#with the hope chests and the sears and roebucks catalogs

Photo

i went shopping and found a new shirt today and i feel like a dandy pirate or perhaps a poet of some sort : )

#my face#i am now going to wear this shirt with every outfit#jk first i need to find a pair of victorian era mens pants#and no i will not buy some cosplay pants off amazon or some steampunky website#and no i will not sew them either. lord knows i suck at sewing#i didnt hem the pants im wearing in the pic. i literally safety pinned the cuffs. i SUCK at sewing.#i need some proper old fashioned high waisted dzadzi pants#so i will simply have to wait for penneys or h&m or something to get creative and sell some venetian breeches#maybe amvets has some regency era clothes tucked away in the back fjdklsa#with the hope chests and the sears and roebucks catalogs#ignore bernie up there he just hangs out so i never forget my name#fluffles face#well actually my face is strategically blocked bc i Hate Pictures of Me but. its there in spirit jfkdlsa

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking Around: On Moving; or, The Story of a Little Old House

Author’s Note: This article consisted of two weeks of intense research, involving scouring over fire insurance maps, tables of wages, census records, Sears catalogs, and atlases. Before I begin, I owe some mad thanks to those who helped provide their resources and advice: preservationist Jackson Gilman-Forlini, furniture history guru Susannah Wagner, the nice folks from the Maryland Historical Society, and the research library staff at the Johns Hopkins University.

Anyone who has made copious trips to U-Haul, rendered their fingertips numb after stringing along line after line of packing tape, or spent hours intimately acquainting ones lower back with an ice pack, knows – and loathes – moving.

Moving is stressful. It is a form of migration, itself an immense change. Despite the momentous effect moving has on us, there is little to be found regarding the history of, well, moving. Plenty has been said about techniques of migration, by boat, by horse and buggy, by rail, and by car.

In novels and movies, from Harry Potter to Doctor Zhivago, there are scenes of train stations, carts with ornamented trunks, and porters donning funny cylindrical hats to haul them. In photographs of Ellis Island complete with their visual narratives of the American Dream, we see thousands of hopeful newcomers cheering gleefully, suitcases in hand.

As time goes by, the railway porters are replaced with truck drivers; the journey implied by the ocean liner morphs into bucolic images of a smiling suburban family on the island-lawn of their poorly-shuttered idyll.

Family Moving to their New Home. Washington State, 1935. via Library of Congress.

Why am I writing about moving? Over the last two weeks or so, I, myself, moved. I moved from a dingy (yet immensely charming) self-constructed room in what used to be a Cork and Seal Factory, to a little 812 square-foot Baltimore rowhouse.

Each of the times I’ve moved from apartment to apartment (and finally, on this move, to an actual, full-sized house), there have been great difficulties loading and unloading all of my crap – difficulties innate to the houses themselves. These were usually small hardships, involving the clever rotation of a sofa or armchair in order to wrestle it out the door.

This time, however, I came to a horrifying revelation: None of my existing furniture would be able to A.) fit within the cramped dimensions of the narrow staircase or B.) make it around the corner in the shallow hallway to my room.

I solved my problem the same way as any reasonable millennial:

Photo by Rainchill. (CC BY-3.0)

Yet, as I loaded up my cart with brown box after brown box, I couldn’t help but wonder: What did people do before Ikea? Why were the stairs so narrow, and more so, what went up them before my trendy flat-packed furniture?

The Little Rowhouse

According to two days of scouring archival newspapers and other primary sources, I could gleam a few interesting things about the little brown rowhouse into which I’m currently schlepping my stuff.

The Little Brown Rowhouse (center). Via Google Maps.

The rowhouse was built sometime between 1900 and 1902. A Baltimore Sun record from 1898 shows the auction of parcels of land where the house would soon be built:

EDIT: My colleague, Jackson, has found out that the house was built by a pair of builders named John S. Kidd & William A. Davidson.

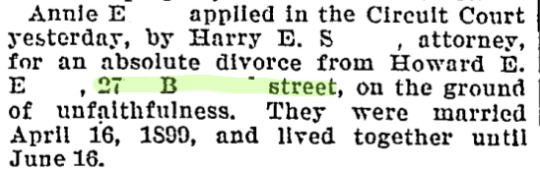

However, the first mention of any of the houses on the row (that is to say, even-numbered houses, as the houses on the opposite side of the street are of a different design), comes later, in 1902, in a divorce notice:

In 1905, the house next door to mine was for lease:

Unfortunately, no searches for C.W. Webb pulled up anything of note.

I learned some other interesting things during my newspaper dig, (most notably that the folks who once lived a block south from me got busted during Prohibition) - but ultimately, came to a dead end on my original topic: what kind of person moved into my rowhouse first, and how they did it.

The Process

In order to glean how working people moved back in the early 1900s, I decided to focus on a few key areas of research:

What kind of wages the family would make, what they would spend it on and what kind of local industry they might have participated in.

What kind of stuff was being moved; (AKA what kind of furniture these folks bought and how much it cost)

What the costs were of moving services during this time, and whether they were affordable for the family in question.

Potential Jobs, Wages, and Expenditures

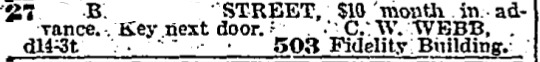

The best way to look for what kind of industry existed in a certain area at a certain time is through a series of maps by the Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. These maps were used for evaluating fire risk (and therefore how high the premiums should be for fire insurance.)

In the index of a Sanborn Map, there are two parts. First is the list of streets, with a number, corresponding to a plate number. The second is a list of industries along with larger businesses, schools, orphanages, and churches, along with their plate numbers. To find out what kind of industry was near the street you’re looking for, simply look for industries relatively close to the plate number of your street.

It’s likely that the folks who lived in my house worked in one of two places: as a railworker (at the Maryland & Pennsylvania Railroad, The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad; The United Railroad & Electric Company) or in the stone quarry (Sisson Marble Works, not shown in screenshot). Working class women often worked as well, most likely in the nearby textile mills lining the Jones Falls River.

There are a few smaller industries these folks could have worked in as well, such as the Columbia Motor & Manufacturing Co., The American Can Factory, J. Stack & Sons Lumber, or the Schier & Bros. Dairy. However, it’s most likely that the person who first lived in my house was a stone or rail worker, as the house used to be mere blocks from both the quarry and a massive rail yard:

Image from a 1905 Map. House is in top-right corner, in red.

Okay, so we know where the head of the household likely worked. How much did they make doing it?

Were the head of household a worker in the nearby marble quarry, he (women did not work in the quarry in 1900) would have made around $813 a year.

Source: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008319974

Were they a railworker of some sort (the average workweek of railway workers in nearby Pennsylvania was around 62 hours/week in 1901) they would have made somewhere between $420/year as a day laborer and $1350/year as a senior engineer. Source.

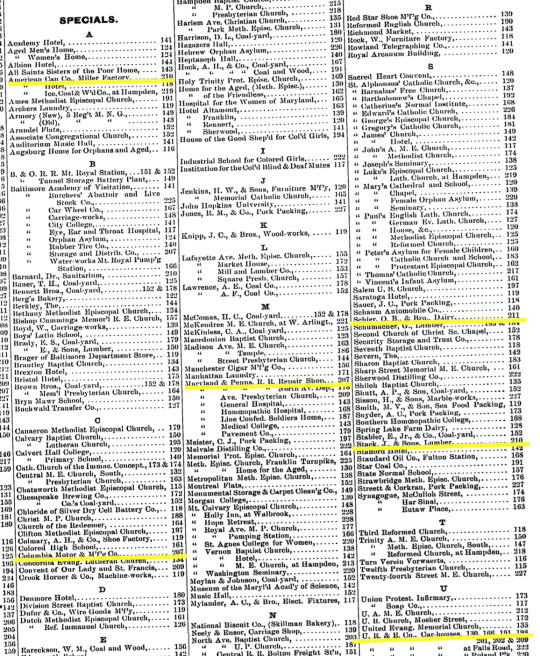

What would these folks spend these wages on? Here are some more statistics (average expenditures) from Pennsylvania (a neighboring state with similar industries.)

Source.

Now that we know what these folks might have made (on average), let’s see what kind of goods they possibly purchased.

Furniture

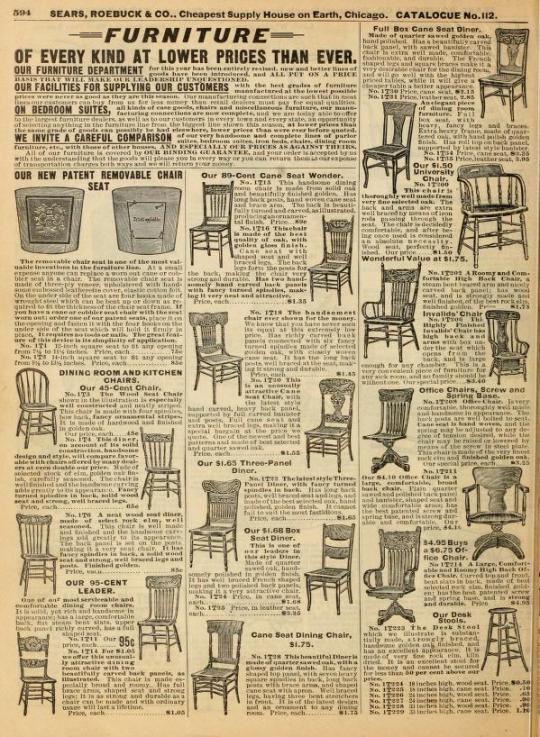

It’s difficult to know what kind of furniture most working class folks had in their houses. According to my sister (Hi Suz!), who studies furniture history at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, it’s possible that a family working in 1900 bought some pieces of mass-produced furniture, like that sold by Sears Roebuck & Co.

Page from a Sears catalog c. 1900.

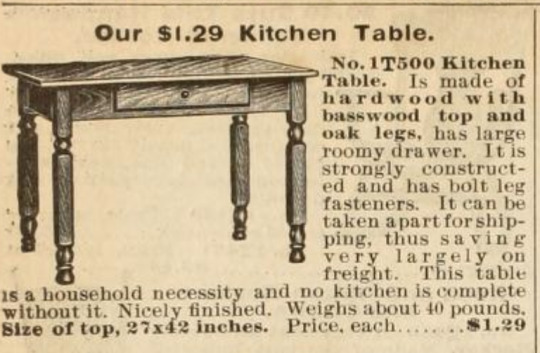

The truth is more difficult, because much of the mass-produced, inexpensive furniture of the time was made out of cheap materials such as basswood and has not survived. It’s also possible that the family had some pieces passed down from generation to generation, which wouldn’t be accounted for in primary sources from the time. What is true, is that there is a certain amount of furniture most folks need for their homes.

Fortunately for us, there are photographs in the Library of Congress of tenement and other working class interiors, enabling us to get a better picture of what folks had in their homes:

Kitchen of a Railway Worker. New York, 1911. Library of Congress.

Living area of a NYC Tenement. 1912. Library of Congress.

Small interior bedroom of a tenement. NYC, 1912. Library of Congress.

Descriptions of working class housing from the book Working Class Life: The “American Standard” in Comparative Perspective, show some common similarities between how working class homes were furnished; the most important being that average expenditure on furniture rose when folks were paid more. Often, according to the book, almost $13 per year was spent simply replacing cheap linens, curtains, and cutlery alone, so there was little room left over for additional pieces. (204)

Typically, there was a shared living and dining room, centered around a table, surrounded by Windsor or ladder backed chairs, perhaps a sofa and chest-of-drawers, a few trinkets and photographs, and perhaps a rug.

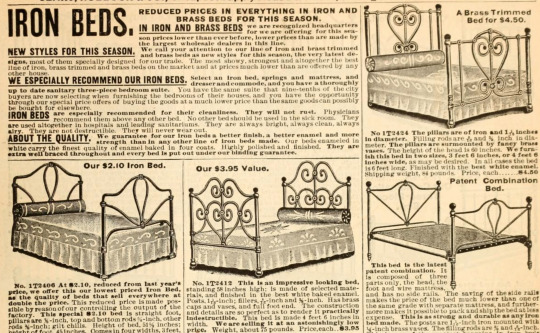

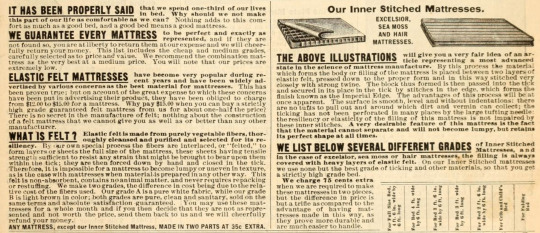

Most of the time, upstairs rooms were almost unfurnished, having only an iron bed frame and felt mattress.

Those who made a little extra had more frills: a rocking chair and china cabinet in the front room, and in the bedrooms, mirrors, and bathroom fixtures like chamberpots and washbasins. (203)

This description perfectly coincides with the Baltimore rowhouse, which has two bedrooms, a kitchen, a living room, and a basement (likely unfinished until much later). The bathroom, like most bathrooms in dwellings built before 1910, was a more recent addition. Therefore, It’s likely that the folks who first lived in the little rowhouse had furniture and rooms like those described above.

Which brings us back to...

Moving

As far as the answer to the initial question of “how stuff got up the stairs”, the answer is that, frankly, not that much had to go up the stairs in the first place.

Most mass-produced iron beds could be dismantled and taken upstairs in parts. Felt mattresses were extraordinarily thin by todays standards, and, because they’re stuffed and pliable, the family would have little trouble navigating the tricky corner at the top of the stairs. As for the more luxurious items, mirrors, basins, and chamberpots, all are also easily portable.

The answer to the second question, which was how would a family move from one home to another is, sadly, we’re still not sure. What is certain is that, if they came from another city, they probably didn’t take much with them, as shipping or transferring things by train was extraordinarily expensive by working class standards: the Pennsylvania railroad charged 75¢ per piece (not counting oversized items) - to move one item alone was about a full day’s work for a common day laborer.

If the family were moving within the city, it’s highly unlikely they used a moving company, as the prices for such were hefty as well at 25¢/piece, as advertised in 1898 by this local furniture mover:

A local anonymous opinion from 1904 corroborates this price range, bemoaning the techniques the moving company used to transfer items:

What’s more likely is that the family either had some way of bringing what existing furniture they had to the new house (usually by horse & buggy in 1900) or they bought furniture either by local/national catalog, secondhand or from one of the myriad small dealers or manufacturers in the city itself, seen here in the 1905-1906 edition of Polk’s Business Directory:

As it turns out, the folks who first moved into this house did so in a way not that different from me. They probably called up some folks to help haul what they could (if they were moving within the city) and what they couldn’t, they bought.

Besides, what’s Sears if not the Ikea of the past?

If you like this post, and want to see more like it, consider supporting me on Patreon! Also JUST A HEADS UP - I’ve started posting a GOOD HOUSE built since 1980 from the area where I picked this week’s McMansion as bonus content on Patreon!

Not into small donations and sick bonus content? Check out the McMansion Hell Store ! 100% of the proceeds from the McMansion Hell store will go to help victims of the recent hurricanes.

Copyright Disclaimer: All photographs are used in this post under fair use for the purposes of education, satire, and parody, consistent with 17 USC §107. Manipulated photos are considered derivative work and are Copyright © 2017 McMansion Hell. Please email [email protected] before using these images on another site. (am v chill about this)

#history#architecture#baltimore#moving#american history#working class#1900s#victorian era#sears#sociology#looking around#furniture

990 notes

·

View notes