#yes technically the actual sex scene was not wilson - But

Text

the fact that house has CANONICALLY WATCHED PORN STARRING WILSON is fucking insane it all just keeps getting gayer and gayer

#house md#house season 6#house 6x15#yes technically the actual sex scene was not wilson - But#my point still stands#hilson#op

593 notes

·

View notes

Text

starfire & born sexy yesterday

So what is born sexy yesterday? This trope was introduced to the internet by essayist Pop Culture Detective as a lens through which to analyze adult women in science fiction media who are typically extremely attractive but are oblivious to both their sex appeal and to the ways of the world. This naivete is either intrinsic to their personality or a result of these characters literally being born yesterday (an example of this would be the Fifth Element's Leeloo). To keep it short, born sexy yesterday means a character with specialized intelligence but with the experience, mind, and personality of a child in the body of (most often) a grown woman who is usually highly sexualized and objectified. It's a trope that crops up in science fiction with an alarming frequency. Almost always, there is a man (typically ordinary in every way except for the fact that our Born Sexy Yesterday character falls for him) that guides the Born Sexy Yesterday through the ways of a world that are completely new to her. Seeming to possess an abundance of knowledge and intelligence, the Born Sexy Yesterday finds him irresistable and falls in love with him.

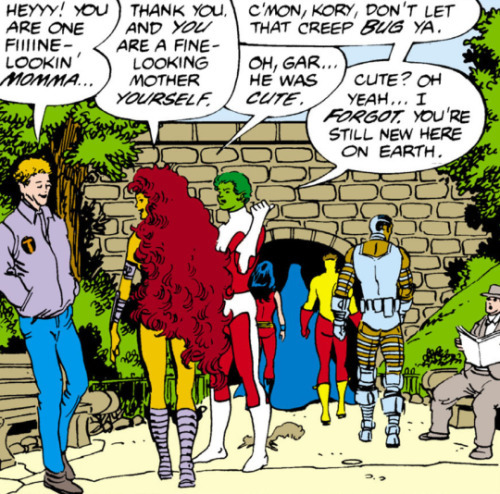

At a glance, Starfire's character seems to fulfil some of the basic characteristics of this trope. As a literal alien to Earth, Koriand'r meets a handful of these requirements:

Innocent of the ways of our world?

yes.

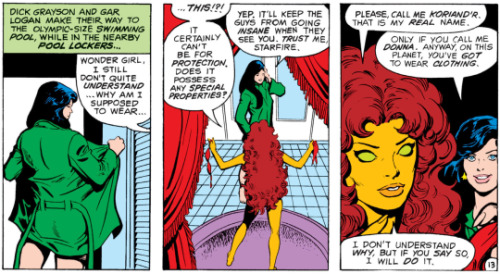

A scene where she's innocently naked in front of others and requires an explanation of why western culture finds nudity wrong and/or inappropriate?

That's there, too.

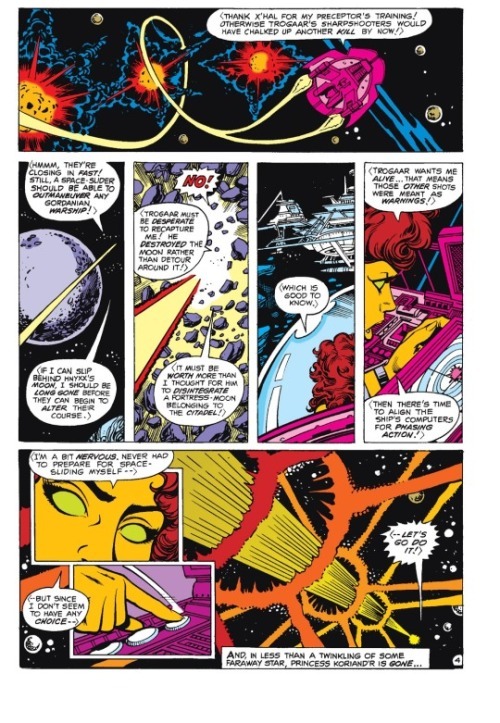

However, for all this innocence surrounding Earth culture, Koriand'r is rarely seen acting like with the innocence of a child and displays deep knowledge of a variety of subjects that are both intellectual and physical. Her innocence and naivete in social situations on Earth comes not from having the mind of a child but from a cultural dissonance. Despite suffering for years in enslavement and having no formal education (or what we as an audience would define as a formal education) she intuitively understands how to operate a starship and makes a flawless escape from her captors in a ship we as an audience may assume she has never flown before as she was a mere child when she was enslaved:

This is a skill that seems to come naturally to her and belies a greater understanding of technology than her Earth counterparts could boast of.

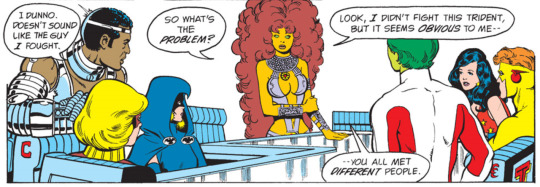

It's not just her technical knowledge that interests me, however, but her analytical skills as well. In New Teen Titans #33, during her search for answers about Dick's current whereabouts, she solves the team's problem regarding their villain of the week:

She listens to the team's descriptions of their individual conflicts with the villain Trident (previously thought to have been dead) and comes to the correct conclusion that there are multiple people masquerading as him. The scene is cut short by Tara insulting Kory's intelligence as she has interpreted Kory's beauty as being her only defining trait. Much like many comics fans, Tara has mistaken Kory's general kindness and cultural naivete for a lack of intelligence that Kory herself has never displayed. In the following scene, Kory's emotional competence is used to smooth over the situation and make clear that she won't tolerate being insulted:

While Kory is not formally educated, she is analytically minded, extremely emotionally competent, and maintains a set of skills that the other Titans had to cultivate later in life as her culture and the other cultures she grew up exposed to are more technologically advanced than Earth.

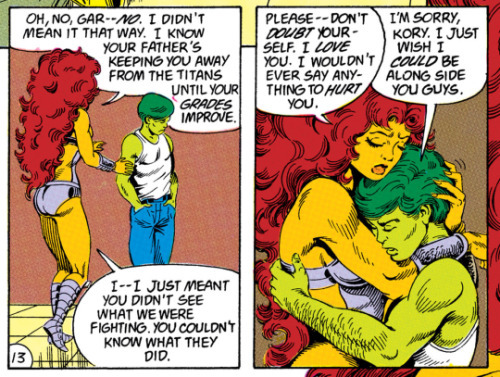

While she did fall in love with the first man she met on Earth, she didn't idolize him or love him because she thought he was the most intelligent man she had met. Kory repeatedly stands up to Dick both for herself and for what she believes he himself needs. When he lashes out at her, she tempers both his and her emotions to ensure the outcome best for both of them and when he talks down to her she refuses to let it go unnoticed:

There are countless examples of the ways in which her character has been proved to be someone who doesn't require hand holding and is equally as smart and capable (if not more) than her teammates. Her character is one that is established to have a strong sense of her own needs, wants, and personal character regardless of the situation.

In addition to her subversion of the emotional and intellectual facets of this trope, Kory also has a variety of relationships outside of her romantic relationship. Unlike the traditional Born Sexy Yesterday, Kory isn't limited to having only one relationship and her scope of the world isn't limited to just Dick Grayson and their romantic relationship - her friendships with Garfield Logan, Victor Stone, and Joey Wilson are as deep and meaningful as her relationship with Dick (this is referring to how Born Sexies are often only allowed to have a relationship/friendship with the male hero of their story and no other men, this is not discounting her deep friendships with both Donna Troy, Raven, and Lilith):

While Kory isn't a perfect subversion of this trope, she is the subversion of it that stands the test of time as a character who is both deep feeling and deeply intelligent which offsets any naivete she may have in regards to Earth and the wide and varied cultures that exist on our planet. I believe that her character represents how this trope can be subverted and how it can be eliminated from the science fiction media landscape as creators work toward creating media that is inclusive of women with actual wants, desires, and personalities.

this post is an updated and heavily edited version of a post originally uploaded here.

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

veep rewatch - 3.03

Season Three, Episode Three - Alicia

aka - The One with the Announcement

Tracie Thoms is well cast in the role of Alicia.

When Jonah runs across the street, you really get a sense of how ill-fitting his clothes are (and also how freakish they make him look as a result). His pants are at least two sizes too big.

Amy back in a skirt suit very reminiscent of her S2 outfits.

Love the behind-the-scenes quality of the scene in the Veep’s office, with Selina getting fitted while her staffers work on the speech.

Sue: Ma’am, it's Amy. She sounds uncomfortable. Like she's with a member of the public.

And now Amy in a beautifully tailored purple dress! This is not my personal favorite shade of purple (I would have preferred something a few shades darker…this is a bit too “crayola” purple for me) but the dress is super cute and it looks wonderful on Anna Chlumsky and fits her like a glove. I adore the peplum detail on the skirt and the little sleeve flaps.

Selina in another black and red outfit, in yet another episode where she wrestles with what she can say publicly versus what she actually believes. Definitely a consistent fashion theme of S3 so far.

Gary: It's like SNL is going back in time and abusing a child.

Love the ongoing balloon bit in this episode.

Kent: We need to rewrite the speech!

Dan: I can’t rewrite the rewrite, Kent. I'm still writing it!

Kent: That’s the reality, Dan. If you don't like the reality, go live in Oregon and make quilts with my mother. She could use the help.

Dan/Amy parent!watch

Amy: Do…do I take her hand?

Alicia: Yes, hold Miss Amy's hand.

Mike: Amy was born to be with kids

Amy: …Peeing is fun…!

Amy: Okay…great pee.

Dan: I wanna know who's responsible for that sketch, you cock…*sees Amy and Halo*…tail napkin. Yeah, you heard me!

Doyle: Dan. Amy.

Dan: Shit, I gotta go.

Amy: Senator Doyle.

Doyle: I have a meeting scheduled with the Vice President right now and it is "right now” right now.

Amy: Dan, you take this…right now.

Dan: What?!

I always thought this little tussle, as well as Dan and Amy’s very brief interactions with Halo, indicate that while parenting would have represented a chaotic (and comedic) learning curve for both of them…it’s not like they don’t grasp the basic reality of what it means to be responsible for another human being. Both of them willingly hold Halo’s hand. Dan cuts himself off in the middle of cursing out the SNL guy, Amy doesn’t really know what to say to a little girl but she still tries to make her feel comfortable…these are small things, but there’s an awareness, however limited, of what it means to manage small kids. Yes, Dan and Amy are dramatic and completely obsessed with their work and have limited emotional intelligence. But they are also technically functional adults who have a base level of propriety and social awareness. In contrast, during S7, Mandel’s attitude toward the idea of Dan and Amy as parents seemed to be that they would be practically criminally negligent, monstrous in their grotesque selfishness and sociopathy. Which, like, sure, I wouldn’t want Sex-Psychopath Dan anywhere near my daughter. But it doesn’t track with the earlier seasons of the show.

Ben: Because then they sound like they're the result of war.

Kent: It’s the curse of the unintended narrative.

Dan: Okay, but you still want military first?

Selina: Yes!

Dan: *grumbling* Yeah…I’ll just say them simultaneously.

The show never gets into it much, in either era—and it seems like BKD was always tragically doomed to be nothing more than a plot device—but there was always a little spark with Ben, Kent, and Dan’s dynamic. It’s not hard to imagine that the three of them, together, could have grown a very successful business in DC (…I have imagined it). Dan always works best around people who stomp on his ego and boss him around, which Ben and Kent certainly have no qualms about, but he’s also active and ambitious in a way that they aren’t, so they actually make a decent team. Also, Dan views Ben and Kent as men in a way he doesn't with Mike and Gary, which affects how he interacts with them.

Doyle is a real dick in this episode. His presumption. It is so infuriating. It reminds me of all the male senators during the Kavanaugh hearings.

Selina: Seniors are the easy vote. Child care is a principle.

Ben: Ma’am, you have plenty of principles…you just gotta pick another one.

Dan: I don’t do offended…but I am affronted that you’d even think that.

A classic Dan line.

Selina: I'll tell you what happens. They get bullied when they're little at school, and then they perpetuate the cycle by bullying me.

JLD’s face when she sees Catherine’s dress…masterful.

Amy sends Gary a great “oh shit here it comes” look right after Selina starts to blow up at Catherine.

Also JLD’s fake laughing reaction to Doyle’s “L’il Selina” line. Brilliant.

Selina: So…I’m supposed to let a bunch of dead-eyed white guys shit all over absolutely everything that I stand for?

An iconic line that is sadly even more applicable in 2020 than it was in 2014.

Selina, in a rage: I have DECIDED that I'm going to LET them dictate to me. Because that is MY decision. Do you understand that? I am LETTING them do that! Get it?

Ben: Yes, ma’am.

Selina: Right! But they do NOT own me!

Ben: They really don't, ma’am.

Selina: No, they don't! No, they don’t! *flings herself into the armchair*

Gary doesn’t do much in this episode, but he gets in some great little physical comedy bits, like trying to sneak Selina something to drink and then shying away.

Mike calling Dee a “stupid cow” opens up such a dark crack into the normally sunny Mike. Matt Walsh really nails it, though, his own horror at his words…you really feel for him, even though it is a truly awful thing to say. I wonder if it’s a line they would have given to such a sympathetic character (for Veep, comparatively) in a post Me-Too world. Like, the audience just watched Mike get married! To Kathy Najimy!

Catherine: Amy, what the fuck is happening?! Is Mike on crank?!

Amy: That’s actually the least of my worries right now. Your mom has gone quiet.

Ben to Mike: You gotta go lower! You gotta go lower than the lowest lowlife. You gotta dig and dig and dig until you get to the point where you wish you were dead. Okay? And that's base camp.

Dan: Is there any way to snap her out of this Diving Bell and Butterfly shit? She should be rehearsing my speech right now.

I mean…I am just impressed that Dan “only watches movies with Owen Wilson” Egan knows about The Diving Bell and Butterfly.

Catherine: Your entire life has been leading up to this moment. And as a result of that, my entire life has been awful.

Sarah Sutherland’s delivery of this particular line is extra great…that little waver she puts on ‘awful.’ This whole monologue is so funny and spunky!

All of the Selina/Dan interactions and miscommunications re: the speech and SNL once again foreshadow that their partnership is going to be a disaster. I appreciate how subtle the foreshadowing has been…while also undeniably consistent.

I like that after an episode of being totally shit on by Doyle, Selina manages to get a win over him at the end, manipulating him in front of Alicia and Halo because of course he can’t say no in front of potential voters. Of course, she’s also manipulating them, but it’s a nice instance where Selina’s public machinations actually pay off for her.

#veep rewatch#veep season three#alicia#I am AFFRONTED#selina meyer#dan egan#amy brookheimer#mike mclintock#ben cafferty#kent davison#jonah ryan#gary walsh#is mike on crank#veep style

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

Deadline: You’ve done this play before, so what’s different? Let’s start there.

Adam Driver: Well, I did it in college as kind of a last-year project. They picked the play for you, and cast you, and doing the play means four performances of it or something like that. You can say this about all well-written plays – four performances isn’t enough. You’re just saying the lines, basically, and making sure that they’re in the right order. We didn’t even scratch the surface. And I was also, like, 23 or something, and had no idea, really, what I was saying. I mean, I had an idea, but now I’m, sadly, the actual age of the character, so it just kind of changes your perspective in ways that I don’t think I’ve quite articulated for myself, nor felt the need to I guess, really.

This production is coming at an incredible time in your career. You were nominated for an Oscar, you have a little movie called Star Wars coming up, and between the two is Burn This. There must be something about the play that spoke to you, for you to put it into this particular spot. What was that?

Well, it was a lot of things. I’ll try to keep the answer short, but it was just a lot of stars aligning. On a technical level, there are not a lot of really great plays in a single setting, that are character driven. It has all these great ideas, all these great characters. I have this non-profit [Arts in the Armed Forces, cofounded with wife Joanne Tucker] where we perform contemporary American plays for a military audience, and there’s limited rehearsal so we try to pick material that’s urgent, and sometimes aggressive, and all the characters feel like they’re desperate to say something, and that kind of energy I was kind of missing. I hadn’t done a play in a long time, but if something came up again that felt that urgent, like you just have to get it out, that every line in the play could be yelled, because there are people that are exorcising something that, there’s just not a lot of plays that are like that. And Burn This is certainly that.

And all the themes of the play, this idea of loss and grief, you know, when it was originally written in the ‘80s, obviously this is Lanford’s AIDS play, and that idea of something beautiful just gone, and not being able to process it.

There’s also something that I think is really beautiful that’s articulated in this play really well, about work, and process. [Actress Tanya Berezin], who owns the rights to Lanford’s plays, has this great story about Lanford and Tennessee Williams, who were working together on something, and in an interview they asked Lanford, “It’s so great that you’re working with Tennessee Williams, you guys kind of have a similar writing style,” or something to that effect, and Lanford was, like, “no, no, no, no, Tennessee writes about sex, and I write about work.” The more we work on Burn This, yes, it has this beautiful theme of loss and people with their acquired family and their genetic family, but it’s also a play about artists, in the room, talking about process.

The characters are all kind of on the precipice of maybe doing something good. Anna, with her relationship with Pale and maybe the grief over Robbie, is creating her first really adult dance piece. Burton, at the end of the play, says, “I’ve never lost before,” and he’s wanting to write something epic, but doesn’t know how, and maybe Lanford is saying that it just takes so much. It has to cost you something to create something beautiful. This idea of Robbie, who was a constant workhorse, just obsessed with work and no one saw that, his family missed it, and to take that away from him is like taking away his identity.

And Pale is constantly, he works all the time, and you know, he thinks he could have been a composer and compose these tome poems, and concertos, but that didn’t go anywhere. And that’s a kind of loss. All these…this is a long answer, but there are so many different reasons why I did this play, why I wanted to live it for four or five months, you know, and just keep exploring it because all these great, well-written plays constantly are teaching you something.

Yes. Now, Pale…

It gives you something to explore, I guess, not necessarily teaches you something…

You said the characters are all on the precipice of doing something good, but at the end of the play, Pale quits his job as a restaurant manager to become a bartender. Does his trajectory fit with the others?

I don’t think he’s defeated. I don’t think him quitting is taking a step back. If anything, it’s a step forward. He’s working less hours. He’s open to the world more. He’s seeking more balance. For the first time, he’s changing everything, and that’s scary. Everybody’s on the precipice of moving, longing for a better, different life, and I think they all go for it.

You said this was Lanford Wilson’s AIDS play, and yet AIDS is never mentioned in Burn This. I’m wondering if you and the rest of the cast, and your director, explored why Lanford made that decision.

Well, I’m quoting what he said, when he was asked, is this your AIDS play he said, yes, it was. That’s a theme, but we can’t really play that. It’s something that was discussed, but it’s not an active, actionable thing to play. You can’t play an idea. But the idea of loss, of suddenly having all these beautiful men gone, and these characters not being able to process it, and so they start maybe acquiring strangers because of that loss. Loss can be a powerful bond, and that we definitely discussed.

How did this production come about for you?

I think I was approached by my agent, who kind of spearheaded this thing. If I’m remembering it correctly, and I think I am, I talked with Michael [Mayer, director] on the phone, and I was of course familiar with the play, and we talked about timing, and seeing if we were on the same page creatively. And that was kind of it. Two years ago, I think, when we first started…

So there really was no way you could have foreseen where your career would be. I’m wondering how actors make these decisions – “I need to do a play now because I just did this movie and I’m about to do this movie…”

No. Nothing is carefully planned, unfortunately. I wish I had more of a plan, but I mean, not to be all cavalier about it, but no. This was two years ago, and I was anxious to do a play again, but it wouldn’t work out, schedule-wise, for the two years. They were patient with me. I always loved this play, I love Lanford’s plays, so obviously it was important to me, and so we just kind of winged it. But no, there was no master plan, like, Now it’s important that I do something different….

When did Keri Russell come aboard? You knew her before this, I think.

Yeah. I know Matthew Rhys, her partner. I did a play with him. That was the last play I did, Look Back in Anger, so I knew Keri through Matthew. I think she came – someone else will probably know the timeline better – but I feel like last year?

So the coincidence of you two appearing in the next Star Wars, that was just…

Star Wars wasn’t a reality then. This pre-dated Star Wars, and then Keri got involved. Most of this stuff is coincidental.

[A publicist says Driver’s time for the interview is running out…]

You have to leave in a few minutes, so I need to think of something I really want to ask you. Let’s see. Well, you can’t tell me the title of the next Star Wars, can you, or…?

So you haven’t really wanted to ask me all these other questions?

I have, really. I saw the play last night and could spend another 45 minutes asking you about it and your choices, like the scene where you start crying, that first really powerful cry, and where that came from…

Are you seriously asking me this?

Sure, I’m seriously asking you this. How do you dredge that up, where does something like that come from?

You know, I don’t know. It’s not really a thing that I’ve really sat down to articulate. There’s a theme of opera, of music, that is all throughout the play, where I talk about classical music, and Vivaldi, and Puccini, and the Flying Dutchman and Senta throwing herself into the sea, and Burton wants to create something big, larger than life. These people are smaller than life, and Pale comes in and says he likes hurricanes, things that can amaze you. The other characters are people desperate to live big lives in order to feel something, and Pale comes into their world. He’s not embarrassed by having a feeling, or by expressing it.

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: The Digital Decline of David Hockney

David Hockney, “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)” (1972), acrylic paint on canvas, 2140 x 3048 mm (Lewis Collection © David Hockney, photo credit: Art Gallery of New South Wales / Jenni Carter)

LONDON — Since the passing of Lucian Freud, David Hockney has come to be regarded as the UK’s greatest living painter, his name a byword for extraordinary draftsmanship and an altogether less “passionate” style of painting. The queues snaking around the block for his retrospective at the Tate demonstrate the compelling popularity of his bright colors, the aesthetic pleasantness of his vibrant landscapes spanning his near-60-year career, and his capturing of glamorous sex and sun in the 1960s. Hockney is comparatively dispassionate, however, because his method of working is instructively informed by inquisitive intellectual and technical explorations. Tate Britain curators Chris Stephens, Andrew Wilson, and Helen Little make this clear by their choice to arrange this chronological survey around Hockney’s technical interests, theming each segment in the context of, say, abstraction, naturalism, and optical theories regarding cameras. The chronological method of display overall, however, reinforces what has been cited by many a critic and will be obvious to any visitor: Although the technical interest is in play throughout his career, the visual quality of his work undeniably suffers and declines following his 1960s peak.

Rooms One through Five cover early works of the 1960s, demonstrating Hockney’s prodigious inventiveness in his youth combined with his absolutely breathtaking draftsmanship skills. The period is compartmentalized into technical explorations thus: “Play within a Play” shows his investigations into the conventions of perspective (his reimagining of Hogarth’s famous perspectival oddity in “Kerby (After Hogarth) Useful Knowledge” of 1975 is a cocky artist’s in-joke); “Demonstrations of Versatility” covers his work at the Royal College of Art, in which Hockney selects or discards different styles, treating painting as an intellectual exercise. (He noted, “I deliberately set out to prove I could do four entirely different sorts of picture like Picasso.”) “Paintings with People In” addresses his years after the royal College of Art, visiting Los Angeles for the first time in 1964, pointing out his interest in the painting plane as a stage combined with interplay between modes of abstraction vs. representation: 1963’s “The Hypnotist” quite literally turns the picture plane into a theatre stage, across which two players traverse.

David Hockney, “Domestic Scene, Los Angeles” (1963), oil paint on canvas, 1530 x 1530 mm (Private collection © David Hockney)

David Hockney, “Model with Unfinished Self Portrait” (1977), oil paint on canvas, 1524 x 1524 mm (Private collection c/o Eykyn Maclean © David Hockney)

If all this sounds terribly detached and unemotional, that’s because Hockney’s technical skill is quite clearly completely effortless and natural — almost unbelievably so. His confidence of line and economy of modeling means that painting, for him, presents no struggle whatsoever, hence the room for complete focus on its means to explore intellectual ideas. Such formidable talent is evident in some iconic portraits, lending that distinctive 1960s coolness: “Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy” (1970–71); “American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman)” (1968). The famous LA paintings, including “A Bigger Splash” (1967) and “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)” (1972), strip all modeling down to its bare minimum, using precision of line, color choice, and composition that make it all look so still, easy, and unforced. These are presented again in terms of artistic theory — we are invited to observe their use of pictorial framing, and, yes, you probably never noticed that the sensational “A Bigger Splash” has an enormous expanse of unpainted canvas left as a framing device — but their visual punch nonetheless goes straight to the gut.

David Hockney, “A Lawn Being Sprinkled” (1967), acrylic paint on canvas, 1530 x 1530 mm (Lear Family Collection © David Hockney; photo credit: Richard Schmidt)

David Hockney, “Ossie Wearing a Fairisle Sweater” (1970), colored pencil and crayon on paper, 430 x 355 mm (private collection, London © David Hockney)

David Hockney, “Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool” (1966), acrylic paint on canvas, 1520 x 1520 mm (National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery; presented by Sir John Moores 1968 © David Hockney)

Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

It’s all too easy. Thus, one can’t help but feel that the output following this initial starburst tends toward the sloppy. When you’ve encapsulated the 1960s in a singularly iconic body of work, though, why should you bother? This was my repeated thought throughout the subsequent works. Hockney’s landscapes are increasingly abstract from the naturalistic, using freer, more expressive strokes that sometimes don’t actually cover the bare canvas. His colors similarly depart from naturalism in their loudness: all purples, yellows, and greens straight from the tube, applied to all landscapes, whether supposedly LA or East Yorkshire: They could theoretically depict anywhere. Indeed, his recent works of large scale and outdoor depictions of trees tend toward the outright naïve; gone is the precision of hand, that economy replaced with — I hate to say it — what looks an awful lot like laziness. When the final rooms bring the advent of Hockney’s digital paintings, conducted on an iPad, one wonders how much of it is for the technical interest in the “next step” in making art, and how much for the convenience of no longer bothering with the messiness of paint. Perhaps I’m being harsh to an increasingly frail artist who has already more than proven himself, but from a coldly art-historical perspective, given that the iPad lends itself particularly to the naïve tendencies in Hockney’s drawing skills, the case for it here as a method of advancing the means of making art is not exactly convincing.

David Hockney, “Red Pots in the Garden” (2000), oil paint on canvas, 1524 x 1930 mm (private collection, courtesy Guggenheim Asher Associates © David Hockney)

Photo Credit: Richard Schmidt

David Hockney, “Garden” (2015), acrylic paint on canvas, 1219 x 1828 mm (collection of the artist © David Hockney; photo Credit: Richard Schmidt)

The show’s curation at times feels forgiving toward this decline, in evidence from the first when it chooses to bend the rules of its own chronological method; the exhibition’s mantra is to show how the “roots of each new direction lay in the work that came before,” and it uses Room One to juxtapose works from the 1960s, 1970s, and one from 2014 to reinforce this cyclical idea, justifying the progression into computer generated images. Thus the brilliant “Rubber Ring Floating in a Swimming Pool” (1971) — gorgeously economic in its geometrical treatment of a plan view of a pool, just two blocks of color with a red circle — sits with 2014’s “4 Blue Stools,” a “photographic drawing” splicing together drawing and digital photos of sitters, with the Tate arguing for its technical concerns with pictorial plane and perspective. The brilliance of Hockney’s early paintings, regardless, still acts as a yardstick that his forays into fiddling with digital manipulation never come close to surpassing.

Similarly, describing Hockney’s experiments with multiscreen video works — shown here in a film recorded by nine cameras of a Yorkshire road over four seasons — as “a cubist film, showing different aspects of the same scene as perceived by a moving observer,” uses backward-facing art-historical terms to describe something we expect to be forward-looking, straining to justify the artist’s ongoing relevance in a contemporary art world which, it must be said, is already leaps ahead of him in its use of cutting-edge technology.

David Hockney, “Hollywood Hills House” (1980), oil paint, charcoal, and paper on canvas, 1524 x 3048 mm (collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; gift of Penny and Mike Winton, 1983 © David Hockney)

David Hockney, “9 Canvas Study of the Grand Canyon” (1998), oil paint on nine canvases, 1003 x 1689 mm (Richard and Carolyn Dewey © David Hockney; photo credit: Richard Schmidt)

Despite its best efforts to justify the relevance of his digital experiments, the arc of Hockney’s career remains clear, well presented, and with precision focus on his varying intellectual ideas of pictorial representation. The sheer skill of draftsmanship similarly shines through in intervals as a key element underpinning his freedom to paint naïvely if he desired; as late as the iPad paintings are charcoal pieces observing his native Yorkshire, proof that he can draw if he wants to (though frequently he doesn’t: In his recent show of 80 portraits painted in recent years at the Royal Academy, the work was embarrassing in its wanton laziness). The epic heights he reached in the 1960s, however, are so magnificent that they have apparently given him a free pass ever since.

David Hockney continues at Tate Britain (Millbank, Westminster, London) through May 29.

The post The Digital Decline of David Hockney appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2nYPD2w

via IFTTT

0 notes