#petit Gervais…..

Text

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Well, but how is this? I gave you the candlesticks too, which are of silver like the rest, and for which you can certainly get two hundred francs. Why did you not carry them away with your forks and spoons?"

#Les Miserables#Victor Hugo#Jean Valjean#The lesson may not take right away but it certainly plants the seeds for when he has his encounter with poor Petit Gervais

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barricade Day Advent Calendar

Day 9: Petit-Gervais

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

was doing the hunger game simulator with les mis characters and

#holy shit#petit gervais#les miserables#broadway#les mis#enjoltaire#grantaire#victor hugo#vicky hugo

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

#one thing i will give the 2018 miniseries credit for is including the petit gervais scene#truly an insane moment#les mis#les miserables#jean valjean#valjean#petit gervais#mine

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

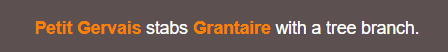

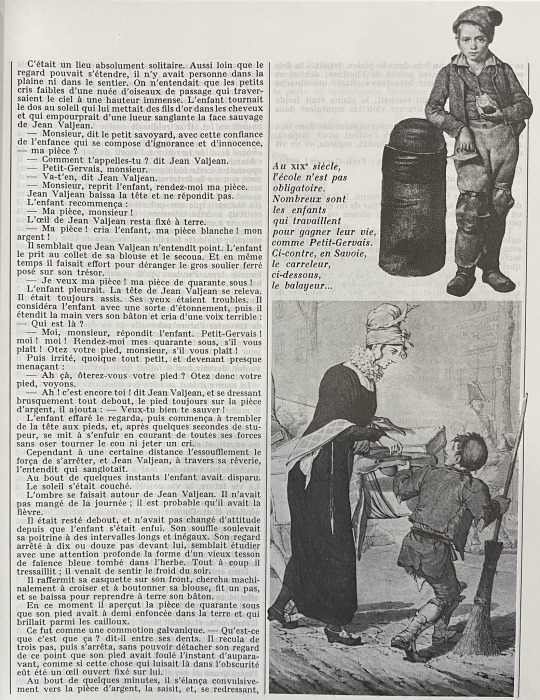

The illustrations in "Petit Gervais" chapter from Le Rayon D'Or Collection (1977)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

god i love reading good books. like, how am i supposed to go on with my day when jean valjean is out there weeping for the first time in nineteen years?

#he's REAL you know what i mean#by me#les mis letters#les mis#les miserables#the brick#jean valjean#petit gervais#victor hugo#jvj

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Valjean did to Petit Gervais. Volume 1, Book 2, Chapter 13.

Clips from <Il cuore di Cosette>.

#Les miserables#les mis#My Post#Jean Valjean#Petit Gervais#What I Have Done?#It was such a nice touch that the skipped part of Musical appeared on a Children's Cartoon Show.#The Brick#Il cuore di Cosette#Les Mis Letters

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

He began to walk again, then quickened his pace to a run, and from time to time stopped and called out in that solitude, in a desolate and terrible voice: “Petit Gervais! Petit Gervais!”

80 notes

·

View notes

Video

Okay now that we’ve gotten to LM 1.2.13 in Les Mis Letters, I have to post my absolute favorite take on the Petit-Gervais scene — it’s so good that I’ve been thinking about it ever since I first saw it. It’s from the first episode of Les Miserables 1967, a BBC miniseries.

I love how brusque and rude Valjean is — how little he is listening to Petit-Gervais, and how clearly he is wrapped up in his own thoughts. I love the horrified shock of realization he has when he sees he stepped on the coin. I love how desperate his cries of “Petit-Gervais!” are. I love how he stumbles and falls over himself.

But the best part of this scene is the way he cries.

Depictions of emotional male grief are rarer than they should be in visual media, and that makes this scene even more powerful. Valjean in this scene cries — no, gutturally sobs for a full 45 seconds, to the end of the episode in fact. We are not spared from his grief —we are not allowed to look away. He sobs, horribly, brokenly, in the way we have all cried, when we’ve done something wrong, and know there is no way of fixing it. It is an incredibly powerful scene, especially when taken in context with the rest of the episode. Frank Finlay’s Valjean is very internal and rough until this scene — this is the first real part we see him break.

Although I have seen many takes on this scene, 1967′s unflinching depiction of Valjean’s grief makes this the most memorable for me.

#Les Mis Letters#LM 1.2.13#Les Mis#Les Miserables#Les Mis 1967#Les Miserables 1967#Jean Valjean#Valjean#Petit-Gervais#Frank Finlay#John Gulgoka#video#1967 is flawed but man oh man when it hits it hits.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is ~2500 words of Petit-Gervais and the Conventionist’s shepherd boy fic. There may be more at some point, if I ever write it, but my current writing pace suggests that it’ll be a while, if it happens at all. So I thought I’d share this chunk, for posterity and because I quite like it.

@pilferingapples

~*~

The week after the prime part of Petit-Gervais' fortune had been stolen from him, a storm raged through the area. Petit-Gervais had lingered, ashamed to go home without his money and hoping against hope that the gendarmes would bring in the villain who had robbed him. But as the days went by this seemed less and less likely, and Petit-Gervais had resolved to be on his way the very day the tempest hit.

The rain quickly tore through the shelter he had built, and he wasted only a few moments staring mournfully at the wreckage before setting off to find something sturdier. There was a town nearby; perhaps someone would take pity on him and let him inside. Perhaps they would even have food to share! The thought bolstered his step and made him nearly cheerful as the marmot on his back screamed into the wind.

Unlike in Paris, the rain in this country fell hard but not long. By the time Petit-Gervais finally stumbled across a dwelling-place, the worst had passed and only a drizzle remained. Petit-Gervais and his marmot were soaked to the bone.

He nearly tripped over the hut before he noticed it. It was a rude structure, built into a hillside and hidden from view by a strategic thicket. Petit-Gervais wouldn't have found it at all save for the slight break in the vegetation that signaled a path branching off of the main road.

"Maybe a hermit," he said aloud in his own language. The marmot chittered unhappily on his back and Petit-Gervais laughed. "There's only one way to find out," he declared, and took the path.

It was not a hermit who answered Petit-Gervais' knock but a boy, no older than Petit-Gervais, with a mop of sandy hair falling into his eyes. His face, furrowed with wariness, cleared into honest surprise when he saw Petit-Gervais. "What were you doing out in the storm?" he asked, in French. He had an accent Petit-Gervais had never heard before.

"Trying to find shelter from it," Petit-Gervais said. "I'm Petit-Gervais. Can I come inside and dry off? I can make her dance for you." He half turned, showing off the marmot.

The boy considered this request, then nodded and stepped aside to let Petit-Gervais inside. "Welcome to my home," he said. "I'm called Jean-la-Liberté." This last pronouncement held a note of challenge.

Petit-Gervais burst out laughing. "What are you, a Revolutionist?"

"Yes." Jean-la-Liberty spoke stiffly, coldly even. He'd drawn himself up to his full height, barely taller than Petit-Gervais. "Is that a problem?"

Petit-Gervais shrugged. "It's all politics," he said. "King, no King, it doesn't affect me."

"Under the Republic we were free." His voice was still stiff. "Good men spilled blood to deliver us from tyranny."

"And I was robbed last week," Petit-Gervais countered, the insult to both pride and livelihood still fresh enough to sting. "Would the Republic have stopped that?"

Jean-la-Liberté hesitated. "All men were held to the same laws," he said finally. "A rich man who robbed you would be punished just as harshly as a poor one."

"Well this one wasn't rich," Petit-Gervais said. "So I guess it doesn't matter. Can I still come in?"

Jean-la-Liberté hesitated a moment longer, muttered something to himself that Petit-Gervais didn't catch, and nodded.

"Thank you," Petit-Gervais said.

It took a moment or two for his eyes to adjust to the gloom inside. When they did, Petit-Gervais saw a rough-hewn table, with crumbs liberally scattered across its surface, and two chairs. A bed sat in one corner, with a sort of chair on wheels next to it and a straw pallet on the floor at its feet. The other side of the room held a crude kitchen, more than Petit-Gervais and his comrades had had in Paris but less than what he remembered his mother having at home. Apart from a half loaf of bread sitting out, it didn't seem to have been used in a while.

"Are you on your own here?" Petit-Gervais asked, taking it all in.

Jean-la-Liberté nodded. "My teacher passed into the care of the Supreme Being two years ago."

"And you've been here ever since? Alone?" Petit-Gervais couldn't hide his horror at this prospect. All his life he had been in company, first among his family and then, in Paris, among his fellow migrants. Even the trip home had been mostly spent with others, fellow workers going home or rival urchins to be merrily insulted. To be alone seemed to him a fate almost worse than death. At least in Heaven you had company.

"I have the sheep." Jean-la-Liberté sounded defensive again, and this time Petit-Gervais' heart filled with pity. No wonder he was so prickly, with only sheep for company.

"Well I'm glad I came by then," Petit-Gervais said. He moved towards the hearth, where a smoldering fire gave off more heat than light. He swung the marmot cage off his back and set it down in front of the hearth, then held out his own frozen hands towards the warmth.

Jean-la-Liberté hadn't answered, and when Petit-Gervais glanced over he found the other boy looking at him with an odd expression. "What?" he asked.

"No one's been glad to come here in a long time," Jean-la-Liberté said finally.

Petit-Gervais shrugged philosophically. "There's a first time for everything," he said, and, for the first time, Jean-la-Liberté smiled.

They stayed silent for a time, Petit-Gervais drying off and Jean-la-Liberté watching him, until Petit-Gervais' stomach loudly reminded him of the other thing he'd been hoping to find that evening.

Jean-la-Liberty jumped. "I'm sorry!" he said. "I've been a bad host. Are you hungry?"

"Always," Petit-Gervais said cheerfully.

Jean-la-Liberté moved to the kitchen corner and took out half a loaf of bread and a piece of cheese. These he put on the table, then went back for a jug of something and two cups to complete the meal. He paused, as thought realizing something, and looked over at the marmot. "Does it..." he began.

"She eats what I do," Petit-Gervais assured him. Jean-la-Liberté relaxed.

"Will you join me for a meal?" he asked. Petit-Gervais, now warmly damp rather than soaked and frozen, did not need to be asked twice.

"Where are you traveling from?" Jean-la-Liberté asked as they sat. He tore off a piece of bread for himself and passed Petit-Gervais the loaf. It was several days old, by the feel of it, but nowhere near the hardest loaf Petit-Gervais had ever eaten. He took a piece for himself and passed part of it down to the marmot, who grabbed for it eagerly.

"Paris," Petit-Gervais said. He peered into the jug, found it to be filled with wine, and poured himself a generous serving. Through a mouthful of bread he added, "Do you want to hear about it?"

Jean-la-Liberté did, and so Petit-Gervais launched into stories, telling Jean-la-Liberté about living in the city, about the adventures he'd had and the fights he'd been in and, laughing at his own stupidity, about the bumbling mistakes he'd made when arriving as an ignorant four-year-old fresh from the mountains. Jean-la-Liberté was an avid listener. He asked questions at all the right times and was suitably impressed by Petit-Gervais' worldliness. He himself had never gone farther than his summer pastures, and his sheep were far less interesting companions than Petit-Gervais' fellows. After they'd finished eating, Petit-Gervais pulled out his hurdy-gurdy and the marmot, rejuvenated by warmth and food, danced willingly to its melody. Jean-la-Liberté laughed with delight at the spectacle. Eventually the last light of the fire sputtered out, and the two boys retired, pressed together to conserve warmth on Jean-la-Liberté's pallet, Petit-Gervais' ragged blanket added to the top for extra insulation.

*

Petit-Gervais woke late the next morning. The winter sun had already been up for an hour, melting the night's frost coat. His head ached from the undiluted wine and his throat felt scratchy from sleep, but he rose anyway. Jean-la-Liberté was nowhere to be seen, and so Petit-Gervais busied himself with redoing his pack, pausing often to wipe his nose with the back of his hand.

Jean-la-Liberté came back inside just as Petit-Gervais was finishing his packing. "You're awake!" he said. Then, seeing the packed bag, "You're leaving already?"

"Won't get anywhere if I don't," Petit-Gervais said.

"There's another storm brewing," Jean-la-Liberté said, frowning. "You'll be far from anywhere when it hits."

"Not much that can be done about that," Petit-Gervais pointed out.

"You could stay here until it passes," Jean-la-Liberté suggested. "The house is sturdy enough to keep out the weather."

It was a tempting offer. Still. "There's likely another storm tomorrow too. I can't stay here forever."

Jean-la-Liberté shook his head confidently. "It won't rain tomorrow."

"How do you know that?"

"The sheep."

Petit-Gervais considered this. He wasn't so far removed from his roots that he disbelieved in animals' ability to divine the weather, nor so used to life on the road to turn down a roof when one was offered. "All right," he said. "I'll stay."

They spent the day idly. Jean-la-Liberté, who had already been to see his sheep, fiddled with a half finished wood carving, while Petit-Gervais, less hungry than usual, tried to teach his marmot new tricks with some of his uneaten bread. As Jean-la-Liberté had predicted, thunder started booming in early afternoon, and soon enough they heard the sound of another downpour.

"Does it always do this?" Petit-Gervais asked as the rain pounded down like pelting stones.

"Often enough," Jean-la-Liberté said. "Why, how does it rain in your country?"

Petit-Gervais started to answer, then stopped, struck. "You know," he said, "I don't remember." Then, because this seemed unsatisfactory, he added, "In Paris it stays grey and raining for days. It turns the soot to mud."

Jean-la-Liberté made a face. "That sounds unpleasant."

Petit-Gervais shrugged. "You get used to it."

They lapsed into silence, Jean-la-Liberté going back to his carving and Petit-Gervais staring at the fire. He hadn't thought much about what it would be like to go home. He'd known he would, of course, if his work didn't kill him or cripple him first, but it had always been an abstract thought. Home was a legend kept alive by boys who hadn't seen their villages since they were five or six, or by men who'd left for Paris at that same age and never gone back. Petit-Gervais carried the name of his village in his mind like a talisman, but it wasn't much more than a name. If he concentrated, he could recall his mother's face; he'd lost her voice long ago.

At last, Jean-la-Liberté broke the silence. "If I wasn't a shepherd, I'd go to Paris." From his tone, Petit-Gervais wasn't the only one whose thoughts had turned maudlin.

"What does being a shepherd have to do with it?" Petit-Gervais asked. "Surely there are others who could take your sheep."

"I have no other trade," Jean-la-Liberté said. "I can't very well herd a flock down the boulevards."

"There's plenty who'd pay to see that," Petit-Gervais said, grinning as he pictured it. Jean-la-Liberté didn't smile, and Petit-Gervais sobered. "You could learn a trade. You're too old for the chimneys, but you could apprentice to someone." He nodded at the piece of wood in Jean-la-Liberté's hands. "Carpenters take on boys your age."

Jean-la-Liberté snorted. "This? It's taken a year just to get this far. My teacher tried, but I have no talent for artisanry."

"Then what can you do?"

"I can mind sheep. I can read and write French. I can make cheese." He sounded disgusted with what, to Petit-Gervais, sounded like a perfectly reasonable skillset. Jean-la-Liberté grimaced when he said as much. "No one needs extra shepherds," he said. "Why would they take a foreigner when they have plenty of their own to mind their flocks?"

"Why leave here if you don't have to? You have a home, a livelihood, I'm sure you'll be able to find a wife without too much trouble when you want one. Are you restless?"

Jean-la-Liberté snorted. "I couldn't find a wife here," he said.

"Are all the girls around here really that ugly?"

"It's not that." Jean-la-Liberté sighed. "I suppose you might as well know. My teacher was a member of the Convention."

He spoke the word as though it ought to be self-explanatory, but Petit-Gervais only frowned. "Of... shepherds?"

Jean-la-Liberté stared at him. "This isn't a joking matter," he said, tone somewhere between severe and hurt.

"I'm not, but I also don't know what you're talking about. What Convention?"

"The Revolution? The Assembly of Citizens?"

Petit-Gervais shook his head.

Jean-la-Liberté seemed stunned. "But... you were in Paris!" he said.

"I told you, politics don't make any difference to me," Petit-Gervais said. He was beginning to regret pursuing this line of conversation.

"In 1789, as reckoned by the old calendar, the people rose up against tyranny," Jean-la-Liberté said. He sounded as though he were reciting a lesson learned by heart.

"I know that," Petit-Gervais said, although he wouldn't have been able to name the year, in any calendar. Jean-la-Liberté ignored him.

"Having freed themselves, the people formed their own government, headed by a Convention of elected citizens, who..."

"They killed the King!" Petit-Gervais interrupted, having finally figured out where this was going. "Your teacher was a King killer!"

"He wasn't!" Jean-la-Liberté snapped, his voice slipping back into its normal cadence. "Anyway, the King was plotting to overthrow the Republic!" He scowled. "I shouldn't have told you. You're no better than anyone else."

"Why did you tell me then?" Petit-Gervais demanded. His headache had intensified throughout the day rather than fading, and he had no patience to spare for Jean-la-Liberté's defensive streak. "How did you think I was going to react? And what does this have to do with not getting married?"

"Because everyone here also knows," Jean-la-Liberté said. "And they don't want anything to do with me."

This brought Petit-Gervais up short. "Oh."

"You understand now?" Jean-la-Liberté asked. He reminded Petit-Gervais of a threatened street cat, fur all puffed up to disguise how skinny it really was.

"I understand," he said. "But why do you expect anywhere else to be different? Will you change your name? It does give you away, you know."

"Of course I won't! But I thought maybe Paris remembered better. The peasants here don't know anything. Even the Bishop, the one everyone loves, he never came here until my teacher was dying, and all he did was insult us."

This, to Petit-Gervais, seemed about right for a Bishop, but that didn't feel like the right thing to say. He stayed silent.

"I thought Paris would be different. But you've just come from there, and you're just like the peasants."

"I am a peasant," Petit-Gervais said, mildly affronted. Then, because he was starting to like Jean-la-Liberté despite his prickliness -- and because Jean-la-Liberté was letting him stay in his home -- he added, "Although I'm not upset that he was a King killer. I was just surprised."

Jean-la-Liberté laughed a little. "He voted no," he said. "But thank you." They lapsed back into silence. When conversation started up again, it was about the weather.

#this fcking book though#achievement unlocked: completed piece of fiction#it's not a complete fic#but that's the tag#petit gervais

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Although this chapter ends on a hopeful note, Hugo really makes us suffer to get there. This line in particular really got to me:

“And her mother [saw her], no doubt, alas! For there are things that make the dead open their eyes in their graves.”

Cosette’s trauma is ever-present here, not just in what she’s doing (being sent to carry such a large bucket of water on a cold night is certainly traumatizing in itself), but in how she approaches it. Hugo notes that “it was her custom to imagine the Thénardier always present,” and we see that her fear of her is what drives her to continue. It’s heartbreaking to know that she can’t escape her even outside of the inn, underscoring the extent of her trauma. Additionally, Cosette is able to get the water without seeing where she is or what she’s doing. It’s become instinctual, highlighting how often she’s had to do something similar.

Cosette’s specific working conditions also remind me of Champmathieu’s daughter (who died young of abuse and overwork). In his testimony, he noted that her work meant she was either constantly working in cold water or in extreme heat, only to return home to her husband’s abuse. The cold water aspect is certainly shared (even if through different forms of labor), and knowing that an adult woman died of those conditions stresses how dangerous this is to Cosette. We also specifically know that, like Champmathieu’s daughter, she doesn’t have a safe and restful home environment to return to; the Thénardiers make “home” worse than the forest in many ways. And just as Champmathieu’s daughter was worn down by all of this until it killed her, so has Cosette - an eight-year-old - become like an “old woman,” her constant labor and stress prematurely aging her (Hugo says this here to describe the way she walks while carrying the bucket, but he said this about her general demeanor in a previous chapter; the repetition suggests it’s relevant).

The nature descriptions in this chapter are interesting on their own, but this line in particular drew my attention:

“The nettles seemed to twist long arms furnished with claws in search of prey.”

Nettles are associated with convicts in general and Valjean in particular because of his nettle speech as Père Madeleine. Moreover, another time when plants were described as having arms was the aftermath of Valjean robbing Petit Gervais, creating some parallels between that scene and this one.

Spoilers below:

Knowing that Valjean is the one who rescues Cosette from this suffering, we get a mini-redemption of sorts; the arm-like branches of Petit Gervais being wronged are now met with the good he does for Cosette. I don’t like the idea of Valjean needing to “redeem” himself in general (of his two real crimes - stealing from the bishop and stealing from Petit Gervais - one was automatically forgiven, and he does so much to compensate for the other that it feels cruel to demand redemption), but given that he feels so much guilt over this, it’s nice that this link provides a sense of closure.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

LM 1.2.13 History Notes: Petite Gervais, and Savoyards

Haven't seen this in the tags, and I still think it's really interesting context, so here, have a post about Petit Gervais before he's completely Gone from our narrative!

(note: this is largely taken from Graham Robb's The Discovery of France: From the Revolution to The First World War , a book I definitely recommend to anyone wanting more French History Context!):

Petit Gervais is definitely a chimney sweep. Hapgood's translation cuts that specific phrase out (others leave it in!), but to someone in Hugo’s era, even without the specific mention of him being a chimneysweep, it would be obvious that was his line of work, because that’s what migrant Savoyard boys were. Every year, a large migration of new kids headed north, towards Paris. When they got there:

...they split up into village groups. Each had its own dormitory and canteen. A Spartan building in a particular street might look like a part of Paris when in fact it was a colony of Savoy controlled by a Savoyard sweep-master. The master might also sell pots and pans or rabbit-skins and keep an eye on the boys as they went about the city shouting “Haut en bas!” (”Top to bottom!”). If a boy stole money or misbehaved, he was punished according to Savoyard traditiion. Boys who fled into the back streets were always found; chimney sweeps knew the city as well as any policeman and better than most Parisians…

The sweeps who avoided asphyxiation, lung disease, and blindness, and who never fell from a roof, might one day set up on their own as stove-fitters. Nearly all of them returned home to marry. Their tie to the homeland was never broken. When he emerged from the chimney onto the roof of a Parisian apartment -block, a Savoyard sweep could always see the Alps.”

- Graham Robb, The Discovery of France

So Petit-Gervais– and other Savoyard children like him (it was supposed to be just boys, but of course some girls joined too, with all the extra risk that entailed) isn’t just a randomly wandering parentless kid. He’s a boy learning a trade, and he’s either off to Paris to essentially serve his apprenticeship, probably working for his money along the way, or coming back home from Paris. Given how young sweeps were when they aged out of the job (only REALLY little kids can fit in chimneys, after all) and how much money Gervais is carrying, I’d *guess* he’s on the way home from the big city, but it could be seen either way.

Anyway, point being, Petit-Gervais isn’t some Random Encounter with a poor kid; he’s part of an organized child workforce, with parents who probably lived through the same thing--a workforce that took on an enormous amount of risk, as Hugo shows, however cheerful they might be.

#les mis letters#Petite Gervais#LM 1.2.13#Savoyards#not gonna get emotional on this post!! not this time!!#Les Mis

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

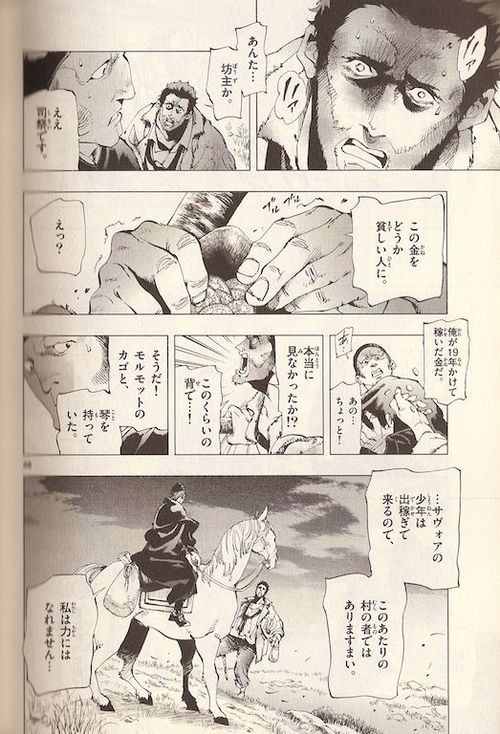

For Les Mis Chapter 1.2.13, FMA calls the little Savoyard boy "Petit Gervais." In Denny, he's "Petit-Gervais." My Japanese Brick has him as プチ•ジェルヴェ (transliteration "Puchi Jeruve," a way of phonetically writing out "Petit Gervais"), Arai has him as プティー•ジュルヴェー (transliteration "Putii Juruvee," a different attempt at phonetically rendering "Petit Gervais"). And Hapgood has Little Gervais because she is full of choices sometimes.

Arai interprets this chapter from pages 219–254 of his manga (English translation pagination), and is the only adaptation I can think of that has Valjean run up to the priest riding by to go, "OMG HAVE YOU SEEN A KID NAMED PETIT GERVAIS? WITH A HURDY-GURDY? I AM A CRIMINAL PLEASE HAVE ME ARRESTED AND HERE IS SOME MONEY FOR YOUR POOR."

Also! if you're wondering what a "hurdy-gurdy" is, it's a very real string instrument.

youtube

You can actually see the one Petit Gervais is carrying in Arai's manga very briefly.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

"As he was leaving Hesdin, he heard a voice crying out, 'Stop! Stop!' He stopped the carriole with a hasty movement, in which there was still something strangely feverish and convulsive that resembled hope.

It was the woman's little boy.

'Monsieur,' said he, 'it was I who got the carriole for you.'

'Well!'

'You haven't given me anything.'

He, who gave to all, and so freely, felt this claim was exorbitant and almost odious.

'Oh! It's you, beggar!' he said. 'Nothing for you!'"

Sorry this is really giving me Petit Gervais parallels. Same with how him stopping at the inn is like a sort of twisted contrast to him traveling at Digne.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy valjean dissociation day (:

#it happens during the petit gervais scene too but this is the longest one I think#les mis letters#les mis 1971#love this chapter#it's so GOOD ugh#I want to give valjean a hug :(((

8 notes

·

View notes