#siege of Drogheda

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#OTD in 1650 – Kilkenny surrendered to Oliver Cromwell.

The success of Oliver Cromwell’s Irish campaign during the autumn of 1649 caused further divisions in the Marquis of Ormond’s Royalist-Confederate coalition. With the defeat of British and Scottish forces in Ulster and the defection of most of Lord Inchiquin’s Protestant troops to the Parliamentarians, Ormond was obliged to rely increasingly upon Catholic support. Early in December 1649, the…

View On WordPress

#Co. Kilkenny#Henry Ireton#Ireland#Irish Town#James Butler#Kilkenny Castle#Marquis of Ormond#Oliver Cromwell#Oliver Cromwell&039;s Model Army#River Nore#Siege of Drogheda#St John&039;s Bridge#Surrender of Kilkenny

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cromwell in Ireland, August-November 1649: ‘I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgement of God upon these barbarous wretches,’

Drogheda and Wexford

Cromwell in Drogheda. Source: GettyImages

THE SITUATION in Ireland which, since the initial eruption of the Old Irish rebellion in 1641, had stabilised into an armed truce between the Catholic Confederates on one side, and the Presbyterian Scots on the other, with the English garrisons under the Royalist Lord Lieutenant James Butler, Earl of Ormond, maintaining an uneasy neutrality. This state of affairs was completely altered by the execution of the King and the hasty establishment of an English Commonwealth under the Rump Parliament and the New Model Army. The Prince of Wales, now crowned King Charles II in Breda and in absentia in Edinburgh, cast his net wide in a search for allies to help him regain his father’s throne. Like Charles I, his exiled son hoped the Irish Confederates could perhaps provide him with the military resources he craved; equally, the Prince also made overtures to the Covenanter Scots, who had proved unexpectedly loyal to the House of Stuart; finally there was Ormond himself, an unequivocal English Royalist, whose small garrison forces also declared for Charles. Therefore in a matter of months, the various protagonists in the Irish rebellion found themselves effectively on the same side all, to a greater or lesser degree, proclaiming support for the exiled King, and opposition to the Commonwealth.

For Cromwell, the shifting alliances that had produced this unforeseen coalition, actually simplified matters. His task was now not simply to reconquer Ireland for the English Parliament, but to cleanse the country, not only of Popery, but also of Protestant schematics and recidivist King’s men. Cromwell’s sense of religious certainty and destiny was manifested in its purest sense during the Commonwealth assault on Ireland - with significant consequences for not only the immediate future of the country, but also for Ireland’s sense of itself in the centuries to come.

Cromwell led an army of 12,000 men into Ireland, mostly troops with experience of fighting in the two civil wars, and landed in Dublin on 14th August 1649. The fact he was able to do this with relative ease was not a given. Until recently, Dublin, garrisoned by soldiers loyal to the Parliament under the command of Colonel Michael Jones, had been besieged by Ormond’s Royalist forces. On 2nd August, Jones had led 4,000 of Dublin’s defenders on a daring sortie, catching the 19,000 strong besiegers completely by surprise and routed them at Rathmines, not only breaking the siege, but winning one of the most remarkable military victories of the British civil wars. For a delighted Cromwell, this scattering of the main Royalist army in Ireland was proof positive of divine favour and God’s support for his mission to extirpate the Catholic revolt and to avenge the atrocities of 1641.

From Dublin, Cromwell decided the next objective of the Commonwealth campaign would be the walled city of Drogheda, some thirty miles to the north. Drogheda was strongly fortified by Confederates and English Royalists, under the command of the veteran Royalist officer, the wooden-legged Sir Arthur Aston. It also straddled the River Boyne and in addition to being a major trading centre, also commanded the approaches to Ulster and the heartland of Scottish Presbyterianism in Ireland. Cromwell arrived before Drogheda on 3rd September. His invitations to the Irish/Royalist garrison to surrender were rejected after which Cromwell positioned his twelve field guns and eleven mortars, which had arrived by sea, on the rising ground surrounding the city. The bombardment began on 10th September soon after the refusal to surrender was received and by the end of the day, breaches had appeared in the walls. The following day, Cromwell ordered a full scale assault. The fighting was fierce and the New Model forces were initially repulsed, taking significant casualties. A second attack which Cromwell himself led personally, succeeded in entering the city. The gates were opened by the Commonwealth infantry and the New Model cavalry stormed in. Despite the fall of the city now only being a matter of time, the defenders, rallied by the indomitable Aston, refused to surrender and it was at this point an exasperated Cromwell ordered that no quarter be given to any men under arms. It was this order that sealed Cromwell’s reputation in Ireland as a cold-hearted killer and the taking of Drogheda as an atrocity.

There is no doubt that an order to give no quarter was highly unusual in the civil wars. Quarter was generally freely given in order to induce surrender and occasions where mercy was not shown were rarely as a result an official military order. Cromwell himself certainly viewed Catholicism as superstitious nonsense and the Irish as an uncivilised sub-species of humanity, guilty of massacres of Protestants, on whom clemency should not be wasted. It is also true that many of the New Model soldiers had been brutalised by seven years of near continuous fighting and needed little encouragement to kill their enemies. The lurid contemporary and later accounts of the slaughter of women and children by the attacking English soldiers are almost certainly false, but the killing of surrendering enemies was indefensible and a deserved blot on the character and reputation of Oliver Cromwell. The entire garrison, between 3,000 and 4,000 men, including Aston, was put to the sword.

Cromwell’s next target was the south eastern city of Wexford, chosen again for its strategic importance, particularly given its proximity to continental Europe and its potential as a rallying point for Royalists. The Commonwealth forces reached Wexford on 2nd October. The Irish garrison, emboldened by reinforcements sent by Ormond, refused terms and, like Drogheda before it, was subjected to heavy English bombardment. Negotiations between Cromwell and the city leaders however continued and it seemed likely at one point a settlement could have been reached, but this all changed when Captain James Stafford, commander of the castle at Wexford, dramatically surrendered, throwing open the gates to the Parliamentary besiegers. Fighting continued street by street, but the defenders were doomed. Unlike Drogheda no order to give no quarter was issued to the Commonwealth troops, but by then the precedent was set: all men under arms, including civilians and all Catholic priests caught, were killed. Over 2,000 men died, cut down by a remorseless enemy, or drowned trying to escape the massacre. Cromwell’s culpability for the extent of the death and destruction at Wexford is less easy to establish than at Drogheda, but he was unmoved by it, almost gleefully reporting later that ‘our forces… put all to the sword that came in their way.’

With the fall of Wexford, most of Munster and all lands between Cork and Dublin fell under Commonwealth control. The dreadful example of the two sacked cities led to many other garrisons surrendering without a fight or fleeing before Cromwell’s army reached them. The reconquest of Ireland was not complete, but the brutal taking of Drogheda and Wexford demonstrated the implacability of Cromwell’s mission in Ireland and ended any Royalist hopes that Ireland could be a realistic springboard for the return of the monarchy to England.

#english civil war#oliver cromwell#Cromwell in Ireland#siege of Drogheda#siege of Wexford#Cromwell’s atrocities

0 notes

Text

Today Cromwell will follow up the sack of Drogheda, the largest siege massacre in Irish history, with the sack of Wexford. The second largest siege massacre in Irish history.

-line from a podcast I probably shouldn't find the delivery of funny.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 9.11 (before 1840)

9 – The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest ends: The Roman Empire suffers the greatest defeat of its history and the Rhine is established as the border between the Empire and the so-called barbarians for the next four hundred years. 1185 – Isaac II Angelos kills Stephen Hagiochristophorites and then appeals to the people, resulting in the revolt that deposes Andronikos I Komnenos and places Isaac on the throne of the Byzantine Empire. 1297 – Battle of Stirling Bridge: Scots jointly led by William Wallace and Andrew Moray defeat the English. 1390 – Lithuanian Civil War (1389–92): The Teutonic Knights begin a five-week siege of Vilnius. 1541 – Santiago, Chile, is attacked by indigenous warriors, led by Michimalonco, to free eight indigenous chiefs held captive by the Spaniards. 1565 – Ottoman forces retreat from Malta ending the Great Siege of Malta. 1609 – Henry Hudson arrives on Manhattan Island and meets the indigenous people living there. 1649 – Siege of Drogheda ends: Oliver Cromwell's Parliamentarian troops take the town and execute its garrison. 1683 – Battle of Vienna: Coalition forces, including the famous winged Hussars, led by Polish King John III Sobieski lift the siege laid by Ottoman forces. 1697 – Battle of Zenta: a major engagement in the Great Turkish War (1683–1699) and one of the most decisive defeats in Ottoman history. 1708 – Charles XII of Sweden stops his march to conquer Moscow outside Smolensk, marking the turning point in the Great Northern War. The army is defeated nine months later in the Battle of Poltava, and the Swedish Empire ceases to be a major power. 1709 – Battle of Malplaquet: Great Britain, Netherlands, and Austria fight against France. 1714 – Siege of Barcelona: Barcelona, capital city of the Principality of Catalonia, surrenders to Spanish and French Bourbon armies in the War of the Spanish Succession. 1758 – Battle of Saint Cast: France repels British invasion during the Seven Years' War. 1775 – Benedict Arnold's expedition to Quebec leaves Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1776 – British–American peace conference on Staten Island fails to stop nascent American Revolutionary War. 1777 – American Revolutionary War: Battle of Brandywine: The British celebrate a major victory in Chester County, Pennsylvania. 1780 – American Revolutionary War: Sugarloaf massacre: A small detachment of militia from Northampton County, Pennsylvania, are attacked by Native Americans and Loyalists near Little Nescopeck Creek. 1786 – The beginning of the Annapolis Convention. 1789 – Alexander Hamilton is appointed the first United States Secretary of the Treasury. 1792 – The Hope Diamond is stolen along with other French crown jewels when six men break into the house where they are stored. 1800 – The Maltese National Congress Battalions are disbanded by British Civil Commissioner Alexander Ball. 1802 – France annexes the Kingdom of Piedmont. 1803 – The Battle of Delhi, during the Second Anglo-Maratha War, between British troops under General Lake, and Marathas of Scindia's army under General Louis Bourquin ends in a British victory. 1813 – War of 1812: British troops arrive in Mount Vernon and prepare to march to and invade Washington, D.C. 1814 – War of 1812: The climax of the Battle of Plattsburgh, a major United States victory in the war. 1826 – Captain William Morgan, an ex-freemason is arrested in Batavia, New York for debt after declaring that he would publish The Mysteries of Free Masonry, a book against Freemasonry. This sets into motion the events that led to his mysterious disappearance. 1829 – An expedition led by Isidro Barradas at Tampico, sent by the Spanish crown to retake Mexico, surrenders at the Battle of Tampico, marking the effective end of Spain's resistance to Mexico's campaign for independence. 1830 – Anti-Masonic Party convention; one of the first American political party conventions. 1836 – The Riograndense Republic is proclaimed by rebels after defeating Empire of Brazil's troops in the Battle of Seival, during the Ragamuffin War.

0 notes

Text

What Happened on September 11 in British History?

September 11 is a date that carries significant weight in British history, marked by pivotal military victories, cultural events, and international achievements. From the Battle of Stirling Bridge to Florence Chadwick’s swim across the English Channel, each event offers insight into the historical and cultural influence of Britain. This article delves into key moments that occurred on September 11, offering a comprehensive overview of the country’s military, cultural, and political contributions.

What Happened on September 11 in British History?

Battle at Stirling Bridge (1297)

On September 11, 1297, the Battle of Stirling Bridge took place, where Scottish forces led by William Wallace achieved a decisive victory over the English army. Wallace, along with fellow leader Andrew Moray, used the terrain and tactical ingenuity to defeat the much larger English force under John de Warenne, the Earl of Surrey, and Hugh de Cressingham. The narrow wooden bridge over the River Forth played a crucial role in the Scots’ success, as the English were forced to cross in small numbers, making them vulnerable to attack.

This battle was a turning point in the First War of Scottish Independence, with Wallace’s triumph inspiring further resistance against English rule. The victory at Stirling Bridge elevated Wallace to a national hero status and solidified his reputation as one of Scotland’s most significant historical figures. For England, the defeat was a humiliating setback and marked the beginning of a protracted struggle for control over Scotland.

New Model Army Occupies Bristol (1645)

On September 11, 1645, the New Model Army under the command of Thomas Fairfax occupied Bristol during the English Civil War. Bristol, one of the wealthiest cities in England at the time, was a strategic stronghold for the Royalists. The capture of the city was a significant blow to King Charles I’s forces. After a prolonged siege, Fairfax’s army, characterized by its discipline and organization, successfully breached the city’s defenses.

The occupation of Bristol was a major turning point in the war, weakening the Royalists’ control over the West Country. It demonstrated the effectiveness of the New Model Army, which would later play a pivotal role in the defeat of the Royalists and the eventual execution of King Charles I. Fairfax’s leadership, combined with the army’s discipline, contributed to the Parliamentary victory in the English Civil War.

Massacre of Drogheda (1649)

On September 11, 1649, Oliver Cromwell’s forces committed the Massacre of Drogheda in Ireland, killing approximately 3,000 Royalist soldiers and civilians. This event occurred during Cromwell’s campaign to subdue Ireland following the English Civil War. Drogheda, a Royalist stronghold, refused to surrender, prompting Cromwell to order a brutal assault. His forces breached the city’s walls, leading to widespread slaughter.

The massacre was intended to send a clear message to Royalist and Irish Catholic forces resisting Cromwell’s rule. While it achieved its immediate goal of securing Drogheda, the event is remembered as one of the most violent and controversial episodes in British and Irish history. It left a lasting legacy of bitterness and division between the Irish and the English, with Cromwell’s name remaining synonymous with cruelty in Irish collective memory.

Battle of Brandywine (1777)

On September 11, 1777, during the American Revolutionary War, British forces led by General Sir William Howe defeated American troops at the Battle of Brandywine in Pennsylvania. The British aimed to capture Philadelphia, the American capital at the time. Despite the loss, the Americans, under General George Washington, managed to avoid complete destruction, thanks in part to the efforts of Polish soldier Casimir Pulaski, who saved Washington’s life during the retreat.

The British victory at Brandywine was an important step towards their occupation of Philadelphia, but it did not end the American resistance. The battle demonstrated both the determination of the Continental Army and the strategic importance of international alliances, such as Pulaski’s contribution. For the British, the success at Brandywine was a tactical victory, but it ultimately failed to quell the growing revolutionary spirit in America.

British Open Golf (1862)

On September 11, 1862, the British Open Men’s Golf Championship was held at Prestwick Golf Club in Scotland, where Tom Morris Sr. retained his title. Morris, a legendary figure in the history of golf, defeated Willie Park Sr. by three strokes to win his second consecutive championship. The British Open, which began in 1860, is one of the oldest and most prestigious golf tournaments in the world, and Morris’s dominance during this period helped cement its importance in the sporting world.

Morris’s success at the British Open showcased his remarkable skill and contributed to the development of modern golf. His influence extended beyond his playing career, as he later became a prominent golf course designer and mentor to younger players. The 1862 British Open is a reminder of the deep roots of golf in Britain and its enduring global legacy.

Lindbergh’s War Claim (1941)

On September 11, 1941, American aviator Charles Lindbergh delivered a controversial speech in which he accused the “British, Jewish, and Roosevelt administration” of conspiring to draw the United States into World War II. Lindbergh, a leading figure in the isolationist movement in America, believed that the U.S. should avoid involvement in the conflict. His comments, made during a speech in Des Moines, Iowa, sparked outrage, particularly for their anti-Semitic undertones.

While not directly involving Britain, Lindbergh’s claims reflected the broader debate over U.S. involvement in the war, which Britain was already deeply engaged in. Britain’s leadership, particularly under Winston Churchill, was eager for American support in the fight against Nazi Germany. Lindbergh’s speech highlighted the tension between isolationist and interventionist sentiments in the U.S., which would ultimately shift in favor of intervention after the attack on Pearl Harbor later that year.

Florence Chadwick Swims the English Channel (1951)

On September 11, 1951, Florence Chadwick became the first woman to swim the English Channel from England to France, completing the journey in 16 hours and 19 minutes. Chadwick, an American swimmer, had previously attempted the swim in 1950 but was forced to abandon her effort due to poor conditions. Her successful swim in 1951 was a significant achievement in the world of long-distance swimming and a testament to her determination and endurance.

The English Channel has long been regarded as one of the most challenging open-water swims due to its cold temperatures, strong currents, and unpredictable weather. Chadwick’s feat drew international attention and inspired future generations of swimmers. Her swim on September 11 symbolized not only athletic prowess but also the enduring connection between Britain and the sport of open-water swimming.

British Film: Pride and Prejudice (2005)

On September 11, 2005, the film adaptation of Jane Austen’s classic novel Pride and Prejudice, directed by Joe Wright and starring Keira Knightley and Matthew Macfadyen, premiered at the Toronto Film Festival. This version of Austen’s novel received widespread acclaim for its performances, cinematography, and faithful adaptation of the beloved text. Knightley’s portrayal of Elizabeth Bennet was particularly praised, earning her an Academy Award nomination.

The film’s success reinforced Britain’s long-standing tradition of adapting its literary classics for the screen. Austen’s Pride and Prejudice has remained a cultural touchstone for British literature and film, and this 2005 adaptation brought the story to a new generation of viewers. Its premiere on September 11 marked the beginning of a successful theatrical run that cemented its place in British cinema.

The Martian Premieres (2015)

On September 11, 2015, Ridley Scott’s science fiction film The Martian premiered at the Toronto Film Festival. Based on the novel by Andy Weir, the film starred Matt Damon as an astronaut stranded on Mars and his efforts to survive while awaiting rescue. Although the film is set in space and focuses on American characters, Scott, a renowned British director, brought his signature visual style and storytelling expertise to the project, making it a global success.

The Martian was praised for its scientific accuracy, engaging plot, and Damon’s performance. The film’s premiere on September 11 was the beginning of its journey to becoming one of the most successful films of 2015, solidifying Scott’s reputation as one of Britain’s most accomplished filmmakers. The movie’s blend of science, survival, and human ingenuity resonated with audiences worldwide.

Conclusion

September 11 has seen a wide array of significant events in British history, from military victories and cultural milestones to international collaborations and athletic achievements. The Battle of Stirling Bridge, the occupation of Bristol, and the massacre at Drogheda highlight Britain’s complex military past, while the triumphs of athletes like Tom Morris Sr. and Florence Chadwick underscore the nation’s sporting heritage. Additionally, the premieres of Pride and Prejudice and The Martian reflect Britain’s lasting influence in the world of cinema. These moments offer a glimpse into the diverse and impactful history of Britain, marking September 11 as a day of remembrance and achievement.

0 notes

Photo

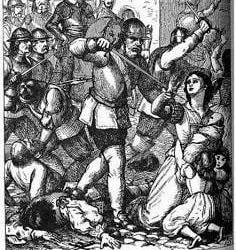

Massacre at Drogheda to print the book "History of Ireland from 400 to 1800" - Henry Edward Doyle

The siege of Drogheda or the Drogheda massacre took place 3–11 September 1649, at the outset of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. The coastal town of Drogheda was held by the Irish Catholic Confederation and English Royalists under the command of Sir Arthur Aston when it was besieged by Parliamentarian forces under Oliver Cromwell. After Aston rejected an invitation to surrender, the town was stormed and much of the garrison was executed including an unknown but "significant number" of civilians. The outcome of the siege and the extent to which civilians were targeted is a significant topic of debate among historians.

#siege of Drogheda#Drogheda massacre#Oliver Cromwell#Sir Arthur Aston#XVII century#english civil war#henry edward doyale#Illustration#art#arte#irish history#british history

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh today in history we did an activity where we compared lil ol' Max to fuckhead McGee Oliver Cromwell

Imma be honest I was pretty hurt by the very notion of it?? Like I fucking hate Cromwell so fucking much, and Max is a sweetie and on a good day I might die for him..

#And the shit people came up with? The similarities outweighed the differences so much with shit like#'both massacred eg siege of Drogheda and killings in Vendée' like whoah what?#And some nut came up with 'both driven by religion' explaining that Robespierre was driven by his cult and focused on himself??#bunch of fucks#i balanced it a lil by adding two differences#seriously hate cromwell though..#fuck that guy#also can i ask that no one like comments arguments for this or whatever because i seriously hate cromwell too much#thaaanks

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jan Wyck - The Battle of the Boyne, 1 July 1690 -

oil on panel, Height: 76.2 cm (30 in); Width: 106.7 cm (42 in)

National Army Museum, London, UK

The Battle of the Boyne was a battle in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II of England and Ireland, VII of Scotland, versus those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and James's daughter), had acceded to the Crowns of England and Scotland in 1689. The battle took place across the River Boyne close to the town of Drogheda in the Kingdom of Ireland, modern-day Republic of Ireland, and resulted in a victory for William. This turned the tide in James's failed attempt to regain the British crown and ultimately aided in ensuring the continued Protestant ascendancy in Ireland.

The battle took place on 1 July 1690 O.S. William's forces defeated James's army, which consisted mostly of raw recruits. Although the Williamite War in Ireland continued until the signing of the Treaty of Limerick in October 1691, James fled to France after the Boyne, never to return.

Jan Wyck (also Jan Wiyck or Jan Wick) (29 October 1645 – 17 May 1702) was a Dutch baroque painter, best known for his works on military subjects. There are still over 150 of his works known to be in existence.

As the son of a fairly successful artist, it is likely Wyck was painting and drawing from a young age. Enjoying the patronage of the Duke of Ormond Wyck was known as the best landscape painter in London by 1686. By the time William III of England ascended to the throne, Wyck was also enjoying the patronage of the Duke of Monmouth. He painted a portrait of Monmouth on horseback in the 1670s, as well as many depictions of him in battle, such as at the Siege of Maastricht in 1673, and at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge in 1679.

Wyck was placed upon the committee of Acting Painters of the Painter-Stainers' Company on 24 November 1680, which was a recognition of his rising talent. He first made a public name for himself when he accompanied fellow Dutch painter Dirk Maas to Ireland to paint the campaigns of William III. Maas had received a commission from King William to paint the Battle of the Boyne, and, although it is not known if he was also present at the battle, Wyck also painted many scenes from the battle. Throughout the 1690s, he is known to have created at least half a dozen oils of the battle, as well as countless battle pieces, encampments and equestrian portraits of soldiers before battle.

William was impressed with his work, and commissioned him to paint himself, which he did many times, often in equestrian poses. William had soon also called upon Wyck to depict countless scenes of his campaigns throughout the low countries during the Nine Years' War (also known as King William's War), including the Siege of Namur, and the Siege of Naarden.

Other scenes he painted include the Siege of Derry (1689), and the horse and battle portion of Godfrey Kneller's famous portrait of the Duke of Schomberg, who had been killed at the Battle of the Boyne.

Wyck's works are notable for their flair and colour, as well as the excellent attention to detail. He highlights features such as flourishing sabres, firing muskets, flaring horses nostrils and cannons spouting flames. But most importantly he brought the viewer into the battle at a time when the prevailing trend was to present birds-eye views over a battle, showing disposition and locations of troop formations. He personalised the soldiers, and created an atmospheric presentation of the scenes depicted. He also celebrated notable commanders and recognisable figures within his works, a feature that made him popular with those commissioning works.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had no idea what the battle of Dunbar was so I took myself to wikipedia and while I obviously have no idea what I am talking about, here were some things I gleaned that I imagined could be connected to Aziraphale and Crowley.

the battle is between English and Scottish forces (more scottish accent Crowley please)

Oliver Cromwell (leading the English forces) apparently talked a big game about God but was also ruthless and horrible (sounds like Upstairs to meee) and said shit like "I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches" after killing 3500+ people including civilians at the Siege of Drogheda in Ireland in 1649, while Irish clerics described it as "unparalleled savagery and treachery beyond any slaughterhouse."

a couple months before the battle of Dunbar, Oliver Cromwell tried to get the Scots to fight him but they went scorched earth and withdrew to Edinburgh to wait out the english army. The english army faced bad weather, scant supplies, and plenty of dysentery and fevers. At the end of August the english pulled back and marched to Dunbar, but the Scots pursued and outflanked them and took the strategic high ground position (obi-wan move) of Doon Hill. Oliver Cromwell wrote a letter to the governor of Newcastle saying: "The enemy hath blocked up our way at the pass at Copperspath, through which we cannot get without almost a miracle. He lieth so upon the hills that we know not how to come that way without great difficulty; and our lying here daily consumeth our men who fall sick beyond imagination." (This just sounds like a great time for Aziraphale to misguidedly want to help the english forces)

While Doon Hill was higher up it was also very exposed to the shit weather. (one of the scottish soldiers said it was "a drakie nycht full of wind and weit" [a dark night full of wind and wet]) The wiki article says as a result there was a council of war held of which "there is no record of the discussion, nor certainty as to the attendees and survivors gave differing accounts." But after it, the Scots decide to move off the hill, giving the English a chance at open battle. Fighting ensues, and the much smaller english forces essentially defeat the Scots, forcing the remaining scottish forces to retreat back to Edinburgh. (Aziraphale could absolutely have messed with discussions at the war council, leading to the mystery around what actually happened there)

anyway I'm not saying this is for sure what happened in 1650 but say Crowley was just around, thwarting, and he and Aziraphale had talks about why Heaven was backing Cromwell, and Aziraphale was all "woo god and unity you wouldn't understand" and then he meddles and it turns out very differently than he thought and maybe he didn't know how ruthless Cromwell was but he'd already been a self-righteous jerk to Crowley about it?

This is probably more just european military history-themed fanfic at this point, and I imagine most old battles had something to do with religion bc that's a popular excuse for violence, but it was an interesting rabbit hole to fall into.

I did the "I was wrong" dance in 1650...

What did you do at the battle of Dunbar, Aziraphale?!

#good omens theory#i was wrong dance#good omens 2#aziraphale#crowley#gos2 spoilers#gos2#good omens spoilers#good omens#ineffable husbands#ineffable partners#ineffable spouses

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two sides to every story

So....I just saw a repost by a blogger who usually posts sympathetically about Outlander, about bigotted Ulster Unionists, which came with a slew of comments about how dreadful they are, f*cking British colonists, and with even more comments below about how everything about the English is wrong and how horrid we were and are because of our history as slavers and genocidal colonials, cultural vandals and ruthless Imperialists (rich if some of that is coming from American bloggers, but that’s another story)

I try not to get involved in politics on my blog , least of all the god-awful politics of Northern Ireland, that benighted but beautiful corner of the Emerald Isle that is torn by ethnic and sectarian conflicts that have been intractable for, what, 400 years? Usually the comments I read on Tumblr about the horrors of the British Empire and how beastly the English have been and STILL ARE, pass me by. If you are English you get used to being the world’s whipping boy for every real or imagined sin of your slave freeing, democracy promoting Nazi defeating ancestors. No one much liked the Romans, either, the bastards. What did they ever do for us?

But in this case I have, as they say, skin in the game. MY Irish ancestors were Southern Irish whose family had been in Ireland probably before the Mayflower; I don’t know. They certainly thought of themselves as Irish and sounded Irish, but their names were not Mcthis or O’that, so I assume they were ‘planted’ at some time. Like 10% of pre-Independence Ireland they were Protestants, and like many they were driven out of Ireland during and after the civil war; their houses burned, their people intimidated or murdered, their churches now ruins, in a determined bout of Bosnian style ethno-social cleansing that Republian Ireland would much rather forget.

The Protestant population of the Republic of Ireland now stands at about 2%

“Over a large part of the country the already sparse congregations are being reduced to vanishing point – memories of the ‘terror’ have burnt very deep – anyone who knows Southern Ireland knows also the undercurrent of feeling urging the elimination of Protestantism ... the fact remains that a migration of younger clergy has begun.” - 1921 Church of Ireland Report

The future of Ireland in the 1920s and the 1930s under de Valera, as I read, was of a closed, priest ridden society that harked back to a mythical time of agrarian self-sufficiency, a sort of Kim Il Jong ‘juche’ ideology in the Atlantic ocean, an Ireland where regardless of their tradition every school child was forced to learn Irish Gaelic, that indispensible international tool for a largely Anglophone country. It was an introverted Ireland which for fifty years seemed largely cut itself off from the rest of the world, (until Ireland joined the European Union and became a ‘Celtic Tiger’) . An Ireland whose leadership, in order to spite Britain, declared Ireland neutral in the struggle against the worst tyranny the world had then ever seen, and whose leader signed a book of condolences at the German Embassy when he learned that Adolf Hitler was dead. As you would.

Unsurprisingly MY Protestant Irish ancestors felt persecuted and the whole lot fled to the welcoming arms of Australia, back in the 1920s. . You can learn more about the fate of the Southern Irish protestants in the book ‘Buried Lives, the Protestants of Southern Ireland”, by Robin Bury.

Like I say, there are two sides to every story. You’ve heard and you will hear a lot about how terrible the English were in Ireland and I’m sure most of it is all too true. You’ll hear about Cromwell, the massacres of Drogheda and Wexford, the Irish Famine, the absentee landlords, the gallant Fenians of 1798 and the Easter Rising and all. You’ll hear about the struggle for civil rights and about the English boot trampling on the neck of the oppressed peasantry and those gallant IRA boyos fighting to free the six counties from John Bull’s tyranny.

You won’t hear about the Portadown massacres in Ulster, or the Protestants dragged from their homes and massacred in Cork, or driven into the night with their homes blazing behind them, or the Ulster protestants blown to pieces in Enniskillen on Remembrance Sunday. You wouldn’t understand the siege mentality of a people clinging to their identity against the flood tide of history.

But then, to be fair, you probably won’t hear about the 50,000 brave Irishmen (some sources put the figure much higher) who volunteered to fight for Britain against Hitler and were shunned by the Irish government on their return, their contribution to the fight against fascism and Naziism ignored by official Ireland until 1995.

You certainly won’t hear about the grenade they threw into my grannie’s garden in Dublin, and if you did, I’m sure you could justify it. They were unionists, after all, even if they didn’t speak with that strange strangulated accent of the Ulster Unionist politicians that we all find so off-putting, or beat the Lambegh drum and sing ‘The sash my father wore and bait the Taigs every summer.

But, like I say, there’s two sides to every story. Now I’ll get off my soap-box and wait for the brick-bats. Filthy English scum that I am.

(Thank God, I also have Scottish ancestry too, unsullied by any profits from English Imperialism! Like most people with a Scottish connection I now keep very quiet about the plantations in the West Indies, the ranches in Canada and the properties in Australia and New Zealand, and the careers they made in the Honorable East India Company, which generated the money that built all those fine neo-Classical houses in Edinburgh and Ayrshire and those Scottish Baronial Castles so beloved of tourists)

#two sides to every story

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Defeat of Irish Royalism, 1650: ‘We are come to break the power of a company of lawless rebels who… live as enemies of human society,’

The End of the Confederate Rebellion

Source: Wikipedia

IN LATE 1649 Cromwell made overtures to the Irish Confederates, but they were couched in the language of uncompromising Puritanism. The Parliamentary general issued his declaration in response to a rallying cry from the Irish Church to the whole of Ireland to encourage resistance to the English invasion and to support the cause of the King. Cromwell proclaimed that the Irish would be treated leniently; that their lands would not be confiscated, and that there would be no judicial punishment for their rebellion. However, all the rebels heard was the unforgiving righteousness of the Calvinist godly: because Cromwell added that in order for there to be a peaceable end to the rebellion, the Catholics would have to give up their fight and their religion, their support for the king and to accept an imposed Protestant settlement on their country. Perhaps Cromwell thought his declarations reasonable in the context of a bitter civil war that had allegedly seen massacres of Protestant settlers by the rebels. However, to the supporters of a nine year nationalist rebellion rooted in the Roman Catholic religion, his words were those of conqueror to the vanquished.

So the war continued. In January 1650, a reinforced Cromwell continued his campaign of reducing Royalist and Confederate strongholds one by one. In contrast to the atrocities committed at Drogheda and Wexford, and to Cromwell’s subsequent baleful reputation in Ireland, he offered generous terms to defenders, permitting them to march out of surrendered towns and castles under arms and with banners flying. This way the Commonwealth forces were able to capture Fethard, Cashel and Cahir in quick succession. The route was then open for a march on Kilkenny, the capital of the Confederate rebellion. In March 1650, Cromwell invested the city. After five days of negotiations, the Confederate commander agreed to surrender the city and the garrison vacated Kilkenny, marching away with full honours and the centre of the rebellion was, rather suddenly, in English hands.

With the loss of Kilkenny, Ormond knew that the Royalist cause in Ireland was almost spent, but if Charles I’s former Lord Lieutenant despaired of now being able to aid his sovereign’s son to the throne, Cromwell himself was not so sanguine. He believed the danger of invasion from Ireland remained the greatest threat to the longevity of the upstart Commonwealth, for all Charles II’s rumoured courting of the Scots. Despite the absence of any rebel field army worth the name, the Confederates continued to hold several strongholds, all well garrisoned and therefore, from Cromwell’s perspective, comprising the core of a potential Royalist revival. The Parliamentary general resolved not to leave Ireland until each and every hold out had been reduced.

Cromwell began his campaign with Clonmel, a walled city in the south under the command of the formidable Hugh Dubh (“Black Hugh”) O’Neill, a veteran on the Catholic side of the Thirty Years’ War, known for both his military skill and his strategic cunning. O’Neill led an experienced garrison of 1500 rebels and had the support of the townspeople to resist the invaders and so when Cromwell arrived before the walls of Clonmel on 27th April and offered terms, Black Hugh refused to negotiate and a siege commenced. Cromwell concentrated artillery on the hills overlooking the city from the north and began a bombardment. Morale within the town however remained high and O’Neill sent several sorties out to attack the besiegers and disrupt their supply and communication lines. The rebel commander lived in hope that if he could tie down the Commonwealth forces long enough, Ormond may yet put a Royalist army into the field and come to his relief.

This was a folorn hope, but Black Hugh made the best of his situation. By the middle of May, the English gunners had made a major breach in Clonmel’s walls. It seemed the fall of the city was imminent and on the 17th, Cromwell ordered his infantry to advance into the breach. Unknown to the Parliamentary commander, O’Neill had turned this tactical disadvantage into an ambush. He had his men construct a makeshift wall around the edge of the breach, and secreted canon and sharpshooters within the new defensive line. As Cromwell’s forces surged forward, they were met by withering artillery and musket fire that cut them down in their droves. After an hour of one-sided combat, over a thousand New Model troopers lay dead or dying in the killing ground. When Cromwell arrived personally to oversee what he expected to be the final street by street battle for the town, he found his men in retreat and Clonmel still defiant. Black Hugh had arguably inflicted the only defeat suffered by Cromwell in his lengthy career fighting in the many and varied British Civil Wars.

However, O’Neill knew the chances of repeating this success were limited. With ammunition and food running low, and the continuance of the bombardment assured, he took the view that Clonmel was impossible to hold. That night he and his remaining soldiers slipped out of the city and made their way to Waterford. On the 18th a frustrated Cromwell took the surrender of the city from the town’s mayor - a victory perhaps, but one that probably felt like a defeat. Nontheless, however hard won, the taking of Clonmel effectively ended Royalist hopes in Ireland and Charles indeed gave up the slim hope that Ormond’s forces could be the vehicle for a restored monarchy. The Rump Parliament agreed. Their nervousness was focused entirely now on the danger from Scotland and they wanted their all-conquering general home, despite the fact the Catholic rebellion was not fully suppressed. On 29th May, Cromwell left Ireland and returned to London to a hero’s welcome. The task of stamping out the last of the Catholic rebellion, which would carry on for a further two years, fell to Cromwell’s fellow Grandee, Henry Ireton, who would eventually die in this, his last campaign in the Parliamentary cause.

Cromwell could count his Irish campaign a success. In just nine months he had destroyed Royalist hopes in Ireland and fatally crippled the Confederate rebellion but at lasting cost to his reputation. If the atrocities at Drogheda and Wexford were exaggerated and there is also evidence elsewhere of Cromwell’s leniency and political skill, there is no doubt the behaviour of the general and his army to the Irish was brutal and contemptuous in equal measure. And if there is little or no evidence of deliberate wholesale massacre of non combatants in the two notorious sieges, the cold-eyed killing of the entire garrisons of each city, whether the men were fighting or surrendering, is enough to justifiably condemn Cromwell as a callous military murderer for posterity.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

King William III off the coast of Ireland, June 1690, with an English Royal Yacht and the Lord High Admiral’s first-rate flying the Royal Standard by William Vanderhagen (1722 - 1745)

William III set sail for Ireland with the English Fleet in the second week of June 1690, arriving off Carrickfergus on June 14th. Here he landed before proceeding to Belfast where he took command of his army and proceeded towards Drogheda.

On the 30th June he faced the combined French and Irish armies of King James II across the River Boyne, where the battle and subsequent rout of the Catholic party took place the following day.

William himself was slightly wounded in the battle, which was the seminal event in Irish history, and which established the Protestant ascendancy for many years to come. It also effectively marked the end of King James’s hopes of re-establishing himself on the English throne. After proceeding to Dublin where he entered the City in triumph, he advanced against Limerick, but failed to convert his siege there into capitulation. He returned from County Cork in July after less than two months’ campaigning with his throne effectively safe from further opposition.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 9.11 (before 1900)

9 – The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest ends: The Roman Empire suffers the greatest defeat of its history and the Rhine is established as the border between the Empire and the so-called barbarians for the next four hundred years. 1185 – Isaac II Angelos kills Stephen Hagiochristophorites and then appeals to the people, resulting in the revolt that deposes Andronikos I Komnenos and places Isaac on the throne of the Byzantine Empire. 1297 – Battle of Stirling Bridge: Scots jointly led by William Wallace and Andrew Moray defeat the English. 1390 – Lithuanian Civil War (1389–92): The Teutonic Knights begin a five-week siege of Vilnius. 1541 – Santiago, Chile, is attacked by indigenous warriors, led by Michimalonco, to free eight indigenous chiefs held captive by the Spaniards. 1565 – Ottoman forces retreat from Malta ending the Great Siege of Malta. 1609 – Henry Hudson arrives on Manhattan Island and meets the indigenous people living there. 1649 – Siege of Drogheda ends: Oliver Cromwell's Parliamentarian troops take the town and execute its garrison. 1683 – Battle of Vienna: Coalition forces, including the famous winged Hussars, led by Polish King John III Sobieski lift the siege laid by Ottoman forces. 1697 – Battle of Zenta: a major engagement in the Great Turkish War (1683–1699) and one of the most decisive defeats in Ottoman history. 1708 – Charles XII of Sweden stops his march to conquer Moscow outside Smolensk, marking the turning point in the Great Northern War. The army is defeated nine months later in the Battle of Poltava, and the Swedish Empire ceases to be a major power. 1709 – Battle of Malplaquet: Great Britain, Netherlands, and Austria fight against France. 1714 – Siege of Barcelona: Barcelona, capital city of Catalonia, surrenders to Spanish and French Bourbon armies in the War of the Spanish Succession. 1758 – Battle of Saint Cast: France repels British invasion during the Seven Years' War. 1775 – Benedict Arnold's expedition to Quebec leaves Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1776 – British–American peace conference on Staten Island fails to stop nascent American Revolutionary War. 1777 – American Revolutionary War: Battle of Brandywine: The British celebrate a major victory in Chester County, Pennsylvania. 1780 – American Revolutionary War: Sugarloaf massacre: A small detachment of militia from Northampton County, Pennsylvania, are attacked by Native Americans and Loyalists near Little Nescopeck Creek. 1786 – The beginning of the Annapolis Convention. 1789 – Alexander Hamilton is appointed the first United States Secretary of the Treasury. 1792 – The Hope Diamond is stolen along with other French crown jewels when six men break into the house where they are stored. 1800 – The Maltese National Congress Battalions are disbanded by British Civil Commissioner Alexander Ball. 1802 – France annexes the Kingdom of Piedmont. 1803 – Battle of Delhi, during the Second Anglo-Maratha War, between British troops under General Lake, and Marathas of Scindia's army under General Louis Bourquin. 1813 – War of 1812: British troops arrive in Mount Vernon and prepare to march to and invade Washington, D.C. 1814 – War of 1812: The climax of the Battle of Plattsburgh, a major United States victory in the war. 1836 – The Riograndense Republic is proclaimed by rebels after defeating Empire of Brazil's troops in the Battle of Seival, during the Ragamuffin War. 1851 – Christiana Resistance: Escaped slaves led by William Parker fight off and kill a slave owner who, with a federal marshal and an armed party, sought to seize three of his former slaves in Christiana, Pennsylvania, thereby creating a cause célèbre between slavery proponents and abolitionists. 1852 – Outbreak of Revolution of September 11 resulting in the State of Buenos Aires declaring independence as a Republic. 1857 – The Mountain Meadows massacre: Mormon settlers and Paiutes massacre 120 pioneers at Mountain Meadows, Utah. 1897 – After months of pursuit, generals of Menelik II of Ethiopia capture Gaki Sherocho, the last king of the Kaffa.

0 notes

Text

headcanon ; scars

( content warning for discussion of uh, scars, and some brief descriptions of early modern torture methods )

Personifying a nation with a past rife with oppression and upheaval, Ciarán has more than a few scars. Unsurprisingly, almost all of them come from conflict with England.

The most prominent of these is across his throat-- if you’ve ever seen Inglourious Basterds, Brad Pitt’s character has a scar like this. Ciarán got it while being interrogated by the British army after the failed Rebellion of 1798. Half-hanging was a favorite method of torture employed against members and suspected supporters of the Society of United Irishmen, wherein a rope is pulled across the victim’s neck until unconscious and slackened, with the victim being revived each time and the process repeated. Ciarán was one of many Irishmen, Catholic and Protestant alike, who, inspired by the revolt in America and supported by Britain’s long-time rival, France, joined the United Irishmen in taking up arms against the British authorities in Ireland. He continued to fight as a guerrilla, hiding in the Wicklow Mountains until the autumn of that year, when the leader of his band, Joseph Holt, was forced into surrender. Ciarán was subsequently imprisoned and tortured for information that he refused to give.

He has a mostly healed burn scar going up the back of his left leg from the Siege of Drogheda, during the earlier Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, which left thousands of Irish dead and even more forced to leave their homes. During the siege, Oliver Cromwell’s forces fired indiscriminately upon civilians and then set fire to the churches they sought shelter in. This was in addition to catching the plague within the next year or so; the horrible conditions brought on by four years of non-stop warfare brought a particularly virulent outbreak of the Black Death to Ireland. Cromwell’s invasion of the island led to a population drop with estimates ranging from a modest 15% to a devastating 83%.

He has another scar on his other leg, this one being a bullet wound on his outer thigh from being hit with an incendiary round during the 1916 Easter Rising. It healed fast enough for him enlist with the guerrilla forces by 1919. During the subsequent war for independence, a blow to the face from a Black and Tan (the name given to the notoriously brutal British soldiers recruited to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary) broke his nose and left it slightly crooked.

#( 03. — nothing to see here ; ooc. )#( 02. — i made my song a coat ; headcanon. )#( i have some more ideas i need to mull over but these are my set in stone ones )

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in 1649, the Sack of Wexford took place. After a ten-day siege, English New Model Army troops (under Oliver Cromwell) stormed the town of Wexford, killing over 2,000 Irish Confederate troops and 1,500 civilians. The English Parliamentarian troops broke into the town while the commander of the garrison was trying to negotiate a surrender - massacring soldiers and civilians alike. Along with the Siege of Drogheda, the sack of Wexford is still remembered in Ireland as an infamous atrocity.

0 notes

Photo

The Siege of Drogheda took place on 3–11 September 1649, at the outset of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. The coastal town of Drogheda was held by the Irish Catholic Confederation and English Royalists under the command of Sir Arthur Aston when it was besieged by Parliamentarian forces under Oliver Cromwell. After Aston rejected an invitation to surrender, the town was stormed and much of the garrison was executed including an unknown but "significant number" of civilians. The outcome of the siege and the extent to which civilians were targeted is a significant topic of debate among historians. . . . . . #siegeofdrogheda #olivercromwell #drogheda #ireland #war #history #historicalreminder https://www.instagram.com/p/CE_CPS8Bsoo/?igshid=1fgh42plncwxv

0 notes