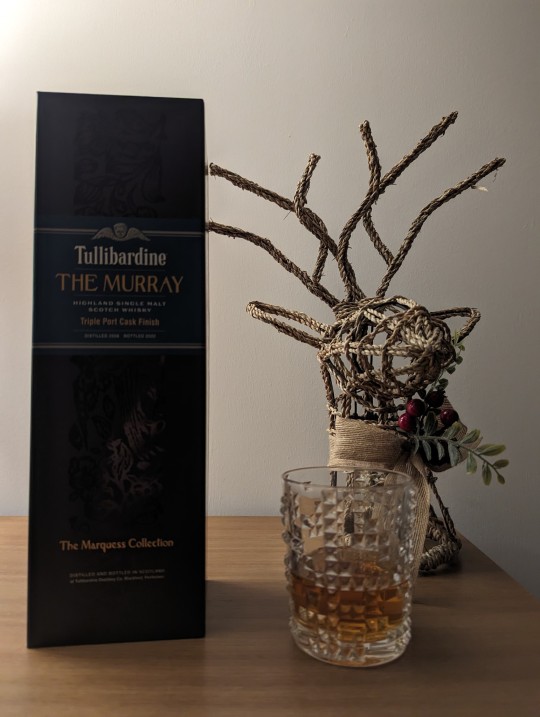

#tullibardine

Text

#whisky#whiskycollection#whiskylife#whiskylover#whiskycollector#scotch#singlemalt#whisky glass#distillery#classy life#tullibardine

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tullibardine 1990 25 year old Old & Rare Hunter Laing.

I would withhold detailed comment as enjoyed conversation with drinking. Comfortable conifers and mint, ripe peach nuances.

0 notes

Text

Tullibardine 500 Sherry Finish

Review by: TOModera

(Thanks to usquebaugh_ for the dram)

Gather round, whisky swiggers and jiggers, for I have a story to tell. A simple story for two denari, of times before in the whisky network.

Scoff all you want good sir, but yes, there was a time when this network was smaller, without fools telling stories like a bard in order to spice up reviews.

During this dark time, we had quarterly…

View On WordPress

#Highland#Rated 70-74#Scotch#Scotch Review#Sherry Cask#Single Malt#TOModera#Tullibardine#Whisky Review

0 notes

Text

This is my husband. I am Lady Tullibardine

0 notes

Text

Prince Charles Edward Stuart, landed in Eriskay with his “Seven men of Moidart" on 23rd July 1745.

The Seven Men of Moidart consisted of four Irishmen, two Scots and one Englishman. Three of the group were elderly men, Sir Thomas Sheridan (the Prince’s under-governor/tutor and a veteran cavalry officer), Sir John MacDonald (a former French cavalry officer) and the Scot William Murray (Marquis of Tullibardine). These were accompanied by the Irish Colonel, John William O’ Sullivan (French army) and Irish Episcopalian clergyman, Reverend George Kelly, the Englishman, Francis Strickland ( a former royal tutor), as well the Scot, Aeneas MacDonald ( a Paris banker).

Having lost their arms and ammunition, as I told you in my post about the encounter with a british ship enroute, his companions besought the Prince to return to Nantes, but he refused and after a chase by a British man-of-war, La Doutelle anchored off the island of Eriskay, in the Outer Hebrides, on 2nd August, 1745. An eagle hovered round the ship, and Tullibardine exclaimed "Here is the king of birds come to welcome your Royal Highness to Scotland."

Clanranald to whom the cluster of islands belonged, was on the mainland. Charles proceeded, and entered the bay of Loch-nan-nuah between Moidart and Arisaig. Here Clanranald, Kinloch Moidart, and several of their clansmen came on board. But to the Prince's pleas, they answered that to take up arms without concert or support from France could only end in ruin. After a long interview and a personal appeal to young Kinloch Moidart, the brother of the chief, Charles at length prevailed, perhaps shoeing the charm if the man the Government labelled, The Young Pretender.

The pics include two memorial cairns on the island.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Most Honourable Michael Bruce John Murray, Marquess of Tullibardine.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Balvaird Castle in Perthshire.

It is a traditional late medieval Scottish tower house. It is located in the Ochil Hills, around 5 kilometres south of Abernethy. The name Balvaird is from Baile a' Bhàird, 'Township of the Bard' in Gaelic.

Balvaird was built around the year 1495 for Sir Andrew Murray, a younger son of the family of Murray of Tullibardine.

He acquired the lands of Balvaird through marriage to the heiress Margaret Barclay, a member of a wealthy family and daughter of James Barclay of Kippo. It is likely that Balvaird Castle was built on the site of an earlier Barclay family castle.

Substantial remnants of earthwork fortifications around the Castle may survive from earlier defences.

Balvaird is first mentioned in the written historical record in 1498 as 'the place of Balward' in the Register of the Great Seal of Scotland.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

the noble house of tremblay

title(s):

duke of atholl

marquess of tullibardine

earl of strathtay and strathardle

viscount of balquhidder, glenalmond and glenlyn

legislative votes:

eighteen

judicial votes:

four

is not sacred twenty eight

political ideology:

light

seat:

blair castle

0 notes

Text

A Book of Days

Two Christmas presents from my husband this year, a bottle of Tullibardine, and this beautiful book, Pattie Smith’s A Book of Days. When we saw her perform at The Bearded Theory festival last May, she began her set by reciting the footnote to Alen Ginsberg’s Howl, ‘Holy, holy, holy’, and she spoke it with such conviction the poem could have been hers. Everything is holy … ‘Holy the supernatural…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#whisky#whiskycollection#whiskylife#whiskylover#whiskycollector#scotch#singlemalt#whisky glass#distillery#classy life#tullibardine

1 note

·

View note

Text

Quirky little hidden gem found in the carpark of the Tullibardine Whisky Distillery

0 notes

Text

Tullibardine launch Custodian Club for biggest supporters

Tullibardine launch Custodian Club for biggest supporters #whisky #news

We’re excited to announce that we’ve created a new VIP membership especially for our biggest supporters called the Custodian Club. Members will receive a whole host of offers, exclusive discounts at the distillery, first access to new releases, and a say in new bottlings among many other benefits.

Back in April, we asked our fans what type of brand involvement they would like to see in our…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

26th August 1565 saw Mary Queen of Scots lead an army out of Edinburgh to suppress a rebellion led by her half brother James Stewart.

This was all today with Mary's decision to Marry Lord Darnley, Moray, who was strongly opposed to Henry Stuart’s family, decided to rebel against Mary. He was joined by Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll and James Hamilton, Duke of Châtellerault in March 1565.

With strong support and an army of 5000 men, Mary was determined to pursue the rebels. It turned into a "Chase about" Scotland, hence the name it was given Chaseabout Raid.

The rebels gathered in Ayrshire. Mary set out from Holyroodhouse to Linlithgow and Stirling on 26 August 1565 to move to Glasgow and confront them. Her cannon followed, brought by John Chisholm, who had obtained funds from the Burgh of Edinburgh after Mary promised the town rights over Leith. The treasurer of the Scottish exchequer, John Wishart of Pitarro, had sided with the rebellion and was replaced by William Murray of Tullibardine. The Provost of Edinburgh was also removed and Simon Preston of Craigmillar, a friend of Mary put in his place. William Murray's lands were raided by Highlanders. On 31 August, Moray and his supporters arrived in Edinburgh, this is where the chase thing comes into it The rebel lords left Edinburgh. Mary came back to Edinburgh in early September and retired to Stirling, then back to Glasgow. Moray's supporters retreated to Dumfries.

The rebels had really little support Moray and his supporters numbered between 1,000 or 1,200 men and as a result they could not seize power. They waited in Dumfries for Elizabeth I to send help. She refused to give it as it may have set a precedent for nobles within England to turn against their monarch. The rebellion was over

The rebels crossed the border at Carlisle, then made their way to Newcastle upon Tyne. Moray decided to go to London, and got as far as Royston in Hertfordshire, until he received a letter from Elizabeth I of England to stop as he was not invited and a rebel against his own queen. He was then brought to Westminster on 23 October 1565 to explain himself to Elizabeth and the French ambassadors.

Elizabeth said to him that "itt were no Prince's part to think well of your doinges, ... and, she wolde putt allso her helping hande too make them to understand the dutye which the subject owght to bear towarddes the Prynce." Moray declared he had not intended anything to the danger of Mary's person.

Moray stayed in England at Newcastle over the winter and returned to Scotland on 10 March 1566. Mary had summoned him for trial, and David Rizzio had just been murdered. Moray was reconciled with Mary and back on the Scottish Privy Council by 29 April 1566.

You wonder why Mary pardoned Moray, but he was her half brother and with Rizzio's murder she must have been thinking, she should have listened to him in the first place?

Just another chapter in the complexities of Mary's time trying to rule her Country.in a world dominated by men and religious zealots.

Pics are Mary and Moray.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Most Honourable Michael Bruce John Murray, Marquess of Tullibardine.

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Places to Go: Tullibardine Chapel

A small kirk sheltered by Scots pines, Tullibardine Chapel has an air of tranquility and simple elegance. Formerly the private chapel of the Murrays of Tullibardine, it is one of the few buildings of its kind in Scotland to have survived with many of its medieval details intact.

The Murrays acquired the lands of Tullibardine in the late thirteenth century, when William ‘de Moravia’ married a daughter of the steward of Strathearn. Later, through judicious marriages and court connections, they first became earls of Tullibardine and then Dukes of Atholl. But even as lairds the Murrays were a significant power in late mediaeval Perthshire. In those days Tullibardine Castle was one of their main strongholds, and the close proximity of royal residences like Stirling meant that the Castle also hosted several notable guests. Mary, Queen of Scots, stayed there in December of 1566 (allegedly in the company of the earl of Bothwell). One laird of Tullibardine became Master of Household to the young James VI, while his aunt Annabella Murray, Countess of Mar, oversaw the king’s upbringing. Thus James VI was also a frequent visitor and it was he who created the earldom of Tullibardine in 1606. The king is known to have attended the wedding of the laird of Tullibardine’s daughter Lilias Murray, though it is unclear whether this took place at Tullibardine itself. The castle grounds were probably an impressive sight too: the sixteenth century writer Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie claimed that a group of hawthorns at the “zeit of Tilliebairne”* had been planted in the shape of the Great Michael by some of the wrights who worked on the famous ship.

Thus the tower at Tullibardine, though presumably on a small-scale, was apparently comfortable and imposing enough for the lairds to host royalty and fashion an impressive self-image. But the spiritual needs of a late mediaeval noble family were just as important as their political prestige, and a chapel could both shape the family’s public image and secure their private wellbeing. The current chapel at Tullibardine, which originally stood at a small distance from the castle, was allegedly founded by David Murray in 1446, “in honour of our blessed Saviour”. At least this was the story according to the eighteenth century writer John Spottiswoode, and his assertion is partly supported by the chapel’s internal evidence, though no surviving contemporary document explicitly confirms the tale. A chapel certainly existed by 1455, when a charter in favour of David’s son William Murray of Tullibardine mentions it as an existing structure. In this charter, King James II stated that his “familiar shieldbearer” William Murray has “intended to endow and infeft certain chaplains in the chapel of Tullibardine”. Since the earls of Strathearn had previously endowed a chaplain in the kirk of Muthill, but duties pertaining to the chaplaincy had not been undertaken for some time, James transferred the chaplaincy to Tullibardine. He also granted his patronage and gift of the chaplaincy to William Murray and his heirs.

The charter indicates that Tullibardine Chapel was an important project for the Murrays. Interestingly though, no official references to the chapel in the fifteenth, sixteenth, or seventeenth centuries describe Tullibardine chapel as a collegiate church, even though later writers have frequently claimed this. Collegiate foundations were increasingly popular with the Scottish nobility during the late Middle Ages, but, although such a foundation might have been planned for Tullibardine, there is no evidence that this ever took place.

The 1455 charter serves as an early indication of the chapel’s purpose and significance. Judging by its architecture the current chapel does appear to have been constructed in the mid-fifteenth century. However it was also substantially remodelled and enlarged around 1500, when the western tower was added. One remnant of the original design is the late Gothic ‘uncusped’ loop tracery on the windows. Despite the apparent simplicity of the chapel, features such as this window tracery have been taken as evidence that its builder was acutely aware of contemporary European architectural fashions. Another interesting feature is the survival of the chapel’s original timber collarbeam roof, a rare thing in Scotland. Several coats of arms belonging to members of the Murray family adorn the walls and roof corbels, although some of these armorial panels were probably moved when the chapel was reconstructed. They include the arms of the chapel’s alleged founder David Murray and his wife Margaret Colquhoun, as well as those of his parents, another David Murray and Isabel Stewart. A later member of the family, Andrew Murray, married a lady named Margaret Barclay c.1499, around the same time that the chapel was renovated, and although they were buried elsewhere, their coats of arms can also be seen there. Aside from such details- carved in stone and thus less perishable than books and vestments- the chapel’s interior seems quite sparse and bare today. Originally though the mediaeval building probably housed several richly furnished altars and some of the piscinas (hand-washing stations for priests) can still be seen in the walls. But the sumptuous display favoured in even the smallest mediaeval chapels was soon to be swept away entirely by the Reformation of 1560, when Scotland broke with the Catholic Church and Protestantism became the established faith of the realm.

Tullibardine was used chiefly as a private burial place after the Reformation, but there are signs that the transition from one faith to another was not entirely smooth. Four years after the “official” Reformation, a priest named Sir Patrick Fergy was summoned before the “Superintendent” of Fife, Fothriff, and Strathearn to answer the charge that he had taken it upon himself “to prech and minister the sacramentis wythowtyn lawfull admission, and for drawing of the pepill to the chapel of Tulebarne fra thar parroche kyrk”. Fergy did not obey the summons and so it was decided that he should be summoned for a second admonition. It is not known whether Fergy compeared on that occasion, nor what kind of punishment he might have received for his defiance. We are also in the dark as to the laird of Tullibardine’s views on the situation, even though it was going on right under his family’s nose. Nonetheless the case does provide a glimpse into what must have been a complex religious situation in sixteenth century Perthshire, no less for the ordinary parishioner than for the nobility. It also raises the possibility that private worship continued in the chapel after the Reformation, albeit unofficially.

Even as Tullibardine chapel’s public role diminished, the castle was still of some importance. Royal visits must have been considerably rarer after James VI succeeded to the English throne in 1603, and the Murrays of Tullibardine themselves acquired greater titles and estates, but the tower at Tullibardine still witnessed some notable events. During the first half of the eighteenth century, the castle was the home of Lord George Murray, a kinsman of the Duke of Atholl and famous for his participation in the Jacobite Risings of 1715, 1719, and 1745. During the last of these, Tullibardine Castle played host to a Jacobite garrison and was visited by Charles Edward Stuart. In less warlike times, Lord Murray often resided with his family at Tullibardine, and one of his daughters, who sadly died in infancy, seems to have been buried in the chapel. Lord George himself expressed a wish to be buried there as well but he was forced to flee into exile on the continent after the failure of the ’45, and so his body was interred “over the water” at Medemblick, in the Netherlands.

After Lord George’s exile Tullibardine castle entered a period of slow decline. Much of the fabric of the building was removed in 1747. Some years earlier plans had been made for the old tower to be replaced by a fashionable new house designed by William Adam, but these never materialised. A sketch of the mediaeval chapel made in 1789 shows the castle in the background- a roofless, tumbledown ruin. Tullibardine castle was finally demolished in 1833, and the family chapel, whose very existence had for centuries been defined by its proximity to the laird’s house, now stands alone. We are thus all the more fortunate for its survival, and both its attractive situation and interesting mediaeval features make Tullibardine chapel well worth a visit.

(Tullibardine Chapel, with the castle ruins in the background, as sketched in 1789. Reproduced with permission of the National Libraries of Scotland, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License)

Sources and notes may be found under the ‘read more’ button.

* “zeit” is presumaby “yett”, the old Scots word for gate.

Selected Bibliography:

- “Account of All the Religious Houses That Were in Scotland at the Time of the Reformation”, by John Spottiswood, in “An Historical Catalogue of the Scottish Bishops Down to the Year 1688″, by Reverend Robert Keith.

- Seventh Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Part 2 (Duke of Atholl papers)

- “Register of the Ministers, Elders, and Deacons of the Congregation of St Andrews”, volume 4, Part 1 (St Andrews Kirk Session Register), edited by David Hay Fleming

- “Statement of Significance: Tullibardine Chapel”, Historic Environment Scotland

- “The Historie and Croniclis of Scotland From the Slauchter of King James the First to the Ane Thousande Five Hundreith Thrie Scoir Fiftein Zeir”, by Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie, volume 1 edited Aeneas J. G. Mackay.

- “Late Gothic Architecture in Scotland: Considerations on the Influence of the Low Countries”, by Richard Fawcett in ‘Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland’, 112 (1982)

- “Aspects of Timber in Renaissance and Post-Renaissance Scotland: The Case of Stirling Palace”, Thorsten Hanke

- “Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland”, Vol. 5, ed. M. Livingstone

- “The Household and Court of King James VI”, Amy L. Juhala

- “Memoirs of the Affairs of Scotland”, by David Moysie, ed. James Dennistoun for the Bannatyne Club

- “Calendar of State Papers, Scotland”, Volume 10, 1589-93, ed. William K. Boyd and Henry W. Meikle

- “The Indictment of Mary Queen of Scots, as Derived from a Manuscript in the University Library at Cambridge, Hitherto Unpublished”, by George Buchanan, edited by R.H. Mahon

#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#Perthshire#Places to go#Strathearn#Tullibardine Chapel#Tullibardine#Auchterarder#fifteenth century#sixteenth century#eighteenth century#1450s#1500s#building#architecture#Gothic Architecture#kirk and people#religion#Church#Christianity#private chapel#chapel#Murray family#Murrays of Tullibardine#Murray#Duke of Atholl#Jacobites#James VI#Mary Queen of Scots

9 notes

·

View notes