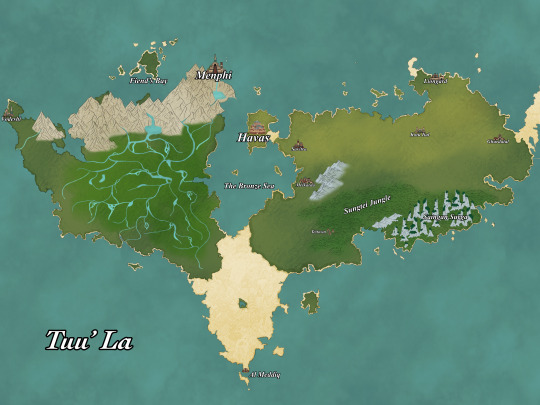

#tuula map

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Inkarnate can kiss my ass I am too cheap and too autistic to pay $14 for the good stuff when I can chug three cans of pepsi and possess myself with the soul of a 14th century cartographer

Anyway, this is my official submission to the fanmade region maps. I spent like all of last semester worldbuilding the hell out of Tuu'la and fingers cross I'll finally get around to posting about them more now that I'm done w my freshman year of college. Note that I will probably become dissatisfied with this in a week and update it another 6-7 times like the romeave tree

#mcd#minecraft diaries#aphmau mcd#minecraft diaries headcanons#aphblr#aphmau#mcd tuula#mcd art#minecraft diaries fanart#tuula map#stelli's lore#kawaii chan#michi mcd

72 notes

·

View notes

Note

"You have a reliable reputation. I would like you to bodyguard William here on a journey." Nillan gestured at a skeleton, which awkwardly raised a palm in greeting. "He was conscripted by the invaders, but his service days have ended. He would like to reach a port that can take him to Bilgewater, so he can start a new life there. How much would that cost?"

The woman had been sitting at the bar as the other had started to make the proposal, somewhat intoxicated before turning towards them...and shrieking. She had not seen the woman first, but the skeleton, alarming the woman so that that her pendant began to glow.

'I-f-f-forgive me ma'am! Y-y-you're aware that...there's...'

Her words faded as she slowly started to process what was in front of her. The woman was clearly used to the undead, not even batting an eye as the skeleton ... waved? She slapped both of her cheeks with her hands, trying to sober up enough to have a decent conversation...well...as well as she could considering the strange situation.

'Bilgewater... right...right!...' Her hand reached for the bag beside her, pulling out a journal containing stacks of papers, mostly worn maps that the mercenary used. It took a moment to locate one that included the pirate isles. Her eyebrows furrowed as her fingers traced potential routes, her free hand ruffling her hair.

'Considering we're here... for him to get out of here we'd need to head to Nanthee. Granted, most routes head to the Twin cities...but there are boats to Bilgewater if I remember correctly... p-providing the right coin is paid! The...' She lifted her head for a moment, glancing at the skeleton before continuing. '...Gentleman will need enough coin for that, and there's no sign of a Harrowing, so he should in theory be fine from there.'

She paused, shifting maps that showed more local terrain. Once again, her finger pointed to the locations, tracing a potential path.

'Currently in Tuula, so we'd need to go up the mountain pass initially, but downhill from there... hmmm...I reckon that would take... three days? Four if the weather isn't in our favour...'

She held her chin between her fingers, looking over at the woman.

'I'd need enough for rations and supplies... I doubt they would let me into a tavern with your friend there.... n-no offence! That said... I'd call it twenty gold for the endevour, but your friend will need...hmmm....I'd say at least fifty if we are to convince a captain to go to Bilgewater, yet alone take him safely....how does that sound?'

#nillan#...william?#//ALLO ALLO!#Sorry for the wait!#WALL OF TEXT BE UPON YE#I'M SO SORRY#the storm chaser ~

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fire Spreads to New Lands

Tepponilamek has 6 power remaining this turn. The Qurri of the Dominion of the Burnt explore eastwards, landing on Haebrach and making contact with the Tarbra. The initial exchange between the two is peaceful andany of the Tarbra are receptive to the message of the Burning Path and convert to the new faith. The town of Puqumiki (-3) is founded to serve as a trading port linking the two peoples.

The ink had not long dried on the peace treaty between Qattangu and the Dominion of the Burnt when the first Burnt looked to spread their faith beyond their borders. In the decades since, many of the faithful have travelled north to Nulat or west in Incarien to spread the faith; in most places, they have been unsuccessful. The Likani, concerned with their holy mission to finish Tepponilamek’s work in providing names to all things, pay them little attention, while the Messonir of the Ajuna have their own millennia-old faiths which have little space for seeking enlightenment in the face of Laneth.

In Incarien, not only are there many ancient religions, including some whose focus on the material reality of death offends the Burnt, but the threat posed by Kalkayer and its armies has inspired a wave of millenarian further among the humans of the region; most believe that the Times of Ending are coming soon, and in the face of that threat seeking peaceful enlightenment seemed foolish.

The contact with other peoples did benefit the Burnt in other ways. Not only did they establish strong trading links with the other peoples of the world, but they came to understand the small place of the Qurri within the larger history of the world, and the vast knowledge that other folks had amassed. Tilmeqa, a young Burnt missionary and scholar of languages who was the first Qurri to visit the House of All Things in Tsallosis, collapsed and wept at the sight, having realised there was far more to learn in the world than they ever could know.

Among the knowledge that passed to the Dominion was that of geography, including maps of the many lands of the world. This was of great interest to the Qurri, who were eager for other warm, wet climates where the Huk could prosper. Alas, they soon learned that such climates existed in a narrow band around the equator; west of the Isle of Velarie the only jungles were those between Tuula and Incarien, well settled by humans, and those of the Occident, which were already densely populated.

However, what lay to the east of the Haebran Isles where the Qurri dwelt – none could say. Sailors from Lekesh and Rasira rarely ventured into the Misted Isles, for good reason, as few ever returned.

The Burnt were not easily dissuaded, and before long a number of missions journeyed eastward from the Dominion’s shores to see what lands lay undiscovered. First amongst them were the siblings Rezikak and Terviqa, young sailors whose teacher-parent, Ilwarra, had fought in the revolt against the House of Transformation and had instilled in the pair both excellent navigational skills and a deep faith in the Burning Path.

Rezikak and Terviqa were the first Qurri to make landfall in Haebrach, and there they found vast swampy lowlands, perfect for the Huk to grow and breed to bring forth young Qurri. As they journeyed further along the coasts of this vast new land, they also found the Tarbra.

At first, the two kindreds did not know what to make of the other. The Qurri were disconcerted by the size and strange shape of the Tarbra, having expected any new kindreds they found to have a shape more like that of the humans, the Messonir, the Atai or the Hewn. The Tarbra, meanwhile, were truly surprised at the existence of the Qurri – though they had encountered Ohmlings and Eppethikuja, they believed that they were the only ‘civilised’ folk in all the world.

Despite this, the two peoples managed to make peaceable contact, and Rezikak and Terviqa were swift to learn the language of the gentle Tarbra. Their conversations with their new friends only made clear the depth of the cultural divide; the Tarbra’s nomadic lifestyle was strange to the Qurri, whose communities were often rooted in place by the presence of the Huk. Meanwhile, the entire existence of the Huk, the lack of family lineage amongst the Qurri and their polyamorous social structures were baffling to the Tarbra – though thankfully so much so that no real dislike arose, for how could they take offense at the practices of beings so completely different to them?

Soon, however, Rezikak and Terviqa began to speak of their religion, and it is hear that common ground began to be found. The Tarbra of the northwestermost part of Haebrach – and the two young Qurri were stunned to hear how vast the landmass they had discovered was – believed, as most Tarbra did, in reincarnation and cycle of souls from one life to the next. They were more unique among Tarbra in their belief that this cycle was finite; eventually, the reincarnation of souls would end with the death of the Dying God.

This belief was not so different from the Burning Path, which held that souls were slowly drawn to Laneth over many cycles of reincarnation. The Burning Path, however, offered a way out; to achieve enlightenment was to break the cycle of reincarnation and escape the entropic doom of mortality.

The words of the prophet Zhuokeunqi, carried by Rezikak and Terviqa, spread like wildfire amongst the Tarbra of the region. The two preachers travelled from community to community, learning about the nomadic way of life as they passed on the teachings. Many of the Tarbra of the region converted to the Burning Path itself; even more were curious, or adopted elements of its doctrine into their own beliefs.

With this contact both peaceful and productive, it was not long before more Qurri made the journey to Haebrach. A town was founded in a sheltered harbour to trade with the Tarbra of the region, and named Puqumiki; ships began to head back and forth from Ktem to Puqumiki, trade developed as the Tarbra exchanged hides of many kinds for all manner of manufactured goods the Qurri could provide, and numerous preachers journeyed from the Dominion of the Burnt to preach to the Tarbra.

As word began to spread east and south of the strange foreign beings that had landed on Haebrach’s shores, bearing with them new technologies and a strange new faith, it reached the Flamekeepers of Lach Heral, whose reaction to the Qurri and their words was decidedly less welcome.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Melodier: Nordic Corporatist Pop and New Wave

Part IV. Youtube. Previously (I, II, III). Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, and Finnish pop between 1981 and 1987. Tracklisting below, notes after that.

Elisabeth, “En sømand som dig”

Doe Maar, “De bom”

Belaboris, “Kuolleet peilit”

Lustans Lakejer, “Diamanter”

Lillie-Ane, “Meg selv”

Arbeid Adelt!, “Lekker westers”

Geisha, “Kesä”

Det Neodepressionistiske Danseorkester, “Godt nok mørkt”

Cherry, “Vang me”

Tappi Tíkarrass, “Kríó”

Eva Dahlgren, “Guldgrävarsång”

Svart Klovn, “Knust knekt”

Het Goede Doel, “Net zo lief gefortuneerd”

tv-2, “Vil du danse med mig (nå- nå mix)”

Lolita Pop, “Regn av dagar”

Cirkus Modern, “Karianne”

Madou, “Witte nachten”

Tuula Amberla, “Lulu”

Grafík, “Þúsund sinnum segðu já”

Klein Orkest, “Over de muur”

Di Leva, “I morgon”

Melodier: nordic corporatist pop and new wave

So far in this survey, I’ve been looking at pop scenes in languages I may not entirely speak, but am at least comfortable with. Moving into northern Europe means I’ve left the Romance family behind, and am at the mercy of fan transcribers and Google Translate if I want to understand the lyrics to the songs I enjoy. Lyrics aren’t everything (I couldn’t tell you what some of my favorite songs in English are about) but they’re enough that I’ve at least tried to look up everything I’m presenting for you in this series.

This entry collects together a bunch of nation-states that aren’t necessarily related culturally or historically. Scandinavia only refers to three countries: Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Adding Finland and Iceland makes the “Nordic” countries; but adding in the Netherlands (and Dutch-speaking Belgium, or Flanders), as I have, isn’t anything as far as UN statistical calculations are concerned. They all fit together in my head, though, because they are all stable, prosperous, and socially liberal Western nations with Germanic linguistic roots (except Finland), NATO (except Sweden and Finland) and EU (except Norway) membership, and an extensive welfare state linked to strong unionized labor and government oversight of business: the “corporatist” social organization of my subtitle.

They are all also collectively central to white supremacists’ imagined European identity, and their liberal welfare policies are frequently cited (by racists) as unworkable in more heterogeneous societies. So i’m a little hesitant to be extremely fulsome in my praise here, lest anyone get the wrong idea. For the record, money, access, and individual creativity have far more to do with making great pop music than genetics.

Still, there is undoubtedly an enviable Northern European pop tradition. A lot of that can be traced to a single act: the Swedish ABBA, who borrowed liberally from US and UK pop forms to build a global pop empire based on careful production and universal sentiments. Thanks in part to their pioneering efforts, as well as Dutch acts like Shocking Blue and Golden Earring, a great deal of Northern European pop music was produced in English, with local languages often reserved for traditional folk, comedy records, sentimental ballads — or punk rock. There was particularly a gender-based split here: female Dutch, Danish, and Swedish pop stars were, like Frida and Agnetha, more likely to sing in a universal and generic English, while male rockers could afford to be poets and philosophers in the vernacular. (This is a generalization; but the phenomenon is by no means exclusive to northern Europe, or even across languages.) But regardless of language, there was a Nordic emphasis on slickness of production that means that this mix may, record for record, sound the most expensive of any in this summertime European excavation.

Which is another way of saying it’s the most pop. The low-density Scandinavian countries have few urban populist music traditions like Portuguese fado, Spanish flamenco, French musette, Greek rebetiko, or even Italian canzone napoletana: Protestant hymnody, fishing songs, and a rather austere nineteenth-century European concert repertoire are the most prominent native cultural influences. When American, and especially American Black, music made its midcentury European Invasion (far stronger and more lasting than any Invasion US pop ever suffered), it gave Northern European youth an emotional as well as a physical pop vocabulary. This, the second generation of European rock, made it perhaps more political and personal, but by no means less international.

Because pop is an international language, even when the lyrics are not. Although the subfocus of these mixes has been “new wave,” meaning the sometimes eccentric and often electronic music made under the twin influences of punk and disco, there was less of a noodly self-important rock tradition in these nations than in the English- (or Italian-) speaking world for a new wave to rebel against. Pop thrills remained consistent; only the tools changed.

“Melodier” is the Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian word for “melodies,” and it came to mind because the annual pre-Eurovision national pop contests in the Nordic countries are mostly named some variation of the Swedish Melodifestivalen.

The linguistic breakdowns in the mix, roughly following population counts, are as follows; six Dutch (of which two are Flemish), four Swedish, three each Danish, Norwegian and Finnish, and two Icelandic. Fans of twenty-first century Scandinavian pop may hear some material that presages later developments: a lot happened between ABBA and Robyn, and I’m excited to possibly introduce you to some of it.

1. Elisabeth En sømand som dig Genlyd | Aarhus, 1984

The coastal peninsula-and-archipelago nation of Denmark has been a seafaring one since the Vikings, etc. — but this song isn’t about those ancient sagas, but more recent colonial history, as the lover “Jakarta Danny” is presumably a merchant marine in the service of the Dutch East India Company. Elisabeth first became known to the Danish pop audience as the frontwoman of Voxpop, a Blondie-like pop group, and her first solo album in 1984 is a quiet classic of sultry mid-80s pop moves. This, the leadoff track, uses naval metaphors for sex: the title means “A Seaman Like You,” and the next line is “sailing in me.” The video makes it even more explicit, in more ways than one. She’s still active (her whole catalog is on Spotify), and often does children’s music now.

2. Doe Maar De bom Sky | Amsterdam, 1982

The two-tone wave in the UK had a corresponding wave in the Low Countries and Scandinavia: goofy white dudes are drawn to ska music, as Orange County can attest. Doe Maar (“go ahead,” with connotations of anger or sulkiness) were the Madness of Holland, with a string of skanking, socially observant hits. “De bom,” one of their biggest, means “The Bomb,” and is about the hideous irony of being told to go to school, get a job, and save for retirement, all under the threat of nuclear annihilation.

3. Belaboris Kuolleet peilit Femme Fatale | Helsinki, 1982

The Finnish girl group Belaboris (named for Lugosi and Karloff) was manufactured by producer Kimmo Miettinen, a Malcolm McLaren-esque figure who hired girls to sing and look pretty while a hired band played new wave music. “Kuolleet peilit” (Dead Mirror?) is a minimal-disco jam with a detached vocal by Vilma Vainikainen that looks forward to spacy twenty-first century house: in Finland, such synthpop was known as “futu,” short for futurist. When Belaboris had a second big hit in 1984, it was as an entirely different set of pretty girls.

4. Lustans Lakejer Diamanter Stranded | Stockholm, 1982

In the twenty-first century, Swedish pop is synonymous with a certain ruthless muscularity, often considered the result of pop producer Max Martin’s heavy-metal past. But even here in the early 80s, fey New Romantic band Lustans Lakejer (Lackeys of Lust) takes time out from frontman Johan Kinde’s baleful sneering about diamonds being a girl’s best friend for a flashy guitar solo that fits into glam, post-punk, and metal traditions. Lustans Lakejer were a novelty in late-70s/early-80s Swedish pop, a well-dressed band who proclaimed that their clothes were as important as their music; when Kinde had finally had enough of posing, he dissolved the band, only returning to the name occasionally as a solo act over the years.

5. Lillie-Ane Meg selv RCA Victor | Oslo, 1983

If I were approaching these mixes sensibly, I’d only be including music that had been reissued on CD, or was available on streaming platforms, or something. But having access to the more eclectic and unremunerated catalog of YouTube has ruined me: once I’d heard Lillie-Ane, I couldn’t not include her. She’d been the voice of Norwegian synthpop trio Plann, but her classical training and avant-garde sympathies made her solo material — what I’ve heard of it, which is not enough — weirder and more galvanizing than the rather derivative music she’s still better known for in Norway. She died in 2004; her swooping voice and dense harmonies on “Meg Selv” (Myself) deserve wider appreciation.

6. Arbeid Adelt! Lekker Westers Parlophone | Brussels, 1983

Flemish Belgium in the 1980s is justly famous for its industrial-music scene, with acts like Front 242 and Neon Judgment pioneering sounds that would form the basis of many electronic-rock hybrids in the 1990s. Few of them sang in Dutch, however, apart from Arbeid Adelt!, whose early records were prankstery lock-groove new wave. Once Luc van Acker (later of Revolting Cocks) joined, though, things got harsher, and “Lekker Westers” (Yummy Westerners), with its satirical singsong melody over dissonant grooves, is halfway between their Devoesque beginnngs and the industrial harshness that put Belgium on the map

7. Geisha Kesä Johanna | Helsinki, 1983

The all-female Finnish trio Geisha only released a single EP during their brief existence, but because it was on the legendary Helsinki indie label Johanna, they’ve been compiled and fondly remembered by Finnish rock fans for decades since. “Kesä” (Summer) is of a piece with the moody, dry sound of Finnish goth rock of the period, but its danceable rhythm and spectacular clattery all-percussion instrumental break suggest that they had a lot more to offer beyond being a distaff Musta Paraati.

8. Det Neodepressionistiske Danseorkester Godt nok mørkt Genlyd | Aarhus, 1986

A Danish band that began as an art-installation soundtrack and ended as a sampladelic pop act, DND (for short; their full title, as might be presumed, translates as The Neodepressionist Dance-Band) were rather inspired by the Talking Heads’ combination of dance rhythms and irony-laden cultural critique; their debut album was called Flere sange om sex og arbejde, or More Songs About Sex and Work. This song, “Good Enough [in the] Dark,” features leader Helge Dürrfeld mutter-rapping about the limits of perception while a passionate saxophone wheels endlessly and a sassy chorus chants the title.

9. Cherry Vang me Vertigo | Utrecht, 1982

Cherry Wijdenbosch is, if not the first person of color to appear in these mixes (which reflects my desire to keep back some key acts from former colonies for later inclusion around the globe more than any unadulterated whiteness of 80s European pop), is certainly the first Black woman. Of mixed Indonesian and Surinamese (which latter is to say African slave) descent, she had a couple of jazz-inflected Nederpop hits in the early 80s before becoming a cabaret act. Her debut single, “Vang me” (Catch Me), is a breezy but clear-eyed love song that borrows some of Jona Lewie’s dry music-hall delivery and adds a Manhattan Transfer kick to the middle eight.

10. Tappi Tíkarrass Kríó Gramm | Reykjavik, 1983

The eighteen-year-old singer, with her clear, youthful, and powerful voice, is nearly the only reason anyone has heard of this post-punk band; if she had not gone on to front bands K.U.K.L. and Sugarcubes, not to mention her own global superstardom as a mononymic solo artist, Tappi Tíkarrass might be an undiscovered gem rather than a pored-over Da Vinci Code by which adepts seek to unlock the mysteries of her sacred genius. This song, which predicts the soft-loud dynamics of 90s alt-rock with almost a shrug, is, according to internet Björkologists, the cry of an elderly man searching for his tern.

11. Eva Dahlgren Guldgrävarsång Polar | Stockholm, 1984

Discovered on a 1978 talent show, Dahlgren wouldn’t be a true pan-Scandinavian star until her 1991 adult-pop classic En blekt blondins hjärta (A Bleach Blonde’s Heart), but I really like her 1984 album Ett fönster mot gatan (A Window to the Street). The title of this slow-burn anthem, the leadoff track, can be translated as “Gold-digger’s song,” and is a reference to an early twentieth-century Swedish hit about Swedish immigrants failing to strike it rich in America: Dahlgren interiorizes the sentiment, making it a song about a streetwalker who dreams of finding a place where she can “kiss my brothers and sisters.” She would come out as gay in the 1990s, and is married to her partner of many years.

12. Svart Klovn Knust knekt Uniton | Oslo, 1983

Probably the most legendary Norwegian minimal-synth (I almost said synthpop, and then I remembered a-ha) single, “Knust knekt” (Shattered Jacks, as in the playing card) is a miniature masterpiece of mood. The lyrics, as far as I can determine, are standard post-punk gloom about moral corruption, but the sound and image of Svart Klovn (Black Clown), the alter ego of Svenn Jakobsen, are among the most striking in all Scandinavian pop.

13. Het Goede Doel Net zo lief gefortuneerd CNR | Utrecht, 1984

Dutch new wave duo Het Goede Doel (The Good Cause) were second only to Doe Maar in popularity, with a string of sarcastic, melodic hits that occasionally remind me of mid-period XTC. The opening orchestral hits belie the crooning tenderness of this portrait of callowness and privilege (the title is “Just So Sweet [and] Wealthy”), only tipping its satiric hand when Henk Westbroek sings on the prechorus that naturally he wanted to marry his mother.

14. tv-2 Vil du danse med mig CBS | Copenhagen, 1984

Akin to U2 in their longevity, success, and consistency (they’ve had the same four-man lineup since 1982), tv-2 are perhaps the most successful Danish band ever. Formed from the ashes of prog-hippy band Taurus and new-wave band Kliché, they started with an industrial sound that gradually brightened: this song (Will You Dance With Me) is one of the signature sounds of mid-80s Scandinavian pop. With muttered verses about how shitty men are after the initial bloom of romance is over, the chorus (and its saxophone riff) returning constantly to the moment when he asks her to dance is a sharp and poignant evocation of memory.

15. Lolita Pop Regn av dagar Mistlur | Stockholm, 1985

The small city of Örebro in inland Sweden was far distant from the Paisley Underground scene swirling around Los Angeles in the early 80s, but a band with the same influences — the Velvet Underground, Roxy Music, the Beatles — formed there, and with crisp Stockholm production seemed to predict the alternate-tuned 90s of Tanya Donelly and Letters to Cleo. “Regn av dagar” is “Rain for Days,” and the lyric is similarly 90s-depressed, while the rock band behind singer Karin Wistrand chimes and chugs along.

16. Cirkus Modern Karianne Sonet | Oslo, 1984

The songs I’ve chosen from Norway are all representative of more left-of-center pop than the more mainstream work I’ve chosen from Sweden and Denmark. Partly that reflects the the fact that Norway was just a smaller regional scene, but partly it’s that Norwegian pop is not well documented online. Cirkus Modern were a moderately successful post-punk act who produced two albums and an EP, which makes them by far the most prolific Norwegian act represented here: “Karianne” is a joyfully raucous (and slightly unsettling) jam that reminds me of when the Cure went pop circa “Lovecats.”

17. Madou Witte nachten Lark | Antwerp, 1982

The Dutch musical genre of “kleinkunst” (literally “little art”) can be compared to the German “kabarett” (cabaret) but includes folk-musical forms and socially critical lyrics. Madou, an experimental Flemish band centered around singer Vera Coomans and pianist and composer Wiet Van de Leest, brought kleinkunst into the new wave scene, with dark songs about abuse, incest, and suicide. “Witte nachten” (white or sleepless nights), despite its vaudevillian bounce, is sung from the perspective of a child whose mother shares her bed to escape the father’s fists.

18. Tuula Amberla Lulu Selecta | Turku, 1984

I may have stretched the definition of new wave to the breaking point with “Lulu” — the jazz manouche violin and general 1930s air (at least until the crisp Cars-y electric guitar solo) might sound too much like a nostalgia act for the rest of this mix. But Tuula Amberla was the lead singer of gothy post-punk band Liikkuvat Lapset, and the lyrics, written by doctor and songwriter Jukka Alihanka after a poem by sculptor and architect Alpo Jaakola, are about the decadent nightlife of modern Helsinki, as the video makes clear.

19. Grafík Þúsund sinnum segðu já GRAF | Reykjavik, 1984

Iceland’s vibrant and highly original music scene has gotten really short shrift from this mix, thanks to its tiny population. There’s lots more to dig into where this came from. But when I ran an initial survey of European music of 1984 some months ago, this sparkling gem of a pop song stood out immediately. Part Huey Lewis (that shiny production), part Prefab Sprout (those lovelorn melodies), all Grafík, perhaps Iceland’s premier pop-rock band of the 80s (at least until the Sugarcubes came along), “A Thousand TImes Say Yes” is a plea for total romantic commitment that comes across in any language.

20. Klein Orkest Over de muur Polydor | Amsterdam, 1984

One of the key songs of the Cold-War 80s, “Over de muur” is sometimes classed as a protest song, but if so it’s hard to parse which side it’s protesting. Making a clear-eyed examination of the repressive idealism of the Communist East as well as of the gluttonous “freedom” of the Democratic West, singer Harrie Jekkers’ real sympathies are with the birds who can fly over the Berlin Wall at will, as he imagines a day when the people will be able to do the same.

21. Di Leva I morgon Mistlur | Stockholm, 1987

Born Sven Thomas Magnusson, he adopted the stage name Thomas Di Leva when he joined the punk band the Pillisnorks as a teenager. His next band was Modern Art, and he went solo in 1982, at the age of 19. One of the most fascinating and creative Swedish pop stars of the early 80s, he drew inspiration from glam, electronic experiments, traditional pop, and eventually, Eastern mysticism. Those New Age leanings are all over “I morgon” (Tomorrow), which combines an up-to-the-moment U2 chug with Di Leva’s early-70s Bowie wail to create an extended, lightly trippy meditation on being, time, and the unknowableness of reality. He’s since become a New Age guru and life coach; but his early music is still really interesting.

Okay, that’s it. Join me next time when I’ll be looking at the Neue Deutsche Welle (and the Neue Österreichische Welle, and the Neue Schweizer Welle). I’m over the hump: there are three mixes left to go in this series. Thanks for reading and listening. If you want to talk to me about what I’ve compiled, or what I’ve said about it. I’m around.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Schiffentrückung

(Haebarik's power: 2 + 3 + 2d6->9 = 14; moving back in time a bit for this one, but I still had a dangling plot-thread so most of this happened 200 years ago in game time)

Previously, we spoke of the great Scout-King Wera, who sailed across the waves and was last seen sailing into the inner sea that misty Laasera engulfs. Wera, first cause of a thousand meetings between a thousand peoples, who will forevermore be hailed as the greatest Azure King, who delved into great danger to refind an old friend's kin. What happened to him?

Well, he died.

But before that, he sailed west, into the foggy bay encircled by Laasera, past islands of floating mangrove-root and the transient fiefdoms of ohmlings, ever closer to the heart of the rainforest, ever closer to the great golden city that the rumors told him of.

Instead, he finds a flooded crater crested with ruins. Anything of beauty or value was long since picked off the crumbled walls and diffused through the forest in a chain of thefts and murders. No trace remains of the original inhabitants: the few Atai survivors having long since moved on.

Wera could have declared his self-imposed quest impossible. He could have turned back, to the city not yet named after him, and be hailed as a hero. He could have passed on his ship, and lived in splendor the rest of his life: none would dare challenge his boldness after this great journey. But he does not.

He continues to sail the coast, searching for any sign of passage, exchanging gifts with the few local tribes so they may serve as scouts. He learns the lay of the land and leads expeditions through the forest, chasing after any hints of Atai presence. Even as an unknown disease takes hold of him, as ache and fever condemn him to a bed, he continues looking, continues to peer over maps and chart new courses.

And it works. Hundreds of Ataila he finds, some living among humans, some settled in tiny encampments, some camping as solitary hermits. They are brought before his sickbed, where the deathly-ill king offers them a new home, across the waves, new and holy and safe. His tales are, by this point, based more on fever dreams than Messonir maps, but somehow none disbelieve his claims.

And so they sail south, ship packed with Ataila (who, thankfully, need not eat), guided by the ever-weakening instructions of the savior-captain-king. Past Incarien they go, past Tuula, past those volcanic islands that were Erland's first mark on the world. The wind always seems to favor their sails, and though the journey is not without peril, it is a swift one.

Land is sighted: a new land, poorly marked even on their charts, of tall peaks and dense forest, of misty plateaus and green hills. A crewsman rushes to the captain's bedchambers to report the good news, only to find him dead, a smile on his face.

With a mix of gratitude and sorrow, the Ataila disembark, and begin construction of a new city, the first in this realm. They call it Kaluutalo: the second house of the Ataila.

And what of Wera's crew? They swear an oath of secrecy and make the distant journey back to human lands. In every port they stay but briefly, speaking not a word of the Atai. At last, they return to Palk, where they sorrowfully report the death of the king, and beg the queen to let them stay aboard his ship for one more night, so they may hold a wake for his soul: this request is granted.

But with the next dawn, they and the ship are gone, having departed under cover of night. Vessels are launched in pursuit, but the royal flagship still bears the dragon-wing sails crafted by the first king Palk, and no lesser ship can catch up to it. Aboard the flagship are the sailors, their families, and one particular soul, smuggled out of the palace during the starlit night.

They retrace their journey, outrunning news of their flight at every port, and at last return to Kaluutalo. They will never leave: this land is theirs to settle, too.

And so Vainaa, Atai-diplomat of the Azure Reach, is reunified with her long-lost people, of which some still remember her name, and may pay respects to the remains of Wera, who to them was pupil and master and hero all.

In later generations, the humans are quick to take up worship of Velarië, and come to honor her for the creation of land and life both. But they likewise worship the long-dead captain, who they hold to be half-divine in nature.

At the center of their city, still floating in the harbor, is the royal flagship still. It serves as the holiest of their temples, manned and maintained by a select priesthood, and still bears the blessed sails that once served as Möpatäriäle's wings.

And enshrined in the captain's quarters, dressed in full regalia and preserved in golden resin, lies the body of Wera. His worshippers know that one day, when his people need him most, he shall re-awaken. He shall open his eyes, and brush aside his amber shell, and assume command of his ship once more; and they shall be ready to sail with him where they must.

(Create Order (4) among the Atai (with a few humans mixed in there) to create the Devotees of the Captain-King, then Command Race (3) to have them found a city in the Forgotten Lands.

The order's actual tenets are a mix of the more altruistic Seeker values with a strain of apocalyptic Atai beliefs mixed in, emphasizing charity, sacrifice, and the value of all life.

7 points remaining)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Velarië rolls 2d6 -> 12, for a total of 1 + 12 + 1 bonus = 14 power. She spends 2 of that power to Shape climate in the existing region surrounding Etevassin; she spends 2x3 and 2x2 power to Shape land and Shape climate in the area to the southwest. Her remaining power is 2.

To protect the homeland of the Atai, Velarië causes thick jungles, much like those of her Isle, to grow up in the lands surrounding Jokaina, the Gulf of Storms. The Atai work to tend these jungles and help them expand; within a few centuries, they are deep, dark, and full of all kinds of beasts seen nowhere else in the world. The Atai call them the Laasera, the Forests of Smoke, because of the darkness and fog they produce.

[Southeast Incarien, showing alterations to the region. Velarië’s cartographer took the liberty of touching up the vegetation added to the eastern peninsula, but attempted to respect the spirit of the original artist’s work.]

To the south, she works to raise new land, which the Atai call Tuula, the Southland. It is attached to but distinct from the existing land of Incarien. Most of this region is temperate and green; but in the far south, in Saarima, the land grows colder and more barren, and she fills it instead with hardy scrub and small animals adapted to this harsher climate. The major feature of Tuula is the Tuukasinen Mountains, which divide the central regions of Lanai and Visalen from the outer regions of Uukulo, Iriola, Taama, and Saarima.

[A map of Tuula, showing the major sub-regions of the landmass. Velarië’s cartographer just realized that she forgot to add some important lakes to this map, so please check the Magma image for the fully updated version.]

#world 02547 diegesis#velarië's cartographer is also getting over a cold#and so apologizes for the lack of narrative detail in this update

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A place for boats to visit

(SUMMARY: the humans of Lekesh, having met with the Messonir and obtained their maps, launch an expedition westward. They visit but do not settle Baled and the Isle, and establish a city called Wera in southeastern Incarien. Spurred by a first-contact epidemic, many humans migrate west. Some are turned away and found a city far south, in northern Tuula; others drift into the sphere of Unimaa and bolster its seafaring capabilities)

The blessed Messonir may, in their youth, fly far above the world, and look down on its many realms and peoples, and so they were the first to know the full extent of the seas and lands. But where human map-makers find themselves relying on accounts from voyagers and traders, plagued by sparse and enigmatic sources; the Messonir instead struggle to reconcile thousands upon thousands of contradictory and all-too-verbose accounts.

For how well can an untrained Windborn, little more than a child, remember the duration of an ocean-spanning flight? How easily is an island missed, a coastline misjudged, a city or mountain misplaced? How many flew to the lands of Zaag, or into the mists of Omeara, and found their recollections slipping away like so many handfuls of sand?

How many lakes in the tall mountains of Tuula? How wide the sea between Incarien and the Occident, how far north the cape of Morne? In the north, where few Windborn dare fly, does a continent protrude from the ice, or is it a mere mirage? Though scholars, after ages, agree on some reasonably accurate charts of land and current, the limitations of their sources remain a sore spot, and all are convinced that their pet theories of geography would be confirmed if those darn kids would just learn to tell coastlines from barrier islands!

When humans show up, in ships, seaworthy ships, it does not take long before the scholars grant them access to their maps and propose a series of expeditions.

The response this provoke is beyond their wildest imaginations. They expected gratitude, perhaps businesslike interest: not the near-religious fervor that seems to seize these humans. Expeditions are prepared at once, and ships depart west within weeks.

Alas, the flurry of activity has a dark side. The swift messenger-boats dispatched north carry another product of the human-Messonir exchange, and for the coming decades the people of Lekesh (and any humans they may encounter) shall be plagued by Blood-Flu, a disease that brings chills, high fever, severe aches, and may progress to infections of the eyes and lungs. A majority of the continent will in time be infected; a few percent of them shall die. A comparable amount will flee; to Rasira, to Nulat, and to newly found Incarien.

(The Builders are hit harder than most, and build little for a significant time, and some of them trek into southern Rasira, but few end up braving the oceans)

(Among the Penitent, a number of sects struggle to explain the supposed find of Incarien and the spreading plague. The most accepted interpretation declares that this illness is a trial of compassion, and that the gates to the world have been opened so they may go out and cure this illness everywhere. Many move to plague-struck regions and offer what aid they can; inspiring and teaching others, and sharing what knowledge they gain by doing. In time, many ships come to bear a medic who can trace his roots back to western Lekesh.)

But who braved the way for these waves of settlers? King Wera, already called 'the great' for his discovery of Nulat. With five ships, he sets sail from Tsallosis and steers into the westward current.

The first land they sight is black and angular, and great cliffs block access at first. After a day of sailing, a landing site is found, and a small ship carries the first human feet to Baled. But the water is foul, the fearless beasts taste of metal and sulphur, and the land is without lumber-trees, so Wera declares that this isle of monsters holds nothing of value, and presses on westward.

They pass over a deep and quiet stretch of ocean, and for three days and nights dark dreams plague the crew, and few obtain restful sleep. But then, a shore is sighted, stretching from horizon to horizon, and Wera declares Incarien found.

The land, of course, is inhabited. Settlements and chiefdoms dot the land, each commanding handfuls of farming villages in a manner not too dissimilar to the Seeker's homeland (but lacking an unifying queen as they do). Wera makes offers of friendship and alliance between local leaders and the Azure Throne; enough of them accept.

The king then splits his fleet. Two ships remain, and their crews begin construction of a trading post and harbor, the settlement ruled by a royally appointed governor. For a time, it will hold one of the few harbors equipped for the great ships of the east, and thus control the flow of much trade. In time, it will become the largest city in this part of Incarien, gateway and trading hub; loyal to the Azure Throne at least in name. Its original name is irrelevant, for its citizens swiftly rename it Wera after its founder.

(Command Race (Create City) 3 pt. - 10 remaining)

The flagship travels west alone, chasing tales of a mystical city inhabited by magical beings of starlight and steel-leaf. Some wonder why Wera would put his trust in such vague rumors, forgetting that it was an Atai who tutored him in childhood and remains one of his closest friends today. Of his fate, we shall speak more in time.

One ship travels north, drawn by reports of great cities that cluster around a westward river. What they find is beyond their wildest imaginations: Unimaa, humanity's greatest city, which sits at the mouth of a great river and commands all trade along its length. The banker-priests that command it are quick to realize the value of these strangers, and swiftly forge an alliance between their realm and the Azure Throne (while also guarding their own control over trade along the Nak).

And the final ship travels south, to explore the great isle marked on its maps, and from there return home with an account of their travels. It finds the blessed isle of Velarië, with its many strange beasts and plants, and obtains some of them as prizes, though the crew dare not venture far inland. Then they head east, finding a current where the Messonir promised one. They sail past the lands of the Qurri, travel northeast along Nulat's coast, and reach Tsallosis once more.

(Pictured: the journey of Wera's fleet (red), the ship sent to Unimaa (pink), the return route (green) and the westward expedition (orange). At the place where they converge lies the city of Wera)

In the great Messonir city, their accounts are eagerly received by the crowds of humans arriving from the north. Some of them seek fame and fortune, some are driven by religion, others are simply fleeing the blood-flu: all are eager to reach Incarien, their promised land.

The Great Fleet carries thousands: mostly humans, but some Messonir. The first ships to arrive are admitted into Wera without issue; but then more arrive, and more. The local rulers grow increasingly concerned: they were promised trade and riches, not these huddled masses!

Unwilling to strain his alliances, the governor turns many ships away, drawing onto shows of force where words prove insufficient. Most turn north, to Unimaa, where many find work as builders, farmers, and merchant-captains.

But even Unimaa struggles to hold all these newcomers, and so its bankers sponsor a venture that redirects some ships far north, where they displace the villages of native whalers and found the city of Vaarik, vassal of Unimaa, gateway to further seas, and harbor to many whaling-vessels.

(Command Race (Create City) 3 pt. - 7 remaining)

The few ships that turned west, however, quickly find that dense jungle begins where human settlement ends. In a journey almost as long as the one that brought them to Wera, they make their way south, bypassing the gulf of Etevaasin, rounding the southeastern cape, and at last arrive at more temperate locales.

There, they found a city which they call Ker Atel, which means 'far road'. The first years are rough, and the settlers struggle to adapt, but in time they learn that their region contains plants never-before seen in Incarien or Lekesh, and learn to cultivate them and profit from their trade. As such, this distant settlement becomes reasonably prosperous in its own right. They still trade with the Seekers, but pretend not to be subject to them, and elect their ruler for life by popular vote, combining customs of the Azure Throne and Free City.

(Command Race (Create City) 3 pt. - 4 remaining)

All these places will continue to grow over time, but overseas settlement will slow down after the initial wave of excitement has subsumed. Coming generations of Seekers will lack their cultural obsession with refinding their lost homeland, and simply focus on cultivating their intercontinental connections, tussling with the Builders for Rasira, and exploring ever newer lands. The Seekers will dominate trade between all these places, though the Unimaa-based bankers are still a major player in trade around northern Incarien.

(Major Seeker trade connections shortly after the events of this post; each is of course connected to many smaller networks and routes; only oceanic connections are depicted)

(on second thought i should put connections in there to the Likani in eastern Nulat but I forgot whoops, alternatively assume those trade routes were a bit slow to form in the excitement of it all)

#i have no real further plans for any of this#just wanted to have a big event where we get interoceanic travel going#tried to work some hooks in here so if you see something you wanna expand on go nuts#world 02457 diegesis#apologies for the huge post#i hope the images make up for it

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Free Isle

Tepponilamek has 10 points left this turn. Inspired by a vision in the Reflecting Gallery, a young Usfir leads refugees from the Lanai War to the Isle of Gīthorg, just off the coast of Tuula. Over the years, many more refugees arrive, until its capital Bremtuda is a bustling, multicultural city (-1).

The Isle of Gīthorg lies off of the western coast of Tuula, in the vast Bay of Bekkem, into which flows the river Thurdeir which originates at Thorfuintir and drains much of northern Lanai. The Isle itself is rocky and craggy, with only two bays providing a safe anchorage; but inland it has well-watered vales and fine pastureland, as well as thick forests and even rich veins of iron in a few hills. With the abundance of land in Tuula, and the difficulty of reaching the Isle, it is unsurprising that even into the Fourth Age few folk dwelled there. The two bays, which lay near to each other, had small towns known as Brem and Tuda, while a few farming villages and hamlets stretched further inland.

The Island would soon be transformed by the arrival of refugees from both north and south. From the north, many Usfir flee to the Isle during the long Lanai War; the first boatloads are led by a young Usfir of a renowned clan named Tepinilma. Tepinilma had long been haunted by dreams of cold and death, of chill winds sweeping down from the Tuukasinen across Lanai, and of icy hallways hung with maps of a vast Dzadek dominion. In response she gathered all the folk of the towns where her clan held power who would listen to her, and led them to sail west to Gīthorg. The refugees led by Tepinilma find safety on Gīthorg, for though the Dzadek do seize a handful of coastal towns on the Bay of Bekkem, they have no skill or knowledge for sailing.

From the south come refugees from the expansionist wars of the Havonaar, or escaped slaves from the Fuligin City. Most of these are Usfir by ancestry, but some are Titans who make the difficult journey across the water (for Titans are ill at ease on boats, which struggle to bear their weight) and others are humans and Sun-divers from the Occident, whose trading ships have been preyed upon by the Havonaar. A few even are drones of Sīnobbe or Alēmdanna, who by a twist of fortune escaped the enslavement of the Deep One that birthed them and now live fully independent lives.

Gīthorg welcomes all of these refugees. At first there is conflict between the “original” inhabitants of the Gīthorg and the refugees under Tepinilma; the richer folk of Brem and Tuda attempt to force the refugees into usurious loans to secure the seeds and tools needed for their first few harvests. Meanwhile many of the natives, rich and poor alive, sought to establish laws that made them full citizens of Gīthorg, and the new arrivals merely residents, in order to entrench privileges and rights for themselves. Yet Tepinilma refused to allow her people to be treated that way; her stubbornness pays off over the years as the population of the Isle continues to grow as more refugees arrive from north and south. Soon settlements blossom like flowers in spring across the Isle, and the port towns of Brem and Tuda merge as they grow into the city of Bremtuda.

Perhaps because of the shared experience of suffering that informs so many of the settlers of the Isle, it is a notably egalitarian place; Bremtuda and major towns establish local councils to govern the affairs of each region of the Isle, and a Grand Theng is held each six months in Bremtuda, where representatives from the whole Isle gather to discuss matters and pass laws. In addition, Gīthorg, being a literal isle of stability in an increasingly violent Tuula, becomes a key port where Occidental traders visit, and the Refracted soon begin establishing themselves there.

1 note

·

View note