#or like he has a message about the cycle of violence he wants to convey

Text

One of my favorite parts of phase 2 (and indeed one of the few moments I resonated with IDW Prowl) was when the neutrals were coming back to Cybertron and Prowl said that he refused to let Autobots be pushed aside and overruled after they were the ones who fought for freedom for 4 million years (the exact wording escapes me atm).

And I mean, that resentment still holds true even once the colonists come on bc like. As much as it's true that Cybertron's culture is fucked up, and as funny as it can be to paint Cybertronians as a bunch of weirdos who consider trying to kill someone as a common greeting not important enough to hold a grudge over.... The colonists POV kind of pissed me off a lot of times, as did the narrative tone/implications that Cybertronians are forever warlike and doomed to die by their own hands bc it just strikes me as an extremely judgemental and unsympathetic way to deal with a huge group of people with massive war PTSD and political/social tensions that were rampant even before the war?

Like, imagine living in a society rife with bigotry and discrimination where you get locked into certain occupations and social strata based on how you were born. The political tension is so bad there's a string of assassinations of politicians and leaders. The whole planet erupts into an outright war that leads (even unintentionally) to famine and chemical/biological warfare that destroys your planet. Both sides of the war are so entrenched in their pre-war sides and resentment for each other that this war lasts 4 million years and you don't even have a home planet any more. Then your home planet gets restored and a bunch of sheltered fucks come home and go "ewww why are you so violent?? You're a bunch of freaks just go live in the wilderness so that our home can belong to The Pure People Who Weren't Stupid And Evil Enough To Be Trapped In War" and then a bunch of colonists from places that know nothing about your history go "lol you people are so weird?? 🤣🤣 I don't get why y'all are fighting can't you just like, stop??? Oh okay you people are just fucked up and evil and stupid then" ((their planets are based on colonialism where their Primes wiped out the native populations btw whereas the Autobots and OP in particular fought to save organics. But that never gets brought up as a point in their favor)) as if the damage of a lifetime of war and a society that was broken even before the war can just magically go away now that the war is over.

Prowl fucking sucks but he was basically the only person that pointed out the injustice of that.

And then from then on out most of the characters from other colonies like Caminus and wherever else are going "i fucking hate you and your conflicts" w/ people like literal-nobody Slide and various Camiens getting to just sit there lecturing Optimus about how Cybertronians are too violent for their own good and how their conflicts are stupid, with only brief sympathetic moments where the Cybertronians get to be recognized as their own ppl who deserve sympathy before going right back to being lambasted.

Like I literally struggled to enjoy the story at multiple points because there was only so much I could take of the characters I knew and loved being raked over coals constantly while barely getting to defend themselves or be defended by the narrative so like. It was just fucking depressing and a little infuriating to read exRID/OP

#squiggposting#and like dont get me wrong barber wasnt trying to make cybertronians the bad guys or whatever#it's just a problem with his writing where like. he has A Message he wants to send#and so he uses the entire story literally just for The Message even if it involves bullshit plotlines#or familiar characters ppl were reading about for the past decade being shit on by OCs made up to fill a new roster#like barber's writing tends to lean way too much on a sort of lecturing tone#without giving proper care towards including moments where characters get to like. fucking express themselves and share their side#sort of like how barber couldnt be bothered to write pyra magna and optimus actually talking to each other during exrid#and instead during OP ongoing pyra is suddenly screaming about how OP is unteachable#even tho she never even tried to teach him bc she and OP never interacted bc i guess barber couldnt be bothered#he just needed someone to lecture OP so fuck making the story make sense or like letting OP get to say anything in defense#this is the infuriating part of barber's writing bc i think he has incredible IDEAS and was in charge of the lore i was most interested in#but most of the time his execution sucks and he's basically just mid with a few brilliant moments occasionally#or like he has a message about the cycle of violence he wants to convey#but his narrative choices trying to convey that theme made his story come off as super unsympathetic to the ppl who suffered#to the point where barber actively kneecapped some scenes that couldve been super fucking intense and emotional#in favor of the characters lecturing each other or some stupid plot to criticize OP#that time in unicron where windblade screamed about how this is their fault and then arcee replied that her planet is build on coloniation#shouldve happened more often than literally the last series of the ocntinuity. like goddamn stfu about your moral superiority#when your own sins are right fhere lol

213 notes

·

View notes

Note

I do not think that Ed is supposed to be abusive? i'm pretty sure we are meant to understand that he's acting this way because he's scared and threatened? The headbutting was rude but one isolated incident of headbutting in an extreme situation (waking up from a coma caused by a suicide attempt! his brain was all fucked up!) does not equal abuse. Where are you getting all this? Also I thought we were supposed to tag things with "[character] critical" around here.

Anon, I want you to understand that I say this as someone who has always loved Ed, and as someone who is approaching your message with the belief you are being completely genuine: Ed not being deliberately penned as abusive is almost the entire problem.

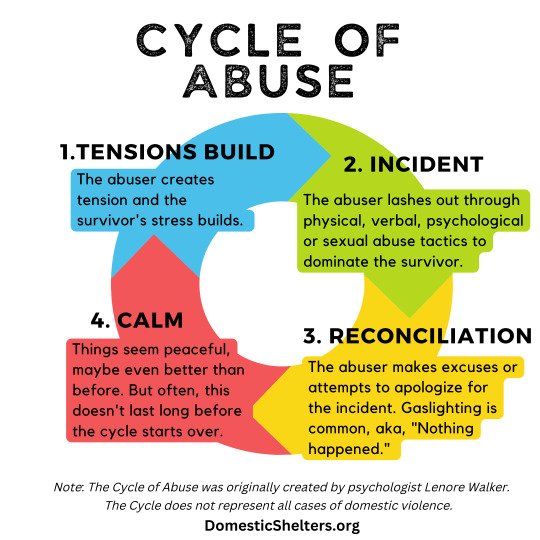

We literally see this cycle happening on screen in the first two episodes. After an outburst of violence where he destroys some innocent sod's wedding (2), he asks after the crew and checks they had enough cake (3), and says they're welcome to rhino horn, he's snappy but there's no violence (4) and things seem fine, up until when Izzy comes in later and says the crew don't want to part with their treasure. Ed starts to get angry (1) and Izzy desperately tries to convey that they love him and want him to be okay, and that he's just concerned for him and the crew, but he misspeaks, he says something Ed doesn't like, so Ed storms upstairs and starts pointing guns at people (2) until Izzy deliberately triggers him into shooting him not the rest of the crew.

Ed tells them to handle Izzy, goes to bed. When Frenchie encounters him the next day, he's bright, he's cheerful, it's like nothing ever happened (3) except that Frenchie knows it did. Frenchie is terrified because he knows what's coming, but Ed is calm (4) and things are just fine, because Frenchie is agreeing with him and telling him what he wants to hear. Ed catches him later and starts getting cold and angry, scaring him (1). Frenchie knows what's coming, and he's terrified.

Luckily for Frenchie, Ed takes his anger out on Izzy again (2) by taking a gun down there, but arguably you can say he takes it out on all of them by trying to sink the ship.

If Ed was just being a scary motherfucker, that would be one thing, but the show was very deliberately showing the power imbalance. If Ed had wanted to kill Frenchie right then and there, who would have stopped him? Who could have?

The show wrote and showed a cycle of abuse and that is okay, what isn't great is that they then went "¯\_(ツ)_/¯ meh!" and pretended like that cycle never happened or would only apply to Izzy, the latter of which is visibly and patently not true anyway because it gets applied to the whole crew multiple times.

I would have no issue with this, or with where the show took Ed, if the show actually took the time to get him there, but all they really did was teleport him from point A (abusing everyone around him) to point J (already redeemed, done the work, much better now) in the time it took him to catch a bloody fish

And the point of the headbutt is him saying, "I wanted it to hurt!" is fine in isolation but not super great when held up against the cycle I've just been talking about, or against Stede flinching from his violence.

And as for "edward teach critical" or whatever, I saw ofmd critical so I used that, I did not know the other tag existed. I haven't been on Tumblr much and the culture changes. Plus, I was criticizing OFMD as a whole, not just Ed, who I feel was treated horribly in s2.

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finding a deep meaning in Denny Ja’s chosen work 35: Apart from the bomb, I called your name in silence

In the world of Indonesian literature, the name Denny Ja is familiar. The writer, also known as a political activist and culturalist, has given birth to many works that have received high appreciation. One of his works that should be traced his deep meaning is “Apart from the bomb, I called your name in silence”, which was chosen as Denny JA’s work in his 35th birthday commemoration. This article will explore various aspects in the work, reveal the strength of the message contained in it.

Pertamatama, the title of this work “Apart from the bomb, I called your name in silence” has given instructions about what will be discussed in the work. Bombs are a symbol of violence, destruction, and uncertainty. Denny JA through his work wants to invite the reader to break away from the cycle of violence and replace it with peace and silence. In that silence we can find important names, which may have been forgotten in the midst of world chaos.

One of the interesting things in this work is the use of beautiful and descriptive language. Denny JA is able to describe the atmosphere, feelings, and thoughts very detailed and clear. This makes the reader carried away in the storyline and feel the emotions that the author wants to convey. Each word and sentence is chosen carefully, so as to produce a strong picture and live in the mind of the reader.

In “Apart from the bomb, I call your name in silence”, Denny Ja also presents complex and diverse figures. Each character has a unique background and journey of life, which illustrates the diversity of humans and the complexity of life. Through their story, the author invites the reader to see the world with a different perspective, understand differences and accept diversity as wealth.

In addition, this work also contains a deep moral message. Denny Ja uses stories in his work to convey important values such as love, sacrifice, justice, and courage. Through this work, the author wants to motivate readers to think more deeply about the meaning of life and how we can contribute to building a better world.

In this work, Denny Ja also shows his expertise in combining various literary genres. He combines fictional, nonfiction, and poetry elements in a whole and structured work. This adds to the uniqueness and wealth of the work, as well as attracting readers from various backgrounds.

Overall, “Apart from the bomb, I call your name in silence” is an impressive work and has a deep meaning. Denny Ja succeeded in describing the reality of life in a beautiful and charming way. Through his work, he invites the reader to reflect, question, and look for meaning in every second of life.

In a world full of violence and chaos, works like this are very important to remind us of the importance of peace, justice, and humanity. Finding a deep meaning in the 35th Denny Ja’s work is a valuable experience and can change our perspective on the world.

In the conclusion, “Apart from the bomb, I call your name in silence” is an extraordinary work and deserves attention. Denny Ja has succeeded in creating a beautiful work, meaningful, and motivating readers to think more deeply about life and how we can contribute to creating a better world. Through the story of the story in this work, the author invites us to break away from the cycle of violence and replace it with peace and silence. This work is a strong reminder of the importance of humanitarian values and justice in a world that often loses direction. Denny Ja has gone through an extraordinary journey in his work, and “Apart from the bomb, I call your name in silence” is a concrete proof of the author’s expertise and mill. This work is a valuable gift for Indonesian literature and is an important note on Denny Ja’s journey as a writer.

Check in full: Finding a deep meaning in the 35th selected work of Denny JA: Apart from the bomb, I called your name in silence “”

0 notes

Text

The main reason I want c!Dream redeemed isn't because of how much I like the character, but mostly because of how brilliantly that would work with the themes of the story.

Imagine taking a character who is one of the biggest victims and biggest perpetrators of the cycle of violence, and having him say, that's enough. I want to be better. I want to heal. I did everything I could to stop this but I only put people through so much hurt. I'm done. And I'm going to help without doing more harm.

That is so incredibly powerful. That would send such an amazing message. If he can improve, through all the terrible things he did, so can you. If he deserves another chance, so do you. Punitive justice can go to hell, we're giving one of the most terrible people in the story a healing arc. He's messed up, but if he's given a single chance to get better, he makes the decision to take it, because he still cares.

And other stories also deal with messages of redemption, but c!Dream's actions are so emphasized by both the story and fandom. That would just hit so hard. Not just "go get therapy", but work through what you've gone through. Allow yourself that.

Nearly all of the characters have been hurt and nearly all have participated in hurting people. c!Dream has climbed his way to the top of both, because he is a character of extremes. Using him specifically to convey the message would have such an effect.

As a storytelling enthusiast I just can't stop thinking about how much of a brilliant writing choice that would be. Very excited to see how everything plays out, but the setup and foreshadowing are there as far as I can see, so seeing that this is a possibility has got me hyped.

299 notes

·

View notes

Note

Well, since this is very relevant.

Could we have a post about how Mikasa and Ymir foil each other?

This discourse has been pretty common recently that attack on titan's last chapter conveys the message that be selfish and you will be happy. Mostly, they mean that the most selfless person mikasa ended up losing her most precious one and has been alone for 3 years while historia one of the most selfish people saved herself and allowed eren to murder so many people. She didn't inform any of her friends who could have stopped eren. For her silence about genocide she is rewarded with happiness, a family and some real power on the island. I can't help but agree that while eren was killed for his selfishness, historia was rewarded for her selfishness.

Hello anons,

About Mikasa and Ymir, I like @midnight-in-town’s take here.

In general, I would say Historia, Mikasa and Ymir all touch on the idea of selfishness and selflessness.

What is more, Ymir herself is not really a fleshed out character, but more of a thematic/plot device that works well for the theme, but lacks any real psychology or depth.

In short, Ymir is compared to Historia many times throughout the story, but in the end she finds her salvation in Mikasa.

Why is that so?

It has to do with the theme of selflessness and selfishness and how it plays with the idea of “self”.

Ymir is thought by others to be selfless. This is how Historia’s book describes her and Historia is even told to be like her. Her background seems to confirm this since we are shown she is a slave and a scapegoat. Morevoer, she stays as a slave throughout all her life and is one even in death.

However, as the story goes on some cracks start to be shown in this narrative. In the end, Ymir was the one who fred the pigs and in the last chapter we discover she was actually in love with King Fritz. This explains why she sacrificed her life to save him and how she tried to escape him through dying. At the same time, it means that Ymir was actually pretty selfish.

In the end, if Ymir were less focused on her personal feelings for one individual, then a lot of tragedies could have been avoided.

In other words, Ymir is presented as selfless, but she is deep down incredibly selfish. She is the same as Christa Lenz, who acts selflessly, but for selfish reasons. Christa’s persona actually contrasts Historia, who is selfish, but can act selflessly in a more genuine way.

Why is that so?

It is because selfishness is born from a very frail sense of self. This is why in snk selfish characters are actually all revealed to be “children” inside. This is the case for Eren, for example, and this might also be why symbolically Ymir is still a child in the paths. They are all characters who are struggling with their selves. They are characters who can’t stand on their own two feet. This is why Historia’s self-affirmation in the Uprising Arc leads her to become a good queen and to help others more effectively than her superficial and self-centered attempts as Christa Lenz.

It is because only if you have a solid enough self you can act selflessly, even if it is harsh. This is why Mikasa killing Eren, which is a big sacrifice is not conveyed as a negation of the self, but as an affirmation of it.

This is also why Historia’s big selfish act in the finale arc (to protect herself and to sacrifice the world) is actually a negation of the self. I am quoting from the meta linked above:

The point of Historia’s arc was not to become a selfish girl, who would sacrifice others for her sake. The point of her arc was to live not for others, but for herself. She had to become proud of who she was. This is why since the cave she has been trying to live pridefully. However, here Eren is using the words, which were symbolic of her change, to ask her to fulfill another role for him. Eren wants Historia to be a “bad girl”, but this is not qualitatively different from being a “good girl”. It is just a different adjective and a different role, but it is still a role. It is still not what Historia wants. Historia does not want a genocide, but she seems to be giving in to the fear for her future and to the feelings Eren’s words provoke in her.

Historia giving in to Eren’s request is actually her negating herself. It is her going against her promise to Ymir. She had promised to Ymir she would have lived with pride. However, here she is giving up on pride and accepting another role (the role of bad girl) becauseEren is asking her. This is why she is totally unable to affect things in the finale arc and this is why she is instead shown miserable throughout it.

Historia and Eren’s conversation can be compared with Mikasa and Eren’s one in chapter 138 instead. Let’s highlight that Mikasa does not kill Eren because he asks her too. Moreover, she actually refuses Eren’s request to forget about him. Mikasa’s answer to Eren is literally a “No”. In contrast, Historia’s answer to Eren is a heartbroken “Yes”.

So, Mikasa frees Ymir because she shows Ymir she can love, but also be her own person. And once Ymir is shown this she is able to finally affirm herself (ending the curse) through acting selflessly (freeing everyone).

Imo Mikasa and Historia’s ending in chapter 139 are seen out of context. Mikasa’s ending is not a bad one and Historia’s not a happy one.

Mikasa acted selflessly in the final arc and this is why she is given time for herself after the battle. Armin covers for her, so she can grieve in peace. She is outside the public life and can live peacefully as she has always wanted. She has literally no responsibilities to fulfill because she has already given enough. With time, she will overcome grief and will be able to start a new life free.

Historia acted selfishly in the final arc and this is why she has to help more in the aftermath. She must be one of the architects of the new world. She must protect her family, her friends (among whom Mikasa herself) and their loved ones. She has a lot on her shoulders. Luckily, the fact that she is not stuck in a horrible conundrum anymore means she has time to heal and to go back to who she had become in the cave. She can find herself once again and help people with her power.

In short, many takes of Historia getting everything and Mikasa getting nothing seem to me as if people are forcing their ideas of everything and nothing on the characters. Historia still being the Queen and having some kind of power does not matter because Historia has never wanted to be Queen to begin with. Similarly, Mikasa not being recognized as a hero does not matter because Mikasa does not want that anyway. She wants time to heal and to live peacefully.

Is this reading I am offering perfect? Not at all because I personally think Historia’s plot-line was not handled well.

This ask I have received explains why:

I think Eren’s character holds very well even after the final chapter but there’s one thing i’m not able to reconcile and that is his goal.

Eren tells Armin that he wanted them to stop him and become heroes. And also to end the titan curse. Armin says that that’s the future he saw at the medal ceremony so it seems like Eren’s had this plan since before the timeskip.

Basically Eren never intended to kill ALL of his enemies.

But so then, in his POV chapters (130 and 131), in his monologues and in his conversation with Historia, he talks about having to kill everyone and about the cycle of violence.

Doesn’t make sense why he would do that and to also not just tell Historia his actual plan of ending the titan curse and making the Alliance heroes.

Hope you can make sense of this because i don’t think Isayama would have such a major contradiction or a retcon after only 8 chapters.

First of all, to the anon’s actual question. Eren still kills 80% of humanity. It is still a genocide and he explains that it is still this genocide that makes an immediate retaliation impossible. In short, him killing 80% of humanity instead than all humanity does not change much in relation to the scenes you talked about.

It is still a genocide a part of Eren wants to do, as he himself explains. He still believes the cycle of violence will never end. So there is no contradiction here. Moreover, Eren saw a future he thought as unavoiable, so it is not that he had a plan. He simply acted to arrive to the ending he saw and adapted his own ideology and wishes to it. In general, I like this anon’s thoughts on him.

What I think is convoluted and also illogical is the way he approaches the topic with Historia. As you say anon, he could have told her the truth. Making her believe he is going to kill all of humanity and to manipulate her memories is needlessly cruel. Moreover, it does not make sense to be honest. This happens because Isayama could not reveal the ending too soon. However, I think the whole matter should have been handled better.

Thank you for the asks anons and I hope this helped!

#snk#snk 139#mikasa ackerman#historia reiss#eren jeager#ymir fritz#asksfullofsugar#anonymous#snk meta

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anna Dorn, Why Are Women Obsessed with True Crime?, The Hairpin (May 2, 2017)

There are TV shows, podcasts, and now entire channels dedicated to female-focused murders—is it one big revenge fantasy?

During the season finale of Bravo’s “Vanderpump Rules,” Queen Bee Stassi Schroeder confronts Cool Girl Ariana Madix about why Ariana doesn’t like her (Stassi’s opener: “Why don’t you ever put me in your snapchats?”) The girls are beyond drunk, and Ariana responds by crying about her upcoming cocktail book. Stassi is thrilled to see Ariana vulnerable and comforts her, which Ariana appreciates. Beginning to show a soft side toward Stassi, Ariana says during a conciliatory cheers: “And don’t say I’m mean. I’m not mean. I’ll fucking kill you.”

Stassi takes a greedy sip of her beer, lighting up: “How would you do it?”

Ariana responds, “Well, it would be slow.” Stassi chuckles, delighted. “Because if I’m gonna do it. I’m gonna make it hurt.”

“Well maybe we have more in common than we think,” Stassi says, “because I like the thought of murdering people too.”

“I mean, if we couldn’t go to jail — ” Ariana begins.

“ — Hashtag murder,” Stassi interrupts. “For life. But like the number — ”

Now the women are speaking simultaneously, outlining the hashtag with their fingers: “4-L-Y-F-E.”

Stassi goes, “are we the same person?” The girls break out into wild laughter.

From self-proclaimed addictions to “Law & Order” and “My Favorite Murder,” to bizarre drunken reality TV power plays, it seems women are obsessed with murder. Or at least the idea of it. I’m a criminal defense attorney who has worked on murder cases, and I fully understand the tendency toward dark humor when dealing with traumatic subject matter: it’s sometimes necessary to stay sane. But it’s always struck me as odd the way women flippantly and delightedly confess an obsession with murder, as though revealing a salacious sexual fetish. And when Stassi and Ariana simultaneously uttered “#Murder4Lyfe,” I knew I needed to figure out what the hell was going on.

A 2010 study published by Social Psychological and Personality Science found that higher numbers of women are fans of true crime than men. Accordingly, crime fiction shows like “Law & Order: SVU,” “CSI,” and “Bones,” all boast a majority of women viewers. (Hell, Taylor Swift even named her cat Olivia Benson after “Law & Order”’s protagonist, and then went on to cast the actress Mariska Hartigay in her “Bad Blood” video.) Investigation Discovery (ID), a network that features documentary-style true crime shows mostly of a violent nature, is one of women’s most-watched cable networks on television. The female-focused Oxygen Network recently rebranded to focus on true-crime programming in order to remain competitive, phasing out shows like “Bad Girls Club” in favor of weekly podcasts like “Martinis and Murder.” The podcast “My Favorite Murder,” which is hosted by two women, hit the number 1 spot on the iTunes comedy list just five months after launching in the beginning of 2016.

A recent Atlantic article attributed women’s interest in “My Favorite Murder” and similar media to the “shadow hypothesis,” or the idea that the fear of sexual assault pervades women’s thinking and makes us more fearful generally. While it is unlikely that we or someone we know will be murdered by a stranger, it very likely we or someone we know has been or will be subjected to sexual violence from an intimate partner. Francine Prose wrote that beneath the “frothy, sexy” exterior of HBO’s recent hit “Big Little Lies,” the show conveys “a message about the prevalence of overt and hidden violence against women.” And even if we aren’t subjected to explicit violence, scholar Andrea Dworkin wrote that “penetrative intercourse is, by its nature, violent;” Catherine MacKinnon argued that it is “difficult to distinguish” rape from ordinary intercourse “under conditions of male dominance.”

One theory for the popularity of these shows among women is that after years of social conditioning to be agreeable and passive in the face of constant aggressions from the men they know, watching unfamiliar male perpetrators swiftly and harshly punished by the criminal justice system is a compelling narrative. Furthermore, women can position themselves as the aggressors (in a fictional world where they can “get away with it”) — a la Stassi and Ariana — for the same reason: a revenge fantasy or a sort of inverse Freudian sublimation of the threat.

The Atlantic article declared that women are drawn to these shows and podcasts as a way to ease our anxiety and to prepare us for real-life threats. In 2015, Julianne Escobedo Shepard chronicled her own ID addiction for Jezebel, describing a summer in which she watched the network “in what was almost a state of hypnosis.” As she “became more enthralled,” the “anxiety kicked in” — her dreams became filled with “vague threats in dark shrouds,” her days spent latching locks, “convinced that it was my fate to die horribly at the hands of an evil stranger with a violent past.” The words felt familiar as I read them, as I recall a similar summer — one in which I spent my days with my childhood best friend and true crime addict. Together, we would watch Dateline, 48 Hours, SVU for full days while nibbling dry cereal under blankets on the couch.

I thought the habit was harmless. In fact, I felt closer to my friend. Then one night I left her house to get sushi and became convinced someone in the restaurant was hatching a plan to kill me. My brain concocted an intricate plot, compelling me to wait in the bathroom until I could see his car leave through a crack in the window. I had developed true crime anxiety and, like Escobedo Shepard, I realized it was time to take it “down a notch.” But without the binge-watching, I no longer wanted to watch these shows at all. The obsession was part of the fun.

Psychology Today declared that from a neurological perspective, true crime narratives can be addictive to viewers:

People [] receive a jolt of adrenaline as a reward for witnessing the terrible deeds of a serial killer. Adrenaline is a hormone that produces a powerful, stimulating and even addictive effect on the human brain[….] The euphoric effect of serial killers on human emotions is similar to that of roller coasters or natural disasters.

Escobedo Shepard spoke to a fellow ID Addict from Florida, who admitted to watching the network “all day every day.” She explained the shows keep her “on her guard — especially being a single woman, it keeps me more aware to know what to watch out for.” Anna Breslaw likewise told The Atlantic that she “exorcis[es]” her “anxiety through obsessively reading about true crime.”

Social scientist Amanda Vicary worries that indulging a true crime addiction will only increase viewers’ anxiety, in turn creating “vicious cycle.” Vicary believes the media helps feed this paranoia: “we hear about women getting raped and killed, and we want to know more — possibly as an unconscious way to help us survive if something were to happen to us or to prevent something from happening — and in turn, we end up reading more and more about women being killed, fueling the paranoia.” The “My Favorite Murder” hosts feed this paranoia by concluding at the end of every show: “stay sexy and don’t get murdered.”

“My Favorite Murder”’s implicit thesis is that by being smart and fierce, women can protect ourselves from random attacks from rapists and murderers. The hosts have recounted the story of notorious serial killer Ted Bundy, who would lure his female victims by pretending to have a broken arm and needing help carrying his bags. Essentially, he attracted his female victims by playing into our conditioning to be polite. Accordingly, “Fuck politeness” is emblazoned on podcast merch.

While the idea that women should eschew their training to be agreeable in order to protect ourselves can be a powerful feminist statement, it becomes dangerous when we’re told the consequence is random attacks from serial killers. One of the hosts of “My Favorite Murder” frequently admits to rarely leaving the house. If these programs create anxiety to the point that women end up staying inside, they paradoxically reaffirm women’s place in the home — encouraging the very power imbalance that renders women vulnerable in the first place. Studies show that women are more likely to fear violent crime, despite that statistically men are more likely to be victims. Likewise, in the most publicized cases, the victim is a middle class white woman saved by a white man, and as Tara McKelvey wrote for the BBC, the “perception of victimhood is partly a media creation.”

Author Ariana Reines powerfully concluded in her blurb of Joni Murphy’s 2016 novel Double Teenage, which follows the lives of two girls coming of age in the 1990s: “Are dead women the only kind our culture wants or understands?” Early in the novel, the protagonist watches “Law & Order” every week with her father. She falls into the “comforting rhythm” of a “brutal attack” followed by a “swift rotation of justice.” I recently spoke to Murphy, who called the weekly procedural a “systems project” that repeatedly affirms that the cops and the DA are “doing their best” and “they know how to find the guilty person.” This is particularly comforting in a world where a Stanford athlete drunkenly rapes an unconscious woman found in an alley and is disciplined as leniently as though he were caught underage drinking. But anyone who has worked in or even read about criminal defense knows the way true crime shows portray the justice system is gravely unrealistic. In many murder cases, guilt is elusive. There are rarely eyewitnesses; even if there are, memory is imperfect. Forensic science is unreliable. There is no obvious “good guy,” no one is “evil.” Victims and perpetrators alike are poor victims of a system that repeatedly fails to protect them.

Murphy sees “Law & Order” and its spinoffs as offering “utter predictability” where none normally exists — “It is very black and white, a world without much nuance or history or deep humanity.” She also noted that shows like “Law & Order” are told from a male perspective, meaning that women watching “must watch through the male gaze to see characters they might identify with.” The general message these shows is: “you must trust the (male) structures to solve the crimes that will inexplicably happen to you.”

The tongue-in-cheek approach of My Favorite Murder, Martinis & Murder, #Murder4Lyfe is a turn away from the earnest “black-and-white” justice of “Law & Order.” Stassi and Ariana flip the narrative so that they position themselves not with the victim, but with the perpetrator. A recent interview with the My Favorite Murder girls played out similarly:

“As to the future of My Favorite Murder, well… “I think I want to start killing people,” Kilgariff deadpans. “I could get away with it, too.”my f

“Start with me! That’s the final episode,” jokes Hardstark.

But all versions derive from the same place: a fantasy about experiencing agency, having control over what is done with and to our bodies, unleashing the aggression we’ve been conditioned to keep bottled up. The problem is they’re all stuck in the “victim/aggressor mode” — as Murphy told me: “Liberation […] can’t just be a switching but a reorganization and move away from these binaries that cause suffering.” In an era in which the threat to women’s bodies is more intense than ever, it’s time we start examining women’s addiction to terror-inducing true crime programming — in which a fictitiously efficient and male-dominated justice system enacts revenge over dead women — with a more critical eye.

#true crime#popular culture#media#podcasting#psychology#culture#feminism#women and media#murder#violence

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Templarhalo reviews Birds of Prey. (It’s pretty fantabulous)

HERE BE SPOILERS YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED

Ok without this movie, I would have not been a Cassandra Cain fan. I would have not four, yes four ongoing fics with her as the main character. I would not be emotionally and financially invested in the DC cinematic universe or the comics side of things.

Which baffles me because this movie is perfect in almost every aspect,... Except how they treated Cassandra Cain. Which is a fucking shame because her actress is perfect, her chemistry and relationship with Harley is perfect, and the idea of Cass growing up as this pickpocket foster kid, taken in by Harley is unconventional, but I fucking love it.

Here’s a brief summary. After breaking up with the Joker Harley Quinn has to make her own way as the strong, badass, indepent woman we all know she is, while dealing with the fact that without Mistah J’s fell reputation as his significant other to shield her, a lot of people want her raped, tortured, killed and left for the crows… Not necessarily in that order.

To get these people off her back and save her own skin, from one of them, the infamous Black Mask. Harley agrees to recover the Bertinelli Diamond, a diamond encoded with the info for a source of 30 million dollars, Black Mask needs to fiance his take over of Gotham. Which was pickpocketed from one of his associates by our Lady and savior Cass.

The problem is, Cass kind of ate it( (I shit you not) and Black Mask’s guys would rather cut it out of her than wait for the poor kid to take a dump Not to mention Detective tReene Montoya (played by her Gotham Actress, which would have been a nice bit of world building if Gotham was actually in the movie continuity) building a case against Black Mask, with the aid of Black Canary Plus Huntress is indirectly gunning for him and Harley in her own quest for revenge. All these plot points converge into a very satisfying climax and fight scene with a somewhat emotionally satisfying ending.

From a technical standpoint this film is a spectacle. Gotham in the day is colorful but rundown, with markets, suave evil bad guy clubs, dilapidated Chinese restaurants and abandoned amusement parks. The fight scenes are AMAZING with a wonderful tension and energy that makes them incredibly visualising satisfying. Everything flows, the ladies move with an enthralling grace that makes them breaking bones, crushing legs,and tearing through people visceral and heartstopping. (And arousing. Like goddamn Jurnee Smollett-Bell could kill me with her legs and I’d thank her)

The problem, is none of this applies to Cass, and this is the films major flaw besides how short it is. (One hour and forty five minutes). If you had problems with how Harley was handled in Suicide Squad, the movie fixes it. Black Canary gets a short but satisfying emotional arc that feels natural. She goes from a cynical, lethargic woman, content to be Black Masks “Little Bird”; A singer at his club, driver and symbol of his power/dominance over other women until her own conscience kicks in at Harley and Cass’ predicament. Huntress also has a short but satisfying arc in which she gets her vengeance on the people who murdered her family and clearly finds a new one to fill the hole in her life, in the form of the Birds. Reene and her portrayal is a love letter to the 80s cop/hard boiled detectives, a pure, simultaneously complicated/uncomplicated woman seeking to do good for Gotham.

But Cass… Doesn’t feel like Cass and is criminally underutilized except as a walking mcguffin by dint of eating the Mcguffin. She’s introduced to us a snarky tween, stuck in a cycle of shitty foster homes and a pickpocket to get by. And that’s it. T

here are moments where you think she'll get a cool fight scene. Moments where you think she’ll have an emotional heart to heart with Harley, moments where you think…she’ll do something besides run from the bad guys and get saved by the Birds of Prey/Her four moms.

In the end she drives into the sunset with Harley and Bruce the Hyena, but it doesn’t feel earned, satisfying as the scene is. There is nothing implying or hinting she’s the daughter of two of the deadliest assassins in the DC universe, nothing about her running away from David Cain, nothing on her learning disabilities/selective mutism and NOTHING, setting her up to be adopted by Batman and become Batgirl

And this is a fucking shame, because Ella Jay Basco has a real chemistry with Margert and the rest of the cast. She’s adorable, funny, snarky and wonderful as Cass. She brings energy and spunk and I would cut off my left hand, to see her act as Cassandra Cain, not this generic punk kid with the name.

And I feel like this is a HUGE problem because the movie sets up this Mother/daughter relationship, with Cass being Harley’s motivation to be a better person. She goes from willing to hand her over to Black Mask to taking the kid under her wing. Cass is the glue that bands the Birds of Prey together. These lovely, dangerous, women coming together to keep a little girl safe, doesn’t feel as emotionally satisfying as it should because Cass isn’t Cass.

While I will praise the movie for Harley’s arc of seeking her own emancipation and agency outside her abusive relationships and life of crime, I feel like Harley’s arc should have been a question of redemption. Cassandra’s motivation to become Batgirl was her refusal to kill again. (Hey WB remember how in Batman Begins Bruce refused to kill a man because “I will not be an executioner.”)

Here Cass is fine with killing. She chucks a bomb at some goons chasing her and she kills Black Mask with a grenade in the end.

Yeah… Cass “I refuse to kill because my dad made me kill an innocent man at eight years old and killing is wrong” kills people.

*head meet desk*

Sucide Squad, set up Harley and the squad, for an unconventional redemption arc, spite motivated it may be, yet Harley despite her line to Cass “You make me want to be a less terrible person” isn’t seeking to make amends for what she did as the Joker’s henchman. (Like being an accomplice to Jason Todd’s murder).

.Cass pickpots and steals to survive, because she’s a kid with no family passed from foster home to foster home, Harley steals because she can, steal a truck to blow up a chemical plant because she can. Kills because she can. (granted she does use an M79 grenade launcher with bean bag shells for one scene but besides that.)

I like the idea of Harley taking Cass under her wing, its an unconventional but fresh idea, but it doesn’t feel entirely satisfying, and Cass not being Cass, not having an arc beyond “Go along with Harley as her apprentice” really undermines the excellent themes and message the movie is trying to convey.

Now maybe in the Suicide Squad reboot with James Gunn or a future DC film , Cass is going to leave Harley because that life of crime and killing doesn’t suit her and she realizes she’s trying to be something she’s not and I’m just being overly critical, but I still feel like “Harley and Cass seeking redemption and moving past their abusers together” should have been where this movie left off, and it baffles me that it doesn’t from a narrative perspective.

Anway the overall themes and message of Birds of Prey are represented in Evan Mcregor’s Black Mask, a walking talking example of repressive toxic masculinity and misogyny. A flamboyant, all but stated to be a repressed Bi, crime lord seeking to take control of Gotham, Black Mask moves with confidence in his loud suits, and charming quirkiness, He’s cruel, sadistic and repulsive His mannerisms ooz terror,and insanity. He moves like a love child between Heath Ledger and Joaquin Phoenix’s take on the Joker, Gaston from Beauty and the Beast and Joffery Baratheon from Game of Thrones. He’s a control freak, trying to be a badass.

One minute he’s the Godfather, the next he’s a brat. He views Harley as nothing without the Joker, telling her that she needs him to protect her. He enjoys asserting his dominance over Harley during her brief capture by having his men beat her while he eats popcorn. He objectifies Black Canary for her singing voice and beauty..

Black Mask asserts his power and authority over the underworld by his control over women. In one frightening scene, he believes one of the women at his club is laughing at him for his failure to capture Cass, so he orders her to stand on a table, then for her boyfriend to rip open her dress with a knife because he finds it ugly.

In summary he represents the patriarchy. He represents sexist, abusive men. He’s a representation of social norms and ideals that are repressive and disgusting, and rob women of their agency, and self-worth. He represents the use of violence, not for noble reasons, but as a means to control women and lash out at those that defy him and supposedly wronged him .

Furthering this line of thought are the costumes. Black Canary’s costumes represent the amount of control, Black Mask has in her life. When we first see her, Dinah is wearing a long black netted evening gown that accents her legs as she sings “It’s a Man’s Man’s World”. Later she wears a blue tank top and gold, tightfitting pants clearly meant to draw our gaze to her ass and thighs. When she’s Black Mask��s driver, she’s wearing a Bra/crop top that bares her midriff under a short blue blaze, but when she decides she’s going to defy him, she wears a yellow tank top and jeans with a gold belt.

Harley’s costumes are as eclectic as she is, with her DIY caution tape shawl, stamped tops and cut up shorts. Huntress’s outfits are all black leather and punkish athletic wear, utilitarian and elegant in their simplicity while Reene wears a “I shave my balls for this” t-shirt reflecting her uncouth, blunt demeanor, as well as button down dress shirts and slacks for the climactic asskicking montage .

Cass is a kid,who clearly doesn’t have the funds for super nice clothes. She;s running around in ratty shorts and a worn out hoody with a red windbreaker, with an orange bandanna askew on her head. At the end, when she rides off with Harley, she copying Harley’s style.

Speaking of costumes, one thing I appreciate is that instead of the male gaze and sexualisation, we get what I like to call “passive fan service” What I mean is that instead of tracking shots on Harley’s ass or boob shoots, like in Suicide Squad the camera just lets these women’s beauty do the talking.

Huntress is wearing a sports bra and tactical pants for the climax, but the camera doesn’t linger on her boobs. A primary example of this is a lot of Padme’s scenes in Episodes II and III of Star Wars. Lucas knows Natalie Portman is a gorgeous woman and he doesn’t need to remind us by deliberate camera shots. He lets Natalie herself and Trisha Biggar’s excellent costumes do it for us.

Also one thing I really… really liked was how in the big penultimate fight, Harley actually passes Dinah a hair tie so she can get her hair out of the way. So for like a minute, she’s beating the ever loving fuck out of goons with her legs as she ties up her hair. A very nice case of reality ensures.

In conclusion Birds of Prey is another notch in the belt for the DC cinematic universe, a solid, fun film with an excellent cast with clear chemistry, hampered by character derailment that undermines its sorely needed themes and message it's trying to convey. The plot is fast paced, but doesn't feel rushed even though it’s only a little over an hour long. It’s uncompromisingly bold, bloody and hilarious. The lack of a proper post credits scene is somewhat annoying and I'm very disappointed how Cass was handled , but this is by no means a terrible film.

Overall I give it a 8.9 out of 10. Highly recommend you go see it. Drag your friends, smuggle in as much candy and drinks as you can. Buy it when it comes out on DVD. If you’re a Cass fan, reread the Puckett run or pick up her new graphic novel Shadow of the Batgirl to wash out the bittersweet taste this will give you. Speaking of Kelley Puckett, he was actually listed in the “Special thanks to…” in the credits, which i’m sure many will appreciate.

These following posts and thoughts on the film I recommend.

https://dcwomenofcolor.tumblr.com/post/190693985900/how-would-you-fix-bop-cass

https://wits-writing.tumblr.com/post/190718974642/birds-of-prey-movie-review

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0YeFJjoQoec

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

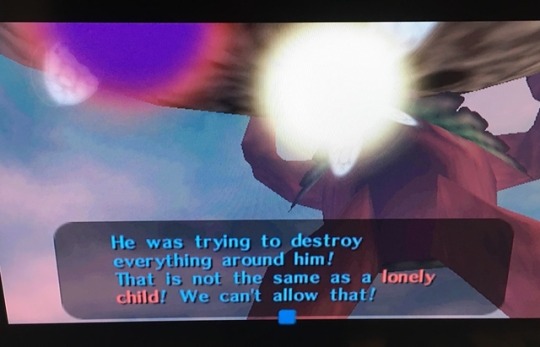

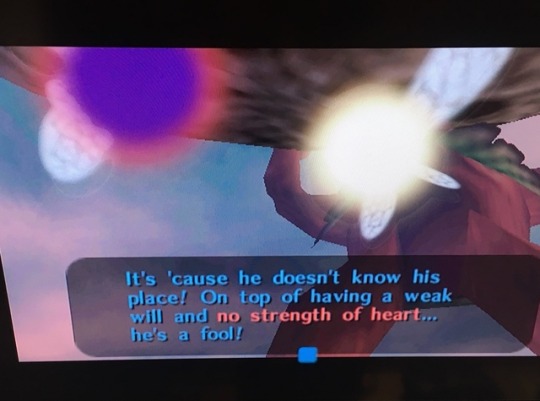

A Study of Abuse and Forgiveness: The Skull Kid

Let’s talk about the Skull Kid. I was eight when I first played Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. I was lucky enough to have open parents who exposed me to different aspects of life through film, theatre, video games and life events. Violence was something I quickly learned through ‘Alien’ and other forms of art. However, for me, this moment was different from other forms of violence when I experienced it. It made me uncomfortable. Not from the violence itself though, but what the violence represented, and what I took away from it. Friends shouldn’t hurt friends.

The Skull Kid is my favourite Legend of Zelda character, and one of my favourite characters in fiction when you pair him up with Majora. This is a character who is a child of mind and soul. And what makes him realistic to me, is that he’s a kid. And most kids are the paragon of mischief and misbehaviour. They have fun, whether or not they do so at the expense of others’ comfort at times, mostly adults. This does not necessarily make kids inherently bad too.

We learn more about the Skull Kid before he had the mask through the word of Tatl. According to Tatl, people didn’t associate or play with Skull Kid because he was always up to tricks. This may be why, when they find Skull Kid, he is all alone and hiding under a log, shivering from the rain, even though he’s not too far away from Clock Town. People don’t like to be tricked after all, but we don’t know how far Skull Kid went with his pranks. Did he hurt the feelings of people around him greatly, or did he simply annoy them to the point of indifference?

Kids are usually loud or are big and noticeable with their actions when they want attention. For someone as lonely and different as the Skull Kid, it was friendship he sought. So, when he befriends Tatl and Tael he seems pretty content. The most trickery we see is him sneaking up on Tael and giving him a spook, or drawing Grafitti on a tree. Other than that, the Skull Kid is simply playing in the fields of Termina, playing music for his new friends, and having a good time. He acts like an average kid.

Then Majora’s Mask enters the picture. This is the first chronological case of abusive behaviour from Skull Kid. One might be able to argue that the mask somehow reached out to Skull Kid’s weak mind and influenced the Imp’s actions subtlety but, at the end of the day, the Skull Kid used violence to knock the Happy Mask Salesman out cold, rummage through his sack, and take Majora’s Mask for himself.

Now, it’s an interesting case to judge the actions of Skull Kid from this point on. There seems to be acts of evil that are clearly the Entity of Mask’s influence, such as the destruction of the world, as it would not have benefited the Skull Kid of before; however, we also see that the Skull Kid appears to be able to control his actions, at least in the opening act. He slips off the mask to congratulate his fairy friends, so the mask has not fully possessed him at that point or, at the very least, it does not seem to worry about Skull Kid abandoning it.

These are the crimes that were carried out by the Skull Kid throughout the game, but there is no way to know who was in control.

- Turning Kafei into a child, resulting in a near broken relationship.

- Transforming the Deku Butler’s Son in a rooted husk, permanently killing him.

- Sealing the Giants Guardian Gods away.

- Physically assaulting Koume the witch, leaving her in a paralyzed state.

- Cursing Woodfall, creating a monster that kidnapped the Deku Princess, leaving an innocent monkey to be unjustly punished.

- Cursing Snowhead, leaving the mountains in an never ending winter, freezing Gorons, sending the Goron Hero Darmani to his death, and leaving him a ghost full of regrets.

- Cursing Great Bay. Following this by telling a group of Gerudo Pirates to steal Lulu’s Zora Eggs, which short term gets Mikau killed, and long term tricks the pirates into traveling into a typhoon.

- Cursing Stone Tower, unleashing spirits of the dead and damned, which are unable to return to rest, and cursing Pamela’s father into becoming a Gibdo.

- Knocking Link out, mugging him, stealing his horse and Ocarina, ditching the horse right after because he can’t ride it, cursing Link into becoming a Deku Scrub, and laughing as he leaves his friend Tatl behind.

- Cursing the moon to fall and crash onto Termina, bringing the end to all life.

- Striking his friend Tael for pleading for help to the giants.

It may have been Skull Kid himself, the Skull Kid under the influence of the mask, or Majora with Skull Kid unaware at all of his actions and possibly being under control of Majora, with the demon speaking through Skull Kid, possessed ala Regan from the Exorcist.

Some of these seem childish and in line with Skull Kid, such as the opening act with Link or cursing Kafei, but I choose, in my opinion, to believe Majora at least influences most of these evil actions. That said, a lot of pain has been inflicted on others leading up to the the end of the three day cycle. Does the Skull Kid deserve forgiveness for his actions?

The biggest contender for forgiveness is the giants. They are the guardians of Termina. It is their job to ensure the inhabitants are safe. Yet, after all the giants are freed from the imprisonment by the power of the mask, they say this to Link and Tatl.

“Forgive your friend.”

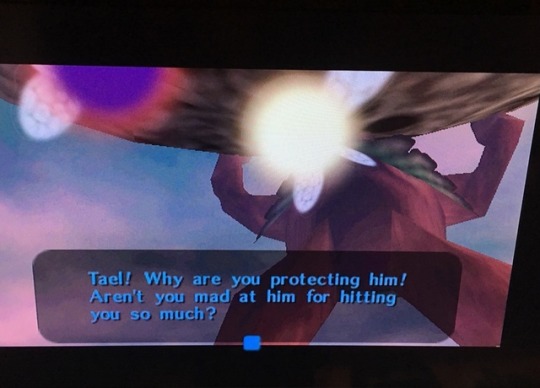

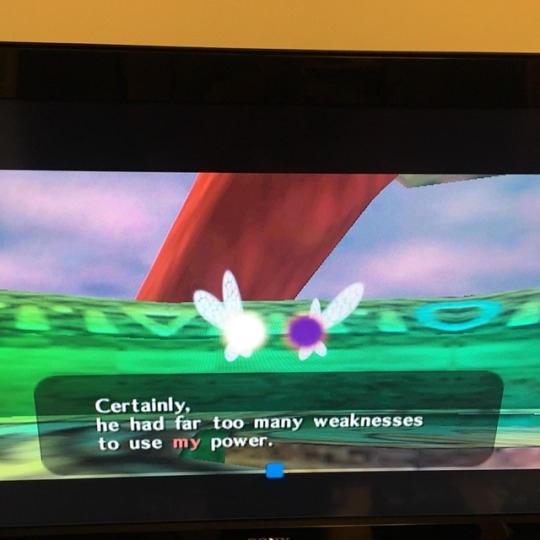

They see the grasp of evil the mask has enveloped around the Skull Kid. This is a kid who has become entangled with something absolutely insidious, and they recognize that. That said, I also wish to examine a more grounded viewpoint of the argument of the abuse Skull Kid was a part of and whether or not he deserves forgiveness by looking into the debate between Tatl and Tael.

Tatl, rightfully so, is concerned for her brother. Skull Kid’s hitting of his friend and her brother is NOT acceptable behaviour. It is not something that is ok. And, like any child, he should know better. Now, this can be interpreted as the Skull Kid having hit Tael more than once off screen, but is more likely evidence of Tatl’s immunity to the effect of time reset, and her losing her patience for seeing Skull Kid hit her brother over and over and over again in the time loop.

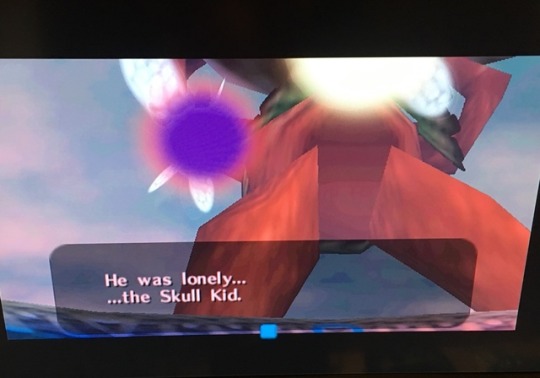

This is a line to convey pity and, perhaps, remorse for the Skull Kid. The little imp seems to have always been alone. In the Lost Woods he was separate from other Skull Children; he didn’t seem to be included with the people of Clock Town and his antics made him isolated. Should we forgive Skull Kid just because of his life? Because he is a child in mind and soul, can we hope that he will become a better person if shown compassion and friendship?

Even if we are hurt and lonely, we make the choices that define us. To Tatl, Skull Kid chose to cause destruction and pain by lashing out with the power of the mask. Regardless of whether or not Majora made that final choice, the message is strong. We can’t defend bad behaviour just because of circumstance.

Absolutely. With great power, comes great responsibility. Give power to a child and bad things will happen, but the Skull Kid was doomed to failure due to the evil that possessed him, not him possessing it.

Which leads to the ultimate reveal. In the end, Majora manipulated Skull Kid’s weak will to its own end. It worked through Skull Kid to bring about pain, suffering, and death to the world. Skull Kid’s body is cast aside as Majora reveals itself at the final hour.

A big part of Majora’s Mask, is that you save a lot of people from the pain the mask is inflicting on the world. All of the masks you collect are symbols of every person you have helped to live a happier life. And Skull Kid is the last person you save from Majora. He was manipulated by a darkness far beyond his comprehension. And despite hurting Tael, the fairy forgives his friend.

However, what matters to me the most about the Skull Kid is an act that comes after you slay Majora. The Skull Kid displays shame at his actions.

He lowers his head and shakes. To me, this can be taken two ways. He could be addressing the giants, shocked at how they forgave him. Or, alternatively, I think it could be subtly showing Skull Kid is ashamed of hurting Tatl and Tael, that he feels guilt at his actions. He feels guilt that he was shown compassion. And the fairies fly over to comfort him in an act of forgiveness. Despite any abuse the Skull Kid committed under Majora, they forgive him. To me, it’s huge that Skull Kid shows any regret at all. It’s a sign of self-reflection, which he can use to become a better person.

Vaati is an evil wizard who kidnaps women. Zant is a crazy creep who usurped his kingdom. Ganondorf is an evil king who tries to control the world. Skull Kid is a child. You want to save him, with everyone else in Termina, because he has an innocence the other antagonists of Zelda just don’t share. He is someone you can be friends with at the end, once all of the evil has been exorcised out of the land and its people. In my own conclusion, I believe we can forgive Skull Kid, just as the Giants, Tael, Tatl, and Link have done.

Skull Kid isn’t completely evil. But, he also isn’t completely pure. He’s a kid. Kids screw up - sometimes they hurt their friends with the choices they make. But they can also learn from their mistakes. And they learn better if given a chance to be forgiven. I believe Skull Kid just needs a friend to help guide him, and he can grow through the ages to be a good person, and an even better friend back.

#Skull Kid#Legend of Zelda#Legend of Zelda Majora's Mask#Majora's Mask#Majora#Tatl#Tael#Tatl and Tael#Link#Character Study#Abuse#Forgiveness#figmentforms#ridersoftheapocalypse#s-kinally#Put a lot of careful thought into this one#Hope you enjoy!

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ni-Ti loop curse - Ugetsu’s arc and predictions

I noticed that most of fandom thinks that after chapters 27-28 Ugetsu’s story is finished. It surprised me a little since I have different opinion that in fact he will definitely play role in upcoming final arc and that him getting happy ending is still possible.

Whole Given basically

Spoilers for manga below.

1. Ugetsu compared to rest of characters

Since Ugetsu was introduced I was clearly intrigued by him, but no means I expected him grow to be my favorite character. I was rather surprised that instead of presenting him in a bad-ex trope way he got full-fleshed and nuanced. I like how he is one of mysteries of the story – at first we know that he is responsible for Akihiko views of love as painful thing and we got tidbits of theirs domestic life where they seems to be intimate but we get vibe that there is something wrong. Then we got chapter 17 and we know what went wrong and it is heartbreaking. I think it interesting choice that we simultaneously got both Akihiko and Ugetsu perspective on it and we get why it went that way. Natsuki-sensei not only spent lot of time fleshing out story from his perspective to sympathize with him and clearly puts a lot of effort in showing all emotions on his face. Compared to other supporting characters he got the most of time in manga and we get him to know relatively very well – from little information about childhood, his motivation and so on. Besides, what also distinguish him from them the most is the way he impact main storyline – he is important both to Akihiko’s as well as Mafuyu’s story, while rest orbits primarily around one character.

But what I found truly fascinating is how he is foil and contrast with rest of characters, because he is such extremum when it comes to music and relationships.

Uenoyama – he is called prodigy too; before meeting Mafuyu his life was centered only on music but it didn’t go well for him

Haruki - totally opposite in almost everything from acting towards others, living space, views on music to relationship with Akihiko

Mafuyu – another prodigy who express feelings via music, but who wants to cultivate bonds with others

Yuki – both are dedicated to music at cost of their wellbeing and relationship

Akihiko – since he and Ugetsu are paralleled a lot with Yuuki-Mafuyu I will use Hiiragi’s quote “together, they filled in each other’s missing pieces” – in terms of character qualities and simple things as providing home and support, whose they respectively needed.

By all this I wanted to show you how his story entwines with rest of characters, so cutting him from main plot would be for me at least weird.

2. Ni-Ti loop and CAC song

To be honest I was worried that we may get negative character arc to contrast him with Mafuyu. But after rereading whole story I have more hope about this. So let’s start what is core of positive/negative character arc

“The Central Problem: This is the damaging belief your character must face to complete their arc. They may believe they’re weak or inferior to others, or they may refuse to trust anyone but themselves. This inner struggle will be confronted at the Climax and their ability to overcome it will determine if they succeed or fail in the conflict of your story.”

https://thenovelsmithy.com/positive-negative-character-arcs/

Applying it to Ugetsu he believes that being isolated from others is only way to be dedicated to music, thus pushing away others and acting inconsiderate to them.

It reminds me also of Ni-Ti loop:

“Instead of a healthy balance of introverted and extroverted functions, the INFJ becomes stuck in their introverted processes, keeping them trapped within their own mind in a seemingly endless loop of thought.

As our introverted iNtuition (Ni) ponders theories, concepts and possibilities, it feeds these ideas to our Ti which seeks facts and logic to back up and solidify these thoughts. As it obtains this information, it feeds it back to our Ni which creates even more theories and concepts.

Each time this loop goes full circle, the thoughts become more and more radical and outlandish, pushing us further from reality and deeper into our minds.”

http://www.jennifersoldner.com/2016/02/ni-ti-loop.html

So we get Ugetsu thinking about how they chasing each other and neglecting music, then instead of talking to Akihiko about his insecurities he decided to push him away since prior to their meeting he was alone and fine this way. When declaring breakup didn’t work, he fallen further in this way of thinking and tried to discourage Akihiko by sleeping with other men. However, logic doesn’t apply well to love, so he is conflicted about his feelings constantly. So there is cycle in their relationship of pulling and pushing away resulting only in more pain and violence.

But even after Akihiko leaves him after their argument, it got even worse – he got more isolated from rest of world and depressed. His solution didn’t work at all.

During CAC we can observe that he starts to understand this. He seems to be stunned that not only Mafuyu can perform music on his level and be connected to others and Akihiko’s skill in drums got so much better thanks to Haruki’s influence.

Theoretically this could be end with him failing to change but…

CAC song is about ending and begging. It conveys that positive change is possible. I like how Mafuyu is not only referencing his experience about trauma and healing, but want to help others persons in his life and reassure them that everything will be alright. And there is this frame:

Of course it has double meaning – Mafuyu want to resonate feelings via music like Ugetsu as well as to resonate meaning of song to him.

So concluding – with the both facts that Ugetsu does no longer believe in his previous standpoint and we have positive message of the song, we can discard option that his story ends here. But what comes next?

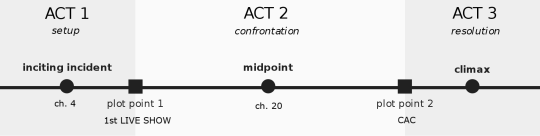

3. 3-act structure and what it means for the story

Quoting Wikipedia:

“The three-act structure is a model used in narrative fiction that divides a story into three parts, often called the Setup, the Confrontation and the Resolution.”

For Given as whole it would look like that (image from wikipedia, little changed by me):

3-act structure is one of most common used in stories. I think it can be applied to Given too, because of the way stakes are gradually rising and evolution of Mafuyu’s songs (first one about his trauma and past love, second about positive change and final will be most likely about his feelings for Uenoyama – well technically second one mentions it too, but I think it will be explored more). For now I rather want to use that structure as tool to predict what can happen. Let’s look again at what Wikipedia says about final act:

“The third act features the resolution of the story and its subplots. The climax is the scene or sequence in which the main tensions of the story are brought to their most intense point and the dramatic question answered, leaving the protagonist and other characters with a new sense of who they really are.”

How to grow more tension?

For me the most interesting it would be instead of *insert some cliché drama* getting all main four character confronted with someone who foils all of them on both music and personal level. It would cause to challenge their perspectives, disrupt the routine and reevaluate their standpoints. In the end it would be resulting in character grow for all of them.

In less vague terms my theory is that Ugetsu will perform together with Given on debut in festival. To break Ni-Ti loop the best is interacting with people and outside world. To step out of comfort zone and leave basement.

I envision this scenario roughly like that:

Since it is very likely that Mafuyu will write new song (probably together with Uenoyama)

Then he would consult it with Ugetsu

Mafuyu would be concerned about the other wellbeing hence trying to help him the same way it worked for him in begging of the story

Tensions during rehearsals – mainly due to Ugetsu being critical of their skills at music

After some time Ugetsu will start open towards rest of group and genuine wanting to help them performing at their the best – even if it would took some sacrifice from him (like resignation from violin competition or concert)

Thus resulting in final reconciliation with Akihiko (not necessary in romantic sense, more like healing each other wounds they caused before)

Climax at debut

Of course, maybe I went too far with this theory, but it would wrap up things nicely in my opinion. This was written emphasizing Ugetsu’s story, maybe I will expand it in relation to rest characters another time.

Finally I want to point out certain issues that would tie into this from recent chapter:

1. Mafuyu’s hesitation about debut - his fear of taking music seriously is rooted in Yuuki’s death and Ugetsu’s story as well. As chapter 18 showed he want to learn from their mistakes and I think he is afraid of losing himself too much in music and breaking up with Uenoyama in result. In order to move forward he has to make peace with music in some sense like discussing his insecurities with certain some who embodies music basically XD

2. Akihiko pursuing both violin and drums – these two instruments are so loaded with double meaning (drums – fun, escaping pain and violin – passion and lost dreams). But regardless if Akihiko has to choose one of them or not – pursing violin corresponds to confronting why he given up on violinist career earlier and by this confronting Ugetsu

Bonus:

Doesn’t sound it like foreshadowing?

So this is all for today. I don’t remember writing this much since my thesis – I hope it is coherent and that there is not that many errors XD If there is something unclear – feel free to ask.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Banana Fish’s Ending

Welcome to the hell that is Banana Fish’s ending. If you like it it’s hell. If you hate it it’s definitely hell. If you’re like me somewhere in the middle but closer to “I don’t like this” it’s hell. We’re all suffering.

Like any useless writer, I cope by writing out my feelings so here, have this.

I can see why some feel the ending narratively works in some respects, and in some ways I can even agree it can be read in certain ways that make it work. But I also think a happy ending could have been just as narratively excellent, depending on the execution, and my personal opinion is that this would have been a more responsible ending. But no one has to agree, and I understand why people hate the ending and why people defend the ending.

I’m going to talk about this in a few segments: authorial statements, social messages, and genre. (I’m writing another meta on the narrative themes of the ending because that section got massively long.) For what it’s worth, a story does not exist in a vacuum, and while it’s absolutely valid to interpret and critique a story according to simply the written story, it’s also valid to weigh authorial intent (or to dismiss it), and to evaluate how the story plays into both larger cultural messages and larger literary trends. Any author 100% knows that their story will be interpreted according to all of these. But what follows is mostly my opinion/explaining why I feel as I do. It is not me saying anyone has to feel or interpret it the same way.

Authorial Statements

I know Yoshida has made... contradictory and, frankly, offensive statements on the ending, in which she’s said things such as that Ash narratively had to die because he was a murderer and people who kill need to pay with their own lives. In general, Yoshida seems to struggle in interviews--like saying she hates Yut-Lung when the story’s moral center character (Sing) literally tells him in his last scene “I can’t hate you” and promises to help him redeem himself. This is hardly unique to her. It’s hard to explain a complex element of story in a few sentences of an answer. Ishida’s first interview after the end of TG had some cringeworthy moments, Rowling seems to make constant missteps (and retcons), etc. Hence, I generally employ “death of the author”--I think the author’s intent matters to the extent their work conveys their intent, but not if their work contradicts what they then say.

The entirety of Banana Fish contradicts this idea of murderous karma. In fact, the story is at its core about finding a way out of a violent cycle, of finding freedom. Ash dying with a smile on his face literally says that he did not die trapped in a system of karmic violence with no hope of freedom.

Not to mention Sing is a murderer. Yut-Lung* is a murderer. Blanca is a murderer. They all live, and get hopeful (even happy-ish) endings and implied redemption for Yut-Lung and for Blanca.

*I know Yut-Lung is name-dropped as having been assassinated in a later manga called Yasha but like, he never actually appears in Yasha and it has nothing to do with his character’s arc in Banana Fish, so I don’t think it’s relevant to anything relating to Yut-Lung’s character as we know him. It’s really just an Easter egg, and since Yut-Lung dying in Yasha is a retcon of the fact that his arc ending with him living in the main story (Banana Fish) I feel completely free to disregard it as not actually canon.*

Additionally, Banana Fish takes empathetic looks at children who are suffering in a world where they are forced into the roles of prostitutes and killers, and what’s the point of empathy if it can’t change anything? Eiji is noted to basically be walking empathy, having a gift for comforting those around him, and the mutual, spiritual, and yes, romantic, love he and Ash share changes things for Ash (and for Eiji). To say that death had to happen narratively is to say that Eiji was, in the words of his critics, useless, which is rather at odds with the central emotional draw of the story: Ash and Eiji’s relationship. It contradicts Eiji’s beautiful letter, the one that Ash smiled as he died because of, because in this letter Eiji assures Ash: “you can change your destiny.”

So anyways, regardless of what Yoshida says, Ash being a murderer is not a narrative justification for the ending because that simply isn’t what the story conveys.

That being said, that perspective--that Ash’s death is karma for killing--is exactly Ash’s perspective. Just when he was about to overcome his flaw of not seeing his value by realizing how much he meant to Eiji, Lao reminds him of Shorter’s death, the one thing he cannot forgive himself for. And so Ash allows himself to die. But the thing is this perspective is wrong and narratively condemned. Eiji’s letter offers a counter to this, but Ash doesn’t take it (which is slightly inexplicable). Plus, as we see in “Garden of Light,” it leaves Eiji unable to completely overcome his flaw (an inability to act/truly live) for seven years, so the story condemns it too.

And, of course, Ash also did not kill Shorter out of malice--he was forced into it, like he was forced into the life he had to live with Dino. It’s not the deaths of one of the people begging to be spared whom Ash killed for playing a role in killing Shorter, but Shorter’s death itself that brings about fear and mistrust in Lao. To have Ash’s death be a consequence for killing willingly (which he did plenty of), it should have been for one of those nameless people we got a brief shot of, instead of as a consequence for a murder Ash had no choice in and was a victim of almost as much as Shorter was. But that also wouldn’t work because a nameless death doesn’t quite suffice for offing your main character, so. Yeah. Ash’s death is not a narrative consequence for killing others; it’s expressly framed as a tragic and cruel result of his inability to forgive himself for specific acts that were not his fault.

Social Messages Part 1: LGBT relationships

While Banana Fish was written in the 1980s-90s (kind of a dire time for LGBT+ people in the United States with the AIDS crisis), the trope of “bury your gays” has received rightful criticism since, and the ending can definitely be seen as “bury your gays.” (A criticism that is not helped by what happens to the gay/bi character in Yasha.) In other words, while I think the themes, characters, and frankly issues of Banana Fish are generally timeless, the ending is the only part of the story that I don’t think ages well. As time goes by, it will probably get even more criticism because of current society finally moving towards being better in the portrayal of LGBT+ characters.

*Because I want to complain and explain why I really don’t consider anything post-GoL canon: the follow-up picture book “New York Sense” doesn’t help the “bury your gays” impression either: Sing and Akira are certainly intended to be parallels to Ash and Eiji as Akira is brought to the US by Ibe and interacts with gangster Sing in “Garden of Light,” and while such framing is very ambiguous/bordering on not being there in GoL the follow-ups absolutely paint a romantic framing to their interactions in GoL. They marry and raise a son, popping up in cameos in Yoshida’s other works. Hence it runs dangerously close to reading as the heterosexual couple introduced in the epilogue got the happy ending while the gay couple we spent 19 volumes with did not. Since Sing is also still heavily involved with the mafia in all of the follow-ups, this again contradicts narrative justifications for Ash’s death as karma.

While I very much like Akira’s character, her romance with Sing isn’t just uncomfortable because of the above issue--it’s also uncomfortable because she is 13 and he is 23 in GoL (though their relationship doesn’t have to be read as mutually romantic there, and I don’t read it that way) and according to “New York Sense,” they marry when she is 18 which... implies things that seems very, very out of character for Sing, the series’ moral compass, and dramatically contradicts the skeevy adults preying on kids theme. It can also raise some cringe-worthy questions about why it’s framed as okay for the heterosexual couple but negatively (as it should be) for the people--who are primarily men--who assault Ash (and there is noted to have been a woman who assaulted him in “Private Opinion”). Like with Yut-Lung’s death, I just... don’t accept this retconning as canon. It contradicts the themes of Banana Fish as a story so I don’t have to.*

Social Messages Part 2: Abuse Survivors

For people who have been through abuse similar to Ash’s, in which choices over basic things like life, death, and your own body are taken from you, it’s honestly cruel to show someone who has spent their entire life suffering just about to grasp happiness, and then they die. It is fully valid to find this completely distasteful, and I do too.

But for me at least, one aspect that circumvents... some of the distasteful implication that Ash really was broken by things he had no choice in is the fact that Ash triumphed over his abusers first. Yet of course, having him die afterwards still hurts people who read the story and see themselves in a character like Ash, as it can reinforce the idea that abuse defines your life.

I do wish (though I don’t think there’s a moral necessity) that more authors/creators would acknowledge that, in creating characters whom you in theory want people to relate to, see themselves in, root for, care about, you’re asking people to suffer with them as they suffer and if they die, grieve for them. Given the heaviness of Ash’s arc and the specific nature of his suffering (especially since it was horrifically emphasized in the story’s last arc with Foxx), the fact that Ash didn’t in the end overcome the message that he did not have value is going to be very painful for readers/viewers. (Lao missed his vital organs, so Ash really chose to die instead of getting help, because he chose to believe Blanca over Eiji, which... I’m not sure it quite works.) If you could have narratively had it end happily (and it absolutely could have, and apparently Yoshida’s editor told her not to end it with Ash’s death), there’s room to say that going with the tragic ending is hurtful and bordering on irresponsible.

Genre