#thracian culture

Note

Do you know much about Thracians and their worship of Ares?

I have scarce knowledge about the Thracians so I had to do some research about their religion and.... they did not worship Ares??? The Thracian religion had two deities, a female one (Bendis) and a male one (Zis) and then a demigod (Zalmoxis / Orpheus). These deities encompassed all the qualities traditionally associated with their sex, so Zis was a father god and he had multiple sides to him, he was celestial, chthonic, a hero, a hunter, a royal ancestor of humanity and a warrior. Warrior Zis took a wolf-like appearance and was riding a horse. He was often described in the Thracian language as "bestial".

There is something in ancient literature described as interpretatio graeca, which means that a load of info we have about ancient cultures come from the descriptions of the Greeks and not the other ancient cultures themselves. In this case, Herodotus wrote about the Thracian religion and it is believed his works are a prime example of interpretatio graeca as he was trying to make the foreign religion easily comprehensible to his contemporary Greeks. So, Herodotus would say things like "this is their Ares", "this is their Artemis" and so on. However, the structure of the Thracian mythology appears quite different from the Greek one, especially in its origins.

What could also perplex matters is that Greeks from their side considered the Thracians descendants of Ares, because they were renowned warrior people, but that doesn't mean Thracians worshipped the exact "Ares" Greeks had (and barely even worshipped).

This is an interesting difference. The warrior quality is given to the Thracian father god. Greeks reserve this role for the father god's son who was not all that worshipped either. While Greeks really admired good warriors either among themselves or in other nations, they did not acknowledge themselves as appreciative of the frenzy of war and this is even reflected on how often gods, even Zeus, appeared to dislike and avoid Ares. On the contrary, it is clear that Greeks considered Athena as their primary deity of war, since they viewed themselves as supporters of the defensive war or the war that is inescapable or fully justified or a war that is based on strategy and the evaluation of cost and benefits rather than the wild manly joy or sheer force that was associated with war in some ancient cultures. Furthermore, Ares is portrayed as a young, handsome and strong warrior who however has an unpleasant attitude and does not possess many heroic qualities. So the worship of warrior Zis and the, well, more lukewarm worship of Ares were different.

However, Greeks extensively moved and settled north and a few Thracians did move south (some became mercenaries in Greek armies) and at these points their myths were blending a lot. Usually there are significant differences in the various tellings but there is also a lot of overlap. After the Greco-Thracian interaction, it was often that Thracians would use Greek equivalent names to address the aspects of their gods more easily, so if they wanted to talk about the warrior Zis, they might have said, "Ares". But he was actually a different god.

#mythology#greek mythology#ares#thracian mythology#zis#hopefully i am not super wrong#ancient cultures#greek culture#thracian culture#anon#ask

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

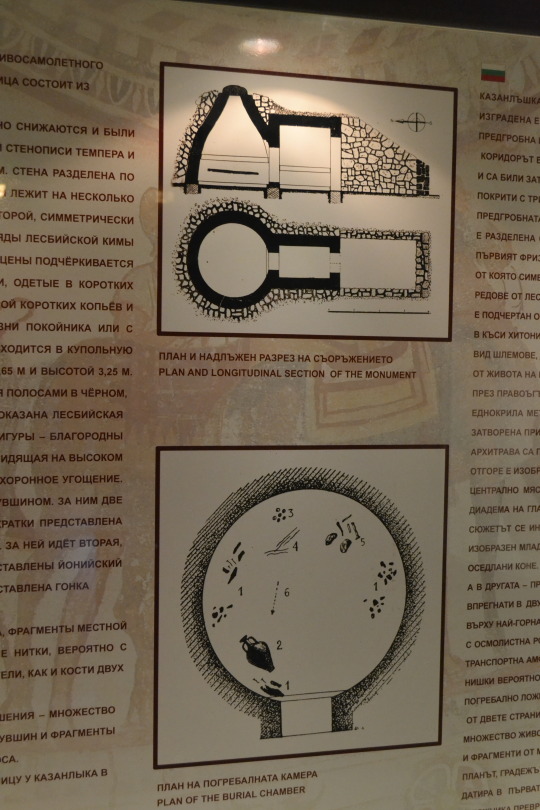

Bulgarian Kazanlak Ritual

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Greco-Thracian Gold Bracelet with Beast Heads

Ca. 400-300 BC

A stunning rare gold bracelet of penannular form, with a flat-section, carinated body decorated with incised motifs to the shoulders. Each finial ends in a horned head of a beast with incised eyes, a pronounced nose, and a mouth. The horns are adorned with intricately ribbed rings.

L:61.5mm / W:60mm ; 51.16g.

#Greco-Thracian Gold Bracelet with Beast Heads Ca. 400-300 BC#ancient jewelry#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient rome#roman history#roman empire

664 notes

·

View notes

Text

ooc. caution: this is very long under the cut. but here's the first half of the story i wrote back in 2021 for alectryon. granted, with the other canon characters in this, take my writing with a grain of salt lol ( also the history, it might be iffy ) it does not need to apply to them if you don't want it to, this is just to give an idea of how i'm going to write alectryon / his story if anyone wants to write with him c: the only warning is animal death at the beginning because hunting.

I.

The elders all told of a giant boar ravaging through the wild forest of the Haemus mountains north of their tribe. It had been noted to terrorize animals, leaving bloody tracks and rotted corpses that other hunters came upon, leaving food sources scarce. Nearby tribes were experiencing the same problem with this beast, mad with bloodlust as it were a monster birthed within their midst as punishment from the gods. It needed to be put down, regardless. There was a chance that it could leave the forests for the fertile plains, bored of small animals, and instead graduate to small children.

Thus, there was a reward to whoever did put an end to its madness, but while many attempted, none were successful. When a prized hunter of the Triballi tribe came back with a gored leg, which needed to be amputated lest he succumb to death’s gentle touch, made for any last-ditch courageous offer to slowly vanish into uncomfortable silence.

But Alectryon held the vigor of youth, where some may say was cause for stupid and rash actions, he did not see it as such. With bow in hand, knife upon his belt, he made his way to the mountain pass. It was a day’s ride to the boundary line of the forest, but he camped just outside of it with his horse nearby. There was no doubt in his mind that the boar was out there, the screaming squeal of the beast echoed through the night. But goddess Nyx blessed him with cover, allowing him to wake up in the early morning fog to continue his hunt alive and well.

His step was light as he made his way through the thicket, barely rustling the foliage underfoot as birds chittered around him, unbeknownst to the terrors that was wrecked below their branches. He brought his bow to hand and nocked an arrow to the string. His horse was left behind to graze, but he wondered if he should have taken it with him the more he walked, finding nothing but trees and shrubbery. But he had to keep his wits about him. Wars were one thing, where the carrion and the smell of its rotted flesh sought to strip the cords of sanity within his mind, the hunt was merely the thrill of the wait. Patience was necessary. With a deep inhale and a slow exhale, he persisted, keeping track of where he was at and how long it had been.

A crazed squeal was heard in the distance, echoing through the woods. Alectryon perked up, glancing towards the east before changing his path to favor that direction. He knew he was getting closer as he began to hear the snarling grunts get louder and louder. To hunt any kind of boar, crazed or not, the element of surprise was a must. To bring attention to oneself might make other animals flee, but with a boar it would simply charge the hunter. The faster he was at taking down this beast, the better chance of coming out unscathed.

As the sounds of hooves upon dirt and the rustle of leaves came to his ears, his feet picked up in a run. Swift as he was, his eyes were like that of an owl’s in the dark of night as they darted around in his sockets, quick to make sure that he could spot the beast before it spotted him. Death was not for him today. Thanatos’ blade was stayed at his neck as he eyed the short brown tail of the massive boar, snarling and foaming at its white-tusked mouth.

Sliding soundlessly to his knees, he aimed his bow from the cover of a bush. He felt an invigorated strength latch onto his arms (like a pair of hands gripping him tightly) as he pulled the bowstring taut and released, letting his arrow slice through the air before stabbing the beast’s hind leg. It roared a terrible sound; the whites of its eyes grew larger as its breathing puffed out like smoke into the air. Before Alectryon could get a new arrow and nock it to his bow, the boar ran. With a silent curse, Alectryon sprinted after the frantic wild thing. His legs were given the power to remain in sight of the boar. Taking his bow up again, he shot, but the arrow only pierced the beast’s right ear, serving only to enrage it further. So much for that surprise.

A glimpse in his peripheral had him looking away from the boar for a second to spy a figure in Hellene wear running alongside him. Red eyes flashed. But the boar pushed behind thorn tipped bushes and before it could get away, he vaulted over them. An unexpected turn for the beast who sought the solace of the foliage’s protection. It was limping now, crimson blood wetted brown fur. The beast sweated and panted, frothing at the mouth as it dug its hoof against the ground to create a cloud of dust. A cave was behind it, blocking any further progress, so now it was a chance to fight. Large as it was, dwarfing even Alectryon who did not wait to launch another arrow at it, piercing its neck.

He would have been surprised if that were it. Instead, the fear and anger the boar felt was now turned on Alectryon. Despite the limp, it charged. Alectryon had a second to dodge the tusks aimed for his stomach, but he twisted away with a light stumble. His bow was cumbersome now. He put it across his shoulders and pulled out his knife before the boar charged at him again, but he was not quick enough. The tip of its tusk ripped through his tunic and dragged against his skin. Pain barely felt, he took the close proximity for his own benefit and shoved his knife deep into its side. The boar felt it, screaming in pain now, but Alectryon held on as the beast shot away, allowing his knife to drag along its tough flesh until he pulled it out once he hit the thigh bone.

Alectryon, breathless, turned around to watch as the beast’s innards poured out of it, giving sacrifice to the very gods of this land. Stinking and steaming against the cold ground—but it did not fall. Not yet. It bucked and reared, squealing and grunting in the effort to get away from the harm. But there was no hope for it. Its tyrannical reign of the forest was at its end, and with one last snort, it crashed with a dull thud. Slowly, with twitching limbs, the light of life vanished from its wide black eyes. Alectryon stood over the corpse and closed his eyes, letting out a breath of relief before placing his hand upon its fur. He gave his thanks for the meat that will feed a tribe which once feared this very same beast.

Opening his eyes, he let out a breath that caused a sharp pain to jolt through him. He glanced down at the tear in his tunic before peeking in to find blood coming out faster than he would have liked—drenching his side in the process. “No,” he wheezed, dropping to his knees. “Not now.” Taking off his cloak, he was about to rip it into a tourniquet before a powerful grip stopped him from doing so. Anger blossomed, but fear came in the shape of a hand covering his eyes while another grasped his wound tight. He gritted his teeth, whimpering against the pain before the hands were taken away. Eyes opened to a flash of red and then nothing. Only he and the boar remained still. He glanced at where his wound should have been, but upon his tanned skin was a line of healed, raised flesh.

Blood dripped from his face to the ground, startling him. He reached up, finding that where the stranger’s hand laid upon him, there was blood left in its wake. Metallic smelling with the odd heady aroma of a sweet concoction. The latter scent confused him as he turned around in hopes of finding the stranger, but he still came up empty. With it, he felt a sudden loss, but he had to shake himself out of those thoughts before the insects on the ground take their hold on the corpse and mark it as their own.

Taking his cloak now, he laid it on the ground and began to pile its innards in the middle of it. Then, with his knife, he began to skin the corpse. He was careful to make sure that there were no extra cuts in the pelt, using the techniques his mothers had taught him before he was ready to move onto cutting out the meat. The meat he gathered was stacked on top of the innards that he then wrapped up in the cloak, tying it up once full. Tusks, legs, and the fur pelt were all carried with one hand, while the other began to drag the makeshift bag. It would be a slow journey, but this was his only way, fearing that animals would pick apart the bag before he had a chance to get his horse.

Alectryon felt a touch upon his arm, strength flowed into him and the bag was lifted by his own hand. He saw no one. He had no explanations, but he also did not want to question a good thing. Thus, with renewed energy, he towed his prize out of the forest and to where his horse remained, grazing still upon the verdant grass of the welcoming plains. The sun was already dipping close to the horizon line, but the orange glow of the evening sky welcomed him with a warm embrace. He could breathe easy now.

Setting his prize down, he made to get his horse back to saddle it and place the makeshift bag upon the back of it. Using rope, he tied down the rest on top. Before long, he was away, and he wanted to make the journey back as fast as he could. Proud as he was, he more so wanted to tell the elders that there was no need to worry anymore. There was a certain type of feeling that he loved when those he cared about were relieved—that he had a hand in their content. He smiled against the wind as he closed his eyes, letting the dying heat of the sun wash over him one while his horse sprinted home.

II.

“Did you hear about Princess Polyphonte?” Strymon asked as he hung over the wooden fence that surrounded the horse pen. A shock of red hair puffed up from his head like smoke with blue eyes always squinting against the bright sun. He was someone who never really seemed to change aside from growing taller as he aged. His face was still round, making him look more like a boy than the man he was. At one and nine, perhaps that was not all too far off, at least in the eyes of the elders.

Alectryon glanced at his friend, switch in hand while in his other was a rope tied loosely to a young, black stallion’s neck which was trotting around him in a circle. He moved with it in a slow turn, keeping watch as the horse yielded to his commands. Well, most of them. The horse was yet to be fully broken in to allow someone to ride it safely, but Alectryon was seeing the progress enough to find some merit to having bought the horse. “No…I thought she ran away with the hunters of Bendis? At least, that was last I heard about it since she didn’t want to marry that one guy, Ister from the Dii tribe. Though, I don’t blame her—he was a bit of a bastard.”

“Think she wanted more than a bastard from what I hear,” Strymon said before Alectryon frowned at him in confusion. “So, she did run off with the hunters, right? But apparently, she fell in love with a bear while out there with them. Not sure how that happened… The bear must’ve been a smooth talker.” A snorted giggle came out of him then.

“Is this another one of your jokes?” Alectryon asked, face deadpanning. He knew Strymon to be one of grand imagination who always cracked jokes at whatever filled his mind for that day. Every time they were together, he would tell stories from the top of his head. A highlight at the tavern for the patrons, but Alectryon had heard it all ten times over. This one was new though, he had to admit, nor was it like any of his other stories.

“I wish it was.” But never did Strymon act this way while telling these stories of his. He never passed them off as the truth, but merely to entertain for a moment or two. This time was different, which confused Alectryon even more. His mouth opened, wanting to say something, but it simply closed with a strained, perplexed noise. Strymon kept going, nodding his head as if agreeing with Alectryon’s struggled comprehension. “Yeah, she’s pregnant too—no. She already gave birth a night or two ago. Got some bears in the palace now.”

“How—” Alectryon gaped. His hand lowered, allowing the horse to slow down to a walk. “How is that even possible?”

Strymon shrugged, unhelpful. “You know how my uncle’s a guard for the palace? Well, I heard him talking with my parents about how the mistress came running back in the dead of night, screaming so loud she woke half the barracks up. Apparently, some animals were trying to tear her to shreds, so my uncle and his group had to kill them as she fled inside. Was gone for months and to have her come back like that? Mad, really.” He shook his head. “Then, in the morning, she pops out bear-children. He said he could hear their growling cries from outside. Unnerved the poor bastard, he just kept staring off into space as he spoke about it.”

Alectryon let out a laugh full of disbelief. “You sure your uncle wasn’t deep into his cups? I mean you can’t be serious right? This sounds like one of old man Sater’s terrible stories he tells just to get a rise out of people when he’s bored, and the maid won’t give him a refill.”

Strymon hardly looked offended. He did not rise to the bait and instead shook his head, disbelief even in his eyes. The proof of him telling the truth was there, but was there proof in it actually being true? “I thought the same! But he was completely sober and was even thinking about quitting the service to go back to being a mercenary for the Hellenes. It was bad because who in their right mind would go back to doing that?”

“Huh,” he said as he glanced towards the western end of their town. He could not see the palace proper from where he stood, but instead wondered about the merit to this little rumor. Alectryon looked back at his horse who was now nibbling on the grass before he hit its behind with the switch to have it start running again. Maybe it was just that: gossip and nothing more. “Well, guess we’re going to have bears for kings when she passes.” A joke seemed better than admitting his belief or disbelief. How was he even supposed to react to that? Everything about a woman falling in love with a bear and siring children seemed illogical. Can that even happen?

Strymon chuckled as he stretched out his torso, balancing on the wooden beam with his hands firmly planted around it. “Doubt it. The gods are probably going to be really pissed. I wouldn’t be surprised if they all wind up dead and we’d have to place another on the throne. Might be that one warlord…the one with the beard, uh…” He snapped his fingers. “Gordios. Then he will have to watch his back since gods only seem to care about the royal ones, not about people like you or me. So, we’re safe.”

Red eyes flashed in his mind. A bloody hand covering his eyes and healing his wound.

“Safe from their blessings, sure, because there had been a couple nobodies that were cursed because they were really good at something—”

“They were all in Hellas, Alectryon,” Strymon groaned. “Our royals get the funny things happening to them.”

Alectryon chuckled. “Fair enough. Was she descended from a god or is this just chance?”

“Uh…Ares, I think, from her mother’s side. I mean almost all Thracian royals come from him, obviously, so I don’t really say that’s chance.” Strymon plopped down upon the wooden fence, sitting now with a hunched back as his arms folded upon the top beam and rested his chin upon them. “Makes me wonder about the other Hellene gods that pop up every now and again. Not Ares, since he’s more like us than those Hellenes—but the others… What do they want with us?”

Alectryon shook his head. He never thought that far about who they worship. His family were as devout as the rest, but there was always the notion that no god was ever going to save them to go along with that devotion. People like him may get some influence, a little guidance here and there, maybe even the scantiest bit of aid if they sacrifice enough to the gods, but there was nothing more than that to be given if wishing it so. His success, his glory was due to his own hard work, not a blessing from a god. Yet, he did know thinking that helped others in tough spots. However, these thoughts treaded the rather thin line of blasphemy and hubris, thus he kept it to himself. It was an odd sort of relationship that he had with religion, he knew that much.

Exhaling quietly, ridding himself of thoughts of gods and red eyes. For all he knew, the story of the royal family could be nothing more than that: a story. One created solely to scare those who were already drunk and unable to think critically. Or that Strymon had heard it all wrong. Princess Polyphonte could have had kids with some man from another tribe who were not on friendly terms with their own. And, in seeing the kids, the maid could have remarked that they were big, healthy, and strong like bears to appease the King and Queen both. Those of the Triballi tribe were supposed to seen as such, at any rate.

It was a thought that would have kept any one comfort were it true. And for a while, Alectryon was sure he was correct in his thinking. But when two years had passed and a series of strange killings began to wreak their havoc upon the town, his little story for himself started to fall apart the more people spoke of what they had seen in panicked whispers. Everyone said the same thing: two men, as tall as giants with brown shaggy hair much like a bear, and immensely strong with the savage instinct of a wild animal. A coincidence, perhaps, but such one no one desired to take a chance on. The very peace of the tribe was now being rocked by a threat coming from inside the royal palace.

But to take up arms against the royal family…now that was risking far more than anyone cared to admit. It was better to merely keep watch of the time, hunker down in their houses before nightfall, and pray for aid from the divine in a desperate plea that they would not find another one of their own dead by sunrise. But they always did. It was never a full body that could be easily identified either. The victims were always mauled, meat stripped from their bones before being discarded out in the open. Rumors began to spread that perhaps these beastly children had their fill of their family already, so the question of who or what was ruling them sprang into minds often. Strymon once tried to probe his uncle for more answers, but those within the palace guard had walked away, intent on protecting each other’s homes instead.

They were all in the dark. Alectryon noticed more and more families kept to themselves now, hurrying to get home as if it were the only place they felt truly safe in. Even his own brothers and sisters, especially the younger ones, kept indoors as they raced through the house in their blissful ignorance. He was among the adults of the groups who kept their silence, fearing that even speaking the names of the royal family would bring those two terrors down upon them. Alectryon sat upon the nook in the window, watching as his fathers and mothers cradled steaming drinks at the table while they spoke in low voices on what they were to do. The option of packing up and going to another tribe hung heavy in the air. There was also talk of heading to Hellas as well—a thought reserved for the most desperate of cases.

“Can’t we just storm the palace?” Alectryon remarked, breaking their conversation as each pair of eyes turned to him. From irritation to amusement, Alectryon frowned but pushed on. “Two against the tribe’s army should be easy, then we don’t need to cower anymore. If we all do that, it won’t be too bad—the consequences, I mean.”

A laugh from one of his fathers was soon taken up by the rest of his parents. Shame colored his cheeks, but he did not want to be cowed into backing down. At least not until he heard a good enough reason why they were not taking up arms.

“One and twenty and you still act like a boy,” his father, Hales, said through his deep laughter. He was the one Alectryon was sure was his birth father with how kindly he looked upon him, but any sense of asking his mothers would grant him small disagreeable sounds saying it was not important knowledge. “Alectryon, try taking up arms against the High King. Better yet, bring up the idea to any warlord and you would be tried as a traitor and killed as one faster than those beasts can swallow a body whole.”

Suppose that was the good reason. Alectryon rubbed the back of his neck and sighed. “Fine, I see your point. I just hate this feeling. We are stuck at home, thinking about leaving instead of doing anything to solve this.”

“No one likes it, boy,” Hales continued. “But let the elders deal with this problem. All you need to worry about is watching and protecting your siblings. Got it?”

Alectryon nodded, dejected. “Yeah… Got it.”

Life began to feel cramped the longer these threats remained. Curfews were put in to place by the warlords and hunting became strict to the point where Alectryon was no longer allowed to head off on his own. Instead, he was cooped up in the house with his ten younger siblings as if this were a new form of torture cooked up by their parents. Trade, too, had been cut off from each tribe. They did not want to risk outsiders and spark a war with an unfortunate death. Essentially, the Triballi were cut off and things were only going to get worse if they kept this up. Still, no one wanted to deal with the actual threat, which made being stuck inside all the more aggravating.

With a sigh, he laid his head against the table with a hollow thump. There had been no new murders for the past five days and they were all starting to think that something finally had happened to the monsters. Or so they hoped. But the dreadful rumor of them having gone to another tribe was also circulating at the same time. How could they find out if it were the actual case though? All trade, thus all information, had been cut off due to their own insistence. He lifted his head and hit it once against the table. Patience. He needed patience. But this was getting far too out of hand.

Frantic knocking came to the door then, almost splintering the wood from the sounds of it, and Alectryon took full advantage of this appearance. He popped up from his seat, pushing his sister, Sete, off to the side before opening the door to nearly dodge a fist from Strymon.

“Sorry,” his friend said in a rush, looking back before grabbing Alectryon’s wrist to pull him out of the house. “But something’s happening at the palace.”

“Calm down, Stry—” Alectryon grunted as he was pulled further when Strymon began to run. He glanced back at the house where his sister’s head popped out from, glaring at him in irritation. “I’ll be back soon, I promise!” He called, but she did not say anything back and merely slammed the door. She would forgive him later, surely.

Pulling his arm out of Strymon’s grip, they ran faster down the dirt street, passing by confused but also alert neighbors. Some were even heading towards the palace and the question of why was on all their tongues. Picking up his feet, he pushed himself into a headlong sprint with Strymon keeping up easily by his side. There was no telling what they were going to happen upon, but they were not the only ones with the same idea. A small crowd was formed around the front of the palace, far from the actual doors, but close enough that there was no question this was what they gathered for. Those that stood around spoke in hushed whispers with withering glances to the palace as a loud roar was heard from within.

Alectryon pushed through with minor apologies before he got to the front. Strymon puffed beside him as he looked around. “They are saying two men had gone into the palace,” Strymon said. “It was one, but then another came running after him—no one knows from where though.”

“Neighboring tribes?” Alectryon tried, but Strymon shook his head.

“Doubt it, they weren’t wearing anything familiar. But If it were, why would they just send two men? One didn’t even look like a fighter. Too scrawny, really. He’d be first to be eaten by the beasts.”

Alectryon frowned, glancing from the palace doors to the side walls. There was nothing to be seen from the front and if the men had gone in, a small doubt formed in his mind of thinking they would never be seen again. His fingers wiggled at his side, his body feeling antsy from wanting to do something but not knowing what to do. Being kept in the dark was far too maddening, and the desire for answers filled his chest.

In a burst of irrational thinking, he raced towards the palace. Not to the front but dipped towards the side with Strymon trailing close behind, whispering urgent questions that Alectryon had to clamp a hand over his mouth the moment he ducked behind a wall in order to quiet them. He gave his friend a stern look before gesturing with his head to follow. They crouched low, guided by the sound of voices that got clearer the further they walked. It was not until they slid up the back wall of the house and Alectryon peeped through an open window did he find the inhabitants therein.

The High King looked haggard, worn thin as he stared down at something on the floor. The Queen, on the other hand, sobbed into the chest of one of the strangers. Could he be the Queen’s second husband? Curled silver hair shaved on the sides, skin like the night but warm like the sun, and striking compared to the others around him. The second stranger, who Alectryon thought was the one Strymon called scrawny, was tapping a finger to his chin before snapping his fingers together as a thought came to him.

“Cut off their hands and feet,” he announced, words were as fast as his movements like he was always in a rush to get things done. Short, cropped black hair with fiery orange wings at the side of his head. He wore a simple Hellene chiton, foreigner’s garb. “Seems a good enough punishment—can’t eat people when they can’t walk or grab things. Either that or kill them all, but wouldn’t you want to have something unique?”

The sobbing of the Queen grew louder, turning away from the first stranger into the arms of the King. The stranger’s back was broad, decorated by shining white and gold armor with a long, crimson cloak plunging down to the ground from the shoulders which heaved in a weary sigh. He was looking towards the Queen before he murmured. “No.” With a voice so deep it struck Alectryon as sad. More so than that. But the sound of a struggle somewhere had Alectryon sitting up a bit higher to see that the two monsterish children were locked in chains against the wall. They were beastly in form—frothing at the mouth with teeth as sharp as knives. Alectryon’s eyes grew wide, and he heard Strymon stumble back with a gasp.

He then whipped around, pulling Strymon down with him and hushed him. If they were found out, who knew what would happen to them. When Strymon calmed down, Alectryon moved to peek in once more as the two strangers made their move towards the chained beasts. The children tried to snap at the strangers, frenzied with the want of blood as all too human roars ripped forth from their throats. Yet, odd as it was, they calmed as each stranger placed a hand upon a beast’s head. A flash of light forced Alectryon to turn away lest he be blinded and then it was over. The beasts no more, but two great winged birds hopping out of the chains that once bound them in place. The very sight a strange miracle that left Alectryon gaping.

“Gods—” Strymon whispered. “They’re—they’re gods.” His friend scrambled back and Alectryon turned to him, trying to quiet him down, but the man was wide-eyed with terror. “I can’t—I-I want to live.” Strymon shook his head as he stumbled into a panicked run away from the palace, leaving Alectryon alone.

He swallowed hard and chanced another look through the window to find now four birds within the palace. The black-haired stranger picked up two and made his way towards another window, allowing the birds to fly off in their newly afforded freedom. But the silver haired one scooped up the great red bird, a beak much like a vulture, and gave it a loving pet upon its crest. “I think I will keep this one,” he murmured as the black-haired stranger picked up the other large bird to set it free outside. No one seemed to mind—merely a comment to himself. He allowed the bird to rest upon his forearm as he glanced back at the King and Queen.

Red eyes. It was him, from the forest—Alectryon sank a bit more, fearing he would be caught from this angle. Were they truly gods as Strymon said? He knew he should leave. That it would be better for him to be gone from this place, but his eyes kept to the red-eyed god and found a beauty about him. Were gods supposed to be seen as such? He glanced at the other god who was now pulling out a sheaf of parchment from his satchel as if the scene before him was not taking place. Surely, he was handsome as well, but Alectryon’s gaze kept getting drawn into those red eyes as if they were pulling him forth unknowingly.

“Father, I am sorry—I didn’t think she would turn out to be like this. I did all that I could, but she still…” the Queen said through his tears. The red-eyed god stepped forth, allowing the vulture to climb to his shoulder as he embraced the Queen with soothing words meant only for her ears.

Father…

Ares, I think, from her mother’s side. I mean almost all Thracian royals come from him.

Alectryon finally sunk out of sight from the window, and, in a daze, he made his way out of the vicinity of the palace. All his questions from before were finally given answers, but he was not sure if they unnerved him…or thrilled him. He made his way back to the crowd of onlookers who stared at him with the same questions he once had. Some pulled at his arm to stop and tell them what he saw, but he could only shake his head. It would sound too farfetched to say it out loud, and he doubted it would have been believed. So, he pushed away, and got to where Strymon was, far from everyone else as he stared up at the cloudless blue sky. Alectryon stood beside him and cleared his throat softly.

“Do you think they knew we were there, watching?” Strymon asked. His voice did not hold the same shake as before, but the fear could still be heard. “I mean…those two…the gods?”

“It was Ares—one of them. The Queen called him father. I don’t know who the other one was though.” Names of gods cycled through his mind, but none he could put that face to. Was that bad? Would that other god know of their ignorance? Could they read minds?

Strymon swore under his breath. “You hear stories from other people of what the gods do to those who are too curious or too arrogant for their own good. Think they are all idiots until you do something that gets yourself into that same position as the idiots, and down comes a god to make you regret ever being born. Now you’re the new idiot of a story told to warn people not to make the same mistakes.”

Alectryon huffed. “Just try not to think about it, Strymon. I doubt they noticed us—they were too busy with…all that.”

“I think I just want to go home now.”

“Good idea.”

#ooc.#char. study » alectryon#i joined a myth with his just for ease of storytelling / getting him to meet with the man the myth the legend himself#also back in 2021 i wasn't as well versed in ancient thracian culture so pls be gentle about that if you read this 🙏#but yeah there's like two more parts left to this story so it cuts off weirdly because of that

1 note

·

View note

Text

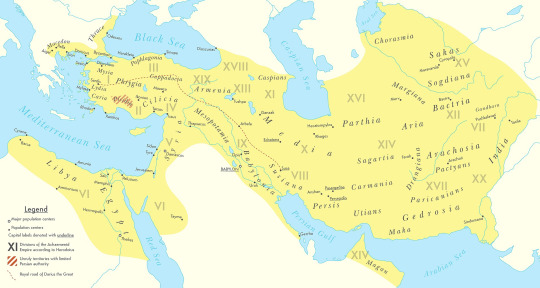

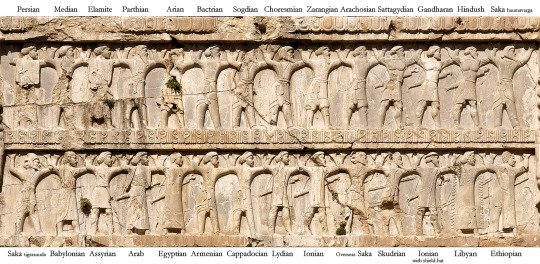

Countries that are no more: Achaemenid Empire (550BC-330BC)

It was not the first empire of Iranian peoples, but it arose as probably the greatest in terms of influence and became the measure by which all subsequent Iranian empires tended to compare themselves and its influence on culture, government & civil infrastructure would influence others beyond the span of its territory and the span of time. This is the Achaemenid Empire.

Name: In Old Persian it was known as Xšāça or the "The Kingdom or the Empire", it was named the Achaemenid Empire by later historians. Named after the ruling dynasty established by its founder Cyrus the Great who cited the name of his ancestor Haxāmaniš or Achaemenes in Greek as progenitor of the dynasty. It is sometimes also referred to as the First Persian Empire. The Greeks simply referred to it as Persia, the name which stuck for the geographic area of the Iranian plateau well into the modern era.

Language: Old Persian & Aramaic were the official languages. With Old Persian being an Iranian language that was the dynastic language of the Achaemenid ruling dynasty and the language of the Persians, an Iranian people who settled in what is now the southwestern Iranian plateau or southwest Iran circa 1,000 BC. Aramaic was a Semitic language that was the common and administrative language of the prior Neo-Assyrian & Neo-Babylonian Empires which centered in Mesopotamia or modern Iraq, Syria & Anatolian Turkey. After the Persian conquest of Babylon, the use of Aramaic remained the common tongue within the Mesopotamian regions of the empire, eventually becoming a lingua franca across the land. As the empire spread over a vast area and became increasingly multiethnic & multicultural, it absorbed many other languages among its subject peoples. These included the Semitic languages Akkadian, Phoenician & Hebrew. The Iranian language of Median among other regional Iranian languages (Sogdian, Bactrian etc). Various Anatolian languages, Elamite, Thracian & Greek among others.

Territory: 5.5 million kilometers squared or 2.1 million square miles at its peak circa 500BC. The Achaemenid Empire spanned from southern Europe in the Balkans (Greece, Bulgaria, European Turkey) & northwest Africa (Egypt, Libya & Sudan) in the west to its eastern stretches in the Indus Valley (Pakistan) to parts of Central Asia in the northeast. It was centered firstly in the Iranian Plateau (Iran) but also held capitals in Mesopotamia (Iraq). Territory was also found in parts of the Arabian Peninsula & the Caucausus Mountains.

Symbols & Mottos: The Shahbaz or Derafsh Shahbaz was used as the standard of Cyrus the Great, founder of the empire. It depicts a bird of prey, typically believed to be a falcon or hawk (occasionally an eagle) sometimes rendered gold against a red backdrop and depicts the bird holding two orbs in its talons and adorned with an orb likewise above its head. The symbolism was meant to depict the bird guiding the Iranian peoples to conquest and to showcase aggression & strength coupled with dignity. The imperial family often kept falcons for the pastime of falconry.

Religion: The ancient Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism served as the official religion of the empire. It was adopted among the Persian elite & and had its unique beliefs but also helped introduce the concept of free-will among its believers, an idea to influence Judaism, Christianity & Islam in later centuries. Despite this official religion, there was a tolerance for local practices within the subject regions of the empire. The ancient Mesopotamian religion in Babylon & Assyria, Judaism, the Ancient Greek & Egyptian religions & Vedic Hinduism in India was likewise tolerated as well. The tolerance of the Achaemenids was considered a relative hallmark of their dynasty from the start. Famously, in the Old Testament of the Bible it was said that it was Cyrus the Great who freed the Jews from their Babylonian captivity and allowed them to return to their homeland of Judea in modern Israel.

Currency: Gold & silver or bimetallic use of coins became standard within the empire. The gold coins were later referred to as daric and silver as siglos. The main monetary production changes came during the rule of Darius I (522BC-486BC). Originally, they had followed the Lydian practice out of Anatolia of producing coins with gold, but the practice was simplified & refined under the Achaemenids.

Population: The estimates vary ranging from a low end of 17 million to 35 million people on the upper end circa 500BC. The official numbers are hard to determine with certainty but are generally accepted in the tens of millions with the aforementioned 17-35 million being the most reasonable range based on available sources.

Government: The government of the Achaemenid Empire was a hereditary monarchy ruled by a king or shah or later referred to as the ShahanShah or King of Kings, this is roughly equivalent to later use of the term Emperor. Achaemenid rulers due the unprecedented size of their empire held a host of titles which varied overtime but included: King of Kings, Great King, King of Persia, King of Babylon, Pharaoh of Egypt, King of the World, King of the Universe or King of Countries. Cyrus the Great founded the dynasty with his conquest first of the Median Empire and subsequently the Neo-Babylonians and Lydians. He established four different capitals from which to rule: Pasargadae as his first in Persia (southwest central Iran), Ecbatana taken from the Medians in western Iran's Zagros Mountains. The other two capitals being Susa in southwest Iran near and Babylon in modern Iraq which was taken from the Neo-Babylonians. Later Persepolis was made a ceremonial capital too. The ShahanShah or King of Kings was also coupled with the concept of divine rule or the divinity of kings, a concept that was to prove influential in other territories for centuries to come.

While ultimate authority resided with the King of Kings and their bureaucracy could be at times fairly centralized. There was an expansive regional bureaucracy that had a degree of autonomy under the satrapy system. The satraps were the regional governors in service to the King of Kings. The Median Empire had satraps before the Persians but used local kings they conquered as client kings. The Persians did not allow this because of the divine reverence for their ShahanShah. Cyrus the Great established governors as non-royal viceroys on his behalf, though in practice they could rule like kings in all but name for their respective regions. Their administration was over their respective region which varied overtime from 26 to 36 under Darius I. Satraps collected taxes, acted as head over local leaders and bureaucracy, served as supreme judge in their region to settle disputes and criminal cases. They also had to protect the road & postal system established by the King of Kings from bandits and rebels. A council of Persians were sent to assist the satrap with administration, but locals (non-Persian) could likewise be admitted these councils. To ensure loyalty to the ShahanShah, royal secretaries & emissaries were sent as well to support & report back the condition of each satrapy. The so called "eye of the king" made annual inspections of the satrapy to ensure its good condition met the King of Kings' expectations.

Generals in chief were originally made separate to the satrap to divide the civil and military spheres of government & were responsible for military recruitment but in time if central authority from the ShahanShah waned, these could be fused into one with the satrap and general in chiefs becoming hereditary positions.

To convey messages across the widespread road system built within the empire, including the impressive 2,700 km Royal Road which spanned from Susa in Iran to Sardis in Western Anatolia, the angarium (Greek word) were an institution of royal messengers mounted on horseback to ride to the reaches of the empire conveying postage. They were exclusively loyal to the King of Kings. It is said a message could be reached to anywhere within the empire within 15 days to the empire's vast system of relay stations, passing message from rider to rider along its main roads.

Military: The military of the Achaemenids consisted of mostly land based forces: infantry & cavalry but did also eventually include a navy.

Its most famous unit was the 10,000-man strong Immortals. The Immortals were used as elite heavy infantry were ornately dressed. They were said to be constantly as 10,000 men because for any man killed, he was immediately replaced. Armed with shields, scale armor and with a variety of weapons from short spears to swords, daggers, slings, bows & arrows.

The sparabara were the first line of infantry armed with shields and spears. These served as the backbone of the army. Forming shield walls to defend the Persian archers. They were said to ably handle most opponents and could stop enemy arrows though their shields were vulnerable to enemy spears.

There was also the takabara light infantry and though is little known of them it seems they served as garrison troops and skirmishers akin to the Greek peltast of the age.

The cavalry consisted of four distinct groups: chariot driven archers used to shoot down and break up enemy formations, ideally on flat grounds. There was also the traditional horse mounted cavalry and also camel mounted cavalry, both served the traditional cavalry functions and fielded a mix of armor and weapons. Finally, there was the use of war elephants which were brought in from India on the empire's eastern reaches. These provided archers and a massive way to physically & psychologically break opposing forces.

The navy was utilized upon the empire's reaching the Mediterranean and engaged in both battles at sea and for troop transport to areas where troops needing deploying overseas, namely in Greece.

The ethnic composition of Achaemenid military was quite varied ranging from a Persian core with other Iranian peoples such as the Medians, Sogdian, Bactrians and Scythians joining at various times. Others including Anatolians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Anatolians, Indians, Arabs, Jews, Phoenicians, Thracians, Egyptians, Ethiopians, Libyans & Greeks among others.

Their opponents ranged from the various peoples they conquered starting with the Persian conquest of the Medians to the Neo-Babylonians, Lydians, Thracians, Greeks, Egyptians, Arabs & Indians and various others. A hallmark of the empire was to allow the local traditions of subjugated areas to persist so long as garrisons were maintained, taxes were collected, local forces provided levies to the military in times of war, and they did not rebel against the central authority.

Economy: Because of the efficient and extensive road system within the vast empire, trade flourished in a way not yet seen in the varied regions it encompassed. Tax districts were established with the satrapies and could be collected with relative efficiency. Commodities such as gold & jewels from India to the grains of the Nile River valley in Egypt & the dyes of the Phoenicians passed throughout the realm's reaches. Tariffs on trade & agricultural produce provided revenue for the state.

Lifespan: The empire was founded by Cyrus the Great circa 550BC with his eventual conquest of the Median & Lydian Empires. He started out as Cyrus II, King of Persia a client kingdom of the Median Empire. His reign starting in 559BC. Having overthrown and overtaken the Medians, he turned his attention Lydia and the rest of Anatolia (Asia Minor). He later attacked the Eastern Iranian peoples in Bactria, Sogdia and others. He also crossed the Hindu Kush mountains and attacked the Indus Valley getting tribute from various cities.

Cyrus then turned his attention to the west by dealing with the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Following his victory in 539BC at the Battle of Opis, the Persians conquered the Babylonia with relative quickness.

By the time of Cyrus's death his empire had the largest recorded in world history up to that point spanning from Anatolia to the Indus.

Cyrus was succeeded by his sons Cambyses II and Bardiya. Bardiya was replaced by his distant cousin Darius I also known as Darius the Great, whose lineage would constitute a number of the subsequent King of Kings.

Darius faced many rebellions which he put down in succession. His reign is marked by changes to the currency and the largest territorial expansion of the empire. An empire at its absolute zenith. He conquered large swaths of Egypt, the Indus Valley, European Scythia, Thrace & Greece. He also had exploration of the Indian Ocean from the Indus River to Suez Egypt undertaken.

The Greek kingdom of Macedon in the north reaches of the Hellenic world voluntarily became a vassal of Persia in order to avoid destruction. This would prove to be a fateful first contact with this polity that would in time unite the Greek-speaking world in the conquest of the Achaemenid Empire. However, at the time of Darius I's the reign, there were no early indications of this course of events as Macedon was considered even by other Greek states a relative backwater.

Nevertheless, the Battle of Marathon in 490BC halted the conquest of mainland Greece for a decade and showed a check on Persia's power in ways not yet seen. It is also regarded as preserving Classical Greek civilization and is celebrated to this day as an important in the annals of Western civilization more broadly given Classical Greece & in particular Athens's influence on western culture and values.

Xerxes I, son of Darius I vowed to conquer Greece and lead a subsequent invasion in 480BC-479BC. Xerxes originally saw the submission of northern Greece including Macedon but was delayed by the Greeks at the Battle of Thermopylae, most famously by Spartan King Leonidas and his small troop (the famed 300). Though the Persians won the battle it was regarded as a costly victory and one that inspired the Greeks to further resistance. Though Athens was sacked & burnt by the Persians, the subsequent victories on sea & land at Salamis & Plataea drove the Persians back from control over Greece. Though war would rage on until 449BC with the expulsion of the Persians from Europe by the Greeks.

However, the Greeks found themselves in a civil war between Athens & Sparta and Persia having resented the Athenian led coalition against their rule which had expelled them from Europe sought to indirectly weaken the Greeks by supporting Greek factions opposed to Athens through political & financial support.

Following this reversal of fortune abroad, the Achaemenid Empire not able to regain its foothold in Europe, turned inward and focused more on its cultural development. Zoroastrianism became the de-facto official religion of the empire. Additionally, architectural achievements and improvements in its many capitals were undertaken which displayed the empire's wealth. Artaxerxes II who reigned from 405BC-358BC had the longest reign of any Achaemenid ruler and it was characterized by relative peace and stability, though he contended with a number of rebellions including the Great Satraps Revolt of 366BC-360BC which took place in Anatolia and Armenia. Though he was successful in putting down the revolt. He also found himself at war with the Spartans and began to sponsor the Athenians and others against them, showcasing the ever dynamic and changing Greco-Persian relations of the time.

Partially for safety reasons, Persepolis was once again made the capital under Artaxerxes II. He helped expand the city and create many of its monuments.

Artaxerxes III feared the satraps could no longer be trusted in western Asia and ordered their armies disbanded. He faced a campaign against them which suffered some initial defeats before overcoming these rebellions, some leaders of which sought asylum in the Kingom of Macedon under its ruler Philip II (father of Alexander the Great).

Meanwhile, Egypt had effectively become independent from central Achaemenid rule and Artaxerxes III reinvaded in around 340BC-339BC. He faced stiff resistance at times but overcame the Egyptians and the last native Egyptian Pharaoh Nectanebo II was driven from power. From that time on ancient Egypt would be ruled by foreigners who held the title Pharaoh.

Artaxerxes III also faced rebellion from the Phoenicians and originally was ejected from the area of modern coastal Lebanon, Syria & Israel but came back with a large army subsequently reconquered the area including burning the Phoenician city of Sidon down which killed thousands.

Following Artaxerxes III's death his son succeeded him but a case of political intrigue & dynastic murder followed. Eventually Darius III a distant relation within the dynasty took the throne in 336BC hoping to give his reign an element of stability.

Meanwhile in Greece, due to the military reforms and innovations of Philip II, King of Macedon, the Greek speaking world was now unified under Macedon's hegemony. With Philip II holding the title of Hegemon of the Hellenic League, a relatively unified coalition of Greek kingdoms and city-states under Macedon premiership that formed to eventually invade Persia. However, Philip was murdered before his planned invasion of Asia Minor (the Achaemenid's westernmost territory) could commence. His son Alexander III (Alexander the Great) took his father's reforms and consolidated his hold over Greece before crossing over to Anatolia himself.

Darius III had just finished reconquering some rebelling vestiges of Egypt when Alexander army crossed over into Asia Minor circa 334BC. Over the course of 10 years Alexander's major project unfolded, the Macedonian conquest of the Persian Empire. He famously defeated Persians at Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela. The latter two battles against Darius III in person. He took the King of Kings family hostage but treated them well while Darius evacuated to the far eastern reaches of his empire to evade capture. He was subsequently killed by one of his relatives & satraps Bessus, whom Alexander eventually had killed. Bessus had declared himself King of Kings though this wasn't widely recognized and most historians regard Darius III, the last legitimate ShahanShah of Achaemenids.

Alexander had taken Babylon, Susa & Persepolis by 330BC and effectively himself was now ruler of the Persian Empire or at least its western half. In addition to being King of Macedon & Hegemon of the Hellenic League, he gained the titles King of Persia, Pharaoh of Egypt & Lord of Asia. Alexander would in time eventually subdue the eastern portions of the Achaemenid realm including parts of the Indus Valley before turning back to Persia and Babylon where he subsequently became ill and died in June 323BC at age 32. Alexander's intentions it appears were never to replace the Achaemenid government & cultural structure, in fact he planned to maintain and hybridize it with his native Greek culture. He was in fact an admirer of Cyrus the Great (even restoring his tomb after looting) & adopted many Persian customs and dress. He even allowed the Persians to practice their religion and had Persian and Greeks start to serve together in his army. Following his death and with no established successor meant the empire he established which essentially was the whole Achaemenid Empire's territory in addition to the Hellenic world fragmented into different areas run by his most trusted generals who established their own dynasties. The Asian territories from Anatolia to the Indus (including Iran and Mesopotamia) gave way to the Hellenic ruled Seleucid Empire while Egypt became the Hellenic ruled Ptolemaic Kingdom. The synthesis of Persian and Greek cultures continued in the Seleucid and Greco-Bactrian kingdoms of antiquity.

The Achaemenid Empire lasted for a little over two centuries (550BC-330BC) but it casted a long shadow over history. Its influence on Iran alone has persisted into the modern age with every subsequent Persian Empire claiming to be its rightful successor from the Parthian & Sasanian Empires of pre-Islamic Iran to the Safavids of the 16th-18th century and the usage of the title Shah until the last Shah's ejection from power in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Even the modern Islamic Republic of Iran uses Achaemenid imagery in some military regiments and plays up its importance in tourism and museums as a source of pride to Persian (Farsi) & indeed Iranian heritage. Likewise, its form of governance and the pushing of the concept of divine rights of kings would transplant from its Greek conquerors into the rest of Europe along with various other institutions such as its road & mail system, tax collection & flourishing trade. Its mix of centralized & decentralized governance. Its religious & cultural tolerance of local regions even after their conquest would likewise serve as a template for other empires throughout history too. The Achaemenid Empire served as a template for vast international & transcontinental empires that would follow in its wake & surpass its size & scope of influence. However, it is worth studying for in its time, it was unprecedented, and its innovations so admired by the likes of Alexander the Great and others echo into the modern era.

#military history#antiquity#iran#greece#ancient greece#classical greece#ancient ruins#ancient iran#ancient persia#achaemenid#persia#zoroastrianism#alexander the great#cyrus the great#xerxes#artwork#government#history#persian empire#ancient egypt

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Horned Serpent

So before I get started on this one, I have a couple of things to get out of the way. First, I will be using she/her pronouns for the Horned Serpent; this is just because UPG and because I'm used to it. I know someone else who venerates/worships the Horned Serpent, uses they/them pronouns for them, and considers them to be beyond gender / present as whatever gender they feel like. Second, I will be focusing on my interpretation of her on the Gundestrup Cauldron, in part because there's really not a lot of literature on her, even when you include works that specifically analyze Cernunnos' depictions. Third (and related), I will be using the National Museum of Denmark's estimate as to when/where the Gundestrup Cauldron was made, which is roughly in the Danubian or Wallachian Plain(s) around 150 BCE to 1 CE (link).

So first a little historical & cultural context. This area, as far as culture groups, would have been a heck of a melting pot, between the Dacians and Thracians that already lived there, the Scythians coming in and also living near by, the Gauls that moved in around the 300s-200s, the Greeks who came up and started establishing colonies along the Black Sea in the 300s, and the Romans, encroaching on everyone's business around the time the Cauldron was built. A pretty solid primer on the history of the region is A Companion to Ancient Thrace, published by Wiley Blackwell.

So I'm gonna try to make sense but it might be a little disorganized going forward. Anyway, onto the actual thoughts & stuff. So anyone who's taken even a passing glance at Cernunnos is well aware of the Horned Serpent, since she is present in basically every ancient art you can find with him. On the Gundestrup Cauldron, she appears three times, all on the interior panels. One is at the Hero's heel, who's holding the wheel; a second is at the end of a line of heroic riders, which seems to be a Thracian horseman motif; and of course the famous Cernunnos panel. In Thracian Tales of the Gundestrup Cauldron, published by Najade Press, Jan Best presents an interpretation of the interior panels as a story, and assumes that Cernunnos is singing in his famous panel, specifically about the secrets of immortality, a concept which was very popular at the time. I agree with this and I also assume that the depiction of Taranis / the wheel god is that he is also singing, and if he is singing then the lions and griffins - both predators associated with kingship (griffins were protectors of the pharaoh, and also decorated certain tombs out in ancient Persia), then the action of passing off the Wheel must have symbolic meaning, such as being handed the Wheel of Heaven.

The Gundestrup Cauldron's exterior also has very clear influence from the Scythians, you can almost 1:1 map the gods based on Herodotus's retelling of the Pontic stories. I believe there are also thematic parallels going on here on the Wheel God panel, featuring a new god/king being given the symbol of his domain. Wikipedia actually has some relatively thorough articles on Scythian religion as well as the genealogical myth specifically, which is the myth that I personally associate with the wheel-giving panel. As well, the animals in this panel don't appear to be particularly concerned with attacking anyone - if anything, the griffins and lionesses are slightly tilted from one to the next, which makes me think it's more likely that they are dancing, especially if the human/divine subjects are singing, especially if the human with the helmet is receiving a high honor, potentially his rank amongst the gods. In this panel, she is just at the hero's feet, not really joining the parade if the animals, but clearly not ready to attack either, but her attention does seem to be drawn towards the hero.

The final panel she is on is the panel featuring the nine soldiers and the heroized dead, represented by the "Thracian horseman" motif. After Alexander the Great and his penchant for having statues of himself be on horseback, it became popular for wealthy men and nobles to depict themselves riding horseback to a goddess or sacred tree (unfortunately my best source discussing this in English is also not great and he comes up with some..... questionable theories), but the popularity seems to have blown up to the point where even deities such as Zeus were depicted on horseback in a similar manner. There are also mentions in a few other sources that the Thracians believed in the ability for people to essentially become immortal after death. Unfortunately, I'm having trouble sorting out my notes and this essay has been nagging me for weeks now.

Anyway, I interpret this panel as what is expected to happen to us after we die - the "ordinary", so to speak, are lead to a deity, likely to be reincarnated (this is honestly just a guess on my part largely due to the popularity of that in Greece for ever, and Grecian influence was in full swing by the time the Cauldron was made), meanwhile the "extraordinary" are lead by the Horned Serpent.

This is where I tie all three together to my upg/theology: The Horned Serpent is a friend and ally to Cernunnos. He teaches the secrets of life after death to those who will listen. The Horned Serpent is by his side during his teaching, and when we die, if we have proven ourselves worthy during life, she guides us through the trials of the afterlife. If we succeed in these trials, we are awarded with apotheosis - becoming a god or godlike - and she stands by our side as we earn this prize.

@musingmelsuinesmelancholy sorry it took me so long x.x & I hope this makes sense!

#cernunnos#thracian polytheism#gaulish polytheism#dacian polytheism#scythian polytheism#the horned serpent#balkan paganism#celtic paganism#paganism

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The sword of the day is the sica.

The sica is a short sword or long dagger originating with the Illyrian people of the Mediterranean. It also saw use in ancient Roman culture, especially as a gladiator’s weapon. It was largely used by Thraex (Thracian) gladiators, in conjunction with a small parma shield and light armor. The bend allowed a wielder to strike around shields at an opponent’s flanks, and generally to strike from unpredictable angles.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Thing Of Vikings Chapter 79: On The Threshold

Chapter 79: On The Threshold

One of the great paradoxes that comes from the study of history is that historians are forced to simultaneously speak in both concrete and abstract terms. We say 'the society decided to change' at the same time as we speak of the leaders making specific decisions. But the society did not decide to change. The Hooligans of Berk, for example, did not, as some abstract whole, decide to adopt dragons and grow to become the core of a new sovereign nation over the next five years. Nor did then-Chief Stoick's decision to allow for the adoption of dragons force this decision. No. Individuals within that society decided to change, in how they acted or how they viewed the world, while others did not. And yet we are forced to speak in the aggregate, the cumulative, taking the broad trend of the social unit and applying it to all members inside. We can recognize the individual dissenters when their dissent from the mean is sufficient to stand out, and yet this very recognition paints a degree of uniformity on the rest that is both unrealistic and unearned.

Furthermore, referring to the aggregate of the society in the abstract creates a false impression of their numbers, simply due to the common fallacies of equivocation and false equivalence (i.e. we call them the same thing, ergo we see them as being roughly the same). We project ourselves and our own modern expectations and experiences with current political entities onto the past, despite those historical units being vastly smaller, simpler, and less developed). We speak of the Byzantine Empire and the North Sea Empire as two simple units. Due to the difficulties that many have with comprehending large numbers and larger scales, the typical comprehension of the concept of "Empire" lends itself to a false equivalence, that one Empire is much like another Empire in size, population, economy, culture and so forth, but that mental abstraction again does a disservice in scale. To illustrate, consider that, in AD 1040, there were more people occupying Constantinople and the Thracian farmland immediately outside the city's famous walls than there were in all of the island of Eire in that same year. Meanwhile, Sweden, Norway and Denmark together had less than a million people combined, while the city of Baghdad alone had over a million people sheltering behind its walls. And again, in making such comparisons, we fall prey to the lure of the abstract, of referencing the masses of otherwise anonymous people as conglomerate wholes.

But at the same time, such abstraction is necessary; we do not have the data to be able to conclusively say that, out of the approximately 300,000 Albans who lived under King Mac Bethad's rule, 68,821 agreed with his stated desire for continued independence from Berk's influence, while another 121,749 would have been happier if he had made overtures of integration prior to his fatal duel with Astrid clan Haddock. Such precision is not available to us and we are thus forced to speak in the abstract and the aggregate, erasing the heterogeneous beliefs and attitudes of entire generations—save those individuals who had the foresight to record their thoughts, or the impact that inspired others to record them.

—To Label The Stars: The Cultural Impact Of Names, Kyoto University Press, Ltd.

AO3 Chapter Link

~~~

My Original Fiction | Original Fiction Patreon

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ares's design and other stuff

Okay, I now feel myself very stupid, because I thought that Ares's refusal of the sandals in his GOW1 design is some strange fictional decision.

But seems like it is KINDA CANON??? In mythology Ares has Thracian origin (or at least he keeps favoritism towards this area of the Hellada). Thracia was the most nothern part of the Hellenic Greece, has very cold climat (and a huge influence by the celtic tribes). What i am getting at... Thracian peltasts commonly weared enclosed mid-calf fawn-skin boots named embades.

Ares is not strange, he just absorbs military culture.

(By the way, unlike the other civilized polises, Thracians considered tattooes as a sign of nobility. I wonder if Ares has one... if he has not, he probably absolutely loved Kratos's huge tattoo.)

(Oh, maaaaaybe he has no any tattoos, but that's the reason why he has some "body art" on his armor!).

(I think his mom Hera is just against of it lol)

(Ares is mama's boi, he won't tattoo himself against her wish even if he want to.)

(BTW-2, first Aphrodite's concept art from GOW3 shows that she has AN OMEGA TATTOO RIGHT ON HER FOREHEAD, which was enough to pisses Hera off for all eternity in sum with Ares's and Aphrodite's romance)

#god of war#gow#kratos#ares#ares god of war#upn the sky handycraft#kratos gow#aphrodite#Hera#Hera gow#Aphrodite gow#god of war 3

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

This epic song was made by the Iranian composer and musician, Farya Faraji! It captures the medieval Balkan style extremely well, and he sings in Greek and Old Church Slavonic (to represent the Bulgarian side)! Thank you, Farya Faraji, for your great cultural immersion!

This composition is about emperor Basil II Porphyrogennetos, “the Purple-born”, nicknamed the Bulgar Slayer (Boulgaroktónos). This nickname was earned after his conflict and annihilation of the First Bulgarian Empire, the principal European foe of the Eastern Romans during that era. A proficient statesman, the Empire flourished in many aspects during his reign, and his legacy is one of a national hero in Greece, whilst being despised among the Bulgarians.

Farya Faraji explains:

Musically, I wanted this track to reflect both Bulgarian and Greek sensibilities, and the best place for that was Thracian music—a shared cultural style overlapping both Greek and Bulgarian music. This geographical style of music, defined among other things by the usage of the gaida bagpipe to provide dance tunes also fits the geographical area where many of the confrontations between the two empires occurred, and also matches the regional origin of Basil’s dynasty, which originated from Thrace. The gaida bagpipe in this piece fulfills a dual Greek-Bulgarian role as it is used virtually identically on both sides of Thrace.

(see more of his explanations in the piece's description on YouTube)

#vasileios voulgaroktonos#Farya Faraji#iran and greece#greek music#thrace#bulgaria#bulgarian history#greek history#Youtube

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thracian Tattoos

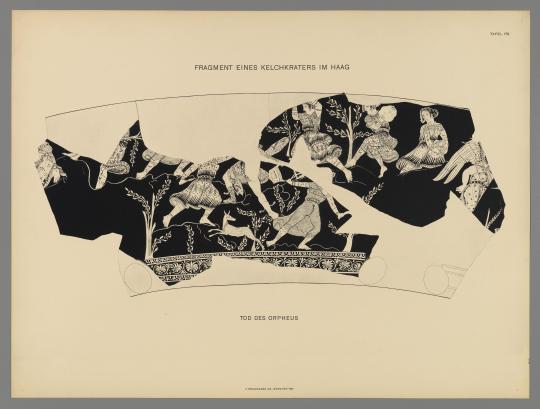

"Thracian Woman killing Orpheus"

Pistoxenos Painter, circa 470-460 BC. NAMA nr. 15190.

Earlier this year, during an excursion to Greece, I came across this fragmented cup at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. It bears the image of the murder of Orpheus by a Maenad (or at least a Thracian, more on that later). What piqued my interest, however, was what seemed to be a tattoo of a grazing animal on the right arm, as well as geometric designs on the wrists.

At the time I deemed it a solitary case until I came across the image below.

"Death of Orpheus"

Black Fury Painter, circa 400-375 BCE. APMA nr. 02581.

Print by K. Reichhold.

Here, the murder is depicted with a much larger group of Maenads/Thracians. Orpheus, his person largely missing, can be identified in the middle with his left hand clinging to the lyre. Additionally, he is the only one in this group lacking body art on the exposed limbs.

The assaulting group bears rocks, knives, and other weapons, while their arms and legs are covered with simple line drawings of animals resembling deer, as well as abstract geometric patterns. To draw comparisons with the upper cup drawing would not be out of the question.

I was hesitant to call them tattoos at first, but an article by C.P. Jones more or less confirms that they were, based on various historical sources. Tattoos (Or stigma from στίζω: to mark. Not to be confused with the English use of the term) for decoration were a rare occurrence in antiquity, but there seems to be an exception for Thrace, where tattoos on women were a sign of esteem.

Recommended reading:

Jones, C. P. “Stigma: Tattooing and Branding in Graeco-Roman Antiquity.” The Journal of Roman Studies 77 (1987): 139–55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/300578.

(See section VI for the specific case of Thrace).

Schildkrout, Enid. “Inscribing the Body.” Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (2004): 319–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25064856.

(A general overview of tattoos and body art throughout history and in cultures across the world).

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

The indigenous AfroGreeks

While the term Afrogreek is used nowadays for Greek citizens who are second generation immigrants from the African continent, it is a little known fact that there is a small population of old indigenous Afrogreeks, Greeks of distant African descent whose families have been in the country possibly even for centuries.

Most of them are concentrated in the village Ávaton in Xanthi, Thrace and nearby communities. Their African origins go so back in time that the Afrogreeks of Thrace do not know where their ancestors really originated from, although recent research suggests that the majority of their ancestors might have been from Sudan. A few of them travelled to Africa in search for their roots but failed to find any clear answers. Most view themselves only as indigenous Greeks, as they haven't known another land.

It is believed their ancestors arrived here as slaves traded from Africa by the Ottoman Empire. This is why they are in their majority Muslims and many have Turkish as their first or second language, given also that this is the language they practice their religion in. Despite that, the vast majority identifies as Greek Muslim and not as ethnic Turkish. Most of them agree they don't experience racism nowadays, or that “this is a problem they have moved on from”, especially within the borders of Xanthi, however their existence is so little known that their presence sometimes causes bewilderment even to the neighbouring rural Thracian regions, such as Komotini. Here it would be interesting to mention something that I had too speculated some time ago about racism in Greece: Some Afrogreeks said that most racist incidents they experienced were revolving around their religion rather than their skin colour. In their little communities, on the other hand, there is a lot of acceptance. Some of them enjoy a fascinating blend of the two cultures and religions in their everyday life, noting they celebrate Bairam, and Christmas, and Easter and it doesn't matter. The younger generations speak Greek more and more, they follow more closely the Greek pop culture (especially after the rise of the Antetokounmpo brothers) and marriages to white Greeks become more frequent. Older Afrogreeks sometimes oppose to such marriages for no other reason than their care to preserve that small and unique to the Greek land community. Their current population is about 200 people.

In Mrs Reifoglou's words, they are indigenous like the corn that grows there.

Afrogreeks of Thrace now & then.

Photos by Alexandros Avramidis.

My post is a summary of the respective Greek article by Kathimerini newspaper.

#greece#afrogreeks#people#greek people#greeks#african people#greek facts#avaton#xanthi#thrace#mainland

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plutarch is for us the chief mouthpiece of the theory that all religions are fundamentally one, under different names and with different practices. For him and Maximus of Tyre ‘the gods’ are symbolic representations of the attributes of a Deity who is in his inmost nature unknowable. Maximus and Dion Chrysostom are ‘modernist’ in their views about myth and ritual; Philostratus and Ælian are genuinely superstitious. The Hermetic writings are good examples of the Plutarchian theory. They show, however, that the combination of philosophic monotheism with popular polydaemonism was becoming difficult, though the writers are equally anxious to retain both, as indeed the Neoplatonists were. Syncretism was easier when the gods were regarded as cosmic energies, or when their cults were fused in the popular worship of the sun and stars.

Dionysus and Orpheus were two nearly connected forms of the Sun-god, and the worship of both was influenced by the rites of the Thracian Sabazius. The central act of both mysteries was the rending in pieces of the god or hero, the lament for him, his resurrection, and the communion of his flesh and blood as a ‘medicine of immortality.’ The Egyptian Osiris had also been torn in pieces by his enemies; his resemblance to Dionysus was close enough to tempt many to identify them. In the Egyptian worship the doctrine of human immortality had long been emphasised, and this was now the most welcome article of faith everywhere. It was easy to fuse these national mystery-cults with each other because at bottom they all symbolised the same thing—the hope of mystical death and renewal, the death unto sin and the new birth unto righteousness, based on the analogy of nature's processes of death and rebirth.

While Judaism was purging itself from its Hellenistic element and relapsing into an Oriental religion, the bond of union in a people who were determined to remain aliens in Europe, Christianity was developing rapidly into a syncretistic European religion, which deliberately challenged all the other religions of the empire on their own ground and drove them from the field by offering all the best that they offered, as well as much that they could not give. It was indeed more universal in its appeal than any of its rivals. For Neoplatonism, until it degenerated, was the true heir of the Hellenic tradition, and had no essential elements of Semitic origin. Christianity had its roots in Judaism; but its obligation to Greek thought began with St. Paul, and in the third century ‘philosophic’ Christianity and Platonism were not far apart.

The real quarrel between Neoplatonism and Christianity in the third century lay in their different attitudes towards the old culture. In spite of the Hellenising of Christianity which began with the first Christian missions to Europe, the roots of the religion were planted in Semitic soil, and the Church inherited the prejudices of the Jews against European methods of worship.

Hellenism was vitally connected with polytheism, and with the sacred art which image-worship fostered. These things were an abomination to the Jews, and therefore to the early Christians. We, however, when we remember later developments, must take our choice between condemning matured Catholicism root and branch, and admitting that the uncompromising attitude of the early Church towards Hellenic polydaemonism was narrow-minded.