#particularly in relation to levels of nakedness

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Someone reblogged this and given we are in a very similar predicament again it seemed very apt

Also using my previous tags as they are also extremely relevant...

Dear Mr Evans

Please find within a formal letter of complaint regarding your non compliance with specific terms in your recently signed contract.

Specifically, the women of tumblr would like to express their concern that they are running extremely low on HNW content and are even having to resort to duplicating previously used content.

They are also suffering from a near complete drought of new work, new photo content and well, frankly, new you.

We hereby demand that you engage in some new projects really fucking soon, preferably with the aforementioned contractually agreed levels of nakedness.

And yes we mean any project..

Thx babe

Love tumblr

#shaun evans#itv endeavour#endeavour morse#I hate to get formal about it#but we do have contractual commitments agreed#and you really need to comply#particularly in relation to levels of nakedness#because we’re very low on content#even though you spent quite a lot of your early career quite naked#for which we are extremely grateful#but most of us find you hotter now#than bb shaun#and so we need new content#asap#to be honest ANY fucking content#but preferably with some nakedness#ideally not as a dirty:hot psycho#pretty please#thx babe#hot damn evans

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something that's still a bit sideways about my sexuality, despite not feeling remotely asexual when my testosterone is working in my body like it should, is that I often have trouble understanding who I'm attracted to. I guess, on an aesthetic level? Funny thing with having wonky vision and being bad at retaining people's faces is that my in-person attraction is not often related to someone's looks. Or at least it's not their face.

It's usually a mix of vibes and body type. But even then it's like... I don't have much in the way of depth perception; I really can't estimate anyone's height; and my sense of 3D space in general is kind of not there. So even with body type, sometimes I'm not even aware what specifically I'm finding attractive. If my eyes are particularly tired that day, people in person sometimes look like a weird mess to me. I think it's usually why (that plus the autism) I tend to see people in fragments, and highlight those fragments as being my understanding of someone, and how I typically base my attraction on someone. Eyes, smile, hands, scars, tattoos. Those are the things I notice first with people. And that's how people tend to exist in my head.

Gonna shove my further musings about attraction below the cut.

I think dating apps are contributing to my growing confusion into who I find attractive. Because now I'm basing it completely on someone's face, when faces, specifically in person, and especially when someone is taller than me, aren't something I really focus on (literally, if they're tallet than me). Body type, too. That's hard to tell from a photo when I don't really have the mental ability to picture something in 3D from a 2D photo. Not that I'm particularly picky in any sense? It's just confusing.

Some people I'm immediately like, 😍😍😍 when I see them, which is giving me a better sense of what my type is. And sometimes my only clue is noticing I'm getting turned on lmao. Like I skip straight from seeing their aesthetic attraction to, "oh it'd be hot if they fuck me." and sometimes in that case I never actually get a solid sense if I find them attractive (aesthetically) or not. I mean I must be, it's just skipping the conscious level and going straight to arousal??

In person, I pretty much check out everyone. Seeing people in fragments means it's really easy to see something I find attractive. Honestly it's rare I find someone unattractive.

But now basing everything on someone's face, I kind of have to mentally filter them through people I've met in person to determine if I'll find them actively attractive or not. Which makes me feel kind of guilty? Because sometimes I discover I feel quite neutral towards them in person. Not that it tends to be a problem for me, esp considering I spent a long time on the ace spectrum. And sometimes the emotional click is so strong, I stay pretty unaware of what they look like because everything about them turns me on.

Honestly, there's been only one person I went on a date with who I found actively unattractive, and I still feel very mixed up about that. Finding people actively arousing is new, but that came quickly with the discovery that I find pretty much everyone hot. So finding someome *un*attractive after experiencing that as my new normal for 4 years was kind of unnerving in a way I don't really know how to explain.

As a sidebar, it's also why I like sending/receiving nudes. Nakedness is my best way of how I get a sense of what someone looks like--I spent a long time in my teen years drawing naked people and somehow it gave me a pretty good sense of anatomy. Which somehow becomes null when I see people in clothes.

It's complicated.

0 notes

Text

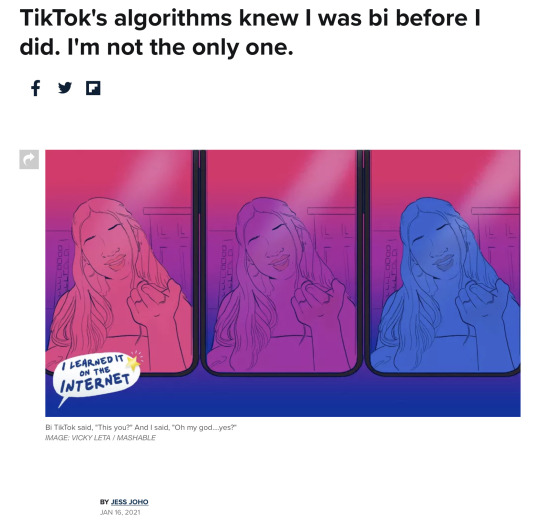

Here's a shortlist of those who realized that I — a cis woman who'd identified as heterosexual for decades of life — was in fact actually bi, long before I realized it myself recently: my sister, all my friends, my boyfriend, and the TikTok algorithm.

On TikTok, the relationship between user and algorithm is uniquely (even sometimes uncannily) intimate. An app which seemingly contains as many multitudes of life experiences and niche communities as there are people in the world, we all start in the lowest common denominator of TikTok. Straight TikTok (as it's popularly dubbed) initially bombards your For You Page with the silly pet videos and viral teen dances that folks who don't use TikTok like to condescendingly reduce it to.

Quickly, though, TikTok begins reading your soul like some sort of divine digital oracle, prying open layers of your being never before known to your own conscious mind. The more you use it, the more tailored its content becomes to your deepest specificities, to the point where you get stuff that's so relatable that it can feel like a personal attack (in the best way) or (more dangerously) even a harmful trigger from lifelong traumas.

For example: I don't know what dark magic (read: privacy violations) immediately clued TikTok into the fact that I was half-Brazilian, but within days of first using it, Straight TikTok gave way to at first Portuguese-speaking then broader Latin TikTok. Feeling oddly seen (being white-passing and mostly American-raised, my Brazilian identity isn't often validated), I was liberal with the likes, knowing that engagement was the surefire way to go deeper down this identity-affirming corner of the social app.

TikTok made lots of assumptions from there, throwing me right down the boundless, beautiful, and oddest multiplicities of Alt TikTok, a counter to Straight TikTok's milquetoast mainstreamness.

Home to a wide spectrum of marginalized groups, I was giving out likes on my FYP like Oprah, smashing that heart button on every type of video: from TikTokers with disabilities, Black and Indigenous creators, political activists, body-stigma-busting fat women, and every glittering shade of the LGBTQ cornucopia. The faves were genuine, but also a way to support and help offset what I knew about the discriminatory biases in TikTok's algorithm.

My diverse range of likes started to get more specific by the minute, though. I wasn't just on general Black TikTok anymore, but Alt Cottagecore Middle-Class Black Girl TikTok (an actual label one creator gave her page's vibes). Then it was Queer Latina Roller Skating Girl TikTok, Women With Non-Hyperactive ADHD TikTok, and then a double whammy of Women Loving Women (WLW) TikTok alternating between beautiful lesbian couples and baby bisexuals.

Looking back at my history of likes, the transition from queer “ally” to “salivating simp” is almost imperceptible.

There was no one precise "aha" moment. I started getting "put a finger down" challenges that wouldn't reveal what you were putting a finger down for until the end. Then, 9-fingers deep (winkwink), I'd be congratulated for being 100% bisexual. Somewhere along the path of getting served multiple WLW Disney cosplays in a single day and even dom lesbian KinkTok roleplay — or whatever the fuck Bisexual Pirate TikTok is — deductive reasoning kind of spoke for itself.

But I will never forget the one video that was such a heat-seeking missile of a targeted attack that I was moved to finally text it to my group chat of WLW friends with a, "Wait, am I bi?" To which the overwhelming consensus was, "Magic 8 Ball says, 'Highly Likely.'"

Serendipitously posted during Pride Month, the video shows a girl shaking her head at the caption above her head, calling out confused and/or closeted queers who say shit like, "I think everyone is a LITTLE bisexual," to the tune of "Closer" by The Chainsmokers. When the lyrics land on the word "you," she points straight at the screen — at me — her finger and inquisitive look piercing my hopelessly bisexual soul like Cupid's goddamn arrow.

Oh no, the voice inside my head said, I have just been mercilessly perceived.

As someone who had, in fact, done feminist studies at a tiny liberal arts college with a gender gap of about 70 percent women, I'd of course dabbled. I've always been quick to bring up the Kinsey scale, to champion a true spectrum of sexuality, and to even declare (on multiple occasions) that I was, "straight, but would totally fuck that girl!"

Oh no, the voice inside my head returned, I've literally just been using extra words to say I was bi.

After consulting the expertise of my WLW friend group (whose mere existence, in retrospect, also should've clued me in on the flashing neon pink, purple, and blue flag of my raging bisexuality), I ran to my boyfriend to inform him of the "news."

"Yeah, baby, I know. We all know," he said kindly.

"How?!" I demanded.

Well for one, he pointed out, every time we came across a video of a hot girl while scrolling TikTok together, I'd without fail watch the whole way through, often more than once, regardless of content. (Apparently, straight girls do not tend to do this?) For another, I always breathlessly pointed out when we'd pass by a woman I found beautiful, often finding a way to send a compliment her way. ("I'm just a flirt!" I used to rationalize with a hand wave, "Obvs, I'm not actually sexually attracted to them!") Then, I guess, there were the TED Talk-like rants I'd subject him to about the thinly veiled queer relationship in Adventure Time between Princess Bubblegum and Marcelyne the Vampire Queen — which the cowards at Cartoon Network forced creators to keep as subtext!

And, well, when you lay it all out like that...

But my TikTok-fueled bisexual awakening might actually speak less to the omnipotence of the app's algorithm, and more to how heteronormativity is truly one helluva drug.

Sure, TikTok bombarded me with the thirst traps of my exact type of domineering masc lady queers, who reduced me to a puddle of drool I could no longer deny. But I also recalled a pivotal moment in college when I briefly questioned my heterosexuality, only to have a lesbian friend roll her eyes and chastise me for being one of those straight girls who leads Actual Queer Women on. I figured she must know better. So I never pursued any of my lady crushes in college, which meant I never experimented much sexually, which made me conclude that I couldn't call myself bisexual if I'd never had actual sex with a woman. I also didn't really enjoy lesbian porn much, though the fact that I'd often find myself fixating on the woman during heterosexual porn should've clued me into that probably coming more from how mainstream lesbian porn is designed for straight men.

The ubiquity of heterormativity, even when unwittingly perpetrated by members of the queer community, is such an effective self-sustaining cycle. Aside from being met with queer-gating (something I've since learned bi folks often experience), I had a hard time identifying my attraction to women as genuine attraction, simply because it felt different to how I was attracted to men.

Heteronormativity is truly one helluva drug.

So much of women's sexuality — of my sexuality — can feel defined by that carnivorous kind of validation you get from men. I met no societal resistance in fully embodying and exploring my desire for men, either (which, to be clear, was and is insatiable slut levels of wanting that peen.) But in retrospect, I wonder how many men I slept with not because I was truly attracted to them, but because I got off on how much they wanted me.

My attraction to women comes with a different texture of eroticism. With women (and bare with a baby bi, here), the attraction feels more shared, more mutual, more tender rather than possessive. It's no less raw or hot or all-consuming, don't get me wrong. But for me at least, it comes more from a place of equality rather than just power play. I love the way women seem to see right through me, to know me, without us really needing to say a word.

I am still, as it turns out, a sexual submissive through-and-through, regardless of what gender my would-be partner is. But, ignorantly and unknowingly, I'd been limiting my concept of who could embody dominant sexual personas to cis men. But when TikTok sent me down that glorious rabbit hole of masc women (who know exactly what they're doing, btw), I realized my attraction was not to men, but a certain type of masculinity. It didn't matter which body or genitalia that presentation came with.

There is something about TikTok that feels particularly suited to these journeys of sexual self-discovery and, in the case of women loving women, I don't think it's just the prescient algorithm. The short-form video format lends itself to lightning bolt-like jolts of soul-bearing nakedness, with the POV camera angles bucking conventions of the male gaze, which entrenches the language of film and TV in heterosexual male desire.

In fairness to me, I'm far from the only one who missed their inner gay for a long time — only to have her pop out like a queer jack-in-the-box throughout a near year-long quarantine that led many of us to join TikTok. There was the baby bi mom, and scores of others who no longer had to publicly perform their heterosexuality during lockdown — only to realize that, hey, maybe I'm not heterosexual at all?

Flooded with video after video affirming my suspicions, reflecting my exact experiences as they happened to others, the change in my sexual identity was so normalized on TikTok that I didn't even feel like I needed to formally "come out." I thought this safe home I'd found to foster my baby bisexuality online would extend into the real world.

But I was in for a rude awakening.

Testing out my bisexuality on other platforms, casually referring to it on Twitter, posting pictures of myself decked out in a rainbow skate outfit (which I bought before realizing I was queer), I received nothing but unquestioning support and validation. Eventually, I realized I should probably let some members of my family know before they learned through one of these posts, though.

Daunted by the idea of trying to tell my Latina Catholic mother and Swiss Army veteran father (who's had a crass running joke about me being a "lesbian" ever since I first declared myself a feminist at age 12), I chose the sibling closest to me. Seeing as how gender studies was one of her majors in college too, I thought it was a shoo-in. I sent an off-handed, joke-y but serious, "btw I'm bi now!" text, believing that's all that would be needed to receive the same nonchalant acceptance I found online.

It was not.

I didn't receive a response for two days. Hurt and panicked by what was potentially my first mild experience of homophobia, I called them out. They responded by insisting we need to have a phone call for such "serious" conversations. As I calmly tried to express my hurt on said call, I was told my text had been enough to make this sibling worry about my mental wellbeing. They said I should be more understanding of why it'd be hard for them to (and I'm paraphrasing) "think you were one way for twenty-eight years" before having to contend with me deciding I was now "something else."

But I wasn't "something else," I tried to explain, voice shaking. I hadn't knowingly been deceiving or hiding this part of me. I'd simply discovered a more appropriate label. But it was like we were speaking different languages. Other family members were more accepting, thankfully. There are many ways I'm exceptionally lucky, my IRL environment as supportive as Baby Bi TikTok. Namely, I'm in a loving relationship with a man who never once mistook any of it as a threat, instead giving me all the space in the world to understand this new facet of my sexuality.

I don't have it all figured out yet. But at least when someone asks if I listen to Girl in Red on social media, I know to answer with a resounding, "Yes," even though I've never listened to a single one of her songs. And for now, that's enough.

#tiktok#queer education#bisexual education#queer nation#bisexual nation#bisexuality#lgbtq community#bi#lgbtq#support bisexuality#bisexuality is valid#lgbtq pride#bi tumblr#pride#bi pride#bisexual#bisexual community#support bisexual#bisexual women#bisexual people#bisexual youth#bisexual activist#coming out bisexual#bicurious#bicuriosity#bi positivity#bisexual info#bi+

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

6/24

This film really surprised me in many ways. For one, I am truly not a fan of this particular time period when it comes to films. Secondly, the film starts off slow and a bit dreary. Even with these couple of details that don’t fit my taste, I truly enjoyed the realness and the intimacy of the film.

There were a few scenes that involved nudity; however, there was a lack of the male gaze in those scenes. The first nude scene with Marianne didn’t appear to focus on her naked body and she appeared as more of a silhouette in the shot. Heloise appeared partially naked in a shot, while Marianne was painting her portrait, yet I got the feeling that her nakedness was the innocent vulnerability that she shared with Marianne. Her naked breast did not even phase me as a sexual part of the scene.

Someone mentioned in class that the removal of Heloise’s and Marianne’s scarves before sharing a kiss was a significant scene for them and showed an important example of consent. I feel as though this is an important aspect in the film because it displays the best example of respect. Both characters truly respect and care for each other. Another example of this care is when Marianne comes clean to Heloise and tells her that she was hired to paint her portrait—against her will. Typically, in this type of situation involving deceit, there’s an over-dramatic blow up that occurs. Instead, the ‘coming clean’ seemed to bring the two women closer together.

The Jenny Kitzinger and Celia Kitzinger reading was relatable to this film because of the realness of the two main characters—Marianne and Heloise. It also helps that this film was directed by a female director. In the reading, lesbians are particularly dangerous and highly sexualized in films; however, in Portrait of a Lady on Fire, this is not the case. There is a complete lack of the male gaze, there is more vulnerability and there is a higher level of respect between the women.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

**Research: Robert Gober / The Body in Pain by Elaine Scarry

Anti mentioned Robert Gober to me in relation to my wax cast ideas due to his explorations of the body and objects as fragment. Gober’s practice relates greatly to multiple areas of my research, particularly the abject, the uncanny and object/material theory. Gober’s practice explores objects as personified beings, his sculptures encouraging us to view them as subjects rather than objects. This notion relates to an area of research divulged within my dissertation, indeed a key underpinning to my area of practice. In the book ‘The Object’ by Antony Hudek (2014), the author explains that “objects define us because they come first, by commanding our attention, even our respect; they exist before us, possibly without us” (p.15).

Untitled (wax leg), 1989-90.

Untitled, 1984.

Similarly to Duchamp, Gober utilises domestic, everyday objects, however choosing to cast them rather than exhibiting the original objects. Hudek explains that “transforming the Duchampian readymade into something dubious and obsolete was a widespread preoccupation in the 1960s and 70s, as the post-war euphoria at the potentially infinite multiplication of consumable objects turned into doubt” (p.20). Although Gober mainly created work during the 1980s, it would suggest that his practice evolved as a result of the increasing popularity in utilising domestic objects similarly to that of Duchamp throughout the 20th century. ‘While thumbing his nose at the art world was great fun, the Bicycle Wheel was also a catalyst for new ideas and for re-thinking entrenched positions. In this one work he not only re-defined the activity of the artist and re-imagined the nature of a work of art in the 20th century, but he also re-interpreted the role of the spectator’ (Snell, 2018). Gober’s concepts span sexuality, religion, and politics; these concepts touched upon incredibly minimally through his use of fragmentation and disparate, simple object sculptures.

For me, Gober’s work spoke of something more deeply set in the experience of the body in pain. I particularly drew this conclusion from his wax casts of fragmented body parts, prompting me to reconsider my readings into ‘the body as fragment’ by Linda Nochlin. I thought about how viewing the body in a fragmented and abject sense created feelings of uneasiness and how this relates to the experience of pain and trauma; particularly when trying to gauge an understanding of another person’s experience of trauma. It is a process of attempting to share and embody trauma through the means of materialism and externalising what exists within that often instils a sense of uncomfortableness in others. I have often found this to be the case in my own practice due to the sheer vulnerability and embodiment of the internal that characterises it.

I had heard of the book ‘The Body in Pain’ by Elaine Scarry in a lecture by Doris Salcedo whilst researching last year and had been meaning to read it since then as the ideas and concepts resonated with me. Whilst on this train of thought, I decided that now would be a good time to make some headway with this book. It turned out to be a fascinating read and I am only part of the way through. Not only did it help to contextualise my own ideas about the body as fragment in relation to Gober’s work and beyond, but it also brought new ideas about breaking down the process of trauma to light. My key notes from the text are below:

The Body in Pain by Elaine Scarry

Chapter 3: Pain and Imagining

Page 161-162:

The object is an extension of, an expression of, the state. E.g. rain = longing, berries = hunger, night = fear. However nothing expresses the physical pain. Therefore, pain becomes something that must be materialised by the individual. In art terms therefore, subconscious processing of trauma through material output becomes the object associated with pain.

Page 163:

“As an embodied imaginer capable of picturing, making present an absent friend, that same imaginer is also capable of inventing both the idea and the materialised form. This demonstrates a mechanism for transforming the condition of absence into presence.”

Page 164:

Physical pain is an intentional state without an intentional object; imagining is an intentional object without an experienceable intentional state. Thus is may be that in some peculiar way it is appropriate to think of pain as the imagination’s intentional state, and to identity the imagination as pain’s intentional object. In isolation, pain ‘intends’ nothing’ it is wholly passive; it is ‘suffered’ rather than willed or directed. To be more precise, one can say that pain only becomes an intentional state once it is brought into relation with the objectifying power of the imagination: through that relation, pain will be transformed from a wholly passive and helpless occurrence into a self-modifying and self-eliminating one.

Physical pain and imagining could belong to one another as each other’s missing intentional counterpart.

Non-object transferred into object through a process of imagining, feeling and actioning.

Chapter 5: The Interior Structure of the Artefact

Page 282:

The womb is materialised as dwelling-places and shelters.

The printing press, the institutionalised convention of written history, photographs, libraries, films, tape recordings and Xerox machines are all materialisations of the embodied capacity for memory. They together make a relatively ahistorical creature into an individual one, one whose memory extends far back beyond the opening of its own individual lived experience, one who anticipates being remembered beyond the close of its own individual lived experience, and one who accomplishes all this without elevating each day its awakened brain to rehearsals and recitations of all information it needs to keep available to itself.

Page 284:

The human being has an outside surface and an inside surface, and creating may be expressed as a reversing of these two bodily linings. There exists both verbal artefacts (e.g. the scriptures) and material artefacts (e.g. the altar) that objectify the act of believing, imaging, or creating as a sometimes graphically represented turning of the body inside-out. But what is expressed in terms of body part it, as those cited contexts themselves make clear, more accurately formulated as the endowing of interior sensory events with a metaphysical referent. The interchange of inside and outside surfaces requires not the literal reversal of bodily linings but the making of what is originally interior and private into something exterior and shareable, and conversely, the reabsorption of what is now exterior and shareable into the intimate recesses of individual consciousness.

Page 285:

The reversal of inside and outside surfaces ultimately suggests that by transporting the external object world into the sentient interior, that interior gains some small share of the blissful immunity of intert inanimate object hood; and conversely, by transporting pain out onto the external world, that external environment is deprived of its immunity to, unmindfulness of, and indifference toward the problems of sentience.

Page 286:

The habit of poets and ancient dreamers to project their own aliveness onto non alive things itself suffuses that it is the basic work of creation to bring about this very projection of aliveness; in other words, while the poet pretends or wishes that the inert external external world had his or her own capacity for sentient awareness, civilisation works to make this so.

Page 288:

A chair, as though it were itself put in pain, as though it knew from the inside the problem of body weight, will only then accommodate and eliminate the problem. A woven blanket or solid wall internalise within their design the recognition of the instability of body temperature and the precariousness of nakedness, and only by absorbing the knowledge of these conditions into themselves (by, as it were, being themselves subject to these forms of distress), absorb them out of the human body.

Page 289-290 - A material or verbal artefact is not an alive, sentient, percipient creature, and thus can neither itself experience discomfort nor recognise discomfort in others. But though it cannot be sentiently aware of pain, it is in the essential fact of itself the objectification of that awareness; itself incapable of the act of perceiving, its design, its structure, is the structure of a perception. So, for example, the chair can - if projection is being formulated in terms of body part - be recognised as mimetic of the spine; it can instead be recognised as mimetic of body weight; and it can finally, and most accurately, be recognised as mimetic of sentient awareness. If one human acknowledges another human in pain and wishes it gone, this is an invisible, complex percipient event happening somewhere between the eyes and the brain and engaging the entire psyche. If this could process of imaging unreality and acknowledging the reality of pain could be made visible and lifted out of the body, endowed with an external shape - that shape would be the shape of a chair (or, depending on the circumstance, a lightbulb, a coat, an ingestible form of willow bark). The shape of a chair is a shape of perceived-pain-wished-gone. The chair is therefore the materialised structure of a perception; it is sentient awareness materialised into a freestanding design.

Page 290-291 - Two levels of projection are transformations: first from an invisible aspect of consciousness to a visible but disappearing action ; second, from a disappearing action to an enduring material form. Thus in work, a perception is danced; in the chair, a danced-perception is sculpted. Each stage of transformation sustains and amplifies the artifice that was present at the beginning. Even in the interior of consciousness, pain is ‘remade’ by being wished away; in the external action, the private wish is made sharable; finally in the artefact, the shared wish comes true. For it the chair is a ‘successful’ object, it will relieve her of the distress of her weight far better than did the dance.

References:

Hudek, A., (2014). Documents of Contemporary Art: The Object. London: Whitechapel Gallery, The MIT Press. pp. 14, 15, 20, 22, 23, 24, 30, 32, 40, 42, 43, 94, 97.

Matthew Marks, (no date). Robert Gober. [Online]. Available at https://matthewmarks.com/artists/robert-gober. [Accessed on 28/11/2020].

Scarry, E., (1985). The body in pain: The making and unmaking of the world. New York.

Snell, T., (2018). Here’s looking at: Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel 1913. The Conversation. [Online]. Available at http://theconversation.com/heres-looking-at-marcel-duchamps-bicycle-wheel-1913-98846. [Accessed on 26/11/2020].

Vischer, T., and (Basel), S., (2007). Robert Gober: Sculptures and Installations 1979-2007. Steidl. Available at http://www.schaulager.org/en/file/195/cb6849b2/rg_CatalogueIntroduction_E.pdf.

0 notes

Note

All of them :P

1:Full name

Alexander David Walter, but please call me Pete

2:Age

18

3:3 Fears

I’ll die early and break my promise to my best fried to not die for “many, many years to come,” getting anything- even water- in my eyes or close to my eyes, my parents finding out about my beliefs and kicking me out

4:3 things I love

My best friend, my best friend, and, um, my best friend

My best friend, cuddling/hugging, and being cold

5:4 turns on

Uhh, I only get “turned on” if I haven’t ‘done the deed’ in a while, but I don’t really have any stimuli that can sexually “turn me on” consistently.

6:4 turns off

Honestly? Nakedness. And also…… gosh, I don’t know. My lack of sexual attraction is not helping me come up with an answer…

7:My best friend

My best friend is Rachel and she is a first violin in the top orchestra at my former high school and we met through a school club and we had lunch every day almost all of my senior year and she is the best and I love her

8:Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation? Asexual, or on the Ace spectrum at least.

9:My best first date

Uh, what in my life classifies as a date? I’m so ??? on everything, but….. I’m going to claim that I haven’t had a true first date with anybody. However, I did go to dinner with someone (who was forced to go with me by her parents 1/10 would not recommend at all) before the homecoming dance in my freshman year and the pasta wasn’t terrible and we did have some moments of sustained conversation…

10:How tall am I

6′ 1″ (186 cm)

11:What do I miss

My best friend, getting to eat lunch with my best friend and another of my closest friends every day at school, the high school clubs and band, marching band, my AP Gov class, playing games with people

12:What time were I born

11:55 am on a Monday

13:Favourite color

Onyx, cerulean/cobalt

14:Do I have a crush

I wouldn’t classify anything I have as a crush right now, neither romantically nor platonically

15:Favourite quote

“You’ve got opinions, manWe’re all entitled to ‘emBut I never asked

So let me thank you for your timeAnd try to not waste any more of mineGet out of here fast”

from the song “King of Anything” by Sara Bareilles

16:Favourite place

Next to my best friend. Otherwise, the city where I grew up.

17:Favourite food

A cheeseburger with an egg on it. A bun, a burger patty, american cheese (or cheddar), bacon, an over-easy egg, and lettuce. Plus, I love biting into the burger and then letting the runny yolk drip onto the fries and if I’m lucky, some cheese will also drip onto the fries over time and so I can have cheesy, egg-y fries and they just taste so good

18:Do I use sarcasm

Yeah, I would say so.

19:What am I listening to right now

The ringing in my ears from my hearing damage

20:First thing I notice in new person

Their faces (more specifically, their lips)

21:Shoe size

Men’s 11-12 Wide

22:Eye color

Blue most of the time

23:Hair color

Dirty Blond

24:Favourite style of clothing

Whatever is clean, or if not, whatever I can slip on in a few seconds. Often a T-shirt and basketball shorts

25:Kiss someone that starts with the letter “R”?

Yeah

27:Meaning behind my URL

I play the tuba and wanted to join the Jesus SquadTM

28:Kiss someone that starts with the letter “M”?

No

29:Favourite song

“She Used To Be Mine” by Sara Bareilles

30:Favourite band

Panic! at the Disco

31:How I feel right now

Unstimulated

32:Someone I love

My best friend

33:My current relationship status

Content

34:My relationship with my parents

I’m not all that open with them and don’t feel that it’s worth it at this point to let them into my personal life

35:Favourite holiday

Christmas, honestly. It’s one of the two times I get to see all of my mom’s family, guaranteed, and it’s much better than Thanksgiving

36:Tattoos and piercing i have

None, and I don’t want any either

37:Tattoos and piercing i want

Oh. Well, what I typed five seconds ago still stands, I don’t want any.

38:The reason I joined Tumblr

Uhh, I’m not going to say… Let’s say the puns, yeah, the puns…

39:Do I and my last ex hate each other?

She should hate me, but I don’t hate her. I just feel incredibly guilty…

40:Do I ever get “good morning” or “good night ” texts?

My best friend and I try to say good night every night.

41:Have I ever kissed the last person you texted?

No

42:When did I last hold hands?

Sunday

43:How long does it take me to get ready in the morning?

However long it takes to find clothes and get up

44:Have You shaved your legs in the past three days?

It’s been a good two years or so I think, but I want to do it again

45:Where am I right now?

My living room

46:If I were drunk & can’t stand, who’s taking care of me?

I wouldn’t be drunk, alcohol in no way tastes anywhere close to as good as root beer does

47:Do I like my music loud or at a reasonable level?

However loud it needs to be for me to clearly hear it, and loud if I’m trying to drown out noises I don’t want to hear (the television about once a week average)

48:Do I live with my Mom and Dad?

For 11 more days and then whenever I’m not at college, and we’ll see after I graduate

49:Am I excited for anything?

I’m going to my best friend’s first cross country meet of the season today and so I get to see my best friend today!!!!!

50:Do I have someone of the opposite sex I can tell everything to?

My best friend

51:How often do I wear a fake smile?

Talking about my life or the future or anything around my parents and church friends

52:When was the last time I hugged someone?

Sunday

53:What if the last person I kissed was kissing someone else right in front of me?

I’d be really confused but I’d support and accept it

54:Is there anyone I trust even though I should not?

I only fully 100% trust one person, and I’m fairly sure the people I’ve talked to on here aren’t bad

55:What is something I disliked about today?

I once again didn’t do anything productive towards getting ready for college

56:If I could meet anyone on this earth, who would it be?

Barack Obama would be pretty neat to meet

57:What do I think about most?

My best friend

58:What’s my strangest talent?

My buddy, I have no clue. Probably making alright sounding composition things with no knowledge of theory or anything.

59:Do I have any strange phobias?

emailing people, talking on the phone with people

60:Do I prefer to be behind the camera or in front of it?

I don’t like filming, but I also am not the most comfortable in front of a camera at all times

61:What was the last lie I told?

Probably something related to emailing my professor about renting a tuba for band

62:Do I prefer talking on the phone or video chatting online?

Video chatting online is better than talking on the phone, but both are fifth out of five methods of communicating that I detailed up yesterday for my best friend.

63:Do I believe in ghosts? How about aliens?

No, and probably not. I do think aliens exist, but I don’t believe in aliens? Like, it’s rational to think that given the entire space, aliens have to exist, but also any thoughts we have about aliens don’t strike me as believable??

64:Do I believe in magic?

No

65:Do I believe in luck?

Yes and no, it depends, it switches back and forth. Kinda like if I believe in a monotheist God.

66:What’s the weather like right now?

Recovering from the ash from the wildfires. Also we’re transitioning from summer drought to our rest of the year “This is why Seattle has the reputation it does” weather, slowly but surely over the course of the next month before it truly kicks in mid-October.

67:What was the last book I’ve read?

The last book that I read start to finish every word was probably Khaled Hosseini’s “The Kite Runner”

68:Do I like the smell of gasoline?

Not particularly, no

69:Do I have any nicknames?

(Hot) Pete, and my last name

70:What was the worst injury I’ve ever had?

Split open my head and needed a couple stitches when I was 8

71:Do I spend money or save it?

If I had any self-control or discipline, I’d be that rich teenage white boy you hear a lot in the media

72:Can I touch my nose with a tounge?

No.

73:Is there anything pink in 10 feet from me?

Same as yesterday, the stuffed animal, pillow, and folder are all still here and my hot pink tie is still in my room about 40 feet away

74:Favourite animal?

I feel uneasy around pretty much any non-human sentient being, and then most human sentient beings as well. I just… don’t know how to answer this question honestly

75:What was I doing last night at 12 AM?

I was finishing up answering the rest of the asks last night at around midnight

76:What do I think is Satan’s last name is?

Satan is just a myth to scare people into being “better” people, where “better” is just a specific lifestyle dictated by whoever managed to gain influence in the doctrine and teachings of the religion.

His origins also come from a time where surnames and ‘last names’ were not a thing, so Satan is most likely a stand-alone name, much like Plato and Zeus.

77:What’s a song that always makes me happy when I hear it?

“She Used To Be Mine” by Sara Bareilles

78:How can you win my heart?

I’ll be the judge of that. It just… happens. Rachel, Kyle, Grae, Haley, Katie, Hot Luke, and others just……. existed, and then pretty much somehow they just became a big part of my life and I…. I just love them

79:What would I want to be written on my tombstone?

That I was a beloved friend who made a positive difference in their lives

80:What is my favorite word?

Aaaaahhhh! I know so many words, like, more than 5, and there are so many good ones!!!!!! Right now, I’m feeling music as the best word of the moment.

81:My top 5 blogs on tumblr

No. This is so rude. Why? Why must I single out a few blogs and tell the world that the interaction we’ve had isn’t enough for me and that you’re just not special enough to me? I refuse to do this.

82:If the whole world were listening to me right now, what would I say?

“I love my best friend, gay people are amazing, fund the arts, respect the arts, respect people who work the “undesired” jobs, work to protect the environment, and try to do things that make you happy while not harming other people or sentient beings.”

83:Do I have any relatives in jail?

Not that I know of

84:I accidentally eat some radioactive vegetables. They were good, and what’s even cooler is that they endow me with the super-power of my choice! What is that power?

I’m firmly in the teleportation camp. I hate being late and I’m not a fan of travelling.

85:What would be a question I’d be afraid to tell the truth on?

Hygiene-related questions… please…. I’m working on it…. let me be…..

86:What is my current desktop picture?

The default background

87:Had sex?

No, ew.

88:Bought condoms?

Never actually seen them accept in memes and once during health class in freshman year

89:Gotten pregnant?

No

90:Failed a class?

Yeah….. and it was the second semester of APUSH too…

91:Kissed a boy?

On his hand, which I’ll count

92:Kissed a girl?

Yeah

93:Have I ever kissed somebody in the rain?

No

94:Had job?

I became a CYO volleyball referee and reffed two seasons so far.

95:Left the house without my wallet?

Often, and since I’ve been driving, only twice (although one was driving up for a the campus tour at the college I ended up choosing, which was about 5 total hours of driving that day, a week after I got my license). I try to remember it when I go out because I saw a few months ago a post on here saying how valuable it is in case of an accident or something and the person has an ID, and I’ve been watching crime dramas for years and having an ID is always good.

96:Bullied someone on the internet?

Good heavens, no!

97:Had sex in public?

No! Ewwww, God that’s even worse

98:Played on a sports team?

I sooo miss volleyball, and soccer was fun too

99:Smoked weed?

I hope to be able to say no until I die

100:Did drugs?

I occasionally took my prescriptions… for like 2 months… whoops

But no, not for the intention of getting high or anything, I hate drugs, even advil and tylenol

101:Smoked cigarettes?

Fuck cigarettes (and no, I haven’t)

102:Drank alcohol?

A drop of an IPA when I was 13 and a sip of a red wine when I was 16 (with parental supervision that time), and nah, it isn’t my thing.

103:Am I a vegetarian/vegan?

Show me a well-prepared vegetable that has a decent flavor and I might be open to eating them more often

104:Been overweight?

Ever since I was like 2

105:Been underweight?

Never

106:Been to a wedding?

I think I’ve been to 5?

107:Been on the computer for 5 hours straight?

what do you think I do every day?

108:Watched TV for 5 hours straight?

So many wasted hours...

109:Been outside my home country?

Not yet

110:Gotten my heart broken?

Actually? Seriously? Like, more than just butt hurt over an infatuation? No, not really

111:Been to a professional sports game?

A couple baseball games

112:Broken a bone?

My ulna and radius, just above the wrist, on my dad’s 48th birthday back in fifth grade when I tripped over my two feet in the middle of our street and landed poorly. We didn’t go to the hospital for like 3 days

113:Cut myself?

Like, as in self-harming? No.

114:Been to prom?

No, freshman homecoming was off-putting enough for me after the aftermath…

115:Been in airplane?

Yeah! Flying is great!

116:Fly by helicopter?

No

117:What concerts have I been to?

I apparently went to two The Wiggles concerts when I was a baby, and since then it’s only been school concerts

118:Had a crush on someone of the same sex?

I think the desire was enough to elevate it past a mere infatuation, but it wasn’t like a full-on crush if you know what I’m saying.

119:Learned another language?

Not fully… I’m that kind of white person (minus the complete snobbish elitist attitude)

120:Wore make up?

It isn’t bad, but it’s too close to my eyes for me to be comfortable, and it’s wayyy too much work to do like every day just to look better than my meagerness. I’m already bad enough with basic hygiene, this would be too much (although I guess if I cared that much about it it might help this problem…). I’ll gladly wear it for a show, though.

121:Lost my virginity before I was 18?

The concept of virginity is complete bs to oppress women and “weak” men and is only fun in the ‘sacrificing a virgin into a volcano’ trope but even then I don’t like it (again, sex is gross for me, so no)

122:Had oral sex?

I have kissed and been kissed on my lips, various spots on my face, and my hands, and that’s it.

123:Dyed my hair?

No

124:Voted in a presidential election?

No, but I registered to vote on my eighteenth birthday this year and I voted in the primary elections back in August and I can’t wait to vote in the November elections because VOTING IS IMPORTANT ESPECIALLY IN NON-PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS WHEN ONLY A VERY LOW PERCENTAGE OF THE POPULATION VOTES!!!!! LIKE, IT’S DISAPPOINTING THAT ONLY ABOUT 50% OF THE POPULATION VOTES IN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, BUT THAT NUMBER DROPS TO 30-40% IN MIDTERM ELECTIONS AND ONLY 10-20% IN LOCAL-ONLY ELECTIONS (READ: ELECTIONS IN ODD-NUMBERED YEARS) AND THOSE NUMBERS BREAK MY HEART AND WE NEED TO VOTE MORE BECAUSE VOTING IS THE EASIEST WAY TO HAVE SOME LEVEL OF PARTICIPATION IN GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS AND IT IS IMPORTANT FOR THE VOICE OF THE PEOPLE TO BE HEARD AND IF YOU ONLY VOTE IN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS OR NEVER AT ALL, THEN THE PEOPLE WHO FAITHFULLY VOTE EVERY YEAR, AKA RICH OLD WHITE CONSERVATIVE MEN, ESSENTIALLY HAVE ALL OF THE VOICE IN THE ELECTIONS AND WE DO NOT NEED TO HAVE EVERYTHING ABOUT OUR GOVERNMENT DECIDED BY RICH OLD WHITE CONSERVATIVE MEN IF YOU’VE EVER READ ANY HISTORY TEXTBOOK OR REALLY ANYTHING, YOU SHOULD EASILY BE ABLE TO SEE WHY! PLEASE VOTE IN EVERY ELECTION!!!!!!!!!

125:Rode in an ambulance?

No

126:Had a surgery?

Do stitches count? Otherwise, no.

127:Met someone famous?

No

128:Stalked someone on a social network?

Too many times, sadly, and sorry

129:Peed outside?

Yeah

130:Been fishing?

No

131:Helped with charity?

I’ve volunteered with some non-profits, but I don’t think I’ve done so with a quote “charity” unquote.

132:Been rejected by a crush?

Probably? Most things were minor infatuations that I used to think were crushes, so I’m not sure. You could say that the most recent potential qualifier rejected me, but I would beg to differ given things now

133:Broken a mirror?

I was a reckless child

134:What do I want for birthday?

More time to spend alone with my best friend, more time to be with my best friend, a sudden influx of cash (and/or guaranteed financial stability), root beer and food and people to play games with

135:How many kids do I want and what will be their names?

Zero (0). However, if I do have kids, I’d probably adopt them, and I’d probably let them choose their names. Otherwise, I really like the names Luke, Pete®, James, Haley, Sara, Nicole, Alex (particularly for non-binary or female identifying persons), Rachel (though I probably wouldn’t name my kid that bc it’s too special for me), Hannah, and Emily.

136:Was I named after anyone?

My parents don’t say so.

137:Do I like my handwriting?

I’ve spent a long time crafting this efficient style, so yes. Also I have like three style to choose, my Most EfficientTM style, my All Caps (with the first letter taller than the others) style, and my fancy style with all of the tails at the end of the letters, the a like this font has it, the curls, anything I find to be fancy *jazz hands*

138:What was my favourite toy as a child?

Probably my little cars that I would move around on my city roads carpet along with a motorcycle that made had a brief jingle and then a simple noise that was super cool for 6-8 year old me

139:Favourite Tv Show?

Phineas and Ferb, or How I Met Your Mother

140:Where do I want to live when older?

Ideally, somewhere here in my hometown, I just love it here.

141:Play any musical instrument?

I can make a sound, but is it really playing? *suspenseful music crescendos*

142:One of my scars, how did I get it?

My Aunt re-married when I was 8 and the guy had a son a few months older than me, and we babysat him for a month during their honeymoon. Well, this boy wasn’t a good influence on me at all, but that’s beside the point. I thought he was… you know what, that actually is the point, but…. I though he was cool, and he could do things and did things that I wanted to try.

Well, one day, we laid out flat a futon and covered it with all the cushions and pillows from the couch that was also downstairs. Then, he grabbed an exercise ball, put it on the futon, got on it, rolled across the futon over the pillows, and stood up on the other side of the futon when he was done and I was so impressed, it blew my mind that he laid his midsection on the ball and rolled the ball like 6 feet and didn’t move or fall off of the exercise ball as it rolled.

So I tried it. And at the end, I slid off the ball, but not to land. I didn’t know how he stayed horizontal, and it showed, as I fell forward and slammed the side of me head into the corner of a cabinet right next to the far side of the cabinet. It hurt, and so I didn’t try a second time… until he successfully did it again a few minutes later. So I, desperately wanting to do it right and be “cool” like him, tried to do it again.

And I hit the exact same part of the side of my head on the corner of the cabinet again, almost exactly how my run went the first time. After the second hit, my head really hurt, and so I put my hands to my head, ran halfway up the stairs, and began to cry.

Also know that I was going through a phase where I loved to fake cry. I thought imitating the sounds of crying without the tears was one of the funniest things. And my mom hated it. She was a stay-at-home mom at that point, had been from a few months before I was born until my youngest sister entered elementary school with us. And so she was at home all day, every day (hence the babysitting). So, for the two months of summer by that point, my fake crying obsession was driving her up the wall.

Back to the story. Now, I’m sitting on the staircase, hands on my head because it hurts, tears forming in my eyes and my voice beginning to make all the crying sounds that I made when I was fake crying all summer so I guess my imitations were spot on. But after about a minute, I decided remove my arms from my head, and I looked at them, and there were lines of blood all the way from my fingers to my elbows and drops had fallen from my elbows onto my sock, and I shrieked.

I immediately went back down the stairs to the office where mom was on the computer, and the tears were coming almost as steady as the blood, and I was full-out crying. My mom, who was looking at the screen and thus only heard me crying, lashed out angrily, telling me to stop bothering her with that freaking fake crying. That is, until I got her to look at my arms. She took me upstairs and cleaned me up a little, but, while my bleeding slowed significantly, it didn’t stop.

After about 3 hours, my dad came home from work, and the bleeding still hadn’t stopped, and so we went to the hospital. I ended up getting 5 or 6 stitches, and when my hair is cut short enough, you can see the small white line.

That’s the only scar that I definitely know that I have. I haven’t really done anything physically risky since. That’s also pretty much when I stopped crying all that much…

143:Favourite pizza toping?

Extra cheese. Otherwise, sausage.

144:Am I afraid of the dark?

Only if I’m trying to sneak through somewhere and I can’t see where exactly I’m going

145:Am I afraid of heights?

Yeah, I would say I have a mild fear of heights. Specifically if I have to go down somewhere (like downhill slightly and there is a sharp decline on one side), or if I have to jump more than like 3 feet

146:Have I ever got caught sneaking out or doing anything bad?

I’ve been reprimanded for going out for most of the day and not saying anything, just disappearing for like 6 hours on a Sunday morning

147:Have I ever tried my hardest and then gotten disappointed in the end?

I never try my hardest

148:What I’m really bad at

Emailing people I need to, cleaning, hygiene, contacting people, calling people on the phone/talking to people on the phone, doing what I need to do

149:What my greatest achievements are

I graduated from high school, I won an CYO volleyball championship in sixth grade, I won a math competition in 7th grade (by guessing better than 19 other 7th and 8th graders from two different schools), and I…….. I haven’t really done much yet, nothing truly worthwhile (except maybe hs graduation)

150:The meanest thing somebody has ever said to me

I can’t think of anything, really. Although some acquaintances of mine made anti-Semitic “jokes” in front of me during summer camp this year and it bothered me a lot

151:What I’d do if I won in a lottery

I’d buy a large enough apartment to have space to wander around (picture Castle’s apartment from the show Castle, and pretty much like that but a little less opulent and I don’t need all the ornate luxuries around. Just the space of like 5-7 medium/large open rooms with a comfortable bed and a non-cramped bathroom or two, and a nice big kitchen for all the food I’m going to have.

I’d always have root beer in stock, along with some snacks that I like, and I’d have whatever foods my friends like because my closest friends would have invitations to come at literally any time (like, this is for max 6 people), and I’d like to regularly meet up with my closest friends and I’ll treat them to nice filling dinners at the local diners, Denny’s, wherever they want, even McDonald’s or whatever, and I’ll tip really well, like at least $50 dollars because those people are always so nice, and I’ll splurge so much on my friends.

I’d also donate a bunch to all of those people who really need it that I see come across my dash, and I’ll donate a crapload to my high school band because they meant the world to me, and I’d FUND THE ARTS BECAUSE THE ARTS ARE IMPORTANT.

152:What do I like about myself

I like that I love the arts and that I play the tuba and that I am getting into writing music and that I write poetry and that I love my friends especially my best friend and I like that I try to be positive and supportive of the LGBTQ+ community and that I actively try to make the world a slightly happier place most of the time

153:My closest Tumblr friend

Katie

154:Something I fantasize about

Getting to spend long periods of time with my best friend, having a bunch of money to spend on my best friend, being happy

155:Any question you’d like?

What is your favorite video game that you own that you’ve never seen elsewhere and is likely not well-known at all?

I love the game Puzzle Quest: Challenge of the Warlords for the Wii, and I can play it for hours upon hours for days and not get bored. It’s a really fun game with a long storyline that is entertaining and original, and I just love playing it and have literally only ever seen it at our house since my mom somehow found it and bought it like 7 years ago.

(yes, I made that question up myself)

Thank you for asking all of these!!!!!

(when I copied and pasted it to a google doc in case the computer shuts down and I lose the whole answer, it said that I had 4825 words and it took up 17 pages. So, yeah, this is 4867 words long!)

(And I was right, the everything disappeared and so I had to post it early so I could go back and edit it, so now it’s 4900 words long in total, after editing.)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best Places to See Elephants in Africa

The largest land mammal on earth has its comfortable home in Africa. Although there are some unique species of elephants in South East Asia, they are dwarfed compared to the African giants.

The spectacular scenery of these majestic animals makes them a must-see encounter in a lifetime.

The following are the 10 Best Places to See Elephants in Africa:

10. Skeleton Coast, Namibia

Famed for its unforgiving harshness to both sailors and most other beings, Skeleton Coast still has mercy for land’s biggest land mammal. Skeleton Coast is the only place on earth where you can find ‘desert elephants’.

The ‘desert elephants’ on this land that ‘God made in anger’ (as popularly known in local dialects) have uniquely adapted and eat quite a different type of vegetation than that eaten by their counterparts in the rich grasslands of Amboseli National Park. They are also smaller in weight, with much longer and slender legs characterized by more dynamic movements.

Due to scanty vegetation that barely covers the giant elephants’ nakedness, you can easily spot desert elephants[1] as they majestically straddle this barren land. You can either strategically position yourself near the drought-resistant bushes of mopane tree and camelthorn where they browse for a meal or position yourself near the riverbanks of Hoanib River where they go to quench their thirst and irrigate their drought-scorched hides. Whichever the case, you will have an experience unmatched elsewhere in the world – only in Africa, and particularly in Namibia.

Desert elephants in Namibia

9. Mana Pools National Park, Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is home to some of the largest herds of elephants – thanks to its fertile lands and rich vegetation.

Mana Pools National Park[2] is relatively a small park with just a few dozens of elephants. However, these elephants have some unique habits that attract curious visitors. The elephants here are not just big in size but have a unique acrobatic habit on standing on their two hind legs as they stretch their proboscis to pick the juiciest fruits and tastiest leaves hanging over the tall canopies. This acrobatic is not an easy endeavor bearing in mind that some of the elephants can reach 5 tons in weight.

This Park is located along the banks of River Zambezi, one of the mightiest rivers in Southern Africa. The river originates in Zambia, stretches eastwards through Eastern Angola – as if to fetch more water and then turns south-westwards to establish a border between Botswana and Zambia and then stretches further eastwards to demarcate the border between Zambia and Zimbabwe before pouring its precious collection into the Indian Ocean after trespassing Mozambique.

standing-on-two elephants of Zimbabwe

8. Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve, Malawi

Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve[3] is located in northern Malawi. It is a world-famous site due to its conservation efforts, championed by none other than Prince Harry of the British monarch.

Being a conservationists’ wildlife reserve, most of its elephants have been relocated from other Parks where they faced threats of poaching, drought, overpopulation, and diseases. Among the major sources of this relocation are the Liwonde and Machete National Parks.

So far, 500 elephants have been relocated into this Park. The park is optimized for tourist visits as a means of creating awareness of the conservation effort and also making the park more economically sustainable as the proceeds from tourism helps to plow back into the conservation efforts.

Elephants in Malawi

7. Kruger National Park, South Africa

Kruger National Park[4] is the most famous game park in South Africa and arguably the third most famous after Masai Mara and Serengeti National Parks. Like the other two Parks, Kruger National Park is home to the Big 5 land mammals and the Big 3 grey ones.

Elephants stomp their unmistakable authority as they traverse this Park. With plenty of well-kept driving tracks plus strategically positioned lodges, you can have an up-close view of these elephants as you enjoy the great hospitality of the African people and the soothing breeze of the African warm climate – only brewed in Africa – for you.

Elephants in Kruger National Park

Related Read: Best places to see Hippos

6. Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe

When it comes to the elephants narrative world-over, Hwange National Park [5]is a paradox. It is a paradox in the sense that, while elephant populations are dwindling at an alarming rate in other natural habitats across Africa, the opposite is the reality at Hwange. The elephant population has been rising sharply in this Park to the extent that it has raised alarm due to the risk of overpopulation. The current elephant population is 46,000 and is threatening to explode past the 50,000 mark in the near future.

There has even been protracted battle between the government of Zimbabwe and conservationists due to this encouragingly unique phenomenon. While the government wants to curl the excess population and sell its ivory so as to plow back the proceeds into conservation effort, conservationists are against this as they consider a bad precedent and an excuse for other parts of the world to formalize poaching.

The best time to view elephants is during the dry season that sets in between July and October. At such a time the dense vegetation becomes porous and also the elephants stay close to water sources. This way, it is easier to find them in specific locality than when they are spread out in the hugely expansive Park.

Elephants in Hwange National Park

5. Addo Elephant National Park, South Africa

This is probably the southern-most elephants natural habitat in Africa (and probably the world). Addo Elephant National Park[6] is just about 70 kilometers from the famous Port Elizabeth city. This is South Africa’s third largest national park that claims a whopping acreage of 1,800 km square.

Addo Elephant National Park is an encouraging story for conservationists. With a near extinct population of just 11 elephants in 1931, the population has grown naturally to reach a sizeable level of about 450 elephants.

The Park boasts of a great tracking infrastructure with plenty of Jeep safaris and horseback safaris available for one to traverse the lengths and widths of this massive park.

Elephants in Addo National Park

4. Chobe National Park, Botswana

Chobe National Park[7] is home to one of the world’s largest populations of elephants. There are about 50,000 to 60,000 elephants in this Park. Found in the semi-arid lands of Botswana, this Park is not so far from the world’s famous Victoria Falls – another of Africa’s great tourist attractions, found in neighboring Zimbabwe.

June-November is the best time to sight these giant land species. This is because that is the driest season and as such, most elephants lines the Chobe river to drink water and also to keep their large skins cool.

Taking a boat ride along the Chobe River is the assured way to watch and capture this enlivening moment.

Elephants in Chobe National Park

3. Okavango Delta, Botswana

Okavango Delta is a UNESCO World Heritage site[8] that is located in North-Western Botswana. Fondly referred to by locals as “plenty of plenty” and internationally billed as the ‘Eden of Africa’, Okavango Delta is home to boastful elephants – the largest land mammal on earth in a habitat natively occupied by some of the shortest people on earth – the pygmies. What a contrast? Well, not so strange in Africa.

Elephants in Okavango Delta

Must Read: Best Places to see Monkeys

2. Tarangire National Park, Tanzania

Tarangire National Park[9] is located in Northern Tanzania in the Manyara region. The Tarangire ecosystem is one of the richest in Africa in terms of hosting a variety of big wildlife.

Elephants in this Park are uniquely reddish in color – not natural but due to the red oxide dust that collects on their skin. Other than this unique ‘skin’ color, this is the place with the oldest known elephant twins. There have also been more twins born in this park. This is a rare occurrence.

This makes Tarangire National Park, not only a place with the highest population of elephants on earth but the only place on earth where you can witness reddish twin elephants – only in Africa, uniquely Tanzania.

Elephants in Tarangire National Park

1. Amboseli National Park, Kenya

Established in the Southern parts of Kenya and bordering Mount Kilimanjaro, Amboseli National Park[10] is home to the world’s longest-running elephant conservation program.

Amboseli has one of the most unique and panoramic sceneries of any Park in Africa. This is due to the fact that it is largely a plain land with short Savannah grassland. This makes it easy to make a photographic shot that captures a very wide area without obstructions. Established at the foot of Africa’s tallest mountain – Mount Kilimanjaro, makes it even more spectacular. You can easily capture a large Savannah grassland, the world’s largest land mammal, and Africa’s tallest mountain – all in one photograph. What more? All these while being caressed by the freshest breeze that nature brews atop Mt. Kilimanjaro.

Elephants in Amboseli National Park

Conclusion

The World’s biggest mammal has its indelible footprints on the land of its nativity – Africa. A visit to Africa without sight of elephants is no visit at all. Herein are the 10 best places to see elephants in Africa. Be glad that you now have a precise itinerary list of your next African elephant safari excursion.

Resource Links:

[1] Desert elephants of Namibia

[2] Mana Pools National Park

[3] Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve

[4] Kruger National Park

[5] Hwange National Park

[6] Addo Elephant National Park

[7] Chobe National Park

[8] Okavango Delta UNESCO

[9] Tarangire National Park

[10] Amboseli National Park

The post Best Places to See Elephants in Africa appeared first on Afrikanza.

0 notes

Text

Public War-- Reality, Politics And Power.

UNITED STATE Defense Assistant Ash Carter has released brand new plan suggestions targeted at inhibiting cigarette make use of within America's military that feature raising the rates from cigarette on army bases to match neighborhood market prices. Injunctive Alleviation: The GAI firmly advises versus imposing an antitrust law sanction for finding or executing injunctive relief, which is actually likely to lessen motivations to innovate and also discourage basic necessary license (SEP) owners coming from participating in regular environment, therefore robbing buyers from the considerable procompetitive perks from standardized innovations. We study the influence from scandal-driven media examination on the SEC's allowance of administration information. Bit over 18 months off currently, BMW's energy car lineup will definitely be actually substantially changed, primed to take in climbing SUV requirement in a progressively anti-car market. We understand that Chrysler put its Viper operations up for grabs as the provider -- as well as nation -- spiraled right into financial calamity back in 2008, however the date from the V10-powered cars's near-salvation by clients is hazy. Actually, Tesla's new policy is actually an instance from Musk exercising license civil liberties, not deserting them. When it comes to the pending mergers, certainly not simply will a consolidated Dow-DuPont and Bayer-Monsanto provide their personal mixed stacks, their systems improve in value through providing a wide suite of different cross-licensed product combinations. As I covered in my last article, nobody will doubt the need for greater combination between medical professionals and health centers - the dispute during the enactment of the Affordable Care Action (ACA") thorough just how the existing siloed technique to healthcare is actually the most awful of all globes, triggering intensifying prices as well as substandard treatment. As well as those spectators were actually considering Tesla motor vehicles near a mobile style center. Honda understands most importantly just how important the MDX has been to Acura's fortunes, having viewed as the label's auto volume was actually generally sliced asunder over the last decade. If the area court's ruling is actually upheld, this could possibly offer a deterrent to medical suppliers off additional including through mergings, a model antithetical to the quite targets from healthcare reform. With journalism hip observing on from the most ideal Film win for Spotlight at this year's Oscars, that seems like the line of work is undergoing a cinematic reinvention. The car I am discussing today is my wintertime beater, which is a 1999 Ford Escort SE car which claims that possesses a tick over 155,000 kilometers. As well as due to the fact that Jesus is actually the Lord and head of the church, he is the absolute most vital expert our team must seek advice from. Second, antitrust law does not impose a duty to manage opponents apart from in very restricted conditions In Trinko, for instance, the Court declined the invitation to expand a role to handle to conditions where an existing, volunteer economic partnership wasn't cancelled. Second, at the training class accreditation phase, ought to the defendant be actually allowed to stop the dependence anticipation off arising by showing evidence that the alleged misrepresentation cannot misshape the marketplace price of the sell at issue.

5 Doubts You Must Clarify Regarding gel.

Five Typical Blunders Everybody Creates In gel.

The Cheapest Technique To Make Your Base on balls To gel.

Since the views that moms and dads would like to inspire in their little ones can easily differ considerably, we ask that, instead of incorporating your personal opinions regarding exactly what is correct or incorrect in a movie, you use this component that can help parents make informed seeing choices by explaining the facts from appropriate settings in the title apiece from the other types: Sex as well as Nakedness, Brutality and also Gore, Obscenity, Alcohol/Drugs/Smoking, as well as Frightening/Intense Scenes. In its own recent selection on the Dow/Dupont merger, the European Commission located that the merger might have decreased advancement competitors for chemicals by planning to the capacity as well as the reward of the parties to introduce. Going against the pledge does not suggest you are actually mosting likely to be immediately reprimanded for accomplishing this, given that the PTP is actually certainly not planned to become primarily revengeful. Particularly Redemption, occupying these words of Titus 2:14, John Hurrion explains the teaching of atonement, focusing attention especially on the end and also layout, level and relevance of the fatality of Christ. So a couple of words on each with respect to Part 5, beginning along with the history. Dedicated to God is actually a new approach to an always applicable target, and also an operating guidebook to which the Religious can switch over and over for biblical direction and also spiritual instructions. If, nonetheless, you are certainly not yet a Religious, you have to soberly recognize that none of these things are awaiting you. In a tractor accident where Parker strikes a tree, falls as well as lands on his back while the tractor ruptures and also overturns in flame, he hollers in terror THE LORD ABOVE!" Virtually killed, Parker credits his marvelous getaway to divine assistance and also encounters the cement reality from God's existence in his life. If you liked this posting and you would like to acquire extra details relating to http://dashbidle.info kindly visit our web-page.

0 notes