#supply chains

Text

#brandon scott#francis scott key bridge collapse#baltimore mayor#racist attacks#diversity equity inclusion#wes moore#baltimore politics#political criticism#city leadership#baltimore community#urban challenges#racial discrimination#political backlash#community activism#baltimore bridge collapse#infrastructure disaster#francis scott key bridge#construction accident#rescue operations#salvage effort#port of baltimore#supply chains#federal government#reconstruction cost#insurance claims#liability

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

What comes after neoliberalism?

In his American Prospect editorial, “What Comes After Neoliberalism?”, Robert Kuttner declares “we’ve just about won the battle of ideas. Reality has been a helpful ally…Neoliberalism has been a splendid success for the top 1 percent, and an abject failure for everyone else”:

https://prospect.org/economy/2023-03-28-what-comes-after-neoliberalism/

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/28/imagine-a-horse/#perfectly-spherical-cows-of-uniform-density-on-a-frictionless-plane

Kuttner’s op-ed is a report on the Hewlett Foundation’s recent “New Common Sense” event, where Kuttner was relieved to learn that the idea that “the economy would thrive if government just got out of the way has been demolished by the events of the past three decades.”

We can call this neoliberalism, but another word for it is economism: the belief that politics are a messy, irrational business that should be sidelined in favor of a technocratic management by a certain kind of economist — the kind of economist who uses mathematical models to demonstrate the best way to do anything:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/27/economism/#what-would-i-do-if-i-were-a-horse

These are the economists whose process Ely Devons famously described thus: “If economists wished to study the horse, they wouldn’t go and look at horses. They’d sit in their studies and say to themselves, ‘What would I do if I were a horse?’”

Those economists — or, if you prefer, economismists — are still around, of course, pronouncing that the “new common sense” is nonsense, and they have the models to prove it. For example, if you’re cheering on the idea of “reshoring” key industries like semiconductors and solar panels, these economismists want you to know that you’ve been sadly misled:

https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/24/economy-trade-united-states-china-industry-manufacturing-supply-chains-biden/

Indeed, you’re “doomed to fail”:

https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/high-taxpayer-cost-saving-us-jobs-through-made-america

Why? Because onshoring is “inefficient.” Other countries, you see, have cheaper labor, weaker environmental controls, lower taxes, and the other necessities of “innovation,” and so onshored goods will be more expensive and thus worse.

Parts of this position are indeed inarguable. If you define “efficiency” as “lower prices,” then it doesn’t make sense to produce anything in America, or, indeed, any country where there are taxes, environmental regulations or labor protections. Greater efficiencies are to be had in places where children can be maimed in heavy machinery and the water and land poisoned for a millions years.

In economism, this line of reasoning is a cardinal sin — the sin of caring about distributional outcomes. According to economism, the most important factor isn’t how much of the pie you’re getting, but how big the pie is.

That’s the kind of reasoning that allows economismists to declare the entertainment industry of the past 40 years to be a success. We increased the individual property rights of creators by expanding copyright law so it lasts longer, covers more works, has higher statutory damages and requires less evidence to get a payout:

https://chokepointcapitalism.com/

At the same time, we weakened antitrust law and stripped away limits on abusive contractual clauses, which let (for example) three companies acquire 70% of all the sound recording copyrights in existence, whose duration is effectively infinite (the market for sound recordings older than 90 is immeasurably small).

This allowed the Big Three labels to force Spotify to take them on as co-owners, whereupon they demanded lower royalties for the artists in their catalog, to reduce Spotify’s costs and make it more valuable, which meant more billions when it IPOed:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/12/streaming-doesnt-pay/#stunt-publishing

Monopoly also means that all those expanded copyrights we gave to creators are immediately bargained away as a condition of passing through Big Content’s chokepoints — giving artists the right to control sampling is just a slightly delayed way of giving labels the right to control sampling, and charge artists for the samples they use:

https://doctorow.medium.com/united-we-stand-61e16ec707e2

(In the same way that giving creators the right to decide who can train a “Generative AI” with their work will simply transfer that right to the oligopolists who have the means, motive and opportunity to stop paying artists by training models on their output:)

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/09/ai-monkeys-paw/#bullied-schoolkids

After 40 years of deregulation, union busting, and consolidation, the entertainment industry as a whole is larger and more profitable than ever — and the share of those profits accruing to creative workers is smaller, both in real terms and proportionally, and it’s continuing to fall.

Economismists think that you’re stupid if you care about this, though. If you’re keeping score on “free markets” based on who gets how much money, or how much inequality they produce, you’re committing the sin of caring about “distributional effects.”

Smart economismists care about the size of the pie, not who gets which slice. Unsurprisingly, the greatest advocates for economism are the people to whom this philosophy allocates the biggest slices. It’s easy not to care about distributional effects when your slice of the pie is growing.

Economism is a philosophy grounded in “efficiency” — and in the philosophical sleight-of-hand that pretends that there is an objective metric called “efficiency” that everyone can agree with. If you disagree with economismists about their definition of “efficiency” then you’re doing “politics” and can be safely ignored.

The “efficiency” of economism is defined by very simple metrics, like whether prices are going down. If Walmart can force wage-cuts on its suppliers to bring you cheaper food, that’s “efficient.” It works well.

But it fails very, very badly. The high cost of low prices includes the political dislocation of downwardly mobile farmers and ag workers, which is a classic precursor to fascist uprisings. More prosaically, if your wages fall faster than prices, then you are experiencing a net price increase.

The failure modes of this efficiency are endless, and we keep smashing into them in ghastly and brutal ways, which goes a long way to explaining the “new commons sense” Kuttner mentions (“Reality has been a helpful ally.”) For example, offshoring high-tech manufacturing to distant lands works well, but fails in the face of covid lockdowns:

https://locusmag.com/2020/07/cory-doctorow-full-employment/

Allowing all the world’s shipping to be gathered into the hands of three cartels is “efficient” right up to the point where they self-regulate their way into “efficient” ships that get stuck in the Suez canal:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/03/29/efficient-markets-hypothesis/#too-big-to-sail

It’s easy to improve efficiency if you don’t care about how a system fails. I can improve the fuel-efficiency of every airplane in the sky right now: just have them drop their landing gear. It’ll work brilliantly, but you don’t want to be around when it starts to fail, brother.

The most glaring failure of “efficiency” is the climate emergency, where the relative ease of extracting and burning hydrocarbons was pursued irrespective of the incredible costs this imposes on the world and our species. For years, economism’s position was that we shouldn’t worry about the fact that we were all trapped in a bus barreling full speed for a cliff, because technology would inevitably figure out how to build wings for the bus before we reached the cliff’s edge:

https://locusmag.com/2022/07/cory-doctorow-the-swerve/

Today, many economismists will grudgingly admit that putting wings on the bus isn’t quite a solved problem, but they still firmly reject the idea of directly regulating the bus, because a swerve might cause it to roll and someone (in the first class seats) might break a leg.

Instead, they insist that the problem is that markets “mispriced” carbon. But as Kuttner points out: “It wasn’t just impersonal markets that priced carbon wrong. It was politically powerful executives who further enriched themselves by blocking a green transition decades ago when climate risks and self-reinforcing negative externalities were already well known.”

If you do economics without doing politics, you’re just imagining a perfectly spherical cow on a frictionless plane — it’s a cute way to model things, but it’s got limited real-world applicability. Yes, politics are squishy and hard to model, but that doesn’t mean you can just incinerate them and do math on the dubious quantitative residue:

https://locusmag.com/2021/05/cory-doctorow-qualia/

As Kuttner writes, the problem of ignoring “distributional” questions in the fossil fuel market is how “financial executives who further enriched themselves by creating toxic securities [used] political allies in both parties to block salutary regulation.”

Deep down, economismists know that “neoliberalism is not about impersonal market forces. It’s about power.” That’s why they’re so invested in the idea that — as Margaret Thatcher endlessly repeated — “there is no alternative”:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/11/08/tina-v-tapas/#its-pronounced-tape-ass

Inevitabilism is a cheap rhetorical trick. “There is no alternative” is a demand disguised as a truth. It really means “Stop trying to think of an alternative.”

But the human race is blessed with a boundless imagination, one that can escape the prison of economism and its insistence that we only care about how things work and ignore how they fail. Today, the world is turning towards electrification, a project of unimaginable ambition and scale that, nevertheless, we are actively imagining.

As Robin Sloan put it, “Skeptics of solar feasibility pantomime a kind of technical realism, but I think the really technical people are like, oh, we’re going to rip out and replace the plumbing of human life on this planet? Right, I remember that from last time. Let’s gooo!”

https://www.robinsloan.com/newsletters/room-for-everybody/

Sloan is citing Deb Chachra, “Every place in the world has sun, wind, waves, flowing water, and warmth or coolness below ground, in some combination. Renewable energy sources are a step up, not a step down; instead of scarce, expensive, and polluting, they have the potential to be abundant, cheap, and globally distributed”:

https://tinyletter.com/metafoundry/letters/metafoundry-75-resilience-abundance-decentralization

The new common sense is, at core, a profound liberation of the imagination. It rejects the dogma that says that building public goods is a mystic art lost along with the secrets of the pyramids. We built national parks, Medicare, Medicaid, the public education system, public libraries — bold and ambitious national infrastructure programs.

We did that through democratically accountable, muscular states that weren’t afraid to act. These states understood that the more national capacity the state produced, the more things it could do, by directing that national capacity in times of great urgency. Self-sufficiency isn’t a mere fearful retreat from the world stage — it’s an insurance policy for an uncertain future.

Kuttner closes his editorial by asking what we call whatever we do next. “Post-neoliberalism” is pretty thin gruel. Personally, I like “pluralism” (but I’m biased).

Have you ever wanted to say thank you for these posts? Here's how you can do that: I'm kickstarting the audiobook for my next novel, a post-cyberpunk anti-finance finance thriller about Silicon Valley scams called Red Team Blues. Amazon's Audible refuses to carry my audiobooks because they're DRM free, but crowdfunding makes them possible.

http://redteamblues.com

[Image ID: Air Force One in flight; dropping away from it are a parachute and its landing gear.]

#pluralistic#crypto forks#economism#imagine a horse#perfectly spherical cows of uniform density on a frictionless plane#neoliberialism#inevitabilism#tina#free markets#distributional outcomes#there is no alternative#supply chains#graceful failure modes#law and political economy#apologetics#robert kuttner#the american prospect

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of course, it’s true that China accounts for more than half the world’s coal power — and is the world’s largest carbon-dioxide emitter. It’s also true that U.S. CO2 emissions have declined over the years, while China’s are now nearly twice the U.S.’s. And it’s also true that, as David Holt, president of the fossil-fueled Consumer Energy Alliance recently wrote, China is home to 23 of the “top 25” cities “responsible for 52 percent of the planet’s urban greenhouse gas emissions.” But that fact doesn’t magically vacate the U.S.’s responsibility for its own emissions.

Nor does it obviate the fact that, as Mongabay pointed out, “historically, the U.S. is responsible for a quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas output.” That’s despite being home to less than 5 percent of the world’s population. In fact, the study Holt cited on emissions in China also noted that China’s per capita output is still below “wealthier countries” like the U.S. and those in Europe.

[...]

Simply put, corporate America has fueled much of China’s carbon-belching industrial behemoth. U.S. corporations and investors exploited China’s relatively few environmental regulations, along with its vast supply of cheap labor, in an effort to minimize the cost of doing their business. U.S. corporations were able to relocate their manufacturing to China thanks in no small part to All-American economic policies emphasizing maximum profit and avoidance of regulations. Those policies, in turn, globalized the supply chains that made those profitable regulatory dodges possible.

[...]

...there’s a direct correlation between the rise of China as Corporate America’s offshore factory and China’s rise as the world’s leading fossil fuel-burning, carbon-emitting nation. You can see the “lift-off” point after it was granted [Permanent Normal Trading Relations] in 2001.

Currently, U.S. corporations and consumers directly drive at least one-fifth of China’s industrial carbon output. But that doesn’t fully account for the indirect, carbon-polluting oil-driven supply chain that takes oil and gas out of the ground in the Middle East and ships it to China, where it is burned for fuel and manufactured into hydrocarbon-based plastic products. Those products get shipped overseas to ports on the West and East Coasts of the United States before being trucked to retail outlets and home shoppers around the country, with CO2 produced every step of the way. Even worse, China’s mass production of hydrocarbon-based plastic for the U.S. market helps sustain the global oil industry’s heavily subsidized business model.

China’s carbon production is also indirectly subsidized by the U.S. military, which is the de facto guarantor of the international oil economy and, specifically, of oil and gas shipments from U.S. partners in the Persian Gulf to China. The U.S. Navy’s Bahrain-based Fifth Fleet, among other military assets, ensures the free flow of hydrocarbons into China’s fossil-fueled factories. In 2020, according to World’s Top Exports, nearly “half (47.1 percent) of Chinese imported crude oil originated from nine Middle Eastern nations,” with U.S.-protected Saudi Arabia atop the list of China’s main oil providers. The U.S. is ninth on the list. In 2020, the U.S. and its staunch allies in the United Arab Emirates and oil-rich Norway were the only countries increasing oil exports to China’s carbon-generating industrial sector, while the rest saw declines.

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

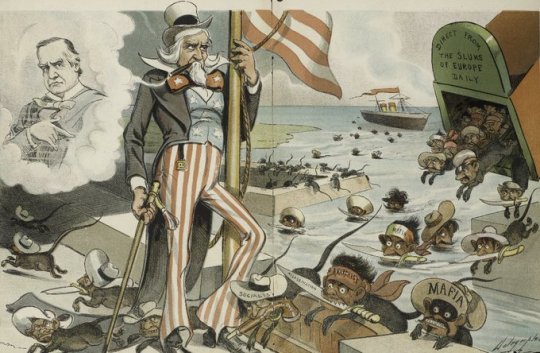

This political cartoon by Louis Dalrymple appeared in Judge magazine in 1903. It depicts European immigrants as rats. Nativism and anti-immigration have a long and sordid history in the United States.

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

March 28, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

MAR 29, 2024

Yesterday the National Economic Council called a meeting of the Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force, which the Biden-Harris administration launched in 2021, to discuss the impact of the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge and the partial closure of the Port of Baltimore on regional and national supply chains. The task force draws members from the White House and the departments of Transportation, Commerce, Agriculture, Defense, Labor, Health and Human Services, Energy, and Homeland Security. It is focused on coordinating efforts to divert ships to other ports and to minimize impacts to employers and workers, making sure, for example, that dock workers stay on payrolls.

Today, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg convened a meeting of port, labor, and industry partners—ocean carriers, truckers, local business owners, unions, railroads, and so on—to mitigate disruption from the bridge collapse. Representatives came from 40 organizations including American Roll-on Roll-off Carrier; the Georgia Ports Authority; the International Longshoremen’s Association, the International Organization of Masters, Mates and Pilots; John Deere; Maersk; Mercedes-Benz North America Operations; Seabulk Tankers; Under Armour; and the World Shipping Council.

Today the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration announced it would make $60 million available immediately to be used as a down payment toward initial costs. Already, though, some Republicans are balking at the idea of using new federal money to rebuild the bridge, saying that lawmakers should simply take the money that has been appropriated for things like electric vehicles, or wait until insurance money comes in from the shipping companies.

In 2007, when a bridge across the Mississippi River in Minneapolis suddenly collapsed, Congress passed funding to rebuild it in days and then-president George W. Bush signed the measure into law within a week of the accident.

In the past days, we have learned that the six maintenance workers killed when the bridge collapsed were all immigrants, natives of Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. Around 39% of the workforce in the construction industry around Baltimore and Washington, D.C., about 130,000 people, are immigrants, Scott Dance and María Luisa Paúl reported in the Washington Post yesterday.

Some of the men were undocumented, and all of them were family men who sent money back to their home countries, as well. From Honduras, the nephew of one of the men killed told the Associated Press, “The kind of work he did is what people born in the U.S. won’t do. People like him travel there with a dream. They don’t want to break anything or take anything.”

In the Philadelphia Inquirer today, journalist Will Bunch castigated the right-wing lawmakers and pundits who have whipped up native-born Americans over immigration, calling immigrants sex traffickers and fentanyl dealers, and even “animals.” Bunch illustrated that the reality of what was happening on the Francis Scott Key Bridge when it collapsed creates an opportunity to reframe the immigration debate in the United States.

Last month, Catherine Rampell of the Washington Post noted that immigration is a key reason that the United States experienced greater economic growth than any other nation in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. The surge of immigration that began in 2022 brought to the U.S. working-age people who, Director Phill Swagel of the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office wrote, are expected to make the U.S. gross domestic product about $7 trillion larger over the ten years from 2023 to 2034 than it would have been otherwise. Those workers will account for about $1 trillion dollars in revenues.

Curiously, while Republican leaders today are working to outdo each other in their harsh opposition to immigration, it was actually the leaders of the original Republican Party who recognized the power of immigrants to build the country and articulated an economic justification for increased immigration during the nation’s first major anti-immigrant period.

The United States had always been a nation of immigrants, but in the 1840s the failure of the potato crop in Ireland sent at least half a million Irish immigrants to the United States. As they moved into urban ports on the East Coast, especially in Massachusetts and New York, native-born Americans turned against them as competitors for jobs.

The 1850s saw a similar anti-immigrant fury in the new state of California. After the discovery of gold there in 1848, native-born Americans—the so-called Forty Niners—moved to the West Coast. They had no intention of sharing the riches they expected to find. The Indigenous people who lived there had no right to the land under which gold lay, native-born men thought; nor did the Mexicans whose government had sold the land to the U.S. in 1848; nor did the Chileans, who came with mining skills that made them powerful competitors. Above all, native-born Americans resented the Chinese miners who came to work in order to send money home to a land devastated by the first Opium War.

Democrats and the new anti-immigrant American Party (more popularly known as the “Know Nothings” because members claimed to know nothing about the party) turned against the new immigrants, seeing them as competition that would drive down wages. In the 1850s, Know Nothing officials in Massachusetts persecuted Catholics and deported Irish immigrants they believed were paupers. In California the state legislature placed a monthly tax on Mexican and Chinese miners, made unemployment a crime, took from Chinese men the right to testify in court, and finally tried to stop Chinese immigration altogether by taxing shipmasters $50 for each Chinese immigrant they brought.

When the Republicans organized in the 1850s, they saw society differently than the Democrats and the Know Nothings. They argued that society was not made up of a struggle over a limited economic pie, but rather that hardworking individuals would create more than they could consume, thus producing capital that would make the economy grow. The more people a nation had, the stronger it would be.

In 1860 the new party took a stand against the new laws that discriminated against immigrants. Immigrants’ rights should not be “abridged or impaired,” the delegates to its convention declared, adding that they were “in favor of giving a full and efficient protection to the rights of all classes of citizens, whether native or naturalized, both at home and abroad.”

Republicans’ support for immigration only increased during the Civil War. In contrast to the southern enslavers, they wanted to fill the land with people who supported freedom. As one poorly educated man wrote to his senator, “Protect Emegration and that will protect the Territories to Freedom.”

Republicans also wanted to bring as many workers to the country as possible to increase economic development. The war created a huge demand for agricultural products to feed the troops. At the same time, a terrible drought in Europe meant there was money to be made exporting grain. But the war was draining men to the battlefields of Stones River and Gettysburg and to the growing U.S. Navy, leaving farmers with fewer and fewer hands to work the land.

By 1864, Republicans were so strongly in favor of immigration that Congress passed “an Act to Encourage Immigration.” The law permitted immigrants to borrow against future homesteads to fund their voyage to the U.S., appropriated money to provide for impoverished immigrants upon their arrival, and, to undercut Democrats’ accusations that they were simply trying to find men to throw into the grinding war, guaranteed that no immigrant could be drafted until he announced his intention of becoming a citizen.

Support for immigration has waxed and waned repeatedly since then, but as recently as 1989, Republican president Ronald Reagan said: “We lead the world because, unique among nations, we draw our people—our strength—from every country and every corner of the world. And by doing so we continuously renew and enrich our nation…. Thanks to each wave of new arrivals to this land of opportunity, we're a nation forever young, forever bursting with energy and new ideas, and always on the cutting edge, always leading the world to the next frontier. This quality is vital to our future as a nation. If we ever closed the door to new Americans, our leadership in the world would soon be lost.”

The workers who died in the bridge collapse on Tuesday “were not ‘poisoning the blood of our country,’” Will Bunch wrote, quoting Trump; “they were replenishing it…. They may have been born all over the continent, but when these men plunged into our waters on Tuesday, they died as Americans.”

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#immigration#history#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#Know Nothings#supply chains#economic growth

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TTOA: Native Arrangement IV by Kai (Kari) Altmann aka Hitashya, spotted in Ras Al Khaima, UAE

http://karialtmann.com/teams/ttoa

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

While class conflict may have grown in the Americas due to free trade, In the East however with America and Europe having many of their industries and imports being based from countries like China, India, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, Western free trade has given rise to these Eastern countries to become superpowers like in the case of China and Russia and Regional powers who also have major effects on the world economy nevertheless like Saudi Arabia. This of course is more in line with Oswald Spengler view of the destruction of Western capitalism than it is with Karl Marx. In 'Man and Technics,' Spengler warned that western technological capitalism was not only destroying everything that was natural, but was also moving many industries to East Asian countries for profit and that this would eventually give these East Asian countries the economic power to rival the West. This is especially true for China, which has the second largest economy in world partially due to Chinese state intervention and the outsourcing of western industries to China.

The importance of China and other eastern countries economies can be seen from the last two years alone. With China shutting down for Covid, which caused mass trade distributions and shortages in America and the world. To Russia, oil and natural gas being sanctioned by western countries due to the war in Ukraine which has caused a shortage of fossil fuels and the price of energy to increase. Not to mention, made inflation worse for many western countries. All this was also accelerated when Saudi Arabia and OPEC announced that they would decrease oil production by 2 million barrels causing more problems for western economies.

Albino Squirrel, “The American Protectionist Economy of The Past and The Protectionist Economy of The Future” (November 8th 2022).

#Globalization#Trade#Protectionism#National Economics#Supply Chains#supply chain disruption#Geopolitics#Current State of Affairs#Heterodox Economics

1 note

·

View note

Text

Building resilient supply chains in West Africa: Strategies for reducing risk and increasing efficiency

0 notes

Text

#late capitalism#contemporary economy#income inequality#corporate power#shrinking middle class#economic absurdities#capitalist system#socio-economic critique#economic critique#wealth disparity#capitalist society#economic system#baltimore bridge collapse#infrastructure disaster#francis scott key bridge#construction accident#rescue operations#salvage effort#port of baltimore#supply chains#federal government#reconstruction cost#insurance claims#liability

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vision Zero Fund forum 2024: Occupational safety and health in supply chains: Challenges and opportunities.

Since the establishment of the Vision Zero Fund (VZF) in 2015, much progress has been made in relation to improving workers' occupational safety and health (OSH). However, despite these successes and achievements, much work still needs to be done.

Vision Zero Fund forum 2024: Occupational safety and health in supply chains: Challenges and opportunities

#occupational health#occupational injury#safety and health at work#Vision Zero Fund (VZF)#supply chains#global supply chains#panel discussion

0 notes

Text

Mexico slams the USA's new beef labeling rule, calling it discriminatory. A potential trade war looms over North American supply chains.

0 notes

Text

#mitsde#distance learning#distance courses#distance mba#distance learning mba#pgdm#pgdm course#pgdm colleges#distancelearning#distance education#supply chain management#supply and demand#sustainability#supply chains#supplychainmanagement#global logistics and supply chain#pgdm in logistics and supply chain management#global logistics#logistics#applynow

0 notes

Text

Five Megatrends Influencing Supply Chain Risk And Resilience With Bindiya Vakil CEO Resilinc

In the rapidly evolving world of global commerce, the supply chain is the backbone of every successful business. It’s the conduit through which goods flow, orders are fulfilled, and customer satisfaction is secured. However, this complex system is not immune to disruption, be it from geopolitical shifts, climate change, or technological challenges. In a recent episode of the Chain Reaction…

View On WordPress

#@buzzsprout#AI#Bindiya Vakil#CEO Resilinc#Chain Reaction Podcast Tony Hines#Climate Change#Resilience#Resilinc#Risk#Supply Chain Strategies#Supply Chains#Supply chian risk#Sustainability

0 notes

Text

The Erie Canal

Good roads, canals, and navigable rivers, by diminishing the expense of carriage, put the remote parts of the country more nearly upon a level with those in the neighbourhood of the town. They are upon that account the greatest of all improvements.

Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776

The zeitgeist of nationalism fostering the ascendancy of the Merchant Marine between the Tonnage and Lighthouse Acts from the selfsame vintage in 1789 crescendoed into the famous ‘Report on Manufactures’ two years later. This polemic propounded by Alexander Hamilton who was an early exponent for a mixed economy with some influence of statism upon free markets sought to remake America from an agrarian into an industrial society. As an iconoclast he espoused the belief that statecraft could incubate a Cambrian explosion if government elected to play a bigger custodian in the country’s development. With robust industries ascribed to tariffs and subsidies America might begin to disentangle itself from colonialism’s legacy in a bid to assume autonomy. Such policies of market interference were anathema to the orthodoxy of the day when economist Adam Smith had authored his iconic apologia for the invisible hand of laissez-faire capitalism in the ‘Wealth of Nations’ only fifteen years prior. At the same time the literati looked askance at all centralized power upon having just defeated the British monarchy under the banner of individual liberty. Nevertheless the Hamiltonian doctrine admonished that if not for an interventionist state infant industries would be deprived of growth in perpetuity.

Limited government simply emboldens more established incumbents to purloin what little marketshare might be used to nourish younger companies. Fatalism characterizes all possible outcomes thereafter since any manufacturing base would be stillborn if vulnerable firms were left to their own devices. A dirigiste variant of governance with a predilection for protective tariffs and federal subsidies by contrast could be a standalone buffer against the asymmetrical advantage held by foreign firms. Reprieve from such intense competition would be enough of fertile ground for fledgling industries to become self-sufficient. Hamilton’s thesis really did emblematize a clarion call for the country to transcend its primordial ways of husbandry by finding deliverance in a diversified economy. Therein the manacles of colonial subservience could be broken if firms were insulated long enough so they may scale up through the accumulation of capital and technology. This judicious use of policy was the ideal antidote against the capture of indigenous industries from the exploitation of foreign firms operating with impunity. Although the logic of this statecraft was a radical departure from the traditional precepts of free markets a whole conceptual edifice was eventually built around it with the advent of the Industrial Revolution.

The manifesto of the Report on Manufactures was manifestly the progenitor of the country’s early development. What coincided with this new regime eponymously dubbed the ‘American System’ that came into mainstream acceptance due to the maverick Henry Clay was a gamut of industrial policies whose stimulus saw factories abound. The monoculture of agriculture production incrementally took less precedence with manufacturing growing at a faster cadence ex post independence. A consensus soon emerged of how a strong central government might very well be the gateway to an America becoming a juggernaut of industrial strength. Likeminded thought leaders thus began to form a critical mass of opinion in favour of a more proactive posture in markets. On the eve of the Report on Manufactures the Patent Law of 1790 was equally amongst that same array of policies in the camp of statism protecting know-how from pirates who would otherwise sabotage growth. In this case the latitude of having a temporary monopoly over new self-made technologies for fourteen years was a boon to companies seeking profitability (Frederico 1936). Henceforth inventors boasted the right to profit from their creations as they were immune to imitations whilst America ratcheted up its industrialization in earnest.

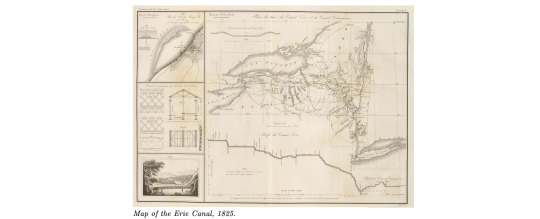

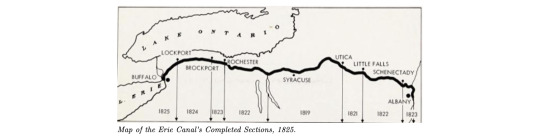

What the ‘American System’ inherited as the progeny of the Hamiltonian doctrine in the wake of the War of 1812 was a trinity of nationalist policies: (1) trade protectionism; (2) a national bank to stabilize the dollar in times of distress; and (3) industrial policies providing the wherewithal for public infrastructure. The third funded America’s first marvel of engineering linking the Hudson River with the Great Lakes so trade may seamlessly pass through the region. In lieu of the federal government it was the New York State Legislature which bore the onus of allocating money destined for this gambit. By the end vast tracts of land totalling 363 miles was excavated after nine years of laborious effort at a substantial cost of $7m or $166m after inflation that saw America’s rapid industrialization (Utter 2020). Such a mammoth piece of infrastructure cemented New York City’s station as America’s premier place of business by reconciling the hinterland with the Empire State. Raw commodities from the breadbasket of the Midwest came to be ensconced in the teeming markets across the Atlantic seaboard. Iron deposits sourced from this Elysium of minerals equally supplied the panoply of foundries and steel mills in the East. The economics of waterways would eclipse overland routes by orders of magnitude (Bowlus 2014).

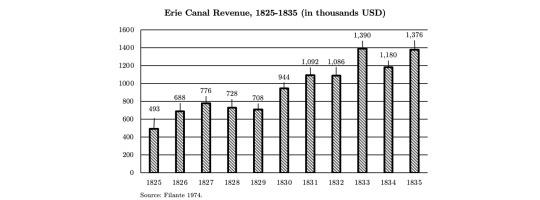

The completion of inland navigation via the Erie Canal between 1817 and 1825 from Buffalo to Albany with a total of 83 locks pared down shipping costs by a precipitous 90 percent. This vertiginous decline from $100 per ton of freight to a pittance of that at only $10 was a revolution for America’s supply chains as boats with a capacity of sixty tons superseded wagons drawn by quadrupeds whose pathetic limit was a single ton (North 1900: 123). Since waterways relegated overland shipping to an anachronism the cost difference between the two was so considerable that higher tolls could be added without being exploitive. In the first year alone did the Erie Canal amortize half a million dollars of its cost from the provenance of revenue generated from operations. Even with the stepwise growth of railroad expansion the throughput of tonnage by water appealed to merchants much more than that of locomotives despite the latter’s speed (Filante 1974). Far from being a flight of fiscal folly this investment in infrastructure ignited a mania for economic activity from the American interior to the bay of New York City. Where once eye-watering freight rates prohibited industrialization now the calculus had shifted to encourage the scale economies of production. Cheap transportation was in vogue.

0 notes