#the fact that he was also a victim of slavery is so overlooked

Text

Unpopular opinion, If the story was told from Shen Jiu's perspective, svsss would be a horror and Shen Yuan the villain.

I mean, you're talking about someone who had little to no automony their entire childhood. Who was a slave and suffered unspeakable horrors at the hands of his master to the point of developing a fear of men. Who knows what it is like to have no control over your body or what happens to it.

So, to be not only kicked out of his body, but forced to watch as someone else occupies and uses it (arguably doing and becoming everything he was rumored to have been and done) would be viscerally horrific.

(This is why I firmly believe that YQY would take the Shen Yuan revelation badly. He was a slave too, and without a doubt, knows how much Shen Jiu valued his freedom and autonomy above everything else. He would be so horrified and devastated to learn that his Xiao Jiu was stripped of both again while he stood by and did nothing again.)

#idea dump#ramblings of a sleep deprived girl#scum villian self saving system#mxtx svsss#svsss#shen jiu#shen qingqiu#tw: slavery#tw: allusions to SA#I don't explicitly say it but I do imply it#unpopular opinion#transmigration is horror#especially when you're the person who has their body stolen#even more horrific when said person is heavily traumatized#yqy would not take the truth well at all#the fact that he was also a victim of slavery is so overlooked#so he also knows what it's like to have no automony#but that won't be the thing that horrfies him but rather that it happened to shen jiu again#while he was unable to do anything about it again#his not horrified for himself but because it happened to his Xiao Jiu

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Social Mobility

Obviously, there are a lot of problems with The Patriot's representation of slavery, but the fact that so many discussions of this center on Benjamin Martin overlooks an interesting possibility concerning this character. That Martin not only hires free men to work his land instead of using slave labor but also does heavy farm work himself is often read through a Doylian lens of making the hero more sympathetic to a modern audience. But what if we consider this choice through a Watsonian lens? What would that say about Martin?

First, he clearly does not hire free men to help him out of any moral distaste for the practice of slavery . If he felt that way, it is unlikely he would have married into a slave-owning family once, let alone twice. In the one moment where he does seem to support racial equality, his insistence that Occam sign for himself could be more about assuring the loyalty of this lone Black man who will be fighting alongside White volunteers. Perhaps, for the moment, Martin is stepping outside the White fantasyland of The Patriot where Black people simply do not escape from their enslavers when the opportunity arises. And maybe this reality is also behind Martin's choice to use free laborers for his own farm. Notice that not only he but also his sons play a role in planting, as we see when he asks Nathan and Samuel about the progress on their chores at the start of the movie. Most often, people parent in the ways they were parented, which raises an interesting possibility. Martin chose not to have slaves because he does not come from an enslaver family and has been used to doing his own labor, but now he has more land than he can manage himself even with the aid of four work-aged sons.

How on earth did this occur?

Well, it could have something to do with his being a war hero. That could also explain how a man who farmed his own land was able to marry into a family wealthy enough to afford slaves in the first place. Perhaps his marriage to Elizabeth was as much a reward for his wartime service as his marriage to Charlotte many years later. Women did not buy slaves for themselves in the colonial South, so Charlotte's are likely part of her inheritance from either her father or late husband (mentioned in some versions of the film/script, but not all). It would have been very unlikely for a woman to marry above her class, but a man could do so if he chose the right means of advancing himself. Looked at in this light, Martin's actions at Fort Wilderness, that made him a "hero" and for which he claims to feel such deep regret, gave him not only the land he owns but also the mother of his children, the gift that kept on giving (and giving and giving and . . .)

"I advance myself only through victory." "The honor is found in the ends, not the means." If my reading holds merit, these words from the villain's mouth actually describe the hero's trajectory far more accurately than Colonel Tavington's. As despicable as Tavington's actions are, he is only seeking upward mobility through tried and true methods, as Martin's experience attests. I've always found it funny that Tavington insists he can never return to England with honor but expresses no concerns that having committed war-time atrocities against Americans could impede his thriving in America. People in London for whom Tavington's victims are merely a newspaper headline will be appalled, but their flesh-and-blood Loyalist neighbors ? They'll get it!

Tavington's claim to his second James Wilkins that their burning a church filled with Patriot civilians will be forgotten is dubious at best. Most likely he knows better and is only saying that to ease Wilkins' conscience. But the reason such an action would live in infamy is not because it was particularly brutal by colonial standards. It's because the victims were White. The British Empire was a deeply White supremacist institution, and as movies like The Patriot show, that is a holdover from imperialism that we have yet to part ways with.

#the patriot#benjamin martin#chattel slavery#william tavington#social mobility#tldr Martin can still be a terrible person without having owned slaves

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently read The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda by Ishmael Reed, thinking I was going to do a writeup on it. Then totally forgot to do a review! So here are my thoughts:

It’s a really interesting piece. It’s less like a proper play and more like an essay in the form of a play. It would likely be somewhat boring to watch in a theatre, since a lot of the monologues are closer to lecture. However, I really like that Reed published it in play format. Essays about race and history and the failures of various history books are many, as are critical analyses of theatrical pieces. But meeting the medium with the same medium, writing a critical analysis of a play (or musical, as it were) in the form of a play, is a cool technique. Even if something doesn’t work perfectly in its medium, sometimes why that medium was chosen is important. Reed is famous for satire, and this is an interesting blend of genuine education and satire; the satire comes mostly in the form of the white historical figures talking about/to each other, and in the way he writes the present-day figures like Rob Chernow and Lin-Manuel Miranda himself, while the monologues of the Black and indigenous historical characters are mostly educational.

The most important overarching critique in this piece, I think, is that history books, especially those written by white people, are selective both in who they decide to portray and from what angle, and will very often omit or gloss over individuals or incidences that might paint their subject in poor light. Reed writes Miranda as a clueless victim of this type of selective omission, which I find to be an interesting choice. The Miranda portrayed in this play used only Chernow’s book as a source for the musical, which means that all the individuals Chernow omitted from his book are ignored in Hamilton, or any prejudices or angles expressed in the book exist in the musical. I don’t know if that was the case in real life, if Lin-Manuel Miranda did any further research to make sure he wasn’t overlooking important people or information, but I think it’s actually a rather kind portrayal. I would be a bit shocked if he did no other research, and no one around him during the process, whether it was producers or dramaturgs or someone else, did any other research either. So writing him as cluelessly using only the one book as a source rather than choosing to ignore other sources seems like a moment of niceness, or perhaps it’s intended to be something more like condescension.

The basic plot is that Lin-Manuel Miranda, stressed out and unable to sleep, is given an Ambien by his agent, and dreams various historical figures coming to him, A Christmas Carol-style, to inform him of all the facts Rob Chernow left out of his book about Hamilton’s relationship to slavery. This includes slaves, indigenous people, (white) indentured servants, and Harriet Tubman.

Most of the monologues are essentially Reed filling in the historical gaps while criticizing Miranda for ignoring the documented plight of enslaved people, indigenous people, and others. But I really like the way he does this; allowing the named and unnamed Black and indigenous historical figures to be portrayed by living actors also gives them a way to be embodied while their history is explained. That’s why I think the vehicle of theatre is very cool: the monologues are, essentially, mini history lessons on the people whose stories Chernow’s history book (and therefore the musical) has forgotten or omitted, but by making them into monologues it allows that person to “tell” their own story through the actor and therefore connect more to an audience, rather than a reader just consuming it on a page in a nonfiction book. There’s a big emotional connection, a pathos that comes across more easily when watching a person speak about their (or “their”) experiences than when reading it as text in a book.

The monologues themselves were actually very eye-opening and interesting; some characters were based on real, named individuals enslaved by the Hamiltons/Schuylers, their relatives, or others in their social circle, and their monologues both explained historical contexts and told their individual stories. Others are anonymous characters portraying indigenous or enslaved people, and their monologues are more general, expressing broader historical experiences. This was a good vehicle for covering bigger picture and more detailed parts of history, I think.

Much of the criticism is about the Schuyler sisters rather than Hamilton himself, and their abuse of people they enslaved. I think Reed focuses on this because the sisters are portrayed as innocent and sweet, and he wanted to emphasize how much that was not the case, and how much they treated human beings like commodities they didn’t care about. But even through the Schuyler sisters, Reed criticizes Hamilton, because he points out over and over that when the sisters wanted something done, the men had to be the ones to put it in motion, meaning Hamilton and the other men in the sisters’ lives were just as complicit in their treatment of the enslaved.

There’s a moment in the middle of the piece where the anonymous indigenous character and one of the anonymous enslaved characters start fighting over, essentially, who was more oppressed by the colonizers. Eventually they’re interrupted when another character points out that this “divide and conquer” strategy is used by imperialists to pit them against each other and that they should be working together to support liberation from oppressors. I thought this was a nice touch because, along with the educational monologues from each character, it emphasizes the importance of mutual support in the face of oppression, and shows that the colonizers wanted that kind of fighting because it was/is an effective way to prevent people from joining together to push back as one and therefore become stronger as a group.

There’s a fair amount of criticism of Miranda’s poor writing, too, and the clumsy and sometimes uncreative rhymes in his raps, which I also appreciated. Not only that, but there’s also an important criticism of how little the actors and crew in these productions get paid compared to producers, backers, and Miranda himself. There’s also criticism of the ticket prices, which I was very happy to see. I was always frustrated by the prices being so high that only people with quite a lot of disposable income (who more than likely were white, especially in major cities where the show tickets were higher) and who probably weren’t going to question any of the show’s content, were the ones who were going to see the show, rather than poorer BIPOC who might have been in the intended audience. (Although tbh I do think the intended audience was white people who wouldn’t care enough to criticize the show.)

In the play, Miranda does go through an emotional arc and redemption; in another dream, he speaks to Alexander Hamilton and realizes that Hamilton is a racist and a slave-owner and not as wholesome as he thought, and Hamilton praises him for scrubbing his image clean via the musical so people think he’s a hero. In the end of the play (which is also the most heavily satirical) he attempts to confront Chernow about his book, but Chernow dismisses him. Miranda is offered a chance to write a musical about Columbus in the same vein as Hamilton, and refuses.

I think this is a piece that would do well as a reading, or done in the style of (and this is the first theatre production that comes to my head, I’m sure there are others) Les Miserables 25th anniversary concert, in which there are no sets (or a very simple one), but the costumed characters stand to speak their lines in front of microphones at the apron of the stage.

I also think a massive criticism that was missing (but I think is a complaint specifically in the theatre fan community and maybe less obvious outside of it) is that Lin-Manuel Miranda could have and should have written a musical about a historical figure or figures who were BIPOC if he was trying to have a primarily non-white cast. The fact that there are *so many* Black historical figures whose lives would make incredible pieces of musical theatre was completely ignored by Miranda in favor writing a show with a non-white cast portraying and smoothing over the history of colonization. He could have written about so many BIPOC historical figures, or events in American history that don’t get enough attention in school. Larger productions with casts of primarily non-white actors are few and far between in mainstream theatre, and telling their historical stories even more rare, and I think Reed should have pointed that out as well.

Overall I really liked this piece, but I think I understand why others might not understand it, as it’s written in a medium that seems odd for its long-winded style. But I think it’s attempting to meet Miranda in a similar medium, and I think to some extent even the long-winded-ness (which is still full of really good history and critique) is sort of a tongue-in-cheek way of showing how difficult it is to portray history in a way that allows for a person or people’s whole story to be told, while simultaneously saying “Look, if you omit the negative aspects of a person’s history, you are failing those who lived and died in oppression by scrubbing the historical figure’s image clean.” Many people who went to see the musical didn’t go on to do more research on Alexander Hamilton and learn about the things that were left out of this portrayal of him as a go-getter, dream-chaser, heroic figure. And anyone who was on social media spaces like Tumblr during the height of the Hamilton craze remembers how many people suddenly treated these real historical figures like adorable fictional characters who were innocent of wrong-doing, who they could attach various characteristics to in the same way people do to fictional characters in fanfiction etc.

I definitely enjoyed this play, and I think while it’s closer to a multi-voiced history lecture than a proper story with a full arc, I think the medium of theatre is a very cool way to criticize Hamilton and Lin-Manuel Miranda, and I really love the combination of satire and genuine historical education. It fills important gaps, gives often overlooked details, and tells the stories of people who still remain ignored or nameless in history. It takes the white historical figures down a peg and gives narrative control to the Black and Indigenous characters. The sheer amount of words spoken by Black and indigenous characters compared to white ones is a pretty big ratio, and I think it’s a subtle but powerful way to give their stories the focus. The satirical end that portrays the racism of Hamilton himself and the selectiveness of Chernow’s book, and also has Lin-Manuel Miranda himself learning a lesson and attempting to redeem himself is also I think a good touch; it doesn’t allow anyone to bow out uncriticized, and it is an obvious attempt to encourage the real life Lin-Manuel Miranda to look at his choices compared to the historical evidence, and the things he could do or say to try and undo some of the damage the musical has done to the memory of the enslaved and oppressed.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“R:B” CHAPTER 4 (Part 1)

TRANSLATION & RAWS: NARU-KUN

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3: Part 1 / Part 2

Hot.

The body seems to burn.

The meat is roasted in the flames. The blood boils constantly.

Everything around his emitted heat. Everyone around his has pushed the heat. Tied, hampered and contained. Tied up and condensing the heat.

The heat inside was already unbearable. His brain was boiling and he even felt like it was melting. If he doesn’t let go immediately, he will go crazy. So he put that heat in his fist and hit it. For something that pushes the heat. To tie things up. By things that incline, hinder and contain. To everything that tries to tie it.

He will do his best to repel the tangible and intangible pressure that blocks him. The pressing heat turns into scorching heat and rejects it.

Just at that moment, the heat that escaped became a pleasant sensation and burned his nerves. The wave of heat shaking his discomfort, made the freedom of the moat shine.

It was comfortable.

So…

Hit it.

Smash it.

Penetrates.

Push it in and get out.

The unexpected joy of pleasure that was not his. There were many people around him who were delighted with liberation from slavery and wanted to be destroyed. There were those who had the same goal and those who had the same irritation. He took the initiative and exercised power. The companions screamed loudly, and the sound brought a new pleasant warmth.

Power went up. Even if he is hurt or painful, he is still the power to carry on. It is a power that never gives up, even if it is confusing and terrifying.

It is the warmth of life.

And now. It's hotter than ever. It is painful. Flesh burns, blood becomes irritated, and irritation fills the brain.

It's okay.

The "power" that stabbed the fangs, shaved the desires and shook ...

He tears it all down.

Everything was burned.

Those who rejoice together were erasing everything with their hands.

It is the desert that extends. The desert he once dreamed of.

Facing the vague but emotionless sight, the blood freezes, the core freezes, it's like this, he is different...

Suoh woke up to a chewing voice that did not sing or shadow. His entire body was drenched in sweat and he was making a violent pounding as if his heart was broken.

Like a bad cold that seems to upset the stomach and a severe attack of cancer in the limbs. Inhale the warm air of the place and scratch the moment between dreams and reality.

He looks around with unmistakable fear. It makes sure there was no evidence of destruction.

What there is the usual view. Nothing changes, the room on the first floor of the bar "HOMRA".

He was tense with all his nerves and confirmed it many times.

And finally he exhales.

Immediately after the fleeting relief, a sticky and suffocating heat completely enveloped Suoh's entire body.

++++++++++

He lit the cigarette for the moment.

Suoh puts smoke in his lungs while sitting on the bed. Then exhale everything from his body.

It seems there is still heat left in cells throughout the body. The center of his head is particularly terrible. Feel a sharp dull ache in the slight mud-like heat. Damn feeling, like poison in his chest, he smokes again.

When he closed his eyes, the scene from his dream was still on. The desert of destruction. What's hard to say is that while he avoids the scene, he thinks it's okay. As he understood the tragedy, he still had the sensitivity to feel the scene in a refreshing and liberating way.

There were no ties of any kind there. There was freedom.

Freedom based on his own power.

Damn. He frowned and stood up.

Looking out the window, the scorching sunlight still lights up the world. Suoh clicked his tongue, imagining a peaceful prison.

He put the cigarette in an ashtray and left the room.

Suoh is awake on the second floor of "HOMRA". He takes a shower and walks from the hall to the stairs. Faced with that, hear a voice below.

"No doubts?"

"Yes. Fushimi also confirmed it by another route."

Izumo Kusanagi's bitter voice. It was Totsuka who answered.

"Yes. I expected it, but as soon as I faced him, he ran away."

"Whatever. It's my responsibility."

"I do not care. I will carry it out. Somehow."

"I feel sorry for the mob people."

"That is his business."

When he heard about the mafia, he knew what it was. It's the conflict from the other day. Suoh makes a sound and goes downstairs while somehow observing the content of the conversation.

At the same time as the footsteps echoed, the conversation between the two stopped. Kusanagi and Totsuka turn their faces as he goes down to the first floor.

"King. Good Morning."

"Even though it's very hot, I can't sleep until this time."

Totsuka was unconcerned and Kusanagi spoke with a dismayed smile. They were both not serious until shortly before.

It is a pleasant and habitual attitude. Suoh shrugged and took his usual seat at the counter.

"And Anna?"

"She went shopping with Kamamoto."

Take control and light the cigarette. Kusanagi kindly handed him the ashtray.

He asked for a glass of water and drank about half of it at a time. Water, a mineral that floats on ice, slides through the body. The sensation made him feel a bit rested.

He probably won't want to hear it.

These two people should be able to see that his internal pressure has recently increased. He is sincerely grateful for the consideration that they do not want to put an extra burden on him.

But,

"...So?"

Suoh asks, smoking slowly and brushing off the ashes.

"Are you sure?"

Kusanagi arched an eyebrow and Totsuka looked up, and they looked at each other. Even if he feels like it just then, he thinks they are intimidating each other.

"What did you hear?"

"I just heard it. It seems to be the case with the last mafia."

"Yes, well... Actually, that conflict seems to have started with our newcomer."

"Did he get into a fight?"

"That's what I mean... Apparently, they blackmailed the drug business."

Suoh's eyes when he heard it became sharper.

"I see, it's disgusting because they just fill their mouths."

He dares to laugh ironically.

"I'm excited about my mafia opponent."

"Idiot. Your screws just fly away."

"Eh?"

"Yes. It started to cost me because they rejected me there, it seems that it was the result of an increasing escalation."

Totsuka half faintly replied.

Suoh and his friends attacked the last time because the members of "Homura" were attacked by the mafia. Retribution for the attack. And, in order not to cause more victims to the members, the battle was opened.

However, it seems that the cause was on "Homura's" side in the first place.

Of course, when it comes to the drug business in the Shizume-cho area, it cannot be overlooked. Eventually, a collision would have been inevitable.

"Rather, I'm glad you refused. It's hard to imagine 'Homura' would be one of the traffickers."

"Homura" is a group of so-called street gangs, but they have not dealt with illegal businesses.

Exceptionally, when troubleshooting Strains, the customer may be someone who is "the source", but the requests received are carefully screened. They have a line that should not be crossed as a team.

They have the meaning of self-discipline because they are a group with enormous power, but more than that, it will not be "a hobby" of Suoh and other executives.

However, there are some who are unhappy with him in the current "Homura".

"Even if Totsuka says 'harassment', while listening to something that never happened, it seems like other newcomers also exploded and got involved. They did various things, from funny pranks to stealing products. He must have been quick to sharpen there."

Kusanagi knew that there was a skirmish between a part of "Homura" and the mafia. However, shortly after hearing from the members and embarking on arbitration, the mess turned into a conflict.

There are also conditions like the fact that the opponent was a martial arts group, and that many of the members were foreigners and didn't know much about "Homura's" real situation. But still, if the lower limb hadn't anointed the fire, it would have been a bit smarter.

Suoh waved the cigarette with a distant look as he listened to the story.

The more he listened to it, the less it seemed to go down. A ridiculous and troublesome story. However, he wondered if he could say something about those people without laughing.

For example, how far would he have gone that night if Totsuka hadn't stopped him? For his own pleasure. Or to escape the pain of burning.

Bitter things come from the back of the body.

"What guys?"

"Do you remember Yamata, who received the installation three months ago?"

"Yes."

"It's a group focused on him, and now it's a group of seven or eight people."

Kusanagi said that and scratched his head in an annoyed manner.

With an old man's expression that is a mixture of deprivation and ideology.

“Well, it is a small article. It was a journey where a little smart kid was smart and mean. However, when the other party is the mafia and the kid is a walking flame radiator, it's not easy to drink."

He said bitterly with a serious voice.

"The most troublesome thing is that those smart guys don't do it. At the bottom, it's okay if it's so unreasonable. There's a lot of air, on the contrary, next time they'll go through more and more, and even if they move on with the current situation It usually will. As expected, it's too early."

While saying that, Kusanagi prepared a glass for him and poured water.

After putting it in his mouth and taking a breath...

"I really want you to be patient."

When, he laments exaggeratedly...

"Although "Scepter 4" is getting more active, our members are increasing the extra work."

"After all, if I'm keeping an eye out for newcomers..."

“That's why I said it before. I am only responsible for you."

By convention, Totsuka was supposed to take care of the newcomers in "Homura." But it's been months since that practice stopped working. As Fushimi has said many times, there are too many newcomers rather than Totsuka's negligence.

In progress…

23 notes

·

View notes

Link

Prostitution or sex work? Language matters

This article is by Laura Biggs, from the Marxist-Feminist blog On the Woman Question.

The term ‘sex work’ has come to replace the word ‘prostitution’ in contemporary discussions on the subject. This is not accidental. The phrase ‘sex work’ has been adopted by liberal feminists and powerful lobbyists in a deliberate attempt to steer the narrative on prostitution.

Smoke and Mirrors

Superficially, the term ‘sex work’ is intended to make prostitution sound more palatable. It is used to remove the negative connotations of the sex industry and those who work within it. However, sanitising the horror of prostitution with such benign terms is a monumental disservice to the tens of millions of prostituted women around the world. Their experiences cannot be celebrated as ‘work’. The vast majority of their experiences are dirty and degrading. What a handful of relatively privileged Western women working in the sex trade may deem to be ‘work’ is perceived as humiliation and degradation by millions of others. Some argue that the term ‘sex work’ removes the stigma and vitriol directed at prostituted women, but this fails to address the problem. Prostituted women are hurt and violated by buyers because the sex trade enables abusive men — not because of the language used to discuss it. Suggesting that the word ‘prostitution’ is to blame for the suffering of prostituted women shifts blame away from the perpetrators of male violence and overlooks the institutional systems which allow it to flourish. It is absolutely vital that we do talk about the ugly reality of prostitution, and to do so we must begin by naming the issue in no uncertain terms: prostitution.

Reinventing prostitution as ‘sex work’ also masks the deeply misogynistic nature of the sex trade. The word ‘prostitute’ is one which is heavily gendered; it connotes women. The Oxford English Dictionary acknowledges this in their definition of the word: A person, in particular a woman, who engages in sexual activity for payment. So gendered is the word, in fact, that when referring to men in the sex industry, the descriptor ‘male’ is added in order to make the distinction (male prostitute). This is not an outdated, sexist misconception but an accurate reflection of the gender balance within sex trade. The vast majority of those who are prostituted are women and girls while the vast majority of buyers and pimps are men. Obfuscating the gendered nature of prostitution by rebranding it as ‘sex work’ erases the millennia of misogynistic oppression inherent in the sex trade. It is likely that commercial prostitution (separate and distinct from temple prostitution) is derived from ancient slavery. The physicality of male slaves meant that they were often utilised for manual labour whilst female slaves were more likely to be reserved for domestic or entertainment purposes. In many Ancient societies, women could not own property and therefore slave masters were predominantly male. As a result, female slaves were often used for the sexual entertainment of their male owner. Slave owners frequently rented out their female slaves as prostitutes and even set up commercial brothels. Prostitution, born out of sexual slavery, has always disproportionately affected women belonging to lower socioeconomic classes. It is crucial to acknowledge the origin and history of prostitution in order to understand that it is not ‘work like any other’ but an industry built upon the oppression of poor women.

A Wide Umbrella

‘Sex work’ is a vague term which refers to people selling their own sexual labour or performance. This can therefore include any number of professions such as webcamming, stripping, hostessing, escorting etc. Whilst any profession which exists solely to sexualise women is objectively antifeminist, it is important that we acknowledge that prostitution is distinct from these other milder forms of objectification. Clearly, the experiences of a student flirting with strangers via webcam to top up their student loan differs greatly from those of a vulnerable sixteen year old girl, trafficked from Romania, walking the streets. The job description of a prostitute lists acts and risks which are not common to other jobs: risk of STIs; unwanted pregnancy; unprotected handling of bodily fluids; degrading, painful and even tortuous sex; vaginal and anal tears; high risk of PTSD — not to mention the significantly increased risk of rape, assault and murder. Even within the sex industry, the experiences of prostituted women are uniquely harrowing and so it is essential that we prioritise these women in legislation on prostitution reform. By grouping all sex-related professions under the wide umbrella of ‘sex work’, those in less dangerous and degrading jobs have now been given the authority to speak on behalf of prostituted women, thus silencing the most oppressed voices within the sex industry. Individuals whose experiences have little in common with those of prostitutes are spearheading movements whose aims will have a direct and adverse effect upon the safety and wellbeing of these vulnerable women. The wide scope of the term ‘sex work’ allows wealthy lobbyists to use compliant liberal women as the mouthpiece for their damaging narrative whilst simultaneously pushing the experiences of those who are worst affected by the sex trade into the background.

In some cases, the term ‘sex workers’ is so broad that it includes pimps. Borrowing the language of the labour movement, pro-decriminalisation lobbies brand themselves as ‘collectives’ or ‘unions’ and demand decriminalisation under the pretence of ‘worker’s rights’. Douglas Fox, of the International Union of Sex Workers, describes himself as a sex worker yet is the co-owner of the one of the largest escort agencies in the country. The agency’s website argues that pimps are ‘sex workers’ and Fox also shockingly states that ‘the fact that paedophiles produce and distribute and earn money from selling sex may make them sex workers’. Similarly, the Sex Workers’ Outreach Project USA was founded by Robyn Few, a self-proclaimed sex worker who has a conviction for conspiracy to promote interstate prostitution (pimping). Unionising prostitution legitimises an industry which causes untold suffering to millions of women around the world. It is absurd to allow pimps to join these unions alongside those who they abuse and exploit. No amount of ‘worker’s rights’ will ever make prostitution a safe or humane profession. An inherently unethical system cannot be fixed through reform. A radical solution is needed: abolition.

An Appeal to Socialists

Describing prostitution as ‘work’ and its victims as ‘workers’ is a cheap and transparent appeal to socialists. Using Marxist jargon to describe prostitution as ‘work like any other’ is an insult to history’s great communists who condemned prostitution as counter-revolutionary. Under Mao, whose policy of criminalising pimps was implemented as soon as he took power, prostitution was virtually nonexistent. Engels himself asserted that communism would ‘transform the relations between sexes into entirely personal relations’. Therefore, any economic relationship between man and woman, particularly the grossly exploitative one between prostituted women and buyers, is inherently anti-communist. Lenin, too, commented that ‘so long as wage-slavery exists, inevitably prostitution too will exist’, demonstrating that he also believed prostitution to be inextricably bound to capitalist exploitation.

However, a significant portion of the woke left insist upon misinterpreting and misapplying Marxist theory to legitimise the continuance of the sex trade. They claim that by declaring prostitution to be ‘a specific expression of the general prostitution of the labourer’, Marx understood the position of prostituted women to be identical to that of all exploited workers. However, this wilfully overlooks Marx’s use of the word ‘specific’. In reality, Marx is suggesting that, whilst prostitution falls under the general banner of exploitation, its reliance on the oppression of women differentiates it from the ‘general prostitution of the labourer’ and makes it ‘specific’ to the female condition. If capitalist exploitation were removed, labour would continue to be necessary for the subsistence of any given society. In contrast, prostitution without capitalist exploitation ceases to exist; sex, devoid of economic coercion, would become a purely interpersonal relationship. In Private Property and Communism, Marx goes on to say that communism aims ‘to do away with the status of women as mere instruments of production’. Pro-prostitution arguments which characterise prostitution as ‘work’ inherently reinforce the perception of female bodies as machines which produce a commodity (sex) for male consumption. The objectification of female bodies, whether exploitative or not, is plainly incorrect and so cannot be supported by any Marxist movement.

There’s More to it Than Money

Framing prostitution as ‘work’ deliberately reduces it to a purely economic analysis. Any analysis devoid of historical materialism is wholly inadequate and will invariably fail to offer a comprehensive examination of the issue. It is vital to acknowledge the social factors which lead women into prostitution: low self esteem, childhood sexual trauma, incest etc. It is unsurprising that some of these vulnerable women embrace the ‘sex work is empowering’ narrative. Language which clouds the abject reality of their situation is undoubtedly appealing and so it is all the more immoral and manipulative for pimps, traffickers and lobbyists to push this sinister doublespeak. The insistent claim from liberal feminists that prostitution is merely ‘sex work’ does not recognise the existence of the social factors which predispose women to sell sex and so naturally prevents positive change to combat them. Prostitution, therefore, is much more than capitalist wage slavery and so we must reject any attempts to render it mere ‘work’.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

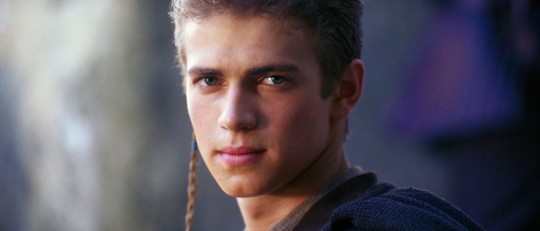

In Defense of Anakin Skywalker (and Hayden Christensen)

I grew up with Star Wars, my whole family loves Star Wars. I was 8 when I saw Episode I and afterwards, I was completely immersed in the Star Wars universe. Ewan McGregor's Obi-Wan Kenobi was probably my first fictional boyfriend and I'm unashamedly still in love with him too.

Episode II: The Attack of the Clones came out when I was 11 and so naturally I was excited to see the continuation of the Star Wars prequel universe. However, nothing could have prepared me for the absolute utter gorgeousness of Canadian actor, Hayden Christensen who was cast to play the adolescent Anakin Skywalker.

My memories of first seeing Episode II are fond because I got to see the movies with my older siblings while on vacation in Myrtle Beach. It was probably my first experience of being accepted among my older adult brothers and sisters or the feeling of 'grownupness' as I like to call it.

So Attack of the Clones has always been an special film to me because I saw it at a time when I was no longer being viewed as a child, but as a growing teenager.

It's also why I've always been rather defensive of the film too. While the film was titled Attack of the Clones, it may as well have been re-titled, "Attack of Anakin Skywalker (and subsequently, Hayden Christensen)". For over 20 years, there has been an absolute and indescribable hatred of Anakin Skywalker and many people blamed both Jake Lloyd and Hayden Christensen's supposed poor acting as the result of a badly done Anakin.

And to be honest even though I had a massive crush on Hayden Christensen and was hardly a movie critic at the time, I felt that at times that Anakin could have been better acted. However, I was young and didn't care about the script or the acting. Yet, for years I constantly defended, Attack of the Clones, Anakin Skywalker and Hayden Christensen. Partly due to nostalgia, partly to being a teenage girl and most of all partly to do with understanding the character of Anakin as being misunderstood, misinterpreted and not being treated as an adult by the elders in his life.

Did Anakin have problems? Yes.

Were most of these problems his fault? No.

Did Anakin ever try to fix these problems and better himself? Everyday of his life.

He had nothing, but he gave everything

The prequels were written as a timeline of a boy's journey from goodness into darkness. Anakin's life is a story arch of sacrifice and redemption. Life has not always been good to Anakin. He was born a slave with no father. He was raised in the strong love of wonderful mother Shmi Skywalker. While Shmi may have been scared and confused as to how she conceived a child without a man, she raised her son in love and simple contentment.

Chances are Anakin and his mother probably faced terrible abuse in their time as slaves and more than once, Anakin may have been separated from Shmi as leverage for greedy slave owners. Although a slave, Anakin was never a victim. He may have been physically owned, but his heart and mind were free. He was his own person, always thinking outside of the box, building, creating, questioning everything and everyone. Not to mention a little wild and rather reckless.

Even as a child Anakin was a little strange to people. For a slave to have such a hopeful and positive attitude may have seemed bizarre to outsiders, but that was just the norm for him. Shmi once remarked that her son knew nothing of greed. For a boy raised with nothing, all he had were his talents as an inventor and growing pilot. And he used his talents for other people. He built C-3PO to help his mom, he entered the podrace to help Qui-Gon Jinn, he always gave without any expectation of being thanked.

A spirit that refused to surrender

After Anakin is freed and sent to train as a Jedi, that wild spirit was still intact. Much to his by-the-book master's dismay. Anakin didn't have the opportunity to grow up in the strict Jedi Temple that was built on order, rules and tradition. As a child, Anakin was use to being himself and not fitting into anyone's mold. His original dream was to be a pilot, not a Jedi. No one asked him if he wanted to be a Jedi, no one asked him if he wanted to be trained by Obi-Wan Kenobi.

While Anakin may have been grateful for both opportunities presented to him, overtime he may have seen this new life as not to different from the one he left. A life run by others. Telling him what to do, where to go, how to dress, how to behave. He survived as a slave because he dared to dream and imagine and refused to be defined by others.

Now he's thrown into a culture where individuality is looked down upon. He lived through the stifling Jedi order because he still held onto those qualities. He was going to be himself on his terms. He would nod his head and say yes when he needed to, but off the clock he would live by his own rules. Something that Obi-Wan and the Jedi order could not understand. And Anakin is getting frustrated by this.

So now we get to Attack of the Clones (and the Attack of Hayden Christensen). Critics came down hard on both Anakin and Hayden. Constantly complaining about Anakin's constant complaining, his tantrums, broodiness and being a crybaby about everything. Critics blamed the disaster of Anakin Skywalker on the terrible miscasting of Hayden Christensen. The only redeeming quality Hayden Christensen had that saved him was the fact he was so easy to look at.

For years, fans were desperate to know who Anakin Skywalker was. And so the pressure to deliver a good character that could measure up to the icon of Darth Vader may have seemed insurmountable. And so when people got this confused, overemotional 19 year old, who has no experience in love or sex, but is madly in love with a beautiful young women; and who wants to be respected in a highly established culture, without losing himself or conforming, well people were just disappointed. The disappointment can be explained in one of Anakin's most famous lines.

"HE'S HOLDING ME BACK!"

He, being George Lucas who was holding back Hayden's actual talent to create a good three dimensional character. Plus his bad script writing. Poor Hayden was just made to read lines on a page and somehow make this sad character somebody that people can root for. Unfortunately fans and critics ate him alive. It's only in recent years that people have begun to realize that they were blaming the wrong person. And by blaming Hayden, they were completely misunderstanding Anakin as a character.

His most beautiful gift, his most fatal flaw

Of all of Anakin's gifts, his ability to love deeply was probably his most profound and his most dangerous. The Jedi Temple forbade romantic attachments to others and for good reason. When you become attached to or love someone beyond the boundaries of platonic friendship you become afraid of losing them. The end of my review for the Star Wars prequels sums it up the best:

In The Phantom Menace, Yoda warns Anakin about the dangers of being afraid. Fear leads to anger, anger leads to hate, hate leads to suffering. Anakin's most beautiful attribute is also his most fatal flaw. His ability to love deeply. Yet, if you love someone you will always live in fear of losing them. Anakin was created by darkness, but raised in the light of his mother's love. His own love was made manifest by Padme and then by their unborn child/children.

However, Love no matter how strong can be weakened and even be destroyed by the evil of fear. If the prequels taught anything about life, it taught how fear (even in its smallest form) can be be our most detrimental enemy. Living alone in fear and not seeking help is a signing of our own death warrants. What might have happened if Anakin had gone to Obi-Wan and seek his help? Would things have been different?

The prequels were not meant to tell a happy story. They were written as a timeline of a boy's journey from goodness into darkness. No, they don't have the silliness or humor of the Originals, because there is nothing humorous about someone's self-destruction. Yet, the story of Anakin Skywalker's transformation had to be told in a way that was real and heartbreaking.

To take Darth Vader and make him a human who could feel and understand and love could be an insurmountable task. Yet, you only need to watch his death scene at the end of Return of The Jedi to see that the humane part of Anakin Skywalker had always been there. The prequels were made to be built on that final scene of redemption and human love. A husband's love to save his wife became a father's love that could overcome darkness and hate. An extreme love that defied fear and held on to hope. That was the love of Anakin Skywalker.

Anakin could be a bratty and immature young adult. However, to only base a character by his few annoying flaws is overlooking the bigger and better picture. Anakin was an outsider his whole life and yet that never seemed to bother him. He never cared about fitting in. He was content being himself and he refused to let Obi-Wan or the Jedi Order or even Padme change him. He held onto who he was for as long as he was able to. Then the tragedy of losing his wife changed that. The indomitable spirit wasn't broken, it was destroyed. Anakin re-entered a life of slavery for over 20 years.

And he was ultimately freed by one person. An orphan who once had nothing but a talent as an inventor and dreams of being a pilot. A young Jedi with an unbreakable spirit that refused to surrender to evil or fear or pain or loss. A son who loved his father so deeply that he would fight to the death to free Anakin Skywalker forever.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

African Participation in the Slave Trade -- The Myths

History can be written from three perspectives: from that of the victor, a neutral observer and that of the vanquished. Much of Africa’s history was written by the colonialists (the victors) and obviously the victims of colonialism see things differently. For example, seeing no boxes with “ballots” written on them or a building with “Parliament” written on it, many European colonialists jumped to the conclusion that Africans were laboring under horrible and despot chiefs. Therefore, colonialism was good for the Africans because it liberated them from their terrible rulers. This was one monumental nonsense.

True, there were no boxes with ballots written on them and no building with Parliament written on it but that did not mean the essence of democratic governance was unknown. That mythology was as nonsensical as the claim that since there were no hamburgers in the village, Africans did not eat.

That mythology originated from their failure to make a distinction between the existence of an institution and different forms of the same institution. There are different types of food. The absence of one type – hamburgers – does not mean a complete absence of other types of food. Similarly, there are different types of democracy. Democratic decisions can be taken by majority vote or by consensus. In traditional Africa, decision-making is by consensus. The absence of voting did not mean Africans were living under terrible despotic Chiefs.

There are many other myths about Africa – in particular, African participation in the slave trade. Written from the African perspective, we seek to demolish the following myths.

MYTH No. 1: Africans were selling themselves off into slavery before the Europeans arrived on the continent. African chiefs were selling off their own kind into slavery.

It is true there was slavery in Africa but not the inhumane chattel variety. Slaves in Africa enjoyed certain rights and privileges. Generally, there were no slave markets in black Africa because of the value black Africans place on humanity. More importantly, Africans generally did not have demands for large amounts of labor. Even if they did, they could turn to their clans or extended families.The slave markets that were in Africa, according to historians, were in North Africa (or Arab North Africa) - in such places as Fez and Tripoli.

Slaves generally were principally war captives from inter-tribal warfare. Say there was a war between two neighboring tribes – the Ashanti and the Fante – and 5,000 Fantes were taken prisoner. The Ashanti King had the following options:

1. Keep the 5,000 Fantes in prison, which meant he would have to feed, clothe and shelter them - an expensive economic proposition;

2. Execute them, a very inhumane prospect; or

3. Sell them off as slaves and use the proceeds to purchase weapons to defend his Ashanti people;

4. Absorb and integrate the war captives into Ashanti society, a long, arduous and dangerous process since safeguards must be put in place to ensure that former combatants would pledge allegiance to a new society and authority.

Which option do you think the Ashanti King would take? If you said the third option, you are right because it was the most humane and economically expedient. The Ashanti also chose option 4, absorbed former war captives (slaves) into their society. To make their integration into Ashanti society as smooth as possible, even the Ashanti King was forbidden to disclose the slave origins of any of his subjects. He would be DETHRONED or removed from office if he did so.

Now, the more important issue is this. YES, the Ashanti King did sell Fante prisoners of war as SLAVES and therefore participated in the slave trade. BUT the Ashanti King did NOT sell his own kind/people - an important distinction. It was the Europeans who failed to make this distinction, which has been the source of much mythology about the slave trade.

The Europeans made no distinction between the Ashanti King and the Fante slaves. To the Europeans, it was a BLACK African King selling BLACK Africans. Therefore, Black kings and chiefs were selling their own kind or people. Nonsense. To the Ashanti King, the Fantes were NOT his people but rather the Ashanti.

Recall that about that time in history, medieval Europe was also fighting tribal wars - between the Flemish, French and the Germans. They were also enslaving one another. But you don’t hear the expression, “The Europeans were enslaving their own kind?” do you? Rather, you read of Germans taking French slaves and vice versa. So make the same distinctions in Africa - The Ashanti King taking Fante slaves, etc.

The real purpose of that mythology was to whitewash European participation in the slave trade. After all, African chiefs and kings were enslaving their own kind, so it wasn’t that bad for Europeans to do so.

MYTH NO.2. “African chiefs just went to the market and just grabbed their people to sell off as slaves.”

You often hear this from African Americans but it is not true for four reasons. First, no African chief can do this and expect to remain chief. He would be removed. As chief, his prerogative is the survival of his tribe. Second, he would be committing an ethnic suicide if he were to sell off his own Ashanti people into slavery. Third, it did not make military sense. He would be depopulating and weakening his own tribe to the benefit of a stronger neighboring tribe. Fourth, their clans would rise up to protect the victims. More importantly, there were traditional injunctions against that. To test this, go to Onitsha market, grab and beat up .Hausa market trader. The entire Hausa ethnic group would go to his/her defense. In fact, many tribal wars started precisely this way – from a dispute or conflict between two individuals. Furthermore, the Ashanti King’s or chief’s role is to minimize any external threat to his people. And if this means depopulating or selling off the entire Fante tribe into slavery he would do so and the better off his Ashanti people would be as that would mean less competition for resources. Yes, he would sell Fantes into slavery but not his own Ashanti people – an important distinction.

MYTH No. 3. “Africans are brothers and sisters and it is treacherous for them to participate in the slave trade.”

Again, tribal or ethnic distinctions are important in Africa. To think that Africans consider members of another tribe as “brothers and sisters” is totally ridiculous – an exercise in grand delusion. Why would a Hutus in Rwanda slaughter more than 800,000 Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994? Or tell the Igbo that the Hausa are their brothers and sisters in 1967.

Before the twentieth century, many societies in the world practiced some form of slavery. Prisoners of war, political opponents and religious dissidents were often enslaved in Old England. For example, in 1530, in England, under the reign of Henry VIII, a vagrant picked up for the second time was whipped and had half an ear cut off; taken for a third time, he was “to be executed as a hardened criminal and enemy of the common weal” (Marx, 1915; p.806). Seventy-two thousand vagrants were thus executed during that reign. In the time of Edward VI (1547), “if anyone refused to work, he shall be condemned as a slave to the person who denounced him as an idler” (Marx, 1915; p.806). The owner of such a slave might whip him, chain him, and brand him on the cheek and forehead with a letter “S” (for Slave), if he disappeared for two weeks. If he ran away a third time he was executed. An idler vagabond caught on the highway was branded on the chest with a “V” (for vagrant). The same laws were in effect during the reigns of Elizabeth (1572) and of Louis XVI in France. The supporters of Monmouth’s rebellion in England were sold by the Queen. Cromwell’s Irish and Scottish prisoners were sold to the West Indies and non Muslims who opposed the Sokoto jihad were sold to North Africa.

Criminals in Europe and Africa could be executed, transported or sold. Europeans favored execution; Africans favored sale.

“In the eighteenth century there were 300 different offences in Britain for which one could be executed. In Dahomey, there were only two, for the king preferred to sell rather than execute his troublemakers. Those who could not pay their debts were sold for life or until the debt was paid. Among the Yoruba, debt slaves (pawns) were called Iwofa, among the Asante Awowa, and among the Europeans indentured servants. About a quarter of a million white debt slaves entered America before the nineteenth century” (Boahen and Webster, 1970; p.69).

In pre colonial Africa, social conditions were such that,

“All the white minorities living in Africa might own Black slaves, but slaves and white masters alike were all subjects of a Black Emperor: they were all under the same African political power. No historian worth his salt can permit the obscuring of this politico social context, so that only the one fact of Black slavery emerges from it” (Diop, 1987; p.92).

There was, however, an important distinction between the slave/master relationship in Africa and that in Europe between serf/lord, which is often overlooked. In Africa, slavery was more of a social distinction without economic consequence than fact. The African slave, “instead of being deprived of the fruits of his labor, as was the case with the artisan or the serf of the Middle Ages, could, on the contrary, add to it wealth given him by the `lord’” (Diop, 1987: p.2). Slaves of the kings of Mali and the Askias of Gao “enjoyed complete liberty of movement. Thus an ordinary slave of Askia Daud, a native of Kanta, was able to carry out a pilgrimage to Mecca without his master’s knowledge” (Diop, 1987; p.153).

To avoid the ugly connotations associated with commercial slaving, Vaughan (1986) suggested the use of limbry: “Existing data, albeit tenuous, suggest that about 80 percent of African societies had limbry” (p.174). In contrast to commercial slavery, African “limbries” “were not on the whole mistreated, dehumanized or exploited” (Vaughan, 1986; p.174).

The privileges accorded them, however, varied from tribe to tribe. In Nigeria, the treatment of slaves was by no means harsh; nor was their lot deplorable. The majority were integrated into the society and the respective families of their owners in order to retain their loyalty, prevent rebellion and get the best out of them (Falola, 1985; p.99). The slaves were free to some extent; they could intermarry among themselves, own property and redeem themselves if they had the means.

Among the Lobi of Gabon, slaves were considered as “new children.” The Massangou of the Chaillou Hills in Gabon, incorporated slaves (war captives) into the entire community to replace those lost in war. In Dahomey, the children of slaves were free people incorporated into the master’s family with all the rights except the right to inherit political leadership (Simiyu, 1988; p.59). But in Senegal, slaves (djem) were closely associated to power. They were represented in royal courts and many became de facto ministers (Diop, 1987:2).

More importantly, Boahen and Webster (1970) pointed out that:

“Slaves had many privileges in African kingdoms. In Asante, Oyo and Bornu, they held important offices in the bureaucracy, serving as the Alafin’s Ilari in the subject towns of Oyo, as controller of the treasury in Asante, and as Waziri and army commanders in Bornu. Al Hajj Umar made a slave emir of Nioro, one of the most important of the emirates of the Tokolor empire, and in the Niger Delta states slaves rose to become heads of Houses, positions next in rank to the king. Jaja, who had once been the lowest kind of slave, became the most respected king in the delta, and was no exception; one of the Alaketus of Ketu, and Rabeh of Bornu, rose from slave to king (p.69).

Since slaves faced few barriers to occupational mobility or economic advancement, there was hardly any need for a tumultuous social revolution, such as the French Revolution in which the exploited overthrew their lords. Slavery, of course, was never under any circumstances an ideal institution and there were cases of slave revolts. One example was the revolt under Afonja in the Oyo empire. Another was the Koranko revolt in 1838 against the Susu of Sierra Leone. Led by Bilale, the Koranko ex slaves built a fortified town to offer freedom to runaway slaves. In Calabar, the slaves united in an organization called the Blood Men, and forced the freeborn to respect their human rights (Boahen and Webster, 1970; p.70).

MYTH NO. 4: The Europeans were the ones who introduced chattel slavery into Africa.

In pre-colonial Africa, the Europeans and Arabs were battling each other to subjugate Africa. By the 17th century, North Africa, inhabited by the Berbers, was already under Islamic conquest. For centuries, the Berbers have fought – and are still today – fighting Arab imperialism in Morocco and Algeria, where Arab names, religion and culture are being forced upon them. The Berbers had their own language, music and culture until the region was effectively Arabized as Islam spread hundreds of years ago. According to the Amazigh (Berber) Cultural Association in America, a Moroccan law, enacted in Nov 1996 and referred to as Dahir No. 1.96.97, “imposes Arabic names on an entire citizenry more than half of which is not Arabic”. The Berbers in Algeria, too, are up in arms. Fed up with years of discrimination and persecution at the hands of the Arab majority, Berbers, who make up 20 percent of Algeria’s 32 million people, seek more autonomy in the eastern region of Kabylie. They were the original inhabitants of North Africa when invading Arabs introduced Islam. Old tensions erupted into violence after a Berber schoolboy died in police custody in April 2001. Street clashes in Kabylia between the police and Berber militants left more than 100 protesters dead. "The Berbers also want the government’s police force, which they accuse of being partisan, to withdraw from Kabylie, and they want their language, Tamazight, to be recognized as an official language” (The New York Times, June 30, 2003; p.A4).

West Africa was saved from Islamic conquest by the Sahara, which served as an effective bulwark against Islamic expansionism. In East Africa, Islam made inroads in the 17th century – peacefully at first but with diabolical intentions at a later state. While the Europeans organized the West African slave trade, the Arabs managed the East African and trans-Saharan counterparts. For the trans-Saharan slave trade, an estimated 9 million captives were shipped to slave markets in Fez, Marrakesh (Morocco); Constantine (Algeria); Tunis (Tunisia), Fezzan, Tripoli (Libya); and Cairo (Egypt). No black African will ever forget that in the 19th century, over 2 million black slaves were shipped from East Africa to Arabia, a slave trade operated by Arabs.

The Zanzibar slave trade, with an annual sale that increased according to some estimates from 10,000 slaves in the early 19th century to between 40,000 and 45,000 in the mid‑19th century, was at its height during the rule of Sayyid Said (1804‑1856 ‑ born 1794), sultan of Muscat and Oman…

Enslaving and slave trading in East Africa were peculiarly savage in a traffic notable for its barbarity. Villages were burnt, the unfit villagers massacred. The enslaved were yoked together, several hundreds in a caravan, and on their journey to the coast, which could be as long as 1280 kilometres…It is estimated that only one in five of those captured in the interior reached Zanzibar. The slave trade seems to have been more catastrophic in East Africa than in West Africa (Wickins, 1981; p.184).

Diseases such as smallpox and cholera, introduced by marauding Arab caravans penetrating the interior in search of slaves, decimated entire local populations and were far more devastating than the actual export of slaves to Indian Ocean markets. According to Gordon (1989),

“One particularly brutal practice was the mutilation of young African boys, sometimes no more than 9 or ten years old, to create eunuchs, who brought a higher price in the slave markets of the Middle East. Slave traders often created “eunuch stations” along the major African slave routes where the necessary surgery was performed in unsanitary conditions. Only one out of every 10 boys subjected to the mutilation actually survived the surgery.

The taking of slaves – in razzias, or raids, on peaceful African villages – also had a high casualty rate. The typical practice was to conduct a pre-dawn raid on an unsuspecting village and kill off as many of the men and older women as possible. Young women and children were then abducted as the preferred “booty” for the raiders.

Young women were targeted because of their value as concubines or sex slaves in markets. “The most common and enduring purpose for acquiring slaves in the Arab world was to exploit them for sexual purposes. These women were nothing less than sexual objects who, with some limitations, were expected to make themselves available to their owners…Islamic law catered to the sexual interests of a man by allowing him to take as many as four wives at one time and to have as many concubines as his purse allowed. Young women and girls were often inspected before purchase in private areas of the slave market by the prospective buyer (p.35).

Some of the African slaves were shipped to Iraq, where they were inhumanely treated. In the latter part of the 19th century, they revolted and were subsequently placed in the Iraqi army. According to Walusako Mwalilino, a Malawian historian, “From 1859 to 1872, between 20,000 and 25,000 slaves were shipped to southwest Asian ports” (The Washington Times, Sept 21, 1995; p.A14). But the Arab slave trade continued well into the 20th century. According to Thomas Cantwell, an American reporter, “the last interdicted slave ship was in 1947, a dhow from Mombasa” (The Washington Post, June 4, 1994; p.A18). American reporter, Timothy Williams, claimed that,

“Officially, Iraq is a colorblind society that in the tradition of Prophet Muhammad treats black people with equality and respect. But on the packed dirt streets of Zubayr, Iraq’s scaled-down version of Harlem, African-Iraqis talk of discrimination so steeped in Iraqi culture that they are commonly referred to as “abd” — slave in Arabic — prohibited from interracial marriage and denied even menial jobs.

Historians say that most African-Iraqis arrived as slaves from East Africa as part of the Arab slave trade starting about 1,400 years ago. They worked in southern Iraq’s salt marshes and sugar cane fields.

Though slavery — which in Iraq included Arabs as well as Africans — was banned in the 1920s, it continued until the 1950s, African-Iraqis say.

Recently, they have begun to campaign for recognition as a minority population, which would grant them the same benefits as Christians, including reserved seats in Parliament.

“Black people here are living in fear,” said Jalal Dhiyab Thijeel, an advocate for the country’s estimated 1.2 million African-Iraqis. “We want to end that” (The New York Times, Dec 2, 2009; p.A22).

The official Libyan and Arab line on slavery is that: “The Arab countries are a natural extension to the African continent. The African Arabs, or those who carried the indulgent message of Islam, were the first to effectively oppose slavery as inhumane and unnatural. The claim that Arabs were involved in the trade at all is a mischievous invention of the West, made in order to divide the Arabs from their brothers and sisters who live in the African continent” (New Africa, Nov 1984; p.12). Nonsense.

During the black struggle for civil rights in the United States and independence in Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, Afro-Arab differences and ill-feelings were buried. Black leaders, seduced by the fallacious premise that “the enemy of my enemy must be my friend”, made common cause with the Arabs. In the United States, many blacks dropped their "European” or “slave” names and adopted Islamic ones. In Africa, black leaders entered into alliances and sought support from Arab states for the liberation struggle against Western colonialism. Grand Afro-Arab solidarity accords were pompously announced. Drooling, grandiloquent speeches announced meretricious Afro-Arab summits. Little came out of them, and since independence, black Africans have gradually realized that the Arabs regard them “expendable”. The Arabs are just as ready as the French to use them as pawns to achieve their chimerical geopolitical schemes and global religious imperialism/domination.

Today Africa has found new suitors – Chinese.

REFERENCES

Ayittey, George B.N. (2006). Indigenous African Institutions. Dobbs Ferry, NY: Transnational Publishers.

Boahen, A.A. and J.B. Webster. History of West Africa. New York: Praeger, 1970.

Diop Cheikh Anta. Pre‑colonial Black Africa. Westport: Lawrence Hill & Company, 1987.

Falola, Toyin. "Nigeria’s Indigenous Economy.” in Nigerian History and Culture. ed. Olaniyan, 1985.

Gordon, Murray (1989). Slavery in the Arab World. New York, NY: New Amsterdam Books.

Martin, Phyllis M and Partrick O'Meara eds. Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Chicago: Kerr, 1915.

Simiyu, V.G. “The Democratic Myth in The African Traditional Societies,” in Democratic Theory and Practice in Africa. eds. Walter O. Oyugi et. al. Portsmouth, NH: 1988.

Vaughan, James H. “Population and Social Organization,” in Martin and O'Meara, 1986.

Wickins, Peter (1981). An Economic History of Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

George B.N. Ayittey, PhD

Retired Distinguished Economist at American University and President of the Free Africa Foundation, both in Washington DC, USA.

Free Africa Foundation website www.freeafrica.org

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Guns In America: Full Mental Jacket

America loves its guns. It loves them so much, it is willing to overlook the damage they inflict on individuals, families, and society. It loves guns so much, it denies evidence from around the world that supports the conclusion that fewer guns = fewer gun-related injuries and deaths. It loves guns so much, it eagerly looks for ways to make them more dangerous, more lethal, more accessible. It loves guns because, in spite of being the world's superpower, its past and present have been steeped in insecurity, fear, and a false sense of superiority. Schools shootings are a microcosm of the problem of guns in America-A dangerous weapon in the hands of insecure, angry, testosterone-riddled, white males whose brains and moral compasses are at best not yet fully developed and at worst, seriously and permanently fucked up.

The problem with guns in America isn't that there aren't enough of them. The problem isn't “God has been taken out of schools and society.” The problem isn't immigrants, minorities, or Muslims. The problem is mental health-the mental health of white, male America. To be more specific, the problem is, and always has been white supremacy. If you don't understand the role white supremacy has and does play in how America views and loves it guns, you are part of the problem. This includes a lot of “good guy” gun owners who provide cover for their not-so-good guy gun-owning brethren.

The common thread from the first European white settlers to a large number of current gun owners in America is white supremacy. The first white men on this continent used guns to steal land, resources, and life from the Native Americans. The 2nd Amendment was written, in part, to ratify slavery. It was important for guns to be readily available for whites to keep slaves in line, to be able to fend off any slave rebellion, to protect their women from “violent, sex-crazed” black men. When slavery was abolished, the heavily armed Klan came to power to ensure white rule and supremacy was maintained. The Mulford Act in California was passed in 1967 and signed by then-governor, Ronald Regan, repealing open carry in response to members of the Black Panthers carrying guns while they patrolled the streets of Oakland to make sure the police did their jobs properly. Gun sales went through the roof when the first black president was elected. Right-wing media pushes gun ownership with threats of marauding bands of Mexican gangs, Muslim terrorists, race wars, and imaginary government operations that will imprison God-fearing, gun-owning, PBR-drinking, tobacco chewing, white Americans.

The fact that America has 5% of the world's population and almost 50% of the world's guns isn't by mistake, isn't to protect it from foreign powers, isn't to defend itself from its own government. America has the most guns because it was built on white supremacy. Guns were the tools used to take the land from its native inhabitants. Guns were the tools used to keep the economic resource of slavery in line. Guns were used against fellow countrymen in order to maintain the right to own other people. Guns were used to inflict fear, harm, and death in order to preserve and enforce Jim Crow Laws. White supremacy doesn't carry as much power without means and threat to commit violence. Guns and racism in America go together like Dylann Roof and a Glock .45, like Mom and apple pie.

The main reasons mass shootings are more prevalent in America now than in the “Good Old Days,” are two-fold: First, white America is losing its demographic and cultural power; Second, there are exponentially more guns now than in its mythologized past. This explosion in the number of guns in circulation is not distributed equally among the population. While the number of guns being manufactured and sold has skyrocketed, the percentage of households that own guns has been steadily declining. This means those who do own guns are owning more and more of them. I'm pretty sure the Venn Diagram of homes with guns and racists is damn near one, complete circle.

I'm not saying all gun owners are racists but a lot of the ones who own multiple guns, who purchase semi-automatics, bump stocks, high capacity magazines, push for open carry, are pro-Stand Your Ground laws, reject even the most sensible background checks, are racist as fuck. The NRA, right wing radio, FOX News, and Republican politicians have fed these people a steady diet of fear since the passage of the Civil Rights Act. They've latched onto anything and everything non-white that can be peddled as a threat. They've done this with to great success. If you don't think so, just look at the spike in gun manufactured and sold starting the second Barack Obama was elected in 2008. At no point did he discuss taking anyone's guns during the campaign but the mere fact a black man became president scared the living fuck out of white supremacists to where they went on a weapons-buying spree that would make Adnan Khashoggi blush. There was a small spike in guns sold after Bill Clinton was elected but it went back down to normal levels during his second term. New guns in circulation hit a record high in 2008 and the number more than doubled by the end of Obama's second term. If you don't think race and white supremacists' fears were not the cause of this, you aren't too bright.

This relationship between guns and white supremacy in America is why you can't have a rational discussion about gun control. Racist fears will always override common sense, logic, evidence, social well-being, decency. To make matters worse, their irrational fears have filtered down to a lot of other gun owners. Every day I hear someone say, “I'm a responsible gun owner and I don't do....” or “I know a lot of gun owners who are responsible and they don't do...,” as a rationalization and justification to not only defend the status quo but to argue for access to more guns. A lot of the “good gun owners” are sure carrying a lot of water for the “bad gun owners,” right now to the point it is impossible for me to discern which is which. Practically speaking, there isn't much difference, politically, between an overweight, shirtless red neck posting pictures of himself holding his AR-15 in front of a Confederate Flag and the gun-owning Republican next door who is a CPA who drives a KIA Soul because both are obstacles to any gun reform. The CPA might not think he is giving cover for and be providing support to Cletus's white supremacy when he parrots NRA talking points but he sure as fuck is. If this wasn't true, you'd see these “good gun owners” come out against their fellow gun-owning brethren whenever there was a school shooting or some other horrible run-related incident. The silence of “good gun owners” tells you where they stand and to me, it seriously calls into question just how “good” they really are.

A good person doesn't stand quietly by as children are gunned down in schools, as families are worshiping in church, as people are watching a movie in a theater. A good person doesn't parrot conspiracy theories about gun confiscation, Jade Helm, FEMA camps, race wars... A good person doesn't look at the overwhelming evidence from the American Medical Association, the CDC, and every other industrialized country in the world and come away with the ideas that more guns are needed and teachers should be armed. You can say and think what you will about the people you know and love who own guns about how “good” a person they are but my definition of what constitutes a good person doesn't cover this kind of moral failing.