#tenducci

Text

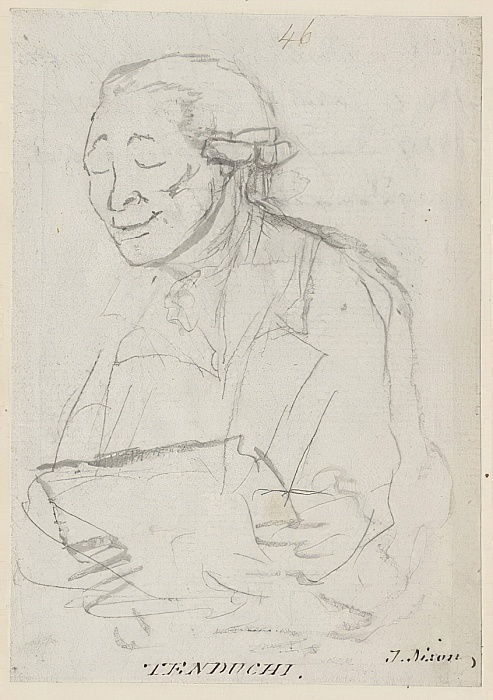

Giusto Tenducci, a famous castrato c. 1785 by John Nixon

Note: he was one of the very few castrati to go against the rules of the Catholic Church by marrying.

#Tenducci#its my first time seeing this drawing#another castrato with little portraits#castrato#castrati

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On September 5th 1750, the poet Robert Fergusson was born in the Canongate in Edinburgh.

He may have only lived for 24 years, the last of which was traumatic, but those short years not only inspired Scotland’s best-known bard Robert Burns and the writer Robert Louis Stevenson, it also paved the way for better treatment of people with mental health conditions thanks to the work of Doctor Andrew Duncan, a name many in Edinburgh will associate with the The Royal Edinburgh Hospital. The famous English writer Charles Dickens also visited Fergusson’s grave, mote on that later.

Although still relatively unknown, Fergusson was one of the most influential writers of his time despite dying at the tender age of 24, I wonder how many of you have maybe posed at his statue outside Canongate Kirkyard, but paid little attention to who he was?

Fergusson was brought up initially in Edinburgh but then moved to Dundee where he attended high school before being matriculated to the St Andrews University in 1765.

After the death of his father and completing his studies, the responsibility for supporting his mother fell upon Fergusson and he moved back to Edinburgh, taking up a post as a copyist. This caused some friction with his uncle as Fergusson had essentially rejected the excepted professions of the time such as lawyer or going into the church as a priest.

There is plenty of reason to believe that the young Fergusson had started developing his poetic sensibilities whilst at St Andrews, including beginning work on a play about Scottish brave-heart William Wallace. Moving to Edinburgh allowed Fergusson to get to known the writers and other artistic talent in the city, and he mixed largely in bohemian circles, befriending William Woods who managed some of the theatres there.

At the time, he also became friends with opera singer Tenducci who was touring the country with his company. This was when Fergusson was asked to produce Scottish songs for the Edinburgh section of the tour and marked his first published work. Buoyed by his success he began to produce satirical and pastoral poems for the Weekly Review that was run by Walter Ruddiman.

His initial offerings were traditional poems but it wasn’t long before Fergusson began writing verses that were considered more ‘Scots’. In 1772 he published The Daft Days which drew a good deal of attention and from then on he would submit poems in both English and the Scots dialect. His popularity also grew and in 1773 a collection of his work was published by Ruddiman which sold well enough for Fergusson to earn some money from his artistic endeavours.

Fergusson wrote his most well-known work, Auld Reekie, about this time and was confident enough of success to arrange to publish it himself. It was intended to be part of a much longer poem and provides an engaging and masterful portrait of Edinburgh at the time.

Unfortunately, Fergusson also suffered from bouts of depression and, if any further work was done on the poem it was probably destroyed by him in one of his darker moments.

Fergusson became a member of the famous Cape Club that would regularly meet in a local hostelry in the city. Each member of the club had a name and characteristic attached to them and drawings from the time show Fergusson as ‘Mr Precentor’.

Towards the middle of 1773, despite his growing success and popularity, Fergusson’s work grew a little darker and included Poem to the Memory of John Cunningham where he wrote about his fears of suffering a similar fate and ending up in a mental institution or asylum.

At the end of 1774, Fergusson suffered from an injury to his head and, though details are sketchy, did indeed end up in the Edinburgh equivalent of Bedlam. Two weeks later he was dead, at the tender age of 24, and had been buried in an unmarked plot in the city cemetery.

Now that may have been the end to the story and our fine Edinburgh poet may well have disappeared into obscurity if it weren’t for Robert Burns arrived in Edinburgh in 1786, he made a pilgrimage to the Canongate kirkyard to pay his respects to the young man who had inspired his poetry and whose grave lay unmarked for 12 years since his death at the age of 24 in October 1774.

Had Robert Fergusson lived and written more than one slim volume of poems, Scotland might now have two national bards and celebrate Fergusson Night with a feast of his favourite seafood on September 5th, the date of the neglected poet’s birth in 1750.

Burns himself acknowledged it long ago, when he paid for the headstone that now marks Fergusson’s grave and composed a heartfelt inscription:

No sculptur’d marble here, nor pompus lay,

No story’d urn nor animated bust;

This simple stone directs pale Scotia’s way

To pour her sorrows o'er her poet’s dust.

When Charles Dickens went to see Robert Ferguson’s grave It was dusk, he saw another grave stone and Ebenezer Scrogge Because it was dark, he thought his grave stone had mean man written on it But it read Meal man, meaning grain merchant, , , he thought how could a man be so mean, that they’d write it on his grave, the rest is history.

I touched upon Dr Andrew Duncan earlier he was Fergusson's doctor, and was moved by the poet's death, and he resolved to set up a hospital in the city which would look after the mentally ill with greater dignity and respect. Duncan launched a fundraising appeal in 1792, and eventually, in 1806, Parliament granted £2000 from estates forfeited during the Jacobite rebellion in 1745.

The money was used to buy a large house in Morningside with four acres of land, and the architect Robert Reid was commissioned to design a new building, which came to be called the East House.

Originally called the Edinburgh Lunatic Asylum, the hospital opened in 1813, initially for patients whose families could afford to pay. The West House, designed by William Burn, opened in 1842, for poor patients, and taking over the care of the city's Bedlam inmates in 1844. The West House was demolished in 1896, but the Royal Edinburgh Hospital remains. It includes the Andrew Duncan Clinic, opened in 1965.

I posted a bit of his epic poem Auld Reikie last year so this year here is another of his famous works, The Daft-days, in which Auld Reikie takes a central role, it is the old nickname for Scotland's capital city. The Daft-Days is the old name given to the period from Christmas to Handsel Monday because it is given over to celebration, merriment and excess, with many people having licence to act in frivolous or daft (mad) ways. It is still the primary period of national celebration in Scotland

The Daft-Days.

Now mirk December’s dowie face

Glowrs owr the rigs wi sour grimace,

While, thro’ his minimum of space,

The bleer-ey’d sun,

Wi blinkin light and stealing pace,

His race doth run.

From naked groves nae birdie sings,

To shepherd’s pipe nae hillock rings,

The breeze nae od’rous flavour brings

From Borean cave,

And dwyning nature droops her wings,

Wi visage grave.

Mankind but scanty pleasure glean

Frae snawy hill or barren plain,

Whan winter, ‘midst his nipping train,

Wi frozen spear,

Sends drift owr a’ his bleak domain,

And guides the weir.

Auld Reikie! thou’rt the canty hole,

A bield for many caldrife soul,

Wha snugly at thine ingle loll,

Baith warm and couth,

While round they gar the bicker roll

To weet their mouth.

When merry Yule-day comes, I trou,

You’ll scantlins find a hungry mou;

Sma are our cares, our stamacks fou

O’ gusty gear,

And kickshaws, strangers to our view,

Sin fairn-year.

Ye browster wives, now busk ye braw,

And fling your sorrows far awa;

Then come and gie’s the tither blaw

Of reaming ale,

Mair precious than the well of Spa,

Our hearts to heal.

Then, tho’ at odds wi a’ the warl’,

Amang oursels we’ll never quarrel;

Tho’ Discord gie a canker’d snarl

To spoil our glee,

As lang’s there’s pith into the barrel

We’ll drink and ‘gree.

Fidlers, your pins in temper fix,

And roset weel your fiddle-sticks;

But banish vile Italian tricks

Frae out your quorum,

Not fortes wi pianos mix –

Gie’s Tulloch Gorum.

For nought can cheer the heart sae weel

As can a canty Highland reel;

It even vivifies the heel

To skip and dance:

Lifeless is he wha canna feel

Its influence.

Let mirth abound, let social cheer

Invest the dawning of the year;

Let blithesome innocence appear

To crown our joy;

Nor envy wi sarcastic sneer

Our bliss destroy.

And thou, great god of Aqua Vitae!

Wha sways the empire of this city,

When fou we’re sometimes capernoity,

Be thou prepar’d

To hedge us frae that black banditti,

The City Guard.

More on Fergusson and some of his poetry here https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poet/robert-fergusson/

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thomas Gainsborough, Portrait de Giustu Ferdinando Tenducci tenant une partition, 1773-1775

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The brief history of Castrati - part two (part one)

From about 1680 the expectation, eventually the rule, was that the leading male part in a serious opera (primo uomo) should be sung by a castrato; there might be a less important secondo uomo part, also for a castrato, with tenors singing the parts of kings and old men. This was also the period when Italian opera came to be given fairly regularly both in Italy and in those parts of Europe under Italian musical influence - in the German-speaking countries and the Iberian peninsula, from about 1710 in London, from the 1730s in Sankt Petersburg. The best castratos therefore became international stars, welcomed and highly paid in all the leading courts and capital cities, with the notable exception of Paris (where, after Cardinal Mazarin’s attempts at importation in the mid-17th century, they were not allowed to appear in opera; some leading castratos gave concerts when they were passing through, and some much more modest ones remained on the king’s musical establishment as church singers until the Revolution).

The reasons for this new dominance of the castrato voice are interrelated. Italian composers of the period 1680 - 1720 began to write operas calling for more technically demanding coloratura singing; the range expected of leading singers widened, and the tessitura generally rose, as it was to go on doing (for both men and women) through most of the 18th century. Virtuoso castratos were now available in numbers in the service of princes who promoted frequent opera seasons: Giovanni Francesco Grossi (”Siface”) and Francesco Antonio Mamiliano Pistocchi were only the most prominent among a new group of star singers. It was still possible at this time for a famous castrato not to sing in opera at all, like Giovanni Battista Merola, active in Naples in the late 17th century, or, like Matteo Sassano (”Matteuccio”), whose career lasted from 1684 to 1711, to do so only occasionally. But from then on a famous castrato was in the first place an opera singer. Church choirs had increasingly to grant their best castratos leave to sing in opera.

Castratos occasionally appeared in comic opera but (outside Rome) normal voices were there the rule. In the newly refined genre of serious opera, on the other hand, the castrato voice with its special brilliance appears to have struck contemporaries as the right medium to convey nobility and heroism. Objections, when they came, were to the incongruity of castratos in general - or, on moral grounds, to their singing of womens parts - rather than to their appearance as heroes or lovers.

#source: the new grove dictionary of music and musicians#the brief history of castrati#castrato#castrati#18 century#baroque#history#history of music#opera#opera seria#charles joseph flipart#carlo scalzi#anton raphael mengs#domenico annibali#adamo solzi#thomas gainsborough#giusto ferdinando tenducci

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In Game:

Anne-Josèphe Théroigne de Méricourt, born Anne-Josèphe Terwagne, was a Belgian singer, orator and organizer active in Paris at the time of the French Revolution. During this tumultuous period, she became known as a defender of the poor and a fierce advocate for women's rights.

When hunger and despair pushed market women to march on Versailles on October 5th, 1789, Théroigne and one of her allies joined them in their protest. As Théroigne's reputation preceded her, several men attempted to deter her on her way to the city gates, though the Assassins ensured she and the march could proceed peacefully all the way to Versailles. As a result, king Louis XVI was forced to move to Paris along with his family and the National Assembly. Théroigne herself regularly attended the Assembly and thus moved from Versailles to Paris as well.

In the summer of 1792, Théroigne uncovered a conspiracy orchestrated by Templars that intended to sow chaos by starving Paris' citizens, turning them against each other. Tracing the group's activities for over a month, she was led to Flavigny, a woman who had assumed the guise of a couturiere to carry out her operations. Théroigne presented her findings to the National Assembly, but they did not believe her, forcing the revolutionary to take action herself.

Set on eliminating Flavigny's agents, Théroigne traveled to an address in the Hôtel-de-ville district that she had determined, but not before leaving a message for the Assassins, of whose presence she was also aware. Entering the building, she ended up being outnumbered, but was saved by the timely appearance of the Assassins. Together, they eliminated Flavigny's men and secured the stolen food, following which Théroigne told the Assassins of Flavigny's location, trusting them to take the Templar out.

Later, Théroigne found out about a gunsmith designing weapons for the Templars. In response, she asked the Assassin Arno Dorian, who had previously aided her, to kill the gunsmith and retrieve the blueprints. In this way, her own Parisian militia would be able to manufacture more advanced weaponry for themselves. Desiring to establish an army of women, Théroigne would call on Arno once more in 1793, asking him to distribute recruitment handbills at various brothels.

In Real Life:

Théroigne de Méricourt was born Anne-Josèphe Terwagne on August 13th, 1762 near Liège to Pierre Terwagne and Anne-Elisabeth Lahaye. Her mother died when she was five following the birth of one of her brothers, so Anne-Josèphe was sent to live with an aunt, who didn't really want her. First, she sent the little girl to a convent, but later, perhaps to save money, she changed her mind and brought her back to live with her. But rather than giving her a loving home, Anne-Josèphe was treated like a maid.

When her father remarried, he welcome her back home. His new wife didn't. Too busy taking care of her own children, she didn't care much for Anne-Josèphe. So, desperate for affection and a real home, she went to live with her maternal grandparents. But things didn't work out there either. As a last resort, she returned to her aunt. Needless to say, the arrangement was a disaster. Anne-Josèphe then decided to face the world on her own, and took any job she could to support herself.

Eventually, she was hired by a certain Madame Colbert as her companion. Madame Colbert taught her to read, write, play the piano, and sing. Anne-Josèphe now dreamed of becoming a singer.

However, in 1782 she met an English officer. He took her off to England with promises of marriage that he had no intention of keeping. During this time, she was also kept by the old and unpleasant marquis de Persan, who showered her with expensive gifts and money (although she insisted she had evaded his advances). Her reputation in tatters and any hope of a respectable life gone, Anne-Josèphe become a courtesan and called herself Mlle Campinado. Her affair with the Englishman continued and resulted in a child who died, probably to the relief of his father who had refused to acknowledged her, of smallpox.

(Image source)

After a brief affair with an Italian tenor, she fell for the castrato Tenducci and, in 1788, followed him to Genoa, hoping to start a musical career there, but she only gave a few concerts. After a year, she returned to Paris, alone, disappointed, and hurt. All her dreams, both professional and romantic, were shattered. Her hopes vanished. Or so she thought until she set foot in the city. Paris was on the verge of revolution. It was an exciting time that seemed to promise her a better, more just, world, and the opportunity to take control of her destiny and rescue her from the life of unhappiness and abuse she had so far known.

That summer, Anne-Josèphe transformed herself. She ditched her gowns in favour of a white riding habit called amazone, and a round-brimmed hat, an eccentric outfit that made her stand out from the crowd. She wanted to "play the role of a man’, she later explained, because I had always been extremely humiliated by the servitude and prejudices, under which the pride of men holds my oppressed sex’". She also gave up her job as a courtesan, and pawned her jewels to support herself.

After the storming of the Bastille, she became involved in revolutionary activities. She attended the meetings of the National Assembly every day. She was the first to arrive and the last to leave, and met many influential figures of the Revolution, such as Pétion, the Abbé Sieyès, and Desmoulins. Anne-Josèphe played a big role too. She sometimes spoke at the Cordeliers Club, founded her own club, and ran her own saloon. Soon, she was a celebrity. It's at this time that she became to be known as Théroigne de Méricourt.

(Image source)

Although Théroigne believed in the ideals of the Revolution, it soon became clear that most of its supporters were only interested in the rights of men, not of women. The press, scared of emancipated women, started portraying her as a whore, heaping all sorts of insults, accusations, and obscenities at her. In disgust, in the summer of 1790, Théroigne left Paris and returned to Liège.

If she hoped for some peace and quiet, she was bitterly disappointed. Liège was then under the control of the Austrian Empire, not a safe place for such a prominent and famous figure of the Revolution. She was kidnapped by mercenaries and taken to Austria. The journey lasted 10 days and was harrowing. The three French emigrés insulted, harassed, and even tried, luckily unsuccessfully, to rape her.

Once in Austria, Théroigne was interrogated, over the course of a month, by François de Blanc. Hoping to discover important information about the French Revolutionaries, de Blanc, who believed all the nasty rumours about her prisoner, spent many hours talking to her and examining the papers that were found on her when she was caught. But he soon realised she knew nothing important. More surprisingly, he began to like her. Worried about her health - Théroigne suffered from depression and splitting headaches, coughed up blood and had trouble sleeping - he helped secure her release.

At the beginning of 1792, Théroigne was back in Paris. She now supported Brissot, a Girondin, against Robespierre, and gave many an inflammatory speeches in the Jacobin Club in which she called for the liberation of women from oppression. But this time, she didn't just fight with words. She recruited an army of female warriors, and took part in the storming of the Tuileries on 10th August. It is said that she wounded a royalist journalist who had insulted her in the press. He was then killed by the mob.

But she didn't support the September Massacres, believing all this unnecessary violence was hurting the cause of the Revolution. She wanted it to stop, but it didn't. Things got worse for Théroigne. In May 1793, a bunch of Jacobin women who hated the supporters of Brissot and the Girondin, attacked Théroigne in the gardens of the Tuileries. They stripped her naked and flogged her publicly. Only the intervention of Marat saved her.

(Image source)

Théroigne's mental health had always been fragile. Now, she descended into madness. In the spring of 1794, she was arrested. She became obsessed with Saint-Just, thinking of him as her saviour, but he did nothing to help her. She was eventually released from prison after the fall of Robespierre, but never recovered her sanity.

That year, she was officially declared insane. She spent the rest of her life in various asylums, and was ultimately sent to La Salpêtrière Hospital, where she lived for twenty years. All she spoke about was the Revolution. She still clang to her revolutionary ideals, even though everyone else had abandoned them. Théroigne died, following a short illness, on June 9th, 1817.

Sources:

http://www.amazingwomeninhistory.com/theroigne-de-mericourt/

http://cultureandstuff.com/2012/02/08/theroigne-de-mericourt-the-fatal-beauty-of-the-revolution-part-one/

http://historyandotherthoughts.blogspot.com/2015/05/madness-and-revolution-sad-life-of.html

http://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/theroigne-de-mericourt-anne-josephe-1762-1817

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) The opera singer Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci c.1777

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Talk to me if you are interested in:

Napoleon and Napoleon II

Rousseau

Charles II of England and his sons

Louis XIII/XVI/XV/XVI (yesss ALL of them)

Philippe I Duc d'Orleans

Marquis de Sade

Peter the Great

Louis Ferdinand, Dauphin

Lord Byron

Literally any of the castrati though my fav are Farinelli, Caffarelli, Matteuccio, Pacchierotti, Tenducci and Guadagni

Casanova (his memoirs are awesome)

John Wilmot (the naughtiest Earl of Rochester)

The Rhine princes (Charles Louis, Rupert, Edward, Maurice)

Louis Auguste (duke of Maine)

Henry Benedict Stuart

Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester

Louis Jean Marie de Bourbon, duc de Penthièvre

Charles Townshend, 2nd Viscount Townshend

François Louis, Prince of Conti

Louis Henri of Bourbon

Philippe, Duke of Vendôme

Louis, Duke of Orléans

Philippe, Chevalier de Lorraine

Carlo II Gonzaga Nevers

And thus concludes my subject-to-alteration list of dead men I'd like to discuss. Have a nice day/night! 🌈

#napoleon#rousseau#marquis de sade#louis xvi#louis xv#junot#louis xiv#philippe i duc d'orleans#louis xiii#christian vii#lord byron#peter the great#napoleon ii#Farinelli#Castrati#caffarelli#Pacchierotti#Guadagni#tenducci#casanova#giacomo casanova#charles ii of england#charles ii#matteuccio#john wilmot

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On September 5th 1750, the poet Robert Fergusson was born in the Canongate in Edinburgh.

Although still relatively unknown, Fergusson was one of the most influential writers of his time despite dying at the tender age of 24, I wonder how many of you have maybe posed at his statue outside Cangate Kirkyard, but paid little attention to who he was?

Fergusson was brought up initially in Edinburgh but then moved to Dundee where he attended high school before being matriculated to the St Andrews University in 1765.

After the death of his father and completing his studies, the responsibility for supporting his mother fell upon Fergusson and he moved back to Edinburgh, taking up a post as a copyist. This caused some friction with his uncle as Fergusson had essentially rejected the excepted professions of the time such as lawyer or going into the church as a priest.

There is plenty of reason to believe that the young Fergusson had started developing his poetic sensibilities whilst at St Andrews, including beginning work on a play about Scottish brave-heart William Wallace. Moving to Edinburgh allowed Fergusson to get to known the writers and other artistic talent in the city, and he mixed largely in bohemian circles, befriending William Woods who managed some of the theatres there.

At the time, he also became friends with opera singer Tenducci who was touring the country with his company. This was when Fergusson was asked to produce Scottish songs for the Edinburgh section of the tour and marked his first published work. Buoyed by his success he began to produce satirical and pastoral poems for the Weekly Review that was run by Walter Ruddiman.

His initial offerings were traditional poems but it wasn’t long before Fergusson began writing verses that were considered more ‘Scots’. In 1772 he published The Draft Days which drew a good deal of attention and from then on he would submit poems in both English and the Scots dialect. His popularity also grew and in 1773 a collection of his work was published by Ruddiman which sold well enough for Fergusson to earn some money from his artistic endeavours.

Fergusson wrote his most well-known work, Auld Reekie, about this time and was confident enough of success to arrange to publish it himself. It was intended to be part of a much longer poem and provides an engaging and masterful portrait of Edinburgh at the time.

Unfortunately, Fergusson also suffered from bouts of depression and, if any further work was done on the poem it was probably destroyed by him in one of his darker moments.

Fergusson became a member of the famous Cape Club that would regularly meet in a local hostelry in the city. Each member of the club had a name and characteristic attached to them and drawings from the time show Fergusson as ‘Mr Precentor’.

Towards the middle of 1773, despite his growing success and popularity, Fergusson’s work grew a little darker and included Poem to the Memory of John Cunningham where he wrote about his fears of suffering a similar fate and ending up in a mental institution or asylum.

At the end of 1774, Fergusson suffered from an injury to his head and, though details are sketchy, did indeed end up in the Edinburgh equivalent of Bedlam. Two weeks later he was dead, at the tender age of 24, and had been buried in an unmarked plot in the city cemetery.

Now that may have been the end to the story and our fine Edinburgh poet may well have disappeared into obscurity if it weren't for Robert Burns arrived in Edinburgh in 1786, he made a pilgrimage to the Canongate kirkyard to pay his respects to the young man who had inspired his poetry and whose grave lay unmarked for 12 years since his death at the age of 24 in October 1774.

Had Robert Fergusson lived and written more than one slim volume of poems, Scotland might now have two national bards and celebrate Fergusson Night with a feast of his favourite seafood on September 5th, the date of the neglected poet's birth in 1750.

Burns himself acknowledged it long ago, when he paid for the headstone that now marks Fergusson's grave and composed a heartfelt inscription:

No sculptur'd marble here, nor pompus lay,

No story'd urn nor animated bust;

This simple stone directs pale Scotia's way

To pour her sorrows o'er her poet's dust.

The pics are from one of my many visits to Canongate, I always try and pop in and pay my respects to the man.

From Auld Reekie.....

… Now morn, with bonny purpie-smiles,

Kisses the air-cock o’ St Giles;

Rakin their een, the servant lasses

Early begin their lies and clashes;

Ilk tells her friend o’ saddest distress,

That still she brooks frae scouling mistress;

And wi her joe in turnpike stair

She’d rather snuff the stinking air,

As be subjected to her tongue,

When justly censur’d in the wrong.

On stair wi tub, or pat in hand,

The barefoot housemaids loo to stand,

That antrin fock may ken how snell

Auld Reikie will at morning smell:

Then, with an inundation big as

The burn that ‘neath the Nore Loch Brig is,

They kindly shower Edina’s roses,

To quicken and regale our noses.

Now some for this, wi satire’s leesh,

Hae gien auld Edinburgh a creesh:

But without souring nocht is sweet;

The morning smells that hail our street

Prepare, and gently lead the way

To simmer canty, braw and gay;

Edina’s sons mair eithly share

Her spices and her dainties rare,

Than he that’s never yet been call’d

Aff frae his plaidie or his fauld.

Now stairhead critics, senseless fools,

Censure their aim, and pride their rules,

In Luckenbooths, wi glowring eye,

Their neighbour’s sma’est faults descry:

If ony loun should dander there,

Of aukward gate and foreign air,

They trace his steps, till they can tell

His pedigree as weel’s himsel …

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Opera seria - Valentine’s Day edition (with a help of De Castris )

#farinelli#Carlo Broschi#johann adolph hasse#Johann Adolf Hasse#charles burney#Senesino#francesco bernardi#giusto tenducci#giusto ferdinando tenducci#Metastasio#pietro metastasio#francesca cuzzoni#caffarelli#Gaetano Majorano#castrato#opera#opera seria#18 century#baroque#valentines#valentine's card#italian opera#history of music

24 notes

·

View notes