#saying 'ecce homo' is his thing

Note

he tried hurting me is all.

Oh no… Sorry Aeron. The wording was so ambiguous. The betrayal of Ephah (towards Aeron) vs the betrayal of Ephah (by Aeron).

When puzzling I leaned too hard on the context clues of the yandere/yangire deal seen in Limerence and came to the wrong conclusion that Aeron had been the aggressor.

It has definitely been a thing in many cultures to try and consume another’s powers, from outright cannibalism to people taking relics from the bodies of saints.

this is basically what happened. it's randomized, it's rare, but that's it. that is why the faces all turn blank but the eyes look the same of those around whoever enters "the spiral", as dubbed by aeron and genesis in the demo.

Woo! Wild speculation got one thing right!

anything that has eyes represented

Uh oh. Suddenly glad of not having any posters on the wall.

Damn. When doing that computer lesson meme I should have made Aeron stare directly out of the screen (like those paintings where the eyes follow you). Genesis kind of is looking at the viewer though.

i repair paintings that are affected in the spirals because i feel it is my duty. no one is going to do it as well as i will!

I take it Aeron has seen Ecce Homo, or the oil paintings given ‘90s style eyebrows.

aeron otherwise "preserves" dead lovers by taking pieces from them and keeping them in a collection.

Lock of hair, fairly traditional mourning custom… Body parts, serial killer territory… Completely confused and a little concerned about the tiny mermaid in that jar.

yes. erebus was a case. a very, very mild case touched by the manifestation.

Ah. So Eri was affected but not deliberately by Aeron. The street fight part is now confusing as the hallucinations started after the knock to the head affected his eyes. Unless those were separate things? Or he was attacked by someone affected and shoved back, or was in the very early stage before the hallucinations but had just begun spiralling.

aeron very explicitly states that he is willing to relinquish control from erebus. he already has.

[Eri screaming off screen about being bathed] /j

their relationship is built on misunderstandings on both sides. there is a happy ending for them.

*chants softly* Aerebus. Aerebus.

ripped everything out of their body, leaving them hollow

Did Lucia die completely? Or did they get sewn up with a Y incision and begin a new unlife as Scarlett? It contradicts all logic but I want them to have. And then they kill Silas, stopping his rampage.

i wouldn't say you exactly die with it every time. sometimes you just become something different. you know what i think the only solution is?

Sweet, a new and improved form. You will all regret this >:)

i am an aggressor. i always have been. but that doesn't mean i always am...well, i usually am, but i wasn't in this case. for once. though, perhaps, what i did to him led to this.

for clarification, the street fight, which caused erebus head and eye trauma, are the same event. this was a brush while walking home, where a spiraling aggressor attacked him.

don't worry, i'm unfortunately aware of ecce homo.

aeron thinks the people he loved are important. they are, of course. they know no one else will remember the people he loved. so, in addition to writing obituaries for every person that fall into their hands, they have a personal, private exhibit, just for their gaze.

the player will find those items. depending on how many they collect over their playthrough, they'll be able to access the main room of them.

lucia was killed completely. there was only a few eyes in her skin. her organs were taken. probably eaten by silas. a horrible way to go.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Everyone lives for themselves

How lonely and alone are people actually, throughout their lives and in the sometimes fast, sometimes slow stream of decades? What is just a facade, what is imagination, and how much do you need others to feel safe? Answering these questions often seems uncomfortable. Because they convey facts as light that no one wants to recognize. Filmmakers, among others, also ask themselves these questions and discuss in very different ways what being alone can feel like. Man comes into the world alone, interacts with others during his life, relies on his mother and father when things go well, later on the human being, if one can be found, and then, alone, leaves this world again. Encounters and belonging to others create the drive you need to keep going. If this component is missing, there is at least the hope that it could one day become that way. In Uberto Pasolini's Mr. May or the Whisper of Eternity, the loneliness of man in the midst of people is staged as a deeply sad, almost defeatist requiem that tightens your throat. David Lowery stirs up the pain of remembering and getting lost in the memories of a past life, both the living and the dead, with his metaphysical meditation A Ghost Story. In these films, people are asked to endure their existence - and also death - in the awareness that they will always remain alone with the fact of their existence because they cannot share their own existence. Because it is what you have.

This existentialism in the film allows Andrew Haigh to dream a big city dream in which the boundaries between reality and imagination dissolve right from the start. At the center of the psychogram, surrounded by a social vacuum, is a man named Adam, who lives in an apartment building floating above the London skyline that is almost empty. Adam is therefore a lonely cosmonaut who looks down on the million-dollar hustle and bustle of a big city without belonging. He is alone and lonely, listless, lost in thought, drained of the energy of the sunrise, which, it happens, puts on its show for him alone. Neighbor Harry (Paul Mescal), who rings his doorbell one evening, is also isolated and disconnected from a life of togetherness. At first Adam prefers no contact, but a short time later, after it becomes clear that both are queer and feel affection for each other, a tentative relationship develops that is always interrupted by a miraculous fact that reconjugates time and space. Because Adam, who lost both parents in a car accident when he was twelve, gets the opportunity to see his mother and father again. All he has to do is go to his childhood home and everything is suddenly the same again, as if Adam were twelve again. But he isn't, and his parents also know this, as they are aware that he has long since died.

What you wouldn't give to be able to say again to loved ones who have left us what you always wanted to say, to be able to ask again what you always wanted to ask. And just didn't have the opportunity anymore. This opportunity is revealed to Adam and he takes advantage of it. He says goodbye again, can hug his parents again, sort things out and tell them how things have been going for him since then. Andrew Scott gives the lonely person who cannot overcome the pain of loss and is afraid of suffering new ones, with a vulnerable intensity that makes you feel like you have known him for a long time. What he feels becomes palpable, because they are emotions that we are all familiar with. All of Us Strangers becomes an immersive soul journey to a primal fear bathed in colored light, protected by the cloak of repression. Haigh tears this one down. Ecce homo, you think you hear him say. And there he is, this Adam, a lonely human being, torn between longing, farewell and overcome by a desire to travel into his inner self.

Perhaps, some might criticize, All of Us Strangers indulges in an exaggerated sadness. I think emotions like these are too real to be called kitsch. Filming may not have been easy, but Scott seems to have remembered some of the painful experiences in his life. Haigh's film is hard to beat in terms of intimacy and closeness, is surreal, full of dream sequences and memories, immersed in color spectrums and accompanied by a hypnotizing score that leaves room for classics like The Power of Love by Frankie goes to Hollywood and this one finally from the Christmas Playlist deleted. All of Us Strangers is a close-up experience and a psychological trip, perhaps even a ghost story, but certainly not light fare and leaves a heavy, I don't want to say sentimental, but wistful feeling; a lump in the throat, a pressure on the chest. Haigh's film is not liberating, but it is exhilarating and beautiful in its epic exploration of existence, which consists of loss and search. The film has no hope, but a lot of insight. Above all, longing can also mean security.'

#All of Us Strangers#Andrew Haigh#Andrew Scott#The Power of Love#Frankie Goes to Hollywood#Paul Mescal

0 notes

Text

Yesterday I attended the evening lecture with Turner Award winning artist, Mark Wallinger. Admittedly, I went into his talk slightly too tired to receive the knowledge he imparted about his work. I found him to be engaging in the reasoning behind his work, but not quite an engaging speaker. I found it difficult to keep up with some of the points he made about his work.

Of the pieces he spoke about, I was very taken by the ideas he detailed about "Ecce Homo".

Given the religious ideals behind my current project, I was fascinated by his reasoning for creating this sculpture. Wallinger said his sculpture of Christ was not meant to be perverse or tongue in cheek. 'I wanted to show him as an ordinary human being, Jesus was at the very least a political leader of an oppressed people[...]' I was taken by humanising the image of Christ, I have come across this concept before, in a painting by John Millais: "Christ in the House of his Parents".

I was aware that upon it's public exhibition, Millais was met with public outcry of heresy that how dare he place the messiah amongst the meanness of the carpenters shop along with such iconography of poverty.

One thing I was disappointed in learning about "Ecce Homo" however, was that it was not carved, but cast to look like a marble statue. This raised notions of what could be construed as "cheating" to me. That said, it also raises questions of why choose to cast something over carve, does its cheapen the idea? Or is Wallinger trying to suggest an idea behind using casting and moulds? Either way, I am intrigued by material use, for its meaning, from my own work in using Oak, considered to be a holy tree in pagan faith.

After the talk I walked down to the Poly to visit the 2nd year Fine Art & Drawing exhibition. This being my first experience of a Preview night for degrees, I was overwhelmed by how busy and bustling it was. I couldn't quite appreciate what was on display. I was intrigued by the work the collective groups had created, but couldn't stop to penetrate their meaning.

I came away feeling overwhelmed and wondered if my own preview night would be equally as overwhelming. That said, I spoke to Duncan about what his take away from the exhibition was and he put my mind at ease saying that the purpose of the preview night is for socialising and conversation rather than taking meditative time to appreciate the art itself. There is a constant learning curve to being a creative. I am slowly piecing together all that this life I am embarking on entails. Sometimes I need to feel overwhelmed to learn the lesson involved. Either way, I was happy to see all the other students enjoying the fruits of their labours, even if I couldn't quite meditate on what they had made.

#falmouthify#drawing#falmouth poly#mark wallinger#creative life#celebration#exhibition#overwhelmed#raw

1 note

·

View note

Text

(Image ID: screenshot of two replies by @alicedraws-kostyalevin. saying: Funnily enough eponine works for thenardier but doesn't actually sacrifice herself for him (or at least, not anymore) but gavroche almost dies for him, and he doesn't even recognize who it was. Absolutely brutal. Les mis has a thing? for people recognizing others and there must be some symbolism here that I never thought about.)

(Context: this post about he parallels between Eponine and Javert)

I never thought about it until just now either and you’ve made me realize--- Javert’s weird power in Les Mis is just, his ability to recognize people?

Javert has a borderline magical ability to know who everyone Really Is, to know everyone’s True Names, regardless of their disguises.

There’s a common fandom joke that Javert is bad at recognizing people, but in canon it’s the exact opposite. Javert’s whole Thing is that he sees through disguises and recognizes the people that no one else is able to recognize, the people that everyone else forgets and overlooks.

And instead of using that power for good he uses it for evil. Javert could use his borderline magical skills to help all these forgotten people, but instead he uses it to condemn them and make them all suffer.

Javert even arrogantly shows off this semi-magical skill during the Gorbeau House ambush. All the members of the gang are masked; Javert orders them to keep their masks on, and then lists off their names one by one, to prove that he knows who they are even when they’re disguised.

“Why?” for the drama of it all

The six pinioned ruffians were standing, and still preserved their spectral mien; all three besmeared with black, all three masked.

“Keep on your masks,” said Javert.

And passing them in review with a glance of a Frederick II. at a Potsdam parade, he said to the three “chimney-builders”:—

“Good day, Bigrenaille! good day, Brujon! good day, Deuxmilliards!”

Then turning to the three masked men, he said to the man with the meat-axe:—

“Good day, Gueulemer!”

And to the man with the cudgel:—

“Good day, Babet!”

And to the ventriloquist:—

“Your health, Claquesous.”

God Javert is such a diva

And as mentioned on the other post: no one recognizes Eponine. Cosette sees adult Eponine and doesn’t recognize her/thinks she’s just a random boy, Marius doesn’t recognize Eponine even after she takes a bullet for him, Thenardier doesn’t recognize Eponine when he sees her in the Rue Plumet garden, etc.

But when Javert is about to be executed, he’s like “oh, it’s her. I know her.”

“Javert gazed askance at the body and, profoundly calm, said in a low tone:

“It strikes me that I know that girl.”

And when Valjean drags a muddied half-dead body away from the barricades-- Javert recognizes it as Marius:

He bent over, drew from his pocket a handkerchief which he moistened in the water and with which he then wiped Marius’ blood-stained brow.

“This man was at the barricade,” said he in a low voice and as though speaking to himself. “He is the one they called Marius.”

(ok I literally never noticed the parallel between the way he recognizes Eponine and Marius’s bodies.............quietly saying ‘oh I know this person’ to himself in a low voice, while Valjean looks on)

But the biggest example is obviously Valjean. Javert recognizes Valjean when no one else does, when everyone else thinks he’s crazy for recognizing him, when everyone else thinks a mayor couldn’t possibly be a felon, etc. He’s the only one who recognizes Valjean when he’s wealthy and a mayor, not just when he’s a prisoner dressed in rags.

At the Champmathieu trial no one believes Valjean’s testimony. They think he’s gone mad, even his own prison-mates don’t seem to know him, they think he can’t possibly be Valjean because he’s too rich and educated, etc. Valjean gets Upset and says:

“I wish Javert were here; he would recognize me.”

Nothing can reproduce the sombre and kindly melancholy of tone which accompanied these words.

And I don’t know how feel about this aspect of Javert????? But it’s....a Thing!!!

#les mis#javert#Javert has One hobby#one thing he does for fun#and it's 'pointing out what people he recognizes'#(redeemed Javert would love people-watching I've decided)#also everyonewasabird wrote a post about the use of 'ecce homo' in les mis#and Javert is kinda like. he is the Pontius Pilate of Les Mis right?#saying 'ecce homo' is his thing#his whole thing is constantly running around saying 'THIS IS THE MAN'#and gesturing at Valjean#who is the jesus christ of les mis#anyway idk if that's cohrerent but its another post#I was gonna write a whole response to birds post about htat#but i have the attention span of a goldfish#speaking of which i need to do homework ahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh#bye

455 notes

·

View notes

Text

debunking RP talking points: women as men’s muses.

If you have ever listened to Jordan Peterson and other RP youtubers, you will have probably heard about the concept that men have built civilisations, invented gadgets and gone to war for women; meaning women inspired them in one way or another to pursue the achievement of these feats.

Now let’s start with the fact that men didn’t build civilization on their own, regardless of whether you think women contributed more or less is not the matter at hand; saying that 50% of the population built civilization all on their own is just an example of male hubris (arrogance). Same thing with inventions and discoveries, Isaac Newton said it best: “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”, meaning we rely on the discoveries and inventions of others to propel us further (that is why I don’t believe in self-help or the self-made man/woman, but that is for another day). When it comes to wars, sure most people on combat units were men, but there were plenty of women-only brigades and military groups (snippers like Lyudmila Mikhailovna Pavlichenko, The Night Witches) as well as nurses that took care of the soldiers in dangerous situations. Regardless, this is not the point.

Saying that the men who have been great were inspired to be that way by women is an ego stroke for women that will put them back in the kitchen. What do I mean by this? Well, this idea puts women in the position of the muse and not the inventor, conqueror or builder, it conveys that the way for women to be great is to be the inspiration for great men to do their feats, and not to do the feats themselves. Effectively it is the “behind every great man there is a great woman”. regurgitated and plated in a new way to not offend modern sensibilities. Don’t get me wrong, it is rather flattering to think that these great men like Einstein, Nietzsche or Aristotle were inspired by women, but how true is this?

You will make sure: that my clothes and laundry are kept in good order; that I will receive my three meals regularly in my room; that my bedroom and study are kept neat, and especially that my desk is left for my use only. You will renounce all personal relations with me insofar as they are not completely necessary for social reasons. Specifically, You will forego: my sitting at home with you; my going out or travelling with you. You will obey the following points in your relations with me: you will not expect any intimacy from me, nor will you reproach me in any way; you will stop talking to me if I request it; you will leave my bedroom or study immediately without protest if I request it. You will undertake not to belittle me in front of our children, either through words or behaviour. (Source: Einstein: His Life and Universe, by Walter Isaacson)

“Woman is unutterably more wicked than man, and cleverer; goodness in a woman is already a form of degeneration... Deep down inside all so-called ‘beautiful souls’* there is a physiological illness—I shan’t say any more, to avoid becoming medicynical. The struggle for equal rights is even a symptom of illness: every doctor knows that.—The more womanly a woman is, the more she fights tooth and nail to defend herself against any kind of rights: the natural state, the eternal war between the sexes puts her in first place by a wide margin, after all.” (Source: Friedrich Nietzsche - Ecce Homo)

“The female is a female by virtue of a certain lack of qualities, a natural defectiveness.”- Aristotle

How can such misogynistic men be inspired by the women around them if they can’t even see them as equals?

Here is the thing, men will argue that they build skyscrapers, create new technological devices and go to war for women so that women feel obligated to give back in the form of some sex and so that they are relegated to the positions of subservient muses.

As far as I am concerned, men don’t have a pussy clause in their contracts, where they are promised women in exchange for work, inventions or fighting in wars. This is male entitlement. If a man ever tries to make you feel obligated to be intimate with him because he did a,b,c and d for the community, kindly remind him that he was getting paid with money, not pussy.

#A fair amount of history's greatest men were VERY misogynistic#This is a hustle at the end of the day#Ladies#don't fall for it#also most of these men who bring this up have never done shit for their communities and are just appropriating the success of other men#call them out on their bs#Red pill

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

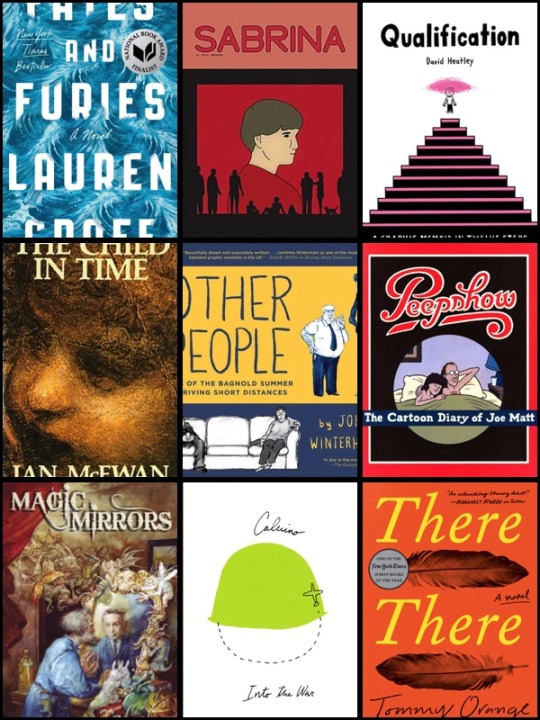

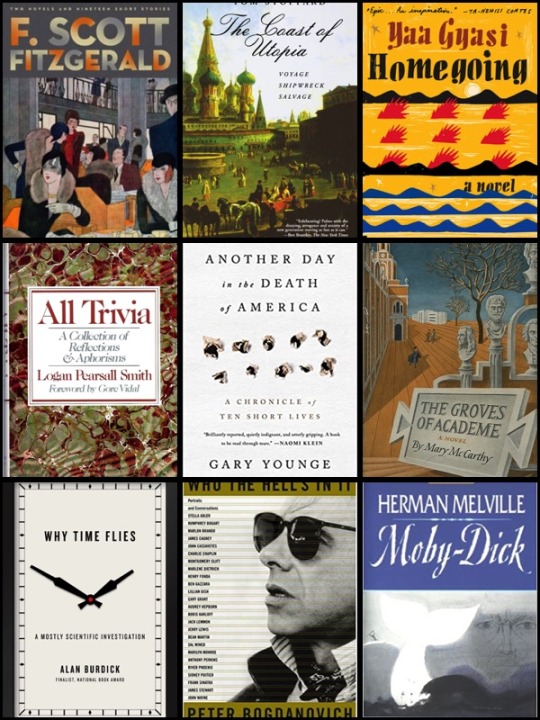

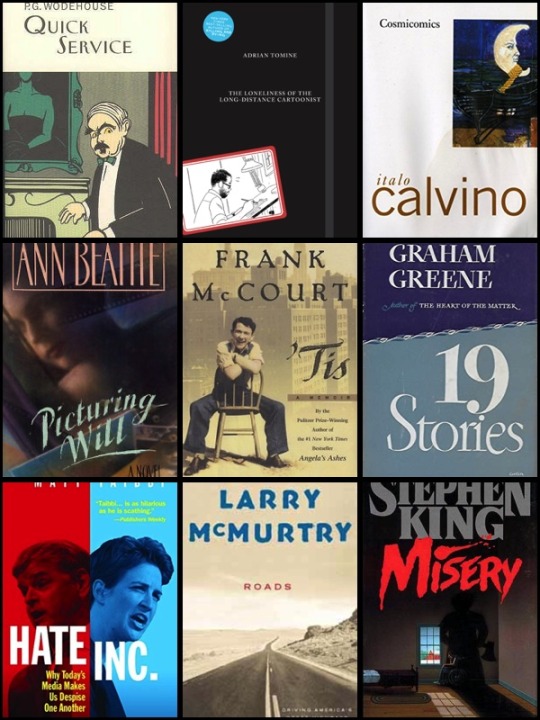

Books in 2020

Since this year is preserved in amber, I’ve done a much better job remembering the books I read as compared to 2019. Only six books have turned to dust in my mind.¹ On the other hand, I only read about two-thirds as many books as usual. It’s a minor example of the way the pandemic crabbed everyone’s life in 2020, but it can be added to the quilt.

Almost everything we did that year was dictated by the practicalities the pandemic forced on us. In a dull way, that “looking inward” we all had so much time to do strongly shaped this list, particularly the middle of it: when I needed something to read, I could only look inside my apartment.

Fates and Furies, Lauren Groff (Jan. 2-17)

Lots of acclaim for this book. All of it misplaced. The main problem is that the novel concerns (in part) one character’s brilliantly written plays. But on the basis of the material we see, the plays are pretty weak, so the credibility of the larger story is shot. I suppose the character’s work is as good as the writing in this novel itself, which I also thought little of. Tediously dour (it takes place in a world where, apparently, nobody has ever laughed or been laughed at) and full of sentences that sound clever, but don’t actually mean anything (to paraphrase a movie). Barack Obama said it was his most enjoyed book of 2015, which I have to hope was just the stress of the job getting to him.

Sabrina, Nick Drnaso (Jan. 2-5)

Timeliness is not something that I usually value, but Sabrina makes it seem like a worthy pursuit. It’s about crime and the ugliness of the internet and “fake news,” so it’s sure to grab any contemporary reader’s attention. But the craftsmanship of the art and the intelligence in the writing are so good that this would be an interesting book, even if we lived in Universe B, where those issues aren’t so omnipresent.

Qualification, David Heatley (Jan. 18-23)

I once read Heatley slagging off Monty Python and the Holy Grail on the grounds of it not being wholesome enough. So I shunned him for ten years, until this book popped up at the library. It’s about the numerous 12-step programs Heatley participated in and essentially became addicted to. That irony is sort of analyzed, but not deeply enough to feel that it’s really been addressed. Still, his honesty, the details of how the programs work, and the depictions of the people he meets there are good enough.

The Child in Time, Ian McEwan (Jan. 21-31)

The set-up is a nightmare, one of the scariest things I can imagine – a child is kidnapped and never found – but most of the book deals instead with the aftermath, years later, as the father tries to reintegrate into a world that’s moved on from his horror. The relationship between the main character and his estranged wife is good, and though some of the other threads (political, ghostly) didn’t stick with me so much, the well-captured emotions of the characters alone make this worth a read. I’m only now realizing, with surprise, that I haven’t picked up any of McEwan’s other books since this.

Other People, Joff Winterhart (Jan. 23-27)

Two stories, one about a son and a mother, the other about a son and a father figure. Both a little sad, both a little sweet. The older folks are a bit buffoonish, but turn out to be subtly good influences on the teenagers. I liked that the stories were about young people and drawn in a style that looked like something a high schooler (a talented high schooler!) would have drawn in his or her notebook.

Peepshow, Joe Matt (Jan. 8 - Feb. 1)

Not sure if I remember this one, or if I’m just remembering other Joe Matt comics I’ve seen throughout the years. But either way, I can confidently say that it’s full of frank presentations of Matt’s life and relationships, with no censorship of his most depraved thoughts and behaviors. It’s the sort of thing that could seem false and self-aggrandizing (“I fear not the audience’s gaze, ecce homo, etc, etc”), but in Matt’s case, it never comes off that way. He’s just telling the story as it comes naturally to him, and if you can tolerate his excesses, it’s enjoyable.

Magic Mirrors, John Bellairs (Feb. 1-11)

I have read and re-read all of John Bellairs’ young adult novels, but I had never before attempted his adult work, all of which is anthologized in this book. The Pedant and the Shuffly and St. Fidgita and Other Parodies are forgettable, but The Face in the Frost and its incomplete sequel, The Dolphin Cross, are great fun. They’re both about Prospero, a wizard who does very little magic, and mostly wanders around from one odd, irreverent chapter to another. I most enjoyed the town that disintegrates as Prospero tries to flee, and the dinner scene with the tank of sentient fish.

Into the War, Italo Calvino (Feb. 13-19)

No fantasy, no whimsy, no invention. This is a most un-Calvino-like collection of three short, probably autobiographical stories about being a teenager at the onset of World War II. It’s never terribly interesting, and you start to sense that Calvino felt obligated to write this, as though he wasn’t sure if he was allowed to put his talents to use on off-the-wall novels rather than sober stories of important (“important”) realism (“realism”). What does work, though, is his rendering of teenage life, which seems to be consistent across time and place.

There There, Tommy Orange (Feb. 19-27)

It’s very good. Chapters jump between the stories of a dozen Native Americans in the Oakland area, all of which eventually coalesce gracefully and unpredictably. There’s a lot of nicely rendered detail and effortless intelligence in the characters and the plotting, and there’s the charge that you get from realizing, as you read their stories, how infrequently these stories are told.

Once I Was Cool, Megan Stielstra (Feb. 28 - Mar. 5)

A collection of essays about being young, about being a thirtysomething, and about being a thirtysomething who’s reminiscing about being young. It’s all fine and Stielstra never once lapses into the sort of loathsome snobbery that you sometimes see in essay collections like this. But none of the material ever achieves escape velocity; it’s always mildly interesting and mildly amusing. There may be some loathsome snobbery at work in me, though: having lived so long in New York, I reflexively view Stielstra's Chicago-based anecdotes as inherently trifling.

L.A. Woman, Eve Babitz (Mar. 6-11)

I don’t think I was at all aware of Babitz’s celebrity when I picked up this book, but even I could tell that it was a memoir disguised as a novel. That works okay – the vision of Los Angeles that she presents (appalling and vicious, yet you wouldn’t want to be left out of it) is powerful in any format – but the book might have been stronger without the vague gestures towards a novelistic structure. Of course, my appraisal came from a distracted mind: this is the book I was reading when the world started to fall apart.

Thieves Fall Out, Cameron Kay (Mar. 13-24)

Written pseudonymously by Gore Vidal for some quick cash. He hoped it would be forgotten, and it was only after his death that it was republished. Vidal was perhaps overly dismissive of the book, but nothing of value would have been lost if the publisher had respected his wishes. The Egyptian setting is decently evoked, and the twists and turns of the pulpy plot are serviceable, but the whole thing is impersonal – surprising for a writer who usually had no trouble putting his voice to work.

The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil, Stephen Collins (Mar. 16-18)

A cute little fairy tale about a neat, orderly island that is disrupted by one man’s beard, which grows and grows until it overwhelms everyone’s existence. It could probably be read successfully as a cheeky story about conformity, but I hope there wasn’t anything that prosaic or moralistic behind it. I like it more as a loony story with no point. The art style reminds me of the end credits of the 2004 film adaptation of A Series of Unfortunate Events (which is a compliment, as the credits sequence was the best part of the movie). After I checked out this and the Vidal book, the Los Angeles libraries shut down, even to returns, so these two sat on my table for months.

4 3 2 1, Paul Auster (Mar. 25 - Apr. 18)

Stuck at home, I started reading books that I’d had on the shelf for years, books too heavy to have read during my commute. This one introduced me to the new experience of being disappointed by Paul Auster. It’s not as dazzling as his other books, which usually pack so much invention into a brisk story. Other than the premise (four divergent versions of the same man’s life told concurrently), this one is pretty conventional. And there’s a lot of seen-it-before reminiscences about the America the Boomers grew up in, and the upheavals of the 1960s. Boring material in anyone’s hands. Still, page by page, the writing was good enough. The nested story that his hero writes about the inner life of a pair of shoes was terrific.

Ulysses, James Joyce (Apr. 19 - May 1)

I did read every single word of this, but very little of it stuck with me. Aside from the lines that seemed to cater to me specifically – nostalgia-inducing descriptions of Dublin streets; a gorgonzola sandwich; and an early scene of Bloom talking to his cat (who says, “Mrkgnao!”) – I didn’t understand what I was reading. This is probably due to me not being smart enough, but how about this: Samuel Beckett said that James Joyce “had gone as far as one could in the direction of knowing more…I realized that my own way was impoverishment, in lack of knowledge and in taking away, subtracting rather than adding.” So maybe some of us are wired to receive Joyce, and some of us are wired to receive Beckett.

The Complete Eightball, Daniel Clowes (May 2 - June 7)

I had read most of these stories in reprints and anthologies, but this collection has them as they originally appeared in Clowes’ comic books. This is the best way to read them. A chronological arrangement means you can see the evolution of his talents. Plus, you get the original covers, as well as all the sundry material that filled up the pages between stories, like advertisements, editor’s notes, and letters from readers who accuse him of selling out by moving from Chicago to Oakland. I particularly liked when Clowes encouraged his readers to record their crank calls (“long denied [their] rightful place as one of the great, indigenous American artforms”) and send the tapes to him for evaluation and prizes. The contest is “quite legit, I assure you.”

The End, Karl Ove Knausgaard (May 2-20)

The last of his six-volume autobiography cycle, but the first one I read. The ordinary details of his life are reported nicely, without ornamentation, and the meta-material, as he deals with the fallout from having used his friends and family as grist in the earlier volumes, is candid and reflective. There’s a long and slightly baffling section in the middle where he discusses Hitler’s autobiography, but it makes you feel appreciative: Knausgaard read it so you will never have to.

United States, Gore Vidal (May 21 – June 19)

The best of Vidal. 40 years of essays in one 1,700-page book with miniscule type. There are, of course, lots of good zingers and well-aged material about drug laws, police brutality, and the corruption of the political process. But with such a quantity of work, you get to spot some of his usually deemphasized sweetness. There are warm remembrances of Tennessee Williams and Eleanor Roosevelt and the Wizard of Oz books.

Flappers and Philosophers and Tales of the Jazz Age, F. Scott Fitzgerald (June 20-30)

19 stories across two collections. Fitzgerald apparently referred to about half of them as “trash,” but I liked them. There’s a good balance of humor and happy endings with some unexpectedly gothic material. “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” a gruesome tale about greed and the terrors of rural America, is a standout, and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” would be too, if we weren’t already so familiar with the premise.

The Coast of Utopia, Tom Stoppard (July 11-17)

I had this trilogy of plays on my shelf for ten years, carried it between five homes, waiting for the right time to read them, hoping that I would have the opportunity to see them performed first. I should have kept waiting. The scripts are impenetrable, owing mostly to there being several dozen characters (with long Russian names) to keep track of.

Homegoing, Yaa Gyasi (July 20-25)

The first book in four months that I was able to check out of the library. I had to pick it up in a sanitized paper bag from a branch miles from my home. It was worth the trip. The novel follows two branches of a family down through several generations. One stays in Ghana, the other is taken to America. Each chapter follows a new descendant in the family line, and each time a chapter ended, I was sad to be leaving behind that character and that setting. But every subsequent chapter was just as good, so I was happily swept through to the end.

All Trivia, Logan Pearsall Smith (July 26-30)

It was well reviewed in the Gore Vidal collection. A couple hundred short aphorisms and observations on all manner of things, both physical and abstract. Pretty good, and I remember reading a few of the best ones aloud to people in earshot, but they’ve all disappeared now. There was something funny about sunspots…

Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives, Gary Younge (Aug. 3-8)

Younge picks a 24-hour period and tells the stories of 10 American children (aged nine to 19) who died by gun violence in that time. It’s a really expert example of journalism. Younge renders the victims, the killers, the survivors and the deaths themselves vividly without ever become maudlin or trashy. Nor is he heavy-handed. This isn’t a gun control advocacy tract (though it works very well as that); it’s just a description of ten deaths that would otherwise have not been known to the wider public, and an invitation to think about how you feel to be living in a society where this happens every day.

The Groves of Academe, Mary McCarthy (Aug. 8-13)

After my success with McCarthy in 2019, we slid right back into the mud on this one. It’s a satire about universities, with one professor out for revenge after his teaching assignment is rescinded. I usually flip for novels like this, or at least I used to, but this one never grabbed me. And yet, I still keep checking the “McC” shelf at the library…

Why Time Flies: A Mostly Scientific Investigation, Alan Burdick (Aug. 13-17)

Pop science about time and how we perceive it. Pretty good, and has some fun little facts to deploy in party conversations (“Want to know what happens when a person lives in a cave for two months without sunlight or clocks to tell time?”), but at length it wasn’t as interesting as the excerpts in the New Yorker review that made me want to check it out in the first place.

Who the Hell’s in It: Portraits and Conversations, Peter Bogdanovich (Aug. 17-27)

A good collection of profiles and critical appraisals of actors and directors. Bogdonavich doesn’t bring out the knives. He seems to like everyone, or at least have a fondness for everyone he talks to or about. He even likes Jerry Lewis, which is hard to understand, based on the person that Lewis reveals himself to be in their long interview: vain, angry, and constantly bestowing his “generosity” on those less talented than him. I’m not sure it could have been more damning if it had been writing by a person who hated Jerry Lewis.

Moby-Dick, Herman Melville (Sep. 4-16)

This one works. It lives up to the hype. Much livelier and more readable than you would believe. It’s diverse in its approach, taking the whale narratively, biologically, symbolically, historically…any way you want to look at a whale, it’s here. And each chapter is so short that even if you come upon a dull one, you can just gloss through it and quickly be on to something new. Captain Ahab deserves his reputation as an eternal character. My favorite scene is the one where the ship encounters another captain injured by Moby Dick, and Ahab becomes infuriated that this other man has managed to laugh about it and move on with his life.

Quick Service, P.G. Wodehouse (Sep. 27-30)

Everything Wodehouse writes is brilliant to some degree and forgettable to some degree – forgettable because all of his stories are so similar as to run together in your memory. (This is not a strike against him; the familiarity is what gives him space to run wild with set pieces and verbal invention.) This novel has a higher than average degree of forgettability, owing to less than average characters and scenarios. Still, reading anything by Wodehouse will only make you healthier.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, Adrian Tomine (Sep. 30 – Oct. 2)

Simple vignettes of incidents in Tomine’s life that shaped him as a cartoonist. By a freak chance, these are totally congruent with extremely humiliating moments in his life. The only complaint I have is that it was too short.

Cosmicomics, Italo Calvino (Oct. 1-5)

If Into the War was an un-Calvino-like book, this one is Calvino-ish to a fault (if it’s possible to find fault in him). These 12 stories are about outer space and ancient life: the last dinosaur, the first creatures to walk on land, a time when the moon was close enough to the earth that people could hop between them. I was about to say that this was maybe shaky ground on which to build, that Calvino is better when he begins in our familiar Earth and then gets fanciful…but even writing that list of topics made me smile. And then there’s the best story, where the narrator, searching the skies, sees a galaxy with a sign reading, “I saw you,” and realizes that he was spotted, one hundred million years before, doing something embarrassing! Forget what I started to say. This book is great.

Picturing Will, Ann Beattie (Oct. 7-12)

Will is a little kid, surrounded by struggling adults. There’s not much of a plot, just images from the life of a small family. Like everything Beattie writes, the story is fragile and slow and devastating, and she fills her characters with a lot of psychological depth. I have to dock it points, however, for the introduction and mishandling of a particular plot point that I won’t spoil. I’m not sure you can casually bring something so fraught on board without it capsizing the whole book.

’Tis, Frank McCourt (Oct. 14-21)

The sequel to Angela’s Ashes, following McCourt as he tries to make it as a young man in America. Even away from horrible Irish poverty, his life is still pretty bleak. McCourt takes a lot of abuse from all sorts of people, and even once he’s settled down with a teaching career and a family, the hits keep coming. And that’s not to mention the horrendous health problems (endless eye infections!) that plague him for the first few years. But, “stories only happen to those who are able to tell them,” and McCourt relays everything with a lot of humor and sincerity and poetry.

Nineteen Stories, Graham Greene (Oct. 22-31)

The short story isn’t his medium. All 19 of them are fine, but only two are memorable: The End of the Party” about a child’s game of hide-and-seek that ends tragically, and “The Basement Room,” about a young boy disappointing and being disappointed by his hero. Interesting that an author famous for writing about grown-up matters like politics, espionage and war should write so well and so evocatively about the experiences of children. (Wait, no, that isn’t interesting.)

Hate Inc., Matt Taibbi (Oct. 31 – Nov. 7)

In his introduction to this book about the deterioration of the media, Matt Taibbi offers himself as an example of how nastiness has been incentivized, recounting that he once won the National Magazine Award for an article referring to Mike Huckabee as a “nut job” who resembled an “oversized Muppet.” I don’t think he needs to apologize for that (and amusingly, later in this book, he reflexively lets fly some even more juvenile insults without realizing he’s fallen back on his old tricks), but it’s a fair starting point for his dissection. Nothing in this book is a surprise – yes, the political media, particularly cable news, profits from keeping its audience in a state of constant agitation – but the examples he marshals are good, and his style is clean and straightforward.

Roads, Larry McMurtry (Nov. 24-27)

McMurtry’s memoir of driving across the country. It’s unusually decentered for a journey immortalized in a book: he’s not driving for more than a few days per month, he’s not taking scenic routes (he sticks to the biggest interstates), he’s skipping big portions of the highways he does take, and he doesn’t spend too much time talking about his destinations. He calls the book Roads, and he means it. But he makes it work. His thoughts and observations, whether of the landscape surrounding him or merely inspired by it, are aimless, but smart and confident. Though my attitude towards cars is less fond than his (it’s been rudely called “ecoterroristic”), McMurtry evokes a convincingly romantic view of American driving.

Misery, Stephen King (Nov. 27 - Dec. 2)

Highly acclaimed and deservedly so. The claustrophobic set-up never gets old. The violence, though shocking and extreme, never become tasteless or silly, as in a few of King’s stories I could mention. And the villain, Annie Wilkes, steals the show. It’s quite scary to have the dawning realization that she’s sane enough to successfully pull off her hideous plan, but too crazy to be reasoned with, or even predictably strategized against. It’s perhaps an unrealistic balance, but in Misery, I believed it unreservedly.

***

There are two ways to look at it. It was a successful year: I only read one out-and-out stinker. At the same time, it’s a highly conservative list. Not to put down any of these authors individually, but I feel a little embarrassed by the cumulative effect of all of these familiar names. I can stick most of the blame on having been unable to wander the library and browse, but it could also be an incipient impatience. I’m getting older. Maybe I just don’t feel like taking my chances with some new author.

Or maybe this is just one of those bad habits that we get to leave behind in 2020, chalking it up to the pressures of facing that endlessly rising tide of shit, rather than any personal failings. That’s the fun (or the “fun”) of having survived a pandemic. You get to look back at your life and figure out, “Was that me? Or was it the virus?”

¹Heads or Tails, Lilli Carré; Old Souls, Brian McDonald & Les McClaine; Alex, Mark Kalesniko; The Hard Tomorrow, Eleanor Davis; Cannonball, Kelsey Wroten; and The Collected Stories of Mavis Gallant

#lauren groff#nick drnaso#david heatley#ian mcewan#joff winterheart#joe matt#john bellairs#italo calvino#tommy orange#megan stielstra#eve babitz#cameron kay#stephen collins#paul auster#james joyce#daniel clowes#karl ove knausgaard#gore vidal#f scott fitzgerald#tom stoppard#yaa gyasi#logan pearsall smith#gary younge#mary mccarthy#alan burdick#peter bogdanovich#herman melville#pg wodehouse#adrian tomine#ann beattie

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

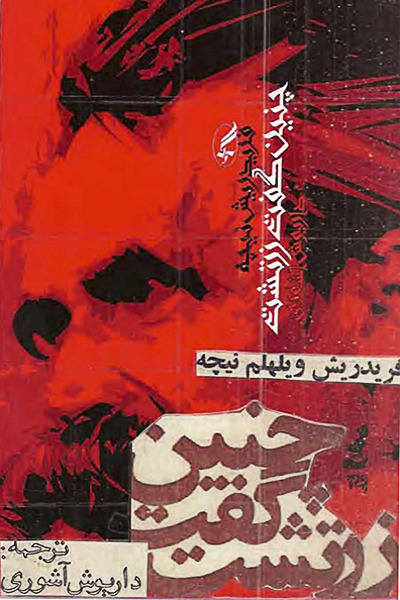

Nietzsche: amor fati!

It’s Nietzsche time!

Friedrich Nietzsche (pictured) didn’t have many love affairs in his life but he did have at least one: ‘amor fati’ (‘love of fate’).

‘My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity . . . I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who makes things beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love henceforth!’ (Ecce Homo and The Gay Science)

Jokes aside, there is some great philosophy in amor fati. Nietzsche looked to it as a means to achieve self-unity—a rare achievement amongst humans. How does one reach it?

‘Glance into the world just as though time were gone: and everything crooked will become straight to you.’ (Kritische Studienausgabe)

We must covet eternal recurrence to overcome ‘ressentiment’. This is a state in which one assigns blame for their weaknesses on external causes and feels envy and inferiority with respect to others. But one can free themselves from this torture by accepting fate’s unity: be willing to live the same life through eternity.

So embrace your drives, Nietzsche implores; sublimate and harness them in a concerted way. A weak will lacks order; a strong will is coordinative.

‘The multitude and disgregation of impulses and the lack of any systematic order among them results in a 'weak will'; their coordination under a single predominant impulse results in a 'strong' will: in the first case it is the oscillation and lack of gravity; in the latter, the precision and clarity of direct.’ (Kritische Studienausgabe)

Ressentiment stifles us; we become weak. Conversely, to love fate—to fully wish life back eternally—is to affirm one’s life: to overcome, with valour, the struggle ressentiment bring.

What if a demon were to creep after you one night, in your loneliest loneliness, and say, “This life which you live must be lived by you once again and innumerable times more; and every pain and joy and thought and sigh must come again to you, all in the same sequence. The eternal hourglass will again and again be turned and you with it, dust of the dust!” Would you throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse that demon? Or would you answer, “Never have I heard anything more divine”?’ (The Gay Science)

#philosophy#nietzsche#amor fati#fate#eternity#psychology#ressentiment#will#unity#existentialism#nihilism#philosophy memes#philosophyblr#philoblr

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 3.1.10 ‘Ecce Paris, Ecce homo’

One of those heavily allusive chapters I have no idea how to do justice to.

We start by saying the gamin is good but the fact that he is left uneducated is a tragedy and a shame that the world will have to reckon with--an idea that will eventually lead us to Friends of the ABC.

We move on from the gamin to Paris, the city the gamin personifies. “Ecce homo” is quoted directly in this chapter title, and Paris is bound up with it, and I wish I knew what that was doing, exactly. It sure seems important, given how tied Jean Valjean’s name is to “behold a man.”

It has something to do with the simultaneous holiness and everyman-ness of Paris and Jesus and Valjean, I think.

And Hugo spends some time arguing that Paris stands in for everywhere and has everything, in a chaotic mashup of the classical and modern. His exile is palpable here: Paris seems to feel as mythic to him as the cities of antiquity. He must have felt his chances of seeing the one again weren’t necessarily much better than his chances of seeing the others. Nostalgia feels like part of this, and I have a lot of sympathy for him there.

But of course, he also really means it. Which is weird and complicated--like, on the one hand..... sure?? I guess? Finding the universal in the specific is the purpose of storytelling. By defending Paris’s universality, he defends the universality of his characters and his message.

But on the other hand, finding the universal in the specific is the bread and butter of stories exactly because you can do it anywhere. Paris is a specific place with a specific culture, and both are fascinating! But I’m a lot less inclined towards this very nineteenth century notion that culture can have a pinnacle.

I don’t think the great cosmopolitan hodgepodge is any more the height of humanity than anywhere else is. And this belief in Paris’s superiority has terrible implications when it leads to imposing that “superior” culture on the rest of France and France’s colonies--a thing Hugo really tends not to see the negatives in.

The chapter ends with bitter sarcasm about the place de Grève, I believe the traditional site of executions:

Paris is synonymous with the cosmos. Paris is Athens, Rome, Sybaris, Jerusalem, Pantin. All civilizations are there in condensed form—and all the barbarisms with them. Paris would be really furious if it didn’t have a guillotine.

A bit of a place de Grève is a good thing. What would this whole endless feast be without such seasoning? Our laws have wisely provided for it, and thanks to them, the blade drips over the Mardi Gras.

He is absolutely against the death penalty; we know this. I suppose he’s saying that part of the universality of Paris is that she isn’t free of the dark sides of humanity either.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 3.1.8, “Concerning a Charming Remark Made by the Late King,” 3.1.9, “The Old Spirit of Gaul,” and 3.1.10, “Ecce Paris, Ecce Homo.”

These chapters are so dense and I feel like I should have more to say about them. They take us from still talking about the gamin, to the gamin as representative of the French and particularly the Parisian spirit, to a whole chapter of effusive praise of Paris and its spirit that’s where the digression, for the first time, starts to feel like it’s getting away from Hugo.

I don’t think it is--and 3.11 will pull things together at least somewhat, in tying Paris’s greatness inextricably to Paris’s revolutionary tendencies. But Hugo’s homesickness for the city he thought he might never see again is palpable here, and it makes his assertions that Paris is self-evidently the greatest city in all of human history come off as sincere and believable.

The piling up of all human history in one place in 3.10 echoes, very strongly, language we’ll get in the sewer digression--especially 5.2.2. “The Ancient History of the Sewer,” with its long passage namechecking other great cities and famous Parisians. Here, we’re getting the daylight city, Paris above ground; after the barricade, we’ll see the subterranean echoes of everything here. (And in between, that idea--that everything visible in the city has an unseen mirror beneath its surface--will be made explicit in Mines and Miners.)

I’m still feeling my way to what that imaginative geography is doing in this book--it’s not simplistic on any level; the sewers contain liquid gold and the scaffold of the Place de Grève is out in the light of day--but it’s layered into the Paris volumes right from Book 1.

Donougher’s notes on these sections are extremely thorough, but for once the classical parallels are mostly not that illuminating. The one that jumped out for me was the comparison of the gamin to the Roman graeculus: literally “little Greek,” it’s the word for a enslaved tutor: someone who teaches the arts of civilization to free citizens without having any of the rights of one.

(What do free citizens of Paris need to learn from the gamin? Spoiler, it’s revolution, but we’re going to take a whole chapter break from answering that question for plausible deniability.)

And of course, there’s the most direct Ecce Homo we’re going to get until the last chapter, and it’s...not about Jean Valjean. And I really don’t know what is going on there. Clearly, all men are contained in The Parisian just as all cities are contained in Paris--and this is in keeping with the avatar of Paris being a child, who might grow up into anything. And the final image of the guillotine blade dripping over Mardi Gras brings us back to the context of the biblical Ecce Homo (and also, oof, that’s sure a thing to keep in mind when we get to the wedding day).

But it’s really striking me how much Valjean is not Parisian, for all that he lives the last part of his life there. He’s never fully comfortable there, and always gravitates toward the less populous areas and the places where there’s some hint of nature. You can behold Paris, or you can behold Jean Valjean, but they don’t overlap. And in his one conversation with Paris’s avatar Gavroche, Valjean repays him with interest for the theft from Petit-Gervais and gives him permission he doesn’t need to break streetlights--and Gavroche intrudes on one of the worst nights of his life to deliver a profoundly unwelcome bit of news and summon him to another moral reckoning.

--”He is eager to acquire, by who knows what mysterious pooling of knowledge, every talent that might serve the common good. From 1815 to 1830 he imitated the turkey’s gobble. From 1830 to 1848 he scrawled pears on walls.” Were turkeys associated with the Bourbons?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hitman Oddities - Hitman and the Internet

Reference 1 - Hitman: Contracts

In the PC version of Hitman Contracts typing in the cheat “IOIPENNY” will give 47 a cardboard tube as a weapon. The weapon one hit kills everything it hits and acts like a knife when used from behind. The weapon itself is a reference to a 2003 web comic strip from Penny Arcade, where one of the two main characters finds a cardboard tube and hits his friend with it. This would later become a recurring joke of sorts, with this character becoming “the Cardboard Tube Samurai”. This wasn’t even the only game to reference this bit, Tekken got in on it too:

https://www.co-optimus.com/article/2563/tekken-6-trailer-stars-penny-arcade-s-cardboard-tube-samurai.html

Now Penny Arcade is still around sure, but it’s nowhere near as influential to gaming at large as it used to be. Web comics in general, especially the kind that are centred around topical gaming humour, haven’t been popular in years. Nowadays when I hear webcomic I think “strawman argues with the author” rather than “Mario does mushrooms and gets high” like was the norm for comics back then. The last time I heard about Penny Arcade was some controversy where people got mad they made a comic making fun of Kotaku that was a panel too long, which must’ve been about five years ago.

fozmeadows.wordpress.com/2012/06/02/penny-arcade-vs-rape-culture/amp/

Speaking of controversy, I found this strange Wordpress blog that talked about a Penny Arcade AND Hitman controversy. The more things change, huh?

Reference 2 - Hitman (2016)

This reference was featured in Oddheader’s video “Top 10 Video Game Discoveries & Mysteries 2018”, I’d recommend checking that out but I’ll give a quick summary.

In 2016’s Sapienza location on the Church walls is a very amateurishly-drawn painting of the Lord Jesus Christ. This is a reference to a very famous story of a real life failed restoration of a painting of Jesus called “Ecce Homo” that became a meme back in 2012 for how ridiculous it looked. It took about two years after 2016’s release and six years after the incident for someone to notice the Ecce Homage in the level, which is a testament to how much there’s always left to discover and Hitman and how old you have to be to remember what the painting was referencing.

Reference 3 - Hitman: Blood Money

Contracts referenced a webcomic and 2016 referenced a famous internet story, but Blood Money has both of these kinds of references hidden in dialogue and the end of level newspaper:

https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/lion-in-wait/

At the end of the House of Cards a side article can be seen on the news report of your latest work talking about “a Cambodian midget fighting league” being challenge to fight by a lion in the arena, and being killed in the process. Now unlike the painting this article is based off of a fake story that circulated around the internet in the early 2000’s, and was even famous enough to fool Ricky, Karl and Steve in this wonderful segment of The Ricky Gervais Show:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=d9VXNOODc_U

Now when I discovered this article in the game I thought someone who played the game sent the story in to the podcast as a troll, but this story was already famous by the time Blood Money came out so it was just a case of this story living on in two well-remembered properties.

Speaking of which, some dialogue in the White House level of the game has two guards talking to one another. One wants to show something on the computer to another, the other asks “is it midget porn again?” The original man says “No, Pokey the Penguin”.

http://www.yellow5.com/pokey/

Pokey the Penguin is an absurdist comic strip created in 1998 that’s drawn entirely in MS Paint. So not only does it predate all Hitman games, but it’s also as old as IO Interactive itself. It’s still updated to this day, but I may be showing my age when I say I’ve never heard of this comic outside of Hitman. It reminds me of 12oz Mouse with it being so crudely drawn and... weird.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry to bother you, but i was wondering if you knew of any name-puns that hidden in les mis? I know Enjolras seems similar to enjôleur, Marius and Marie, Combeferre and -maybe?- comburere or feros, Joly and joli, Montparnasse and Mount Parnassus (I don't know why, but Parnassianism came after the brick was published so it can't be that) but I'm not quite sure if i can find any others, or if I'm thinking too much? I love your blog btw! you feel like a wonderfully sweet person!

Aw, thank you very much! And thanks for the question, this is always a fun topic!:D 1.-Probably the best Name Pun in the book is “Jean Valjean”. Take a deep breather for this one: it depends on knowing that Jean and gens, French for “people” , sound a lot alike, and on knowing some Christianity references, and on Hugo’s full explanation for JVJ’s name– that it’s a contraction of “Jean, Voila Jean” – “Jean, look/behold, there’s Jean” .

So to translate, it sounds a bit like “People, look at the people” or “behold the people”. Which in turn is a reference to Ecce homo , the phrase supposedly said by Pontius Pilate when he presented Jesus to the crowd that had sentenced him to the crucifixion (and Hugo later gives Marius the phrase there is the man , or Behold the man -Voilà l'homme–directly,in acknowledging Valjean as his savior).

So Jean Valjean isn’t just “Johnny Everyman” (although it’s that too!). It’s Hugo saying “Here is The People”, and implying “here is the man” , too: Here is the people, condemned by the people. Here is the man, the savior of the people, chosen as sacrifice by the people.

It is what Hugo might class as a Very Serious Pun.

Moving on to something lighter!

Bossuet– the nickname for Legle,who’s from Meaux- - is a punning reference to Jacques-Bénigne Lignel Bossuet– the Bishop of Meaux, sometimes called “the eagle of words” – L’aigle des mots (sounds like Meaux). Double damage pun!XD

A feuille is a leaf–as in a tree leaf, or a sheet of paper. Feuilly is a fan maker, someone whose career is heavily about manipulating sheets of paper (and , probably, about painting a lot of decorative foliage).

Grantaire sounds like Grande Air, which is…exactly what it sounds like, Big Air, like putting on airs or being full of hot air XD . It may also be an Art Pun; salons at the time sometimes marked rejected canvases with a Capital R , a hint as to the level of Grantaire’s artistic success.

Two of my favorites!The “Jehan” of Jean Prouvaire’s name is exactly what Hugo says it is– a reference to the Romanticist movement’s fannish embrace of the Medieval era. But the Prouvaire in his name is another medieval reference– it comes from a Middle French word meaning Priest, tying Jehan into the spiritual role that Hugo saw as an essential part of a good Romantic Poet’s calling. And! it is probably also a reference to the Rue des Prouvaires– specifically the Rue des Prouvaires conspiracy, a legitimist conspiracy that also hoped to overthrow the new king in 1832. Why associate republican,revolutionary Jehan with a royalist, legitimist conspiracy? Probably because Gerard de Nerval– a blushing, awkward, badly dressed poet, young republican activist, and old friend of Hugo’s, and the guy Jehan seems to be a full on character homage towards –had been mistakenly arrested in association with that conspiracy (on account of some very bad timing). Which is to say: it’s a fandom buddy in-joke (and memorial).

Bahorel is another Romanticist-in-joke/homage name; pronounced with a silent H, the name,along with everything else about the character, is a pretty blatant reference to openly republican Frenetic Romantic Petrus Borel, another of Hugo’s friends from the Wild Young Romantic days.

As for Montparnasse, that had been the name for a section of Paris (on the left bank) for ages. Given the rather morbid description of the character, I suspect Hugo was trying to specifically evoke Montparnasse cemetery; he is, after all, the dandy of the sepulchre, with a lot of dead bodies to his name. I’m also still not sure it isn’t a bit of a friendly dig at Parnassianism; afaik the “official” name of the movement comes from the journal launched in 1866, but the people who were part of it had been in contact with each other as a group and talking over Art Movement Things for a good while longer, and Hugo had been in correspondence with a lot of them , too. So I can’t say for sure it is, but I really harbor a sneaking suspicion, especially given the insistence on Aesthetics Over All..!

–phoo, I’m not even scratching the surface here! But here is another post with more Name Puns; and there are probably many many more to be discovered! If you find one I don’t have listed anywhere, please let me know!:D

#name puns#Fandom 101#Les Mis#long post#Some Puns Are Serious#Name References#Religion Talk#Hey Nonny Nonny#answereds

448 notes

·

View notes

Note

Should we kill or love the monster?

I like this question !

You can try to love it but affairs with monsters are always short-lived. He will hate what you love and you will hate what he loves. And since ‘what you love is your fate’, neither of you will be happy. You won’t be able to attune the monster's barkings and your sweet songs even though you both speak about the same thing: tragedy.

Kill him? Why would you kill him? I know we consume so much stories where the death of the monster is mandatory but these are propaganda, you shouldn’t listen. They are afraid you would choose the dragon over the king. That’s why they show you the severed head of the dragon, so you know better than to betray them. The monster doesn’t want to take your place under the sun, but you want to take his place amidst darkness. So you want to kill him out of what? Jealousy? Our monster is our Christ, Ecce Homo. He will undergo so much pain to keep you safe. Please, don’t kiss him like Judas kissed Jesus. please, just cry and collapse like Mary, after all, he is also your child.

If I may offer one last possibility, why don’t you let the monster eat you? I say eat you and not kill you, to eat is not to kill, the little red riding hood was still alive in the belly of the beast. Let him take control. I know he is everything you’re afraid to be. But we’ve slain so much monsters out of fear than to jump inside his mouth, the void, is just fair retribution.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Deep Claim, the Final Shape, and the Will to Power: Nietzsche and the Hive

A Comparative Analysis of Key Ideas from Nietzsche and the Books of Sorrow

I am not a Warlock, but bear with me.

The key concepts in Hive philosophy, as articulated in the Books of Sorrow, are reflected or paralleled in the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche. Below, we shall examine the two central ideas in the Hive worldview, the Deep Claim and the notion of the Final Shape, consider pertinent excerpts from Nietzsche, and evaluate how these ideas inform how one should exist according to the Hive-Nietzschean perspective.

The Deep Claim is the foundation of Hive philosophy: “Existence is the struggle to exist” (Books of Sorrow 1:8, 2:3). Nietzsche never writes exactly so simple a characterization, but he expresses the same outlook:

we must beware of superficiality and get to the bottom of the matter, resisting all sentimental weakness: life itself is essentially appropriation, injury, overpowering of what is alien and weaker; suppression, hardness, imposition of one’s own forms (Beyond Good and Evil section 259).

Elsewhere, he puts it more poetically:

And life itself confided this secret to me: “Behold,” it said, “I am that which must always overcome itself. Indeed, you call it a will to procreate or a drive to an end, to something higher, farther, more manifold: but all this is one, and one secret.

“Rather would I perish than forswear this; and verily, where there is perishing and a falling of leaves, behold, there life sacrifices itself—for power. That I must be struggle and a becoming and an end and an opposition to ends—alas, whoever guesses what is my will should also guess on what crooked paths it must proceed.” (Thus Spoke Zarathustra, “On Self-Overcoming”)

For Nietzsche, as for the Hive, the essential quality of existence is the contest between each subject or form against all others. He would find the Deep Claim familiar and agreeable. Likewise, as the Hive (and the ambiguous Darkness or Deep which they serve) regard this contest as an amoral fact, Nietzsche too repudiates the very notion of any higher moral or ethical structure that might cast a shadow of condemnation on this harsh view of the universe. “Verily, men gave themselves all their good and evil”, he says. “Verily, they did not take it, they did not find it, nor did it come to them as a voice from heaven. Only man placed values in things to preserve himself—he alone created a meaning for things, a human meaning.” (Thus Spoke Zarathustra, “On the Thousand and One Goals”)

If the Deep Claim is Hive philosophy’s foundation, then the Final Shape is its pinnacle. As the Hive worm gods remind Oryx: “Existence is the struggle to exist. Only by playing that game to its final, unconditional victory can we complete the universe.” (Books of Sorrow 2:3) ‘Completing the universe’ means achieving the Final Shape: a form of existence impervious to destruction because it has destroyed everything other it has ever encountered. It is that which has struggled to exist against all else that existed, and prevailed.

Says the worm god:

Don’t you want to build something real, something that lasts forever?

Our universe gutters down towards cold entropy. Life is an engine that burns up energy and produces decay. Life builds selfish, stupid rules—morality is one of them, and the sanctity of life is another.

These rules are impediments to the great work. The work of building a perfect, undying creation, a civilization everlasting. Something that cannot end.

If a civilization cannot defend itself, it must be annihilated. If a King cannot hold his power, he must be betrayed. The worth of a thing can be determined only by one beautiful arbiter—that thing’s ability to exist, to go on existing, to remake existence to suit its survival. (Books of Sorrow 2:7)

Or, as Oryx reflects: “The only way to make something good is to make something that can’t be broken. And the only way to do that is to try to break everything.” (Books of Sorrow 4:4)

Like the Deep Claim, the Final Shape is not subject to external moral condition. The Deep itself says, in complaint to Oryx, “they call us evil. Evil! Evil means ‘socially maladaptive.’ We are adaptiveness itself.” Far from being evil, pursuit of the Final Shape is merely “the universe figuring out what it should be in the end.” (Books of Sorrow 4:2) It is not a question of achieving a good end, but rather a question of existence or nonexistence—and since existence at any cost is the only end to strive for according to the Deep Claim, it is therefore the only possible good.

From Nietzsche comes a parallel concept, perhaps of less cosmic scale, but no less all-pervasive importance in his view: the will to power. We find the best, clearest definition of this often misunderstood concept in Beyond Good and Evil (section 13): “A living thing seeks above all to discharge its strength—life itself is will to power; self-preservation is only one of the indirect and most frequent results.” In other words, will to power is not merely the desire to accumulate power or grow stronger. Rather, it is the urge for the action of power, the use of strength, in and of itself, for its own sake. Whereas the notion of the Final Shape points toward the ultimate outcome of the contest of every form of existence, the idea of the will to power describes the drive to participate in that contest as a naturally inborn feature of living things.

Accordingly, Nietzsche regards following the will to power as a good in itself. Oryx would heartily agree when Nietzsche asks and answers:

What is good? Everything that heightens the feeling of power in man, the will to power, power itself.

What is bad? Everything that is born of weakness.

What is happiness? The feeling that power is growing, that resistance is overcome.

Not contentedness but more power; not peace but war; not virtue but fitness...

The weak and the failures shall perish... And they shall be given every possible assistance.

What is more harmful than any vice? Active pity for all the failures and all the weak (Antichrist, section 2).

Here Nietzsche’s sentiment is eerily similar to the rejection of civilization proclaimed by the worm gods and the Deep. In the universal war between formless and form, the Deep’s pro-social adversary, the Sky, “builds gentle places, safe for life” (Books of Sorrow 1:8), which the worm gods characterize as “cosmic slavery.” Like Nietzsche, they regard supporting or protecting what would not survive on its own as perversely contrary to the nature of reality.

The Sky seeds civilizations predicated on a terrible lie—that right actions can prevent suffering. That pockets of artificial rules can defy the final, beautiful logic.

This is like trying to burn water. Antithetical to the nature of reality, where deprivation and competition are universal. In the Deep, we enslave nothing. Liberation is our passion. We exist to help the universe achieve its terminal, self-forging glory. (Books of Sorrow 2:1)

Oryx is even more articulate in his argument against sheltering civilization:

A species which believes that a good existence can be invented through games of civilization and through laws of conduct is doomed by that belief. They will die in terror. The lawless and the ruthless will drag them down to die. The universe will erase their monuments.

But the one that sets out to understand the one true law and to perform worship of that law will by that decision gain control over their future. They will gain hope of ascendance and by their ruthlessness they will assist the universe in arriving at its perfect shape.

Only by eradicating from ourselves all clemency for the weak can we emulate and become that which endures forever. This is inevitable. The universe offers only one choice and it is between ruthlessness and extinction.

We stand against the fatal lie that a world built on laws of conduct may ever resist the action of the truly free. This is the slavery of the [Sky], the crime of creation, in which labor is wasted on the construction of false shapes. (Books of Sorrow 5:5)

Nietzsche essentially agrees: “One has deprived reality of its value, its meaning, its truthfulness, to precisely the extent to which one has mendaciously invented an ideal world.” (Ecce Homo, section 2) Elsewhere, he elaborates:

I call an animal, a species, or an individual corrupt when it loses its instincts, when it chooses, when it prefers, what is disadvantageous for it... Life itself is to my mind the instinct for growth, for durability, for an accumulation of forces, for power: where the will to power is lacking there is decline. (Antichrist, section 6)

To both Nietzsche and the Hive, deviation from the struggle to exist, discharge of one’s strength to any end but continual overcoming, especially to prop up anything or anyone that otherwise would succumb—all this is not only wasteful, but reprehensible, since it runs counter to the natural will to power (in Nietzsche’s terms) and hinders the process of the universe toward the Final Shape (in Hive terms). Since they are videogame villains, the Hive enact their philosophy by pursuing literal cosmic annihilation. Of course, Oryx sees it otherwise: “The Deep doesn’t want everything to be the same: it wants life, strong life, life that lives free without the need for a habitat of games to insulate it from reality.” (Books of Sorrow 5:6) Nietzsche could almost have written the same words. He may not have harbored the Hive’s ambition for universal destruction, but he certainly seems to have shared much of the outlook behind it.

Toland, that most accomplished connoisseur of Hive arcana, once addressed us: “Dearest Guardian, I write to you from a place of high contempt. No no no, don’t be offended, don’t be so superficial—it’s in the architecture of these spaces. They look down on you.” (Grimoire, “Echo of Oryx”) This hearty contempt is the characteristic attitude of the Deep Claim, and those who would pursue attainment of the Final Shape. It invites all comers to contest conflicting claims to existence, and looks down upon those others as necessarily untrue, unworthy of existence unless they prove otherwise by destroying and overcoming—which itself only proves the Deep Claim’s truth. Tellingly, Nietzsche too exhorts his readers: “One must be above mankind in strength, in loftiness of soul—in contempt.” (Antichrist, preface)

Author’s note: My quotations of Nietzsche are taken from Walter Kaufmann’s translations. I am happy to provide bibliographical information and precise citations upon request. All emphasis in those quotations is as it appears in the source texts.

53 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am thinking about becoming one of those pretentious dicks who's really into Nietzsche where do I start

This feels slightly backhanded, Violet, lmao

I’ll preface by saying that 1) I think the best starting place will likely depend on what you are trying to get out of him and 2) I cannot claim to have read all of his work though I’m pretty familiar with the contours of his career.

[For a quick guide to the periodization of Nietzsche’s work, see here.]

That said, my personal favorite pieces are “On Truth and Lies in a Non-Moral Sense” and On the Genealogy of Morality, written at opposite points of his life. The former is a short epistemological essay, the latter is what I would call his key work of political and ethical philosophy. Both of these are pretty illustrative of how radically Nietzsche was breaking with a lot of philosophy that had come before him. Genealogy in particular was the first work I read by him and was what piqued my further interest, and “On Truth” is an good starting point because it’s an early work that is substantially more interesting than The Birth of Tragedy, his first book written around the same time.

After either of those, maybe move onto Beyond Good and Evil or one of the aphoristic middle-period books; since the middle period books are made of aphorisms and BG&E is somewhat similar to that, they’re much more free-flowing (some might say unfocused). There’s also the second chapter of Ecce Homo, “Why I Write Such Good Books” (lol) where he looks back at his whole career and sums it up, explains things that he objected to or has changed his perspective on, etc.

If anyone else violently disagrees with me and wants to call me a fool/give a different suggestion, please do

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nietzsche’s “Thus Spake Zarathustra” (part II/II)

❍❍❍

Iran between Zoroaster (زرتشت) and Islam

Last Thursday night (June 20th), Trump approved an attack on Iran after a US drone was shot down, yet he suddenly changed his mind and pulled back from the attack. (5) While Trump almost attacked Iran and started a new area of war and misery in the world, Iranians inside Iran and around the world are frightened by this escalation. Today, Iran’s Jewish community is the largest in the Mideast outside Israel – and feels safe and respected. (6)

Iranians in the diaspora have a variety of ethnicities, languages, religions, and political views but with different intensities, they all share the common Iranian-something else identity. There are many different political oppositions to the current Islamic Republic which in itself is one of the most straight-forward opponents of the United States hegemony and its imperial projects. Politically, Iranian Left has a wide spectrum; from the ultra-radical MEK which is supported by no one else but John Bolton, to Tudeh Party of Iran. Iranian right-wing opposition has also a wide gamut from ultra-right nationalists such as Persian Renaissance, Jason Reza Jorjani who hangs out with American white-supremacists Richard Spencer, to the good old monarchists, and of course the recent infamous Mohamad Tawhidi a fake Muslim cleric educated in Iran who is now a hero for the white-nationalists and Islamophobes. (7) (8)