#that is a very very very common theme in beatles books

Text

reading goodreads reviews of beatles books is just like

person a: this had way too much information on the beatles, i’m just a casual fan, i didn’t need to know all of this

person b: i’ve read hundreds of books about the beatles, this had absolutely no new information

#kat reads dreaming the beatles#this post inspired by the dreaming the beatles reviews#where i just saw one of each back to back#the first one really baffles me#if you don't want more information on the beatles... why did you pick up a book about the beatles??#also in this particular case the second one said it was just bashing paul and praising john#and like look#that is a very very very common theme in beatles books#but i am a very large very sensitive paul stan#and i feel like this book has been pretty even handed#maybe a bit john-focused#but like#what beatles books aren't?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lewisohn vs. Cynthia Pt. 3 of 3

Part 1 // Part 2 // Other Sources

Quite by accident, this final section of citations from Tune In referencing Cynthia Lennon's memoirs have something of a theme. There are three citations of A Twist of Lennon (1978, aka Twist) and two to John (2005) to dissect here, and all but one have a commonality: the cited source is either altered or directly contradicted in Tune In.

The odd citation out is the one I'll deal with first, and then we'll dive into the citing-a-source-that-contradicts-what-you-wrote section under the cut. This first citation includes a classic Lewisohn Donut, in which he omits a section of the source quote without using an ellipsis to indicate it. When comparing Tune In to the source, this wasn't my biggest takeaway; what was far more glaring was the context Lewisohn had chosen to cut when adapting the anecdote for his book. Let's get into it.

John p.38 vs. Tune In 11-53

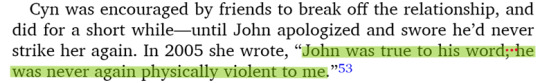

The topic here is John hitting Cyn, so there's a lot to unpack. We'll start with the usual citation comparison, and then we'll zoom out to see what Lewisohn does and doesn't include as context. Here's the source:

And here's Tune In:

Immediately, we see that Lewisohn has omitted a large part of the source without indication, and smushed two different sentences together into one. He should not do this, but, honestly, I was just glad Lewisohn covered John's history of domestic violence instead of glossing over it, so I wasn't too fussed...until I looked at the broader context in Tune In.

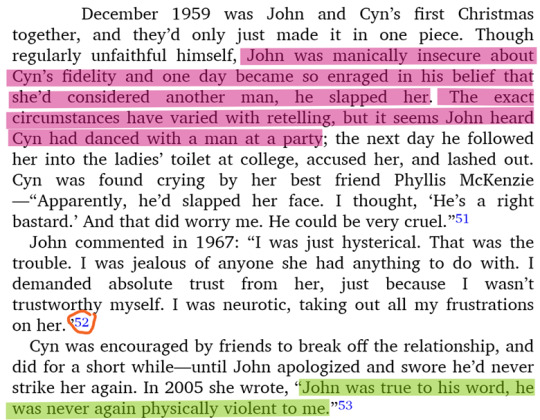

Lewisohn is skirting a hairsbreadth away from two pertinent stories. Here's the leadup to the quote used above, where Lewisohn describes the events that led John to slap Cyn:

There’s the quote we just looked at in green at the bottom, with some pertinent context highlighted in pink at the top—we’ll get to the world’s ugliest orange circle in a second.

John was insecure, so he hit Cyn when she danced with a man at a party. “The exact circumstances have varied with retelling,” Lewisohn tells us. Maybe that’s true. If you folks are aware of other versions of this story, please let me know—they may well be floating around! Here’s how Cyn describes it in John (p.37):

Two notable details here that didn't make it into Tune In: Cyn's head being knocked into pipes when John hit her, and the identity of the man she was dancing with: Stuart Sutcliffe.

Even if the details are different in other accounts, it is absolutely WILD to me that Lewisohn wouldn't mention that the cause for John's jealousy, according to Cyn's account, was Stuart. Even if he can't be 100% certain, would it not be worth mentioning that Cyn herself says Stuart was the man she was dancing with when John became incensed?

John’s relationship with Stuart was hugely important and influential in this period of John’s life. Lewisohn doesn't have to state it as fact, but I'm gobsmacked he wouldn't mention the strong possibility that John was enraged by Cyn dancing with his best friend. For someone as jealous and insecure as nineteen-year-old John Lennon, would that not have some lasting effects on his feelings towards Stu? Given how central the John-Stuart relationship is in Tune In, I don't know why Lewisohn wouldn't at least take a sentence or two to explore this possibility and the repercussions it might have had on their dynamic. Maybe this influenced John bullying Stu, or the purported attack on Stu described by Pauline Sutcliffe? Is none of this worth mentioning?

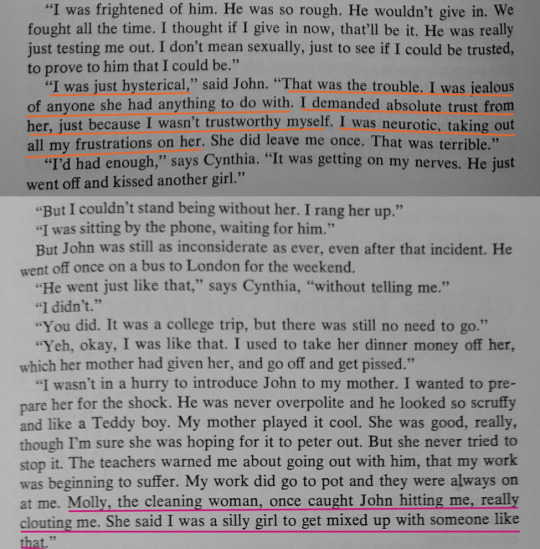

Now, the ugly orange circle. That citation refers to a passage in Hunter Davies' The Beatles (1968) where John and Cyn discuss his violent behavior. Here's some of that section from Davies (1968) p.52-3.

The quote Lewisohn uses is underlined with orange. If you read down to the pink-underlined passage, you'll see an account of John's violence towards Cynthia.

This is a very different account than the one we see in John or Tune In. This incident is distinct enough that I doubt it’s a retelling of the jealousy-induced slap described in Tune In, so there’s a inconsistency here: either the abuse in Hunter Davies’ work didn’t happen, or Cyn’s assertion that the art school slap was the single time John hit her isn’t entirely true.

I’m not trying to attack Cyn’s credibility or honesty in recounting her abuse, but I lean towards her downplaying events in her 2005 memoir. This might be a conscious choice—her ex-husband had since been martyred, and perhaps she didn’t want to tarnish his memory, or dredge up unwanted controversy that might affect her son—or a reflection of the amount of time that had passed, nearly 40 years since she and John got divorced. I don’t see a reason to disbelieve the story in Hunter Davies—John read the manuscript and had to sign off on it, so he could have had the story removed.

Lewisohn is certainly aware of this passage. In addition to the “I was just hysterical bit,” he cites the paragraph directly after Cyn’s account of John hitting her elsewhere in Tune In (see citation 10-10). I’m sure Lewisohn has his reasons for favoring the account from John, but I worry those reasons stem from trying to make John look as good as possible, not from trying to portray the most historically accurate version of events.

Twist p.80-82 vs. Tune In 31-12

(p.81 and p.82 pictured below)

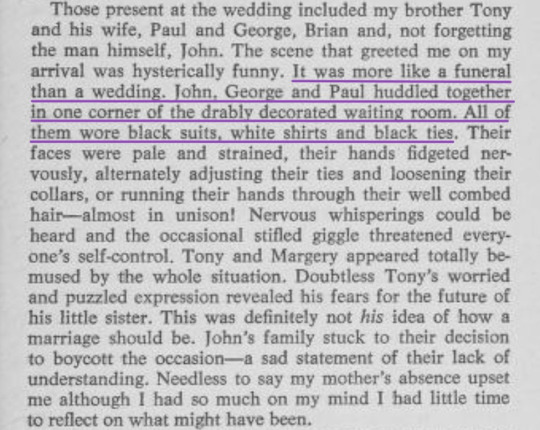

Onto the wedding of John and Cyn. There are two issues here.

First, the witnesses. Cyn gives her brother and sister-in-law as witnesses; Lewisohn gives Paul and Cyn’s sister-in-law as witnesses. I would not be at all surprised if Lewisohn has the facts straight here—Cyn actually gives the wrong year for her wedding on p.80 of Twist—but Lewisohn only gives Cyn’s memoir as a source for “[d]etails of the wedding.” Don’t cite something with a source that contradicts it.

The second bit I’d like to discuss is the description of John et al. in the waiting room before the wedding, highlighted/underlined in purple. This isn’t straight CTRL+C/CTRL-V plagiarism, but Lewisohn leaned heavily on Cyn’s phrasing and word choice here, switching around a few clauses and molding two sections into one. He’s changed this passage less than many of the passages he actually quotes, so I’m not sure why he didn’t put this one in quotes as well.

Twist p.84-87 vs. Tune In 33-35

This passage mostly lines up with the account in Twist, but the highlighted section stuck out to me: Cyn never mentions Dot living in the same building as her at this point. By Cyn’s account, after Paul broke up with Dot, Dot moved out of the bedsit where she and Cyn were neighbors, and the two barely saw each other. Here’s Cyn on p.77 of Twist:

Cyn also doesn’t mention Dot’s residency in the basement flat in John (2005)—but it seems she got the story wrong. On the It’s Only Love webpage (see Lewisohn vs. Cynthia Part 2 for some discussion about this source), there’s a quote from Dot about living in the flat beneath Cyn and John’s. In Bob Spitz’s The Beatles: The Biography (2005), he also says that Dot lived in the basement flat based on an interview he conducted with her. He even says that John helped Dot with rent! (Spitz 2005 p.357)

Don’t take this as an endorsement of Spitz’s version of events—I’m not going to write several pedantic tumblr posts criticizing Mark Lewisohn only to uphold Bob Spitz as a paragon of truth! But Cyn is fallible, and there are at least two sources out there that contradict her version of events. The problem here is that Lewisohn only cites Twist for his passage about the Falkner Street flat. You can’t credit information to a source that directly contradicts that information.

Hmmm, there’s a word for using information from a source without proper attribution, but I can’t quite put my finger on it. I think it starts with ‘P’…

Twist p.87 vs. Tune In 33-37

Lewisohn uses Twist as his source for the section of Tune In where John and Cyn move to Mendips. The difference lies in how that move came about. Cyn says that she encouraged John to visit Mimi since she hated to see family members fall out, then credits Mimi as proposing they move in when she hears about their current living situation. In Lewisohn’s version, John makes the request.

We’ve established that Cyn got some facts wrong in Twist (though not more than one might expect in a Beatles autobiography), so she might have things mixed up here. I know I’m a broken record at this point, but Lewisohn needs to cite his source if he has contradictory information here.

In this case, I think Cyn probably has things right. If you read her memoirs, it is clear that Cyn does not like Mimi, and she doesn’t hide this. I don’t think she would give Mimi credit for a generous act like this if it didn’t happen that way—but that’s just my sense of things, and rather beside the point.

John p.29-30 vs. Tune In 11-21

A minor change, but Cyn’s account has Mimi instigating the fight with Lil only joining when provoked, while Lewisohn draws no distinction between the roles the women played in the argument.

Thank you for reading! Next up...maybe All You Need Is Ears?

Sources:

Davies H. 1968. 2009 Edition. The Beatles. New York (NY): W.W. Norton & Company. 408p.

It's Only Love [Internet]. c2005? Dot Rhone. [cited 2024 Feb 2]. Available from: https://sentstarr.tripod.com/beatgirls/rhone.html

Lennon C. 1978. A Twist of Lennon. New York (NY): Avon Books. 190p.

Lennon C. 2005. 1st American Edition. John. New York (NY): Crown Publishers. 294p.

Spitz B. 2005. The Beatles: The Biography. New York (NY): Little, Brown and Company. 984p. [ebook]

#mark lewisohn#tune in#the beatles#john lennon#cynthia lennon#stuart sutcliffe#a twist of lennon#john (2005)#lewi-sins

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Many Mystery Tours of Winnie the Pooh

What do a Disney animated movie about a stuffed bear and a Beatles album have in common?

In some articles I wrote back in my WordPress days concerning the Disney "Animated Classics Canon", I talked about how The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh - released theatrically on March 11, 1977, was more of a clipshow than it was a fully-fledged Disney animated feature.

Now, the bonus features on various home media releases of this 1977 compilation film have often insisted the opposite. Disney seems to want your average consumer and us semi-historians to know that the story goes: Walt Disney was unsure about American audiences' familiarity with A. A. Milne's bedtime stories and the stuffed animal characters within. Instead of making a feature film as planned during the early 1960s, Walt planned to make three separate shorts to get audiences acquainted with those characters... and then string those three cartoon featurettes together into a 70-or-so-minute movie later down the line...

This seems to be a well-backed up history, too. After all, the autobiography of brothers Robert and Richard Sherman, known for their many contributions to the Disney songbook including the songs for these classic Winnie the Pooh adaptations, states pretty much the exact same thing. This strategy was not dissimilar to the studio's piecing-together of the Davy Crockett episodes of Disney's anthology series (then known as Disneyland, in promoting the upcoming theme park of the same name), which spawned the 1955 theatrical release Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier and its 1956 follow-up Davy Crockett and the River Pirates... But I feel this is untrue, and has been shown to be so...

Familiarity with British characters was never a problem for Walt and his crew before, or characters from European stories in general. Mary Poppins didn't need a couple of shorts, or some episodes of a TV show to familiarize audiences with the titular nanny beforehand. One Hundred and One Dalmatians was, from start to finish, a feature film project that never detoured into short films prior to release. Peter Pan? Same thing.

Now, the Sherman Brothers autobiography states that the poor reception of Alice in Wonderland - a similarly episodic feature based on beloved and relatively plot-free British books - was what drove Walt to make this bizarre decision with Winnie the Pooh. That seems to hold some weight.

If this all was indeed the case, how come the third short - 1974's Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too - took so long to come to fruition? The third short, and the subsequent final third of the film, is very much a post-Walt affair. More than anything, it was a training picture for many of Disney's then-new animators, including a returning Don Bluth. You can tell Bluth's animation from a mile away when Rabbit gets lost in the woods, for sure, as he can't keep his tongue in his mouth. The story appears to borrow from various Winnie the Pooh story LPs that Disneyland Records released throughout the end of the 1960s. (Blustery Day also first came out in record form in 1967, a year before the animated featurette's December 1968 theatrical debut with the flop live-action film The Horse in the Grey Flannel Suit.) It is unknown what the final third of Walt's unmade Winnie the Pooh film would've been.

Lastly, it is not as if Winnie the Pooh *wasn't* known by Americans pre-1966... So that seems to render the "Walt was unsure if American audiences would see a feature about that character because he wasn't well-known by Americans" claim moot. I firmly think the real story is, "Walt Disney's Winnie the Pooh", was a lot like the original Leica reel for The Wind in the Willows that was put together in 1941. The Wind in the Willows, based on yet another British literary classic (Kenneth Grahame's story of the same name), could've been the next feature-length film after Bambi's release in 1942. Animator Frank Thomas, of course one of Walt Disney's "Nine Old Men", explained in an interview that the Leica reel ran roughly 48 minutes long and did contain story problems. That no doubt pushed it back, as did World War II's effects on the animation wing. Wind in the Willows eventually wound up as a roughly 35-minute segment of the 1949 package feature The Adventures of Ichabod & Mr. Toad.

Walt seemed to have found the Pooh stories to be too fluffy to sustain a roughly 70-minute movie, and figured releasing smaller films based on the stories was the better option. His Winnie the Pooh film was initially planned for a 1965 release, almost two years after The Sword in the Stone and two years before The Jungle Book eventually came out, which partially explains that four-year gap between those two pictures. Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree debuted in February 1966 ahead of The Ugly Dachshund, and was heavily marketed as a double bill, and to no one's surprise, the stuffed bear cartoon completely overshadowed the Dean Jones dog movie. I don't think a Pooh feature was in the cards after that, for the next film after The Jungle Book was The Aristocats, which Walt signed off on before his death in December 1966. Being short films, both Honey Tree and Blustery Day could be shown and shown again on television, which they were. They kept the character a household name, audiences didn't have to wait years for a re-issue like they had to do for longer Disney animated films.

For whatever reason the Walt Winnie the Pooh movie was cancelled, The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh is still a Frankenstein creation. The 1974 Tigger Too short is not from the Walt era and is its own entity. So in the Disney animated feature "canon", you have a film with 2/3s of it coming from an unmade Walt Disney feature released in two parts from 1966 to 1968, and another 1/3 of it from something conceived well after that. Then you have the "goodbye" ending, which reportedly was once meant for the Blustery Day short. John Walmsley, who voiced Christopher Robin in that portion, voices him here too, which seems to confirm that it was indeed meant for it. Plus, it reuses some animation from a scene in The Jungle Book, which - again - opened a little over a year before Blustery Day debuted. If Blustery Day had been the final cartoon with that ending, it would've been a fitting sendoff being Walt's final animated work that he was alive for most of.

Quite funny how this Winnie the Pooh film is a big honey clustercuss, with a strangely convoluted history... But it's always been thought that it all works together anyways, whether you know the history of the film or if you don't. Ex away the history and the Frankensteinian structure of it, it's a charming anthology of stories about these stuffed animals going on fun misadventures and a nice bittersweet ending to top it off. It works completely fine as a 74-minute animated feature film, and the stories' aimlessness make it work in its own fun way.

To make matters even weirder, in 1983, Walt Disney Productions let out another 25-minute Pooh featurette, Winnie the Pooh and a Day for Eeyore. You would think this one was meant to be a training vehicle for new animator hires, but weirdly enough, it was completely outsourced to a studio called Rick Reinert Productions. The new animators instead worked on the featurette Mickey's Christmas Carol, which debuted later that year.

It occurred to me that there's an album that I love whose assemblage is very, very similar to how the 1977 feature The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh came together...

The Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour...

Magical Mystery Tour was a surrealist television film that was made in the wake of the death of The Beatles' manager Brian Epstein. Six songs were newly conceived for this 50-or-so-minute film, which would air on the BBC on Boxing Day 1967. (That's December 26th for any Americans reading who may not be familiar with such a holiday.) Coinciding with the release was a six-song double-EP set a few weeks prior. An EP - "extended play", typically, was the same size of a single: A 7-inch record. Singles had one song on one side, and one song on the other. A-side, B-side. An EP could contain up to four songs on the record, and The Beatles were no strangers to the EP format. EPs seemed to be a much more popular kind of record in the UK, too. The Beatles' American distributor, Capitol Records, felt a two-EP record set was not viable for the US market...

Capitol Records is best known by Beatles historians for their Frankenstein-like assembling of albums. A single album in the UK like Rubber Soul could have its tracks spread across, say, THREE albums in the US. All of this mangling would eventually stop by 1967, with the seminal LP (long-player) album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band being the first Beatles album to have the same tracklisting in both the UK and the US. (With only a minor little difference between the two.) In Beatles tradition, some songs were never meant to be anything but just singles. For example, in 1966, there was The Beatles album Revolver, and a single: 'Paperback Writer' b/w 'Rain'. Two songs meant specifically for that single 7-inch 45rpm record.

In 1967, The Beatles released three singles. The first of which was 'Strawberry Fields Forever' b/w 'Penny Lane', released in February 1967. Both songs had been conceived for Sgt. Pepper, but because of a relative lull in releasing anything (Revolver had come out in August 1966, and there was - unusually - no Christmas market single release that year), it was decided to have those two songs be a single instead of tracks on the upcoming album. Next was 'All You Need Is Love' b/w 'Baby You're a Rich Man', released in July 1967, nearly two months after Sgt. Pepper. Last came 'Hello, Goodbye', on the B-side they attached the Magical Mystery Tour song 'I Am the Walrus', which later appeared on the two-EP set.

In the US, Capitol Records had all six songs from the movie put on side one of their Magical Mystery Tour LP. Side two would be the five other songs that The Beatles released in 1967, in order: 'Hello, Goodbye', 'Strawberry Fields Forever', 'Penny Lane', 'Baby You're a Rich Man', and 'All You Need Is Love'. Altogether, this is a very strong 11-track sequence. No surprise, that album shot to #1 on the charts, and it even got imported to the UK in early 1968 and charted as high as #31 - despite the EP and the separate singles existing over there. It works so well as an album, and as an equally psychedelic sequel to Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band... even if it was never conceived as such in the first place.

And the weirdest thing is, the Magical Mystery Tour MOVIE was never aired in America, even though the LP came with a picture story of the movie. The movie itself had gotten such bad critical and equally poor audience reception (I'd imagine a lot of the viewership was families tuning in on Boxing Day to watch something together, and they got a weird aimless psychedelic home movie that confused the hell out of them), that ABC opted out of broadcasting it in January 1968-ish. So, Americans wouldn't really get to see that film until midnight showings occurred in the mid-1970s, followed by belated TV airings...

Oh, and the Magical Mystery Tour movie, much like Many Adventures, is just a silly delightful parade of whimsical misadventures...

#winnie the pooh#the many adventures of winnie the pooh#the beatles#magical mystery tour#disney#disney animation#1960s#1970s#random history

0 notes

Note

What would you say is your favourite decade in fashion, favourite decade in visual arts, and favourite decade in music?

this is such a difficult question oh my god!! but thank you anyway i’ll try my best! So in fashion- as in terms of like. western popular fashion and what we associate with the decades i really like the patterns and themes in 70’s fashion- esp for mens fashion! but in terms of my actual favorite- the late nineties-early 2000’s was such a good time for harajuku fashion that its hard to resist! The times where jfashion was kinda at its height and where styles like gyaru were widly seen. I don’t think that its true that a lot of these fashions are “dead” more that other fashions have become more popular in harajuku than the ones western audiences recognize but it’s always exciting to see how things started.

For visual arts- this ones the hardest for me because my favorite artists are mismashed across decades and the ones i draw a lot of inspo from seem. kinda weird in the perspective of things! I also am so in love with the art world right now that it’s hard to leave some of my favorite things about currernt art behind as we go back in time. Despite me being a 2d artist, installation art has always been a weird sort of insportation for me, which started finding its roots in the 70’s despite the concept arguably being invented well before that. I also adore the kind of like “tacky” art of the 60’s and 70’s that were found hanging on the walls of most houses, bought cheaply and mass produced. (Margret keane’s “big eye” painting are a good example) We actually have several of these kind of paintings around our house and i rather like them, despite due to their nature of being mass produced are often not seen as much! This is also kinda a weird thing to say but i adore when digital art was first finding its footing in very early internet days and the communities of people that developed around it. It’s always funny to me when i see a “how to draw anime” book in like a used bookstore bc tbh the art is never what people would consider “good” today seeing as it is so common now to see western anime style art. but like. i really adore that kind of attitude to just make art bc you like it and you want to draw anime but there was no real pressure it seemed to make it actually look like what it looked like on screen? Idk how to describe it. But we hold today’s young artists to like stupidly high standards and i really liked how it was seen as impressive to just be able to use a digital program at all bc tbh. it is!

and for music. I have to say mid to late 90’s- early to mid 2000’s. If you’ve been following me for a while you know one of my major intrests for the past two years has been the ‘twee’ and ‘cuddlecore’ music movements- a relativly small collection of indie bands with a cult following. Idk how to describe twee other than like. stupidly comforting, but the proper defintion is gentle and/or happy indie music that has more of a focus on childlike innocence and less of a focus on production. It’s carefree, has a lot of cutesy lyrics about love and sunshine, and has lots of off key singing and background noise. If you want to research, some of the bands i reccomend highly are: Tiger trap, All girl summer fun band, The softies, Tullycraft, The pastels, Talulah Gosh, Go sailor, and Heavenly. The 90’s is possibly also my favorite wave of power pop (more ppl know this genre but generally the gist is its guitar based music heavily influenced by but not nessceraliy the same genre as popular 60’s-70’s pop bands the the kinks, the monkees and the beatles.) Bands from this era i love r : fountains of wayne, myracle brah, the minders, gigalo aunts.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

so i ran into this quote by paul from hunter davies’ book where he is sort of describing the other three and yeah uhm, wtf: “John – he’s got movement. He’s a very fast mover. He sees new things happening and he’s away. Me – I’m conservative. I feel I need to check things. I was last to try pot (dawg the four of you literally smoked together for the first time) and LSD and floral clothes. I’m slower than John, the least likely to succeed in class. When a new Fender guitar came along, John and George would rush out and buy one. John because it was new and George because he’d decided definitely he’d wanted one. Me. I’d hang around thinking, check I had the money, then wait a bit.”

+ he goes on to stay that out of the four of them he is the most conservative but compared to other people he is still a freak

and i mean.. first of all, putting aside the weird way this is phrased - which does make me wonder how much of this was actually said by paul and how much of it is a compressed, weird summary of what paul has said (which i feel like does apply to these parts all throughout the book)-, and the straight up stupidity of the “least likely to succeed” bit (?????) , uhm yeah what the fuck, right. like, jesus.. not jumping aimlessly onto new trends in a rapid way doesn't mean you're slow. not switching from one new (often toxic) obsession to another on a daily basis doesn't mean you're slow. being from an actual working class home and having had to spare money, which had a long-lasting effect on you, doesn't mean you're slow. using common sense doesn't mean you're slow paul, for god's sake. but it's not even this messy quote that bothers me, it's the fact that this is a well-liked, popular narrative in the beatles lore and fandom too, you run into this all the time, that paul was always just a few steps behind, he was never down to try new things, he just “didn't understand it” etc.

which we know is bullshit, but anyway in my brain this tied in with another thing i've been thinking about in the past few days, and it's the absolutely insane amount of material paul has written throughout his career AND how many of his ideas appear "unfinished" or "underdeveloped" and that this is probably caused by how fast and impatient he seems to be in terms of creativity. like there's just so much going on in his catalog, especially if you look at the stuff that at the time was unreleased or it still remains unreleased, it's wild. it's fucking mad how prolific he is in terms of songwriting. and on top of that there's an incredible diversity and speed in his work, like he literally just can't stay in one place for too long, he always seeks out change and improvement and new ways, being inventive etc, it honestly seems like there's just way too much going on his head and even before he finishes what he's working on, his mind is already onto the next thing and his brain is travelling extremely fast. and so sometimes i get the impression that while he can definitely be a perfectionist, often he’s just unable spend too much time on one thing and i feel like there are so many songs that would have deserved more time devoted to them but he was probably like okay idc i want to move onto the next song/project/etc, i want to do something different, i already have a bunch of new ideas and i'm dying to try them out.

so this is why i find these statements so silly and nonsensical. like why does i don't know, not trying LSD for a while (which is very commonly brought up to support this), mean he's slow, when in so many other aspects he's miles ahead of everyone.

[also this lsd theme is so dumb, like instead of acknowledging that yeah despite the group pressure that was placed on him, paul always did things whenever and however he wanted to and he did not give in when people/his bandmates pressured him and how this shows his strong presence and personality, so instead of giving credit to him for that, he's always made to be seen as weak, lame or boring. for sure he is often rightfully wary of certain things and he's a man who's able to use common sense, but how is that a bad thing? that's an extremely valuable, great and useful trait. he's savvy. but of course in the meantime he was the first beatle to get into the london avantgarde world, plus he was also the most involved in it and he snorted cocaine for breakfast. but yeah he's slow i guess]

[also describing john’s rapid, often stupid decisions, the (self-destructive) way he was jumping from one obsession to another, the way he devoted himself to new trends or new people in the hopes of finding something that would fix his life or give meaning to it (lsd, maharishi, yoko, klein, heroin, the peace movement etc) whatever, so calling all this just “fast”... yeah that's kind of an understatement]

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In a revealing interview for the Image Source Picture Library, I talked to Miles Aldridge about his early influences, 90’s fashion photography and how at the moment of news-stand success he headed off in a radically different creative direction.

Miles Aldridge shoots sexy, glamorous women in opulent settings. But all is not what it seems in his pictures. Scratch the surface and a common thread runs through the imagery – the strange ominous unease of the dreamworld. Film-maker David Lynch wrote, “Miles sees a colour coordinated, graphically pure, hard-edged reality”. Artist Glenn O’Brien says Aldridge, “uses impeccable instinct in crafting something like ‘stills’ from the fractured narratives that we normally experience nocturnally and unconsciously.”

Aldridge talked to me about his influences and traced the rich visual journey he took from being a graphic design and illustration student, through music promos, to being a photographer who has shaped and stretched the idea of the fashion photograph.

Ashley Jouhar: What was your background to taking the kinds of photographs you take now and what was it that kick started your career in photography?

Miles Aldridge: Well, my father [Alan Aldridge] was a famous illustrator and art director so I grew up around quite surreal, psychedelic and sometimes shocking imagery – and it seemed clear to me I would go into the arts and follow my father. So I went to art school to study illustration, which was incredibly liberating – because I had been at Grammar School and none of my fellow students were interested in art. Being at Central St Martin’s around 1983 – surrounded by a lot of like-minded and talented people – the teachers, the studies and the classes were very good and I immersed myself in everything for the first year and then specialised in Graphic Design with an illustration bias.

Ashley Jouhar: So at that point you were exposing yourself to all the disciplines – life drawing, filmmaking, illustration, graphic design – the whole lot?

Miles Aldridge: I was also getting exposed to cinema, taking girlfriends on dates to see art movies, not blockbusters. I was seeing David Lynch films and it broadened my horizons immensely.

I did become an illustrator when I graduated from art school but I found it quite boring and I wasn’t anything like my father who was a sort of psychedelic whizz kid right in the middle of swinging London, working with everyone from David Bailey to The Stones and The Beatles. So he was really tapping into the zeitgeist. But I didn’t find the work very challenging and I was still very young so I started making enquiries about pop videos. It seemed to me that the film directors I liked were artists, packaging their thoughts and point of view of the world into hour and a half statements.

Ashley Jouhar: A little like you are now doing with your current imagery, except in a photograph?

Miles Aldridge: Yeah, but at that time I had no film training, apart from a couple of days at art so it was all quite new to me. But I bought a Super 8 camera and started shooting films. Then I bumped into Derek Jarman in Soho, who was often drinking tea in the same café I used to hang out in called Maison Bertaux. He was interested in me because I was a good-looking young man and I was interested in him because he was a famous film maker and so we had a few conversations. He was very enthusiastic and encouraging and through this naïve enthusiasm I started to make films. Another person who came into my life then was Sophie Muller, a well known video director who pretty well invented the form, shooting videos for The Eurythmics and many others.

Ashley Jouhar: MTV was exploding at this time so it was perfect timing for you, in the right place at the right time?

Miles Aldridge: Yeah, yeah, exactly and actually because of people like Derek Jarman and other like-minded artists were doing Super 8 presentations to music because of its relatively low cost it was very much the film medium for the 80s. You don’t need masses of finance to make a film on Super 8 – the idea is translated quickly to images. So I started making pop videos for a while.

Ashley Jouhar: Were you coming up with the concepts for these videos – were they very much ideas-driven shoots?

Miles Aldridge: Yes, very much so and I was good at coming up with the ideas but I wasn’t very good with the music! I would come up with an idea that might be loosely based on something from the universe of Hitchcock, Lynch or Godard and I was aware of cinematic tricks and conceits and would play with those. Like for instance, The Shining – I would do a pop video based on a long corridor with different weird things happening in different rooms but I didn’t really know how to put it all together with the edit. During this time I suppose I would have been known as a middling pop video director and therefore lived in a council flat, didn’t have any overheads as such so was very happy doing the odd pop video and hanging out with my girlfriend, who it transpired wanted to be a model. That’s when I took these photographs of her because she looked very much like the kind of girl of the moment – that sort of grungy, heroin chic sort of look of the time.

Ashley Jouhar: I remember it well – the bed-sits and anti-fashion poses.

Miles Aldridge: Yes, and the pictures of her were very well received at Vogue and they asked who had taken them and it was explained that it was this girl’s boyfriend. I was then called in to Vogue to meet them and I had this amazing realisation that instead of all this hard work involved in making videos – starting at five in the morning and ending at five in the morning, horrible food and no money to do anything, I could possibly become a fashion photographer.

Ashley Jouhar: So those original pictures, did you imbue them with something that we would recognise now in your work?

Miles Aldridge: No, I shot them all in black and white on Hampstead Heath on a Nikon and the film was dropped into Snappy Snaps… and picked up two hours later and pasted into her portfolio! They were really, to all intents and purposes, a boyfriend photographing his girlfriend. I mean she wasn’t styled and there was no hair and make up and she wasn’t trying to sell any fashion. Because that was what was happening with London photography then, when fashion photography almost slipped into Reportage.

Ashley Jouhar: Yes, it was very pared down compared to what had gone before.

Miles Aldridge: Yes, very much so and the heroes of that period were people like Robert Frank and Bruce Davidson and also Richard Avedon’s book ‘In the American West’ was kind of like a bible for that kind of styling.

There was this idea of real people rather than glamorous people being pushed to the forefront and being shown as something heroic and wonderful. So I moved from illustration to video to photography in the space of about six years, I think. I really enjoyed the photography and the early work was really about being locked in studios with very beautiful creatures and trying to think how to photograph them. I didn’t come with any technical knowledge – all I had was an eye that still serves me very well today and those pictures were almost a repetition of the boyfriend/girlfriend pictures earlier where in my imagination, these models who were now wearing fashion clothes and hair and make up were, for that six or seven hours in my studio, my girlfriend. Interestingly, when the hair and make-up and styling was being done and I wasn’t paying any attention at all, I left that up to them. In a way, I liked to rendezvous with the model on the white background and see her there for the first time with my camera.

Ashley Jouhar: So at this point your shoots were very spontaneous with what was happening, there were no storyboards planned out or themes?

Miles Aldridge: Yes, it was very spontaneous, it was about having a good time, listening to loud music and being swept up in the energy of a pre-9/11 fashion shoot and I mention 9/11 because after that, the whole world and especially fashion became much more gloomy and serious. Up until that point it was a big party. There was so much energy and money sloshing around and I enjoyed the decadence of it.

Ashley Jouhar: When did you start shooting in a more ‘David Lynch-ian’ way with these very considered, choreographed images and sets?

Miles Aldridge: Well, literally all I was shooting was white background pictures for magazines like W and British Vogue. Those pictures were about energy and shapes and in a way my talent was in trying to find graphic shapes on the flat two-dimensional page. I was successful with that kind of work straight away and sort of fell into it but at a certain point I looked at all this work and I remember I was at a magazine store in New York and saw a cover for W magazine, a cover for British Vogue and a cover for a magazine called Vibe – three white background covers, all by me. One could feel really good about oneself with that but for some reason, seeing them all there together I kind of loathed it and wondered where I’d got lost. Because back when I was an art student and even doing pop videos I was much more interested in darker and stranger things and the books I grew up with were books on Hieronymus Bosch and Breugel. The complete opposite of what I was producing, which I thought was trash. I felt really uncomfortable about that, even though my pockets were full of dollars.

Ashley Jouhar: So this was the turning point?

Miles Aldridge: I realised that when you get into a photo studio as a photographer, even if you said nothing and were dumb, the picture would still get taken because there is the momentum the stylist, the hair and make up artist and the model bring to the shoot that creates the energy for these pictures to occur. Instead of giving myself up to the madness and the freedom of the shoot, I wanted to put the brakes on it – to divert that energy and create a picture you really want to do in advance.

In part 2 Miles tells us how he creates the ‘fantastic’ images that have become his signature pieces…

#fashion photography#miles aldridge#vogue italia#british vogue#art photography#art#ashleyjouhar#pop art#david lynch

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Labels: Liability or Liberation? Or, into what would you change in a metamorphosis machine?

As a child, at grown up parties, I used to resent being paired up with another child, purely on the basis of sharing their age and gender: “Oh, my little girl is 7 too! How lovely. Off you go and play. I’m sure you’ll get on.” My best friend at 7 was a 2 year old boy who lived opposite us, so even back then I felt the absurdity of this logic and wanted to retort: “My mother has just turned 40. I hope you are in your forties too, otherwise I don’t suspect you’ll have much in common.” I was reminded of this problem when I first became a mother. I dutifully went along to the mother and baby groups where I was meant to find friendship and support. I didn’t. We were meant to connect because we all had newborns. Sometimes it works – I have heard others tell of lifelong friendships formed at an NCT groups – but as often as this I have heard women describe coming away from such groups feeling isolated and depressed. The very thing that is meant to join us can divide, because our experiences of motherhood are so different and so diverse.

Motherhood is huge. Being a mother is as immense a category as being a girl or being aged 7. One of the Mothers Who Make principles is that ‘every kind of mother is welcome’ – breastfeeding, bottle-feeding, adoptive, surrogate, step, new, grand, bereaved. Right from conception onwards the range of experiences that live under the label of ‘mother’ is mind-boggling and heart-wrenching, everything from the suicidal to the ecstatic to the mundane. However, this momentous range of different stories is not just down to the mothers. There is also the question of who turns up - who happens to land in your lap under the category of ‘child.’

Up on the walls of both the rooms in which our children were born, my husband and I put up a set of principles from Open Space, a format we use to hold creative, self-organising conferences. They are useful principles not only for holding a meeting, but for life. The first of these is: Whoever comes are the right people. In the context of my labour this meant that whoever made it into the room – my husband, midwives, doulas, granny- were the right people to be there. It also meant that whoever came out of me would be the right baby. Why? Because that is who turned up. I have been thinking of this recently in relation to my son. I am holding fiercely on to the belief that he was the right person to show up in the world 7 years ago because I have been confronted with the idea that there is something wrong with him.

To label or not to label? That is the question. Do labels limit or liberate? My son has been referred, via his school, to a child development centre. I had to give my permission for this to happen. I said yes, and then worried about what I had done, because I imagine we will come out of the process with a label for him, a new name for who or how he is. Most of the labels involved are awkward mouthfuls and so they are reduced to acronyms that take on a kind of magical power of their own: ADHD, ADD, HFA, ASD, SCD (For the uninitiated into this particular magical cult, these stand for things like Attention Deficit & Hyperactivity Disorder, High Functioning Autism, Social Communication Disorder). At the start of the summer I played a silent game of trying the labels out as I watched him, sprawled on the floor amidst hundreds of comics, or hopping up and down, biting his fingers, narrating another epic tale from his latest fictional world, or snarling at me if I interrupted him to try to get him to eat. Ever since he was 2 he has gone from one ‘world’ to another. Each world is inspired by a comic, book or film, but he is not a passive consumer. Instead he takes each set of characters and makes up his own stories with them, tales that usually involve social misfits and tricksters, sickness and sadness, best laid plans and terrible defeats. Whilst the themes recur, the worlds themselves are impressively eclectic: The Octonauts; Thomas the Tank Engine; Lightning McQueen; The Beatles; Star Wars; My Little Pony – to name but a few. Until this summer I have seen my son’s relentless story-telling, sudden aggression, wide-awake-till-midnight tension, as being ‘just who he is’ – the amazing boy that turned up in my lap. This summer, as I played my ‘labelling’ game, I remembered the process of naming him - we had to do it fast to get him his passport and it struck me as an extraordinary power to have, the power to name this raw, red little baby, to give him a word by which he would be known for the rest of his life. I remembered as I child how I used to repeat my own name over and over until it emptied of meaning, was only a sound and no longer me, and then I didn’t know who I was anymore, and it felt weird and dangerous.

But names can useful. Labels too. They can make it easier to balance, to connect and communicate, depending of course on what they are and within which societal context they exist. When I fill in a form I put down my name, that I am female, 45, married, British, a mother. These are, mostly, very privileged boxes to be able to tick. There is no correlation between the size of the box - big enough for a tick or a cross and no more - and the immensity of the categories each contain. I do not identify with all mothers, all 45 year olds, or all women, but the labels can be a handy, albeit crude shorthand. For sure we need a box for non-binary people too, and other marginalised groups, but that is a request for more boxes, not less. By the end of July I had decided that I should not dismiss all boxes as bad and that having a label for how my son is could make some of his interactions with the world easier.

I thought I would test out the label out loud. We have not yet received a diagnosis but I thought I’d pretend that we had. When my son next got upset in public, storming up to a woman behind a membership desk in Kew Gardens to complain that a section of the play area was shut and threatening to close down the whole gardens, I murmured to her, “He’s on the spectrum.” She pressed her top lip onto her bottom one to make a smile - “I had gathered that” she said. That was it. I wanted to hit her as my son had just hit me when I tried to prevent him from making a scene. Now I wanted to shut down the gardens. And under my rage, as is always true of my son’s rages, I felt incredibly vulnerable. Was this potential label, that felt so new and strange to me, his mother, blatantly obvious to the rest of the world? Had everyone else known for years?

It has become my practice, when anything is bothering me in my mothering, to align it with my making and see what it reveals. When I thought about my writing, I realised that there are different layers of labels in operation. There is the top layer, those labels that are to do with my primary, outward identity, the ones for the boxes, the ones I have to be brave enough to use to put my work out there: “I am writing a novel,” I tell people at the moment, the label of ‘novel’ still being difficult for me to own with ease. I have to decide too on the kind of novel I am writing – is it for grown ups or YA? (the acronyms start up again). But there is also a deeper labelling process in which I am engaging as I write the book itself. Language is a labelling game. My daughter, aged 3, knows this. She is interested in what objects begin with the first letter of her name - ‘T’. She feels she must have a deep affinity with anything that shares this letter. I bought her some letter stickers - “Where can I stick this?” she asks me, holding up an ‘F.’ In truth she can stick it anywhere she likes, but I know she wants to make the word and the world match, so I suggest she sticks it on the Floor or Fridge. When I write I too am on a quest for matching, for finding patterns, making meaning. When I think of it in this way a label seems much more creative– an attempt to find the words for our emergent patterns of experience. A label might be, not a fixed little box, but more like a room, a large space into which my son could be invited to enter, a space as wide as the word ‘spectrum’ implies. I like that word. It suggests breadth. Diversity. Colour. It makes me think of good art – not a room with one view but a structure generous enough to hold many different views and possibilities– and this in turn makes me think of my son’s longest held ambition: he wants to make a metamorphosis machine.

My son wants the ability to change into whoever he wants. Every now and then he will get sad because he fears that he won’t be able to do it. My husband and I tell him that as an artist he can be whoever he wants. He says that is not good enough – he wants to change for real. I try to explain to him as best I can that ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ are not such fixed and separate categories as they seem – the one effects the other and even reality is porous. Language is a big part of this porousness, it being a made-up thing that we use every day to talk about real things, and all the while we slip back and forth, without even noticing, between metaphor and matter. When I went to the recycling centre recently my son grew excited by the skips full of old electrical equipment and broken strip lighting – “Can we take some of those away for my metamorphosis machine?” he asked. We couldn’t and I wanted to tell him that the way he remembers almost every story that he hears, word for word, the way he makes puns and crazy verbal jokes, is what, I believe, will provide him with the best materials for building his machine. And when he has done it, it will be his and, as he reminds me, he will be in charge of it. He will be able to become to whoever he likes, whenever he likes. I think this agency is key – he will be in charge of the labelling. He will name himself.

We are proceeding with finding a diagnosis for our son but if we get one – and we may not as I have been told that certain labels can be hard to come by - I want to give it to him as a present. I want it to be a name that he can use as he sees fit, for when it fits. I want him to do the fitting. I want it to be a name that has space inside it, not a closed box, but a great big generous word which can hold a myriad of experiences, as the words ‘mother’ and ‘child’ do. I want him, above all, to know that he is the right person to have showed up in the world 7 years ago and that it is okay if there are other 7 year old boys with whom he has little in common because difference is a good thing and now, more than ever, the world needs diversity. We certainly do not need more, and more, of the same.

I’ll let you know when my son’s metamorphosis machine has been made and patented, but in the meantime, here are my questions for you for the month:

What labels do you give yourself? And your child(ren)?

How do you experience them? Do they limit you? Or liberate you? Are there ones you want to change? Are there ones you are afraid to use? Who or what would you wish to become if you had a metamorphosis machine? How can you begin to be that now?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why MBA?

Like several many in India, I was an engineer. I set up part of wireless mobile network at Huawei Telecommunications. I started as a Graduate Engineering Trainee and soon was working independently, with minimal supervision and later was leading teams. After working for 2 years in various engineering functions I felt that my job was getting repetitive and wanted to try something new.

It is common knowledge in India that MBA is the key to a better salary, changing functions and becoming a Manager. So I was in the process of taking the Common Admission Test (CAT) and it’s siblings XAT, FMS etc. in 2009. Having appeared for those exams in 2006-07 during my senior year of my engineering undergrad, I wasn’t too hopeful. At the same time I came to know of my seniors who had graduated in a year before in 2006. They recently enrolled into institutes like Schulich School of Business at York University, Toronto, Canada and Asian Institute of Management at Philippines, Manilla. I knew about the GMAT exam, but never gave it a serious thought since I never had the money required to pursue a Masters from abroad. My seniors told me that it’s possible to get scholarships based on the GMAT score.

A bulb just lit in my head. “So maybe I’ll crack the GMAT, get a full scholarship, get my MBA and make tons of $$$ - easy!!” I was at 24 and full of hope. I found a used Kaplan GMAT book - erased the pencil marked answers and spent like 2 weeks preparing. I took the GMAT got 600. Not earth shattering and I knew people get into schools with that score. I checked the average GMAT scores under class-profile and most said 550-750. So I believed I was in the ballpark. Since all schools mentioned on their website that they look at candidates holistically and not just the test score, I thought “I will write stellar essays and get through”.

Why do I want to do an MBA? To earn a bucket load of money. Ok, this was simple, but I cannot write that up in my essay. In my essays I wrote that I wanted to pursue a career in Brand Management. I knew very little about marketing as a whole let alone brand management. My experience had no overlap with that business unit. I had no target companies where I would pursue a career post MBA. I had no preference for location. I never cared to connect with anyone working in brand management to learn more. All I really wanted was to make the big bucks. Doesn’t matter how.

I met several people from admission committee (AdCom) during The MBA Tour and QS World MBA. I had good conversations with everyone including Mason School of Business - College of William and Mary. So In addition to Mason, I applied to schools like Kelley at Indiana University, Case Western Reserve in Cleveland, Wake Forest University etc.

Meanwhile, I retook the GMAT since statistically speaking, people see an improvement of 70 points on their 2nd attempt. First section AWA. Done, next up was Quant. Like most Indian applicants I had little trouble with mathematics so quant is kinda easy. Section over, now comes the Achilles’ heel – Verbal. I knew GMAT was an adaptive test. It was critical for me to get the first few questions correct, otherwise my score will dip. One by one I answered the questions to what I thought was correct. After all it sounded right to my ears when I spoke it in my mind. I mean, I communicated in English just fine! I gave TOEFL without any prep scored 105 off 120. I was taught in English throughout. Heck I was into AC/DC and The Beatles.

At the end of the exam, I had a choice to see my score and submit or to cancel. My heart was pounding, I was sweating, I was praying for a good score to flash on the screen. What will it be? 650, 680, 720?

610

After the anxiety comes the feeling of dejection. But I had hope. I had good conversation with several AdComs I meet during the MBA fair. I decided to focus on my application. Wrote essays, reached out people for recommendation. Completed and submitted my applications. I was awaiting information on the next steps. I couldn’t sleep well. Was getting up early to check my email since it would be evening in the US when people would have replied.

I was elated to see an Interview invite from College of William & Mary! I suited up at midnight India time for my telephonic interview with Amanda Barth. The interview started well, but during the conversation she asked me “Why do you want to do MBA?” I panicked, words weren’t coming into my mind. I choked and bombed the interview. Few days later, got the result. Denied. Which was a common theme for all my applications – most without even an interview.

I was devastated. Not only had I spent so much money and effort I lost a year of the admission cycle. I locked myself away from everyone and everything for the next 5 months. I had many questions, “Why do I really want to get an MBA?” “Why do I feel that I have reached a ceiling in my career?” “Why does my job feels repetitive?” Earning money was a byproduct, cannot be the cause.

I reached out to several current students, alumni, AdComs and tried to better understand what makes an MBA student employable at the end of a 2 year program? How is that students come in thinking they would do Finance ends up doing Marketing? Then I slowly started to see myself from skills point of view. What skills do I have now? What skills am I missing for the job that I want to do? The difference is my skill gap. Can the MBA help me bridge that skill gap?

(pic: Ayon talking with Sonja from Hult Business school at QS MBA Tour 2010. Photo published on Education Times, July 12, 2010)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Machine Gun Kelly Claims High Of The Pop Charts With ‘Unhealthy Issues’

^ F. Holt, Style in Common Music (University of Chicago Press, 2007), ISBN 0226350398 , p. 56. Music contributes enormously to our lives as Christians. We sing, or at least sing alongside, in church, at dwelling, at parties, and even in the automotive to music from a whole bunch of composers, vocalists, instrumentalists, producers, and other artists stored on our smartphones, streaming companies, CDs, and radios. Christians in past centuries could not even think about such convenience or quantity. Yet music in church is a topic that has been a source of appreciable controversy over the past quarter century. As a music professor at Providence, and as a composer and former church music minister myself, I have usually pondered the many differences of opinion. Here are a couple of ideas, a few of that are extracted from my article printed in the June 2011 challenge of Christianity As we speak.

Authoring a song that might launch almost a a hundred covers, ‘Hallelujah' is just a small sliver of Leonard Cohen 's immense contribution to music over the previous five a long time. The completed poet and https://www.goodreads.com novelist was the toast of the Montreal literary scene earlier than he turned to music to become the foremost songwriter of his era. His meditations on love, faith, despair and politics might be conveyed in even the simplest of terms. Songs like ‘Suzanne' and ‘Chook on the Wire' and ‘Sisters of Mercy' would cement his popularity as a in-demand folks songwriter, spawning hits for countless other artists, but nobody could substitute Cohen's deep, resonant voice.

It's a huge mission and out of necessity Stanley is compelled to condense entire fascinating histories that probably deserve their own guide into only one chapter (I might love to learn a e-book concerning the Brill Building scene, for example, or riot grrl, about which I stay largely ignorant), however he's clearly acquired endless enthusiasm for pop and his dismissive angle to rockist bores or really anybody who takes themselves too seriously (fans of Patti Smith, Radiohead & The Doorways take be aware) is good.

Love Yourself 轉 'Tear' is the third Korean studio album by South Korean boy band BTS. The album was launched on Might 18, 2018 by Massive Hit Leisure. It is accessible in four versions and accommodates eleven tracks, with "Fake Love" as its lead single. The concept album explores themes regarding the pains and sorrows of separation. It debuted at primary on the US Billboard 200, changing into BTS' highest-charting album in a Western market, as well as the first Ok-pop album to prime the US albums chart and the very best-charting album by an Asian act.

Frankly I do not care if the music is pop or rock. Simply the tune and the lyrics needs to be my style and wise. I follow four rock bands :Disturbed, Evanescence, Breaking Benjamin and Within Temptation, cause I just really feel calm or evernote.com nice or excited by their music. I am only talking in regards to the songs, not the concerts because I reside in India and I've never been to any concert events. One of the important causes I don't like pop music a lot is as a result of they're all the time so cliched. It's both love songs or partying or drugs or sex. I am just feeling so damned tired of trendy pop music. I'm additionally afraid that rock is creating those type of attitudes and that is why I stick with solely 4 bands. In case you guys may suggest a brand new track for me, post your touch upon cretoxyrhinamantelli@gmail. com.

That does not essentially mean that stupid people love pop — just that pop trains us to count on much less from our inventive and creative lives. Music can nourish our minds like almost nothing else, so when a mega-trade is devoted to selling the least inspired music they can, they're short-altering all of us. A survey of different research on music reveals that pop music has gotten worse over the last 50 years. Not only that, it's been used to brainwash listeners by way of predatory marketing strategies across all media channels.

Do it sure? Or just keep behind some random hate weblog whereas having the most boring job of your life every day the place you are taking out all of your frustrations on a kind of music recognized throughout the world that does not even make it's a must to take heed to it. Folks say they don't seem to be fairly sufficient or they don't look too good everyday. It isn't simply in korean. It's in America, Europe, just about anyplace else you might consider. Guess what? In the event that they assume that means then they'll nonetheless turn out to be higher when they notice that they actually don't should attempt to be a sure look.

The sounds of the 1960's straddled a large dichotomy between the last word commercialism with fully manufactured bands (like The Archies and The Monkees) and revolutionary artistry (Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix) with a few of the greatest singer-songwriters and instrumentalists emerging on the scene. There were additionally many bands and artists that walked the line between commercialism and Http://Www.Magicaudiotools.Com/ musical innovation like The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, and The Rolling Stones. The Beatles dominated the charts and spurred on the British Invasion that characterized a lot of the last decade.There are two singers. Each are accused of abuse, and by many accounts, both have done lasting harm to susceptible individuals. Personally, I think one singer makes completely banal music, so it is simple for me to be self-righteous and by no means hearken to him again. (The buzzword people have been utilizing lately for that is "canceled.") The other singer, nonetheless, has written songs that I've loved for many years, and whereas I've never really doubted his guilt, eradicating his music from my listening life has proved tough.The chords and notes used in 2016's biggest hits aren't unique; they're the identical exact ones we've been listening to because the invention of modern music around 1750 But by shifting a few notes right here and there, present pop artists can hold their songs from sounding predictable and give them a extra open-ended tone. Instead of touchdown again on the chord we expect it to, these songs lift again up into another observe, making the song extra buoyant, stunning, and dynamic.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Anime Central 2019, Day One (Friday)

So, our Friday got off with a slightly rocky start. Some of us had to go claim badges still, some just had their usual morning routines delayed, etc. So in the hours between waking up and hitting the con proper, everyone was doing something different. @shbumi and I started off with Pokemon Go.

I had signed all of us for an escape room hosted by Experimental Gamer. And the time slot I chose? 10:00 - the exact time when the various areas of the con opened up.

Yeah, in retrospect, waiting a little may have been a better option. But sadly, it didn’t matter. Because we walked up to the room and got some bad news.

Although they were all set up, they were having computer issues. We were offered a refund right away, or the option to reschedule for later in the con - with the understanding that we would be refunded if things couldn’t be worked out. We still wanted to give the experience a shot, so we opted to re-schedule.

But then it became a “What do we do with ourselves?” In my case, I went back to the Hilton to grab my phone battery, which I’d forgotten. I figured I would snap pics on the way there and back. The others all scattered off to do their own things.

Once I had my battery, I went to a basic wig care panel with @el-draco-bizarro that was hosted by Oriana Peron - she had awesome tips. Sadly, as often as I have attended these panels and taken notes, stuff doesn’t stick. That would probably be why I have yet to wash the hairspray from my Catra wig from Acen...oops.

Still, my inability to remember wig care tips that I write down isn’t anyone’s fault but mine and I highly recommend Oriana’s panels if you can attend one.

During the panel, I was getting email updates from the escape room team. Our group was able to reschedule for noon. We’d chosen a sci-fi scenario for our escape room.

youtube

We got into the room area, and it was a wee bit cramped for 7 people. Actually, we had 8 people, since the rep from Experimental Gamer was sometimes in there with us. The room was functional, but not at 100%, so he was there in case we hit bugs that weren’t part of the scenario.

This poor lighting is honestly how things were at first - one of the first goals for any group is to get the power up and running. And, partly due to tech issues and partly due to our group splintering into smaller groups that weren’t always communicating, it took forever to get the lights on.

We kept stepping over each other but it was a very cool setup. Once we did get things running, we started making decent progress.

There were even weird specimens in jars and we got to play scientist!

Normally, you get 45 minutes to solve the puzzle. Because of the tech issues and, I think, because it was a slow day, the Experimental Gamer rep very kindly allowed us double that amount of time. We did finally solve the room in a way that allowed us to escape.

I would love to try their horror-themed room or even to do that room again, with everything working correctly. I hope ACen brings them back. I also hope they get advertised better, too - they were never listed in the guidebook app, and were announced only a week or so before the con, so they weren’t in the physical program book either.

From the escape room, we diverged again. My next event was rather educational.

Some of what was covered was common. Vampires as a way to explore forbidden aspects of sexuality, etc. But I wish I had taken notes, as there were a few aspects regarding werewolves that I had not considered. And they also spoke about Frankenstein’s monster and the impact of that story on culture. It was all super fascinating. I really am a fan of both of these individuals and when they pair up for an education panel, I know I’m going to enjoy it.

Afterwards, it was time to explore a bit. The Exhibits Hall (aka dealer’s room) was in the same area as it’s been since I started going to ACen in 2016, but that isn’t a bad thing. The layout gets tweaked a bit each year, though. Still, as usual, it had all kinds of merch and industry booths.

The Fate/Grand Order USA Tour was also making a stop at ACen. They had a really cool booth set up to explore.

The Bang Zoom! voice acting auditions were at Anime Central again, and as before, they were in a portion of the Exhibits Hall. This year, they were auditioning for parts in the Sword Art Online: Alicization arc and boy, was I actually tempted to go up. But there’s something intimidating about auditioning in full view of thousands of others. Still, I sort of regret not trying it. Especially as one of @lechevaliermalfet and I’s nieces has gotten into SAO - auditioning would have been a cool memory to share with her.

Eric Maruscak was back to do his usual thing. Like last year, he was in the Exhibit Hall. His art always turns out super awesome, and it’s fun to keep checking in on it through the weekend.

After wandering around, acquiring some merch (I now have a Gatomon plush and I am so happy!) and stopping back at the room at the Hilton, it was time for another panel.

(I didn’t realize until I started doing the write-up, but we went back to the rooms more than I thought we did. Well, we had to eat, and that’s where the food was stashed! Though coordinating someone making dinner in an instant pot for 7 people is...difficult.)

This was the first of two Crispin Freeman Q&A panels during the weekend. This one, titled, Why We Love This Stuff So Much, was focused more on anime and fandom in general. And @lechevaliermalfet stepped up to ask a question regarding Crispin’s work as Shannon in Scrapped Princess.

From there, we briefly wandered into Helen McCarthy’s panel on The Manga Beatles. I wish we had stayed with @shbumi to the end of it. It was interesting, although I admit that I was starting to tire a little from the day’s events. It was getting on toward 2100 when that panel started.

Being at a distance where I couldn’t fully really the slides + late hour (for me, because I have a job that requires me to keep stupid early hours usually) = tired @squeemcsquee. And we had to leave early to get into line for Anime Hell (though @shbumi stayed to panel’s end and actually got seated not too far from us, all things considered, even though she lined up wayyyy later).

The usual pre-show slide shenanigans were in play. And when the videos started...well, I have some odd searches and moments from group chat saved to my phone. For an example:

After the insanity that was Anime Hell, it was time to turn in. Day One ended on a high note. I also want to mention that Day One was also the day Pokemon Go released the new lure modules and Eevolutions, so I made sure to get a Leafeon and Glaceon ASAP. I even snagged shinies, since i’d saved some back from Eevee weekend!

All Anime Central 2019 coverage:

1. Day Zero Report

2. Day One Report (current post)

3. Day One Cosplayers, Part 1

4. Day One Cosplayers, Part 2

5. Day Two Report

6. Day Two Cosplayers, Part 1

7. Day Two Cosplayers, Part 2

8. Day Three Report

9. Day Three Cosplayers (current post)

1 note

·

View note

Text

cool cats (and dogs, too) | myg

⇒ summary: yoongi has one (1) dog, and he loves her very much. yoongi also has one (1) daughter, and she loves cats more than anything. sometimes apples fall pretty far from the tree.

⇒ {dad!au}

⇒ pairing: yoongi x female reader

⇒ word count: 2k

⇒ genre: fluff

⇒ warnings: animals?

⇒ a/n: for sir yoongi’s birthday! i had this idea in my head randomly and thought it would make a cute drabble. also shoutout to that Cool Cat™ in the banner. i’d die for him.

Yoongi loves his daughter more than anything else in the world, but the increasing amount of cat-themed artwork that is hanging around their tiny apartment right next to the heart of the city makes him feel like a traitor. At least Holly doesn’t know what the hell is on all of the things tacked to their refrigerator door, or she’d go into a fit.

People tell Yoongi that his daughter takes after him in many ways. She has the same gummy smile, accentuated by the empty space in her bottom teeth, the first of many. Or, she pouts the same way when she doesn’t get what she wants, an expression Yoongi finds himself weak to every time he is subjected to it. And she loves listening to music, always asks Yoongi to put on her favorite CD (Abbey Road by the Beatles) whenever they’re in the car. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree but his daughter has come so close to the roots that they’re practically the same person.

But the one thing that his daughter doesn’t take after him in? Animals.

Yoongi does not think he has seen a bigger cat-lover than his daughter, and it’s appalling. She has cat bedsheets, a cat backpack, cat-shaped pencil sharpeners and erasers. The walls of their flat are littered with cats drawn on lined notebook paper and little peel-off cat stickers (because Yoongi knows he is too lazy to try and scrape off real sticker remnants). Her bedroom floor is decorated with various stuffed cats, ranging from the smallest kittens to the fiercest lions.

And poor Holly is trapped in the middle of it, Yoongi’s faithful pup who does not understand the horror that is his daughter’s bedroom, can not comprehend what all of the pictures on the wallpaper mean. Holly is the second love of Yoongi’s life, the only other constant in his rocky existence.

It’s not that his daughter, Chorong, hates Holly, or anything. It’s just that every time he takes her into a pet store to pick up Holly’s food, she drags him to the cages where the cats are, ogles them and begs him to adopt one to take home (which Yoongi knows Holly would hate). And she’s constantly babbling about how Holly is so much work to take care of, and even at only five-years-old, she is already aware that cats don’t need to be potty-trained like people and dogs, and that they bathe themselves. And she tells him that Holly deserves a friend because it gets awfully lonely in their little home when she is at kindergarten and he’s at work, and a cat would be the perfect solution to the predicament.

Yoongi was already unprepared to the fullest extent when Chorong came along, stomping all over his previously delicately-laid-out life plans and decorating his life with color. Even five years later, he still thinks he is entirely unqualified to be taking care of a little human despite him trying his best. But this? This sends him back to square one, for nowhere in any of the twelve parenting books Yoongi owns does it detail what to do when your daughter is a cat person and you are a dog person.

Guess this one’s on him to figure out.

---

Yoongi regrets taking this detour after picking his daughter up from extended-day at kindergarten.

His work had dragged on longer than he anticipated, an occurrence he fears will start to become more common. He really hates leaving his daughter alone for so long—she is already beginning to realize that when he doesn’t come to pick her up at the normal time, she just needs to go to the classroom where extended-day is held without being told—and can’t bear the thought of her simply getting used to him not being around. Her mother had left when she was three days old, so Yoongi is all she has.

By the time he picked her up, the sidewalk that was once open for them to walk on as a shortcut to their apartment had been boarded up, metal fencing surrounding it and forcing the two of them to find another way home. Yoongi doesn’t know much about this city to begin with, so he is relying on only Siri to lead him home.

Chorong is happily blabbing on about the arts and crafts activity they did, where they got to decorate ladybugs with sequins and sparkles and glitter as part of their unit on insects. Chorong proudly declares that she is the only person in her class that isn’t afraid of spiders (“even the boys are too scared!”), another trait she got from her father who spent the entirety of his university years taking the spiders that haunted his shared apartment outside.

And then, as Yoongi is telling her that she is the bravest person he knows, she stops. Chorong has a habit of getting distracted fairly easily, yet another inherited characteristic, so Yoongi finds himself getting used to the abrupt pauses and stops as they walk around the city.

“Look, Daddy!”

Yoongi leans down so that he matches her little height, made littler by all of the things in this city that tower over her, and lets his eyes trace from her arm to her pointer finger. When he finally looks properly at what she’s staring at, his brows furrow.

“A cat café!” She cries excitedly, already clasping her fingers together in applause. Yoongi grimaces. “Daddy, can we go inside?” She begs, tugging on her father’s arm in desperation.

Yoongi knows that voice. It’s the voice that Yoongi always caves in to, always finds himself falling weak to, despite the stern tone in his voice as he attempts to tell his daughter “no”.

“Please?”

Yoongi is going to apologize to Holly until the universe collapses in on itself.

Chorong tugs him towards the door, standing on her tiptoes to reach for the handle. Yoongi makes to open the door for her but she pushes him off, already feisty even only at five years of age, wrenching open the door proudly as Yoongi places his hand on the frame to keep it open for her.

“Welcome to the Choco Kitty Cafe,” the woman at the front says, smiling happily at Chorong as she gazes around the quaint cafe. There’s cat memorabilia all over the place, decorating the walls and the floors and everything in between, and Yoongi swears he hears the faint meowing of cats from the next room over. “Just the two of you?” The woman asks, swiping away at the iPad in front of her.

“Yes,” Yoongi nods, already making the pull his wallet from his back pocket. Oh, the things he does for his daughter. He makes sure to keep a close eye on Chorong, knowing how she has a habit of disappearing from his line of sight in favor of something largely more interesting than her father.

“An hour?”

Yoongi looks down to his daughter, who is playing with the lucky cat on the table beside her, paw waving back and forth, back and forth, back and forth.

“Yes, an hour,” Yoongi says, and maybe he shouldn’t be wasting away his time surrounded by animals that are notorious for disliking him, maybe he should be working on some of the work he still has left for his boring day job, but the smile on Chorong’s face makes this all the more bearable.