Text

ნარკოტიკი - ნამდვილი იტალიური ტრაგედია

| ლუთერული წერილები - პიერ პაოლო პაზოლინი

თარგმანი: ლაშა კალანდაძე

მათთვის, ვინც ნარკოტიკებს არ მოიხმარს, ნარკომანი “განსხვავებულია. ამგვარად, ის ამორიცხულია ადამიანთა რიგებიდან მის მიმართ გამოვლენილი რასისტული აღშფოთების, ან შესაძლო თანაგრძნობისა და გაგების გამო. “განსხვავებულებთან” ურთიერთობაში შემწყნარებლობა და შეუწყნარებლობა ერთი და იგივე ფენომენია. თუმცა, უნდა აღინიშნოს, რომ თუ შეუწყნარებელს მიაჩნია, რომ განსხვავებულის განსხვავებულობას არავითარი ახსნა არ მოეძებნება და, შესაბამისად, ის მარტოოდენ ზიზღს იმსახურებს, შემწყნარებელი ადამიანი მეტ-ნაკლები გულწრფელობით საკუთარ თავს ხშირად ეკითხება ამ “განსხვავებულობის” მიზეზებს.

მეცა და ჩემი მკითხველიც “შემწყნარებელი” ადამიანები ვართ - განა ამაზე ორი აზრი არსებობს? შესაბამისად, ვსვამ შემდეგ კითხვას: რა არის მიზეზი იმისა, რომ ნარკოდამოკიდებული “განსხვავებული” ადამიანი ნარკოტიკს მოიხმარს? რასაკვირველია, ინდივიდუალური შემთხვევებისთვის კონკრეტული ახსნა არსებობს, სახელდობრ, ფსიქოლოგია. თუ ყოველგვარი სენტიმენტების, მორალისა და თანაგრძნობის გარეშე, ერთი კონკრეტული, ნარკოდამოკიდებული ინდივიდის განხილვასა და გაანალიზებას დავაპირებ, მისი ცხოვრების - ბავშვობის, შობლების, ნეგატიური გავლენების და ა.შ. - შესწავლა მომიწევს. ასე რომ, ისეთი მწირი ფსიქოლოგიური ცოდნაც კი, რაზეც ყოველ ინტელექტუალს მიუწვდება ხელი, გარკვეული დიაგნოზის გასაკეთებლად საკმარისია. ეს დიაგნოზი კი, სხვათა შორის, მუდამ ერთი და იგივეა: სიკვდილის სურვილი. ეს ინდივიდუალური “მიზანი”, ხშირად გაცნობიერებულიც კი, რეტროაქტიურ ნათელს ჰფენს მთლიანად საანალიზო ინდივიდუალობას, რომელიც, ამგვარად ჩამოყალიბებული, სიღრმისეულად თანმიმდევრულია: თავისთავადი, უნიკალური ერთიანობა. “განსხვავებულობა” ყოველთვის მოუხელთებელია.

მაგრამ თუ ცალკეულ, ერთ კონკრეტულ ნარკომომხმარებელთან მიმართება ვერ გვთავაზობს გამოსავალს და მას კონტექსტი არ გააჩნია (თანაც, ერთ “კერძო” შემთხვევამდე დაყვანილი უკიდურესი კონკრეტიზაცია ისტორიისთვის გამოუსადეგარია), მომხმარებელთა მასის, უფრო სწორად, ზოგადად ნარკოტიკის ფენომენის განხილვით, პირიქით, შესაძლებელია ამ მოვლენის რაციონალიზება, მისთვის ისტორიული კონტექსტის მინიჭება.

ჩემი ძალიან მწირი გამოცდილებიდან, ერთადერთი, რაც ნარკოტიკების შესახებ ვიცი, ისაა, რომ ის ყოველთვის სუროგატია, კონკრეტულად კი - კულტურის სუროგატი. ამგვარი ფორმულირება ძალიან ზერელე, ამრტივი და ზოგადია. მაგრამ ახლოდან დაკვირვებისას სირთულეებსაც ვხედავთ. როგორც წესი, ხშირად, ნარკოტიკები სიკვდილის სურვილისგან გამოწვეულ ანუ, კულტურულ სიცარიელეს ავსებენ. კულტურის შესაყვარებლად დიდი სიცოცხლისუნარიანობაა საჭირო. კულტურა სპეციფიკური, ან უკეთ - კლასობრივი გაგებით, ფლობას ნიშნავს: და არაფერს სჭირდება უფრო ძლიერი და მძვინვარე ენერგია, ვიდრე ფლობის წადილს. ვისაც ამ ენერგიის სულ მცირე დოზა მაინც არ გააჩნია, ის ნებდება. და ვინაიდან ჩვენ ზოგად ინდივიდზე ვლაპარაკობთ, რომელიც, თავისი ტრამვებისა და სენსიტიურობის გამო, სპეციფიკურ, ელიტის კულტურას მიეკუთვნება, მის გარშემო იქმნება კულტურული სიცარიელე. ამ სიცარიელის შექმნა, სხვათა შორის, თავად ამ ინდივიდსაც კი სწადია (რათა შექმნას სიკვდილის შესაძლებლობა) და მას ნარკოტიკების სუროგატით ავსებს. ნარკოტიკების ეფექტი ჰბაძავს რაციონალურ ცოდნას გამოცდილებით, რომელიც ამ ცოდნიდან “გადახრაა”, მაგრამ ამავე დროს მისი მსგავსიცაა.

ამგვარ შემთხვევებს უფრო მაღალ კულტურულ დონეზეც კი ვხვდებით: არსებობენ მწერლები და ხელოვანები, რომლებიც ნარკოტიკებს მოიხმარენ. რა მიზნით? ვფიქრობ, ისინიც სიცარიელეს ივსებენ, მაგრამ მხოლოდ კულტურულ სიცარიელეს კი არა, არამედ - აუცილებლობისა და წარმოსახვის სი���არიელეს. ასეთ შემთხვევებში, დახვეწილობას სასოწარკვეთა, ხოლო სტილს - მანერიზმი ცვლის. არავის განვსჯი. უბრალოდ ვამბობ, რომ არსებობს პერიოდები, როდესაც უდიდესი ხელოვანებიც კი ყველაზე სასოწარკვეთილი მანიერისტები არიან.

მკითხველი აუცილებლად შენიშნავდა, რომ ნარკოტიკების ფენომენზე ისე ვლაპარაკობ, როგორც ათი ან ოცი წლის წინ, მეტიც, საუკუნის წინ ვილაპარაკებდი.

მე ვგულისხმობდი ინდივიდებს, რომლებსაც კონკრეტულ და კერძო შემთხვევებში, სურდათ თავდავიწყება, “ყველაფრის უარყოფა, კულტურის ღირებულებების მიერ შემოთავაზებულ სიამოვნებებზე უარის თქმა, ფლობისა და პყრობის პრივილეგიების უკუგდება; ანუ, ფაქტობრივად, ვლაპარაკობდი ელიტის - კლასის - სპეციფიკურ კულტურაზე.

მაგრამ სიტყვა “კულტურა” აქ მხოლოდ ელიტის, კლასის სპეციფიკურ კულტურას არ ნიშნავს; ის ასევე (ამ სიტყვის მეცნიერული მნიშვნელობით - როდესაც მას ეთნოლოგები, ანთროპოლოგები, სოციოლოგები იყენებენ) მთლიანად ქვეყნის ცხოვრების წესსა და ცნობიერებას, ან ხალხის ისტორიულ ბუნებას შეესაბამება, მასთან ერთად კი, ხშირად, გაუცნობიერებელი და დაუწერელი ნორმების უსასრულო რიგებს, რაც განსაზღვრავს კიდეც ამ ხალხის ქცევას, სინამდვილის მათეულ აღქმას.

არსებობს ისტორიული ეპოქები, სადაც ნარკოტიკის ადგილი არ რჩება - უფრო სწორად, ამ სივრცეში არ გვხვდება იმ ცალკეულ ინდივიდთა “შინაგანი” კულტურული სიცარიელეები, რომლებმაც გადაწყვიტეს, ამ სიცარიელის გამო, აღსასრულს მიაშურონ და ნარკოტიკების კულტურული სუროგატით მოისწრაფონ სიცოცხლე. მაგალითად, ერთ-ერთი ასეთი პერიოდი, როდესაც ნარკოტიკებისთვის ადგილი არ მოიძებნებოდა, სულ ახლახანს და დიდი ზარ-ზეიმით განვვლეთ - სახელდობრ, კლერიკალურ-ფაშისტური რეპრესიების პერიოდი (ფაშიზმის ოცი და ქრისტიან-დემოკრატიული რეჟიმის ოცდაათი წელი). ამ პერიოდის განმავლობაში მმართველ, გლეხურ და პალეინდუსტრიულ მოსახლეობაში ფესვი გაედგა კულტურას, ან უკეთ რომ ვთქვათ, სხვადასხვა კულტურათა ქსელს, სადაც ფასეულობები და ქცევის მაგალითები სრულიად ურყევი იყო, ხოლო “ტრადიცია” - განსაკუთრებული. ვგულისხმობ იტალიას (ჩემდა სამარცხვინოდ, ჯერ კიდევ იტალიანისტი და დიალექტისტი ვარ), ანუ ქვეყანას, სადაც რევოლუცია არ მომხდარა და მმართველი კლასი რაოდენობრივად ოლიგარქიას წარმოადგენდა (ვატიკანი, ჩრდილოერთის დიდი ინდუსტრიები და სხვა დანარჩენები), ხოლო საშუალო კლასს ფინანსურად ოდნავ წელგამართული პლებეები აყალიბებდნენ. კლერიკალურ-ფაშისტური “რეპრესიები” ხალხური ფასეულობებისთვის ოფიციალური (შესაბამისად, იდიოტური, შეშლილი) მნიშვნელობის მინიჭებასა და პოლიციური მეთოდებით გავრცელებაში მდგომარეობდა.

ასეთ ისტორიულ ვითარებაში ნარკოტიკები კონკრეტულად საშუალო კლასისთვის დამახასიათებელი ფენომენი იყო - სპეციფიკურად ელიტური კლასის კულტურის სუროგატი. ჩვეულებრივ ხალხს მასთან შეხება არ ჰქონია. ხალხური “კულტურა” არც კითხვის ნიშნის ქვეშ იდგა და არც კრიზისში იყო ჩაფლული. ის არ შეცვლილა ასობით, ათასობით წლის განმავლობაში (ყველა ხალხური ტრადიცია სინამდვილეში ინტერნაციონალურია).

დღესაც კი პიაცა ნავონაზე რომ მოვხვდები და ნარკომანს დავინახავ, რომელიც მოწყენილი, საეჭვოდ დაყიალობს, მასში საშუალო კლასისთვის დამახასიათებელ უბედურებასა და უარყოფას ამოვიკთხავ ხოლმე და ვწყევლი იმ უცნობ გარემოებებს, რომლებმაც ეს კონკრეტული ადამიანი აუძილა, წიგნის კითხვის ნაცვლად ჰაშიში მოეწია. თუმცა, პიაცა ნავონაზე ასეთი, ერთობ რიტუალური შეხვედრა მაინც არაა ტიპური. გაცილებით მოსალოდნელია, ნარკომანს პიაცა დე ჩინკვეჩენტოს ან პიაცა კუატრიჩოლოს რომელიმე ბარში გადააწყდე.*

*[პაზოლინი ხაზს უსვამს იმას, რომ არაპრესტიჟულ, არაბურჟუაზიულ, ლუმპენპროლეტარიატით დასახლებულ უბნებში მომრავლდნენ ნარკომანები]

რისი თქმა მსურს ამით? იმის, რომ ნარკოტიკების ფენომენი უკანასკნელი ათი-ოცი წლის განმავლობაში რადიკალურად შეიცვალა. ის უკვემასებს და, შესაბამიასდ, ყველა სოციალურ კლასს ეხება (თუმცა, მისი მოდელი მაინც წვრილბურჟუაზიულია, სამოციანი წლების დიდი საპროტესტო მოძრაობის შედეგად მღებული).

ამგვარად, ვცხოვრობთ ეპოქაში, სადაც ნარკოტიკებისთვის სივრცე (თუ “სიცარიელე”) უსაშველოდ გაიზარდა.რატომ? იმიტომ, რომ იტალიაში განადგურდა ან განადგურების პროცესშია კულტურა ამ სიტყვის ანთროპოლოგიური მნიშვნელობით - “საყოველთაო” კულტურა. შესაბამისად, მისი ტრადიციული (ამ სიტყვის საუკეთესო გაგებით) ნიმუშები და ფასეულობები მხედველობაში უკვე აღარ მიიღება, ან მალე დადგება ამის დრო. მაგალითად, “ღმერთი” და “ოჯახი” ორი იდიოტური ფასეულობაა, როდესაც მათი სახელით მღვდლები და მორალისტები გვესაუბრებიან (ალბათ სამხედროებიც), მაგრამ ისინი თავისთავადი, თვითკმარი ფასეულობებია, როდესაც მათ მიხედვით ყალიბდება ხალხური ცხოვრების წესი (რომელიც შესაძლოა არც არის იმ დონეზე, რასაც ისტორიას ვუწოდებთ). დღეს მათ ძალა დაკარგეს. ახალგაზრდა ადამიანებს, რომ აღარაფერი ვთქვათ ნარკომომხმარებლებზე, ამ ფასეულობების სახელით ვეღარ დაელაპარაკები. მთელი კულტურის ფასეულობათა ამგვარმა დაკნინებამ ერთგვარი ანთროპოლოგიური ცვლილება გამოიწვია და ყოვლისმომცველი კრიზისი წარმოშვა. ამ პროცესში ყველა სოციალური კლასია ჩართული და ფასეულობების დაკარგვაც ყველას ეხება, თუმცა ყველაზე მეტად მაინც დაბალი კლასის ახალგაზრდები “დაიჩაგრნენ” სწორედ იმიტომ, რომ ისინი, მმართველი კლასის ახალგაზრდებთან შედარებით, გაცილებით დაცული და შეურყვნელი კულტურის მიხედვით ხოვრობდნენ.

ვხედავ, გაზეთ “უნიტაში” (1975 წლის 20 ივლისი) როგორ ცდილობენ ნარკოტიკების ფენომენის “შემოფარგვლას”, მის გამარტივებას და ერთობ კლასიკური სქემის მიხედვით მასში საზოგადოების დადანაშაულებას. სინამდვილეში ნარკოტიკების ფენომენი უფრო ვრცელი პრობლემის ნაწილია. და სწორედ ეს მეორე, უფრო ვრცელი და ყოვლისმომცველი ფენომენია მხედველობაში მისაღები, სწორედ ესაა ჭეშმარიტი, მთავარი ისტორიული ტრაგედია. ვიმეორებ, ესაა მთელი კულტურის ფასეულობების გაუქმება, რომელთა ადგილიც ახალი კულტურის ფასეულობებს ჯერ არ დაუკავებია (თუ, რა თქმა უნდა, არ დავთანხმდებით იმას, რომ კონსუმერიზმი “კულტურულად”” ვაღიაროთ. თუმცა, ეს ადაპტაცია, საუბედუროდ, ერთადერთი სწორი გამოსავალი იქნება).

ამდენად, ფასეულობების შეუქცევადი კარგვის პრობლემა, რომელიც ნარკომოხმარებ��ს უაღრესად ფართოდ გავრცელებულ პრობლემას მოიცავს, მთელ ახალგაზრდობაზე ახდენს გავლენას. (ვიმეორებ, გამონაკლისია ის ახალგაზრდები, რომლებმაც ერთადერთ შესაძლო კულტურულ გამოსავალს მიაგნეს და კომუნისტურ პარტიაში გაწევრიანდნენ.) მთლიანობაში ახალგაზრდა იტალიელები ქმნიან სოციალურს წყლულს, რომელსაც ალბათ ვეღარ ვუმკურნალებთ. ისინი ან უბედურები არიან, ან - კრიმინალები (ან კრიმინალური მენტალიტეტის მატარებე���ნი); ან ექსტრემისტები არიან, ან - კონფორმისტები. ამ ყველაფრის მასშტაბები ჯერ კიდევ არ ვიცით. ახალგაზრდების ურყევი გადაწყვეტილებაა, იცხოვრონ ამ სიცარიელითა და დანაკარგით, გადაიქცნენ მიუწვდომელ არსებებად;ანუ, უარი თქვან ყველაფერზე, რისი სახელითაც მათთან საუბარი შეიძლება (სუბკულტურული თემების გამოკლებით). იმის გამო, რომ ამ გადაწყვეტილების სათავეში ნარკოტიკების მომხმარებლები გვევლინებიან, არანაირი სათუთი გრძნობები არ გამაჩნია მათ მიმართ. პირიქით, ძლიერ უარყოფით წინასწარგანწყობას ვგრძნობ მათდამი: ერთ მხარეს მათი შანტაჟი და მუქარაა, რომ განახორციელებენ თავიანთ მითოლოგიზებულ, სუბკულტურულ აქტს, მეორე მხარეს კი ჩემი პირადი დამოკიდებულება: ის, რომ ვერ ვიტან დანებებას, გაქცევას, რაღაც გაურკვევლისთვის თავის შეფარებას.

სწორედ ამიტომ, როცა პანელამ მსუბუქი ნარკოტიკების დეკრიმინალიზაციას მხარი დაუჭირა და “დაუმორჩილებლობის” ჟესტი გააკეთა, მაშინვე მინიმუმ ათი სხვა მიზეზი მომაფიქრდა ანალოგიური დაუმორჩილებლობის ჟესტის გასაკეთებლად და პანელასთვის მემარცხენეობაში გადასასწრებად. ოდესმე დავასახელებ ამ მიზეზებს. მანამდე კი უნდა ვთქვა: როგორც იქნა, მივხვდი, რატომაა ნარკოტიკების (მათ შორის ძლიერი ნარკოტიკებისაც) დეკრიმინალიზაციის მოთხოვნა ნამდვილი შემწყნარებლობისთვის ბრძოლის ცენტრალური, არაპერიფერიული ასპექტი. რატომ?

თითქმის ყველა ინტელექტუალი დარწმუნებულია, რომ იტალიაში ვითარება გაუმჯობესდა. სინამდვილეში, იტალია საშინელი ადგილია; ამის მისახვედრად, ქვეყნის ფარგლებს გარეთ რამდენიმე დღით გასვლას კი საკმარისია. ბარსელონადან დაბრუნების შემდეგ (ქალაქი, რომელის საშინლად გაფორიაქებს, სადაც წარსული სულისშემხუთავია) ცხადად დავინახე იმ უფსკრულის მასშტაბი, რომელშიც იტალიელები მატლებივით ფუსფუსებენ. უპირველეს ყოვლისა, სწორედ ახალგაზრდები მყავს მხედველობაში. შესაბამისად, თუ რომელიმე ახალგაზრდა თავის თავში აღმოაჩენს სიკვდილის სურვილს, გნებავთ გაუცნობიერებლად, გნებავთ სუბკულტურული მითოლოგიზების მეშვეობით, როგორ მოახერხებს მის შეჩერებას საზოგადოება, რომელიც მას ასეთ საზარელ და ტრაგიკულ სპექტაკლს სთავაზობს?

“კორიერე დელა სერა”, 1975 წლის 24 ივლისი.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

... "სანამ "განსხვავებული" თავისი "განსხვავებულობის დუმილში" ცხოვრობს, სანამ ჩაკეტილია მისთვის გამოყოფილ "მენტალურ გეტოში", ყველაფერი კარგადაა, ყველა კმაყოფილია იმ მოწყალებით, მისთვისრომ გაიღეს. მაგრამ, თუ საკუთარ "განსხვავებულ" გამოცდილებაზე კრინტს დაძრავ ან გაბედავ და შენი "განსხვავებული" გამოცდილებით "შეფერილ" სიტყვებს წარმოთქვამ, ლინჩის წესით გაგასამართლებენ, ზუსტად ისე, როგორც ბნელ კლერიკალურ-ფაშისტურ ეპოქაში. ყველაზე ვულგარული ზიზღით, სკოლის მოწაფისთვის დამახასიათებელი დაუნდობელი ხუმრობებითა და სასტიკი შეურაცხყოფით გარიყულთა, შერცხვენილთა რიგებში მიგიჩენენ ადგილს." ...

პიერ პაოლო პაზოლინი

ამონარიდი თარგმანების კრებულიდან "ლუთერული წერილები". მესამე პარაგრაფი - "ისევ შენი პედაგოგის შესახებ"

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Audio

[Intro] x4

Now we're spitting blood, spitting blood

Like the golden sun god, golden sun god

[Verse 1]

I was born into plastic fame

Read his tattoo

But it don't matter, were all in the same

Ship sailing to what we hold as true

I got the star of David hanging over me

But oh mother Mary I find it hard to believe

That some ones hands no different to mine

Could be hung on a wall, held as divine

[Refrain] x2

We are so happy, happy to see

All of our children will run blind and free

[Verse 2]

Across concrete fields of broken glass

With five-year-olds having heart attacks

You fed 'em to well on TV

Cut me, I won't even bleed

My blood's as lazy as the mums and dads

Whose fantastic mundane can't all be bad

So lets just keep eating more

More, more, more, more and more

And then we all go throw up on the poor

[Bridge]

Outside I’m lying, inside I’m dead

The tears in my eyes fall from books I have read

If I could talk to you and only speak the truth

All this wolf noise wouldn't start calling now

When I talk to you, when I talk to you

When I talk to you, when I talk to you

When I talk to you, when I talk to you

When I talk to you, when I talk to you

When I talk to you!

[Refrain] x2

[Outro] x2

Now we're spitting blood

Like the golden sun god

1 note

·

View note

Audio

(This ships set sail

Sail on you and me

This ships set sail

I just wanted to be free

So maybe we will fail

Fail to not see

Maybe we will fail

But at least we will be free)

You stand so holy

Nah don’t sit down

Join the feet all marching

Across the ground

This place so lonely

But nah don’t settle down

Just hear the beat drown over

All this lonesome sound

It’s a sad song that makes a man put

Money before life

A sad song that puts a man for sale

A sad song that make a man put

Money before life

How many asses are you gonna have to sell

We were born as animals

We were born as animals and we bros

But you

Put suits on animals

You try to put suits on animals but we bros

We bros you lost man

We bros so long

Put away your guns man

And sing this song

We bros you lost man

We bros so long

Put away your guns man

And sing this song

We bros you lost man

We bros so long

Put away your guns man

And sing this song

We bros you lost man

We bros so long

Put away your guns man

And I said the mountain won't go falling

If you're still willing to climb

But when the mountain goes falling

True riches you will find

Nah we were born as animals

Born as animals and we bros

But you

Put suits on animals

You try to put suits on animals but we bros

We bros you lost man!

We bros so long!

Put away your guns man!

And sing this song!

We bros you lost man!

We bros so long!

Put away your guns man!

And sing this song!

We bros you lost man!

We bros so long!

Put away your guns man!

And sing this song!

We bros you lost man!

We bros so long!

Put away your guns man!

And sing this song!

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

We bros

0 notes

Text

infrarealist manifesto

-The death of the swan, the last song of the swan, the last song of the black swan, ARE NOT in the Bolshoi but in the pain and the unbearable beauty of the streets.

-A rainbow that begins at a B movie and ends with a factory on strike.

-That amnesia never kisses us on the mouth. That it never kisses us.

-We dreamt of utopia and we wake up screaming.

-A poor lonely cowherd who goes back home, that is the wonder.

*

Making new sensations appear –Subverting the everyday

O.K.

ABANDON EVERYTHING, AGAIN

HIT THE ROAD

http://altarpiece.blogspot.com/2009/06/first-infrarealist-manifesto-english.html?m=1

0 notes

Text

ყინვა-ამურისგან სახე რად დაგწვია,

ქარს რად ედევნები ველად მოარული?

0 notes

Text

"Isn't it that one wants a thing to be as factual as possible, and yet at the same time as deeply suggestive or deeply unlocking of areas of sensation other than simple illustrating of the object that you set out to do? Isn't that what art is all about?"

1 note

·

View note

Text

Amerigo Vespucci landing on the South American coast in 1497. Before him, seductively lying on a hammock, is "America." Behind her some cannibals are roasting human remains. Design by Jan van der Straet and engraved by Theodore Galle. 1589.

0 notes

Text

The common fate of Europe's witches and Europe's colonial subjects is further demonstrated by the growing exchange, in the course of the 17th century, between the ideology of witchcraft and the racist ideology that developed on the soil of the conquest and the slave trade. The Devil was portrayed as a black man and black people were increasingly treated like devils, so that "devil worship and diabolical interventions [became] the most widely reported aspect of the non-European societies the slave traders encountered". From Lapps to Samoyed, to the Hottentots and indoneians... there was no society" - Anthony Barker writes - "which was not labeled by some

Englishman as actively under diabolical influence". Just as in Europe, the trademark of diabolism was an abnormal lust and sexual potency. The Devil was often portrayed as possessing two penises, while tales of brutish sexual practices and inordinate fondness for music and dancing became staples in the reports of missionaries and travellers to the "New World."

16th-century representation of Caribbean Indians as devils from Tobias George Smollet [compiler], "A Compendium of Authentic and Entertaining Voyages, Digested in a Chronological Series...", 1976.

According to historian Brian Easlea, this systematic exaggeration of black sexual potency betrays the anxiety that white men of property felt towards their own sexuality; presumably, white upper-class males feared the competition of the people they enslaved, whom they saw as closer to nature, because they felt sexually inadequate due to excessive doses of self-control and prudential reasoning. The definition of blackness and femleness as marks of bestiality and irrationality conformed with the exclussion of women and men in the collonies from the social contract implicit in the wage, and the consequent naturalization of their exploitation.

#Tobias George Smollet#Racism#Witchcraft#Exploitation#Primitive accumulation#Caliban and the Witch#Silvia Federici

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Witches Sabbath.

This was the first and most famous of a series of engravings the German artist Hans Baldung produced, starting in 1510, pornographically exploiting the female body under the guise of denunciation.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Cockaigne" წარმოადგენდა, დეკარტისეულ რაციონალურ სულსა და მექანიკურ სხეულს შორის გაჩაღებულ ომში, დამარცხებული სულის სიმბოლოს.

F. Graus (1967) discusses the difference between the medieval concept of "Wonderland" and the modern concept of Utopia, arguing that:

In modern times the basic idea of the constructability of the ideal world means that Utopia must be populated with ideal beings who have rid themselves of their faults. The inhabitants of Utopia are marked by their justice and intelligence. The utopian visions of the Middle Ages on the other hand start from man as he is and seek to fulfill his present desires.

In "Cockaigne", for instance, there is food and drink in abundance, there is no desire to "nourish oneself" sensibly, but only to gluttonize, just as one had longed to do in everyday life.

In this Cockaigne... there is also the fountain of youth, which men and women step into on one side to emerge at the other side as handsome youths and girls. Then the story proceeds with its "Wishing Table" attitude, which so well reflects the simple view of an ideal life.

In other words, the ideal of Cockaigne does not embody any rational scheme or notion of "progress", but is much more "concrete", "leaning heavily on the village setting," and "depicts a state of perfection which in modern times knows no further advance.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Just as capital is compelled continually to reproduce itself, so its culture is one of unending anticipation. What-is-to-come, what-is-to-be-gained empties what-is."

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE PRIMITIVE AND THE PROFESSIONAL

Art-historically the word primitive has been used in three different ways: to designate art (before Raphael) on the borderline between the medieval and modern Renaissance traditions; to label the trophies and “curiosities” taken from the colonies (Africa, Caribbean, South Pacific) when brought back to the imperial metropolis; and lastly to put in its place the art of men and women from the working classes — proletarian, peasant, petit-bourgeois — who did not leave their class by becoming professional artists. According to all three usages of the word, originating in the last century when the confidence of the European ruling class was at its height, the superiority of the main European tradition of secular art, serving that same “civilised” ruling class, was assured.

Most professional artists begin their training when young. Most primitive artists of the third category come to painting or sculpture in middle or even old age. Their art usually derives from considerable personal experience and, indeed, is often provoked as a result of the profundity or intensity of that experience. Yet artistically their art is seen as naïve, that is, inexperienced. It is the significance of this contradiction that we need to understand. Does it actually exist, and if so, what does it mean? To talk of the dedication of the primitive artist, his patience and his application amounting to a kind of skill, does not altogether answer the question.

The primitive is defined as the non-professional. The category of the professional artist, as distinct from the master craftsman, was not clear until the 17th century. (And in some places, especially in Eastern Europe, not until the 19th century.) The distinction between profession and craft is at first difficult to make, yet it is of great importance. The craftsman survives so long as the standards for judging his work are shared by different classes. The professional appears when it is necessary for the craftsman to leave his class and “emigrate” to the ruling class, whose standards of judgement are different.

The relationship of the professional artist to the class that ruled or aspired to rule was complicated, various and should not be simplified. His training however — and it was his training which made him a professional — taught him a set of conventional skills. That is to say, he became skilled in using a set of conventions. Conventions of composition, drawing, perspective, chiaroscuro, anatomy, poses, symbolism. And these conventions corresponded so closely to the social experience — or anyway to the social manners — of the class he was serving, that they were not even seen as conventions but were thought of as the only way of recording and preserving eternal truths. Yet to the other social classes such professional painting appeared to be so remote from their own experience, that they saw it as a mere social convention, a mere accoutrement of the class that ruled over them: which is why in moments of revolt, painting and sculpture were often destroyed.

During the 19th century certain artists, for consciously social or political reasons, tried to extend the professional tradition of painting, so that it might express the experience of other classes (for example, Millet, Courbet, Van Gogh). Their personal struggles, their failures, and the opposition they met with, were a measure of the enormity of the undertaking. Perhaps one pedestrian example will give some idea of the extent of the difficulties involved. Consider Ford Madox Brown’s well-known painting of Work in Manchester Art Gallery. It shows a team of navvies, with passers-by and bystanders, working on a sidewalk. It took the painter ten years to complete, and it is, at one level, extremely accurate. But it looks like a religious scene — the Mounting of the Cross, or the Calling of the Disciples? (One searches for the figure of Christ.) Some would argue that this is because the artist’s attitude to his subject was ambivalent. I would argue that the optic of all the visual means he was using with such care, pre-empted the possibility of depicting manual work, as the main subject of a painting, in any but a mythological or symbolic way.

The crisis provoked by those who tried to extend the area of experience to which painting might be open — and by the end of the century this also included the Impressionists — continued into the 20th century. But its terms were reversed. The tradition was indeed dismantled. Yet, except for the introduction of the Unconscious, the area of experience from which most European artists drew remained surprisingly unchanged. Consequently, most of the serious art of the period dealt either with the experience of various kinds of isolation, or with the narrow experience of painting itself. The latter produced painting about painting, abstract art.

One of the reasons why the potential freedom gained by the dismantling of the tradition was not used, may be to do with the way painters were still trained. In the academies and art schools they first learnt those very conventions which were being dismantled. This was because no other professional body of knowledge existed to be taught. And this is still, more or less, true today. No other professionalism exists.

Recently, corporate capitalism, having grounds to believe itself triumphant, has begun to adopt abstract art. And the adoption is proving easy. Diagrams of aesthetic power lend themselves to becoming emblems of economic power. In the process almost all lived experience has been eliminated from the image. Thus, the extreme of abstract art demonstrates, as an epilogue, the original problematic of professional art: an art in reality concerned with a selective, very reduced area of experience, which nevertheless claims to be universal.

Something like this overview of traditional art (and the overview is of course only partial, there are other things to be said on other occasions) may help us to answer the questions about primitive art.

The first primitive artists appeared during the second half of the 19th century. They appeared after professional art had first questioned its own conventional purposes. The notorious Salon des Refusés was held in 1863. This exhibition was not of course the reason for their appearance. What helped to make their appearance possible were universal primary education (paper, pencils, ink), the spread of popular journalism, a new geographical mobility due to the railways, the stimulus of clearer class consciousness. Perhaps also the example of the bohemian professional artist had its effect. The bohemian chose to live in a way which defied normal class divisions, and his lifestyle, if not his work, tended to suggest that art could come from any class.

Among the first were the Douanier Rousseau (1844-1910) and the Facteur Cheval (1836-1924). These men, when their art eventually became known, were nevertheless designated by their other work — the Customs-Man-Rousseau, the Postman-Cheval. This makes it clear — as does also the term Sunday painter — that their “art” is an eccentricity. They were treated as cultural “sports”, not because of their class origin, but because they refused, or were ignorant of, the fact that all artistic expression has traditionally to undergo a class transformation. In this way they were quite distinct from amateurs — most, but not all of whom, came from the cultured classes; amateurs, by definition, followed, with less rigour, the example of the professionals.

The primitive begins alone; he inherits no practice. Because of this the term primitive may appear at first to be justified. He does not use the pictorial grammar of the tradition — hence he is ungrammatical. He has not learnt the technical skills which have evolved with the conventions — hence he is clumsy. When he discovers on his own a solution to a pictorial problem, he often uses it many times — hence he is naïve. But then one has to ask: why does he refuse the tradition? And the answer is only partly that he was born far away from that tradition. The effort necessary to begin painting or sculpting, in the social context in which he finds himself, is so great that it could well include visiting the museums. But it never does, at least at the beginning. Why? Because he knows already that his own lived experience which is forcing him to make art has no place in that tradition. How does he know this without having visited the museums? He knows it because his whole experience is one of being excluded from the exercise of power in his society, and he realises from the compulsion he now feels, that art too has a kind of power. The will of primitives derives from faith in their own experience and a profound scepticism about society as they have found it. This is true even of such an amiable artist as Grandma Moses.

I hope I have now made clearer why the “clumsiness” of primitive art is the precondition of its eloquence. What it is saying could never be said with any ready-made skills. For what it is saying was never meant, according to the cultural class system, to be said.

1 note

·

View note

Text

USES OF PHOTOGRAPHY

For Susan Sontag

I want to write down some of my responses to Susan Sontag’s book On Photography. All the quotations I will use are from her text. The thoughts are sometimes my own, but all originate in the experience of reading her book.

The camera was invented by Fox Talbot in 1839. Within a mere 30 years of its invention as a gadget for an elite, photography was being used for police filing, war reporting, military reconnaissance, pornography, encyclopedic documentation, family albums, postcards, anthropological records (often, as with the Indians in the United States, accompanied by genocide), sentimental moralising, inquisitive probing (the wrongly named “candid camera”): aesthetic effects, news reporting and formal portraiture. The first cheap popular camera was put on the market, a little later, in 1888. The speed with which the possible uses of photography were seized upon is surely an indication of photography’s profound, central applicability to industrial capitalism. Marx came of age the year of the camera’s invention.

It was not, however, until the 20th century and the period between the two world wars that the photograph became the dominant and most “natural” way of referring to appearances. It was then that it replaced the world as immediate testimony. It was the period when photography was thought of as being most transparent, offering direct access to the real: the period of the great witnessing masters of the medium like Paul Strand and Walker Evans. It was, in the capitalist countries, the freest moment of photography: it had been liberated from the limitations of fine art, and it had become a public medium which could be used democratically.

Yet the moment was brief. The very “truthfulness” of the new medium encouraged its deliberate use as a means of propaganda. The Nazis were among the first to use systematic photographic propaganda.

“Photographs are perhaps the most mysterious of all the objects that make up and thicken the environment we recognise as modern. Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.”

In the first period of its existence photography offered a new technical opportunity; it was an implement. Now, instead of offering new choices, its usage and its “reading” were becoming habitual, an unexamined part of modern perception itself. Many developments contributed to this transformation. The new film industry. The invention of the lightweight camera — so that the taking of a photograph ceased to be a ritual and became a “reflex”. The discovery of photojournalism — whereby the text follows the pictures instead of vice versa. The emergence of advertising as a crucial economic force.

“Through photographs, the world becomes a series of unrelated, free-standing particles; and history, past and present, a set of anecdotes and faits divers. The camera makes reality atomic, manageable, and opaque. It is a view of the world which denies interconnectedness, continuity, but which confers on each moment the character of a mystery.”

The first mass-media magazine was started in the United States in 1936. At least two things were prophetic about the launching of Life, the prophecies to be fully realised in the postwar television age. The new picture magazine was financed not by its sales, but by the advertising it carried. A third of its images were devoted to publicity. The second prophecy lay in its title. This is ambiguous. It may mean that the pictures inside are about life. Yet it seems to promise more: that these pictures are life. The first photograph in the first number played on this ambiguity. It showed a newborn baby. The caption underneath read: “Life begins …”

What served in place of the photograph; before the camera’s invention? The expected answer is the engraving, the drawing, the painting. The more revealing answer might be: memory. What photographs do out there in space was previously done within reflection.

“Proust somewhat misconstrues that photographs are, not so much an instrument of memory as an invention of it or a replacement.”

Unlike any other visual image, a photograph is not a rendering, an imitation or an interpretation of its subject, but actually a trace of it. No painting or drawing, however naturalist, belongs to its subject in the way that a photograph does.

“A photograph is not only an image (as a painting is an image), an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stencilled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask.”

Human visual perception is a far more complex and selective process than that by which a film records. Nevertheless the camera lens and the eye both register images — because of their sensitivity to light — at great speed and in the face of an immediate event. What the camera does, however, and what the eye in itself can never do, is to fix the appearance of that event. It removes its appearance from the flow of appearances and it preserves it, not perhaps for ever but for as long as the film exists. The essential character of this preservation is not dependent upon the image being static; unedited film rushes preserve in essentially the same way. The camera saves a set of appearances from the otherwise inevitable supercession of further appearances. It holds them unchanging. And before the invention of the camera nothing could do this, except, in the mind’s eye, the faculty of memory.

I am not saying that memory is a kind of film. That is a banal simile. From the comparison film/memory we learn nothing about the latter. What we learn is how strange and unprecedented was the procedure of photography.

Yet, unlike memory, photographs do not in themselves preserve meaning. They offer appearances — with all the credibility and gravity we normally lend to appearances — prised away from their meaning. Meaning is the result of understanding functions. “And functioning takes place in time, and must be explained in time. Only that which narrates can make us understand.” Photographs in themselves do not narrate. Photographs preserve instant appearances. Habit now protects us against the shock involved in such preservation. Compare the exposure time for a film with the life of the print made, and let us assume that the print only lasts ten years: the ratio for an average modern photograph would be approximately 20,000,000,000: 1. Perhaps that can serve as a reminder of the violence of the fission whereby appearances are separated by the camera from their function.

We must now distinguish between two quite distinct uses of photography. There are photographs which belong to private experience and there are those which are used publicly. The private photograph — the portrait of a mother, a picture of a daughter, a group photo of one’s own team — is appreciated and read in a context which is continuous with that from which the camera removed it. (The violence of the removal is sometimes felt as incredulousness: “Was that really Dad?”) Nevertheless such a photograph remains surrounded by the meaning from which it was severed. A mechanical device, the camera has been used as an instrument to contribute to a living memory. The photograph is a memento from a life being lived.

The contemporary public photograph usually presents an event, a seized set of appearances, which has nothing to do with us, its readers, or with the original meaning of the event. It offers information, but information severed from all lived experience. If the public photograph contributes to a memory, it is to the memory of an unknowable and total stranger. The violence is expressed in that strangeness. It records an instant sight about which this stranger has shouted: Look!

Who is the stranger? One might answer: the photographer. Yet if one considers the entire use-system of photographed images, the answer of “the photographer” is clearly inadequate. Nor can one reply: those who use the photographs. It is because the photographs carry no certain meaning in themselves, because they are like images in the memory of a total stranger, that they lend themselves to any use.

Daumier’s famous cartoon of Nadar in his balloon suggests an answer. Nadar is travelling through the sky above Paris — the wind has blown off his hat — and he is photographing with his camera the city and its people below.

Has the camera replaced the eye of God? The decline of religion corresponds with the rise of the photograph. Has the culture of capitalism telescoped God into photography? The transformation would not be as surprising as it may at first seem.

The faculty of memory led men everywhere to ask whether, just as they themselves could preserve certain events from oblivion, there might not be other eyes noting and recording otherwise unwitnessed events. Such eyes they then accredited to their ancestors, to spirits, to gods or to their single deity. What was seen by this supernatural eye was inseparably linked with the principle of justice. It was possible to escape the justice of men, but not this higher justice from which nothing or little could be hidden.

Memory implies a certain act of redemption. What is remembered has been saved from nothingness. What is forgotten has been abandoned. If all events are seen, instantaneously, outside time, by a supernatural eye, the distinction between remembering and forgetting is transformed into an act of judgment, into the rendering of justice, whereby recognition is close to being remembered, and condemnation is close to being forgotten. Such a presentiment, extracted from man’s long, painful experience of time, is to be found in varying forms in almost every culture and religion, and, very clearly, in Christianity.

At first, the secularisation of the capitalist world during the 19th century elided the judgment of God into the judgment of History in the name of Progress. Democracy and Science became the agents of such a judgment. And for a brief moment, photography, as we have seen, was considered to be an aid to these agents. It is still to this historical moment that photography owes its ethical reputation as Truth.

During the second half of the 20th century the judgment of history has been abandoned by all except the underprivileged and dispossessed. The industrialised, “developed” world, terrified of the past, blind to the future, lives within an opportunism which has emptied the principle of justice of all credibility. Such opportunism turns everything — nature, history, suffering, other people, catastrophes, sport, sex, politics — into spectacle. And the implement used to do this — until the act becomes so habitual that the conditioned imagination may do it alone — is the camera.

“Our very sense of situation is now articulated by the camera’s interventions. The omnipresence of cameras persuasively suggests that time consists of interesting events, events worth photographing. This, in turn, makes it easy to feel that any event, once underway, and whatever its moral character, should be allowed to complete itself — so that something else can be brought into the world, the photograph.”

The spectacle creates an eternal present of immediate expectation: memory ceases to be necessary or desirable. With the loss of memory the continuities of meaning and judgment are also lost to us. The camera relieves us of the burden of memory. It surveys us like God, and it surveys for us. Yet no other god has been so cynical, for the camera records in order to forget.

Susan Sontag locates this god very clearly in history. He is the god of monopoly capitalism.

“A capitalist society requires a culture based on images. It needs to furnish vast amounts of entertainment in order to stimulate buying and anaesthetise the injuries of class, race and sex. And it needs to gather unlimited amounts of information, the better to exploit the natural resources, increase productivity, keep order, make war, give jobs to bureaucrats. The camera’s twin capacities, to subjectivise reality and to objectify it, ideally serve these needs and strengthen them. Cameras define reality in the two ways essential to the workings of an advanced industrial society: as a spectacle (for masses) and as an object of surveillance (for rulers). The production of images also furnishes a ruling ideology. Social change is replaced by a change in images.”

Her theory of the current use of photographs leads one to ask whether photography might serve a different function. Is there an alternative photographic practice? The question should not be answered naively. Today no alternative professional practice (if one thinks of the profession of photographer) is possible. The system can accommodate any photograph. Yet it may be possible to begin to use photographs according to a practice addressed to an alternative future. This future is a hope which we need now, if we are to maintain a struggle, a resistance, against the societies and culture of capitalism.

Photographs have often been used as a radical weapon in posters, newspapers, pamphlets, and so on. I do not wish to belittle the value of such agitational publishing. Yet the current systematic public use of photography needs to be challenged, not simply by turning round like a cannon and aiming it at different targets, but by changing its practice. How?

We need to return to the distinction I made between the private and public uses of photography. In the private use of photography, the context of the instant recorded is preserved so that the photograph lives in an ongoing continuity. (If you have a photograph of Peter on your wall, you are not likely to forget what Peter means to you.) The public photograph, by contrast, is torn from its context, and becomes a dead object which, exactly because it is dead, lends itself to any arbitrary use.

In the most famous photographic exhibition ever organised, The Family of Man (put together by Edward Steichen in 1955), photographs from all over the world were presented as though they formed a universal family album. Steichen’s intuition was absolutely correct: the private use of photographs can be exemplary for their public use. Unfortunately the shortcut he took in treating the existing class-divided world as if it were a family, inevitably made the whole exhibition, not necessarily each picture, sentimental and complacent. The truth is that most photographs taken of people are about suffering, and most of that suffering is man-made.

“One’s first encounter,” writes Susan Sontag, “with the photographic inventory of ultimate horror is a kind of revelation, the prototypically modern revelation: a negative epiphany. For me, it was photographs of Bergen-Belsen and Dachau which I came across by chance in a bookstore in Santa Monica in July 1945. Nothing I have seen — in photographs or in real life — ever cut me as sharply, deeply, instantaneously. Indeed, it seems plausible to me to divide my life into two parts, before I saw those photographs (I was twelve) and after, though it was several years before I understood fully what they were about.”

Photographs are relics of the past, traces of what has happened. If the living take that past upon themselves, if the past becomes an integral part of the process of people making their own history, then all photographs would reacquire a living context, they would continue to exist in time, instead of being arrested moments. It is just possible that photography is the prophecy of a human memory yet to be socially and politically achieved. Such a memory would encompass any image of the past, however tragic, however guilty, within its own continuity. The distinction between the private and public uses of photography would be transcended. The Family of Man would exist.

Meanwhile we live today in the world as it is. Yet this possible prophecy of photography indicates the direction in which any alternative use of photography needs to develop. The task of an alternative photography is to incorporate photography into social and political memory, instead of using it as a substitute which encourages the atrophy of any such memory.

The task will determine both the kinds of pictures taken and the way they are used. There can of course be no formulae, no prescribed practice. Yet in recognising how photography has come to be used by capitalism, we can define at least some of the principles of an alternative practice.

For the photographer this means thinking of her or himself not so much as a reporter to the rest of the world but, rather, as a recorder for those involved in the events photographed. The distinction is crucial.

What makes these photographs so tragic and extraordinary is that, looking at them, one is convinced that they were not taken to please generals, to boost the morale of a civilian public, to glorify heroic soldiers or to shock the world press: they were images addressed to those suffering what they depict. And given this integrity towards and with their subject matter, such photographs later became a memorial, to the 20 million Russians killed in the war, for those who mourn them. (See Russian War Photographs 1941–45. Text by A. J. P. Taylor, London 1978.) The unifying horror of a total people’s war made such an attitude on the part of the war photographers (and even the censors) a natural one. Photographers, however, can work with a similar attitude in less extreme circumstances.

The alternative use of photographs which already exist leads us back once more to the phenomenon and faculty of memory. The aim must be to construct a context for a photograph, to construct it with words, to construct it with other photographs, to construct it by its place in an ongoing text of photographs and images. How? Normally photographs are used in a very unilinear way — they are used to illustrate an argument, or to demonstrate a thought which goes like this:

Very frequently also they are used tautologically so that the photograph merely repeats what is being said in words. Memory is not unilinear at all. Memory works radially, that is to say with an enormous number of associations all leading to the same event. The diagram is like this:

If we want to put a photograph back into the context of experience, social experience, social memory, we have to respect the laws of memory. We have to situate the printed photograph so that it acquires something of the surprising conclusiveness of that which was and is.

What Brecht wrote about acting in one of his poems is applicable to such a practice. For instant one can read photography, for acting the re-creating of context:

So you should simply make the instant

Stand out, without in the process hiding

What you are making it stand out from. Give your acting

That progression of one-thing-after-another, that attitude of

Working up what you have taken on. In this way

You will show the flow of events and also the course

Of your work, permitting the spectator

To experience this Now on many levels, coming from Previously and

Merging into Afterwards, also having much else Now

Alongside it. He is sitting not only

In your theatre but also

In the world.

There are a few great photographs which practically achieve this by themselves. But any photograph may become such a ‘Now’ if an adequate context is created for it. In general the better the photograph, the fuller the context which can be created.

Such a context replaces the photograph in time — not its own original time for that is impossible — but in narrated time. Narrated time becomes historic time when it is assumed by social memory and social action. The constructed narrated time needs to respect the process of memory which it hopes to stimulate.

There is never a single approach to something remembered. The remembered is not like a terminus at the end of a line. Numerous approaches or stimuli converge upon it and lead to it. Words, comparisons, signs need to create a context for a printed photograph in a comparable way; that is to say, they must mark and leave open diverse approaches. A radial system has to be constructed around the photograph so that it may be seen in terms which are simultaneously personal, political, economic, dramatic, everyday and historic.

1978

0 notes

Text

The Suit and the Photograph

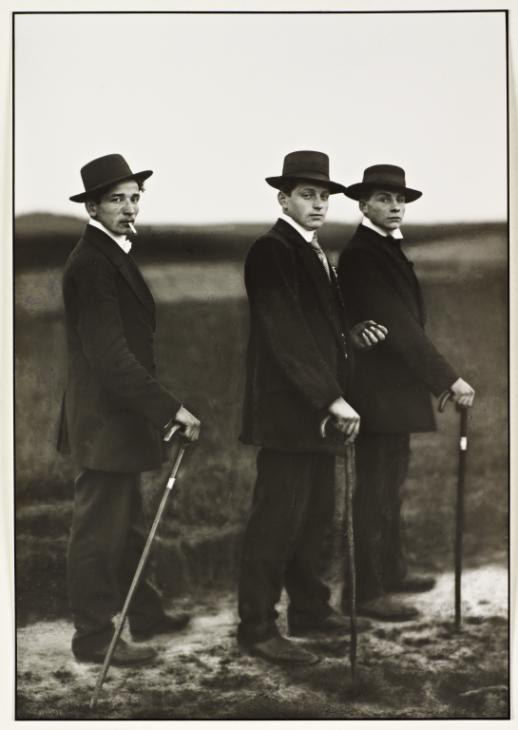

What did August Sander tell his sitters before he took their pictures? And how did he say it so that they all believed him in the same way?

They each look at the camera with the same expression in their eyes. Insofar as there are differences, these are the results of the sitter’s experience and character — the priest has lived a different life from the paper-hanger; but to all of them Sander’s camera represents the same thing.

Did he simply say that their photographs were going to be a recorded part of history? And did he refer to history in such a way that their vanity and shyness dropped away, so that they looked into the lens telling themselves, using a strange historical tense: I looked like this. We cannot know. We simply have to recognise the uniqueness of his work, which he planned with the overall title of “Man of the 20th Century.”

His full aim was to find, around Cologne in the area in which he was born in 1876, archetypes to represent every possible type, social class, sub-class, job, vocation, privilege. He hoped to take, in all, 600 portraits. His project was cut short by Hitler’s Third Reich.

His son Erich, a socialist and anti-nazi was sent to a concentration camp where he died. The father hid his archives in the countryside. What remains today is an extraordinary social and human document. No other photographer, taking portraits of his own countrymen, has ever been so translucently documentary.

Walter Benjamin wrote in 1931 about Sander’s work:

“It was not as a scholar, advised by race theorists or social researchers, that the author [Sander] undertook his enormous task, but, in the publisher’s words, ‘as the result of immediate observation.’ It is indeed unprejudiced observation, bold and at the same time delicate, very much in the spirit of Goethe’s remark: ‘There is a delicate form of the empirical which identifies itself so intimately with its object that it thereby becomes theory.’ Accordingly it is quite proper that an observer like Döblin should light upon precisely the scientific aspects of this opus and point out: ‘Just as there is a comparative anatomy which enables one to understand the nature and history of organs, so here the photographer has produced a comparative photography, thereby gaining a scientific standpoint which places him beyond the photographer of detail.’ It would be lamentable if economic circumstances prevented the further publication of this extraordinary corpus … Sander’s work is more than a picture book, it is an atlas of instruction.”

In the inquiring spirit of Benjamin’s remarks I want to examine Sander’s well-known photograph of three young peasants on the road in the evening, going to a dance. There is as much descriptive information in this image as in pages by a descriptive master like Zola. Yet I only want to consider one thing: their suits.

The date is 1914. The three young men belong, at the very most, to the second generation who ever wore such suits in the European countryside. Twenty or 30 years earlier, such clothes did not exist at a price which peasants could afford. Among the young today, formal dark suits have become rare in the villages of at least western Europe. But for most of this century most peasants — and most workers — wore dark three-piece suits on ceremonial occasions, Sundays and fêtes.

When I go to a funeral in the village where I live, the men of my age and older are still wearing them. Of course there have been modifications of fashion: the width of trousers and lapels, the length of jackets change. Yet the physical character of the suit and its message does not change.

Let us first consider its physical character. Or, more precisely, its physical character when worn by village peasants. And to make generalisation more convincing, let us look at a second photograph of a village band.

Sander took this group portrait in 1913, yet it could well have been the band at the dance for which the three with their walking sticks are setting out along the road. Now make an experiment. Block out the faces of the band with a piece of paper, and consider only their clothed bodies.

By no stretch of the imagination can you believe that these bodies belong to the middle or ruling class. They might belong to workers, rather than peasants; but otherwise there is no doubt. Nor is the clue their hands — as it would be if you could touch them. Then why is their class so apparent?

Is it a question of fashion and the quality of the cloth of their suits? In real life such details would be telling. In a small black and white photograph they are not very evident. Yet the static photograph shows, perhaps more vividly than in life, the fundamental reason why the suits, far from disguising the social class of those who wore them, underlined and emphasised it.

Their suits deform them. Wearing them, they look as though they were physically mis-shapen. A past style in clothes often looks absurd until it is re-incorporated into fashion. Indeed the economic logic of fashion depends on making the old-fashioned look absurd. But here we are not faced primarily with that kind of absurdity; here the clothes look less absurd, less “abnormal” than the men’s bodies which are in them.

The musicians give the impression of being uncoordinated, bandy-legged, barrel-chested, low-arsed, twisted or scalene. The violinist on the right is made to look almost like a dwarf. None of their abnormalities is extreme. They do not provoke pity. They are just sufficient to undermine physical dignity. We look at bodies which appear coarse, clumsy, brute-like. And incorrigibly so.

Now make the experiment the other way round. Cover the bodies of the band and look only at their faces. They are country faces. Nobody could suppose that they are a group of barristers or managing directors. They are five men from a village who like to make music and do so with a certain self-respect. As we look at the faces we can imagine what the bodies would look like. And what we imagine is quite different from what we have just seen. In imagination we see them as their parents might remember them when absent. We accord them the normal dignity they have.

To make the point clearer, let us now consider an image where tailored clothes, instead of deforming, preserve the physical identity and therefore the natural authority of those wearing them. I have deliberately chosen a Sander photograph which looks old-fashioned and could easily lend itself to parody: the photograph of four Protestant missionaries in 1931.

Despite the portentousness, it is not even necessary to make the experiment of blocking out the faces. It is clear that here the suits actually confirm and enhance the physical presence of those wearing them. The clothes convey the same message as the faces and as the history of the bodies they hide. Suits, experience, social formation and function coincide.

Look back now at the three on the road to the dance. Their hands look too big, their bodies too thin, their legs too short. (They use their walking sticks as though they were driving cattle.) We can make the same experiment with the faces and the effect is exactly the same as with the band. They can wear only their hats as if they suited them.

Where does this lead us? Simply to the conclusion that peasants can’t buy good suits and don’t know how to wear them? No, what is at issue here is a graphic, if small, example (perhaps one of the most graphic which exists) of what Gramsci called class hegemony. Let us look at the contradictions involved more closely.

Most peasants, if not suffering from malnutrition, are physically strong and well-developed. Well-developed because of the very varied hard physical work they do. It would be too simple to make a list of physical characteristics — broad hands through working with them from a very early age, broad shoulders relative to the body through the habit of carrying, and so on. In fact many variations and exceptions also exist. One can, however, speak of a characteristic physical rhythm which most peasants, both women and men, acquire.

This rhythm is directly related to the energy demanded by the amount of work which has to be done in a day, and is reflected in typical physical movements and stance. It is an extended sweeping rhythm. Not necessarily slow. The traditional acts of scything or sawing may exemplify it. The way peasants ride horses makes it distinctive, as also the way they walk, as if testing the earth with each stride. In addition peasants possess a special physical dignity: this is determined by a kind of functionalism, a way of being fully at home in effort.

The suit, as we know it today, developed in Europe as a professional ruling class costume in the last third of the 19th century. Almost anonymous as a uniform, it was the first ruling class costume to idealise purely sedentary power. The power of the administrator and conference table. Essentially the suit was made for the gestures of talking and calculating abstractly. (As distinct, compared to previous upper class costumes, from the gestures of riding, hunting, dancing, duelling.)

It was the English gentleman, with all the apparent restraint which that new stereotype implied, who launched the suit. It was a costume which inhibited vigorous action, and which action ruffled, uncreased and spoilt. “Horses sweat, men perspire and women glow.” By the turn of the century, and increasingly after the first world war, the suit was mass-produced for mass urban and rural markets.

The physical contradiction is obvious. Bodies which are fully at home in effort, bodies which are used to extended sweeping movement: clothes idealising the sedentary, the discrete, the effortless. I would be the last to argue for a return to traditional peasant costumes. Any such return is bound to be escapist, for these costumes were a form of capital handed down through generations, and in the world today, in which every corner is dominated by the market, such a principle is anachronistic.

We can note, however, how traditional peasant working or ceremonial clothes respected the specific character of the bodies they were clothing. They were in general loose, and only tight in places where they were gathered to allow for freer movement. They were the antithesis of tailored clothes, clothes cut to follow the idealised shape of a more or less stationary body and then to hang from it!

Yet nobody forced peasants to buy suits, and the three on their way to the dance are clearly proud of them. They wear them with a kind of panache. This is exactly why the suit might become a classic and easily taught example of class hegemony.

Villagers — and, in a different way, city workers — were persuaded to choose suits. By publicity. By pictures. By the new mass media. By salesmen. By example. By the sight of new kinds of travellers. And also by political developments of accommodation and state central organisation. For example: in 1900, on the occasion of the great Universal Exhibition, all the mayors of France were, for the first time ever, invited to a banquet in Paris. Most of them were the peasant mayors of village communes. Nearly 30,000 came! And, naturally, for the occasion the vast majority wore suits.

The working classes — but peasants were simpler and more naïve about it than workers — came to accept as their own certain standards of the class that ruled over them — in this case standards of chic and sartorial worthiness. At the same time their very acceptance of these standards, their very conforming to these norms which had nothing to do with either their own inheritance or their daily experience, condemned them, within the system of those standards, to being always, and recognisably to the classes above them, second-rate, clumsy, uncouth, defensive. That indeed is to succumb to a cultural hegemony.

Perhaps one can nevertheless propose that when the three arrived and had drunk a beer or two, and had eyed the girls (whose clothes had not yet changed so drastically), they hung up their jackets, took off their ties, and danced, maybe wearing their hats, until the morning and the next day’s work.

1979

4 notes

·

View notes