meeting up here in Harajuku?”

“Because,” Gojo clarifies, “That’s what she asked for.”

“Oh!” Yuuji starts as the four of you walk out of the station, “You’re wearing the uniform too, [Name]. Looking good!”

“Really? Thanks. I mean, I like the skirt. The uniform makes me feel like a fancy princess in a fancy school or something, but the skirt looks a little like it belongs to an elegant office lady.”

“Uh, yeah,” Megumi follows, “You… look good. In the uniform, I mean.”

You force out a laugh— “Haha, uh… you too. I mean, everyone would look good with these uniforms, right?” Wow…

“...I guess so,” Megumi replies, looking in the other direction.

If you see Gojo stifling his laughter in front of you, no you don’t.

“We- we should get popcorn. I read online that said you could get really tasty popcorn at one of the shops in Takeshita Street.”

“Yay, popcorn!” Yuuji exclaims, “I want some!”

“Sure,” Gojo chuckles, “The shop’s pretty near here anyway. This is your guys’ first time in Harajuku, right, [Name] and Yuuji?”

“Ah… yeah, and now that I think about it, Yuuji had never been out of Sendai until recently, actually. Right?”

“Yeah, but I thought you’d have been to Harajuku before.”

“I mean, I used to live in Tokyo, but I didn’t really move around. I think the most famous place I’ve been to is Shinjuku-Gyoen. Really pretty garden…”

“Oh… then we should go around Tokyo one of these days!”

“Yeah,” you smile, “We should! But you could spend a whole week exploring and you still wouldn’t see all of it,” you remark, “It’s a good idea, though.”

“Fushiguro, wanna come along?”

“Uh, sure…” Megumi goes, avoiding eye contact with you. You do the same.

“...hey, is everything okay between the two of you? How come you’re so shy with each other all of a sudden?”

“H-huh? Ah, no, no, it’s okay.”

“You said ‘no’ twice. You usually only repeat words like that when you’re really worried about something,” Yuuji says. Curse his affinity for knowing you.

“But it’s fine, though. Don’t worry.”

“Uh… yeah. What [Name] said.”

“You sure?” Yuuji asks again, a bit concerned. “Okay, then.”

The rest of the walk mostly goes in silence— Yuuji excitedly heads for things to buy, from funky accessories to buckets of snacks. By the time it’s over and all of you are near the 400 yen corner, he’s decked out in all the Tokyo tourist gear, there’s popcorn in his hands, and sunglasses with frames spelling out “ROOK” on his face. (Maybe because he’s a rookie?)

There’s a well-dressed girl in front of you— you wonder if it’s her, but she isn’t wearing the uniform, so it probably isn’t— and a man most likely bald and wearing a wig with his black-and-white business suit. “Well, hello, there!” the man says to her, “Are you on the clock right now?”

“No, not right now,” she replies.

“That’s great! You see, I’m looking for potential models. That’s what I do! Would you be interested?”

He’s scouting for models?

There’s a sliver of hope in you that he looks at you next and asks you that question. You’re sure it isn’t going to happen, but you suppose you would like being told you were pretty by having a job associated with people who were— there was no chance, though. In Tokyo, the vast metropolis that it is, there are so many with better looks; better faces, prettier hair, nicer bodies— or people who dress better, walk more confidently; people who are adequate in all the ways you aren’t.

The thought slightly shocks you, in reality— you haven’t thought about how you may not be able to compare with others since the time when you really did realise that Yuuji would never like you (not in that way, at least, and it still hurts to think about it). You never thought you’d feel that way again, and you never thought you would have to be surprised by such thoughts that had been brought in by something akin to envy or jealousy.

“I’m in a hurry right now,” the girl denies.

At least she probably knows just how beautiful she is.

“Hey, you!” another girl calls. This one is just as beautiful— prettier than you, with brown (probably dyed) hair, and pretty brown eyes to match. She’s wearing the same uniform as you save for some titivations at the skirt, and she looks way better in it than you do. “What about me?” she asks, pointing at herself, “For that modelling gig. Hey, I’m asking what you think about me.”

She’s so confident, it’s so cool…

“Oh, well uh… I’m in a hurry at the moment,” the man says. Little bitch boy.

“What the hell?” she asks, holding the man by the collar, “Don’t run, come out and say what you think!”

“Wait, she’s the one we have to go and talk to? This is real embarrassing,” Yuuji says.

Megumi mutters under his breath, “Yeah? So are you.”

“I think she’s an icon,” you express.

Gojo waves at her, amused, “Hey, we’re over here!”

The girl slams the locker door shut after she places her backpack— a really tiny, cute pink one— into its pit of shopping bags. Probably to buy pretty clothes. She’d look really good in them.

“Right, so now we have our three students! Oh— [Name] here isn’t really a student, by the way, I’ll explain later,” Gojo informs the pretty girl, “I’d like you to meet—”

“Kugisaki Nobara. Be honoured, boys,” she says, stance confident, “I’m your group’s girl.”

She’s so cool.

Oh, she’s judging them, you think as she stares at the boys.

“I’m Itadori Yuuji. I’m from Sendai!”

“Fushiguro Megumi.”

“Ugh,” she lets out, “This is what I get to work with? Great, just my luck.”

“She took one look and sighed— that can’t be good,” Yuuji says.

“Are we going somewhere from here?” Megumi asks.

“Well, we do have all three—”

“All four—” Megumi interjects.

“Ack— no, no, Megumi, I’m not a student, hold on—” You don’t want to be something other than a ghost, not right now, because then you’ll have to deal with whatever you’ve done in the last twenty-four hours that you’d rather beat around the bush and eventually forget about than anything.

“Okay, we do have all four of you together, and since three of you kids are from the countryside, that means…” he pauses for effect— were you really “from” the countryside, though, if you’d moved around so much that you had no sure idea where your roots were? “...we’re going to Tokyo!”

You and Megumi watch as Kugisaki and Yuuji chant the city name over and over in unison before arguing over where to head to. But this is Gojo— so there may be a catch somewhere that you just haven’t found yet.

Megumi looks as annoyed as ever, much like the expression his younger self used to have when his eyebrows crinkled in exasperation from your antics.

“If you quiet down, I’ll announce our destination,” Gojo begins, and the newly formed pair quiet down, “Roppongi!”

It’s probably just something like an abandoned building in Roppongi, not Roppongi in all of its glamour itself.

It’s an abandoned building in Roppongi.

Gojo explains the situation after Kugisaki and Yuuji’s outrage— “There’s a big cemetery nearby. That, plus an abandoned building, and you’ve got a curse.”

Kugisaki stops her raging when she finds out that Yuuji is still learning about how curses are formed. “Wait, hold up here. He didn’t even know that yet?”

“To be honest…” Megumi starts to explain.

She looks horrified after.

(If you could, though, if you were anything other than a ghost right now— you’d tell her of how selfless and brave Yuuji is, of how incredible he is that he stopped at nothing to help his friends. You’d tell her that this was what made liking him as easy as breathing air.)

Before the two of them head into the building, Gojo hands Yuuji a cursed tool— you’d never actually seen one before. You wonder if he’ll be able to wield it well enough: you know he has it covered, but you’re still worried about him anyway. (You always are.)

And he gives Yuuji a challenge, too, though it’s more like an ultimatum. “Don’t let Sukuna out, okay?”

Soon the three of you sit down near the building— there’s a block of concrete that you wonder why it was placed there for, and Gojo gestures for Megumi and you to sit down there.

“Hey, you should be sitting here. I’m fine with standing.”

“Nah, just take a seat. I’ve got to be on standby anyway.”

“But you’re the teacher. You should get a better seat. And I’m not injured like Megumi, so I’m fine with standing.”

“Pft,” he snorts, “You think I actually care about that sort of stuff?”

You pause. “I… guess not. Thank you. Sorry again.”

Gojo squats down instead, only his feet on the floor. “See? It’s better this way. Just you and Megumi in your own little world—”

“—please stop.”

Megumi turns away from you again in embarrassment.

“Anyway…ah, Kugisaki is really pretty,” you state, “And she seems really strong. I’m still worried, though. What if the curse inside is stronger than anticipated…”

“...I think I’ll go in too,” Megumi says, “Someone needs to keep an eye on Itadori, right?”

“You should rest and let your injuries heal, though. I mean, I could help you with that, but I’m supposed to wait for their injuries first—”

“Well, the one we’re testing this time is Nobara,” Gojo highlights, “That Yuuji… he’s got some screws loose: he’s fearless— these things take the form of terrifying creatures who try to kill him, yet the guy has no hesitation at all. And he doesn’t have the familiarity with curses that you have. We’re talking about a boy who used to live a normal high school life. By now you’ve seen plenty of sorcerers and you’ve seen them give up because they couldn’t conquer their fear or disgust, right?” he explains to Megumi.

He’s right, though. For someone who had no idea what curses were just a bit more than a week ago, it’s amazing how he can acclimatise himself to such a new life so quickly. When you’d first learned about curses and jujutsu sorcerers, the only reason your life stayed that way was because actually becoming a victim of it seemed like merely a faraway hypothetical, something that couldn’t affect you— up until your father revealed his cursed technique and you exorcised that curse in the store a while after. That was when the ghastly figure of reality that was jujutsu society reared its head and pricked you with its cold finger. As happy as you were after you’d exorcised it, you could feel that empty pit forming in your gut— you did it, thank goodness, but what now? And as your heart raced while you helped that lady, you didn’t address it.

You supposed the benefit of your position was not having to at all.

“Hasn’t Kugisaki already dealt with curses before, though?”

“As we know, curses are born from human minds, so their strength in numbers grows in proportion to the population,” Gojo teaches, “Do you think Nobara understands? Tokyo curses are of a different level than those in the countryside.”

The curse you handled before would be on the weaker side, then. “In what way?” you ask.

“Their cunning— monsters that have gained wisdom will force cruel choices upon you where the weight of human life hangs in the balance. [Name], when you fought that curse last time, did it seem to be sentient or self-aware?”

“...I mean, I guess it seemed like it couldn’t really see the other person there. It was just me and the lady who worked there, so… no.”

“Well, to put it into perspective, [Name], the curse, had it been one from the city instead, could have done something like take the lady hostage to sort of threaten you and keep itself at large. So this test is to see if Nobara is crazy enough.”

It wouldn’t matter, though— you were the healer, the medic, the doctor. Whatever level of martial prowess you were supposed to have didn’t concern you.

“And speaking of tests, [Name]…” Gojo begins, “One of these days, you’ll have to get one too. As someone about to take Shoko’s role, this is your first test as a medic— every mission you get sent to will be a test in that aspect. But as a sorcerer…”

“Hey. I’m not an actual sorcerer, though, remember? And you should speak with Dr Ieiri first if you want me to expel curses like one and all.”

“Well, I didn’t speak to Dr Ieiri. I spoke to your dear old dad!”

“What?”

“Took a lot of convincing, but—”

“He didn’t tell me anything about this. I’m sorry— I know you just treated me well and gave me a better seat, but why didn’t you think to ask me first? It’s not like I ever really wanted to fight, either. And they were on-board with that. It’s just— why would you change that?”

Megumi sighs exasperatedly, “Seriously, what is this?”

“Yeah! What is this, Gojo?”

“Okay, okay: I’ll share a secret with the two of you, then. You’ve always been tied together, so there’s no use in me telling either of you just to not tell the rest. Keep it between yourselves, okay? Think of it as another part of your shared bond,” Gojo says.

You purse your lip. (Your mother did that a lot. There is nothing you can do that your parents are not entwined in even now; the roots of them have been planted so deeply into your life, ingrained so deeply into your psyche.) “Look, I just want you to answer me, Gojo. Why did you do it?” Why ruin a consensus that took years of compromise and arguments to settle on?

“...because you can. I mean, it’s your philosophy to be like that, right? If you have the ability to help someone, do it.”

“I mean, in essence, yeah, but what kind of point are you trying to make here?”

“That I think with that mindset you’d make a pretty good teacher. You know,” he sighs with a faux furtiveness, “Your father had that same mindset, with his strength and his intelligence and his kindness, and he was one of the best teachers you could ever have. He wasn’t an actual teacher, but… he was the kind of geezer who people thought were wise and would seek guidance from. A great guy, actually. But to cut to the chase, what I’m saying is that I want you to be a sorcerer who knows how to fight, too, instead of just the doctor in the corner that you believe will be the peak of your potential. I think you can do better.”

“So? I mean, as bad as it sounds, I don’t want to.”

“That’s why I just want you to try. I want you to have that test and become an actual student here. Shoko doesn’t mind you not becoming one because she thinks they won’t send you on missions if you’re considered ‘too valuable’ by the higher-ups. But I want you to become my student— I’ll give you time to think about it, but look at this way: you have abilities that exceed what you think of yourself— imagine how it sounded to other sorcerers when they heard of you back then, a thirteen-year-old with a late-blooming cursed technique grasping control of it instantly and defeating a grade two curse, even healing the person left behind. Face it: you’re technically a prodigy. The only thing that separates you from others like you is your humanity that troubles you with a reluctance to believe you can actually do anything.”

Harsh. “...I’ll think about it. But why spring it up on me now?”

“Maybe you know too little. O-kay, children, listen carefully. Little [Name]’s father would be a relatively famous sorcerer just because of his partial position as a healer, right? For all your life, you were sheltered and protected by your parents who never wanted you to enter into the jujutsu world. I even spoke to your mother herself, remember? Told her that you’d probably be a window but that you could still use cursed energy. You hadn’t shown signs of a cursed technique yet, but we hadn’t considered that it was because prior to that you never had to use it— the countryside areas you grew up in were practically devoid of any curses that your mother and father wouldn’t have already killed themselves. So, with your father’s quote-en-quote ‘fame’, what makes you think that people wouldn’t have wanted you as a jujutsu sorcerer from the start?”

Just like that the worlds in your head have had worlds of meanings added to them.

“So? What do you think, [Name]?”

You turn to Megumi. When you’re backed out into a corner, your eyes scrambling for a place to put them, you turn to Megumi.

His hand moves hesitantly to your shoulder, ghosting over it like a teapot over a china cup. “...whatever it is, you’ll do well. Gojo just likes to pull stuff like this.”

It feels warm. You won’t be in trouble if you don’t run away from this. It’s nice. It’s calm, his steady hand on your shoulder as your heart feels like it’s about to take a nosedive. “...thanks.”

“Give me some time, Gojo.”

Yuuji and Kugisaki come back with a little boy in tow.

“Ah— you’re back!”

“No injuries, [Name]! We’re all scratch-free! The kid has a bruise on his knee, though.”

“Oh. Can I see it, please?” you ask the boy, kneeling to his height.

The boy pulls the left hem of his pants up, revealing a fresh violet blot on his skin.

“Would you be okay if I touched your knee? I can take the bruise away for you.”

He nods and soon it’s gone, his skin pristine and new. “Woah,” he goes, “Thank you! Was that magic?” he asks, eyes full of childlike wonder.

You giggle. “Something like that. Could you keep it a secret?” you make the best welcoming and kid-friendly grin you can as you place your index against your lips.

“Okay!” he whisper-shouts, smiling wide.

Kugisaki and Yuuji rest by the building while Gojo, Megumi and you bring the kid back home.

“You know, I wanted to say, big sister,” he starts, looking up at you, “You’re really pretty!”

(So cute!!) “Ah, really? That other girl is really pretty too, though.”

“You too! You could be like a model on a poster!” he exclaims, “Oh wait— I live over there! Thanks again!” he points to the turning on the left.

“Haha, thank you,” you reply as Gojo waves at him, “Take care of yourself!”

“I will! Bye-bye, big sister!”

“Are you hungry?” you ask Gojo and Megumi. “Ack— I feel lightheaded.”

Megumi turns to you in an instant— “You didn’t eat enough for breakfast?”

“Guess so,” you reply, “I should be fine, though. I think I just had something on my mind the whole day and I couldn’t feel the hunger or something.”

He whips his phone out.

“Oh, there’s a famous tonkatsu restaurant back in Omotesando,” you suggest as he scrolls through restaurant options. “I think Yuuji may want to eat something like steak, though, and I don’t know what Kugisaki likes. Is there anything you want in particular?”

“I’m fine with anything,” he says, “But it’s Gojo’s money we’re going to be using, so we should probably make the most of it.”

“Mm… we can eat beef steak in Ginza, I think… ah— Yuuji’s grandfather always called it beefteki. I’m surprised I can still remember.”

27-6-2018

“Hi. It’s one in the morning, Megumi,” you greet him as he stands outside your room’s door, “Can’t sleep?”

“...yeah,” he admits sheepishly, “Sorry about this.”

He sits down on the bed. “Nah, it’s fine. It’s like we’re going to keep doing this,” you start, “Our special ritual. Something like that. I mean, we help each other in this way, right?”

Your hand strays upward a little, nervous as it inches toward his shoulder.

He brings your hand there and places his own hand on top of it. “Yeah,” he replies contentedly, “But I… wanted to ask,” Megumi begins, “What Gojo said. Are you going to become a student?”

“I don’t know. I mean, looking at how things are going now, I may. It seems like things are leaning more towards me being a full-fledged sorcerer. Haven’t had the time to think about it.”

He seems to pause for a moment, to reconsider something one last time like a record in his head.

“What’s wrong? Are you okay?”

“I should take you to see Tsumiki first.”

You nearly gasp. “She wants to see me?” After all this time? “I’m happy, but… wouldn’t she be busy, though?”

“No… I mean… you really should take a look at her first. Then you’ll see what I’m trying to say. I’m sorry, but I just— I really should have told you sooner.

“Told me what?” you frown. Learning of this feels a bit like restarting and going back to square one somehow.

“I’m sorry, can we just… do something else for now? Just… please be patient with me a little longer. I’m sorry you have to do that so much.”

“…okay.”

You wake up to his figure being illuminated shyly by the light of dawn. In the tiny bubble that the two of you share— of intertwined paths, secrets, lives— and the sensation of waking from a late night, you realise just how much you want to stay there forever.

This morning, you don’t rush back to your room and hastily go through your routine. All you do for a while, for what feels like it lasts for a century yet lasts for too little time, is look at him, at his steady, quiet breathing as his eyes are shut comfortably tight.

taglist:

@bakananya, @sindulgent666, @shartnart1, @lolmais, @mechalily, @pweewee, @notsaelty, @nattisbored

(please send an ask/state in the notes if you'd like to join! if I can't tag your username properly, I've written it in italics. so sorry for any trouble!)

#aaa so sorry for being gone for so long#got a little busy#finally!! done with this one!!#it's quite boring though#um... please look forward to chapter 9 and 10 it's less ass than this chapter lol#so sorry!!#jjk x reader#take me back (take me with you)#jjk megumi#jujutsu kaisen x reader#jujutsu kaisen#jjk#megumi fushiguro#megumi#fushiguro megumi#megumi fluff#megumi angst#fushiguro megumi x reader#megumi fushiguro x reader#jjk x fem!reader#fem!reader#ruer writes#megumi x reader#jjk x you#jjk x y/n#jujutsu kaisen x you#jujutsu kaisen x y/n#megumi imagine#fanfiction#jjk fanfiction

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fact that the feminization and moralization of envy have operated in collusion to suppress its potential as a means of recognizing and polemically responding to social inequalities, casting suspicion on the possible validity of such a response and converting it into a reflection of petty or 'diseased' selfhood, should alert us to the fact that forms of negative affect are more likely to be stripped of their critical implications when the impassioned subject is female. Envy's concomitant feminization and moral devaluation thus points to a larger cultural anxiety over antagonistic responses to inequality that are made specifically by women.

Ugly Feelings - Sianne Ngai (2005)

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

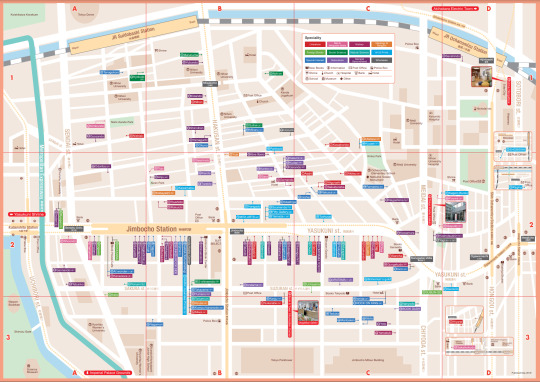

Another big stop in Tokyo for me was Jimbocho Book Town! It is a neighborhood of, depending on who you ask, up to 400 generally-secondhand bookstores flanked by some of the major universities in Tokyo. The local government even prints out maps of the stores to help people find them all:

Which, you will note, is not 400 stores, because the process of becoming an "official" Jimbocho Town Bookstore is an intensely political operation run by local stakeholders with tons of fights over what should qualify and what rights that entails - never change humanity!

"Book Towns" used to actually be quite a common thing, and they peaked during the literary boom of the late 19th century. Figuring out "what books existed" was a hard task, and to do serious research you needed to own the books (you weren't making photocopies), so concentrating specialty bookstores in one area made sense to allow someone to go to one place and ask around to find what they need and discover what exists. It was academia's version of Comiket! Modern digital information & distribution networks slowly killed or at least reduced these districts in places like Paris or London, but Jimbocho is one of the few that still survives.

Why it has is multi-causal for sure - half of this story is that Tokyo is YIMBY paradise and has constantly built new buildings to meet demand so rents have been kept down, allowing low-margin, individually-owned operations to continue where they have struggled in places like the US. These stores don't make much money but they don't have to. But as important is that Japan has a very strong 'book collector' culture, it's the original baseball cards for a lot of people. The "organic" demand for a 1960's shoujo magazine or porcelainware picture book is low, but hobbyists building collections is a whole new source of interest. Book-as-art-collection powered Jimbocho through until the 21st century, where - again like Comiket - the 'spectacle' could give it a lift and allow the area to become a tourist attraction and a mecca for the ~cozy book hoarder aesthetic~ to take over. Now it can exist on its vibes, which go so far as to be government-recognized: In 2001 the "scent wafting from the pages of the secondhand bookstore" was added to Japan's Ministry of Environment's List of 100 Fragrance Landscapes.

Of course this transition has changed what it sells; when it first began in the Meiji area, Jimbocho served the growing universities flanking it, and was a hotpot of academic (and political-polemic) texts. Those stores still exist, but as universities built libraries and then digital collections, the hobby world has taken over. Which comes back to me, baby! If you want Old Anime Books Jimbocho is one of the best places to go - the list of "subculture" stores is expansive.

I'll highlight two here: the first store I went to was Kudan Shobo, a 3rd floor walk-up specializing in shoujo manga. And my guys, the ~vibes~ of this store. It has this little sign outside pointing you up the stairs with the cutest book angel logo:

And the stairs:

Real flex of Japan's low crime status btw. Inside is jam-packed shelves and the owner just sitting there eating dinner, so I didn't take any photos inside, but not only did it have a great collection of fully-complete shoujo magazines going back to the 1970's, it had a ton of "meta" books on shoujo & anime, even a doujinshi collection focusing on 'commentary on the otaku scene' style publications. Every Jimbocho store just has their own unique collection, and you can only discover it by visiting. I picked up two books here (will showcase some of the buys in another post).

The other great ~subculture~ store I went to was Yumeno Shoten - and this is the store I would recommend to any otaku visiting, it was a much broader collection while still having a ton of niche stuff. The vibes continued to be immaculate of course:

And they covered every category you could imagine - Newtype-style news magazine, anime cels, artbooks, off-beat serial manga magazines, 1st edition prints, just everything. They had promotional posters from Mushi Pro-era productions like Cleopatra, nothing was out of reach. I got a ton of books here - it was one of the first stores I visited on my second day in Jimobocho, which made me *heavily* weighed down for the subsequent explorations, a rookie mistake for sure. There are adorable book-themed hotels and hostels in Jimbocho, and I absolutely could see a trip where you just shop here for a week and stay nearby so you can drop off your haul as you go.

We went to other great stores - I was on the lookout for some 90's era photography stuff, particularly by youth punk photographer Hiromix (#FLCL database), and I got very close at fashion/photography store Komiyama Shoten but never quite got what I was looking for. Shinsendo Shoten is a bookstore devoted entirely to the "railway and industrial history of Japan" and an extensive map collection, it was my kind of fetish art. My partner @darktypedreams found two old copies of the fashion magazine Gothic & Lolita Bible, uh, somewhere, we checked like five places and I don't remember which finally had it! And we also visited Aratama Shoten, a store collecting vintage pornography with a gigantic section on old BDSM works that was very much up her alley. It had the porn price premium so we didn't buy anything, but it was delightful to look through works on bondage and non-con from as far back as the 1960's, where honestly the line between "this is just for the fetish" and "this is authentic gender politics" was...sometimes very blurry. No photos of this one for very obvious reasons.

Jimbocho absolutely earned its rep, its an extremely stellar example of how history, culture, and uh land use policy can build something in one place that seems impossible in another operating under a different set of those forces. Definitely one of the highlights of the trip.

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the 80th Anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

In honor of this event, and Monday’s observance of Yom HaShoah, I’m posting a roundup of all of my writings, spanning 2011-Yesterday, on the topic of Jewish women, the Holocaust, the Warsaw Ghetto, and resistance.

A profile of Hannah Szenes, a Hungarian Jewish paratrooper who worked behind Nazi lines in services of the SOE (Special Operations Executive, same as Noor Inayat Khan).

Why Gender History is Important, Asshole. The post that started it all, that made me realize how many of you are passionately curious about the topic of women and the Holocaust, and how many of you share my righteous indignation over the fact that this knowledge is so uncommon.

We need to talk about Anne Frank: a thinkpiece about how we use and misuse the memory of Anne Frank. NOT a John Green hitpiece; if that’s your takeaway you’re reading it wrong.

An 11-part post series about Vladka Meed, a Jewish resistance worker who smuggled explosives into the Warsaw Ghetto in preparation for the Uprising, and set up covert aid networks in slave labor camps, among other things.

Girls with Guns, Woman Commanders, and Unheeded Warnings: Women and the Holocaust: an assessment of how Holocaust memory is shaped by male experiences, and an analysis of what we miss through this centering of the male experience.

Filip Muller’s testimony regarding young women’s defiant behavior in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. [comes with big trigger/content warning]

Tema Schneiderman and Tossia Altman: Voices from Beyond the Grave; paper presented at the Heroines of the Holocaust: New Frameworks of Resistance International Symposium at Wagner College.

A meditation/polemic on Jewish women, abortion, and the Holocaust, and the American Christian far-right’s misuse of Holocaust memory in anti-choice rhetoric. [comes with big trigger/content warning]

Women and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising; talk presented at the National World War II Museum’s 15th International Conference on World War II.

Women of the Warsaw Ghetto; keynote speech delivered at the Jewish Federation of Dutchess County’s Yom HaShoah Program in Honor of the 80th Anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

#warsaw ghetto uprising#jewish women#women and the holocaust#warsaw ghetto#jewish history#holocaust#holocaust history#women's history#gender history

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

26 Iyyar 5784 (2-3 June 2024)

Once again, we have a yahrzeit of two influential teachers centuries apart who shaped Judaism and demonstrate Jewish diversity and adaptability.

Saadia ben Yosef, Gaon of Sura, was born on the banks of the Nile in 4652, roughly 200 years after the Islamic conquest. Thus, rather than the Greco-Roman and Persian cultures of the Tannaim and Amoraim, he grew up in an Arabic speaking world shaped by a rival Abrahamic tradition. He was the first Jewish scholar to write primarily in Judeo-Arabic, the language later adopted by the Rambam Moshe ben Maimon. At the age of 20, Saadia began compiling a Hebrew dictionary. He soon went to eretz yisroel for further study, and after ten years there moved to Babylonia where he became a member of yeshiva of Sura, which had been in continuous operation from the time of the Amoraim. Within two years the Jewish exilarch appointed Saadia as Gaon of the academy.

From the start, Saadia’s career was shaped by disputation and sharp debate with those whose stances he found theologically or socially objectionable. The tenor of those disputes was shaped not only by Jewish tradition, but by the open conflict between Mutazilite and Mutakallamist scholars of Islam, who in Saadia’s time remained in dispute about whether the Quranuc text was a created object like other creations, or co-eternal with G-d and fundamental to the divine essence. Parallel debates about the Torah have raged in Judaism, but Saadia borrowed the shape of the qadi’s arguments rather than their content, engaging in sharp disputes about the proper way to calculate the Hebrew calendar and striving to defend rabbinic Judaism in fiery exchanges with Karaite scholars who accepted only the written Torah and rejected the oral traditions central to rabbinic practice. Saadia’s fiery temper and forceful personality soon put him at odds with his benefactor the Exilarch, and they spent several years in bitter conflict, each going so far as to issue cherem against the other. Their eventual reconciliation allowed Saadia to return to his position as head of the yeshiva of Sura, a position which carried great weight of authority for Jews throughout the Islamic world.

A prolific scholar, he composed numerous translations, publishing much of the Tanakh in Arabic translation, numerous linguistic texts on the Hebrew language, works of halakha, theology, and Jewish mysticism, and a large number of polemics against his various ideological opponents. He died in Sura in the year 4702 at the age of sixty, reportedly of severe depression from his many conflicts with the exilarch and others.

Moshe Chaim Luzzatto was born just over eight hundred years late than Saadia, in 5467, in the Venetian Ghetto (the first Jewish quarter to be called by that odious name). He received a wide Jewish and secular education, and may have attended the university of Padua. In his teens he began to compose poetry, including his own collection of 150 Hebrew psalms in full biblical style, and study Jewish mysticism. At the age of twenty he claimed he had been visited by a Malakh and began writing down mystical lessons from this heavenly mentor. This claim of divine tutelage shocked and offended the Venetian rabbinical establishment, and he was only saved by cherem by agreeing to cease his writing and teaching of mysticism. He then emigrated to Amsterdam where he continued his mystical explorations while working as a diamond cutter, thus following closely in the footsteps of a controversial Jew from a century before, Baruch Spinoza. Disappointed by the difficulties of life in Amsterdam, he traveled to eretz yisroel with his family three years before his death and established a shul in Acre. He died during a plague outbreak in Acre at the age of 39, leaving behind an immense body of poetry, drama, and theological, ethical, and mystical instruction despite the seizure and destruction of much of his early work by the Venetian Jewish authorities. His works were soon praised by the Vilna Gaon and became central to the Mussar movement, and his Hebrew poetry and blending of secular and Torah learning and literature became a major inspiration to the Haskalah. For his rabbinic teachings he is known by the acronym RaMCHaL, for Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto.

The twenty-sixth of Iyyar is also the sixth night of the sixth week of the Omer count. Yesterday was the fortieth day of the Omer. After tonight’s count, 8 days remain before Shavuot.

#jewish holidays#jewish calendar#hebrew calendar#jewish#judaism#jumblr#yahrzeit#Saadia Gaon#Moshe Chaim Luzzatto#RaMCHaL#omer#counting the omer#sefirat ha omer#iyyar#26 Iyyar#🌘

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

An incisive, wickedly funny debut novel about a graduate student who decides to follow her disgraced mentor to a university that gives safe harbor to scholars of ill repute, igniting a crisis of work and a test of her conscience (and marriage)

Helen is one of the best minds of her generation. A young physicist on a path to solve high-temperature superconductivity, which could save the planet, Helen is torn when she discovers her brilliant advisor is involved in a sex scandal. Should she give up on her work with him? Or should she accompany him to a controversial university, founded by a provocateur billionaire, that hosts academics that other schools have thrown out?

Helen decides she must go--her work is too important. She brings along her partner, Hew, who is much less sanguine about living on an island where the disgraced and deplorable get to operate with impunity. Soon enough, Helen finds herself drawn to an iconoclastic older novelist, while Hew stews in an increasingly radical protest movement. Their rift deepens until both confront choices that will reshape their lives--and maybe the world.

Irreverent, generous, anchored in character, and provocative without being polemical, How I Won a Nobel Prize illuminates the compromises we’ll make for progress, what it means to be a good person, and how to win a Nobel Prize. Turns out it’s not that hard--if you can run the numbers.

#book: how i won a nobel prize#author: julius taranto#genre: literary#genre: contemporary#genre: humor#year: 2020s

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

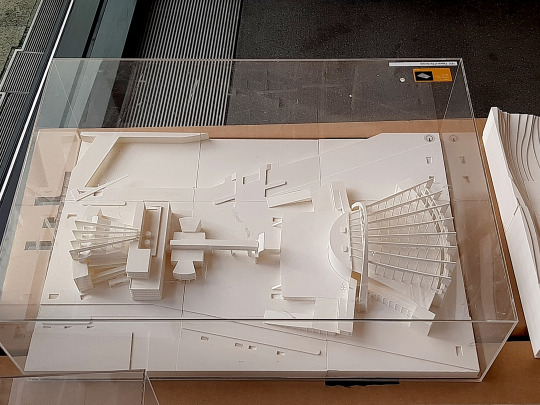

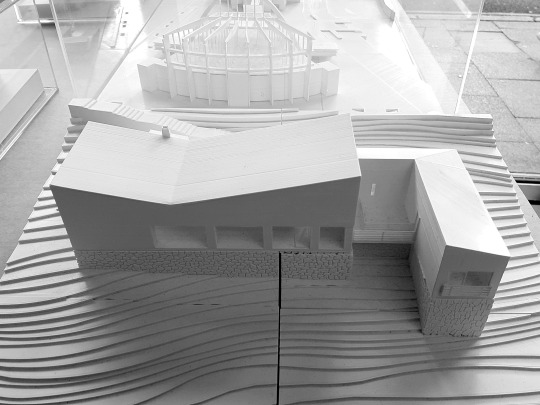

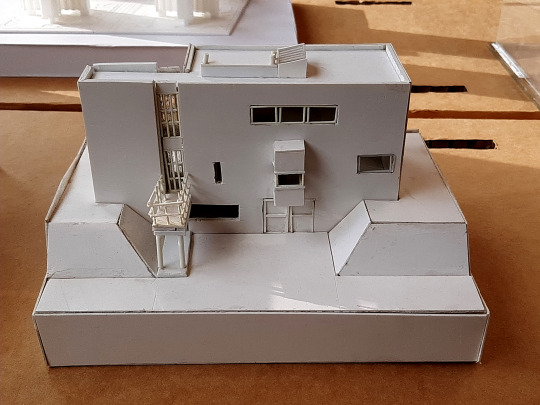

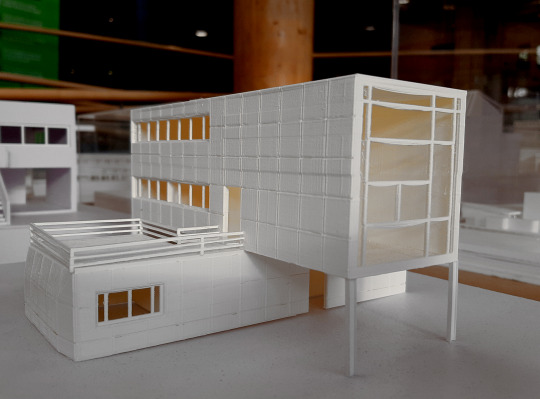

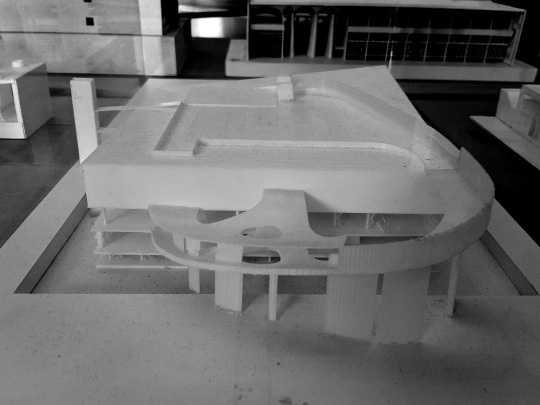

"Le Corbusier’s Models of Worldmaking"_ London South Bank University _ 21.03.2023 - 06.04.2023

The School of The Built Environment and Architecture at London South Bank University (#LSBU) hosts an international symposium, reconsidering an exhibition of 150+ models of Le Corbusier’s built and unbuilt projects.

The Symposium will take place in:

Lecture Theatre A, Keyworth Centre, London South Bank University (#LSBU), Keyworth Street, London SE1 6NG.

Thursday 30 March 2023, 17:30'-20:30'

Registration link:

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/le-corbusiers-models-of-worldmaking-tickets-592126023877

The exhibition of models is open to the public from 21 March to 06 April 2023 in the foyer of Keyworth Centre, #LSBU.

Since the early 20th century Le Corbusier’s projects have been unavoidable points of reference in architectural knowledge and practice. Their roles, however, have changed historically from avant-garde and polemic statements of icons of the modernist movement, to stigmatised and politically charged constructions, and, in recent years, to contested grounds for reflections on ethical, socially-aware, and ecologically-just practices. His projects, whether built or unbuilt, operate in the tension between architecture imagined and architecture conceived. This space in-between is precisely the quality that turns them into the driving force for progression and reconsideration of the field of architecture. Their discursive, imaginative, and projective qualities have produced socio-spatial imaginaries and expressible fantasies. The symposium celebrates an exhibition of 156 models of Le Corbusier’s built and unbuilt projects proposed for x countries. It brings together researchers, architects, and scholars to revisit Le Corbusier’s Models of Worldmaking examined through various architectural, pedagogical, and theoretical perspectives. The speakers outline a systematic form of enquiry reflecting on key experimental and methodological applications of Le Corbusier’s work, ones that could be catalysts of change or critical reflection on our radically changing profession.

Convened by:

Dr. Hamed Khosravi and Prof. Igea Troiani.

Guest Speakers:

Brigitte Bouvier (Director, Fondation Le Corbusier)

Prof. Alan Powers (London School of Architecture)

Prof. Tim Benton (Open University)

Rene Tan (Director, RT+Q)

Layton Reid (Visiting Prof. at University of West London).

The event is supported by grant funding provided by #LSBU.

#Le Corbusier’s Models of Worldmaking#London South Bank University#LSBU#Dr. Hamed Khosravi#Prof. Igea Troiani#Brigitte Bouvier#Prof. Alan Powers#Prof. Tim Benton#Rene Tan#Layton Reid#Spyros Kaprinis#2023#Le Corbusier

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

franchises that most need 5e licensed adaptations

south park

the bangles

100 years of solitude

arrested development

peter and the wolf

twitter.com/dril

the iliad

steamboat willie (this one's free game boys. kobold press are you listening this one's easy money)

caillou

jerma985

portugeuse (the language)

the grapes of wrath

dennis the menace (uk)

dennis the mance (us)

dark souls no wait they actually fucking did this one lol

the got milk? ads

pathfinder

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Coleman Hughes

Published: Oct 27, 2019

In 2016, Ibram X. Kendi became the youngest person ever to win the National Book Award for Nonfiction. His surprise bestseller, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas, cast him in his role as an activist-historian, ambitiously attempting to make 600 years of racial history digestible in 500 pages. In his follow-up, How to Be an Antiracist, Kendi––now 37, a Guggenheim fellow, and a contributing writer at The Atlantic––reveals his personal side, weaving together memoir, polemic, and instruction as he invites the reader to join him on the frontlines of what I like to call the War on Racism.

If the book has a core thesis, it is that this war admits of no neutral parties and no ceasefires. For Kendi, “there is no such thing as a not-racist idea,” only “racist ideas and antiracist ideas.” His Manichaean outlook extends to policy. “Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity,” Kendi proclaims, defining the former as racist policies and the latter as antiracist ones.

Every policy? That question was posed to Kendi by Vox cofounder Ezra Klein, who gave the hypothetical example of a capital-gains tax cut. Most of us think of the capital-gains tax, if we think about it at all, as a policy that is neutral as regards questions of race or racism. But given that blacks are underrepresented among stockowners, Klein asked, would it be racist to support a capital-gains tax cut? “Yes,” Kendi answered, without hesitation. And in case you planned on escaping the charge of racism by remaining agnostic on the capital-gains tax, that won’t work either, because Kendi defines a racist as anyone who supports “a racist policy through their actions or inaction.”

Hailed by the New York Times as “the most courageous book to date on the problem of race in the Western mind,” How to Be an Antiracist is certainly bold in its effort to redefine a concept that bedevils American society. On his unusually expansive definition, Kendi sees racism operating not just behind niche issues like the capital-gains tax but also behind problems of civilizational significance. “Racism,” he writes, “has spread to nearly every part of the body politic,” “heightening exploitation,” causing “arms races,” and “threatening the life of human society with nuclear war and climate change.” How, exactly, racism is behind the threat of nuclear holocaust is left to the reader’s imagination.

At times, it’s hard to know whether to interpret Kendi’s arguments as factual claims subject to empirical scrutiny or as diary entries to be accepted as personal truths. Indeed, much of the book reads like a seeker’s memoir or a conversion story in the mold of Augustine’s Confessions. Raised in a rough part of Queens in the 1990s, Kendi recounts his long journey from anti-black racism to anti-white racism, and eventually, to antiracism. In high school, Kendi delivered a speech bemoaning the bad behavior of black youth; by college, he had outgrown that phase and become anti-white, convinced at one point that white people were literal aliens but later scaling down to the belief that they were “simply a different breed of human.” A New Yorker piece cites a column he wrote as an undergraduate, in which he argued that “white people were fending off racial extinction, using ‘psychological brainwashing’ and ‘the aids virus.’”

Having matured out of his anti-white phase, Kendi takes a refreshingly strong stand against anti-white racism in the book, rejecting the fashionable argument that blacks cannot be racist because they lack power. He reflects with embarrassment on his old beliefs, avoiding condescension by lecturing his former self instead of the reader. Still, certain autobiographical details call for embarrassment but don’t get it. He recalls, for example, his first night living in Virginia as a teenager, during which he stayed up all night, “worried the Ku Klux Klan would arrive any minute.” That took place in 1997.

The book is weakest in its chapter devoted to capitalism. “Capitalism is essentially racist,” Kendi proclaims, and “racism is essentially capitalist.” To test this claim, a careful thinker might compare racism in capitalist countries with racism in socialist/Communist ones; or he might compare racism in the private sector with racism in the public sector. Kendi does neither. Instead, he presents the link between capitalism and racism as self-evidently true: “Since the dawn of racial capitalism, when were markets level playing fields? . . . . When could Black people compete equally with White people?” Kendi asks, implying that the answer is “never.”

I can think of several historical examples in which capitalism inspired anti-racism. The most famous is the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court case, when a profit-hungry railroad company––upset that legally mandated segregation meant adding costly train cars––teamed up with a civil rights group to challenge racial segregation. Nor was that case unique. Privately owned bus and trolley companies in the Jim Crow South “frequently resisted segregation” because “separate cars and sections” were “too expensive,” according to one scholarly paper on the subject.

A lesser known example is the South African housing market under Apartheid. Though landlords in whites-only areas were legally barred from renting to nonwhites, vacancies made discrimination against non-white tenants costly. As a result, white landlords often ignored the law. In his book South Africa’s War on Capitalism, economist Walter Williams notes that at least one “whites-only” district was in fact comprised of a majority of nonwhites.

History offers little evidence that capitalism is either inherently racist or antiracist. As a result, Kendi must resort to cherry-picking data to demonstrate a link. Citing a Pew article, he asserts that the “Black unemployment rate has been at least twice as high as the White unemployment rate for the last fifty years” because of the “conjoined twins” of racism and capitalism. But why limit the analysis to the past 50 years? A paper cited in the same Pew article reveals that the black-white unemployment gap was “small or nonexistent before 1940,” when America was arguably more capitalist—and certainly more racist.

Kendi also cherry-picks his data when discussing race and health. He laments that blacks are more likely than whites to have Alzheimer’s disease, but neglects to mention that whites are more likely to die from it, according to the latest mortality data from the Center for Disease Control. In the same vein, he correctly notes that blacks are more likely than whites to die of prostate cancer and breast cancer, but does not include the fact that blacks are less likely than whites to die of esophageal cancer, lung cancer, skin cancer, ovarian cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and leukemia. Of course, it should not be a competition over which race is more likely to die of which disease––but that’s precisely my point. By selectively citing data that show blacks suffering more than whites, Kendi turns what should be a unifying, race-neutral battle ground––namely, humanity’s fight against deadly diseases––into another proxy battle in the War on Racism.

Worse than the skewed approach to data in Kendi’s book are the factual errors. Citing an entire book by Manning Marable (but no specific page), Kendi claims that in 1982, “[President Reagan] cut the safety net of federal welfare programs and Medicaid, sending more low-income Blacks into poverty.” I could not find any data in Marable’s book showing that the black poverty rate rose during Reagan’s tenure. In fact, the opposite appears to be true, according to the Census Bureau’s historical poverty tables: the black poverty rate decreased for every age group between 1982 and the end of Reagan’s tenure in 1989.

Also erroneous is Kendi’s claim, for which he offers no citation, that “White women” are the “primary beneficiaries” of “affirmative-action programs.” Judging from a similar claim made in Vox, this myth seems to come from a paper published by the critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw in 2006. Crenshaw’s paper, troublingly, contains no data and no empirical analysis. However, a group of political scientists did conduct an empirical study on the relationship between white women and affirmative action in the same year. They found that employers who supported affirmative action were no more likely to employ white women than employers who didn’t. The primary beneficiaries of affirmative action—at least in university admissions—are, in fact, the black and Latino children of middle- and upper-middle-class families.

What Kendi lacks in empirical rigor he makes up for in candor. Whereas many antiracists dance awkwardly around the fact that affirmative action is a racially discriminatory policy, Kendi says what they probably believe but are too afraid to say: namely, that “racial discrimination is not inherently racist.” He continues:

The defining question is whether the discrimination is creating equity or inequity. If discrimination is creating equity, then it is antiracist. If discrimination is creating inequity, then it is racist. . . . The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.

Insofar as Kendi’s book speaks for modern antiracism, then it should be praised for clarifying what the “anti” really means. Fundamentally, the modern antiracist movement is not against discrimination. It is against inequity, which in many cases makes it pro-discrimination.

The problem with racial equity––defined as numerically equal outcomes between races––is that it’s unachievable. Without doubt, we have a long way to go in terms of maximizing opportunity for America’s most disadvantaged citizens. Many public schools are subpar, and some are atrocious; a sizable minority of black children grow up in neighborhoods replete with crime and abandoned buildings, while a majority grow up in single-parent homes. Too many blacks are behind bars.

All this is true, yet none of it implies that equal outcomes are possible. Kendi discusses inequity between ethnic groups––which he views as identical to inequity between racial groups—as problems created by racist policy. This view commits him to some bizarre conclusions. For example, according to 2017 Census Bureau data, the average Haitian-American earned 68 cents for every dollar earned by the average Nigerian-American. The average French-American earned 70 cents for every dollar earned by the average Russian-American. Similar examples abound. Is it more likely that our society imposes policies that discriminate against American descendants of Haiti and France, but not Nigeria and Russia—or that disparities between racial and ethnic groups are normal, even in the absence of racist policies? Kendi’s view puts him firmly in the former camp. “To be antiracist,” he claims, “is to view the inequities between all racialized ethnic groups”––by which he means groups like Haitian-Americans and Nigerian-Americans––“as a problem of policy.” Put bluntly, this assumption is indefensible.

What would it take to achieve a world of racial equity? Top-down enforcement of racial quotas? A constitutional amendment banning racial disparity? A Department of Antiracism to prescreen every policy for racially disparate impact? These ideas may sound like they were conjured up to caricature antiracists as Orwellian supervillains, but Kendi has actually suggested them as policy recommendations. His proposal is worth quoting in full:

To fix the original sin of racism, Americans should pass an anti-racist amendment to the U.S. Constitution that enshrines two guiding anti-racist principles: Racial inequity is evidence of racist policy and the different racial groups are equals. The amendment would make unconstitutional racial inequity over a certain threshold, as well as racist ideas by public officials (with “racist ideas” and “public official” clearly defined).

Kendi’s suggestion that “racist ideas” would or could be rigorously defined is cold comfort, given his capacious definition of racism. In his book, Kendi calls belief in an achievement gap between black and white students a “racist idea.” Does that mean that President Obama would have violated Kendi’s antiracist amendment when he talked about the achievement gap in 2016? Would we have to overturn the First Amendment to make way for the anti-racist amendment?

Kendi’s proposal continues:

[The anti-racist amendment] would establish and permanently fund the Department of Anti-racism (DOA) comprised of formally trained experts on racism and no political appointees. The DOA would be responsible for preclearing all local, state and federal public policies to ensure they won’t yield racial inequity, monitor those policies, investigate private racist policies when racial inequity surfaces, and monitor public officials for expressions of racist ideas. The DOA would be empowered with disciplinary tools to wield over and against policymakers and public officials who do not voluntarily change their racist policy and ideas.