"I could write a blog. I have thoughts." (Amy Adams, Julie and Julia)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Family Bible

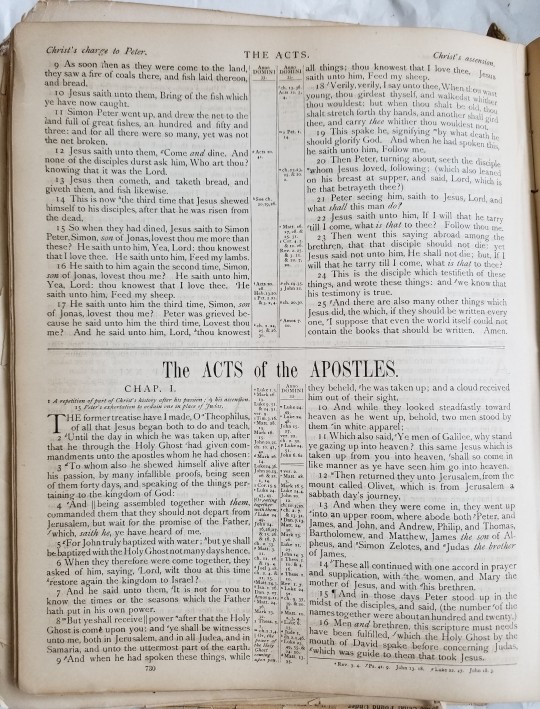

Here I offer a description of a family Bible that was given to me many years ago. It belonged to my father's family; the first event recorded in it is the marriage of my great-grandparents in 1881.

The Bible itself is interesting for two reasons. First, I'm pretty sure it was published in Louisville, Ky., presumably c. 1875. (The title page has been lost, but I recall seeing it years ago and being surprised that it was published in Louisville rather than, say, New York or Nashville.) Second, although it is the King James Version, it includes the Apocrypha or deuterocanonical books such as Ecclesiasticus — unusual for a Protestant Bible. The cover is 12 5/8" high and 9 5/8" wide (32.2 cm × 24.3 cm); the pages, 11½" H × 9 5/16" W. The book is about 4 1/8" thick. The accompanying pictures show the book and a typical page.

Bibles of this era are usually of interest for their genealogical information, so let's get to that. The first page after the Apocrypha records the marriage of George H. Rommel and Sophie Haager on January 12, 1881.

On the next page we have the marriages of their children:

Elsie May Rommel to Robt. Elmer Hickey — Nov. 25, 1914 Albert J. Rommel to Omea C. Irvine, June 14, 1916 John R. Rommel to Helen R. Rietze, Oct. 25, 1916 Will. D. Rommel to Louise Schaarschmidt, Nov. 26, 1917 [my grandparents] Ruth Caroline Rommel to Walter W. Wilhoit, Feb. 28, 1925 Clarence J. Rommel to Betty Ray Hart, Sept. 20, 1930 [I was told that Clarence bore a strong resemblance to the Desert Fox himself, Erwin Rommel] George Harry Rommel to Mary Hanafee, Aug. 17, 1936

At this point there is a heading in my father's hand saying “marriages of grandchildren”, which is probably correct except for Elsie's second marriage.

John L. Rommel Jr. to Sherrill Wagner, Sept. 6, 1941 Alla Irvine Rommel to Joseph Gordon, December 1941 Alla R. Gordon to James McConathy, Sept. 1, 1945 Elsie R. Hickey to Louis B. Elliott, May 22, 1948 [Elsie's second marriage. Elsie and Louie were still alive when I was a boy, and I fondly remember going to visit them. Louie played the harmonica for us, quite well. He was also noted for having good teeth; he allegedly brushed his teeth five times a day. Elsie was a tough bird and lived to 95.] Geo. Irvine Rommel to Marilyn Dayton, June 1948 Robert Malcolm Rommel to Doris Ann Frick, Aug. 28, 1948 Ralph Haager Rommel to Mattie Hoskins, April 28, 1951 William Houghton Rommel to Ann Hayes, Mar. 19, 1955 [my parents; my mother's name reads “Anne Phylis”, but she detests the name Phyllis and has never used it]

The next page shows the births of George H. and Sophie's children:

William D. Rommel Born Nov. 28, 1881 John L. Rommel Born Nov. 28, 1881 Robert H. Rommel Born May 3, 1883 George Harry Rommel Born Nov. 18, 1884 Julius Albert Rommel Born Sep. 12, 1886 Louis Edward Rommel Sep. 6, 1888 Elsie May Rommel June 30, 1891 Clarence Jos. Rommel Feb. 6, 1893 Ruth Caroline Rommel Feb. 26, 1895

The next page shows deaths:

Louis Edward Rommel, Feb. 1, 1901, 3 pm Robert Haager Rommel, April 16, 1929, 11 am (Father) George H. Rommel, Oct. 22, 1933, 2:30 pm (Mother) Sophia Haager Rommel, Dec. 14, 1935, 10:30 am Robert Elmer Hickey, July 12, 1937, 11 am Walter W. Wilhoit, April 7, 1940, 7:45 am Lt. Joseph Gordon (airplane accident in Australia), April 1942 Clarence Joseph Rommel, April 19, 1944, 2:30 am Omea Irvine Rommel (wife of A.J.R.), May 9, 1945, 5 am Betty Hart Rommel (wife of C.J.R.), June 26, 1947, 6 pm Infant son of Alla and James McConathy, Dec. 13, 1947, at birth Mary Hanafee Rommel (wife of George Harry), July 25, 1949, 9:30 pm Julius Albert Rommel, March 23, 1952, 6:45 pm William D. [Daniel] Rommel, August 29, 1955, 1:30 am Ruth Caroline Rommel Wilhoyte, July 5, 1961, 7 pm [I suppose Wilhoyte is a variant spelling of Wilhoit.] Phyllis Jane Rommel – daughter of William D. and Louise S. Rommel, September 24, 1963, 4:30 pm John L. Rommel Louise S. Rommel, wife of Wm. D. Rommel [my grandmother, whom I remember dimly; this must have been around 1968] George Harry Rommel, Sept. 16, 1972 Louis B. Elliott [Nov. 5, 1972] [Elsie is not shown, but she died on Jan. 26, 1987]

The next page, headed "Memoranda", contains the births of grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Billy Houghton, son of W. D. Rommel, born February 5th 1919 [my father] John Larabee Jr., son of J. L. Rommel, born August 30th 1919 Alla Irvine, daughter of A. J. Rommel, born December 25th 1919 Ralph Haagar, son of W. D. Rommel, born April 15th 1921 George Irvine, son of A. J. Rommel, born May 24th 1921 Phylis Jane, daughter of W. D. Rommel, April 21, 1923 Robert Malcolm, son of W. D. Rommel, April 1, 1927 [great-grandchildren:] Susan Stuart, daughter of John Larabee Jr., August 2, 1944 Infant son, at birth, of Alla and James McConathy, Dec. 13, 1947 Mary Leigh, daughter of John and Sherril Rommel, Jan. 16, 1948 Lylar Dayton, daughter of Geo. Irvine & Marilyn, April 25, 1949 Lucinda Omea, daughter of Alla Irvine Rommel & James McConathy, Sept. 8, 1949 Karen Louise, daughter of Ralph Haagar & Mattie Rommel, Jan. 27, 1952 Park Heaton, son of Geo. Irvine & Marilyn, March 14, 1952, 11 pm Jane Mitchell McConathy, daughter of James & Alla McConathy, May 9, 1954, Henderson, Ky. Deirdre Alla McConathy, Oct. 8, 1954 Cathrine Ann Rommel daughter of Ralph & Mattie Rommel, May 17, 1953

The next and final page continues the list of great-grandchildren.

Ralph Gregory Rommel, son of Ralph H. & Mattie H., August 25, 1957 Robert Wilhoit Rommel, son of Robert M. & Doris F. Rommel, Sept. 12, 1957 William Geoffrey Rommel, son of William H. & Ann H. Rommel, May 1, 1959 [hey, that's me] George Evan Hayes Rommel, son of William H. & Ann H. Rommel, March 31, 1962 Melissa Kaye Rommel, daughter of Ralph H. & Mattie H., April 1st, 1962 Harry Louis Rommel, son of William H. & Ann H. Rommel, Dec. 11, 1971 Stephen Daniel Rommel, son of William H. & Ann H. Rommel, January 22, 1974

1 note

·

View note

Text

Confused?

In The Wizard of Oz, the Wizard famously says to the Cowardly Lion, “You are under the unfortunate delusion that simply because you run away from danger, you have no courage. You’re confusing courage with wisdom.” This is a mistake. He should have said “You’re confusing cowardice with wisdom.”

If you don’t see the mistake, there are two considerations that make it clear, one from logic and one from the dramatic context.

First, the logic. (1) The expression “to confuse A with B” means to think that A and B are the same thing when they really aren’t. For example, confusing viral pneumonia with bacterial pneumonia would be to think that the two are the same, or maybe that a patient with viral pneumonia actually has bacterial. (2) Why would anyone confuse two things? Surely because they are strikingly similar in some way. For example, viral pneumonia and bacterial pneumonia can be confused because they cause similar symptoms. (3) Now, the Wizard says the Lion has confused two things that are similar because both of them cause one to run away from danger. These two things are wisdom and ... what? Courage? No, cowardice, of course. So the Wizard should have said “cowardice” rather than “courage”.

The logic is supported by the dramatic context. The line is supposed to be funny; the Wizard is suggesting that the Lion is more courageous than he thinks but also ribbing him. Now, in order to raise a laugh, the line should suggest that the Lion is confusing a vice with a virtue. Obviously, confusing one virtue with another would not be funny, or not as funny anyhow. For example, it might be funny to say “You’re confusing love with lust”. So the comparison should be between a vice and a virtue: cowardice and wisdom.

Q.E.D.

[6/22/2020]

0 notes

Text

More than One

Let's talk about plurals. To be sure, this is an odd subject for a blog post, but some mistakes are so common and so glaring that they need to be corrected.

The first few rules are simple enough. Most plurals are formed by adding -s. One dog, two dogs; one number, two numbers. If the word ends with -y, the plural ends with -ies: fly, flies; city, cities. (However, if the word is a proper name, the 'y' does not change: Kennedy, Kennedys.) If the word ends with an 's' or ‘z' sound, the plural ends with -es: class, classes; boss, bosses; whiz, whizzes; Jones, the Joneses.

There are some exceptions that are so common they don't usually cause trouble for anyone: child, children; goose, geese; sheep, sheep.

So far, so good. Now things start to get tricky. I was taught in school that the plurals of acronyms and numbers should be formed with an apostrophe and s: YMCA, YMCA's; 1980, the 1980's. Nowadays, however, the fashion has changed; many editors dislike those apostrophes and omit them. That's fine, but I'm not sure the rule should be enforced in every case. For instance, "The students all received As" might confuse some readers; "A's" seems clearer to me.

Now we come to our first glaring error. Perhaps because people dimly remember the apostrophe-s rule, they often insert apostrophes where they don't belong: pro's and cons (should be pros); do's and don'ts (should be dos). Don't do that!

As you know, apostrophe and 's' are also used to form possessives: Shakespeare's Hamlet, Ruth's home run, the Beatles' records. Be sure to think about whether you're forming a plural or a possessive: the bosses (plural) disagreed; the boss's (possessive) son; the Joneses (plural) moved in; Mr. Jones's (possessive) car; the Joneses' (plural and possessive) dog. Tom and Gisele are the Bradys; their house is the Bradys' house.

Watch out, too, for a few terms in which a noun is followed by an adjective. The noun is pluralized: attorneys general, courts martial, mothers-in-law.

By the way, when pronouncing the plural of words that end in -st, do not add an extra syllable. People aren't usually tripped up by "beasts" or "chests", but many people add a third syllable to breakfast: "breakfastes". What's up with that? It's two syllables: "brek-fusts".

Sometimes there is confusion about the words incident and incidence. An incident is an occurrence, often an occurrence in which something goes wrong: There was an incident at the dog park; the hockey game proceeded without incident. The plural is incidents—simple enough, right?—but many people insert an extra syllable, saying “incidences”. Now, incidence is a separate noun; it usually means “frequency” (”there was a low incidence of tornados that season”). There might be a rare need to say incidences, but most of the time it is a mistake. (Theoretically, this confusion could arise with other pairs of words, such as correspondent/correspondence or even accident/accidence, but those don’t seem to pose the same problem.)

Words that end with f or fe sometimes form their plurals with -s (chiefs, beliefs) and sometimes by changing the f to a v (leaf/leaves, knife/knives, oaf/oafs, loaf/loaves). The traditional plural of dwarf is dwarfs. Some stars, NASA tells us, are white dwarfs. J. R. R. Tolkien, however, consciously violated this rule by referring to his creatures as dwarves, and that usage is now followed by many. Whether these people are to be commended for their literary taste or reviled for their ignorance of English we may leave undecided.

A troublesome category is words from Latin or Greek that retain their classical plurals: alumnus, alumni; alumna, alumnae; fungus, fungi; stigma, stigmata; phenomenon, phenomena; crisis, crises. On the other hand, some words have become fully naturalized in English and use -s or -es: campus, campuses (not campi). When in doubt, consult a dictionary.

Here are some that call for particular attention. The most misused word in the English language right now may be criteria, which is plural, not singular; the singular is criterion. One criterion, two criteria. Really! Bacteria is plural; the singular is bacterium. It's amazing how many people treat bacteria as singular—the horror! Media is plural, not singular. The press is a medium; radio is a medium; television is a medium; together they are media. The Latin word nexus is fourth declension, so the Latin plural would be nexus with a long u (A. N. Whitehead spelled it nexūs). In English, though, nexuses is the way to go.

The words kind, sort, and type are often used awkwardly, as in “these kind of gloves”. This perplexing plural problem has been often discussed (e.g., at https://www.ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=kind), so I won’t belabor it here.

Chinese and Japanese do not have separate forms for plurals, so some writers do not add -s to them in English. For instance, William Golden uses the same forms throughout Memoirs of a Geisha: one geisha, two geisha; one kimono, two kimono. I wouldn't insist on this rule, though.

Finally we come to perhaps the most perplexing word: octopus. There are several Web pages that go into great detail on the competing plurals for this word—octopi, octopuses, and octopodes—so I won't repeat what they say. I will just note two things. First, I prefer octopuses, which is a sensible plural and less startling to the reader than the more correct octopodes. Second, according to the Oxford Greek lexicon (Liddell–Scott), the ancient Greeks spelled the word with an alpha as the fourth letter (oktapous). Where did the spelling octopus come from? I have no idea!

0 notes

Text

It’s a Dead Thing

(WARNING: Some spoilers ahead.)

On July 15, 2020, I finished watching the first two seasons (so far the only seasons) of Dead to Me on Netflix. It is an intriguing series for several reasons. First, it seems to be a girl power project: not only the creator, but all the writers and directors appear to be women (including the mysteriously named Silver Tree). The budget is quite generous for a television project; the production values are strong, the settings lavish, the actors excellent. Linda Cardellini (Judy) is adorable, as always. Best of all, Christina Applegate in the lead role, Jen, is outstanding, by turns emotional, intense, and witty. She was deservedly nominated for several awards, including a Golden Globe and a Primetime Emmy.

The series is a black comedy or "dramedy". Jen's husband has died in a mysterious car accident, leaving her with two sons and a censorious mother-in-law. One day she goes to a grief group led by Brian, a sort of generic Christian pastor, and meets Judy, who has recently broken up with her boyfriend (James Marsden) and has nowhere to live. They quickly become friends, and the whole situation immediately goes haywire. The plotting is ingenious, but certain twists are so outlandish as to bring the story near to fantasy. For instance, in one scene it is revealed that a character has hidden a huge amount of cash in an object that was "sitting in a police locker". This is utter fantasy for two reasons. First, the object in question is relatively light, so the police would almost certainly have detected the extra weight of the bills. More importantly, the federal government and banks, in the name of fighting crime, have made it nearly impossible to get your hands on large amounts of cash (especially since, in this story, the character supposedly withdrew it all at once). But if you can live with flaws like this, the story is engaging.

To this writer, however, the most intriguing aspect of the show is the writers' attitude toward religion. Nowadays we have come to expect that shows from Hollywood will display indifference or outright hostility to religion. This one, however, is ambiguous. To be sure, some features are negative. Brian, the pastor, seems a bit out of touch. Jen obviously regards religion as nonsense. At a funeral, Jen's mother-in-law expresses some hope for the afterlife to one of the boys; Jen then leans over and says, "She is fucking lying to you." At a Jewish grief group, the rabbi tells Judy there is no heaven or hell—perhaps not an unusual line for a rabbi to take, but Judy is clearly disappointed.

On the other hand, one sympathetic character (Christopher) is a choir leader and on one occasion offers a prayer. Jen's negative attitude toward religion, indeed toward nearly everything, becomes tiresome even to her. Brian comments that God will bring the truth to light. Within an episode or two that indeed happens: partly because of that remark, Jen finally decides to come clean, and her life starts to get better—although in the final scene of season 2 things may start to get worse again. Most importantly, in the last episode Judy tells Jen "I forgive you", an unexpected development that brings a breath of relief and redemption. As far as I can tell, this show is not a stealth endorsement of Christianity (as Juno might have been), but it doesn't seem reflexively hostile either.

Four and a half stars. Eagerly awaiting season 3.

0 notes

Text

There’s No Starman

On January 5, 2020, The Guardian published a short interview with Helen Sharman, Britain's first astronaut. The following paragraph was singled out by Bing as newsworthy:

Aliens exist, there’s no two ways about it. There are so many billions of stars out there in the universe that there must be all sorts of different forms of life. Will they be like you and me, made up of carbon and nitrogen? Maybe not. It’s possible they’re here right now and we simply can’t see them.

Does spending your life among the stars cause you to lose touch with the earth? Maybe so. The first part of this statement is an old talking point, mindlessly repeated since at least the time of Carl Sagan: gee whiz, there are so many stars and planets in the universe that there must be intelligent life out there somewhere. Let's be clear: there is absolutely no evidence for intelligent life on any planet other than ours. It does seem likely that there could be water on other planets, and possibly prokaryotic life, but there is no hard evidence for anything beyond that, certainly not for complex organisms that use oxygen for their metabolism. A quick Web search will reveal several articles that come to that conclusion from various angles, this one for instance.

Even more troubling is the second part: "Will they be like you and me, made up of carbon and nitrogen? Maybe not. It’s possible they’re here right now and we simply can’t see them." What the hell is she talking about? Silicon is chemically similar to carbon, so some biochemists have speculated that some life forms could be based on silicon. That seems unlikely, though; silicon is more than twice as massive as carbon, and that property makes for some serious difficulties. Be that as it may, if these aliens are physical beings and complex enough to be intelligent, they would have to be made of physical elements and therefore visible. Her suggestion that they might be invisible is ludicrous. The only reason I can think of for this baffling remark – and this is speculation – is that, like many people, Ms. Sharman does not believe in angels but somehow feels an urge to believe in invisible, intelligent beings. She therefore places her hope for finding such beings in the natural world.

While we're on the subject, the Navy has recently admitted that certain videos showing "UFOs" are real and remain unexplained by aviation experts. This has led to renewed speculation that these phenomena could be connected with aliens from other planets. Nonsense. If aliens even exist, it would be practically impossible for them to visit us. Consider the time, resources, and brain power that it took to send three men to the moon – an endeavor that was so costly and exhausting that we no longer do it. The moon is less than 2 light-seconds away. The nearest star, Alpha Centauri, is actually a three-star system, so its planets probably can't support life. The next closest, Barnard's, is about 6 light-years away. Hmm ... 2 light-seconds, 6 light-years. That's a big difference. There probably isn't enough wealth in the world, or on any other world, to send a spaceship that far. And what about the time? Most of us don't like to commute more than 30 minutes to work. If you could build a ship that traveled at 10% of the speed of light (quite a tall order), it would take 60 years to get from one star to another. Who's going to sign up for a trip like that?

Face it: there are no other planets with intelligent beings. Even if there were, they wouldn't be coming here. Ever. Looking for them is a colossal waste of time and energy. If you need friends, you'll have to make them on this earth.

0 notes

Text

There Is No Evidence

In this clip from Red Eye, Penn Jillette talks about why he doesn't believe in God. He mentions two reasons: (1) wondering how a good God could allow his mother to suffer so much before she died, and (2) the alleged lack of evidence for God's existence. He remarks that the first reason is "emotional", but the second is "intellectual" (and so, presumably, more serious).

There is a lot to like about Penn: his forthrightness, his war against bullshit, his advocacy of liberty. But I have to disagree with him on this one.

Oddly enough, Penn seems to have his assessment of the two arguments backwards. The first argument, that a benevolent and omnipotent God could not allow suffering, or at least some kinds of suffering, is a serious argument that has vexed many, both believers and unbelievers, for centuries. C. S. Lewis wrote a whole book about it. I shall pass it by for now, though. The second argument, on the other hand, is, shall we say, not as solid as it may appear.

Let us first note that the expression "There is no evidence for X" has unfortunately become a cheap way of sounding intellectual. After all, important people like scientists and lawyers say "There's no evidence." It is supposed to convey that in the course of long experience you have investigated the entire field, diligently searching for evidence, and have found none. In reality, most people who say this have never examined any of the evidence; they're just repeating what someone else has told them.

Still, let's give Penn the benefit of the doubt and assume that he has made some attempt to examine the "evidence". What sort of evidence would he be looking for? Sometimes people seem to imply that they want scientific or empirical evidence, the sort of evidence you would use to determine that pheromones exist, or muons, or black holes. Now, it's true that the extension of scientific methods and instrumentation in the last two centuries has made it possible to find many elusive natural phenomena that our ancestors never dreamed of. But God is supernatural. If there is evidence for His existence, it will certainly be of a different order from the evidence for even the most occult natural beings.

We shall again give Penn the benefit of the doubt and assume that he is looking for some sort of evidence for God's existence that isn't like the evidence for neutrinos or the expansion of the universe. Very well, then: what sort of evidence will he accept? And here's the rub.

Ordinarily, when we look for evidence of X, we are looking for something that can establish the existence or occurrence of X and nothing else. A prosecutor wants evidence that the crime was committed by the defendant and not by anyone else. But what evidence could we offer that can establish the existence of God and at the same time rule out any other possibility? If you argue that living things exhibit evidence of design, the atheist can retort that it all just happened in the course of "evolution" (a very expansive term). If you argue that the universe as a whole seems to have a design, perhaps invoking the "anthropic principle", the atheist can retort that this is just the one of many possible universes that we happen to be in. If you ask why there is something rather than nothing, the atheist can retort that "nothing" is impossible and the Void must be fruitful. If you say that the moral sense is a sign that there is something beyond mere physical reality, the atheist can retort that the moral sense is nothing more than what we have been taught to think. In short, if the atheist is determined to counter every argument, there is no limit to the ingenuity he can bring to bear to fend off the unwelcome conclusion.

Moreover, it may not even be possible for God to act in the natural world in an unambiguous way. Whatever happens in the world around us is part of nature and will be subject to the usual means of scientific or historical investigation. So even if God were to intervene in a natural process, there would still be something "natural" about it, something that makes it look like the rest of nature. To draw a (perhaps clichéd) analogy, if a cube were to intervene in two-dimensional space, he would look like a square, and many inhabitants of Flatland would say that there was nothing special about him. For this reason, it is always open to the skeptic to say that something natural accounts for what happened. If a sick woman is suddenly healed, she has experienced remission because of the body's ability to heal itself; if a saint sees a vision, he has had an unusual psychic experience; and so on.

Thus we seem compelled to conclude that the atheist must be willing to allow for the possibility of God's existence in order to accept any evidence at all. Is the atheist guilty of bad faith — asking for evidence but having no intention of accepting any? Or have we hit a true logical impossibility — demanding that the atheist believe before he can be persuaded to believe? It is not easy to say. The only way out of the impasse, it seems, would be for the atheist to say what kind of evidence he will accept. (Does anyone ever ask this?) And being ready to accept some kind of evidence — any kind at all — might itself be an openness to God. Maybe the whole question is more a matter of the heart than the head. Le cœur a ses raisons.

0 notes

Text

Scribble, Scribble

On December 23, 2017, I finished reading Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Yes, the whole thing. It's about a million words (not counting the footnotes) and took me ten months. I feel that after this lengthy effort I should offer some thoughts on the work. I am by no means an expert in history or English, but perhaps my musings may be of interest to some folks.

Gibbon, of course, was fluent in Greek and Latin and bases his narrative mostly on primary sources in those languages, especially in the first 38 chapters. His choice of words is exact and rhythmic. The style is beautiful and stately, though perhaps a little too leisurely for us impatient 21st-century readers. As one who doesn't read much history, I found Gibbon's main weakness to be a lack of plain, picturesque narrative. He often seems to talk around the events or to assume that the reader already knows what happened. Every so often he vividly describes a naval battle or an encounter between two potentates; the narrative comes alive for a page or two; and then we are lulled half asleep again.

Gibbon frequently comments, almost casually, that someone acted fanatical or superstitious rather than “philosophical”. He seems quite sure that he knows the proper way in which to be a philosopher. Despite this, his philosophical ideas are few and unremarkable: he is skeptical of miracles, relics, and the veneration of saints; he despises metaphysics and the excesses of the Platonists; he believes that Newton and Science have enlightened the world; he admires ancient Roman virtue and deplores its decline. Now and then he will say something arresting, such as this: "During [John Comnenus's] government of twenty-five years, the penalty of death was abolished in the Roman empire, a law of mercy most delightful to the humane theorist, but of which the practice, in a large and vicious community, is seldom consistent with the public safety" (ch. 48). For the most part, though, Gibbon is far more comfortable reciting events, dates, and geography. Maybe this is to be expected of a historian; Aristotle pointed out that "poetry is something more philosophic and of graver import than history" (Poet. 1451b6). Or, as Thomas Rymer memorably puts it, "History ... only records things higlety, piglety, right or wrong as they happen."

Gibbon's most alarming philosophical position, stated more than once, is this: "In the connection of the church and state, I have considered the former as subservient only, and relative, to the latter; a salutary maxim, if in fact, as well as in narrative, it had ever been held sacred" (ch. 49). Valentinian "never forgot that he was the sovereign of the clergy" (ch. 25). "The pulpit," he writes, "that safe and sacred organ of sedition ..." (ch. 37). In other words, the state is supreme in all things, and any opposition to it by the church is a violation of authority – sedition, that is. This Hobbesian totalitarianism is made all the more chilling by the urbane tone in which it is delivered. Now, Gibbon may have thought such a maxim innocuous; he congratulates himself and his contemporaries on their reasonableness and support for freedom. In these happy days, a government would never kill millions of its own citizens or throw dissidents in prison – right? Surely there would never be a need for an independent authority that might at least cry in the wilderness against the state's violations of human rights. We who have witnessed the horrors of Communism and Nazism, not to mention the role of Pope St. John Paul II in staring down the Soviet Union, will rather be inclined to encourage the independence of church and state.

On three occasions Gibbon uses the epithet "extraordinary man": for Julian the Apostate ("Such was the end of that extraordinary man," ch. 24), Muhammad (ch. 50), and Cola di Rienzi (ch. 70). Gibbon clearly admires Julian, is unsure about Muhammad, and finds Rienzi a buffoon. His portrait of Julian shows a marked contrast to that of Constantine. Most people would describe Constantine too as extraordinary, but Gibbon seems to find him of little interest, while he allows Julian to occupy space in four chapters and describes his life and thoughts in detail. To be sure, Constantine was a man of action whose life was told by others (particularly by Eusebius, whom Gibbon thoroughly mistrusts), whereas Julian was a writer and a soi-disant philosopher as well as an emperor; thus Julian has always appealed more to literary men and intellectualoids. Still, it is telling that two of these extraordinary men were enemies of Christian civilization, or even of Christ himself.

Perhaps the most interesting side of Gibbon for us today is his treatment of Muhammad and the early history of Islam. In chapter 50 he writes, "At the conclusion of the life of Mahomet, it may perhaps be expected, that I should balance his faults and virtues, that I should decide whether the title of enthusiast or impostor more properly belongs to that extraordinary man." So it may. At first Gibbon sidesteps the question, pleading the remoteness of the events, but he then suggests that both titles are applicable. Still, in keeping with his policy of toleration, he offers little criticism of the Prophet or his religion. As the history proceeds, he sometimes calls the Muslim conquerors "fanatics", but he just as often mentions their tolerance for Christians and Jews who come under their rule (in Spain, for example).

His remarks on the consistency of Islam over the centuries also bear quotation: "the same pure and perfect impression which he engraved at Mecca and Medina, is preserved, after the revolutions of twelve centuries, by the Indian, the African, and the Turkish proselytes of the Koran.... The intellectual image of the Deity has never been degraded by any visible idol; the honors of the prophet have never transgressed the measure of human virtue; and his living precepts have restrained the gratitude of his disciples within the bounds of reason and religion.... he breathed among the faithful a spirit of charity and friendship; recommended the practice of the social virtues; and checked, by his laws and precepts, the thirst of revenge, and the oppression of widows and orphans" (ch. 50). "More pure than the system of Zoroaster, more liberal than the law of Moses, the religion of Mahomet might seem less inconsistent with reason than the creed of mystery and superstition, which, in the seventh century, disgraced the simplicity of the gospel" (ch. 51). In short, he regards Islam as a pure and simple religion, almost Enlightened, that discouraged useless metaphysical speculation and inculcated love of humanity (or at least of one's coreligionists). Perhaps judgments like this, echoing faintly down the ages, explain some of the tendencies in this country to regard Islam as a peaceful, harmless faith.

I used the three-volume Penguin edition edited by David Womersley, first published in 1994 – a very nice edition. Gibbon's marginal notes are shown at the side of the page. These are important, because Gibbon usually does not give dates in the main text; only from the margin do we learn that Diocletian's triumph took place on Nov. 20, A.D. 303. The notes are conveniently given at the foot of the page.

There are three notable misprints in Volume II. On p. 264, "defendants" should read "descendants". On p. 876, in a marginal note, the dates given for Gregory's pontificate contradict the text; "February 8" should read "September 3". On p. 973, marginal note, "11d" should read "IId" (two capital I's, i.e. "second").

Dr. Johnson once said, "Paradise Lost is one of the books which the reader admires and lays down, and forgets to take up again. None ever wished it longer than it is." I found myself reacting much the same way to The Decline and Fall. (Always scribble, scribble, scribble, eh, Mr. Gibbon?) Many have commented that Shakespeare's plays can be read over and over, that one finds new meanings in them as the years go by. I doubt that I shall ever think that of Gibbon's work, magnificent achievement though it may be.

0 notes

Text

They Could Be Heroes

While crawling the Web, I happened upon an article by Maureen Mullarkey (whose work I am not familiar with). The article is not bad, fairly thought-provoking, but contains this astonishing passage:

[Pope Francis] certified the two Fatima tykes, Jacinta and Francisco Marto, as saints. And he did so on the high ground of heroic virtue, a quality these children never lived long enough to exhibit.

The youngest non-martyrs ever to be canonized in all of Church history, they died quietly in their beds of Spanish flu. Francisco, just short of his eleventh birthday, and Jacinta, ten, were simply two among tens of millions killed by the 1918 pandemic. (Better the Lady in white had sung these little ones a lullaby instead of showing ghastly images of hell.)

Wow. According to the memoirs of Sister Lucia, the Blessed Virgin told Jacinta and Francisco that they would go to heaven; they prayed constantly and underwent considerable suffering without complaint. Jacinta may have bilocated on at least one occasion. When her body was exhumed in 1935 it was seen to be incorrupt. But to Ms. Mullarkey they are just statistics—just two victims of influenza.

Then again, maybe Ms. Mullarkey doesn't believe in the Fatima apparitions at all: she calls the children "tykes" and snidely questions the judgment of the "Lady in white". Of course Catholics are not required to believe in any private revelation, but since Ms. Mullarkey apparently considers herself a faithful, even traditional, Catholic, such a position would be surprising.

In addition to her sneers at Jacinta and Francisco, she suggests that children who die before a certain (unspecified) age cannot exhibit heroic virtue. Now, to be sure, this may be true in most cases, but is she prepared to assert this of all children without exception? To take just two examples, St. Maria Goretti resisted her attacker and died at age eleven, and St. Dominic Savio died at fourteen. Would we dare to maintain that St. Thérèse of Lisieux exhibited no heroic virtue when she was a child? Until what age?

Those are admittedly exceptional cases. But I dare say that many readers can supply examples from their own experience. A young lady of my acquaintance who has a shunt in her brain underwent more than 50 brain surgeries before she turned 18. Her patience, obedience, and even cheerfulness were an inspiration to all around her. But apparently she couldn't have been exhibiting heroic virtue because she was just too young.

0 notes

Text

Ascension Musings

Yesterday, May 28, 2017, was the feast of the Ascension of Jesus. (Well, actually, the feast of the Ascension is traditionally forty days after Easter and would have fallen on the preceding Thursday, but nowadays it is usually moved to the following Sunday.) Three annoyances took place.

In the morning we went to Mass. The first reading was the opening of the Acts of the Apostles: "In the first book, Theophilus, I dealt with all that Jesus did...." St. Luke is speaking to Theophilus, and the "first book" he refers to is, of course, the Gospel of St. Luke. Apparently, though, the reader did not realize this; he read the word "Theophilus" as if it were the name of the first book!—as if he were saying, "In my first novel, War and Peace, I wrote about Napoleon." One wonders how well people know their New Testament.

Oh, well ... that was a small point. But then the deacon began his homily by bringing out a piece of plywood and saying, "This is what they thought the world looked like back then." Then he pulled out a globe and said, "Now we know the world looks like this ... so when Jesus ascended"—he held the globe so that Jerusalem was on top—"did he go up? But if the world is like this"—he held the globe so that Jerusalem was on the side—"he sort of went sideways." Then he said that it was incorrect to "take the words literally".

Wow. Where to begin? (1) The visual aids were a little cheesy, but let that pass. (2) The Greeks knew the earth was round. People of the first century did not think the earth was flat. Was the deacon just using this misconception to make a point, or did he really believe it? Time was when you could count on the Catholic clergy to be pretty well educated, especially on basic matters of ancient history. That may not be true anymore. (3) Once he introduced the globe and the Newtonian picture of a vast directionless space, it no longer made sense to say that Jesus went "sideways" or "down". (4) In any case, asking how the ascension of Jesus is related to the solar system introduces a foreign concept into the narrative. Luke is reporting what the apostles saw, and what they saw was that Jesus went up, i.e., away from the earth. The question of where or in what direction he went after they lost sight of him simply doesn't arise. Sister Lúcia reported that Our Lady of Fátima returned to heaven in a similar way in 1917. (5) But the worst offense is the clichéd remark that we shouldn't "take the words literally". Excuse me. We most certainly must take them literally. The apostles saw Jesus going up, literally, and that is an article of the Creed, literally.

Much could be said about the timid disavowal of literal truths, but I shall move on to the third annoyance of the day. We went to a family function, and the fellow who said grace began by saying, "In the Catholic tradition, in the name of the Father," etc. Now why did he insert "in the Catholic tradition"? Most likely because there were non-Catholics present and he wanted to let them know that he was doing a Catholic Thing. Most people know that Catholics use the sign of the cross—that's not exactly a secret—so the gesture was unnecessary, but more importantly it came off as an apology. "Well, we Catholics do this sign of the cross thing, but that's just our tradition, y'know, you have different traditions, you don't have to do it, don't be offended, it'll just take 4 seconds and we'll move on, have some baked beans." Please! Even if you don't believe that the Catholic church is the Church founded by Christ and has preserved the fullness of Christian doctrine, there is no reason for Catholics to apologize for their practices. If you're going to say the sign of the cross, just say it!

So this is where the Catholic Church in the good ol' USA is in 2017: ignorant of the Bible, confused about doctrine, timid in practice. Is it any wonder that people don't take the Church seriously?

0 notes