Text

Second in the Mapping the CPS series: a map of Ancien Regime France with the places of birth of our notorious third CPS. On the side, you can see a timeline with the date of birth of each of the members.

Some fun facts:

The average age of the Committee of Public Safety in July 1793 was 37, with Lindet being the oldest at 47 and Saint-Just the youngest at 25.

Couthon and Prieur (Cote d'Or) share a birthday on the 22 of December.

Three of the members (Lindet, Robespierre and Carnot) were born in May (so the CPS has 3 birthdays coming up!)

The only deputy of Paris that was actually born in Paris was Collot.

I'm surprised Billaud-Varenne wasn't sent on mission to the West (instead of Prieur de Marne and Saint-André) since he was born in La Rochelle, had family there and lived there until he was 26.

Saint-André shares a birthplace with Olympe de Gouges (a rather small town called Montauban)

Where all the members were born:

Robert Lindet: Bernay

Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois: Paris

André Jeanbon Saint-André: Montauban

Lazare Carnot: Nolay

Bertrand Barère:Tarbes

Georges Couthon: Orcet

Jacques Billaud-Varenne: La Rochelle

Pierre-Louis Prieur de la Marne: Sommesous

Maximilien Robespierre: Arras

Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles: Paris

Claude-Antoine Prieur de la Côte-d’Or: Auxonne

Louis Antoine Saint-Just: Decize

#frev#french revolution#robespierre#committee of public safety#saint just#lindet#collot#saint-andre#lazare carnot#barere#couthon#billaud varenne#prieur#herault

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am geographically challenged, and I really, really wanted a way to visualise what constituencies the members of the Third Committee of Public Safety ( July 1793 – July 1794) represented. So, this map was born.

Bertrand Barère: Hautes-Pyrénées

Jacques Billaud-Varenne: Paris

Lazare Carnot: Pas-de-Calais

Jean-Marie Collot: Paris

Georges Couthon: Puy-de-Dôme

Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles: Seine-et-Oise

Robert Lindet: Eure

Pierre-Louis Prieur de la Marne: Marne (hence the name…)

Claude-Antoine Prieur: Côte-d'Or (ditto)

Maximilien Robespierre: Paris

André Jeanbon Saint-André: Lot

Louis Antoine de Saint-Just: Aisne

PS: It’s fascinating and telling how many of them represented provinces in the north of France.

#frev#robespierre#french revolution#couthon#barere#collot#billaud varenne#herault#lazare carnot#saint just#saint-andre#Committee of Public Safety#priuer

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

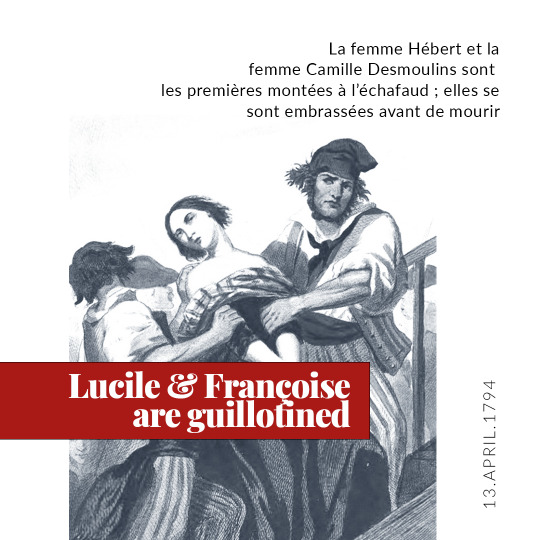

On the 13th of April 1794, exactly 230 years ago, Lucile Desmoulins and Francoise Hebert met their tragic end, following their husbands to the guillotine after enduring a brief, sham trial that wrongfully convicted them of conspiracy. Though widowed by leaders of ideologically opposed factions (Hebert was an extremist, while Desmoulins was a so-called indulgent), the two women forged a strong bond in prison. Their final moments were marked by a brief embrace before they faced their execution with dignity.

The execution of Lucile Desmoulins:

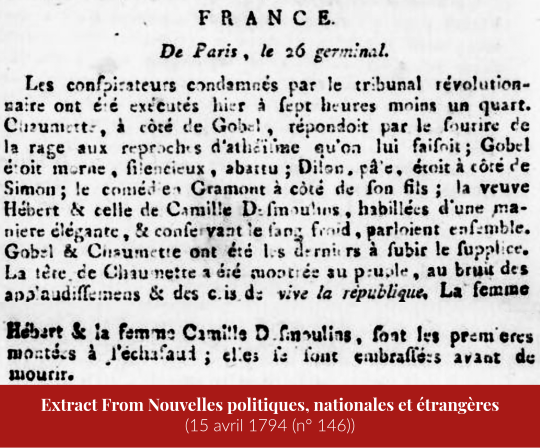

FRANCE.

From Paris, the 26th of Germinal.

The conspirators condemned by the revolutionary tribunal were executed yesterday at a quarter to seven. Chaumette, next to Gobel, responded to the accusations of atheism made against him with a rageful smile; Gobel was morose, silent, dejected; Dillon, cheerful, was beside Simon; the Count of Grammont next to his son; the widow Hébert and that of Camille Desmoulins, dressed elegantly and maintaining their composure, were talking together. Gobel & Chaumette were the last to endure the punishment. Chaumette's head was carried to the people amidst applause and cries of "Long live the republic." The wife of Hébert and the wife of Camille Desmoulins were the first to go up to the scaffold; they embraced before dying.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The unfortunate Camille, hearing the name of his wife being pronounced, cried out in pain and said: ”The scoundrels, not content with murdering me, they also want to murder my wife!”

Camille Desmoulins on the third day of his trial (April 4 1794) upon hearing that his wife had been accused of taking part in a new conspiracy, as reported by the witness Paris, registrar at the Revolutionary Trubunal, during the trial of public procecutor Fouquier-Tinville. Cited in Historie Parlamentaire de la Révolution Française ou Journal des Assemblées Nationales, depuis 1789 jusqu’en 1815 (1837) page 472.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

@revolutionarywig the one in 2022, right?

I think the video you're referencing in the exhibit is this one:

youtube

When I'm having a crappy day at work, I sometimes visit "L'Ami du Peuple" during my lunch break. It tends to put all the petty day-to-day stuff into perspective…

During the quieter moments, like today, when room 55 is nearly empty, I can't help but notice a pattern. Every single visitor, upon entering, pauses before the painting.

They do a double-take at the painting's name and give him another look. Some snap a photo they'll probably never look at again.

Then they move on.

Most of them likely have no clue who he is. They don't know he's holding a note from his assassin. If they even notice "L'An Deux" written at the bottom, they're probably confused by it.

But still, for those 30 seconds, David's brushstrokes that bring to life the exquisite face of this stricken man make them pause. What makes them linger? Is it the vaguely familiar name? The face they've seen on numerous posters and leaflets? The unsettling quiet brutality of the piece?

It doesn’t really matter why. Because, for that half-minute, through their eyes, he exists. He is present. He is contemporary.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

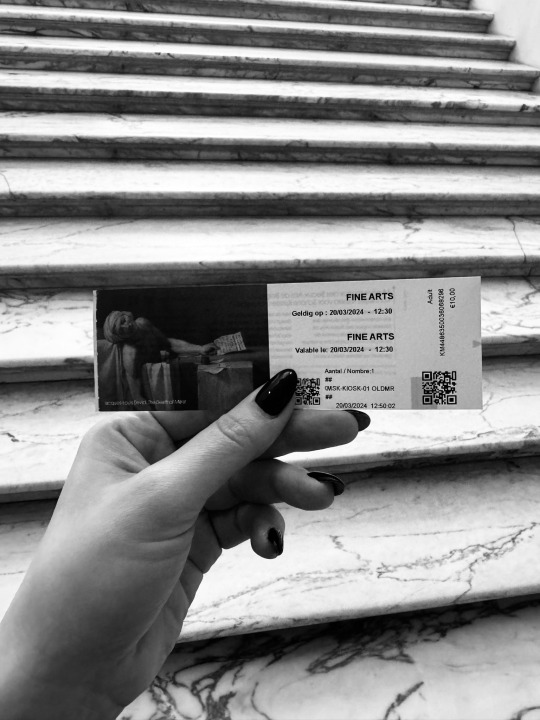

He does have a whole wall to himself, but the room is filled with other paintings from David and the French school. Across from him they have David’s last work (Mars Being Disarmed by Venus) which is huge and completely different in style and composition.

I think why he seems so “lonely” is because the painting is quite small compared to other things in the room.

As to the museum being afraid of offering people’s “sensibilities”, I’m not sure that’s the case. They use it in a lot of promotional material. They also have the painting in the rooster of images they print on the tickets randomly. Yesterday I actually happened to get it.

When I'm having a crappy day at work, I sometimes visit "L'Ami du Peuple" during my lunch break. It tends to put all the petty day-to-day stuff into perspective…

During the quieter moments, like today, when room 55 is nearly empty, I can't help but notice a pattern. Every single visitor, upon entering, pauses before the painting.

They do a double-take at the painting's name and give him another look. Some snap a photo they'll probably never look at again.

Then they move on.

Most of them likely have no clue who he is. They don't know he's holding a note from his assassin. If they even notice "L'An Deux" written at the bottom, they're probably confused by it.

But still, for those 30 seconds, David's brushstrokes that bring to life the exquisite face of this stricken man make them pause. What makes them linger? Is it the vaguely familiar name? The face they've seen on numerous posters and leaflets? The unsettling quiet brutality of the piece?

It doesn’t really matter why. Because, for that half-minute, through their eyes, he exists. He is present. He is contemporary.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I'm having a crappy day at work, I sometimes visit "L'Ami du Peuple" during my lunch break. It tends to put all the petty day-to-day stuff into perspective…

During the quieter moments, like today, when room 55 is nearly empty, I can't help but notice a pattern. Every single visitor, upon entering, pauses before the painting.

They do a double-take at the painting's name and give him another look. Some snap a photo they'll probably never look at again.

Then they move on.

Most of them likely have no clue who he is. They don't know he's holding a note from his assassin. If they even notice "L'An Deux" written at the bottom, they're probably confused by it.

But still, for those 30 seconds, David's brushstrokes exquisitely forming the face of this stricken man make them pause. What makes them linger? Is it the vaguely familiar name? The face they've seen on numerous posters and leaflets? The unsettling quiet brutality of the piece?

It doesn’t really matter why. Because, for that half-minute, through their eyes, he exists. He is present. He is contemporary.

#pseudo-philosophical ramblings#frev#french revolution#marat#jean paul marat#l'ami du people#jacques louis david#my happy place is a picture of a 18th century dead guy#personal opinion

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other day, whilst perusing the Louvre's collection, as one occasionally does, in search of 18th-century artefacts, I chanced upon a delightful set of six glasses dating back to the late 1700s (https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010381445). Of course they caught my eye since I love silhouettes as an art form...

So, behaving as any sensible individual might, I felt a sudden urge to acquire some for myself. Given that I can't exactly march into the Louvre and demand they hand over their glasses, and finding myself in urgent need of a weekend project, I decided to craft my own. And, well… one "brilliant" idea gave way to another, leading to… a ridiculous number of botched attempts, culminating in the creation of my new Robespierre mug ☕️💖

(the man was reputed to subsist almost entirely on coffee... so of course I made a mug...)

Now I want to make one for each member of the 3rd CPS and have them have coffee parties ...

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

I understand the story of marat and his assassination event

But who is lepeletier?

Because I saw a drawing for him by louis David and I learned about his death which happen to be the same as Marat so yeah .. I wanna know about him.

According to the biography Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), its subject of study was born on 29 May 1760, in his family home on rue Culture-Sainte-Catherine, a building which today is the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. His family belonged to the distinguished part of the robe nobility. At the death of his father in 1769, Lepeletier was both Count of Saint-Fargeau, Marquis of Montjeu, Baron of Peneuze, Grand Bailiff of Gien as well as the owner of 400,000 livres de rente. For five years he worked as avocat du roi at Châtelet, before becoming councilor in Parliament in 1783, general counsel in 1784 and finally taking over the prestigious position of président à mortier at the Parlement of Paris from his father in 1785. On May 16 1789, Lepeletier was elected to represent the nobility at the Estates General. On June 25 the same year he was one of the 47 nobles to join the newly declared National Assembly, two days before the king called on the rest of the first two estates to do so as well. A month later, during the night of August 4 1789, he was in the forefront of those who proposed the suppression of feudalism, even if, for his part, this meant losing 80 000 livres de rente. Four days later he wrote a letter to the priest of Saint-Fargeau, renouncing his rights to both mills, furnaces, dovecote, exclusive hunting and fishing, insence and holy water, butchery and haulage (the last four things the Assembly hadn’t ruled on yet). When the Assembly on June 19 1790 abolished titles, orders, and other privileges of the hereditary nobility, Lepeletier made the motion that all citizens could only bear their real family name — ”The tree of aristocracy still has a branch that you forgot to cut..., I want to talk about these usurper names, this right that the nobles have arrogated to themselves exclusively to call themselves by the name of the place where they were lords. I propose that every individual must bear his last name and consequently I sign my motion: Michel Lepeletier” — and the same year he also, in the name of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, presented a report on the supression of the penal code and argued for the abolition of the death penalty. After the closing of the National Assembly in 1791, Lepeletier settled in Auxerre to take on the functions of president of the directory of Yonne, a position to which he had been nominated the previous year. He did however soon thereafter return to Paris, as he, following the overthrow of the monarchy, was one of few former nobles elected to the National Convention, where he was also one of even fewer former nobles to sit together with the Mountain. In December 1792 he started working on a public education plan. On January 20 1793, he voted for death without a reprieve and against an appeal to the people during the trial of Louis XVI (Opinion de L.M. Lepeletier, sur le jugement de Louis XVI, ci-devant roi des François: imprimée par ordre de la Convention nationale). After the session was over, Lepeletier went over to Palais-Égalité (former Palais-Royal) where he dined everyday. The next day, his friend and fellow deputy Nicolas Maure could report the following to the Convention:

Citizens, it is with the deepest affection and resentment of my heart that I announce to you the assassination of a representative of the people, of my dear colleague and friend Lepelletier, deputy of Yonne; committed by an infamous royalist, yesterday, at five o'clock, at the restaurateur Fevrier, in the Jardin de l'Égalité. This good citizen was accustomed to dining there (and often, after our work, we enjoyed a gentle and friendly conversation there) by a very unfortunate fate, I did not find myself there; for perhaps I could have saved his life, or shared his fate. Barely had he started his dinner when six individuals, coming out of a neighboring room, presented themselves to him. One of them, said to be Pâris, a former bodyguard, said to the others: There's that rascal Lepeletier. He answered him, with his usual gentleness: I am Lepeletier, but I am not a rascal. Paris replied: Scoundrel, did you not vote for the death of the king? Lepelletier replied: That is true, because my confidence commanded me to do so.Instantly, the assassin pulled a saber, called a lighter, from under his coat and plunged it furiously into his left side, his lower abdomen; it created a wound four inches deep and four fingers wide. The assassin escaped with the help of his accomplices. Lepeletier still had the gentleness to forgive him, to pray that no further action would be taken; his strength allowed him to make his declaration to the public officer, and to sign it. He was placed in the hands of the surgeons who took him to his brother, at Place Vendôme. I went there immediately, led by my tender friendship, and my reverence for the virtues which he practiced without ostentation: I found him on his death bed, unconscious. When he showed me his wound, he uttered only these two words: I'm cold. He died this morning, at half past one, saying that he was happy to shed his blood for the homeland; that he hoped that the sacrifice of his life would consolidate Liberty; that he died satisfied with having fulfilled his oaths.

This was the first time a Convention deputy had gotten murdered, and it naturally caused strong reactions. Already the same session when Maure had announced Lepeletier’s death, the Convention ordered the following:

There are grounds for indictment against Pâris, former king's guard, accused of the assassination of the person of Michel Lepelletier, one of the representatives of the French people, committed yesterday.

[The Convention] instructs the Provisional Executive Council to prosecute and punish the culprit and his accomplices by the most prompt measures, and to without delay hand over to its committee of decrees the copies of the minutes from the justice of the peace and the other acts containing information relating to this attack.

The Decrees and Legislation Committees will present, in tomorrow's session, the drafting of the indictment.

An address will be written to the French people, which will be sent to the 84 departments and the armies, by extraordinary couriers, to inform them of the crime against the Nation which has just been committed against the person of Michel Lepelletier, of the measures that the National Convention has taken for the punishment for this attack, to invite the citizens to peace and tranquility, and the constituted authorities to the most exact surveillance.

The entire National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepelletier, assassinated for having voted for the death of the tyrant.

The honors of the French Pantheon are awarded to Michel Lepelletier, and his body will be placed there.

The president is responsible for writing, on behalf of the National Convention, to the department of Yonne, and to the family of Lepelletier.

The next day, January 22, further instructions were given regarding Lepeletier’s funeral:

On Thursday January 24, Year 2 of the Republic, at eight o'clock in the morning, will be celebrated, at the expense of the Nation, the funeral of Michel Lepeletier, deputy of the department of Yonne to the National Convention.

The National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepeletier in its entirety. The executive council, the administrative and judicial bodies will attend it as well.

The executive council and the department of Paris will consult with the Committee of Public Instruction regarding the details of the funeral ceremony.

The last words spoken by Michel Lepeletier will be engraved on his tomb, they are as follows: “I am happy to shed my blood for the homeland; I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality; and to make their enemies recognized.”

In number 27 (January 27 1793) of Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, the following long description was given over Lepeletier’s funeral, held three days earlier:

The funeral of Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau was celebrated on Thursday 24 with all the splendor that the severity of the weather and the season allowed, but with such a crowd that it could have been the most beautiful day of the year. At ten o'clock in the morning his deathbed was placed on the pedestal where the equestrian statue of Louis XVI previously stood, on Place Vendôme, today Place des Piques. One went up to the pedestal by two staircases, on the banisters of which were antique candelabras. The body was lying on the bed with the bloody sheets and the sword with which he had been struck. He was naked to the waist, and his large and deep wound could be seen exposed. These were the mournful and most endearing part of this great spectacle. All that was missing was the author of the crime, chained, and beginning his torture by witnessing the sight of the triumph of Saint-Fargeau.

As soon as the National Convention and all the bodies that were to form courage were assembled in the square, mournful music was played. It was, like almost all those which has embellished our revolutionary festivals, the composition of citizen Gossec. The Convention was ranged around the pedestal. The citizen in charge of the ceremonies presented the President of the Convention with a wreath of oak and flowers; then the president, preceded by the ushers of the Convention and the national music, went around the monument, and went up to the pedestal to place the civic crown on Lepeletier's head: during this time, a federate gave a speech; the president dismounted, the procession set out in the following order: A detachment of cavalry preceded by trumpets with fourdincs. Sappers. Cannoneers without cannons. Detachment of veiled drummers. Declaration of the rights of man carried by citizens. Volunteers of the six legions, and 24 flags. Drum detachment. A banner on which was written the decree of the Convention which ordered the transport of Lepeletier's body to the Pantheon. Students of the homeland. Police commissioners. The conciliation office. Justices of the peace. Section presidents and commissioners. The commercial court. The provisional criminal court. The department’s fix courts. The electorate. The provisional criminal court. The department's criminal courts fix. The municipality of Paris. The districts of Saint-Denis and the village of L’Égalité. The Department. Drum detachment. The seal of the 84, worn by Federates. The provisional executive council. National Convention Guard Detachment. The court of cassation. Figure of Liberty carried by citizens. The bloody clothes worn at the end of a national pike, deputies marching in two columns. In the middle of the deputies was a banner where Lepeletier's last words were written: "I am happy to shed my blood for my homeland, I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality, and to make their enemies known.”

The body carried by citizens, as it was exhibited on the Place des Piques. Around the body, gunners, sabers in hand, accompanied by an equal number of Veterans. Music from the National Guard, who performed funeral tunes during the march. Family of the dead. Group of mothers with children. Detachment of the Convention Guard. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Armed federations. Popular societies. Cavalry and trumpets with fourdines. On each side, citizens, armed with pikes, formed a barrier and supported the columns. These citizens held their pikes horizontally, at hip height, from hand to hand. The procession left in this order from the Place des Piques, and passed through the streets St-Honoré, du Roule, the Pont-Neuf, the streets Thionville (former Dauphine), Fossés Saint-Germain, Liberté (former Fossés M. le Prince), Place Saint-Michel and Rue d'Enfer, Saint-Thomas, Saint-Jacques and Place du Panthéon. It stopped front of the meeting room of the Friends of Liberty and Equality; opposite the Oratory, on the Pont-Neuf, opposite the Samaritaine; in front of the meeting room of the Friends of the Rights of Man; at the intersection of Rue de la Liberté; Place Saint-Michel and the Pantheon. Arriving at the Pantheon, the body was placed on the platform prepared for it. The National Convention lined up around it; the band, placed in the rostrum, performed a superb religious choir; Lepeletier's brother then gave a speech, in which he announced that his brother had left a work, almost completed, on national education, which will soon be made public; he ended with these words: I vote, like my brother, for the death of tyrants. The representatives of the people, brought closer to the body, promised each other union, and swore on the salvation of the homeland. A big chorus to Liberty ended the ceremony.

According to Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), civic festivals in honor of Lepeletier were celebrated in all sections of Paris, as well as the towns of Arras, Toulouse, Chaumont, Valenciennes, Dijon, Abbeville and Huningue. Lepeletier’s body did however only get to rest in the Panthéon for a little more than a year, as on February 15 1795, the Convention ordered it exhumed, at the same time as that of Marat. It was instead buried in the park surrounding Château de Ménilmontant, the properly of which the ancestor Lepeletier de Souzy had purchased in the 17th century and that still remained in the family.

One day after the funeral, January 25, Lepeletier’s only child, the ten and a half year old Susanne, who had already lost her mother ten years before the murder of her father, was brought before the Convention by her step-mother and two paternal uncles Amédée and Félix. It was Félix who had held a speech during the funeral and he would continue to work for his seven years older brother’s memory afterwards too, offering a bust of him to the Convention on February 21 1793, (on the proposal of David, it was placed next to the one of Brutus), reading his posthumous work on public education to the Jacobins on July 19 1793, and even writing a whole biography over his life in 1794 (Vie de Michel Lepeletier, représentant du peuple français, assassiné à Paris le 20 janvier 1793 : faite et présentée a la Société des Jacobins).

The president announces that the widow of Michel Lepelletier, his two brothers and his daughter, request to be admitted to the bar, to testify to the Convention their recognition of the honors that they have decreed in memory of their relative. It is decreed that they will be admitted immediately.

One of Michel Lepeletier’s brothers: Citizens, allow me to introduce my niece, the daughter of Michel Lepelletier; she comes to offer you and the French people her recognition of the eternity of glory to which you have dedicated her father... He takes the young citoyenne Lepelletier in his arms, and makes her look at the president of the Convention... My niece, this is now your father... Then, addressing the members of the Convention, and the citizens present at the session: People, here is your child... Lepelletier pronounces these last words in an altered voice: silence reigns throughout the room, with exception for a couple of sobs.

The President: Citizens, the martyr of Liberty has received the just tribute of tears owed to him by the National Convention, and the just honor that his cold skin has received invites us to imitate his example and to avenge his death. But the name of Lepelletier, immortal from now on, will be dear to the French Nation. The National Convention, which needs to be consoled, finds relief to its pain in expressing to his family the just regrets of its members and the recognition of the great Nation of which it is the organ. The Nation will undoubtedly ratify the adoption of Michel Lepelletier's daughter that is currently being carried out by the National Convention.

Barère: The emotion that the sight of Michel Lepeletier's only daughter has just communicated to your souls must not be infertile for the homeland. Susanne Lepelletier lost her father; she must find now find one in the French people. Its representatives must consecrate this moment of all-too-just felicity to a law that can bring happiness to several citizens and hope to several families. The errors of nature, the illusions of paternity, the stability of morals, have long demanded this beautiful institution of the Romans. What more touching time could present itself at the National Convention to pass into French legislation the principle of adoption, than that when the last crimes of expiring tyranny deprived the homeland of one of its ardent defenders and Susanne Lepelletier of a dear father! Let the National Convention therefore give today the first example of adoption by decreeing it for the only offspring of Lepelletier; let it instruct the Legislation Committee to immediately present the bill on this interesting subject. I ask that the homeland adopt through your organ Susanne Lepelletier, daughter of Michel Lepelletier, who died for his country; that it decrees that adoption will be part of French legislation, and instructs its Legislation Committee to immediately present the draft decree on adoption.

This proposal is unanimously approved.

Susanne being adopted by the state would however lead to a fierce debate when, in 1797, this ”daughter of the nation” wished to marry a foreigner. For this affair, see the article Adopted Daughter of the French People: Suzanne Lepeletier and Her Father, the National Assembly (1999)

Right after Barère’s intervention, David took to the rostrum:

David: Still filled with the pain that we felt, while attending the funeral procession with which we honored the inanimate remains of our colleagues, I ask that a marble monument be made, which transmits to posterity the figure of Lepelletier , as you clearly saw, when it was brought to the Pantheon. I ask that this work be put into competition.

Saint-André: I ask that this figure be placed on the pedestal which is in the middle of Place Vendôme... (A few murmurs arise)

Jullien: I ask that the Convention adopt in advance, in the name of the homeland, the children of the defenders of Liberty, who, for similar reasons, could be immolated in the vengeance of the royalists.

All these proposals are referred to the Legislation and Public Instruction Committees.

On Maure's proposal, the Assembly orders the printing of the speeches delivered yesterday at the Panthéon, by one of Michel Lepelletier's brothers, Barère and Vergniaux.

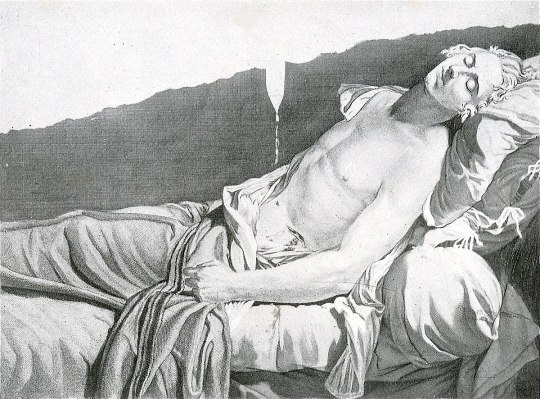

If it would appear David never got to make a marble monument of Lepeletier, on March 28 1793, he could nevertheless present the following painting of his to the Convention, which isn’t just a little similar to his La Mort de Marat.

(This image is an engraving of the actual painting, which has gone missing)

After Marat on July 13 1793 (on the very same day the plan for public education Lepeletier had been working on was read to the Convention by Robespierre) became the second assassinated Convention deputy, we find several engravings etc, depicting the two ”martyrs of liberty” side by side.

In the following months, even more people would be join the two, such as Joseph Chalier, a lyonnais politician executed on July 17 1794 and Joseph Bara, a fourteen year old republican drummer boy killed in the Vendée by the pro-Monarchist forces.

Lepeletier’s murderer, 27 year old Philippe Nicolas Marie de Pâris, a man who the minister of justice described as "former king's guard, height five pieds, five pouces, barbe bleue, and black hair; swarthy complexion, fine teeth, dressed in a gray cloak, green lapels and a round hat” on January 21, went into hiding right after his deed. In spite of his description being published in the papers and a considerable sum of money being promised to whoever caught him, Pâris managed to flee Paris and settled for a country house of an acquaintance near Bourget. He there ran into a cousin of one of the owners. When Pâris asked for food and a bed, he was refused and instead disappeared into the night again. In the evening of January 28 he arrived in Forges-les-Eaux and stopped at an inn, where he came under suspicion once he started cutting his bread with a dagger after which he locked himself into his room. The following morning he woke up with a start as five municipal gendarmes came bursting into his room and told him to come with them. Pâris responded that he would, but in the next second he had picked up his hidden pistol, placed it into his mouth, and pulled the trigger. Searching the dead body, the gendarmes found Pâris’ baptism record (dated November 12 1765) and dismissal from the king's guard (dated June 1 1792), on the latter of which had been written the following:

My certificate of honor. Do not trouble anyone. No one was my accomplice in the fortunate death of the scoundrel de Saint-Fargeau. Had I not run into him, I would have carried out a more beautiful action: I would have purged France of the patricide, regicide and parricide d’Orléans. The French are cowards to whom I say:

Peuple dont les forfaits jettent partout l'effroi, Avec calme et plaisir j'abandonne la vie.

Ce n'est que par la mort qu'on peut fuir l'infamie Qu'imprime sur nos fronts le sang de notre roi.

Signed by Paris the older, guard of the king, assassinated by the French.

Learning about what had happened, the Convention tasked Tallien and Legrand with going to … and making sure the dead man really was Pânis. Having come to the conclusion that this was indeed the case, the deputies briefly discussed whether the body ought to be brought back to Paris, but it was decided it would be better if it was just buried "with ignominy.” It was therefore instead just taken into the nearby forest in a wheelbarrow and thrown into a six feet deep hole.

Finally, here are some other revolutionaries simping for honoring Lepeletier’s memory just because I can:

…a tragic event took place the day before the execution [of the king]. Pelletier, one of the most patriotic deputies, and who had voted for death, was assassinated. A king's guard made a wound three fingers wide with a saber: he died this morning. You must judge the effect that such a crime has had on the friends of liberty. Pelletier had an income of six hundred thousand livres; he had been président à mortier in the Parliament of Paris; he was barely thirty years old; to many talents, he added the most estimable of virtues. He died happy, he took to his grave the idea, consoling for a patriot, that his death would serve the public good. Here then is one of these beings whom the infamous cabal who, in the Convention, wanted to save Louis and bring back slavery, designated to the departments as a Maratist, a factious, a disorganizer... But the reign of these political rascals is finished. You will see the measures that the Assembly took both to avenge the national majesty and to pay homage to a generous martyr of liberty.

Philippe Lebas in a letter to his father, January 21 1793

Ah! if it is true that man does not die entirely and that the noblest part of himself survives beyond the grave and is still interested in the things of life, come then, dear and sacred shadow, sometimes to hover above the Senate of the nation that you adorned with your virtues; come and contemplate your work, come and see your united brothers contributing to the happiness of the homeland, to the happiness of humanity.

Marat in number 105 (January 23 1793) of Journal de la République Française

O Lepeletier! Your death will serve the Republic: I envy your death. You ask for the honors of the Pantheon for him, but he has already collected the prize of martyrdom of Liberty. The way to honor his memory is to swear that we will not leave each other without having given a constitution to the Republic.

Danton at the Convention, January 21 1793

O Le Peletier, tu étais digne de mourir pour la patrie sous les coups de ses assassins ! Ombre chère et sacrée, reçois nos vœux et nos serments ! Généreux citoyen, incorruptible ami de la vérité, nous jurons par tes vertus, nous jurons par ton trépas funeste et glorieux de défendre contre toi la sainte cause dont tu fus l'apôtre; nous jurons une guerre éternelle au crime dont tu fus l'éternel ennemi, à la tyrannie et à la trahison, dont tu fut la victime. Nous envions ta mort et nous saurons imiter ta vie. Elles resteront à jamais gravées dans nos cœurs, ces dernières paroles où lu nous montrais ton âme tout entière; ”Que ma mort, disais tu, sera utile à la patrie, qu'elle serve à faire connaître les vrais et les faux amis de la liberté, et je meurs content.

Robespierre at the Jacobins, January 23

Wednesday 23 [sic] — We went to Madame Boyer’s to see the procession. I saw the poor Saint-Fargeau. We all burst into tears when the body passed by, we threw a wreath on it. After the ceremony, we returned to my house. Ricord and Forestier had arrived. I was unable to stop my tears for some time. F(réron), La P(oype), Po, R(obert) and others came to dinner. The dinner was quite fun and cheerful. Afterwards they went to the Jacobins, Maman and I stayed by the fire and, our imaginations struck by what we had seen, we talked about it for a while. She wanted to leave, I felt that I could not be alone and bear the horrible thoughts that were going to besiege me. I ran to D(anton’s). He was moved to see me still pale and defeated. We drank tea, I supped there.

Lucile Desmoulins in her diary, January 24 1793

…Pelletier's funeral took place this Thursday as I informed you in my last letter (this letter has gone missing). The procession was immense; it seemed that the population of Paris had doubled, to honor the memory of this virtuous citizen. The mourning of the soul was painted on all the faces: it was especially noticed that the people were extremely affected, which proves that they keenly felt the price of the friend they had lost. Arriving at the Pantheon, Lepelletier's body was placed on the platform prepared for it; his brother delivered a speech which was applauded with tears; Barère succeeded him. Then the members of the Convention, crowding around the body of their colleague, promised union among themselves, and took an oath to save the country. God grant that we have not sworn in vain, that we finally know the full extent of our duties, and that we only occupy ourselves with fulfilling them! In yesterday's session, Pelletier's daughter, aged eight [sic], was presented to the National Convention, which immediately adopted her as a child of the homeland.

Georges Couthon in a letter written January 26 1793

How could I be so base as to abandon myself to criminal connections, I who, in the world, have never had more than one close friend since the age of six? (he gestures towards David's painting). Here he is! Michel Lepeletier, oh you from whom I have never parted, you whose virtue was my model, you who like me was the target of parliamentary hatred, happy martyr! I envy your glory. I, like you, will rush for my country in the face of liberticidal daggers; but did I have to be assassinated by the dagger of a republican!

Hérault de Sechelles at the Convention, December 29 1793

For a collection of Lepeletier’s works, see Oeuvres de Michel Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau, député aux assemblées constituante et conventionnelle, assassiné le 20 janvier 1793, par Paris, garde du roi (1826)

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a theory that part of the way Charlotte presents herself in her memories as meek is because she does so to Laponneraye who is known to be of a rather … regressive … persuasion as far as female participation in politics is concerned…

more on jamgate?

i read charlotte’s memoirs years ago but i dont remember the details

Sorry for my late reply! I love to call it "The Great Jamgate of 1793", but in truth I am unsure when it happened. Does anyone know when Charlotte persuaded Robespierre to come live with her, but then he got sick and Mme Duplay brought him back to Duplays? The jamgate happens after that. (So it could be the Great Jamgate of 1791 or 1792, lol).

Charlotte tells us how she loved making jams for her brother, who had a taste for sweets and fruits. She would send her maid to Duplays to deliver jams, and, according to Charlotte, Mme Duplay always had a snarky comment on that.

The worst happend one time when Mme Duplay sent the maid back, refusing to accept jams, saying something along the lines of "Bring that back, I don't want her to poison Robespierre".

Naturally and understandably, Charlotte was shocked and hurt. It was inded a shitty thing to say, even as a "joke". In line with the narrative Charlotte built about herself in the memoirs, she claims that she "swallowed her sadness" and said nothing to Mme Duplay or Maximilien (as to not cause him pain).

Of course, we have to remember that this is Charlotte's version of the story (we don't have one from Duplays), and Charlotte is not always the most reliable of the narrators. Still, the anecdote seems too specific to just be made up, so I am willing to believe that there was indeed a Great Jamgate of some sorts. We do know that Mme Duplay didn't like Charlotte much, and it's possible that she ridiculed her cooking skills. (Those two women seemed to fight over who would pamper Maximilien). Mme Duplay obviously saw herself as superior, and tbh, she probably was, but I doubt that she really thought that Charlotte wanted to bring harm to her brother (?)

Still, I can see Mme Duplay saying something snarky about Charlotte's cooking. But I can't guess anything more than that.

The way Charlotte described the Jemgate, it has all the typical story points of her narrative: there is always a harpy woman who hates her and tries to take her away from her brothers. The harpy is horrible, but she (Charlotte) never says anything because she is good and non-confrontational, and she doesn't want to hurt her brothers or cause any problems.

Needless to say, this goes against everything that we know of her character from other sources. Charlotte comes off as too outspoken and stubborn for this meek and obedient image she paints of herself, not to mention that she did get into fights with her brothers.

So it's difficult for me to trust her version of the Jamgate, even though I do believe that there was a Jamgate in some form. In my opinion, it reflected the two women's fight over pampering Robespierre - a fight he seemed to ignore (probably as a woman's thing, as if it wasn't happening because of him). As a sister to an unmarried man, Charlotte absolutely had all the rights to be the one to care for Robespierre and his household - it was an important duty that an unmarried sister would do for her brother. In that sense, Duplays overstepped the social boundaries, even if Charlotte was indeed bad at household duties (my theory is that she was too busy with the revolution but I don't have a concrete proof, except my wishful thinking).

Still, it was Robespierre's fault for not saying anything, and for not recognizing the social mistake of the situation. I believe he really felt pampered and cared for at Duplays in a way Charlotte could not provide (if anything, she was one person and Duplays had 4 women ready to pamper him). A different sister might not have cared, but Charlotte was obviously feeling rejected. Couple this with the Northerner vs Paris anymosity and you have a recipe for disaster. Robespierre not solving the situation is not surprising, given his character (I wonder if he noticed anything/knew/understood what's going on), but it's not an excuse, because it was on him to mediate between Charlotte and Mme Duplay, since the whole mess was about him.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis-Antoine Saint-Just: the Beginning

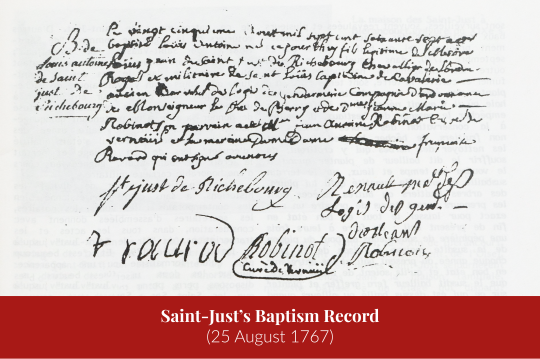

On the day of his birth, 25th of August 1767, Louis-Antoine was baptized by his maternal uncle ( priest Edmond-Léonard Robinot) in the church of Saint-Aré in Decize.

Located between Nevers and Moulins, the small town of Decize then had forges, a plaster factory, coal mines, and warehouses where Burgundy wines were stored. Louis Antoine was probably born in the house of his maternal grandfather, Léonard Robinot, on the Quai du Pont-de-Loire, at the corner of Rue des Pêcheurs. There is a whole family drama about his parents' marriage and his grandfather being against it, but that's a story for another time!

His godparents were his second uncle, Antoine Robinot and Françoise Ravard the wife of a lawyer in the Parlement. He was named Louis after his father and Antoine after his godfather.

The baptismal font is in the archive of the church of Saint-Aré. We can't be sure, but since it's a 18th century font it might have been used for the baptism of baby Saint Just...

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demon Zozo from a 1968 Café Procope postcard

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

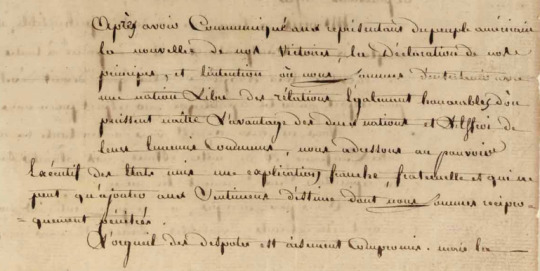

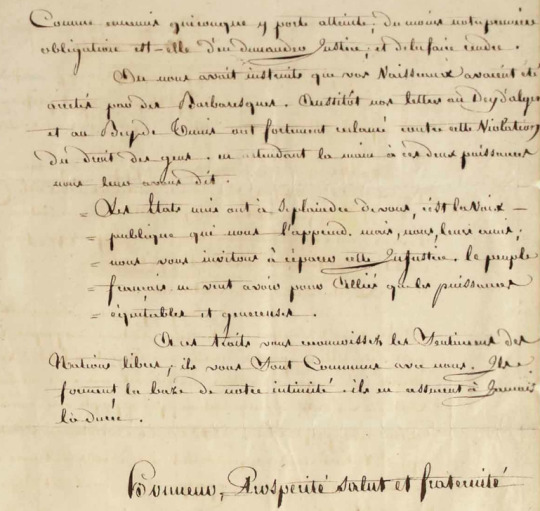

Letter of state signed (“Robespierre”) TO GEORGES WASHINGTON, “President du Congrès des Etats Unis de Amerique,” on behalf of “les représentants du Peuple Français, Membres du Comité de Salut public,” also signed by Lazare Carnot (1753-1823), C.-A. Prieur, Bertrand Barère (1755-1841), Jean-Marie Collot d’Herbois (1750-1796), Jacques Billaud Varennes (1756-1819), J.-B. Robert Lindet (1746-1825), Georges Couthon (1755-1794), and Jeanbon Saint André of the Comité de Salut Public, Paris, 22 pluvoise an 2 [10-11 February 1794].

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maximilien Robespierre lived in Arras and yet he never saw the sea. The sea is only 100 kilometres away from Arras...

Whenever I don’t understand something about the period, whenever I feel I am prone to holding the actions of 18th-century men to the standard of 21st-century morals, I remind myself that a journey we now make in an hour would have taken him ten.

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

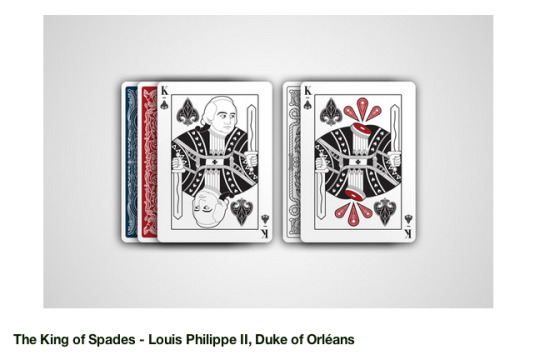

Is the kickstarter owner called Évariste Gamelin ?

Something interesting I just stumbled across– a kickstarter for a French Revolution playing card deck. Here’s the link.

79 notes

·

View notes

Note

I totally agree with this...

I think anyone reading The Twelve Who Ruled needs to remember that it was published in 1941, so it's quite dated. Palmer didn't have the benefit of the body of modern research have today.

Palmer also manages to be fairly sympathetic to the men on the Committee of Public Safety. He's pretty balanced in his views. That being said, he pretty much doesn't quote anything... so yeah...

That being said, it's extremely fun to read and Palmer has excellent storytelling skills.

Entirely impromptu question, but have you read Palmer's Twelve Who Ruled? If so, would you recommend it at all?

I have! Did not re-read it in a while, so my opinion might not be relevant.

It is an okay-ish introduction to the CSP for an English book. By this, I mean that there are so few not utterly demonizing English books on the topic, so you take what you can get if you don't speak French. It is also a quick and, as I recall, fun read. So I would say it's fine to use it.

That being said, I remember not being impressed as to how it presents the CSP people I know the best (so I assume it might be the same for others?) By it, I mean that there are some stereotypes and some things that appear with what I call "trust me, bro" source (= you have no idea where he got that). It's also more "the 9 who ruled, plus three we don't have much to say about", as I recall. So it's not a perfect book, and it does build some stereotypes, but not utterly rubbish. It's not a bad introduction (at least makes you differentiate between 9, if not all 12), but one should not take it as the absolute truth on the matter.

Anyone? What would you say about the Twelve Who Ruled?

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint-Just Hyping up Robespierre's Speech

Saint-Just, ordinarily rather reserved at the Jacobin Club, made an exception on January 1, 1793. Despite presiding over the session, he didn't share personal views or push his own agenda. Instead, he invited his colleagues to fund the printing and nationwide distribution of Robespierre's second speech on Louis XVI's trial (delivered on December 28, 1792)

His address was probably delivered in a a rather matter-of-fact and perfunctory tone. That being said, in my head, he's going full movie villain on the jacobins, urging them to open their purses or face the "dire consequences from the Archangel of Terror! Mwahahaha!”

(Translation under the cut)

Translation:

Citizens, you are well aware that, to dispel the errors with which Roland has enveloped the entire Republic, the Society has resolved to print and distribute Robespierre's speech. We have regarded it as an eternal lesson for the French people (1), as a sure way to unmask the Brissotin faction and to open the eyes of the French to the virtues of the minority seated on the Mountain that have been too long unknown. I remind you that a subscription office is open at the secretariat. It is enough for me to indicate this to stimulate your patriotic zeal, and, by emulating the patriots who have each contributed fifty ecus (2) to print Robespierre's excellent speech, you will have well earned the gratitude of the nation.

Notes

(1) The gushing is adorable

(2) In today's terms, fifty ecus translates to approximately 1900 euros. This was no small amount, particularly in light of the country's economic climate at the time.

Source:

Saint-Just, Louis Antoine Léon de. Œuvres. Paris: Gallimard, 2014

120 notes

·

View notes