#wrapover

Photo

GEO - think this is a winner? This one caught my eye immediately, strong colours, bold style and perfect length, what’s not to love! Will link the dress in stories. 😍 Wore this to lunch for my mum’s birthday in October, when it was warm and sunny! Dress @izabel_london * *Pr Product/Sample Thanks for stopping by and apologies for my erratic posting, it’s the run-up-to-Christmas madness! I’m off to Germany tomorrow, so hope to post a bit more when I’m back. Cheerio my friends. #geoprint #ootd #fashion #styleoftheday #izabel #mididress #wrapover #bluedress #blackheels #slingbacks #love #midlifestyle #brunette #over50 #over40 #chic #chicandstylishme #whitstable #canterbury #whitstableblogger #fashionblogger #blogger #birthday #lunchtime #tylerskiln #tylerhill (at Kathton House at The Tyler's Kiln) https://www.instagram.com/p/Clncn9UM7hN/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#geoprint#ootd#fashion#styleoftheday#izabel#mididress#wrapover#bluedress#blackheels#slingbacks#love#midlifestyle#brunette#over50#over40#chic#chicandstylishme#whitstable#canterbury#whitstableblogger#fashionblogger#blogger#birthday#lunchtime#tylerskiln#tylerhill

0 notes

Photo

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costume Parisien, 25 novembre 1820, (1944). Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

Woman wearing a hat of 'plush de soie bouclée' decorated with marabou feathers. She wears a spencer with a wrapover, ending in two points with tassels. Below is a dress made of cotton batiste (percale) decorated with pleated strips of muslin. Further accessories: handkerchief, flat shoes with bows. Proof of a print from the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1820s#1820#on this day#November 25#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#proof#description#rijksmuseum#dress#Mésangère#spencer

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Live a Little

LEFT: Long flowing marocaine wrapover dress with frilled cap sleeves, Radley for Ossie Clark, £15, from Quorum, 113 King’s Road, SW3. Swallow brooch, Adrien Mann, approx £2; antique satin clutch bag with rhinestone star, Titfers, approx £8. RIGHT: Keyhole-fronted crêpe button-through party dress with Chinese word pattern, £12.95, from all branches of Bus Stop, mail order 20p extra from 3…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

DOWN ON THE FARM: Chocolate-Brown Poly-Cotton Blouse with Front Pintucks; Wrapover Overknee Skirt in Grey & Brown Mix Fabric; Gold Heart Locket & Chain; Brown-Suede Knee-Length Boots with Matching Belt

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

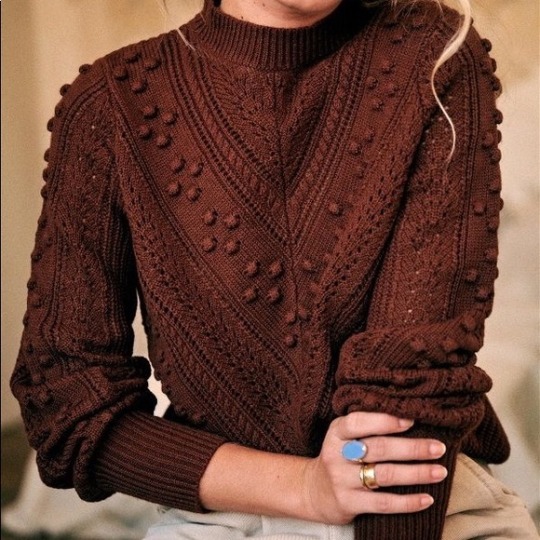

Sézane - {Inspired}

Sézane is a French clothing brand dedicated to designing quality, classic pieces. The collections are often vintage-inspired and in earthy color palettes. I find the knitwear to be unique, detailed, and feminine, adorned with cables, lace, colorwork, and bobbles.

I have included some of my favorite Sézane knits from current and past collections, as well as some patterns from Etsy and Ravelry that I find fit the Sézane aesthetic.

{THE INSPIRATION}

Left: Basile Cardigan | Right: Come Jumper

Solal Jumper

Left: Gaspard Cardigan | Right: Timothee Cardigan

{THE PATTERNS}

{Fabel Knitwear - Forest Berry Jacket}

Website | Ravelry

{Camilla Vad - Magnolia Bloom}

Ravelry

{Tricot Design MCL - Perline}

Website | Ravelry

{Jennie Atkinson - Wrapover Cardigan}

Website | Ravelry

{Teti Lutsak - Voila Blouse}

Website | Ravelry

{Sirdar - Lace Textured Cardigan 10199}

Website | Ravelry

{My Favourite Things Knitwear - Cardigan No. 4}

Website | Ravelry

• KNITSPIRATION •

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Eloquii Women's Satin Dress With Wrapover Skirt.

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: H&M Sequin Wrap Dress Size XS.

0 notes

Text

JR International the proud owner of the brand “JR Shawls & Wrapover” is a professionally managed organization and one of the largest Exporters of exclusive Shawls, Scarves and Stoles in New Delhi, India since 2008. We are exporting genuine quality products in various Yarns and blends like Pure Pashmina, Cashmere, Silk Pashmina, Fine Wool, Silk Modal, Cotton Modal, Wool Modal, Cashmere Modal etc. Our Products are skillfully crafted by traditional weavers and artisans. With a strong foothold in the market, we have proudly expanded our services to Europe, USA, UAE and other regions .

JR International also specializes in Custom designing of Shawls, Stoles & Scarves as per buyer’s requirement. Our quality monitoring department conducts tests right from the time of raw material procurement until the final delivery of developed products to make sure that best products are delivered to our clients. Our dedication to excellence has earned us the trust of customers who appreciate the artistry and uniqueness of our products.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: H&M Ruffled Skirt - Black Floral.

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: ☘️NWOT H&M emerald green draped cropped halter size xxl.

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: H&M Purple H&M Rayon Midi Floral Print Frills Dress New with tags.

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Nasty Gal Belted Wrapover Blazer Coral Size 4 New.

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Maje Mandarin Peach Piruize Ruffled Shoulder Jumpsuit Silk Linen Size 34 0.

0 notes

Text

Short Story

THE ICE BEAR

BY

HELEN DUNMORE

The spicy heat of Stockholm station café knocked her out. She went limp and drunk. She’d been travelling a long time, coming home the awkward way through north Germany. Ferry across the Storebaelt, train, another ferry across from Helsingør, train across Sweden. Now she was here, still feeling the bump and rise of travel in the soles of her feet. She’d worn the same light cotton drawstring trousers all the way from Yugoslavia, and now she was itchily cold and her tanned feet looked yellow, not golden any more. There were three hours to go before the last ferry, the ferry home, sailed from Stockholm harbour across the Baltic. She could get a hot bath here, she knew, and wash her hair and strip off her dirty underwear and change the flimsy trousers for a pair of jeans.

But she’d been wrong. Things had changed over the summer she’d been away. They’d closed the bathrooms for renovations. Only a few showers were working, and as soon as she’d paid her money and was naked and streaming with water and shampoo, she’d seen that the floor drain was blocked in some careful fashion which meant that water had seeped out into the fresh clothes she’d laid on the tiles outside the shower cubicle, into her towel and her dirty underwear and even into the lining of her canvas boots. Everything was sodden. She wrung out the towel and wiped the water slowly and carefully off her shivering body, and then wound the towel around her head. She had no more clean pants. The dirty ones felt unpleasantly smooth and loose against her skin. She eased herself into her jeans and they gripped her damply at waist and crotch. She’d worn nothing heavier than Indian cotton for weeks, shirts and trousers and wrapover skirts which now lay rolled into faded dirty balls at the bottom of her rucksack.

But at least her leather jacket had stayed dry, hung on the back of the shower-room door. She put it on over her bare breasts and zipped it up to her neck. The springy curls of its sheepskin lining closed over her like home. She was safe again. She started to pick up her strewn dirty possessions. Well, naturally the bath-woman broke into a temper. She was trying to keep these shower-rooms nice for all the passengers, didn’t Miss understand. God help us all, she would have thought that anyone would have had the sense to see the drain was blocked and not to use this shower. There was a bell over there, look, with CALL FOR ATTENDANT printed underneath it. Amazing these students, with their university educations, not able to read a simple notice. And it was no good Miss bursting into tears. That didn’t help anyone.

The bath-woman bent down from her hips and swabbed the floor with a yellow cloth. She didn’t have to do that. She didn’t have to present her long-suffering backside to heaven as evidence. She had a perfectly good long-handled mop. But she just knew how bad it would make Miss feel to see the spread of the fat round her back as she bent, and to see the cloth stabbing into the corners of the bathroom, picking up soap scum and long dark hairs and globs of spilled shampoo. The bath-woman knew Ulli’s sort. You called them Miss to be civil. Jeans so tight she must’ve poured herself into them, or else a bit of skirt like a dishcloth showing everything she’s got. And then she wonders why she gets herself into trouble.

The café was filling up. Ulli twisted a corner of tissue into a wick to draw up the last of her tears. It was no problem really and anyway she was all the better for crying. She would hang up her wet towel and wash out her bra and pants in the Ladies once she was on the boat. Or why bother? She was nearly home. Three months ago the towel had been striped in dark pink and French navy, but the colours were faded now. She had dried the towel in the air of so many countries. She kept a length of string with her and she could quickly make a line under the luggage racks or across the window of a train compartment. She did not get in anyone’s way. She ate garlic sausage when it was offered to her, and she passed her bottles of mineral water and wine from mouth to mouth. She ate heavy yellow Spanish bread, puffs of brioche, black pumpernickel which reminded her of home, and drank milk cow-warm from a high, green, wet Bavarian pasture where a woman milked her two cows in a shed. Ice-cold or cow-warm? the woman asked her. There was a bucket of the morning’s milk chilling by the stream.

There were Bodensee apples and split figs from Dubrovnik market. On the Austro-Hungarian border there were baked ears of sweetcorn and tomatoes hanging on shrivelled vines, but no one to sell them. A white dog lolloped through the fields and licked Ulli’s feet. A poor skinny creature with yellow teeth spotted brown at the roots, and a healed gash on its right flank. A poor creature but scrabbling and close and companionable. It grinned as Ulli bit into the flesh of one of the tomatoes, as if it wished her well in drawing nourishment from something it could not eat.

At night Ulli rolled up her towel into a pillow and pressed it into the back of her neck as the Japanese do, so that she slept deeply. Very often she did not feel the formal pressure of the customs officer’s hand on her shoulder as the train went through some frontier in the middle of the night. She was too deeply asleep to hear voices calling up and down the train asking for papers, or to hear the compartment doors banging open as the frontier guards scanned faces shrunken with sleep. Tanned guards who wore their uniforms easily, boys with good homes near by perhaps, bored but attentive. Sometimes, by the time Ulli woke, not only the customs officials but several other righteous people in the compartment would be calling her through the noise of trains and dreams: MISS, MISS, MISS…

So now she had got rid of her tears. She sat in the upstairs café with enough Swedish money to buy herself two coiled buns scented with cardamom, and her own individual pot of coffee. Now a young man came to sit at her table. He glowed in his dark yellow waterproof jacket and over-trousers and his warm, silly cap which must have been knitted by someone who loved him. Or else why would there be so many changes of colour and so many different stitches in one cap? It would have been made by someone who loved him, making work for herself. He took out a book and glanced at her as if he wanted her to register the fact that this was a serious book and that he was reading it. Or perhaps there was more to it. Perhaps he had written it himself, she thought. It had a flat grey cover and thin papery leaves like slivered almonds. It looked as if it came off a small press powered by enthusiasts.

She sat eating her two split buns. She had spread butter on the one half and not on the other, to see which tasted better. Now her body was steamed and hot and fed. She pushed back her damp hair which she’d drawn forward to hide the snaily runnels of tears on her cheeks. Her hair was going into curls. She was just about to unzip her jacket when she remembered that she was wearing nothing underneath.

Before long the young man was talking to her. He too was taking the boat across to Finland. He adhered to a minor Lutheran sect, stricter and purer than the mainstream body of the church, which had gone astray, he told her. It was all very well to run social projects and be involved with down-and-outs and alcoholics, but you got nowhere by ignoring the question of personal salvation. It was Satan who had made us ashamed of the word sin. The young man was going to travel from town to town in northern Finland, on mission work. Every detail had been arranged. He showed her a map, with the towns where he would stay to give the mission marked by green circles. Beside the circles there were the names and addresses of the people who would look after him while he was there, members of the same sect who had been ploughing the ground ready for his seed. Even though he had never met them, they were all his brothers and sisters. This was the first time he had been thought ready to undertake such a mission on his own, without the support of senior and more experienced members. It was a challenge, and a great honour. He had lain awake for several nights thinking of the responsibility placed on his shoulders. Several. That sounded very suitable, Ulli thought. Just the right number of nights to lie awake. Nothing to excess.

But he had to tell Ulli, even though it made him ashamed of himself and he could only say this to her because she was a stranger, that he was torn between love of his wife and love of his mission work. He had just left his wife. He had had to part with her for six weeks. And they had only been married since April. He would show Ulli a photograph. No, it was no trouble, he had one always in his breast pocket.

Ulli did not want to see the photographs. She held her sticky bun out of the way and looked unwillingly at a stiff, bland, white-haired girl on her wedding day. Not much dressed up. It’s not the custom with us. In another photograph the same girl was crouching on her skis, with a tiny child wedged between her thighs. The child wore a knitted cap and a snowsuit and had its own small skis. His wife’s nephew. His wife loved children and they always liked to be with her. They would ring up and ask if they could come and spend Sunday afternoon with Auntie. She would make sweet cake and tie balloons to the apartment door. She would make little parcels of the cake, in blue and silver paper, and they would have treasure hunts round the apartment to find where she had hidden the parcels. And sometimes she would put in a little verse from the Scriptures with the cake and later on she would sit the children down with her and talk to them about it so that they would understand it.

He showed her another photograph of the nieces and nephews at their summer house up in the north, naked in the sunshine and dappled all over with the patterns of leaves. Their faces gleamed with health. They were blond and well-fed, with straight, even teeth. Animalish, Ulli thought.

‘My wife is with her sister now,’ the young man said.

But for the moment Ulli had had enough of these holy people with their sweet cake and their shiny metal pails for gathering berries in the forest in autumn and their straight-limbed children murmuring prayers at bedtime. She could see the sisters hunting for mushrooms:

‘Come, children, on such a beautiful day let us enjoy what God has given us!’

When they stumbled on a strange blub of fungus lunging out of a fallen branch they would not kick it away in disgust. There was bound to be a lesson in it. They’d take it to the apothecary’s to have it checked in the book to see if it was safe to eat.

The young man offered to carry her rucksack to the boat, but she said no. In spite of this he stayed beside her, continuing to talk about the summer house and the forest, and the summer just past, the first summer of his marriage. She would have thought he was drunk if she hadn’t known it to be impossible. No, it was just the exaltation of opening out his precious life to a stranger; a stranger who might perhaps profit from it. She was a dry run for his mission. So far he had asked her nothing about herself. Perhaps that came later, or perhaps it didn’t matter.

Two station officials strolled by and grinned at the young man. To her it seemed friendly, but the young man was embarrassed and annoyed. Then it gushed out that these same two officials had seen him saying goodbye to his wife not an hour before, which had naturally been a very serious moment for them both. Now they would think badly of him for walking along cheerfully with another girl at his side. They might think that he had arranged to meet the girl and that the kissing and clutching his wife to him had been insincere, one of these games that fool nobody and are not even meant to.

‘They were just looking at you. It didn’t mean anything,’ said Ulli.

Already a slow stain of ideas seemed to be spreading into the gap between the young man and herself. How could she tell him inoffensively that he was not the kind of young man whom girls would wish to meet for brief occasions of sin, after which he could repent luxuriously to his wife? So his wife had come to see him off. It was necessary to move her mentally out of the dark forest with leaves falling from the birch trees and her sister cooking coffee so that they could talk of mission and chickenpox at the white scrubbed table while the children played on the lake shore. No, his wife was on a train streaming its way north through the suburbs of Stockholm. Perhaps she had a headache. Perhaps she hadn’t managed to get a seat and her fresh bland body was pressed against that of an engineer who scarcely noticed her because he was dreaming of his Friday-night sauna and a tall, thick glass of chilled beer.

Ulli felt scorn for such wives rise in her. Wives who know somewhere, secretly, that for their warm children to bloom by the stove and for the coffee to taste as good as it does there has to be rain beating against the windows and a knife of wind trying to get in through the flouncy curtains. There has to be a risk of cuts in social security, and a campaign against vagrancy. There have to be kids without jobs in too-thin jeans racing from the launderette to their bedsitters which smell of damp, in cities where they know no one. There have to be divorces and children dying of leukaemia and ships going down and desperate struggles in the darkness.

The young man flipped out his tracts like playing-cards on the Formica table of the ship’s restaurant. In a moment he was going to look at the menu. There was good Swedish cooking on this boat, he could tell her that. He had taken off his waterproofs and bared his intricate jersey of Icelandic wool. Yes, his wife had knitted it for him. Also the cap.

‘I’m going out on deck,’ she said.

‘Well, that is good, while you are gone I will do my work,’ he replied springily. In just a moment, she thought, he will put that photograph of his wife down among the tracts. The ace in his pack. With her there, he will always make the highest score.

Outside the windows Ulli could see people walking around the decks, their clothes blowing lightly against their legs. They laughed as they came round the curve of the ship and the wind caught them. Ulli half-rose from the table, but the young man asked if she would look after his things until he came back from the self-service counter. She watched over his tracts and his good luggage and his waterproofs until he came back with the ship’s special, a large all-day breakfast. He put down the tray and spread out his plates, his cup and his cutlery, and then he wiped the tray with a paper napkin and took it back to the collection point. While he was gone, she looked at his food. There were oval slices of sticky black bread, twists of sweet white bread with poppy seeds, sweet-cream butter in a small plastic churn, a fan of sliced Emmentaler and Edam, another of dry pink ham. He had a frosted glass of apple juice, and a smoking pot of coffee.

The young man smiled at her as he sat down and spread another clean napkin in his lap.

He told her that girls like her were always thinking of slimming. It was foolish of them. And the very worst thing was to go without breakfast. Every morning he sat down with his wife to a breakfast like this. No matter how late they had gone to bed, no matter how busy the day ahead – and their days were very busy. Before they went their separate ways they would sit down together and relax over their food and their coffee. His wife always put napkins on the table, and flowers. It was a very special time of the day for them both. Sometimes they’d have important things to tell one another, sometimes they’d just chat.

‘It’s wonderful,’ he said, leaning towards her so she could see the sheen of butter on the inside of his lips. ‘There’s nothing I cannot tell to my wife.’

Ulli’s mouth was puckering at the sight of so much food. The white, solid, spicy cheese. The thin ham with orange crumbs at the rim.

‘I must go out on deck,’ she said.

‘Yes,’ he agreed, ‘you look pale.’

She jogged his arm as she squeezed past him into the aisle, but luckily he had not overfilled his coffee-cup. Nothing slopped, nothing was lost.

The ferry was well out of harbour. All around the flat grey Baltic stretched lankly to the horizon. She thought of her last crossing, going west at dawn on a June morning, with the sea alive and transparent all around, lapping the islands as the ship nosed its way between the poles marking the deepwater channel. She had leaned out over the rails to watch the depth change. You could see rocks and white sand with weed rippling across it. They went past island after island, uninhabited, rocky, solitary. Then there had been a bigger island with birch trees and smoke rising from a summer cottage, and a dark-blue rowing-boat tied up at the jetty. They’d passed so close she had heard the water suck at the underside of the jetty. Their wake spun out behind them and the little dark-blue boat went up and down like a rocking-horse.

But now the Baltic had the dark look of late autumn on it. Now the ship throbbed along purposefully, more alive than the empty sea around it. Ulli crisped her hands in her jacket pockets. The wind filtered between the waistband of the jacket and her bare skin. Little prickling slivers of cold. She ought to keep moving. Ahead of her a group of drunken Finns lurched around the deck, arm in arm, the end one of them catching hold of the rail to steady their line. They opened their mouths and bawled out a song which had been on the radio twenty times a day all summer, all over Europe. They were like angry babies with their square mouths and their rumpled cheeks, she thought. They made her tender to them in spite of herself. Small square solid self-respecting men in quilted jackets. Their flesh and hair blending to the same colour as the Baltic. But beneath that blend, a flash of wildness and melancholy, like a knife gliding through snow. She knew them all. They were the men who drank in the bar with her father, though he didn’t work with them any longer. Education had moved him on. They were the men who’d found her after-school jobs when she was fourteen. The ones who organized collections for women whose husbands had accidents at work; the ones who planned orgiastic, ritual surprise parties when someone was transferred or retired. She knew how quickly their fierce comradeship of songs and schnapps in the breast pocket could change to fighting drunkenness.

Last winter there’d been an exhibition of drawings from north Sweden in the Town Museum. She’d gone there one freezing afternoon. She’d had three red tulips in a cone of plastic to take on to the house where she was asked for supper, and she couldn’t find anywhere to put them down. The cloakroom attendant wouldn’t take them. Drawings from north Sweden. Squat dark scrawled people, shovelling earth. Women with muscles like ropes in their necks, wrestling with cattle. All of them lit from underneath with the same light of wild disturbance. A dark skimming line of forest off to the right. The people weren’t looking at the clods of earth they turned, or the pigs they tended. Their eyes were pinched and secretive. One man rested on a pitchfork and gazed out to where the dark scribble of trees was stirring in the first north winds of the winter. One woman picked potatoes for the clamp. She had her child pressed against her skirt as she went down the rows of churned earth. Her big hands were wrapped in sacking, but the finger-ends poked out of it, chapped. She had bound her child’s feet over and over with more strips of sacking. The child’s blunt pale face glimmered against her skirt.

Well then, why aren’t I a wife? Ulli asked herself. Why haven’t I made sure to have enough money to buy myself an all-day breakfast as of right, and stuff it down in the face of someone who’s craving for meat and cheese for once instead of cheap sweet buns? Why don’t I feel confident that the facilities of the ship have all been designed with me in mind? And why hasn’t anybody told me what they are, those important things I ought to be talking about over a breakfast table set with napkins and roses? How does a young man like that look at me and know without even thinking about it that I’m not wife material?

She turned back. She could still see the young man through the restaurant window. He must have felt her gaze, for without looking up he curled his arms protectively around his plate of ham and cheese. She waved and he looked up and saw her. He looked up and out at her with his pale Lutheran eyes. His big woolly jersey had fluffed up in the heat and steam of the restaurant, like the fur of an animal which scents danger. He had his shoulders hunched and his pale tight curls merged into the wool of the jersey.

Ulli recognized him. He was an ice bear, standing on his own perilous floe of ice. He had bumped and nudged into her and now they were just slipping apart again, so gently that you couldn’t tell where the crack had started, how it had parted. The gap wasn’t much. Half a metre, then a metre. She could still jump it. But she was better off without the ice bear, she thought. Bears look woolly and white but they’ll claw you up for the use of their mate and their young. She’d seen little ice bears gambolling in the wreckage before now, feasting on the bones. The water was sharp and dark with ice. The bear’s breath would be meaty and hot, and there would be words like adultery stuck between his teeth.

She’d walk right round the ship. She scooped back her hair and tucked the flap of it into her jacket collar. Now her jeans were dry and warm again, and her blood was beginning to course. The wind from across the sea beat colour into her cheeks as the ferry drummed on across the Baltic. It felt so good to have the weight of her rucksack off her back for once. She knew she could trust the young man to guard it for her as conscientiously as he would guard his own breakfast. Ahead of her, the drunken Finns were blocking the way to the foredeck. They saw her coming and one of them unhooked his arm from his neighbour’s to let her pass. She smiled thanks and he called after her as she went by:

‘Miss! Miss!’

She turned and saw he was holding out his bottle of schnapps to her. His friends were smiling him on, smiling their flat curled smiles. A trip for the boys, a day trip or a whole weekend of steady drinking and going wild, away from children and wives. Two swayed together, propping each other. But none of them was out of his head. None of them was fighting drunk yet. They wanted it all to be OK. They wanted her to like their friend, to drink their schnapps. She looked at the man holding out the bottle and saw that to him she was really Miss, in her jacket and jeans just like any of their daughters. Maybe they couldn’t understand their daughters either. Maybe their daughters were at university, ill-dressed, no credit to their fathers who had saved up to take them for a meal out at the best restaurant in town. Daughters who spoke scornfully of good jobs, and refused to understand that education was something to make use of.

She could bet the bottle of schnapps that not one of these men had a text of scripture anywhere about him. She took the offered bottle of schnapps, which was wet around the rim with the saliva of the men who had been drinking from it.

‘Good health!’ she said, and lifted the bottle to her mouth and took one swallow of the dry burning liquid. It went down and lit up the spread of her veins right to her finger-ends. A wave of her newly washed hair curled around the bottle and then the wind flapped it free. She handed back the schnapps to the man who had given it. He ducked his head formally, half in a nod, half in a bow.

‘She’s not one of those Swedish girls, is she?’ grumbled one man on the edge of the group, who was shifting about, restless with all this. But the one who’d offered the drink turned round on him.

‘No, the Devil take you, she’s not,’ he said, in drunken, dignified reproof. ‘Are you, Miss? She’s one of us. She’s on her way home, and glad of it, I bet. She’s had enough of those snobs over there with their mouths screwed up like arse-holes, haven’t we all?’

No, not a drunken overnighter with the boys. She’d got it all wrong. They were working over in east Sweden, guest-workers of the north, putting in their overtime and keeping their noses clean. And home by ferry two weekends a month. She hoped the ice bear would not ask them to love him for parting from his flowery breakfast table for six weeks.

She thanked the man for the drink. He held out his hand and she took it, and then she stepped away and walked on to the foredeck where a bit of pale autumn sun put a grey shine on the planking. The ferry was going faster now. It creamed away the sea from its sides, and when she put her hand on the side of the funnel it was trembling. She walked on and a hot wall of noise from the engine-room drowned out the men’s singing.

0 notes