Arts and media collective dedicated to the remembrance, preservation and re-evaluation of Mizrahi Jewish cultural consciousness.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

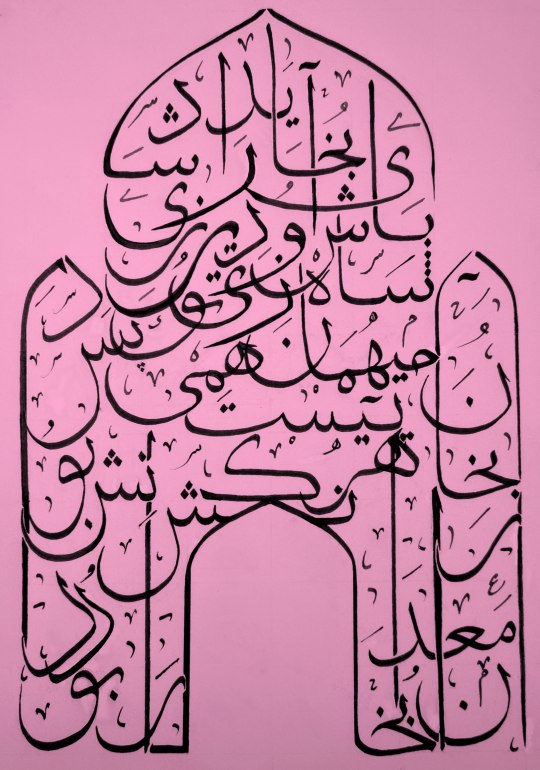

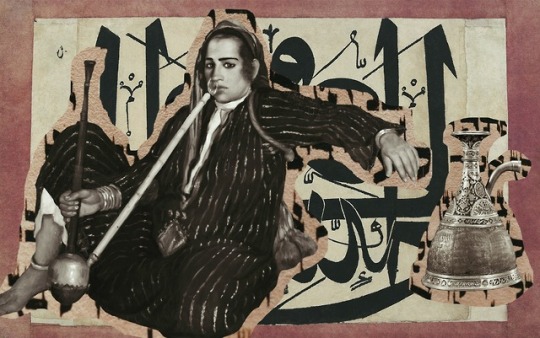

Writing Between Tongues: The Calligraphy of Ruben Shimonov

Ruben Shimonov’s hybrid identity as a Bukharian, Sephardic, and Mizrahi Jew continuously informs his work as a community builder, educator, and artist. He is the Executive Director and co-founder of the Sephardic Mizrahi Q Network (SMQN), a New York City-based grassroots organization building a vibrant and supportive community for LGBTQ+ Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews. Between his work with SMQN and the Muslim-Jewish Solidarity Committee, Ruben has designed an innovative interfaith Arabic-Hebrew calligraphy workshop that he has facilitated in numerous community gatherings around the world.

Interweaving Arabic and Hebrew, Ruben’s multi-sensory calligraphy installations, which include audio, video, performance, and interactive components, create a space for these two Semitic languages to encounter one another in familiar and new ways. Often focusing on cognates, his work explores the ways in which these languages, their complex histories, and their rich ties to spirituality intersect and interact with each other. He also frequently incorporates another West Asian language that is dear to his identity— Farsi.

“veyasem lekha shalom” - “May G-d grant you peace”

Passages about the city of Bukhara, taken from the classical Persian poetry of Rudaki and Rumi-

“oh Bukhara! be joyous and live long! your king comes to you in ceremony.” (Rudaki)

“Bukhara was a mine of knowledge, of Bukhara is he who possesses knowledge.” (Rumi)

A verse from Shir Hashirim (the Song of Songs) - “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine,” in Hebrew and Arabic.

“eshq” - “Love” in Farsi

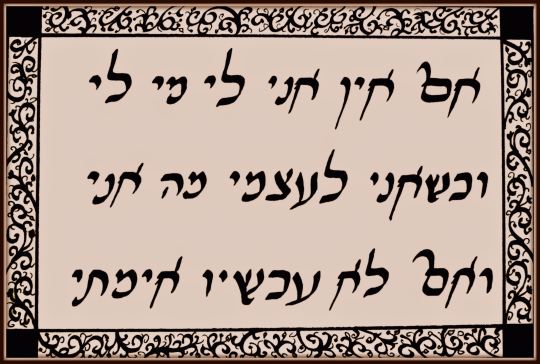

A verse from Pirkei Avot - “If I am not for myself, then who will be for me? But if I am for myself, then what am I? And if not now, when?”

“ani” / “ana” - The pronoun “I” in Hebrew and Arabic

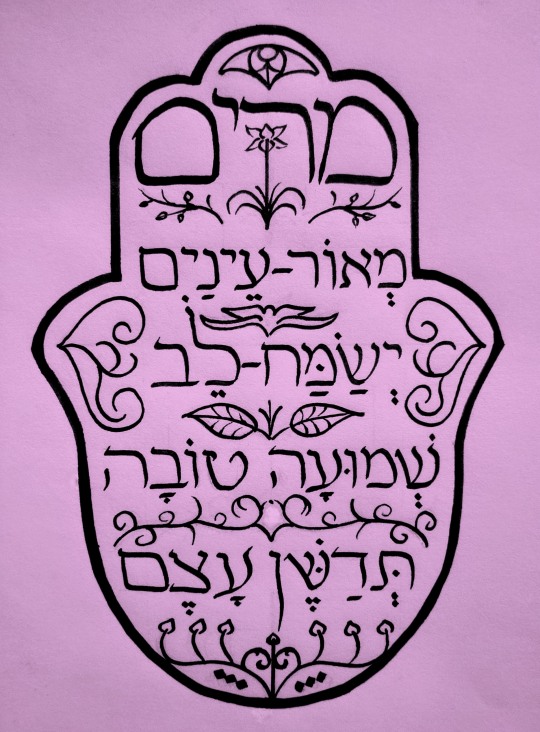

The Jewish name “Miryam" and its corresponding verse from Mishlei (Proverbs) - “The light of the eyes makes the heart happy, and good news fattens the bone.”

Above: "bri’ut” - “Health”

Below: “gam ze ya’avor” / “in niz bogzarad” - “This too shall pass” in Hebrew and Farsi

Two appropriate wishes for the world this season.

Ruben Shimonov is a Jewish educator and community builder living in New York City, by way of Seattle and Uzbekistan. Prior to establishing SMQN, he was the Director of Community Engagement & Education at Queens College Hillel. Ruben has lectured extensively on Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry, including at Limmud conferences in New York, Seattle and the U.K. He serves as Vice-President of Education & Community Engagement on the American Sephardic Federation's Young Leadership Board, as well as Director of Educational Experiences & Programming for the Muslim-Jewish Solidarity Committee (MJSC). His calligraphy (linked here) has been featured in various exhibitions across New York City.

Published April 3, 2020.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mahane Yehuda / מחנה יהודה

By Gabriella Kamran

Photo collage by Sophie Levy

Italics from The Language of Love and Tea with Roasted Almonds by Yehuda Amichai

You don’t like smoking in other cities. You take pleasure in buying Friday morning figs from the same spot your tongue first met the lips of someone you would later love, your bodies pressed against graffiti on the shuttered market door in the night. You forgot the names of boys too religious to kiss you in the alleys that smell like fish on ice. The main roads are arteries of an old Eastern heart and the Shabbat crowd sweeps you in like a transfusion. Counting almonds in a bag, you bump into the woman who taught you, seven-thousand miles ago, the word shaked. In che tarzeh harf zadaneh? How could you speak this way?

two tastes / that didn't know each other and became one in our mouth. / And over the cafe door, next to the sky, it said: / "Not Responsible for Items Forgotten or Lost."

Olive pits in your fist, these memories, plucked from someone else’s tree. An uncle's house with samovar whistling in the kitchen. The clock hands of youth turning so you felt new on each arrival. Shuttered walls that fell open as they raised you. New families moved into your uncle’s house. Their children will kiss in alleys. Tell me again this is not my exile, tell me again I was raised only where I was born.

But where exactly? As in a children's game: / cold, colder, getting warm, warmer, hot, right there. / What shall we do with that old story now, in our own day? / One generation handed it down to the next in the synagogue reading

You can swallow words like “generational trauma” and grow olive trees in your stomach. Dream deferred, memories displaced, fig dried in the sun. Diaspora grew legs, crossed borders with forged papers. The city handed you a suitcase from Tehran with your last name on it and unpacking will take many lifetimes. Anyone can make memories seem like a wet portrait. Drag your finger through my poem, I dare you.

lovers leave fingerprints on each other / plenty of physical evidence, words without end, testimonies, a wrinkled / pair of pants, a newspaper with the exact date, and two watches

The olives are making marks in your palm, chewed dry. You tried to bury them and they called it planting. Where will you put them down? Where can you? Where?

hands severed, hair ripped out, a gash where the mouth used to be / and demanded

what was theirs, theirs, theirs

Published February 28, 2020.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Letter from the Editors

By Sophie Levy and Evan Mateen

This week marks one year since ZAMAN’s launch in February 2019. In that time, we have published forty articles, essays, poems, paintings, drawings, photographs, videos and other projects that have given a contemporary voice to Mizrahi stories. We have made friends in the most unexpected places and have planted the seeds for a community of contributors, readers, and collaborators that reaches far beyond our hometown of Los Angeles.

From the first few weeks of publication, we were surprised by the strong response we received in support of this project; to see that so many other people, who came from such distinct communities, also shared our yearning for a platform dedicated to Mizrahi culture and affairs only made us more excited to make ZAMAN an ongoing initiative. This has been a year of thinking hard about the places we come from and the places we haven’t gotten to see. It has been a year of commemorating our families’ stories and valuing the histories that brought us where we are today. It has been a year of questions asked and boundaries pushed, controversies addressed and beauties appreciated.

When we first conceived of ZAMAN, our goal wasn’t to simply create an archive of Mizrahi history and leave it at that. It’s common for cultural work to deal with the past as a static entity, emphasizing preservation more than re-engagement or re-evaluation. For us, the past is something that is constantly in dialogue with the future, informing and shaping it, regardless of how aware we are of that fact. ZAMAN was and is about bringing this dialogue to the fore, making it accessible to people who may not have been familiar with it in a Mizrahi context in the first place, and all the while sustaining a commitment to relevant, excellent creative work along the way. The work of our contributors has made this vision a more gratifying and beautiful reality than we could have imagined.

There are a lot of people we’d like to thank for their tremendous support and contributions to ZAMAN over the course of the past year. Thank you Lauren Neman for serving as our Communications Manager and helping our presence flourish on and offline. Thank you to our recurring contributors and good friends, Kyle Newman, Jamie Aftalion, Kayla Cohen, Gabi Kamran, Gabie Yacobi, Jane Paknia, and Mirushe Zylali for staying committed to ZAMAN even as full-time students. Thank you to all of our one-time contributors for giving us the honor of publishing your work and giving us glimpses into new media and communities other than our own. We are deeply grateful to Chaya Community, Protocols, the JFREJ Mizrahi Caucus, New Voices, Gharib Magazine, and the Current for involving us in collaborations and cross-publishings that have helped our content reach new audiences. Special thanks to Tom Haviv and Ruben Shimonov for being some of our biggest advocates in New York, and to our families and friends in Los Angeles for rallying behind us in constant, unconditional support.

Lastly, we’d like to thank our readers. Whether you’ve browsed our site once or twice, have sent it around to your relatives, or have told us what our content means to you, we are endlessly grateful for your engagement, and this is all for you. We hope you have gained something from ZAMAN, be it new questions, new answers, a feeling of resonance, a new perspective, or a new understanding of Mizrahi culture and life. We’re looking forward to the year ahead and can’t wait to see how we’ll grow and what we’ll learn.

All the best,

Evan and Sophie

Photo: Evan’s grandmother Minoo (left) and her younger sister, Sophie’s grandmother Homa (right) holding a puppy. Tehran, 1954.

Published February 27, 2020

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sarchal: The Forgotten History of Tehran’s Jewish Ghetto

By Kyle Newman

To reminisce is to remember with pleasure, to recollect past events while indulging in the enjoyment of nostalgic return. It would be too simplistic to say that the Jews of Iran reminisce blissfully about their past in a country with a fraught history of antisemitism, yet too harsh to conclude that the calamities they endured ought to completely overshadow their 2500 years of rich history. Memories of Sarchal, the Jewish ghetto of Tehran, serve as living manifestations of this ambivalent train of thought. A dynamic community that was forced to adapt to the ebb and flow of life under monarchical Shi’a regimes, Sarchal was much more than a physical location that housed Iran’s urban Jews from the dawn of the Safavid dynasty through to the troughs of a new Islamic Republic.

In 1588 CE, the Safavid Shah Abbas I revived the Persian empire after centuries of Mongol and Turkic governance. Fairly benign in policy during the first half of his rule, Shah Abbas I reversed his friendly attitude towards the Jewish population when a convert from the city of Lar impelled a royal edict that would force Jews to wear distinctive badges and headgear. Under this edict, Jews were now formally categorized as najjes (ritually impure) under the empire’s Shi’a theocratic law, and ghettoization would begin with the forced expulsion of Jews from Esfahan who refused to convert to Islam. Those who did convert were forced to practice Judaism secretly until 1661, when an edict would allow them to conditionally return to Judaism through payment of the jizya (a tax levied on religious minorities) and wearing their designated badge.

Conditions worsened for Jews during the Safavid era until one of the last kings of the dynasty, Nadir Shah, came to power in 1736 and abolished Shi’ism as the empire’s official religion. This action enabled Jews in cities like Mashhad, who had previously been subject to forced conversion, to reestablish and regrow their communities. Still, neither prosperity nor persecution were experienced by Jews in a linear fashion: the rise of the Qajar dynasty in 1794 spelled the onset of tightening oppression. The Romanian Jewish traveler and historian J.J. Benjamin wrote about the horrid conditions of Jewish life in Qajar Iran in an account from the mid-19th century:

“They are obliged to live in a separate part of town; for they are considered as unclean creatures… Under the pretext of their being unclean, they are treated with the greatest severity and should they enter a street, inhabited by Mussulmans, they are pelted by the boys and mobs with stones and dirt… For the same reason, they are prohibited to go out when it rains; for it is said the rain would wash dirt off them, which would sully the feet of the Mussulmans.”

Given the Jews’ status as a najjes group, the most straightforward way to limit physical contact between Muslims and Jews was to segregate them geographically. In Iranian cities with high Jewish populations like Esfahan, Kashan, Tehran, and Hamadan, Jews were segregated into designated neighborhoods, sometimes within the main city walls and sometimes outside of them. The internal layout of each mahaleh (ghetto) played an important role in distinguishing Jewish life in Iran from the history of other ethno-religious communities.

One such mahaleh was Sarchal, the Jewish quarter of Tehran. Sarchal was different from other Jewish ghettos in Iran given its location in the nation’s capital city of Tehran, an especially volatile and ever-transforming urban enclave since its founding by Qajar King Agha Mohammad Khan in 1786. Unlike the ghettos of Esfahan and other cities, Sarchal was located within Tehran’s old city walls. It is also unique in its oxymoronic overlap with a network of mosques and its proximity to a center of commerce, Tehran’s grand bazaar. Jews and Muslims in Tehran therefore must have interacted very frequently despite the Qajar regime’s heavy-handed, active efforts to quarantine and suppress Jewish life under their rule.

Sarchal is situated in the southeast corner of old Tehran, contemporarily known as the 12th district. It is directly west of Emamzadeh Yahya, or the birthplace of Imam Yahya, north of Tehran’s grand bazaar, east of Pamenar Bazaar, and south of the Qajar era Masoudieh palace (Map 1). I have also included below a map in Farsi created by Eshaq Shaoul that highlights landmarks, religious structures, and other important sites in the ghetto (Map 2). I have translated his map and included a key identifying the aforementioned sites in English (Map 3).

Map 3 Key:

1. Tamadon School

2. House of Seyed

3. Pamenar Gym (zoorkhaneh)

4. Midwife Zivar’s house

5. Mosque

6. Eshagh Bathhouse

7. Reza Goli Khan Mosque

8. Birthplace of Imam Yahya (Emamzadeh Yahya)

9. Mosque

10. Sepir Hospital

11. Midwife Sabia’s house

12. Mullah Haninah Synagogue

13. Aghajan Bakhshi’s house

14. Chaim Golabgir’s house

15. Ayatollah Behbahani’s house

16. Mosque

17. Ezra Mikhail Synagogue

18. Bookstore

19. Fereshteh Pharmacy

20. Seven Synagogue Alley

21. Eshagh’s second house

22. Sarchal Bathhouse

23. Sarchal Plaza

24. Mosque

25. Morteza Navi Butchershop

26. Hakim Moshiah Bathhouse

27. Hakim Synagogue

28. Torbati Pharmacy

29. Ezra Yaghoub Synagogue

30. Eshagh’s birthhouse

31. Dekhantal house

32. Dardashti’s house

33. Bakery

34. Yogurt Maker

35. Tekiyeh Mosque

36. Zoorkhaneh

Very few of Sarchal’s original structures remain intact today. The “Seven Synagogue Alley,” an alley literally surrounded by seven synagogues behind Sarchal’s main plaza, is now nowhere to be found. All the old Jewish hammams (bathhouses), which were built because Jews and Muslims were not allowed to use the same public baths, are gone, as are the Jewish butcher shops, bakeries, and zoorkhanehah (gymnasiums). The Ezra Yaghoub and Mullah Haninah synagogues are still standing, along with Sapir hospital, Pamenar Mosque (dating to the late Sasanian period), Abol Hassan Mosque, Haj Ali Khan Mosque, and Ayatollah Shah Abadi Mosque.

Street names were also changed following the Islamic Republic regime’s campaign to erase historical and cultural remnants of the Pahlavi era, often replacing them with the names of Shi’a religious and revolutionary martyrs. Cheragh Bargh Street is now Amir Kabir Street, Siroos (Cyrus) Street is now Mostafa Khomeini Street (commemorating Khomeini’s son who died before the 1979 revolution), while Pamenar Bazaar street endured little change and is now Pamenar street (Map 4).

Map 4 Key:

5. Ayatollah Shah Abadi Mosque

8. Birthplace of Imam Yahya (Emamzadeh Yahya)

10. Sepir Hospital

12. Mullah Haninah Synagogue

16. Abol Hassan Mosque

23. Sarchal Plaza

24. Pamenar Mosque

29. Ezra Yaghoub Synagogue

Sarchal originally included every necessity for Iranian Jews to conduct Jewish life in an incredibly small quarter with an area of less than one square mile. On an average day, one could stop by the bakery to pick up bread, visit the yogurt maker or butcher to prepare a meal, exercise at the zoorkhaneh, pray and study at one of nine synagogues, buy medication from either of two local pharmacies, and engage in scholarly life by buying a book from the bookstore. Reminders of a bygone era of Jewish life in the ghetto are echoed in prominent family names like Dardashti, Torbati, Elghanyan, and Hakim that originated in Sarchal, as well as the titles of surviving architectural spaces: “rag seller and tailor” alleyway, “welder’s bazaar,” and “cannonball storage facility.”

Slowly but surely, the massive discrimination of Iranian Jews that kept them ever close to one another in the confines of the mahaleh would reduce to subtlety after Reza Shah Pahlavi came to power in 1925. The official categorization of Jews and other religious minorities as najjes would be abolished, and the political power of the Shi’a clergy greatly weakened, ushering in a new zeitgeist marked by relative religious tolerance, which the Iranian Jewish historian Habib Levy would call “The Golden Age of Iranian Jewry.” Beginning in the 1940s and bleeding into the 1950s, the last remaining Jewish families of the mahalehs of many Iranian cities left their communities of origin for better jobs and assimilation in Northern Tehran. The Jewish communities of Iran-- and with them, Sarchal-- would eventually see their quasi-extinction after the 1979 Revolution, when the vast majority of Jews were compelled or forced to flee their home of 2500 years due to the new wave of institutionalized antisemitism established by the world’s first parliamentary theocracy, The Islamic Republic of Iran.

Whether you read The Proverbs of John Heywood from 1562 or listened to Snoop Dogg’s album “I Wanna Thank Me” from 2019, we are all well aware of the phrase “let bygones be bygones,” but to what degree does this sentiment merit acceptance in the context of Iranian sociopolitical history? As far as Jewish Iranians like me are concerned, forgetting the past can be detrimental to the continuation of our existence. There is a stigma surrounding the word Sarchal; many Persian Jews are reluctant to admit our history of poverty and ghettoization. But anything short of active remembrance would serve as a disrespectful gesture to the rag sellers, fabric dealers, grocers, midwives, homemakers, rabbis, butchers, dairymen, and tailors that made life in ghettoes like Sarchal sustainable and even vibrant, not to mention the Muslim business owners and civilians who continued to associate with Jewish communities despite institutional restrictions that prohibited them from doing so.

Jewish Iranians’ eventual outmigration from the mahalehs was surely a turning point that bolstered their financial success in later years and decades, but our escape from oppression should not negate our responsibility to honor our ancestors who built lives within its confines. In fact, we have much to learn from the Sarchalis who managed to raise families, provide for their community as a whole, and motivate Jewish life in less than one square mile-- with all the odds stacked against them.

References

Bentley, Jerry H, and Herbert F. Ziegler. Traditions & Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011. Print.

Fischel, Walter J. “The Jews of Persia, 1795-1940.” Jewish Social Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 1950, pp. 119–160. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4464868. Accessed 10 Jan. 2020.

Foltz, Richard (2015). Iran in World History. New York: Oxford University Press.

Levy, Habib (1999). Comprehensive History of the Jews of Iran. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers.

Lewis, Bernard. The Jews of Islam: Updated Edition. REV - Revised ed., Princeton University Press, 1984. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wq0nq. Accessed 10 Jan. 2020.

Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious Minorities in Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shaoul, Eshagh. “Sarechal.com.... Come Home to the Place You Came From.” Welcome to Sarechal, Eshagh Shaoul, http://sarechal.com/.

Tsadik, Daniel. “JUDEO-PERSIAN COMMUNITIES v. QAJAR PERIOD (1).” Encyclopædia Iranica, XV/1, pp. 108-112 and XV/2, pp. 113-117, available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/judeo-persian-communities-v-qajar-period. Accessed 10 Jan. 2020.

Vladimir Minorsky. "The Turks, Iran and the Caucasus in the Middle Ages." Variorum Reprints, 1978.

Published on January 10th, 2020.

19 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Farda / فردا

By Kaitlin Banafsheha

I’ve been having a harder time than usual staying present. I never understood the importance of doing so; it seemed like some phrase that yogis threw around when they talked about spirituality, and I never took it seriously. But as I’ve grown older, I’ve realized how much it applies to me. The tensions between and melding of my Iranian heritage and American upbringing have caused me to reflect on what “staying present” could really mean for someone with a hybrid identity. I get lost trying to reconcile how I relate to each facet of who I am — Will I fall off track with one identity? Will I forget about the other? How can I feel at home constantly trying to negotiate a relationship with the past as the future presses on?

As I worked to answer those questions, I thought about times my family members might have asked them, too. I recently asked my grandmother to send me some photos of her most joyous occasions— her wedding, her daughter’s bat mitzvah. The time between the two events was split by the Iranian Revolution, which changed her life forever— not only because of the physical upheavals it caused, but because of the ways it forced her, and my whole family, to reflect on their changing relationship to their culture as immigrants. It taught them that one of the best ways to remain grateful and grounded throughout change and hybridity is to relish the time we spend with our families.

https://embedr.flickr.com/photos/49323538846

flickr

I also took time to reflect on these questions through my work with animated graphics and typographic design. I played around with the word farda فردا — tomorrow in Farsi— and watched as the word moved in a state of simultaneous turmoil and fluidity across the screen. After taking a step back, what I’d created left me thinking, again, about the state of “presence.” I thought about times I might have been experiencing things I’d want to remember just as much as my grandmother wanted to hold onto memories from Iran, and how I’ve been living the better part of my life letting them pass me by.

https://embedr.flickr.com/photos/49323051143

flickr

I decided that as farda approaches in all its uncertainty, I want to live my life and relate to its complexity with firm, unadulterated presence. Farda serves as a reminder to be grateful for what I do have, to find a home in these tensions and meldings of cultural difference, and to stay present as a key to fulfillment and satisfaction.

It’s taken and has continued to take practice to intertwine these two facets of my identity, to find balance these two variables of past and future. That effort has only emphasized the importance of staying present in my eyes— looking around me, appreciating what contradictory variables can coexist in one cultural experience, and staying true to what really matters to me as time moves forward, toward farda.

Kaitlin Banafsheha is a third-year student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison studying consumer behavior and graphic design. She enjoys working in a range of visual media and has some pretty great genre variety going in her music library. She can be reached at [email protected]

0 notes

Photo

Fiction, Poetry, and the Shaping of Mizrahi Cultural Consciousness

By Sophie Levy

This article was originally published in the Fall 2019 issue of The Current, a journal of politics, culture, and Jewish affairs at Columbia University.

“So sometimes people think we are Arabs

and they are Jews?

[My nephew’s] words make flocks of birds fly through my body

ripping my blood vessels in the commotion

and I want to tell him about my Grandmother Sham’a

and Uncle Moussa and Uncle Daoud and Uncle Awad

But at the age of six he already has

Grandmother Ziona

Grandmother Yaffa

lots of uncles

and fear and war

he received as a gift

from the state.”

- Adi Keissar, “Clock Square”

I read Adi Keissar’s poetry for the first time at fifteen years old, when my mother forwarded me a link to Haaretz’s Poem of the Week under the headline “Who’s who? Who’s an Arab, who’s a Jew?”

The poem was a vignette of a conversation between Keissar and her young nephew as they walked beside the clock tower in Jaffa, tracing the aftermath of his distant observation of a man speaking Arabic. With each consecutive line, I felt like an anvil had been dropped on my chest (in the best way possible). Why did a Persian girl from Los Angeles who hadn’t really thought about her Judaism in years feel such a punch in the gut from a poem by a Yemeni woman in Israel? It felt incomplete and a little tacky to exclusively attribute my reaction to our shared Judaism. There was another layer to consider— a quiet but strong common denominator between the way I thought of my family and the way Keissar wrote about hers, even though I grew up hearing Farsi spoken more than Arabic, and I am American, not Israeli.

I only heard the word Mizrahi used to describe people from Middle-Eastern and North African Jewish backgrounds a few weeks before I read “Clock Square.” It made sense to me that there was another word for us out there—for Jewish people who called ourselves Sephardi even though our supposedly Spanish lineage seemed less-than-factual. It felt good to become aware of this new, audibly articulated way of making a distinction I wanted made—not because I resented the Sephardi label, but because I noticed something different about the community from which I came, and those differences were bound to Iran, not Spain. I let the word roll around inside my head and off my tongue. Mizrahi. So that’s what I’m called.

Of course, label-picking in the age of identity politics can sometimes take on a flattening or superficial connotation. It’s understandable that pinning any one label onto a multifaceted self can feel stifling, and there's been no shortage of analysis surrounding the derogatory or Orientalist undertones of Mizrahi’s literal translation to eastern. It’s a subject that often comes up in the company of other young Arab and Persian Jews I know, some of whom also feel distanced from the term’s relatively recent or “artificial” origin in Israel’s political lexicon.

Bearing this nuance in mind, I would still argue that identification with and critical thought surrounding the issue of Mizrahiut can open the doors for a new, constructive, collective self-perception— one that’s rooted in a consciousness of culture, heritage, and history. In her essay “The Invention of the Mizrahim,” Ella Shohat acknowledges how the Mizrahi label can be seen as a construct born from societal formation under Zionism, but also sheds light on its strengths. She notes that Mizrahi identity “celebrates a Jewish past” in Southwest Asia and North Africa, and that in turn, it can imply a “future of revived cohabitation” with other peoples of the region. In the meantime, its inclusion of a diverse range of Jewish communities places value on the cultural dialogue that ensued between them once they encountered each other in Israel (or in Western countries, as in my family’s case).

The story of Mizrahi immigration to Israel is not a smooth one. Between 1948 and 1951, roughly 325,000 Southwestern Asian and North African Jews migrated there, following their departure or expulsion from their countries of origin. Upon their arrival, many were placed in transitory refugee camps (ma’abarot) with poor conditions, later being displaced to remote development towns or vacated Palestinian neighborhoods in Jerusalem—situating them in Israel’s geographic and socioeconomic periphery. Their ensuing civil rights struggle would continue for decades.

Mizrahi refugees at a ma’abara in the early 1950s.

Contemporaneously, an underground Arabic literary network began to take shape, connecting Mizrahim in Jerusalem and the ma’abarot with Palestinian writers who remained in Israel proper after 1948. Fiction writers like Sami Michael and Shimon Ballas got their start publishing short stories in al-Jadid, an Arabic-language, left-aligned journal that served as a vital platform for Mizrahim and Palestinians alike in the early decades of Israeli statehood. The novel soon emerged as a favorite medium of Mizrahi writers (many of whom were Iraqi men), their characters’ psycho-emotional turmoil reflecting the tumult of the political changes in which they were caught. Whether set in Baghdad, Jerusalem, or Haifa, these novels lamented the waning reality of integrated Muslim-Jewish life, criticized the treatment of Mizrahim in Israel, and conveyed wistful longing for Iraq— all in Arabic.

However important this underground fiction movement was, its tangible success in spurring Mizrahi cultural consciousness among a wider public was limited. Contributors to al-Jadid were writing almost exclusively in intellectual circles, hiding themselves from wider readership in ma’abarot or other communities of Arabic-speaking immigrants to Israel. Further, the overwhelming cultural dominance of the Labor Zionist Ashkenazi literary canon and the disenfranchisement of Mizrahim on a material level led to practical obstacles to publishing. Thirdly, although the deliberate decision on the part of these authors to write (sometimes exclusively) in Arabic was a commendable act of resistance against the state’s efforts to stifle the language’s use, this reduced their novels’ wider appeal to a Hebrew-speaking public. Amid the political activism of the Mizrahi Black Panthers and the decline of the Labor Party in the 1970s, Mizrahi novelists were able to publish their work more frequently; yet even then, they mostly remained on the margins of literary life in Israel— dear to a burgeoning community of Mizrahi academics, but largely unknown to a wider audience.

Despite these barriers to recognition, Mizrahi fiction was and is of value. The often explicitly-stated goal of these novelists was to encourage a sustained connection to and appreciation of the worlds they were a part of before their displacement to Israel. By writing in Arabic, they demonstrated acute political and historical consciousness, challenging the state’s prevailing narratives about Mizrahi primitiveness, its effective demonization of Arab language and culture, and its dismissal of any positive bond to diasporic life. Most importantly, in the words of the writer Almog Behar, their work “carried a torch” for Mizrahim of future generations — like Adi Keissar, and like me.

After “Clock Square,” I started reading Keissar’s work almost voraciously, scouring Haaretz and the Forward for translated poems when I couldn’t understand enough of her Hebrew. As a flagrantly opinionated teenager, I got a high from her blunt feminism and indulged in the refreshing matter-of-factness with which she expressed the depth of her emotions. After having left my majority-Mizrahi Jewish day school for the odd funhouse mirror of a secular, preppy, majority-white high school, it felt like a comforting exhale to settle in the sweet, relatable sadness of poems like “Black on Black:”

"My grandmother loved me with a thick accent

spoke to me Yemeni words

I never understood,

and as a child

I remember

how scared I was to stay alone with her

out of fear that I wouldn’t understand the tongue in her mouth [...]

the sounds far, far away

even when she spoke closely.”

I didn’t yet know enough about Israeli history to fully grasp the political subversiveness of Keissar’s poetry, but I did know that her work made me feel seen. I felt estranged from the no-questions-asked Zionism of the Reform, Ashkenazi institutions I belonged to as a child, and I felt detached from my high school’s country-clubby, all-American ethos. Sometimes, as much as it embarrassed me to admit it, I felt the same distance from my large and (lovingly) overbearing Persian family, and even from other Mizrahi kids. Yet the more I looked into Adi Keissar’s work, the more I understood I wasn’t alone in those feelings, and the more I understood there were ways to address them constructively.

The fact that my mother came across “Clock Square” on Haaretz in English translation was not only indicative of Keissar’s increasing success as an individual poet, but of the rising recognition of a poetic movement she had ignited a few years prior. Keissar is the founder of Ars Poetica, a collective whose name is a double-entendre between Horace’s The Art of Poetry and the word ars عرص — a slur reserved for Mizrahi men that essentially translates to pimp in Arabic. Bringing together Mizrahi poets of diverse ages and backgrounds under an all-women roster of leaders, the group has put a new spin on the poetry reading by reinventing it as the hafla (Arabic for party).

Adi Keissar at a poetry reading.

Since Keissar organized a night of rousing performances by spoken-word poets, alternative DJs, and belly dancers at her first hafla in 2013, Ars Poetica’s loud, multifaceted reclamation of Mizrahi cultures has sent shockwaves through Israel and beyond. Keissar, Roy Hasan, and Tehila Hakimi— additional members of the group and renegade poets in their own right— all won the Bernstein Literary Prize within two years of Ars Poetica’s launch. Change is also felt elsewhere. Erez Biton, often seen as a father figure of this poetic movement, faced many of the same obstacles to mainstream success as his fiction-writing contemporaries for decades, until he became the first Mizrahi writer to win the Israeli Prize for Literature in 2015. The next year also presented a huge milestone, when Biton was appointed as chairman of a new governmental committee dedicated to promoting the inclusion of Mizrahi history and literature in school curricula. Since Ars Poetica’s founding, the group’s impact has garnered extensive media attention, with Jewish newspapers and poetry magazines in the US and Britain publishing article after article about the “Mizrahi Revival” cropping up in Israel.

Ars Poetica may well have triggered the strongest shake-up of Liberal Zionist, Ashkenazi hegemony in the context of Israeli literature to date. Of course, as we’ve seen, the written fight for Mizrahi recognition didn’t begin with Keissar, but her collective does much more than function as a simple continuation of the efforts of writers who preceded them. The group’s unprecedented headway is the result of taking that history, learning from it, and building on it in a new direction.

One thing this “new direction” has entailed is a deeper, more intersectional, subversive strain of political consciousness. Written attacks on the structural subordination of Mizrahim now often serve double functions; when Adi Keissar writes in embracement of her body and physical features as a Mizrahi woman, she is also writing to undo the internalization of racialized misogyny. When Roy Hasan bristles against the performative liberalism of centrist Ashkenazi elites, he is also tackling Israel’s class divide as it occurs along ethnic lines. Keissar and Hasan’s ability to synthetically address a broader range of societal issues in their work with relative brevity enables it to speak to a readership wider than that of the novelists before them.

Furthermore, Ars Poetica’s rejection of elitism goes beyond the content of their poems and permeates their approach to language itself— their verses often full of curses and reclaimed slurs, their Hebrew colloquial, their tone raw and piercing. Hasan points to Jay-Z and the Wu-Tang Clan as important influences on his writing, and it only takes feeling the rhythm of repetition and line breaks in his poem “In the Land of Ashkenaz” to feel their impact on his work:

“...I am the armed fucking robbery

The crook with the kippah

In the court of law

I am the graves of holy men

And talismans

I am a pimp

I am clapping hands

And cheap music

Low culture

Low grade

A stubborn root

And a pain in the ass…”

Between the subject matter of its members’ poetry, their use of vernacular language, and their formulation of the hafla as a truly grassroots method for communal ingathering and artistic promotion, Ars Poetica has shown itself to be founded on a sense of radical accessibility. These poets are stripping their medium of the sterile, elite connotation it has borne for many working-class Mizrahim and presented it as a reachable, usable medium for readers, thereby breaking down the barriers that kept Keissar herself from writing poems until she was in her thirties. It’s predictable, of course, that this accessibility has garnered some backlash from prominent Ashkenazim in mainstream literary institutions; critics have branded their poems as too angry, unrefined, or unsophisticated— arguably recalling decades-old biases about Mizrahi primitiveness. I think it’s safe to say that Keissar and Hasan would meet their discomfort with a scoff and a smile.

There’s also something to be said about the rise of poetry as the medium of choice for many of today’s Mizrahi writers. Prose still has its merits, of course; fictional narratives are a way of emotively articulating and preserving a fairly developed sense of what life was like for Mizrahim before 1948. It remains relevant, as demonstrated by the writer Ayelet Tsabari, for instance, in her use of short stories to create strikingly beautiful vignettes of modern Mizrahi life. But poetry, by virtue of its performability and new aura of accessibility, has demonstrated a special potential for change— not only in Ars Poetica’s move closer to the spotlight in Israel, but in its ability to effectively reaffirm the value of Mizrahiut in the eyes of an ordinary reading public.

This new wave of Mizrahi writing is turning heads toward old and new writers alike. A sweet consequence of the poets’ success today has been rising recognition of yesterday’s novelists, and that recognition is happening in contexts much more interesting than just Israeli academia. This past October, Mahmoud Abbas requested the printing of Ishaq Bar-Moshe’s novel Departing Iraq for distribution at a “conference for Arab leaders” in the West Bank, echoing the author’s hopes for cooperation and consistent interaction with Palestinian Arabs. Meanwhile, the media buzz around Ars Poetica has exposed young Mizrahim in the diaspora to the concept of cultural revival, creating real potential for us to process what we’ve been through, scrutinize where we are, and connect to where we come from.

That’s certainly what new Mizrahi poetry has done for me. I should clarify that my close family doesn’t have a history of immigration to Israel, and I will not erroneously claim to understand what it’s like to grow up in a majority-working class, Mizrahi development town. Even so, amid the difficulties of toggling between life in a huge, close-knit Persian family and finding myself lost in Ashkenazi-run, ardently Zionist institutions, I’ve noticed links between the kinds of alienation many Mizrahim feel from our cultures, whether we were raised in Israel or in the Western diaspora.

The experience of occupying any larger, Ashkenormative framework presents its commonalities: being discouraged or prohibited from speaking Farsi or Arabic as if it were a vulgarity, receiving minimal formal education in Jewish history aside from shadowy mentions of the Holocaust or sanitized tales of Israel’s establishment. From another angle, the legacy of our parents’ or grandparents’ exile from Muslim countries presents its own unique implications: a precarious relationship to the languages that came before English or Hebrew because of the political stigmas they bear, the angst or detachment that results from not being able to see your family’s country of origin because of blacklisting or hostile diplomatic relations. All of this feels disorienting, to say the least.

Written endeavors to foster Mizrahi cultural consciousness— whether academic or creative, intellectual or grassroots— have not only sought to combat this disorientation, but to engage with it on a deeper level, to wrestle with it and derive something of substance from that struggle. The Mizrahi writing with the strongest impact and the most meaningful legacy does more than shallowly advocate that we “connect to our roots;” rather, it demands that we unravel feelings of disorientation and displacement by facing our histories in full, envisioning what we want for the future, and giving ourselves a voice to communicate that effectively. This means reckoning with our relationships to Ashkenazi institutions and communities, but also to non-Jewish Middle-Eastern ones. Iraqi novelists sought to reach across the latter divide by writing in Arabic, and progressive Mizrahi writers today do the same in their advocacy for increased solidarity with oppressed populations across the region.

Engaging with Mizrahiut in a modern context also prompts us to reevaluate the idea of the “homeland.” There is discomfort in an awareness of our communities’ intense estrangement from places and worlds that were once inextricable from our existence. But out of this awareness, and out of the complex implications of exile, there is room for a new understanding of what constitutes a “homeland” for Mizrahim. Alphabets and accents, stories and poems, flavors and smells, songs and images become objects of longing often as deep as the desire for physical return to an inaccessible place. I think a lot of us quietly yearn for that feeling of home, even if we don’t always know how to articulate that or put a finger on what it is. I find it most often in the celebration of dialogue between Mizrahim, in recognizing the connections we have to the things we’ve been conditioned to forget, and in the words of writers like Roy Hasan:

“From the ruins of the language of my parents

I shall build a house for my children."

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Protected Religious Minorities under Iran’s Islamic Regime: an analysis of ideology and policy

Anonymous submission

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 was one of the most significant milestones in the modern history of the Middle East. For the first time, a parliamentary system rooted in the promotion of the core tenants of Shi’a Islam was established, making the nation a theocratic republic. The Islamic regime, which remains in power ever since, is completely juxtaposed to the notion of individual freedom that prevails in Western democracies, as it is based on the strong rapport between religious and civil authorities, and intentionally purged from public life the elements that were opposed to its political principles (Amanat 813). In this essay, I would like to highlight the notion that within this system, there is a distinct tendency to prioritize the rights of the people of Shi’a Islamic faith over all other religious minorities. The Islamic regime tends to link the presence of religious minorities to the possibility that foreign powers might use these minorities as vehicles to undermine the Islamic Republic of Iran: Sunni Muslims via Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, and Jews via Israel. Therefore, the system of government that operates in the Islamic Republic of Iran masks its systematic subjugation of religious minorities under the guise of threat to national security.

I will note that this essay focuses in particular on Iran’s “protected” religious minorities, or ahl al-kitab (lit. people of the book). This term refers to Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians, who were granted this status on the grounds of their pre-Islamic origins and supposed reception of divine revelation. Importantly, Shi’a clerics exclude followers of the Baha’i faith from this paradigm. As such, unlike protected minorities, they face more formalized discrimination and frequent imprisonment on the mere basis of faith. Although the issue of Baha’i oppression in Iran certainly merits attention, the ensuing analysis will center on the conditions of ahl al-kitab.

The prevailing intellectual framework behind the Islamic Revolution of 1979 originated in the eagerness to use Islam as a vehicle for the liberation of the people of Iran from their state of oppression. The regime led by the Shah of Iran, generally accepted as a puppet of the United States, maintained a grip on power through violent means. In response, Islamic scholars of the time emphasized the need to employ a more revolutionary approach to the practice of the Muslim faith to combat the Shah’s radical secularism (Dabashi 113). Three prominent scholars, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Morteza Mutahhari, and Ali Shariati, are recognized as the most influential thinkers in laying the ideological framework of the Iranian Revolution. These three figures were not concretely part of a single intellectual movement, nor were their political, philosophical, or spiritual trajectories wholly aligned; regardless, they ultimately coalesced in the minds of Iranian revolutionaries as catalysts of the Revolution. Together, Khomeini, Mutahhari, and Shariati called upon the redemption of Iran from foreign influence and the establishment of a system of government based on the tenets of Shi’a Islam—depicted as the best framework for promoting well-being among Iranians. It should be added that these writings are notably conspiratorial and consistently highlight the moral and intellectual superiority of revolutionary Shi’ism over other religions and strands of Islam (Dabashi 119).

A meeting of the Council of the Islamic Revolution in 1979. The committee was created by Khomeini and chaired by Mutahhari until his assassination.

The intervention of Shi’a clerics in the political debate arose in Iran during the Imperial period. The politicization of Shi’a Islam had the ultimate effect of denouncing the complicity of the Shah in the pillaging of the country’s natural resources and the suffering of the citizenry, and the Shi’a clerics delegitimized the efforts of the Imperial regime to introduce Western democracy and liberalism into Iran. From the beginning, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini singles out the Jews as a social group “who first established anti-Islamic propaganda and engaged in various stratagems.” Khomeini draws upon the Quran in formulating this specific argument, as the Quran frequently depicts the Jews as people who corrupt Muslims, transgress the laws of God, and actively fight Islam (Quran 4:50, 5:13, 5:41, 5:51, 5:59). The Ayatollah observed that “later [the Jews] were joined by other groups, who were in certain respects, more satanic than they. These new groups began their imperialist penetration of the Muslim countries about three hundred years ago” (Khomeini 7).

This doctrine also served to establish a strict demarcation line between Sunni Islam, an ideology that served to perpetuate tyrannical leaders in power (in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States), and Shi’a Islam, an ideology which not only liberates the oppressed people of Iran but also other peoples of the post-colonial Third World (Ahmad 12). The main focus of Khomeini’s writings are the “agents of imperialism,” both in Iran and abroad (Khomeini 17). Khomeini states that these agents of imperialism “are not converting [Muslims] into Jews and Christians; they are corrupting them, making them irreligious and indifferent, which is sufficient for their purpose” (Khomeini 79).

Most importantly, he warns for preparation to fight the Jews and other people he accuses of conspiring to harm Muslim populations. Khomeini states, “if the Muslims had acted in accordance with this command, and after forming a government, made the necessary extensive preparations to be in a state of full readiness for war, a handful of Jews would never have dared to occupy our lands and to burn and destroy the Masjid al-Aqsā” (Khomeini 22). In this context, Khomeini sets the foundation for the future Islamic Republic’s repudiation of Zionism—one of the immutable pillars of the perpetual Revolution (Dabashi 598). Though Khomeini nominally declared protection for ahl al-kitab, this clear conflation of Zionism and Judaism by Khomeini undermines such protection and at the time of the Revolution posed a serious threat to Iranian Jews by legitimizing anti-Semitism as a form of revolutionary progressivism. This is why, almost immediately after the Revolution, leaders of the Iranian Jewish community like Habib Elghanian were labeled Zionist Spies and promptly executed (Haaretz). As a consequence, Chief Rabbi of Iran Hakham Yedidia Shofet was urged by community members to publicly denounce the Shah and announce allegiance to the Revolution, not because he necessarily agreed with it, but in order maintain community security within this rapidly changing political context (Sternfeld, “Iranian Revolution: Unintended Consequences”).

In Mutahhari’s case, it is clear that certain motivations necessitated a level of subjugation and incitement against religious minorities. Mutahhari argues that “not all the People of the Book are the same; some believe in God, Resurrection, and the laws of God. These are the People of the Book whom we are to leave alone. The second category, those of whom we are to fight, is the People of the Book in name only” (Mutahhari 15). The implication of this claim is that it defers power to the jurisprudence of the ulama (clerics) to determine which factions and sub- factions of social groups pose threats, regardless of if they are ahl al-kitab. However, Mutahhari observed that it was not possible to seek the conversion of infidels as a panacea to this problem: “faith and rejection, iman and kufr, must be freely chosen, and cannot be forced onto others. Islam says that whoever wants to believe will believe, and whoever does not want to, will not” (Mutahhari 67). Mutahhari also highlighted that the Iranian people had a prominent role in propagating the most just, and consequently superior, interpretation of Islam: “the Iranians observed that the only group of Muslims that was free of prejudice and very keen to establish justice and equality in society and showed an unlimited sensitivity in regard to these values was [the Shi’a Muslims of] the Household of the Prophet” (Mutaharri, “Islam and Iran” 54-55). Mutahhari’s writings illustrate the need to remain vigilant about the potential ramifications of adopting religious principles based on national or racial allegiance. This also incorporates a clear warning against following the teachings of the strand of Islam espoused by people of Arab descent, explicitly distinguishing the moral superiority of Shi’a Islam over Sunni Islam (Mutaharri, “Islam and Iran” 58).

While Mutahhari highlighted the difference between a Persian and Arab pursuit of Islam, Ali Shariati’s writings were key in noting ways in which Shi’a and Sunni Islam espoused different forms of governance. At first, Shariati criticized Western democracy, which he considered to be an ideological tool that effectively oppressed people in positions of disadvantage, such as the poor (Shariati, “Reflections of Humanity”). Shariati advocated for a political system based on liberty and equality, albeit informed by the spiritual perspective that characterized pre-modern societies. The main problem that can be identified in this political approach is that the status of minorities is significantly diminished. Shariati’s arguments emphasize the need to keep “alive the hope of redemption after martyrdom,” promoting the advent of “revenge and revolt” against the tyrannical leaders that did not work for the benefit of the people (Shariati, “Red Shi’ism vs Black Shi’ism”).

A 1980 postage stamp honoring the memory of Ali Shariati.

Shariati highlighted the need to preserve the “faith in the ultimate downfall of tyrants and the decrees of destiny against the ruling powers who dispense justice by the sword��� (Shariati, “Red Shi’ism vs Black Shi’ism”). Shariati’s writings set the tone for the strict distinction between Sunni and Shi’a Islam that would inform the system of government that prevails in Iran, alluding to Sunni Islam’s tendency to espouse tyrannic dictators (indicating Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States), and emphasizing the moral superiority of Shi’a Islam in its usefulness for advancing the idea of the unity of mankind and God.

The tenets of Shi’a Islam additionally influenced the nationalist philosophy espoused by the Islamic regime since 1979. Ali Shariati emphasized the putative dangers involved in assimilating the cultural perspective of other people, noting that the person who adopts other religious and cultural models “forgets his own background, national character and culture or, if he remembers them at all, recalls them with contempt.” One of the main implications of this way of thinking is the reduction of the scope of pluralism within the Islamic system of government established in Iran in 1979 (Shariati, “Reflections of Humanity”).

The system of government that has operated in Iran since 1979 is centered around the principle that all the political parties that participate in the legislative process need to abide by the tenets of the Islamic Revolution—this allows for a great deal of political debate regarding the best way to safeguard the interests of the country. As discussed prior, the Iranian Constitution nominally guarantees the basic freedoms of the ahl al-kitab religious minorities living in the country. Article 13 states: “Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian Iranians are the only recognized religious minorities, who, within the limits of the law, are free to perform their religious rites and ceremonies, and to act according to their own canon in matters of personal affairs and religious education.” Furthermore, Article 14 specifies that “the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran and all Muslims are duty-bound to treat non- Muslims in conformity with ethical norms and the principles of Islamic justice and equity, and to respect their human rights.” Article 64 guarantees some minority representation in government, stating that “Zoroastrians and [Assyrian, Chaldean and Armenian] Christians and Jews will each elect one representative” to the Islamic Consultative Assembly.

The inauguration of the 10th Islamic Consultative Assembly-- Iran’s current parliament-- at the Majles headquarters in 2016.

Notwithstanding the existence of these constitutional guarantees, religious minorities face several constraints that effectively hinder their participation in Iran’s political system beyond their symbolic inclusion in the Majles. Non-Muslims are prohibited from occupying more than their one guaranteed parliamentary seat, which is arbitrary given the major differences in population size between different protected religious minorities. Members of these communities are also disqualified from holding any higher office. The system of government that prevails in Iran has established the primacy of Shi’a Islam as the main form of political organization; therefore, all candidates in the public sector are thoroughly vetted in order to determine whether they will use their public post to fulfill the Islam Republic’s mission “for ensuring the continuation of the revolution at home and abroad” (Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran). It would be impossible to suggest that any member of a religious minority who intends to run for office could ever fulfill the duties required for continuing the revolution in it’s entirety, as this would necessitate the individual’s own conversion to Islam. This can be highlighted in the Quranic verse 21:92, ”This, your community, is a single community, and I am your Lord, so worship Me,” which is referenced in the Preamble of Iranian Constitution, substantiating the Revolution’s attempt to establish a single [Shi’i] world community—more clearly, directly writing this Quranic verse in the Constitution reveals that the ultimate goal of the Revolution is to establish a single Shi’i world (Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran). By this logic, electing any non-Shi’i would be paradoxical and negate this ambition.

There are significant obstacles that prevent religious minorities from enjoying full citizenship rights, in spite of the fact that religious minorities have political representation in the Islamic Consultative Assembly (Majles). For instance, access to a university education requires extensive knowledge of the principles of Shi’a Islam, which means that the members of religious minorities are put at a disadvantage or pressured to study overseas. There is also a penalty of death for any Shi’a Muslims who abandon their faith (whereas other faiths are actively encouraged to do so and adopt Shi’ism), and intermarriage is effectively forbidden unless the non-Shi’a partner converts. These are all issues that attest to the fact that freedom of religion in Iran is nominal and limited, at least in the way that it is conceived of in the Western world.

Iranian Jews were especially affected by the ideological undercurrent of the Islamic Revolution, namely because the Jewish population is perpetually threatened by allegations of their potential associations with Zionism. As previously mentioned, a number of Iranian Jews have been executed since the onset of the Islamic Revolution after being accused of spying for the State of Israel. Nevertheless, it is important to note that up until 1979, there was a great deal of support among Iranian Jews for the democratization of the country (Sternfeld 857-858). Before the advent of the Islamic Revolution, many Iranian Jews were involved in intellectual circles that promoted the liberalization of the country and the introduction of the democratic system of government. During the Imperial period, the Jewish population of Iran found opportunities for economic progression and social advancement, which led to their increased support for activities of Muslim clerics and leaders involved in revolutionary activities. Furthermore, during the period of revolutionary upheaval, the Jewish Sapir Hospital provided medical attention to the revolutionary protesters who had been injured by the police (Sternfeld 869).

Forty years after the Revolution, the relationship between Iranian Jews and the Islamic Republic remains tenuous, to say the least; the regime still peddles a strong degree of suspicion regarding the loyalty of the Jewish community to the Islamic regime, and continues to maintain a largely conspiratorial perspective on Israel’s actions and the occurrence of the Holocaust (Gerech and Takeyh). This is one factor of many that has led to the migration of most of the Jewish population to Israel, the US, and other countries since 1979. Those that have remained in Iran are generally quiet when it comes to politics, and hesitate to publicly criticize the status quo- although the head of Tehran’s Jewish community once criticized then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in the wake of his repeated denials of the Holocaust (Cohler-Esses). Jews in Iran today operate their own small institutions and practice their religion freely, reporting that they live comfortable lives and feel secure. However, it is difficult to gauge the accuracy of such claims, given fears of possible repercussions from the current Iranian regime, which strictly polices the content of interviews with foreign media outlets.

A man observes the decorations at Yusef Abad Synagogue in northern Tehran.

Overall, the official position of the religious minorities falls in line with the tenets espoused by the intellectuals of the Islamic Revolution during the erosion of the Imperial period. The religious minorities that receive official protection are considered to be the recipients of the divine message handed down by God to his prophets. Mentions of religious minorities in official documents are largely meant to paint a sanitized image of an Islamic regime which has successfully incorporated all its citizens, regardless of religion. The relationship between the Islamic regime and its religious minorities is guided by a strict ontological demarcation, which is meant to affirm the moral and intellectual superiority of Shi’a Islam over all other religions, in spite of some attempts to incorporate other philosophical and intellectual perspectives into Iranian political life (Abrahamian 188).

In conclusion, the system of government established in the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979 is based on the exclusion of the religious minorities from political life. And while the Islamic Republic of Iran nominally protects the rights of religious minorities, it also imposes significant restrictions on their mobility within Iranian society, particularly when it comes to their participation in the various echelons of governance and their ability to criticize the status quo. The Islamic Revolution emphasizes the rights of the community over the rights of the individual, in clear contrast from the tenets of Western democracy. This ultimately entails the firm prioritization and privileging of the Shi’a majority by appealing to religious, nationalist and populist themes (Abrahamian 143). Moreover, the intellectual framework set out by scholars such as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Morteza Mutahhari and Ali Shariati paved the way for the implementation of a guiding “Twelver Islam” redemptionist philosophy in government, necessitating the subjugation of minorities to create an environment guided by jurisprudence in anticipation of the Mahdi. Therefore, in spite of a rhetoric based on freedom and equality, the Islamic Republic of Iran tends to connect the presence of religious minorities to heresy, corruption of Islam, rebellion against the regime, and inhibition of the ever-continuous Revolution.

The anonymous author is a Persian Jewish student from Los Angeles.

Works Cited

Abrahamian, Ervand. A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Ahmad, Jal-al Al. Occidentosis: a Plague from the West. Tehran: Islam International Publications, 1984.

Amanat, Abbas. Iran: A Modern History. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017. Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran (1979) – Retrieved from www.servat.unibe.ch/icl/ir00000_.html on November 4, 2019.

Cohler-Esses, Larry. “What PBS got right-- and so wrong-- about the Jews of Iran.” The Jewish Telegraphic Agency, December 4, 2018. https://www.jta.org/2018/12/04/culture/pbs-got-right-wrong-jews-iran

Dabashi, Hamid. Theology of Discontent: The Ideological Foundation of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. London: Transaction Publishers, 2005.

Gerecht, Reuel Marc, and Ray Takeyh. “Iran's Holocaust Denial Is Part of a Malevolent Strategy.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 27 May 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/irans-holocaust-denial-is-part-of-a-malevolent- strategy/2016/05/27/312cbc48-2374-11e6-aa84-42391ba52c91_story.html.

Haaretz. “Builder of Wrecked Tehran Tower: Iranian Jewish Businessman Executed in '79 as 'Zionist Spy'.” Haaretz.com, 15 Jan. 2018, www.haaretz.com/middle-east- news/builder-of-wrecked-tehran-tower-iranian-jewish-businessman-executed-as- zionist-spy-1.5487806.

Khomeini, Ruhollah. Islamic Government-Governance of the Jurist. London: Alhoda Press, 2017.

McHugo, John. A Concise History of Sunnis and Shi'is. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2018.

Mutahhari, Morteza. Jihad The Holy War of Islam and Its Legitimacy in the Quran, Teheran: Islamic Propagation Organization, 1988. https://www.al-islam.org

Mutahhari. Morteza. Islam and Iran: A Historical Study of Mutual Services, Teheran: Islamic Propagation Organization, 1986. https://www.al-islam.org

Shariati, Ali. Reflections of Humanity. http://www.iranchamber.com/personalities/ ashariati/works/reflections_of_humanity.php

Shariati, Ali. Red Shi'ism (the religion of martyrdom) vs. Black Shi'ism (the religion of mourning). http://www.iranchamber.com/personalities/ashariati/works/ red_black_shiism.php

Sternfeld, Lior. The Revolution's Forgotten Sons and Daughters: The Jewish Community in Tehran during the 1979 Revolution. Iranian Studies, Vol 47, no. 6, 2014. 857-869.

Sternfled, Lior. “Iranian Revolution: Unintended Consequences.” Tablet Magazine, 15 Jan. 2019, www.tabletmag.com/jewish-news-and-politics/278343/unintended- consequences.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Hamdam / همدم

By Michelle Shofet

Hamdam, meaning “of the same breath.” The triptych of screenprints pays tribute to a deep sisterhood. Two figures stand side by side in black gowns, twin expressions on their faces. Their overlapping hands are linked and joined as if belonging to only one person. Likewise, the figures’ heads and bodies merge as one, reflecting the depth of their bond. In the center panel, a rose makes reference to the Persian funerary rites of dousing graves in rosewater.

Michelle Shofet is co-founder of Nocturnal Medicine--an art and design studio that creates experiences, spaces & media for working through the social & emotional challenges of radical environmental change. Her research interests include themes of abject landscapes, cultural memory and identity politics. She earned her Masters in Landscape Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and approaches her research through the lens of the built environment. Michelle is based in New York City.

Published October 18th, 2019.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two Summer Poems

By Kayla Cohen

Illustration by Sophie Levy

On the bus in the north of Israel

On the bus in the north of Israel, you and I are given

a small green bag of plums.

There is no need to guess which are sweet, you tell me.

The bugs have already discovered which are sweetest.

Your hand then slips into the bag.

You choose the plum with the most bug bites.

We proceed to enjoy what is small and warm,

What is spotted and sweet

What is ripe and spoiled;

What is and was, what was and is no longer.

Eclipsed Prayer

I once witnessed a solar eclipse in Jerusalem.

I rotated around the blue building

while you washed your feet at its side.

The golden dome stood in front of me,

and the white moon waned behind.

For a moment, the gold shine, moon,

and I briefly aligned.

You washed to enter the mosque.

To enter silence; a brief reprieve,

and so close to heaven.

“Tell me what you see,” I said. “I’ll wait here.”

Last week you had also washed your feet,

but to leave a place less quiet.

In Tel Aviv,

at the end of the beach,

kneeling under one of the shower spouts

arranged in a line of three were

you and two Moroccan Jews

submitted to the sun,

your heads down,

your sun-singed feet clean before God.

Around and around:

A flush of blood,

A sun so bright.

An eclipse of prayer,

A block of light.

The sphere where

the dome and moon and I aligned;

the sphere with

the sand and sea and spouts in line.

Tell me, have we reached eternity?

Tell me, have we eclipsed eternity?

I’ll wait here.

Published October 4th, 2019.

0 notes

Photo

Chloé Pourmorady on "finding meaning” in her heritage as a Persian Jewish musician

By Joshua Taban & ZAMAN Editors

Chloé Poumorady’s music is a symphonic blend of traditional Persian and Sephardic Jewish harmonies, tinged with the lightness of folk melodies from across the globe. Now leading a six-musician ensemble, the classically-trained violinist and vocalist counts Medieval Ladino poetry, the Book of Genesis, and Béla Bartok among her influences, tapping into a diverse array of musical traditions to compose original work.

Pourmorady’s debut album, Begin Majesty, opens with the first few words of the Torah and culminates in a Requiem that acts as a cry for awakening and peace. Her ability to eloquently combine age-old and current approaches to musical composition won the record the title of Best Album at the 2019 Global Music Awards. The musician was also featured in the Jewish Journal’s 30 Under 30 series in 2017 and is continually involved in arts initiatives established by Jewish organizations in Los Angeles.

ZAMAN contributor Joshua Taban met with her in July to discuss her background, process, and goals as a musician.

As a college student, Pourmorady developed an interest in ethnomusicology, beginning her study of the commonalities and disparities between traditional music in Iberia, Eastern Europe, and southwestern Asia. In retrospect, she sees this period of learning as vital to her current practice, “because without it, I would have never appreciated or understood my own culture’s music in the way that I do,” she said.

For Pourmorady, composition is a process that not only demands an understanding of what she resonates with as an individual - but what sounds have the potential to connect with people’s emotions on a more universal scale. She believes that drawing upon a wider breadth of musical traditions creates greater potential for her songs to compel listeners, irrespective of differences in personal background. “When I am in front of an audience, I see [music] as a contribution to them,” Pourmorady explained. “I realized I have to be ‘generous’ as a composer; You may connect to the sound of the tar (an Iranian string instrument), while someone else might connect to the percussion.” She views her culturally pluralistic approach to composition as a means of achieving this end.

The Chloé Pourmorady Ensemble’s sound has a recognizable air of fluidity to it; one that the vocalist herself likened to “the swaying of olive tree branches.” She attributes this melodic sense of “flow” specifically to the culture of Persian Jews, on the grounds of their historic exposure to mystical Sufi poetry and the relative absence of religious boundaries (i.e. formal Jewish denominations) within communities in Iran. This understanding of Persian Jewish culture percolates into her process as a composer, resulting in performances rich with sweeping instrumentals, swaying rhythms, and lyrical melodies.

Ultimately, Pourmorady’s commitment to deepening her understanding of Persian and Sephardic music stems from her outlook on life from a uniquely Jewish perspective. “I see being a Jew as a celebration, as being a lover of life,” she said, describing Judaism itself as “a melodic tradition.”

“Within my community, I hope to reinvigorate that tradition so that people can find meaning in the beautiful and rich culture we come from.”

Joshua Taban is a senior at the University of Southern California double majoring in Business Finance and Real Estate Development with a minor in Italian. He also takes interest in twentieth century Iranian history and has a fondness for learning about architecture.

Chloé Pourmorady is the lead vocalist and violinist of the Chloé Pourmorady Ensemble, based in Los Angeles. She graduated from Loyola Marymount University with a bachelor’s degree in Music Studies.

Published August 30, 2019

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Self-Portrait

By Phillip Neman

This oil painting by Phillip Neman explores how the cultural dichotomy between his life as a first-generation American and his distant, almost mythicized conception of his family’s homeland of Iran blurs his self-image. Set against the backdrop of his college dorm room, the painting examines the gaps that exist between how he perceives himself and how others perceive him, illuminating how one’s heritage can simultaneously serve as a catalyst for self-understanding and external misinterpretation.

Neman’s work in painting and in mixed media often centers around the issue of being born into a culture associated with an unfamiliar physical place. Ironically, his face is not visible in his portrait and is instead replaced by fragments of a geographic map of Iran. This serves to question how others see him – as someone reduced to their ethnicity – simply because the audience is prevented from making a more nuanced connection to the figure’s facial expression or demeanor. However, by essentially making Iran’s topography synonymous with his own skin, Neman also nods toward the quiet yet ineludible, enduring connection that his lineage establishes between body and homeland.

As a California native whose Jewish family is effectively barred from returning to Iran safely, Neman grew up embracing and celebrating the new place that his parents chose to call home. The objects surrounding his figure are representative of the process of adolescent identity-building, touching on how one’s sense of self can stem from much else than heritage. By treating intimate home objects and souvenirs with the same care as the body and Iran’s map, Neman’s self-portrait serves to mend the internal struggle of being caught in the crosshairs of modern, youthful Mizrahi-American identity.

Phillip Neman is a junior at the University of California, Santa Barbara studying Chemistry and Visual Art. In his free time, he enjoys reading, playing tennis, and painting. Click here to reach him.

Published August 25th, 2019

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Nationalist Mythologies and the False Friendship of Nostalgia

By Mirushe Zylali

Additional Writing by Sophie Levy

What is a mythology?

Through mythology, one locates oneself within history and creates a sense of continuity between the past, present, and future.

The impulse to place oneself in a historical continuum is understandable, especially within postcolonial contexts. For Europeans, myths provide a basis of identity for the nation-state. For Euro-colonized peoples, a desire to return to a pre-colonial body politic often becomes integral to liberation movements, and later, becomes a method of garnering mass popular support for a burgeoning post-imperialist nation-state. Postcolonial mythologies are often manifestations of an emotionally-tinged hunger for a life that does not ache of colonialism.

Mythology has a vital role in legitimizing the construction of modern ethnonationalist states and their respective languages, cultures, and propaganda systems. When “British India” was cleaved in two, Pakistan adopted an alphabetic script based on Arabic, while India adopted a script based on Sanskrit, though similarities abound between spoken dialects in the subcontinent’s northern regions. To this day, India’s far-right Hindu nationalists are working to incorporate more words derived from Vedic Sanskrit into modern Hindi, while nationalist Pakistanis do the same with Islamic terminology derived from Arabic.

In his construction of the Albanian nation-state, Enver Hoxha outlawed religion and claimed that modern Albanians descended from ancient Illyrian tribes. Modern Turks assert that they are heirs to the Ottoman Empire established by Byzantine tribes over 700 years ago. During WWII, German Nazis even claimed to be descended from Aryans, somehow also insisting upon their origins in the lost city of Atlantis, and repurposed the swastika, a Hindu symbol, to this aim. Later in the twentieth century, Iranian nationalist groups would adopt a link to this “superior” Aryan race in order to incite violence against ethnic minorities within Iran, such as Jews and Kurds. Saddam Hussein insisted upon modern Iraqis’ link to the people and culture of ancient Babylonia in building his autocratic government - just as the Pahlavi Shahs of Iran belabored their connection to Darius’ pre-Islamic empire.

Evidently, it has been a nation-building tactic of autocratic regimes across Europe and Asia to emphasize links between a current population and an ancient culture or mythology. Here, I take time to deconstruct why this method is somewhat futile.

Iraqis, for instance, cannot claim direct historical continuity with Babylonia because its religion-and the way of life it spurred- has not been maintained since the fall of Babylon in 539. Since then, cultural diffusion, conquest, and the shifting borders of empires have made Iraq a thoroughly Arab nation-state, notwithstanding the presence of non-Arab ethnic minorities.

Victors often write what history survives. What records exist of the processes of the Persian and Arab conquerors who altered the culture of ancient Mesopotamia? One could infer that those attempting to keep up the ‘old ways’ would have been brutalized or disenfranchised by their new conquerors. Neither the ethnic composition nor the historical legacy of ancient life in present-day Iraq is continuous with those who live there today, and the recovery of such a culture would be nearly impossible. But why would anyone want to undertake such a task in the first place?

the Eagle of Saladin - often used as a symbol of Ba’athist ideology.