#street railways

Text

"The SDPC [Social Democractic Party of Canada] at the Lakehead appears not to have been content merely to contest elections. In 1912, having recently formed a union, the mostly immigrant workers of the Canadian Northern Coal and Ore Dock Company went on strike for better wages, hours, and working conditions. Bloodshed resulted when company officials, using local police and the militia, tried to suppress the striking coal handlers. The chief of police, two constables, and two Italian strikers were wounded. Fearing a general strike, the CNR quickly acquiesced to the demands of the coal handlers.

There was much in this incident that recalled earlier labour strife at the Lakehead. A new element, however, was the growing influence of radical socialists, who were thought to have sway over the coal handlers and to have been instrumental in their inclusion in the trade union movement. Prominent among the activists were “members of the Social Democratic Party of Canada,” including the party’s organizers for Port Arthur and Fort William, the Cobalt miners’ union leader James P. McGuire and the Reverend William Madison Hicks, as well as Herbert Barker, a volunteer organizer for the AFL. In April 1912, the three men led a number of English-speaking socialists in Fort William in establishing Ontario Local 51 of the SDPC. Initial members also included W.J. Carter; an architect named Richard Lockhead; Sid Wilson, a member of the British-based Amalgamated Carpenters; and Fred Moore, owner of the printing press that printed Urry’s The Wage Earner. Significantly, most of the members appear to have been Finnish or Ukrainian.

Before the strike, members of the Fort William SDPC had spoken at meetings of the coal handlers and, in the case of Hicks, played an active role by leading a parade of workers in confronting Port Arthur mayor S.W. Ray on his way to read the Riot Act to the strikers. The meeting between the two men and the violence that ensued were coincidental, according to Morrison, as

the Social Democratic party posed no real or imagined menace to the citizens of Port Arthur … what alarmed the English-speaking community was the newly won influence of the socialists with the immigrant workers.

Supporters of the ILP [Independent Labour Party] of New Ontario such as Urry found themselves “at odds with radical socialism” as

not only had the socialists played a prominent part in the strike,

though not the riot, but they were also attempting to organize Thunder Bay’s entire waterfront.

...

Calls for Hicks’s arrest began to appear in newspapers in both cities and the surrounding countryside. On 1 August 1912, officials arrested him for his role in a “tumultuous assembly … likely to promote a breach of the public peace.” Shortly after Hicks’s arrest and conviction (although he received a suspended sentence), SDPC organizers began an active campaign to take control, or at the very least undermine, the ILP-led Trades and Labour Councils. Following the strike, they sought to stage a general strike on the waterfront and, ideally, spread it throughout both Port Arthur and Fort William. As Jean Morrison writes, however, this was “a move disparaged by the British labour men for its disregard of the law which required negotiations and conciliation preceding strikes by transportation workers.” The attempt failed and widened the rift formed during the municipal, provincial, and federal elections of 1908 and 1911 and the labour unrest earlier in 1912.

...

The SDPC was also not left untouched. In preparation for the 1913 Fort William civic election, Urry and Hicks jointly developed in opposition to the SDPC a manifesto describing the class struggle in general and the issues facing the region’s workers in particular .... On the recommendation of the Elk Lake, Porcupine, and Cobalt locals that Hicks be expelled, the matter was referred to the Fort William membership. Despite facing the possibility that its charter would be revoked, Local 51 refused to expel Hicks and launched a vigorous defence on his behalf. The convincing agitator had a coterie of true believers, who “defended him to the last ditch refusing to believe that Hicks would do anything wrong.” He also had his critics, evidently including the 400-strong Fort William branch, which, it appears, sided with the Dominion Executive and expelled Hicks.

...

With Hicks departed one highly personalized version of a response to the ambiguous legacy of Lakehead socialism. Both the ILP and the SDPC grew rapidly during 1913. The labour councils in the twin cities began to discuss unity, in the form of construction of a joint Central Labour Temple. The Finnish branch of the SDPC in Port Arthur also called out for working-class and socialist unity. Moreover, as a more tangible indication of potential unification of the socialist and labour movements, SDPC organizer Herbert Barker was elected president of the Port Arthur Trades and Labour Council in April 1913.

As so often proved to be the case, however, such incipient unity was challenged by the region’s sheer class volatility. The strike by street railway workers in May 1913 was a volcanic moment. As David Bercuson writes:

The walk-out provided a focal point for much of the hatred and bitterness that had developed between labour and its enemies in the twin cities for several years.

Rioting and violence were sparked by the CPR’s attempts to use strikebreakers. When strikers overturned a streetcar operated by strikebreakers, police arrested one of the participants and, when a crowd tried to get him out of jail, fired into the crowd, killing a bystander. Local newspapers tried to pin the violence on the socialists, who were allegedly responsible for agitating the crowd.

The railway workers belonged to the Trades and Labour Councils in both cities and, in a show of solidarity, both councils called for a general sympathy strike. These calls went unheeded and most workers returned to work after four days of protest. In response, Urry, James Booker, McGuire, Bryan, and many members of the SDPC met at the Finnish Labour Temple. They criticized the local trades and labour councils “for not being radical enough to resist the ruling of an unscrupulous upper class.” They hoped the councils would become “more radical.” Not surprisingly, the obviously inflamed right-wing media in the twin cities characterized the meeting as one of “sedition, anarchy, socialism, violence and most everything else calculated to worry orderly society and responsible government.”

It was not a critique of the Lakehead workers reserved for the mainstream press. Mayor John Oliver of Port Arthur summed up the situation well when he argued that the continued unrest in Port Arthur and Fort William was not wholly due to working conditions. Making specific mention of the strikes of 1909, 1912, and 1913, he suggested that the unrest had been the result of socialist agitators. Oliver wrote:

There is hardly a night in the week that inflammatory speeches have not been made by several agitators … something will have to be done to either remove them or check their actions.

Interestingly, Frederick Urry and J.P. McGuire were specifically named for their alleged advocacy of a general strike. McGuire was further singled out for his reputed suggestion that it would be an easy thing to cut telephone, telegraph, and electric lines."

- Michel S. Beaulieu, Labour at the Lakehead: Ethnicity, Socialism, and Politics, 1900-35. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2011. p. 37-38, 40-42

#thunder bay#fort william#port arthur#strike#freight handlers#railway workers#immigrant workers#street railways#immigration to canada#canadian socialism#anglo canadians#xenophobia in canada#finnish immigration to canada#ukrainian immigration to canada#coal handlers#northwestern ontario#reading 2024#academic quote#labour at the lakehead#working class history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#nara#japan#street photography#original photographers#artists on tumblr#photographers on tumblr#portra#nihon#nippon#canon#g5xm2#trains#railways#yellow#blue

654 notes

·

View notes

Text

productive last night this was actually takennon a macbook Lol

#tunnel#dark#train tracks#railway#dereality#dreamcore#weirdcore#esoteric#oddcore#liminal spaces#liminality#liminal aesthetic#photography#streetscape#stockholm#street photography#urban photography#urban landscape#urban#landscape

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tokyo Sakura Tram

Minowabashi, Tokyo, Japan

#photographers on tumblr#railway#tram#architecture#tokyo#japan#street car#streets#street photography#trams#trains#tokyo sakura tram#original photographers#original photography#vertical#toden arakawa line#minowabashi#東京さくらトラム#都電荒川線

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flinders Street Railway Station, Melbourne, Australia: Flinders Street railway station is a train station located on the corner of Flinders and Swanston streets in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It is the busiest train station in Victoria, serving the entire metropolitan rail network, 15 tram routes travelling to and from the city, as well as some country and regional V/Line services to eastern Victoria. Wikipedia

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Subway stations, like melodies inscribed in memories. 🎶🚇✨

#BMT Broadway Line#Midtown Manhattan#Fifth Avenue#59th Street Station#New York City Subway#Railway Station#Nightlife#Trains#New York City#Grand Army Plaza#Manhattan#New York

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liverpool Street station. London, December 2023.

#black and white photography#city photography#elizabeth line#iphone photography#liverpool street station#london#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#photography#railway station#train station#urban photography

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

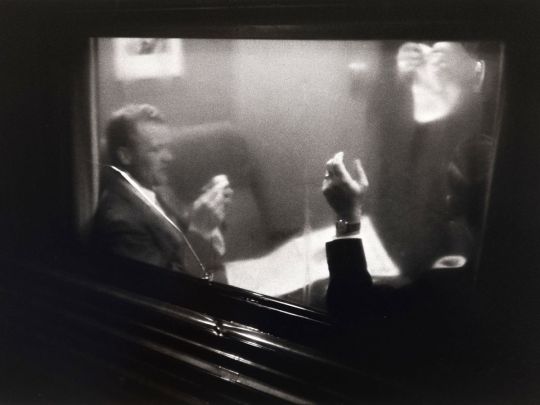

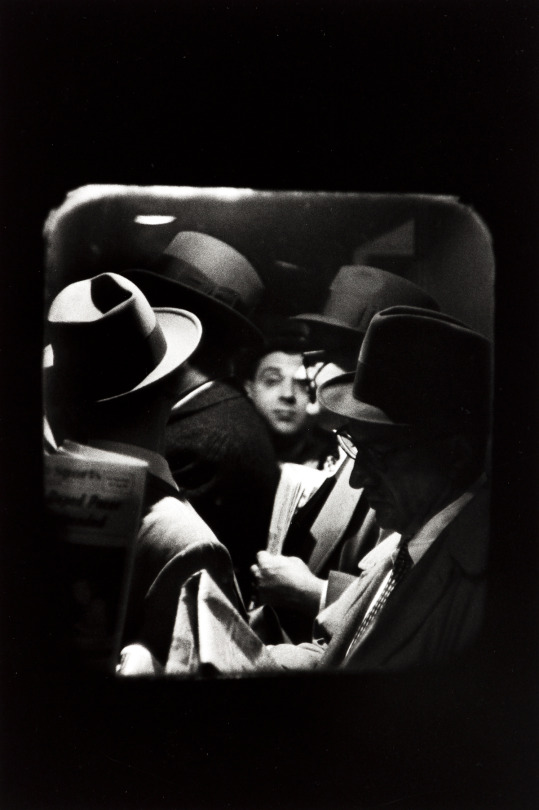

Louis Stettner - Photos from the Penn Station, 1958.

221 notes

·

View notes

Text

06.2018 Hamburg

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shibuya, Tokyo. February 2024. 15347

(via 2024-06 - Sandman-KK)

#street photography#night#railway#perspective#tokyo#japan#2024#original photographers#artists on tumblr#kkworks#over50

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

The terms “suburbs” and “suburbanization” often bring to mind the period after the Second World War, defined by rows of bungalows on tree-lined streets. Another image of the suburbs are the more recent stucco McMansions in far-flung areas of the city with garages standing guard over sidewalk-less streets.

In fact, the process of suburbanization emerged far earlier in Canadian cities and was deeply tied to the emergence of the streetcar as a revolutionary form of public transpiration.

Up until the late 19th century, there were no effective means of mass public transit and most people’s main form of transportation was walking. The lack of transit set real limitations in terms of where people could live.

...

The period saw Winnipeg as the main industrial and wholesale base for western Canada. With three railways crossing the city and the grain exchange being moved from Toronto to Winnipeg in 1890, Winnipeg was considered the “Chicago of the North.”

In 1910, Winnipeg accounted for 50 per cent of all manufacturing in western Canada. A massive industrial working class was created in Winnipeg, and those workers needed to get to work somehow.

Yearly streetcar paid fairs increased from 3.5 million passengers in 1900 to 60 million in 1913. The areas of the city that gained the most new residents in this time were west and south Winnipeg.

Streetcars were not only the most effective option for public transport but also used as a tool for land speculation that drove the creation of new developments and suburbs.

In many cases, streetcar lines were built into less-developed areas to spur on development and used as a promotional tool to attract homebuyers.

Land and subdivisions that had basic municipal services, paved sidewalks, sewers and piped water, were still the most desirable to homebuyers and developers – but by 1900, streetcar service was a requirement."

- Scott Price, "The streetcar emerges," The Uniter. Volume 78, Number 06. October 19, 2023.

#winnipeg#streetcars#street railways#mass transit#public transportation#canadian history#land development#working class culture#suburbs

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Entrance to City Road Tube Station Islington seen here in 1915. Almost nothing can be seen of this station which was between Old Street and Angel on what is now the Northern Line. The station fell into disuse as long ago as 1922 because of a lack of footfall. In WW2 the station was converted into an air raid shelter but after the war all trace of this was removed as well as the platforms. The street level building remained intact until 1970, when it was largely demolished leaving a small part of the southern end of the building incorporating the ventilation tower. Access to the disused station is maintained today as a means of emergency egress.

#railway station#london history#london life#transport#street scene#social history#architecture#1800s#1900s

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexey Lermontov

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tokyo Sakura Tram

Minowabashi, Tokyo, Japan

#photographers on tumblr#railway#tram#architecture#tokyo#japan#street car#streets#street photography#trams#trains#tokyo sakura tram#original photographers#original photography#vertical#toden arakawa line#minowabashi#東京さくらトラム#都電荒川線

316 notes

·

View notes

Text

VIA Rail Station

#railway station#pacific central#vancouver#station street#local#photographers on tumblr#original phography

93 notes

·

View notes