#paucity

Text

#5992

In a constant brutality

That is the sovereignty

Of moral paucity,

Lost is our humanity.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Closely connected to the act of name signing was the act of writing poems on walls. As scholars have already pointed out, with beginnings traceable to the Six Dynasties, wall poems (tibishi) were already very widespread during the Tang. By Christopher Nugent's count, well over one thousand entries in the Complete Tang Poems had titles indicating that they began as inscriptions on some surface other than paper or scrolls. These surfaces included walls at places of gathering and transit, such as post stations, scenic sites, inns, and increasingly in the latter part of the Tang, Buddhist temples, which also served public roles for lay gatherings and performances. (100)

In one anecdote, a latecomer casts aspersions on a first writer's literary skills, comparing him to the general Xiang Yu (232-202 BCE), who was infamous for having learned just enough writing to manage his name: "Li Tang signed his name on a pavilion in Zhaoying County. When Wei Zhan [jinshi degree 865] saw it, he took a brush and dashed off a taunt: 'The rivers of Wei and Qin brighten the eyes, / but why is Xiren short on poetic spirit? / Perhaps he mastered only what Beauty Yu's husband could / learning to write just enough to put down his name.' " ... It would not be a stretch to imagine the sniggering of those who read this inscription in a frequented pavilion. (102)

For a degree seeker in Chang'an, these circuits of information and judgment received more discussion than the actual examination itself. Tang literati wrote copiously about activities such as name signing, public exposure, and triumph. It would not be an exaggeration to say that in ninth-century temples and popular recreation areas, the vertical spaces were teeming with verses that clamored for attention. (104)

selections on poetic graffiti from linda rui feng's city of marvel and transformation: chang'an and narratives of experience in tang dynasty china (university of hawaii press, 2015)

#china#tang dynasty#tagamemnon#<- couldn't stop thinking about graffiti from pompeii while reading this chapter so i suspect it may be of interest to rome-heads in genera#this was very promising book that felt like it failed to fully deliver - can't tell if the author was trying not to get into aspects which-#-have a paucity of surviving sources or if perhaps she was trying to avoid stepping on the toes of existing scholarship#e.g. nugent's mentioned book on poetry production/circulation or juduth zeitlin's article on wall poems and anxieties of loss#but even though i felt like it needed another 50-100 pages of fleshing out there are some generally remarkable moments in here#bits that can be put in remarkable parallel with imperial rome certainly; more fascinatingly with 19th- and early 20th-century fiction-#-that deals closely with 'new' modern urban life. where the forms & patterns of the city itself collude with residents against the newcomer#some interesting notes on bai juyi in here too. though i don't know if they're news to any real bai juyi stans out there

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snake eyes

he's a owns a club

a calm and calculated person who isn't so calm if they find you've disrespected any of their staff

he'd gladly turn you inside out if he needs too

☕|🧀

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today I'm being frustrated by the fandom convention of saying "There's always an apostate who betrays you".

1) Morrigan doesn't betray anything, she saves the Warden's life. Even if you tell her to leave, she comes back to make sure there's a way for you to stay alive. That she's doing this for her and Flemeth's secret reasons doesn't really matter, in my opinion. Do they just mean "She leaves after the final battle"? Because that's not a betrayal unless you count it as a breakup, and even if you romanced her you can find her and go into the eluvian with her.

2) Anders, also, doesn't betray Hawke! Maybe if you're not paying attention to a single thing he says or does during the game the chantry explosion can come as a surprise (even after he asked for salpeter by name 🙄), but it's not actually a personal betrayal that he has his own life and freedom fighting separate from Hawke's. He tells you he's part of the mage underground, he tells you he can't sit idly by when mages are suffering. Sebastian says "You've made no secret of your intent to lead the mages here in revolution", and he's RIGHT, all of Hawke's friends know his plans, and none of them help him! Even Merrill says it isn't her fight! (Anders is also shitty about elves; they're even there.) Who is he betraying when none of them let themselves be that close to him in the first place?

3) Solas… is the whole reason Corypheus got power, and would have destroyed the world anyway if Corypheus hadn't tried. So I can understand seeing that as a betrayal, except it isn't personal, is it? He didn't know the Inquisitor at all before they interrupted his plan, and he gave them the resources to fight his mistake. And then, like Morrigan, he leaves after the final battle. The horror. Trespasser is more of a betrayal, since he gets the Inquisition embroiled in a war. I'll accept that. I don't like Solas, but like Anders, having his own life and plans doesn't count as a "betrayal", to me.

Are we just saying all lies are betrayals? Because mages aren't the only ones who lie! Does Blackwall betray you? Is Leliana betraying you when she pretends she wasn't a Bard? Is Varric not talking about Bianca a betrayal? Why not? Why are people so fixated on this narrative?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

everyone was so harsh to alola it deserved so much better. like this region is so well designed and so pretty and the story is actually really fun? will never forgive everyone for what we did to her

#I started a sun nuzlocke and granted I’ve only just finished the melemele grand trial#and idk! I’m having a great time!#when I played it the first time I didn’t love it but I was also doing pretty bad at the time and had started being less into pokemon#there are reasons I understand being frustrated like the constant stop start of tutorials and cutscenes but also like?#maybe it’s that i know they’re coming and have accepted it but can’t you just like enjoy the ride? it’s a way more involved story I guess#like you get to talk to lillie and hau a bunch and see what they’re up to! feels more like actually going on a journey w your friends yknow#compared to idk sinnoh where you run into Barry occasionally or even bw where there are 3 parallel journeys which intersect#also think when I first played it I didn’t like the removal of megas. z moves as a concept. and the removal of national dex#and yeah all those things suck a little bit maybe I’m just more used to it now after galar+paldea#idk! but man alola itself is so cool it’s just so good#I rlly love the environments and the island setup and god alolan pokemon are so fun#the one thing I DO have beef abt is the relative paucity of grass types but it’s not even that bad. that’s a me thing bc i like grass types#(it would be unfair to judge alola on ice types especially given they’re kinda the best about it to that point bc of tapu village)#anyway I’m rambling but alola!!! alola my beloved I’m so sorry#this is my first time properly playing since it came out bc I didn’t wanna restart ultra/sun for the longest time#my original sun had all my ancient pokemon from the bank launch free trial. rip to my original black + x teams. and also the 2020 mythicals#ultra sun is my last original save file pre-switch so i am very reluctant to restart that. maybe one day. until then! sun <3#luke.txt

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

turning over the phrase "a paucity of information" in my mind. it's a good phrase

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

In August of 2019, a special issue of the Times Magazine appeared, wearing a portentous cover—a photograph, shot by the visual artist Dannielle Bowman, of a calm sea under gray skies, the line between earth and land cleanly bisecting the frame like the stroke of a minimalist painting. On the lower half of the page was a mighty paragraph, printed in bronze letters. It began:

In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the British colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists. America was not yet America, but this was the moment it began.

The name of this endeavor was introduced at the very bottom of the page, in print small enough to overlook: “The 1619 Project.” The titular year encapsulated a dramatic claim: that it was the arrival of what would become slavery in the colonies, and not the independence declared in 1776, that marked “the country’s true birth date,” as the issue’s editors wrote.

Seldom these days does a paper edition have such blockbuster draw. New Yorkers not in the habit of seeking out their Sunday Times ventured to bodegas to nab a hard copy. (Today you can find a copy on eBay for around a hundred dollars.) Commentators, such as the Vox correspondent Jamil Smith, lauded the Project—which consisted of eleven essays, nine poems, eight works of short fiction, and dozens of photographs, all documenting the long-fingered reach of American slavery—as an unprecedented journalistic feat. Impassioned critics emerged at both ends of the political spectrum. On the right, a boorish resistance developed that would eventually include everything from the Trump Administration’s error-riddled 1776 Commission report to states’ panicked attempts to purge their school curricula of so-called critical race theory. On the other side, unsentimental leftists, such as the political scientist Adolph Reed, Jr., accused the series of disregarding the struggles of a multiracial working class. But accompanying the salient historical questions was an underlying problem of genre. Journalism is, by its nature, a provisional and fragmentary undertaking—a “first draft of history,” as the saying goes—proceeding in installments that journalists often describe humbly as “pieces.” What are the difficulties that greet a journalistic endeavor when it aspires to function as a more concerted kind of history, and not just any history but a remodelling of our fundamental national narrative?

In the preface to a new book version of the 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones, a Times Magazine reporter and the leading force behind the endeavor, recalls that it began, as many journalistic projects do, in the form of a “simple pitch.” She proposed a large-scale public history, harnessing all of the paper’s institutional might and gloss, that would “bring slavery and the contributions of Black Americans from the margins of the American story to the center, where they belong.” The word “project” was chosen to “emphasize that its work would be ongoing and would not culminate with any single publication,” the editors wrote. Indeed, the undertaking from the beginning was a cross-platform affair for the Times, with special sections of the newspaper, a series on its podcast “The Daily,” and educational materials developed in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. By academic standards, the proposed argument was not all that provocative. The year 1619 itself has long been depicted as a tragic watershed. Langston Hughes wrote of it, in a poem that serves as the new book’s epigraph, as “The great mistake / That Jamestown made / Long ago.” In 2012, the College of William & Mary launched the “Middle Passage Project 1619 Initiative,” which sponsored academic and public events in anticipation of the approaching quadricentennial. “So much of what later becomes definitively ‘American’ is established at Jamestown,” the organizers wrote. But the legacy-media muscle behind the 1619 Project would accomplish what its predecessors in poetry and academia did not, thrusting the date in question into the national lexicon. There was something coyly American about the effort—public knowledge inculcated by way of impeccable branding.

The historical debates that followed are familiar by now. Four months after the special issue was released, the Times Magazine published a letter, jointly signed by five historians, taking issue with certain “errors and distortions” in the Project. The authors objected, especially, to a line in the introductory essay by Hannah-Jones stating that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” Several months later, Politico published a piece by Leslie M. Harris, a historian and professor at Northwestern who’d been asked to help fact-check the 1619 Project. She’d “vigorously disputed” the same line, to no avail. “I was concerned that critics would use the overstated claim to discredit the entire undertaking,” she wrote. “So far, that’s exactly what has happened.”

The pushback from scholars was not just a matter of factuality. History is, in some senses, no less provisional than journalism. Its facts are subject to interpretation and disagreement—and also to change. But one detected in the historians’ complaints a discomfort with the 1619 Project’s fourth-estate bravado, its temperamental challenge to the slow and heavily qualified work of scholarly revelation. This concern was arguably borne out further in the Times’ corrections process. Hannah-Jones amended the line in question; in both the magazine and the book, it now states that “some of the colonists” were motivated by Britain’s growing abolitionist sentiment, a phrasing that neither retreats from the original claim nor shores it up convincingly. In the book, Hannah-Jones also clarifies another passage that had been under dispute, which had claimed that “for the most part” Black Americans fought for freedom “alone.” The original wording remains, but a qualifying clause has been added: “For the most part, Black Americans fought back alone, never getting a majority of white Americans to join and support their freedom struggles.” As Carlos Lozada pointed out in the Washington Post, the addition seems to redefine the meaning of the word “alone” rather than revise or replace it. In my view, the original wording was acceptable as a rhetorical flourish, whereas the amended version sounds fuzzy.

In the book’s preface, Hannah-Jones doesn’t dwell, as she well could have, on the truly deranged ire the Project has triggered on the right over the past few years. (Donald Trump’s ignorant bluster is mercifully confined to a single paragraph.) But neither is she entirely honest about the scope of fair criticism that the work has received. She files both academic disagreement (from “a few scholars”) and fury from the likes of Tom Cotton under the convenient label “backlash,” and suggests that any readers with qualms resent the Project for focussing “too much on the brutality of slavery and our nation’s legacy of anti-Blackness.” (Meanwhile, even the five historians behind the letter wrote that they “applaud all efforts to address the enduring centrality of slavery and racism to our history.”) The editors of the book, who include Hannah-Jones and the Times Magazine’s editor, Jake Silverstein, want to “address the criticisms historians offered in good faith”; accordingly, they’ve updated other passages, including ones on Lincoln and on constitutional property rights. But even the use of the term “good faith” suggests a hawkish mentality regarding the revisions process: you’re either against the Project or you’re with it, all in. There is little room in a venue as public as the 1619 Project’s for the learning opportunities that arise when research sets its ego aside and evolves in plain sight.

As Hannah-Jones notes, the disagreements needn’t undermine the 1619 Project as a whole. (After all, one of the letter’s signatories, James M. McPherson, an emeritus professor at Princeton, admitted in an interview that he’d “skimmed” most of the essays.) But the high-profile disputes over Hannah-Jones’s claims have eclipsed some of the quieter scrutiny that the Project has received, and which in the book goes unmentioned. In an essay published in the peer-reviewed journal American Literary History last winter, Michelle M. Wright, a scholar of Black diaspora at Emory, enumerated other objections, including the series’ near-erasure of Indigenous peoples. Wright sees the 1619 Project as replacing one insufficient creation story with another. “Be wary of asserting origins: they tend to shift as new archival evidence turns up,” she wrote.

The Project’s original hundred pages of magazine material have, in the new volume, swelled to more than five hundred, and certain formatting changes seem designed to serve its “big book” aspirations. Lyrical titles from the magazine issue, such as “Undemocratic Democracy” and “How Slavery Made Its Way West,” have been traded for broadly thematic ones (“Democracy,” “Dispossession”) and now join sixteen other single-word chapter titles, such as “Politics” (by the Times columnist Jamelle Bouie), “Self-Defense” (by the Emory professor Carol Anderson), and “Progress” (by the historian and best-selling anti-racism author Ibram X. Kendi). Along with the preface and an updated version of the original ruckus-raising essay, Hannah-Jones has written a closing piece, cementing her role as the 1619 custodian. In the manner of an academic text, the Project is showier about its scholarship this time around, sometimes cumbersomely so, with in-text citations of monographs with interminable titles. New essays, by scholars including Martha S. Jones and Dorothy Roberts, pointedly bolster the contributions from within the academy. Perhaps also pointedly, endnotes at the back of the book list the source material, which the series in magazine form had been accused of withholding.

At the same time, many of the essays in the book remain shaped according to the conventions of the magazine feature. First, a contemporary scene is set: the day after the 2020 election; the day Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd on a Minneapolis street; Obama’s first campaign for President; Obama’s farewell address. Then there is a section break, followed by a leap way back in time, the sort of move that David Roth, of Defector, has called, not without admiration, “The New Yorker Eurostep,” after a similarly swerving basketball maneuver. For the 1619 Project, though, the “Eurostep” isn’t merely a literary device, used in the service of storytelling; it is also a tool of historical argument, bolstering the Project’s assertion that one long-ago date explicates so much of what has come since. Modern-day policing evolved from white fears of Black freedom. Slave torture pioneered contemporary medical racism. For each of those points a historical narrative is unfolded, dilating here and leapfrogging there until the writer has traversed the promised four hundred years and established a neat causal connection.

For instance, an essay by the lawyer and professor Bryan Stevenson traces the modern plague of mass incarceration back to the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery but made an exception for those convicted of crimes. In his eight pages outlining the “unbroken links” between then and now, Stevenson breezes past the constellation of policies that gave rise to mass incarceration in the span of a single sentence—“Richard Nixon’s war on drugs, mandatory minimum sentences, three-strikes laws, children tried as adults, ‘broken windows’ ”—and explains that those policies have “many of the same features” as the Black Codes that controlled freed Black people a century and a half ago. (The language here has been softened: in his original magazine piece, Stevenson deemed the Black Codes and the latter-day policies “essentially the same.”) It is not an untruthful accounting but it is an unstudious one, devoid of the sort of close reading that enlivens well-told histories. Alighting only so briefly on events of great consequence, many of “The 1619 Project” contributions end up reading like the CliffsNotes to more compelling bodies of work.

At its best, the book’s repetitive structure allows the stand-alone essays to converse fruitfully with one another. Matthew Desmond, explaining the origins of the American economy, describes the lengths the Framers went to secure the country’s chattel, including by adding a provision to the Constitution granting Congress the power to “suppress insurrections.” The implications of that provision and others like it are explored in the essay “Self-Defense,” by Anderson, whose note that “the enslaved were not considered citizens” acquires richer significance if you’ve read Martha S. Jones’s preceding chapter on citizenship. But the formula wears over time. With few exceptions—among them, a piece by Wesley Morris, a masterly stylist—the voices of the individual writers are unrecognizable, hewn to flatness by the primacy of the Project’s thesis. Regretfully, this is true even of the book’s poems and short fiction, which, in a rather utilitarian gesture, are presented between chapters along with a time line that aids the volume’s march toward the present.

For instance, the book’s very first listed event—the arrival of the White Lion in August, 1619—is followed by a poem by Claudia Rankine, which sits on the opposite page and borrows its name from that ship: “The first / vessel to land at Point Comfort / on the James River enters history, / and thus history enters Virginia.” A short piece by Nafissa Thompson-Spires depicts the interior monologue of a campaigner for Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman to run for President, after Chisholm decided to visit George (“segregation forever”) Wallace in the hospital following an assassination attempt in 1972—a visit noted in a time line on the preceding page. As in much of the other fiction in the volume, Thompson-Spires’s prose is left winded by the responsibilities of exposition: “It seemed best not to try to convert the whites but to instead focus on registering voters, especially older ones on our side of town, many of whom, including Gran and PawPaw, couldn’t have passed even a basic literacy test.”

The didacticism does let up on occasion. An ennobling found poem by Tracy K. Smith derives its text from an 1870 speech by the Mississippi Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first Black member of congress, who, a month after his swearing in, had to argue to keep Georgia’s duly elected Black legislators, who’d been denied their seats by the Democrats. (“My term is short, fraught, / and I bear about me daily / the keenest sense of the power / of blacks to shed hallowed light, / to welcome the Good News.”) A poem by Rita Dove channels the antsiness of Addie, Cynthia, Carol, and Carole, the four children who perished in a church bombing in Birmingham on September 15, 1963: “This morning’s already good—summer’s / cooling, Addie chattering like a magpie— / but today we are leading the congregation. / Ain’t that a fine thing!” But, on the whole, the literary creativity fits awkwardly with the task of record-keeping. It is a shame to assemble some of the finest and most daring authors of our time only to hem them in with time stamps.

So what are the facts? There are plenty in the volume that aren’t likely to be disputed. In the late seventeenth century, South Carolina made its whites legally responsible for policing any slave found off of the plantation without permission, with penalties for those who neglected to do so. In 1857, the Supreme Court decided against Dred Scott, ruling that Black people “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides.” In 1919, the U.S. Army strode into Elaine, Arkansas, and gunned down hundreds of Black residents. In 1960, Senator Barry Goldwater mourned the decline of states’ rights heralded by Brown v. Board of Education, contending that protecting racial equality was not federal business. In 1985, six adults and five children in Philadelphia received “the commissioner’s recipe for eviction,” as Gregory Pardlo writes in a poem, including “M16s, Uzi submachine guns, sniper rifles, tear gas . . . and one / state police / helicopter to drop two pounds of mining explosives combined with two / pounds of C-4.” In 2020, Black Americans were reportedly 2.8 times more likely to die after contracting covid-19. What the 1619 Project accounts for is the brutal racial logic governing the “afterlife of slavery,” as Saidiya V. Hartman has put it in her transformative scholarship (which is referenced only once in this book, in an endnote, but without which a project such as 1619 might very well not exist).

The book’s final essay, by Hannah-Jones, argues in favor of reparations so that America may “finally live up to the magnificent ideals upon which we were founded.” By “we” here she is referring to the nation as a whole, but embedded in Hannah-Jones’s vision is a more provincial collective identity. The convoluted apparatuses of anti-Black racism don’t spare individuals based on the specifics of their family trees. Black Americans encompass those whose roots in this country date back for many generations, or for one. Yet Hannah-Jones’s unstated but unsubtle suggestion is that a particular subset of Black people, namely those of us who can trace our ancestry to slavery within the nation’s borders, are the truest inheritors of America, both its ills and its ideals. We represent the country’s best “defenders and perfecters,” are “the most American of all,” and are not “the problem, but the solution.” These dubious honors are pinned, like badges of pride, at the volume’s beginning and end, and, for me, the imposition of patriotism is more bothersome than any debated factual claim. In spite of all of the ugly evidence it has assembled, the 1619 Project ultimately seeks to inspire faith in the American project, just as any conventional social-studies curriculum would.

This faith finds its most sentimental expression in another new book about 1619, “Born on the Water,” which was co-authored by Hannah-Jones and Renée Watson for school-aged readers. Beautifully illustrated by Nikkolas Smith, it centers on a young Black girl’s familiar dilemma during a classroom genealogy assignment—what knowledge does she have to share about an ancestry that was torn asunder by the Middle Passage? One answer comes on the story’s final page, in which the girl is seated at her desk, smiling, her hands poised midway through crayoning stars and stripes for “the flag of the country my ancestors built, / that my grandma and grandpa built, / that I will help build, too.” Here the 1619 Project has left the genres of journalism and history for the realm of fable. But a similar thinking resides at the center of the 1619 Project in all of its evolving forms—past, present, and future, arranged in a single line.

#the 1619 project#nikole hannah-jones#lauren michele jackson#us history#LMJ is such an incredible thinker/writer and this essay always makes me mad about the relative paucity of the rest of the discourse#around the 1619 project#everything getting swept up into our endless culture war debates robs us of real thoughtful scholarship and cultural criticism#also this reminds me that I still need to read her book it's been on my list for years now

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

More please

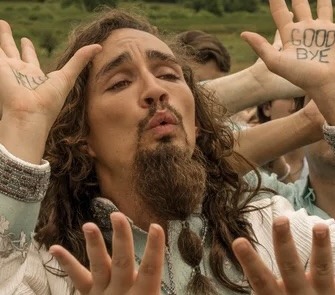

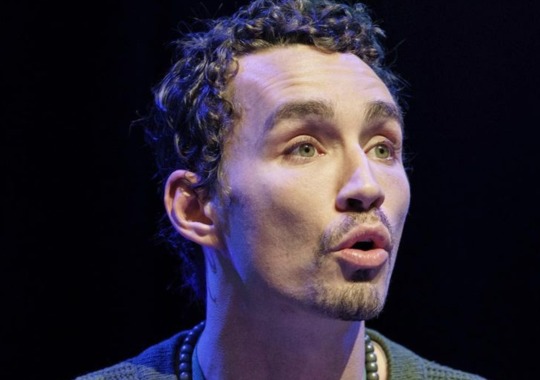

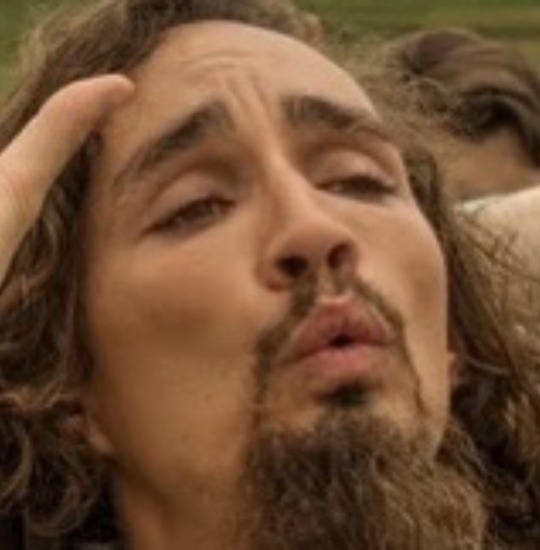

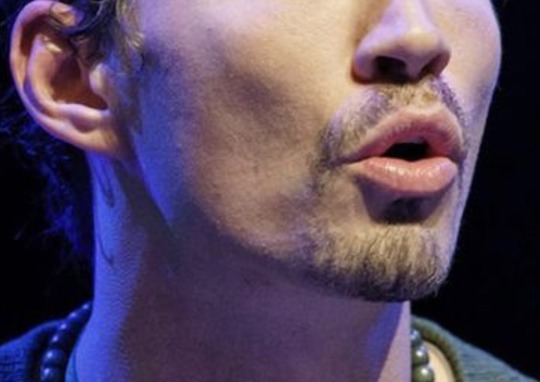

#robert sheehan#the umbrella academy#tua#klaus hargreeves#tua s2#rob’s kisser#that mouth though#Rob’s lips#even look soft#how dare he#offended#by the paucity of pucker pictures#right?#british library#irish writers#something or other#new clothes finally

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

#5472

Your name shall be Cain,

Cursed to be a bane

To the earthly fertility

And the origin of paucity.

May you forever wander

Till the birth of a new order.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

*me, today* sayonara you weaboo shits *post last chapter of yet another 100k monster*

*me, not even three hours later* but what if Alutagawa was kidnapped and Atsushi went feral trying to find him haha

#never beating the not being able to shut up allegations I’m afraid#sorry but the bungos are in a HUGE paucity of actually good long fics#I can show you the world

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The imbalance of materials is at least as marked. For Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, the sources are to be numbered in the thousands; for Catherine Parr, in the hundreds; and for the remaining three, in their dozens. To attempt roughly equal treatment of the six women, therefore, as has been the general practice, is to distort the record: the lesser are inflated and the greater diminished. Here, instead, I have let the weight of materials and importance shape the structure of the book.

Six Queens of Henry VIII, David Starkey

#are sources of anne of cleves' really 'in their dozens'; tho?#they exist in numerous languages and she had a very long life even if it was only in 'the spotlight' for six months; generously two years#as she's still semi-frequently noted by contemporaries during her successor's queenship......#i do otherwise agree tho#paucity of evidence is the main reason there's more biographies on the three names than the others#david starkey#*those#90% supposition does not make for the most readable biography

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

how did i do this-

im tempted to give razz an aquatic color pallet

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

5, 10, and 19 for DAV asks!

Thank you for asking!

5. Do you typically use a preset character and name or spend hours in the character creator coming up with a custom one?

I've only ever used the preset character in DAI when I can't be bothered recreating my Hawke, but for the start of every new character I definitely spend WAY too much time designing them. To the point of using modded character creation screens to get more options so they'll be Just Right.

10. Which location are you most excited/hoping to explore in-game?

Nevarra!!! I want to know more about Nevarra, it makes SO little sense to me. How is it Ancient Egypt but in the Thedas equivalent of Britain? Why are the mortalitasi ALLOWED, when that's explicitly "magic ruling over man" since they're given power over every funeral? Are there non-mortalitasi mages? We know from Absolution that Nevarra has a mage tower, is that a prison like in other countries or more like a school for what is basically a priestly class? I need more Nevarra.

19. Are you planning to replay any of the previous games, watch Dragon Age: Absolution, or read any of the books/comics/short stories, or are there other games you want to play in the meantime?

I'm in a constant state of replaying the previous games, and I've also read all the books and comics and short stories. I should probably re-watch Absolution and re-read Tevinter Nights, for the most recent context. ALSO, as a recommendation, everyone should at least read The Missing (comic series), because it introduces so much that will be in Veilguard.

0 notes

Text

Israel may be completely converting Palestine into a desert, by uprooting its families, and stripping it of vegetation and water. It was not until after 1948 that 90% of Israeli forests were grown, but non-Indigenous species constitute 89% of them. The majority of trees JNF boasts having planted, since nearly its inception, were non-Native evergreens, which devastated both local communities and ecosystems. For instance, animals belonging to Palestinian shepherds could not feed on greenery, after it was acidified by the shedding of Israeli pine needles. Besides, as evidenced by the most critical wildfire Israel experienced, in 2010, these are highly flammable trees. Israeli planted forests have even been termed ‘pine deserts’, by environmentalists, due to the ‘biological paucity’ they have caused. Furthermore, as Nathan notes, Indigenous carob and fruit trees, including more than 800,000 olive trees, since only 1967, were uprooted by Israel. In Israeli-occupied Palestine, 80% of the responsibility for a staggering 23% reduction in its forests, which occurred from 1971 to 1999, fell on Israeli colonialism and militarism. Only in 2001, the Israeli state uprooted 670,000 fruit and forestry trees there. In addition, research has shown that an-Naqab possibly began to experience desertification due to JNF afforestation. Yet, the ahistorical trope of ‘making the desert bloom’ continues to be widely proliferated by Zionists, assisted by green colonies, to stifle Palestinian memory and erase the Nakba.

Ghada Sasa, Oppressive pines: Uprooting Israeli green colonialism and implanting Palestinian A’wna

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

More troubling than a paucity of raw, animal magnetism is the manner in which both Vance and Poilievre have leveraged their modest appeal. The two have, in different ways, hitched their political wagons to extremist movements that have crept into political life. In 2021, Poilievre threw his lot behind the so-called “Freedom Convoy,” which saw Ottawa jammed with truckers protesting COVID-19 mandates. On Facebook, he called the truckers “peaceful, kind and patriotic.” The protests were sometimes peaceful. But they also featured white supremacist and Nazi symbols, with some organizers having long, checkered histories of Islamophobic agitation.

199 notes

·

View notes