Austrian Crocodile Enthusiast Hobby researcher, skeletal artist and Wikipedia editor

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Paleontology fun fact

"Crocodilus robustus", here shown as the more robust animal on the left of the image, is not an extant animal as the illustration might suggest. Instead this animal is nowadays known by the name Voay and died out within the last two thousand years.

What the image also doesn't show is what Voay is arguably best known for these days, a pair of large squamosal horns that somewhat resemble ears (though they are bony structures located just above the ear flap). And if you think the one below looks funky, trust me, theres skulls with even more extreme horns.

Crocodilus madagascariensis meanwhile, our more gracile animal in the original post, is nowadays agreed to simply be a modern nile crocodile, who established a population on Madagascar. While it was at one point believed that they only moved in after the extinction of Voay, this no longer seems to be the case and the two appear to have overlapped. Fun fact, the name Crocodilus madagascariensis was actually coined twice by two different authors independent of each other. Another fun fact, some nile crocodile populations on Madagascar actually live in caves.

🐊 Histoire physique, naturelle, et politique de Madagascar Paris: Impr. nationale, 1885- Original source Image description: Detailed black and white lithographic illustration of two crocodile heads viewed from above. The left crocodile is labeled “2” and identified as Crocodilus robustus, showing a broad, textured snout with distinct scales and nostrils. The right crocodile, labeled “1” as Crocodilus madagascariensis, has a slightly narrower snout and prominent bony ridges. Both heads feature detailed skin textures with visible scales and symmetrical patterns. The print includes scientific labeling and is from an 1885 publication titled “Histoire physique, naturelle, et politique de Madagascar,” focusing on reptiles.

#croc#crocodile#voay#nile crocodile#madagascar#holocene#fossil#palaeoblr#prehistory#pseudosuchia#Crocodilia#crocodylus

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

@knuppitalism-with-ue you should show them yours

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun little thing I just stumbled across. Apparently a male gharial is also known as a ghadiala, a term derived from the protuberance on their snout (known as a ghara after a type of earthen pot)

For those unfamiliar, here's some photos of what the ghara looks like. Photographs by Shivang Mehta

#gharial#ghara#soft tissue#crocodilia#anatomy#herpetology#croc#gavialoidea#gavialis#indian gharial#etymology

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

late to the trend but I had to get it out after the idea hit me

197 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is your favorite theropod and why? 👀

Happy about any ask I get, but its very funny to me to ask the account hardly ever talking about dinosaurs about theropods lmao.

That being said, probably not much of a surprise given my primary focus, but I got a soft spot for spinosaurids. My favourite tends to go back and forth between Suchomimus and Ichthyovenator.

The reason why, I mean there are some parallels to crocodilians so obviously they'd be the dinosaur group I enjoy the most. Spinosaurus is cool too, I just prefer these less lavish genera.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

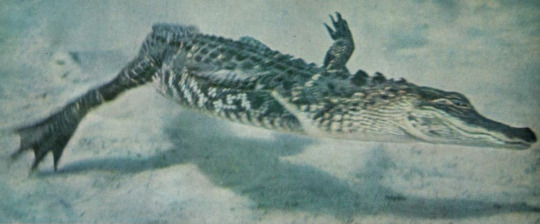

American alligator By: Shelley Grossman From: Life Nature Library: Reptiles 1963

583 notes

·

View notes

Text

More crocodile encounters

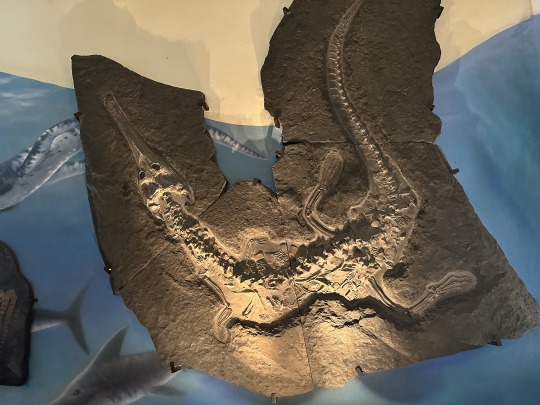

I went to Vienna again last week and this week so I have more crocodile photos unrelated to the ones I shared in April. For starters, of course theres the Morelets Crocodiles at the zoo, which were surprisingly cooperative in their activity.

Only a few days ago meanwhile, I went to the Natural History Museum to get a look at the newly refurbished reptile halls. Ultimately the objects on display changed very little, but at least some got a slight makeover. First of all the crocodile display

Secondly, the alligatoids, which had some great taxidermied Paleosuchus and Melanosuchus

And of course. The highlight of the room, the thing that draws me on every time. The pair of Indian gharials, which appear with a new coat of paint. They are impressive partially in their size, with the larger male measuring an impressive 5.3 meters long.

#Nhmw#natural history museum#natural history museum vienna#zoo vienna#Zoo schönbrunn#Gharial#crocodile#caiman#Alligator#croc#crocodilia#morelets crocodile#taxidermy

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deinosuchus: Giant Alligator or something older?

I know the title sucks, I couldn't think of anything poetic or clever ok? Anyways, still catching up on croc papers to summarize and this one did make a few waves when it was published about a week ago.

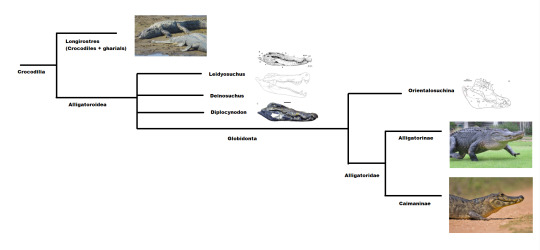

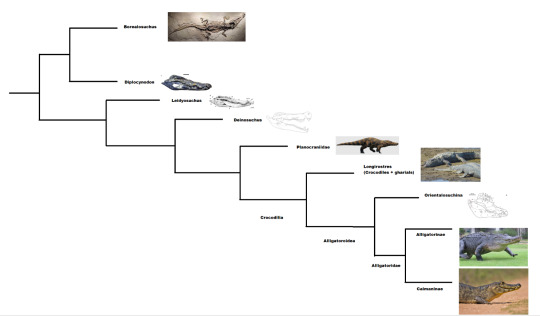

"Expanded phylogeny elucidates Deinosuchus relationships, crocodylian osmoregulation and body-size evolution" is a new paper by Walter, Massonne, Paiva, Martin, Delfino and Rabi, with quite a few of these authors having considerable experience with crocodile research. The thesis of the study is both simple and unusual. They suggest that several crocodilians traditionally held as stem-alligators, namely Deinosuchus, Leidyosuchus and Diplocynodon, weren't alligatoroids at all. In fact, if the study holds up they might not have been true crocodilians.

Ok, lets take a step back and briefly look at our main three subjects. Deinosuchus of course needs no introduction, a titan of the Cretaceous also known as the terror crocodile in some more casual sources, its easily one of the most iconic fossil crocodiles. It lived on either side of the Western Interior Seaway during the Campanian, fed on giant turtles and dinosaurs and with size estimates of up to 12 meters its easily among the largest crocodylomorphs who have ever lived.

Artwork by Brian Engh

Leidyosuchus also lived during the Campanian in North America and I would argue is iconic in its own right, albeit in a different way. It's historic to say the least and once housed a whole plethora of species, but has recently fallen on hard times in the sense that most of said species have since then been transferred to the genus Borealosuchus.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe

Finally there's Diplocynodon, the quintessential croc of Cenozoic Europe. With around a dozen species found from the Paleocene to the Miocene all across Europe, it might be one of the most well studied fossil crocs there is, even if its less well known by the public due to its relatively unimpressive size range.

Artwork by Paleocreations

All three of these have traditionally been regarded as early members of the Alligatoroidea, one of the three main branches that form Crocodilia. In these older studies, Alligatoroidea can be broken up into three groups nested within one another. Obviously the crown is formed by the two living subfamilies, Alligatorinae and Caimaninae, both of which fall into the family Alligatoridae. If you take a step further out you get to the clade Globidonta, which in addition to proper Alligatorids also includes some basal forms with blunt cheek teeth as well as Orientalosuchina, tho jury's still out on whether or not they are truly alligator-relatives. And if you take a final step back and view Alligatoroidea as a whole, then you got our three main subjects neatly lined up outside of Globidonta in varying positions.

Below a highly simplified depiction of previous phylogenies. Deinosuchus, Leidyosuchus and Diplocynodon are often regarded as non-globidontan alligatoroids.

This new study however changes that long standing concensus. The team argues that several features we once thought defined alligatoroids are actually way more common across Crocodilia and even outside of it while also leverging some of the features of Deinosuchus and co. that have always been out of the ordinary. For instance, early alligatoroids are generally characterized as being comparably small, having had short, rounded heads, the afforementioned globular cheek teeth and of course the feature that still allows us to differentiate them from true crocodiles, the fact that they have a clear overbite. Now Leidyosuchus, Deinosuchus and Diplocynodon all have proportionally longer snouts than alligatoroids, their teeth interfinger like in crocodiles and most prominently (and namegiving for Diplocynodon) there is a large notch behind the snout tip that serves to receive two enlarged teeth of the lower jaw. These are of course just superficial examples, but if you wanna get into the nitty gritty check out the paper.

Below a simplified version of the papers phylogeny. Borealosuchus clades with Diplocynodon and Leidyosuchus and Deinosuchus are successive taxa. Planocraniidae are the sister to Crocodilia, which consists of Crocodyloids, Gavialoids (together Longirostres) and Alligatoroids.

Something also worth addressing in light of these results is salt tolerance in crocodilians and paleogeography. Basically, if you ignore Deinosuchus and co. (or well, just follow this new paper), then it is most likely that alligatoroids originated on the continent of Laramidia, i.e. the western half of America back when it was bisected by an enormous inland sea. Today, alligatoroids are famously intolerant of saltwater, yes, there are instances where alligators have been known to enter coastal waters, but its a far cry from what true crocodiles can achieve (just an example here's my recent post on Caribbean crocodiles). Given that alligatoroids don't appear on Appalachia, the other half of North America, until after the inland sea closes, this very much suggest that this intolerance goes way back. This has however always been at odds with Deinosuchus, which famously showed up along both the eastern and the western coast of the inland sea and at least lived close enough to the coast to leave its mark on the shells of sea turtles. We know it inhabited various near-shore environments and even stable isotope analysis of its teeth points towards it consuming either saltwater or prey that lives in the ocean. To a lesser degree its worth mentioning Diplocynodon, which though usually a freshwater animal has at least one species from coastal deposits. Now I do think its worth highlighting that just being salt tolerant doesn't necessarily mean they can't have been alligatoroids, given that salt glands could have easily been lost after Deinosuchus split off from other alligatoroids. Nevertheless, a position as a stem-crocodilian does add up with it being salt tolerant, with the assumption being that being tolerant to saltwater is basal to crocodilians as a whole and was simply lost in a select few lineages such as alligatoroids.

Given that its range spanned both coastlines of the Western Interior Seaway as well as direct evidence for interactions with marine life, Deinosuchus likely ventured out into the sea from time to time like some modern crocodiles.

There's also the matter of timing. When alligatoroids first appeared 82 million years ago, we already see the classic blunt-snouted morphotype with Brachychampsa and our dear giant Deinosuchus. Now if both were alligatoroids, this would suggest that they've been separate quite some time before that to bring forth these drastically different forms, yet attempts to estimate the divergence date suggest that they split no earlier than 90 million years ago. So if Deinosuchus is not an alligatoroid, then the timeline adds up a bit better. However I think the best example of this new topology really explaining an evolutionary mystery doesn't come from Deinosuchus, but from Diplocynodon. Those that know me might remember that I started working on researching Diplocynodon for Wikipedia, a process that's been slow and painfull both due to the 200 years of research history and the good dozen or so species placed in this genus. Tangent aside, one big mystery around Diplocynodon is its origin. They first appear in the Paleocene and survive till the Miocene, tend to stick to freshwater and oh yeah, species of this genus are endemic to Europe. Given that previous studies recovered them as alligatoroids, nobody was quite sure where Diplocynodon came from. Did they originate in North America and cross the Atlantic? Where they salt tolerant before and simply stuck to freshwater once in Europe? Or are they a much older alligatoroid lineage that entered Europe via Asia after having crossed Beringia. You know, the kind of headbreaking stuff we get when the fossil record is incomplete. But this new study recovers Diplocynodon as being closely related to the non-crocodilian Borealosuchus from the Cretaceous to Paleogene of North America. And that makes some sense, historically the two have been noted to be similar, hell there were even cases when Borealosuchus remains were thought to be North American examples of Diplocynodon. And Borealosuchus has the same double caniniforms as the other crocs we discussed so far. So when our three former alligatoroids got pushed outside of Crocodilia, Diplocynodon ended up forming a clade with Borealosuchus. And since Borealosuchus was wide spread in America by the late Cretaceous, and possibly salt tolerant, then it could have easily spread across Greenland and Scandinavia after the impact, giving rise to Diplocynodon.

The results of this study seem to suggest that Borealosuchus and Diplocynodon are more closely related that previously thought.

And since this is a Deinosuchus paper...of course theres discussion about its size. A point raised by the authors is that previous estimates typically employ the length of the skull or lower jaw to estimate body length, which might not be ideal and is something I definitely agree with. The problem is that skull length can vary DRASTICALLY. Some animals like early alligatoroids have very short skulls, but then you have animals in gharials in which the snout is highly elongated in connection to their ecology. Given that Deinosuchus has a relatively long snout compared to early alligatoroids, size estimates based on this might very well overestimate its length, while the team argues that head width would yield a more reasonable results. Previous size estimates have ranged from as low as 8 meters to as large as 12, which generally made it the largest croc to have ever existed. Now in addition to using head width, the team furthermote made use of whats known as the phylgenetic approach, which essentially bypasses the problem of a single modern analogue with peculariar proportions influencing the result. Now there is a bunch more that went into the conclusion, but ultimately the authors conclude that in their opinion, the most likely length for the studied Deinosuchus riograndensis specimen was a mere 7.66 meters in total length. And before you jump to any conclusions, DEINOSUCHUS WOULD HAVE GOTTEN BIGGER TRUST ME. I know having read "12 meter upper estimate" earlier is quite a contrast with the resulting 7.66 meters, but keep in mind this latter estimate is just one specimen. A specimen that in previous studies was estimated to have grown to a length of somewhere between 8.4 - 9.8 meters. Now yes, this is still a downsize overall, but also given that this specimen is far from the largest Deinosuchus we have, this means that other individuals would have certainly grown larger. Maybe not those mythical 12 meters, but still very large. So please keep that in mind.

Two different interpretations of the same specimen of Deinosuchus. Top a proportionally larger-headed reconstruction by randomdinos, bottom a smaller-headed reconstruction by Fadeno. I do not care to weigh in on the debate other than to say that size tends to fluctuate a lot between studies and that I'm sure this won't be the last up or downsize we see.

Regardless of the details, this would put Deinosuchus in the "giant" size category of 7+ meters, while early alligatoroids generally fall into the small (<1.5 meters) or medium (1.5-4 meters) size categories. The authors make an interesting observation relating to gigantism in crocs at this point in the paper. Prevously, temperature and lifestyle were considered important factors in crocs obtaining such large sizes, but the team adds to that the overall nature of the available ecosystem. In the case of Deinosuchus, it inhabited enormous coastal wetlands under favorable temperature conditions and with abundant large sized prey, a perfect combination for an animal to grow to an enormous size. And this appears to be a repeated pattern that is so common its pretty much regarded as a constant. To quote the authors, "a world with enormous crocodyliforms may have been rather the norm than the exception in the last ~ 130 million years." For other examples look no further than the Miocene of South America, the extensive wetlands of Cretaceous North Africa or even Pleistocene Kenya.

One striking example for repeated gigantism in crocodilians can be found in Miocene South America, when the caimans Purussaurus and Mourasuchus both independently reached large sizes alongside the gharial Gryposcuhus. The illustration below by Joschua Knüppe features some of the smaller earlier members of these species in the Pebas Megawetlands.

So that's it then, case closed. Deinosuchus and co aren't salt-tolerant alligators, they are stem-crocodilians. Deinosuchus was smaller than previously thought and Diplocynodon diverged from Borealosuchus. Leidyosuchus is also there. It all adds up, right? Well not quite. This all is a massive upheaval from what has previously been accepted and while there were outliers before, the alligatoroid affinities of these animals were the concensus for a long time. Future studies will need to repeat the process, analyse the data and the anatomical features and replicate the results before we can be sure that this isn't just a surprisingly logical outlier. Already I heard some doubts from croc researchers, so time will tell if Deinosuchus truly was some ancient crocodilian-cousin or if previous researchers were correct in considering it a stem-alligator. I for one will keep my eyes peeled.

#pseudosuchia#crocodylomorph#eusuchia#crocodilia#crocodile#alligator#deinosuchus#leidyosuchus#diplocynodon#palaeoblr#cretaceous#fossils#prehistory#extinct#long post#science news#croc#gator#borealosuchus#evolution

164 notes

·

View notes

Note

wow!!! i found your work from ur recent tewkenosuchus writeup and its so cool!!!! you do a really good job of explaining it all without getting too specific for hobby enthusisasts to understand, but still kept it very detailed and informative!!! i loved reading it.

if you dont know of them already, try giving mothlightmedia on youtube a look! theyre another fossil enthusiast who does some lovely, very soothing videos about the evolution of different animals based on evidence and what we know of the fossil record, and i think they have some -suchus videos as well :] im really curious what you would think of them!

wishing you many intact specimens and exciting learning this year!!!!!!! have a good one :D

Thank you. The good thing with these write ups on Tumblr is that I can go more into detail than on other social media sites but I also don't have to be as formal as I have to be on Wikipedia (so while I put a lot of effort into those as well they are a lot more dry). Very glad to see that they do their job at connecting with people tho.

I have heard of mothlightmedia before, but while I appreciate the recommendation I gotta admitt that I just don't watch paleontology on youtube. It's something I am already deeply invested in, reading papers and writing about it on Wikipedia, so I am not that incentivized to seek out those videos. Nothing against them, I know paleo youtubers and people who write scripts for them, but I just watch different stuff relating to my other interests.

But I do appreciate the recommendation and kind words. Still got a few more posts I need to put together over the weekend till I'm caught up so keep an eye out.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Insular Sebecids of the Caribbean

Still catching up with posts I need to write given that the past two weeks were just major paper after major paper. Given that the last two I did were on the recently named sebecoid Tewkensuchus (more here) and on the unrecognized diversity that slumbers among modern American crocodiles (see here), it sure would be convenient if there was one that sorta ties into both of those....

Oh yeah, what convenient timing for "A South American sebecid from the Miocene of Hispaniola documents the presence of apex predators in early West Indies ecosystems", written by Lázaro W. Viñola López and colleagues and published literally just last night as of the time I'm writing this.

What's this paper about? Simple, the description of sebecid fossil remains from the island of Hispaniola. Sebecids of course being terrestrial crocodile relatives that lived throughout much of the early Cenozoic in South America. The remains admittedly aren't anything to write home about, consisting of two vertebrae and a tooth with the group's iconic blade-like serrated morphology (aka ziphodonty), but the implications are nonetheless quite interesting. Not only is it the best evidence we have for insular sebecids and would have been the islands apex predator, but it also extends the survival of Sebecidae by perhaps up to 5 million years. This means the group might have survived until the Early Pliocene.

The Hispaniola sebecid, tentatively assigned to Sebecus sp., as illustrated by Machuky Paleoart

Now full disclosure, these remains are NOT the first evidence of what could be sebecids from the Caribbean. Previous discoveries include teeth from the early Miocene of Cuba as well as the early Oligocene of Puerto Rico. However, what makes the Hispaniola remains so much more important is surprisingly the presence of vertebrae. Hear me out. Sure, the teeth are iconic and easily identifyable, however, ziphodont teeth are not unique to sebecids and have also evolved independently in more "modern" crocodiles such as planocraniids and mekosuchines. Sure, mekosuchines were definitely not hanging out on Hispaniola and planocraniids are accepted to have died out during the Eocene, but nonetheless this means that ziphodont teeth could also belong to another type of croc. HOWEVER, the vertebrae from Hispaniola are described as amphicoelous, while animals closer to todays crocs would have procoelous vertebrae. Ergo, ziphodont teeth + amphicoelous vertebrae = sebecid, making these remains the first unambiguous evidence for Caribbean sebecids.

A simplified phylogeny showing the repeated evolution of ziphodont teeth in crocodyliforms while also highlighting the diferences in notosuchian and eusuchian vertebrae.

Case and point for why thats important? Well while the remains from Cuba and Puerto Rico are most likely also sebecids based on their age and geography, there are even older fossil remains of a ziphodont croc from the Middle Eocene of Jamaica. While sebecids were already around back then, so were the planocraniids, hooved crocodile-relatives found across North America and Eurasia. And since Eocene Jamaica has faunal similarities with North America, this particular ziphodont is more likely to be a planocraniid than a sebecid.

While the Cuban and Puerto Rican teeth are likely those of sebecids, the Eocene Jaimacan ziphodont croc could have easily been a planocraniid similar to the widespread genus Boverisuchus, illustrated here by Corbin Rainbolt.

Those that read my post on Tewkensuchus might remember my barely coherent ramblings about how confusing and poorly understood the paleogeography of sebecids is. Well for what its worth, if we ignore all the chaos caused by Europe's part in the equation, the South American history is relatively straight forward. The Paleogene record spans both remains found in the far South as well as Eocene records further north at lower latitudes. It's not entirely clear how sebecids got to the islands, but it is speculated that they could have rafted or even traveled across temporary land bridges that formed at times of lower sea levels. Whatever the case, by the early Oligocene sebecids seem to have made it to Puerto Rico and would have likely been isolated from the mainland and from other island populations when various marine passages opened, splitting the island chains. This may have been a blessing in disguise, as by the Miocene sebecids were restricted to tropical environments at low and mid latitudes and further habitat collapse, tied in part to the disappearance of the Pebas Mega Wetlands, eventually lead to their extinction on the mainland by the early Late Miocene.

But if the fossils from Hispaniola are anything to go by, then they clung onto life for another 5 million years in the Caribbean, retaining their spot as the islands apex predators until possibly as late as the Early Pliocene. Alas, they couldn't evoid extinction forever and unless we find even younger remains the Hispaniola sebecid represents the last hold out of the once diverse group Notosuchia.

Predator guilds and their distribution in South America throughout the Paleogene (a), Neogene (b) and late Quaternary (c).

But in a way, they didn't go without leaving their mark on the island. After sebecids went extinct, there seems to have been a push by native birds towards more terrestrial life, with some species losing the ability to fly alltogether. Some birds of prey seem to have taken up the mantle of terrestrial predator, leading to owls like Ornimegalonyx on Cuba and even the only distantly related Cuban crocodile threw its hat into the ring when it came for the spot of apex predator.

Top: A cuban crocodile hunting a small species of ground sloth, illustrated by Manusuchus Bottom: A general overview of the fauna found on Cuba during the Pleistocene, including flightless birds, cuban crocodiles and terrestrial owls, illustrated by Joschua Knüppe

#sebecidae#sebecus#sebecosuchia#notosuchia#pliocene#palaeoblr#prehistory#croc#crocodile#cuban crocodile#planocraniidae#pseudosuchia#long post#science news

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tewkensuchus: King of Punta Peligro

Last month we got our fourth croc of the year and our second notosuchian: Tewkensuchus salamanquensis (Forehead crocodile from the Salamanca Formation), a large-bodied sebecoid from the earliest Paleocene of Argentina. And GODDAMN is it a cool one.

Below some of the fossil material of Tewkensuchus, it doesn't look like much but stay with me for this post.

Starting with the fossil material, Tewkensuchus is admittedly not the most complete sebecid, hell Dentaneosuchus from two years ago is significantly better preserved. Essentially, Tewkensuchus preserves a bit of the skull and a few vertebrae. But the material we do have is exceptional in other ways. Like some European sebecoids, it had a high and broad sagittal crest that extends over its forehead flanked by two broad depressions. Remember the similarity to European sebecoids, thats gonna come back later. Theres also some interesting stuff in how the bony eyebrows, the palpebrals, articulate with the rest of the skull.

What is REALLY weird however is the shape of the postorbitals. Quick anatomy lesson, in crocs the postorbitals form the front corners of the skull table thats located just behind the eyes. They tend to be flat, but in the case of Tewkensuchus they are inclined so that they rise upwards behind the eyes. Now we have plenty of examples of crocodylomorphs with raised squamosals, giving them a somewhat ear-like appearance, but raised postorbitals are a new one.

Below: An artistic interpretation of Tewkensuchus featuring its unique cranial morphology by Manusuchus (give them a follow) from different angles.

One last thing on its anatomy, it was BIG. And I mean big. The team that described Tewkensuchus estimate that its complete skull might have been just over half a meter long, so some 20 inches. This might correspond to a weight of perhaps 300 kg (660 lb), larger than even the largest Cretaceous Baurusuchids.

Now, I hope you remember the part where I said that theres similarities to European sebecoids. Well that sentence has two key points the paper deals with. First of all, the connection to European forms itself. Phylogenetic analysis seems to indicate that despite being found in Patagonia, all its closest relatives are from the Eocene of Europe. These are the recently named giant Dentaneosuchus from France, Bergisuchus from Germany and Iberosuchus (I'll let you figure that one out for yourselves). So after Tewkensuchus disappears South America is inhabited by only distant cousins while its closest relatives show up some 20 million years later on the other side of the Atlantic.

The other noteworthy part of the statement is the use of "Sebecoid" rather than sebecid. That's because of taxonomic back and forth. Essentially, a few previous studies have not included European sebecoids (Bergisuchus and Iberosuchus) within the family Sebecidae, instead featuring them as a separate branch that split off beforehand. In some studies that branch is known as Bergisuchidae, in others they are two branches, you get the idea. Now the description of Dentaneosuchus for instance did away with Bergisuchidae and simply include these European forms within Sebecidae itself. Still as the basalmost members, but given the honor of being at least included. Same goes for Ogresuchus. Well, in the description of Tewkensuchus, we go back to the separate model. So Bergisuchus, Iberosuchus, Dentaneosuchus and Tewkensuchus all form a single not officially named group simply referred to as the "Eurogondwanan clade". This group was placed as the sister family to Sebecidae and together with Ogresuchus the two form the newly named Sebecoidea.

Europe's sebecoids, Dentaneosuchus (art by Joschua Knüppe), Bergisuchus (by Scott Reid) and Iberosuchus (once again Manusuchus)

And this is where we need to address the fact that Tewkensuchus creates a bunch of new problems and makes old ones worse. For starters, it's size. By all accounts its way too big. Keep in mind, this animal appeared some 2 to 3 million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs, an extinction event that is generally thought to have killed everything on land heavier than 10 kilos. And then you get Tewkensuchus with an estimated weight of 300. Well, there's two possible explanations for that. Explanation 1 hinges on the known fact that these rules don't quite apply to semi-aquatic animals. Sure, anything large on land got whiped out, but eusuchian crocodiles managed to survive quite well despite their large size in part because they were partially aquatic. So perhaps Tewkensuchus and sebecoids as a whole underwent an aquatic phase? Well, this would work quite well with what is known as the Sebecia-hypothesis. Essentially, there is some debate on the relationship between sebecids and other notosuchians. Some studies draw a link between them and the similarily terrestrial baurusuchids, placing them in the group Sebecosuchia. Other studies meanwhile believe that sebecids are most closely related to peirosaurids, which in turn are close kin to itasuchids and mahajangasuchids, with both of the latter being more semi-aquatic than other notosuchians. The problem with this is twofold. On the one hand, to my knowledge there has never been any indication that sebecids underwent an aquatic phase and even Cretaceous sebecoids like Ogresuchus from before the impact were clearly terrestrial. The other issue, as nice as this would fit with the Sebecia-hypothesis, this particular study actually recovers the Sebecosuchia model. So there's that.

Personally I don't really buy into this explanation, which takes us to the second possibility. Sebecoids got really jacked really fast. I mean, that's it really. If sebecoids didn't undergo some weird little phase that somehow excempts them from the 10 kilo rule then the only logical answer is that they must have grown to a ridiculous degree the second the dust settled. Do we have evidence for that? Well....kinda but not really no. The closest we have is the fact that Dentaneosuchus from the Eocene clearly reached an enormous size on its own, but that was over 20 million years after the impact. We do at least know that sebecoids were small prior to the KPG thanks to Ogresuchus from Spain, which grew to only a meter in length. But a sample size of one isn't exactly exact proof that all sebecoids were small prior to the impact, especially with shifting phylogenies. The paper itself argues that its most parsimonious that whatever sebecoid crossed the boundry was already fairly large, but time will tell if this holds up. Whatever the case, with a skull half a meter in length it was certainly a formidable predator and a terrifying sight to any unfortunate mammal to cross its path.

Tewkensuchus attacking a startled Monotrematum, a South American monotreme, art by Joschua Knüppe

Finally the last thing to address, paleogeography. It sucks. Moving on. Jokes aside, sebecoid geography was already a pain in the ass. Assuming the sebecosuchian model, sebecoids likely split off from baurusuchids during the Santonian. Mind you this is purely based in the first appearance of baurusuchids, since sebecoids didn't appear for quite a while. Ignoring the problematic Doratodon, the first sebecoid to appear in the fossil record is Ogresuchus in the Maastrichtian of Spain. In the Paleocene we then obviously get Tewkensuchus representing the Eurogondwana clade in Argentina as well as sebecids proper, which seem to be constrained to South America. But then in the Eocene we suddenly have sebecoids in Europe and Africa (for simplicity I'm assuming that Eremosuchus was a sebecoid rather than a sebecid as is traditional). So, how does any of this work? We don't know. I've been breaking my head over how to best explain this without just repeating the paper itself, so let me just say this. Maybe sebecoids originated in South America with baurusuchids, they managed to enter Europe at the very least once giving rise to Ogresuchus, probably via Africa given that its very much undersampled. From there who fucking knows. Maybe Ogresuchus was just one random branch and the two main groups both actually originate in South America. Maybe the Eurogondwana group emmigrating to Europe as well while sebecids proper remained. Maybe the Eurogondwana group originated in Europe and Tewkensuchus simply returned to South America, or maybe they originated in Africa and had members travel west to South America and north to Europe. Or maybe....you get the idea, we don't know. We don't know if they rafted or took land bridges (tho the latter seems more likely), we don't know where certain groups first originated in actuality, we do not know a lot and Tewkensuchus being such a blatant link between Paleocene South America and Europe, which were well separated by that point, raises so many questions.

I imagine this is what this entire last section reads like....

I wish that last segment wasn't as chaotic as it is, but like I said, its a big old confusing mess and it gives me a headachse just thinking about it. So for the time being, its simplest to assume that they split from baurusuchids in South America and then some stuff happened we don't understand. Personally, I'm very much putting my trust in Africa here, I am 100% convinced that some very important stuff went down that we just haven't found yet. But thats just me.

#tewkensuchus#sebecidae#sebecoidea#bergisuchidae#sebecosuchia#evolution#palaeoblr#paleontology#prehistory#pseudosuchia#notosuchia#ziphosuchia#crocodile#croc#paleocene#cenozoic#kpg extinction#long post

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cryptic Crocs of the Caribbean

I have been positively swamped with work and other responsibilities and of course that's just when theres a lot of really interesting papers coming out. The subject of this particular post is something a little more recent than my usual focus, by which I mean it concerns crocodiles very much alive right now.

In "Novel island species elucidate a species complex of Neotropical crocodiles", author Jose Avila-Cervantes and colleagues present a large scale project attempting to establish a more robust history of neotropic crocodiles by taking a closer look at species and population divergences, specifically through genomic and phenotypic data.

Part of the stated goal was to try and shine a closer light on the relationships among the neotropic species of Crocodylus (consisting of Morelet's crocodile, the American crocodile, Orinoco crocodile and Cuban crocodile), who's phylogeny remains somewhat poorly known. One of the complicating features is the poor fossil record. I've mentioned it before, but as it is currently understood, the oldest neotropic crocodile is C. falconensis from the Pliocene of Venezuela, which sits outside the modern species and might be most closely related to the Miocene C. checchiai from northern Africa, by extension establishing a link to today's African species. Beyond that tho the American fossil record is poor, with fossils typically only identifyable to the genus level (not counting some island localities preserving the remains of Cuban crocodiles). The second complicating feature is the fact that neotropic crocodiles seem to be quite fond of interbreeding, with hybrid populations between American and Morelet's crocodiles present along the Yucatan Peninsula and possible hybrids between Cubans and Americans on, well, Cuba.

The four classically recognized species of the neotropics, the large American crocodile (Jose's crocodile river tour, top left), the agressive Cuban crocodile (Steve Cooper, top right), the humble Morelet's crocodole (yours truly, bottom left) and the slender-snouted Orinoco crocodile (Phoebe Griffith, bottom right)

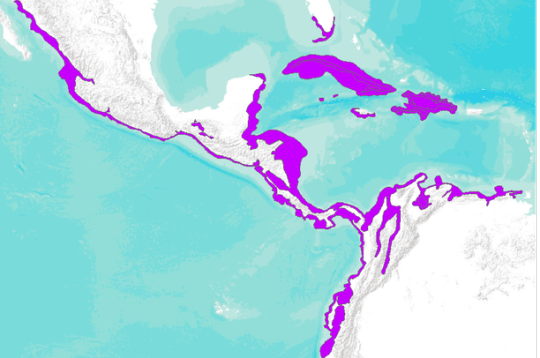

Particular focus of the study is the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus), given that it is without a doubt the most wide ranging of today's neotropic crocodiles. This species ranges from the Mexican Pacific coast to Florida and south to northermost Peru and Venezuela as well as a huge swath of the Caribbean, inhabiting both inland freshwater biomes as well as mangroves, islands and everything in between.

The current range of the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) via Data Basin

However, as a consequence the paper has found that there is quite a lot of genetic variation within this species, especially among the populations of the Mexican Pacific Coast and island populations. Now in terms of morphology it is noted that the range of American crocodiles is quite wide, with the phenotypes of island and mainland species overlapping. However it is also noted that there is only minimal overlap between the island forms themselves.

Especially distinct are two populations found south-east of Yucatan, namely those of Cozumel island and the atoll of Banco Chinchorro. Phylogenetic trees actually suggest that these two form their own branch among American crocodiles that is positioned as the sister clade to all other populations. The two populations are noted for their surprisingly diverse genetic pool, no signs of admixture with other populations and an estimated population size of about 500 individuals each (as is highlighted by the study, this is about 10 times more than previously thought).

A crocodile in the waters around Banco Chinchorro by javie.33

As a consequence, the team supports the not-that-new idea that Crocodylus acutus is a species complex rather than a single well separated species, with the Banco Chinchorro and Cozumel populations judged to be distinct enough to warrant being given their own species names. Now the team has refrained from coining those (so far), but at least suggests naming them after their home islands. If this comes to pass and is widely accepted, then this would essentially make the two "cryptic" species, something thats happend before in crocodile research. Just to give a concrete example, similar things have previously happened with the split between Nile and Sacred crocodile (C. niloticus and C. suchus) as well as the two New Guinea crocodiles (C. novaguinea and C. halli). Furthermore, the fact that these two are distinct opens up the possibility that other populations could likewise be a lot more different than previously thought once enough genetic data is collected. One such population not given much attention in this study would be the "hybrid" population on Cuba, which the paper off handedly suggests could also represent a cryptic species.

To take a brief detour, the paper does spend some time highlighting some of the stuff that makes the Chinchorro species so distinct. Physically, they differ from their Cozumel relatives by having longer and broader skulls and subtle differences in their armor. Even their ecology is different, appearing to consume more hard-shelled prey.

Compared to other populations in general, they seem to produce smaller and fewer eggs than other populations, something that could have to do with the high salt content of the local waters. Their entire growth rate appears to be lower, taking longer to reach the same size as their relatives and females become sexually mature at a smaller size. Despite all of this however, they are doing quite well for themselves with a respectable success rate aided by the lack of predators. Following the research done on the population, the main threats to hatchlings seem to be heavy rainfall and tropical storms. What's even more interesting however is the relationship between the Banco Chinchorro crocodiles and the salinity of their surrounding environment. As is known, true crocodiles of the genus Crocodylus may have different habitat preferences, but as a whole they are quite capable of dealing with saltwater, having allowed their dispersal across much of the planet. Now the paper mentions that though prefering freshwater, Morelet's crocodiles can tolerate a salinity of up to 22 ppt (parts per thousand) while the typical American crocodile inhabits environments with a salinity of around 34 ppt. Now get this. The salinity at the Banco Chinchorro atoll ranges from 30 to 65 ppt with an average of 52.9 ppt, the highest salinity tolerated by a member of this genus.

Like the famed saltwater crocodile, American crocodiles are well known for entering saltwater.

As a final point, the study goes on to highlight the positive aspects that coining two new species could have. While populations would obviously be quite small and both islands face similar dangers, they suggest that this could be a great opportunity to use the Cozumel and Banco Chinchorro species as umbrella or flagship species to promote not only the protection of the crocodiles but also of all the other animals that inhabit this part of the world as well as their habitats as a whole. To this extent, its good to hear that while Cozumel is a partially urbanized tourist destination, some of its most important crocodile populations inhabit protected areas while all of Banco Chinchorro is a Biosphere Reserve.

Left: Naturally a major threat to these animals is habitat destruction and conflict with humans, as one can imagine might arise given their proximity to tourist beaches as recorded by Iliana Acosta Right: Over at the protected Banco Chichorro meanwhile it seems that you can actually dive with crocodiles. (Photo by Oceanographic Magazine)

As a final note I just want to say that I'm very excited to see these two animals described in proper and what other cryptic crocodiles might be found elsewhere. And of course I hope that they get the protection they need so that they are preserved for future generations.

#american crocodile#crocodylus acutus#neotropic crocodile#croc#crocodilidae#crocodile#crocodilia#herpetology#reptile#mexico#new species

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some recent croc encounter

Ive been on „vacation“ last week which honestly was mostly taking a friend to various zoos and aquariums across Austria, but that did lead me to getting to see a fair share of crocs in a fairly short time span.

Right on day 2 it was another meeting with Leila, the female Mecistops that resides in Viennas aquarium. This is now my second time seeing her and shes still a beauty.

A day later we visited the House of Nature museum in Salzburg, which had just opened its new reptile halls. As part of the makeover, which focused a lot on cohabitation and larger, natural exhibits, the museum had go part with its American Alligator that had simply become too large. While I did subsequently miss out on seeing it again after like two decades, they did get a new crocodilian in its place, a much more manageable dwarf crocodile.

The first room furthermore featured two skulls, one of a crocodile and one of a gharial, nicely highlighting the diversity of modern crocodilians. Downstairs in the dinosaur hall they also displayed the skeleton of Macrospondylus, but given how common fossils of that animal are I wont dwell on it beyond saying that its size was rather impressive.

Skipping ahead a few days brought us back to Salzburg, this time to the zoo just outside the city. While featuring nothing too large, the jaguar house still showcased a crocodilian, specifically a dwarf caiman. Alas, despite stopping by around 5 times, it was less cooperative in terms of posing than my previous two encounters. Still, the enclosure was quite nice and featured some cohabitation with basilisk lizards and bats (that I sadly couldn't find).

The last zoo of the week was in Schmieding in Upper Austria. Now when I was a kid they had a nile and, in the adjacent aquarium, some spectacled caimans. However nowadays they scaled down, having moved the caimans into the old nile crocodile pool in the rainforest house. Funny enough they were the only ones on the trip to have been on land, tho they were looking a little rough if truth be told.

And that was it in broad strokes. Some were certainly more exciting than others, Leila remains a stand out and the new Salzburg Osteolaemus was nice to see. Obviously the trips featured a lot of other interesting stuff from 9 meter sturgeon models in Bratislava to free roaming ringtail lemurs and stuffed rhinogrades in Salzburg and plenty more, but alas all four species encountered were animals I have seen before, so I don't get to cross anything off my list this time around.

#haus des meeres#vienna#mecistops cataphractus#slender-snouted crocodile#haus der natur#museum#salzburg#osteolaemus#dwarf crocodile#gharial#nile crocodile#macrospondylus#dwarf caiman#zoo salzburg#paleosuchus#paleosuchus trigonatus#zoo schmieding#caiman#spectacled caiman#crocodiles#croc#pseudosuchia#crocodilia

72 notes

·

View notes

Note

Well I suppose it in part depends on what pseudosuchians you want to take on specifically, given that its an enormous clade. I sadly do have to agree that, at least far as I'm aware, there isn't that much written about them in book form (if anyone knows better do let me know). Nesbitt's would be a start tho of course highly academic. Minor tangent I almost aquired it at a silent auction, but ultimately ended up focusing on a different book towards the end (I might be mistaken but I think Bob Nicholls ended up snatching it once all was done). If you're looking for something closer to home there is "King of the Crocodylians" by David R. Schwimmer which is written more accessibly, but of course some 20 years behind some aspects of Deinosuchus research (still worth a read imo). As for researchers, there is actually quite a few, but again its gonna depend very much on which branch you wanna focus on. Christopher Brochu is somewhat of an icon in the field I'd say, Phillip D. Mannion is a frequent sight in my experience, Jonathan P. Rio, Jeremy E. Martin, Masaya Iijima, Stephanie Drumheller, Massimo Delfino; Andre Pinheiro and Diego Pol for notosuchians alongside many others (South America is very heavy on that, Brazil and Argentina especially), Mark T. Young and Sven Sachs I often encounter when looking at thalattosuchian literature, Jeff Martz I think has done a lot on Triassic American pseudosuchians (think Chinle), I'd be remissed if I didn't give a shout out to Adam Yates and of course Jorgo Ristevski, tho a very recent contributor to the field, who has been knocking it out of the park with his research on mekosuchines. And really these are just a handfull of those that I most frequently come across in my own endevours (and that I could think of from the top of my head). There is many many more. Hell, Evon Hekkala is another great one, easily best known for her work with Voay she held a fascinating talk in London two years ago on how she got mixed up with croc research during her career.

Rest assured tho that if you specialise in crocs your efforts will not be in vain. It is true that dinosaurs get more mainstream attention, but the amount of research published on pseudosuchians should not be underestimated and there is still plenty of open questions itching to be looked into.

Probably a silly question but I want to specialize in pseudosuchians after I finish my paleobiology degree. I literally cannot find any books on just pseudosuchians, nor do I see many people in this expertise for a field. Is it really that slim? I know dinosaurs have the limelight but it makes me kinda feel as if my research won't matter or be of any use?

so I don't specialize in pseudosuchians, but the pickings are indeed slim. All the books I can think of off the top of my head are extremely academic, like Nesbitt's book. I recommend asking someone who specializes in croc-line archosaurs, such as @arminreindl

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The dinosaur one always gets to me because dinosaurs with feathers have been a thing that was proposed back in the 90s and gradually expanded on uninterupted ever since So if you claim that they are "ruining your childhood" then you either never actually cared that much about them...or you're pushing 40

"they took pluto from you" "they took dinosaurs from you" "they took neptune from you" grow a second personality trait and stop getting upset that our understanding of the world has grown since you were in 3rd grade

#paleontology#feathered dinosaurs#if anything feathered dinosaurs are getting cooler and cooler as time goes on#just compare a modern feathered raptor vs one from the 90s

36K notes

·

View notes

Note

How old are you? Also, can you list every single crocodilian or crocodilomorph that has ever existed?

I cannot list every single crocodylomorph, by all accounts there is too many which I do not know from the top of my head (I'd probably recognize the name but thats something else).

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Croc Paleontology Recap Febuary 2025

January passed so fast probably cause its the shortest month but we still got a handfull of papers out of it. So lets get right into it.

The function of the armor of Stagonolepis

Getting us started in the Triassic is a paper on the osteoderms of the aetosaur Stagonolepis: "The histology and function of the dermal armour of the aetosaur Stagonolepis olenkae Sulej, 2010 (Archosauria, Pseudosuchia) from Krasiejów (SW Poland)". Now as you probably figured from the handfull of times I've talked about aetosaurs on here, their osteoderm armor is very characteristic, very important in telling them apart and VERY extensive.

The results of this study are interesting. For starters, although osteoderms frequently serve a function in thermoregulation in modern crocs and even temnospondyls, this does not appear to have been the case for Stagonolepis. Now superficially, aetosaur osteoderms do show the same pitted surface as modern croc armor, which is caused by the elements absorbing bone and depositing it elsewhere throughout growth, something that reduces mass while maintaining stability and also increases surface area. However, Stagonolepis osteoderms are not vascularized like those of modern crocs, lacking the densely packed blood vessels that help absorb heat. The external surface of the osteoderms also doesn't show signs of thick sharpeys fibres, which are generally used to anchor the osteoderm in the soft tissue. What this means is that the osteoderms were not deeply embedded in skin (as has been suggested for some notosuchians) but rather were covered in keratin like those of modern crocs. But if not for thermoregulation, then what are the osteoderms for. Well on the one hand, obviously they work as armor. Their structure makes them robust yet leight weight and they are firmly embedded through sharpeys fibres present on the lower cortex of the osteoderms (tho its highlighted that they aren't as densely packed as in ankylosaurs). The keels that mark the osteoderms further prove to be quite usefull when it comes to reducing stress from a vertical attack. If you really want an additional reason for the armor, the authors offer the suggestion of being an adaptation to prevent water loss. Finally, histology shows that the osteoderms do not feature lines of arrested growth (basically signs for poor growth throughout the animals life), which suggests that the environment inhabited by Stagonolepis was quite moderate and did not have strong seasons that might influence the animals growth throughout its life.

Bottom: A diagram of Stagonolepis is sideview, showing the various types of osteoderms covering its body. Reconstruction by S. Górnicki

Growth strategy in Trialestes and its implications

Up next something not too different from a study we had in January. Last time we had a study on the growth of a peirosaurid notosuchian, this time "A fast start: Evidence of rapid growth in Trialestes romeri, an early Crocodylomorpha from the Upper Triassic continental beds of Argentina based on osteohistological analyses" brings us something similar except for the "sphenosuchian" Trialestes (more on that group later).

So what did we learn? Well for starters, neither of the examined specimens (which included the holotype) were mature, both in terms of sexual maturity and skeletal growth. What is weird is that morphology (specifically bone fusion in the vertebra) indicates the opposite to what has been concluded based on bone microstructure, which may suggest that in Trialestes either reached sexual maturity at a delayed rate of that histology and sexual maturity do not correlate all that much. Anyhow, based on crosssections of the bones, they are estimated at a minimum of two years and one year of age at the time of their deaths. Histology also shows that Trialestes appears to have grown quite rapidly. Curiously a previous study estimated a third specimen to have been one year old, eventhough this new study recovered the same age for a specimen only half that size. This seems to suggest that age and growth do not really correlate for some unknown reason, with possible explanations including differences between sexes or simply differing environmental conditions. Looking at the results at a grander scale, similar growth rates have previously been calculated for other nimble crocodylomorphs such as Terrestrisuchus and Saltoposchus, with the latter growing even faster than Trialestes. Of course when you get into more derived members of Crocodylomorpha strategies start to change, for example the slightly more derived Hesperosuchus was growing at a slower speed than Trialestes and if you recall January we know that Notosuchians can differ even within a genus (see Araripesuchus). Modern crocs appear to generally grow slower overall in their ontogeny, tho in some like the broad-snouted caiman environmental conditions seem to play quite the rolle. Nevertheless, the paper concludes that faster growth rates appear to be more widespread in early crocodylomorphs and may have been the ancestral condition.

Below: Reconstruction of the head of Trialestes by Joschua Knüppe (there is really not much art of this guy out there)

Now for two papers that are very relevant to my efforts on Wikipedia, namely two studies on the European alligatoroid Diplocynodon.

Growth strategy of Diplocynodon hantoniensis

First of all, sorta the same thing we just had for Trialestes but applied to Diplocynodon hantoniensis, a species from the Eocene of southern Britain (and actually one of the first Diplocynodon species discovered). The greater goal of "Evolution of growth strategy in alligators and caimans informed by osteohistology of the late Eocene early-diverging alligatoroid crocodylian Diplocynodon hantoniensis", as you might guess from the title, is actually to use Diplocynodon in order to figure out how growth strategies evolved in the two modern groups of alligatoroids, gators and caimans, who share similar strategies despite having been separated from another since before the extinction of the dinosaurs.

With 9 studied upper leg bones, the sample used in the study ranged from immature specimens to adults, which in the case of D. hantoniensis might reach lenghts of 1.2–3.4 meters. The growth strategy of Diplocynodon is recovered as both being determinate (meaning that they stop growing at a certain point) and seasonally controlled (which feels self-explanatory), both also seen in modern alligatoroids. Now assuming that the growth marks accurately reflect yearly intervals (which may not necessarily be the case), then the studied individuals ranged between 5 and 26 years old at the least. Skeletal maturity seems to have been reached in a similar range as modern alligatoroids (gators reaching maximum size between 30 and 40 and caimans between 12 and 18). As with Trialestes earlier, there are some individuals that show signs of being fully grown, yet are less than half the size of other individuals, possibly indicating sexual dimorphism (female gators stop growing earlier and at a lower size than males) or environmental conditions that affected growth (though there is doubt cast over this latter interpretation). The study concludes that, based on Diplocynodon hantoniensis, alligatoroids are simply relatively conservative in their growth strategy and what we see in gators and caimans is likely their ancestral strategy, rather than having been developed independently.

Below: A photo of the skull of Diplocynodon hantoniensis (taken by John Cummings), not actually relevant to the study but I mean it shows what this thing looked like.

The sense of smell and EQ of Diplocynodon tormis

Moving away from the Eocene of the UK and to the Eocene of Spain, we got a different species of Diplocynodon as the main subject of "New data on the inner skull cavities of Diplocynodon tormis (Crocodylia, Diplocynodontinae) from the Duero Basin (Iberian Peninsula, Spain)". Specifically, the study deals with the description of and what we can learn from a CT-scan that gives us insights into the forebrain, olfactory bulbs, nasal cavity, air sinuses, etc..

Overall the shape of the brain matches the idea that Diplocynodon is an early alligatoroid, including some distinctive features of this clade and some traits that are basal to crocodilians. Like modern alligators, Diplocynodon tormis seems to have had a good sense of smell, though not as keen as that of crocodyloids. The holotype specimen falls within the upper values in terms of olfactory acuity among alligatoroids, but still clearly outside of the range exhibited by crocodyloids, while another studied specimen performed a lot poorer (though its also not as well preserved). As for cognitive abilities, the study also calcuated the Reptilian EQ of D. tormis. The authors note that the EQ of Diplocynodon tormis appears below the average of other medium-sized crocodilians and instead comes closer to the EQ of large forms. Tho it is also noted that damage to the specimen might have affected the results.

Left: A 3D model of the holotype skull of Diplocynodon tormis Right: A 3D model of that same skull but highlighting the various internal structures such as the brain, nasal cavity, nerves, etc..

A history, redescription and the biology of the teleosaur Macrospondylus

Ah Macrospondylus bollensis, once known under the name Steneosaurus (like every other teleosauroid lets be honest), perhaps one of the most well known members of this group given its extensive fossil record from the Posidonia Shale in Germany. Despite this, and also like many other teleosauroids, its history is confusing, long and just a whole can of worms. One dealt with in "A re-description of the teleosauroid Macrospondylus bollensis (Jaeger, 1828) from the Posidonienschiefer Formation of Germany".

To give you the abridged version, the holotype of Macrospondylus bollensis was found all the way back in 1755 (meaning it was discovered so long ago even Napoleon wasn't born yet) and quickly recognized as some sort of crocodile relative. It was named Crocodilus Bollensis in 1828, described in the 1830s and given the genus name Macrospondylus in 1831 (and then again by a different author in 1837, seemingly independent of the previous study).

Being this old, of course the fate of Macrospondylus would be shaped by historical events, specifically the German revolutions of 1848–1849, when a fire set by revolutionaries in Dresden grew out of control and spread to the collection, damaging but thankfully not destroying the fossil. Chaos ensued unrelated to that as various researchers proceeded to lump Macrospondylus into either Teleosaurus, Mystriosaurus or even Geosaurus before circling back to Crocodilus, eventually settling on Steneosaurus in the 1960s. Scientists did eventually grow wise to Steneosaurus being an overlumped wastebasket of a taxon, but this was not fixed until 2020 when this gordian knot was hacked to pieces once more, resulting in the revival of Macrospondylus.

Keeping all this confusion in mind, recent work including this paper still finds that Macrospondylus is actually the most abundant Toarcian teleosaur and especially common in Germany (no doubt thanks to the Posidonia Shale, this doesn't necessarily reflect how things were at the time). In terms of ecology, Macrospondylus may have been a long-snouted generalist, being able to consume a much wider selection of and overall bigger prey than some of its rarer relatives. Size might also have been a factor, since large Macrospondylus reach up to 5 meters in length and would therefore have access to more robust and larger prey. Its wide distribution might also suggest that it was less picky than other teleosauroids about where it lived and though previously suggested to have been more marine, this new study seems to favor the idea that it was still fairly amphibious throughout its life. This is interesting given that the Posidonia Shale, where so many specimen are known from, is a pelagic off-shore open ocean environment, with the potentially more terrestrial Platysuchus and the shallow water Plagiophthalmosuchus being much rarer. Of course, there is always the possibility that this idea of Macrospondylus being super common is skewed simply by the preservation and the excavation at Holzmaden, which as said before might not reflect the state of the entire species population.

Left: A fossil of Macrospondylus next to Dr. Michela Johnson, photo by Meike Rech Right: Thalattosuchians from Tübingen by Pascal Abel, the two skeletons on the left wall and the bottom slab on the right all represent Macrospondylus Bottom: Macrospondylus photographed by Sven Sachs

The metabolism of Notosuchians

Back to something less constrained to any specific taxon, we got "Revisiting the aerobic capacity of Notosuchia (Crocodyliformes, Mesoeucrocodylia)",a paper on notosuchian metabolism, which is one of those things that might surprise people unfamiliar with them.

Of course Notosuchia is the great post-Triassic terrestrial radiation of the crocodile-lineage, bringing forth a great diversity of land-dwelling froms from small omniv, ores, bulky herbivores and even lanky carnivores. Despite this, it might come as a surprise that they were in fact not "warm blooded". This is again reinforced by this months paper by Sena and colleagues, who recover that their mass-independent maximal metabolic rates lie somewhere between modern crocs and monitor lizards (which again fits with previous studies on the matter). This means that fitting with their anatomy and lifestyle, they were more active than modern crocs and able to sustain more vigorous activity. Being ecto-thermic, they were still dependent on outside temperatures to heat them up before they were able to really take things to their fullest. Consequently it has also been hypothesized quite a bit that to cool down, they might have entered burrows later in the day.

Left: Two Baurusuchus are shown hunting a small Caipirasuchus, with all individuals shown as being fast, agile and terrestrial. Artwork by Deverson da Silva Right: Armadillosuchus emerging from its burrow under a tree stump with a herd of sauropods in the back. Artwork by Julia d'Oliviera

Now, for what I'm guessing all five of you that made it this far have been waiting for. The newly named crocs....which I didn't have time to make dedicated posts for. Look shit sucks alright, weekends have been really brief this month and I feel very tired.

Pattisaura: A new sphenosuchian from Texas

Getting us started on Pattisaura, a new genus of "sphenosuchian" (I told you I'd come back to them) from the Late Triassic Cooper Canyon Formation of Texas. Described in "A new crocodylomorph (Pseudosuchia, Crocodylomorpha) from the Upper Triassic of Texas and its phylogenetic relationships", this little guy generally represents what one might see as a quintessential sphenosuchian. A somewhat body pointed skull with large eyes, terrestrial habits, long and slender legs, a far cry from what we tend to associate with crocodylomorpha today.

The name Pattisaura was coined in honor of Mrs. Patricia Kirkpatrick, who's family has let paleontologist look for fossils on their farm (gee I wonder why that name sounds familiar) and the species name gracilis derives from....I mean do I even need to say it?

Unsurprisingly, the phylogenetic analysis of this study shows that Sphenosuchia is paraphyletic and doesn't actually form a single clade, instead simply representing a series of consecutively branching early crocodylomorphs. What can be said is that Pattisaura seems to clade with Redondavenator.

While perhaps unassuming in size or ferocity, little Pattisaura is nonetheless an interesting addition to the pseudosuchian fauna of the Cooper Canyon Formation, which has previously yielded the remains of the phytosaur Machaeroprosopus, various aetosaurs including Desmatosuchus, Aetosaurus, Typothorax and Paratypothorax, poposauroids like Shuvosaurus and the iconic Postosuchus alongside many other Triassic classics such as drepanosaurs, silesaurids, lagerpetids, coelophysoids and more.

Left: The skull of Pattisaura photographed by Aaron dp Right: The skull in top, bottom and sideview, reconstructed to account for taphonomic distortion and damage to the material

Thilastikosuchus: Brazil's oldest notosuchian

And the final one for this month is Thilastikosuchus scutorectangularis (mammal crocodile with rectangular scutes) described in "Anatomical description and systematics of a new notosuchian (Mesoeucrocodylia; Crocodyliformes) from the Quiricó Formation, Lower Cretaceous, Sanfranciscana Basin, Brazil". This little guy, and I mean little as it is based on a juvenile specimen, was recovered from the Early Cretaceous Quiricó Formation of Brazil and represents a new member of the obscure family Candidodontidae.

To give a brief description, Thilastikosuchus was a small, slender-limbed animal, although admittedly we only have a juvenile to go off from. Its teeth are prominently heterodont, meaning that rather than having jaws filled with relatively similar conical teeth its dentition was a lot more diverse, specifically consisting of subconical incisiforms and molariforms with multiple cusps. The armor of the body, as the name suggests, is rectangular with a smooth outer and back edge, eventually transitioning into the square osteoderms of the tail that possess a prominent keel down their middle. As with most notosuchians, there were only two rows that run down along the spine, rather than the more complex armor seen in modern crocodiles.

Perhaps most interesting are the phylogenetic and evolutionary implications of this animal. Thilastikosuchus is the oldest known notosuchian from Brazil and perhaps even the oldest notosuchian of all of South America, which might have big implications for the groups evolution. It is placed as a member of the Candidodontidae, a family coined to include Candidodon and Malawisuchus but not always regarded as a distinct group throughout publications. This new paper specifically places them at the very base of Notosuchia, branching off even before Uruguaysuchidae and Peirosauria. Given the very mammal-like teeth of candidodontids, this raises the question whether or not such dentition was simply convergently evolved by them and sphagesaurids (assuming their position amongst notosuchians holds true) or if its the ancestral condition that was later lost by groups such as uruguaysuchids and baurusuchids. It also adds an interesting aspect to the diversification of the group. As things stand, the oldest known notosuchian is Razanandrongobe from the Jurassic of Madagascar, but this taxon and its significance are poorly understood. With this new paper, we definitely see a clear diversification of notosuchians in the earliest Cretaceous through candidodontids, another radiation later in the Albian with uruguaysuchids and peirosaurs and a final burst in diversity towards the end of the Cretaceous with the numerous forms known from the Bauru group.

Left: Skeletal reconstruction of Thilastikosuchus with special focus on the osteoderms by Felipe Alves Elias Right: Live reconstruction by the same artist with an adult individual looming in the background

#palaeoblr#paleontology#prehistory#croc#crocodile#long post#pseudosuchia#notosuchia#thilastikosuchus#pattisaura#macrospondylus#teleosauroidea#diplocynodon#alligatoroidea#trialestes#aetosauria#stagonolepis#crocodylomorpha#science news#february 2025#fossils

27 notes

·

View notes