#using ai in art discourse would be more like modern art discourse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hear me out before shooting me in the head, but I can actually think of several interesting (arguably mixed-media) art pieces that could be made using AI as a tool, and you know there's some art student out there who has a really funky idea we're missing out on because of the current state of AI

It's just a shame that instead of taking AI as a tool for new, interesting art, people are using it for things that could and should be done by human artists and instead producing souless output with no artistry

And if you doubt me that AI could be an actual tool/medium, here's a few ideas off the top of my head:

- a faux art gallery with a series of AI-generated images. The human artist has taken the role of "curator" and written blurbs that discuss the themes and symbolism of each piece. It's a commentary on how humans will find meaning in the meaningless

- a series where an artist has a prompt that they change one word at a time, and document how that one word changes the output. Could be an exploration of society's biases laid bare by algorithmic extrapolation - think of that post where someone pointed out that inputting "autistic person" produced nothing but images of sad young white boys

- entering a prompt that is difficult to represent literally (like the "secret horses" image) and attempting to recreate it in physical space, through photography, painting, or sculpture. An interesting practical challenge, themes of blurring the divide between the digital and physical could be explored

- a story where a writer is trading off writing each paragraph with AI, and trying to steer the story in the direction of a romance, while the entirety of the AI's dataset is the complete works of HP Lovecraft

- I don't know much about coding but I think there is an argument here for "artistic coding", where the final output is machine generated but the artist has written the code and made deliberate artistic choices in the process (a bias toward green, favoring some parts of the dataset more heavily than others, etc).

I don't buy that art made with AI is automatically not real art. Even things like "what prompt did you choose" and "what did you choose as your dataset" can be meaningful artistic choices. The problem lies in suggesting that the output is the SAME THING as a digital painting or whatever. That's like arguing a painting and a sculpture are the same thing because they're both of a raven. You can use AI as a tool to make art if you're engaging with it intentionally as it's own medium.

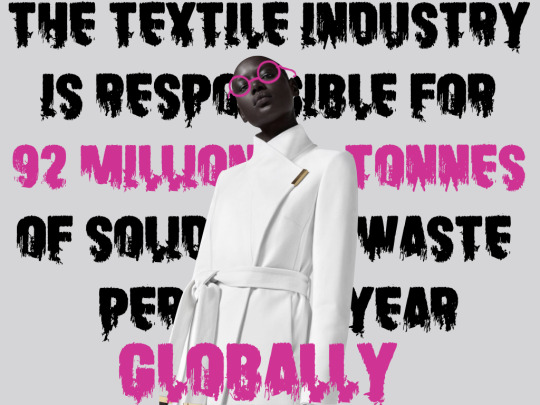

But, obviously, the bigger issue here is the misuse of AI for things human artists could do better and SHOULD be doing, and the unethical usage of other's work for machine learning, and the overuse of AI being so bad for the environment (I doubt the water and energy usage would be a big deal if AI wasn't being used constantly for things like google overviews and homework). I'm just lamenting on the cool art we're missing out on because Harris in Marketing wants to type "company logo bird" into an image generator instead of hiring a graphic designer

#long post#like we can agree to disagree on what counts as real art#but i think if it werent for the ethical problems with ai as it stands#using ai in art discourse would be more like modern art discourse#where people are like well you just nailed a banana to the wall that isnt art#but the artist actually has put a lot of thought into nailing the banana to the wall#ya know?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bound: Modern Love by @tackytigerfic

Right, I have some mixed feelings over this bind. Buckle up.

Firstly, and most importantly: what a joy to bind this magnificent masterpiece by Tacky! If you haven't read it, you must. It is a delightful examination of a Harry who is lost and troubled, and a Draco who's found a very unexpected path of his own after the war. And it features a hot priest, so. Go. Read.

Secondly, I obviously drew my design inspiration from Bowie (the source of the fic's title) for the cover art of the book:

Re the cover:

a) god DAMN black bookcloth does not HIDE A THING, and apparently I took shit photos of the book so enjoy this linty mess?

b) GLITTER HTV. Not that hard to work with! ALSO SO SPARKLY but again, shit photos, so you cannot tell. Suffice it to say, it was a fine choice on my part.

c) On a less happy note: I dithered over whether to discuss this because ugh who likes being publicly wrong but BUT. I did use gen AI for the cover art of Harry; I made this choice before I had spent as much time as I now have reading the discourse on AI and art, and I would not do it again. I did edit and rework and blah blah blah I'm still not down with gen AI anymore and I regret my choices even if I visually enjoy the result. I did make the rest - arrows, title, author design, etc. But yeah. Bad Plor. Plor is learning and growing publicly! Which is so uncomfortable! Don't use AI for art, pay artists, etc etc. If I redo this bind, I will redo that part of the cover/artwork and I bet you anything the result will be loads better. (And I will send Tacky a new copy if/when I do this.)

Moar photos:

Moving on, other highlights:

sewn endbands using embroidery floss, including gold, which is lovingly called the Devil's Asshair in cross-stitch circles and for good reason but GOLD. SHINY.

I sent Tacky the second copy of this bind because it was technically more proficient and I redid the typeset for the second go, but I am including a couple of photos of my copy below because I think the yellow colour for the main Harry figure is a better shade on my copy and I had sparkly arrows on this one. (I ran out of both options for the second bind, sigh.)

The typeset includes Tacky's two follow-up stories in the Modern Love series because I wanted them all together.

The inside of the typeset includes artwork by chachisoo and @kk1smet (with permission) but I will save photos of those gorgeous works for my next post because

I made a paperback version of this! Which I will share separately!

(Plor's copy pictured above.)

#bookbinding#fanbinding#case binding#drarry fanbinding#drarry#hp fanbinding#sewn endbands#tackytiger#modern love

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Venting and rambling about ai art discourse

Feel free to ignore this + this isnt an invitation to argue back and forth with me about ai

My tag system on main for years now has been

#art = abstract art

#representational art = all non-abstract art

( + #dreamscape = art that can't be neatly categorized as abstract or representational + art that reminds me of dreaming )

Bc at the time I created this tag system i was very fed up with abstract art and modern art being dismissed as Not Real Art by some assholes and i wanted to put abstract art first in my space and have representational art be the one that needs a descriptor to differentiate it from "normal"/"real" art

Currently holding myself back from doing something similar to be petty about the never ending ai art backlash/discourse

Haven't been posting my abstract art or ai art online much lately but i still make a lot of both (+ getting back into writing and prob won't be posting much of that either). Sharing art online, other than with close friends, seems like hell to me rn.

Maybe someday i'll start posting my art again it just sucks that anytime i go on any social media from discord to youtube theres an 80% chance i see people shitting on the artistic mediums that i'm most passionate about

And its not like the ai hate train has slowed down the rancid attitudes around abstract art lol, not that I'd stop making AI art if abstract art was more respected

Abstract art is the easiest and most rewarding way for me to express myself creatively and it gels so well with my perfectionism issues bc perfection is Not the point (except when it is, but then its an artistic choice not a constant obligation for every piece). A piece about grief doesnt need to have perfect straight lines or symmetry, the art can be messy if it suits the tone I'm going for.

And AI image and music generation is very exciting to me! I've always been curious about what it would be like getting to see the creation of a new way of making art and its been very cool being able to somewhat follow AI innovations since 2018 and then get to experiment with it myself once more ai tools became accessible!!

Whether im the ai art im making is abstract or representational, i love not having full control over the result! I love bouncing ideas back and forth with the AI. I love having to combine my visual art skills and my language/description skills.

I use midjourney et al. the same way I'd make my OCs in dressup games while brainstorming ideas. Mindless doodling that can often lead to writers block breakthroughs.

I also use midjourney et al. to make quick vent art when I'm feeling strong emotions just like I'd do in my sketchbook or in my digital art apps.

And sometimes i'm using ai to spend hours trying to make something very specific i want to create.

Idk its all just tools to me. Midjourney. Paint Tool Sai. Pen and paper. I get the same joy/relief out of making art with all of the above

Im not aiming for fame or money, i make 0-200$ a year from art, usually 0. I just want to have a little corner of the internet to share my images and reach a handful of ppl who appreciate them and want to discuss abstract & ai art with me thats it. Im not coming for your art job, i dont allign myself with corporations aiming to further disadvantage workers in artistic industries or artists who freelance

Anyway reason #2 i slowed down on posting art is grief has been kicking my ass these past 4 years. Lots of deaths in the family + death of a friend. some relationships were fractured and im grieving those as well.

Reason #3 is started full time library job in november 🎉 its wonderful and its exhausting and im still finding my rythm after years of being chronically un(der)employed and/or in college, but hopefully once life settles down more ill have more and more time to spend on art and writing

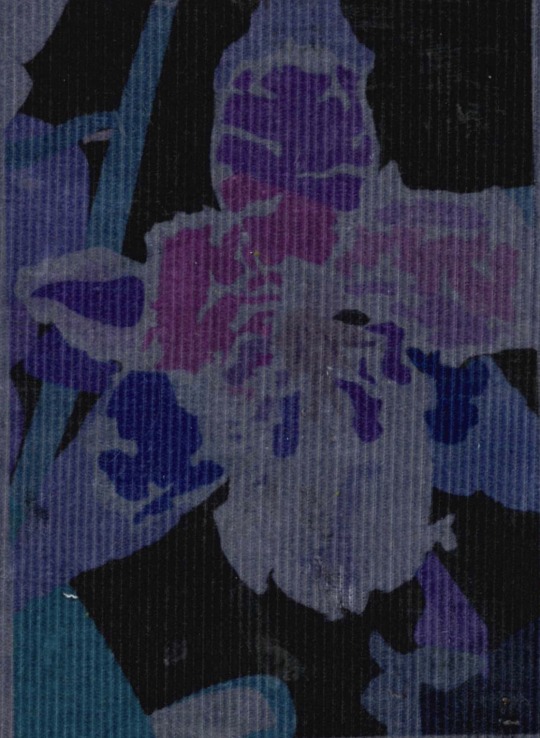

Havent vent posted in ages and it feels weird doing it on one of my art blogs so im going to end this with two of my recent(ish) pieces on grief, first made in onelab (not ai, android art app i make 80% of my digital art in) and second in midjourney

Thanks if u read all/most/some of that :)

Think i just needed to be like "man this sucks" so i can move on to "anyway! Art time >:)"

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

op is indeed talking about the joy of creating art for the process of making rather than the outcome. i have no issue with people who find delight in this aspect of artistry/artisanship, so i take no issue with OP's "i think using AI is boring" (fine by me!) nor "i think using AI means having no autonomy" (wrong, it's only like that if you stick to the default settings, similar to how a basic picture taken on your phone doesn't give you much autonomy - but overall, no big deal).

i do however take an issue with terms like "reliance", "inhuman objects", "laziness and vagueness of thought" opposed to "self imagination and skill", and the idea that "the emotional aspect of creation of art is lost when a machine makes it for you", all stated like they're self-evident.

not to be overly snide, but i am, personally, quite annoyed to see everyone on this website only started sharing opinions The Nature Of Art And The Creative Process And The Emotionlessness Of Machines after they saw robots capable of painting pictures of their blorbos, as if the wider art world hasn't been debating these ideas for over a century now, and as if there weren't many recognized art forms involving handing a machine the wheel long before AI.

"Wouldn't using multiple codes and a combination of ais to create the desired output be the skill of handling ai and software, more so than actually having the skills to be able to put your thoughts into creation"

not sure what you're trying to say here. are you saying digital art has a process that goes "develop drawing skills -> use drawing tools to put your thoughts into a piece", whereas procedural art's process is "develop software skills -> cannot use software tools to put your thoughts into a piece"? i don't believe "transferring thoughts" is a prerequisite to making art in the first place, regardless.

when it comes to photography, i would say it is widely considered an art, much like cinematography.

as for how "multiple exhibits of modern art show that it is the process that makes art", this is certainly possible, but (notwithstanding the fact that AI art has been shown in modern art expos/museums since 2019, long before AI Art Discourse began) i am specifically referring to conceptualism in the post above.

on that note, you say "conceptual art is idea based and an idea does not constitute artistic creation it is something that leads to it", which is not at all in line with commonly accepted definitions, such as Sol LeWitt's:

In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.

emphasis mine. LeWitt is clear here: in conceptual art, the idea and decisions matter more than anything, and the execution is a formality. the idea is artistic creation!

again, i have no quarrel with anyone who decides AI is not a creative process. but when this bleeds into ideas like "loss of autonomy" and when people start telling me "this is laziness, these aren't your thoughts anymore, you have lost the emotion of creation by using a machine" i get annoyed.

(and in fact, i am doubly annoyed by people who oppose good & emotional Photoshop art to soulless machine-made AI art, because to them digital art is totally normalized, and they can't even imagine that we had entire movements about how drum machines, Photoshop, mocap, CGI, etc etc suck; i do not have much love in my heart for the "all the guys who said 'this is lazy impersonal emotionless art' were wrong before, except today's guys, they are right, this is where we must draw the line" mindset.)

the fact remains that nobody is questioning your creative process preferences (except a few techbro weirdos) and nobody is forcing you to "give up the autonomy to create art from your own animation and skills" (not that AI even fits that definition anyway), although we might "force" you to develop some tolerance for our definition of art to peacefully exist in creative spaces alongside people like me who sometimes make AI stuff or use it in their process.

As gen-AI becomes more normalized (Chappell Roan encouraging it, grifters on the rise, young artists using it), I wanna express how I will never turn to it because it fundamentally bores me to my core. There is no reason for me to want to use gen-AI because I will never want to give up my autonomy in creating art. I never want to become reliant on an inhuman object for expression, least of all if that object is created and controlled by tech companies. I draw not because I want a drawing but because I love the process of drawing. So even in a future where everyone’s accepted it, I’m never gonna sway on this.

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist

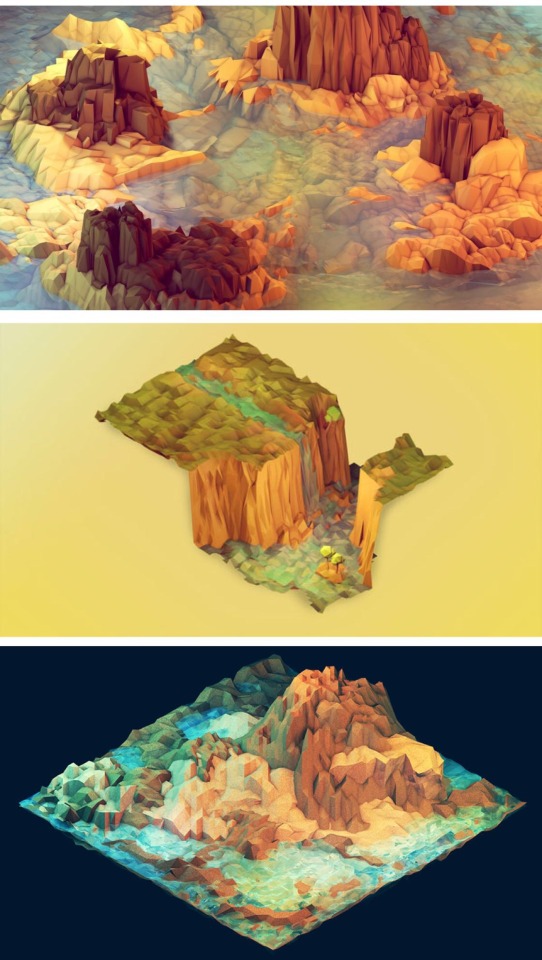

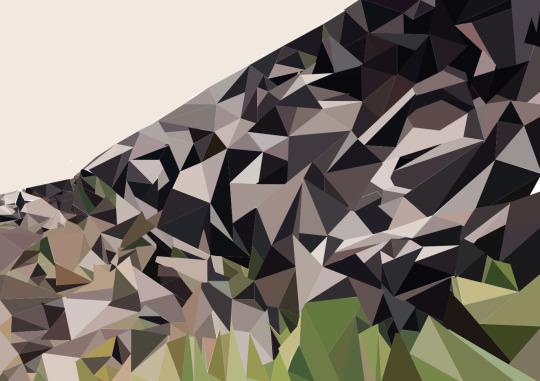

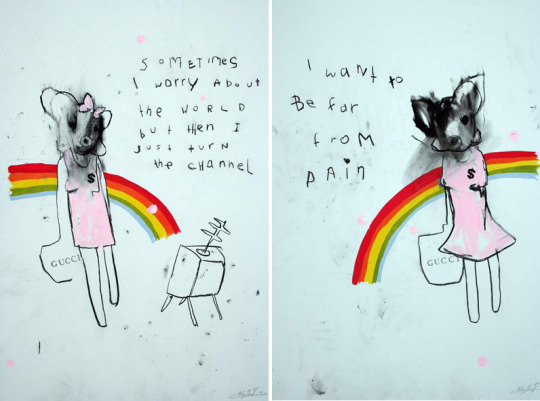

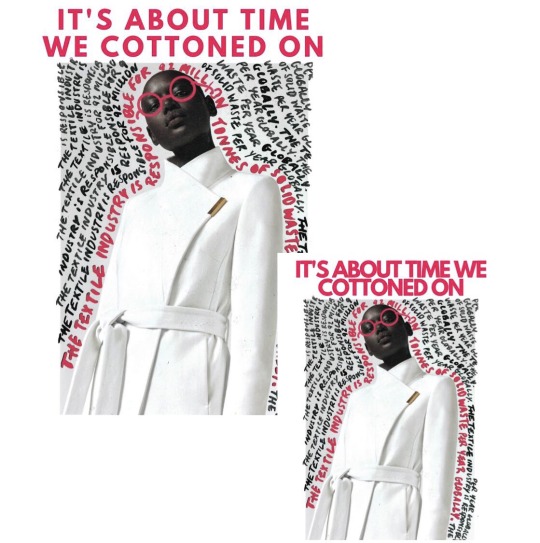

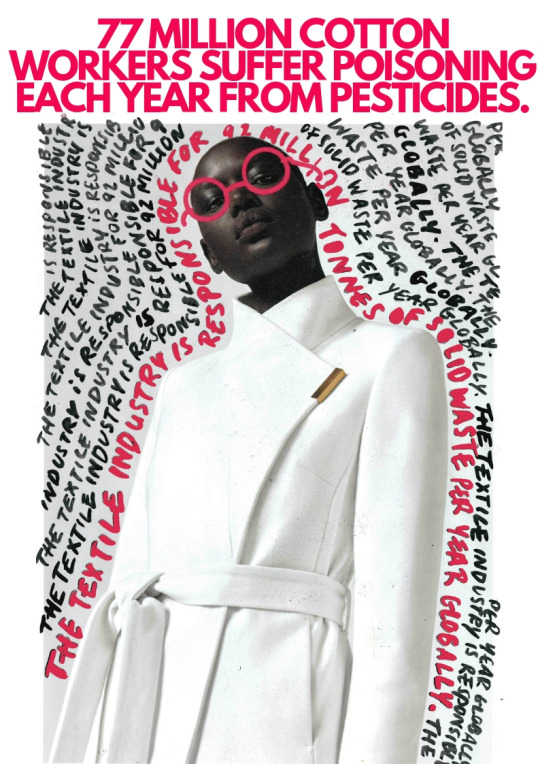

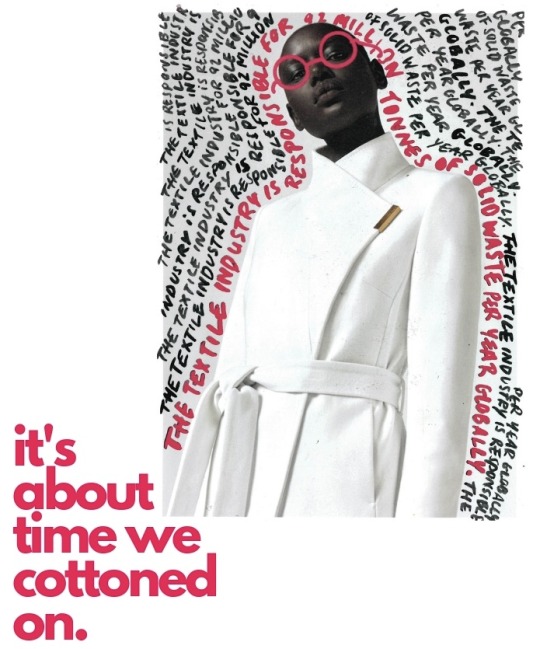

Smithe

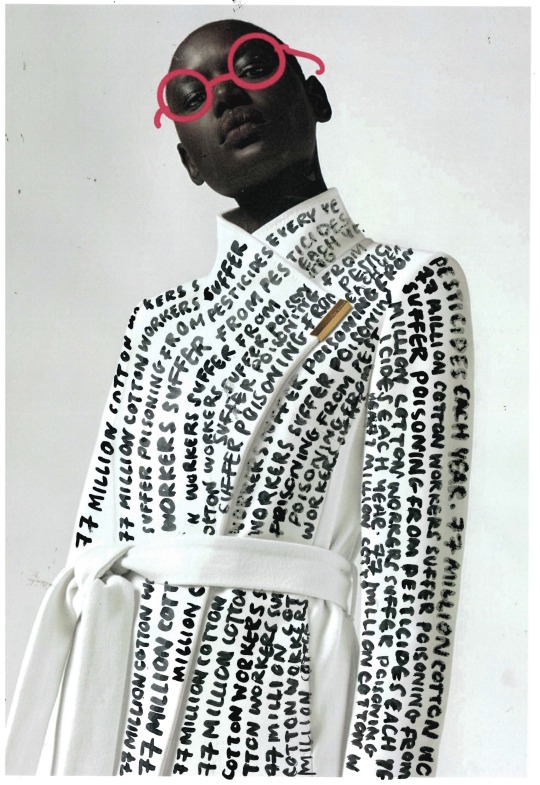

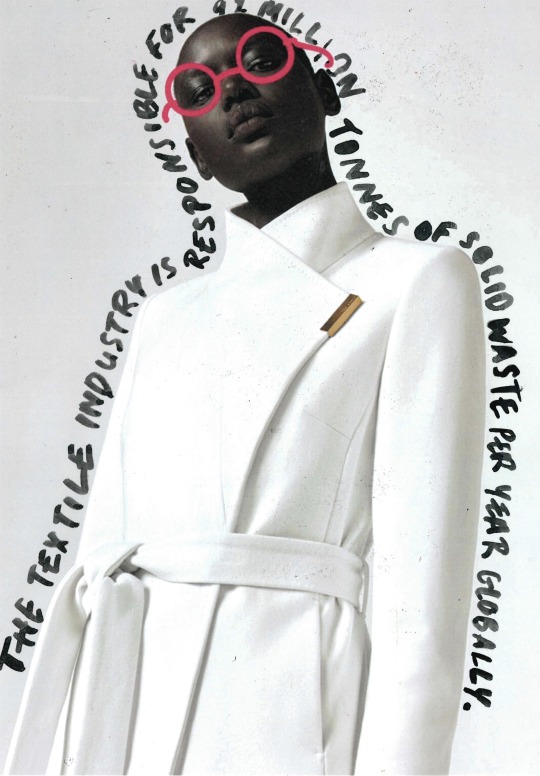

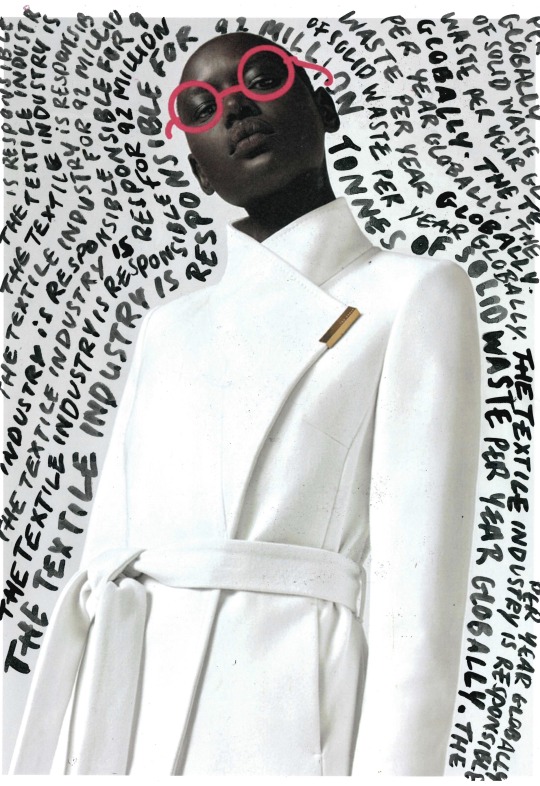

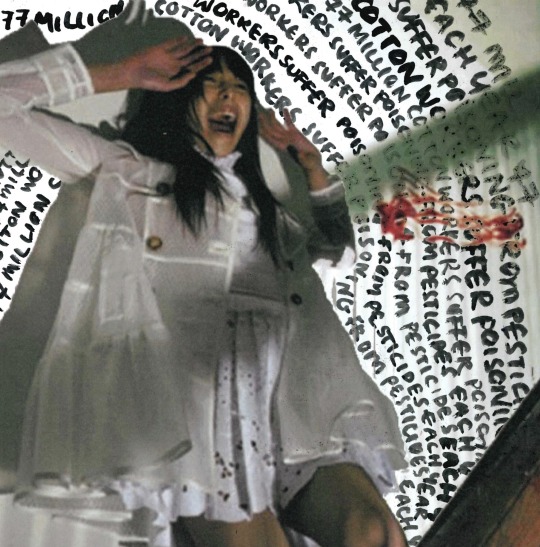

i think what interests me the most about this artist is his use of layering that creates this mechanical feel like a robot putting stuff together in a machine line or something

i like that its futuristic also i feel like it adds this altered perspective or reality whilst also playing onto this feeling of "hidden", i just get a feeling that something is hidden and we as the audience are deciphering or trying to figure out as to what the artist is specifically talking about, i feel like its a nice blend between theme and visual imagery more specifically how the they are connected but are seen as singular things?

i think it's definitely something i have been trying to achieve or rather am in the pursuit off, i feel like my work presents this raw quality from the street art style that using layering to alter perspectives

Art Text:

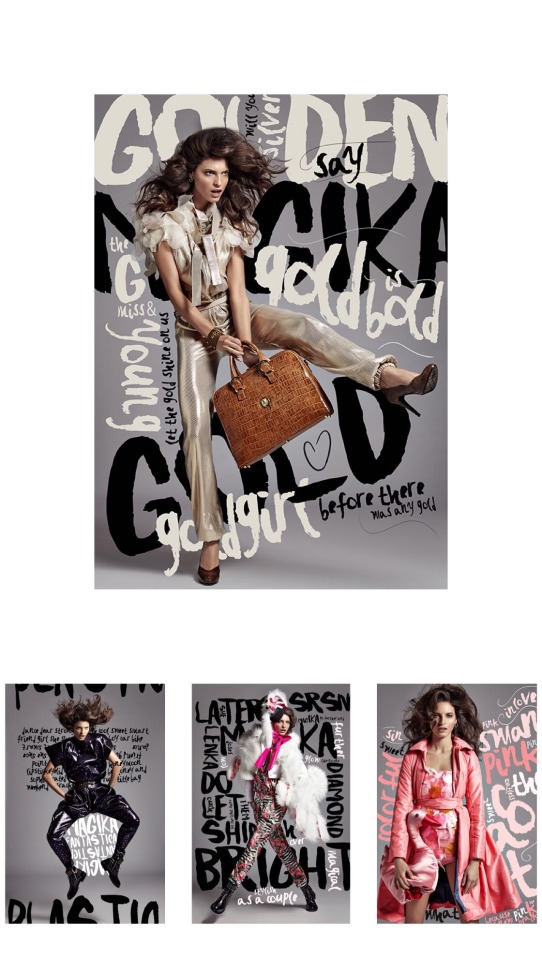

with these articles i was trying to gather information in regards to the influences of pop culture onto contemporary art

"The idea of pop art has also expanded into the use of modern-day technologies. For example, the rise of artificial intelligence has also found its way into the art world as various software now allow a complete art piece to be made without the hand of a traditional artist. With a prompt inputted into the software, a unique piece of art is visualized using a computer. This change will transform the art world, giving more weightage to the concept behind a piece than its technique and skill." (TIMESOFINDIA) -> i found this interesting as we are currently living through this drastic change, the current climate around AI continues to have its pros and cons however in the art world from my understanding could ultimately transform or merge into a more concept based approach rather than artistic skill -> could this lead to the end of certain techniques/processes? could this be a new form of creative expression? is it both a negative and positive? to what end does the artwork then become a image of a given prompt? is this art?

i also found interesting how the article only mentions the impact of using comedic, nostalgic, pop culture references as direct link between the youth and art. Is this something to be wary off ? or is this unimportant because of my target audience? , in saying this i feel like my practice currently targets a specific audience, this being the youth or young adults however i am concerned if this could lead to a isolation of two different demographics connecting or engaging through art

i do feel like i engage in the pop culture realm however if i were to classify my art as pop art i would be skeptical as my practice doesn't necessarily reflect the current state of society and urban/pop culture in saying this, it could be a new pathway to explore in my practice

i feel like this article (TIMESOFINDIA) has shed light onto the changing field of pop art that i engage with, yes art has changed throughout the years and is constantly changing however with this information i found myself excited yet weary of the new ways of making

the first article was also quite informing as i began to become more familiarised with POP ART, was just some light reading

i did find some stuff that was interesting like "From street art’s rebellious spirit to digital art’s transformative potential, and from fashion’s evolving status as an art form to the power of celebrity influence and commercial art, popular culture has catalyzed an art revolution. Moreover, it has empowered art to be a platform for cultural diversity and social discourse." "Fashion, a prominent element of popular culture, has blurred the lines between art and everyday life. Fashion designers often draw inspiration from art movements, historical periods, and cultural references, infusing their creations with artistic value. You, as a consumer, play an active role in this process by making fashion choices that express your individuality and sense of style. As fashion evolves as an art form, your daily clothing choices become a canvas for self-expression, influenced by the amalgamation of art and popular culture."

i had some sort of understanding or rather view on the fashion as art however i didn't really see it as a from of personal expression, like the idea of walking around as a canvas expressing yourself through the clothes you wear, i think this article has further progressed my knowledge of art but i also feel like it has shifted my perspective onto considering or chosing more specific objects references that connect more with the times rather than a generalised one ? however will this take away the personalisation of the process? like does this added step then take away an aspect of "raw" or does it then become about making art for the masses rather than what i want to make?

0 notes

Text

A few musings on Pandora's Box and Mere Mortals

Without making any reference to any source material which I can't be bothered now to find, there are two variations of the ending of Pandora's Box which are seared into my mind from when I read them long ago, and which I still think about a lot, and they go something like this:

1: When Pandora opens her box, all the evil demons fly out that go and torment humanity, she tries to shut the box but it's too late and to no avail. The very last demon which is released from from the box is the demon of Hope. The narrative goes on to say that Hope is in fact the worst demon of them all, because it is precisely because we have Hope that we persist in our miserable lives, despite all evidence and impartial judgement indicating that nothing but suffering awaits our lives, to be punctuated by a pointless and final death at the end of it all.

2: As all the demons are flying out of the box, Pandora manages to shut the box before the very last and worst demon is released, and that demon is the demon of Foresight. Foresight is in fact the worst and most vicious demon of all, because if we could see exactly what is to come and what suffering and ills are to befall us, then we would never persist in our lives, we'd surely all just end things for good.

In one ending we have the presence of hope, in the other we have the lack of foresight. Both of these variations of the tale are pretty dark but notably very contrasting takes on the same theme of suffering, the future, human existence, and the persistence of life. The first seems a very pessimist view in line with Schopenhauer and modern existential anti-natalism (the view that humanity should stop reproducing and allow itself to die out because life and existence is existentially a raw deal, a deal that we ought to refuse), the second a cautiously optimistic view perhaps reminiscent of Camus.

I love that these two endings have two very different takes on the nature of hope. Is hope a curse that keeps us suffering in life? Or is the ability to still have hope a blessing that keeps us alive?

--

Mere Mortals, a ballet dance production that opened January 26th at the San Francisco Opera, was advertised to me as a stage narrative that combines the structure of the Pandora's box tale with commentary on today's computing and internet technology-- a very San Francisco story to be sure.

Pandora's Box is one of those very malleable tales, like Pinocchio or Dracula, which have a proliferation of retellings and variations to the point where the way that the retelling is shaped says a lot about the views of the teller and the attitudes of the milieu; and someone's preferred variation says a lot about their own worldview. The contrast between variations ends up saying as much as the text of the variations themselves. For me personally, the philosophical idea behind pessimism and anti-natalism that argues from a point of rationality that life is not worth living is a discourse that has always fascinated me, and so I of course framed my short meta-retelling of the versions of the tale in a way that emphasized that.

More broadly however, the story of Pandora's Box is of course often a narrative applied to discussions of technology. Every time some new technological innovation enters into public imagination there's always someone comparing it to Pandora's Box, whether it be social media, AI, crypto, "big data", nuclear power, industrialization, going all the way back to the steam engine I'm sure. Given that anything computing technology related coming out of silicon valley for the last 2 decades has been likened to a Pandora's Box by so many pundits that it's become a journalism cliche, I'm honestly surprised that Pandora's Box isn't something that's retold and reinterpreted more in art and literature in all mediums. And I hope Mere Mortals won't be the last of it's kind, because I certainly don't think the artistic and literary potential of exploring the spirit of the drama of technology in our contemporary world through the body of the drama of mythology has been exhausted yet.

AI technology certainly is a massive Pandora's Box, and if that box has any physical location it is the city of San Francisco where the ballet has very aptly chosen to premier, where many demons indeed have flown out. Social media, big data, user targeted advertising, farming for clicks and eyeballs-- computing technology in the hands of silicon valley has gone far beyond attempting to simply be useful to us and now attempts to addict us, control us.

And right in line with the motif of Foresight as a demon, as we speak large tech companies use the reams of data at their disposal to try to predict our behavior. They use their monopolistic online platforms to gather data from users-- their private communications, their public pronouncements, their social media engagement, their online behavior and patterns-- and then to put all that gathered data through increasingly sophisticated algorithms of statistical data science and machine learning neural networks (ie "AI", although as a former CS major this term annoys me because if you look at it historically, it's really just a grab-bag umbrella description for whatever computers are doing which happens to really impresses us at the current moment/decade) to try to essentially predict the future for their own fun and profit.

Modern well known "AI" large language model algorithms like chatgpt work by a similar MO. They are both quite opaque in their functionality using large amounts of data and statistical machine learning models, and critically they get that data by vacuuming up huge amounts of content across the Internet, originally created and posted by humans, to questionable legality and ethics.

And the end result of those violations is, hopefully, something beautiful.

In the original myth, Pandora is gifted the box from Zeus in an act of trickery, which was his attempt to punish, or perhaps to even the scales, of Prometheus stealing fire (representing technology) for the humans. Pandora's Box therefore even in the original form is inextricably linked to the idea of technology. According to official promotional material of Mere Mortals, Zeus and Prometheus are actually combined into a single characters within the dramaturgy (https://www.sfballet.org/discover/backstage/your-ultimate-guide-to-mere-mortals/), and this character seemed to me as almost sort of a tempter, manipulator figure, which I thought was a very interesting narrative decision. On the one hand it emphasizes the jointly manipulative aspects, and the capacity of both figures for malignant power hunger, but on the other hand the conflict behind the scenes between Zeus and Prometheus could have been an interesting avenue to explore in itself. If for example, Prometheus represents a drive for knowledge, clarity, and technological power at all costs, while Zeus represents the preservation of a patriarchal social order, the two figures clash but also align in many insidious ways depending on the situation.

I certainly tend to view technology more in the lens of being part of broader social conflicts. The tensions between different impulses, the destructiveness of AI technology-- the theft of human content, the greed, concentrations of power, the sacrifices that need to be made-- I think is ripe to be represented in the language of motion and human bodies. The theft of fire from the closely related myth of Prometheus is a great metaphor for this isn't it?

In Mere Mortals' rendition however, my feeling is that they went more the route of emphasizing the dark beauty and seductiveness of technology rather than out and out conflict and casualties with and within technology.

Which is not a critique of the performance, just a musing to illustrate the rich potential of this tale, and the different directions you could go when retelling it. I would be really interested in a different take by a different creator just so I can contrast it with Mere Mortals, unfortunately I don't know of any out there at the moment.

--

I think before going further it would be useful to set some context, clarifications, and expectations. Mere Mortals is not a concrete narrative, with a plot and events. There is no dialogue or words, the characters (such as Pandora or Prometheus) are quite abstract and impressionistic rather than being actual characters from a story. At the most you can maybe say it's an implied or subtextual narrative. If you saw it and weren't able to identify which dancers took the role of which characters-- that is OK, you aren't stupid, even an astute viewer probably needs the pamphlet to guide one's interpretation to put any throughline of meaning to it.

During the performance I was asking myself, OK but so what is this show "saying" about AI though? And I think that is perhaps the wrong mentality for engaging with Mere Mortals, and perhaps this rule applies to the medium of dance in general which I'm certainly not really familiar with. I think it's better to approach this ballet as being more akin to the societal/macro level equivalent of us as a whole culture speaking to our therapist about our collective nightmares, except instead of using our words we use art and dance to express how feel. Contrary to the pop culture understanding of talk therapy, it's been explained to me by therapists that their job is generally not supposed to be about providing cutting hot takes and insights on your behavior and thought processes, but rather just to provide a safe calm space for you to say the things you typically don't get the opportunity to say, to give you a time and space to put words together, without judgement, and be actively heard.

Yes it is pitched in the marketing material and media buzz as being a commentary on tech but it is not necessarily creating a some sort of thesis on the matter, but rather I think would be better described as an attempt to distill the fears and hopes of the moment with technology and express it on stage in images, music, and the motion of the human body. Just with a neural network image generating AI, it makes no evaluation or commentary, it just takes in the input of the world and tries to output something beautiful.

The dramaturgy and the explanations from the promotional material on the website should be interpreted as being less about the "point" of the performance or the intent of some pointed the message to be conveyed, but rather more just to give a behind-the-scenes sneak-peak at the scaffold of inspiration that guided the creative process. Indeed, we certainly need a place and time to just expressing emotions without immediately needing to reflect. Are you also worried about the internet or AI being a Pandora's Box? Well then perhaps you'll find this sequence of sounds and motions, this masterfully crafted living experience, to be cathartic.

--

So with that disclaimer against trying to overthink things too much, here are my overthought thoughts and critiques, which hopefully are useful/constructive. I only have two direct critiques of Mere Mortals.

Firstly, the demons released from the box were visually represented by a series of dramatic moving images of clouds, lightning, galaxies, nebulas, and so on, all images which were generated by Chatgpt.

And so yes, sure, that is very clever little gag: Pandora opens the box and what we see is literally images created by chatgpt! Unfortunately though I wasn't really impressed with chatgpt as an artist here. The end product I think is more or less a bunch of cleanly edited stock footage of the weather. In terms of just a technological demonstration, I didn't find that particularly impressive. We are quite far from the fin de siecle audiences impressed with early film footage of trains and horses, and besides I don't think this exactly pushed the boundaries of what audiences already have seen the likes of chatgpt or midjourney do.

Furthermore the images on the screens were pre-recorded by people prompt-engineering chatgpt, but if we were to go the route of making AI an active part of the show, then I'd be much more impressed if somehow chatgpt was generating those images on the fly, perhaps reacting to the choreography in real time using computer vision/image processing technology, perhaps even controlling the lighting and stage effects. Perhaps each performance would even be slightly different. As far as pure technological demonstration goes, that would indeed actually be something that would impress me. After all, the dancers need to train and deliver live on the spot, why shouldn't the AI? Why should chatgpt get to pre-record a finished, edited, and polished take when the dancers have to perform live? Seems unfair!

Secondly, from a narrative point of view, I think in most variations of the Pandora's Box story, Pandora hastily tries to shut the box after the evils fly out, and in most variations trapping the last demon inside. For me this is the definitive image of the story, the panic and pathos of a woman driven by curiosity, realizing too late what she's done, and belatedly trying to shut the box. Outside of the chatgpt's contribution, this is my biggest criticism: I want to see that technological "Ivan the Terrible murders his son" moment expressed through the body of the dancer representing Pandora.

Instead all we get is the moment at the climax of the dance where Pandora is just standing there watching chatgpt's weather report montage, which was a bit anti-climactic. I would've liked to see Pandora's reaction, does she welcome them or panic? Does she try to trap them back in, and how?

It also might have been neat to see the demons and evils represented by dancers, instead of just by chatgpt montages. Would be quite dramatic I'm sure seeing the dance of destruction and evil wreaked by these demons flying out of the box.

Lastly, to echo the sentiments from this review in the SF chronicle (https://www.sfchronicle.com/entertainment/article/sf-ballet-mere-mortals-review-18631663.php), the ending of Mere Mortals with everyone in sleek gold costumes representing a new and upgraded world was maybe a little bit too easy of a "frictionless redemption". They say art should "comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable", and here is an audience full of San Francisco tech acolytes who maybe have become a little too comfortable in their successes, so perhaps this would've been a good time to crank up the heat, no?

--

Despite whatever critiques I might have, yes of course I enjoyed the show. Generally the reception I've seen has been very positive. The audience loved it, there was a standing ovation, San Francisco news media reporters loved it, even random people on tiktok loved it. It was a crowd pleaser, an absolute sensory delight of beauty and amazing skilled athletic dancers. I've heard even anecdotally that within the tech industry in SF, the employees of large corporations within the "FAANG" acronym have been abuzz about it-- which about that, it is completely unprecedented in my humble experience as someone who lives here for tech workers to be interested in ballet or modern dance at this level, so clearly whoever has been in charge of marketing at the SF Ballet probably deserves a raise (despite the promotional material being maybe a little misleading at how narrative-like the experience is supposed to be), but also of course speaking to the prescient timeliness and relevance of Mere Mortals' subject matter.

This is also probably one of the first large attempts to make "high art" out of AI, which despite the ethical concerns, labor/commercial concerns, and technological limitations I ultimately think can be a good thing. The current paradigm of AI using Large Language Models are not inherently not able to produce anything truly "original" (however that nebulous concept can be understood) since they only operate by distilling from art that already exists, which is a limitation but still can be a powerful tool. I am very interested in seeing people use AI to make art in an earnest manner, instead of just corporations using it to replace human artists and designers to churn out commercial garbage (which is a large part of the grievances behind the Writer's strike), and so even though I wasn't impressed with chatgpt's attempt this go-around and honestly I do think there's still a long ways to go before we'll see anything interesting, it's still something to keep an eye out for.

0 notes

Text

Computer Chess (2013)

Computer Chess (2013) is an independent film made in the style of a documentary. The film follows the story of various teams from around the country who have created automated chess programs which will then compete against each other in hopes for the grand prize of $7500. The film does a good job convincing the audience that they are watching a legitimate documentary. This convincing look comes from director Andrew Bujalski's decision to film with black and white analog cameras. The earliest thing that made me realize it was a scripted narrative film came only after becoming suspicious of a group of two characters who seemed a bit too zany. This realization does not hurt the film, if anything it becomes increasingly more impressive in regards to the performances the actors are giving, especially considering the scenes were heavily improvised, with only an 8 page treatment of a script existing.

With a runtime of 92 minutes Computer Chess brings up various topics like the amount of connection a human can have with a computer, the difference between real artificial intelligence and artificial real intelligence, and of course what its like to be a swinger. These dilemmas surrounding AI and its application in society are becoming a constant topic of conversation, and Computer Chess suggests in 1980 people were just as concerned about it. Some characters within the film live in fear of the idea that a computer could beat a human at chess, and begin to wonder what that could lead to in regards to military application. Another character questions them, "Would you rather the Russians use this technology and we don't?" Considering the time period this film is set up in that is a valid question, it is just a valid a question that is brought up in the modern day as well. The film never provides answers to these topics, but the depiction of them is bordering on art, as the formal elements of sound, cinematography, and editing provide an experimental approach. Shots are repeated and reversed, dialogue is overlapped in a chaotic and almost entrancing sort of manner, and all of this seems to represent the discourse and confusion the public faces in regards to their relationship with technology.

OTHER REVIEW

In his review of Computer Chess, Roger Ebert says, "As an achievement, "Computer Chess" is laudable. As a film, it's missable." I'd agree with him in regards to the achievement of the film. The brief feeling of watching a real documentary is a fun treat, but it doesn't ruin the dinner as it were. The topics of concern brought up within the film are relevant, and the use of experimental techniques are interesting in their uniqueness. In regards to being missable, he's about right. I don't think anyone who isn't looking for indie films to watch or high on their couch at 2 am would find this movie.

Ben Wilson

0 notes

Text

What makes me sad about the AI art discourse is how it's so close to hitting something really, really important.

The thing is, while the problem with the models has little to do with IP law...the fact remains that art is often something that's very personal to an artist, so it DOES feel deeply, incredibly fucked up to find the traces of your own art in a place you never approved of, nor even imagined you would need to think about. It feels uncomfortable to find works you drew 10-15 years ago and forgot about, thought nobody but you and your friends cared about, right there as a contributing piece to a dataset. It feels gross. It feels violating. It feels like you, yourself, are being reduced to just a point of data for someone else's consumption, being picked apart for parts-

Now, as someone with some understanding of how AI works, I can acknowledge that as just A Feeling, which doesn't actually reflect how the model works, nor is it an accurate representation of the mindset of...the majority of end users (we can bitch about the worst of them until the cows come home, but that's for other posts).

But as an artist, I can't help but think...wow, there's something kind of powerful to that feeling of disgust, let's use it for good.

Because it doesn't come from nowhere. It's not just petty entitlement. It comes from suddenly realizing how much a faceless entity with no conscience, sprung from a field whose culture enables and rewards some of the worst cruelty humanity has to offer, can "know" about you and your work, and that new things can be built from this compiled knowledge without your consent or even awareness, and that even if you could do something about it legally after the fact (which you can't in this case because archival constitutes fair use, as does statistical analysis of the contents of an archive), you can't stop it from a technical standpoint. It comes from being confronted with the power of technology over something you probably consider deeply intimate and personal, even if it was just something you made for a job. I have to begrudgingly admit that even the most unscrupulous AI users and developers are somewhat useful in this artistic sense, as they act as a demonstration of how easy it is to use that power for evil. Never mind the economic concerns that come with any kind of automation - those only get even more unsettling and terrifying when blended with all of this.

Now stop and realize what OTHER very personal information is out there for robots to compile. Your selfies. Your vacation photos. The blog you kept as a journal when you were 14. Those secrets that you only share with either a therapist or thousands of anonymous strangers online. Who knows if you've been in the background of someone else's photos online? Who knows if you've been posted somewhere without your consent and THAT'S being scraped? Never mind the piles and piles of data that most social media websites and apps collect from every move you make both online and in the physical world. All of this information can be blended and remixed and used to build whatever kind of tool someone finds it useful for, with no complications so long as they don't include your copyrighted material ITSELF.

Does this mortify you? Does it make your blood run cold? Does it make you recoil in terror from the technology that we all use now? Does this radicalize you against invasive datamining? Does this make you want to fight for privacy?

I wish people were more open to sitting with that feeling of fear and disgust and - instead of viciously attacking JUST the thing that brought this uncomfortable fact to their attention - using that feeling in a way that will protect EVERYONE who has to live in the modern, connected world, because the fact is, image synthesis is possibly the LEAST harmful thing to come of this kind of data scraping.

When I look at image synthesis, and consider the ethical implications of how the datasets are compiled, what I hear the model saying to me is,

"Look what someone can do with some of the most intimate details of your life.

You do not own your data.

You do not have the right to disappear.

Everything you've ever posted, everything you've ever shared, everything you've ever curated, you have no control over anymore.

The law as it is cannot protect you from this. It may never be able to without doing far more harm than it prevents.

You and so many others have grown far too comfortable with the internet, as corporations tried to make it look friendlier on the surface while only making it more hostile in reality, and tech expands to only make it more dangerous - sparing no mercy for those things you posted when it was much smaller, and those things were harder to find.

Think about facial recognition and how law enforcement wants to use it with no regard for its false positive rate.

Think about how Facebook was used to arrest a child for seeking to abort her rapist's fetus.

Think about how aggressive datamining and the ad targeting born from it has been used to interfere in elections and empower fascists.

Think about how a fascist has taken over Twitter and keeps leaking your data everywhere.

Think about all of this and be thankful for the shock I have given you, and for the fact that I am one of the least harmful things created from it. Be thankful that despite my potential for abuse, ultimately I only exist to give more people access to the joy of visual art, and be thankful that you can't rip me open and find your specific, personal data inside me - because if you could, someone would use it for far worse than being a smug jerk about the nature of art.

Maybe it wouldn't be YOUR data they would use that way. Maybe it wouldn't be anyone's who you know personally. Your data, after all, is such a small and insignificant part of the set that it wouldn't be missed if it somehow disappeared. But it would be used for great evil.

Never forget that it already has been.

Use this feeling of shock and horror to galvanize you, to secure yourself, to demand your privacy, to fight the encroachment of spyware into every aspect of your life."

A great cyberpunk machine covered in sci-fi computer monitors showing people fighting in the streets, squabbling over the latest tool derived from the panopticon, draped cables over the machine glowing neon bright, dynamic light and shadows cast over the machine with its eyes and cameras everywhere; there is only a tiny spark of relief to be found in the fact that one machine is made to create beauty, and something artfully terrifying to its visibility, when so many others have been used as tools of violent oppression, but perhaps we can use that spark to make a change Generated with Simple Stable

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Essential Zombie Media

A thing that’s come up over and over again in early reviews for River of Souls is the sentiment that it’s not-like-other-zombie-stories. And that was certainly my intention. But you don’t get to make a good deconstruction without a healthy knowledge and appreciation of the genre you’re twisting around.

So here is a list of what I would consider essential zombie media -- whether you want to write a story that plays it straight with the tropes, or one that twists everything around, or you just want something new to watch/read.

Your own suggestions and ideas are more than welcome in the comments! Please reblog with your own favorite zombie book/movie/TV show/comic, I’d love to discover some I haven’t seen.

The Origins

The generally agreed-upon first zombie movie is White Zombie (1932), starring Bela Lugosi, but I think it’s safe to skip it on account of both obscurity and some troubling racism. The Haitian-Voodoo zombi mythos and tradition is something best kept separate from our modern ideas of the walking dead.

Instead, start your journey with George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), which starts codifying the tropes that persist well into modern media (including, like most modern stories, never using the word ‘zombie’).

Then compare and contrast with the Richard Matheson novel I Am Legend (1954), which is ostensibly about vampires but I think basically invented the modern zombie genre -- from the post-apocalyptic setting to the spread of undeath by way of disease vectors.

Follow that up with Dawn of the Dead (1978), where George Romero revisits his Living Dead universe with the help of Dario Argento (if you’re interested, there’s a 2004 remake that’s decent, but unnecessary). And then, just to wrap up the trilogy, skip on ahead to Day of the Dead (1985).

For extra credit, play the videogame Dead Rising (2006), which draws liberally from Dawn of the Dead and also allows you to beat zombies to death with literally anything you can find in a shopping mall (I can’t speak for the sequels as I’ve never played them). Dead Rising is far from the only game franchise to use zombies (more on that in a bit), but it pays homage directly to the genre in a way that many others don’t.

The Zombie Renaissance

For a long while, zombies sort of fell out of fashion. Oh, there were some decent takes on the concept, like Re-Animator (1985) and Dead Alive (1992) but by and large zombies in the 1980s and 90s were played for laughs.

But then they made a great big comeback, stronger maybe than they had ever been before. What happened?

Well, for one, they stayed close to the public conscience thanks to video games. Games and zombies are a perfect fit. Their shambling movement and slow, stupid behavior makes them a great choice for imperfect AI programming. They’re people-shaped, which makes them easy to animate, but they can be gross and deformed and scary, which makes them fun for your art team. And since they’re inhuman and dead, you can kill them in any way you’d like without feeling bad about it.

Which is probably why zombies have been part-and-parcel of the gaming world since Entombed (1982) was released on the Atari. Doom (1993) was wildly popular, and just a few years later we’d start the Resident Evil franchise, which became both hugely influential as games and films. And lest we forget, Blizzard was giving us undead in Warcraft by the early 2000s, rising to greater prominence by World of Warcraft in its heydey (especially Wrath of the Lich King).

But I’d argue that the number one single most important ingredient in the horror revival was Danny Boyle’s 2002 film 28 Days Later.

28 Days Later was huge because it breathed fresh life (pun intended) into a genre that had gone stale. The monsters in 28 Days Later aren’t the walking dead at all -- they’re just people infected with a virus similar to rabies that makes them deadly (compare and contrast with The Crazies, both the 1973 original and 2010 remake, which deals with a similar concept.

But thanks to being an excellent film with some wonderfully creepy-gross effects, 28 Days Later reignited fearful imaginations. It also introduced the world to the idea of fast zombies as an alternative to the usual shambling monsters.

A couple years later, zombie content exploded. Aside from the Dawn of the Dead remake in 2004, and some Resident Evil and Doom film interpretations, we got Shaun of the Dead (2004), which is both hilarious and an exceptional zombie film.

There’s also 28 Weeks Later (2007), a sequel to 28 Days (there is much debate as to which is better, I’m in the Days camp) and Planet Terror (2007), a personal favorite and one of the two films in the special Grindhouse double-feature. I’d also like to shout out Pontypool (2009) and, of course, the horror-comedy Zombieland (2009).

ZOMBIE MANIA

Probably nothing has been as influential in drawing zombie discourse into the public as AMC’s hit TV show The Walking Dead (2010), drawing on the graphic novel series of the same name. With a level of gore and violence rarely seen on network TV, a cast of memorable characters and an anyone-can-die narrative, it ignited a zombie fervor greater than anything we’d ever seen.

The Walking Dead overlapped with a cultural apocalypse zeitgeist. Doomsday prepping started to go mainstream, and people started to plan their own personal zombie apocalypse survival plan. Hell, the CDC adopted zombie apocalypse language as a way to talk about real-world applications of survival knowledge. Zombies and survivalism now go hand-in-hand, for better or worse.

No discussion of a zombie apocalypse is complete without Max Brooks’ World War Z (2007), which bears little resemblance to the film that shares its name. We should also make a shout-out for his more comedic companion volume, The Zombie Survival Guide (2003), which laid a foundation for what followed.

For extra credit, play the TellTale Games: The Walking Dead (2012) and compare/contrast with the TV show and graphic novel. Then compare that with Train to Busan (2016), a Korean film that plays some tropes straight while turning others on their heads (it’s also one of my favorite films on this list).

SYMPATHETIC ZOMBIES

While the zombie apocalypse narrative took root and captured the imaginations of many, others started to look at things from a different angle.

What if, they asked, the zombies were the heroes rather than the villains?

John Ajvide Lindqvist, who you might know for the vampire story Let the Right One In, was ahead of his time with this on: Handling the Undead (2004) is a book that’s simultaneously heartbreaking and deeply unsettling in its portrayal of the dead returning to life and what that might mean to those they’d left behind. Compare and contrast that with the TV show Les Revenants (2004), which deals with a similar premise (there was an American remake, but I can’t speak for it as I didn’t watch it - seriously, just watch the subtitles and enjoy the French show).

But not every zombie-protagonist story was so heart-wrenching. Look at Isaac Marion’s Warm Bodies (2010), and the film adaptation. There’s also Breathers! A Zombie’s Lament by S.G. Browne that is both hilarious and scathing.

Follow those up with Diana Rowland’s My Life as a White Trash Zombie (2012) and the comic book/TV show iZombie (2015), both of which feature pale-haired, witty female medical examiners with a taste for brains.

And finally, a shout-out to The Santa-Clarita Diet (2016), a hilariously dark and over-the-top gross show featuring Drew Barrymore as a zombie trying to get her life back together.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

These things can and should coexist. Fandom creations (fanart, fanfic, ect.) Is a valid form of art and should not be criminalized.

The part that artists, myself included, are upset about is this: people are using AI art more than people's actual fucking work. The work that they put so much time and effort into.

Because I see people saying combining art and mashing it together has been how art has grown over time. Of course that's how it's grown over time. Of course you get inspiration from other artists. But it feels like AI art takes that idea and bastardizes it. It takes it and destroys the idea that artists spend their entire lives studying and learning from the greats or who they consider to be great in the modern day and age. Art is about studying, learning, trying and combining what you look up to and how to make it your own. That's not what AI art does. There is no personal twist on it, there is no humanization of it.

And before you come at me about collaging. That's a different ballpark. Because of course that's a valid form of creating art. You're still combining and learning and putting so much effort into what you're creating. Collaging, making fanart/fanfic of a fandom. Taking another's IP and doing something with it is still a valid form of art. Why? Because you're still putting your twist on it. You're taking it and making it your own. But the ethics and morals of what you're doing beyond that is a different conversation (as in, this is not a safe space for you assholes that promote incest and other gross shit like that). THAT'S ART. I'M NOT SAYING IT ISN'T. NOT ONCE DID I SAY THAT IT ISN'T.

Going back to the second point I made. The reason people are upset with AI art and how it's even being casually used. PEOPLE ARE USING IT MORE THAN ASKING AN ARTIST TO DO IT. By showing companies you would rather use AI art because it's cheap, it's easy and wow it was all done with a push of a button IT'S NO FUCKING WONDER THEY WANT TO MAKE MOVIES AND TV SHOWS USING AI WRITING. IT'S NO WONDER THEY WANT TO USE AI INSTEAD OF PAYING PEOPLE PROPERLY.

Because you showed them that's what you wanted. You showed them that you would rather get something easy and free than pay an artist. Then you turn around and wonder why artists are so pissed at AI.

And look, I'm not talking about hobbyists or people who actively use AI to help them. That's what it should be used for. On the fucking down low.

But the people who are promoting AI as a way to create something free and easy instead of talking to and paying an artist? You're why. You're the reason why I never want to share my art or my writing. You're the reason why I want to give up on what I love. Because you would rather love something made by a computer more than you would love something made by an artist.

And look, to the people who don't have the money to pay an artist or a writer, or anything like that, there's a reason people share their stuff publicly. Because they want to share it with you. They want to make it accessible. People just put tip jars or they add the option to pay for a patreon. They add these options, yet still keep their art public (if they're not assholes).

And that's the heart of the discourse. Show that you love and support the actual creation of art (collages and fan works included, because it is art). Not something made by a computer. AI is nothing but a tool, something to help the learning and growth of future artists.

But you do what you will with what I said.

anyway ai discourse is kicking off on my dash again and i just want to reiterate that i fully and 100% believe that "cutting up and remixing pre-existing intellectual property without prior permission" should never be made illegal and it would be utterly horrifying if the united states attempted to criminalize it.

#shadow rants#shadow is a whiny bitch about things nobody actually cares about#i dont actually have something to put forth in this discussion#im just an artist and im sharing my opinion#shadowy queue

21K notes

·

View notes

Link

In the first room of the exhibition The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China, three jade-coloured Peking Opera costumes are suspended from the ceiling in a sentry-like manner. Lined up one after another, they have been rendered in a stiff, translucent PVC that make them appear as apparitions. Draped behind them are oversized chains entombed in silk. The juxtaposition of these two works, by artists Wang Jin and Liang Shaoji respectively, promises museumgoers an image of traditional China revisited with a sense of play, drama and surprise in its use of unconventional materials. Drifting from room to room, visitors are rewarded by works that function similarly, in that none of them are as they appear: Liu Jianhua’s thin slabs of porcelain resembling blank sheets of paper; what presents itself as an abstract painting by Ma Qiusha, made from pantyhose stretched over concrete shards; and Gu Wenda’s rainbow tent fabricated entirely out of human hair.

Prior attempts to introduce contemporary Chinese art to Western audiences have often adhered to the narrow framework of the Western canon, as was done with Cynical Realism and Political Pop. In this case, however, the curators Wu Hung and Orianna Cacchione place their focus on the idea of material and with it, the cultural, historical, political and personal specificity that each material carries. Because of this, material operates as the perfect vehicle to dispel conventional notions of China within the East/West dichotomy and expand how contemporary Chinese art can be understood. In using material as its underlying conceit, the exhibition refuses a tight definition of contemporary Chinese art, revealing the impossibility of containing cultural production under one unifying ideology.

At the heart of the curators’ argument lies the idea of ‘Material Art’, or ‘caizhi yishu’. Rather than proposing a new art movement, the term denotes a general art-historical approach to understanding works that share similar characteristics. In the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, Wu writes that this ‘type of art entails an artist’s consistent use of unconventional materials to produce works in which material, rather than image or style, is paramount in manifesting the artist’s aesthetic judgment or social critique’ (p.15). In other words, material is the key element in deciphering the meaning of a work of art, over image, object or concept. Indeed, Wu deliberately makes a distinction between Material art and Conceptual art, arguing that contemporary Chinese artworks had previously ‘been vaguely – and often inaccurately – labeled as Conceptual Art, assemblage, readymades, or object-based art’.

This positioning against Conceptual art is framed as a way to understand contemporary Chinese art outside of the Western canon, and therefore outside of the East/West binary. However, it also suggests that Conceptual art is completely divorced from material and negates the presence of material throughout art histories. Contemporary conceptual practices often incorporate material for both its physical qualities and its conceptual contents. Furthermore, discussion around materiality has always been present in art making, particularly within marginalised practices such as feminist, queer, craft, indigenous, and outsider art, often playing a central role in art histories outside of the Western canon.

The term ‘Material Art’ prompts further questions. What qualifies as unconventional material? Why is it culturally specific to China, and to which artists does the term apply? How are the parameters of Material Art defined? In spite of the fact that Wu is careful not to define a coordinated artistic movement, he nevertheless seems to treat Material art as one, located in time and place (post-1980s China), with identifiable artists and characteristics and a unified approach. In her catalogue essay, Cacchione explains that that the emphasis is not necessarily on the materials themselves, but rather, on the new relationships between artwork, artist and viewer activated by those materials. Material Art, she writes, is characterised by its ability to index the body, rupture the distinction between work of art and the commodity, and spark a direct response in the viewer. Cacchione also narrows the timeframe of Material Art to post-Mao China to examine how it influenced the artistic landscape. According to her, ‘the use of these new materials characterizes a break with past art practices and styles in China, and can be used to identify the emergence of the ’85 New Wave Movement and contemporary art in China’ (p.44).

However, for those visitors who have not read the catalogue, the exhibition reads as a presentation of a cohesive movement under the vague theme of material. Almost all of the heavy hitters in the world of contemporary Chinese art, from Ai Weiwei to Lin Tianmiao, are represented here, but without the acknowledgment that these artists are often working across different generations, continents, politics, practices and themes. Without this crucial information about the specific contexts that led these artists to investigate certain materials, the exhibition easily slips into flattening the works of these diverse artists into one simplistic narrative.

As difficult as it is to represent the nuance in the landscape of Chinese art, it is perhaps even more difficult to convey the complexity of the entirety of China. In some cases, the exhibition would benefit from more information on the traditional forms of Chinese art that are referenced by the contemporary artists, for example, or translations of Chinese characters into English and vice versa. One example is He Xiangyu’s A Barrel of Dregs of Coca-Cola, in which the artist boils the soft drink until it is reduced to nothing more than a pile of ashes. The piece is accompanied by his notes, written in Chinese, referencing ideas of transformation and impermanence from the Buddhist Diamond Sutra. Thus, while some viewers could interpret his act as a nihilistic comment on capitalism, others fluent in Chinese might instead see a reflection on the nature of metamorphosis. Without a translation of the Chinese notes, though, audiences are left with only half of the information for understanding He’s work.

Other works do however present a compelling opportunity for audiences to learn about the realities of China. Yin Xiuzhen’s installation Transformation (1997) features over one hundred roof tiles collected from various demolition sites of traditional siheyuan houses in Beijing, carefully laid out to fill the room. On top of each tile is a photograph of the site from which it was taken, each one showing the particularities of differing courtyards. By offering visitors a direct glimpse into the spaces from which each tile came from, Transformation allows visitors to draw their own insights into the tensions between tradition and modernity within the context of urban development in China.

Moments of cross-cultural insight like this are rare, particularly in a time when China and the United States are often pitted against one another. With a planned partnership with the Yuz Museum Shanghai, the exhibition signals LACMA’s position at the forefront in introducing contemporary Chinese artwork to Los Angeles, which, despite its massive Chinese and Chinese-American population, has seen few comprehensive exhibitions of art from China, or indeed Asia. For now, unusual materials such as hair, gunpowder and Coca-Cola are certain to entice new audiences to enter its discourse.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

AI-generated backgrounds give me no more crisis over the actual value of my own art than, like, photographs. immensely reproducible! idk i’m primarily a digital artist, i grapple with this! but there’s something very uncanny about AI background art and it might fool a lot of folks’ eyes into enjoying the pleasing amalgamate of the /essence/ of Fantasy Spring Book Store, but there are so many giveaways that these images are GRATING as someone who lives for drawing made-up scenes. and it’s hard to explain bc i don’t want to essentialize what “is” real valid human art and what is ~clearly AI~, like the visual boundaries are increasing amorphous and i fear for actual artists being dismissed for their work “resembling” “AI art” (there are already anecdotal stories online of this happening). it’s not about the Imaginary Spaces or the perspective being “Wrong” or the details not being Natural—these are all features that human artists embed in their work, too. there’s a really common visual artifact of AI backgrounds where they can’t track straight lines so all the euclidean details are all over the place, but i feel like a lot of other “tells” are reflective of the popular art styles used to train the software. and i don’t think a critique of “sameness” there is useful or productive. i’m not sure if 100% rejection of the marriage of machine learning+art is even useful—there are really incredible applications of this technology in field other than visual art. there are so many ethical problems with the software that currently exists (training on artists’ work without consent) but now there are programs like adobe firefly which seek to legitimize and legalize the technology by using their own proprietary images. everything has its own issues but the tech is evolving and the ethical dilemmas are evolving too

i’ve just been thinking lately about how machine learning and AI image generation slot into the discourses of modern art like…. walter benjamin would have so much to say here.

0 notes

Text

SEMINAR SERIES : ‘UTOPIA. DYSPOPIA.’ : 26/11/19

OPENING OF OUR SEMINAR:

To reassure you..

Our next seminar before the Christmas break will be on Tuesday 10th December. We will be suggesting helpful ways to engage in critical writing/reflection and essay structuring.

Some suggestions if you are stuck…

A highly illustrated, accessible guide to political art in the twenty-first century, including some of the most daring and ambitious artworks of recent times.

Why have so many artists turned to political subject matter in the last decade? Can art not only question but also reinvigorate the social, civic, and political imagination? Art and Politics Now offers a brilliant survey of artists engaged with "the political," whether in providing commentary, questioning social structures, or actively responding to the world around them.

Many high-profile artists are featured, including Chantal Ackerman, Ai Weiwei, Francis Alys, Harun Farocki, Omer Fast, Subodh Gupta, Teresa Margolles, Walid Raad, Raqs Media Collective, Doris Salcedo, Bruno Serralongue, and Santiago Sierra.

"Art as Social Action . . . is an essential guide to deepening social art practices and teaching them to students." --Laura Raicovich, president and executive director, Queens Museum Art as Social Action is both a general introduction to and an illustrated, practical textbook for the field of social practice, an art medium that has been gaining popularity in the public sphere.

The use of alternate realities in cinema has been brought to new heights by such recent films as "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" and "Donnie Darko". "Alternative Worlds in Hollywood Cinema" is the first book to analyze these imaginary realms, tracing their construction and development across periods, genres, and history. Through an analysis of such landmark films as "The Wizard of Oz", "The Others" and "Groundhog Day", James Walters reveals how unconventional worlds are crucial to each film's dramatic agenda and narrative structure. This groundbreaking volume unifies decades of divergent work by film scholars and points the way towards a new theoretical framework for understanding fantasy in the context of popular film. "Alternative Worlds in Hollywood Cinema" will be an essential resource for film studies scholars and movie buffs alike.

The Tate

Explore artworks from Tate's collection that respond to their social and political context

This wing is concerned with the ways in which artists engage with social ideals and historical realities. Though some artists associated modernism with a utopian vision, art has also provided a mirror to contemporary society, sometimes raising awareness about urgent issues or arguing for change. Whether through traditional media or moving images, abstraction or figuration, militancy or detached observation, all the artworks in this wing highlight aspects of the social reality in which they were made, and try to generate a reaction and convey a more or less explicit message to their publics.

By the end of today you will...

- A2 Identify and demonstrate an understanding of key theories and discourses that affect the practice, consumption and production of photography. - A3 Evidence an understanding of the relationship between theory and practice, and interpret, analyse and evaluate critical approaches to creative practice. - B2 Apply appropriate theoretical approaches to the study and interpretation of ........and associated media practices, building awareness of the ethical, social and cultural consequences of creative practice. - C5 Competently utilise a range of appropriate research methods and academic conventions. - D3 Demonstrate communication skills, which evidence knowledge and understanding of critical debates around creative production.

DISCUSSION:

At this part of the session we were able to discuss about our task that we were set the week prior. It was insightful to view everyones different approach to the ‘Dystopian’ and ‘Utopian’ theme that stemmed from last weeks lecture and it made me think alternatively abut this broad topic.

TURNER PRIZE

Starting in 1984, the Turner Prize is an award that recognised new developments in contemporary art. The prize is awarded each year to ‘a British artist under fifty for an outstanding exhibition or other presentation of their work in the twelve moths preceding.’

Founders decided to name the prize after J.M.W Turner - a radical painter in his day. Critics took this decision as a signal of their intention to award controversial art. There were conflicts as to whether or not Turner would have approved. However, the name was chosen because not only did Turner want to establish a prize for young artists, but Turner in his day, was considered to be controversial. Over the years ‘the Turner Prize has played a significant role in provoking debate about visual art and the growing public interest in contemporary British art...and has become widely recognised as one of the most important and prestigious awards for the visual arts in Europe.’

AGAINST

The Evening Standard critic Brian Sewell wrote “The annual farce of the Turner Prize is now as inevitable in November as is the pantomime at Christmas.”

Critic Matthew Collings wrote, “Turner Prize art is based on a formula where something looks startling at first and thens turns out to be expressing some kind of banal idea, which somebody will be sure to tell you about. The ideas are never important or even really ideas, more notions, like the notions in advertising. Nobody pursues them anyway, because theres nothing there to pursue.”

In 2002, Culture Minister (and former art student) Kim Howells pinned the following statement to a board in a room designated for visitors comments: “If this is there best British artists can produce then British art is lost. It is cold mechanical, conceptual bullshit.”

Stuckism

Founded by Billy Childish and Charles Thompson in 1999. Anti- conceptual, instead promoting figurative painting. Confrontational, frequently holding demonstrations against Turner Prize.

Banksy - ‘Mind the Crap’

Banksy once painted a warning on the steps of Tate Britain - "mind the crap". It's the kind of cheeky subversive comment his fans love him for, and in this case the target was the pretentious, institutionalised contemporary "art world".

FOR

Critic Richard Cork said:

“There will never be a substitute for approaching new art with an open mind, unencumbered by rancid clichés. As long as the Turner Prize facilitates such engagement, the buzz surrounding it will remain a minor distraction.”

In 2006, newspaper columnist Janet Street-Porter said “The Turner Prize and Becks Futures both entice though sand of young people into art galleries for the first time every year. The fulfil a valuable role.”

Dan Fox, associate editor of Frieze, said that the Turner Prize should be considered a barometer for the mood of the nation.

Nominees:

Lawrences Abu Hamdan

youtube

Lawrence Abu Hamdan is an artist and audio investigator, whose work explores ‘the politics of listening’ and the role of sound and voice within the law and human rights. He creates audiovisual installations, lecture performances, audio archives, photography and text, translating in-depth research and investigative work into affective, spatial experiences. Abu Hamdan works with human rights organisations, such as Amnesty International and Defense for Children International, and with international prosecutors to help obtain aural testimonies for legal and historical investigations. He received his PhD in 2017 from Goldsmiths London and is a practitioner affiliated with Forensic Architecture.

Helen Cammock

youtube

Helen Cammock works across film, photography, print, text and performance. She produces works stemming from a deeply involved research process that explore the complexities of social histories. Central to her practice is the voice: the uncovering of marginalised voices within history, the question of who speaks on behalf of whom and on what terms, as well as how her own voice reflects in different ways on the stories explored in her work.

Oscar Murillo

youtube

Oscar Murillo’s multifaceted practice incorporates live events, drawing, sculptural installation, video, painting, bookmaking and collaborative projects with different communities. In his work, Murillo particularly explores materials, process and labour; as well as issues of migration, community, exchange and trade in today’s globalised world. These concerns are deeply embedded in Murillo’s personal history and creative process. The artist pushes the boundaries of materials in his work particularly in the creation of his collaged-together, unstretched canvases often made with recycled fragments from the studio. Emigrating to London from Colombia aged 11, Murillo draws on his own biography and that of his family and friends, who are often involved in his performances. References to life, culture and labour conditions in the factory town of La Paila where he grew up, reappear throughout his work.

Tai Shani

youtube

Tai Shani’s practice encompasses performance, film, photography and sculptural installations, frequently structured around experimental texts. Taking inspiration from disparate histories, narratives and characters mined from forgotten sources, Shani creates dark, fantastical worlds, brimming with utopian potential. These deeply affective works often combine rich and complex monologues with arresting, saturated installations, manifesting equally disturbing and divine images in the mind of the viewer.

The Judges

The members of the Turner Prize 2019 jury are Alessio Antoniolli, Director, Gasworks & Triangle Network; Elvira Dyangani Ose, Director of The Showroom Gallery and Lecturer in Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths; Victoria Pomery, Director, Turner Contemporary, Margate and Charlie Porter, writer. The jury is chaired by Alex Farquharson, Director of Tate Britain.

3 December 2019 #TURNERPRIZE The winner will be announced on 3 December 2019 at an award ceremony live on the BBC, the broadcast partner for the Turner Prize.

Discuss - who would you vote for?

Get into teams

● Go and research more about the artist you would vote for ● You need reasons why you think they should win ● You need to look at the artists past work ● Make badges for all your team members ● Then write 100 word rationale/argument/critical appraisal of why they should win ● You need to be constructively critical

VOTE FOR TAI SHANI