#post ww giffed interview

Photo

fidgety brandon

#the killers#brandon flowers#ronnie vannucci#imploding the mirage era#itm era#itm interview#itm giffed interview#we are really so content starved this low quality video is worth being giffed#also to oppress hannah of course#post ww hiatus#post ww interview#post ww giffed interview#gold buttons black suit#tan shirt#my gif

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Picnic against Harbor Drive: Neighborhood Associations and the Fight Against Freeways

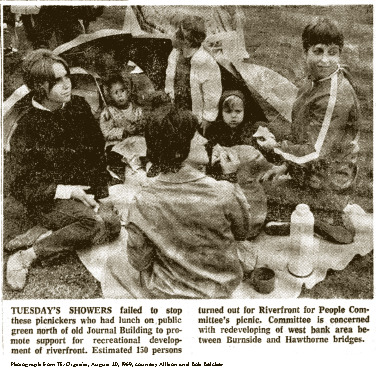

In his book “Portland in Three Centuries,” historian and PSU professor Carl Abbott writes: “On a summer day when the mountains and coast beckoned many Portlanders, 250 adults and 100 children spread their blankets and opened their coolers and baskets on a barren strip between four lanes of busy traffic on Front Avenue and an even busier four lanes on Harbor Drive.”

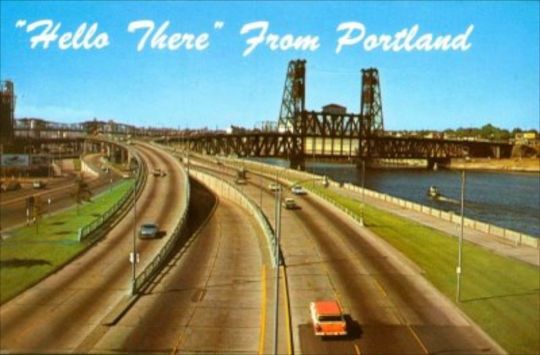

This postcard shows Front Street to the left, a grassy median, and Harbor Drive plus offramps. Steel Bridge in the background. From here.

The picnic took place on August 19th, 1969, organized by a fresh group of political activists. From the 1950’s through the 1970’s, traffic planners got a little highway crazy: a 1955 report by the Oregon Department of Transportation recommended the construction of 14 new freeways in the Portland Metro area. Even after Interstate 5 was constructed on the east side of the river, city planners wanted to expand Harbor Drive on the west side of the river, completely cutting off pedestrian access to the Willamette downtown.

Harbor drive no longer exists- today, we know of it as Tom McCall Waterfront Park. Though the park bears Governor McCall’s name, we can thank the efforts of a few civic-minded Portland families hosting a picnic on a busy median on a summer day. They called their group Riverfront for People.

Here’s a photo from one of the picnics. From here.

The picnic was the first of a number of such demonstrations over the course of that summer. The protest was organized by Allison Belcher and her husband Bob. Allison said, “I was ironing clothes, as was the wont of females to do of that time and I heard on the radio that the Highway Commission was going to put this road right down through where the Oregon Journal property was along the river, so I called up Ira Keller [chairman of the Portland Development Commission—one of the city’s most powerful, mercurial figures] on the telephone and I said, ‘what are you doing, why are you doing this?’ He said, ‘You shouldn’t be bothered—you’re just a housewife.’” This quote and many of the other quotes from the RFP organizers come from an excellent interview conducted by Tim DuRoche, here).

Allison started making phone calls, reaching out to people she had met through a shared interest in the upcoming 1970 City Council election. In the meantime, her husband Bob got in touch with his architect coworkers- folks interested in the historical preservation of west-side waterfront buildings and folks with a vision for a more vibrant Portland than the east side riverfront’s maze of concrete represented.

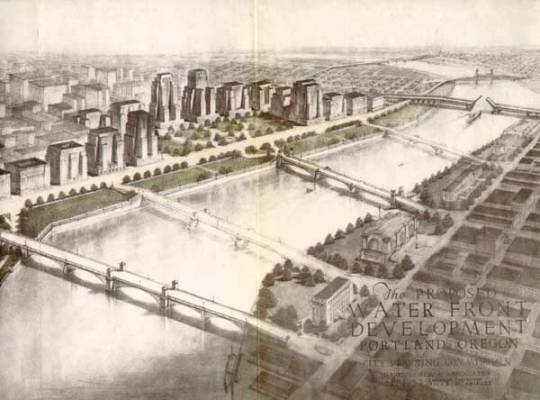

This is an image from a 1932 planning report by Harland Bartholemew. Notice the riverfront green space on both sides of the river. During the war, the eastside riverfront would be lost to industrial uses and freeway I-5. Notice the “city beautiful” style buildings. City of Portland Archives.

This gif from this bikeportland article shows ODOT’s proposal to widen I-5 along the eastbank of the river even further, creating a ridiculous overhang over the eastbank multi-use path.

The picnic worked. The Riverfront for People organizers got the attention of Governor Tom McCall, who, even before the picnics, had spoken about his hope of creating a public greenspace along the waterfront. The alliance between the regular folks- the 350 people who showed up to have summer picnics on a highway median- and the political establishment built a powerful coalition able to resist the 1970’s hunger for more miles of concrete.

However, despite their new and powerful ally, Harbor Drive wouldn’t officially close until 1974. That’s five years of difficult political work to achieve their goal. This political work helped inspire a new generation of citizen leaders in Portland politics. Carl Abbott writes: “The process of neighborhood planning between 1957 and 1967 was as straightforward as its content. City Planning Commission reports make no reference to neighborhood groups or citizen involvement. They were prepared by city employees for their colleagues in city hall.”

However, as part of the Harbor Drive campaign, Belcher and others began showing up to city hall meetings, demanding to have their opinions considered in the decisions that shape their city. Belcher said, “It was something new for Portland to go down to City Hall and testify—everything had always been run by these people who’d been in power for a long time and they didn’t discuss it with anyone. There really hadn’t been much change or access up to that point.” PSU professor Ernie Bonner notes that 120 people attended the January 14th, 1970 meeting of the State Highway Commission, where a closure date for Harbor Drive was officially set.

Harbor Drive helped usher in a new era of citizen engagement in local issues. Allison and Bob Belcher protested alongside Vera Katz (namesake of the Eastside Riverfront Recreational path) and Gretchen and Steve Kafoury (Parents to commissioner Deborah, and longtime political officeholders themselves) to demand that the City Club of Portland allow women as members. Bob Belcher: “What began with Model Cities and then Neil Goldschmidt coming on to Council … was part of this something wonderful that was happening in Portland of that time. It was post-Kennedy—there was a huge energy in the air … there was a lot going on, all that turmoil in Vietnam, but there was an underlying current of all these things on a national level. …Our great virtue was the times energized us—it was a hopeful time. We were pretty outraged and we were young enough that we thought we could make a big noise about this.”

Their ‘young outrage,’ ability to build connections with establishment politicians like McCall, and savvy campaigns for councillors Anderson, McCready, and Goldschmidt would create the initial energy required to defeat the proposal for the Mt. Hood Freeway when it came up in 1975, and would then help to divert the funds necessary to create the first branch of the MAX light rail line in the metro region. Activists were also successful in defeating a plan to build a 12-story parking garage on the site that is now Pioneer Courthouse Square.

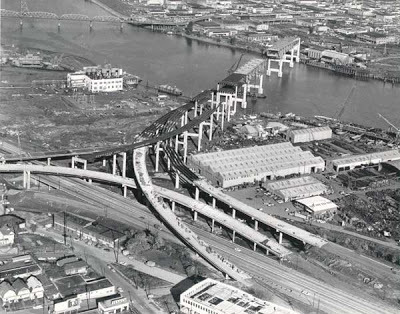

A picture from the early days of the Marquam Bridge. Photo here.

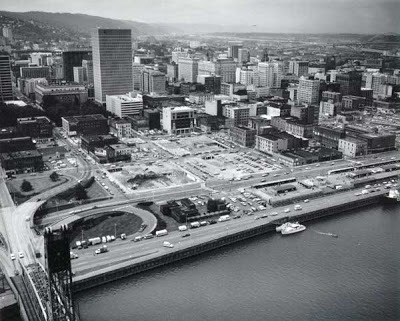

The west side of the city, with Harbor Drive. Look at all of that open space between the Standard Insurance Building on 5th and the riverfront! Photo Here.

In 1973, councilman Goldschmidt became Mayor Goldschmidt, and created the Office of Neighborhood Associations. This plan helped formalize a pathway for democratic engagement in city politics. However, the neighborhood associations could be an institution that’s beginning to show its age. In 2019, Commissioner Chloe Eudaly picked a fight with the neighborhood associations in Portland. Quoting from this article in the WW, she argues “Eudaly says neighborhood associations too often represent white homeowners and exclude renters, people of color and immigrants. And, she says, they serve as gatekeepers who stand in the way of denser development and the construction of more affordable housing.”

Eudaly proposed an ordinance that would help bring new voices and interest groups to official budget, land use, and development discussions; discussions currently limited to the formally-recognized and geographically-based neighborhood groups. The WW notes “currently, six identity-based groups—including the Urban League, the Latino Network, and the Immigrant & Refugee Community Organization—receive funding,” but are not currently invited to participate in those discussions. Eudaly’s ordinance hoped to change that.

2019’s Eudaly v. Neighborhood Association title fight portrayed the neighborhood associations as the white, home-owning, baby-boomer villains: a political vanguard keeping people with younger, fresher ideas out of the traditional channels of political access. These, of course, being the same villains who once organized to stop the expansion of two freeways, created a key downtown greenspace, forced the city to adopt a progressive view of transit planning, and helped establish systems for democratic engagement in city government.

The Portland west side waterfront today. Photo.

In his interview with the Belchers, DuRoche asked “if we were in danger of becoming complacent or resting too much on the laurels of past successes —and forgetting how to organize and coalesce around neighborhood, regional issues—I was greeted with a rousing, “Yes.”

“I would frame it this way,” Bob Belcher elaborates. “With this event of 40 years ago, this was kind of like our neighborhood—downtown. We lived in Irvington, but in a way, we worked downtown, we played down there, we just wanted it better. …These days we’re grappling with a regional project [the Columbia River Crossing] that has a misunderstood impact on this city and surrounding, adjacent neighborhoods and all kinds of ramifications that we can’t begin to understand. It’s ended up to be not just a simple neighborhood issue that a lot of us in the past could identify with and get rallied to, with an Allison Belcher haranguing us to get out and go to the picnic. It’s far more complex … how do we make the point these days?”

The Columbia River Crossing is no longer the Freeway Fight du jour: attention has now shifted to the I-5 freeway expansion through the Rose Quarter. It’s worth taking another look at Bob’s words above: are freeway projects today really more difficult to understand, ‘far more complex,’ and not just ‘simple neighborhood issues?’

In my last article, I wrote about the Seattle Labor Temple; at one point, a bustling center for labor activism; today, nearly empty. Less than a mile away, three glass domes built by Amazon serve as a new kind of temple to the American Worker. It’s clear from these features of the built environment that the nature of labor has changed. Perhaps labor activism needs to change as well. Considering Bob Belcher’s perspective, how have the fights against freeways changed? How does transportation activism need to change? How do the traditional methods of civic engagement need to change?

However, I think the other thing to consider is the effectiveness of Allison Belcher’s simple protest- a picnic in an unlikely place- and the spirit of activism it inspired in the Portland community. At the end of the day, said Belcher and fellow organizer Jim Howell, it was really about giving their kids a chance to get to the river. If we let the freeway take over the riverbank on both sides, they couldn’t have that chance. “It wasn’t political,” said Howell. “It was Civic.”

-----

I tend to get deep into research holes while writing these. This is part bibliography and part recommendations.

Carl Abbott’s book “Portland in Three Centuries.”

Carl Abbott’s book “Politics, Planning, and Growth in a Twentieth-Century City”

https://www.pdx.edu/usp/planpdxorg-riverfront-people

https://metroscape.imspdx.org/a-riverfront-park-runs-through-it?print=print

https://www.wweek.com/news/city/2019/09/11/chloe-eudalys-neighborhood-war-the-populist-commissioner-hits-back-against-critics-who-say-shes-strangling-portland-democracy/

https://www.portlandoregon.gov/archives/article/24741

http://rebelmetropolis.org/the-portland-riverfront-that-almost-was/

https://portlandtribune.com/but/239-news/463929-376278-learning-from-portlands-harbor-drive

https://www.cnu.org/what-we-do/build-great-places/harbor-drive

https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2019/04/12/chance-repeat-history

0 notes