#philippe le bas

Text

i finally have a day off which means i get to draw Le Bas as a treat

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Original picture

#french revolution#frev#frev memes#almost half of these people are not even from pas-de-calais#but still#so... let's start the list#gracchus babeuf#philippe le bas#philippe lebas#joseph le bon#joseph lebon#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#antoine quentin fouquier-tinville#fouquier-tinville#martial herman#augustin robespierre#charlotte robespierre#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#louis antoine saint just#saint just#saint-just

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

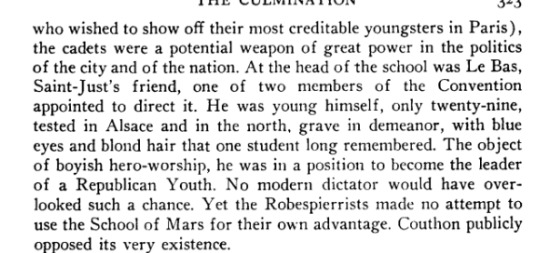

Friendly reminder that LeBas was more than "SJ's friend" and himself was an accomplished Conventionnel who was a member of the CGS, and for a very short time, was co-director of the republican boys' military school (School of Mars) (a very Spartan element of the year 1794, opened on the eve of and was shuttered soon after Thermidor)

For more info see R.R. Palmer's Twelve Who Ruled (1941). Although dated, this book is still a pillar in frev studies today. For those curious, Barère was also involved in advocating for the school, whilst Couthon was publicly opposed to it.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

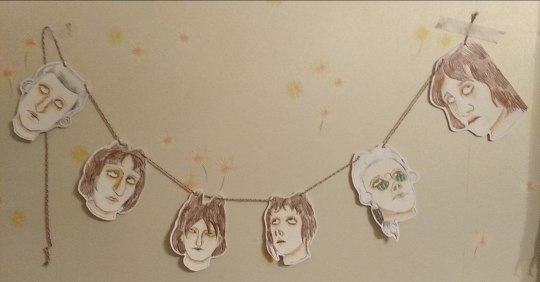

These are the times that I wish I was better at drawing, but here is this.

Saint-Just, Le Bas and Robespierre Thermidor sadness once again.

Inspired by the painting “Courage, Anxiety and Despair: Watching the Battle” by James Sant (pictured below)

When I tell you the immense love and admiration I have for this painting, it can not be measured.

#frev#french revolution#claws out for the main 5#claws out for robespierre#robespierre protection squad#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#louis antoine de saint just#saint just#philippe le bas#le bas#frev art#thermidor#courage anxiety and despair: watching the battle

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

JACOBIN FICTION CONVENTION MEETING 33: MADEMOISELLE REVOLUTION (2022)

1. The Introduction

Well, hello there, my dearest Citizens! Welcome back to Jacobin Fiction Convention! I missed you but, unfortunately, real life ™️ was a bit complicated yet again.

Either way, I’m back at it again, roasting analyzing historical fiction. Today’s “masterpiece” was graciously sent to me by @suburbanbeatnik in PDF form as a future review subject. And boy is it one hell of a ride.

Now, on paper, I was intrigued by a story of a Haitian biracial bisexual female protagonist, as there are many possibilities for that kind of story to unfold in a Frev setting.

Besides, it was written by an author who is promoting the #OwnVoices stories, which is a good intention in my opinion. Let’s see if the execution matches though.

(Spoiler alert: IT DOES NOT!)

Unfortunately, it looks like the book is only available in English at the moment and has to be purchased, mainly through Amazon. But maybe both of those things are for the best, since, upon finishing the book, I will be happy if it stays as contained and inaccessible to the wide audience as humanly possible.

Why? Well, more on that later.

This review will be longer than the ones I usually post, so please keep that in mind and grab some popcorn.

Also, it’s a very explicit book with scenes of sexual assault and gore. Goya’s “Disasters of War” and even “Innocent Rouge” levels of gore. So yeah, please be warned.

Anyway, this review is dedicated to @suburbanbeatnik , @jefflion , @lanterne , @on-holidays-by-mistake and @amypihcs . Love you, guys!

Now, let’s tear this sucker apart!!!

2. The Summary

The book follows the story of Sylvie de Rosiers, an aristocratic young woman born to a slave but raised by her plantation owner father as a free member of local nobility. Although not enslaved, Sylvie never felt truly accepted by the elites of Sainte Domingue.

However, following the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution, Sylvie and one of her half-brothers manage to escape to France, where another revolution is unfolding.

Intrigued by the ideas of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity, Sylvie must fight to find acceptance in this new context and carve out a place for herself.

Sounds interesting so far, right? Let’s see if the story lives up to expectations or not.

3. The Story

I have to admit that the first few chapters, the ones taking place on Haiti, were actually pretty good, or at least not bad. The pacing was good, the storyline building up to the uprising made sense and the introductions of the characters and the world building were fine.

Too bad that this lasted only for about four beginning chapters. The French chapters making up the bulk of the book were awful.

The characters suffer from assassination like they’re mafia snitches, the pacing turns into a speed run, the historical context isn’t explained well at all and the story rapidly stops making sense:

First Sylvie arrives and quickly meets Robespierre and the Duplay family, then becomes an ardent revolutionary, then flip flops between loving Eleonore Duplay and pining for Robespierre, then just so happens to meet Danton and Marat, then becomes a spy, then murders Marat… No, I’m not joking.

All of this is in the book with very little justification that makes sense. The worst part? The book isn’t stated as alternative history, so the author is very dishonest and presents everything in the book as actual history that is accurate to reality when it’s definitely not.

Oh, and flashbacks. The fucking flashbacks breaking immersion like a cat breaking a vase don’t help at all.

There’s also a ton of Thermidorian propaganda as well, so yeah… Fail.

4. The Original Characters

Let’s tackle the OCs first because the historical peeps deserve a separate category here.

First and foremost, I don’t like Sylvie as a character. She starts out as a vain spoiled brat growing up surrounded by privilege and luxury and openly looking down on slaves, especially on women.

Then she witnesses the execution of a rebel and very suddenly goes: “Fuck, slavery is awful!”, renounces her old ways, disowns her father and does a 180. It’s not written well though and is more like a teenage tantrum than character development.

Sylvie keeps flip flopping like this throughout the entire story too. Yay…

Oh, and she’s a Mary Sue. Everyone adores her except the villains, she’s able to charm her way through anything and obviously plays an important role in almost all of Frev! Robespierre even calls her The Mother of the Revolution at several points, even though she did nothing to earn that title.

She also pines for Robespierre for no reason at all, except for “he’s cool and charming I guess”, but in order to get closer to him, Sylvie Sue ™️ starts an intimate relationship with Eleonore Duplay.

So yeah, our protagonist manipulates another person (which is abuse) and plays Eleonore like a fiddle, but she also flip flops between only using Eleonore and actually loving her. Is Sylvie ever called out for that? Technically yes, but it gets resolved too quickly so it doesn’t count.

Also, Sylvie is INCREDIBLY selfish. She’s fine with manipulating Eleonore, fine with Charlotte Corday being executed for killing Marat (in the book Sylvie did it) and taking the blame… Again, everything revolves around Sylvie and she never gets called out on that either and never gets better.

She lacks consistent personality aside from those traits, however. She claims to want safety yet always takes the risky option and refuses to emigrate when it would help her obtain actual safety, for instance.

Gaspard, one of her half-brothers, is a much better character in my opinion, but still underdeveloped. But at least his journey from privileged fop to a revolutionary is less clunky. Too bad he dies with the Montagnards in the end.

Sylvie also has another half-brother, Edmond, who is cartoonishly evil and tries to murder Sylvie at one point.

Sylvie also has a standard issue evil stepmother who is eager to marry her off and thus get rid of her but at least has enough decency to not be actively malicious.

Her dad is loving, but painfully ignorant.

Sylvie’s aunt Euphemie de Rohmer is a good character, always looking out for Gaspard and Sylvie. She does emigrate to London during the reign of terror though.

Okay, now let’s discuss the historical figures.

5. The Historical Characters

I know that I usually don’t discuss accuracy, but an exception must be made here.

Maximilien Robespierre seems to undergo a typical “character arc” of “actual revolutionary turned ruthless dictator”. He is also one again coded as asexual and thus shown as not giving two shits about his lover, Eleonore Duplay. He tries to marry Sylvie for political reasons only later in the book and it’s all but stated that he condones all the violence going on and is called a hypocrite multiple times. Oh, and he also kisses Sylvie without her consent… Err… DID SIVAK CONFUSE HIM FOR DANTON?!!! Okay, one sec…

(Shows up with a bloody face) Okay, let’s continue…

Eleonore Duplay is a promising artist who is fiercely loyal to Robespierre but cheats on him with Sylvie and later turns out to be a member of a women’s secret society that is trying to curb the terror. She’s on board with murdering Marat and is also friends with Olympe de Gouges and Charlotte Corday. Wtf?!

(Checks that the antidepressants didn’t cause a hallucination)

Elisabeth Duplay falls in love with Gaspard and her marriage to Le Bas is portrayed as arranged by Robespierre to “reward” Le Bas for being a loyal Jacobin, but at least she is relatively happy in said marriage. Uhm, okay…

Olympe de Gouges and Charlotte Corday are portrayed as basically saints and also part of the secret society.

Corday in particular is willing to sacrifice herself for the sake of France and Sylvie is fine with that because, apparently, Corday has nothing to live for anyway but Sylvie does.

It’s not like in reality Corday actually had a family and Girondist friends or anything so yeah, TOTALLY OKAY to throw her under the bus amirite?!

Danton, luckily, is portrayed fairly accurately as a crass womanizing brute so at least that’s correct.

Marat is a stereotypical bloodthirsty monster who is supposed to be very smart yet acts like an idiot in the presence of our dear Sylvie Sue.

Charlotte Robespierre makes exactly one cameo and acts like a total ass to both Duplay sisters and to Sylvie (who she just met). Don’t get me wrong, Charlotte was at odds with the Duplay family but not all of them and certainly she wasn’t a bitch to every single fucking stranger.

Augustin Robespierre is merry, a gentleman, loyal to his ideas but also a part of that secret society and also supports the idea of offing Marat. Nice…

Surprisingly, Henriette Robespierre makes a cameo alongside Charlotte and also acts like an ass but at least less so than Charlotte. Except she shouldn’t even be in the book because the cameo happens in 1792, yet Henriette died in 1780. So it’s either a ghost or the author doesn’t care. I’m kind of inclined to believe the latter.

Where are Camille Desmoulins and Saint-Just, you may act? ABSENT, believe it or not! No, I’m not kidding! They’re nowhere to be seen for some reason!!! I have no idea why. They’re not even fucking mentioned!!!

Anyway, let’s move on before I lose my sanity.

6. The Setting

Again, the first chapters are much better than the rest. In the majority of the book the descriptions are not that great and the world building is laughably inaccurate, to the point that, if I were told that it’s a joke fanfic, I’d have believed it instantly!!!

7. The Writing

Thankfully, there’s no “First Person Present Tense” bullshit, but the writing is still full of problems. The aforementioned flashbacks are just one problem, but there are others.

For example, extremely clunky use of French. I’m the beginning of every chapter we get a date and the months are in French. This would’ve been fine but gets ridiculous in cases like “early avril 1793”. What’s wrong with writing “early APRIL”?!

Oh, and in another instance, the houses of families are called “Chez + Family name”, like Chez Rohmer and Chez Marat. It gets weird when the text has phrases like “went at Chez Marat”. Chez already means “at” in this context, so it’s extremely redundant and a damn eyesore. Wouldn’t it be better to say “Went to Marat’s apartment”? Apparently, not for Zoe Sivak!

Also, the author describes all the brutal and gory scenes of executions and torture at an alarming length and with a concerning amount of details, to the point that I got very uncomfortable despite not being squeamish most of the time.

8. The Conclusion

Phew, it’s finally over. As you may have guessed, I don’t recommend wasting your time and money on this pile of trash.

A 13-year old here on tumblr can write a better novel than whatever the fuck this author published.

It’s poorly researched with inaccuracies that even a quick Wikipedia search could fix, the protagonist is an awful Mary Sue, the historical characters get constantly fucked over… so yeah, please skip this shit.

Anyway, on that note, let’s conclude today’s meeting. I think I might need time to recover from reading this book…

Stay tuned for updates!

Love,

Citizen Green Pixel.

#obscure frev media#frev media#frev books#jacobin fiction convention#mademoiselle revolution#french revolution#haitian revolution#charlotte corday#charlotte robespierre#henriette robespierre#augustin robespierre#maximilien robespierre#elisabeth duplay#eleonore duplay#philippe le bas#jean paul marat#georges danton

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

I always wanted to see this meme on frev boys and finally it is here ✨✨✨✨

Original meme

#frev community#frev art#frevblr#robespierre#frev#my art#camille desmoulins#fun#louis antoine de saint just#fabre d'eglantine#bonbon#marat#philippe#philippe le bas#bonbon robespierre#saint just#Camille#camille's arm :)#memes image#meme#french revolution

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Just, Robespierre, bon bon, Camille, Philippe Le Bas, George Couthon

#camille desmoulins#french revolution#frev#french#robespierre#saint just#couthon#bon bon#Philippe Le Bas

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

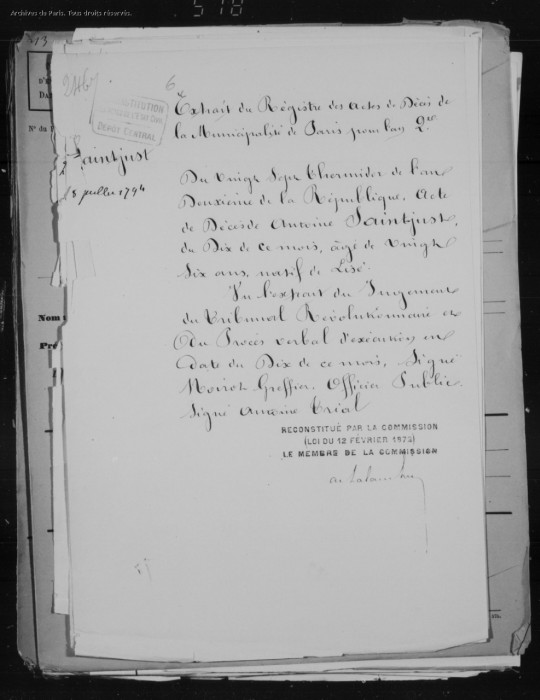

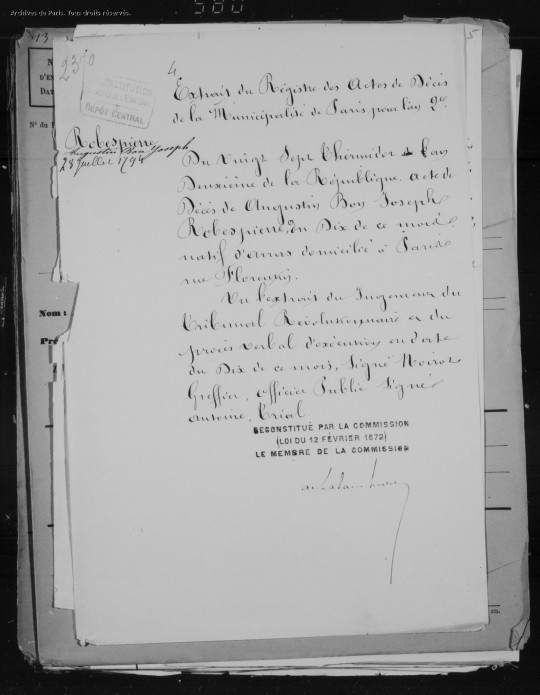

10th Thermidor Death Records

I had no idea that we had copies of reconstructed death records for Robespierre, SJ, Couthon and others executed on 10th Thermidor (also Le Bas).

Robespierre:

Saint-Just:

Couthon:

Augustin Robespierre:

Le Bas:

Source

Couthon: page 6 of the above file / Le Bas: pages 22-23 / Saint-Just: page 27 / Robespierre: page 28 / Augustin Robespierre: page 29

The file also has records of the others executed on the same day.

(Stay tuned for Dantonists)

94 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, in a recent post you mentioned that we have Philippe Le Bas' passport (or just its text?) Do you maybe have a source for the full text/do you know what it said? I'd love to read the rest of the description.

Yes! Paul Coutant, alias Stéfane-Pol, published two passports for Le Bas in his Autour de Robespierre : Le Conventionnel Le Bas, and I would be surprised if there aren’t other passports for him at the National Archives as well, as a representative on mission. NB: It seems I misremembered his height. Le Bas was only 5 pieds 5 pouces; in other words, around 176 cm.

The published ones read as follows:

ÉGALITÉ, LIBERTÉ.

Au nom de la Nation.

Département du Pas de Calais, district de Saint-Pol, municipalité de Saint-Pol. Laissez passer Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas, homme de loi et député pour la Convention nationale, citoyen français, domicilié à la municipalité de Saint-Pol, district du même lieu, département du Pas-de-Calais, âgé de vingt-huit ans, taille de cinq pieds cinq pouces, cheveux et sourcils châtains, yeux gris-bleu, nez court un peu retroussé, bouche petite, menton rond, front large, visage ovale ; et prêtez-lui aide et assistance en cas de besoin.

Délivré à la maison commune le 15 septembre 1792, l’an IV de la Liberté.

&

La loi.

Laissez passer le sieur Philippe Le Bas, français domicilié en la ville de Saint-Pol, département du Pas-de-Calais, district de Saint-Pol, âgé de vingt-huit ans, taille de cinq pieds cinq pouces, cheveux et sourcils châtains, yeux gris, nez élargi, bouche moyenne, menton long, visage ovale, front haut ; et prêtez-lui aide et secours en cas de besoin.

Donné à Frévent, même département et district, sous notre signature et la sienne, le seize septembre mil sept cent quatre-vingt-douze, l’an quatre de la Liberté, le 1er de l’Égalité.

Which back in my LJ days, when I still did (admittedly rather mediocre) translations, I translated like this:

EQUALITY, LIBERTY.

In the name of the Nation.

“Department of Pas-de-Calais, district of Saint-Pol, municipality of Saint-Pol. Let pass Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas, man of law and deputy for the National Convention, French citizen, domiciled in the municipality of Saint-Pol, district of the same place, department of Pas-de-Calais, aged twenty-eight years, height five feet five inches, chestnut-brown [châtain] hair and eyebrows, grey-blue eyes, short- and slightly snub-nosed, small mouth, round chin, large forehead, oval face; and lend him aid and assistance in case of need.

Delivered to the maison commune on 15 September 1792, Year IV of Liberty.

&

The law.

Let pass the sieur Philippe Le Bas, Frenchman domiciled in the city of Saint-Pol, department of Pas-de-Calais, district of Saint-Pol, aged twenty-eight years, height five feet five inches, chestnut-brown [châtain] hair and eyebrows, grey eyes, broad nose, medium-sized mouth, long chin, oval face, high forehead; and lend him aid and help in case of need.

Given in Frévent, same department and district, under our signature and his, the sixteenth September seventeen ninety-two, year four of Liberty, the 1st of Equality.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

🥰

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh jesus christ mye yes hurt

but um. bonbon birthday!!! ft. him but no wig 🤯 and a le bas design (omg)

FINALLY frevposting for real...

#BONBON LOOKS LIKE ONE OF MY OCS IM KMS#i would change the hair but god forbid i try adding more onto this i am in so much pain#uhh.#enjoy my designs i guess? HELP#THEYRE BOTH SUPPOSED TO BE BLOND BUT MY COLORING MAKES IT LOOK WEIRD OMFG... GR#ok enough of this. Enough#things i have committed#frev#augustin robespierre#philippe le bas#do not kill cringe but kill the part of you which cringes

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like SJ and Le Bas would have this kind of matching earrings; wherein one has to wear one earring from a pair of earrings, and the other would wear the other earring.

Idk if anyone thought about this.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

In memoriam.

And many others.

#augustin bon robespierre#georges couthon#philippe le bas#louis-antoine saint-just#jean-baptiste fleuriot lescot#françoise duplay#french revolution#révolution française#thermidor

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

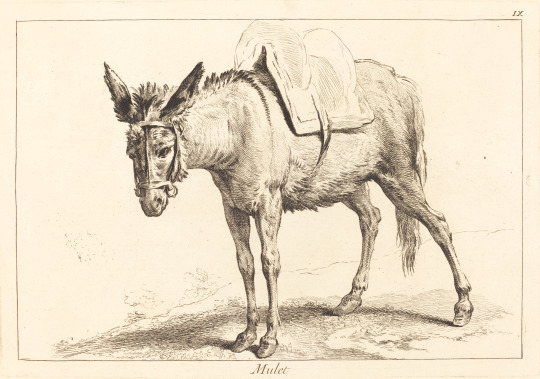

Mule, Jacques-Philippe Le Bas and Jean Eric Rehn after Jean-Baptiste Oudry, 18th century

#art#art history#Jacques-Philippe Le Bas#Jean Eric Rehn#Jean-Baptiste Oudry#animals in art#mule#mules#pack animals#animalier#print#etching#engraving#Rococo#French art#18th century art#National Gallery of Art

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outlander except it’s frev and I’m simply traveling back in time to introduce them to tumblr, minecraft and 2023 college Anatomy and Physiology tests.

#and also to pick their brains and psychoanalyze them.#and also to introduce Saint Just to The Phantom of the Opera because I think he’d enjoy that.#frev#french revolution#claws out for the main 5#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#louis antoine saint just#saint just#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#jean paul marat#marat#georges danton#danton#charlotte robespierre#augustin robespierre#lucile desmoulins#philippe le bas#elisabeth duplay#therese gelle#robespierre protection squad#claws out for robespierre#lucie likes history#ktfatl

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

UN DÎNER AVEC JULES SIMON ET CHARLOTTE ROBESPIERRE

Here is (finally) the anecdote as recorded by Jules Simon, followed by the summary given by Lenôtre, and the interpretation Coutant makes of it from the latter. Also some of my annotations coming from the part of my thesis where I reproduced the anecdote. (It's all in French obviously so anyone feeling brave enough to translate to English is more than welcome!)

(Source: Jules Simon, Premières années, Paris, Flammarion, 1901, p. 181-187.)

[…] C’est par un universitaire que je fus vraiment introduit dans le monde républicain. M. Philippe Le Bas, mon professeur d’histoire à l’École normale, m’accueillit chez lui, et me fit accueillir dans quelques familles restées fidèles aux souvenirs de 1793[1].

C’était le fils du conventionnel Le Bas, ami et disciple de Robespierre. Il était fier de la renommée de son père. On raconte même qu’avant d’être membre de l’Institut, il se faisait annoncer dans les salons sous ce titre : « M. Philippe Le Bas, fils du conventionnel ». J’avais désiré voir de près des survivants de la Révolution : mon succès dépassait mes espérances, puisque je me trouvais d’emblée dans le monde de Robespierre. J’étais comme un jeune débutant qui aurait voulu goûter d’un vin généreux, et à qui on aurait versé abondamment de l’alcool. J’avais assez de fermeté pour m’accommoder à peu près des Girondins, mais je fus sur le point de perdre l’esprit en me trouvant au milieu des amis de Robespierre.

La veuve du conventionnel Le Bas qui accoucha quelques semaines après de celui qui devait être mon professeur, était une des filles du menuisier Duplay. Cette famille Duplay était devenue la famille de Robespierre. Il y demeurait ; il était, quand il mourut, fiancé de Mademoiselle Éléonore, la sœur de Mme Le Bas. La fiancée prit le deuil de Robespierre et le porta jusqu’à sa mort. Toute cette famille était étroitement unie, et le souvenir du grand mort ne contribuait pas peu à cette union. Le Comité de Salut Public, universellement condamné et maudit, avait encore quelques amis dans ce coin du monde ; et pour ces survivants, pour ces persistants, la famille Le Bas était l’objet d’un respect particulier.

Du reste, le menuisier Duplay avait donné à ses filles une éducation excellente. Ce menuisier était un entrepreneur en menuiserie ; il remplit pendant quelque temps les fonctions de juge au Tribunal révolutionnaire. Son petit-fils, celui qui fut mon maître à l’École normale, était l’homme le plus doux et le plus bienveillant du monde. Quand il n’avait plus à s’expliquer sur son père et les amis terribles de son père, il parlait et agissait en homme cultivé, ami de la paix, et préoccupé, par-dessus tout, de ses recherches d’érudition. Il avait été précepteur d’un prince. Il est vrai que ce prince était le prince Louis-Napoléon, celui-là même qui, contre toute attente, devint Empereur des Français. L’avènement de son élève au rang suprême ne changea rien ni aux idées de Philippe Le Bas, ni à sa conduite, ni à son langage, ni à sa vie. Il resta jusqu’à la fin tel que je l’avais connu en 1834, M. Philippe Le Bas, fils du Conventionnel.

On savait parmi les familiers de M. Le Bas, que je ne connaissais personne à Paris ; et c’était une raison pour eux de m’inviter à dîner ou à déjeuner le dimanche. Je fus invité une fois avec des formes solennelles et mystérieuses qui me donnèrent lieu de penser que j’allais assister à quelque événement d’importance. J’arrivai à l’heure dite. Il y avait quelques convives, tous républicains avérés et rédacteurs des journaux du parti. Près d’une heure s’écoula ; la personne qui avait donné lieu à la réunion se faisait attendre. Je pense que tout le monde, excepté moi, était dans le secret ; mais j’étais trop timide pour faire une question. Enfin un grand mouvement se produisit, la famille se porta tout entière dans l’antichambre pour rendre la réception plus solennelle, et nous nous rangeâmes autour de la porte, pendant qu’à côté de nous on échangeait des propos de bienvenue.

On n’annonçait pas dans cette modeste maison. Je vis entrer une femme âgée qui marchait péniblement et qui donnait le bras à la maîtresse de maison. Elle était venue seule. On la salua très profondément ; elle répondit à ce salut en reine qui veut être aimable pour ses sujets. C’était une femme très maigre, très droite dans sa petite taille, vêtue à l’antique avec une propreté toute puritaine. Elle portait le costume du Directoire, mais sans dentelles ni ornements. J’eus sur le champ, comme une intuition que je voyais la sœur de Robespierre. Elle se mit à table, où elle occupa naturellement la place d’honneur. Je ne cessai de l’observer pendant tout le repas. Elle me parut grave, triste, sans austérité cependant, un peu hautaine quoique polie, particulièrement bienveillante pour M. Le Bas, qui la comblait d’égards ou, pour mieux dire, de respect. Quand la conversation devint générale, elle y prit peu de part ; mais écouta tout avec politesse et attention. S’il lui arrivait de dire un mot, tout le monde se taisait à l’instant. Je me disais qu’on n’aurait pas mieux traité une souveraine.

Le nom de Robespierre ne fut pas même prononcé. Au fond, c’est à lui que tout le monde pensait, et c’est de lui qu’on parlait sans le nommer. C’était l’habitude dans ces familles dévouées. Je ne l’attribue à aucune appréhension de se compromettre en prononçant ce nom qui était là, révéré, et exécré partout ailleurs. On ne le prononçait pas, parce qu’il était sous-entendu dans tous les discours.

Il y a deux Robespierre : le Robespierre féroce et le Robespierre raisonneur et sentimental. Le culte de ses fanatiques s’adressait également au dictateur et à l’orateur humanitaire. Les revenants avec lesquels j’étais attablé n’appartenaient pas à 1834. Ils voulaient être, ils étaient de 1793. Les grandes tueries n’étaient pour eux que des actes nécessaires de gouvernement. À peine les Thermidoriens eurent-ils renversé le Comité de Salut Public qu’ils s’exercèrent à le copier. Au 18 Fructidor, La Réveillère-Lépeaux, le plus dur des hommes, déporta des Directeurs, des représentants et des journalistes à Sinnamari. Pendant un quart de siècle, la proscription fut dans les mœurs. Je crois bien qu’on excusait les tueries de 1793 autour de moi, que peut-être même on les glorifiait. Mais on pensait surtout au disciple de Jean-Jacques Rousseau, aux discours contre la peine de mort et sur l’Être suprême, à l’auteur de tant d’homélies attendrissantes sur la fraternité et la vertu. Je suis sûr que Charlotte le revoyait dans ses rêves, précédant la Convention à l’autel, le jour de la fête religieuse, en habit bleu clair et en cravate blanche, et portant dans ses bras une gerbe de fleurs.

Melle Robespierre avait soixante-quatorze ans lorsque je la vis. Je savais qu’elle avait passionnément aimé ses deux frères et que, quand Maximilien s’était installé chez les Duplay, elle s’était montrée irritée et jalouse. Elle faisait à ces nouveaux amis un crime de leur amitié. Elle allait jusqu’à prétendre qu’Éléonore avait employé la ruse pour se faire épouser. Elle vécut loin d’eux après la catastrophe. Le Premier Consul lui fit une pension de 3.600 livres, qui fut plus tard réduite de plus de moitié, mais qu’elle toucha presque sans interruption jusqu’à sa mort. Elle vivait de cette faible ressource dans un isolement absolu. Elle publia des Mémoires qui roulaient sur des événements connus, et ne piquèrent point la curiosité. Je suppose qu’elle consentit à laisser faire cette publication dans un moment de détresse[2]. Sans doute, elle avait voulu, aux approches de la mort, oublier son ancienne rancune. Elle s’était souvenue avec attendrissement d’une femme vénérable qui avait failli être la sœur de son frère. Elle avait voulu se rapprocher un moment de cet homme déjà célèbre, dont le père avait été le plus fidèle ami de Maximilien. Elle sentit enfin que ceux qui s’étaient rencontrés dans ces jours lugubres devaient être réunis dans le souvenir comme ils l’avaient été dans la vie.

Je croyais rêver et je rêvais en effet. Les deux femmes qui étaient là, quel que fut leur nom, avaient vécu dans l’intimité de Robespierre, écouté sa parole comme celle d’un pontife, admiré sa vie comme celle d’un héros et d’un sage. Les questions se pressaient en tumulte dans mon esprit, et je me demandais avec effroi si j’oserais interroger mon maître et si je ne me laisserais pas opprimer une fois de plus par ma maudite timidité.

Il me conduisit jusqu’à la porte pour me dire d’un air triomphant : « Comment la trouvez-vous ? » Je m’enfuis et je me dis tout en courant à travers les rues de Paris, que je n’étais pas à ma place dans ce monde-là. Tout, dans ce temple, était respectable, excepté le Dieu. J’eus le souvenir de mes morts et, en même temps, de ma haine[3].

Version rapportée par G. Lenôtre :

Un jour, écrivait-il, il y a quelques années dans un de ses articles du Temps, un jour que je déjeunais chez mon professeur d’histoire, M. Philippe Lebas, je vis entrer dans le salon une vieille demoiselle, bien conservée, se tenant très droite, vêtue, à peu près comme sous le Directoire, sans aucun luxe, mais d’une propreté recherchée. Mme Lebas, la mère (autrefois Mlle Duplay) et M. Lebas l’entouraient de respects, la traitaient presque en souveraine. Elle parla peu pendant le repas, poliment, avec gravité. « Comment la trouvez-vous ? me dit M. Lebas quand nous fûmes seuls dans son cabinet – Mais qui est-ce ? – Comment ? Je ne vous l’avais pas dit ? C’est la sœur de Robespierre. » J’étais alors élève de première année à l’École normale.

(Source : G. Lenôtre, Paris révolutionnaire, Firmin-Didot, Paris, 1895. p. 48.)

Version rapportée par Paul Coutant :

Charlotte Robespierre a davantage occupé l’opinion. M. Lenôtre, dans son dernier volume[4], lui a consacré tout un chapitre, et le fils du conventionnel Le Bas a tracé sa biographie, en quelques lignes qui détruisent, par leur sévérité, la portée d’une historiette racontée jadis par Jules Simon dans le Temps :

« Un jour que je déjeunais chez mon professeur d’histoire, M. Philippe Le Bas – dit Jules Simon – je vis entrer dans le salon une vieille demoiselle, bien conservée, se tenant très droite, vêtue, à peu près, comme sous le Directoire, sans aucun luxe, mais d’une propreté recherchée. Mme Le Bas, la mère, (autrefois Mlle Duplay) et M. Le Bas l’entouraient de respects, la traitaient presque en souveraine. Elle parla peu pendant le repas, poliment, avec gravité : « Comment la trouvez-vous ? me dit M. le Bas quand nous fûmes seuls dans son cabinet. –Mais qui est-ce ? –Comment ? Je ne vous l’avais pas dit ? C’est la sœur de Robespierre. » J’étais alors élève de première année à l’École normale. »

L’élève de première année à l’École normale fut, depuis, un homme éminent, un philanthrope remarquable, et pourtant il lui arriva de manquer d’indulgence pour ceux de ses anciens professeurs qui l’avaient accueilli, pourtant, avec bonté : le cœur étant excellent chez lui, j’aime à croire que la mémoire seule était en défaut ; rien d’étonnant à ce qu’elle l’ait mal servi lorsqu’il écrivit sa chronique.

« Charlotte Robespierre – dit Philippe Le Bas dans son Dictionnaire encyclopédique de l’Histoire de la France – ne rougit pas de recevoir des assassins de ses frères une pension qui, de 6,000 fr. d’abord, puis réduite successivement jusqu'à 1,500, lui fut servie par tous les gouvernements qui se succédèrent jusqu'à sa mort (1834). Elle a laissé des Mémoires qui contiennent de curieux renseignements, mais où le faux se trouve trop souvent mêlé au vrai. »

Je ne pense pas que le savant consciencieux qui traça ces lignes ait jamais traité Mlle Robespierre en « souveraine » : c’est « solliciteuse » qu’a voulu écrire Jules Simon.

Aussi bien, Charlotte Robespierre ne saurait m’intéresser que par les lettres ou souvenirs où elle a parlé de son frère Maximilien, et, sur ce point, le document que reproduit M. Lenotre a le plus grand intérêt, parce qu’il dissipe des malentendus copieusement utilisés par certains écrivains ; c’est le testament que voici, conservé dans les archives de Me Dauchez, notaire à Paris :

« Voulant, avant de payer à la nature le tribut que tous les mortels lui doivent, faire connaître mes sentiments envers la mémoire de mon frère aîné, je déclare que je l’ai toujours connu pour un homme plein de vertu ; je proteste contre toutes les lettres contraires à son honneur, qui m’ont été attribuées, et, voulant ensuite disposer de ce que je laisserai à mon décès, j’institue pour mon héritière universelle, Mlle Reine-Louise-Victoire Mathon.

« Fait et écrit de ma main, à Paris, le 6 février 1828.

« Marie-Marguerite-Charlotte DE ROBESPIERRE. »

On ne peut guère discuter la sincérité de ceux qui vont mourir.

(Source : Paul Coutant, Autour de Robespierre : Le conventionnel Le Bas, d’après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1901, p. 85-87.)

Annotations:

[1] Le souvenir de 1793 continue de lier plusieurs familles, dont la famille Le Bas-Duplay, comme l’écrit Florent Hericher, Philippe Le Bas (1794-1860), Un républicain de naissance, Paris, Librinova, 2021, p. 191, n. 276.

[2] Ce n’est pas tout à fait exact, vu la participation d’Albert Laponneraye au projet.

[3] Il est né à Lorient, en Bretagne, l’une des régions insurgée contre la Révolution et foyer de la Chouannerie. Le refus de la constitution civile du clergé (1791) et les tensions causées par la conscription du 15 août 1792 et la « levée de 300 000 hommes » décrétée le 24 février 1793 mènent à l’insurrection.

[4] Paul Coutant (Autour de Robespierre.., p. 85, n. 2) fait référence à l’ouvrage Vieilles maisons, vieux papiers (1900).

#jules simon#paul coutant#g. lenôtre#testimonials and commentaries#elisabeth duplay#philippe le bas fils#élisabeth duplay lebas#élisabeth duplay#élisabeth lebas#charlotte robespierre#19th century

17 notes

·

View notes