#pétain

Text

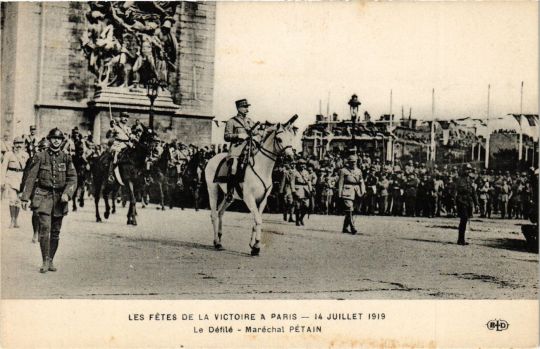

Marshal Pétain in Paris on the 1919 Victory Parade

French vintage postcard

#vintage#tarjeta#old#briefkaart#postcard#photography#postal#carte postale#parade#sepia#ephemera#the 1919 victory parade french#historic#victory#paris#french#ansichtskarte#marshal#postkarte#ptain#pétain#postkaart#photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#jérômeduveau#jeromeduveauindustrie#illustration volume#gif illustration#trombinoscope#total#nabila#deGaulle#Pasteur#Pétain

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Stroll down Broadway in New York City’s Financial District and you’ll see hundreds of black granite plaques honoring every ticker tape parade in city history. Named there are parade honorees like beloved 20th century icons Amelia Earhart and Nelson Mandela, along with some more ignominious figures, particularly Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain and Pierre Laval.

Pétain and Laval, leaders of the Nazi collaborationist Vichy France, were honored during parades in the 1930s, years before they enacted policies that removed Jews from civil service, seized Jewish property, and deported more than 65,000 Jews to Nazi camps. And yet, the commemorative plaques in New York were not installed until 2004. There are nearly a dozen streets in the US named after Pétain, who was originally honored as a World War I hero.

In 2018, the New York City Council voted against removing the Pétain and Laval plaques to avoid what they called “cultural amnesia.” Meanwhile, Canada renamed Mount Pétain in the Canadian Rockies last year, and France no longer has any memorials to either man.

Pétain and Laval are far from the only Nazi collaborators and fascists to be honored in the US, or abroad for that matter. In January 2021, an investigation by The Forward identified more than 1,500 statues and streets honoring Nazi collaborators around the world. In the US alone, there are at least 37 such monuments.

There are, of course, monuments, plaques, and statues to many other unsavory or disgraced figures in the US, from Confederate generals to colonialists and slave traders. In 2020, during the George Floyd protests, those statues became a focal point as activists either tore them down or worked to have them legally removed. Yet, in most cases, the public art commemorating fascists — and thus whitewashing fascist history — remain in place. And many, like the Pétain and Laval plaques, were installed in recent decades.

Understanding why can help make sense of far-right revisionism, which has lurked below the surface in the US for decades and recently exploded into public view.

More at the link.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pétain en het proces zonder einde

In een land als Frankrijk, waar de nationale geschiedenis van de afgelopen drie eeuwen vol is van snijdende gebeurtenissen, omwentelingen en bloed van slachtoffers, is de herinnering aan de periode van de Duitse bezetting van de jaren 1940 wat anders gestructureerd dan in een land als Nederland, waar sinds de slag bij Waterloo (1815) of eventueel nog de Belgische opstand van 1830 nauwelijks…

View On WordPress

#1940#Île d&039;Yeu#Céline#Chirac#collaboratie#De Gaulle#Emmanuel Berl#Frankrijk#Hitler#Holocaust#Julian Jackson#La Cagoule#Laval#Léon Blum#Mitterrand#Nazi-bezetting#Pétain#Pieter Geijl#Quisling#Ribbentrop#Robert Paxton#Seuil#Sigmaringen#Verdun#Vichy#Zemmour

0 notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Text

“If any of us thought we could do our fellow creatures good by committing or, more probably, condoning an evil act, would we do so? Would we even recognize the moment when it happened, or accept that it was evil? Most of us are wonderfully good at persuading ourselves that our actions are pure. Does treason actually exist or, as Talleyrand quipped, is it just a matter of dates? Worse, is it a process of human sacrifice, in which exposed individuals are singled out to pay for the sins of thousands—who escape punishment? Switch allegiance at the right moment, or die opportunely, and you may be spared centuries of shame. Live too long, or cling to the wrong raft and your name will be a byword and a hissing. I suspect that Talleyrand, living in a wittier and less dogmatic age, might have reflected that Marshal Philippe Pétain was just unfortunate in his timing.

From this perspective, Pétain’s mistake was to carry on living after the fall of his Vichy State during the last grisly months of the Third Reich. If he had managed to die (he was after all 88) then he would have escaped much humiliation. If he had been shot out of hand by French resisters, a lot of scores would have been neatly settled. (Winston Churchill thought this would have been a much better way of dealing with the actual Nazi leadership than the dubious Nuremberg trials with their Soviet prosecutor). But, as Julian Jackson recounts in his book about Pétain’s surrender, trial, condemnation, and lifelong imprisonment, the old soldier more or less sought out his fate. The Germans had carried him off to the Reich. But Pétain found his way back to France, so compelling De Gaulle and his provisional government to put him on trial for treason. To do so, it had to reopen the whole bitter period, in which many apart from Pétain had behaved weakly, or dishonorably, or just mistakenly. As the title of this book reminds us, France was on trial alongside Pétain.

(…)

The shepherd, the argument runs, is supposed to stay and tend his sheep when the danger is at its worst, not to flee abroad—even if he eventually returns triumphant. Did Pétain perhaps stand between the French people and the full wrath of their conquerors? He may have thought so, at least to begin with. And when he spoke of “collaboration” with Hitler, the word did not seem to mean what it later came to mean.

But, as it happened, Pétain did not stand between the French people and their Nazi occupiers. He became their all-too-willing servant. We now know beyond doubt that Marshal Pétain’s Vichy state enthusiastically offered collaboration to the Nazis, so much so that the Germans actually rebuffed it. It had even suggested its own persecution of the Jews, rather than reluctantly given in to German pressure. In 1972 an American historian, Robert Paxton, obtained German documents on the Occupation which left no doubt about this. Pétain’s supposed “National Revolution” closely collaborated with the fiends and demons of the Third Reich and vigorously urged on one of its ugliest policies. Anybody who has any serious interest in Pétain now knows all this.

But they did not know it when it mattered most, when Pétain and France were on trial in 1945, or for some time afterwards. In fact, Pétain died in custody in 1951 before the facts were wholly known. Jackson’s book on the French state’s 1945 prosecution of Pétain contains a lengthy passage on Paxton’s discoveries. But it rightly leaves them until long after this extraordinary process was over and the Marshal slept with his fathers. So Jackson is able to treat seriously several French citizens, lay jurors, journalists, politicians—and Pétain’s brilliant, dangerous and inconvenient lawyer, Jacques Isorni. All these were determined to give the old man some semblance of fairness, at a time when violent hysteria would have been quite possible instead. Remember, it was not long since the repellent and chaotic epuration (purge) of actual and alleged collaborators after the German defeat in which wild, violent street “justice” was imposed on some of those believed to have been too helpful or friendly to the occupying power, especially the public shaving of women’s heads, not a brave action whatever else it was. France’s Communists, in particular, were keen to condemn the conservative Catholic Pétain as a national traitor comparable to the reviled Marshal Bazaine of the Franco-Prussian war. They published propaganda showing him dangling at the end of a hangman’s rope and urged the imposition of the death penalty.

(…)

It was not just Denmark where this sort of thing happened. British sneering at the weakness and cowardice of continentals under the jackboot is also badly shown up by the curious, embarrassing and largely-forgotten German occupation of the British Channel Islands in 1940. “But what would you have done?” the islanders ask their mainland critics, to this day. The islands’ local authorities were cut off from the British constitution and government when Churchill brusquely abandoned them as indefensible after Dunkirk. Suddenly these largely conservative gentlemen, some nearly as elderly as Pétain, found themselves implementing the decrees of the Third Reich rather than those of His Majesty the King. They felt they had little choice but to work with the German occupiers. Where can a resistance movement hide on a tiny island?

But compromise leads to compromise and to worse compromise. Some of their leading officials ended up cooperating in terrible acts, such as the deportation of local Jews to Auschwitz. Those who survived this distressing period are understandably angry about criticism from safe mainlanders who never saw a German soldier on their streets. When the author Madeleine Bunting wrote a severe account of the islands’ subjugation, The Model Occupation, she met much resentment from those who had experienced it. But I wish this story was better known so that boastful and ignorant British people would stop mocking the supposedly cowardly French for their collaboration in the Vichy period. The fate of the islanders suggests that it would have been the same for the British, if Hitler had ever got ashore.

(…)

Despite the French Communists’ righteous wrath at Pétain, they had their own highly embarrassing secrets from the era. This is hugely significant because of the undoubted (and gravely mistaken) attraction of the Pétain regime for French conservatives and Catholics. His national motto of Travail, Famille, Patrie, replacing the Republican Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite, made it plain that this was not just a necessary co-operation with a new master, but an attempt to overturn many of the principles of the French Revolution. To this day, some figures on the political right in France seek to defend Pétain, the most recent being the failed presidential candidate Eric Zemmour, who most unwisely and inaccurately sought to defend Vichy’s policy, for supposedly saving French Jews by sacrificing recently arrived Jewish refugees to the Nazis. Why would anyone bother to do this? Could it be because of an actual lingering sympathy with Pétain’s social policies?

The Communist attempts at collaboration with the Germans were (like Vichy’s active anti-Jewish behavior) not widely known at the time of Pétain’s trial. Julian Jackson discussed the Communist approach to the German occupation authorities in another work on France’s occupation period France: The Dark Years 1940-44. For many years after the war the episode was little more than a bitter Trotskyist rumour, but it has now taken solid form in serious research. To even begin to comprehend it you must recall that in May 1940, as France’s democratic government collapsed and Nazi power swept into Paris, the Nazis and the Communists were allies against the democracies, thanks to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939, which would endure until June 1941 and was far more than a brief flirtation. The previous September, there had been a joint Wehrmacht and Red Army victory parade over Poland in the city of Brest-Litovsk (pictures still exist of German and Soviet officers happily communing as they take the salute). Not long afterward the two worst secret police forces in the world, Hitler’s Gestapo and Stalin’s NKVD, exchanged prisoners, as each wanted to get their hands on persons the other had arrested. Much of the fuel and material used in the German Blitzkrieg against the European democracies in May 1940 had come from or through the USSR.

The French Communist Party was therefore considered a pro-enemy body by the French state. It was banned and its daily newspaper L’Humanite shut down. The French Communists brushed aside rumors of their behavior for long after the war, and their considerable power and popularity in Gaullist France allowed them to get away with doing so. But scholarship has now caught up with them. Beyond doubt, French Communists went voluntarily to the Nazis and sought permission for the re-issue of their newspaper. Apparently the Comintern, then the central headquarters of all Communist Parties, was taken by surprise by the French defeat in 1940. It did not know how to respond. The leaders of French Communism had been dispersed by the proscription of their Party, and were in hiding or abroad. But some heavyweight commissars, Jacques Duclos, Jean Catelas, and Maurice Treand, wondered if the fall of the French state might be a chance to recover their organization’s lost influence. This was in the Leninist tradition of ruthlessness and of scorn for patriotism and other such bourgeois notions.

The negotiations involved the subtle French-speaking Otto Abetz, Germany’s future ambassador to Vichy France. Treand and Catelas promised, Jackson writes, that if allowed to reappear, the Communist daily would “pursue a policy of European pacification” and “denounce the activities of the agents of British imperialism.” Underground editions of the paper (secretly printed since September 1939) published three articles in the summer of 1940 praising fraternization between French workers and the Germans. Perhaps these were aimed at persuading the Germans to allow open publication. Who can now say?

As so often in history with things that nearly happened, it is like watching a ghost begin to appear, and then disappear again. There was surprising sympathy for collaboration on both sides in France. Some conservatives loathed England, hoped for a British surrender, and thought Hitler was better than socialism. Some Communists suspected that Hitler might be kinder to them than democracy had been. Only as the occupation hardened, and as the French Communist leader in exile, Maurice Thorez, reasserted control, did the Communists end the talks. They did so very shortly before the Germans also went off the idea, though it was a close-run thing. One Communist, Robert Foissin, was made an internal scapegoat by the Party—which belatedly realized how embarrassing the talks would one day become. But Duclos was too important for such treatment. He would live to be the Communist candidate for the Presidency of France in 1969. No wonder that in 1945 the Communists—now covered in glory because of their post-1941 Resistance role—wanted to draw eyes away from their own behavior in 1940, and concentrate instead on the wickedness of the Catholic, conservative Pétain.

(…)

In truth, France was on trial in 1945 more than Pétain. And France emerges from the trial with perhaps a little more credit than we give it. This at least was not a howling enraged tribunal, as the Communists might have desired, but a genuine attempt to apply due process and so to restore some sort of legitimate stability. De Gaulle’s view of the old man was that he was a living corpse who had died to all intents and purposes in 1924. Probably those in French politics who (perhaps too willingly) let him take responsibility for making peace with Germany had a similar view. He was a cypher, not a person. Those who seriously imagined that he was the head of a conservative national revolution were deluded at the time, and those in modern French politics who suggest the same are equally deceived, though it now seems fairly certain that the Marshal was, more often than not, conscious of what was going on around him and aware of what was done in his name. His reprieve from execution was not only a recognition that he was too old to face a firing squad. It was a humane compromise between the De Gaulle and Pétain factions which still haunt French public life in surprising ways. After all, the Socialist President Francois Mitterrand served and was honored by the Vichy regime, yet lived to prosper. The far more brutal fate of Pétain’s colleague Pierre Laval, shot after a brief and undignified hearing and a botched suicide, probably satisfied the general desire to erase the shame and discomfort of the collaboration years which Mauriac had identified. How pleased any reader of this book must be that he and his country did not undergo such misery. Do not be defeated in war. Defeat corrupts the defeated, and it is far harder than we think to stand above the grim process. Pray that it never happens to you.”

“One of the greatest challenges human beings face is how to tease apart a bad act from a good character — or, conversely, a toxic personality from the good and worthy things he created. How do we separate the long-time childhood friend from his insane Facebook polemics? The good neighbour from his bad politics?

“People are thoughtless all the time,” writes Alexandra Hudson in her new book, The Soul of Civility, while arguing that the best way to depolarise our society is to recognise that good people can have bad ideas. This idea is classically Christian, but also fundamentally American: even after the Civil War, a central tenet of Reconstruction was that those who fought for the Confederacy should be given grace for having chosen the wrong side. But that’s a principle it’s easier to hold to in the wake of victory than in the fog of war — or, as this past week’s events have reminded us, War Discourse.

The response from certain corners of the progressive Left to the stories coming out of Israel has been extraordinary. The silhouette of a paragliding Hamas militant has been adopted by groups ranging from Black Lives Matter to the Democratic Socialists of America — a graphic successor to that Che Guevara block print that used to hang on every dorm room wall. A crowd on the steps of the Sydney Opera House in Australia chanted “gas the Jews”. A cheer went up in Times Square at the news that 700 Israelis had been killed. And among the academic and media classes, a series of statements ran the gamut from half-hearted condemnations of the terrorist attacks to triumphant and bloodthirsty snarling.

“What did y’all think decolonization meant? vibes? papers? essays? losers,” wrote Najma Sharif, a writer for Soho House magazine and Teen Vogue. “Today should be a day of celebration for supporters of democracy and human rights worldwide,” tweeted Rivkah Brown of Novara Media. The language varied, but the sentiment was the same: this is good, actually, and seeing it should fill you with the same cathartic glee as any underdog story. Don’t you see? This isn’t terrorism; it is justice.

(…)

The war in Israel, and the one in Ukraine: it’s not hard to see how our distance from these events, combined with the immediacy of so much coverage and conversation about them, lends itself to the most grotesque kind of rubbernecking. It’s war as spectator sport; people haggle over the reports of Hamas beheading babies with the same energy as a group of armchair referees debating an off-side call.

Some people, anyway. The term “luxury beliefs” was coined to describe how privileged progressives like to traffic in this sort of unhinged extremist rhetoric. Partly, it’s a hazard of their utter insulation from ever having to experience the practical impact of the policies they advocate. Violence and chaos have a way of breaking through the barriers that separate the ivory tower-dwellers from the masses they condescend; one imagines the occupants of Versailles looked out their windows at the guillotine being constructed in the public square and, not understanding what lay in store, pronouncing the structure adorable.

But it’s also what happens when you succumb to the Manichean worldview that every conflict, every issue, boils down to a simple question of who is the more oppressed party. Whichever guy has more privilege, more power: this is your villain. In trying to topple him from his unearned position of influence, his victim can do no wrong. Hamas, composed as it is of Muslim people of colour, is merely punching (and raping, and kidnapping) up.

While the attacks on Israel have given rise to a particularly stomach-turning iteration of this rhetoric, we have seen it before. In 2020, as the US protests against police violence spiralled out of control, members of the laptop class could reliably be found posting that Martin Luther King Jr quote about riots being “the voice of the unheard” — always from the safety of their homes, in nice neighbourhoods, in coastal cities, where things were conspicuously not on fire. The people looting, rioting, and wreaking havoc were members of an oppressed class, and hence above reproach.

But the most absurd example of how true-life horrors become grist for the mill of perverse progressive fantasy popped up downstream of the “decolonisation” discourse. Every now and then, someone announces on the internet that they would begrudgingly allow themselves to be murdered if Native Americans decided to violently re-exert ownership over their ancestral lands. The authenticity of such sentiments is obviously belied by the fact that these same people could, if they wanted to, voluntarily renounce their power instead of waiting for some noble savage to take it by force. If you truly believed yourself to be a colonist, illegitimately squatting on someone else’s property, why would you waste time tweeting about it? Wouldn’t you just leave?

(…)

If civility demands that we hold people to account for the hatred they spew, it also rejects the notion that a person of an “oppressed” identity category should get a free pass to spew hatred. The bar for human decency, surely, does not shift depending on the colour of your skin or the arrangement of your genitals — and to insist on this, on one standard for all people, creates a clear path forward, which may be the best thing about civility as an ethos. It works on the assumption that, as bleak as things are now, there will be an “after” in which we forgive, even if we don’t forget.

(…)

As I left Hudson’s event on Tuesday night, I found the street closed off. Instead of cars, the pavement was occupied by hundreds of people holding signs and banners and flags: the remnants of what had been a massive rally in support of Israel. I would later learn that some people present were captured on camera wishing for the annihilation of Palestine; no one side, as it turns out, has a monopoly on hatred.

As I weaved through the crowd, Leonard Cohen’s “You Want it Darker” was playing through my headphones, a fitting meditation on war, death, and the cruelty we inflict on each other in the name of a just cause.

They’re lining up the prisoners

And the guards are taking aim

I struggle with some demons

They were middle-class and tame

I didn’t know I had permission

To murder and to maim

The chorus to this song is a Hebrew word, a line from the Torah. It’s what Abraham says, in response to God’s request that he sacrifice his son; it is also what we might say to each other, eventually, when civility or decency or whatever deity you believe in asks us to confront and forgive each other’s failings in this moment, the better to thrive in the moments we have left.

Hineni, hineni. I’m ready, I’m ready.”

#hitchens#peter hitchens#petain#pétain#marshall petain#vichy#germany#france#collaborators#collaboration#nazis#antisemitism#rosenfield#kat rosenfield#israel#palestine#gaza#hamas#woke#leftism#communists#french communists#molotov ribbentrop pact#leonard cohen#you wanted it darker

1 note

·

View note

Text

Le RN « héritier de Pétain » ?

Quand le pouvoir panique

Par Philippe Kerlouan

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#boulevard voltaire#Elisabeth Borne#Le RN « héritier de Pétain » ?#Observatoire du MENSONGE#Pétain#Philippe Kerlouan#Quand le pouvoir panique#Rassemblement National#RN

0 notes

Text

Israel is a democracy. It’s not even strictly a racial democracy despite the officially Jewish character of the state, since Arab citizens have voting rights and are represented in the same parliament as Jews. The Occupied Territories are not democratic obviously; I struggle to think of any colonial military occupation that is.

It’s also strange to me to smugly dismiss concerns over the Israeli political system, whatever we call it, becoming more authoritarian as silly and unimportant, and especially to act like this is the leftist pro-Palestinian angle. Use your heads.

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023's Best Books

I meant to do this a few days ago so there was more time before the holidays, but here's a quick list of the best books that I read that were released in 2023. Obviously, I didn't read every book that came out this year, and I'm only listing the best books I read that were actually released in the 2023 calendar year.

In my opinion, the two very best books released in 2023 were An Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. Ford by Richard Norton Smith (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO), and True West: Sam Shepard's Life, Work, and Times by Robert Greenfield (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO).

(The rest of this list is in no particular order)

President Garfield: From Radical to Unifier

C.W. Goodyear (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The World: A Family History of Humanity

Simon Sebag Montefiore (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

France On Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain

Julian Jackson (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Last Island: Discovery, Defiance, and the Most Elusive Tribe on Earth

Adam Goodheart (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

Emperor of Rome: Ruling the Ancient Roman World

Mary Beard (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

City of Echoes: A New History of Rome, Its Popes, and Its People

Jessica Wärnberg (BOOK | KINDLE)

We Are Your Soldiers: How Gamal Abdel Nasser Remade the Arab World

Alex Rowell (BOOK | KINDLE)

Edison's Ghosts: The Untold Weirdness of History's Greatest Geniuses

Katie Spalding (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

Waco Rising: David Koresh, the FBI, and the Birth of America's Modern Militias

Kevin Cook (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Summer of 1876: Outlaws, Lawmen, and Legends in the Season That Defined the American West

Chris Wimmer (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

King: A Life

Jonathan Eig (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

LBJ's America: The Life and Legacies of Lyndon Baines Johnson

Edited by Mark Atwood Lawrence and Mark K. Updegrove (BOOK | KINDLE)

Who Believes Is Not Alone: My Life Beside Benedict XVI

Georg Gänswein with Saverio Gaeta (BOOK | KINDLE)

Eighteen Days in October: The Yom Kippur War and How It Created the Modern Middle East

Uri Kaufman (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Rough Rider and the Professor: Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and the Friendship That Changed American History

Laurence Jurdem (BOOK | KINDLE)

White House Wild Child: How Alice Roosevelt Broke All the Rules and Won the Heart of America

Shelley Fraser Mickle (BOOK | KINDLE)

Romney: A Reckoning

McKay Coppins (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

Founding Partisans: Hamilton, Madison, Jefferson, Adams and the Brawling Birth of American Politics

H.W. Brands (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Earth Transformed: An Untold History

Peter Frankopan (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

LeBron

Jeff Benedict (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America

Abraham Riesman (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

The Fight of His Life: Inside Joe Biden's White House

Chris Whipple (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

#Books#Book Suggestions#Book Recommendations#Best Books of 2023#Best of 2023#An Ordinary Man#President Ford#Richard Norton Smith#True West#Sam Shepard#Robert Greenfield#President Garfield#C.W. Goodyear#The World#Simon Sebag Montefiore#France On Trial#Marshal Pétain#Julian Jackson#The Last Island#Adam Goodheart#Emperor of Rome#Mary Beard#City of Echoes#Jessica Wärnberg#We Are Your Soldiers#Gamel Abdel Nasser#Alex Rowell#Edison's Ghosts#Katie Spalding#Waco Rising

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

How come Pierre Laval was executed for his part in the German Occupation of France but not Philippe Pétain?

Pétain was in advanced age, by the time of his trial, he was almost 90 years old, and so according to the court transcripts, the court requested that the death sentence not be carried out, partially due to his age and partially due to his World War I service record.

Thanks for the question, Anon.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Douce France

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marshal Pétain on the 1919 Victory Parade in Paris

French vintage postcard

#parade#historic#victory#photo#briefkaart#vintage#marshal#sepia#photography#the 1919 victory parade#carte postale#paris#postcard#postkarte#postal#tarjeta#ansichtskarte#french#old#pétain#ephemera#postkaart#ptain

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Very good article in Humanities, the magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities, by Barbara Will that looks at Getrude Stein’s enthusiastic support of Vichy collaborationist Philippe Pétain and his government both during and after the Nazi occupation of France. Stein exhibiting a combination of self-interested opportunism and genuine reactionary opposition to modernity—paradoxical for the arch-modernist.

“For Stein, Pétain’s National Revolution offered a blueprint for a new kind of revolution in the United States, one that would negate the decadence of the modern era and bring America back to its eighteenth-century values.”

#gertrude stein#modernism#reactionary#barbara will#philippe pétain#vichy france#wwii#nazi collaborationist#neh

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

finished an eight thousand word essay on french society and how it dealt with the legacy of the vichy regime and realized nobody can make up their damn mind and most problems can be traced back to de gaulle.

#that and discussions on the holocaust have just completely clogged up every discussion after 1985#or its monkey journalists making bad historical allegories 24/7 about how their rival is literally pétain its just like laval is back bros#discourse should have just been frozen with mitterand#there was no need for anything after 1980#degaulle was on some konrad adenaeur type shit#the fuck were you doing giving papon the légion d'honneur#for massacring like 300 algerians twice in paris?#what algeria does to a mf...#txt

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

« En 2019, la France a prononcé 122 839 obligations de quitter le territoire français. Sauf que, seulement 18 906 ont quitté le territoire de manière forcée, faute d’application de l’obligation1. En 2019, les demandes d’asile s’élevaient à 138 420 (ministère de l’Intérieur), provenant de 139 pays différents dont 46 838 satisfaites (réfugiés, protection subsidiaire, apatrides) soit 38 %.

En 2017, Ahmed Hanachi, un Tunisien sans-papiers en situation illégale, est arrêté pour vol à l’étalage chez C&A, à Lyon… Faute de place en centre de rétention administratif, il est relâché alors que le sous-préfet de permanence ce week-end-là aurait dû signer une obligation de quitter le territoire. Moins de 48 heures plus tard, cet homme tue en poignardant deux jeunes femmes à la gare Saint-Charles à Marseille.

Henri-Michel Comet, le préfet du Rhône limogé, l’a dit lors de son discours d’adieu : « les injonctions ne sont pas toujours cohérentes » et « nos ennemis se repaissent des fragilités de notre démocratie ».

Extrait de

Le vrai état de la France

Agnès Verdier-Molinié

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

remember what i told you about the joan of arc statue by my school well it was made in 1942. by the collaborationist state. and no one thought it would be a good idea to take it down or at the very least offer some context

5 notes

·

View notes