Must I write something here? I mean, really, must I? she/her

Last active 2 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Rammstein as Ace Ventura (or Ace Ventura as Rammstein?)

Schneider:

Flake:

Till:

Paul:

Richard:

Oliver:

#rammstein#christoph schneider#richard kruspe#till lindemann#paul landers#oliver riedel#flake lorenz#ace ventura#r+ memes

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

So Schneider used to like most of Richard’s posts on Instagram and he hasn’t in a while and is apparently no longer following him either. But Schneider does still have an account. Did something happen?

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Der schönste Moment war der, wenn am Sonntag 17 Uhr das letzte Schiff abgefahren ist. Dann waren alle Wochenend- und Tagesbesucher weg und dann hatten wir wirklich das Gefühl, die Insel gehört total uns. Dann sind wir an den Strand gegangen und haben gebadet und waren oft die einzigen im Wasser. Haben dann uns noch irgendwie ein Kartenspiel am Strand gemacht oder uns die Sachen bemalt. Sind, wenn der Klausner offen war, noch was essen gegangen und haben uns dann in unseren Schlafsack gelegt und das war eigentlich wirklich… die schönste Zeit in meinem Leben.“ (x) – “It was the best moment when the last ship departed on sundays, 5pm. Then all weekend and day tourists were gone and we really felt like the island was ours. Then we went to the beach and bathed and we would often be the only ones in the water. We made card games or painted on our clothes. If the Klausner was still open we would go and eat there, then lay down in our sleeping bags and that was truly… the best time of my life.”

233 notes

·

View notes

Text

there's been an on purpose at the accident factory

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

The events in your story must be believable...

No, I don’t mean curb your imagination and never write fantasy, sci-fi, or any other sort of speculative fiction. No, I don’t mean avoid writing the type of romance so many of us wish we could experience in real life. What I mean is that what happens in your story must be believable within the context of the story. When I was a creative writing student in university, I disagreed with many of my professors’ rigid rules, but one piece of advice I always agreed with was this one.

Somebody in class would write a story, a few of us (or more) would call bullshit on the sequence of events, and they would reply, “But this actually happened!”

Honestly, it doesn’t matter if what you’re writing about actually happened. It’s a cliché, but truth really is often stranger than fiction, and it can be interesting to hear those anecdotes when you’re talking to someone in real life. However, when you’re reading a novel or even just a short story, it doesn’t work the same way. The events of the story have to follow some sort of internal logic. Here are some antitheses to a story’s internal logic.

1) Character inconsistency. Characters should be complex, and they often change over the course of the story, but if, out of nowhere, a character does a complete 180 with no possible motivation for those actions, readers will be thrown. Many great plot twists come from characters turning out not to be who we thought they were, but remember that characters should be like real people rather than plot devices, three-dimensional rather than flat. Their actions have to make sense; there must be a reason for their actions beyond moving the plot forward because you, the author, want or need it to move forward.

2) Unrealistic consequences. This is one of my personal least-favorite things to see in a story: when a character makes a huge (and often very damaging) decision, and there is hardly any fallout. I’ve seen it most often when the main character gets away with things that no one would ever be able to get away with so cleanly, but the main character can because they’re supposedly special. (Hint: they’re not.) People don’t forgive hurtful actions easily, and, except in the world of the extremely rich and powerful, egregiously bad decisions don’t go unpunished. Even if the reader identifies with the main character (and, naturally, we want things to go well for characters we identify with, just as we want them to go well for ourselves), this is not satisfying. It feels like something is missing, because it is.

3) Deus ex machina. This is Latin for “God out of the machine,” and it refers to “a plot device whereby a seemingly unsolvable problem in a story is suddenly and abruptly resolved by an unexpected and unlikely occurrence” (I got this part from Wikipedia. Don’t judge me! They sum it up well!), as if God or a higher power of some sort just popped in out of nowhere fixed everything for the characters on a whim. Real-life instances of deus ex machina are cool to hear about precisely because they’re so unbelievable, yet they really did happen, and it just adds to the mystery of the universe. In fiction, deus ex machina is just anticlimactic. There’s nothing rewarding about reading your way through a character(s)’ mammoth struggles and having none of it pay off or come to anything because an external factor, which has never appeared in the story before, suddenly enters and ties things up neatly. If you must use deus ex machina, do it sparingly and with small events rather than the main conflict or showdown of the story.

Any one of the above, and especially a combination of them, will lead to more plot holes than a reader can willingly accept. These shortcuts aren’t worth the substance they remove from what could be a great story.

98 notes

·

View notes

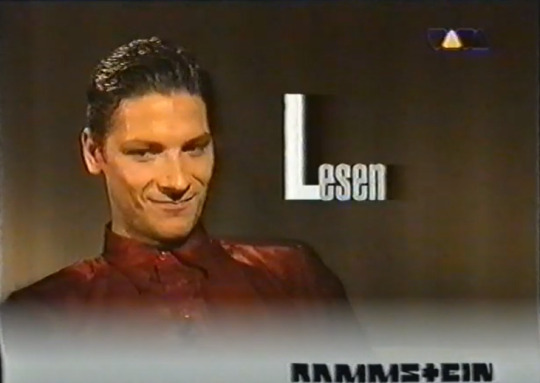

Photo

The most deadpan tone of voice but the cheekiest facial expressions in this interview.

#christoph schneider#long hair schneider#rammstein#how does one achieve this level of sexiness what is the secret

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Woman in the Refrigerator

TW: MENTION OF RAPE AND ASSAULT

I had never heard this strange term until I read a review for Thor: The Dark World several years ago. The review stated that the death of Frigga, Thor and Loki’s mother, was merely a plot tool to motivate Loki to help Thor kill the nefarious Malekith and his band of Dark Elves. That was Frigga’s main purpose in the story — to die, to set up another character’s moment in the sun. She was shoved in the refrigerator.

I once got into a huge argument with a guy over this trope. He wanted me to read his favourite Batman comic, in which Commissioner Gordon’s daughter, Batgirl, is brutally assaulted and raped by the Joker. Joker wanted to prove that even a man as upright as Gordon could break and turn into a villain if he experienced as much anguish as Joker had in his life. His entire reason for hurting Batgirl was to hurt Gordon. And Commissioner Gordon was on the verge of breaking, until Batman essentially told him to be the bigger man, not to give in and be what the Joker wanted him to be. Batman assured Gordon that he would take care of the Joker. I told this guy that I didn’t want to read the comic book because I was really tired of the woman in the refrigerator trope: when a woman is raped, assaulted, or killed to motivate a male character into action. When a woman’s sole purpose in the story is to be brutalized and nothing else. For me, as a woman, it’s a disheartening trope to read, the idea that men see us as nothing but pieces on a gameboard.

Now, I’m not faulting anyone who wants to read or watch stories that have this trope. Goodness knows, I like some movies that have this trope (though usually to a much lighter extent). But I shouldn’t be forced to consume materials featuring this trope if I don’t want to. And this guy I was talking to legitimately got SO ANGRY that I didn’t want to read his favorite comic book and tried to call bullshit on everything I was saying about the trope. As an added and unnecessary measure, he tried to diminish the female experience of being sexually harassed, threatened, assaulted, etc., but let’s not focus on that part right now. Let’s focus on this part: he stated that the trope happens just as often the opposite way, that male characters get hurt and it motivates female characters into action. I’m sure that it does happen occasionally in his reading materials, but in the vast majority of the media that people consume all the time, it doesn’t. The woman usually needs to be saved or avenged or whatever makes the man seem like a hero. And also, male characters are almost never raped. With female characters, it’s fairly standard. Argue all you want about how a male character getting beaten up is just as bad as a female character being raped, but the fact of a female character being raped because she’s female says, I believe, enough on its own. It’s a uniquely psychologically and physically torturous thing to endure. As a woman, if I were given the choice, I would rather be beaten up, and I’m sure many, if not most, people of any gender would be in that boat with me.

I won’t say to you, “Don’t write the woman in the refrigerator trope because it’s BAD.” At least, not in the same way I’ll say, “Don’t TELL with your writing. SHOW.” All I ask is that you think long and hard about whether it’s really necessary to have the trope in your story or if you can think of another way to have your male character rise to the occasion. Think about the impact on a reader, especially a female one, who may have been traumatized at some point and is now forced to relive it and has been conditioned to think of themselves as a victim, like the only part of their identity worth noting is this one terrible thing that happened to them.

I can’t finish this post without addressing another trend of late. The brutalization of a side female character motivating the female main character into action. At first glance, this may seem like just a another facet of the woman in the refrigerator trope, but it isn’t, and I’ll tell you why. It’s because even though it wasn’t the female main character who was assaulted or murdered, it just as easily could have been. In the Batman comic, it never would’ve been Batman who was raped and assaulted by the Joker. In Taken, it never would’ve been Liam Neeson’s character who was kidnapped and sold into the sex trade. And the reason it wouldn’t have happened is that they are grown men. The YA thrillers featuring a teen girl searching for her best friend’s or her sister’s murderer? In real life, that teen girl could have been in the wrong place at the wrong time like her loved one was, could have dated or rejected the same guy, or whatever situation led up to the murder, and the exact same thing would have happened to her. And it would have happened because she, too, is a girl. Because it’s easier to be a total coward and attack someone who isn’t as physically strong as you are rather than attack a man who stands a better chance at fighting back.

When a female character doesn’t let brutality towards other women scare her out of action, when it motivates her to seek justice and protect herself and other women, it can be very satisfying and empowering for a female reader. After all, who of us women hasn’t seen a story of a raped or murdered woman on the news come to a completely unsettling conclusion and wished we could take matters into our own hands?

#trigger warning: mention of rape and assault#writing tropes#writing rants#writing tips#writing advice

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When s/he does this look.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mental Illness in Fantasy and Science Fiction

So this is probably going to be short and ranty and not very eloquent, but one thing that really bothers me is the lack of mental illness represented in science fiction and fantasy. I get that there is typically already so much going on in those kinds of novels that it would be difficult to effectively tackle issues of mental health, but I’m not necessarily asking for it to be a major plot component; I just want its existence acknowledged where appropriate. I mean, how many absolutely terrifying or devastatingly sad events happen in this kinds of novels? A lot. And yet somehow, the characters never have panic attacks, never fall apart from grief, nothing. The plot just keeps moving forward. Is that realistic? And when a character does show a significant amount of fear or sorrow or an inability to act, that character is deemed “weak,” if not within the novel then by the novel’s readership. (I’ve seen it. Trust me.) But I ask you, if you had just lost someone you loved or if you were faced with imminent death, how would you react? Wouldn’t you be like some of those “weak” characters, too? I know I would, and the kind of reaction I would have, as a person with mental illness, being dismissed as a sign of weakness rather than as a sign of humanity has honestly hurt. I’m sure I can’t be the only person out there who feels that way, who would like to see more representation of mental illness in speculative genres and who would breathe a sigh of relief at seeing a realistic portrayal of grief and panic.

I hate to say it because I really do not like Sarah J. Maas’s writing, but the only instance that comes to mind right now of realistic fear portrayal in fantasy comes from A Court of Thorns and Roses. The main character, Feyre, is facing off against the villain’s challenges, the first of which is almost certain to get her killed, and she states in her narration, “My bowels turned watery.” In other words, she feels like she’s going to crap herself from fear. That line resonated with me because I’ve had that feeling before in the midst of panic attacks. It’s not a romantic line, it’s pretty gross, but damn if it doesn’t showcase actual emotion effectively.

Rant over (for now).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s talk about effective plot twists

Much of the time, readers can see plot twists coming, and it doesn’t necessarily hinder their enjoyment of what they’re reading. They’re still entertained by the unfolding of events. However, if a book is marketed as “twisty,” and it really isn’t so much, that can be disappointing.

Personally, what gets me as a reader (and viewer, in the case of movies and TV) is an additional plot twist after the seemingly “big twist” of the story has been revealed.

The example I’d like to use here (which will include spoilers) is the 1996 movie Primal Fear, starring Richard Gere and Edward Norton. ***Trigger warning for sexual assault in this movie, and I’m going to talk about it a bit here.***

Gere’s character, Martin, is an attention-seeking lawyer who is well-known for winning cases on legal technicalities. When a Catholic archbishop is murdered and police arrest young Aaron (Norton’s character), Martin offers to represent him pro bono. Aaron is a former altar boy who greatly admired the archbishop. He is sweet and meek in nature, and he has a severe stutter; Martin doesn’t believe such a person is capable of committing murder.

Then, a videotape emerges showing the archbishop forcing Aaron, his girlfriend, and another altar boy into sexual acts, which would provide motive for the murder, but could also elicit sympathy from the jury during the trial. Martin confronts Aaron about withholding the truth from him, and Aaron breaks down crying.

Twist #1: At this point, Aaron’s personality abruptly shifts. He manifests a new persona, the violent and volatile Roy, who confesses to the murder of the archbishop. Aaron shifts back into himself, with no recollection of his words and actions as Roy. The psychologist appointed to the case believes that Aaron developed a personality disorder at some point as a result of years of abuse at the hands of his own father and the archbishop. It’s too late to enter an insanity plea because the trial is already underway.

This is a good twist on its own. We’re already rooting for a seemingly harmless young man not to be convicted of murder, and then we’re given an alternate and scary persona to reckon with. However, given the circumstances, we can still root for this character.

As the trial goes on, Aaron testifies to his sexual assault at the hands of the archbishop, but during a harsh cross-examination by the prosecutor, he transforms back into Roy. As Roy, he attacks the prosecutor, threatening to snap her neck. As a result, Aaron’s trial is dismissed in exchange for a bench trial, wherein he will be declared not guilty by reason of insanity and put in a psychiatric hospital.

Afterward, Martin visits Aaron in his cell to let him know about this. As we know from before, Aaron never remembers his times as Roy. Yet, as Martin is leaving, Aaron tells him to tell the prosecutor that he hopes her neck is okay. But wait a minute. How would he know that he attacked her and threatened to snap her neck if he couldn’t remember the incident from court? Martin questions him, at which point...

Twist #2: Aaron reveals that he faked the personality disorder to escape a murder charge. He then brags about murdering the archbishop and also his girlfriend from the video. When Martin asks if there ever was a Roy, he replies “There never was an Aaron.”

This is a great second plot twist, especially since it is the resolution of the story. Nothing else really happens after this, and that’s what makes it especially chilling. We may have been able to sympathize with Aaron/Roy killing someone who repeatedly sexually abused him, but for him to kill a young woman who suffered the same things he did? There’s no ambiguity there; Aaron is a psycho. And of course, because of double-jeopardy, he can’t be tried again for the same crime, even though he has admitted to it. Though he may have been remanded to a psychiatric hospital, he essentially got away.

I think this twist-layering strategy really works well. Give the readers a twist or conundrum that is compelling enough on its own, whether or not it is predictable. If it is morally or emotionally complex, that will typically be enough to make readers stay. If you really want to bowl them over, add one more twist, something plausible but unexpected in light of the existing heavy conflict. Heck, add more than one if you can. Why not?

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

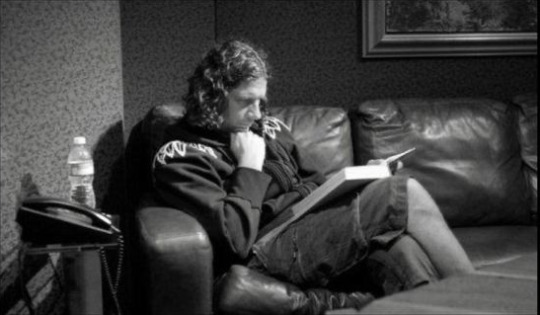

Our bookworm <3

#christoph schneider#Rammstein#till lindemann#first pic i'm imagining schneider using his book to shoo flies away from till's mouth

33 notes

·

View notes