Text

The Long Ships

I received this book as an early Christmas present and I read all five hundred pages of it before Christmas, during finals week. In fact, now that I’m thinking about it, this might explain my finals grades…

It seems that mass media doesn’t focus on Viking culture as much as other periods because it can be a bit too much to handle sometimes—all that raping and pillaging can get a little nasty. But Bengtsson cleverly situates The Long Ships around the year 1000, when Christianity swept up into the north and caused no small amount of bloodshed. Orm himself converts into a Christian in the course of the novel. And, to be frank, it makes him a much more sympathetic main character, at least to modern sensibilities—he chooses faithful monogamy, for instance, and settles down to be a farmer.

Between Bengtsson’s skillful choice of hero and his tone, Bengtsson turns The Long Ships into a comedic adventure. For example, here he observes Scandinavian life with a somewhat tongue-in-cheek air:

She had borne him five sons and three daughters; but their sons had not met with the best of luck. The eldest of them had come to grief at a wedding, when, merry with ale, he had attempted to prove that he could ride bareback on a bull; and the next one had been washed overboard on his first voyage. But the unluckiest of all had been their fourth son, who was called Are; for one summer, when he was nineteen years old, he had got two of their neighbors’ wives with child while their husbands were abroad, which had been the instance of much trouble and sly gibing, and had put [his father] to considerable expense when the husbands returned home.

The prefatory material, about the historical context, can be a bit hard to wade through; but after that, it was smooth sailing (no pun intended). The Long Ships is probably an adventure story that would appeal to fans of The Count of Monte Crist, although it’s a shorter tale that’s more lighthearted (and did I mention funny). Instead of studying Torts, I found myself laughing out loud while reading about some truly unfortunate souls, which cannot be recommendation enough for this book.

The Long Ships was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

0 notes

Text

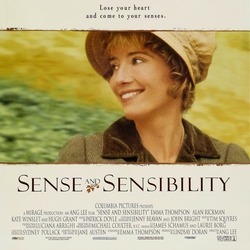

Sense and Sensibility (1995)

I’ve been on a long hiatus from this blog. Between applying to grad school, getting in, and wrapping up my first semester, I’ve had a strange schedule this past year, and maintaining the blog fell by the wayside. But now that it’s 2019, I’ve resolved to diligently write up everything I read; and everyone knows that New Year’s Resolutions never fail.

Sense and Sensibility was Austen’s earliest published novel, and it shows in many ways. The plot slows down to a snail’s pace in the middle portion of the book, as the sisters wait for plot developments to unfold. The romantic heroes, Edward Ferrars and Colonel Brandon, are not fully fleshed out, nor are their relationships with our female heroines described in detail, making their happy endings less convincing than they could have been. Furthermore, Edward and Elinor’s relationship is rescued by a deus ex machina, due to Edward’s ostensibly admirable integrity (and its accompanying passivity, in refusing to break off his engagement with Lucy Steele); meanwhile, Colonel Brandon’s relationship with Marianne is not only troubling from a modern perspective due to its two-decade age gap, it is also described as a “reward” for Colonel Brandon’s efforts, with Marianne being described as a “prize.”

Austen’s satirical powers are on full display here, but she didn’t temper her satire with as much warmth as in her other novels. Sense and Sensibility doesn’t successfully strike the same balance as, for example, Pride and Prejudice; there are simply too many obnoxious characters, that one wonders how Elinor had the patience to spend so much of the novel being even facially polite to such annoying characters; and although Austen’s famously comic scenes are present, not enough of Austen’s signature generosity and humanity shine through.

Interestingly, Austen reserves some of her kindness and forgiveness for Willoughby, arguably the main villain of the book. I understand the impulse; with Willoughby, Austen seemed to be trying to make a point about the importance of education and employment in building character, despite the natural gifts of nature that Willoughby possessed, and his inherent lack of malice. But Austen’s compassion seems to have been misplaced. Willoughby inspires too much moral repugnance to really be forgiven by the reader, and Austen spends far too much time rehabilitating him than is necessary, instead prolonging the novel and ending it on a strange note. Also, there was a very objectionable judgment that lay in Willoughby’s final speech; Willoughby (and Austen by extension) seems to imply that Eliza’s fate was partially her own fault, because she was not as bright nor as educated as Marianne—while Marianne, in possession of greater “understanding,” deserved better treatment. It’s a strange judgment to make, and the corresponding subplot in Pride and Prejudice was definitely handled better.

Having watched previous films by Ang Lee—The Wedding Banquet, Eat Drink Man Woman—I was unsurprised to find him directing this film about romance and marriage in the context of familial and societal restrictions. The film happily tries to clear up many of the problems I found with the novel; it deletes some of the extraneous characters who existed mostly for Austen to sharpen her wit; it gets rid of the misplaced attempt to rehabilitate Willoughby; and it fleshes out both Edward and Colonel Brandon (especially Edward, who becomes a much more sympathetic character here). I found Hugh Grant’s portrayal of Edward super adorable, actually, and I personally think that the alteration to Edward’s portrayal is what places the movie much closer to a romance than a drama and character study. However, the film is weighed down by the structure of the original novel—i.e., Edward only appears towards the beginning and the end, and is conspicuously absent in the middle.

Also, as a side note: I was glad to see how the film tries to be more class conscious, in showing how Elinor dealt with Dashwood servants and in giving the servants names. This was definitely a modern improvement.

Having ranted for so long about how the movie addressed the deficiencies of the novel, I should definitely mention some aspects of the novel that I really liked, even if it was difficult to translate to the screen. The novel’s main concern is, of course, not necessarily with romance, but with descriptions and judgments of people. What makes a good person, and what makes a good person admirable as well? Austen seems to suggest through this novel that a good person is kind and generous, warm-hearted, and truly modest; but what makes a good person admirable on top of these traits is intelligence, applied to hard work and industry through education and employment. Austen also makes digressions into taste and elegance, and how each is formed. This aspect of Austen’s novels is harder to translate to screen, and although the screenplay lightly suggests it sometimes, the movie necessarily focuses less on these themes and questions.

I also wanted to point out several visual cues in the film that I was disappointed to see. The “villains”—the unlikeable female characters—all had dark hair, including Fanny Dashwood and Lucy Steele, while the three Dashwood girls had beautiful blonde curls. I see this visual trope pop up again and again and … I just don’t like it. (Would Elizabeth Bennet have been blonde in movie portrayals if the book didn’t specify that she had dark hair?) I also found the casting of Charlotte Palmer very strange—the producers chose Imelda Staunton, who I think is a fantastic actress, but also about twenty years older at the time of the film than Charlotte Palmer in the novel. Not only was Staunton older, she was also costumed with gray hair and matronly clothes. The film seems to use beauty and youth to visually suggest “good” and “admirable” whenever possible, which totally voids the point of Austen’s novel. Charlotte Palmer is described as very pretty, and a young and recent bride in the novel—she’s kindhearted and generous, but that doesn’t prevent her from being a bit silly. Her beauty is integral to the reader’s understanding of her marriage to Mr. Palmer, someone who fell for her looks without really considering her his intellectual equal. Austen frequently contrasts this kind of external beauty with internal character—for example, in the character of Willoughby. (Since Willoughby’s handsome figure is described again and again, the film didn’t really deviate from the novel on that score.) But elsewhere, whenever possible, producers and directors still try to use visual shortcuts, equating (blonde) beauty and youth with goodness and (dark-haired) plainness and age with unimportance or even villainy. I have no words. It just ANNOYS me.

In a similar strain, I think one of the great strengths of Austen’s novels is her kindness and humanity, and I wish the film had added another line or two about Mrs. Jennings. Even though her character is a comic one, she gets her deserved treatment in the book, when Marianne regrets being rude to her although Mrs. Jennings has always been kind to her. It’s a dynamic that Austen clearly cared a lot about (see Emma and Miss Bates)—that finding humor in people who are a bit silly does not equal being kind to them. I wish the film had taken more note.

However, apart from these nitpicky opinions, I really enjoyed both the novel and film, and I think they each complete the other. The novel holds Austen’s wit and humor, and her insightful analyses of people and what make them tick; the film is a more enjoyable and balanced romance, with beautiful set-pieces and music. And both star a truly moving pair of sisters who love and value each other above all.

Sense and Sensibility (1995) was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

0 notes

Text

Killers of the Flower Moon

Looking at the photos featured in Killers of the Flower Moon, by David Grann, I realized that there were no Native Americans that I knew personally, and that this was also a direct result of all the atrocities imposed by the expansion of America’s empire.

This book was featured on a number of end-of-year book lists, for good reason: it’s an interesting look at an unknown corner of American history (I could not help but feel, while reading, that my AP U.S. History textbooks had been lacking). More importantly, it addresses a topic that even today we overlook—Native American history. I don’t think a lot of this omission is on purpose, of course; few people in the United States can now claim Native American ancestry, and ignorance begs ignorance. But it’s still unfortunate, and telling, how little we pay attention to the darker acts of the United States. Our history books pay a lot of attention to the role of the United States in declaring independence from Britain, and helping the Allies win WWII, and of course the fall of the Berlin Wall; but somehow they are much more reticent on the U.S. colonization of the Philippines, or Japanese internment, or the treatment of Native Americans.

(I was leafing through a copy of The Art of Political Murder, by Francisco Goldman, about the assassination of famed Guatemalan bishop Juan Jose Gerardi Conedera, when I learned that

I didn’t know anything about the Guatemalan Civil War; and that

The U.S. government basically helped the Guatemalan military dictatorship commit genocide against the Mayan people. This most certainly wasn’t in any textbook that I read.)

Returning to the subject at hand: I was astounded—perhaps naively so—at the extent to which the U.S. government tried to silence Native Americans. I really wish that there had been more focus on this, actually. Grann does a good job of explaining the case, the surrounding context, and the ensuing investigation and trials. However, while he does discuss the legal maneuvers that the U.S. used to control and siphon away the wealth of the Osage Nation, I think there was much more to explore here apart from what he sketched out.

In any case, the rest of the book is interesting and illuminating. Grann maintains a suspenseful narrative—one that eventually becomes quite sad. The book also successfully blended the personal and the political. Definitely recommended.

Killers of the Flower Moon was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#David Grann#FBI#Francisco Goldman#Killers of the Flower Moon#nonfiction#Osage Nation#The Art of Political Murder#true crime#Winter Lee

0 notes

Text

The Soul of the First Amendment

Floyd Abrams is a recognized expert on the issue of the First Amendment, and this book showcases the breadth and width of his knowledge. It was short read—but one that was packed with a lot of interesting tidbits for me to chew over.

In any case, Abrams focuses on a few specific topics in this short volume. What I found fascinating was how Abrams compares U.S. free speech laws to European ones, pointing out that the Bill of Rights is worded negatively, rather than positively; in other words, the Bill of Rights doesn’t grant rights so much as prohibit Congress from passing laws that infringe on such rights. When applied to controversial cases such as Citizens United v. FEC, I now see Abrams’ point that it is a dangerous slippery slope to start banning certain corporations—but not others—to express political speech. However, I do wish that Abrams—having arrived at this alarming conclusion���talked a little more about the legality of restricting or capping campaign donations; I would’ve appreciated a discussion on that a bit more.

Abrams also discusses the morality of publishing classified documents that were leaked to the press, among a few other topics, but those were a bit more black-and-white in my book. An interesting read.

The Soul of the First Amendment was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#Citizens United#First Amendment#Floyd Abrams#Greg Lukianoff#nonfiction#Supreme Court#The Soul of the First Amendment#Unlearning Liberty#Winter Lee

0 notes

Text

Marjorie Prime (2017)

I enjoyed watching Marjorie Prime as part of the Museum of Modern Art’s sci-fi film series, Future Imperfect: The Uncanny. This film, which was based on the Jordan Harrison play that was shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize, is directed by Michael Almereyda and stars Lois Smith and Jon Hamm.

The conceit is obviously a commentary on the increasing capabilities of artificial intelligence (and has been done quite done well in other works such as Black Mirror), but can also be read as a metaphor for memory itself and the way that memory is never static or accurate. In fact, memory is changed every time it is recalled, and is fact altered every time it is recalled by the circumstances in which the recall took place. This nugget of information would have had more of an impact if it had been delivered in a less self-important way by Tess, Marjorie’s daughter, as she sat broodingly over a piano. This was a missed beat that soured the film a lot for me personally.

Marjorie Prime betrays its origins as a play—sometimes in a good way, as the sharp dialogue reveals—but sometimes in a way that detracts from the film, with the lingering pauses and claustrophobic settings becoming a bit too much and ultimately distracting the viewer.

And while the original premise—that the Primes, the robotic representations of people who have passed away, can become repositories of memory that are both like and unlike their original versions—is explored with some interest and enthusiasm, it fails to really say anything new until the ending scene, which was surreal and unique but which also came too late in the movie.

“How great it is to have loved,” says Marjorie Prime at the end of the film, and I agree; the ending scene was a powerful reminder of the way that our loves outlive us. But apart from that moment, the film does not really discuss the relationships that it purports to explore; the film is exquisitely made with the best of intentions, but falls flat in some ways. A recommended watch if you are interested in the genre, although with some limitations.

Marjorie Prime (2017) was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#artificial intelligence#film#film reviews#Jon Hamm#Jordan Harrison#Lois Smith#Marjorie Prime#memory#Michael Almereyda#science fiction#Winter Lee

0 notes

Text

Encounters with the Archdruid

In honor of a (very) belated Earth Day,* let me review John McPhee’s Encounters with the Archdruid. McPhee was perhaps most famous for this book, which is a very well-written account, and—dare I say—well-balanced account of environmentalist David Brower and various meetings he has with those who are in favor of altering the natural landscape. What emerges is a portrait of Brower, the “Archdruid,” and the various arguments for and against keeping the earth pristinely the way it was before.

McPhee brilliantly showcased the nuanced approach of all his characters—or should I say, subjects. For example, as much I wanted to side with Brower the environmentalist, I found myself questioning his motive and his reverence for natural beauty. Is respect for natural beauty enough of an argument for preserving the earth, in the face of other compelling arguments? In fact, those who stand against Brower on various issues—Floyd Dominy, who advocated for dams and reservoirs and thus the alteration of the landscape of the Dust Bowl, for example—often live closer to “nature” than Brower himself does; they alter the landscape partly out of a deeper understanding of where and why human needs and nature’s needs conflict.

This was a very well-researched book; in all honesty, this was the sort of in-depth longform journalism that I wanted to study journalism for. In the days after finishing this book, I found myself debating whether or not I should take another gamble at becoming a journalist—and that (I hope) is a sure sign of the power of this book.

*I wrote this book review over two months ago, as you can imagine.

Encounters with the Archdruid was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#Charles Fraser#Charles Park#Cumberland Island#David Brower#Encounters with the Archdruid#environmentalism#Floyd Dominy#Glacier Park#Glen Canyon Island#John McPhee#longform journalism#nonfiction#Sierra Club#Winter Lee

0 notes

Text

The Name of the Wind

I can’t believe I am typing this right now: I hated this book.

To backtrack a little: it’s been awhile since I posted; between work and studying (and zoning out in front of the TV!) my tiny blog has unfortunately gotten short shrift.

I haven’t read much that would be suited to a short review either, in the past few months. I’ve been reading either short novels that are fun but forgettable, or longer and more complex works that I need to think more carefully about before I put pen to paper (metaphorically, of course).

One of the books that I thought would be easy to review was The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. It’s a straightforward fantasy novel, so it doesn’t require me to gather my thoughts before writing; but it’s also exciting and epic enough for me to gush about on my blog.

The thing is, The Name of the Wind is technically a reread for me. I think I was in the ninth grade or so when I read it for the first time, enjoyed it tremendously, and promptly forgot about it. I’m much older now, but I was still quite excited when I noticed it at the library a few months back, thinking it would be a fun and delicious book to sink into for a few days.

It turned out that Kvothe, the main character, was just downright unlikeable. Time really changes your perspective. To a high-schooler, Kvothe was perhaps just like every other fantasy hero: talented, special, destined to save the world, all that kind of crap. But with this reread, I noticed how annoying Kvothe was; how presumptuous, arrogant, and downright stupid he was at times.

With some more fantasy books under my belt, I also realized how mundane and unoriginal the plot is. There is literally nothing here that is new. We have a young prodigy who breezily excels at everything he puts his mind to. He falls in love with a manic pixie dream girl, a girl who forlornly flits in and out of his life because she is beautiful, vulnerable, beautiful, talented, and beautiful. Did I say beautiful?

Kvothe has some sympathetic tutors and some not-so-sympathetic ones. He learns some magic. He makes an enemy and dispatches of him in short order. He is the best singer around, the best lutist around, the youngest student at the Arcanum, you get the idea. With his stunning musical talents and his out-of-world magical talents, Kvothe saves the world and ascends to the heavens, to be embroidered onto the stars.

I kid there; I don’t remember what happens at the end of the book. I’m sure I knew it at some point—when I was in the ninth grade, perhaps—but I put this book down out of frustration at a certain scene. In this scene, Kvothe rescues a fellow student, a girl named Fela, by slinging her across his shoulder and carrying her out of a burning building. But Rothfuss doesn’t want you to think that he’s using the damsel-in-distress trope. No, Kvothe is a FEMINIST. He earnestly tells Fela that she wasn’t a damsel in distress—even she clearly was—and that she could have saved herself—even though she clearly didn’t.

I’m sorry, Patrick. You can’t have your cake and eat it too. You can’t demote women to hapless victims and then justify it by saying you didn’t mean to. (Did you also not mean to substitute flimsy cardboard cutouts for all the other women in your book, with different cookie-cutter variations of vulnerable, or beautiful, or matronly, or delicate? Were all of them accidents too?) Kvothe’s justifications are completely inadequate, because to any reader who has finished the novel, it is clear that there are no female protagonists who stand as a foil to Fela, as characters who are capable and worthy of respect. None. Why bother to include Kvothe’s speech in the first place, if it only serves to highlight its complete hollowness and the hypocrisy of the author? And as if to hammer the last nail into the coffin, Rothfuss uses the scene where Fela thanks Kvothe (for saving her) to open a small rift between Kvothe and his lady-love, Denna, because of jealousy. Not only does this book fail the Bechdel test, it actively sets women against each other.

In a scene which I marked down at the time (in fury) but can’t be bothered to find now, someone tells Kvothe that the object of his love, Denna, is very lonely: she’s so beautiful that men only have designs on her, and women only hate her. (This is doing a disservice to female AND male characters; is every character in this universe so shallow? Also, does Kvothe even notice how he’s also complicit in Denna’s isolation because of his sexual interest in her? He’s not exonerated here…) The book frantically stabs at “deep” and “meaningful” pronouncements; all I could do was try to stop rolling my eyes.

I was so frustrated, I went to Patrick Rothfuss’s Goodreads page to see what he had to say for himself. For someone who advises “college feminists” and also a “sorority,” he sure is keen to point out—on his author bio—that he is also a “skilled lover of women.” Is this a necessary testimonial to his writing skill? I don’t know, I’m just pointing it out. I usually don’t like ad hominem attacks but the misogyny in his writing was so blatant, I felt like it was necessary to point out the source.

What really galls me, and what REALLY drove me to write this review—since normally I don’t have the energy and time to review books I don’t even like—is that this book is well-received. Sure, it’s fantasy and not literary enough for mainstream reviews, but most magazines and outlets that have reviewed it have been pretty positive. Which is weird, considering this is pure fanboy wish-fulfillment drivel. Now, I don’t have anything against wish-fulfillment specifically; I think there’s definitely a market and need for guilty pleasures that I completely understand. There’s a problem, however, when products associated with teenage girls (Twilight, for example) get shot down as shallow and hysterical whereas those associated with teenage boys are hip and cool. This topic was mentioned a lot when Twilight came out and in my opinion it’s definitely applicable here. The Name of the Wind is a prime example; its quality is probably on par with Twilight (which I have no problem with), but it’s touted as the next great fantasy series, the successor to Harry Potter and the Lord of the Rings, et cetera, et cetera … despite having only trite plot points and a whole lot of ingrained misogyny papered over with thin and unconvincing protests. Please spare the fantasy genre such slander. This is far from the best that the genre can offer; in fact, perhaps it’s more like the opposite.

The Name of the Wind was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

0 notes

Text

The Death of Napoleon

The Death of Napoleon takes an interesting what-if and turns it into a contemplation on identity, success, and the meaning of life, if I can indulge in a grand claim for a moment. Simon Leys imagines Napoleon en route to Paris in disguise, having escaped his exile in Saint Helena, only to learn that his replacement has died. In other words, the ex-emperor Napoleon has been pronounced dead, and the man now struggling across France has no identity to return to.

The chasm between what Napoleon wants to become—or more precisely, return to—and who he is as an anonymous would-be melon farmer is achingly large…or so it seems. Identity as we often define it is structured on material belongings, social class, and most of all the beliefs of those around us. Yet without them, Napoleon still manages to carve out a life for himself—not as a conquering general on horseback but as a domestic melon retailer. Is this so bad? Leys asks. Napoleon dreams of glory—of a different identity—yet throws away the new life he has created for a fantasy. On his deathbed, it turns out that Napoleon has been living in such a dreamland that he has neglected the most mundane of details: he never learned his devoted lover’s name.

When the title refers to the death of Napoleon, who is it really referring to? Is it the emperor and erstwhile general, the melon businessman, or someone else besides? The death of Napoleon the idea—for the reader, for the French population, and for the humble man once names Napoleon as well? Leys’ surreal novella only offers more questions, its dreamlike images both absurd and hauntingly true. Definitely worth a read.

The Death of Napoleon was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#fiction#identity#magical realism#Napoleon#novella#Simon Leys#surrealism#The Death of Napoleon#Winter Lee

0 notes

Text

Hero (2002)

The story opens with sweeping vistas of an empty impersonal palace, beautiful gray and sepia tones entombing the characters. A lone man ascends the steps before the throne room to meet the king. He has vanquished three assassins who have formerly tried to kill the emperor, and the emperor will now personally thank him. As he sits before the king and recounts the story of how he overcame the deadliest assassins in the world, we—the audience—witness his story as if it is happening before our own eyes as well.

The director Zhang Yimou is famous for his arthouse films which have received attention in the West: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is the most famous of these, and incidentally also falls into the same genre as Hero, wuxia. With Hero, though, Zhang takes a different tack and uses the simple structure of myth and folklore to examine the nature of storytelling itself. To spoil the movie a little: it turns out that the unnamed hero initially offers up a false narrative. The king, sensing this, comes up with an alternative explanation: the hero, he counters, probably killed three assassins who were actually willing accomplices, all so that the hero can be honored by the king and can advance close enough to the king to assassinate him.

After these competing stories are told, the hero only smiles; no, he replies at length, that is not quite true either. And this time he presents a third story, one that is perhaps the truth of what happened.

As mentioned, Hero borrows from the folkloric tradition—the most obvious example would be in the triplicate structure, with the three assassins the hero defeats, and the three competing narratives. The elements of the story always remain the same: there is the king, the hero, the three assassins. Always, the first assassin to be killed is Sky, followed by Broken Sword and Flying Snow, who love each other but are destined for a doomed ending. Broken Snow is always injured or killed by Flying Snow, who then faces down the unnamed hero in a one-on-one duel in the desert, which she always gracefully and inevitably loses.

Not only are the plot elements and characters constant; even certain lines, phrases, or gestures repeat from one narrative to the other, as if we were viewing the previous narrative from a grotesquely distorted mirror. But the underlying implications of each narrative iteration are vastly different—a commentary, perhaps, on how the meaning of our stories is based less on the characters, or the plot, or even the dialogue, but rather context and our own deeply rooted beliefs about the hidden motives of those around us and how our world operates.

The stories also reflect some deeply held convictions the audience hold about the way stories or mythologies work. In the first rendition, the hero is an extraordinarily talented superhero who vanquishes villains—honorable villains perhaps, but with their own human faults they cannot overcome. In the second rendition, where the king uncovers the true motivation of the so-called hero, which is to assassinate the king, the hero is recast as a stone-hearted killer; the three assassins are in this case noble martyrs, stoically laying down their lives to save their country from being obliterated by the Qin emperor. But in the final version, things become more complicated. The truth, it seems, is never certain. The hero, driven by hate and revenge, disregards the advice he is given until the last bitter minute. Broken Sword and Flying Snow here are neither petty, scheming, and vindictive, but nor are they noble, wise, and self-sacrificial. Instead they are humans driven to stay faithful to their principles and hampered by their inability to show others their own vision—Broken Sword, especially—until it is too late, leading to a demise more tragic than any of their previous demises. The truth is more complicated—and more tragic—according to this work of fiction.

As a note, Zhang executes this meta meditation throughout with a beautiful palette. His devotion to monochromatic stills may have stood out as heavy-handed in a less stylized film; but here it adds a transcendent kind of gravitas, a welcome reminder of the fact that we are looking at fiction. His lingering shots add breath and thus vitality to the film as well; Asian films moreso than Western films focus on silence, the words unsaid playing just as large a role as the words that are actually pronounced in dialogue.

The ending—while technically a twist ending—was one which was well-established leading up to it; it is a satisfying conclusion. It does present a rosier view of history than is perhaps warranted. Zhang argues, firstly, that the Hero should not kill the Qin Emperor, who is promoting peace and prosperity by uniting the warring kingdoms of China; and, secondly, that the hero must die for his unsuccessful attempt on the king’s life, in order to uphold the rule of law throughout the land. To accept this as a legitimate and just ending is to have an incredibly strong conviction in the concept of empire and order—a surprising argument from a director with more nuanced social commentary in Raise the Red Roof and To Live, especially regarding despots and autocratic rule. Coming from someone who has just enthused about the Roman Empire and the Pax Romana in The Beacon at Alexandria, it seems almost hypocritical for me to argue anything else here; and so I will only point out that I am not a hundred percent convinced. While Zhang has stated that his film was meant to reference the entire world, not just China, the Qin idea of empire through conquest is less appealing than the willing tributary states of Rome in A Beacon to Alexandria and the soft cultural diaspora of early post-war America.

In any case I am, however, quite partial to the ideal of world peace, and the acknowledgment of the sacrifices it will take in getting there. Hero is a beautiful film that showcases this wistful wish, as well as a well-crafted tribute to storytelling and wuxia. Although it is mostly categorized as an action piece, I think it definitely transcends the genre and will appeal to anyone who loves film and storytelling.

Hero (2002) was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#action films#Chen Daoming#Hero (2002)#historical films#Jet Li#Maggie Cheung#Qin empire#storytelling#Tony Leung#wuxia#Zhang Yimou

0 notes

Text

The Beacon at Alexandria

Gillian Bradshaw is one of my favorite writers, and this work is – in my opinion – her magnum opus. I was originally planning to write back-to-back reviews for The Big Sleep and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, but instead I visited my parents for the Lunar New Year and started reading some of my old childhood favorites, still in the same bookcase that they always were. I was surprised. I felt an unfortunate resonance in the books that I read there. As a child, I loved stories about the fantastical struggle against intolerance and injustice, but I never imagined that the real world contained anything as terrible as what was depicted in fiction. And yet. Here we are. The Beacon at Alexandria is, I think, a perfect book to read against today’s political backdrop.

I first read this in college over the course of two days, staying up until 3 a.m. to do so. After this marathon, Gillian Bradshaw became one of my favorite authors, and I hunted down used copies of her books in old libraries since many of them (including this title!) seem to be out of print now. At the time, I loved The Beacon at Alexandria so much because of other reasons. The story is very much a classic YA novel, albeit crammed to the detail with historical detail and commentary. The main character, Charis, runs away to become a doctor. As a girl, she wouldn’t have been allowed to study medicine in the Roman Empire circa 300 A.D., so she disguises herself as an eunuch. Along the way, she encounters clashes of religion and faith, of politics and race, not to mention the personal obstacles inherent in her story. And yes, she grows up and falls in love—with a man who returns her love because he sees her spirit, intelligence, and determination.

All this sounds like a classic feel-good YA setup, which it is, and you should give this book immediately to whichever 15-year-old girl is in your life. The only word of caution is perhaps that Bradshaw expects her readers to be familiar with the overall context of the story, which is the fracturing of the Roman Empire into East and West and its eventual invasion and decline beginning with the Battle of Hadrianopolis (also known as the Battle of Adrianopole). Readers should probably familiarize themselves with the outlines of Roman history before they dive in, lest they feel discouraged. However, it is precisely this narrative theme that lends this book so much power, especially in today’s day and age.

It doesn’t take much to see the similarities between the late Roman Empire and modern-day America. Both are hegemonic world powers slowly sinking into decay, the structure of the world around them collapsing into chaos and war. I may be biased since I particularly identified with the character of Athanaric, who is the child of an immigrant (a Goth), born within the Roman Empire. Athanaric is fervently devoted to the Roman Empire and what it symbolizes: globalization, order and the rule of law, tolerance and diversity, and the prosperity that accompanies all of the above. As a child of an immigrant myself, I could not help but see reflected in him my love for America, hidden by layers upon layers of cynicism, but nonetheless there—my deep belief in America’s cultural commitment to law, if not honesty and integrity; my belief in its morally idealistic leadership—admittedly inconstant in its moral achievements, of course, but until 2017 willing to pay more than just lip service to uphold its ideals around the world. I admired America’s open arms to the world, and while in the fourth grade I memorized Emma Lazarus’s poem inscribed on the Statue of Liberty simply because I loved the beauty of the message and ideology that had brought my parents to these shores, to sacrifice so much for a dream. And … like Athanaric … I find myself reeling in a world order that has turned against all of these things, a world in which I have divided loyalties not because of my ideals—which are and shall always remain American—but because of origin and duty and compassion.

Anyways, to return to the book: this is a saddeningly relevant book in today’s political climate. As much as Athanaric loves the empire, all he can do is to uphold his small but significant role within it. He can only look in horror at the more shadowy byproducts of empire, at the problems of war and colonialization and abuse of power; but he can stay true to his ideals and his sense of justice.

To touch on another point; the main character, Charis, reflects yet another facet of today’s divided America. As mentioned earlier, Charis disguises herself as an eunuch in order to study medicine. But as she takes care to remind the reader, she is no sexless angel, no Florence Nightingale either. She wants a husband and a family to love, but she also wants to pursue the study of medicine; is it so difficult to have both? Quite sadly, as I reflected upon this story it seemed that this dilemma confronts many career women, even today. The penalization of women who seek to pursue extremely demanding, time-consuming careers at the same time as motherhood is frustratingly backwards. The book does a fantastic job of presenting Charis’s fears and doubts as a well-rounded, sympathetic, and moral main character, without caricaturing either her “masculine” or “feminine” traits, hopes, and aspirations. How many YA novels today accomplish that? Charis, even though she would have lived almost two thousand years ago, is drawn with sharper psychological care and insight than any dozen contemporary heroines today.

To end this rant on a quick note, let me repeat: The Beacon at Alexandria is a fun and enjoyable read that is also poignant and meaningful. I was surprised to find that it had only improved with time, and recommend it for not only teenage girls but also anyone interested in literary fiction or thinking about politics and its impact on the individual.

The Beacon at Alexandria was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#bildungsroman#Egypt#Gillian Bradshaw#medicine#Roman armies#Roman Empire#The Beacon at Alexandria#YA fiction

0 notes

Text

Dissolution

C.J. Sansom, who practiced as an attorney before becoming an author, was also a history Ph.D.—and this definitely shows in Dissolution, his debut novel and the first Matthew Shardlake mystery. His attention to historical nuance is enriching, his historical detail convincing. The turmoil of England under the rule of Henry VIII is beautifully rendered here—and what turmoil it is. England is being torn apart by political and religious unrest, and Sansom does a fantastic job of showing the different—and sympathetic—interests of all parties. The issue most pertinent to Dissolution is that of monastic life. Simplistically speaking, monastic life—which Cromwell will end by seizing the wealth of the monasteries—represents for monks a comfortable life in search of God and in pursuit of the transcendent through art and music, as well as a connection to Europe and the rest of Christendom; for Cromwell, it is a way to consolidate Henry’s power and by association his own; and for the poor, it is a corrupt system that feeds off their labor and exploits the weak, in particular women.

Shardlake’s idealistic blindness with regards to Cromwell was never quite convincing to me, but even he too at the end sees the bitter futility of reform, especially under the despotic tendencies of Cromwell (this series has also gotten me more interested in checking out Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy). At one point, Shardlake—who reaches this belated realization at the age of thirty-five—looks at some starving children and thinks to himself that even under the supposed reform of Cromwell, his adored master, they will continue to be starve and be exploited—a sad moment which I reflected still resonates through the modern day. For all that politics has been at the front and center of American life recently, and for all that we insist on change and progress—when the top echelon in power is replaced, who really benefits? I wouldn’t put my bet on the half-starved orphan.

In any case, this moral grayness stretches through to the ending of the book. To spoil the ending just a little, it turns out that the perpetrator of the original murder is more sympathetic than the murder victim. In order to get around this moral conundrum, Sansom allows the murderer to escape while preserving Shardlake’s position on the right side of the law. In another book this might have been annoying; but the resolution is still well-done, and in such a formulaic genre this little deferral to the ideals of justice and fairness can definitely be forgiven.

In general, the writing in this book is pretty good, if not great. I noticed at once the book’s similarity to classics such as Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, which other reviewers have noted as well (with Eco being the clear winner of the comparison). In my opinion, however, Eco’s purpose was much more didactic and his book more convoluted, with a different literary purpose. Dissolution is an enjoyable, accessible, well-written read for any lover of historical or detective fiction; and its haunting themes (the novel also ponders homosexuality and disability) and scenes linger for a while after the last page.

Dissolution was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#C.J. Sansom#detective fiction#Dissolution#Henry VIII#Matthew Shardlake#monasteries#mysteries#Thomas Cromwell#Umberto Eco

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Big Sleep

Philip Marlowe and his creator, Raymond Chandler, are famous for having reinvented the genre of detective fiction. Since I’m not personally familiar with the hardboiled genre, I have little to add to the discussion; I can definitely see it as a byproduct of the Depression … is all I can say. I read The Big Sleepsoon after I read John le Carré’s The Spy Who Came In From the Cold. It’s the dead of winter here in New York City; I guess it’s the season to be morbid.

What makes Chandler’s approach to death interesting is that, for him, Marlowe’s cynical attitude towards death is intertwined with a strain of appreciation for art and intellectualism, as well as both love (in its basest forms) and violence. Marlowe is not someone to be trifled with; you can argue he is strong in the most literal sense of the word; and yet he is an armchair philosopher who loves chess. He pretends not to recognize an offhand mention of Proust—but was that merely a front? He appreciates what we call the finer things in life; he lives. And yet his living is tainted with life, with the animalistic human needs that Marlowe—for all his superhuman elegance—is subject to. “Women made me sick,” says Marlowe, dismissing a second-rate seducer from his life; but at the same time he is filled with a loneliness that he rarely alludes to, which only makes an appearance at the end of the book:

On the way downtown I stopped at a bar and had a couple of double Scotches. They didn’t do me any good. All they did was make me think of Silver-Wig, and I never saw her again.

Death, art, love, violence—these all sit in uneasy juxtaposition with each other, these facts of life that contradict and co-exist. Is it any wonder that Marlowe is so tired?

The Big Sleep was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Cinema Travellers (2016)

I saw this film earlier today at the New York Film Festival. It was not a particularly dramatic film in either plot or presentation, but something of it has stayed with me through the entire day. Perhaps the topic reminded me of my own parents, who as children in semi-rural China many years ago watched open-air films with gaping wonder. But perhaps it’s also because the theme is universally captivating.

Technology & obsolescence Evidently, new technology and the disappearance of older ways of life are key themes that these directors explore. At first, the camera focuses lovingly on 35mm reels of film—on scratched projectors and worn-down trucks and grainy, uncentered footage. But the haunting score accompanies the unwilling but inevitable acceptance of change that these men must undergo; the reels are eventually replaced with digital technology, the projectors sold for parts. One of the film’s most moving scenes is actually the matter-of-fact disassembly of an old-time cinema projector, for the last time; first the moveable nuts and bolts come down, then the structure of the projector; lastly, the cylindrical covers and chasses of the film reels are thrown onto the scrap heap.

Still. Technological progress is accepted unwillingly—but gracefully. What is essential for all three main characters is their love of cinema—and they are willing to do whatever it takes for the show to go on. At the end, seventy-year old Prakash states confidently that, despite having dedicated almost his entire life thus far to projectors—building them, fixing them, improving them—he is ready to move on to the next big thing.

Movies & storytelling The film does not hesitate to tug on your heartstrings, with close-up shots of wide-eyed children enchanted with the screen. The cinema travelers seem to provide an essential service—the beauty and escape that movies seem to promise. This is a film about film, for film-lovers; and a poignant reminder that our lives are defined by narratives and the stories we tell. Our favorite cinema travelers recognize this, at least.

Conclusion Beautiful cinematography, lovely score, even-handed film about films. What’s not to like?

The Cinema Travellers (2016) was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#Amit Madheshiya#Author - Winter Lee#documentaries#Indian film#New York Film Festival#NYFF#Shirley Abraham#The Cinema Travellers

0 notes

Text

The Once and Future King

Let me preface this review with the disclaimer that The Once and Future King is one of my favorite books, ever. Perhaps I came to it young enough that its tidbits of wisdom were fresh and insightful, that its philosophical inquiries were curious and eye-opening. Or perhaps I love this book so much for a simpler reason: as one Goodreads reviewer puts it, this book is the pinnacle of all fantasy.

In a single story T.H. White manages to combine a retelling of the defining British creation myth, King Arthur, with a smorgasbord of other genres, including fantasy, literary fiction, comedy, and tragedy, while bringing out the best qualities of each genre. When I think of the word “epic,” I do not think of Gilgamesh, The Ring of the Nibelund, or Beowulf (although perhaps I should); I do not even think of The Lord of the Rings or Game of Thrones. I think of T.H. White.

Nationalism and war While the first book, The Sword in the Stone, was written much earlier, most of The Once and Future King was written concurrently with the beginning of World War II. It is not a spoiler to say that White was a pacifist. Horrified, he looked on as the most large-scale conflict in human history engulfed the world; in many ways his book is a very straightforward, desperate plea for peace.

The old King felt refreshed, clear-headed, almost ready to begin again. There would be a day … when he would come back to Gramarye with a new Round Table which had no corners, just as the world had none—a table without boundaries between the nations who would sit to feast there. The hope of it would lie in culture. If people could be persuaded to read and write, not just to eat and make love, there was still a chance that they might come to reason.

After spending an entire book describing, with certain nostalgia, a feudal society with a chivalric system of justice, White concludes that there is no need for force. He wonders and wonders—with touching bewilderment—at what the root causes of violence are. (As an aside, I wonder how much of his childhood colored his philosophy: “Sisters, mothers, grandmothers: everything was rooted in the past!” Arthur exclaims.) In the end, the old King—and perhaps White himself—cannot come to a conclusion, although he takes his readers on some beautiful political allegories involving ants, geese, and falcons. All he can do is imagine. Imagine there’s no countries…

Colonialism The essence of the story of King Arthur is the story of a man conquering Britain and imposing his view of civilization on those already there. To view such a story through a post-colonial lens is too obvious—especially since White kindly draws the parallel himself (he’s very obliging in pointing out exactly the topic he’s commentating on):

At the feast of Pentecost it was customary for the knights who had been on Table quests to gather again at Carlion so as to relate their adventures … It was as if some Inspector General of Police in a very distant part of Africa were to send out his superintendents into the jungle, asking them to come back next Christmas with all the savage chiefs whom they had brought to righteousness. For one thing, it often impressed the savage chiefs to see the great court, and they often went home reformed.

White is enamored of “civilization,” especially Western civilization of the Middle Ages, and doesn’t seem to see anything wrong with the imposition of this culture on others. At the same time, he also believes that violence is not only morally reprehensible but futile; he is a much bigger fan of the benevolent conversion of “savages” to Christianity. Why wouldn’t all other peoples of the world look up to British culture? Anything else would be incomprehensible.

Women & gender But if there is anything that truly interferes with my ability to enjoy this book, it’s in his depiction of women. White zooms in on Arthur, Guinevere, and Lancelot in the latter part of the story, and tries to paint psychologically complex portraits of them that motivate and explain the tragedy of their love triangle. However, Guinevere’s character lacks a certain plausibility, and her hysterically jealous relationship with Elaine is too exaggerated to be even halfway sympathetic. Elaine’s pitiful character is another one whose most salient characteristic—her pathetic and self-demeaning love for Lancelot—defies believability.

Points for effort, but it’s probably best for my love of this book that I don’t dwell too much on White’s difficulty with women. It’s even more frustrating that the King Arthur collection of legends has more than its fair share of proto-feminism (if only White consulted Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, or even Marie de France’s Lanval, rather than just Malory). Perhaps the character of Morgause—a stone-cold mother who alternates between neglect and abuse with regard to her children—sheds some light on White’s attitude.

Nature White’s love of nature permeates the entire book, and lifts the story with an unaffected lyricism—unaffected because it emerges from experience and genuine appreciation. For example:

The road, or track, ran most of the time along the high ridges of the hills or downs, and they could look down on either side of them upon the desolate marshes where the snowy reeds sighed, and the ice crackled, and the duck in the red sunsets quacked loud on the winter.

And so the book goes. White is also the author of a memoir which details his attempt to train a goshawk, and his love of animals, falconry, birds of any kind, English marshes, etc … all comes through with the clarity of love.

Style I can’t help but end this review with a selection of quotes. Call me old-fashioned, but I love White’s prose and literary style.

On sophistication:

The court had “knowledge of the world now”: it had the fruits of achievement, civilization, savoir-faire, gossip, fashion, malice, and the broad mind of scandal.

On childhood:

“I don’t snore,” replied the Wart indignantly. “You do.” “I don’t.” “You do. You honk like a goose.” “I don’t.” “You do.” “I don’t. And you snore worse.” “No I don’t.” “Yes, you do.” “How can I snore worse if you don’t snore at all?” By the time they had thrashed this out, they were late for breakfast. They dressed hurriedly and ran out into the spring.

On unrequited love:

Perhaps we all give the best of our hearts uncritically—to those who hardly think about us in return.

Conclusion Read it.

The Once and Future King was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#Author - Winter Lee#book review#Camelot#fantasy#Guinevere#King Arthur#Lancelot#T.H. White#Terence Hanbury White#The Once and Future King

0 notes

Text

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running

This memoir of Haruki Murakami came recommended by a close female friend; which was surprising to me, as all the people who have waxed poetic to me about Murakami before have been men. (Asian men, to be specific.) The recommendation came with an explanation: “I don’t really like his novels,” she said, “because they feel a little forced, a little flat. But I think in this memoir he was speaking from his heart, so I found it really inspirational.”

I loved this memoir not because it felt inspirational in the traditional sense of charting a way to “success” but rather because Murakami muses (and rambles) about the twinned concepts of writing and running (and living life, too). Murakami tears the romanticism away from writing novels and running marathons, although he is a successful performer of both. Running is painful, tiring; writing is difficult, even unrewarding.

The writing may be bleak from some perspectives, but to me it was fundamentally honest in its insight, which is hard to find. Perhaps this book even helped motivate the beginning of my blogging.

So here I am training every day for the Murakami City Triathlon in Niigata prefecture. In other words, I’m still lugging around that old suitcase, most likely headed toward another anticlimax. Toward a taciturn, unadorned maturity—or, to put it more modestly, toward an evolving dead end.

I will keep this mind: life is a dead end, so what I do love, I will love for the sake of itself. If I have decided that I love writing, then it will be an excruciating yet unexciting kind of love:

Writing novels, to me, is basically a kind of manual labor. Writing itself is mental labor, but finishing an entire book is closer to manual labor.

You sometimes feel this in Murakami’s works, which are less the creative diatribes of a genius and more the carefully eked out words of a sedentary observer. This essay collection is no different. Murakami is occasionally repetitive and the amount of sheer effort he puts in to both writing and running is claustrophobic. But. I would agree with my friend in that this is an “inspirational” book, in showing me the glitter among the mundane. Thank you for reminding me of my love, Murakami.

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#Author - Winter Lee#book review#Haruki Murakami#marathon#memoir#Murakami#novelists#running#What I Talk About When I Talk About Running#writing

0 notes

Text

Demian

Introducing a guest post from an outstanding friend & reader, Tommy Lache. Enjoy!

Let me begin this review with a confession: I did not pick this book up with pure intentions. I am adult enough to freely admit that I started reading a book because of a boy band. The boy band in question, BTS or the Bangtan Boys, is a Korean pop (read: hip hop) group that has recently garnered quite a lot of international recognition with their chart topping singles, “Save Me” and “Fire.” Perhaps you’ve heard of them. The story of how I fell into the deep dark hole of fangirling over this group of seven talented (handsome, perfect, wonderful…) boys is long and arduous, and out of common decency I will spare you the gritty details. The ultimate take-away is that BTS’s nerdy (read: adorable) leader, Kim Namjoon, once said Herman Hesse’s Demian was his favorite book and in a blur, I somehow found myself reading a $1.25 copy of the 1970 Bantam Book edition so old that it was falling apart in my hands.

I really wanted to love Demian, trust me, I did. I read Siddhartha and Steppenwolf my senior year in high school and I liked them well enough. Or, well, I liked them as much as one can like such moralizing books, but at least I found them inoffensive. I can’t honestly say the same for Hesse’s lesser known earlier work. Stylistically, the text is tiresome. Whether this should be attributed to the translation or to Hesse’s yet developing prose style, I am unsure. What I do know is that the novel often falls into long and onerous sentences punctuated with even longer irrelevant lists. Take, for instance, the second sentence:

The sweetness of many things from that time still stirs and touches me with melancholy: dark and well-lighted alleys, houses and towers, chimes and faces, rooms rich and comfortable, warm and relaxed, rooms pregnant with secrets.

I’m out of breath just from typing that. On other occasions, Hesse throws out abstract staccato gems like this: “The bird fights its way out of the egg. The egg is the world. Who would be born must first destroy a world. The bird flies to God. That God’s name is Abraxas.”

Despite the fact that I found the prose burdensome, I was prepared to persevere and concede to the stylistic conventions of the time. I thought: If you have no problem with Dreiser, or Proust, you can damn well read this Hesse! But what sets Demian apart from the magna opera of its era is simple: it’s just not that great. Emil is, in the simplest of terms, a spoiled whiny brat. His existential crises are as common as a rusty penny, he is prone to dramatics over the most banal occurrences, and his fragile rich boy psyche is gripped with petty anxieties. In other words, he’s just your average young person. However, there is little in the way that the novel is written that garners sympathy in the reader, or even interest. Often, his theatrics became so exaggerated and exhausting that I would have to put the book down and step away. What makes this book even less interesting is the fact that there isn’t much of a story to begin with. Emil lies about stealing apples, goes to boarding school, studies philosophy at the university, and then is drafted in the First World War. All the while, he philosophizes, and philosophizes, and philosophizes … you get the picture.

Frankly, Demian reads more like an abridged and annotated anthology of 19th Century Western philosophy than anything else. There’s a lot of Nietzsche sprinkled throughout the text, and occasional subtextual influences from Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard, but the most blatant is the presence of Jungian and Freudian psychology that pervades the book ad nauseam. If I had a penny for every time Hesse invokes some kind of Oedipal struggle in the novel, I could pay off my student loans. But truly, the problem isn’t that Emil is whiny and annoying, or that nothing really happens, or even that the text is so thoroughly inundated with existentialist ideology. It’s that none of it is done with any finesse. The book just doesn’t dazzle the way it should.

All this being said, there were two aspects of the novel that I found mildly compelling. The first was its subtle but thoroughgoing homoromanticism. In a way, Demian reads like a whirlwind teen romance. The titular character Max Demian’s slow burning seduction of Sinclair remains an undercurrent point of interest. They even kiss! Demian is an interesting enigma of a character, or at least the book wants you to think he is. The only other part of the book that intrigued came in the last two chapters, where the book takes a sudden change of pace. Out of nowhere, all of Sinclair’s whiny philosophizing seems to have a point. However, no matter how interesting these two minor parts of the story are, that’s all they are: minor parts of the story. Despite being the titular character, Demian is present through the course of the novel in only a handful of scenes, and when you reach the final chapters of the book and things being to seem worth pause, the book is suddenly and un-satisfyingly over.

It would be dishonest to say this book isn’t worth picking up. It is a Hesse after all, and he is not Thomas Mann’s favorite writer for nothing (special note: the edition I read includes an impassioned introduction written by Mann). Demian is a beloved book to many an individualist and existentialist alike. If that’s your thing, maybe give it a try. I will maintain, however, that everything Demian has to offer has been done better, and with much more style and interest in Wilde, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, and Bronte. Or better yet, just read Steppenwolf instead.

Demian was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#Author - Tommy Lache#Bangtan#bildungsroman#BTS#BTS Wings#Carl Jung#Demian#Existentialism#Freud#Herman Hesse#Jung#Kim Namjoon#Nietzsche#Philosophy#Psychology#Steppenwolf#Thomas Mann

0 notes

Text

Snowden (2016)

I watched Snowden a few days after its release, in a dark Brooklyn theater with tattered VCR cases in the lobby. When I emerged into a sunny September Saturday, sampling wares at a nearby food festival, the dark underbelly of government conspiracy and the looming threat of terrorism alike seemed far removed from my life.

But that night, an unobtrusive corner of New York only a few miles away would be bombed.

Snowden (2016), directed by Oliver Stone, tackles the timely story of Edward Snowden, former NSA contractor, whistleblower, and American expat. Joseph Gordon-Levitt (I’ll admit to a bias here), meticulously plays Snowden with an understated touch; it is surprising how ordinary and Everyman-like Snowden seems, considering that the film is essentially a character study. As expected of its genre and director, the movie is a well-crafted historical drama; but its main takeaways are more likely to be about the main character than the important issues he grapples with. Which is a shame, because I would have loved to see more exploration of ideas and ideology.

U.S. hegemony At one point in the film, Snowden outlines the different ways the U.S. has hacked into foreign systems in an effort to preemptively compromise them should an ally turn on us. He comes to the sad conclusion that the U.S. government only serves to protect its own interests.

But that isn’t inherently wrong in and of itself. The U.S. can and should protect its own interests; it is natural to do so. There are harder questions to answer: for example, where should the line be drawn? Intelligence and counter-intelligence has always been an integral part of diplomacy and international relations, and it is foolish to pretend that they don’t exist. But if we allow a little bending of the rules here and there … how much should we “allow” the rules to bent? That is a much more tangled knot that would be interesting to unravel, but the film.never developed this debate.

The other natural follow-up question is, should the U.S. protect other countries’ interests, even against their will? However, I suspect that is a question for another time.

Privacy Edward Snowden argues passionately for the right to privacy, of course, and the entire film revolves around the premise that he was morally impelled to become a whistleblower. Sitting in the audience, I found it easy to become sympathetic to Snowden’s fierce defense of his ideals. But the world is not a simple place and that night’s attacks proved it even more so. We will always have to make a tradeoff, and the tradeoff happens every day, every moment.

Benjamin Franklin is famously quoted as having said that “Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.” But dig a little deeper, and things start to become grayer. The “liberty” that Franklin is defending is actually the right to enact legislation; after all, government is the essential glue of our social contract. Snowden warns against tyranny from the abuse of power, but he has to draw a clearer line between those who abuse the power and the entirely legitimate and even essential channels through which they do so.

Gender roles Ah, here we go. My Shakespeare professor was always amused by how much I incorporated gender issues into my essays; but what can I do? I live in a world that is still very much segregated by gender.

What I wanted to talk about primarily was the central relationship in the film, that of Edward Snowden and his girlfriend Lindsey Mills (Shailene Woodley). Mills helps Snowden out with the socializing; she balances Snowden’s depressive moods; she is kept in the dark for the entire film.

A.O. Scott notes in his New York Times review that

As ever, Mr. Stone’s interest in women is limited. They provide pictorial variety and emotional complication … Ms. Woodley has more screen time than Sissy Spacek in “J.F.K.” or Joan Allen in “Nixon,” but she is, in effect, portraying an updated version of the loyal, long-suffering, uncomprehending wife.

Except there is no update, and she is exactly that: an old repetition of a character we are all bored with. The real clincher is that none of the other women in the film are interesting either; of the three or four speaking roles women have, the main one goes to the character of Laura Poitras, whose documentary Citizenfour basically helped make this film possible. Yet Poitras has very little speaking time and almost no emotional arc; she doesn’t even suffer the emotional crises and character growth that others in the frame story have to undergo. She is just there, holding the camera, but completely irrelevant to the emotional weight of the story—even though she was a vital member of the team that launched Snowden into international fame and infamy.

To make the objectification complete, at one point Snowden admits that he has used NSA programs to spy on his own girlfriend out of jealousy. And apparently it is this breach of privacy that has set off Snowden’s paranoia. The trope of the femme fatale, seducing the hapless hero into uncharacteristic mistakes, is lurking not-so-subtly under the surface here.

Where are the women in this film? While it is admittedly based on a real story with perhaps few major female roles, this fictional film has surprisingly little imagination. And, even when given interesting female characters to work with, Stone falls woefully short.

Conclusion Snowden is an interesting watch, although many have suggested skipping it and watching Citizenfour instead. After all, the point of a fictionalized account is that it has more room to play with what-ifs, to think about the implications of the story. Snowden is much too single-note for any nuance.

Still: well-made, with an experienced director at the helm, Snowden is definitely a safe bet. Its two-hour-long running time is a little too much, but I guess I could stand to watch Gordon-Levitt on screen for more than that.

What are your thoughts? Comments? Let me know below!

Snowden (2016) was originally published on Friends, Romans, Countrymen

#2016 films#Author - Winter Lee#biographical films#biopics#Citizenfour#Edward Snowden#film review#historical drama#historical films#Joseph Gordon-Levitt#NSA surveillance#Olive Stone#Shailene Woodley#Snowden#terrorism

0 notes