Hi, I’m Natalie and welcome to Tilted Crown ! A blog aiming to explore universal issues and experiences. Topics include sport, relationships, money, career, success, psychology, education, social issues and well-being to name a few. The Tilted Crown refers to the notion that perfection does not exist and we should instead strive to achieve self acceptance.“Fix another woman’s crown, without telling the world it was crooked.”Hope you enjoy the content and if you have any suggestions send me an ask!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Can mobile phone apps support our teens’ mental health?

For some of us, being an adolescent was quite some time ago and for others, it’s been a more recent experience. Nevertheless, there is no denying that teens today are digital natives where most are “thoroughly engaged” as they would put it, with mobile phone technology. There is no doubt that a portion of society perceive mobile phone technology and even some apps in a negative light. However, what if our teens’ engagement with mobile phone apps could provide a gateway to better supporting youth mental health? A study by Grist, Porter, and Stallard (2017), estimated that the majority of children and adolescents in 2017 use a mobile phone (72% of children aged 0-11 years and 96% of those aged 12-17 years), suggesting the ease of accessibility for adolescents to utilise mobile phone apps as a resource to potentially support their mental health.

The current context of adolescent mental health is riddled with various issues of concern. A Youth Mental Health Report evaluated the mental health risks and prevalence of youth from 2012 to 2016 (Mission Australia in association with Black Dog Institute, 2016). The report noted that one in four young people are at risk of having a serious mental illness and that risk tends to increase as adolescents age. The report also highlighted that young people seek help reluctantly. This is important to consider when we already know that typically, the period of adolescence is characterised, by teens seeking a greater degree of autonomy and independence. With this in mind, it’s no surprise adolescents have a greater desire for privacy and withdrawal of help seeking behaviours such as asking others for mental health support or self-referring to a counsellor. As a result, those with higher levels of risk of mental health problems are more likely to seek help online, suggesting that stigma and fear of being judged continue to inhibit help-seeking. With this background in mind, one of the seven key policy recommendations from the report include the use of technology which provides an alternative to face-to face service delivery (Mission Australia in association with Black Dog Institute, 2016).

In addition, an interview with a NSW Department of Education (DOE) School Counsellor, (let’s use the pseudo name Rebecca), highlighted some of the benefits of the use of mental health apps noting that “It is one of the interventions (she) can recommend with the strongest uptake. Teens are glued to their phones and are more likely to engage with a strategy if they can access it on their phone,” (Rebecca, personal communication, August 11, 2020). She goes on to explain how she finds it helpful as a psychologist in the school environment to be able to offer students some resources to take away from session as “I am often not able to see them regularly.” In addition to this, when asked why she thinks teens are in favour of using apps as oppose to seeing the school counsellor she noted “I think students are often hesitant to see the school counsellor due to the stigma that can be attached to help seeking. I also think students have had negative experiences with previous counsellors which can make them less likely to reach out for help. Teens may prefer the use of apps as no one else needs to know that they are struggling. Some senior students prefer to use apps as it does not take out of their class time,” (Rebecca, personal communication, August 11, 2020).

Similarly, a study by Punukollu et al. (2020) evaluated the perceived benefits of mental health apps of which 2320 pupils (aged 11 to 14 years) and 90 teachers were included. The study identified that mental health app use benefited students and staff in terms of high pupil engagement and assisted teachers in reducing the stigma of mental health support. It is quite clear that in reality, apps have proved to be a useful resource in supporting teens’ mental health.

While Rebecca describes the usefulness of apps throughout her counselling practice, a review of mental health apps by the World Health Organisation (WHO) found more than 1536 apps for depression, but only 32 were associated with published articles raising a concern that these apps may not necessarily reflect evidence-based treatment guidelines (as cited in Grist et al., 2017; Rebecca, personal communication, August 11, 2020). Another issue in evaluating whether apps can be used as a resource to support teens’ mental health is whether teens will actually use these apps. A study by Grist, Cliffe, Denne, Croker, and Stallard (2018) aimed to identify whether young adolescent girls would actually be open to using such apps. The study administered a survey to 775 girls (aged 11–16 years) and found that while 97.4% of girls used mobile phone apps, only 6% had used apps with a focus on mental health purposes. The study also identified that out of the girls who indicated that currently had mental health symptoms, 15–17% used or were using a mental health app, with only 48.5% reporting that they would not use a mental health app. While the study did not indicate reasons as to why there was a reported lack of willingness to engage in the use of such apps, it is important to evaluate risks and barriers associated with the engagement of mental health apps. School Counsellor, Rebecca recommends that “Apps need to be clearly explained to students to ensure they are not being used as a replacement for personalised psychotherapy.” She notes that “of course, there is always a risk that students will do research on apps themselves and use ones that are not helpful or even counterproductive to improving their mental health,” (Rebecca, personal communication, August 11, 2020).

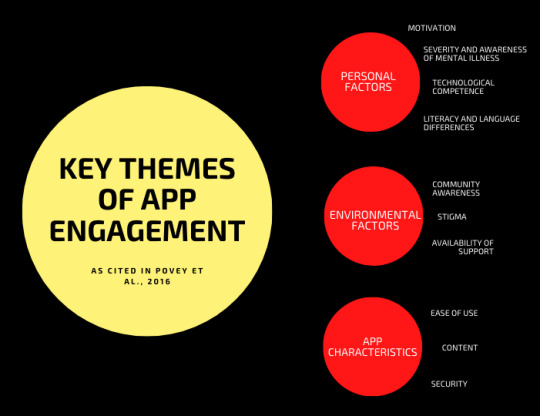

In evaluating mental health apps as a resource to support adolescent mental health. it is important to identify reasons for why teens’ may not engage with them. A study by Povey et al. (2016) evaluated the usefulness of two mental health apps; the AIMhi Stay Strong app and the ibobbly suicide prevention app which are both designed to support mental health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

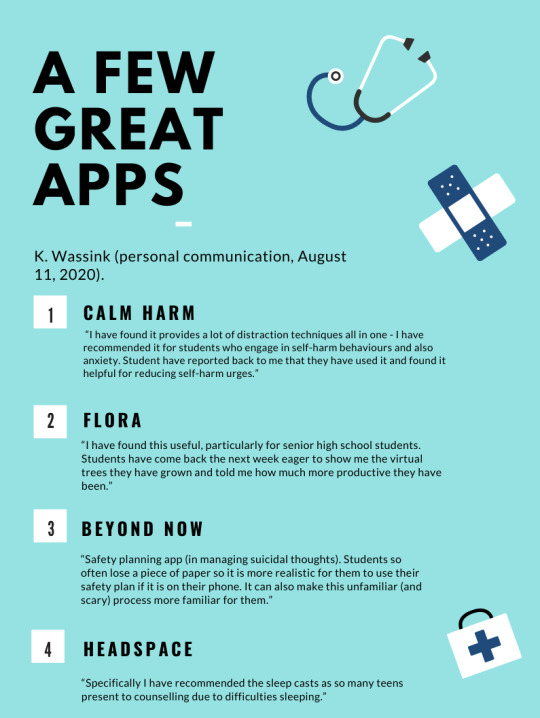

Mobile phone app developers may want to look at how to design their apps with these factors in mind to increase the engagement of adolescents and better support their mental health. While research is limited in evaluating these factors Grist et al. (2017) suggest that apps need to provide immediate support, anonymity, tailored content, lower cost and present favourable opportunities for adolescent engagement in these apps as a resource to support their mental health. Rebecca (NSW DOE School Counsellor) shared some recommendations she has of the following apps which she has found quite useful in supporting her adolescent-aged clients’ mental health (Rebecca, personal communication, August 11, 2020).

Lastly, despite studies indicating lower than expected willingness to engage with mental health apps, there is no doubt that practitioners have found apps as a useful alternative resource. In light of the current COVID-19 pandemic online tele-health platforms have been utilised in lieu of face-to-face service delivery. NSW DOE School Counsellor employees for example, have been encouraged to use an online tele-health platform for their remote counselling sessions. Given the encouragement to use tele-health services in lieu of face to face counselling sessions and the current pandemic limitations in face to face service accessibility, one may wonder, “Why not use mental health apps too?”

- Written by Natalie Shamir

References

Grist, R., Porter, J., & Stallard, P. (2017). Mental health mobile apps for preadolescents and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(5), 153–166. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uow.edu.au/10.2196/jmir.7332

Grist, R., Cliffe, B., Denne, M., Croker, A., & Stallard, P. (2018). An online survey of young adolescent girls’ use of the internet and smartphone apps for mental health support. BJPsych Open, 4(4), 302–306. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uow.edu.au/10.1192/bjo.2018.43

Mission Australia in association with Black Dog Insititute. (2016). Youth mental health report: Youth survey 2012-2016. Retrieved from http://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2017-youth-mental-health-report_mission-australia-and-black-dog-institute.pdf?sfvrsn=6

Perkins. M. (2012). Canva. https://www.canva.com/en_au/

Povey, J., Mills, P. P. J. R., Dingwall, K. M., Lowell, A., Singer, J., Rotumah, D., Bennett-Levy, J., & Nagel, T. (2016). Acceptability of mental health apps for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(3).

Punukollu, M., Leighton, E. L., Brooks, A. F., Heron, S., Mitchell, F., Regener, P., Karagiorgou, O., Bell, C., Gilmour, M., Moya, N., Sharpe, H., & Minnis, H. (2020). Safespot: An innovative app and mental health support package for scottish schools – a qualitative analysis as part of a mixed methods study. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uow.edu.au/10.1111/camh.12375

#mentalhealth#mentalhealthapps#adolescentmentalhealth#teenhealth#teenmentalhealth#apps#mentalhealthapp

0 notes

Text

The Effects of Media Violence Exposure as a Risk Factor for Aggression in Children

Media violence can be described as any portrayal of violence which may be represented in the form of traditional media (television or film) or modern media forms including video gaming and music (lyrics or video) (Desai & Jaishankar, 2008). A literature review indicates significant evidence suggesting exposure to media violence is harmful to children, in particular, with regard to facilitating aggression (Anderson et al., 2003). However, harm may not be directly attributed to or caused directly by exposure to media violence, but rather additional risk factors which will be examined in this paper (Anderson et al., 2003; Gunter, 2008). Harm to children has been measured in various studies via displays of aggressive or antisocial behaviour which may include a child’s tendency to display hostile attribution bias (HAB) (Gentile, Coyne, & Walsh, 2011). The following paper hypothesises that exposure to media violence is harmful to children and aims to evaluate the current literature and evidence in light of this view including a perspective from its critics.

Current literature has reported consistently on the effects of media violence exposure focusing typically on traditional media i.e. television and film. However, a literature review indicates that these effects can also be experienced via different forms of media. Desai and Jaishankar (2008) note that most media violence is traditionally represented via television and film though with newer technologies, it can be considered in the context of music videos and gaming too. For example, they note that music videos portraying suicides may facilitate changes in children’s attitudes that indirectly lead to antisocial behaviours. It was also suggested that music lyrics can facilitate a deep range of emotions which is not limited to communicating harmful health messages, facilitating further risk of harm for younger audiences like children who are more vulnerable than adults (as cited in Desai & Jaishankar, 2008). These examples demonstrate how media violence may be depicted in varying forms of media. In evaluating the extent of effects of harm via different forms of media, Anderson et al. (2003) suggest that violence displayed via television, films, games and music facilitates a greater likelihood of aggressive and violent behaviour in both the short and long term.

The current literature provides significant evidence suggesting exposure to violent media does harm children, which is evaluated consistently by the increased tendency to behave in an aggressive way. The Report of the Media Violence Commission by Krahé et al. (2012) consolidated various empirical studies, which described the effects of media violence on both aggression and prosocial behaviour. The report draws upon evidence provided by experimental studies where participants who were exposed to violent or nonviolent media groups. The findings demonstrated that violent media exposure causes an increased probability of aggression in the short term. They also note that many cross-sectional surveys have shown that people who are regularly exposed to more violent media have an increased probability of behaving more aggressively in real life. In addition, they make reference to various longitudinal studies which have shown that children who grew up constantly exposed to violent media, had a greater risk of behaving aggressively in real life as adolescents and adults. While causation cannot be inferred from correlation studies the experimental results suggest that exposure to violent forms of media does in fact increase the risk of aggressive behaviour. While this provides support for the hypothesis, it is worth noting that the report also provides a suggestion of caution, that no single risk factor causes a child to act aggressively. Instead, it is the accumulation of risk factors in addition to media violence exposure, that leads to an aggressive display.

Similarly, Anderson et al. (2003) consolidated various empirical evidence in an attempt to evaluate the short and long-term effects of media violence on youth. They note that the experimental research clearly demonstrates that exposure to media violence heightens the chances that youth members will behave aggressively and have aggressive thoughts in the short term. The cross-sectional surveys consistently indicate that the more frequently youth are exposed to media violence, the greater is the likelihood they will behave aggressively and have aggressive thoughts. The longitudinal research consistently shows that exposure to media violence in childhood is a predictor of subsequent aggression in adolescence and young adulthood even when many other possible influences are statistically controlled (Anderson et al., 2003).

While a literature review for this study provides consistent evidence suggesting exposure to media violence causes harm, a study by Gunter (2008) aims to critically evaluate such findings. The study does not aim to necessarily refute the findings of published literature which concludes that the causal link between media violence and aggression as well as other forms of harm to children is established. Instead, it challenges the causal link between exposure to media violence and harm in children suggesting that this effect does not occur all the time nor always to the same extent for all audiences. The paper advises caution in accepting these causal conclusions about harmful effects of media violence, instead calling for consideration of individual differences in children. They also go on to note that there is empirical evidence that the effect of violent media consumption in facilitating aggression can be explained partly by the manifestation of a personality linked media content preference. This indicates that measuring the effect of harm in this context, is complex and must consider children’s individual differences as well as additional risk factors which contribute to the extent of harm observed. The study, while offering a critical evaluation on the current literature suggesting media violence exposure facilitates aggression; does support a concluding suggestion by Krahé et al. (2012); that viewer risk factors in addition to exposure to media violence, all contribute to the likelihood of harm in children.

Further evidence for the effect of media violence can be drawn from an experiment by Josephson (1987) in evaluating the effect of television violence on boys' aggression, with consideration of teacher-rated observed characteristic aggressiveness and violence-related cues as moderators. Boys in grades 2 and 3 watched violent or non-violent TV and half the groups were later exposed to a cue associated with the violent TV program. The boys played a game of hockey where aggression was measured by naturalistic observation. Boys who were more characteristically aggressive, showed a higher level of aggression following violent TV combined with the cue than for viewing violent TV alone, which in turn caused more aggression than did the non-violent TV condition. This indicates that like Gunter (2008) noted, it is quite clear that personality linked characteristics may account for an increase in displays of aggression and therefore harm in children and highlights that these additional risk factors must be taken into consideration when evaluating the association between media violence and aggression.

A longitudinal study by Gentile et al. (2011) aimed to examine the link between consumption of media violence and increased use of physical, verbal, and relational aggression and whether hostile attribution bias (HAB) would mediate between aggression and prosocial behaviour as well as accounting for any differences between boys and girls. The study recruited 430 3rd-5th grade children who reported on their use of different forms of media including TV, movies and video games. Evidence from the study highlighted that children's consumption of media violence early in the school year significantly predicted both higher verbally and physically aggressive behaviour and lower prosocial behaviour measured by an increase in HAB later in the school year, though no significance was found for relational aggression. Interestingly, differences in effects were found between the genders of children in relation to their level of HAB and specific forms of aggression. For example, HAB mediated the effect of exposure to media violence and physical aggression where the effect was stronger for boys while HAB mediated the effect of exposure to media violence on relational aggression and was stronger for girls, though these differences were not statistically significant. Furthermore, Krahé et al. (2012) conclude that the effects of violent media exposure are consistent regardless of the type of medium, age, gender or even location of their home.

Explanations for why negative outcomes occur in children following the viewing of violent media can be derived from various theories. Observational Learning Theory for example, offers the suggestion that the likelihood that an individual will acquire an observed behaviour is increased when the model performing the behaviour is similar to or appeals to the viewer, the viewer identifies with the model, a realistic context is set and the rewarding consequences follow after the viewed behaviour (as cited in Anderson et al., 2003). In evaluating this theory in the context of media violence, the example of a child playing their favourite shooting game can be used. The media characters are appealing to children, especially if their violent actions on the screen are presented as justified and socially acceptable, for example if the game is constructed in a way where killing other characters leads to a win in the game. If the violent content is rewarded and seen as an enjoyable experience for the child, then aggression concepts will be conditioned with positive feelings leading to possible changes to attitudes about aggression, such as seeing aggression as a more acceptable response when provoked. As a result, observational learning can help to explain how children can be primed by the observed media violence which facilitates a greater likelihood of observed displays of aggression.

In addition, developmental theory offers another perspective on the susceptibility of harm suggesting that younger children, whose social scripts, schemas and beliefs are less deeply engrained, should be more sensitive to this influence (as cited in Anderson et al., 2003). In assessing the age and gender of the viewer, one study reported an inverse correlation between viewers’ age and the magnitude of the effect of TV violence on aggression and other antisocial behaviours (as cited in Anderson et al., 2003). They found that in children, the media-violence effect was largest in the youngest age group, i.e. less than 5 years old. In a concluding statement, Anderson et al. (2003) note that the existing empirical research on moderators suggests that no one is exempt from the effects of media violence; taking into considerations of empirical studies measuring differences in gender, nonaggressive personality, superior upbringing, level of social class or intelligence act as as complete protective factors.

In conclusion, it is quite clear from the current evidence that media violence exposure is a risk factor for facilitating displays of aggression and other antisocial behaviours resulting in harmful effects. However, we cannot exclude the fact that other factors may be contributing to this outcome. Not every viewer or player will be affected to the same extent, though the view that they will be affected in some way is accepted. The current literature supports the hypothesis whereby exposure to media violence is a risk factor for aggression and other displays of antisocial behaviour, a measure of the result of harm in children. However, in accepting this view, it is advised that additional risk factors including individual viewer characteristics be taken into consideration as it is the accumulation rather, of various risk factors which results in harm in children.

For further reading refer to the below...

References

Anderson, C.A., Berkowitz, L., Donnerstein, E., Huesmann, L.R., Johnson, J., Linz, D.,... Wartella, E. (2003). The influence of media violence on youth. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(3), 81-110. doi:10.1111/j.1529-1006.2003.pspi_1433.x

Desai, M., & Jaishankar, K. (2008). Impact of Media Violence on Children. Occasional Series in Criminal Justice and International Studies, 90-105. Retrieved from https://search-informit-com-au.ezproxy.une.edu.au/fullText;dn=603534293047387;res=IELHSS

Gentile, D. A., Coyne, S., & Walsh, D. A. (2011). Media violence, physical aggression, and relational aggression in school age children: A short-term longitudinal study. Aggressive Behavior, 37(2), 193-206. Retrieved from http://web.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.une.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=0b688a53-cd7b-4820-a799-598e1f3580ab%40sdc-v-sessmgr03

Gunter, B. (2008). Media violence: Is there a case for causality? American Behavioral Scientist, 51(8), 1061-1122. doi:10.1177/0002764207312007

Josephson, W. L. (1987). Television violence and children's aggression: Testing the priming, social script, and disinhibition predictions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(5), 882-890. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.5.882

Krahé, B., Berkowitz, L., Brockmeyer, J.H., Bushman, B.J., Coyne, S.M., Dill, K.E.,... Warburton, W.A. (2012). Report of the Media Violence Commission. Aggressive Behavior, 38, 335-341. doi:10.1002/ab.21443

0 notes

Text

Building growth mindsets and self-confidence in children

The concept of Mindset was first discovered by renowned Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck who describes the concept in her book “Mindset” released in 2006. Dweck proposes that there are two types of mindsets or ways of thinking, namely a fixed or growth mindset. In a fixed mindset, people tend to believe their basic qualities like intelligence or talent are fixed traits that they are born with or without and are unable to develop further with effort. However, in a growth mindset, people believe that their traits can be developed or improved with effort and perseverance.

Encouraging a growth mindset in children early on in their lives facilitates a natural tendency for resilience when facing challenges, whereby they approach problems in a trial and error manner and as an opportunity to learn something new as opposed to giving up before even trying to solve the problem. Not only does a growth mindset in children build resilience in academic and social areas, but it is an essential life skill and opportunity to expand their social and emotional learning, equipping them with necessary life skills for facing life challenges.

Often, it’s the children who have a negative self-concept, low self-esteem and poor self-confidence who benefit most from being encouraged to engage in a growth mindset perception of learning. However, even students who are naturally academically ‘gifted’ in school benefit from having a growth mindset perspective on achievement. For example, if children are led to believe they are gifted in maths, then should they make mistakes or are met with significant challenge in an area, they too can question their ability, intelligence and in turn this could have devastating effects on their self-confidence. We can best support children to have a growth mindset by shifting the value of importance we place on intelligence or talent instead, to effort and perseverance.

“Emphasizing effort gives a child a variable that they can control. They come to see themselves as in control of their success. Emphasizing natural intelligence takes it out of the child’s control, and it provides no good recipe for responding to a failure.” - Carol Dweck

The following are a few suggestions Dweck makes in her book Mindset (2006) on how to best encourage a growth mindset in children:

1. Help children understand that our brains grow and develop through hard work and practise, just like a muscle.

2. Try to avoid praising children by telling them that they are ‘smart’, ‘intelligent’ or ‘talented’, as this implies that these abilities are fixed and unchangeable.

3. Praise and encourage children instead on their effort, perseverance and actions rather than the results. An example of this could be instead of saying “great work finishing your homework” be specific and praise the level of effort the child put into it, “I’m so proud of you for trying over and over again even though the question was hard.”

4. Encourage children to try out new things and stretch their abilities often and model this yourself by trying new things such as sport or even a new recipe.

“If parents want to give their children a gift, the best thing they can do is to teach their children to love challenges, be intrigued by mistakes, enjoy effort, and keep on learning.”-Carol Dweck

From an educational perspective and in my experience teaching primary school students, I too often hear phrases along the lines of “I’m dumb” or “I can’t do maths” uttered. This highlights the need for educational resources to be directed toward building further self-confidence and self-esteem in students which enabling a growth mindset early on, provides a wonderful start to. Fortunately, schools have started looking at embedding the teaching of growth mindsets to students within resilience programs. Furthermore, teachers can easily integrate the above practical steps as suggested by Dweck in their feedback to students and general teaching style. One tool that I highly recommend utilising to help teachers, parents and anyone who wants to support a child and encourage a growth mindset, would be to have a look at a series of cartoon-based episodes called The Mojo Show on Growth Mindset by Class Dojo. These episodes are highly engaging for children within a primary school-based age range. The site also has a number of social and emotional learning concepts including perseverance, empathy, gratitude and mindfulness. The resources are easily accessible, no cost and has been designed with the support of PERTS, Stanford University's centre on learning mindsets which works to change the way students think about school to help them reach their full potential.

Growth mindsets enable students to develop, explore and improve their abilities and intelligence; they’re taught that they have the capacity to learn and grow discarding the once traditional beliefs that mistakes are bad or that failure equates to giving up when really it is just the “First Attempt In Learning (FAIL).” Afterall, the reward for success in school and life is much sweeter when we have struggled and worked hard to accomplish it.

Resources

https://ideas.classdojo.com/b/growth-mindset

https://www.perts.net/

References

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

0 notes

Text

How does social media affect your self-concept, identity and body image?

You’re on Instagram, Facebook or some other social media site and you’re inundated with ‘Kardashian’ inspired images of gorgeous women, then you look at your own profile and realise you have a lot of work to do to keep up, not just on your social media profile but on yourself, wishing you had abs instead of flabs and wondering rhetorically, “Why can’t I look like that?” If this type of thought has ever crossed your mind, then you’ve engaged in an upward appearance comparison and as a result, internalised social media’s expectations of how you ‘should look’ (Feltman & Szymanski, 2017). Unfortunately, this is one of the many types of behaviours which people often subconsciously engage in when using social media which research suggests, may distort one’s self-concept and in turn, their body image.

In 2016, 94% of worldwide internet users had at least one social media account and spent approximately 1.97 hours per day on these sites, of whom, young adults spent the most time (as cited in Feltman & Szymanski, 2017). It is important to identify what drives people to engage in frequent social media use and why it has become engrained in peoples’ daily routines. The concept of one’s identity has been described by research as an ongoing process and exploration of the self, adaptive to the social world (Miller, 2017). A study by Miller (2017) found that queer-identifying individuals with disabilities reported primarily using social networking sites to explore their identity by meeting other individuals online with shared experiences, validating their identities, engaging in a community of social support and raising political awareness of those who identify similarly. These findings suggest that the use of social media sites is deeply embedded in our drive to explore our identities and belong somewhere in the social world.

Furthermore, research by Veldhuis, Alleva, Bij, Keijer, and Konijn (2018) found that young women who appreciated their bodies more (i.e. had a positive body image) were more likely to engage in taking selfies i.e. taking photos of oneself followed by deliberately posting them on social networking sites. Women who had higher tendencies to engage in self-objectification (viewing oneself as an object and making evaluations based on appearance) were also more likely to be highly engaged in taking selfies. In contrast, women with a poorer body image or self-esteem did not engage in taking frequent selfies. This suggests that some women may be using selfie behaviours in an adaptive way, for example by posting photos and receiving positive feedback comments this can reinforce a positive self-image.

While both these studies illustrate the potential for social media to be used to positively support an individuals’ self-concept and identity exploration, it can also have aversive effects, in particular pertaining to body image perception. An experiment involving Australian women aged 17-30 years found that they experienced decreased satisfaction with their body and increased negative mood after exposure to fitness inspired images on social media (Prichard, McLachlan, Lavis, & Tiggemann, 2018). They also found that women who viewed themselves as objects (self-objectification), were more vulnerable to having poorer body satisfaction (Prichard et al., 2018). Perloff (2014) described other individual vulnerability factors in their model for social media and its impact on body image including low self-esteem, depression, thin ideal internalisation, centrality of appearance of self-worth and perfectionism. In light of these individual vulnerabilities, they note that due to the nature of accessibility of social networking sites, there are significantly more opportunities for social comparison and disordered perceptions of how one should look than were available before with conventional media.

Similarly, Feltman and Szymanski (2017) found that the more users engaged with images on Instagram, the more inclined they were to view themselves as objects and monitor their physical looks. This finding was due to internalisation of cultural standards of beauty and comparing oneself to those who have more favourable appearances (upward appearance comparison). Furthermore, a study by Vogel, Rose, Roberts, and Eckles (2014) indicated that both a higher Facebook use and temporary exposure to Facebook profiles which contained upward comparison information (i.e. profile contained engagement in highly healthy behaviours), led to lower self-esteem and poor self-evaluations in both men and women.

Unfortunately, the fusion between social media image exposure and internalisation of how one ‘should’ look can lead to a distorted self-concept and in turn negative body image.

While an internalisation of ‘thin ideals’ has shown to facilitate distorted perceptions of the self, there are ways to mitigate these effects. A study by Snapp, Hensley-choate, and Ryu (2012) evaluated whether protective factors proposed by an earlier model for body image resilience contribute to women’s overall wellness and in turn, self-concept. The study found that the following five factors contributed to a more positive body image; high family support, low levels of perceived sociocultural pressure from family, friends, and media regarding the importance of achieving a thin-and beautiful ideal, rejection of the superwoman ideal, positive physical self-concept and active coping skills. It is suggested that when engaging in social media, women should aim to be aware of these protective factors to help minimise the potential for a distorted self-concept and negative body image.

Building awareness of social media’s influence on individuals’ self-concept has also been utilised as a preventative strategy in pre-adolescent Australian children as young as 8 years (as cited in Williams, & Ricciardelli, 2014). In this literature, girls were aware that make up was used to enhance celebrities’ looks and boys identified that famous sportsmen who endorsed sugar filled sports drinks were not doing so with the aim of promoting healthy drink options. Both examples show how an awareness of social media’s disguised purposes in marketing can be encouraged in children even before it manifests itself during adolescence or early adulthood.

Lastly, research by Feltman and Szymanski (2017) has identified an association between women with stronger feminist beliefs who used Instagram and having lower rates of body-surveillance (monitoring one’s appearance), while women with lower to moderate feminist beliefs who used Instagram engaged in higher levels of body surveillance behaviour. This provides an opportunity to encourage women to engage in stronger feminist beliefs in an attempt to reduce body surveillance behaviours when using Instagram and potentially other social networking sites.

In summary, it appears that we constantly find ourselves engaging in social media, taking selfies, updating our social media profiles to not only connect to the world but to gain a validation of their identity. However, in light of the research discussed, it is important for users of social media to be aware of both the preventative strategies and potential risks associated with internalisation of thin ideals and as a result, a distortion of our self-concept. In describing this toxic manifestation, internationally famous model Kate Moss once stated, “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels” (as cited in Perloff, 2014, p. 366). The question now is, are you going to allow yourself to internalise such a ‘thin ideal’?

Reference list

Feltman, C. E., & Szymanski, D. M. (2017). Instagram use and self-objectification: The roles of internalization, comparison, appearance commentary, and feminism. Sex Roles, 78(5-6), 311-324. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.une.edu.au/10.1007/s11199-017-0796-1

Prichard, I., McLachlan, A. C., Lavis, T., & Tiggemann, M. (2018). The impact of different forms of #fitspiration imagery on body image, mood, and self-objectification among young women. Sex Roles, 78(11-12), 789-798. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.une.edu.au/10.1007/s11199-017-0830-3

Snapp, S., Hensley-choate, L., & Ryu, E. (2012). A body image resilience model for first-year college women. Sex Roles, 67(3-4), 211-221. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.une.edu.au/10.1007/s11199-012-0163-1

Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social media effects on young women's body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles, 71(11-12), 363-377. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.une.edu.au/10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6

Williams, R. J., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2014). Social media and body image concerns: Further considerations and broader perspectives. Sex Roles, 71(11-12), 389-392. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.une.edu.au/10.1007/s11199-014-0429-x

Veldhuis, J., Alleva, J. M., Bij, d. V., Keijer, M., & Konijn, E. A. (2018). Me, my selfie, and I: The relations between selfie behaviors, body image, self-objectification, and self-esteem in young women. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.une.edu.au/10.1037/ppm0000206

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Roberts, L. R., & Eckles, K. (2014). Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3(4), 206-222. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.une.edu.au/10.1037/ppm0000047

Miller, R. A. (2017). "My voice is definitely strongest in online communities": Students using social media for queer and disability identity-making. Journal of College Student Development, 58(4), 509-525. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.une.edu.au/10.1353/csd.2017.0040

#social media use#thin ideal#body icons#self-concept#self-esteem#identity#lgbt#feminism#selfie#social media#fitspiration#psychology#social psychology

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy International Women’s Day 2019 !!!

Be unapologetically yourself, independent, back yourself because no one else will, be your biggest cheerleader on the side lines, give yourself time to heal in the face of adversity, love yourself FIRST, prioritise yourself it does not mean you’re selfish, engage in continuous education, try new things, experience the highs and lows of life and be grateful for them all then get back on the horse because it doesn’t matter how slow you move so long as you don’t STOP.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thanks SBS for the shout out / mention in your article ! Glad I could contribute 😁

1 note

·

View note

Text

Psychology jokes

1. Why was oedipus so against swearing? Because he kisses his mother with that mouth

2. How much does a psychologist weigh? A milgram

3. A Freudian slip is where you say one thing but mean your mother

4. 3 Freuds walks into a bar the barman says can I see some id

5. I hate being bi polar it’s great!

6. I’m sure I have never heard of pavlov before but the name sure rang a bell

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Social Media: is it really worth the likes?

Well.. is it?

Sometime around mid 2018 I attended a talk led by a social psychology researcher (shame, but the name of whom I have now forgotten, apologies).

It certainly gave me some insight into how important of a role social media in general plays in our lives and how in particular it influences our state of mental health and well being.

Let's start by unpacking the proposed question above. Social media i.e. an online platform which enable networking between people and 'is it really worth the likes?' refers to the way in which Facebook, an example of a popular social media platform involves people posting content on their user page to which others can respond to by 'liking' it.

For argument's sake, let's presume that if any of us were to post an update on our page for example "Just got a new job!" with a few extra details informing our connections of this wonderful news, then their response in the form of clicking a 'like' button would be taken as support or congratulatory approval of our latest life achievement. Long story short, a 'like' is a good thing and can make us feel validated.

Every person has a different approach to how they manage their social media accounts AND differing purposes or motivations for doing so. It’s important to keep this in mind when we’re discussing this topic to remain as objective as possible.

Some reasons why people post content on social media:

To gain the attention of others -> popularity

To notify their closest friends and relatives of what is going on in their lives

to feel validated

In my opinion (oh i’m taking a risk here but it is my blog..) I do tend to believe that if someone subconsciously relies on the validation of the world supporting or approving their social media posts via a ‘like’ response, then this ties heavily with a person’s low self-esteem.

But hey who wants my opinion, let’s see what psychologist Emma Kenny suggests:

“There’s a very simple reason a like on social media feels so good. It gives us a high - a real, physiological high - and it’s fundamentally the reason we keep going back to it.”

“It’s a reward cycle, you get a squirt of dopamine every time you get a like or a positive response on social media.”

“If you believe that other people’s opinions are facts, your esteem will be low, your confidence will be terrible and you’ll constantly seek approval. If you’re somebody who deletes posts because they’re not getting the reinforcement, that plays into all of those negatives..”

For anyone who’s studied psychology like I currently am, Pavlov’s principal of operant conditioning (positive reinforcements) should ‘ring a bell!’

To summarise what Kenny has said above, it seems that there is this unhealthy cycle of approval or disapproval which interplay with self esteem and how we manage our content. The process goes something a little like this for some of us:

Post content

Check repeatedly how many likes it received

If above a certain threshold predetermined by ourselves we experience a feeling of satisfaction which Kenny describes as the chemical release of dopamine in our brains (which makes us feel good like when we experience a reward) OR

If below the threshold predetermined by ourselves we experience a loss of self esteem due to our content (an expression of ourselves) not being received well by our connections i.e. being ‘validated’

Option three gives our self esteem a quick boost, I say quick because once we have experienced that feeling of reward by receiving many likes we are likely to continue behaviours one and two to experience option three once again. (operant conditioning in play here).

On the other hand, one would presume that if option four some people may delete posts which did not receive as many ‘likes’ or even go to extreme lengths of asking people to ‘like’ their recent post (yes I have had people in the past ask me to like their content) which unbeknown to me at the time would have been an indication of someone who would have been craving option three!

BUT, let's bring this back to the title in question.. Social Media: is it really worth the likes?

I guess that’s a question for each individual person to answer for themselves.

My take on this is, validation should not come from outside but from within. This doesn’t happen overnight, but we need to back ourselves and not necessarily rely on others for validation. After all, is it damage to our self esteem really worth the likes?

Give this post a like if you want to see more of this sort of content ;) until then i’ll leave you with the following quote from international Drag Queen superstar RuPaul Charles:

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just want a group of really good friends together for a long weekend of camping with good scenery, a good fire, good food and good times somewhere by a lake.

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

#quotes

Quote 8

“The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go.”

-Dr.Seuss

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey all,

This is a quick introductory post.

I’m Natalie, a 24 year old who has waaaay too much time on her hands and thought it’d be better put to use via blogging.

But what will I blog about ? Well, so far I’m thinking of blogging about my interests which include equality, women’s empowerment, social issues, animal/environmental matters, psychology, education, career, sexuality and sport (soccer) to name a few. Don’t worry, nothing about politics on this blog ;)

If you have any suggestions or wants to blog about an particular content let me know !

I’ll aim to post weekly if not more :)

The next post will be covering the topic of sexuality and gender identity with some links to the education system here in Australia.

Ciao for now x

0 notes

Photo

Fave goal by Huerta!

No regard for humanity 💅🏽

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

The W league grand final and the sky blues have brought it home ! What a game to watch 😍 glad to see women’s football gaining popularity with over 8,000 in the stadium! #SydneyFC #WleagueGF #Wleague

0 notes

Text

Sometimes ya just gotta treat yo self! Which I may do so by buying this fancy clutch ! 😜

0 notes