Text

#reading#books & libraries#prose#punk#prison#books#pruno#burden of concrete williamshayes punkhostagepress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m currently working on a piece—kind of a cross between Bukowski’s Factotum and Barfly, but with my voice. It’s a fun story.

0 notes

Text

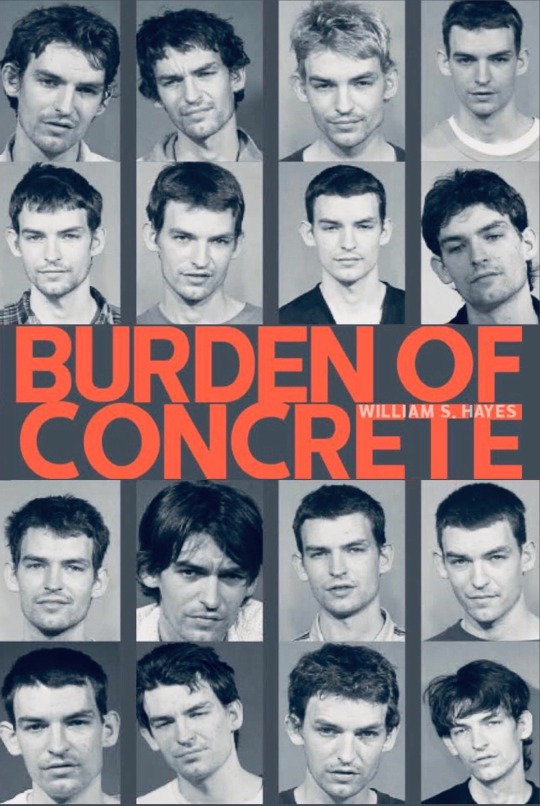

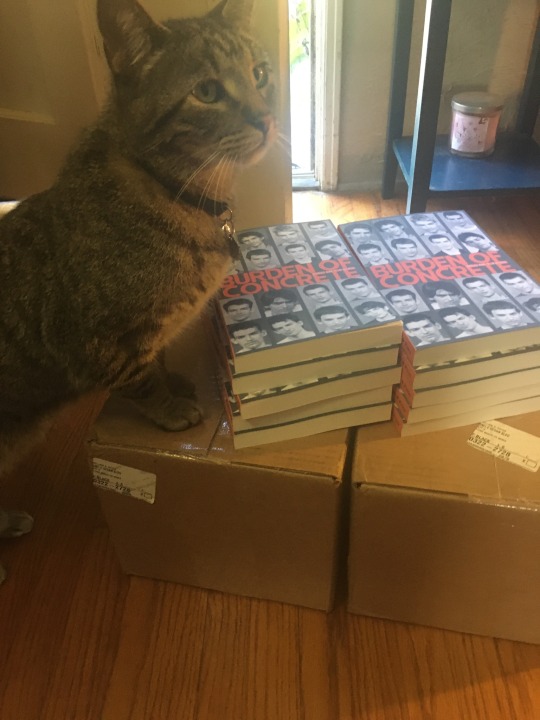

An excerpt from Burden of Concrete. Order a copy through Punk Hostage Press or Amazon!

It took over a month to catch the chain, and the only thing different, as far as the process was concerned, was the demeanor of those I caught the chain with. They represented various streets and neighborhoods of Los Angeles and they all shared one of two stories—a history of drug abuse and/or being from a gang. Two of the prisoners were sentenced to life and rode their charges like “G’s”, exuding a calm and cool that surely belied their true feelings of despair. I couldn’t possibly gauge the mental state of a man being sent away for life but knew from seeing others doing time it would take a few years for the sentence to fully sink in. The letters would start coming with less frequency and the visits would all but disappear, until the only ones coming to see them were their mothers, whose eyes ceased crying long ago, and their lawyers. Once the appeals process was exhausted, and the burden of concrete became too much to endure, there was nothing left but to die.

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

My memoir Burden of Concrete is out now. It’s about growing up in Seattle during the height of the city’s music and heroin explosion, and my subsequent downfall. I take the reader through numerous instructions and California prisons, with direct prose and, at times, humor. It’s available on Amazon. Check it out.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My memoir Burden of Concrete is out now. It’s about growing up in Seattle during the height of the city’s music and heroin explosion, and my subsequent downfall. I take the reader through numerous instructions and California prisons, with direct prose and, at times, humor. It’s available on Amazon. Check it out.

#reading#books#prison#pruno#shanks#books & libraries#drugs#incarceration#skateboard#music#punk#freedom

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from the memoir Burden of Concrete by William S Hayes. Available now on Amazon.

By the fall of ’94, I had a healthy dope habit. The tarred talons of heroin had finally dug deep into my skin and my addiction to the drug was akin to being stuck in a cosmic black hole; I found there was a wretched force draining me of my light. That fall had been rough. I had been in Canada over the summer for some skateboarding events and came back to Seattle in time to get evicted. With nowhere to live, I separated from my friends and started gravitating toward the ever-increasing legions of dope fiends who were running the streets.

My tolerance was so low at first it was easy to get high. With time, however, it became evident I needed more. The thought of quitting never presented itself, but what did was the knowledge I needed money to pursue my endeavors. All junkies have a hustle, and that hustle is the deciding factor in the quantity of dope they can ingest—some sold drugs to support their habits, some sold their ass. There were a small percentage of hypes who held legitimate jobs but they were a rarity, and those gigs tended to disappear, causing the addict to venture into uncharted territory in the pursuit of the next fix. It didn’t matter whether it was robbing banks, robbing old ladies for their pension checks or robbing tip jars from coffee shops, it was all game and your game was only as good as how much money you could pull—and if your hustle was weak, you’d end up sick.

Prior to that fall I’d only get high on occasion, the main reason being that I rarely had any money. I loved the drug but had no hustle. The only time I ever got loaded was when I could trade some weed for dope, score for someone else or on the rare occasions I had money to spend. All of that changed after that summer. I suddenly found myself needing it to feel normal and obsessing over how I was going to get my next fix. I’d crossed the line.

I grew up watching the junkies on the streets. I was fascinated by the shit they did to maintain their habits. They were specters hiding in doorways and alleys, their eyes forever on the prowl for an easy hit and the cops waiting to take them down. Most exuded a criminality I found intriguing.

I’d been exposed to drugs at an early age and had every reason to be wary of the lifestyle, yet I was curiously drawn to them. When I was fifteen, I’d heard Lou Reed singing about heroin and “waiting for the man”, fascinated by his words. It was safe to say I was a junkie long before I stuck a needle in my arm.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from the memoir Burden of Concrete by William S Hayes. Available now on Amazon.

By the amount of time we’d been on the plane, my guess was we were over Kansas or Nebraska, and I knew it wouldn’t be long until the farmlands abruptly faded and were replaced by the mountainous terrain of the Rockies. The view of seemingly endless fields from 35,000 feet was mesmerizing in a sense, lending an elusive tranquility…one I knew I should appreciate because there wasn’t going to be much of it when I got to L.A.

A flight attendant walked down the aisle toward the back of the plane and I asked her for a cup of coffee as she moved past, breaking two rules by doing so. First, I leaned a little too close to the guard sitting next to me, and second, I had spoken to a civilian. I was nudged back in my seat with his elbow and told to shut the fuck up, but was rewarded a few minutes later with a hot cup of coffee and a smile. She made a move as if to pass it to me directly but thought better of it after observing the shackles on my wrists, and instead gave it to the officer in the aisle seat. I took the coffee knowing I’d won a small victory, then sat back and continued watching the earth pass below me.

It would’ve been a fair assessment to label me a small-time criminal, one without the balls or vision necessary for the big heist. While certainly lacking magnetism, the label hit the mark and personified my existence. To counter with a claim stating otherwise would’ve been absurd—my criminal record reflected a life of doing time for property crimes and minor drug offenses. Was I a victim of circumstance? To a certain extent but not really. The choices were mine and I had to live with the consequences.

I had heard stories from guys I’d done time with over the years who actually aspired to do time. With them, prison was a proving ground; a place where a man could earn a notch on his belt in his quest for the ultimate validation—making a name for himself on the streets and the respect that came with it. That was not the case with me. Going to prison was the price I paid in a high-stakes game of life on the hustle. If I won, I’d make enough money to support a debilitating drug habit; and if I lost, the desolation of living in a concrete hell.

When I was a kid, I spent a lot of time with my family camping along the Skykomish River in Washington State. Driving there and back, we’d pass a prison outside of the small city of Monroe and my young eyes would stay glued to its razor wire fences and guard towers, wondering what went on behind its walls. It was an ominous setting and one that left an imprint in my mind.

My perception had been shaped by the nightly news and movies like Escape from Alcatraz. I’d heard stories of prisoners getting raped, jailbreaks, executions, riots and murders. The tales were legion and believable, even though most came from sources who had, at best, only driven by a penitentiary a time or two. The violent reputation of the prison system preceding the firsthand knowledge I’d later discover shook me to the core, enough that when I was finally sentenced to do state time, I was scared to death. That fear might have been enough to set me straight, but a curious thing happened…I adapted.

I wasn’t one who got comfortable doing time, but I also never found comfort in the “real world”. There was a missing element in the way I thought, separating me from the vast majority of society. Having and keeping a job was foreign to me, as was paying bills, shopping for groceries and even something as basic as brushing my teeth. I used to attribute my lack of adherence to society’s rules as being dedicated to a code of recklessness, labeling anyone who thought different as fools, worthy of my ridicule. When my drug use progressed to the point of using every day, I discovered a lifestyle that offered me a semblance of purpose, however misguided it turned out to be. The bitter irony was that the freedom I found through drugs would ultimately put me in chains.

I asked the guard if I could have another cup of coffee, then sat back in my seat after he shook his head no. Looking out the window, I could see the jagged peaks of the Rockies rising from below, creating a natural barrier and effectively separating the East from the West. It wouldn’t be long until the sprawling city of Los Angeles was in my sights. And then it was off to the L.A. County Jail.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from the memoir Burden of Concrete by William S Hayes. Available now on Amazon.

By the amount of time we’d been on the plane, my guess was we were over Kansas or Nebraska, and I knew it wouldn’t be long until the farmlands abruptly faded and were replaced by the mountainous terrain of the Rockies. The view of seemingly endless fields from 35,000 feet was mesmerizing in a sense, lending an elusive tranquility…one I knew I should appreciate because there wasn’t going to be much of it when I got to L.A.

A flight attendant walked down the aisle toward the back of the plane and I asked her for a cup of coffee as she moved past, breaking two rules by doing so. First, I leaned a little too close to the guard sitting next to me, and second, I had spoken to a civilian. I was nudged back in my seat with his elbow and told to shut the fuck up, but was rewarded a few minutes later with a hot cup of coffee and a smile. She made a move as if to pass it to me directly but thought better of it after observing the shackles on my wrists, and instead gave it to the officer in the aisle seat. I took the coffee knowing I’d won a small victory, then sat back and continued watching the earth pass below me.

It would’ve been a fair assessment to label me a small-time criminal, one without the balls or vision necessary for the big heist. While certainly lacking magnetism, the label hit the mark and personified my existence. To counter with a claim stating otherwise would’ve been absurd—my criminal record reflected a life of doing time for property crimes and minor drug offenses. Was I a victim of circumstance? To a certain extent but not really. The choices were mine and I had to live with the consequences.

I had heard stories from guys I’d done time with over the years who actually aspired to do time. With them, prison was a proving ground; a place where a man could earn a notch on his belt in his quest for the ultimate validation—making a name for himself on the streets and the respect that came with it. That was not the case with me. Going to prison was the price I paid in a high-stakes game of life on the hustle. If I won, I’d make enough money to support a debilitating drug habit; and if I lost, the desolation of living in a concrete hell.

When I was a kid, I spent a lot of time with my family camping along the Skykomish River in Washington State. Driving there and back, we’d pass a prison outside of the small city of Monroe and my young eyes would stay glued to its razor wire fences and guard towers, wondering what went on behind its walls. It was an ominous setting and one that left an imprint in my mind.

My perception had been shaped by the nightly news and movies like Escape from Alcatraz. I’d heard stories of prisoners getting raped, jailbreaks, executions, riots and murders. The tales were legion and believable, even though most came from sources who had, at best, only driven by a penitentiary a time or two. The violent reputation of the prison system preceding the firsthand knowledge I’d later discover shook me to the core, enough that when I was finally sentenced to do state time, I was scared to death. That fear might have been enough to set me straight, but a curious thing happened…I adapted.

I wasn’t one who got comfortable doing time, but I also never found comfort in the “real world”. There was a missing element in the way I thought, separating me from the vast majority of society. Having and keeping a job was foreign to me, as was paying bills, shopping for groceries and even something as basic as brushing my teeth. I used to attribute my lack of adherence to society’s rules as being dedicated to a code of recklessness, labeling anyone who thought different as fools, worthy of my ridicule. When my drug use progressed to the point of using every day, I discovered a lifestyle that offered me a semblance of purpose, however misguided it turned out to be. The bitter irony was that the freedom I found through drugs would ultimately put me in chains.

I asked the guard if I could have another cup of coffee, then sat back in my seat after he shook his head no. Looking out the window, I could see the jagged peaks of the Rockies rising from below, creating a natural barrier and effectively separating the East from the West. It wouldn’t be long until the sprawling city of Los Angeles was in my sights. And then it was off to the L.A. County Jail.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from the memoir Burden of Concrete by William S Hayes. Available now on Amazon.

By the fall of ’94, I had a healthy dope habit. The tarred talons of heroin had finally dug deep into my skin and my addiction to the drug was akin to being stuck in a cosmic black hole; I found there was a wretched force draining me of my light. That fall had been rough. I had been in Canada over the summer for some skateboarding events and came back to Seattle in time to get evicted. With nowhere to live, I separated from my friends and started gravitating toward the ever-increasing legions of dope fiends who were running the streets.

My tolerance was so low at first it was easy to get high. With time, however, it became evident I needed more. The thought of quitting never presented itself, but what did was the knowledge I needed money to pursue my endeavors. All junkies have a hustle, and that hustle is the deciding factor in the quantity of dope they can ingest—some sold drugs to support their habits, some sold their ass. There were a small percentage of hypes who held legitimate jobs but they were a rarity, and those gigs tended to disappear, causing the addict to venture into uncharted territory in the pursuit of the next fix. It didn’t matter whether it was robbing banks, robbing old ladies for their pension checks or robbing tip jars from coffee shops, it was all game and your game was only as good as how much money you could pull—and if your hustle was weak, you’d end up sick.

Prior to that fall I’d only get high on occasion, the main reason being that I rarely had any money. I loved the drug but had no hustle. The only time I ever got loaded was when I could trade some weed for dope, score for someone else or on the rare occasions I had money to spend. All of that changed after that summer. I suddenly found myself needing it to feel normal and obsessing over how I was going to get my next fix. I’d crossed the line.

I grew up watching the junkies on the streets. I was fascinated by the shit they did to maintain their habits. They were specters hiding in doorways and alleys, their eyes forever on the prowl for an easy hit and the cops waiting to take them down. Most exuded a criminality I found intriguing.

I’d been exposed to drugs at an early age and had every reason to be wary of the lifestyle, yet I was curiously drawn to them. When I was fifteen, I’d heard Lou Reed singing about heroin and “waiting for the man”, fascinated by his words. It was safe to say I was a junkie long before I stuck a needle in my arm.

3 notes

·

View notes