#tumblr's guide to shostakovich

Text

Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich: Part 2- Background and Beginnings

Hello, and welcome back to Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich, the series where I talk about the life and works of Dmitri Shostakovich! Today, I want to talk some about his family background, and about his childhood. The main sources I'll be using for this post are Dmitri Shostakovich: The LIfe and Background of a Soviet Composer by Victor Seroff and Nadezhda Galli-Shohat (who was Shostakovich's aunt), Pages From the Life of Dmitri Shostakovich by Dmitri and Lyudmila Sollertinsky, and Shostakovich: A Life Remembered by Elizabeth Wilson. Photos are from Dmitri Shostakovich: The Life and Background of a Soviet Composer and the DSCH Publishers website.

Dmitri Shostakovich was born on September 25, 1906, to Dmitri Boleslavovich and Sofiya Vasiliyevna (nee Kokaoulina) Shostakovich in St. Petersburg, Russia. His maternal grandfather, Vasiliy Jakovlevich Kokaoulin, hailed from Siberia and advocated for improved working conditions for miners in the Lena Gold Field, where he became the manager. Sofiya Vasiliyevna was one of six children, and studied music at the Irkutsk Institute for Noblewomen; her brother Jasha became involved with the growing revolutionary movement. When a student protest on Kazan Square in February 1899 was violently disbanded by armed Cossacks, Sofiya and her siblings became more deeply sympathetic towards the revolutionaries; her sister Nadezhda Galli-Shohat would become a member of the Social Democratic Bolshevik Party (she would later come to disagree with Bolshevism and emigrate to the United States in 1923).

(Sofiya Vasiliyevna Shostakovich, the composer's mother. 1911.)

Shostakovich's father, Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, came from Polish origins ("Shostakovich" is actually a Russification of the Polish surname "Szostakowicz.") and worked as a senior keeper at the Palace of Weights and Measures. His father, Boleslav, was deeply involved in the Polish revolutionary movement, and organized the release of Jaroslav Dombrovsky, who had been imprisoned due to his part in the Polish Uprising. As a result, Boleslav was exiled to Siberia. (Side note- Shostakovich's first name was nearly "Jaroslav," but the Orthodox priest at his christening advised his parents to name him "Dmitri," after his father.)

(Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer's father. 1903.)

(The composer around age one and his sister Maria ("Marusya"), 1907.)

By the time Shostakovich's parents were raising their three children in a middle-class household on Nikolaevskaya Street, revolutionary sentiments were sharply rising; Shostakovich himself was born just a year after the "Bloody Sunday" massacre of 1905. However, another major component of the artist young Mitya Shostakovich would become was highly present in their home- music. His mother was a skilled pianist, and his father- a "kind, jolly man" who would sing to her accompaniments. Shostakovich would listen to his neighbour, Boris Sass-Tisovsky, play the cello, and the Shostakoviches would take their children to the opera. Seroff and Galli-Shohat include an anecdote illustrating the contrasting personalities of Sofiya and Dmitri B. Shostakovich:

"Sonya [Sofiya] gradually weeded out most of the Siberian friends of Dmitri's [Boleslavovich] student days because, for her, there was too much of the "muzhik" [term for a male peasant] about them and in these days she sought a different society. Dmitri took all this reform very good-naturedly and only retained, in spite of all that Sonya could do, his heavy gait and his rough, Siberian-peasant way of speaking. Sonya would have despaired of his slangy speech except that she knew his gay and lovable disposition always won him friends wherever he went. "Sonya, Sonya," he would say, shaking his head and looking at her over the top of his glasses, "I'm a bad one. Squirt me another glass of tea."

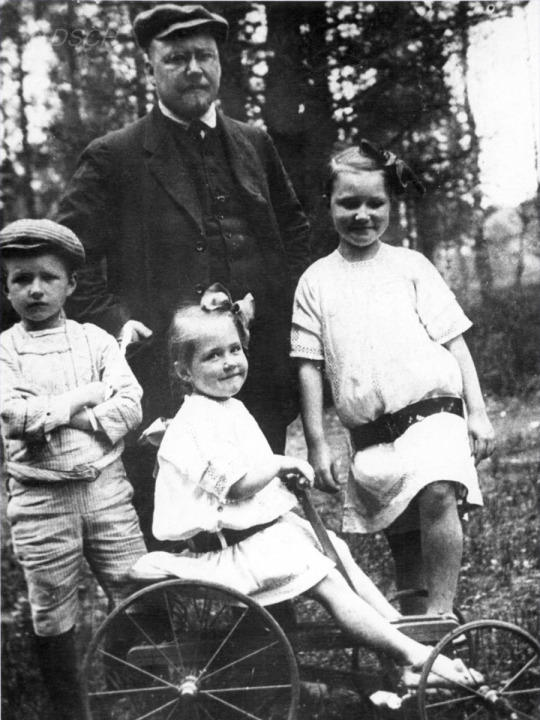

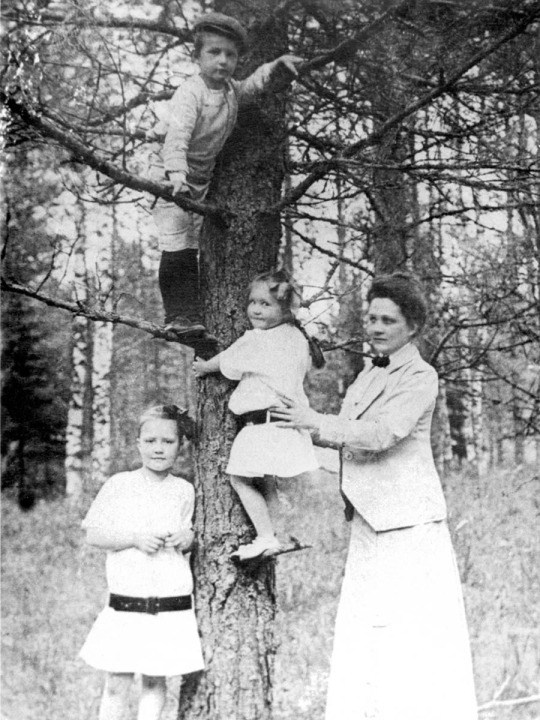

(Mitya, Maria, and Zoya Shostakovich with their parents, 1912.)

Despite an early recognition of his talents as a prodigy, Shostakovich was never pressed into music unwillingly; for the most part, he had a happy childhood with his sisters Zoya and Maria, gathering mushrooms, reading adventure books, and watching their father play solitaire (which would later become one of Shostakovich's favourite pastimes as well). However, at the age of nine, after attending a performance of Mussorgsky's The Tale of Tsar Saltan, Mitya was able to recite and sing most of the opera from memory the following day. That summer, in 1915, he began piano lessons. Among his first childhood works was the "Funeral March for Victims of the Revolution;" he recalled that he "composed a lot under the influence of external events," a trait that would come to follow him throughout his future career. He took lessons from Ignati Glyasser, and later Aleksandra Rozanova. By the time he entered the conservatoire at age thirteen, the city he was born in had been renamed to Petrograd; WWI had meant a Russification of the name "St. Petersburg" due to anti-German sentiment. In 1924, it would once again be renamed "Leningrad," following the death of Vladimir Lenin. (Today, the city is once again called "St. Petersburg," following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.) Shostakovich's enrollment was on the recommendation of the composer and professor Aleksandr Glazunov, who would play a highly significant role in his conservatory years.

(Aleksandra Aleksandrovna Rozanova, Shostakovich's piano teacher.)

(Ignati Albertovich Glyasser with his piano class, 1917. Dmitri Shostakovich is located second from the right in the first row; Maria Shostakovich is located fourth from the right in the second row.)

In the next few entries, I will talk more about his adolescence and conservatory years, along with some drama in his personal life. ;) See you then!

#dmitri shostakovich#classical music#music history#soviet history#russia#classical music history#composer#russian history#shostakovich#tumblr's guide to shostakovich

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since I keep seeing Falsehoods and Misinformation being propagated here on Tumblr dot com, here is a pronunciation guide for the names of famous composers.

Chopin: this should be pronounced like "choppin'", as in "I'll be off Chopin some wood"

Beethoven: People seem to think that this should be pronounced like the name of the dog in those family comedies from the 90s, but actually It's more like "Bee (as in 'Bee Movie') THO-ven"

Paganini: This is actually pronounced like "Peg-a-Ninny"; once you hear it, it should be easy enough to remember

Stravinsky: So this one's a bit confusing, because of course Stravinsky was Russian, and Russian doesn't actually use the Latin Alphabet, so most of the letters are silent and the 'v' is pronounced like a 'u'. As a result, the correct way to pronounce Stravinsky actually sounds like "Strauss". This has led to a lot of confusion and caused some people to think that there are two separate composers, but they're really the same guy.

Shostakovich: Another Russian, whose name, confusingly, is also pronounced "Strauss". To avoid confusion with Stravinsky above, a lot of people call him "Strauss II"

Bartok: Difficult to render in English, but if you read it as "BAAAAHHR-tok!" you're not far off

Debussy: Conveniently, this is pronounced exactly as it looks like it should be: "Da Bussy"

Anyways, I think that that about covers it. Go forth and impress your friends by pronouncing these names correctly.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich- Asides- Ivan Sollertinsky

So, in addition to my weekly posting for Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich, I decided I want to do a series of related "asides" posts. These will be posted irregularly (as opposed to weekly) and cover aspects related to Shostakovich that don't fit neatly into one post focusing on one part of the chronological timeline. In this case, I want to talk about Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky, specifically his role in Shostakovich's life and music. Sources I'll be citing include Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Shostakovich's own letters to Sollertinsky and Isaak Glikman, Dmitri and Lyudmila Sollertinsky's Pages from the Life of Dmitri Shostakovich, Pamyati I.I. Sollertinskogo (Memories of I.I. Sollertinsky), and I.I. Sollertinsky: Zhizn' i naslediye (Life and Legacy), the latter two both by Lyudmila Mikheeva. Photo citations include the DSCH Publishers website and the DSCH Journal photo archive.

(Dmitri Shostakovich and Ivan Sollertinsky, Novosibirsk, 1942.)

Ivan Ivanovich Sollertinsky was born in Vitebsk, present-day Belarus, on December 3, 1902. He was a polymath, excelling in humanities fields, including linguistics, philosophy, musicology, history, and literature- particularly that of Cervantes. He specialized in Romano-Germanic philology, and spoke a wide range of languages; sources I've read vary from claiming he spoke anywhere from 25 to 30. (He specialized in Romance languages, but I can also confirm from sources that he studied Hungarian, Japanese, Greek, Sanskrit, and German. I've heard it said that he kept a diary in ancient Portuguese so nobody could read it, but I haven't seen this verified.) He had a ferocious wit, which he used to uplift friends and skewer enemies (there's a hilarious anecdote where he once saddled a critic opposed to Shostakovich with the nickname "Carbohydrates" for life), and worked as a professor, orator, and artistic director of the Leningrad Philharmonic. And yet, this impossibly bright star would burn out all too soon at the age of 41 due to a terminal heart condition, leaving his closest friend devastated- and inspired.

Dmitri Shostakovich first met Ivan Sollertinsky in 1921, when they were both students at the Petrograd Conservatory. While Shostakovich claimed he was at first too intimidated to talk to Sollertinsky the first time he saw him, when they met again in 1926, Shostakovich was waiting outside a classroom to take an exam on Marxism-Leninism. When Sollertinsky walked out of the classroom, Shostakovich "plucked up courage and asked him":

"Excuse me, was the exam very difficult?"

"No, not at all," [Sollertinsky] replied.

"What did they ask you?"

"Oh, the easiest things: the growth of materialism in Ancient

Greece; Sophocles' poetry as an expression of materialist tendencies; English seventeenth-century philosophers and something else besides!"

Shostakovich then goes on to state he was "filled with horror at his reply."

(...Yes, these are real people we are talking about. According to Shostakovich, this actually happened. And I love it.)

Later, in 1927, they met at a gathering hosted by the conductor Nikolai Malko, where they hit it off immediately. Malko recalls that they "became fast friends, and one could not seem to do without the other." He further characterizes their friendship:

When Shostakovich and Sollertinsky were together, they were always fooling. Jokes ran riot and each tried to outdo the other in making witty remarks. It was a veritable competition. Each had a sharply developed sense of humour; both were bright and observant; they knew a great deal; and their tongues were itching to say something funny or sarcastic, no matter whom it might concern. They were each quite indiscriminate when it came

to being humorous, and if they were too young to be bitter they could still come mercilessly close to being malicious.

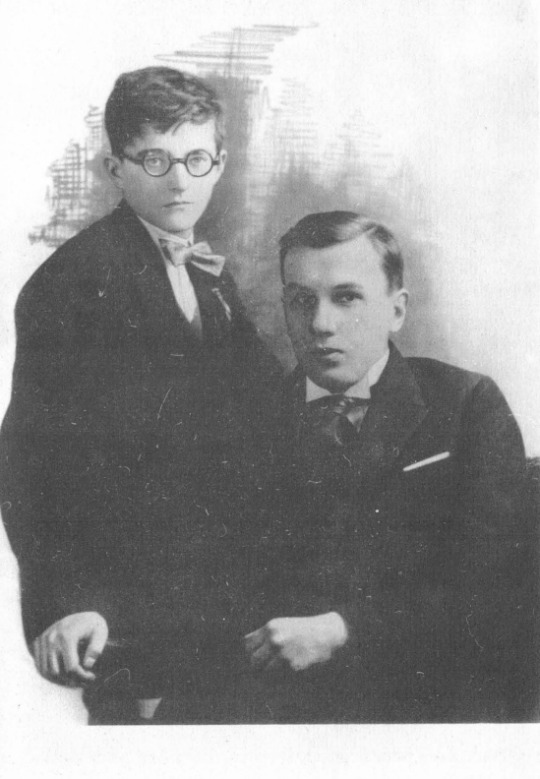

(Shostakovich and Sollertinsky, 1920s.)

Sollertinsky and Shostakovich appeared to be perfect complements of each other- one brash, extroverted, and confident, and the other shy, withdrawn, and insecure, but each sharing a sarcastic sense of humour and love for the arts that would carry throughout their friendship. In Shostakovich's letters to Sollertinsky, we see him confide in him time and again, in everything from drama with women to fears in the midst of the worsening political atmosphere. When worrying about the reception of his ballet "The Limpid Stream," Shostakovich writes in a letter from October 31, 1935:

I strongly believe that in this case, you won't leave me in an extremely difficult moment of my life, and that the only person whose friendship I cherish, the apple of my eye, is you.

So, write to me, for god's sake.

And, in a moment of frustration from August 2, 1930 Shostakovich writes:

"You have a rich personal life. And mine, generally, is shit."

(Famous composers, am I right? They're just like us.)

In addition to a friendship that would last until Sollertinsky's untimely death, he and Shostakovich would influence each other greatly in the artistic spheres as well. Sollertinsky dedicated himself primarily to musicology after meeting Shostakovich (his first review of an opera, Krenek's Johnny, appeared in 1928, after they had become friends), and in turn, Sollertinsky introduced Shostakovich to one of his greatest musical inspirations- the works of Gustav Mahler. Much is to be said about Mahler's influence on Shostakovich's music, to the point where it deserves its own post, but it goes without saying that without Sollertinsky, Shostakovich's entire body of work would have turned out much differently. Starting with the Fourth Symphony (1936), Shostakovich's symphonic works began to take on a heavily Mahlerian angle (in addition to many vocal works), becoming a permanent fixture in his distinct musical style.

(Colorized image of Shostakovich, his wife Nina Vasiliyevna, and Sollertinsky, 1932. One of my absolute favourite photographs.)

Shostakovich's letters to Sollertinsky, from the 20s to early 30s, are characterized by puns and literary references, snide remarks, nervous confessions, and vivid descriptions of the locations he traveled to during his early career. However, as the 1930s progressed and censorship in the arts became more restrictive, signs of worry begin to take shape in the letters. This would all culminate in January 1936, with the denunciation of Shostakovich's opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in Pravda. I'll go further into detail about the opera and its denunciation in a later post, but for now, I want to focus on its impact on Shostakovich and Sollertinsky's friendship.

As one of the first world-famous composers whose career began in the then-relatively young Soviet Union, targeting Shostakovich proved to be a calculated move. Due to his prominence and the acclaim he had previously received, both in the USSR and abroad, the portrayal of Shostakovich as a "formalist" meant someone had to take the blame for his supposed "corruption" towards western-inspired music and the avant-garde. The blame fell upon Sollertinsky, who was lambasted in the papers as the "troubadour of formalism." To make matters worse, Sollertinsky had long showed a fascination with western European composers, such as the Second Viennese School, and had previously praised Lady Macbeth in a review as the "future of Soviet art." An article in Pravda from February 14, 1936, about less than a month after the denunciation, stated:

“Shostakovich should in his creation entirely free himself from the disastrous influence of the ideologists of the ‘Leftist Ugliness’ type of Sollertinsky and take the road of truthful Soviet art, to advance in a new direction, leading to the sunny kingdom of Soviet art.”

Critics who had initially praised Lady Macbeth had begun to retract their positive reviews in favour of negative ones, and a vote was cast on a resolution on whether or not to condemn the opera. According to Isaak Glikman, their mutual friend, Shostakovich spoke with Sollertinsky, who was conflicted on what to do, beforehand. Although Sollertinsky didn’t want to condemn his friend, he supposedly told Glikman that Shostakovich had given him permission to “vote for any resolution whatsoever, in case of dire necessity.” When denouncing the opera (supposedly with Shostakovich's permission), Sollertinsky had commented that in order to develop a “true connection” to the Soviet public, Shostakovich would have to develop a “true heroic pathos, and that Shostakovich would ultimately succeed “in the genre of Soviet musical tragedy and the Soviet heroic symphony.” After Shostakovich’s second denunciation in Pravda of his ballet, “The Limpid Stream,” and the withdrawal of his Fourth Symphony- arguably the most Mahlerian of his middle period works- the Fifth Symphony, easily interpreted to follow these criteria, had indeed restored him to favour. Sollertinsky’s reputation, too, was saved.

(Aleksandr Gauk, Shostakovich, Sollertinsky, Nina Vasiliyevna, and an unidentified person, 1930s.)

In 1938, Sollertinsky contracted diphtheria. Ever tireless, he continued to dictate opera reviews and even learned Hungarian while hospitalized, although he became paralyzed in the limbs and jaw. Shostakovich wrote to him often with touching concern:

Dear friend,

It's terribly sad that you are spending your much needed and precious vacation still sick. In any case, when you get better, you need to get plenty of rest.

By the time the letters from this period break off, it's because Shostakovich was able to visit Sollertinsky in the hospital, which he did whenever he was able.

While Sollertinsky was able to recover, their friendship would face yet another test in 1941, due to the German invasion of the Soviet Union during WWII. Sollertinsky evacuated with the Leningrad Philharmonic to Novosibirsk, while Shostakovich chose to stay in Leningrad. However, as the city fell under siege, due to the safety of his family, Shostakovich fled with Nina Vasiliyevna and their two children to Kubiyshev (now Samara) that October, having spent about a month in Leningrad during what would be one of the deadliest sieges of the 20th century. It was in Kubiyshev that Shostakovich would finish his famous Seventh Symphony (which, again, will receive its own post), before eventually moving permanently to Moscow (although he still taught for a time at the Leningrad Conservatory).

During this period of evacuation, Shostakovich's letters to Sollertinsky are heartbreaking. We not only see him pining for his friend, but worrying for his safety and that of his family, including his mother and sister, who were still in Leningrad at the time. Still, he reminisces of their time together before the war, with the hope that he and Sollertinsky would be back home soon. In a letter from 12th February, 1942:

Dear friend, I painfully miss you, and believe that soon, we will be home, and will visit each other and chat about this and that over a bottle of good Kakhetian no. 8 [a Georgian wine]. Take care of yourself and your health. Remember: You have children for which you are responsible, and friends, and among them is D. Shostakovich.

In 1943, Sollertinsky arrived in Moscow, where Shostakovich was living at the time, to give a speech on the anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s death. At long last, they finally were able to see each other, and anticipated that soon enough, their long period of separation, made bearable only by letters and phone calls, would come to an end: Sollertinsky, living in Novosibirsk, was planning to return to Moscow in February of 1944 to teach a course on music history at the conservatory. When he and Shostakovich said their goodbyes at the train station, neither of them knew it would be the last time they saw one another.

Sollertinsky's heart condition, coupled with his tendency to overwork, poor living conditions, heavy drinking, and added stress, often left him fatigued. On the night of February 10th, 1944, due to a sudden bout of exhaustion, he stayed the night with conductor Andrei Porfiriyevich Novikov, where he died unexpectedly in his sleep. His last public appearance had been the speeches he gave on February 5th and 6th of that year- the opening comments for the Novosibirsk premiere of Shostakovich’s 8th Symphony. A remarkable amount of telegrams and letters from Shostakovich to Sollertinsky survive and have been published in Russian. Some seem hardly significant; others carry great historical importance. Sollertinsky took many of them with him from Leningrad during evacuation; those letters were considered among his most prized possession. His son, Dmitri Ivanovich Sollertinsky, was named after Shostakovich- breaking a long tradition in his family in which the first son was always named "Ivan."

As for Shostakovich, we have letters to multiple correspondents detailing just how distraught he was for months after receiving news via telegram of Sollertinsky’s death. To Sollertinsky’s widow, Olga Pantaleimonovna Sollertinskaya, he wrote:

“It will be unbelievably hard for me to live without him. [...] In the last few years I rarely saw him or spoke with him. But I was always cheered by the knowledge that Ivan Ivanovich, with his remarkable mind, clear vision, and inexhaustible energy, was alive somewhere. [...] Ivan lvanovich and I talked a great deal about everything. We talked about that inevitable thing waiting for us at the end of our lives- about death. Both of us feared and dreaded it. We loved life, but knew that sooner or later we would have to leave it. Ivan lvanovich has gone from us terribly young. Death has wrenched him from life. He is dead, I am still here. When we spoke of death we always remembered the people near and dear to us. We thought anxiously about our children, wives, and parents, and always solemnly promised each other that in the event of one of us dying, the other would use every possible means to help the bereaved family. ”

Shostakovich stuck to his word, making arrangements for Sollertinsky's surviving family to return to Leningrad after it had been liberated, going through the painstaking process of acquiring the necessary documentation and allowing them to stay at his home in Moscow in the meantime.

In 1969, he would write to Glikman:

“On 10 February, I remembered Ivan Ivanovich. It is incredible to think that twenty-five years have passed since he died.”

Furthermore, Shostakovich recalled:

Ivan Ivanovich loved different dates. So he planned to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of our acquaintance in the winter of 1941. This celebration did not take place, since the war had ruined us. When in our last meetings, we planned the 25th anniversary of our friendship for 1947. But in 1947, I will only remember that twenty-five years ago life sent me a wonderful friend, and that in 1944 death took him away from me.

And yet, there was still one more tribute left to make. Shostakovich had already dedicated a movement of a work to Sollertinsky- a setting of Pasternak's translation of Shakespeare Sonnet no. 66 in Six Romances on Verses by English Poets- but after Sollertinsky's death, he completed his Piano Trio no. 2 in August of 1944, a work that had taken months to finish. While he had started the work before Sollertinsky's death and mentions it in a letter to Glikman as early as December 1943, it would since bear a dedication to Sollertinsky's memory.

The second movement of the Trio is a dizzying, electrifying Allegro con Brio- and probably my favourite work of classical music, ever. Sollertinsky's sister, Ekaterina Ivanovna, was said to have considered it a "musical portrait" of her illustrious brother in life, with its fast-paced, jubilant air. The call-and-response between the strings and piano seem, to me, to reflect one of Shostakovich and Sollertinsky's early Leningrad dialogues- the image of two friends out of breath with laughter, each talking over each other as they deliver witty comebacks and jokes that only they understand. For the few minutes that this movement lasts, it is as if Shostakovich and Sollertinsky are revived, if not for just a moment, the unbreakable bond that defied decades of hardship now immortalized in the classical canon, forever carefree and happy in each other's company.

And then comes the pause.

It is this silence between the Allegro con Brio and Adagio that is the loudest, most powerful moment of this piece as eight solemn chords snap us into reality, like the sudden revelation of Sollertinsky's death- as Shostakovich said, "he is dead; I am still here." These eight chords form the base of a passacaglia, the piano cycling through them and nearly devoid of dynamics as the cello and violin sing a lugubrious dirge. The piano- Shostakovich's instrument- seems to mirror the stasis of grief, the inability to move on when paralyzed by loss.

The final movement of the Trio, the Allegretto, seems to speak to a wider form of grief. By 1943, the Soviet Union was receiving news of the Holocaust, and the Allegretto of Shostakovich's Trio no. 2 is among the first instances of Klezmer-inspired themes in Shostakovich's work (not counting the opera Rothschild's Violin, a work by his student Veniamin Fleischman that he finished after Fleischman's death in the war). The idea that the fourth movement is a commentary on the Holocaust is the most popular interpretation for Shostakovich's use of themes inspired by Jewish folk music, but other interpretations include a tribute to Fleischman (who was Jewish), or a nod to Sollertinsky's birthplace of Vitebsk, which had a substantial Jewish population until the Vitebsk Ghetto Massacre in 1941 by the Nazis. (While I haven't read anything confirming that Sollertinsky was ethnically Jewish, the painter Marc Chagall and pianist Maria Yudina, both carrying associations with Vitebsk, were.) Whether the grief expressed here was personal or referencing the larger global situation, the quotation of the fourth movement's ostinato followed by the final E major chords suggest a peaceful resolution after a long movement of aggressive tumult and grotesque rage.

Shostakovich would continue to grieve and remember Sollertinsky, but the ending of this piece- composed over the course of about nine months- perhaps implied closure and healing. In the following years, the war would end, Shostakovich would form new connections (such as a lasting friendship with the composer Mieczyslaw Weinberg), and, as he had done through tragedy before, would continue to write music. Sollertinsky was gone, but left a mark on Shostakovich's life and work, his memory carried in every musical joke and Mahlerian quotation that found its way onto the page.

(Shostakovich at Sollertinsky's grave, 1961, Novosibirsk.)

(By the way, check the tags. ;) )

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#tumblr's guide to shostakovich#classical music#music history#soviet history#ivan sollertinsky#russian history#classical music history#composer#music#history#also fun fact sollertinsky and shostakovich almost wrote a don quixote ballet together but that didn't work out bc shost got denounced#they had an inside joke about a fake composer named persianinov. they invented goncharov you guys#there's one letter from shost to sollertinsky about the time a ballet worker tricked another worker into eating goat shit#sollertinsky would apparently come over to shost's house and sing mahler symphonies in a 'high squeaky voice'#like from memory#they'd write riddles to each other in letters#i love them so much#they are everything to me#apparently they'd also run over to each others' houses to deliver letters if they couldn't see each other#in leningrad ofc#sollertinsky got REALLY PISSED once bc someone suggested changing a bit of shost's music in lady macbeth it was really funny#shost once said sollertinsky had a 'magical influence on the female sex' and like . look at him#he's not wrong#oh btw it's 3 am and I have work tomorrow#oh one last fact they loved to go on roller coasters together (in russia they call them 'american mountains') but#the one they liked burned down lol

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich: Part 1

Hello, and welcome to a multi-part series of posts I'll be uploading weekly called Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich, an informative and casual approach to the life and works of Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (1906-1975), one of the most well-known Russian composers of the Soviet era. I have been researching Shostakovich for the past three years and am very excited to share what I've learned with you all!

Part One- Overview: Who was Shostakovich?

(Yes, he looked like that. Luckily for Tumblr, this series will include plenty of photographs.)

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1906, and died in Moscow in 1975. He was a skilled concert pianist and composer of a variety of works, including 15 symphonies and string quartets, three ballets, operatic and vocal pieces, film music, concerti, and other chamber and orchestral works. In the west, he's most well-known for not just his music, but his complicated relationship with the Soviet authorities since 1936, when his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was denounced in the state newspaper Pravda on January 28th of that year. Since his denunciation, Shostakovich attempted to compose within the style of Socialist Realism, or an artistic style that intended to display Soviet political and cultural values and be easily accessible, but many of his works from 1936 to 1953 (the year Stalin died) are often interpreted by scholars to contain "hidden meanings" and messages of dissent. This has made Shostakovich both a popular and a controversial composer among western music scholars, who often debate interpretations of his pieces, as well as details on Shostakovich's personal life and political values.

Shostakovich is a difficult figure to research, not only due to the multiple interpretations that exist of his pieces, but also the differing accounts of the man himself. The most infamous example of this is the 1979 book Testimony, written by Solomon Volkov and claimed to be Shostakovich's own memoirs, as transcribed by Volkov himself. Testimony portrays a bitter, angry Shostakovich, vocal in his dissent towards both the government and the Soviet musical establishment. While some scholars and even some who knew Shostakovich side with Testimony as legitimate, others have argued that Testimony is likely partially, if not completely, fabricated. (It is for this reason that I will not be relying on Testimony as a source in this series, but rather primary accounts from Shostakovich's contemporaries and his own correspondence. Secondary sources will be cited, but primary sources will be referred to whenever possible.)

Speaking of primary sources, they also tend to muddle Shostakovich research even further. Many people knew Shostakovich throughout his life, and many different recollections of him, some of them conflicting, will appear from his friends, family, colleagues, and adversaries. For instance, Isaak Glikman and Lev Lebedinsky were both, at one point, friends of Shostakovich. However, when Shostakovich joined the Communist Party of the USSR in 1960, while Glikman and Lebedinsky agree he did not join the Party willingly, their accounts differ in that Glikman claims Shostakovich reluctantly joined the Party to ensure his own stability, Lebedinsky claims he was tricked into signing the official documents while inebriated. There are some sources, like Galina Ustvolskaya, whose recollections of Shostakovich changed with her opinion on him- as their relationship deteriorated, Ustvolskaya recounts Shostakovich increasingly negatively. And there are some accounts based simply on misremembrance, hearsay, rumours, and speculation. Oftentimes, I find myself having to read accounts from multiple primary sources and deciding which ones are the most consistent, without the satisfaction of finding out concrete truth.

Finally, there's Shostakovich himself. While many of his letters to various correspondents survive and have been published in Russian and other languages, Shostakovich's writing is notorious for its use of sarcasm, tautology, literary allusions, and Russian idioms, making it all the more difficult to interpret in translation or even without Russian cultural background. Shostakovich also had a habit of destroying letters after reading them, so of course, many of the letters we do have are missing crucial context. And of course, he constructed a very official public persona (particularly after 1948) that was remarkably different than his private self, adding to the complexity of discerning his own views and opinions.

However, to me, the thing that interests me the most about Shostakovich was his resilience. He lived through a number of catastrophic historical events, personal attacks, and hardships, all of which are documented in his works, many of which provide both insight into the Soviet historical zeitgeist of the time and Shostakovich's personal situation. And yet, despite everything, he kept composing up until his death, with his last work, the Viola Sonata, the only one whose premiere he did not attend. Much has been said about the "depressing" quality of Shostakovich's works, particularly during his Late Period (1954-75), but a wide scope of other emotions exist within his oeuvre, from his wicked sense of grotesque humour to his deep compassion for life and humanity. Despite popular characterizations, Shostakovich was a complex man whose work only proves to be just as complex the more we study it.

-

Thank you for reading! The next post will discuss Shostakovich's family history and its deep background in revolution.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#classical music#music history#history#soviet history#soviet music history#soviet classical music#russian history#tumblr's guide to shostakovich

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich- Part 4: Establishing a Star

It's been a while since my last Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich; I'm so sorry! I've got a ton of projects I'm working on and I just haven't had time for this one. But now that I'm back, it's time to cover the late 20s and early 30s, which is quite a bit of ground.

So, after the composition of his First Symphony in 1925, Shostakovich was quickly becoming noticed, both within the USSR and internationally. 1927 proved to be a consequential year for him, as he began performing as a concert pianist and participated in the First International Chopin Competition in Warsaw, although he did not place among the winners. Nonetheless, he regarded the competition as a success in a letter to his mother, from February 1, 1927. The pianist Nathan Perelman characterized Shostakovich's pianistic style as such:

Shostakovich emphasized the linear aspect of music and was very

precise in all the details of performance. He used little rubato in his playing, and it lacked extreme dynamic contrasts. It was an ‘anti-sentimental’ approach to playing which showed incredible clarity of thought. You could say that his playing was very modern; at the time we accepted it and took it to our hearts. But it made less impression in Warsaw, where [Lev] Oborin’s more decorative, charming and ‘worldly’ approach, albeit somewhat militaristic,

was the order of the day. However, Shostakovich seemed to foresee that, by the end of the twentieth century, his style of playing would predominate, and in this his pianism was truly contemporary.

(Participants and jury of the First International Chopin Competition, 1927. Shostakovich can be seen third from the left in the second row.)

1927 also saw an event that would once again change the course of Shostakovich's life- in addition to the composition of his Second Symphony (subtitled "To October"), we see in correspondence his first mentions of a foray into operatic composition. While Shostakovich had set words to music before (for instance, "To October" includes an ideological text by Aleksandr Bezyemensky), he decided to choose a work familiar to him as the subject of his first opera, The Nose by Nikolai Gogol, which he mentions in a letter to his friend, the critic Boleslav Yavorsky, on June 19, 1927. (Yavorsky was one of Shostakovich's primary correspondents until August of that year, when he met the polymath and scholar Ivan Sollertinsky, who was to become his closest friend. For more on Sollertinsky, I have a whole post on him here.)

Shostakovich was a lifelong Gogol enthusiast and even had many of his stories memorized by heart, which he was often fond of quoting, both in correspondence and conversation, so it should come as no surprise that he decided to adapt a Gogol story as his first opera, even writing the libretto himself and adapting long passages of the original short story into it (as well as references to other Gogol stories as well!). However, to those unacquainted with Shostakovich, The Nose seems like an unlikely choice for an operatic adaptation, especially considering the great canon of Russian-language literature that has historically been used for operatic adaptations, such as Tchaikovsky's Evgeny Onegin and Pikovaya Dama (or The Queen of Spades), both adapted from Pushkin. The Nose, on the surface, is a bizarre and comedic story, in which the main character, Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov, wakes up to find his nose removed from his face. The Nose is later found walking around Saint Petersburg, where it has gained sentience, talks, and even receives a promotion, much to the status-obsessed Kovalyov's chagrin. Kovalyov is unsuccessful in getting people to believe that his nose is now sentient, shenanigans ensue, and by the end, he wakes up once again to find his nose reattached, as Gogol's narrator remarks on the absurdity and ridiculousness of the story.

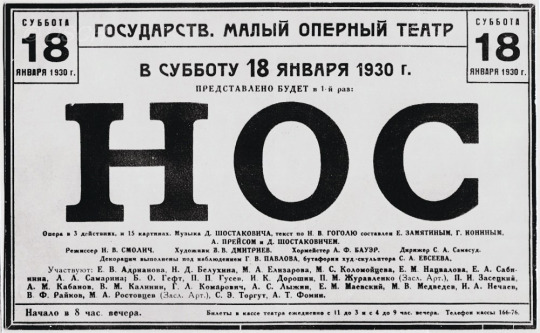

It seems like impossible subject matter for an opera, and yet, Shostakovich makes it work. With his penchant for sarcasm and the grotesque, as well as his use of inverting conventions of comedic and tragic music with the effect of making tragic situations seem ridiculous and ridiculous situations seem tragic, Shostakovich enriches Gogol's original Nose (assisted by the author's trademark skaz literary style) in his adaptation, while keeping it distinctly Gogolian. The Nose would be completed in 1928, and premiered in 1930, although it was not a success among the general public at the time, largely due to the avant-garde music and absurdist themes. It would not be performed in the USSR again until 1972.

(A poster for the premiere of The Nose at the Maly Opera Theatre, Saturday January 18th, 1930.)

In 1928, Shostakovich would make a strong connection with the theatre director and playwright Vsevolod Meyerhold, and wrote music for his theatre in Moscow. Shostakovich's stay with Meyerhold, as evidenced from letters to Sollertinsky, was less than ideal- he found Meyerhold and his wife, the actress Zinaida Raikh, to be at times obnoxious in the way they fawned over each other and their two children, and their nanny made unwanted advances on him- but found a career writing music for stage plays, most notably in collaboration with the poet and playwright Vladimir Mayakovsky, whose play The Bedbug he composed accompanying music for.

Shostakovich accepted a position at the theatre collective TRAM (Russian: Театр Рабочей Молодёжи, or Worker's Youth Theatre) in 1929, where he composed music for a number of ideological plays. Scholar Elizabeth Wilson notes that while Shostakovich enjoyed writing music for some of the TRAM plays, he also joined TRAM in an effort to shield himself from criticism from the RAPM (Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians), a more conservative musical branch that was, at the time, amassing power. The RAPM was in opposition at the time to the ACM (Association For Contemporary Music), and encouraged many elements that would later be incorporated into the Socialist Realism style that would take effect in the mid-30s. However, neither organization was around for long; the ACM was dissolved in 1931, while the RAPM was dissolved in 1932. While we know that Shostakovich was growing increasingly aware of the gradual restrictions being placed on music, in the coming decades, the intersection between Soviet politics and music would become unavoidable, and the next opera Shostakovich would compose in just a few years' meant he would find himself straight in the crossroads.

Thank you for reading! In the next entries, we’ll get further into the 30s, where there’s a lot to cover!

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#tumblr's guide to shostakovich#history#soviet history#soviet music history#music history#classical music#composer#classical music history#classical composer#opera

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich: part 3- Artistic Beginnings, Ideological Formation, and the Conservatory Years

Hello and welcome back to Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich, the weekly series where I discuss the life of Soviet composer Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich! In this installment, I'll be talking about events throughout Shostakovich's adolescence, including his family hardships, his time at the conservatory, and his First Symphony. The sources I'll be drawing from are Pauline Fairclough's Critical Lives: Dmitri Shostakovich, Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Laurel Fay's Shostakovich: A Life, and various articles of correspondence posted on the DSCH Publishers website, where I will also be sourcing much of my photographs.

At the age of thirteen, in 1919, Shostakovich left a general education at the School of Labour no. 108 to study music at the Petrograd Conservatory, directed by Aleksandr Glazunov, himself a famous composer in his own right (and friend of the late Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky). Shostakovich studied composition under composer Maximillian Osseyevich Steinberg, and wrote his first numbered works, such as the Scherzo in F# Minor (Op. 1) and the Three Fantastic Dances (Op. 5). Shostakovich was an eager student who took inspiration from many contemporary composers of the time; while his early student works show traces of Tchaikovsky and even some Debussy, his later inspirations would include Bartok, Stravinsky, Hindemith, and Schoenberg, although he was also frequently influenced by Mussorgsky. His musical talents were noticed by his classmates and teachers, as this anecdote from Valerian Bogdanov-Berezovsky, his friend and classmate states:

"Shostakovich undoubtedly outstripped everyone in this art [music], as well as in aural dictation. One could already compare his hearing in its refinement and precision to a perfect acoustical mechanism (which he later was to develop still further), and his musical memory created the impression of an apparatus which made a photographic record of everything he heard."

Shostakovich (top left) with Steinberg's (center) composition class, 1920s.

Hardship would rock the Shostakovich family when, in 1922, Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer's father and main breadwinner of the family, died of pneumonia. Shostakovich would write his Suite for Two Pianos (Op. 6) in his father's memory, the first of many pieces he would write that would bear dedications to deceased loved ones. It was premiered by Shostakovich and his sister, Mariya.

After the death of her husband, Sofiya Vasiliyevna worked a variety of low-paying jobs, while her children also sought work to help support the family, with Mariya teaching piano lessons and Mitya finding work as a cinema pianist for silent film theaters. Shostakovich worked at three cinemas during this period- the Bright Reel, Splended Palace, and Piccadilly Theater. He resented cinema work; the pay was low, the managers dishonest, and his creative abilities stifled by both the insipid music he was required to play and the work taking time from his studies. (Reportedly, he was once thought to be drunk while attempting to imitate bird noises on the piano to accompany a film called Water Birds of Sweden. Amusingly, scholar Laurel Fay notes that "far from being stung by the criticism, Shostakovich expressed his pride in having distracted their attention from the film.") However, as much as Shostakovich hated cinema work, it provided him with stylistic inspiration, as shown in his Piano Trio no. 1 (Op. 8), as well as the opera and film scores he would write later on in his career.

While he worked tirelessly to support himself and his family, after the death of his father, a toll was being taken on Shostakovich's physical health. His godmother, Klavdia Lukashevich, noted that Shostakovich was given a "talented" ration" by the conservatory consisting of of "two spoons of sugar and half a pound of pork every fortnight," although this was not enough to sustain him. While Glazunov, reserving high hopes for his student, provided him with a stipend, a group of students had attempted to have it suspended. Likely due to malnutrition, in 1923, Shostakovich fell ill with tuberculosis and was sent to a sanatorium in the Crimea to recover. (He also met his first girlfriend and the dedicatee of Trio no. 1, Tatiana Glivenko, there, but the hot mess that relationship turned out to be deserves its own post.)

Maximillian Steinberg, Shostakovich's composition teacher.

In the wider political and social sphere, Shostakovich would gain both musical and ideological influences due to the advent of Lenin's New Economic Policy (NEP), a response to the failed economic policies of the Russian Civil War (1917-1923). The NEP, introduced in 1921 and later dissolved by Stalin in 1928, included a small capitalist sector to the economy, which was intended to be gradually phased out in a less aggressive approach to communism. While this period was far from utopian- censorship, corrupt business practices, and political unrest still abounded- the economic relief that the NEP provided led to a period of social progressivism that would later be reversed by the 1930s. During the NEP era, a wave of social reforms took place- in the sphere of sexuality and relationships, abortion and homosexuality were decriminalized, divorce was made easier (although this led to an increase in broken families, as men often readily divorced their wives after impregnating them), and "free love" movements took place. Meanwhile, in terms of social issues, the "Indigenization" movement sought to uplift the cultures of ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union (although it should be said this movement put Jews in a bizarre position; the banning of religion meant that while synagogues were desecrated and the Hebrew language banned, other aspects of Soviet Jewish culture, like Klezmer music, were promoted), and feminist ideals largely took hold, most notably spread by activists like Aleksandra Kollontai. And in the arts, the NEP resulted in a variety of works that blended avant-garde experimentation (also popular in the west at the time) with newly-forming Soviet ideals, such as Mayakovsky's play The Bedbug (which Shostakovich provided music for), Vsevolod Meyerhold's theatrical productions, and Aleksandr Mosolov's futurist musical compositions, most notably Iron Foundry. As Shostakovich worked with many artists of the NEP era and artistically "came of age" around this time, both social and artistic ideas would find a permanent place in his life and work, most notably the feminist themes of Lady Macbeth, his liberal attitudes towards sex and marriage (he himself would later enter an open marriage), and the avant-garde and oftentimes grotesque techniques he would employ in his music. A letter to his mother from his stay in the Crimea in 1923 highlights many of these views:

If, for instance, a wife stops loving her husband and gives herself to another man she has fallen in love with and in spite of social prejudice they start living together, there is nothing wrong about that. On the contrary, it’s even good that Love should be really free. Vows made in front of the altar [...] are the most terrible part of religion. Love cannot last for a long time. The best thing one could imagine is the complete abolition of marriage, namely of all the chains and duties that accompany love. This of course is a Utopia. If there is no marriage, there will be no family. That of course, would be very bad. One thing can be said for certain though - love is not free. Mamma dear, I must warn you that if I do fall in love one day I may well not try to tie myself down through marriage. Yet if I do marry and my wife falls in love with someone else, I shall not say pure word. If she wants a divorce, I shall give it to her and take the blame on myself. [...] Yet at the same time, there is the noble vocation of parenthood. When you start thinking about all this, your head is ready to explode. In any case, Love should be free!

In 1925, Shostakovich completed his First Symphony at the age of nineteen, as his graduation piece. It was premiered by his teacher, the conductor Nikolai Malko, who Shostakovich regarded as a "rather ungifted person" (his early letters show no small amount of arrogance!), but Malko nonetheless found the symphony impressive. It was premiered on May 12th, 1926, and received a largely positive reception that would cement Shostakovich as a promising composer, receiving praise from the likes of not only Soviet musicians, but prominent western ones such as Bruno Walter. While many accounts detail nothing but praise on the event of the symphony's premiere, Shostakovich held a much different opinion, detailing in lengthy letters to both his mother and his friend, Boleslav Yavorsky, the poor acoustics of the venue, blunders on behalf of the musicians, and even a nearby dog drowning out the music with a prolonged barking session. Despite how mortified he was at what he perceived to be the premiere's failure, Shostakovich would celebrate its anniversary for the rest of his life, later considering it his "second birth."

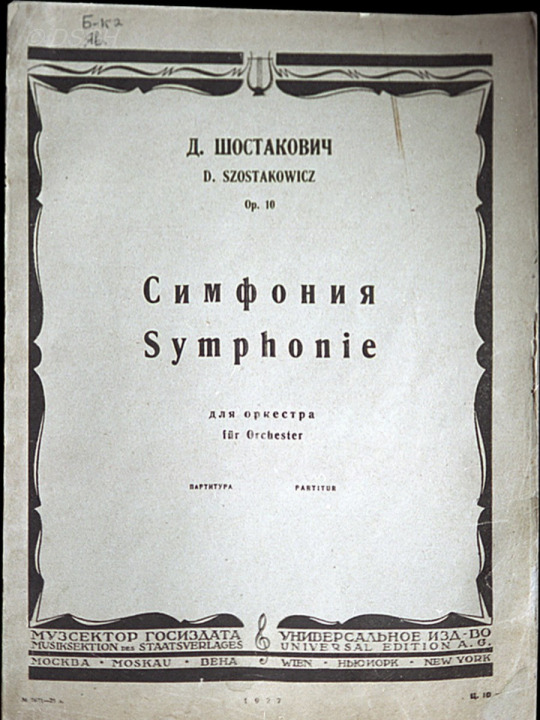

A first-edition score of Shostakovich's First Symphony. 1927.

Thank you for reading! In the next entries, I'll cover some events in Shostakovich's personal life and his operas The Nose and Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District- as well as the consequences that would follow.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#tumblr's guide to shostakovich#composer#classical music#music history#russian history#soviet history#music#classical music history

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr’s Guide to Shostakovich: An Uncomfortable Truth

Hello, everyone.

You may be wondering why I'm writing another essay on the subject of Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich today, right after another one I just finished recently. However, important information has come to light, information that cannot be ignored. As a researcher, it would be irresponsible and dishonest of me to hide this information from the public, especially on a subject I have devoted so much time and effort into researching. It pains me to reveal this information, but in the field of history, sometimes uncomfortable truths must be brought to light in order to further our understanding of the past. I have known this information for a very long time, and, I'm sorry to say, have withheld it from the public, as not to soil and degrade the image of such a beloved composer (although historically, plenty of people have soiled and degraded his image, so if that many people are doing it, it sort of seems like it might be fun), but I am done hiding this information and must share it with my devoted readers, lest they continue to consume lies, falsehoods, and half truths. I will waste no time in divulging this information to you all. To those of you whom, like I, love Shostakovich's music, I hope this revelation will not alter your view of those brilliant works which you hold in such high esteem.

The truth is this.

After three years of researching and analyzing sources, contacting experts, and learning as much as I could, I have come to this unavoidable conclusion-

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was a Tumblr Sexyman.

I know. It's very hard to process- I myself spent a very long time turning this devastating conclusion over and again in my mind, trying to think of another possible explanation. But the truth is, he fits all of the criteria and more to be considered one, and I can no longer ignore the truth and pretend it doesn't exist.

First, his physical appearance. Most Tumblr Sexymen, from The Lorax's Once-Ler to Hazbin Hotel's Alastor, wear dapper formalwear, often with coattails, a bow tie, and a button-up shirt. This is often the case as well with our dear Shostakovich. There are plenty of photographs out there of him in formalwear, playing the piano at concerts or conversing with fellow artists. His intellectual pursuits add to this qualification of seeming refined and classy as well- Shostakovich was an avid reader, and often quoted his favourite authors in conversation. His friend Isaak Glikman, perhaps the first person to observe Shostakovich's Tumblr Sexyman status, even notes this about his manner of dress in his younger years:

Some accounts portray the young Shostakovich as a puny, sickly weakling. This was far from the case. He was well-proportioned, slim, supple and strong; he wore clothes well, and in tails or a dinner jacket cut a most attractive figure.

Already, this reads like a fanfiction about any Tumblr Sexyman. In addition to the suit, Shostakovich was very pale and also wore his trademark round glasses, giving him a distinguished, intellectual appearance, and Glikman also cares to note his friend's "splendid head of light-brown hair, usually neatly brushed but sometimes 'poetically' dishevelled with a mischievous, unruly lock falling over his forehead." Indeed, Tumblr Sexymen often have playfully messy hair and sometimes distinctive eyewear, and Shostakovich is no exception.

But clothes do not a (Sexy)man make. A Tumblr Sexyman is not complete without a bit of darkness- sometimes an evil side belies their composed exterior, or, like Sans from Undertale, their goodness is tragically juxtaposed with some sort of great trauma they experienced in their backstory. Shostakovich seems to fit the second category, and as a result, was very withdrawn and mysterious. From a young age and well into his older years, he faced the deaths of loved ones, public humiliation, the horrors of war, constant thoughts of his own demise, numerous health issues, betrayals from friends, and of course, the ever-present demands of the Soviet regime. With most Tumblr Sexymen, a tragic history makes them intriguing to fans, and given the decades of musicological research and debate surrounding Shostakovich's own history and political ties, it seems his own backstory has proved to be compelling as well.

But a Tumblr Sexyman has ways of dealing with his troubles, and wouldn't you know it, Shostakovich fits this criteria as well. Tumblr Sexymen often have a sense of humour, joking and making sarcastic jabs to hide their pain and anxieties. They may give witty one-liners, tell puns, or even perform comedic or upbeat songs. And with Shostakovich, we see multiple accounts of his sarcastic humour, especially in his letters to Sollertinsky, a penchant for wordplay, even satirical musical pieces about his life experiences, like the "Antiformalist Rayok" and "Preface to a Complete Collection of my Works." He may not be singing about an evil plan like other Sexymen may, but the fact that these pieces exist certainly make it clear that he used music, comedy, sarcasm, and wordplay to cope with his anxiety or depression.

His chaotic unpredictability and political greyness clearly factor as well. While Shostakovich had a very strong moral center, his unique historical position in both expressing himself as an individual and an artist and being a dutiful servant of the regime meant he had a rebellious streak, which would surface when least expected. The composition of the joke-filled Ninth Symphony at the end of the war, for example, is seen by many as an act of rebellion, especially when compared to the earlier Seventh, and even in pieces like the Fifth Symphony, called a "response to just criticism" after the harrowing denunciations of 1936, subtle acts of resistance are interpreted in this work as well. Indeed, Shostakovich's political alliances are hard to place, and the fact that he lived by his own moral code first and foremost gives him an almost chaotic edge that would fit right in with any Tumblr Sexyman. Every time it seemed as if he had finally conformed to the expectations of the Party, Shostakovich would once again stir controversy with an innovative or subversive work, displaying a disregard for the strict rules of socialist realism underneath his quiet and unassuming exterior.

So yes, Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was indeed a Tumblr Sexyman. He fits all the criteria, from his appearance, to his personality, to his backstory. I know this information may be hard to process, but it's the truth. But perhaps I'm overstating things. After all, as one of the greatest Tumblr Sexymen of all time once said, "how bad could it possibly be"?

(Happy April Fool’s Day! If this looks familiar, I posted it to my Reddit a few years back.)

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#tumblr’s guide to shostakovich#classical music#music history#soviet history#composer#russian history#music

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

A note on Tumblr’s Guide to Shostakovich- Russian naming systems, spelling variations, and transliteration

So, in my last post for Tumblr’s Guide to Shostakovich, I talked about Shostakovich’s family background and referred to them in respect to Russian naming systems. For people who aren’t familiar with them, they can get a bit confusing, especially since one person can be referred to in multiple ways, depending on familiarity. Because I was talking about Shostakovich’s family and multiple people who shared the last name “Shostakovich,” I used this system when appropriate to avoid confusion. In cited quotes, you may also see multiple variants of one name, so I thought I’d briefly explain this system for those who aren’t familiar to avoid possible further confusion. I also wanted to explain this system because it denotes formality/intimacy depending on who’s addressing who, which is important to understand when dealing with primary sources.

While I typically refer to Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich in this series as “Shostakovich,” as his father was also “Dmitri Shostakovich,” I tend to refer to him by first name and patronymic to distinguish them from one another. The patronymic is a middle name composed of one’s father’s first name and a suffix (-ovich/evich for men; ovna/evna for women), and addressing someone by first name and patronymic denotes formality. In this series, outside of cited quotes, I will refer to most people by just last name, but usually use first name and patronymic for adults who share a last name. So, Shostakovich’s father will be “Dmitri Boleslavovich,” Shostakovich’s first wife will be “Nina Vasiliyevna,” etc.

Diminutive names also vary based on levels of intimacy. A standard diminutive may be used by relatives and close friends, but more complex diminutives signify greater levels of affection and are typically used either by lovers or from a parent to a child. When referring to Shostakovich in childhood, I may refer to him as “Mitya,” one standard diminutive for “Dmitri,” and the one he typically went by. (However, Vsevolod Meyerhold referred to him as “Dima,” another standard diminutive of the same name.) Very rarely, I’ve read documents where he’s referred to as “Mitenka” or even “Mityushka,” and typically, it’s by his mother. (He may have also had lovers who referred to him in this way, although letters from any are rare, as Shostakovich typically did not keep correspondence.)

Lastly, I want to talk about spelling and transliteration. As there are different ways to transliterate Cyrillic words into Latin, you may see different spellings of the same word across sources. For example, while I typically spell “Dmitri Shostakovich,” you may also see “Dmitry Shostakovitch,” etc. Last names that end in -ов may be transliterated as “-ov” or “off,” although I typically tend to stick with “-ov.” So, “Рахманинов” may be transliterated as “Rakhmaninov,” “Rachmaninov,” or, as the man himself spelled it, “Rachmaninoff,” but I tend to use “Rachmaninov.”

As for transliterations of Ukrainian words, especially in light of the war, I will use transliterations that follow Ukrainian pronunciation instead of Russian pronunciation when applicable- “Kyiv” instead of “Kiev,” etc. The only time I will use different spellings is “Babyn Yar”/“Babi Yar,” and to refer to two different concepts. Both refer to a ravine in Ukraine that was the site of a massacre in 1941 by the Nazis against primarily Ukrainian Jewish civilians; in 1962, Shostakovich wrote his 13th symphony and subtitled it “Babi Yar,” as the first movement was a setting of a Evtushenko poem about the massacre. Because the ravine is in Ukraine, I will refer to the location as “Babyn Yar” when discussing its history, and the symphony/poem as “Babi Yar,” as it was written in the Russian language and titled using the Russian variant of the name.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#tumblr’s guide to shostakovich#classical music#music history#soviet history#history

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

yes I know I should do another tumblr's guide to shostakovich but also I'm lazy so . here's the boys again

yes I refer to two guys who died in the previous century as "the boys"

#ivan sollertinsky#dmitri shostakovich#shostakovich#history#soviet history#composer#music history#classical music#classical music history

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

so I’m Really behind on mermay and tumblr’s guide to shostakovich and I haven’t updated my ask blog in a while :( went on a trip and now I’m taking care of my bird so all those things will have to wait probably

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

foaming at the mouth wanting to talk about symphony 13 on tumblr’s guide to shostakovich but that’s 1962 and we’re still in the late 20s rn

rayok too but that requires so much fucking context and it’s better to explain all that first lol

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

guys I promise I’ll do another “tumblr’s guide to shostakovich” soon I’m just lazy

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi I really seriously appreciate your tumblrs guide to shostakovich my guy is so underrated 💔 and to see someone make full posts about his life is so :) for me thank you

Thank you so so much! It makes me very happy to see they’re being appreciated. Shostakovich has meant a lot to me over the years I’ve been researching him, and I’m so happy to see people enjoying the series.

#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#classical music#music#music history#russian history#soviet history#composer#classical music history

6 notes

·

View notes