#the nerd title goes to Ireland and Wales

Photo

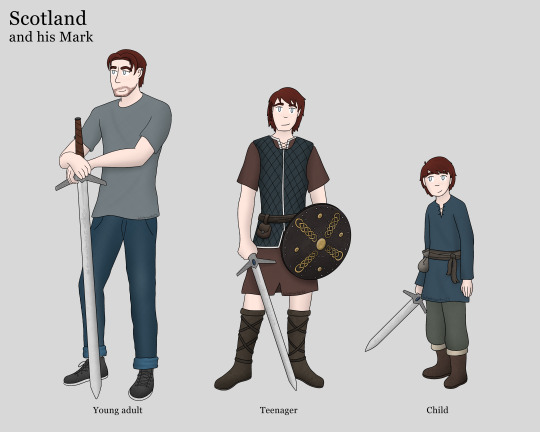

Here’s Scotland with Stonecleaver throughout the years. The Sword is his Mark that helps him greatly in fighting magical creatures or break curses. To summon the Sword, Scotland stomps his foot once and hold out a hand so his Mark shimmer into existence in his grasp.

It can act as a normal sword, but if it uses magic, the runes on the blade will flare and the sapphire gem will hum with each strike. As explained in this post, one of the abilities of the sword is to shrink/grow so it’s easier for the wielder to carry it.

How Scotland got his Mark: (warning: slash to the leg)

Scotland found his Mark as a young child (around 10 years old) when exploring a cave after hearing rumours of a hag hoarding stolen goods from several villages. Curious and a bit over-confident, he tried to sneak into the cave to banish the hag, but was caught in the middle of writing the sigils needed for the spell. The hag attacked him and in a wild panic, Scotland grabbed the first thing he saw from the pile of stolen goods: a short sword. However, the sword seemed to have a mind of its own because it tried to fight both the hag and Scotland, resulting in the boy getting a nasty gash on his leg. Incapacitated, Scotland scrambled back deeper into the dark cave with the sword still in hand.

But instead of being plunged into darkness, the sapphire gem on the handle of the sword and the runes on the blade started to glow, giving him enough light to navigate through the tunnel. However, it also attracted the hag’s attention, giving his position away. With nothing else to do, Scotland did the best thing he could think: he chucked the sword at her. By sheer dumb luck, it struck her arm, pinning her against the wall.

That was when he realized the sword did more than just randomly attack anyone and glow in the dark. No matter how hard she tried, the sword wouldn’t budge. It was like it was frozen in time and space. Scotland took that discovery as the chance to banish her for good. After the whole ordeal, he grabbed the sword and pulled. Surprisingly, he didn’t meet any resistance and it didn’t try to fight him off again. In fact, when he held it, it felt right, like it was meant to be in his hand.

The next day, he was shocked to find the Sword gone and for a time, he thought it was all a dream. It took a lot of trials and errors (mostly looking silly waving his hands around and calling out for the sword), but in the end, he managed to find a way to summon it.

Since then, he trained for decades to get use to it and learn all its power. He’s usually the first one to jump into the fray when his family is in danger, especially if it’s a magical threat. He may be a paramedic in his spare time, but in the world of magic, he won’t hesitate to be on the offensive, knowing he has his brothers’ back to patch him up later.

Ireland | Scotland | Wales | England

#hetalia#aph scotland#hws scotland#yeah teenage ali looks like hiccup in httyd 2 lol#but make him a bit more of an asshole and less of a nerd#the nerd title goes to Ireland and Wales

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Dragons - A Natural History, by Dr Karl Shuker

Hello fans of dragon books! Here is a review of a book that I found quite helpful in researching mythology and folklore, by the famous cryptozoologist Dr Karl Shuker!

More under the cut:

This book is arranged slightly chaotically, with the five chapters being titled Serpent Dragons, Semi-Dragons, Classical Dragons, Sky Dragons and Neo Dragons. The bizarre classification doesn’t make the book hard to navigate as it’s only around 120 pages long with large illustrations, so a dragon can be found easily by flicking through the pages, but these arbitrary titles do not add anything to one’s understanding of dragons.

Each chapter has a selection of 5-8 dragons picked from mythology and folklore, and the chapter then goes in depth into each dragon. Usually it does this by telling a story, but for some dragons there is a quick description of the dragon alongside theories and ideas linking the dragon to the fossil record. With dragons such as the cockatrice and the Chinese dragon, the text will jump around the folklore to give the reader a full idea of what the dragon is about, rather than focussing on one story.

The writing style is engaging; each of the stories is written with dramatic flair – exciting to read to yourself, but without the storybook language to make it a collection of bedtime stories for a small child, making the recommended reading age for this book anything from ‘scholarly children’ to ‘adults that enjoy dragon facts’. All stories are from folklore or mythology, with very little extra embellishment from the author; it’s hardly a primary source but it means you can get the full extent of say, Seigfried slaying Fafnir, without reading the whole Volsungsaga. It’s a good first-stop for learning about mythology.

The strengths in this book is that it is very broad and covers a wide range of dragons from a wide range of cultures. However, one of the limitations is that the texts touches only on the surface of the stories; for example, the names of famous dragons are sometimes missing (the dragon of Koshi is called Yamata no Orochi in many other texts for example, and a winged serpent from Welsh mythology is called a gwiber).

The other limitation is the links between mythology and palaeontology. As someone who loves heaps of both, I found some of the ‘explanations’ for dragons a little odd as sometimes the author leaned dangerously close to the ‘living dinosaur’ theories (for a variety of reasons you can easily debunk ‘living dinosaur/other prehistoric reptile’ theories). However, Dr Shuker does keep his voice impartial and doesn’t say “the Loch Ness Monster was definitely a plesiosaur”, but I personally don’t like the “but maybe, possibly, if a plesiosaur survived… and was hiding… maybe…?”, but that is a matter of personal taste. If you love that sort of stuff, it’s sprinkled throughout many chapters.

The book is presented nicely, with a huge diversity of illustrations, from photos of dragon artefacts to woodcut prints, carvings, paintings, embroidery – the images are a rich history of dragon culture in themselves. This gives the book a ‘non-fiction’ feel, and helps educate the reader as to where these dragons fit in the public consciousness.

For example; in the ‘Seigfreid and the Slaying of Fafnir’ chapter, we have a painting from 1880 by Konrad Dielitz, a still from the Niebelung film by Fritz Lang (two parter film, 1922-1924, based on Richard Wagner’s opera based on the legend) and a photograph of a wooden carving in a 12th century church in Norway. All three of these images are of the same subject, but each one carries layers of meaning – the sword-and-sorcery style fairy tale illustration by Dielitz, the old black and white film with the giant dragon puppet and the wooden carving nearly as old as the story itself puts the tale in context of a much richer story of European culture and how much we like dragons and dragon slayers.

The illustrations alongside each chapter are one of the things that really make this book pop as a comprehensive introduction to the world of dragon mythology. The book is only 120 pages long, so it’s not going to be an in-depth anthropological dig into why so many cultures like to talk about big serpent monsters, but for the short amount of pages it does try it’s best to put forward as many different dragons as possible: a must-have for a dragon nerd’s bookshelf.

Dragons covered are:

Ampitheres and other winged serpents, Basilisks and Cockatrices, the dragon of Bel, Bunyips, the Carthaginian Serpent, Cetus, Chinese dragons, the Dragonet of Mount Pilatus, Fafnir, the Gargouille, Gwiberod (just named ‘winged serpents of Wales’, and likened to Kuehneosaurus), Jormungandr, Komodo dragons, La Velue (named Peluda in the text), the Lambton Worm, the Lernean Hydra, the Leviathan, the Lindorm King, the Loch Ness Monster, Mokele-Mbembe, the Mordiford Wyvern, O-Goncho, the Piasa, Quetzalcoatl, the Salamander and the Pyrallis, a sea crocodile spotted near Ireland, Sea serpents (linked to whale palaeontology), the Mushussu or Sirrush, St George’s Dragon, the Tarasque, Tatzelwurms, Tiamat, the Wantley Dragon, the Weewilmekq (or giant leech), Yamato no Orochi (just named as the dragon on Koshi), and a few other brief dragon mentions.

Author and Book Links:

Dr Karl Shuker’s website

Dr Karl Shuker’s blog

More about the book

Amazon link to book (£2-£4) (to avoid Amazon, best bet is eBay, the book is currently out of print so pretty much every copy you’ll buy via Amazon, eBay or another seller will be second-hand - often good as new!)

20 notes

·

View notes