Audrey | she/her | Chinese fashion history Ming, Qing & 20th century | NO ‘ANCIENT CHINA’ IN THIS HOUSE | on hiatus?? busy irl

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

@d-m-a-c found this picture from 1936 showing three young graduates and a missionary, where the girls are wearing thick winter cheongsam.

hi, i don’t know if something like this has been asked already. I’m not very familiar with cheongsam and I was curious, from pictures I’ve seen, cheongsam dont seem very warm to me, did there exist a style of cheongsam to wear for colder temperatures during the time period it originated? thank you

Hi, that's because people could wear jackets and coats over cheongsam to keep warm. I have a post about winterwear in the Republican era. More fashionable women would sometimes wear short sleeves even in winter. Working women or those less concerned with trends can wear a cheongsam with longer sleeves made in thicker fabrics as well; they would have the same cut as fashionable cheongsam so they're not a separate style per se.

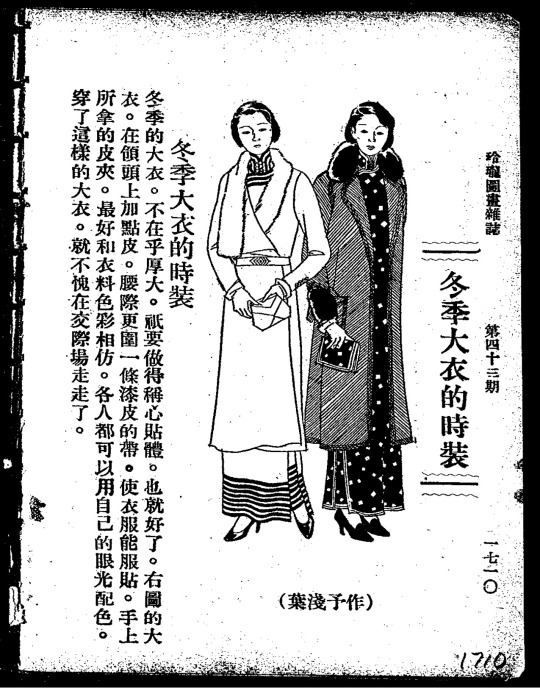

Fashion illustration by Ye Qianyu showing coats for long cheongsam, from Ling Long magazine, 1932.

Long sleeved cheongsam in thicker fabric, from the 1948 movie Spring in a Small Town.

179 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, i don’t know if something like this has been asked already. I’m not very familiar with cheongsam and I was curious, from pictures I’ve seen, cheongsam dont seem very warm to me, did there exist a style of cheongsam to wear for colder temperatures during the time period it originated? thank you

Hi, that's because people could wear jackets and coats over cheongsam to keep warm. I have a post about winterwear in the Republican era. More fashionable women would sometimes wear short sleeves even in winter. Working women or those less concerned with trends can wear a cheongsam with longer sleeves made in thicker fabrics as well; they would have the same cut as fashionable cheongsam so they're not a separate style per se.

Fashion illustration by Ye Qianyu showing coats for long cheongsam, from Ling Long magazine, 1932.

Long sleeved cheongsam in thicker fabric, from the 1948 movie Spring in a Small Town.

179 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello Audrey

I'm almost sure you were talking about the origin of cheongsam at one point, how scholars are not sure it comes from manchu fashion, contrarily to popular opinion, and I can't find it (I'm sorry, I looked... Your tumblr is well organised, but I still couldn't find it)

Do you remember what post it was?

Thanks!

Oh sorry I can't really remember either, I mentioned it in the 1930s post and also this book review but there might be some other instances.

To recap, the origins of cheongsam/qipao are genuinely unclear and there could be multiple sources of inspiration. If I remember correctly, amateur fashion historians speak of two separate garments named 'qipao' from the 1920s: one a long coat inspired by Manchu women's robes popular in 1921 but disappeared quickly afterwards, and another an unrelated one piece dress of a similar cut to contemporary aoqun popularized around 1925-6. The latter is what became the cheongsam of mainstream women's fashion we're familiar with.

I think even if the idea of a one piece long dress with side slits was taken from Manchu women's fashion, the cheongsam of popular Han women's fashion differed much too much from contemporary Manchu women's dress to claim any affinity whatsoever. The cheongsam also didn't 'descend' from Manchu women's robes in the way many popular history narratives frame it, in that there was no direct lineage and Manchu women played no role in the creation of it.

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are there my books that you would suggest for people looking to learn about Qing dynasty or Ming dynasty clothing that's historically accurate? I'm looking to learn about these two periods as they are my favorite.

Thanks

For the Ming I would recommend the classic Q版大明衣冠图志 by 撷芳主人, and the more recent 明鉴:明代服装形制研究 by 蒋玉秋. There's also the slightly more obscure 明代服饰研究 by 王熹, though I haven't seen a review of its contents so I can't vouch for the quality. I'm under the impression that these books focus on ceremonial garments, so extra research needs to be done for changing civilian fashion trends. Unfortunately they're all in Chinese as I don't know of any good books in English or other languages.

For the Qing, there really exists no single book that's even remotely historically accurate and devoid of methodological issues (e.g. 18th century erasure) that I'm aware of. Scholarship on Qing Dynasty Han women's fashion in general is honestly very crap, so I would recommend steering clear of it. Amateur historians and collectors on social media often prove to be more reliable, so piecing bits together from random posts that I come across is sadly the best I can do. I've found some books unrelated to fashion history that ironically have better information on Qing popular fashion, you can see them in my book review tag.

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I have a question about... sleeves.

I am looking at designing what is essentially, in-universe, a stage costume but still want it to be at least a tiny bit historically accurate.

It would be a late Jiaqing era (~1810s) inspired aoqun, with a mamianqun (specifically a fengweiqun) and possssssibly a cloud collar to form an ensemble that's intended to portray a fenghuang (thus the skirt lol) and probably somewhat fancy on account of the celestial nature.

I know that sleeves in China have historically often been either long or Extremely Long especially for noblewomen but I was wondering about how that extends (ha) to the Jiaqing era of the Qing Dynasty.

I see, for example, Ming-style clothing that has these very long, drapey sleeves such as these: https://ziseviolet.tumblr.com/post/702949049252364289/ (though I know the Ming would have ended like 200 years before the 1810s but I also know you've mentioned that a lot of Ming fashion continued into the Qing for a while) I like the way they look on account of being very flowy which seems fitting for a bird-themed outfit where the person wearing it would be essentially portraying the fenghuang onstage, so long flowing gauzy shapes seem very fitting, but I'm not sure how much flexibility there is for late Qing sleeve styles or how much creative license goes into those types of XYZ dynasty-inspired outfits.

Relatedly I'm curious how common sheer, soft-draped fabric like that would have been in the early 1800s. I know it was very popular in certain eras, and of course in western fashion at the time Regency clothing used a lot of soft loose shapes, so I'd be interested to know if that kind of thing was particularly common in the 1810s in China or not.

I think sleeves started getting much shorter and more tight fitting in the 18th century, but wide sleeves saw something of a revival by the turn of the 19th. In the Jiaqing era, sleeves could be described as wide but not necessarily long, and usually had folded cuffs that reduced the length. I haven't read about actual garments from that period so I can't tell you concretely, but that appears to be the case from artworks.

The blogger 盥薇 did a recreation of Jiaqing era dress based on export paintings, in her interpretation the sleeves are also still a little too long to be entirely practical but definitely not as long and drape-y as that in earlier centuries. This outfit might work as a reference for your costume, since it also features a cloud collar? (on a side note, the comment section of this video gives me psychic damage, please don't look)

About sheer, soft fabrics, yes they were indeed very popular around this time, and had been since the late Ming. Sheer clothes were usually meant for lounging around the house in warm weather and not worn outside, and sometimes you see women represented as forgoing underwear altogether. I'm not sure whether that's an artistic embellishment, but it does feel feasible given the domestic setting.

I explained in this post that the cliche of 'late Ming fashion continuing into the Qing' only actually applies to the 1650s. So the Jiaqing era, being in the early 19th century, has nothing to do with the Ming.

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, could you please do a review of Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present Day by Valery Garett? Or at least give a perusal? It looks really good to a naked eye. There's clothes for different occasions, ethnic groups, and social classes. But it was also written by a white British woman, and from what I can tell her research comes from (stolen) collections in UK museums.

Also, I am confused about a passage on wedding dresses; she says Cantonese peasant women wore dark blue or black cotton for their weddings (pg 172), but I thought Chinese wedding dresses were traditionally red. (I am Chinese; I am an adoptee researching my culture; on a personal note, if it's true then I'm bummed because nobody deserves a boring wedding dress and red is so gorgeous)

Many thanks!

(Here's a pdf of the book for reference)

In my opinion, any book on Qing Dynasty fashion that uses a court dress laid flat as its cover image should be immediately dismissed, and that is exactly what I would say about this book. Unfortunately it's yet another ethnographic account coming from a white anthropological perspective, as you've identified, and is only useful if you want a caricature of your culture. Like most authors on Qing Dynasty fashion, Chinese or not, Garrett takes the 19th century as the starting date of the dynasty and offers absolutely no information on anything prior to that. This is because of both the lack of resources available to her from before western colonialism and the general framing of Qing Dynasty fashion; a common mistake, but not an excusable one. The erasure and misrepresentation of fashion in the PRC is disappointing. The book is from 2007 though, and it reads like other books from the same time, so it's not even bad in a unique way. I cannot stress this enough but please use recent literature wherever possible.

About the wedding dress thing, I wouldn't say there is one single 'traditional' color since formal wedding dresses of the Han upper classes during the Qing had multiple pieces and were not monochromatic. In the first half of the twentieth century, wedding qungua had a black jacket and red skirt, but were also embroidered with gold or silver. Blue and black were common colors for the working class in the 19th century, and it makes sense for peasant women to wear what was economical. Having fancy weddings that were a special occasion was, really, an aristocratic and bourgeois custom, and I assume working people often just couldn't be bothered.

This reminded me, I really should finish that series on Qing Dynasty Han women's fashion. Seeing published white authors be cringe with such audacity kind of motivates me.

84 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello I don't know if this has ben asked before, but, what do you think of the costumes from the Qing Dynasty drama "The long river"?

Thank you 🌺

Already answered!

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

It’s very scary, but observation on the Hanfu movement seems like Han nationalism is getting stronger in parts that it didn’t exist in beforehand, to the point where regular people are starting to internalize and push Han nationalist talking points to just literally implying other groups are slaves.

Like, any mention of Vietnam. Or the insane protest in Hanfu at the British museum over then for this year deciding to celebrate Seollal, the Korean new year instead of China’s. It’s really scary to see, and it is genuinely sad for normal Hanfu enthusiasts. Besides that, there’s also like so much horrifically bad levels of misinformation on Hanbok for example that’s viral on XHS too and sns. The sims account, British museums sns were flooded with spam posts too about it to name a few it’s just insane to see.

Unfortunately I think this has always been the case, since the rhetoric of early hanfu revivalists premised the whole movement on ethno-centric nationalism (after all, why do we need national dress if there is no nation?), so it's easy for people to slip into it even just through casual participation if they don't actively resist it. I would even go as far as saying that for many people the 'normal' hanfu enthusiast is a radical nationalist, because no singular group has the power to define what hanfu means or is. It's becoming more visible recently because hanfu is becoming more popular. The misinformation is just what people want to see *sighs*.

53 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I adore your historical posts, I mow through them like a combine harvester. I think a bunch of the master post links might be broken, though? I was trying to navigate to the Qing overview posts and they all went to the most recent one.

Hmm thanks for bringing this to my attention, seems like they still work on mobile but not on desktop. I'm not sure how to fix this but in the meantime please use the tag of the series to see the older posts :)

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are there any Kangxi-era dramas, any at all, with historically accurate costumes?

A recent drama, The Long River, has some accurate Manchu court costumes, but there is no representation of civilian Han women's fashion. Unfortunately I don't think I've seen a single drama that even attempted to recreate Han women's dress of the era.

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello Audrey, hope you are well!

This is regarding the recently aired Kangxi-era drama The Long River. It has very few scenes featuring women, I didnt complete it yet but gathered some pictures because I was curious about the fashion. I'd love to hear what do you think about these?

Styling of Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, grandmother of Kangxi Emperor.

Styling of Kangxi's mom

Some servants (left) and a middle class (probably) woman (right)

Thank you very much for your time!

These look pretty solid! Maybe the first time I've seen 17th century Manchu clothing represented with honesty. The costumes in the second and third last images look like rented guzhuang costumes, I'm not sure why there is a discrepancy in the quality of costumes?

Portrait of Empress Xiaozhuang (1613-88). I think this is the reference they used for the plain collarless robes, which are quite well tailored and true to history.

Another similar styling from the 17th century.

Portrait of Empress Xiaozhaoren (1609-89), showing the square collar jacket.

The guzhuang looking costumes might be a reference to this sort of stuff (the two ladies in the top right), but this is from the Qianlong era and 18th century. Not sure if something similar would have been done in the 17th, but either way the sleeves of the drama costumes look too short and a bit awkward.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fresh bizarre example of ‘ancient China’ just dropped. I was reading an article about architectural heritage tourism in Macau and the author described colonial architecture in the city from the 16th century onwards as ‘ancient colonial buildings’. How is this real? So the idea of ‘ancient China’ even permeates into periods that are obviously within the colonial i.e. modern era. I bet they wouldn’t describe buildings in Portugal from the same period like this but only do it here because the use of ‘ancient’ for pre-20th century China is discursively mandatory.

Also, I don’t think describing mainland Chinese tourists as ‘mindless’ for preferring to take pictures at tourist sites rather than learning about ‘deep history’ (which is colonial and traumatic) is something that can ever be considered in a ‘non-judgmental’ way as the author suggests, especially since it fits nicely into racialized ideas about Chinese people as mindless consumers.

#colonialism#orientalism#rant#articles like these really be out there making me fear things that I didn't even know could racialize me#I will be glancing over my shoulders whenever I try to take pretty pictures at touristy places from now on

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Note about periodization

I am going to start describing time periods in Chinese history with European historical terms like medieval, Renaissance, early modern, Georgian and Victorian and so on, alongside the standard dynastic terms like Song, Ming and Qing I usually use. So like something about the Ming Dynasty I will tag Ming Dynasty and Renaissance. I already do it sometimes but not consistently. Here’s why.

A common criticism levied against this practice is that periodization is geographically specific and that it’s wrong and eurocentric to refer to, say, late Ming China as Renaissance China. It is a valid criticism, but in my experience the result of not using European periodization is that people default to ‘ancient’ when describing any period in Chinese history before the 20th century, which does conjure up specific images of European antiquity that do not align temporally with the Chinese period in question. I have talked about my issue with ‘ancient China’ before but I want to elaborate. People already consciously or subconsciously consider European periodizations of history to be universal, because of the legacy of colonialism and how eurocentric modern human culture generally is. By not using European historical terms for non-European places, people will simply think those places exist outside of history altogether, or at least exist within an early, primitive stage of European history. It’s a recipe for the denial of coevalness. I think there is a certain dangerous naivete among scholars who believe that if they refrain from using European periodization for non-European places, people will switch to the periodization appropriate for those places in question and challenge eurocentric history writing; in practice I’ve never seen it happen. The general public is not literate enough about history to do these conversions in situ. I have accumulated a fairly large pool of examples just from the number of people spamming ‘ancient China’ in my askbox despite repeatedly specifying the time periods I’m interested in (not antiquity!). If I say ‘Ming China’ instead of ‘Renaissance China’ people will take it as something on the same temporal plane as classical Greece instead of Tudor England. How many people would be surprised if I say that Emperor Qianlong of the Qing was a contemporary of George Washington and Frederick the Great? I’ve seen people talk about him as if he was some tribal leader in the time of Tacitus. European periodization is something I want to embrace ‘under erasure’ so to say, using something strategically for certain advantages while acknowledging its problems. Now there is a history of how the idea of ‘ancient China’ became so entrenched in popular media and I think it goes a bit deeper than just Orientalism, but that’s topic for another post. Right now I’m only concerned with my decision to add European periodization terms.

In order to compensate for the use of eurocentric periodization, I have carried out some experiments in the reverse direction in my daily life, by using Chinese reign years to describe European history. The responses are entertaining. I live in a Georgian tenement in the UK but I like to confuse friends and family by calling it a ‘Jiaqing era flat’. A friend of mine (Chinese) lives in an 1880s flat and she burst out in laughter when I called it ‘Guangxu era’, claiming that it sounded like something from court. But why is it funny? The temporal description is correct, the 1880s were indeed in the Guangxu era. And ‘Guangxu’ shouldn’t invoke royal imagery anymore than ‘Victorian’ (though said friend does indulge in more Qing court dramas than is probably healthy). It is because Chinese (and I’m sure many other non-white peoples) have been trained to believe that our histories are particular and distant, confined to a geographical location, and that they somehow cannot be mapped onto European history, which unfolded parallel to the history of the rest of the world, until we had been colonized. We have been taught that European history is history, but our history is ethnography.

It should also be noted that periodization for European history is not something essentialist and intrinsic either, period terms are created by historians and arbitrarily imposed onto the past to begin with. I was reading a book about medievalism studies and it talked about how the entire concept of the Middle Ages was manufactured in the Renaissance to create a temporal other for Europeans at the time to project undesired traits onto, to distance themselves from a supposedly ‘dark’ past. People living in the European Middle Ages likely did not think of themselves as living in a ‘middle’ age between something and something, so there is absolutely no natural basis for calling the period roughly between the 6th and 16th centuries ‘medieval’. Despite questionable origins, periodization of European history has become more or less standard in history writing throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, whereas around the same time colonial anthropological narratives framed non-European and non-white societies, including China, as existing outside of history altogether. Periodization of European history was geographically specific partially because it was conceived with Europe in mind and Europe only, since any other place may as well be in some primordial time.

Perhaps in the future there will develop global periodizations that consider how interconnected human history is. There probably are already attempts but they’re just not prominent enough to reach me yet. Until that point, I feel absolutely no moral baggage in describing, say, the Song Dynasty as ‘medieval’ because people in 12th century Europe did not think of themselves as ‘medieval’ either. I am the historian, I do whatever I want, basically.

#I was watching an unrelated video about dnd worldbuilding#and out of nowhere someone in the comment section called 1300s chinese people 'ancient asians'#*facepalm*#so I was reminded of this again#rant#colonialism#orientalism#chinese history#historiography

947 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is just curiosity (not meant to be confrontational) but could you expand on what you mean about Chinese imperialism prior to the 19th century being “mild”? I guess I just don’t know how those two concepts can go together as imperialism usually involves some degree of violence through conquest, right?

That is a very valid question so thank you for bringing it up. I just wanted to mention the issue off hand in that post since the focus was on the hanfu hanbok debate, so I'm sorry it wasn't very well articulated. "Mild" was probably not the best word choice in hindsight (one person in the tags suggested “subtle” instead), what I meant was that Chinese imperialism prioritized the establishment of Chinese culture as normative rather than physical conquest or economic exploitation of neighboring countries, leading to a false impression that it wasn't very forceful. Though physical violence and expansion was definitely an integral part of Chinese imperialism, for example the routine conquests of neighboring territories (often those inhabited by nomadic peoples). To me, the insidious nature of Chinese imperialist discourses that framed Chinese culture as universal and reduced the cultures of neighboring, smaller countries to the state of otherness was maybe its true strength. I am thinking in particular (pun intended) of a passage by Japanese feminist Ueno Chizuko:

Throughout Japanese history, "Japaneseness" has been constructed in the shadow of China, and this has given it an irreducibly colonial nature. Premodern aristocrats and intellectuals were necessarily bilingual, since much upper-class written discourse was produced in Chinese, not Japanese. China has always been an ethnocentric imperial state that has considered its own culture to define the borders of the fully human realm. Though sometimes conquered by nomadic tribes and once invaded by Japan, the Chinese have never questioned their own superiority and universality. With this overwhelming Chinese presence as a focal point, Japan has defined itself as particular, distant, and differentiated- put more simply, as inferior to the universal standards of China.

I sort of got the actual effects of Chinese imperialism and the reception of it mixed up, since I had in mind how Western colonial narratives (which dominate discourse currently and overshadow any vestige of Chinese imperialism) frame China as weak and effeminate and Chinese imperialism as ineffective to the point that people struggle to acknowledge historical Chinese imperialism as capable of doing actual harm. A common reaction to modern Chinese claims to the imperial legacy I see is to laugh it off as comical rather than treat it with serious concern. I guess within the Orientalist framework, China (or any “oriental despot”) was simultaneously strong and weak, always wanting to oppress but failing to do it successfully. Chinese imperialism appears mild to us now because Western imperialism said it was. This ties into the thing about how Chinese imperialism collapsed not because of anti-imperialism but another kind of imperialism, so many effects of it on neighboring countries and China itself remain unresolved tensions. Though again, I’m not professionally trained in this area of history so these are just my personal two cents, please don’t take my word for it.

84 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have sources for your hanfu vs. hanbok post?

(I really hope this was meant in good faith and not trying to start shit) For the history part I used these two sources: 1, 2. The part about the controvery itself is based on my personal experiences and observations so there are no sources for that.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

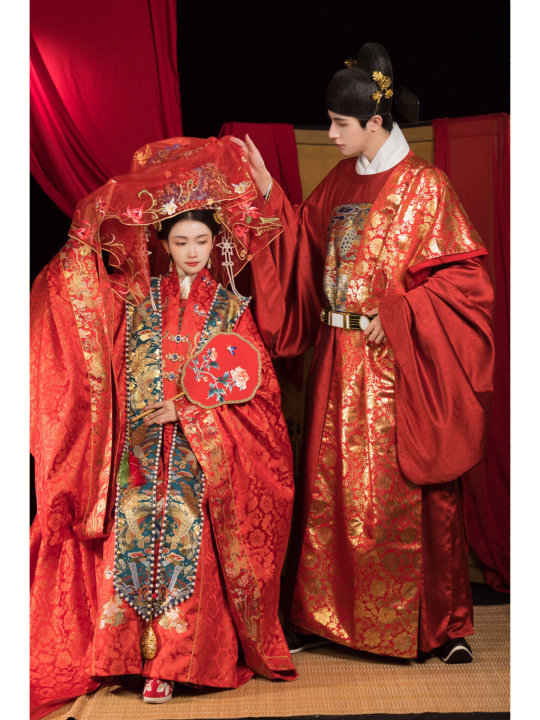

Ming Dynasty Wedding Hanfu Costume

via Yan Bin Sha Hanfu (砚滨纱)

218 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello. I'm in love with your work, it's all so wonderful. I want to ask: besides Chinese fashion, are there any fashions from other cultures and their histories that you like/want to learn more about?

Thanks! Theoretically, if I had unlimited time and resources, I would like to learn about all of humanity to be honest. Realistically because I barely have Chinese fashion from the Ming onwards figured out I try not to look at other places :)

25 notes

·

View notes