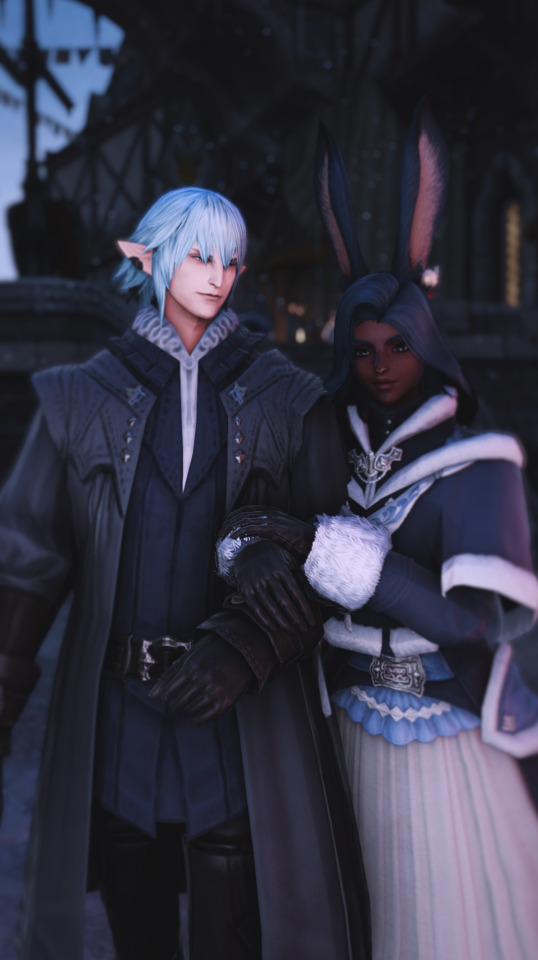

#the forced happiness to the conflation of recognition of the self through the other as intimacy

Text

the economy of love in close quarters,

a learned thing

#io laithe#:> the things that make me see shrimp colors#ffxiv#azia gposes#io/estinien#io/zenos#io/haurchefant#io/mikoto#the trajectory of her love life is everything to me#the forced happiness to the conflation of recognition of the self through the other as intimacy#to a whirlwind fling because she can and she's hanging by a thread#to the comfort and intimacy and excited passion she's caught glimpses of but not quite been able to grasp as something whole#okay goodnight

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why It Matters: 13 Reasons Why

I still have 2 episodes left to watch in the first season of 13 Reasons Why, but I wanted to get down my thoughts about what the show is doing and why it matters.

1. Clay, who is willing to deny his own masculinity when confronted – as when Tony asks Clay whether or not he is a man to goad him into rock climbing – is ultimately revealed to identify with and project masculine sexual desire. When Hannah become agitated and conflates Clay with all the other “men” who have hurt her, this is not unreasonable behavior. Masculinity is traumatic for all of us and Hannah’s reaction reveals Clays desire to identify with his gender which, despite his resistance in some areas, is ultimately on full display when it comes to intimacy/sex. This is because in western society, intimacy and sex are not areas in which we can rely on support from people within institutional contexts (obviously our friends may assist us with these matters, but the support from family, teachers, or other authority figures is likely to be little to nonexistent). Sex and intimacy become areas where we often have to rely more on our experience with cultural institutions than on our experiences with other human beings (that is, at least until we actually have intimacy/sex). This demonstrates an important lesson: the areas in life where we are forced to rely more on abstract identities and values rather than experience gained through interactions with others are the areas with which we are the least happy. This points to the shortcoming of any identification with a self informed by cultural values as the basis for decision making. When we make decisions based on who we believe ourselves to be, rather than on the feelings we get navigating the institutions of society in relation to other people, we are relying on ideas to satisfy us, rather than other people. For instance, if Clay was not compelled to act as the man in his sexual encounter with Hannah, he might have been able to notice and respond to her feelings of distress, which were really his feelings in that moment as well. Instead, Clay holds on to his ideas about sex and this allows him to ignore the presence of a trauma which Hannah cannot or will not ignore. However, it should be noted that the trauma of masculinity is even greater for Clay, and his need to live with it all the more demanding. After a life of not being masculine enough, the insistence of his masculinity when entering uncharted territory ends up costing Clay and many many other men the opportunities for intimacy that they crave so badly and need in order to make decisions which are not based on an imagined relationship to a “self” inextricable from the cultural institutions within which it is constructed. This is perhaps most tragically reinforced in Hannah’s final words to Clay on his own tape when she tells him that unlike everyone else, he was a nice guy. With these words, Hannah clearly wants to convince Clay that her suicide was not his fault. But in a way, this is the ultimate slap in the face as it reveals that she was never really able to see the real Clay. Clay wasn’t a nice guy. He hurt Hannah with some of the things he said and did. Did things to keep them apart based on his own anxieties. Clay definitely isn’t the cliché of the nice guy either who feels entitled to attention from women just for being a decent person. Clay, like everyone else, was a person suffering in pain. The “nice guy” that Hannah sees and acknowledges in Clay is actually the source of his problems. The image of the “nice guy” is what arises through Clays identification with masculinity. He’s locked in tension from this image and tries to get away from it as much as he goes towards it. Clay is not the “nice guy” any more than Hannah is the “crazy girl”. These personas are the symptoms of their pain, not something to be celebrated or believed in. But this truth is only recognizable through intimate contact with another, and so ultimately Hannah’s assurance of Clay as a nice guy is the proof that Hannah no more recognized or understood Clay’s pain than Clay understood hers. At least, that is before the influence of intimacy, which here in no small coincidence comes through media. If there is optimism in these events, it can only be found through the notion that media is the institution of human intimacy which allows for an “intimacy with the other” in a way that goes beyond the intimacies we try to achieve between selves. As the increasing percentage of those who report being lonely attests to (up from 20% in 1980, to 40% today:http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/medical_examiner/2013/08/dangers_of_loneliness_social_isolation_is_deadlier_than_obesity.html) the relationship between sex and intimacy is an area where we are failing as a society. As we turn to abstract values as a result our collective decision making will become more divided as we lose the empathy which might otherwise guide human interactions.

2. With suicides, just like with any other tragedy, as rational subjects often feel the need to respond to these situations with a question: why did this happen? However, behind this question is a far more sinister refrain of a society that demands justice: who’s fault is this? The question of blame is ultimately just as fraught as the question of intent, and yet, it is a question that we insist on answering and asking as human being, even of the the most sensitive and painful subjects. We are right to ask that question. The question of blame is essential for change to occur, the issues are the answers we find our selves arriving at. Who was to blame for Hannah Baker’s suicide? Was it the teachers and faculty of the school who overlooked her pain and instead covered their asses? Was it the students who are featured on the tapes? The ones who used Hannah for their own desires and refuse to take any responsibility for the pain they inflicted on her? Or was it Hannah herself who brought it all upon her self with her self-centered, moody, erratic, and irrational behavior? What makes 13 Reasons Why’s depiction of this question effective is because the answer provided by the show is all these things and none of them. One thing that I very much appreciate is the ways the creators demonstrate that ultimately, Hannah is her own worst enemy. For any single person, she undoubtedly plays the largest role in her alienation, but for every interaction she causes to go bad, there’s another in which someone else inflicts pain on her. We should insist on recognizing the way Hannah’s suicide was her own fault so to speak, but we could never blame Hannah, and not just because we like her or relate to her. Some of Hannah’s behavior can perhaps be recognized as not only self destructive, but actually a cry for help. As in Clay and Hannah’s short-lived moment of intimacy, were someone able to recognize her behavior as the evidence of the damage that social institutions inflict on the body, perhaps her fate could have been averted. Ultimately it is necessary to see the ways in which Hannah is at fault for her own death in order to grant us the empathy to recognize that the fault for Hannah’s apparent transgressions lies with the institutions themselves and the people they socialize us to be. This same point can be extrapolated and applied to the teachers and students who are also at fault, but not to blame, for Hannah’s death. As Sherry so callously puts it, Hannah went through they same things they all did. And she’s right, but this recognition allows us to reverse an obvious question about these events. The question becomes not why did Hanna Baker take her own life? But, what do these other students do to be able to go on living in these circumstances. When we look at the terrible behavior and poor judgment displayed by many of the students on the tapes, we see that these are the lengths that these people have gone to live with the pain that caused Hannah to take her life. They lie to themselves, as in Justin’s refusal to face the truth of Bryce’s rape. They hurt each other. They take from each other. What’s more, they refuse to get close to each other. Why? Well as I argued above, and as becomes evident with Clay, but also Justin and Jessica, when you become close to another person you become more aware of the pain that you can now sense is shared between you and not something you possess alone. We stop being able to believe in the lies of subjective identity and we are forced to stop running and confront that pain, for an “other” and no longer for our “self”. Justice can only ever be justice for others. Justice can never be for the self alone. If 13 Reasons Why has a thesis statement, this is it. This can be justice for Hannah Baker, but more truly, this is justice for the “other” in general. Justice for all those who go through what Hannah Baker did, even the teachers who are put in a position where doing whats best for themselves means existing at a distance from their students and their problems. You do not get justice for the “other” by punishing the person who hurt another person, you get justice by changing the system that hurt them both, that hurts all of us to this day. In 13 Reasons Why it is our institutions, not just school but capitalism, not just capitalism but identity, not just identity but gender, not just gender but sexuality, which are on trial. These institutions and the identities they allow to be created through them are ultimately what is to blame for Hannah’s death. As a society we need institutional justice of the justice for the “other”. Any justice for the self against the individual is simply the instillment of more pain.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Aden Brand, Celia Bellamy, and Feelings

A Collection of Thoughts on The Larkspur Series

It’s safe to say, if you’ve been reading my writing for any length of time, I take characterization very seriously. Especially in the Larkspur series, which began life as a sexy one-off about boys in collars that turned into two, three, and possibly more books. The reason for that, beyond my increasingly irrational attachment to the characters, is my interest in the kinds of stories I can tell in this world. It’s an odd one, after all. The Larkspur series is populated with a host just a little quirky, just a little tragic people, who aren’t always telling the truth to themselves, let alone everyone else in the room. Most of all, my interest lies in the themes at my disposal.

(Yes, themes. Come for an erotic romp about spanking bottoms, stay for the essay on what those spanked bottoms represent!)

For starters, I want to talk about Aden Brand, the protagonist of Caught and Collared and the subsequent books in the series. Aden is our unwitting hero, in a mundane world of melodramatic trials and tribulations. He’s a little remote, a little jagged around the edges, and a little bruised in the kinds of places he doesn’t let show. While he first appears in the book as an example of moody romantic hero, whose broken heart is won over by someone determined enough to see past his jaded facade, Aden has much more going on than that.

Aden is the product of abuse and neglect. His unprepared mother Sarah left him with his equally unprepared father Gale. While Gale did the best he could for the son he had no idea how to raise, Gale’s alcoholism, emotional distance, and anger issues shaped Aden in profoundly negative ways. As an adult, Aden exhibits most of the signs of trauma endemic in the children of alcoholics, such as his lack of self-worth, his sense of isolation from others, and his fatalistic, all-or-nothing attitude whenever faced with unknowns. He frequently misinterprets Ellie’s friendship as pity, and tries to punish himself for the dissolution of Kristoffer’s marriage by telling Kristoffer to return to Celia.

Gale casts a long shadow over everything Aden does, thinks, and feels. No matter the distance Aden strove to put between himself and his traumatic childhood, Gale’s alcoholism has continued to haunt him. In the subsequent books, as Aden’s finally started processing that trauma with his father’s passing, Aden begins overcoming those learned behaviors. He takes stock in his own self-worth, and fights for the things he wants. He grows closer to Ellie now that they’re on a more even keel, feeling more like her friend than her pet project. With Kristoffer, Aden is finally able to have a healthy, honest relationship, based on mutual respect and recognition of each other’s needs.

(I have a lot of things to say about the overlap between Aden as abuse survivor and Aden as a masochist in a d/s relationship, but I’ll get to that in another post. It certainly isn’t my intention to conflate trauma with kink, especially since I’ve tried to use kink as a vehicle for Aden’s personal growth. Confidence through the release of shame and guilt, acceptance of self through the acceptance of the means of one’s pleasure, affirmation through the recognition of one’s needs by others, etc. But that’s coming...)

Now, let’s get to what’s really important here, I think, moving forward in the series. I want to talk about Aden’s thematic foils throughout the series. You have Kristoffer, first and foremost, who is somewhat of an inversion of Aden’s storyline. Instead of coming from nothing, Kristoffer came from privilege. Instead of being distant, Kristoffer is effusive.. Instead of breaking under family dysfunction, Kristoffer cut ties with his family. Instead of shying away from the complexities of his sexuality and sexual expression, Kristoffer embraces them.

The introduction of Milo Herrera-Lopez in the upcoming sequel provides another foil for Aden. As Kristoffer’s only other long-term romantic partner besides Celia, Milo is a glimpse into the kind of life and relationship Aden could’ve had, were things different. They’re very different people, but have specific shared traits that attracted Kristoffer to them respectively. Both Aden and Milo are aware of this fact, and their relationships in the second book follows the resolution of these tensions.

However, the most important thematic foil to Aden’s development, who plays a critical role in Caught and Collared and becomes a fully-fledged character Bought and Sold, is Celia Bellamy. While Celia can be easily dismissed as a romantic rival vying for Kristoffer’s affections, by the second book her underlying inability to connect with others continues to fuel her rivalry with Aden.

Despite their differences, Aden and Celia have a great deal in common. They both come from emotionally distant, neglectful fathers. While Gale Brand was a physically abusive alcoholic, Philip Bellamy was a philandering workaholic. Aden watched Gale disappear into drink, while Celia watched her father vanish into the family company. Gale taught Aden to be distrustful of others for fear of being used, while Philip taught Celia that people were tools to be used as such. Aden grew up under the burden of caring for his neglectful father, as Celia grew up under the burden of following her father’s footsteps. Aden retreated from his family because he couldn’t relate to them, and Celia retreated from her family because her role as CEO of the family company had consumed her identity. Aden fears attachment because he fears abandonment, meanwhile Celia controls her relationships to keep from being open to abandonment.

They’ve both retreated behind the walls of their respective forts. Aden’s have been built up as a defense mechanism against abuse, Celia’s enabled by a lifetime of privilege. Neither allow others the chance to harm them.

Most importantly, they both have Kristoffer, who is essentially the major stabilizing force in their lives. This is because Kristoffer is a care-taker at his core, whose identity hinges on his ability to meet the needs of those around him. (There’s a laundry list of reasons for that, but I have a post planned to address that in the near future.) That said, Kristoffer has strikingly different relationships with Aden and Celia.

To Aden, Kristoffer is a steady, guiding hand. He takes up the control that Aden willingly gives up so that Aden feels safe, wanted, and loved. While recognizing Aden’s masochism means dominating Aden, it always comes from a nurturing place. It’s the total submission to Aden’s emotional needs through the complete control of Aden’s physical wants. Kristoffer wants what Aden wants, because Kristoffer just wants Aden. And if Aden wants to be owned by Kristoffer, Kristoffer will own him.

To Celia, Kristoffer is the forever patient, forever doting husband, eager to submit to every need and command. He’s pierced her icy exterior to see everything hidden behind it, and prides himself on being the only person that makes her happy. He makes her laugh, because no one else would think to try. Kristoffer wants to belong to Celia, and Celia wants to own Kristoffer if it means keeping him to herself forever.

It’s the loss of Kristoffer that fuels Celia’s destructive (both outwardly and inwardly) behavior, while Aden’s gain (for lack of a better term) is what moves him toward a better place. This conflict drives Aden and Celia, and drives their respective character development throughout the first two books.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Kate Riley

Question #2: Gone but Not Forgotten

Aretha Franklin: Her Spirit Lives on Through Living Room Dance Parties

My grandmother raised my mom and her sister on a diet of Diana Ross, Marvin Gaye, The Stylistics, and Aretha Franklin. My mom then raised my sister and me on the same diet. Aretha was queen in my house. When you hear her voice coming from the speaker, it is a call to report to the living room for a very intense dance party. My mom and my sister, both singers, sing right along with the record. I sing too just not as well. We all dance. No matter what we are doing or where we are in the house, none of us can resist the call of “Chain of Fools,” or “Baby, I Love You.”

I don’t remember the first time I was exposed to Aretha Franklin, she just has always been. I was singing “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” when I was five.

Because of the huge presence she had during my childhood and the impact she has had on my family, I was taken aback when I heard about her death and I wasn’t heartbroken. It took me awhile to figure out why. I remember the first time I saw a picture of Aretha Franklin that wasn’t on one of my mom’s old albums when I was maybe 10 or 11, and I didn’t recognize her because she had aged since the 1970s. In my head, Aretha was never a real human who was walking around somewhere on earth. She was a deep and rich and mesmerizing voice that came out of my mom’s record player. She was some other magical being with a beehive hairdo smiling at me over a yellow-green feathery collar. She was young and she glowed. I didn’t consider that she was an actual person let alone that she would age like one.

I am 21 now, and understand that everybody ages. I know that the voices that come out of the radio and speakers have people attached to them. At least I thought I did until I heard that Aretha had passed away. I was shocked to realize that she was still a mystical, celestial being in my head; a voice and album art. I still don’t think that it has hit me that she has passed away, and I’m not sure if it will.

To me, Aretha Franklin means three generations of women in my family dancing and singing and feeling strong, happy, warm, and utterly at peace. It sounds strange, but she is a feeling and an energy, a memory with the ladies in my family more than she is a person in my brain.

The Aretha living room parties have not stopped but are definitely less frequent now that my sister and I no longer live at home. If they were to stop, that to me would be the greatest blow. It’s almost if I have convinced myself that we three are keeping her alive through dance parties.

Question #3: Turn Down for What?! Criticism.

Reviewing Reviews: Jon Caramanica’s Review of Frank Ocean is Effective and Important

Jon Carmanica’s review of Frank Ocean’s 2011 concert at the Bowery Ballroom combines an impressive array of adjectives and modifiers, points of reference, and background on the artist to paint a picture of not only the show, but who Ocean might become as a musician.

The review uses language like “prickly, bubbly space-soul” and “harmonious and affecting conflation of music and love,” to not only demonstrate to the reader the type of sound Ocean has created on his mixtape, but also somehow the emotions that that sound affects in the listener. Carmanica also makes references to other artists and genres to provide a more concrete context for those that don’t understand “prickly, bubbly space-pop.” He is “Maxwell-esque” and has a “Sam Cooke ache.” This balance allows most readers, whether they have a broader knowledge of music or not, to place Ocean somewhere amongst the music they do know. They now have an idea of his sound.

This review, which is very positive, was also written at the very beginning of Frank Ocean’s rise to the top, probably propelling him forward quite a bit. Readers of the New York Times were most likely not yet aware of the artist who released his first mixtape to Tumblr. A glowing review in the New York Times for an unknown or little known artist acts as a propellor, pushing the subject of the critique into further success and recognition. Criticism can act as a powerful tool to give credit where credit is due (and perhaps not yet being given).

This review shows the power and the importance of art criticism. Art is a form of communication, an attempt at understanding the human experience more deeply, the beginning of a conversation. Art critique is a response. It continues the conversation, makes us think more deeply still not only about the art itself but the statement the art is trying to make. Was the statement effective? Could it be better communicated? How can we deepen the ideas?

Carmanica’s use of language also highlights criticism as an art within itself. “Prickly bubbly” is melodic, poetic. He created something beautiful and separate from the thing which he was critiquing to begin with. His command of language is artistic.

Fun (but serious!) #1: Blood Orange’s “Jewelry” Explores Insecurity, Hope, and his own Blackness

In this song off of his 2018 album titled “Negro Swan,” Dev Hynes performs a soulful and emotional song in several parts. The ideas he is communicating are complicated: the feeling of not being welcome in a space and occupying it anyway unapologetically, struggling with self-love, the anxieties of people of color, and holding on to hope. Generally songs that have several parts (this one leaps from spoken word to almost choral singing to rap and back again) feel disjointed to me. I have trouble following the whole song or grasping the larger concept the artist had. Hynes however, does it seamlessly.

Beyond the content of the lyrics, this song would be a pleasure to listen to if I didn’t understand any of the words. The rhythm of the spoken word that opens the song meshes with horns that become the voices in the choral portion that ends abruptly to make way for the next chapter. The rap portion of the song features Hynes deep and rich voice speaking over a beat that is somehow round and hypnotizing. This beat slowly becomes more and more melodic, transitioning into singing again. The song is an experience, almost ethereal, and one can almost glean meaning and the emotional journey Hynes takes through the music alone.

I sent this song to my sister as soon as it was over so that she could experience what I had experienced, and I think that says something about the emotional force of this song.

Fun (but serious!) #2: Maybe I Don’t Hate Writing After All

What sticks out to me most on the sheet is the first section in which I explain my interest in the class. In it I say that I am a Journalism major with an interest in the arts, and I would like to be able to combine my interests, learning to write about what I love. What I did not say on the paper but what I was feeling at the time was a frustration with journalism and with writing in general. My interest in the class was a final effort to prove to myself I didn’t pick the wrong major.

I am someone who has always been told that I can write and so I have pursued writing. However I did not take into consideration when declaring my major what a torturous process writing is for me. My true interests have always been in the arts, and so I took this class in the hopes that I would find some aspect of writing that I would enjoy. Writing about things that I (at the time) would rather be doing seemed like my best bet.

This semester, being able to choose my favorite songs, movies, and exhibits that I am interested in, I may have found what I was looking for. It’s still a laborious process for me but I have realized that the amount I struggled writing other things in the past did not necessarily come from the act of writing itself. It came from writing about things I didn’t care about, things that were boring to me. It was writing about Cinema Paradiso that made me change my mind about writing. My Italian major is something I was always confident in and realizing I could combine the two was a revelation that allowed me to regain some of my lost hope. Not only have I been reminded that I can enjoy writing, but I have learned to develop new appreciation for the art forms I love by examining them more closely and in a different way.

0 notes

Photo

Take Back Your Weekends (and Leave the Work at Work)

Weekends aren’t what they used to be. And it’s become a serious problem.

That’s the message of Katrina Onstad’s new book The Weekend Effect: The Life-Changing Benefits of Taking Time Off and Challenging the Cult of Overwork. Onstad, a Canadian novelist and journalist who has written for the The New York Times, starts off by documenting the origins of our 64-hour escape from the office (Thank you: religion, unions, and Henry Ford). Then she dives into the ongoing struggle to step away from our smartphones and make the most of that time, with compelling stats, quotes from progressive CEOs, and anecdotes that will make you nod in agreement or shake your head in recognition.

Not that there’s much chance you’d argue with her thesis. Nearly 40 percent of Americans reported working 50 or more hours per week, putting us far ahead of our European counterparts, with less to show for it. But that’s starting to change. Onstad interviewed leaders who are capping workers’ hours to brilliant effect (including Jason Fried of Basecamp and Dustin Moskovitz, formerly of Facebook). And she offers myriad ways we can reclaim our leisure time with meaningful pursuits, as opposed to another Netflix bingefest that leaves you wondering where the weekend went. Here she speaks with 99U about her findings.

Early in your book, you compare the United States and Canada to typical working hours in other countries. What stood out to you?

The one idea that surprised me is that shorter-hour cultures are more productive, and have stronger economies, which seems counterintuitive. But over and over, researchers have discovered that after about 40 hours a week, our productivity drops off. Sometimes people can go through crunch periods, particularly in the creative industries: If you have a big project, you may be able to fight through it and hit 50-60 hours for a few weeks without a degradation in the work.

But it’s not sustainable beyond that. It’s not just the health issues that arise, with exhaustion, substance abuse, heart disease, and all the physical ramifications of overwork, but people start to introduce more errors. So the argument in favor of overwork becomes much more of an emotional and social-status argument rather than what we know about how people work and how to get the best out of employees. Germany has a short-hour work culture and is one of the strongest economies in the world. Mexico and Korea have the longest hours and are among the least productive. The U.S. and Canada are somewhere in between.

It’s really interesting the way a work-first mentality can grip an entire nation: France recently passed “right to disconnect” legislation that essentially says that after 5 or 6 p.m. and on weekends, your boss cannot contact you unless it’s an emergency. We’re so tethered to our workplaces and our devices that that concept seems almost sacrilegious or a sign of weakness, but France is recognizing that asking people to work crazy hours just isn’t helpful economically.

Much of the efficiency research cited in your book relates to manual labor, which isn’t surprising because creative work is really hard to measure. Has anyone tried?

It’s definitely hard to gauge. There’s a whole body of research around wartime industries and mechanized environments that are easy to measure, but with creative workers we have to look at case studies. In the book, I talk about the Electronic Arts scandal about 15 years ago where programmers in the gaming industry were working 70-80 hours a week and completely exhausted, and not being compensated for overtime.

What happens in those environments is this conflation of work and play. As creative people, we often think of ourselves as artists, and we’re even encouraged to do so—you’re supposed to do it for the love of the job or the love of the art, which sets up a dynamic that’s really open to workplace exploitation and exhaustion.

If you love your work, it’s really hard to turn it off, and there are all kinds of forces at play that are opposed to you turning it off, including your own sense of self. If you’re a creative professional and you’re in a museum and you get a note of inspiration, you might think, This is something I need to post to Instagram. But if we’re always feeding our “work selves,” it takes us out of the present moment, and that has really bled out from the creative class into other spheres—everybody is curating their brand, from the designer to the accountant.

To be clear, I didn’t write this book to scold people, just to point out that it can be a grueling way to live, and it’s a gateway to missing out on so many other experiences of the world, if work is the driving force of every experience, including leisure. For me the lens is the weekend: Can we protect 48 hours, where we’re not just in promo mode? Is it possible anymore, and what would that look like?

And you’re not just asking questions: Your book shares some stories of Jason Fried, CEO of Basecamp, who embraces shorter weeks during the summer, and Facebook founder Dustin Moskovitz, who has had a lot to say about the topic.

Moscovitz is a really interesting case, because he has spoken so openly, yet tentatively, because there’s still such a stigma around this idea that working less is a strategy for success. When he and I spoke, he talked about the early start-up days being insane and all the typical responses—back pain, living off of energy drinks, and feeling terrible all the time. He’s written about it on Medium, saying, “If we’d worked less, we would’ve done better work,” which is unfathomable to people on the outside. Now he has his own company, Asana, and he has tried to undo a lot of those habits by instilling some progressive workplace practices like not infantilizing workers so they can create their own schedules, and trying to ease up on weekends. And he’s modeling that behavior, which is one of the most important things leaders can do, actually showing employees, “I’m off-line, and that grants you permission to go off-line, too.”

For years, we heard people focusing on the concept of “work-life balance,” but lately I’m hearing more people say that work-life balance is just a myth. Has your research led you to believe that?

It can definitely feel like one of those unattainable goals that may set you up for failure—that thing on the horizon that you’re always chasing. So I don’t know if the concept of work-life balance is a useful idea. Because it’s all life, right?

What I don’t like in that equation is that it almost encourages this masking of our real lives. In the book, I mention a study that focused on men and women in a high-pressure consulting firm: The women would clearly articulate to their bosses, “I need time to take my child to the dentist or to attend a funeral,” whereas the men were doing the very same things, but doing it invisibly, and they were rewarded for not saying it out loud. What I would hope, instead, is that we can shift workplace models to something holistic, where we acknowledge that we’re people all the time, and that our lives are going to infringe on our work and our work is going to infringe on our lives, but when we’re not working, we use that time in a way that’s really healthy, and that we’re not expected to be on call 24-7. Because the idea that work will always be present is just not sustainable.

The last half of your book discusses ways for people to embrace the weekend and really make it count. Are people really struggling with how to spend their weekends?

There’s some real anxiety about free time, and there must be something to this compulsion to fill every minute and commodify it, right?

The original scaffolding of the weekend was obviously religion, and the essential point of congregation was to stop working, and come together. But now, in our secular society, people don’t have that same compulsion. Today, many people spend the entire time “decompressing,” and research suggests those extremely passive forms of leisure don’t actually make you feel better; they just provide instant gratification or quick hits. As part of that Sunday night let-down, people think, “I went to the mall and I got a pedicure—why don’t I feel any better?”

So I was very interested in this category of “active leisure,” which has much longer-lasting benefits, and the biggest piece of it was socializing—finding real human connection. We know that rates of social isolation are higher than they’ve ever been; while we may be really digitally connected, we’re not necessarily connected to one another in a meaningful way, and that’s an urgent problem for our own happiness and for the health of our communities.

That’s why I wanted to talk to people who are doing creative things in their own communities, and they’re palpably happier as a result. I always thought volunteering seems so pious, and who wants to spend their weekend doing it, when it’s so boring? But it turns out that volunteering actually creates the sensation of more time. If you don’t want to spend 5-6 hours every Saturday volunteering at a soup kitchen, then try a one-off event here and there, because there’s incredible value in that.

In your book, you share your own struggle with carving out time, and making weekends feel meaningful. How’s it going for you?

Well, as it turns out, my book is right! Which is incredibly vindicating. The biggest things for me is being attentive to how I spend my time, saying, “No, I don’t need to bring my phone with me when I go to the park,” and “It’s OK if I’m completely off-line for 24 hours—the world is going to continue to spin.” My family has really pulled back on scheduled activities for the kids, which is a huge piece for people who feel crunched. It’s OK to let your kids be bored, and set them loose—you don’t need to spend every minute shepherding them through the city. I’ve started volunteering with a writers collective offering workshops in marginalized communities, started to make more time to enjoy parks and greenspace in the city of Toronto. And I’m forcing myself to not rely on Netflix to fill empty windows of time, but to actually look at the big picture, and ask: What do I want my life to be?

0 notes