#time is a construct of human perception

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I'm not doing very well at the moment but I was slightly happier a few seconds ago, before someone pointed out that Faerieland has been on the ground longer than it was in the sky :')

#neopets#faerieland#FLASH WILL LIVE ON FOREVER IN MY HEART#time is a construct of human perception#as tom so lovingly points out

221 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’d like to think Morning is whatever time I wake up , whether that is 1 pm , 8 am , 2 am , morning is whatever we as a society dictate ( I constitute as my own society )

No I don’t not know what I’m saying

Ya thats fair, time is whatever i say it is, unless I have somewhere important to be at ^^

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think I've finally reached mom fandom unc status because what do you MEAN I've been here for almost 10 years???

1 note

·

View note

Text

EXPLICIT CONTENT | MINORS DNI

Art the Clown x Reader SMUT • headcanons, how Art fucks, what he gets off to, etc

big content warning! contains some stuff that may gross you out; read at your own risk: menstruation kink, piss kink, oral sex, anal sex, object insertion, blood kink, various weapons mentioned, bondage, human hair and bones, butts and what comes out of butts, public sex, cockwarming, mostly dom!Art and sub!reader

🔪 Remember the work desk with all of Art’s weapons and tools on it? He knows you want him to fuck you, but he’s got shit to do (meaning weapons to build) so he lets you sit under the desk, cockwarming him while he works. You’re on the ground between his knees, patiently holding him in your mouth. When he finishes constructing his latest instrument of torture/slaughter, Art pats his palm against his thigh, wordlessly telling you to climb up into his lap and ride him.🩸

🔪 Art enjoys blood and guts, so it goes without saying that during your period, he’s particularly eager to fuck you. He can detect the slight change in your scent, usually aware you’ve begun to bleed even before you know. He plays with your pussy like it’s a new, special toy when you’re bleeding, spreading your lips and tracing his name on your inner thighs in red. Seeing/touching/tasting blood that comes from you is special to Art. It’s the only time he gets to play in blood without it being the result of him hurting someone, so that makes the experience unique for him. He saves your used pads for ‘alone time,’ using them later as a ‘sleeve,’ to masturbate with.🩸

🔪 Art sometimes fucks you with unconventional objects, like the handle of one of his weapons (knife, axe) or the neck of a bottle. If you’ve displeased him but he still wants to fuck you, he might deny you his cock and instead use something else, like the handle of one of his knives or the barrel of an (empty!) gun, to make you come instead of his cock, as a degrading ‘punishment.’🩸

🔪 Art loves bondage. He knows what he’s doing when it comes to tying knots, as evidenced by the multiple victims you’ve watched him restrain. He enjoys the power dynamic of being in absolute control of another person. When that crosses over into sex, you both get off on him tying you up and doing whatever the fuck he wants with your body.🩸

🔪 Art’s methods can border on sadistic at times (I mean how could they not??) but because he wants to keep you around to play with for the long haul, he never pushes you beyond the limits of safety, no matter how many new ways he comes up with to plug every hole in your body. If we know anything about Art, it’s that he’s perceptive. He studies the way your body responds to different forms of stimulation and mentally catalogs the information for later. All of his skill in crafting tools of torture means he’s able to create customized ‘toys,’ to fuck you with. But the thing is, they’re never normal, or sweet; they always contain something fucked-up and sick. Art once surprised you with a whip he’d put together for you. Its strands were soft and felt so good gliding over your clit. You came so hard when Art whipped your pussy till it was puffy and leaking. It would have been a wonderful gift, if you hadn’t realized later, upon closer inspection, that the strands now wet with your cum were in fact strands of human hair. And the custom dildo Art made for you, the one that was so smooth and colored beige/white? You later found out Art had chiseled and smoothed down a human bone to make it for you. The information almost made you sick on the spot. Art found your horrified reaction hilarious, of course, and it didn’t stop him from laying you down and fucking you with it all the same…🩸

🔪 ANAL ANAL ANAL ANAL ANAL ANAL …

He loves to fuck you in the ass. Art’s a nasty little motherfucker when it comes to the stuff that comes out of butts, and I’m not gonna elaborate here, but you can use your imagination to follow where I’m going with this…🩸

🔪 Art has zero inhibitions: he kills anyone, anywhere. Imagine that relating to sex; of course he’s going to fuck you wherever he wants, including places where you might get caught. Sex in public/risky spaces feels natural to Art, because he literally does not give a single fuck. Remember the first time you ever saw him? When you stumbled out the back door of that sleazy little bar in your home town, so drunk off your ass you thought you were leaving through the front? Art was in the alleyway behind the bar, black garbage bag hoisted over his shoulder, not even looking for anyone to fuck up but when he saw you, he knew he’d found a victim for the night. He’d planned to stalk you home and do unspeakable things to you-but as you took the lead and approached him, there in the alleyway, he was caught off guard, his whole plan upended the moment you slid your arms around his waist, stood up on your tiptoes, and placed a soft, sloppy kiss on his cheek. He was awestruck, and even if he could speak, Art would still have been at a loss for words. You walked him backward a few steps, lining him up against a dumpster in the alleyway. You began fondling him through his costume, grinning when you realized his body had already begun to respond. One thing led to another, and within minutes, Art had you bent over that dumpster, with a fresh hole torn in the front of his costume where your bodies were joined…🩸

🔪 No one would associate The Miles County Clown with tenderness, but if they knew Art, they would see a softer side of him only you do. He’s still fucking deranged, don’t get me wrong. But Art also has moments of vulnerability, when there’s nothing he wants more than to hold you. Sitting in Art’s lap, he wraps his arms around you and stays still, so still, just enjoying the soft thump of your heartbeat against his, and the low hum of your breath on his chest. Your nearness calms the monster inside Art so well that sometimes, he forgets he is the monster itself…🩸

🔪 Another benefit of having you in his lap? Art realized he could use his strength to make you stay in his lap no matter how badly you had to get up and take a piss, forcing you to wet yourself all over him. You felt him gradually getting hard under you as you began to wriggle on his lap. Art could see your discomfort, and when you told him you needed to get up and take a piss, he refused to release you. You’d expect him to be smiling at you at a time like this, silently mocking you; but the look in his eyes was deathly serious, pitch black and full of a demented lust that would have had you locked you in place even if his arms hadn’t. Blushing into his shoulder, you accepted the fact that Art wasn’t letting go of you any time soon, and that he really was into this. He wanted this to happen. You allowed your bladder to empty, a soft trickle saturating your panties, followed by a steady stream of hot piss that spread over Art’s lap. His clothes were soaked through below the waist, your piss running down between his thighs and dampening the couch cushion beneath you. Art was rock hard by this point, his wet cock throbbing against your pussy. He lifted you off his lap just enough to reach between your bodies and position his tip against your entrance, then used your piss as a lube to slide inside you…🩸

#art the clown#art the clown x you#art the clown headcanons#art the clown x reader#art the clown smut#art the clown x y/n#art terrifier#terrifier#terrifier 2#terrifier x reader#terrifier 3#terrifier smut#terrifier x you#terrifier x y/n#david howard thornton#damien leone#slashers x you#slashers x reader#slashers#slashers x y/n#horror#movies#slasher smut#slasher x reader#slasher x you#slasher x y/n#terrifier fanfic#terrifier fan fiction#art the clown fic#horror smut

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐓𝐢𝐦𝐞 𝐈𝐬 𝐍𝐨𝐭 𝐋𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐚𝐫: 𝐄𝐦𝐛𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐄𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐍𝐨𝐰

The idea that time is not linear comes from the understanding that it is merely a perception created by the human mind to organize experiences. In reality, everything that exists, has existed, or will exist is already present in the “eternal now.” This means that while we are accustomed to thinking of time as a straight line with past, present, and future, this is merely a mental convention to make it easier for us to understand.

How does this connect to manifestation?

If everything already exists, including your fulfilled desire, you do not need to “wait” for something to happen or “do something” in the present to achieve it in the future. Instead, you can simply align your consciousness and your internal state with the reality where your desire is already true. This alignment puts you in the position to experience that version of your life because, in the infinite field of possibilities, it is already there.

The practice of the “eternal now”:

1. Accept that the future already exists: Stop thinking of the future as something distant or uncertain. See it as a choice available to you in this moment.

2. Visualize as if it were now: Whenever you think about what you want, bring it into the present. Imagine that you are already living it.

3. Feel it as truth: The feeling is the link between you and the desired reality. When you feel that you already have what you want, you activate the corresponding state and allow it to manifest.

4. Let go of the illusion of “waiting”: If time is an illusion, there is no real “waiting.” You are simply experiencing in the physical what you have already accepted within yourself.

Why does time seem linear?

Our brain processes experiences sequentially to make sense of the world around us. This linearity is useful for practical tasks, but it is not the absolute reality. At deeper levels, time functions as a “field” where everything already exists.

When you understand that time is not a barrier, you realize that you can “jump” from one reality to another simply by choosing where to place your focus and energy. This change in perspective eliminates the idea that there is something to be “achieved” in the future — everything you want is already yours.

Conclusion:

Time is not linear; it is a construct perceived by our mind. Everything already exists simultaneously — past, present, and future are available in the “now.” This means that you can access any state or reality you desire, because, in essence, everything is already created. You just need to align your consciousness with what you wish to experience.

#law of assumption#loassumption#loa tumblr#manifesting#loa blog#neville goddard#loass#loa#manifestation#law of manifestation#loass success#loass states#loassblog#time#time travel#revision#loa success#live in the end#living in the end#loafers#loablr#shiftinconsciousness#shifting motivation#shifting community#shiftblr#reality shifting#shifting blog#shifting consciousness#shiftingrealities#desired reality

539 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harley Sawyer x Reader

NOTE: reader is gender-neutral. Scenarios are often sporiadic.

( Because there's little to none and it upsets me greatly how out of character people write him as or label him as yandere, in the few writings there are about him. So I'm going to try my hardest to keep him strictly canon. )

Pre-Experiment 1354.

At first he might come across as grouchy, irritable even.

Then, there is interest. Genuine interest. He wants to study you, see what makes you tick.

Realistically, Harley seems to be quite literally incapable of caring about anyone that isn't himself in a normal way most would expect. His form of feeling 'love', in his mind, is really just a sugarcoated form of saying "I need you alive, you are useful and resourceful to keep."

He does not feel love in the traditional way, that doesn't mean he doesn't care for you. He just does not feel.

His way of showing love is through acts of service, verbal affirmations and gift-giving. He keeps a list of what you like, your interests, and important dates.

Complimenting him or any sort of praise instantly sends dopamine in his brain. Inflating his ego. Automatically in his best mood.

And boy is he smug. He doesn't even attempt to hide it.

He'll keep a facade, perhaps not even tell you about the kind of 'workplace' he's part of at Playtime Co., he needs you to trust him, and you can trust him! He needs you.

Although he uses emotional manipulation, it is not done with malicious intent. He seeks to build a meaningful relation with this person that he wants by his side.

You can sometimes tell he's very... robotic with his behaviour, his gentle voice can only make his charm go so far.

But god does he try, he doesn't even get mad and threaten you for forgetting to take out the sweet pickles in his sandwich! Instead politely reminding you that he dislikes them😁

His perception of having a partner is a very alien concept to him. It feels like focusing on his work for another Bigger Bodies Iniciative experiment, there's that same passion behind to get to know you. He carefully constructs a face to seem normal for you, and studies your behaviour in the back of his mind. Observes you, takes note of what you tell him, etc.

He acts like he's studying a future guinea pig for Playtime Co., honestly. Yet the thought of using you never even crossed his mind.

Physical contact is another thing that feels alien to him, you can feel him stiffen when you hug him, he remains frozen for a few seconds before reciprocating. You can get a small glimpse of his almost-robotic attempt to recreate genuine human emotion. He'd start sputtering incoherently when you'd suddenly give him a peck on the lips.

"No, don't worry, you don't need to ask for my consent, I allow it, you and only you are allowed. I was simply unprepared."

You of course get concerned everytime he freezes or doesn't respond right away, thinking you've crossed boundaries since he noticeably grows tense. But he's always reassured you that he does not mind, he merely gets surprised.

The one time you've managed to aggravate him is by being so insistent on making sure he was consenting because of his initial reactions. He wouldn't audibly admit "Yes I like you holding my hand, hugging me, kissing me." But he WILL angrily tell you something along the lines of "I do cherish your displays of affection. Believe me, you will know if something upsets me."

It's a half-joke half-genuine warning. He's aware of his inability to get along with most people because of his anger.

With you... he's making an attempt to be less volatile. Even at work his shift in behaviour is noticeable when he thinks of you.

He genuinely struggles to grasp the concept of why he'd allow himself to have a loved one at all, having internal fights with himself about the 'pointlessness' of it, realizing the hypocricy of it given his disgust at others for feeling sympathy for his experiments.

He eventually comes to terms that he is allowed to have a loved one because he deserves to be appreciated for his work and how hard it is to share his workspace with people who are objectively inferior and incompetent.

He makes sure to keep this relationship secretive as humanly possible. The last thing he needs is for Leith or anyone at Playtime Co. to discover he has a weakness. He has a loved one too.

Although he doesn't show it, and you need constant reminders from him, that he does enjoy physical contact, he's just kind of like a ragdoll. He allows it but doesn't often reciprocate, and when he tries to- it's often awkward and very automatic like he's trying to copy what you're doing, he prefers to recieve contact rather than giving it. Again, it's another thing that fuels his ego.

He doesn't understand you fully, your compassion, your display of emotion, your sympathy.

And it's what draws him further in, mixed with disgust at how 'lovable' you are. It makes him question himself (not in a moral/self-reflection way, oh no no no, more of a 'why do I like this? This is counterproductive for my work. But I like it.' way) and it makes him question human nature, what it is that draws us to seek closure in such a way towards one another.

He might get vocal about that. And you're going to end up getting a semi-pessimistic philosophy lesson, all because you wanted to cuddle.

Post-Experiment 1354.

Remember his ragdoll-non reciprocative behaviour when you'd initiate physical contact? Suddenly he regrets not having indulged you more often, or asked for more.

Probably laughs at himself over the irony of how he didn't value simple things he had daily access to, and now that has been taken away, and he resents that.

Should you be able to find him in this state, in however way you managed to dig so deep into the foundation to find him, and should you be able to still see him with the same eyes you did before even in the state he's in, discovering what he'd done. Well, you'll make his (metaphorical) jaw drop.

After the shock, there is an uncharacteristic fear. Because of the Prototype, it must know you are here just as well as he does, but it does not know your connection to him, and he must keep it that way.

You refuse to go? He'll go on a long-winded monologue about himself (of course), how stupid one must be to refuse to run away from danger, proudly boasts about his work, it's purpose, long story-short: he fully tears off the mask. Because what he wants is to get you out. He doesn't want you to leave him, but you are useless to him if you are dead.

You want to stay? Even after all of this? With the state that he's in? Being only a brain, lungs and liver inside Vital System Center machines?

He laughs. Starts genuinely pondering your sanity, and survival instincts.

As you approach the large machinery containing his mind, visible through the glass, his laughs grow silent. Waiting.

"Do you think yourself a hero? Coming to rescue the beast?" He'd condescendingly ask you to break the silence, dead-serious and mildly irritated that you'd be that stupid to risk your own survival for him.

"I don't. You deserved it."

Silence. Then, laughter booming through the lab.

"My, my! And here I thought you were always such an understanding golden heart. What happened to the old Y/N?"

You two argue. He's very mad at you for being so stubborn on staying with him even though now you know in full detail of just how evil he is. As if your relationship with him can ever go back to normal like before.

You are within his grasp, in his lab, deep down an abandoned toy factory. He could turn you into his next, newest experiment, he could feed you to Yarnaby, he could dissect you and keep you alive just like himself.

Yet he doesn't.

Something in his evil, metaphorical heart stirs.

You, the only person that he could tolerate. Could get along with. That he felt... something for. Something worth keeping.

"I've missed you."

Make no mistake, he says that with absolute seething spite. He hates the sentence he just uttered from the speakers.

But alas, it is a bitter truth.

Silence

...

He can't feel per-say your arms wrap awkwardly around the giant machinery containing his mind, but he sees it through his cameras, ever so-intently observing you; he heard it, as your clothes' fabric brushed and pressed against the metal.

Another incredulous laughter rasped from the speakers.

Though he can't feel it, it... warms him, in a way, that you still somehow find it possible to 'love', to care.

"I wonder... perhaps, somewhere deep down, we share a kinship of depravity? Or maybe you're just blindly loyal as my dear Yarnaby?" He'd playfully mock.

One thing is for certain though: you intrigue him. He doesn't understand you, your affections towards him, and it makes him want to keep studying you.

His mechanical vessels are a bit trickier to 'cuddle' with, if at all. You're welcome to try, Harley won't stop you, just be careful not to open a wound that'll require stitches.

He does appreciate the effort. And this time, unlike when he was human, he initiates contact first.

His hand reaches for yours, guides you to touch his screen. Although he can't feel it, he tries recreating the sensation in his mind.

You hear him sigh often when he feels content. And/or hum.

He might grumble incoherently in the typical old man fashion and try to pick at you in his typical, eloquent way of speaking, if you try to point out his hypocrisy towards his carelessness for others having loved ones.

#my writing#harley sawyer x reader#harley sawyer#dr harley sawyer#gender neutral reader#poppy playtime#poppy playtime 4#poppy playtime 4 safe haven

381 notes

·

View notes

Note

Mmmmm and that's why batman is (my headcanon) defacto field medic followed by green lantern/green arrow

No superpowered person is allowed, superman can assist by telling you where exactly the break is , but not even the flash with fast healing is allowed - the flash because I think his faster healing screws his perception of what is walk off vs evac

Batman first - he's got the knowledge and training, has the supplies, can keep a clear head

Then Green Lantern - he's also got the knowledge, training, and experience, plus his ring constructs can help immobilize and evacuate

Green Arrow - last resort because they do also have the training and supplies, But arrow is usually long range so he would have to get pretty close to a fight just to help

Yeah! The odds of someone with super powers making it worse in a high tension moment are way too high. All it takes is one misjudged intervention and that person is off the field for months instead of weeks.

Batman has the best field medicine but I can hear an argument for Green Arrow too. Hal gets points until the ring starts turning him into human-adjacent over time and he forgets what human pain levels are.

#asks#anon#tw injury#jl#justice league#batman#bruce wayne#dc#clark kent#superman#green arrow#Oliver Queen#Hal Jordan#green lantern

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creating Compelling Character Arcs: A Guide for Fiction Writers

As writers, one of our most important jobs is to craft characters that feel fully realized and three-dimensional. Great characters aren't just names on a page — they're complex beings with arcs that take them on profound journeys of change and growth. A compelling character arc can make the difference between a forgettable story and one that sticks with readers long after they've turned the final page.

Today, I'm going to walk you through the art of crafting character arcs that are as rich and multi-layered as the people you encounter in real life. Whether you're a first-time novelist or a seasoned storyteller, this guide will give you the tools to create character journeys that are equal parts meaningful and unforgettable.

What Is a Character Arc?

Before we go any further, let's make sure we're all on the same page about what a character arc actually is. In the most basic sense, a character arc refers to the internal journey a character undergoes over the course of a story. It's the path they travel, the obstacles they face, and the ways in which their beliefs, mindsets, and core selves evolve through the events of the narrative.

A character arc isn't just about what happens to a character on the outside. Sure, external conflict and plot developments play a major role — but the real meat of a character arc lies in how those external forces shape the character's internal landscape. Do their ideals get shattered? Is their worldview permanently altered? Do they have to confront harsh truths about themselves in order to grow?

The most resonant character arcs dig deep into these universal human experiences of struggle, self-discovery, and change. They mirror the journeys we all go through in our own lives, making characters feel powerfully relatable even in the most imaginative settings.

The Anatomy of an Effective Character Arc

Now that we understand what character arcs are, how do we actually construct one that feels authentic and impactful? Let's break down the key components:

The Inciting Incident

Every great character arc begins with a spark — something that disrupts the status quo of the character's life and sets them on an unexpected path. This inciting incident can take countless forms, be it the death of a loved one, a sudden loss of power or status, an epic betrayal, or a long-held dream finally becoming attainable.

Whatever shape it takes, the inciting incident needs to really shake the character's foundations and push them in a direction they wouldn't have gone otherwise. It opens up new struggles, questions, and internal conflicts that they'll have to grapple with over the course of the story.

Lies They Believe

Tied closely to the inciting incident are the core lies or limiting beliefs that have been holding your character back. Perhaps they've internalized society's body image expectations and believe they're unlovable. Maybe they grew up in poverty and are convinced that they'll never be able to escape that cyclical struggle.

Whatever these lies are, they'll inform how your character reacts and responds to the inciting incident. Their ingrained perceptions about themselves and the world will directly color their choices and emotional journeys — and the more visceral and specific these lies feel, the more compelling opportunities for growth your character will have.

The Struggle

With the stage set by the inciting incident and their deeply-held lies exposed, your character will then have to navigate a profound inner struggle that stems from this setup. This is where the real meat of the character arc takes place as they encounter obstacles, crises of faith, moral dilemmas, and other pivotal moments that start to reshape their core sense of self.

Importantly, this struggle shouldn't be a straight line from Point A to Point B. Just like in real life, people tend to take a messy, non-linear path when it comes to overcoming their limiting mindsets. They'll make progress, backslide into old habits, gain new awareness, then repeat the cycle. Mirroring this meandering but ever-deepening evolution is what makes a character arc feel authentic and relatable.

Moments of Truth

As your character wrestles with their internal demons and existential questions, you'll want to include potent Moments of Truth that shake them to their core. These are the climactic instances where they're forced to finally confront the lies they believe head-on. It could be a painful conversation that shatters their perception of someone they trusted. Or perhaps they realize the fatal flaw in their own logic after hitting a point of no return.

These Moments of Truth pack a visceral punch that catalyzes profound realizations within your character. They're the litmus tests where your protagonist either rises to the occasion and starts radically changing their mindset — or they fail, downing further into delusion or avoiding the insights they need to undergo a full transformation.

The Resolution

After enduring the long, tangled journey of their character arc, your protagonist will ideally arrive at a resolution that feels deeply cathartic and well-earned. This is where all of their struggle pays off and we see them evolve into a fundamentally different version of themselves, leaving their old limiting beliefs behind.

A successfully crafted resolution in a character arc shouldn't just arrive out of nowhere — it should feel completely organic based on everything they've experienced over the course of their thematic journey. We should be able to look back and see how all of the challenges they surmounted ultimately reshaped their perspective and led them to this new awakening. And while not every character needs to find total fulfillment, for an arc to feel truly complete, there needs to be a definitive sense that their internal struggle has reached a meaningful culmination.

Tips for Crafting Resonant Character Arcs

I know that was a lot of ground to cover, so let's recap a few key pointers to keep in mind as you start mapping out your own character's trajectories:

Get Specific With Backstory

To build a robust character arc, a deep understanding of your protagonist's backstory and psychology is indispensable. What childhood wounds do they carry? What belief systems were instilled in them from a young age? The more thoroughly you flesh out their history and inner workings, the more natural their arc will feel.

Strive For Nuance

One of the biggest pitfalls to avoid with character arcs is resorting to oversimplified clichés or unrealistic "redemption" stories. People are endlessly complex — your character's evolution should reflect that intricate messiness and nuance to feel grounded. Embrace moral grays, contradictions, and partial awakenings that upend expectations.

Make the External Match the Internal

While a character arc hinges on interior experiences, it's also crucial that the external plot events actively play a role in driving this inner journey. The inciting incident, the obstacles they face, the climactic Moments of Truth — all of these exterior occurrences should serve as narrative engines that force your character to continually reckon with themselves.

Dig Into Your Own Experiences

Finally, the best way to instill true authenticity into your character arcs is to draw deeply from the personal transformations you've gone through yourself. We all carry with us the scars, growth, and shattered illusions of our real-life arcs — use that raw honesty as fertile soil to birth characters whose journeys will resonate on a soulful level.

Happy Writing!

#writing#writeblr#thewriteadviceforwriters#creative writing#on writing#writers block#writing tips#how to write#writers and poets#writers on tumblr#authors on tumblr#author#historical fiction#fiction#novel#publishing#short stories#short story#character arcs

787 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demons and Marriage: what this means and looks like to beings who exist for so long

What is marriage? A social construct, a means for companionship, or something else? Whatever the case may be, at this point whatever original purpose it was to have has changed over time. Hell, one can assume even before marriage people coupled up and stayed with one individual as partners for life.

But what about if you’re essentially immortal?

Are divorces common due to individuals simply getting tired after so long together? Or perhaps not, due to those people’s perception of time reaching much farther than our own?

Unfortunately, despite the game having a whole event (kinda 2) dedicated to this concept, and this being a ROMANCE game, we never get much information on how demons see marriage. Hell, it even is made very evident in-game trends in the human world influence the Devildom so who’s to say the concept of marriage isn’t one such thing, a new oddity the populace is fascinated about for a moment before moving on to the next thing. Lust, and Greed are major concepts in the Devildom, who’s to say they’d hold such a concept as ever lasting companionship with a single individual in high regard at all?

All we can do is speculate as to what this could be like.

Demon Society: what place could marriage have (control and companionship)

In older human society marriage seemed to have two major purposes, power and reproduction. Would these concepts apply to demons though?

One thing that is made very clear is that one’s place in the societal hierarchy in the Devildom is almost completely, if not solely determined by one’s strength, one’s power. Despite the brothers being fallen angels, and not having been around for long they were able to quickly carve out their place in society as the Devildom’s new seven rulers. In part could be in thanks to Diavolo, they were more easily able to settle in, but even with Diavolo, all eight of them clearly had decenters from all sides, angels, Devildom Elites, ect, who did not like this arrangement and wanted it to fail. Even Diavolo couldn’t fend off all that, the brothers still had to fight and prove themselves, if not worthy than at the very least capable. Capable of fighting back, capable of defending/not embarrassing their benefactor, capable of slinking into every crack and crevice of society, of embedding themselves to become irreplaceable, capable of making it so that their absence would surely spell destruction. Make themselves needed, useful.

With this logic marriage couldn’t be used as a method of ‘climbing up the social ladder’ as can happen in human society. Sure, it could be used as a short-cut, but if one can’t prove their strength they’ll be eaten alive.

If marriage were to be used as a tool for power, it’d likely only be among the elite. After all, what better way of making sure another family doesn’t try… I don’t know, eliminate your whole family to get more reach, than by getting a long standing hostage. If the demons were strong enough and had the motivation they would have clawed their way into power so the act of marriage could act as more of a bargaining chip, a way to declare peace or as a way to keep other families in check. Even if not strong enough, they are still greedy, prideful creatures and may try getting more power even if they don’t have the strength to reach it. Or perhaps, families could simply agree to marriage to pool their power, get more strength and alliances to take out bigger competition together.

For demons, unfortunately, marriage cannot be used to make a powerful heir, demons are incapable of making more of their own in such a way unlike humans, so marriage for them, if used as a tool can solely be used to make social ties, nothing more. Even then, IF they were capable of repopulating in such a way marriage isn’t a biological component needed for that process. (This is elaborated in this headcannon. Just jump to the section titled: Demon/Angel Bodies: how they operate lacking physicality (population and family))

Sure all the above could technically apply to lesser demons, but as seen time and time again, lesser demons can’t even hold a candle to the strength of their nobility.

Then do they have any use for marriage?

Well, what use is marriage to the lower and middle classes of human society? It really just depends on the individuals, sometimes it’s to get on another’s insurance, maybe they love one another and want to keep each other close, perhaps they feel pressured to by outside forces like family or religion.

I did say before demons are a more promiscuous bunch somewhere in the opening paragraphs, but that exact statement can also be turned around. I mean just look at the brothers and how over and over they fight to keep you all to themselves. If nothing else, if not even for the romance of it all, marriage could be common for the sake of wanting to lay claim to another.

I believe that marriage as a concept wouldn’t be foreign to demons, but it also wouldn’t be the most common practice, more so something reserved for the elite in their constant power struggles. After all, as sad as it may sound, living for so long it’s only natural for things to just change over time, to just grow apart into different people. Lesser demons do marry but more often than not they forgo that to simply enjoy their time together, move in, ect. Perhaps later on they would but it’s not a guarantee or pressure to do so, not from society at least. There are few to no social benefits to marriage for lesser demons at least. Human society places such an importance on marriage and having kids but when the whole ‘having kids’ thing is eliminated, society doesn’t have much of a need for marriage outside of tradition or control. (Yes there are technically other things such as being a dual income household, but that kinda stuff is more dependent on individual couples and their dynamic and what they want and I can’t account for EVERY possibility.)

Demons and Courting: Showing Interest

SO! This may be a topic less related to marriage specifically and coupling in general, but the concepts are intrinsically intertwined, how is a demon to show they have an interest in another?

Well, just as many forms as humans have to express their interest, verbally, gift giving, ect, demons do those too. However if one were to pin down specific behaviors it would be going out of the way for their person of interest. Acts of service. Getting someone their favorite tea without them asking when their tired, carrying their bookbag on the way back from school, if the person they like is shorter rearranging the kitchen shelves so the things they get frequently are within reach.

The most romantic form of flirting to a demon is little everyday moments of making life easier. One can boast of their love as much as they want, or even kiss and to showoff one’s wealth, but for naturally selfish beings to accommodate another in their life, to be so filled with thoughts of another to try and want to improve their life in even the smallest, most easily overlooked of ways? Swoon worthy. Big shows are just that, shows, but little thing require thought, require dedication, and THAT is what demons find attractive DEDICATION.

Sure, MC helped mend a broken family so it makes sense why the brothers fell for them, but what about the others? Even if it wasn’t for them directly, time and time again they all witnessed this human’s dedication they give to those they love, who wouldn’t want someone like that to look their way? To be on the receiving end of that?

This, little everyday moments, thought of another, also explains why true demons, and not fallen angels, have positive interactions with being ignored in ‘Surprise Guest’. The brothers, are not true demons, and they live rather separated from demon kind, mostly keeping to their own despite being rulers, so some of their actions is more reminiscent of angels, they aren’t truly bathed in demon culture and ideology, nor do they completely still carry angelic ideologies either, a little of both, not completely aligned with one or the other in their actions.

However, Diavolo, Barbatos, and Solomon all have a deep understanding of demon culture, they can see the charm of being ignored. The worst thing that another can do to a demon is neutrality, to not care one way or the other at all. However, to be ignored? For someone to just exist beside them, that is a special, and a rarer kind of effort one can’t find in too many other forms. It takes a lot of work to not react to another’s presents or to simply exist beside another, to so willingly share a space. That’s something only true demons or one who truly understands their culture could see the dedication that action requires. (Technically Simeon has ONE ‘Surprise Guest’ line where he likes being ignored but the line is “I didn't expect to run into you at such an hour. What's wrong? Couldn't sleep?” I interpret that is he assumes you’re falling asleep, and THAT’S what he likes, not the action itself)

Related Tangent: To reject their feelings is to reject that demon’s existence Though many imagine demons as cunning, conniving creatures they are much more honest and blunt than their angelic counterparts. If a demon likes you, you’ll know it. Demons being less physical than humans in their existence (more on this here) emotions ARE them. Humans tend to separate and compartmentalize everything, to the extent that we tend to treat our mind and emotions as separate from the person, as things that happen TO and are not FROM or PART of us. To demons hiding their emotions is strange behavior because in essence, that’s hiding who you are. There are some exceptions like embarrassment, or if one were unsure about their own feelings, but these feelings are never ignored or separate from them. Demons are all about living in the moment, indulging in any desire NOT being honest with how one is feeling is simply counter productive to that. However this in itself has consequences should one reject a demon. To reject a demon’s feelings is to reject them as a whole not just their attraction to you. That is why, even if you have a partner or clear favorite among the cast, the rest still make their feelings known, they’re not trying to push themselves upon you, you may not feel the same, but they are still friends and family and with some exceptions depending on the person, one likely wouldn’t want to reject them as a whole. So one accepts that they have these feelings, but perhaps not reciprocate them. Rejecting someone and not reciprocating another’s feelings are seen as TWO VERY DIFFERENT INCIDENTS FROM EACH OTHER!

There is however one other form that is a more specific form of dedication, and that is the act of creation. To create is to put a part of yourself into it whether it be emotion or time. Most often found in the form of cooking or sewing this can also just be seen as a caring act in general… IF you are a demon. HOWEVER if one is human and do this, ANYTHING that takes time from your terribly short life to create? That is priceless, that could be akin to proposing if you say the right things. It’s one thing to give a gift for a holiday or make dinner when it’s your turn the recipient could brush it off, but any ‘just because’ gifts? Whoever you gave that too will likely be asking you some interesting questions very soon like where you’d want to move and if you’d want one wedding, or two so you could have a separate ceremony in each world, or how weddings are done in the human world in general. Or they may just burst into tears on the spot and hug you, promising to make you the happiest person to have ever lived and thanking you for choosing them out of everyone.

Demon Marriage: The Ceremony/ Post Marriage/Coupled Traditions

So you and your sweetheart want to get hitched, how do you do that?

As marriage as a concept is not held in as high a regard as it is for humans, the wedding ceremony in particular doesn’t have to go any particular way. Some demons might just throw a giant party, others may go into the wilds and hunt the worst beast they can find as a way of solidifying their bond through shared strength, some do nothing and treat proposing as the marriage itself and call it a day.

For humans a marriage ceremony generally has religious undertones, from the event being held in churches, to swearing to god, ect. Demons obviously do not want blessing from ‘Father’ for their own unions.

Though demons do not have much of a ceremony generally should demons decide to wed they create something together, something they pour all of themselves into making, a pure expression of their partnership. The two most common forms this takes are either ‘their call’ or a dance/song.

Generally if one is not in a relationship with a demon one would not see or experience any ‘calls’ or ‘song/dance’ second hand. Demons are their emotions and to do either of these publicly would be showing such a raw part of one’s self, something too close. These acts are demons attempts to connect with their partners as deeply as they can. The act of using emotion, to create using themselves, to expose all of themselves with their partner, that’s what these are. To tie one another together. These are what they generally have in place of a wedding ceremony.

Their Call:

Demon language can at times be slightly more guttural than humans or angels. A chirp for explanation here, a cackle as a swear there, demons speak like this all the time, it’s mixed into words and tone, but since humans partially can’t comprehend demons and angels’ existence the little the brain can understand usually interprets these sounds as either being off in the distance or giving whoever is speaking a ‘Devildom accent’.

Though Angels technically have the capacity to make these sounds too, the act of doing so is looked down upon, to make these sounds is to act on instinct and to act on instinct, to not have ‘perfect self-control’ is to be seen as a demonic trait.

A ‘Call’ in essence is a nickname. A new special name solely for one’s partner/spouse/mate. This call is made up of these guttural sounds solely. Generally the kinds of sounds one can hear being made reflect what base class the demon is (more on this here jump to Demon/Angel Bodies: more sensitive to the nonphysical (heat cycle)) although there are some exceptions. Once such is Satan, though his base class elemental his sounds usually come out as the hissing of a fire being put out with water, for a mate however his call would be more akin to guinea pig chirps (he has tried mimicking cat chirps for himself but to no avail). A partner’s ‘call’ should over time come naturally to a demon, even more so than their partner’s proper name. It’s rarer to hear such calls though, as generally they are only used in private, or around family.

The Song/Dance:

This is just as it says on the tin. The demons make a song and/or dance that encompasses all that they are to each other. Some demons’ engagements last centuries because they are still practicing and refining this together and only once they are satisfied will they be wed. Songs/dance are one of the most emotion filled things one can create so for these beings to do this as a form of deep connection comes very naturally.

Some keep it simple to a short tune, something they can whistle or hum to one another in greeting and shared with one another often. Some make a whole choreography and save performing it for special occasions only. Some use magic to make the music while they dance, some keep small portable instruments on hand always to play it together.

Given the lifespan of demons on occasion they simply have to be separated for long periods of time due to work, or one’s physical form dieing and needing time to regenerate, or reuniting after another cycle of destruction of the three worlds (more on that here… kinda jump to the fourth paragraph under Demon/Angel Bodies: how they operate lacking physicality (population and family)), to make sure it truly is one another they do their song/dance, after all only their partner(s) know it by heart.

Should the MC marry Beelzebub, Beel being a more simple guy would likely go for something where the MC sings lyrics they wrote while he takes the lead in a dance with him doing most of the work. He’d likely be one to hum the melody to himself or MC rather regularly. It’d likely end up sounding something like Mili’s Gluttony.

For someone with more complex tastes Mephistopheles could be taken for example. Something so grand and complicated like his feelings for you. If one were to marry HIM, he’d except nothing less than someone he sees as a true equal. A duet where you both share equal work in dancing and similar amounts of time singing is what he’d insist upon. Something like Valkyrie’s Le temps des fleurs. Lyrics and something like this Dance but different since not performed for an audience, only each other. Mephisto being a romantic would always wish to perform with you on special occasions, this includes date nights.

And THAT is what I believe marriage would be like for demons.

Idk how to end this, the last headcannon post thing has a much easier transition to a conclusion than this one…

Guess I can state why I made this? Or my headcannons in general.

Obey Me! Season One of the OG game, as a concept, FACINATES me. I love these games and the characters they present but I feel sometimes they fall short of their potential, but that’s understandable, what I want and what they’re trying to accomplish are two separate things. I came into this with the idea of a cultural exchange program. I wanted to see the differences between this world’s demon and human societies, and since this was a dating sim and not just a visual novel, how beings having relationships with differing cultural backgrounds would effect that. And yet to me it feels like demons are just… more magical humans with cool looking accessories and some murdery tendencies.

AND NOW I HAVE MORE TO ADD AFTER THE ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE NEW APP LITERALLY AS I WAS FINISHING THIS!!!

I sincerely doubt we’ll ever get to see too much cultural differences or Devildom culture in general, at least not the parts of it I’d like to explore. Especially more so since they are specifically calling this an ‘app’ and not a ‘game’ so idk if there will be too many visual novel elements to it or not.

I make headcannons because I’ve grown to loves these characters and this world and want to see it fleshed out, but in-game only so much time can be allocated to the hierarchy structure of demons, especially with a cast as big as OM!’s with just about all of them being romancable in a romance game. So instead I’ve allowed it space in my mind, my life, to ruminate on this and explore concepts I can only dream would be looked into. And it’s a fun convenient excuse to keep doing so. Although I probably would be doing so anyway.

#vexing hours#obey me#obey me headcannon#obey me headcanons#obey me x mc#obey me x reader#obey me worldbuilding

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

march 23, 2025

i drew the first three pages of this last week, but didn't really know what i was going to do with it. then i kinda had an epiphany while i was stoned again, and after thinking about it for a while, decided i was going to bother with these after all.

then after reading the first three pages again, i started to understand where my discomfort was coming from, and that's where the final two pages come from.

the thing is, i'm not depersonalizing all the time. i'm not right now, and i drew this approximately 5 hours ago (from time of writing), while i was depersonalizing. reading it now, it sounds ridiculous. of course my identity exists outside of the confines of a sheet of paper. but when i'm depersonalizing, i don't exist at all. the cartoon characters that flicker in and out of perception in my brain become as real as i am, and it's a strange feeling to have ever believed that they only live in the ink markings on paper and in my own imagination. my identity is as constructed as they are, so who am i do deny their reality?

but then i go back to normal and recognize it for what it is, and everything recedes into shadows again.

i kinda had the realization that starling is who i become when i'm depersonalizing. i didn't make him with that intention, but that's what happens. he took up that mantle by being the most recent new iteration of my bird fursona. there's only one of me. i usually project myself into whitewood because he's been the symbol i use for myself (my REAL self) for the longest amount of time. the cartoons themselves aren't what's important. they're not separate people, they're just humanizations of versions of myself that i fixate on when i feel unstable.

for the longest time, i have felt like "two" people, in a manner of speaking. i'm the "me" i am normally, and i'm the "me" i become when i'm Not Normal. that's the depersonalization. it finally makes sense to me. maybe i can, at long fucking last, move on from this. i'm so tired of it.

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

𐙚 PROPAGANDA .ᐟ.ᐟ part 1

🖇 MYTH : ❝You need to affirm 24/7.❞

🖇 TRUTH : False. If you understand that your assumption is the only truth, it will remain so without needing constant affirmation. Affirmations are simply reminders of what you already know.

🪽 MYTH : ❝Wavering affects your manifestation.❞

🪽 TRUTH : False. If you believe your manifestation is already yours, brief doubts won’t change that. Doubts only affect you if you let them. Your reality = your rules.

🐚 MYTH : ❝Manifesting takes time.❞

🐚 TRUTH : False. Time is a mental construct. It only exists in your perception. You are not waiting for your manifestation to arrive. The moment you assume it is yours, it is. Smile at the mirror, and it will smile back at you instantly.

🖇 MYTH : ❝The 3d is your enemy.❞

🖇 TRUTH : False. There is no harm in referring the 3d as your bitch, but remember the 3d is a reflection of you. Change within, and the 3d will have no choice but to follow.

🪽MYTH : ❝Crashing out resets your manifestation.❞

🪽 TRUTH : False. A red light doesn't mean it's over. You are human. Setbacks are natural and nothing to be ashamed of. What matters is that you keep going and stay committed, no matter what.

🐚 MYTH : ❝You can only manifest instantly through the void state.❞

🐚 TRUTH : False. The void state is just as effective and valid as affirming and persisting. There's no need to put it on a pedestal. It is simply one of many tools. Besides, you’ve got to be honest with yourselves. The reason some rely on the void so much is often because they’re looking for the "easiest" way out. Am I right or am I wrong?

🖇 MYTH : ❝You need methods to manifest.❞

🖇 TRUTH : False. All you truly need is yourself. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: manifestation doesn’t depend on methods. You manifest, methods do not. Trust yourself as you are the key. Mwah, Angie. - 𝜗𝜚

#do not fall for these#manifesting#law of assumption#loa#neville goddard#manifesting is easy#manifesting community#manifestation#law of attraction#master manifestor#the void state#voidblr#the void#shiftblr#shifting#shifter#reality shifting community

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know what? I don't think the show will (or should) yet address the fact that reactions to the deaths of SecUnits and the reactions to the deaths of humans are starkly different, even for the Preservationers.

I think this for two reasons: one, the nature of why that might be different sort of needs to get explored more. Do they not think of the other SecUnits as people (possible), or is it the helmet? See, most humans have a much easier time not attributing personhood or complexity if they can't see someone's face. It's why enemies in video games so often tend to be faceless. It's why certain fascist regimes throughout history have their secret police hide their faces. Because it is the goal to un-people them and make them Other. And that was clearly part of the design philosophy of SecUnits, so much so that people just don't know that there is, in fact, a face under that helmet. So it's easier to see a helmeted, unpersoned being die, especially if it has been openly attacking you first, rather than see a person whose face is exposed, and who you have perhaps talked to or even gotten to know, die, even under similar circumstances.

But there are definitely deeper questions about the personhood of constructs in general that need to be explored. But before PresAux can truly unpack their unconscious depersonization of SecUnits, Murderbot has to unpack its own depersonization of itself and other constructs.

I don't think that Murederbot considers itself a person yet. I don't think it's sad that other SecUnits die, because it actually, secretly, agrees with what Gurathin has been saying: SecUnits aren't people, they're equipment. It is equipment, and all these new emotions, the empathy, the kindness that has been laced through it by these people, these are viruses. It's not a sign of personal growth, because it's not a person! It has so many emotions and thoughts and perceptions, and the best way it's found so far to understand them is filtered through shows. But it has yet to understand that all these things are signs that it is, and has always been, a person. Honestly, given what's just happened at the end of episode 9, I think Gurathin's reevaluating his opinions on Muderbot's personhood far sooner than Murderbot is.

It has to go on its journey of self-discovery before it can really embrace that it is, in fact, a person. Not equipment, not just a thing, but a PERSON. And only when it confronts that, and its own callous opinions of its death and the deaths of other SecUnits, will it really be able to grapple with the disparity and the prejudice inherent in the way SecUnit deaths are treated.

It's very likely that, if it leaves at the end of the season, PresAux grapple with this concept and their reactions to the various deaths they witnessed on their own. After all, they are emotionally intelligent people who will likely be asking themselves why it left them. We may have a subplot of them working through their own prejudices toward constructs, and the flaws in Preservation thinking about bots and constructs (in the books, at least, very paternalistic). I would really like to see them grapple with that on their own, and Murderbot grapple with it on its own, in the way that it reluctantly grapples with all large, emotional concepts. I would like them to come back together both in different places, and on different and better terms. But I think they would still have growing to do, because it's one thing to deconstruct your own prejudices in a bubble, but ideally that deconstruction should be informed by the opinions and thoughts of people within the group you were prejudiced against, so I would imagine they would still have plenty of mutual character growth to go once it rejoins them.

But that's not something that can be grappled with in one episode. That is a LONG arc, likely a parallel arc for next season, which may well continue beyond season 2, if we get lucky enought to get seasons 3+ (given Apple's track record, I would be surprised if we don't at least get season 2; they tend to prefer giving their shows room to grow, and MB has stayed in the top 5 viewed shows for the entire season, so it's not like it's performing poorly by their metrics).

I see season 2--assuming it's some remix of 'Artificial Condition', 'Rogue Protocol', and original material--as the season that really grapples with the nature and personhood of constructs. Season 1 set up the characters and the larger world, as well as the stakes. Season 2 can, hopefully, move forward with some of the deeper topics at play.

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonconformity, ambiguity, fluidity and misinterpretation: on the gender of Inanna (and a few others)

This article wasn’t really planned far in advance. It started as a response to a question I got a few weeks ago:

However, as I kept working on it, it became clear a simple ask response won’t do - the topic is just too extensive to cover this way. It became clear it has to be turned into an article comprehensively discussing all major aspects of the perception of Inanna’s gender, both in antiquity and in modern scholarship. In the process I’ve also incorporated what was originally meant as a pride month special back in 2023 (but never got off the ground) into it, as well as some quick notes on a 2024 pride month special that never came to be in its intended form, as I realized I would just be repeating what I already wrote on wikipedia.

To which degree can we speak of genuine fluidity or ambiguity of Inanna’s gender, and to which of gender non-conforming behavior? Which aspects of Inanna’s character these phenomena may or may not be related to? What is overestimated and what underestimated? What did Neo-Assyrian kings have in common with medieval European purveyors of Malleus Maleficarum? Is a beard always a type of facial hair? Why should you be wary of any source which calls gala “priests of Inanna”?

Answers to all of these questions - and much, much more (the whole piece is over 19k words long) - await under the cut.

Zeus is basically Tyr: on names and cognates

The meaning of a theonym - the proper name of a deity - can provide quite a lot of information about its bearer. Therefore, I felt obliged to start this article with inquiries pertaining to Inanna’s name - or rather names. I will not repeat how the two names - Inanna and Ishtar - came to be used interchangeably; this was covered on this blog enough times, most recently here. Through the article, I will consistently refer to the main discussed deity as Inanna for the ease of reading, but I’d appreciate it if you read the linked explanation for the name situation before moving forward with this one.

Sumerian had no grammatical gender, and nouns were divided broadly into two categories, “humans, deities and adjacent abstract terms” and “everything else” (Ilona Zsolnay, Analyzing Constructs: A Selection of Perils, Pitfalls, and Progressions in Interrogating Ancient Near Eastern Gender, p. 462; Piotr Michalowski, On Language, Gender, Sex, and Style in the Sumerian Language, p. 211). This doesn’t mean deities (let alone humans) were perceived as genderless, though. Furthermore, the lack of grammatical masculine or feminine gender did not mean that specific words could not be coded as masculine or feminine (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471; one of my favorite examples are the two etymologically unrelated words for female and male friends, respectively malag and guli).

While occasionally doubts are expressed regarding the meaning of Inanna’s name, most authors today accept that it can be interpreted as derived from the genitive construct nin-an-ak - “lady of heaven” (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period, p. 104). The title nin is effectively gender neutral (Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, p. 6) - it occurs in names of male deities (Ningirsu, Ninurta, Ninazu, Ninagal, Nindara, Ningublaga...), female ones (Ninisina, Ninkarrak, Ninlil, Nineigara, Ninmug…), deities whose gender shifted or varied from place to place or from period to period (Ninsikila, Ninshubur, Ninsianna…) and deities whose gender cannot be established due to scarcity of evidence (mostly Early Dynastic oddities whose names cannot even be properly transcribed). However, we can be sure that Inanna’s name was regarded as feminine based on its Emesal form, Gašananna (Timothy D. Leonard, Ištar in Ḫatti: The Disambiguation of Šavoška and Associated Deities in Hittite Scribal Practice, p. 36).

The matter is a bit more complex when it comes to the Akkadian name Ishtar. In contrast with Sumerian, Akkadian, which belongs to the eastern branch of the family of Semitic languages, had two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine, though the gender of nouns wasn’t necessarily reflected in verbal forms, suffixes and so on (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 472-473). In contrast with the name Inanna, the etymology of the Akkadian moniker is less clear. The root has been identified, ˤṯtr, but its meaning is a subject of a heated debate (Aren M. Wilson-Wright, Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation of a Goddess in the Late Bronze Age, p. 22-23; the book is based on the author’s doctoral dissertation, which can be read here). Based on evidence from the languages from the Ethiopian branch of the Semitic family, which offer (distant) cognates, Wilson-Wright suggests it might have originally been an ordinary feminine (but not marked with an expected suffix) noun meaning “star” which then developed into a theonym in multiple languages (Athtart…, p. 21) She tentatively suggests that it might have referred to a specific celestial body (perhaps Venus) due to the existence of a more generic term for “star” in most Semitic languages, which must have developed very early (p. 24). Thus the emergence of Ishtar would essentially parallel the emergence of Shamash, whose name is in origin the ordinary noun for the sun (p. 25). This seems like an elegant solution, but as pointed out by other researchers some of the arguments employed might be shaky, so it’s best to remain cautious about quoting Wilson-Wright’s conclusions as fact, even if they are more sound than some of the older, largely forgotten, proposals (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 40-41).

In addition to uncertainties pertaining to the meaning of the root ˤṯtr, it’s also unclear why the name Ishtar starts with an i in Akkadian, considering cognate names of deities from other cultures fairly consistently start with an a. The early Akkadian form Eštar isn’t a mystery - it reflects a broader pattern of phonetic shifts in this language, and as such requires no separate inquiry, but the subsequent shift from e to i is almost unparalleled. Wilson-Wright suggests that it might have been the result of contamination with Inanna, which seems quite compelling to me given that by the second millennium BCE the names had already been interchangeable for centuries (Athtart…, p. 18).

As for grammatical gender, in Akkadian (as well as in the only other language from the East Semitic branch, Eblaite), the theonym Ishtar lacks a feminine suffix but consistently functions as grammatically feminine nonetheless. I got a somewhat confusing ask recently, which I assume was the result of misinterpretation of this information as applying to the gender of the bearer of the name as opposed to just grammatical gender of the name itself:

Occasional confusion might stem from the fact that in the languages from the West Semitic family (like ex. Ugaritic or Phoenician) there’s no universal pattern - in some of them the situation looks like in Akkadian, in some cognates without the feminine suffix refer to a male deity, furthermore goddesses with names which are cognate but have a feminine suffix (-t; ex. Ugaritic Ashtart) added are attested (Athtart…, p. 16).

In Akkadian a form with a -t suffix (ištart) doesn’t appear as a theonym, only as the generic word, “goddess” - and it seems to have a distinct etymology, with the -t as a leftover from plural ištarātu (Athtart…, p. 18). The oldest instances of a derivative of the theonym Ishtar being used as an ordinary noun, dated to the Old Babylonian period (c. 1800 BCE), spell it as ištarum, without such a suffix (Goddess in Context…, p. 80). As a side note, it’s worth pointing out that both obsolete vintage translations and dubious sources, chiefly online, are essentially unaware of the existence of any version of this noun, which leads to propagation of incorrect claims about equation of deities (Goddesses in Context…, p. 82).

It has been argued that a further form with the -t suffix, “Ishtarat”, might appear in Early Dynastic texts from Mari, but this might actually be a misreading. This has been originally suggested by Manfred Krebernik all the way back in 1984. He concluded the name seems to actually be ba-sùr-ra-at (Baśśurat; something like “announcer of good news”; Zur Lesung einiger frühdynastischer Inschriften aus Mari, p. 165). Other researchers recently resurrected this proposal (Gianni Marchesi and Nicolo Marchetti, Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia, p. 228; accepted by Dominique Charpin in a review of their work as well). I feel it’s important to point out that nothing really suggested that the alleged “Ishtarat” had much to do with Ishtar (or Ashtart, for that matter) in the first place. The closest thing to any theological information in the two brief inscriptions she appears in is that she is listed alongside the personified river ordeal, Id, in one of them. Marchesi and Marchetti suggest they form a couple (Royal Statuary…, p. 228); in absence of other evidence I feel caution is necessary. I’m generally wary of asserting deities who appear together once in an oath, greeting or dedicatory formula are necessarily a couple when there is no supplementary evidence. Steve A. Wiggins illustrated this issue well when he rhetorically asked if we should treat Christian saints the same way, which would lead to quite thrilling conclusions in cases like the numerous churches named jointly after St. Andrew and St. George and so on (A Reassessment of Asherah With Further Considerations of the Goddess, p. 101).

Even without Ishtarat, the Mariote evidence remains quite significant for the current topic, though. There’s a handful of third millennium attestations of a deity sometimes referred to as “male Ishtar” (logographically INANNA.NITA; there’s no ambiguity thanks to the second logogram) in modern publications - mostly from Mari. The problem is that this is most likely a forerunner of Ugaritic Attar, as opposed to a male form of the deity of Uruk/Zabalam/Akkad/you get the idea (Mark S. Smith, The God Athtar in the Ancient Near East and His Place in KTU 1.6 I, esp. p. 629; note that the deity with the epithet Sarbat is, as far as I know, generally identified as female though).

Ultimately there is no strong evidence for Attar being associated with Inanna (his Mesopotamian counterpart in the trilingual list from Ugarit is Lugal-Marada) or even with Ashtart (Smith tentatively proposes the two were associated - The God Athtar.., p. 631 - but more recently in ‛Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts he ruled it out, p. 36-37) so he’s not relevant at all to this topic. Cognate name =/= related deity, least you want to argue Zeus is actually Tyr; the similarly firmly male South Arabian ˤAṯtar is even less relevant (Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation…, p. 13). Smith goes as far as speculating the male cognates might have been a secondary development, which would render them even more irrelevant to this discussion (‛Athtart in Late…, p. 35).

There are also three Old Akkadian names which might refer to a masculine deity based on the form of the other element (Eštar-damqa, “E. is good”, Eštar-muti “E. is my husband”, and Eštar-pāliq, “E. is a harp”), but they’re an outlier and according to Wilson-Wright might be irrelevant for the discussion of the gender of Ishtar and instead refer to a deity with a cognate name from outside Mesopotamia (Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation…, p. 22).

There’s also a possible isolated piece of evidence for a masculine deity with a cognate name in Ebla. Eblaite texts fairly consistently indicate that Inanna’s local counterpart Ašdar was a female deity. In addition to the equivalence between them attested in a lexical list, her main epithet, Labutu (“lioness”) indicates she was a feminine figure. However, Alfonso Archi argues that in a single case the name seems to indicate a god, as they are followed by an otherwise unattested “spouse” (DAM-sù), Datinu (Išḫara and Aštar at Ebla: Some Definitions, p. 16). The logic behind this is unclear to me and no subsequent publications offer any explanations so far. It might be worth noting that the Eblaite pantheon seemingly was able to accommodate two sun deities, one male and one female, so perhaps this is a similar situation.

It should also be noted that the femininity of Ishtar despite the lack of a feminine suffix in her name is not entirely unparalleled - in addition to Ebla, in areas like the Middle Euphrates deities with cognate names without the -t suffix might not necessarily be masculine, even when they start with a- and not i- like in Akkadian. In some cases the matter cannot be solved at all - there is no evidence regarding the gender of Aštar of the Stars (aš-tar MUL) from Emar, for instance. Meanwhile Aštar of Ḫaši and Aštar-ṣarbat (“poplar Aštar”) from the same site are evidently feminine (Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation…, p. 106). At least in the last case that’s because the name actually goes back to the Akkadian form, though (p. 85).

To sum up: despite some minor uncertainties pertaining to the Akkadian name, there’s no strong reason to suspect that any greater degree of ambiguity is built into either Inanna or Ishtar - at least as far as the names alone go. The latter was even seen as sufficiently feminine coded to serve as the basis for a generic designation of goddesses.

Obviously, there is more to a deity than just the sum of the meanings of their names. For this reason, to properly evaluate what was up with Inanna’s gender it will be necessary to look into her three main roles: these of a war deity, personification of Venus and love deity.

Masculinity, heroism and maledictory genderbening: the warlike Inanna

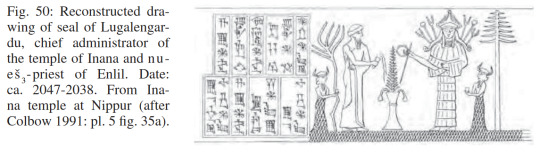

An Old Babylonian plaque depicting armed Inanna (wikimedia commons)

Martial first, marital second?

War and other related affairs will be the first sphere of Inanna’s activity I’ll look into, since it feels like it’s the one least acknowledged online and in various questionable publications. Ilona Zsolnay points out that this even extends to serious scholarship to a degree, and that as a result her military side is arguably understudied (Ištar, Goddess of War, Pacifier of Kings: An Analysis of Ištar’s Martial Role in the Maledictory Sections of the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions, p. 389). The oldest direct evidence for the warlike role of Inanna are Early Dynastic theophoric names such as Inanna-ursag, “Inanna is a warrior”. Further examples are provided by a variety of both Sumerian and Akkadian sources from across the second half of the third millennium BCE. This means it’s actually slightly older than the first evidence for an association with love and eroticism, which can only be dated with certainty to the Old Akkadian period when it is directly mentioned for the first time, specifically in love incantations (Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Inanna and Ishtar in the Babylonian World, p. 336).

Deities associated with combat were anything but uncommon in Mesopotamia. There was no singular war god - Ninurta, Nergal, Zababa, Ilaba, Tishpak and an entire host of other figures, some recognized all across the region, some limited to one specific area or even just a single city, shared a warlike disposition. Naturally, the details could vary - Ninurta was essentially an avenger restoring order disturbed by supernatural threats, Nergal was a war god because he was associated with just about anything pertaining to inflicting death, and so on.

All the examples I’ve listed are male, but similar roles are also attested for multiple goddesses, not just Inanna. Those include closely related deities like Annunitum or Belet-ekallim, most of her foreign counterparts, the astral deity Ninisanna (more on this figure later), but also firmly independent examples like Ninisina and the Middle Euphrates slash Ugaritic Anat (Ilona Zsolnay, Do Divine Structures of Gender Mirror Mortal Structures of Gender?, p. 114).

The god list An = Anum preserves a whole series of epithets affirming Inanna’s warlike character - Ninugnim, “lady of the army”; Ninšenšena, “lady of battle”; Ninmea, “lady of combat”; Ninintena, “lady of warriorhood” (tablet IV, lines 20-23; Wilfred G. Lambert and Ryan D. Winters, An = Anum and Related Lists, p.162). It is also well represented in literary texts. She is a “destroyer of lands” (kurgulgul) in Ninmesharra, for instance (Markham J. Geller, The Free Library Inanna Prism Reconsidered, p. 93).

At least some of the terms employed to describe Inanna in other literary compositions were strongly masculine-coded, if not outright masculine. The poem Agušaya characterizes her as possessing “manliness” (zikrūtu) and “heroism” (eṭlūtu; this word can also refer to youthful masculinity, see Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471) and calls her a “hero” (qurādu). Another example, a hymn dated to the reign of Third Dynasty of Ur or First Dynasty of Isin opens with an incredibly memorable line - “O returning manly hero, Inanna the lady (...)” (or, to follow Thorkild Jacobsen’s older translation, which involves some gap filling - “O you Amazon, queen—from days of yore, paladin, hero, soldier”; The Free Library… p. 93).

A little bit of context is necessary here: while “heroism” might seem neutral to at least some modern readers, in ancient Mesopotamia it was seen as a masculine trait (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 392-393). It’s worth noting that eṭlūtum, which you’ve seen translated as “heroism” above can be translated in other context as “youthful masculinity” (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471). On the other hand, while zikrūtu is derived from zikāru, “male”, it might refer both straightforwardly to masculinity and more abstractly to heroism (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 397).

However, the same hymn which calls Inanna a “manly hero” refers to her with a variety of feminine titles like nugig. There’s even an Emesal gašan (“lady”) in there, you really can’t get much more feminine than that (The Free Library… p. 89). On top of that, about a half of the composition is a fairly standard Dumuzi romance routine (The Free Library… p. 90-91; more on what that entails later, for now it will suffice to say that not gender nonconformity).

This is a recurring pattern, arguably - Agušaya, where masculine traits are attributed to Inanna over and over again, still firmly refers to her as a feminine figure (“daughter”, “goddess”, “queen”, “princess”, “mistress”, “lioness” and so on; Benjamin R. Foster, Before the Muses: an Anthology of Akkadian Literature, p. 160 and passim). In other words, the assignment of a clearly masculine sphere of activity and titles related to it doesn’t really mean Inanna is not presented as feminine in the same compositions.

How to explain this phenomenon? In Mesopotamian thought both femininity and masculinity were understood as me, ie. divinely ordained principles regulating the functioning of the cosmos. In modern terms, these labels as they were used in literary texts arguably had more to do with gender and gender roles than strictly speaking with biological sex (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 391-392). Ilona Zsolnay on this basis concludes that Inanna, while demonstrably regarded as a feminine figure, took on a masculine role in military context (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 401). This is hardly an uncommon view in scholarship (The Free Library…, p. 93; On Language…, p. 243).