#rupprecht crown prince of bavaria

Text

jacobite pretenders/heir-generals of the jacobites

#historyedit#weloveperioddrama#history#perioddramaedit#james ii#james ii and vii#james francis edward stuart#bonnie prince charlie#henry benedict stuart#maria theresa of savoy#charles emmanuel iv#victor emmanuel i#maria theresa of austria este#rupprecht crown prince of bavaria#my gifs#my gifsets

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rupprecht Maria Luitpold Ferdinand, Crown Prince of Bavaria

German vintage postcard

#maria luitpold ferdinand#bavaria#sepia#photography#vintage#luitpold#postkaart#crown#german#prince#ansichtskarte#ephemera#carte postale#postcard#rupprecht#ferdinand#postal#briefkaart#crown prince#photo#tarjeta#maria#historic#postkarte

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maria Theresa of Austria-Este , Queen of Bavaria with 11 of her children: From left: Crown Prince Rupprecht, Princess Adelgunde, Princess Marie, Prince Karl, Prince Franz, Princess Mathilde, Prince Wolfgang, Princess Hildegard, Princess Wiltrud, Princess Helmtrud and Queen Maria Theresa with Princess Dietlinde in her lap

Dietlinde died at age one and one more princess, Gundelinde, was born after her death. Another daughter, Notburga, was born between Hildegard and Wiltrud, but only lived for five days.

#Maria Theresa of Austria-Este#house of wittelsbach#crown prince Rupprecht#Adelgunde of Bavaria#marie of Bavaria#mathilde of Bavaria#hildegarde of Bavaria#wiltrud of Bavaria#helmtrud of Bavaria#dietlinde of Bavaria#prince karl#prince franz#prince wolfgang#long live the queue

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

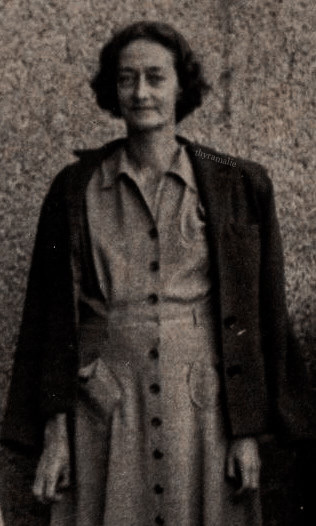

Grand Duchess Charlotte photographed with her freed sister Antonia, Crown Princess of Bavaria, and a nurse in 1945.

“Both Grand Duchess Charlotte and her younger sister, Princess Antonia, spent the wartime years resisting the Nazi regime. The two sisters did not have similar experiences, with Antonia's story being far more tragic than that of her older sister. The cadet sister of Luxembourg’s matriarch was profoundly affected by her wartime experience, which saw Antonia and her daughters imprisoned in several concentration camps. The family [of Antonia and her husband Rupprecht] became associated with a resistance plot in 1939 and the Gestapo seized Wittelsbach properites, including their main residence, Schloss Leutstetten. Rupprecht fled to Italy in exile and Antonia and the children followed not long after. Thus, in parallel with her sister, Antonia was no longer welcome at her home and living in exile, resisting the Nazis. After an assassination attempt was made on Adolf Hitler's life in 1944, Rupprecht and his son Heinrich went underground in Italy, separating from the rest of the family. Rupprecht and the family were quickly designated as opponents to the Nazi regime, and hunted down. The Nazis employed the use of Sippenhaft, the notion of kin liability and that a whole family is liable for the actions of one of the family members, to go after the Wittenbachs. Rupprecht may have been in hiding, but Adolf Hitler personally ordered the arrest of Antonia and her children. The Gestapo managed to capture Rupprecht's son from his first marriage in addition to Antonia and her three youngest daughters in northern Italy on 27 July 1944. Although accounts vary, it is generally believed that Antonia contracted typhus and was left at a hospital in Innsbruck, whilst her daughters were transported to the Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg concentration camp north of Berlin. Princess Irmingard, the eldest daughter of the couple, was captured separately near Lake Garda and brought to the same hospital as her mother. The two were eventually deemed 'well enough' to be transported to Sachsenhausen, although they were separated near Weimar. Generally, the historical consensus is that the family was moved first to Flossenbürg, then Dachau, as the Soviets advanced through eastern Germany. However, one source maintains that Antonia was held at Buchenwald concentration camp and cruelly tortured there. The obituary for Princess Irmingard also reports that her mother was found at a hospital in Jena in April 1945, which is 30 kilometres from Buchenwald. It has been difficult to ascertain the truth of this, but the internment in concentration camps had its toll on Crown Princess Antonia. When found in the hospital, she weighed less than 40 kilograms. The war had its toll on Antonia even in the after-war years. Prince Félix [Charlotte's husband], her brother-in-law, escorted her back to Luxembourg where she was reunited with her sister to recover, and her children joined in May 1945.”

Text source: (x)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

#polls#let's pretend the omission of max ii was on purpose and not that i completely forgot about him

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hohenschwangau Castle, Germany.

The present day Hohenschwangau ("Upper Schwangau") castle was first mentioned in 1397, though under the name of Schwanstein. Only in the 19th century the names of the two castles have switched.

Between 1440 and 1521 the Lords had to sell their fief with Imperial immediacy to the Wittelsbach dukes of Bavaria, but continued to occupy the castle as Burgraves. The Wittelsbachs used the castle for bear hunting or as a retreat for agnatic princes. King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria sold the castle in 1820. Only in 1832 his grandson Maximilian II of Bavaria, then crown prince, bought it back. In February 1833, the reconstruction of the castle began, continuing until 1837, with additions up to 1855. Hohenschwangau was the official summer and hunting residence of Maximilian, his wife Marie of Prussia, and their two sons Ludwig (the later King Ludwig II of Bavaria) and Otto (the later King Otto I of Bavaria). King Maximilian died in 1864 and his son Ludwig succeeded to the throne, moving into his father's room in the castle. After Ludwig's death in 1886, Queen Marie was the castle's only resident until she in turn died in 1889. Her brother-in-law, Prince Regent Luitpold of Bavaria, lived on the 3rd floor of the main building. Luitpold died in 1912 and the palace was opened as a museum during the following year.

From 1933 to 1939, Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria and his family used the castle as their summer residence, and it continues to be a favourite residence of his successors, currently his grandson Franz, Duke of Bavaria. In May 1941, Prince Adalbert of Bavaria was purged from the military under Hitler's Prinzenerlass and withdrew to the family castle Hohenschwangau, where he lived for the rest of the war. Today more than 300,000 visitors from all over the world visit the palace each year.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

OTMAA contemporaries: Leopold of Belgium and Luitpold of Bavaria with family.

The family of Duke Karl Theodor in Bavaria including what should have been two future kings. Both little princes were born in 1901, the same year as Anastasia Nikolaevna. Leopold, the fair-haired child standing on his grandmother’s lap, was the eldest son of King Albert of the Belgians (standing in the back) and Elisabeth, Duchess in Bavaria. Luitpold, the child on the ground being cuddled by his mother, was the eldest son of Elisabeth’s sister, Marie Gabrielle, and Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria.

Leopold would indeed grow up to be King Leopold III, but Luitpold died in 1914 of polio.

#otmaa contemporaries#leopold iii of the belgians#luitpold of bavaria#elisabeth in bavaria#albert i of the belgians#duke karl theodor in bavaria#marie gabrielle in bavaria#my collection

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herrenchiemsee New Palace

Herrenchiemsee New Palace is located in Chiemsee, Germany. King Ludwig II of Bavaria had the royal palace built in 1878, but the palace was incomplete when he passed in 1886. A few weeks after his death, the castle was open to the public. The palace is modeled on Versailles and built as a “Temple of Fam” for King Louis XIV of France, whom Ludwig II admired. Unlike the original Versailles, Herrenchiemsee Palace has toilets, heat, and indoor plumbing. Only twenty of the building’s seventy rooms are finished. This includes the Great Hall of Mirrors, the State Bedroom, the State Staircase, a Ballroom with Roman Emperor statues, and the king’s French rococo-style apartment. In 1876, a large garden was created, including famous fountains, statues, and formal and informal gardens. In 1907, the unfinished North Wing was demolished, and the South Wing was never built. In 1923, Crown Prince Rupprecht ceded the palace to the State of Bavaria. Since 1987, the palace has served as a museum with twelve rooms on the ground floor in the south wing. The property is a complex of royal buildings, including an Augustinian monastery from 1645 in the Old Palace. The monastery was converted into living quarters for King Ludwig II as he inspected the progress of the New Palace. #Castles #Palaces

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ludwig III of Bavaria with his family, 1885

#Ludwig III of Bavaria#Maria Theresia of Austria-Este#Rupprecht Crown Prince of Bavaria#Princess Adelgunde of Bavaria#Maria Ludwiga Princess of Bavaria#Princess Mathilde of Bavaria#Prince Wolfgang of Bavaria#Prince Franz of Bavaria#Prince Karl of Bavaria#Princess Hildegard of Bavaria#Princess Wiltrud of Bavaria#1880s#wittelsbach#bavarian royal family

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria-Este and her first born child, Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, 1869.

#archduchess maria theresa of austria-este#crown prince rupprecht of bavaria#bavarian royal family#queen maria theresa of bavaria#german royalty#german royal#bavarian

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Princess Maria Theresa of Bavaria, née Archduchess of Austria-Este, with her husband, Ludwig, later King of Bavaria, and their ten children: Rupprecht, Karl, Hildegard, Adelgunde, Marie, Helmtrud, Mathilde, Wiltrude, Franz and Wolfgang in 1885.

#Princess Maria Theresa of Bavaria#Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria-Este#Queen Maria Theresa of Bavaria#king ludwig iii of bavaria#Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria#Princess Mathilde of Bavaria#Princess Mathilde of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha#Princess of Bavaria#Archduchess of Austria#Wittelsbach#Hapsburg#Royalty#histolines

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

World War I (Part 61): Passchendaele

Many were doubtful about Haig's planned offensive in Flanders – for good reason. But, like Nivelle, Haig wouldn't listen to sense.

The infantry & tanks were to drive back the Germans at least 4.8km on the first day, and 24km overall within fifteen days. Once they'd captured that railway junction at Roulers, a specially-trained division would be landed behind the German lines, on the coast.

The Fourth British Army was positioned where the River Yser meets the sea (at Nieuwpoort). After the division was landed behind German lines, they would move eastward (under the protection of the Royal Navy's shipboard guns), and link up with it. The Germans, Haig declared, would be at the end of their strength, and after the Entente had forced them to withdraw from the coast, they wouldn't have enough troops to form a new defensive line.

Roselare = Roulers.

But the Germans knew what was coming, for starters. Haig knew it would be impossible to conceal anything except the amphibious landing – security was so strict that those training for it on the Thames Estuary (on the northern side of the Channel) weren't even allowed to write home.

The Germans had observation points on the low ridges circling Ypres, and from these (and aerial reconnaissance) they could see the biggest concentration of soldiers & weapons that the British army had ever put together.

So 14 German divisions were sent to Ypres (four from the Eastern Front) while the British were getting ready. A week after the explosion at Messines Ridge (probably June 14th), Ludendorff sent Fritz von Lossberg to Ypres. He had originated the new defensive system in depth, and he would be Chief of Staff of the German Fourth Army.

Lossberg had 50 days to prepare, and the German commanders became increasingly confident. The Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria was head of the army group in Flanders, and he wrote in his diary, “My mind is quite at rest about this attack, as we have never possessed such strong reserves, so well-trained for their part, as on [this] front.”

On July 10th, the Germans carried out a pre-emptive raid on the Yser bridgehead, which was where the British Fourth Army was supposed to move eastward from. The Germans drove them back to the other side of the river. They also found a tunnel that the British had been planning to use for blowing up important German positions at the start of their advance. So now the Germans knew that something big was being planned for the coast; and they had captured the (relatively) high ground just east of the Yser. The British were now in a more difficult position than they'd planned.

The preparations on both sides were huge. A seemingly-endless supply of gravel was being purchased in the Netherlands, and sent to Belgium by train, for the construction of the Germans' concrete pillboxes (the first line of defence) and underground bunkers (behind the lines, to shelter the counterattack troops).

Haig's plan was the same old thing that had been happening since after the Battle of the Marne. This was Lloyd George's opinion, and also Churchill's (the Conservatives had insisted that he wasn't to join any of the government's important war committees, but he was still very opinionated). Pétain and Foch thought the same (Foch called the plan “futile, fantastic and dangerous”). But Haig believed the sheer scale of it would make him succeed; also that the French were useless and that was why Nivelle had failed.

The weather was still unusually dry, but it wasn't likely to stay that way, and Haig didn't want to waste time in beginning the offensive. But there were hold-ups, and pieces of the plan weren't falling into place, and one non-rainy day after the other was wasted. Haig had given responsibility for the main part of the offensive to his youngest army commander, 47-year-old Hubert Gough. Gough was bold and eager for action, and was also originally a cavalryman – things that would have made Haig like him. But he wasn't good at organizing, and the staff he'd created was more arrogant than capable. Here at Ypres, the ability to organize huge numbers of men and quantities of equipment was extremely important.

On July 7th, Gough reported that his preparations weren't up to schedule, and that he was worried about the readiness of the French troops on his left – he needed more time. Haig said no. On the 13th, Gough asked again for more time (specifically, for five days). Haig agreed to postpone the offensive three days – from July 25th to 28th.

On July 15th or 16th, the British bombardment began – the most massive of the war so far, even greater than the Somme. The front was 24km long, and there were over 3,000 guns for it (over double the concentration at the Somme). The bombardment continued day and night for a fortnight (finishing on the 31st), with high explosives, shrapnel and gas being used. Preparations for the Somme had used only a million rounds; here it was four million rounds (100,000 of them gas). 65,000 tonnes of shells were used, killing 30,000 Germans before the offensive even began.

The landscape was already wrecked; now it was even worse. Before the war, the region had had a complicated drainage system because the terrain was so wet; now what was left of it was destroyed. When the rain came, there would be no place for the water to go.

On July 17th, with the bombardment having just begun, it was clear that another postponement of three days was necessary.

Lloyd George and his War Policy Committee were in a difficult situation – the offensive was a bad idea, but forbidding it could cause major political trouble. On July 20th, they finally informed Haig that he could proceed (they really had no choice, as they'd left it so long). The told him that if his attack wasn't quickly successful, he would have to stop, and asked him to specify his objectives. Haig told them he was offended, and they quickly sent another message assuring him that he had the committee's “wholehearted supported”.

On July 22nd, the barrage intensified. On the 26th, 700 British & French planes took off and cleared the air of German aircraft.

The final stage of the bombardment was on July 28th – a counterbattery barrage to deal with German artillery, which had been causing major damage to British positions. But this final stage had to be cut short because the fog came back, wrecking visibility for both sides. However, the weather continued to hold – there had been intermittent showers over the last fortnight, but nothing too bad. The artillery had turned the terrain into a mess of shell-holes, but it was still dry.

Third Battle of Ypres

The offensive began on July 31st, at 3:50am. 17 Entente divisions advanced, and another 17 were waiting in the rear.

At the northern end of the Entente line were two French divisions – they were to protect Gough's flank (on his left). Five divisions of Herbert Plumer's Second Army were at the southern end – they were to capture a few strongpoints, but mostly their orders were to hold the Messines Ridge as a pivot point for Gough's advance.

The main attacking force was 10 divisions of Gough's Fifth Army – they were to force the Germans back, and then the reserves would come forward. Gough had nearly 2,300 guns on about 11km of front (about 1 per 6m). The Entente had nearly 500,000 men in total.

Opposite them were the German machine-gun nests, arranged in a sort of chess-board pattern. Behind them, the German Fourth Army had 20 divisions arranged in four groups – 9 closest to the front, 6 behind them, 2 further back, and 3 even further back. German reserves were in place to move forward & fill in almost any hole the Entente made.

The French troops on Gough's left flank got to their objectives with relatively little difficulty. In the centre, Gough's forward units fought their way through the German first zone (which was the Germans' intention) and into the second zone. They advanced nearly 3.2km at some places, but only 800m in others. Within a few hours, 6,000 Germans were taken POW.

But things changed in the early afternoon. By now, a light rain was falling, and the leading British units had lost contact with their artillery. The Germans had field guns on higher points north & south of the British salient, and they opened fire. (If the fog hadn't cut the British opening bombardment short, these guns might have been destroyed.) The British, taking great losses, were forced back.

Gough had started with 52 tanks, but 22 had broken down; another 19 were put out of action by the German guns. By late afternoon, the offensive had slowed to a standstill, and it was raining hard. Haig reported to London that it had been “highly satisfactory and the losses light for so great a battle”. Actually, 23,000 had been killed or wounded, but he didn't realize this.

Also on July 31st, Pope Benedict XV sent a letter to the Entente & Central Powers governments, in which he offered to mediate a peace without territorial conquests. But Germany still would not settle the Belgium question. The new Foreign Minister Richard von Kühlman ignored the letter and decided to approach London directly, hoping to separate Britain from its allies by offering a private promise to withdraw from Belgium in exchange for a stop to the fighting.

But the new Chancellor Georg Michaelis destroyed the possibility of this idea succeeding. Ludendorff insisted that Germany had to keep effective control of most of Belgium, and also of the coal & iron mines of France's Longwy-Briey district. He also wanted large parts of East Africa.

There were various other attempts at arranging talks around this time (Austria & France were involved at some points) but nothing came of them. Both sides were determined that they were the ones to dictate the final settlement, with no compromise. Michaelis was completely useless in all of this, and the Reichstag came to hate him like they had Bethmann Hollweg. He had to resign after only three months in the job.

The Entente resumed the offensive on August 2nd, with torrential rain falling. The place was flooded – every shell-hole was filled with water, and the ground was so boggy that it was too deep to find a solid footing. The tanks couldn't move, and the planes couldn't fly. Haig still kept going.

But after two days, it was obvious that it wasn't possible. It was still raining, and the Entente casualties were up to 68,000. He ordered a halt until the ground dried out.

This wasn't until August 10th. A new attack was intended to drive away or capture the German artillery. They succeeded, but at high cost. As soon as they'd finished, Haig began planning for a resumption on the 14th.

But this wasn't possible either, causing two postponements of 24hrs. When they finally carried out the attack, it was (again) costly and achieved little. Haig should have stopped (according to the promises he'd made to London), but instead he decided to try something new.

This was the end of the first part of the Third Battle of Ypres. It had taken 3.5 weeks to cover about 4km – just over ½ of the first day's objective. Roulers hadn't been captured, and as it became clear that that wasn't going to happen, the amphibious force would be quietly disbanded. The British had 14 divisions that were too badly battered to continue and had to be replaced; the Germans had 23. Back in London, Lloyd George was complaining again.

The focus shifted from Gough to Herbert Plumer's Second Army. Plumer had been at Ypres for the past 2yrs, and like Pétain, he cared about them and was unwilling to waste their lives. His soldiers were loyal to him; their morale was high and they were eager for action.

Unlike Haig and Gough, Plumer had actually paid attention to and considered the new German defensive system. With this knowledge in mind, he worked out a counterattack, possibly inspired by his experience at Messines Ridge. Haig approved it and gave him 3wks to get ready.

Meanwhile, Lloyd George summoned Haig back to London for another meeting with him War Policy Committee. As usual, Haig argued that it was necessary to keep attacking Germans until they broke, which he was sure they were about to do; and as usual, Robertson supported him. He returned to France having won that round, and with Lloyd George still unhappy.

Plumer had figured out how to take advantage of the new defensive system. He realized that small territorial gains (about 1.6km or less) were easy because the Germans' forward positions were elastic & spread so thinly. But much larger territorial gains were definitely not possible, because the Germans were now much more able to counterattack in force. So they should capture only the easy ground, and not go far enough to set off a German counterattack – the exact opposite of what the Germans were luring them in to do. If they could carry out a series of such attacks, then they could drive the Germans out of their defensive infrastructure, and into a war of manouevre that they didn't have enough troops for.

During the first 3wks of September it didn't rain, and Plumer organized a huge mass of artillery (bigger even than the one of the initial bombardment). He ended up with one artillery piece for ever 5m of front. The bombardment would consist of five waves of fire, with each covering a destruction zone 200m deep – 1) shrapnel, 2) high explosives, 3) indirect machine-gun fire (aimed into the air because the gunners couldn't see their targets, and the bullets would arc down onto the defenders from above), 4) high explosives, and 5) high explosives again. The entire thing was about 800m deep, and the pattern would sweep over the Germans, so that each position would find itself in a new zone every few minutes. In the first day of this attack, the artillery would fire 3.5 million rounds of ammunition.

Plumer's troops had possession of slightly elevated ground that they'd first captured at Messines Ridge, and then later got more of by moving forward on Gough's flank. Because of this, they were able to conceal their preparations from the Germans.

Battle of the Menin Road Ridge

They attacked on September 20th, with the a creeping barrage in front of the advancing troops. The Germans who hadn't been killed by the initial bombardment were dealt with almost easily. When the troops had reached their objectives, they stopped and began to quickly construct defences. The main German troops were waiting in the rear until the British advanced towards them. By the time they realized it wasn't happening, it was too late to mount an efficient counterattack.

The operation had been quick and successful. There were 20,000 British casualties in total, but most of them were from German artillery fire after the advance. Both sides realized that things had changed. The Germans were worried, and the British were delighted.

Not only had they captured new ground, but the now had possession of some of the infrastructure of the Hindenburg Line – pillboxes and underground bunkers that the Germans needed for their defensive system, and they were now more vulnerable to attack. Plumer knew this, and hurried his artillery forward.

Battle of Polygon Wood

The Battle of Polygon Wood began on September 26th. The weather was clear, allowing Entente planes to fly low over the German defences, strafing and bombing them. After the initial bombardment, the troops advanced the assigned 800m on a 6.5km-wide front, and then dug in again, with the main German force looking on helplessly. They'd lost yet another set of strongpoints, and if things kept going as they were, they could end up losing all their infrastructure.

So they gave up on the new defensive system, and went back to the old way of doing things – deploying large numbers of troops in a strong forward line to fight off the attackers right from the start, and stop them from making easy gains. Plumer was moving his artillery forward again, preparing for another attack.

Battle of Brookseinde

This month was extremely dry – the dryest September on record at that time. But it wasn't to last. On October 3rd, the first day of the Battle of Brookseinde, a light drizzle began to fall.

The Germans had had only a few days to prepare their new forward line, and the bombardment slaughtered them. The German generals had been too eager, and placed the reserves too far forward, so they were blasted as well. The British advanced 700m and then stopped. They had suffered 25,000 casualties, while killing/wounding 30,000 Germans. Even though the casualty levels were about the same, this was unsustainable for the Germans. The old tactics weren't going to work for them. Something had to be done.

Ludendorff was receiving dispatches from Flanders, and was alarmed. He tried to think up a new offensive that could draw Entente troops away from Ypres, but it wasn't possible as they didn't have enough troops themselves. Pétain was launching attacks at Verdun & elsewhere, using French divisions that had recovered enough to be able to fight again. Ludendorff ordered the Sixth Army to use the new defensive system again, which at least would keep most of the troops out of reach of enemy artillery. But there really wasn't anything they could do.

The weather was what saved them. The drizzle turned into a steady rain, and a few days later a downpour. Flanders was turning into a huge shallow lake, with every piece of low ground filled to the brim. When the British commanders met on October 7th, Plumer and Gough said that they should stop fighting, but Haig refused.

Plumer's troops were along a line that would be extremely difficult to hold during the coming winter. They should have pulled back to some slightly higher ground, but Haig definitely didn't want to do that. He insisted on keeping going to capture Passchendaele Ridge. This was the northern extension of the high ground that Messines Ridge was a part of. The main force in this offensive was to be made up of Commonwealth divisions (NZ, Australia and Canada), as nearly every British division in the region was in a terrible state.

Passchendaele

“Passchendaele” means “Valley of the Passion”. The first attack in the valley was the Battle of Poelcappelle, and it began on October 9th. It was raining, and the conditions were absymal. Nearly everything was covered in water, and everything else was covered in deep mud. It was impossible to move the artillery or set it firmly in place where it already was. It was nearly impossible for the infantry to move, as the mud prevented them from finding footholds. Big guns sank into the mud out of sight, and so did an entire light railway. The only way they could bring the shells forward was to use pack mules – but many of the mules sank and drowned.

When they fired the shells, they sank into the mud without exploding – the surface was too soft to activate their fuses, as was the mud beneath the water. The Australians & NZers at the centre managed to fight their way forward, but they were then exposed to machine-gun fire from three sides instead of one. Eventually, they realized it was futile, and struggled back to where they'd started from. The wounded sank into the mud, as they couldn't make it back.

The Canadians were chosen to lead the next assault. They were commanded by Sir Arthur Currie, and he wasn't happy about it, predicting that it would cost him 16,000 men, but he didn't refuse. The Second Battle of Passchendaele began on October 26th. They took heavy casualties, and the Germans about the same. But they didn't make it even close to Passchendaele Ridge and what had once been the village of Passchendaele.

Four days later they tried again, with the same results. There was also a shortage of drinking water, because bringing water in was also extremely difficult, and the swamp around them had been poisoned by human waste and dead bodies.

Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo

The Italian Commander-in-Chief Luigi Cadorna had ordered two more Battles of the Isonzo back in May and August, and the Italians had suffered over 280,000 casualties. The Austrians opposite them had taken terrible levels of casualties as well, and when the battles were over, both sides begged their stronger allies for help.

Cadorna was a monstrous commander, suggesting seriously in units that didn't do well enough by his standards, 1/10 of the men should be shot. He worried that Russia's collapse would mean that Austria-Hungary would be able to send all its armies against Italy. But when he asked Britain & France for reinforcements, they would do no more than continue to send artillery.

The new Austrian Emperor Karl was warned by his general staff that the Austrians weren't likely to survive another Italian assault. (Franz Conrad had been demoted and was no longer Chief of the General Staff). The Emperor asked Ludendorff for help, but was rebuffed. So he contacted the Kaiser directly, who intervened.

A German general was sent to the Italian front and reported back that the Austrians were at the end of their strength. Reluctantly, Ludendorff created a new German Fourteenth Army, using infantry, artillery & planes taken from the Baltic, Romania, and Alsace-Lorraine. Otto von Below was to command it, and he was ordered to stabilized the Italian front with the shortest, most limited campaign possible.

The Battle of Caporetto (also known as the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo) began on October 24th. The Germans & Austrians attacked together, and were incredibly successful. They had only 33 divisions facing 41 Italian divisions, but over 16km on the first day. Cadorna tried to organize a retreat, but it turned into flight, and 100,000's of Italian troops surrendered.

Below ordered his troops to stop at the River Tagliamento, but they reached that so quickly that they kept on going. The Italian government fell and Cadorna was fired. The Italians stopped at the banks of the River Piave (about 32km beyond the River Tagliamento) and made a stand.

The had advanced about 129km in 70 days, shortening the southern front by 320km. The Italians had suffered 320,000 casualties, including 265,000 taken POW. Their stand on the River Piave claimed another 140,000 men. However, they were helped by the Germans' exhaustion and the onset of the winter rains.

This had been one of the war's most successful campaigns, and it seemed as if the war on the southern front would be ended. But the upheavals it caused led to the government & army under better leadership. Previously, the Italian troops had been terribly mistreated, and now this ended, leading to a boost in morale that would be to the detriment of the Central Powers.

Back at Passchendaele

On November 6th, under still horrendous conditions, fresh Canadian troops finally drove the Germans off enough of the Passchendaele Ridge for Haig to claim victory. Nearly 16,000 men had been lost, as Currie had predicted.

On the 10th, the Canadians attacked again, consolidating their new positions, and bringing the Third Battle of Ypres to an end. They'd taken three months and a week to gain 7.25 km – Haig declared it was an excellent starting point for the fighting in 1918, but other generals believed it was worthless.

The British, French, Anzacs and Canadians had taken 250,000 casualties, and the Germans nearly as many. The Germans had used 118 divisions, and many of them were used up. The British had larger divisions than the Germans at this point, and they'd used 43 and the French 6. Both sides were exhausted. The British army was nearly as broken as the French army had been after the Chemin des Dames.

Battle of Cambrai

This was the first time a military offensive used tanks on a large scale. On November 20th, Haig sent 19 British divisions (led by General Julian Byng) and the largest group of tanks yet assembled to attack the Germans. It was near Cambrai, east of the old Arras battlefield, and they attacked a thinly-defended section of the Hindenburg Line.

It was a great success to start with, but didn't last long. 216 new Mark IV tanks were used in the initial assault, but 71 broke down mechanically; 65 were destroyed by enemy fire; and 43 got bogged down. Some of them managed to break through the forward defences, terrifying the Germans and forcing them to flee.

This wasn't actually meant to be a battle of any significance. Haig intended it to be a demonstration to boost morale at the end of the year. There was no follow-through planned or attempted. The British had succeeded only on a narrow front, ending up with the enemy on three sides. On November 30th, 20 German divisions counterattacked and forced them back nearly to where they'd started from.

The Germans learned at Cambrai how to deal with the tanks. A lieutenant wrote about it, saying that “When the first tanks passed the first line, we thought we would be compelled to retreat towards Berlin.” But they figured out that they could stop them by throwing a hand grenade through the manhole on the top. This was a blind spot for the tank's machine-guns – they couldn't reach every point around the tank.

Once a German got on top of the tank, those inside were doomed – the British couldn't escape. The fuel began to burn, and within a couple of hours the Germans saw only burning tanks before & behind them. “Then the approaching troops behind the tanks still had to overcome the machine-guns of our infantry. These were still effective because the British artillery had to stop shooting as the tanks were advancing, and naturally some of our machine-gun nests were still in full action.”

The British attack came to a standstill, and they waited for the cavalry to sweep us and “drive us towards Berlin,” but it didn't happen. They pulled new troops together near the British breakthrough, the situation settled down, and they could see clearly where the tanks haad driven into their lines. After a few days they launched a counterattack, and on the third day they were successful.

The offensive had (as usual) been pointless, but not for knowledge – both sides' generals saw that the new tanks could have produced very different results, if they'd been used properly.

1917 was over. On the Western Front, 226,000 British had been killed; 136,000 French; and 121,000 Germans. The French were unable to mount a major offensive at the end of the coming winter (i.e. in early 1918) because of all the fighting. But the Germans had lost confidence in their new defensive system. These last two facts would shape the year ahead, and finally begin the end of the war.

#book: a world undone#history#military history#ww1#third battle of ypres#battle of the menin road ridge#battle of polygon wood#battle of brookseinde#battle of poelcappelle#second battle of passchendaele#twelfth battle of the isonzo#battle of cambrai#douglas haig#erich ludendorff#fritz von lossberg#crown prince rupprecht of bavaria#david lloyd george#hubert gough#herbert plumer#pope benedict xv#richard von kühlman#georg michaelis#arthur currie#luigi cadorna#otto von below#hindenburg line

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crown Prince Rupprecht Maria Luitpold Ferdinand of Bavaria

German vintage postcard

#historic#photography#vintage#maria#crown#sepia#rupprecht#photo#briefkaart#prince#maria luitpold ferdinand#ansichtskarte#postcard#bavaria#postkarte#postkaart#carte postale#ferdinand#german#ephemera#postal#luitpold#tarjeta

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria by Frank Eugene, Metropolitan Museum of Art: Photography

Rogers Fund, 1972 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Medium: Platinum print

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/260125

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Albrecht and Luitpold, the sons of crown prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, Photo by Frank Eugene, 1908

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Princess Clémentine of Belgium (30 July 1872 – 8 March 1955), was by birth a Princess of Belgium and member of the House of Wettin in the branch of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. In 1910, she became Princess Napoleon and de jure Empress consort of the French as the wife of Prince Napoleon Victor Bonaparte, Bonapartist pretender to the Imperial throne of France (as Napoleon V).

Third daughter of King Leopold II of Belgium and Queen Marie Henriette, her birth is the result of a final reconciliation of her parents after the death, in 1869, of their son and only dynastic heir, Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant. As a teenager, Clémentine fell in love with her first cousin Prince Baudouin. The young man, who did not share the feelings his cousin had for him, died of pneumonia in 1891 at the age of 21.

Clémentine hardly gets along with her mother, being closer to her father whom she frequently accompanies; the latter envisages, in 1896, that she marry Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, but the princess refuses this union. The years go by, Clémentine remains single. Around 1902, shortly after Queen Marie Henriette's death, she began to have feelings for Prince Napoléon Victor Bonaparte. Despite the support of the Italian royal family, King Leopold II (in order not to incur the wrath of the Third French Republic) refused any marriage plan between his daughter and the Bonapartist pretender.

Clémentine had to wait for her father's death in 1909 to finally being able to marry Prince Napoleon. Their marriage took place in 1910, after the new Belgian ruler, her cousin King Albert I, gave his consent. The couple moved to Avenue Louise in Brussels. The couple have two children: Marie Clotilde, born in 1912, and Louis Jérôme, born in 1914.

When World War I broke out, Clémentine and her family took refuge in Great Britain, hosted in the residence of the former Empress Eugénie. Across the Channel, Clémentine is active in favor of the Belgian cause because many compatriots have found refuge in England. With her cousin-in-law Elisabeth of Bavaria, Queen of Belgium, she works actively for the Red Cross.

After the Armistice of 11 November 1918, Clémentine returned to Belgium. In her Château de Ronchinne, in the Namur Province, she and her husband devote themselves to charitable activities, many after four years of war. Clémentine frequently visited Turin and Rome with the Italian royal family.

While she was somewhat removed from French political life, Clémentine convinced her husband to return to politics and supported him financially, but the latter gradually rallied to the republican idea. In 1926, Prince Victor Napoleon died a week after being subjected to a stroke. Clémentine brought up her two barely adolescent children and was keen to preserve the Bonapartist movement, of which she became the “regent” until her son came of age in 1935, but had no influence on French political reality.

From 1937, Clémentine stayed more and more frequently in France, but it was in Ronchinne that she was surprised by the declaration of World War II in September 1939. As soon as she can, she goes to France and stays there; the invasion of Belgium in the spring of 1940 prevented her from returning to her native country. After 1945, Clémentine somewhat abandoned her property in Ronchinne and divided her time between Savoy and the Côte d'Azur, where she died in 1955, at the age of 82.

#Clémentine of Belgium#House Saxe-Coburg und Gotha#XIX century#XX century#people#portrait#photo#photography#Black and White

6 notes

·

View notes