#the parallel julieverse

Text

Headline: Iconic Street Artist Unmasked: Dame Julie Andrews Revealed as the Mastermind Behind Banksy's Artistry

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

LONDON, April 1, 2024 (PJV NEWSWIRE) -- In an astonishing turn of events that has rocked the art world to its core, Dame Julie Andrews, the celebrated singer, actress and star of family classics like Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music, has been unveiled as the creative mastermind behind the enigmatic street artist, Banksy.

The shock revelation was announced by a team of international researchers at the Tate Modern in London. Head researcher and world-renowned Banksy expert, Professor Savant of Whangdoodle University, explained that the team initially set out to map the geographical patterns of Banksy's work, but noticed an intriguing overlap with the locations of Dame Julie's UK appearances over the years.

Further investigation uncovered a series of coded messages hidden within Banksy's artworks that, when deciphered, spelled out various Andrews references. The celebrated Bansky stencil "Girl with Balloon" revealed a sequence of tiny numbers in the balloon string that corresponded to ASCII values spelling "How do you hold a moonbeam in your hand?". "Kissing Coppers" contained an anagrammatic mix of letters on the policemen's epaulettes that unscrambled to read, "The constable's responstable..."

The smoking gun came when researchers discovered a hidden subterranean studio deep beneath the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, containing stencils, spray cans, and a collection of Andrews' vinyl records. Here the team located an early draft version of Banksy's "Flower Thrower" where the famous bouquet was a posy of edelweiss.

The revelation that Dame Julie is the hand behind the elusive graffiti superstar has stunned the entertainment and art worlds alike with critics scrambling to reevaluate the combined Andrews-Banksy oeuvre. Professor Savant discerns a deep, thematic link between Banksy's provocative street murals and Andrews' film characters, both of which challenge societal norms with a mix of whimsy and sharp commentary.

And the Banksy pseudonym? Savant believes it is a nod to the name of the family transformed by Andrews as the eponymous flying nanny in Mary Poppins. Just as Poppins upended the repressive Edwardian world of Mr Banks with her magical carpet bag of tricks, Andrews as Banksy has been sprinkling another brand of subversive mischief across the urban landscapes of the modern world.

Dame Julie Andrews has yet to make an official statement, but a source close to the star says, "Julie has always had a flair for the dramatic and she constantly seeks new outlets for her creative voice, so it's not all that surprising that she would take it to the streets!"

THIS IS A BREAKING NEWS STORY. FURTHER DETAILS TO FOLLOW.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Julie Andrews Story (BBC Radio, 1976) Part 1: From Walton-on-Thames to the Great White Way

The Parallel Julieverse is proud to present "The Julie Andrews Story", a special three-part radio profile produced by BBC Radio and first broadcast in January 1976.

Julie's relationship with BBC Radio traces back to her early days as a child performer in the 1940s and 50s when she lit up the airwaves as "Britain's youngest singing star". It's a testament to her enduring popularity that the national broadcaster continued to follow Julie's journey closely, crafting this rare gem of an audio profile in the mid-seventies. Based on original transcription recordings, this special video presentation offers the first chance to hear a programme that has lain dormant since its initial broadcast, half a century ago.

But beyond the mere allure of rediscovery, this video breathes life into Julie's formative years. Titled "From Walton-on-Thames to the Great White Way", Part 1 of the "The Julie Andrews Story" traces Julie's tender years from her humble beginnings in Walton-on-Thames, through the bustle of the post-war variety and concert stages, right up to her dazzling Broadway debut in the 1950s.

Adding depth and dimension are the candid insights from those who stood shoulder to shoulder with Julie. The voices of Lilian Stiles-Allen, Barbara Andrews, Peter Brough, and many more shed light on Julie's meteoric ascent. Each interview weaves a tapestry that reveals fresh insights into the artist and the woman behind the legend.

So, sit back and journey with us, retracing the footsteps of Julie Andrews as she transitioned from a young English lass to Broadway's brightest star.

DISCLAIMER: This is a fan preservation project; it was created for criticism and research, and is completely nonprofit; it falls under the fair use provision of the United States Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. section 107. All materials used remain the property of the original copyright holders.

#julie andrews#broadway#west end#musical theatre#classic film#hollywood#british#walton on thames#Youtube

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Julie Andrews Story (BBC, 1976) Part 3: Star of the Sixties

The Parallel Julieverse is proud to present "The Julie Andrews Story", a special three-part radio profile produced by BBC Radio and first broadcast in January 1976.

Julie's relationship with BBC Radio traces back to her early days as a child performer in the 1940s and 50s when she lit up the airwaves as "Britain's youngest singing star". It's a testament to her enduring popularity that the national broadcaster continued to follow Julie's journey closely, crafting this rare gem of an audio profile in the mid-seventies. Based on original transcription recordings, this special video presentation offers the first chance to hear a programme that has lain dormant since its initial broadcast, half a century ago.

In "Star of the Sixties", the captivating finale to "The Julie Andrews Story", we journey with Julie through her skyrocketing ascent as an international film sensation, propelled by blockbuster titles like "Mary Poppins", "The Sound of Music", and "Thoroughly Modern Millie". We also delve into the unexpected failure of her subsequent big screen musicals, "Star!" and "Darling Lili", and witness her graceful pivot to television in the early 70s with the award-winning variety series, "The Julie Andrews Hour". Interviews with esteemed co-stars and collaborators, including Michael Craig, George Roy Hill, Daniel Massey, Beryl Reid, Nick Vanoff, and Robert Wise, shed further light on this fascinating period of Julie's career.

DISCLAIMER: This is a fan preservation project; it was created for criticism and research, and is completely nonprofit; it falls under the fair use provision of the United States Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. section 107. All materials used remain the property of the original copyright holders.

#julie andrews#hollywood#classic film#british#mary poppins#the sound of music#thoroughly modern millie#hawaii#musicals#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Julie Andrews Story (BBC Radio, 1976) Part 2: Hollywood, Here I Come!

The Parallel Julieverse is proud to present "The Julie Andrews Story", a special three-part radio profile produced by BBC Radio and first broadcast in January 1976.

Julie's relationship with BBC Radio traces back to her early days as a child performer in the 1940s and 50s when she lit up the airwaves as "Britain's youngest singing star". It's a testament to her enduring popularity that the national broadcaster continued to follow Julie's journey closely, crafting this rare gem of an audio profile in the mid-seventies. Based on original transcription recordings, this special video presentation offers the first chance to hear a programme that has lain dormant since its initial broadcast, half a century ago.

In "Hollywood, Here I Come", the second chapter of "The Julie Andrews Story", we follow Julie's continued triumphs on Broadway and the West End with hits like "My Fair Lady" and "Camelot", leading into her meteoric transition to film stardom in the mid-sixties. Through the eyes and voices of those who collaborated with Julie during this heady transformative era – including Martin Ransohoff, Richard Rodgers, the Sherman Brothers, Robert Stevenson, and Robert Wise – we gain a deeper appreciation for her extraordinary career.

DISCLAIMER: This is a fan preservation project; it was created for criticism and research, and is completely nonprofit; it falls under the fair use provision of the United States Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. section 107. All materials used remain the property of the original copyright holders.

#julie andrews#broadway#hollywood#classic film#musical theatre#musical#my fair lady#camelot#mary poppins#disney studios#the sound of music#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

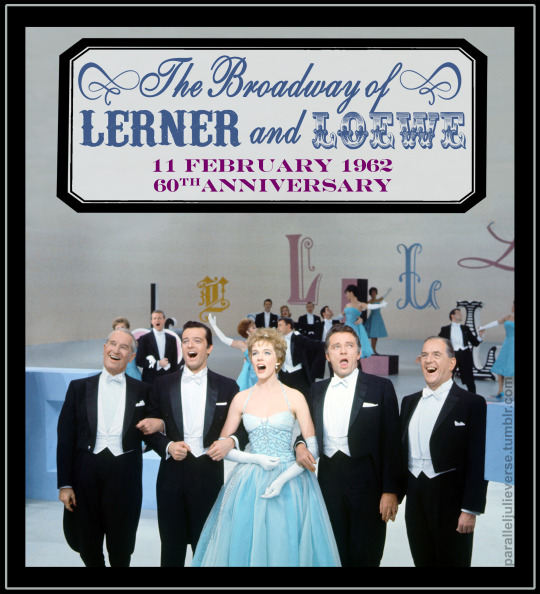

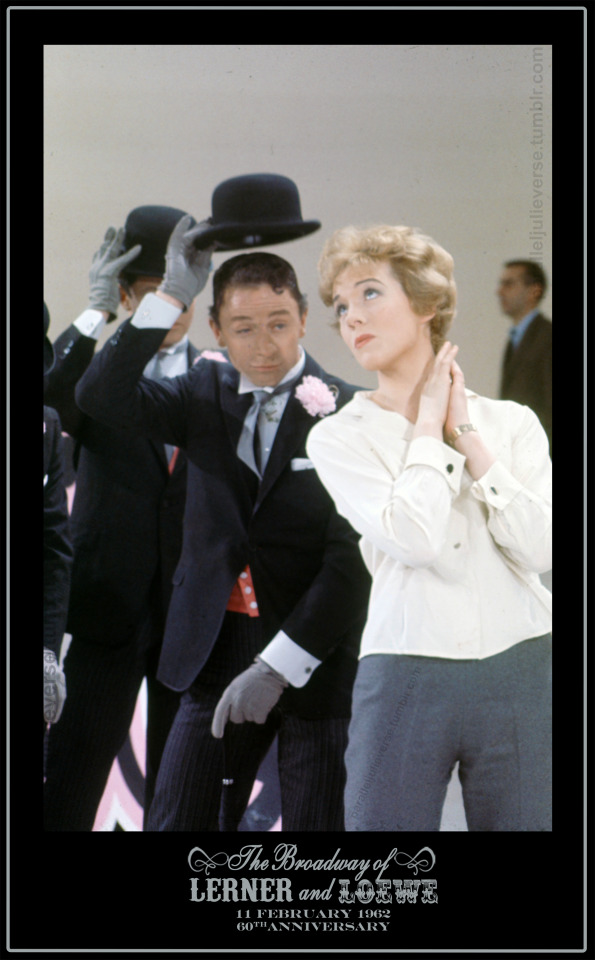

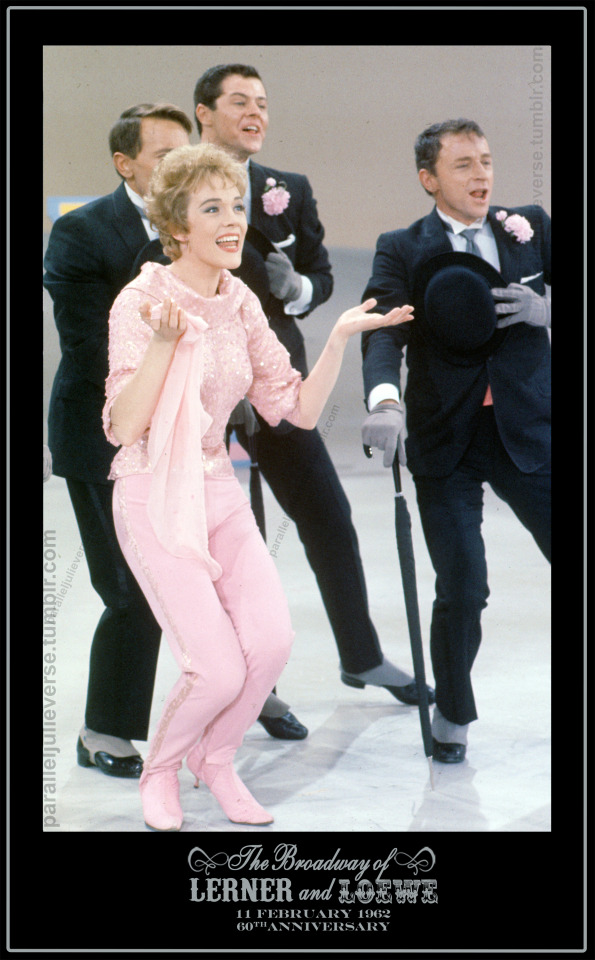

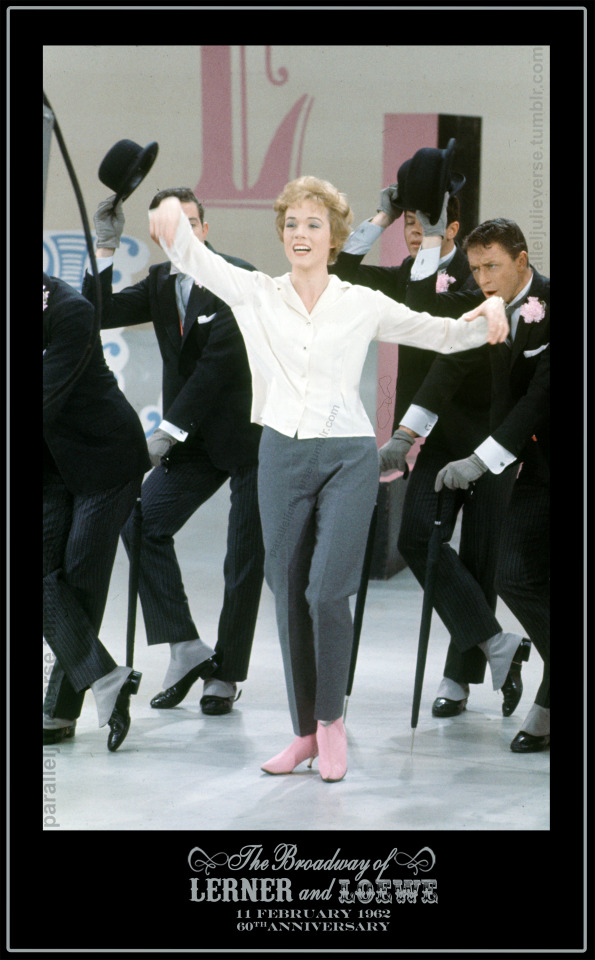

This Week in Julie-history: The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe airs on NBC, 11 February 1962

1962 was a year of significant changes in the life and career of Julie Andrews. It was the year she gave birth to her daughter and became a parent for the first time, something she frequently cites as her ‘greatest achievement’ (Andrews, 254). It was the year she bowed out from Broadway and took leave for what would prove to be a three-decade hiatus (Downing 8). And it was the year she was signed by Walt Disney for Mary Poppins and the start of a meteoric film career (Skolsky, 8).

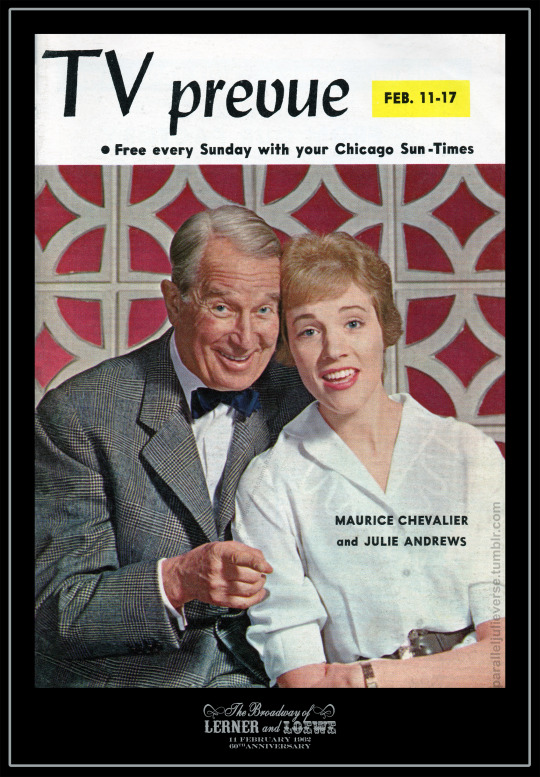

1962 was also an important year for Julie Andrews on television (Hull 1962). She was certainly no stranger to the small screen, having appeared in numerous variety shows, as well two gala tele-musicals, High Tor (1956) and Cinderella (1957). But in 1962 Julie appeared in a pair of TV spectaculars that showcased her versatility like never before. Most memorably, in June of that year, she co-starred with chum Carol Burnett in Julie and Carol at Carnegie Hall, a concept special that emerged out of the pair’s charismatic teaming on The Garry Moore Show. It proved a landmark event with ‘audience[s] clamor[ing] for more [and] critics dust[ing] off their most glowing verbal bouquets’ (Julie & Carol 7). The Julie and Carol show proved so popular that it launched a multi-decade series of reunion specials.

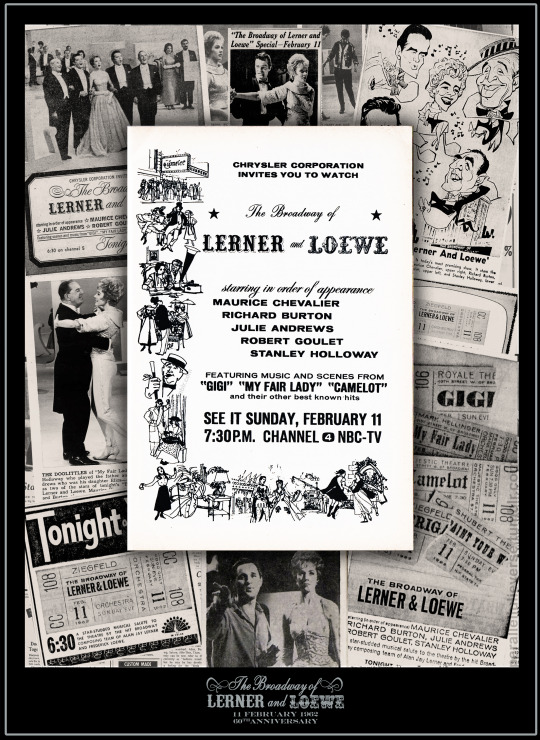

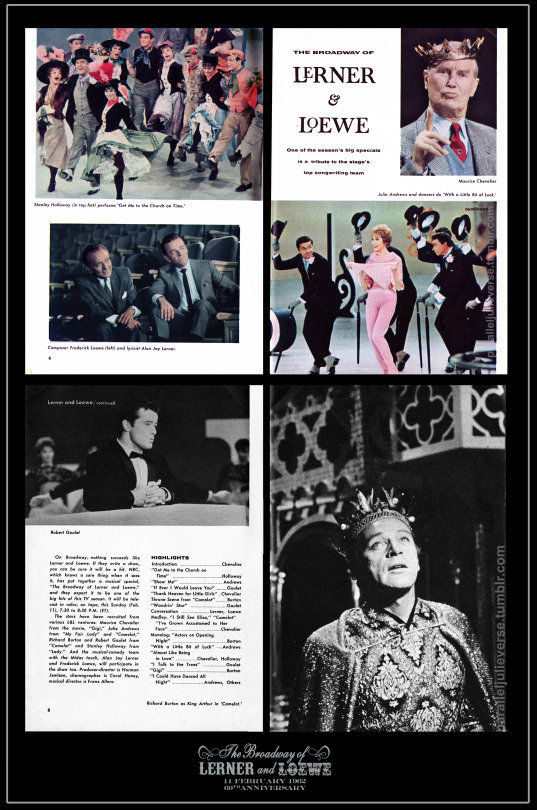

While it was inevitably eclipsed by the success of the Carnegie Hall special, there was another earlier TV gala that showcased the manifold talents of Julie Andrews for the TV-viewing public of 1962: The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe. As its name would suggest, the show was a tribute to the famed composer-lyricist team and their most popular musicals of the preceding fifteen years: Brigadoon, Paint Your Wagon, My Fair Lady, Gigi, and Camelot. It was also a showcase for some of Lerner and Loewe’s greatest star performers who had been given ‘an opportunity to shine at his (or her) best’ in their shows: namely, in order of appearance, Maurice Chevalier, Richard Burton, Julie Andrews, Robert Goulet, and Stanley Holloway (Color special 9-F).

That Julie was the (only) leading lady in the line-up was as fitting as it was complimentary. Not only was she was the star of two of Lerner and Loewe’s biggest Broadway hits, My Fair Lady and Camelot, but her marathon runs in these shows meant that, as Lerner himself noted, ‘Julie has been playing for us nearly one fifth of her life!’ (Downing 8).

There was added contextual significance to putting Julie firmly in the limelight in The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe. Jack Warner had only just secured the film rights for My Fair Lady and casting for the film version was the hottest topic in town (Archer 1). It is now a matter of historical record that Audrey Hepburn was Warner’s first -- and, as it transpired, only-- pick for the plum role of Eliza, but press reports at the time suggested Julie was still in potential consideration (Scott 6). Certainly, Julie held out hope. Not long after the decision was made to go with Hepburn, Julie related in interview:

‘[N]aturally I thought about myself for the movie role. But although I’m an optimist, and secretly hoped it would be I, I knew that I was a second or third choice. There were three of us in the race -- Audrey, Shirley Jones and myself. And if they didn’t get Audrey, I felt I had a chance. I know the part so well, and I did think it would be fun taking a crack at it again’ (Shearer 7).

As such, there was a lot riding on The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe and the special worked to showcase Julie to strong effect: giving her an opportunity to sing, dance, and emote in a series of both solo and ensemble set pieces including the explosive ‘Show Me’ from My Fair Lady. In addition, publicity for The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe played up the angle of Julie as star with profiles in major publications including a pictorial spread in Life magazine that twinned Julie with Lucille Ball as dual ‘queens’ of TV (Thompson 1962).

The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe was conceived and developed by Norman Rosemont, executive vice president and general manager of the Lerner-Loewe organisation. He spent almost three years pre-planning the project and securing a very lavish production budget of $350,000 (Bryant 3-D). To helm the production, Rosemont brought on board the talented young Canadian director, Norman Jewison. Today Jewison is best remembered as the award-winning film director of major Hollywood hits such as In the Heat of the Night (1967), Fiddler on the Roof (1971) and Moonstruck (1987), but the versatile director cut his professional teeth in TV. During the 50s and early-60s, Jewison helmed a series of big variety specials for major stars of the era including Harry Belafonte, Danny Kaye, Andy Williams and Judy Garland that saw him become ‘the highest-priced director of the highest-priced musical variety shows in all television’ (Krantz 21). Jewison had previously worked with Julie on The Fabulous Fifties (1960) and the pair had a very sympathetic professional and personal relationship (Stern 10).

A true creative, Jewison felt that a TV ‘show should have something to say...there must be a reason for a show to be on the air’. In the Lerner and Loewe special, Jewison described his approach as wanting to ‘take a look at the modern American musical theatre’:

‘It’s a magical thing, the stage. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, but it’s magic. On the show we’re letting several of our stars do numbers they’re not associated with, even though they were in the shows the numbers came from’ (Stern 10)

To this end, Jewison included several surprise twists such as Julie doing a jazz version of ‘A Little Bit of Luck’, Chevalier singing a jaunty ‘Camelot’, Burton performing the title song from Gigi, and Chevalier and Holloway singing a music-hall duet of ‘Almost Like Being in Love’ from Brigadoon. Jewison also included several big set pieces from these shows such as the throne room scene from Camelot and a grand ensemble finale of ‘I Could Have Danced All Night’ (Gaver 1962a 12).

Helping Jewison and his stars bring the production to life was a support team of major theatrical and TV talent (Messina 50). The show’s musical director and conductor was Franz Allers who had performed similar musical duties for most of Lerner and Loewe’s Broadway shows. The choreography was by Carol Haney, longtime associate of Gene Kelly in Hollywood and a major Broadway choreographer in her own right. To supplement the star power in front of the camera, memorable cameos were provided by Charles Nelson Reilly and Frances Sternhagen in a comic sketch interlude (Bryant 3-D).

The show itself was pre-taped at NBC’s New York studios in December 1961 (Ashby 1). Organising the production around the performers’ busy schedules was a major logistical challenge. Burton had to fly in from Rome where he was filming Cleopatra, Chevalier jetted in from the London set of Disney’s In Search of the Castaways, and Stanley Holloway came from taping a TV pilot in Los Angeles (Hull 5). Julie and Goulet were both still appearing in Camelot, so filming had to fit around their theatre commitments. In interview at the time, Julie described the taping of the show as ‘utterly crazy’:

‘We rehearsed for three weeks. They started taping about 7a.m. on a Saturday and finished Monday night about 6. And I had to break away for two Broadway shows on Saturday, and I was back taping at 8 a.m. Sunday and worked till 11 p.m., and the same arrival Monday and I finished at 2 p.m. and then to the theatre for the show on Monday night. Tuesday? I collapsed’ (Quigg 6E).

A full-colour broadcast of The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe was scheduled by NBC for Sunday 11 February from 7:30-8:30p.m. -- a primetime slot usually occupied by Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (Ashby 1). With sponsorship from Chrysler, it was given ‘one of the biggest publicity campaigns of the year’ (Smith 1962a C-12). The broadcast proved a major winner for both the network and the sponsor, attracting ‘big ratings’ and a favourable ‘letter response’ (Gaver 1962b 3).

Critical reception of the show was equally positive. There were a few dissenting voices -- the critic for The New York Times felt ‘the cumbersome injection of static commercials and other episodic intrusions’ meant that ‘the lilt and captivation of Broadway were realised only sparingly’ (Gould 36) -- but, for the most part, reviews were little short of laudatory:

Los Angeles Times: ‘[A] buoyant, bouncing, glittering color extravangaza...the show as a whole was a most pleasant hour...The soaring voices of Robert Goulet and Julie Andrews gave wings to the show [and] Norman Jewison staged the action with imagination’ (Smith 1962b C-12).

Chicago Tribune: ‘Rarely were so many performers of great musical and dramatic gifts assembled for television and never have they performed with more enchantment...Last night, TV was a musical paradise, an Eden of color and shining melody...Chevalier, at 73, gave a great performance as the host, and as a singer and dancer, Julie Andrews was in fine fettle’ (Wolters F-7).

Boston Globe: ‘It was a stirring, glittering presentation that in an hour caught much of the essence and magic of the Lerner-Loewe life “book”....It was a show to be treasured throughout...with Holloway tripping so delightfully through the rhythms of “Get Me to the Church on Time”, the adorable Miss Andrews taking her frustration out on dancer Johnny Harmon so prettily in “Show Me”, and Burton reciting his throne speech from “Camelot” so affectingly’ (Shain 12).

The Herald-Journal: ‘A more tuneful, professional folic through the wonderful song world of one of history’s most successful collaborations would be hard to imagine...Miss Andrews was never better on TV. She looked radiant’ (Danzig 8).

Daily Herald: ‘Take the product of song-writing team which has churned out such shows as “My Fair Lady”, “Gigi” and “Brigadoon”. Cast their finest moments with talent like Julie Andrews and Maurice Chevalier. Let a director of taste and imagination pull it all together. The result is a joy and a delight...Altogether it was a bright, warm and beautiful show’ (Lowry 8).

Cincinatti Enquirer: ‘[I] was almost overwhelmed by The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe...one of the gayest, most beautiful shows of the season. Staging and production of this song-fest of five fine Lerner-Loewe shows was most impressive. It was as colorful as the NBC peacock--in fact it was probably the best TV colorcast I’ve ever seen’ (Feck 10)

Valley Times: ‘Last night’s special production of The Broadway of Lerner of Loewe on NBC was unquestionably one of the highlights of the season and constituted a shining example of television production at its very best...Miss Andrews was never better, and that sentimental favourite, Chevalier, perfectly complemented the younger male stars of the cast...Add beautiful sets, superb production, lavish costumes and the overall director of Norman Jewison and you come up with a package that simply exudes class’ (Rich 9).

Detroit Free Press: ‘At least once a TV season amid the mountains of mediocrity, there appears one shining peak, a show to be treasured. Sunday’s The Broadway and Lerner and Loewe on NBC-TV, was one of those: an hour to rank...among TV’s greatest programs’ (Peterson 22).

Happily, because The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe was taped, it remains in existence and archival quality copies are stored in several repositories including the NBCUniversal Archives and the Paley Center for Media. The programme has never been given an official video release and, with copyright constraints, likely never will. However, multiple-generation fan copies of the show have circulated for years and can even be viewed on YouTube. Though not the greatest quality, it gives a sense of the colourful musical magic that TV audiences were treated to sixty years ago this week in The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe.

Sources

Andrews J (2008) Proust questionnaire. Vanity Fair. 572, April : 254.

Archer E (1961) 5 million film offer made for ‘Fair Lady’. New York Times, 27 September 27: 1, 78-79.

Ashby B (1961) Five top stars in February’s NBC ‘Broadway of Lerner and Loewe’. The Herald-Mail Video Viewer, 2-8 December: 1.

Bryant J (1962) ‘Lerner & Loewe’ extra-special. ShowTime. 9 February: 3-D.

Color special to be salute to Broadway (1963) The Shreveport Times. 11 February: 9-F.

Danzig F (1962) TV in review. The Herald-Journal. 12 February: 8.

Delatiner B (1962) Songs by Lerner and Loewe- ’nough said. Newsday. 12 February: C-2.

Downing R (1962) Cast honors M’el Dowd, Julie Andrews. The Cedar Rapids Gazette. 17 April: 8.

Feck L (1962) TV and radio: Weekend watching. The Cincinatti Enquirer. 13 February: 10.

Gaver J (1962a) Norman Jewison produces imaginative specials. TV Week. 28 January-3 February: 12.

_______ (1962b) The fall TV ‘special’ lineup is still up in the air waves. Oakland-Tribune TV and Radio. 10 June: 3.

Glenn NR (1962) This is NBC. Sponsor. 2 April: 16-17.

Gould J (1962) TV: 'Broadway of Lerner and Loewe'. The New York Times. 12 February:

Gross B (1962) Lerner & Loewe lead us down a magical street. Daily News. 12 February: 41.

Hull B (1962) Julie Andrews finds time for TV: Broadway star in Lerner and Loewe special tonight. Los Angeles Herald-Examiner TV Week, 11-17 February: 4-5, 12.

Krantz, J (1963) Norman Jewison: the stars' status symbol. MacLeans. 76(1) 5 January: 20-21, 30-32.

Lass B (1962) Starring Julie Andrews. The Courier-Journal Magazine: 36-37.

Julie & Carol renew magic with Carnegie Hall smasher (1963) TeleVues, 9-16 June: 7.

Lowry C (1962) ‘Radio/TV: “Broadway of Lerner and Loewe” good show’. The Daily Herald. 12 February: 8.

Messina M (1961) Stars set for musical spec. Daily News. 27 November: 50.

Peterson B (1962) Lerner and Loewe special: show to rank with TV’s great. Detroit Free Press. 13 February: 22.

Quigg D (1962) TV, Broadway and interviews keep Julie hopping. Chicago Tribune. 11 February: 4.

Rich, A (1962) Chrysler special called smash hit. Valley Times. 12 February: 9.

Rose. (1962) Television reviews: ‘The Broadway of Lerner and Loewe’. Variety. 14 February: 36.

Royal D (1962) Extremes meet at Carnegie Hall: Julie, Carol. Ithaca Journal: Showtime. 9-15 June: A5.

Scott V (1962) Big question in Hollywood: who will be ‘My Fair Lady’? The Herald-Journal. 19 April: 10.

Shain P (1962) Night watch: Lerner-Loewe showpiece -- need you say more? The Boston Globe. 12 February: 12

Shearer L (1963) Julie Andrews, Audrey Hepburn: Is there a five-million dollar difference between these two girls? Parade: The Sunday Newspaper Magazine. 4 August: 6-7.

Skolsky S (1962) Hollywood: Gossipel truth. Los Angeles Evening Citizen. 19 June: 8.

Smith C (1962a) The TV scene: Jewison makes Lerner-Loewe go. Los Angeles Times. 9 February: D-12.

_______ (1962b) The TV scene: Rare kudos for a rare sponsor. Los Angeles Times. 12 February: C-12.

Stern, H (1962) Norman Jewison directs 2 star-studded TV specials. News-Journal Weekend Magazine, 4 February: 10.

Thompson EK (1962) Spotlight: A lusty return by Lucy, a tuneful romp for Julie: two queen prepare for TV shows. Life. 52(1) 5 January: 74-79.

Wolters L (1962) Theater a madness and critic is happy. Chicago Tribune. 12 February: F-7.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2022

#julie andrews#the broadway of lerner and loewe#classic television#Lerner and Loewe#Broadway#musical theatre#richard burton#maurice chevalier#robert goulet#stanley holloway#my fair lady#camelot#nbc#the parallel julieverse

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

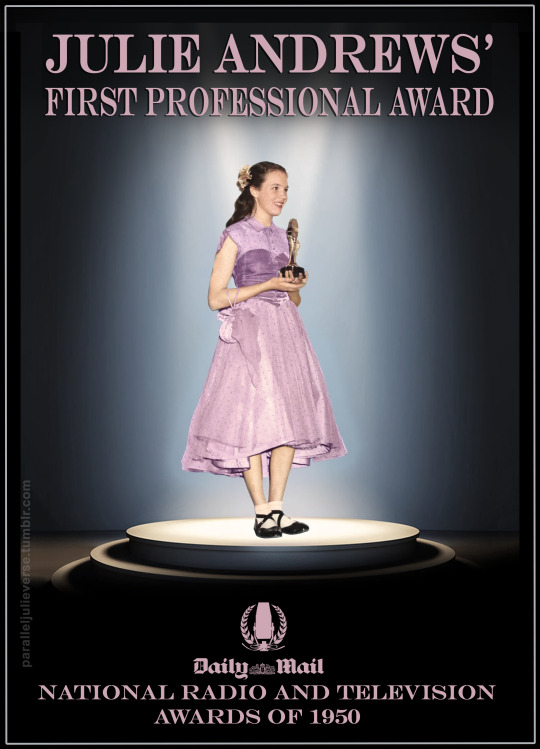

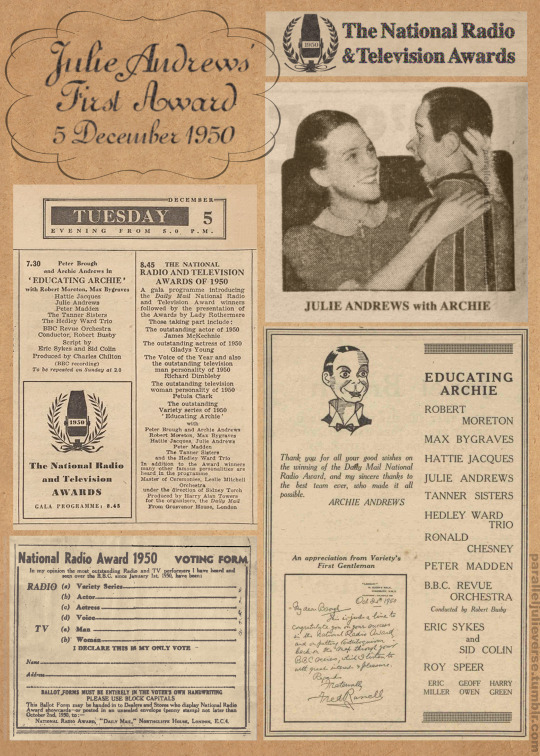

From the PJV Archives: Julie Andrews’ First Professional Award, 5 December 1950

The Parallel Julieverse could not be more delighted by recent news that the 48th AFI Life Achievement Award Gala Tribute to Julie Andrews will finally take place next June, having been postponed twice already due to Covid. In making the announcement, Bob Gazzale, AFI President and CEO, remarked: “Julie Andrews has sent spirits soaring across generations” and the AFI Tribute will “celebrate her in a manner worthy at a time the world needs it most” (AFI 2021). Our 2022 calendar is already circled...

While we wait for our Dame to receive this latest honour, we thought it might be fitting to shine a light on a much earlier accolade from the long and garlanded career of Julie Andrews. In fact, it was the very first professional award received by Julie when she was just 15-years-old on 5 December 1950. That this week happens to mark 71 years since this award was bestowed makes the post all the more timely.

As profiled in an earlier blog entry, in June 1950, Julie joined the cast of a new BBC comedy radio programme called Educating Archie, starring ventriloquist Peter Brough and his dummy, Archie Andrews. Cast in a recurring minor role as Archie’s neighbourhood chum, but principally on board as the show’s resident singer, Julie performed weekly on Educating Archie for two full seasons till early 1952. It was a fortuitous career move for the young star as Educating Archie proved a phenomenal hit, becoming the most popular radio show of the 1950s in Britain with a weekly audience in excess of 15 million, more than a third of the national population at the time (Elmes, p. 208). The programme thus gave the young singer a massively expanded showcase, bringing her voice into the sitting rooms of postwar Britain on a weekly basis and helping make her a household name.

As a sign of Educating Archie’s meteoric success, the programme was voted the ‘Best Variety Series’ at the end of its very first year in the National Radio and Television Awards of 1950.The Awards had only been launched the preceding year in 1949 as an initiative of the British Radio Industry Council with sponsorship from the Daily Mail newspaper (Street, p. 233). Previously, there had been no official forum for honouring British radio talent and the Council wanted to implement an annual award ceremony similar to those of other entertainment industries such as film and theatre (“Highest award”, p. 3).

Dubbed ‘Silver Mikes’ in reference to the 12-inch microphone-shaped trophies given to winners, the National Radio Awards were determined by popular vote with ballot forms published weekly in the Daily Mail and available at over 15,000 stores and radio shops throughout the nation (”Tommy Handley”, p. 1). Prizes were initially awarded in four core categories: Variety Series, Actor, Actress, and, Voice of the Year. For the 1950 Awards, two additional categories were added to accommodate the burgeoning new medium of television -- TV Man and TV Woman -- with the competition formally rechristened: the National Radio and Television Awards (’Choose’, p. 3).

The hasty addition of television to the 1950 Awards was a portent of brewing changes in the British mediascape that would, ironically, consign the newly minted Radio Awards to cultural obsolescence in a few short years. Though it couldn’t have been known at the time, the Awards were launched during what would prove to be a rapidly dimming twilight for broadcast radio in Britain. Television would soon become the nation’s preferred medium of domestic entertainment and, by 1954, the British Guild of Television Producers and Directors would initiate their own industry-specific awards (Kenny, p. 320). As a result, the National Radio Awards would only last for six years, hosting their final ceremony in 1955 by which stage, as David Kynaston (2009) notes, “there was just a whiff of the last hurrah” about them ( p. 354). Despite the brevity of their tenure, the Silver Mikes were roundly embraced by radio professionals and audiences alike in the early 1950s and, even today, they are remembered as “the most cherished prizes of the airwaves” during the Golden Age of British radio with a “roll of honour [that] was decorated with some of radio’s greatest names” (Jenkins, p. 13).

Meanwhile, back in 1950, competition was heating up for that year’s Silver Mikes. Although Educating Archie had only been on the air for a few months when voting started in September, it quickly emerged as a firm favourite to take out the top spot in the most popular Variety Series category (Wilson, “Archie, Petula...” p. 3). This category had been won the previous year by Take It from Here, a long-running BBC comedy sketch show which had, incidentally, played a role in Educating Archie coming to the air when network producers were looking for a fill-in programme to run during Take It From Here’s annual summer hiatus. Take It from Here was in competition again in 1950, along with several other strong contenders such as Ray’s a Laugh, Have a Go, and, Much-Binding-in-the-Marsh ("And the next object”, p. 5).

In the end, the booming popularity of Educating Archie proved unbeatable and the show easily took out the top award for Variety Series -- a feat it would repeat for three years running. Unlike other competitions, the National Radio Awards announced winners in advance of the ceremony, so the cast of Educating Archie already knew in early-November that that they had won Best Variety Series. Joining them as winners of the remaining categories were: James McKechnie (Best Actor); Gladys Young (Best Actress); Richard Dimbleby (Voice of the Year); Richard Dimbleby again (TV Man); and, Petula Clark (TV Woman) (“The Show” 1950).

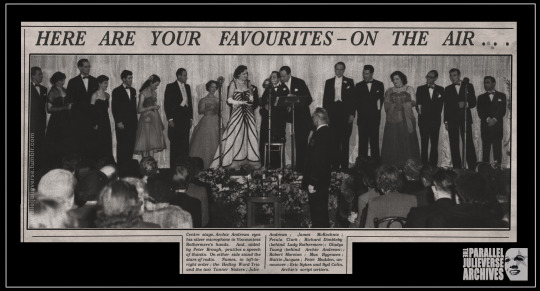

What the Awards ceremony might have lacked in suspense was more than compensated by entertainment glamour. Held in the Great Room of Grosvenor House, one of London’s poshest hotels on stately Park Lane, with Viscountess Rothmere presiding as society hostess, the 1950 Awards ceremony was a bona fide gala event. An audience of over 1500 crowded into Grosvenor House -- including “1000 Daily Mail readers chosen by ballot for a share in the glamorous evening” -- while outside “fans poured into Park Lane to see the radio celebrities arrive” (Wilson, “Archie stars...” p. 3). A special stage was erected in the Great Room with all the winners performing a brisk entertainment programme, supported by a full concert orchestra conducted by Sidney Torch, before receiving their awards from Viscountess Rothmere at the culmination of the evening. The ceremony was broadcast live across the BBC radio network with John Ellison describing the scene for listeners. Additional interviews with the winners were recorded for later broadcast on the Woman's Hour and portions of the event were filmed for the BBC’s Television News Reel (Wilson, “Archie stars...” p. 3). It is not known if any of this recorded material survives -- though newsreel footage from the preceding year’s awards is available-- but it would certainly make for fascinating, to say nothing of historically significant, viewing.

As part of the Awards entertainment, the whole cast of Educating Archie gave a potted performance which news reports described as “the big hit of the whole show” (Wilson, “Archie stars...” p. 3). It is not known what part Julie played in the routine but it is likely she sang a short song. Photos from the event clearly show Julie in the final line-up proudly holding her Silver Mike, dressed in a organza evening frock -- most likely made for her by Rachelle, the London-based designer who did many of Julie’s show dresses during her early touring years (Andrews, p. 242) -- topped off with a matching drawstring pouch bag and colour coordinated hair flower. Julie can also be seen in photos from the Awards rehearsal held earlier in the day, dressed in a dark shirtwaist dress with matching felt crescent cap that seems to have been a popular ‘working’ outfit for her in this era.

Given it was a collective award, it is unlikely Julie had to make a speech when receiving her Silver Mike, with Peter Brough no doubt performing that honour on behalf of the Educating Archie team. Still, we like to imagine that, had Julie been invited to the microphone to say a few words, she might have sung the sentimental little ditty that she routinely used to close her concerts in this era and that, decades later, she would perform again on her 1972/73 TV series, The Julie Andrews Hour:

Ladies and gentlemen, I just want to say,

Thank you so very much for the kind way you’ve listened

To poor little me.

Though when I make speeches, I am always at sea,

La la la la la, I’m always at sea.

But this is all I have to say, or nearly,

Your kindness I shall treasure very dearly,

Very dearly, la la la la la.

I mean it very really and most sincerely.

Ladies and gentlemen, ladies and gentlemen,

Good night, good night.

Sources:

AFI. “New sate set for AFI Life Achievement Award Tribute to Julie Andrews.” AFI.com. 1 December 2021.

“And the next object is . . . to find a winner." Daily Mail, 9 September 1950, p. 5.

“Choose your no. 1 stars of radio.” Daily Mail. 6 Sept. 1950, p. 3.

“Here are your favourites...on the air.” Daily Mail, 6 December 1950, p. 3.

Knox, Collie. "How will you choose your stars of radio?" Daily Mail, 15 January 1949, p. 3.

Elmes, Simon. Hello Again: Nine decades of radio voices. London: Random House, 2012.

"Highest award in radio." Daily Mail, 16 September 1949, p. 3.

Jenkins, Garry. "Return of the mighty mikes." Daily Mail, 5 September 1988, p. 13.

Kenny, Brendan. ‘British Academy of Film and Television Arts.’ In H.Newcomb, ed. Encyclopedia of Television, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2013: pp. 320-321.

Kynaston, David. Family Britain, 1951-1957. London: Bloomsbury, 2009.

"The Show to thrill millions." Daily Mail, 5 December 1950, p. 3.

Street, Sean. Historical Dictionary of British Radio. 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowmna & Littlefield, 2015.

"Tommy Handley radio award." Daily Mail, 14 January 1949, p. 1.

Wilson, Cecil. "Radio's brightest 60 minutes." Daily Mail, 13 Jan. 1950, p. 3.

_________. “Archie, Petula soar to the top.” Daily Mail. 20 October 1950. p. 3.

_________. "Archie stars at the radio star party." Daily Mail, 6 December 1950, p. 3.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2021

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

She’ll win your heart with her wicked art…

Happy Halloween 2021 from the Parallel Julieverse

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

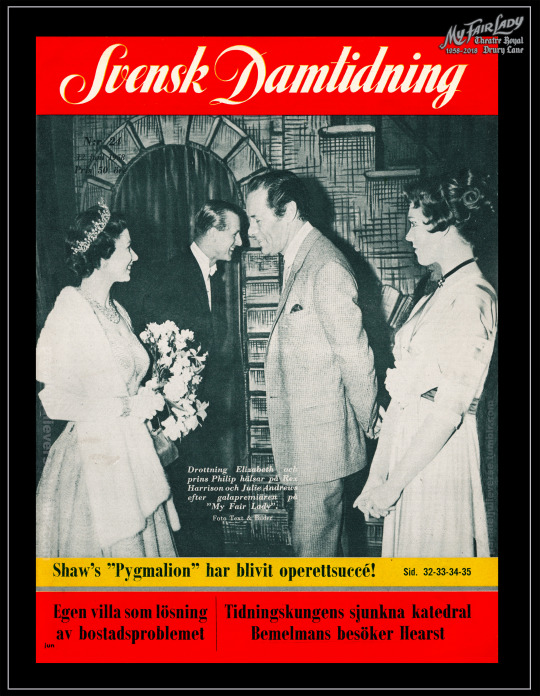

From the PJV archives: "Jag kunde dansa så...”

Cover of the Swedish magazine, Svensk Damtidning, from 12 June 1958 featuring Julie Andrews and Rex Harrison meeting the Queen and Prince Philip after the Royal Gala performance of My Fair Lady at Theatre Royal Drury Lane (5 May 1958).

#julie andrews#My Fair Lady#rex harrison#Theatre Royal Drury Lane#queen elizabeth ii#prince philip#1958#swedish#magazine#svensk damtidning#the parallel julieverse

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

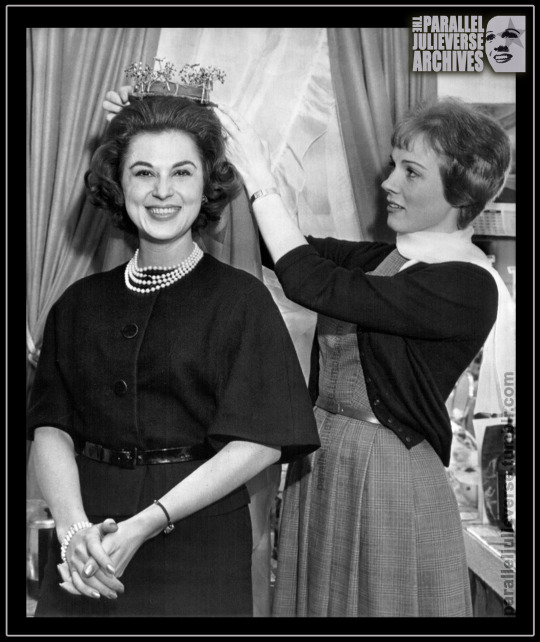

From the PJV Archives: A Star and her Standby

Original caption: Julie Andrews places crown she wears starring in Broadway play ‘Camelot’ on head of her standby, Helena Scott, in New York. Helena, in addition to being Julie’s standby, is the star of her own off-Broadway musical, ‘The Banker’s Daughter’. This unusual arrangement is possible because a standby, unlike an understudy, does not have to be present during a performance. A standby calls in before a performance to make sure the star will go on and after that her time is her own. Helena has an understudy should she have to substitute for Julie. (AP Wirephoto) February 1962

Born Helen Mary Schurgot in Atlantic City in 1928, Scott was a classically trained soprano who studied voice at Juilliard (‘Seashore soprano’, 3). She enjoyed early success as a company soprano with the New York City Opera where she played Musette in Puccini’s La Boheme, Natalie in Lehar’s The Merry Widow and Rose in Weill’s Street Scene (Gaghan, 31). In 1957, Scott sang the role of Natasha in the US premiere production of Prokofieff’s War and Peace which was telecast as a special event on NBC (Durgin, 17). In between operas, Scott performed in several long-running Broadway shows, starting in the chorus before graduating to bigger parts. She was one of the female ensigns helping Mary Martin wash that man outta her hair in South Pacific (1949), a royal consort and, in later performances, Tuptim in The King and I (1951), and a singing principal in the ill-fated Me and Juliet (1953), (Wallace, A-20). Allegedly, it was when she was cast in the latter show that Richard Rodgers suggested she change her stage name from Schurgot to Scott because he had trouble spelling it (Gaghan, 31). Scott’s biggest break came when she was cast to play the lead female role of Rosabella in the UK premiere production of Loesser’s Most Happy Fella in 1960 (Walrath, 29).*

After the London run of Fella, Scott returned to the US but her career didn’t sustain its early impetus. She appeared in a number of regional productions before coming on board in mid-1961 as Julie’s standby in Camelot, a position that had previously been filled by Inga Swenson (Wahls, C23). Scott continued to pursue other work: a music fair ‘tent’ production of The Merry Widow (Gaghan, 31), and the title role in The Banker’s Daughter, the off-Broadway musical mentioned in the caption above, where she received decent notices but the show closed in a matter of weeks (Davis, 37). After Camelot, a few further regional productions ensued: a summer stock tour of The Music Man (1962) opposite Van Johnson (Dear 5-D), and an upstate New York staging of Most Happy Fella (1962) (Walrath, 29).

Thereafter, the public record for Scott grows opaque. During the London run of Most Happy Fella, she met and subsequently become engaged to British publishing director, Christopher Lezard (‘Helena is..’ 15). A brief mention in a Broadway gossip column from late-1962, confirms the pair were married and Scott was moving permanently to London (Winchell, 15). She then seems to have retired from performing, devoting her energies to family life and raising her children, one of whom is British columnist and literary critic, Nicholas Lezard (Lezard 2013).

In terms of her Broadway career, Scott is one of those fascinating figures who hovers in the tenebrous margins of musical theatre history. She never broke through to major stardom and, today, her name would likely draw blanks from even the most ardent Broadway enthusiast. However, she -- along with thousands of others -- formed part of the mostly unsung army of supporting talent that helped shape and give vital form to the ‘golden age’ of the American musical. And Scott did at least leave a documentary legacy of some of her work in the form of recordings for several shows including the musical extravaganza Arabian Nights (1954), the Grieg-inspired operetta Song of Norway (1958), and the original London cast recording of Most Happy Fella (1960). These historical recordings reveal a soprano voice of demonstrable skill and training that was well suited to operetta-style musicals but that would have struggled in the face of the rapidly changing musical idioms of the 1960s.

And, so, to the $64,000 question: did Scott ever actually get to wear that crown on stage during the run of Camelot? While Julie never missed a scheduled performance during her 18-month tenure with Camelot, she did take a planned two-week holiday from the show from 26 October to 9 November 1961, followed by a further one-week break in early-March 1962 to rehearse and tape her TV special, Julie and Carol at Carnegie Hall. And, during those two periods, Scott assumed the role of Guenevere opposite William Squire who had inherited the lead role of King Arthur following Richard Burton’s departure in September 1961 (’Guenevere’ 24). As far as can be ascertained, there weren’t any official reviews of Scott’s brief run in Camelot, though a round-up of Broadway shows by columnist Bruce Galphin (1961) mentioned in passing that “Julie Andrews is gone [from Camelot] and Helena Scott just doesn’t fill the vacuum”. Mind, he also opined that William Squire was “[d]itto..in Burton’s old shoes” (8-A). The principal cast was an impossibly hard act to follow for anyone.

Either way, when time came for Julie to leave Camelot permanently in April 1962 due to pregnancy, Scott doesn’t seem to have been considered as a replacement. The role of Guenevere was initially taken over by Patricia Bredlin, an unknown singer from Wales who was brought over by the producers but who only remained with the show for three months before returning to the UK, reportedly due to homesickness (Gaver, B-2). Bredlin’s understudy, Janet Pavek, assumed the crown for several months (‘Successor’, 39), before Hollywood star, Kathryn Grayson, came onboard as the fourth and final Guenevere, closing the Broadway run before kicking off what would be a very lucrative national tour for the show in early-1963 (‘New Heroine’ 23; ‘“Camelot” Leaving...’, 1E).

Footnote:

* An extra tidbit of trivia, Julie was in the audience for the West End opening night of Most Happy Fella because her-then husband, Tony Walton, designed the scenery and costumes for the London production. Newspaper reports relate that, after the show, she "congratulated the leading lady, Helena Scott, with a rapturous: ‘I loved it’.” (Moynihan, 17; see also Griggs, 10).

Sources

‘“Camelot” Leaving N.Y. for National Tour’ 1963. Democrat and Chronicle. 6 January 1963: p. 1E.

Davis, James 1962. ‘“The Banker’s Daughter” Bright and Gay Musical’. Daily News. 23 January: p. 37.

Doar, Harriet 1962. ‘Music Man So Corny It’s Chic’. The Charlotte Observer. 10 June: 5-D.

Durgin, Cyrus 1957. ‘Impressive New Opera: Prokofieff’s “War and Peace” in US Premiere on NBC-TV.’ Boston Daily Globe, 14 January: p. 17.

Gaghan, Jerry 1961. ‘Opera, Broadway, Now She’s in Tents.’ Philadelphia Daily News. 28 July: p. 31.

Galphin, Bruce 1961. ‘“Camelot”, “Molly” Senior Citizens’. The Atlanta Constitution. 11 December: p. 8-A.

Gaver, Jack 1962. ‘Love Makes Understudy the Queen of “Camelot”’. The State Journal. 13 July: p. B-2.

Griggs, Barbara 1960. ‘The Spell of Corn and Cotton.’ Evening Standard. 27 April: p. 10.

‘Guenevere’ 1961. Daily News. 21 October: p. 24.

‘Guenny’ 1961. Daily News. 9 November: p. 76.

‘Helena is the Most Happy Gal’ 1961. Evening Standard. 12 January: p. 15.

Lezard, Nicholas 2013. Bitter Experience Has Taught Me. London: Faber & Faber.

Moynihan, John 1960. ‘In London Last Night.’ Evening Standard. 22 April: p. 17.

‘New Heroine’ 1962. Daily News. 20 October: p. 23.

‘Seashore Soprano Wins Club Plaudits.’ 1945. Courier-Post, 29 September: p. 3.

‘Successor’ 1962. Daily News. 9 July: p. 39

Wahls, Robert. ‘She’s 109 degrees’. Daily News. 10 November: p. C22-23.

Wahls, Robert 1962. ‘Camelot Queen is a Ringer’. Sunday News. 3 June: p. 25.

Wallace, Weldon 1960. ‘Musical Notes.’ The Sun. 21 February: p. A-20.

Walrath, Jean 1962. ‘Most Happy Fella Delights Audience. ‘ Democrat and Chronicle. 7 August: p. 29.

Winchell, Walter 1962. ‘On Broadway.’ Daily News. 10 September: p. 15.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2021

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

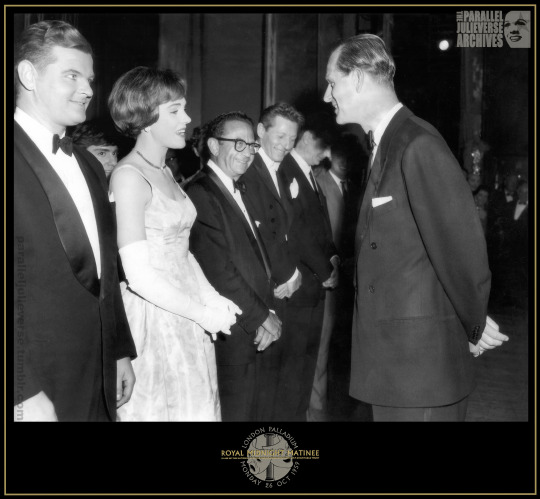

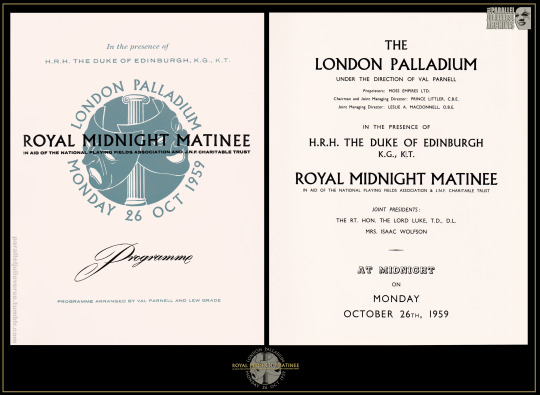

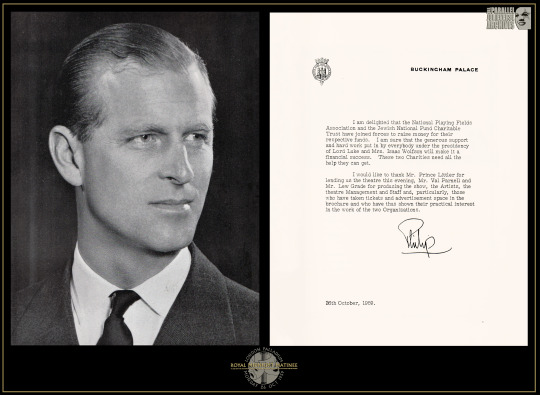

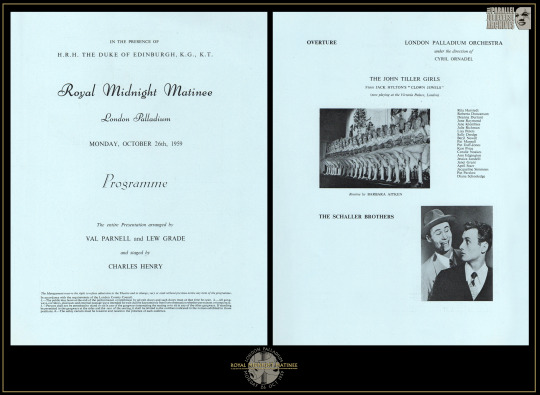

‘You meet your prince, a charming prince,

As charming as a prince will ever be...’

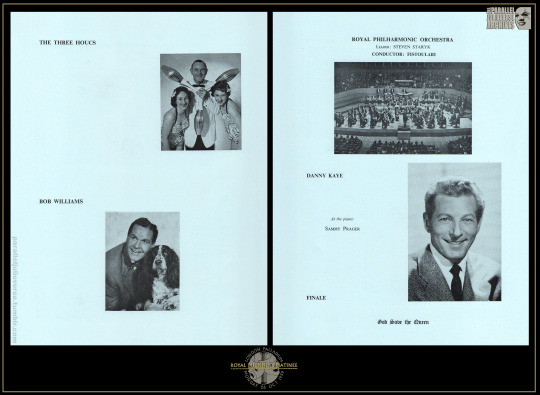

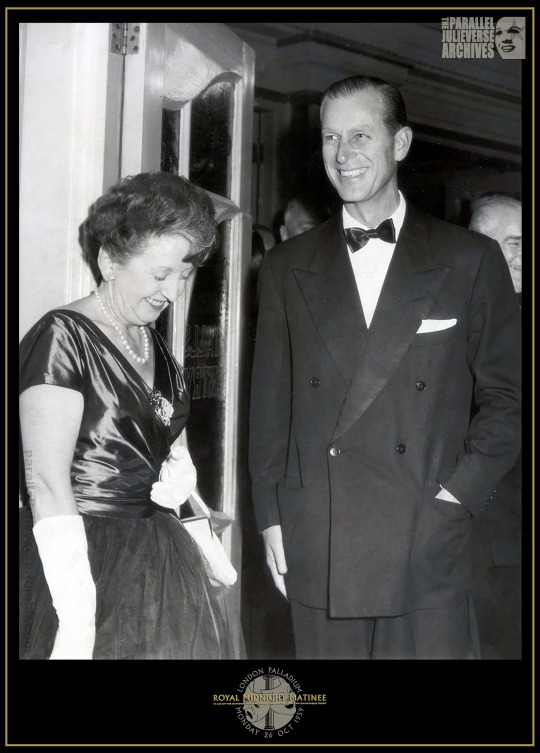

In honour of the recent passing of HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, we thought it appropriate to cast a brief spotlight on a little known occasion from British theatre history when our Julie sang for the Prince. Or at least one of the times, that is, because Julie actually performed before the Prince on several occasions over the years, dating right back to the very beginning of her career. Prince Philip was part of the King’s Party, along with his wife, the then Princess Elizabeth, at the legendary 1948 Royal Command Performance where Julie sang at age 13, the youngest artiste ever to be included in a Royal Variety. The Duke was also in attendance at several subsequent Royal Command Performances at which Julie performed including 1959 and 1977, as well as the special Royal Gala Performance of My Fair Lady in 1958.

One of the more significant performances, however, was a special late-night charity concert on 26 October 1959 at which Prince Philip served solo honours as official Royal sponsor. Titled Royal Midnight Matinee, the concert was an all-star variety benefit for the National Playing Fields Association -- a charity for which the Duke was President -- in conjunction with the Jewish National Fund Charitable Trust. Similar ‘midnight matinee’ events had been organised previously, held late at night so that performers from the various West End shows could participate. This particular late-night benefit was put together by two of the UK’s biggest impresarios of the era, Val Parnell and Lew Grade, who “hoped to make it one of the most spectacular shows ever known” (‘Prince’, 1).

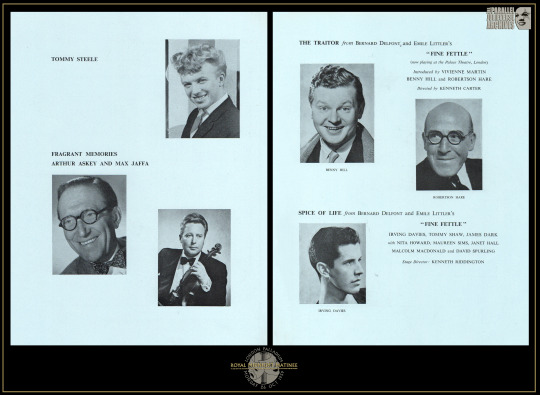

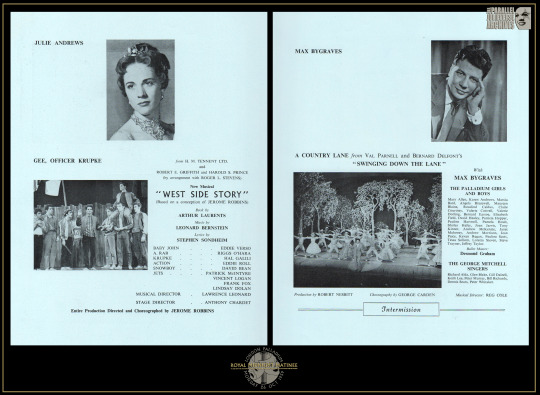

Held at London’s iconic Palladium Theatre, the Royal Midnight Matinee brought together a galaxy of big name stars, several of whom had featured prominently in Julie’s earlier professional life. From her days on Educating Archie and the pantomime Cinderella, was Max Bygraves and, doing headline honours, was the great Danny Kaye who had performed alongside Julie at the aforementioned Royal Command Performance in 1948. Another alumnus from that variety show, Arthur Askey, was also scheduled to appear but he had to withdraw at the eleventh hour owing to family bereavement and was hastily replaced by Jimmy James, Roy Castle and Bretton Woods. Rounding out the company was a diverse roster of talents including Tommy Steele, Benny Hill, Roberston Hare, Irving Davies, the London cast of West Side Story, the London Philarmonic Orchestra, the Tiller Girls dance troupe, and an assortment of music hall acrobats, jugglers and comics. For her part, Julie sang a trio of songs in a special solo set: “Little Bit in Love”, “London Pride” and, her mandatory signature piece, “I Could Have Danced All Night”. She rejoined the stage at the end of the night where the entire company sang a rousing rendition of “There’s No Business Like Show Business” before ending with the customary, “God Save the Queen” (R.B., 3). The curtain came down at 2:45am, after which Prince Philip went backstage to thank the 175 artistes who had participated and personally greeted several of the main stars, including Julie.

Reviews of the show were uniformly enthusiastic. The Times pronounced it “a brave show for the small hours”, the Daily Mirror adjudged it “excellent” (Rolls, 2), and The Stage called it “bright” and “memorable”, making special mention of Julie for “looking wonderful” and making “everyone in the theatre happy” (R.B., 3). Moreover, the night raised over £31,000 for its nominated charities (R.B, 3). A substantial portion of those funds came from advertising in the show’s programme which clocked in at 154 pages and weighed a whopping one-and-a-half pounds (Rolls, 2).

Sources:

‘Danny Kaye for Midnight Matinee.’ The Stage. 17 September 1959: 1.

‘Prince Philip at Midnight Matinee.’ The Stage. 16 July 1959: 1.

R.B. ‘Bright Show for the Duke.’ The Stage. 29 October 1959: 3.

Rolls, John. ‘Life in the Mirror: Heavyweight.’ Daily Mirror. 27 October 1959: 2.

Royal Midnight Matinee Programme. London: Purnell & Sons, 1959.

‘Stars Of Musicals In Midnight Matinee.’ The Times. 29 October 1959: 4.

#julie andrews#prince philip#duke of edinburgh#british theatre#west end#music hall#variety#Max Bygraves#tommy steele#danny kaye#musical theatre#theatre history#the parallel julieverse

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

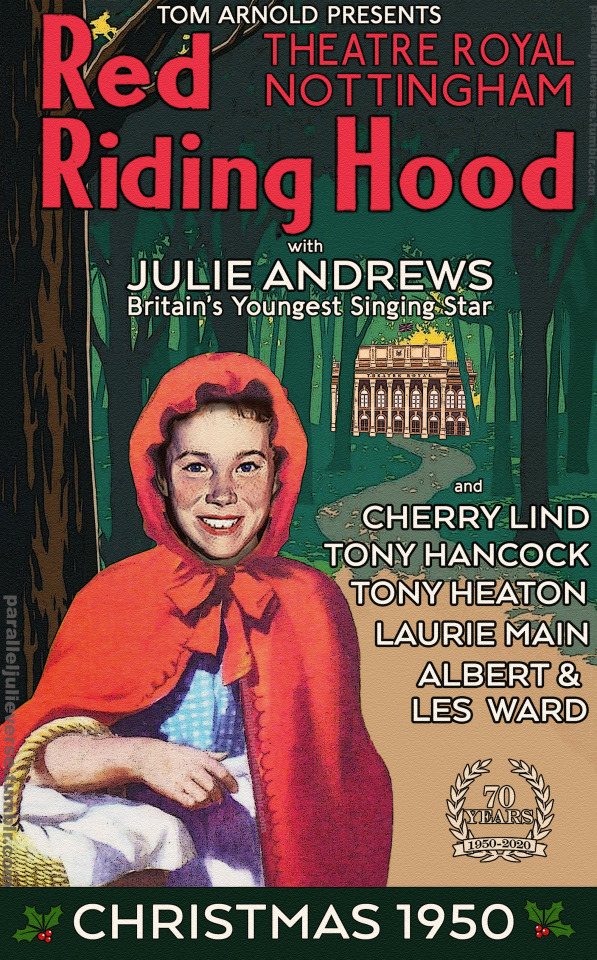

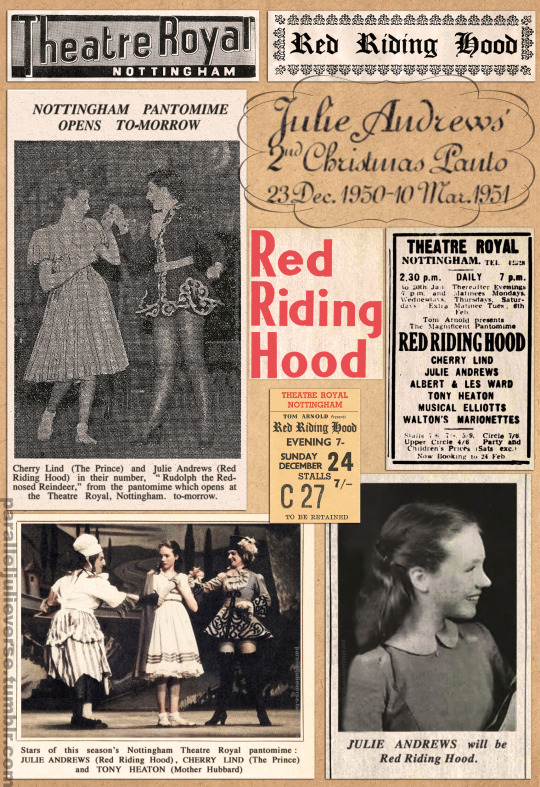

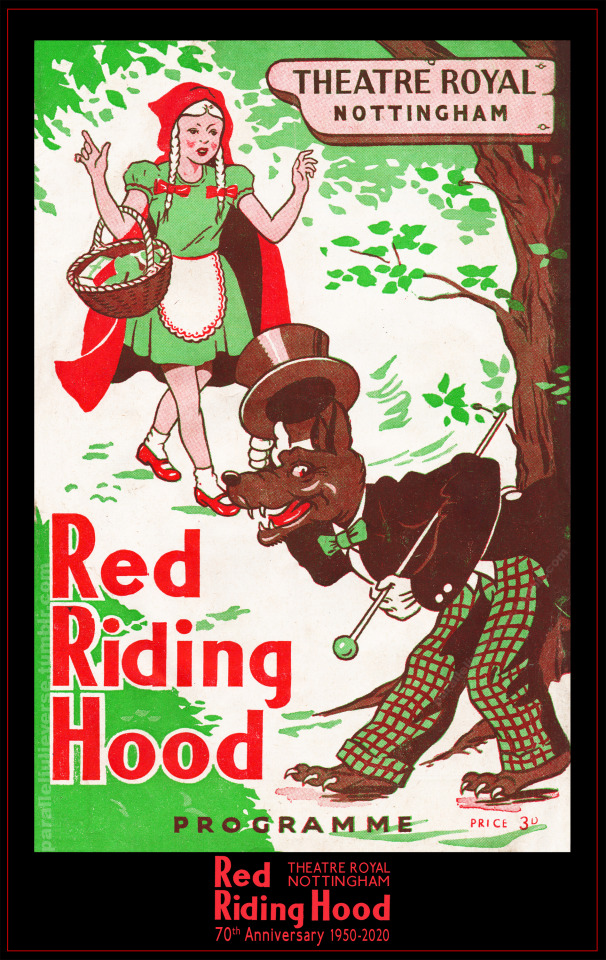

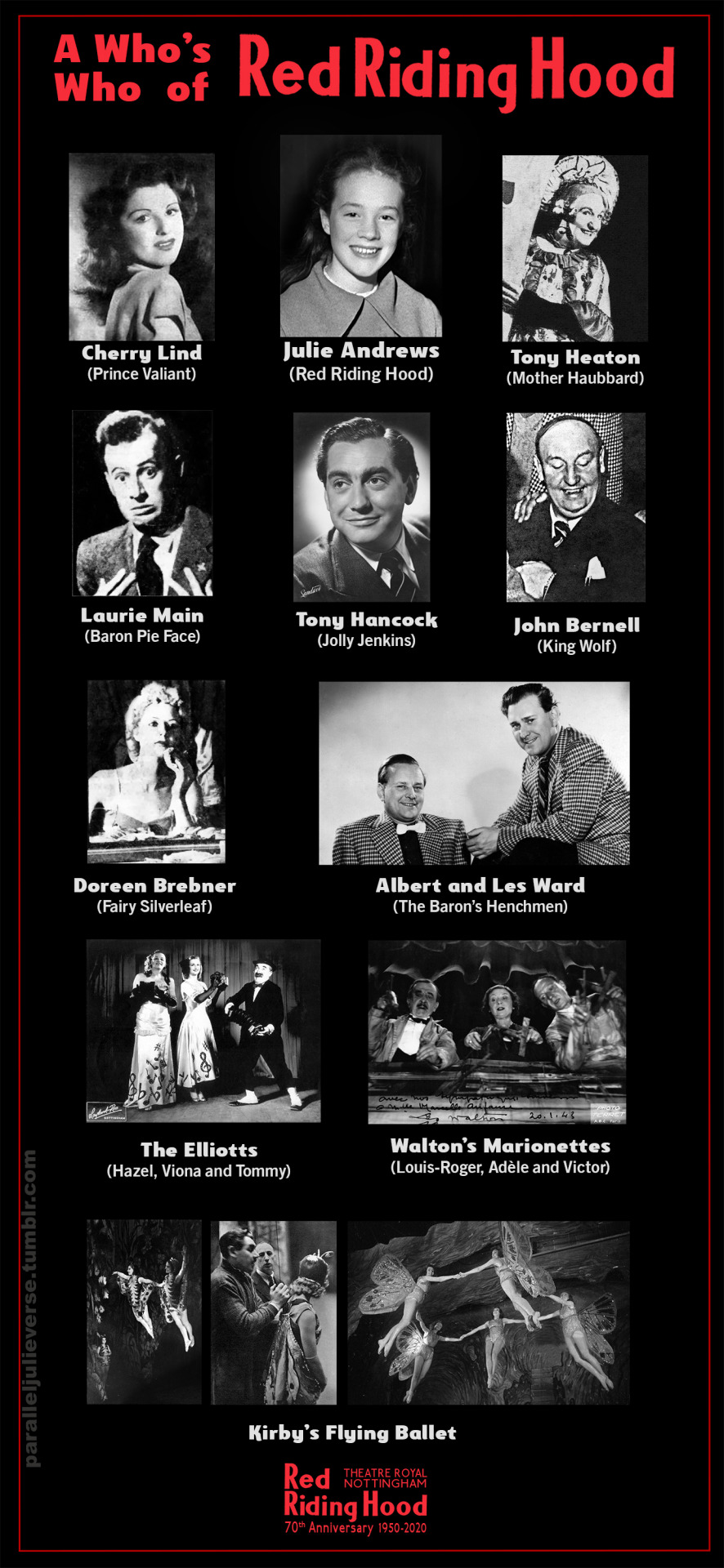

70th anniversary of Red Riding Hood

Theatre Royal, Nottingham, 154 performances

(23 December 1950 - 10 March 1951)

This week marks the 70th anniversary of another milestone event in the early career of Julie Andrews when the young fifteen-year old star opened in the title role of Tom Arnold’s lavish Christmas pantomime, Red Riding Hood at Nottingham’s Theatre Royal.

Red Riding Hood would be Julie’s second professional pantomime, following her earlier run in Humpty Dumpty at the London Casino in 1948/49. On paper, a stint at a provincial theatre might seem a downward career step after the West End, but Nottingham’s Theatre Royal was no backwater playhouse. One of the most luxurious venues of its day, the Theatre Royal opened in 1865 as a cultural monument to the booming prosperity of the East Midlands and, with convenient railway links to London, it soon became one of Britain’s preeminent touring houses, hosting repeated visits from major stars, both national and international, including Lillie Langtry, Sarah Bernhardt, Henry Irving and Anna Pavlova (Beynon, 11-13).

Moreover, Red Riding Hood wasn’t your run-of-the-mill small-town panto. It was a theatrical extravaganza produced by Tom Arnold, the foremost impresario of the British provinces. Specialising in prestigious family entertainments and theatre spectaculars, Arnold was reported to have staged over 400 pantomimes during his long career, earning him the nickname of Britain’s “New King of Pantomime” (”Personalia” 105; “King”, 11; “Obituary”, 15). The words “A Tom Arnold Production” on a pantomime poster or programme was a guarantee of first-rate entertainment with top-drawer talent and state-of-the-art production values.

The 1950 Christmas season would be one of Arnold’s most ambitious with a roster of big pantos in simultaneous production up and down the length of the British Isles including, Dick Whittington On Ice at the Empire Pool, Wembley; Queen of Hearts at the Wimbledon Theatre; Puss in Boots on Ice at the Brighton Sports Stadium; Dick Whittington at the Grand Theatre, Leeds; Humpty Dumpty at the Liverpool Empire; and Cinderella at the Alhambra Theatre, Glasgow (“Xmas Holiday Shows”, 12-21). Red Riding Hood at the Theatre Royal was the jewel in the crown with a generous budget, lavish set design, and A-list casting.

Charged with overseeing the Nottingham production of Red Riding Hood was Frank P. Adey, an enterprising young producer who had managed several earlier Arnold productions -- as well as big shows for other impresarios such as Emile Littler and Bernard Delfont -- and who would a few years later go on to helm the legendary Ocean Theatre in Clacton (Howlett, 5). Unlike today’s producers who are principally concerned with behind-the-scenes business, Adey was “a producer from the days when the title meant someone who put the whole show together from choosing the artistes, constructing the programme and lighting the scenery to directing the performers” (Hudd, 6). In the case of Red Riding Hood, he even co-wrote the script.

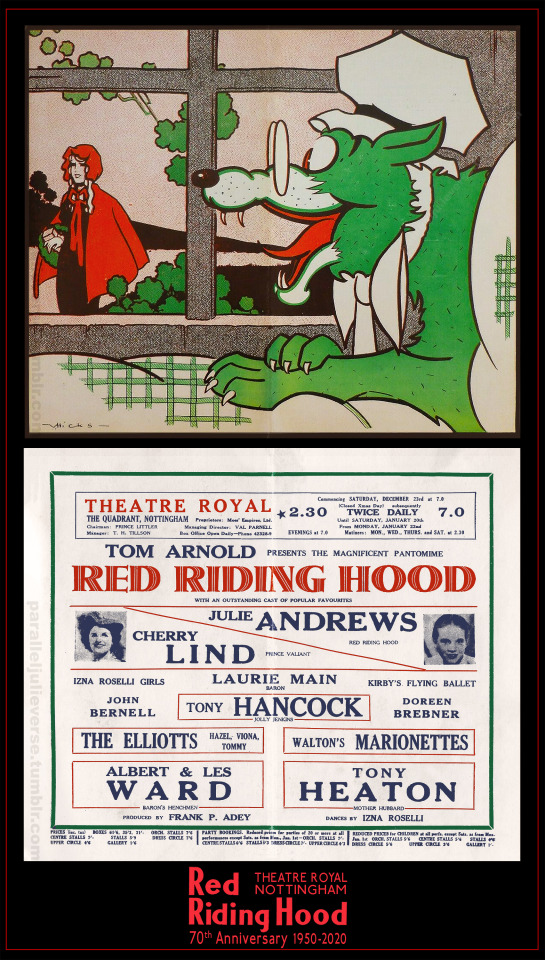

Just one year earlier, during the 1949 pantomime season, Adey had produced another version of Red Riding Hood for John Beaumont at the Lyceum Theatre in Sheffield, which is possibly why he was tapped to helm the even bigger Tom Arnold production at Nottingham (“Xmas Holiday Shows,” 1949, 15). When deciding on the cast for the 1950 show, Adey called on several of the performing talents who had worked with him in Sheffield (“Nottm.,” 6). Announced in early September, casting for the Nottingham show included:

Cherry Lind as Prince Valiant of Alluria (principal boy): A popular singer and radio personality of the post-war years, Lind had performed the “pants” role of Prince Valiant in the 1949 Sheffield production. She had also appeared previously at the Theatre Royal Nottingham in the title role of Rose Marie in 1945 (“Cherry Lind”, 5). Lind enjoyed a solid career on radio and TV into the early-60s before retiring to Brighton where she passed away in 2005 (Steel, 114-15).

Albert and Les Ward as Billy Blue and Jimmy Green (double act): This comedy brother duo were popular performers on radio variety shows of the era such as Welsh Rarebit, Variety Bandbox and Petticoat Lane. Known for their riotous “skiffle” musical performances using unconventional instruments such as washboards, bicycle pumps and spoons, the pair was cast as the comic “villainous sidekicks”, the Baron’s Henchmen, a role they had previously performed in Sheffield (“Cherry Lind”, 5; “Kings”, 24). The two brothers continued to live together in their family home in Cardiff till their deaths in 2001 and 2004 respectively (Baker, 131).

Tony Heaton as Mother Hubbard (dame): A stalwart of the British variety circuit, Heaton specialised in playing “dame” roles in pantomimes (“Dames,” 3). He had also performed this part of Mother Hubbard in the earlier Sheffield show (“Cherry Lind”, 5; “Tony Heaton”, 3). Sadly, Heaton took his own life in the sea off Blackpool in 1965 (“Drowned”, 12).

Laurie Main as Baron Pie Face of Merryvale Hall (comic): Also returning from the Sheffield production was this young character comedian from Australia who plied his trade in British variety and pantomimes throughout the 50s, before moving to the US in 1959 where he carved a solid career in theatre, film and TV till his death in 2012. As a tidbit for fans of Julie-related trivia, Main would re-team with Julie many years later when he had a brief cameo as a French general in Darling Lili (1970) (Raleigh, 5; “Laurie Main,” 11).

John Bernell as King Wolf (villain): Not a lot of information is available on Bernell, though newspaper reports indicate he made regular appearances in regional theatre productions and pantomimes throughout the 30s-50s. He had played this same role in Sheffield where he was praised as a fine stage villain with thrilling swordsmanship skills. In one of his on-stage duels with Cherry Lind, Bernell fell and fractured his wrist but, in true show-must-go-on spirit, he finished the performance before going to hospital (“Variety Gossip”, 4).

Doreen Brebner as Fairy Silverleaf (good fairy): 22-year old Brebner was a talented young ballerina from South Africa who had come to the UK under a bursary scheme. Placed under contract by dance teacher and choreographer, Izna Roselli, she did honours as the lead dancer in the Sheffield production of Red Riding Hood, supported by the Izna Roselli Girls and Kirby’s Flying Ballet. For the Nottingham show, she was ‘promoted’ to the role of the protecting fairy (”6,000 Miles”, 5).

Tony Hancock as Jolly Jenkins (comic): Last but certainly not least, the other major principal role announced in early casting was Tony Hancock in the comic part of “the silly billy, well-meaning page to the Baron” (Fisher, 102). Hancock was one of the few new additions to the Nottingham line-up, taking over a role that had been played in Sheffield by Gene Durham. Today, he is one of the most famous names in the Nottingham cast, but, at the time, Hancock was still relatively unknown. His celebrity would increase markedly the following year when he was contracted to take over the lead role of the tutor in the 1951 season of Educating Archie, before eventually proceeding to secure his own radio show and lasting fame (Fisher, 102-3).*

The one glaring omission from the early casting announcements was the title role of Red Riding Hood herself. In Sheffield, this “principal girl” role had been performed by Valerie Ashton, a young singer-dancer and stage beauty who, by all accounts, acquitted herself well enough -- “a typical and pleasing Red Riding Hood” was the verdict of one reviewer (“Spotlight”, 5) -- but a bigger marquee name was needed to helm the more expensive Nottingham production and serve as a box office draw.

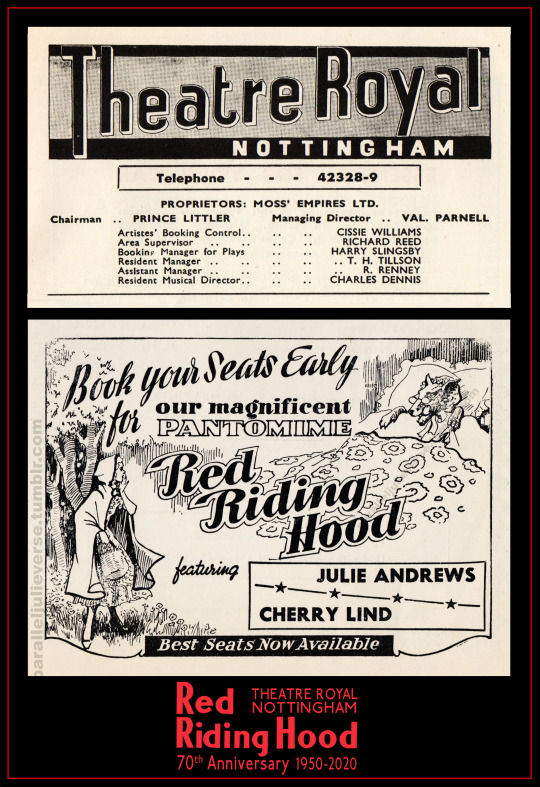

It’s not known when or how the idea to cast Julie Andrews in the title role of Red Riding Hood first emerged but, by 1950, she was a young star firmly on the ascendant. Her celebrated debut run in Starlight Roof and subsequent appearance as the youngest ever performer at a Royal Command Performance in 1948 had earned her widespread publicity as “Britain’s youngest prima donna”. While her increasing presence on radio, especially her regular stint on the hit BBC programme, Educating Archie, boosted her celebrity and helped make her a nationwide name. Julie had also worked on a previous Tom Arnold production with her 1949 summer run in Coconut Grove at the Blackpool Hippodrome, so she would have been on the company’s radar.

Either way, negotiations to secure Julie for Red Riding Hood commenced at some point in 1950. They were protracted and, one suspects, intense. Whereas casting for all the other principals was announced in September, Julie’s participation wasn’t officially confirmed till much later in November (“Julie Andrews”, 1; “More”, 5). Throughout this period, there were persistent rumours of her involvement, with one over-eager newspaper having to issue a front-page retraction after it had published a premature report in early October that the young star had been signed. “Nothing definite has yet been arranged. No contract has been signed,” it clarified, “but it is hoped that Miss Andrews will play Red Riding Hood” (“Red Riding Hood: Premature Report,” 1). In the end, a contract was signed and formally announced in mid-November, giving Julie co-star billing with Cherry Lind and, reportedly, a £200 weekly fee -- “big money then for a 15-year old entertainer in Britain” (Cottrell 57 ).

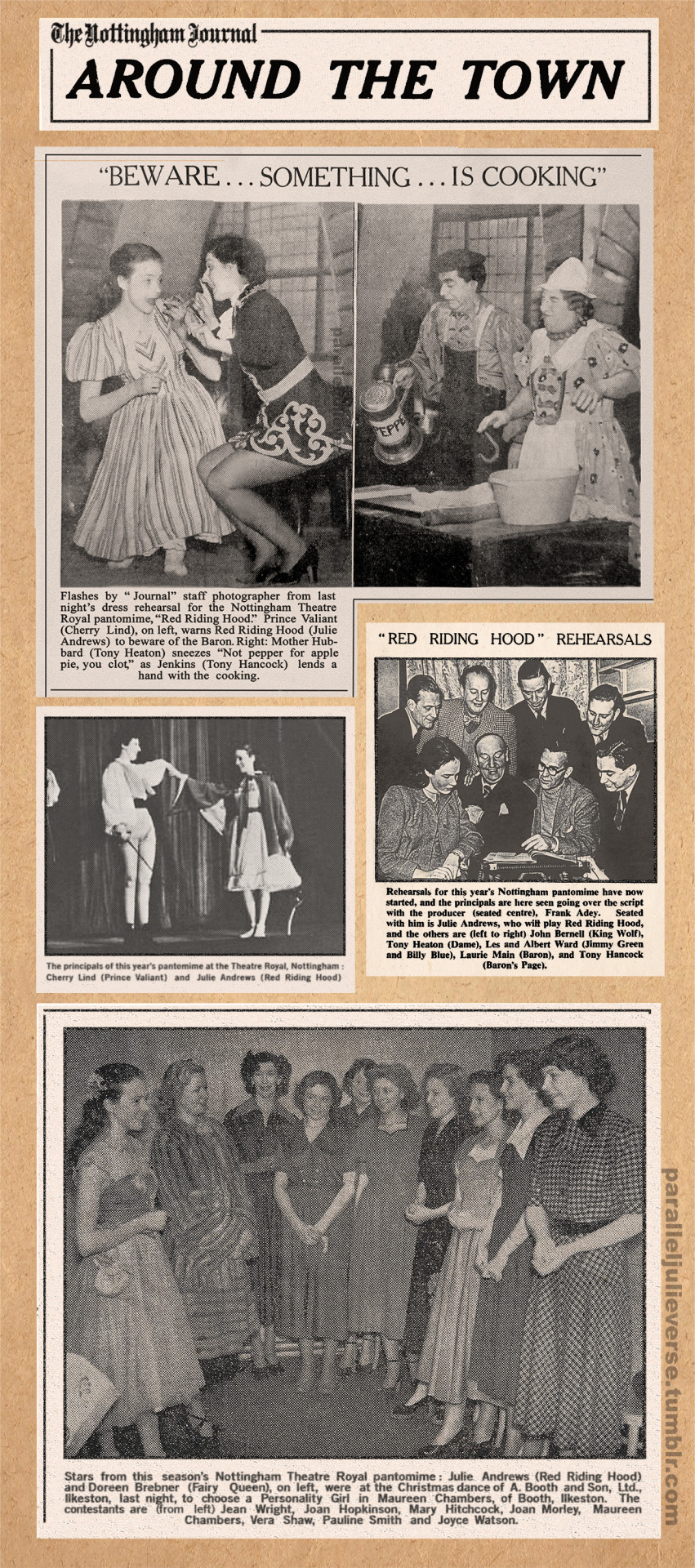

Rehearsals for the pantomime commenced on Monday 11 December with all the company and principals congregating for a script read-through, save Cherry Lind whose arrival was delayed due to a broadcasting commitment in Bristol (“Nottm. Panto. Rehearsals,” 6). Such was the level of public interest in the show that the 'table read’ was covered widely in the local and regional press. For the first week, the cast rehearsed at the Orchestra Club in Nottingham, before moving into the Theatre Royal the following Monday 18 December for on-stage rehearsals. In her memoirs, Julie recounts how her mother and aunt motored up with her to Nottingham in the family caravan where they all stayed for the two weeks of rehearsals to help Julie settle in; after which the two women returned home and Julie moved in to the Country Hotel with Cherry Lind and the other principals for the run of the show (Andrews, 129).

As was customary with pantomime, Red Riding Hood hewed to the time-honoured formula of a well-known fairy tale told with a colourful mix of music, comedy, spectacle and audience participation. By the mid-twentieth century, the received industry wisdom for mounting a pantomime was to offer something for everyone in the audience: “broad but not coarse comedy for the kids...lots of song and dance for the grown-ups, and the whole thing mov[ing] quickly from scene to scene so that no one has time to get bored” (Robertshaw, 15). This variety showcase of “events and comedy routines” was typically keyed into “the skills of the performers booked” with pantos of the era often playing “like spectacular variety shows” (Taylor, 34-35).

Producer Frank Adey, however, was of the conviction that a good pantomime needed to adhere to a well-crafted story without too many extraneous elaborations. “Everyone who comes to panto gets in to the spirit of things,” he said, “and that spirit is the story. You must not deviate and make it a revue. It must be first a pantomime and last a pantomime” (“Nottm. Panto. Rehearsals,” 6). Thus, whatever schtick individual performers were allowed was for the most part integrated into the book and showcase moments were largely played “in character”.**

With Julie in the title role -- and the equally popular singing personality, Cherry Lind as co-star -- the Nottingham production placed a premium on music and song. Indeed, Adey revised the script so that Red Riding Hood would burst into song whenever she was afraid, thereby “giving Julie ample opportunity to show her stuff” (Arntz and Wilson, 17). In classic panto style, popular songs of the day were interpolated into the score so that audiences could sing along. Thus, at one point in proceedings, Julie and Cherry Lind led the house in a rousing rendition of the newly minted Christmas hit, “Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (Stevenson, 3). Other popular standards featured in the show included: ‘If You Feel Like Singing” and the Flanagan and Allen hit, “Hey, Neighbour”(Stevenson, 3). However, Adey also revived the “earlier pantomime tradition” of featuring classical music by “composers such as Tschaikovsky...Offenbach, Edward German and others” (ibid.). In this way, Julie got to air her classical training by singing “amongst other things the 'Waltz Song' from Tom Jones with its many trills” and ‘The Gypsy and the Bird' by Sir Julius Benedict (Stevenson, 3; see also Andrews: 130).

The final dress rehearsal for Red Riding Hood took place on 22 December in front of a charity audience of over 550 children from local care homes and hospitals (“Night of their Lives,” 2). Newspaper reports described that the excited children “oohed and aahed” and “gurgled with glee” and “gasped at their first view of Fairlyland,” noting that:

“A special cheer was reserved for the first entrance of Red Riding Hood. Miss Andrews, only a few months older than the oldest of the children, showed her gratitude by singing to them..with a voice like silver” (“Night of their Lives,” 2).

Once the show had officially opened on 23 December, press reviews were similarly appreciative:

The Nottingham Journal: “Cherry Lind and Julie Andrews...are the best principal boy and girl whom Nottingham has had for many a long year. Both have delightful voices -- Julie’s being phenomenal” (Stevenson, “Showpiece,” 4).

The Nottingham Guardian: “Principal Boy Cherry Lind and Principal Girl Julie Andrews have youth and lovely voices to help them make their parts everything they should be. Julie Andrews’s voice especially is astonishingly good -- good for a singer of any age, astonishing because she is only 15...We can’t all sing like Julie Andrews, but the next best thing when mid-twentieth century conditions become a little too fearsome is to go and hear her and escape for three hours to the world of pantomime” (“Emphasis on Tradition”, 5).

The Nottingham Evening Post: “Red Riding Hood is everything it should be...Principal Boy Cherry Lind and Principal Girl Julie Andrews make the most charming pair...They, with Archie Stanton conducting the theatre orchestra, attend to the music and the heroics” (“Nottm. Panto. Sticks,” 1).

The Nottingham Evening News: “It would be necessary to go back many years to find a principal boy and girl equal to Cherry Lind and Julie Andrews. Both have lovely voices but, because of her age, Julie’s is phenomenal. Who would expect to hear the soaring notes and the trills of a coloratura soprano coming from the throat of a fifteen-year-old who looks ‘that nice youngster from next door’. Their duet ‘Your heart and My Heart’ is one of the the most delightful things imaginable” (WBS, 1).

The Football Post: “This year’s show is firmly based on tradition and is packed with action, colour, spectacle, song and dance. Cherry Lind as the Prince and Julie Andrews as Red Riding Hood make an admirable couple, and they are supported by a strong comedy team (“Pantomime Keeps,” 11)

The Stage: “Frank P. Adey is this year giving Nottingham the most lavish pantomime it has seen for a good many years...Red Riding Hood has all colour, melody, melodrama and well-known jokes and situations that have always delighted children -- and their parents -- but a little more emphasis is laid on the melody and song than is perhaps usual. And it is natural that this should be so, for Cherry Lind and the young Julie Andrews, in addition to making a very charming Prince and Red Riding Hood, show that they have two of the sweetest voices heard in Nottingham for a long time” (“Xmas Holiday Shows,” 1950, 15).

The glowing reception of Red Riding Hood extended equally to audiences. Ticket sales were excellent and the show played to capacity houses. Coach and rail tours brought a steady flow of group bookings from near and far. Red Riding Hood “continues its triumphant course at the Theatre Royal, Nottingham,” noted one newspaper report in mid-January, “with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of patrons queueing to see Cherry Lind...and Julie Andrews” ( “New Revue,” 11). Audience demand was so strong that the show was extended several times beyond its original closing date of early February (“Panto. Extended.” 11). The run was initially extended till 3 March, after which it was extended a further week, finally closing on 10 March after 154 performances.

Notes:

* Quite a few commentators suggest erroneously that Julie and Tony Hancock already knew each other prior to Red Riding Hood due to the fact they had worked together on Educating Archie (Stirling, 38). Even Julie makes the claim in her memoirs: “Since he [Hancock] had performed in Educating Archie, I knew him a little and liked him, although we hadn’t had much connection on the radio show” (Andrews, 131). However, Tony Hancock didn’t start performing in Educating Archie till the second series in August 1951, many months after the end of Red Riding Hood.

** I say “for the most part” because Red Riding Hood did include an extended "interval” where the popular local specialty act, the Musical Elliotts, did a comic virtuoso turn playing miniature concertinas, followed by another family troupe, Walton’s Marionettes, who put on a puppet show, but this interlude was designed largely as a self-contained “show within a show” that gave the main cast -- and the audience -- a breather between acts (Stevenson, 3).

Sources:

“6,000 Miles From Home.” Sheffield Daily Telegraph. 14 January 1950: 5.

Andrews, Julie. Home: A Memoir of My Early Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008.

Arntz, James and Wilson, Tom. Julie Andrews. Chicago, IL.: Contemporary Books, 1995.

Baker, Richard A. Old Time Variety: An Illustrated History. Barnsley: Remember When, 2011.

“Beware Something is Cooking.” The Nottingham Journal. 22 December 1950: 5.

Beynon, Robin, ed. The Theatre Royal Nottingham, 1875-1978: A Theatrical and Architectural History. Nottingham: Nottingham City Council Theatre Royal Sub-committee, 1978.

“Cherry Lind Stars in Nottingham Pantomime.” The Nottingham Journal. 12 September 1950: 5.

Cottrell, John. Julie Andrews: The Story of a Star. London: Arthur Barker, 1968.

“‘Dames’ Win Praise.” The Star Green 'Un. 7 January 1950: 3.

“Drowned Comedian Faced Arrest.” The Guardian. 28 August 1965: 12.

“Entertainments: Lyceum Theatre Sheffield.” Derbyshire Times. 22 December 1949: 10.

“Emphasis on Tradition in ‘Red Riding Hood.” The Nottingham Guardian. 27 December 1950: 5.

Fisher, John. Tony Hancock: The Definitive Biography. London: HarperCollins, 2008.

Howlett, Sue. “Frank of the Ocean Calls It a Day.” Clacton Gazette. 6 May 1977: 5.

Hudd, Roy. Roy Hudd's Book of Music-hall, Variety and Showbiz Anecdotes. London: Robson Books, 1994.

“Ilkeston Firm’s Event.” The Nottingham Evening Post. 16 December 1950: 1.

“Julie Andrews Will Be Red Riding Hood.” The Nottingham Journal. 22 November 1950: 1.

“Variety Gossip: John Bernell.” The Stage. 16 March 1950: 4.

“The Jones Family Goes to Fairyland.” The Nottingham Journal. 23 December 1950: 3.

“King of Pantomime Dies”. The Illustrated London News. 8 February 1969: 11.

“Kings of the Washboard: Albert and Les Ward.” The Hampshire Telegraph. 6 December 1957: 24.

“Laurie Main, Narrator on TV’s ‘Welcome to Pooh Corner,’ Dies at 89.” Hollywood Reporter. 16 February 2012: 11.

“More about Theatre Royal Panto.” The Nottingham Evening Post. 20 November 1950: 5.

“New Revue for the Nottm. Empire.” The Football Post, 13 January 1951: 11.

“Night of their Lives: Children at Panto. Dress Rehearsal.” The Nottingham Evening Post. 23 December 1950: 2.

“Nottingham Bill of Christmas Entertainment.” The Football Post. 23 December 1950: 11.

“Nottingham Dancers in Pantomime.” The Nottingham Journal. 12 December 1950: 3.

“Nottingham Panto Principals.” The Nottingham Evening Post. 4 December 1950: 1.

“Nottm. Panto. Principals.” The Nottingham Evening Post. 11 September 1950: 6.

“Nottm. Panto. Rehearsals Begin.” The Nottingham Evening Post. 11 December 1950: 6.

“Nottm. Panto. Sticks to Tradition.” The Nottingham Evening Post. 26 December 1950: 1.

“Obituary: Tom Arnold.” The Stage. 6 February 1969: 15.

“Panto. Extended.” The Football Post. 3 February 1951: 11.

“Panto King, Tom Arnold, is Dead.” Daily Mirror. 3 February 1969: 5.

“Pantomime Forecasts.” The Stage. 24 November 1949: 8.

“Pantomime Keeps Christmas Spirit Going.” The Football Post. 30 December 1950: 11.

“Personalia: The New King of Pantomime.” The Sphere. 20 April 1935: 105.

Raleigh, H.M. “The Repertory Theatre: Talented Players at Sheffield.” Yorkshire Post and Leeds Mercury. 24 June 1950: 5.

“Red Riding Hood: Premature Report.” The Nottingham Evening Post. 3 October 1950: 1.

“‘Red Riding Hood’ Rehearsals.” The Nottingham Evening Post. 11 December 1950: 1.

Robertshaw, Ursula. “Bo-Peep in Bath.” The Illustrated London News. 6 January 1968: 14-15.

“Spotlight on Entertainment.” The Derbyshire Times. 13 January 1950: 5.

“Stars from this Season’s Nottingham Theatre Royal Pantomime.” The Nottingham Journal. 20 December 1950: 1.

Steel, Tracey. “Whatever Happened to...?” Evergreen: A Miscellany of This & That & Things Gone By, Summer 2019: 114-15.

Stevenson, Bernard. “Stage and Screen: Panto in Full Swing in Nottm and District.” Nottingham Evening News. 30 December 1950: 3.

Stevenson, W.B. “Showpiece: First Red Riding Hood since 1919.” The Nottingham Journal. 12 September 1950: 4.

Stevenson, W.B.“‘Red Riding Hood’ in Tradition.” The Nottingham Journal. 23 December 1950: 3.

Stevenson, W.B.“Showpiece: Hot Music or ‘H.P.’” The Nottingham Journal. 27 December 1950: 4.

Stirling, Richard. Julie Andrews: An Intimate Biography. London: Portrait, 2007.

Taylor, Millie. British Pantomime Performance. Bristol: Intellect Books, 2007.

“Tony Heaton.” The Stage. 2 September 1965: 3.

W.B.S. “A Grand Panto: Red Riding Hood opens in Nottm.” The Nottingham Evening News, 26 December 1950: 1.

“Xmas Holiday Shows.” The Stage. 30 December 1949: 12-21.

“Xmas Holiday Shows.” The Stage. 29 December 1950: 12-21.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2020

#julie andrews#red riding hood#pantomime#christmas#theatre royal#nottingham#british theatre#1950#theatre history#70th Anniversary#panto#the parallel julieverse

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Whenever I'm feeling unhappy, I just try to think of nice things.”

- Maria (Julie Andrews), The Sound of Music (1965)

#julie andrews#covid-19#My Fair Lady#camelot#cinderella#mary poppins#the sound of music#humour#classic film#Broadway#musicals#hollywood#the parallel julieverse

201 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From the PJV Archives: It’s Behind You!

Publicity photo taken during rehearsals for the Royal Command Variety Show at the London Palladium in November 1947. Pictured is Val Parnell (far right), chief of the Moss Empires theatre chain and producer of the Command Variety Show, with the show's headliners, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, and the Crazy Gang (Bud Flanagan, Jimmy Nervo, Teddy Knox, Charlie Naughton, and Jimmy Gold).

It’s an amazing line-up of comedy royalty, to be sure, but what intrigues us even more is the poster in the background advertising another Val Parnell show that had only just bowed at the London Hippodrome. There a young 12-year old soprano was stopping the show every night. She would do the same the following year at the Royal Command Variety Show of 1948.

#julie andrews#royal command variety show#val parnell#laurel and hardy#the crazy gang#bud flanagan#jimmy nervo#teddy knox#charlie naughton#jimmy gold#london palladium#theatre#1947#the parallel julieverse

1 note

·

View note

Photo

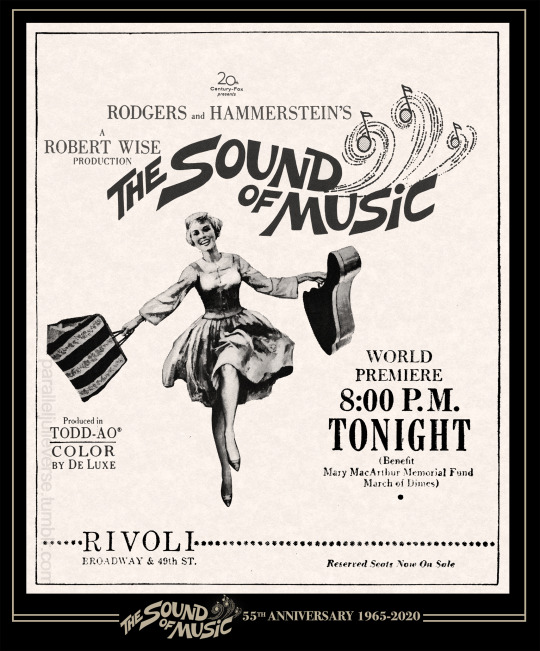

This Day in Julie-history...

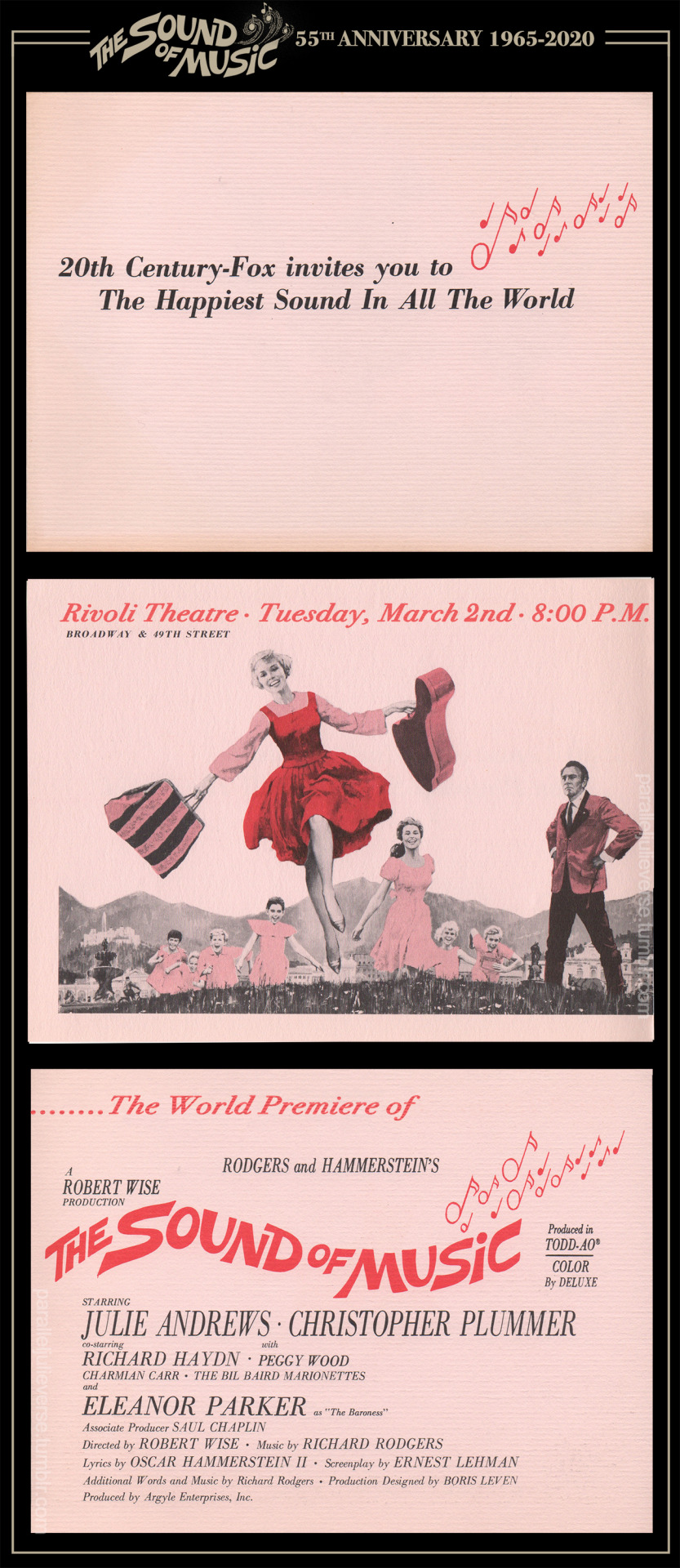

Fifty-five years ago, The Sound of Music made its triumphant premiere at the Rivoli Theatre in New York, 2 March 1965...and the world has been singing ever since.

#julie andrews#the sound of music#film premiere#rivoli#new york#1965#film history#classic film#the parallel julieverse

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

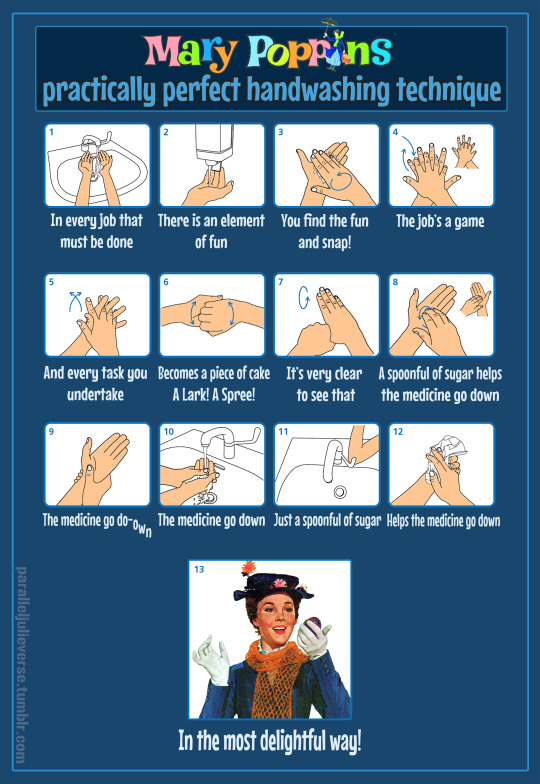

How to keep those hands spit-spot clean and virus-free!

#mary poppins#julie andrews#spoonful of sugar#handwashing#the parallel julieverse#walt disney#classic film

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

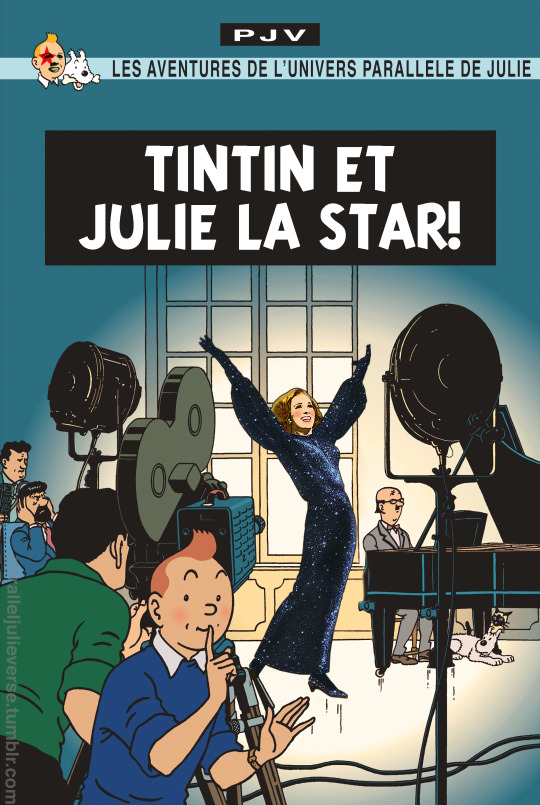

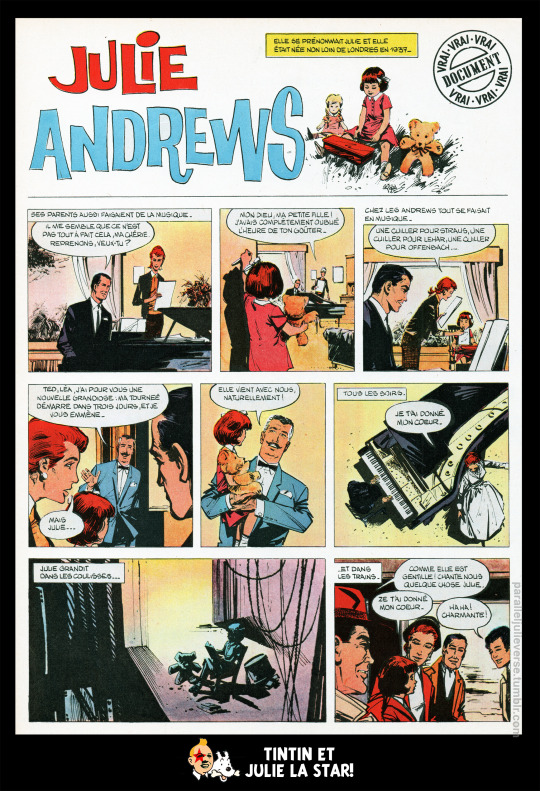

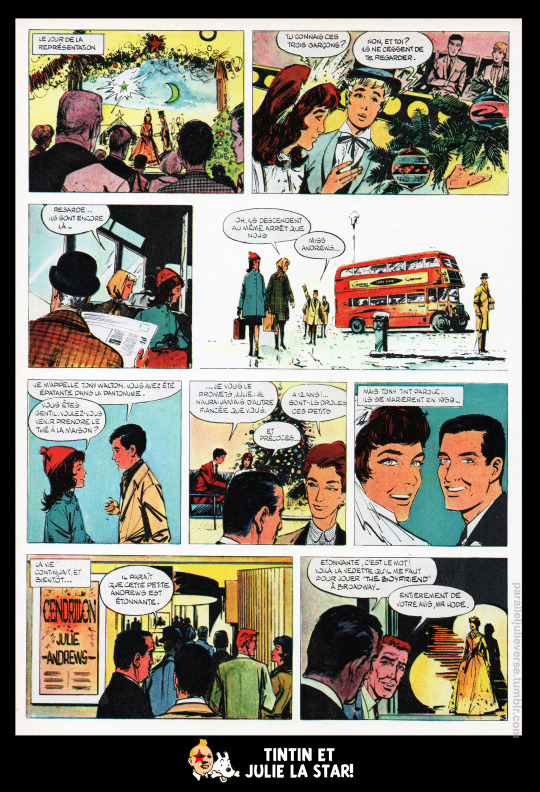

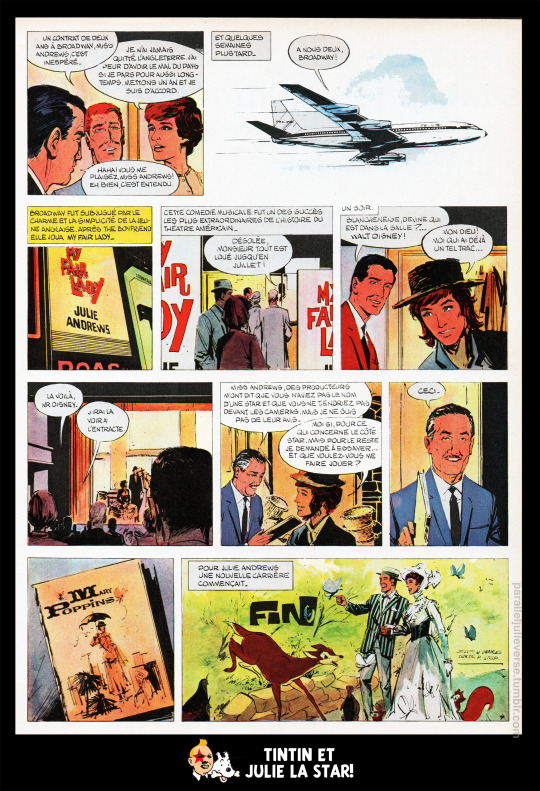

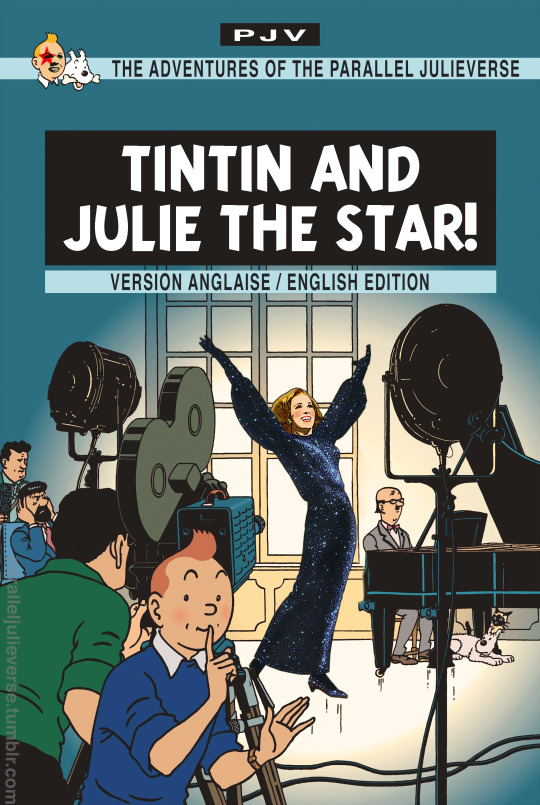

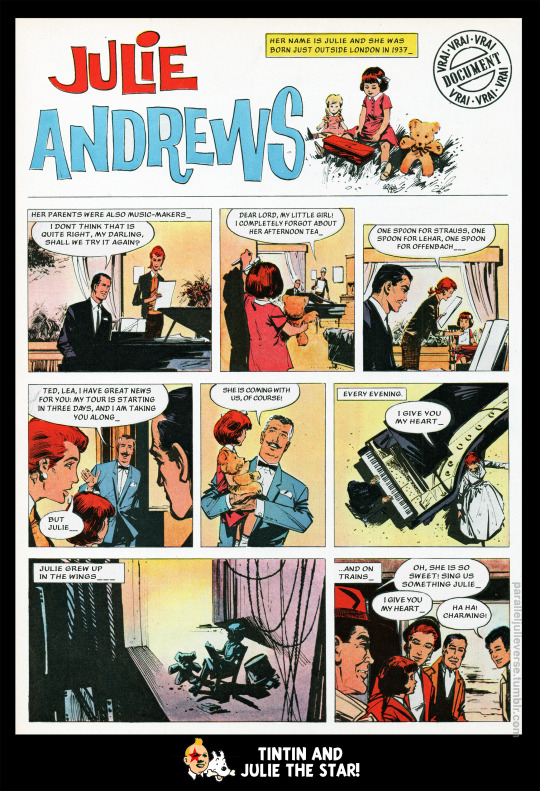

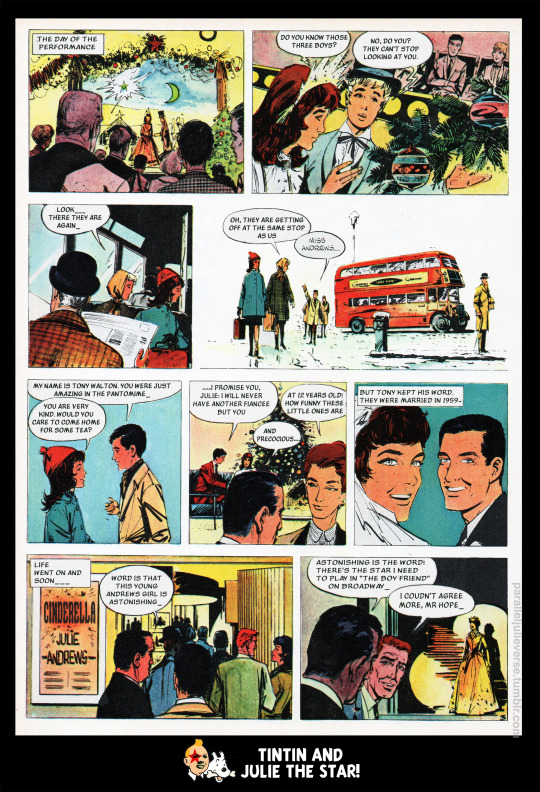

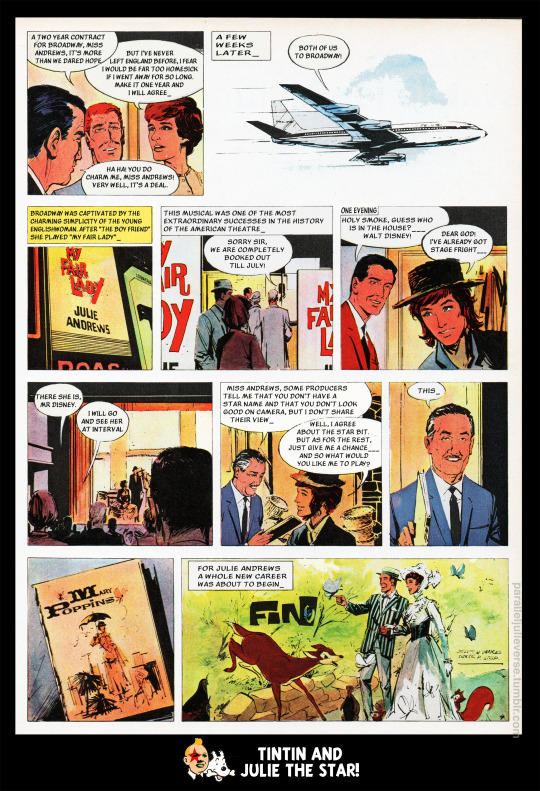

Sometimes truth is stranger than fiction. For example, did you know that Julie Andrews appeared in a Tintin comic? Well, she did...at least, sort of!

In 1967, Le Journal de Tintin -- a popular Franco-Belgian weekly devoted to Hergé’s beloved boy-detective -- published a four-page “comic” version of Julie’s biography. The magazine would often run such miscellaneous pieces alongside material on Tintin and other serialised comics. With images by up-and-coming Belgian cartoonist, William Vance, and text by Pierre Step, the comic biography of Julie covers her early career from childhood to global film stardom with Mary Poppins.

As drawn, the figures don’t exactly look much like their real-life counterparts and the story takes more than a few poetic liberties with the truth: Julie’s year of birth is two years out; her mother, Barbara, is rechristened Lea and depicted as a classical singer while husband, Ted, is made her pianist; Julie’s beloved singing teacher is cast as a discouraging shrew; Vida Hope is given a sex change; and Walt Disney visits Julie during a performance of My Fair Lady rather than Camelot...but, hey, The Sound of Music wasn’t exactly true to the historical record either, so all’s fair in art and fantasy!

If naught else, this curious little piece tucked away in a popular Belgian comic-book attests to the extraordinary global reach of Julie’s stardom during its heyday of the 1960s. The comic is offered here both in the original French and in an English translation done by the Parallel Julieverse -- with due apologies to Molière, Proust...and Miss Jeannie Banks!

Source:

Step, P and Vance, W., “Julie Andrews”, Le Journal de Tintin, no. 964, 11 April 1967:51-55.

#julie andrews#tintin#comic#star#england#france#mary poppins#Child Star#Broadway#hollywood#classic film#the parallel julieverse

51 notes

·

View notes