Science fiction, surreal, horror, fantasy, and other speculative short fiction writing. Read my novel, Children of Vale. All written text © 2022 Daniel Alan Anderson. None of the artwork or visual source material is mine; it is copyright its respectively credited artist(s).

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Every New Year's Eve the cryptid Gorgolan woke from his wintry hole. Unobserved, he would open his belly to the night sky. Legend said he feasted on starlight, but his true nutrition was unfulfilled expectations. He was a beneficial monster: nature's janitor of psychic energy.

–

Photo: Neil Rosenstech

#nye#newyears#cryptid#horror#winter#vss#very short fiction#very short story#writing#fiction#writing community#microfiction#forest#happy new year

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

My ego is a castle hiking its skirt up against an infinite tide, drawing in and out, like my breath. The air in my chest is an engine continuing a process I don’t understand, while some priestly caste proclaims its knowledge from the top of the castle’s spire.

But the priests are learned fools. They can’t fathom the silent knowledge of the tide; where it comes from, where it goes. Neither could they bridle it like a horse. Its strength is gentle but consistent. Its force is beyond their understanding: it needs no robes, makes no theses, requires no graduation, is beyond all measurement.

I can just barely cast myself out on this contrasting scene, like a gull watching from afar, and an even more awesome monster, the horizon. Somehow these pieces of scenery, though part of me, are also part of a cosmos I can barely comprehend. The pomp and self-importance of my own achievements seem then like a kind of luxuriously costumed jester’s craft—a guffaw; I laugh at myself, caught by the irony. It yields to a quiet humility, that then admonishes, like an old, wise friend: “just admire the scenery.”

Mont-Saint-Michel

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Traveler

A detail of the Gundestrup cauldron – Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen

Lines. Lines cut the sky but drawn by rain, drawn and quartered, lay unbloodied in a gray field waving grain-heads cumulonimbus. Lenticular. Mountain heights, rolling silently, whispered between each other, stalwart guardians of day but awful giants at night.

When my walking stick plunged into the dirt and jostled the loose soil, little rocks tumbled off the edge of the cliff. This path was dressed with moss, fronds, and little succulents that drank up morning dew too deep. You little desert flora—what are you doing so far from home?

I should've asked myself the same question.

The leather under my boots were worn, the cords coming unstrung. I'd have to take my awl and needle, weaving it through the soles of my foot.

Underfoot, somewhere, caves lingered, growing their own gardens of salt and calcium sans photosynthesis; mouths with slowly growing teeth, sealed shut, dressed with lips of moss I now trampled. It grew back, I reasoned, consoling myself. My bloody footprints—they wouldn't last long, thank gods. No traveler could be as quiet as these mountains.

I unsheathed the knife I cut my bread with and, bending down, picked a mushroom with respect, cutting from the stem so not to disturb its mycelia. It was a soft and tender horn springing from the ground; underneath, its little brainy veins whispered a dialect only Cernnunos knew. I tried my best imitation: wind dribbled from my soggy lips like crumbs and carved rivers through my beard-hairs, suggesting braids I hadn't bothered with that morning.

I looked back along the path I tread. Only hoofprints led to where I now was.

0 notes

Text

An Alcyon’s Funeral

Art Source: Dennis van Kessel - Lights in the Sky

The city's spires were raised by giants. At least, that's what the Alcyons told us. Their footsteps left stone columns in the air that were wide enough to encompass whole cities. And they did—at each segment's end that rammed into another, the resulting outcrops formed the base of each city's districts. The buildings were carved into the stone in the early days. These old towns, which were sullen and dusty now and, depending on which you visited, rife with crime—not the petty, pocket-stealing kind, but rather the plotting, well-networked kingpin kind—were largely abandoned by commoners and merchants. The newer additions were built out of those geological outcroppings with scaffolding, fanning out like spare leaves on an otherwise brutal trunk. Good thing that construction was light; the Guild of Carpenter's standards was written after the early days when collapses were commonplace, and now the cities lived largely in safety. There hadn't been a collapse in over two hundred years.

I stood on one of the cargo slinger's outcroppings—a pier for cargo getting zip-lined through the sky—and watched the lighting ceremony. One of our Alcyons, one of the eldest, had passed away in her sleep. They were once called Kingfishers, they say, and they were the keepers of our science, our religious oratories, and our mechanistic craftsmanship. Each district had its governor, and for each spire, the governors reported to their Alcyon. Altogether, there were seven of them, and they acted not only as final judges on legal matters and ultimate arbiters for economic disputes, but they were the preeminent philosophers, our final teachers. Alcyon Iluzia, who'd passed, was Alcyon of the Wind, our keeper of old histories and magics; she was arguably the most revered and respected on the council—if not for simply the domain of her knowledge, but her capacity to memorize it all. Those subjects weren't written; they had to be recited through oration. They said she accomplished it by architecting her mind like a carpenter architects a building—and without drawing a drop of ink, she could tell you the position and portion of any piece.

I'd never seen the cities from this angle. The night's fog rested below the foundational outcroppings. Every district was alight. The orange and yellow sunbeam glows from the houses, the temples of acolytes, and even merchant warehouses contrasted against the deep inky blue of a rising moon. All this activity, all of this mourning, collected the normally disgruntled and disputing districts into a single commemorative act. No cargo passed tonight. Lanterns lit the shipping lines themselves, where parcels would otherwise be hooked onto a sturdy black cable and sent zipping from one spire to another. Even if there was business to be done, the Alcyon's funeral took priority. All else waited.

Then the floating lanterns let loose. From every pier except for mine, perhaps, whole groups were let off the edge and into the skies. Whether they floated down into the fog or up into the ocean-colored clouds… they symbolized the Alcyon's thoughts leaving her body, and also leaving us, to be absorbed back into the world. It would be up to us to find the new Alcyon, recruit them, and then they'd have to absorb all the prior work of their predecessor, re-generating the knowledge that left. Somewhere, in one of these cities, they were just a child—maybe one letting go of one of those lanterns now. Did they know how their life was about to change? Hardly, I doubted. Going from a life of mining, textile weaving, or carpentry, to one of endless bookish learning and mind-numbing oration, would be a radical shift. When I became a cargo slinger, I had to defeat my fear of heights, of course—and after that, learn how to ride the lines myself, with little more than a hook attached to my wrist, learning to taste and enjoy the unscented fog, trusting there was a pier waiting for me on the other side. I loved the thrill now. But when I started, I hated it.

The lanterns were free. Bells rang. A distant chorus hummed from the temple minarets.

Time to find that child.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photo Source: NORIHIKO DAN AND ASSOCIATES - https://divisare.com/

When I was young, I used to love airports. Airports are transitory places. Everyone is coming or going, but they never stay. Those big windows open to the sky, covering us from rain, showing us the dull gray asphalt with the skid marks below; the men and women with the headphones to block out the sound of nearby engines, shuttling belongings, fuel, and food from place to place.

I loved it especially when the fog rolled in. It added to the mystery and the obscurity. You could see the headlamps from the planes cast a glowing, fading cone, or their little red and green running lights blinking in and out, like the glitter of fish in a cloudy sea.

But nothing stayed put. The only thing that stayed put was the buildings. The terminals, the carousels, the reception desks. Even the attendants checking you in or calling out names for the wayward seemed to belong somewhere else. Maybe they were. After all, they were just there for the shift; their role, like the buildings, was not to increase any kind of permanence, or add or subtract; it was to lubricate the procedural machinery of moving people and things from place to place.

So if I sat down there as a child and stared out the windows, or watched the people running back and forth with anything from a sense of bored malaise to urgent excitement, and pretended that I'd been there for hours, days, or weeks, it created a curious feeling: to be permanent in a place of impermanence. To be static in a place of endless motion and perpetual revolution. Was this the oceanic feeling? Was this what it was like to be a mountain under a dome of sky, or a diamond under a shifting continent? No one minded me. No one would scoop me up if I just stayed here. Sure, they might notice, or a stranger or security person might address me on an off chance, but never for long. They all had to go somewhere else, and so a connection was always cast under an umbrella of the temporary. Everything was fleeting; an RSVP, a rendezvous, another foreshadow for a junction later down the line.

As long as I sat put, like a rock on a shore, those waves of motion would wash over me. I was perpetual. Ever clean. Ignorant to all its meaning, but without a care; instead, just observing. Listening to the roar of a jet engine off in the distance, fading in and out, like a herald's trumpet signalling another transition for someone else.

Until a hand grasped mine, and it was time to go after all.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ilutrium Bazaar

Art Source: Yi Liu

When we arrived at the bazaar, passing through the Ilutrium gates, thatched together with balconies made of dried sweetgrass and timbers from river valley trees, my nose was overwhelmed first. Next, my ears. You could hear the market workers' cries of haggling over meats, woven textiles—and yes, slaves—far before you saw any of it. Once you did, the final sense to gorge itself was the sight of it all.

After days of traveling over sandy plains, overnighting in the next rocky cleft with an ancient cistern, we'd finally arrived in Ilut. Yadzi had never been, she said. I'd been once or twice, but it'd been years. It was famous for its bazaar. Locals said it started only after the spring harvest, before the summer scorched the crops. It grew so popular that it became a year-round event, drawing in merchant caravans from across the region. There were cooling ponds and misting fans in the main thoroughfares for potential customers, allowing them to mingle with sellers even when summer reached its peak.

I led Yadzi through the main avenue. Netting stretched over us, blocking out the sun and casting everything in criss-crossed, checkerboard shadows. The smell of roasted poultry rubbed in sumac and ground chilis made her eyes water. I loved it. I was used to tribal foods; for her, in the sheltered palaces in the north, the blandest food was preferred, with hardly any game: potatoes, peas, pressed hard-tack and wild berry jams. But my goal wasn't for us to eat our way through here, as much as I wanted to. We needed information.

Passing by one rug merchants nearly swimming in rolls of fine textiles, and asked him in my best Ilutian tongue:

"Which way to the center?"

"Vlep id elen adelem det," he answered in Frizian. Blue eyes stared at me from under chocolate-brown skin, wrapped up in sheer vermillion cloths. He pointed to the far right, down the avenue. "Apadep—apadep," he said, repeating.

Yadzi was behind me, watching a street conjurer disappear gold coins between his fingers and up his sleeve. A small audience offered bets in more of the same, gambling on how many he could handle at a time. I grabbed her hand. Pickpockets were everywhere here.

"Come on, this way," I said.

She followed me, ripped from the show, even as the conjuror grinned and spewed the previously disappeared coins from his mouth.

Ilut was a nation that was as advanced as it was arcane, as tribal as it was mercantile. They'd mastered electricity and magnetism long ago, but camels and rams were used alongside automated rolling carts. People wore waterpacks beneath their shawls. For every other charcoal-fired roast pit, there was a steam-powered conveyor belt that distributed wares from the center of the city to the market, which ran the whole circumference of the city in a ring. Along that ring, up above us, maybe the greatest marvel: a solar-powered monorail. It was open to the hot desert air, though, and being stuffed in a rail car was unappealing to me. We'd be traveling on foot.

"How far to the center?" Yadzi asked.

"If I remember right, and we walk fast enough, ten minutes." I kept her hand close to mine. "But don't let anyone touch you here. Pickpockets, and worse."

Her eyes grew wide and she nodded, pulling her scarf close over her chin and lips. I pulled her hood further down her forehead for her. Some of the palace's markings showed a little too easily; bright blue and pale yellow dots adorning her brows and along the line of her scalp. It wasn't likely she'd get recognized this far south. But I wasn't about to take a chance.

Some of the loudest cries of haggling off to our left. We opened to a clearing, a plaza, and the tan mud-brick walls were piled high, topped with turrets on either side. In the center of the plaza, a wooden stage, and on the stage a jester was playing antics in front of a line of half-naked slaves. Their downcast faces, darkened by the sun, were clean-shaven; all their scalps were shorn, male or female. A black cord strung them together from neck to neck, made of braided goatskin. Ilutian slaves were never chained, but this was more for the sake of their "protection" as merchandise rather than for their comfort. Slavers prided themselves in selling only the most "pure"—that is, unscarred. The jester's bright blue-green costume and exaggerated lacquer mask clashed with the inhumane scene behind him.

"Assholes," I muttered, pulling down the shaded lenses to my mask's visor. I tugged on Yadzi's hand. She was staring at the show, dumbfounded first, but with a touch of contempt curving her plump lips into a frown.

"Come on, let's go. We need to get through this crowd." She nodded quickly, without protest. The jester swallowed a flaming baton, then pretended to poke one of the slaves with its nub to the jeers of the crowd. He was promptly chased off by a man in a purple sash and turban. That was the slaver. He waved at the crowd, speaking first in Ilutian, then Frizian, and the crowd started to wave bidding papers.

"Can't we do anything about them?" Yadzi whispered to me as I pushed through the crowd of eager merchants, yelling out bids.

"The slavers? Yes—but not now. Not today."

I hadn't told her the story of how I'd escaped my slaver, how I'd managed to dip a grape in snake venom and serve it with the noon wine and snacks platter. I bribed the cupbearer that day, and bartered for the venom from this very market. I fed the morsel to him myself, popping it into his open, stinking mouth. Two minutes later, he was choking, then vomiting. Neurotoxins like that took longer to take hold when put in the stomach rather than through the usual snake bite or blow dart. I still got to watch as his eyes and face swelled though.

"We find the priest's secretary of the city," I said. "Then we get out. Let's linger here as little as possible."

0 notes

Text

Meditation for Mars

Photo Credit: Curiosity Rover - NASA/JPL-CALTECH/MSSS

When I visited Mars, the first thing I noticed—after we'd left the starport and were allowed to wander out of the tourist section and went hiking—was how familiar it seemed. Maybe it was the color of the sand, or the mixture of the rock that'd been broken up, I assume, by millions of years of wind. I wasn't a geologist or a planetologist; I was a student transferring from the University of Luna. But it reminded me of certain sections in Arizona that were preserved in the International Park system. Mixtures of waterless beachheads gave way to seas of dunes that invited comparison from other Earthly countries I hadn't visited: Namibia, Africa, or famous stretches in Jordan from old Earth movies. When I stepped forward, looking down at the bootprint through my screenglass goggles, I felt like I'd never left home. The land was the same. It was just the sky that was different.

We visited the usual sites: Opportunity's Grave, where the rover had given out in its mission and was later preserved in-situ; Curiosity's Dome—the more popular and crowded of the two attractions—which was dedicated to the sibling machine's long and storied mission, complete with a virtual pathway starting from its landing site in Gale crater to its current location where it sent its last message. It was on a dais that commended the spot, encased in a glass cube with pop-up infotainment graphics explaining the rover's features. Children would comment on how dumpy the thing looked—it was over two hundred years old and well broken in after all—while a few studied adults with potent Martian pride would actually shed a tear or two as if they were visiting the final resting place of a long lost friend. I was impressed, but the exuberance and touristy-ness of the location wasn't my taste.

Instead, it was the landscape that did me in. Once we got past the outer districts of Polis Mons, a megalopolis that encircled the whole of the Olympian mountain from which it inherited its name, we got to the un-terraformed reaches that evoked how Curiosity or Opportunity might've first seen it. But even then, towering solar collectors, shaped like artichoke flowers in bloom, dotted the distance in a concerted pattern that ruined the horizon, and moisture catch pools surrounded their feet, reflecting Sol's dull red light through hazy sky.

I wondered if there was a semblance of what old Earth explorers felt in what I was feeling: something like arriving to a paradise lost only to see it'd already been found, labeled, and catalogued. Earth was fully inhabited even in the colonial age. There was nothing to explore, except possibly by Shackleton, Amundsen, or Peary, that hadn't already been someone's home. Even the Vikings who sought a new home in Iceland found that Irish monks had already made the trip. Colonial exploration was really just an exercise in break-in and burglary under the pretenses of nationalism, discovery, and Manifest Destiny. Misguided, so often. What were the befuddled looks on the denizens of Hispaniola when Columbus asked the way to Bombay—to say nothing of the looks that must've been written on his own men's while they wondered if these people were the same Indians they traded with on the Silk Road?

But Mars—Mars! For a time, only a machine had touched its surface. Like a flag planted, but still a hole instead of a footprint… Curiosity's tread tracks left a lasting impression, along with its boreholes, and the pieces of its broken wheels that got left as the first ever Martian litter since the ancient seas dried up and the jellyfish evaporated were preserved in place like Aldrin and Armstrong's bootprints were on Luna; they were their own tourist attractions now too. But at least with robots, there was no one to miscommunicate to nor ears to misinterpret. No unsuspecting audience to pillage, no delusions of glory. No—Mars, at least then, was pristine. The fossilized flora had long since shriveled away and the bacterium that could kickstart life elsewhere never made it far enough off the ground to participate in the panspermic drama that was the Universe's conspiracy to life.

No. Mars was long since cleansed—cleansed by way of rust, cold, and salt. It would take two more centuries after Curiosity for us to leave Terra Firma and bring our neuroses, our bickering, and our grievances to the sleeping god of war and his unblemished deserts. These places—these dune oceans, under pink-orange skies and tan mountain ranges with blackened tips in the distance—they whispered a solemnity to me that even Luna couldn't match. Luna was extreme: extreme heat and light in the day, extreme cold and shadow in the night. But Mars was like Earth… just without people.

What a dream that would've been: to see it as the rovers had seen it… as pure-spirited entities embracing a pure-void land. Humanity had to live, I suppose, and we'd soiled our womb too much, so it was inevitable we'd come here—but that seemed like such a base reason for a monstrous human zoo and theme park like Polis Mons; as base a reason as eating, sleeping, or defecating. Of course, we insisted: a whole new planet, just for that. To start again, now more evolved in our technology, but none in spirit.

I imagined, staring at my bootprint, then back at the horizon, an alternate reality where none of it happened. That these mountains could still whisper to the sands, and the deserts could whisper back, in confidence that no one—not even me, as much a lonely student as I was—would eavesdrop.

0 notes

Text

Photo: Tuareg participants at Festival de l’Aïr – moula-moula.de

When we arrived at the desert camp, it was noon. The elders were already there to greet us.

"You brought the girl?"

"Yes," I said, motioning to Yedsi, who stepped forward.

The elders were in their traditional dress. I'd never seen it before. Sheer black and mauve fabric, loosely draped around their bodies. They almost glinted lavender in the high sun. Their faces were occluded. Some had a slit across their headdresses that revealed their eyes, but when the foremost elder approached, he didn't have even that. Completely covered, except his hands. Gold sword at his hip. Bronze staff in his hand. The white plume of fabric that encircled his head reminded me of some kind of halo.

These Zabrune were keepers of old desert traditions. They'd been persecuted and hunted for their nomadic ways until they were pushed into a small corner of what had otherwise been an open sea of sand, dotted with fertile oases.

"Bring her closer," said the elder, waving his finger at me in an unfamiliar gesture. His voice was rough but not hoarse; it reminded me of wind rustling through a cleft in rocks—almost like a whistle.

Yedsi stepped forward. I didn't bind her like the mercs told me to—not after the cave, when she saved me from the Heela lizard. It was my job to care for her, not the other way around. But she could suck poison. I had the roads out of the caves memorized. We traded.

She didn't look at the elder. Fear? I wasn't sure. After two weeks hopping from oasis to oasis, I watched any fear she'd had when we left steadily drained from her eyes. She was comfortable on the camel now. I even… liked her? Were we friends? That's dangerous—to let friendship grow in the soil of what should otherwise be a quick and dry contract.

But that wasn't what this was anymore. The elder flicked his finger at her.

"See my eyes," he whispered, and he lifted his veil. Yedsi looked up. The elder's eyes were painted on his lids. He didn't open them. Instead, looking at him, all I saw was those chalky white almond outlines, with dots in place of pupils. His cheeks were sunken. His lips parted slightly, revealing bucked teeth with wide spaces, but immaculately clean.

I looked at Yedsi. For the first time I saw an emotion hover on her face I hadn't seen before. Hope?

"Yes," said the elder. "It's her."

The members of the party shook their staffs, spearing the sand, causing it to stir and tremble. Murmurs and quiet whoops floated up from behind the headdresses. Bangles jingled, echoing a subdued excitement.

"Let's go back to the cavern with her," the elder said, nodding. Then he turned that wagging finger to me, saying:

"And bring him too. He has a part to play now."

More bangles shaking, more whoops. That wasn't part of my plan. My plan was to go back to the citadel to collect.

"I'm sorry but—no, I can't."

"You will come with us," the elder said, flicking those chalk-eyes at me. Did they burn into me like any glare could? It felt like it. "The desert will not be kind to you. Mother Shin will block your path. I see—" he gestured to his eye, "that your mission is not done."

Yedsi looked at me. It was a knowing glance. She wasn't surprised at all; maybe she was even pleased. But resigned. It begged me to go with the grain. The Zabrune were not kind to strangers who refused their hospitality. Insults stuck long and hard.

"Come," he waved his hand again, and the assembly turned to go. An attendant grabbed my arm. "The desert's daughter is returned, and her guide has a part still to play."

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

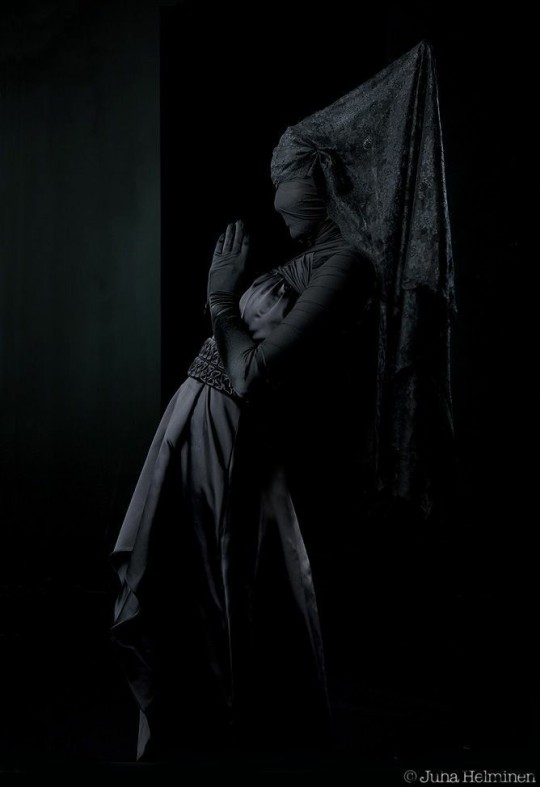

City of Arnock

Photo Source: Juna Helminen

The city of Arnock has layers, layers which are not quickly understood or noticed. Superficially, it appears to be like any other city. It has shop keepers, barbers, thoroughfares, and government buildings that evoke Victorian flair, but in an era where electricity was accessible. It’s a seafarer’s town. It sits on a plateau overlooking the ocean, and its lower districts have ports that jut out from white cliffs. Taverns hum there with the clink of glasses and the din of poorly tuned accordions; whalers swap stories of sea monsters and Flying Dutchmen, and each time the monsters in the tales grow larger, many-headed, and the Dutchmen fly higher.

Arnock has an administrative side, implicit for any town with economic power. The oil extracted from the blubber of sailors’ catches churns mills which, when combined with a kind of magnetized fan, generates electricity. Arnock would’ve been Tesla’s city, even prior; you could say it was a forerunner, and it was by this electric power, gifted by way of the sea, that it cemented its economic place.

Few understood this new kind of energy and Arnock’s own architecture spoke of a different era. Fashion and decor hadn’t yet caught up with the offerings of automation; women still wore hand-embroidered clothing, and fine china was made by journeymen who sought to imitate the work of a master. Electricity and magnetism might as well have been magic to its common residents. An aristocratic class kept a close eye on elite and eccentric inventors who could repair and manipulate it.

But as happens with inventiveness, and the curiosity of wandering minds, even the obscure is entertained for possibility’s sake. This gave birth to Arnock’s other, more arcane layers.

Every good city, like every good person, has at least one finger planted in some kind of muck. A plant won’t grow without fertilizer, and a tree’s canopy only reaches heaven insofar its roots scrape hell. For Arnock, this spectrum evoked practices that the seafarers shunned for fear of bad luck, and the aristocrats conversed over in their absinthe parlors late into night. Below the administrative districts and the markets, with all their fruit carts and butcher stalls otherwise free of flies, rats and ravens ran rampant in sections of the city carved out by old coal mines. This Old Arnock, which was reputed as the place for smugglers and renegades, was where a certain kind of cultist gathered.

It’s hard to tell exactly what these cultists believed. I’d barely reported that they existed by the time I got out. But it may’ve been that, like the district itself, they took whatever Arnock had above them and simply inverted it. If there was a ball, dancers wore dresses front-to-back, and men and women switched places. If there was a masquerade, the masks would be worn in the back of the head, or upside down, so that a smile would become a frown. Meals at either kind of event was served dessert first, and if antrilom was served—a kind of haggis involving a fish’s swim bladder—the bladder would be first turned inside out. Music would be played backwards, and partakers would have to count their footings in reverse.

There was something about it all that was unsettling, knowing that there were whole groups of powerful people living luxurious lives, possessing the power to do everything they did otherwise, but backwards. They could take a mirror to themselves and their beautiful city and invert it just as easily as they played the part of the forthright. There wasn’t a desire or effort to resolve this opposite—just an immaculate method in portraying it. I’m not sure which disturbed me more: the portrayal or the lack of its interrogation.

So, with that salty sea smell in my nostril, there accompanied me a kind of unsettled ambience whenever I kindly bid the market stalls a good day, passed through the taverns, down into the Old Town, where the mice scattered over wet cobblestone, and I could hardly tell the cry of ravens from crows. I rendezvoused with a man who had a scar on the left side of his forehead, and he’d tell me the story of his dinner the night before; I couldn’t help but notice his scar was now on the right side of his head. A left-handed perfumer with too much makeup would mix a fragrance and hand me back my change with his right hand instead.

Arnock was a town of opposites where people lived double lives, confessing democracy in on side of their mouth, then subverting it with the other, providing the inventiveness of one hand by way of clean academic science, then dabbling in things that reeked of dusty books, wet-ink sigils, and dried blood in the other.

I left after a year. The stink of its lower levels didn’t leave me even when I hung my foot off its piers and dipped my toes in its ocean. Gull cries mixed with caws of crows. The whiff of last night’s absinthe mixed with my latest cologne. In the background, always: that smell of whale oil—blubber. As much as they tried to hide it, it went everywhere.

I struggled even as I settled in a village to the north of France. A blackbird was sitting in a tree outside the villa I stayed in, and I cursed at it when I thought I heard the sound of its cry ringing in my ear in reverse, like it was replaying a record wound counter-clockwise.

I tried to write my thoughts down in a journal by the suggestion of my therapist. My hand started to shake when I realized that I’d written it backwards.

0 notes

Text

Photo Source: Matthias Heiderich

I gripped the rusted railing with an ungloved hand. The snow crushed beneath it, melting; first crisp, crunchy, slowly dissolving into slush, then dripping down between my fingers. With each step up the stairs it piled in the hollow of my palm and rode up the connecting web between my thumb and index finger.

That moment when cold things get so cold they get warm. Like the nerves are overloaded and can’t quite tell one end of the spectrum from the other; snakes woven over my veins, swallowing their own tails.

Step. Same sensation underfoot, but obscured by the wide rubber pad glued under my shoes.

Pausing, I looked to my right across the snowy plain. All of this steel was silvery once. Now it was burnt like a sunset. Oxidation: signs of age. Rust. Metal eaten away by the most ubiquitous mixture: water. All things change, all things flow—panta rhei.

Would the structure change if given enough time, too? Like a rusted car made of sheet metal, how its outer skin earns negative outlines the way puddles shape on the ground? This building—would it earn pockmarks like a molding loaf of bread, negative space formed by liquid raisins in a piece of bran, if let alone long enough?

Cold. Time. Age. Space. All of it—process, and the sensations are just snapshots on a rotoscope spun on an axle that has no name.

I started to salivate.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Conjunction

On a rare stellar occasion, two gods, a father and a son, discuss the merits and flaws of the human race.

Also published on Medium

Source Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute. Photo manipulation by author.

The old man was a haggard, sickly father who’d long since abandoned his sons. His shoulders were hunched inward, but his belly was swollen, veins visibly drawn across his stomach, and it stirred with kicks like the womb of a pregnant mother. He sat at a workbench with a butcher’s cleaver, hacking at a meaty haunch while a vulture looked on. The barn door was open. Outside were his fields; they’d been left unplowed for years but were nonetheless full with grain. His scythe sat in a corner, rustless but always wet, ever sharp.

He paid no mind to the storm outside. Rain beat on his barn’s roof shingles, and its rafters creaked in the wind. A crow flew into the open window looking over his bench, resting on the sill. Its inky feathers burned blue against the light of his oil lamp. It cawed at him.

“Leave—shoo,” the man said, and he waved his cleaver at the crow’s feet. It hopped, landing back on its spot with a flap of its wings. It cawed again and cocked its head, turning. One of its eyes was whitened, blind. The vulture, sitting idly, squawked back—a glottal, halting cry. The butcher stopped his grizzly work, studying the crow and its plumage.

“Leave me, Graybeard.” He gave the haunch another thwack on the cutting board. “This one wasn’t yours.”

The blackbird looked at the meat on the board, eyeing the vulture, then the butcher. It flew off, cawing into the distance as it did.

The man plucked up a piece from the knife. He threw it at the vulture, saying:

“Mimas—here.”

The vulture caught the piece in the air, quickly gulping it down.

The rain continued to pour, and he felt its dampness underfoot as a stream trickled over the foundations of the barn, licking at his toe. Distant thunder rolled, but the man paid no mind. He continued to cut and savored a morsel for himself, gobbling it down like the vulture did.

“Fodder for my stirring sons and daughters,” he muttered, licking his lips. “Stay placid—save those kicks for each other; spare your sweet father.”

Thunder cracked again. This time lightning lit up the barn’s interior like a magnesium flash. He dropped the cleaver and it clanged on the floor. He swore in his mother’s tongue and recomposed himself, picking up the knife again. Looking behind him to the barn's entrance, he saw nothing but his open fields under gray skies. He turned back to his workbench, wiping the knife down on his apron.

Another lightning flash, this time off in the distance. But its light cast a long shadow across the far side of his workbench and up the wall. He looked over his shoulder to see the silhouette of a tall, built man with streaming locks and a beard. Some kind of bird was on his shoulder—he didn't bother to see what kind.

“Leave me,” the butcher snorted. “I already told your hoary fortuneteller of a father that I didn’t harvest his bloody einherjar.”

The bearded man strode into the barn as the butcher picked up his cleaver, swinging it down into the meat. It sliced effortlessly, quivering as it struck the board beneath.

“You mistake me.”

Instantly, the butcher recognized the lilt in the man’s voice. It didn’t belong to the crow's master—this was an Aegean accent. He turned. The man’s hair was dark like oakwood, not blonde, and was thick and curly, his skin olive-colored. His irises were bright pale: electric storm-gray. The bird on his shoulder was an eagle.

The butcher grunted: “Jove, my boy.”

“Saturn,” the god nodded, then adding, “—father.”

“On what occasion do I owe this visit?”

“Our great conjunction. You are the cosmos’s timekeeper, aren’t you? Surely you out of anyone would know.”

“Ah—our conjunction,” Saturn mumbled, raising an eyebrow at the syllables. He smeared a bloody hand on his apron and fumbled in its pocket. He pulled out a timepiece and flicked it open. Its face held a hundred hands at a hundred different axes, all rotating wildly like the stars in the sky. “How could I’ve forgotten… of course.” He flicked the pocket watch closed and dropped it back in his pocket.

“We’re the closest we’ve been in over half a millenium. Last we spoke, the claymen, our humans, were building houses out of thatched grass and nestled stone. They’d just nearly mastered war and had gone to slaughtering each other en masse.”

“Of course,” said Saturn, grinning from beneath his dirtied beard and mustache. “I’ve barely had to plow my fields since then. Easy harvests.”

“They’re exploring their world. Soon they’ll cross seas instead of just rounding them. They’ll build empires that stretch from one side to another.”

“Sounds like more war to me,” Saturn said, turning back to his cleaver and meat. He noticed Mimas studying Jove’s eagle. “My bales will continue to be thick—which I prefer.”

“But you can’t deny their ingenuity,” the thundergod responded. “Millennia ago, no more than our hands have fingers, they were children with sticks and fire. Now they model themselves after our courts and speculate on our true nature. Don’t you have any opinion on their future? After all, times are few and far between that we get to discuss them so intimately.”

“My opinion,” Saturn muttered, the end of the word cut off by the thwack of his knife on the board, “—is only as deep as the roots of my grainstock. Only as complex as my hunger. So long as they continue to sacrifice, ignorant of why or not… that is my investment.”

Another thwack as he focused on his butchery. He continued:

“I wonder at your fascination with these creatures, boy. I think even the Aesir only care insofar the offerings are sweet. Speaking of—care for some?”

Old Kronos held out to young, glittering Jove a blood-soaked lump of flesh. Jove’s mouth dipped in revulsion; he waved it away.

“I don’t share your appetites.”

“Of course you don’t.” Saturn threw the piece to Mimas, who gobbled it up like he did the last. “But you have others. These clay men and women are as much your playthings as they are mine. Your choice of play is simply… different.”

Jove’s eagle gave a cry out at the vulture, who squawked back like he had at the crow.

“I’m not here to bicker over our differences,” Jove said, ignoring his father’s insult. “I’m here to discuss their fates.”

“What fates? Different than us gods?” Saturn sneered as his cleaver let loose another thwack on the board.

“You might be disinterested, but I’ve seen their work up close. They may live as long as mayflies, but even now, they’re bursting at the seams of their planet. It won’t hold them for long. Their powers are simple, but the arrangements of their tools grows complicated. Soon they won’t be content to cross the seas enclosing their land… they’ll want to cross vaster seas: the seas that enclose their planet—even the seas that enclose their minds.”

“Damned titans loosened the box and let wildfire run amok,” Saturn said. “Let the clay entertain itself. Who am I—or you—to interfere?”

“You don’t think their empires would impinge on our own, at worst? Or, at best, they might have something worthwhile to add to us as allies?”

Saturn snorted at the word, but said nothing. Jove continued:

“They love, hate, and bicker like us. Their microcosms are merely smaller than ours—but those boundaries grow thin. Sticks and fire were their beginning, not their destiny.”

“You sound like you admire them,” Saturn said. “Are you so quick to get over Prometheus’s duplicity?”

“I admire their ingenuity,” Jove admitted with a shrug, “…their cunning, their persistence—even a god can evolve. Maybe you should consider it as a strategy. It might serve you well someday.”

“I am old,” Saturn growled, letting his cleaver rest on the board. Mimas shuffled on his haystack, still watching the eagle. “I'm older than you. And let me tell you something, Zeus, god of thunder: when Pandora spread her box's lid, it upset more than the balance I’d instilled since before you were a stone and just as dumb. The rings on my orrery are carefully weighted. The slightest change brings disruption not just to me or you, or even the world of petty humans—the whole cosmos tilts, and worlds with names they barely know will slide off the table. Gods don’t feed off Earth alone, but few places pose such risk. Do you know the balance I had to maintain, that I still maintain? A wayward titan or giant here or there grants a lump of dirt a lit arrow and suddenly they’re jumping rings on my timepiece, planning vacations to Luna for a thrill—“

He slammed his cleaver's blade into the workbench, its handle erect; Mimas’ wings fluttered as Saturn roared hoarsely:

“If you had a care for either god or human, you’d think like me, and maintain the balance that persists as I do. Instead, you instigate, you whisper sweet nothings in their feminine ears and grant fateful boons by way of your own ineptitude. Your thunderbolts aren't flashes of genius; they start fires at random. You’re a rebel, a chaosmaker—not a ruler. A king applies laws, he governs. By that standard, your brother Pluto would be a better caretaker than you.”

Jove had his arms crossed, and Saturn was secretly impressed that his son hadn’t lunged at him already. Instead, the Olympian let his eagle off his shoulder, where it flapped its wings and nestled itself on the ground. Saturn added, his tone more even now:

“I am the cosmos’s timekeeper, boy. My accounts are carefully measured. The humans won’t ascend to godhood like you surmise, despite your minor insurrections and naive hope. They are too petty; their own technology eclipses them. If you think their spirits can evolve as fast as their ability to wield various forms of fire, you’re as deluded as they are.”

“Then to what conclusion, this experiment?” Jove asked. “They’ll just consume themselves? Evaporate in a fit of self-annihilation?”

“Of course,” Saturn said, removing his cleaver wedged in the bench. “Gaia will survive even if humanity doesn’t. She is a hardy ground and even more inventive than them. Clay to clay, dust to dust.”

He heard Jove shuffle to the edge of the barn door’s entrance. He could make out his shadow leaning against the frame.

“Say what you say happens. Who will offer sacrifices then? Whose souls will grow as grain in your fields?”

“Gaia is inventive, I already said,” said the harvest god. “Some other clayform will come along while you still walk, I’m sure.”

“And say what you say doesn’t happen. That my naive optimism in them isn’t misplaced—that they do jump your rings, that they cross our skies, and even harness my thunderbolts. What then? What will be the nature of your harvest?”

The vulture squawked at the eagle who stretched his wings wide at the barn’s entrance. Saturn plucked another piece from his board, ripping it between his teeth.

“Why shouldn’t you be worried too, in that case?” He finally replied, chewing skin. “They’ll forget their sacrifices and fancy themselves like the Titans did. On that day I’d imagine you’d come to my side, ready to settle the score.”

Jove nodded, looking across his shoulder to the grain fields outside. Saturn held his cleaver and cut carefully, his knife cutting its way around a thick bone.

“Wouldn’t that be fitting?” Jove said. “They had a genesis once after all, and so did we as gods. That was counted by your orrery even before you made it. Perhaps their fates are set in stone too. I’m sure you could ask the Aesir about that.”

Saturn turned on his bench, letting the cleaver slide in his hand. It nicked the bone.

“Meaning, boy?”

Jove’s glance nestled back on Saturn’s, and his eyes crackled:

“It would be so godlike of them to surpass us in the same way I surpass you.”

The cleaver ripped from the bone and, with barely a thought, flew from Saturn’s hand. Its blade whirled in a tight orbit, headed for Jove’s neck. There was another magnesium flash, and Saturn was blinded briefly. Blinking, the lightning’s afterglow drawn down his sight like a neon vein, he looked for his wayward son.

He didn’t see him. Instead, he saw the oak-colored wings of the eagle in the distance, flying across the grain field. There was a glow beneath its wings on the horizon. Saturn blinked again—the lightning strike had lit the fields aflame. Fire fanned upward even as the storm continued to pour.

He got up from his bench and passed the barn's threshold. The cleaver was resting just at the edge of the field where he’d flung it, but it had hit nothing but air. It still had fresh blood from the cuttings on his board. He picked it up and wiped it on his apron, looking to either side. There was no one. The eagle in the distance was a fading speck; thunder rolled on.

Saturn turned to go back to his work. He heard the distinctive caw of a bird, but it wasn’t from Mimas inside. He looked up and saw a raven sitting atop his roof’s shingles near the weather vane. It croaked again, turning its head to look at him. Its eye on that side was blind, as white as snow and as blue as ice.

Saturn sneered at it. The raven merely croaked again, then once more, as if in a laugh—then lifted its wings and left. The wind changed as it did, and the vane swung the other way in the storm.

Saturn reached into his pocket to pull out his watch—then hesitated, and stopped. Instead, he grasped his cleaver and went back inside to finish his butchering.

Text © 2020 Daniel A. Anderson

#fiction#short story#shortstory#saturn#jupiter#conjunction#greek#roman#norse#mythology#speculative fiction#2020

1 note

·

View note

Text

Art Source: Eugene Boodnik (Stereozont) – Operation Juno's Rosehip

Snow. Just endless snow. It was colder than the shrapnel in his gut, but that was getting cold too. He pulled himself forward while grasping at the snow. He could see the smokewatch tower off in the distance with all its flights of stairs, leading up to the lookout.

The sound of scramjets overhead rumbled his helmet. Its metal neckring jingled like a bell, filling his ears. Was it loose? He checked the vital readout on his wrist: seventy percent seal. He would loose oxygen in five minutes.

He looked behind him. At first he wasn’t sure if he was bleeding, but the scarlet trail behind him evaporated any doubt. Damn, he thought.

Another roar—another jet. Was it theirs? Was it friendly? No way to tell. This blizzard he’d crashed into was like a fog. Something had hit him from behind and he ejected, feeling the explosion propel him forward just seconds afterward. Must’ve ripped the parachute. World went spinning; he could just make apart the blanket white-gray of skyfog from the glittering snow.

Should be thankful for the powder, he thought. Probably cushioned the landing. Without it, he’d be gone for sure. Too early to tell.

He’d have to communicate the signal some other way. Getting to the smoke tower was the best way, but as he checked the distance, another thought came. Too little time. This crimson trail would end before he got to the tower—and by then, his doubts reasoned with him, he wouldn’t make it up the stairs.

He rolled over, checking his suit. He could see the gash. Yep—was bad as it felt. He relaxed—let his helmet sink into the snow. Felt like he could make a snow angel laying there on his back, but didn’t move; looked up into the dull-gray sky and saw a hazy sun staring back down at him, misty, diffuse through all that frozen rain.

He looked to his left. In the snow was a grassy twig, nearly within his reach, a striking, vein-like shape against a barely discerned horizon. A little red bloom rested on the tip of its branch, refusing to succumb to the cold. How brave, that little bloom, spreading its bit of color out in this cold waste.

He heaved a breath. Fumbling at his flight suit with his right arm, undoing a strap, he fished out a smoke flare.

Light—the hiss from the can mixed with the whining growl of the scramjets making another pass above. They’d see him: a black T-speck on a blanket of white, rooted from branches of streaming red, at the center of a growing sanguine cloud.

That cloud, a thick strawberry haze, wrapped him up with the little bloom next to him. How fitting that they were the same color. They both fought for life—and both victorious, in their own separate ways. How sweet that color tasted.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art Source: riasteria – Link

When I touch the plants, I can see their life pass through my fingers. It’s like an aurora, phosphorescent, swimming; my fingers go fishing for light, and the tingles mix in my blood.

A spark; is that life? Gone, in a flash. On a loop. I could do it since I was a child: feel the plants breathe. Plants, most often. Sometimes fungus. Occasionally a fish. It works on coral, I found, when snorkeling at night. Best when I’m skinny dipping and the moon is out. I’m not sure why that is.

The more I let it dance, the more it glimmers beneath my skin, and the more I’m afraid I’ll loose myself. But if I keep it at a steady pulse rather than climbing to a climax, the glimmer is more than just a glancing ride—it’s a language, a poem. Some kind of dance of deoxyribonucleic acid. It’s the deus and the nucleic that does it—a nuclear god, divinity in explosion.

So I sit in the fields and wonder: who gave me this gift? How should I use it? When I sift the grass between my fingers, like a comb in my hair, it grows longer. Stalks sprout buds, buds bloom in radiance.

But it’s always at night. Never in the sun. I don’t know why that is. Doesn’t matter if the moon is waxing or new—but even sunrise and sunset is a muzzle. My firefly conversations with chlorophyl fade in radiation. I’m some kind of cosmic mother, powered by all that’s lunar, caught in the body of an earth-girl.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1969

Acrylic on paper mounted on canvas

Sanguine over rust-black, cut into the paper, swaths, swatches, made of steel.

Rain on the metal was soft under my fingertips; it made them cold. The colder it was, the warmer I felt. Something about wet metal, knowing that a simple chemical ate away at a hard thing. I was that simpler part, soft and squished, enclosed in webs of cells, layered and woven. My chains were chromosomes, bound by proteins, rusted only by time and their incessant need to copy; response to radiation, broken apart, rewriting themselves from blueprints they all shared freely. Hemoglobin: rust in the blood. I nicked the skin, and that rust flowed like fluid. I’m half metal, half water; black-in-red, red under black.

At my edges it fades, and beneath the rice-paper-skin is blazing heat. Bits of blue are hidden under there, only visible if you place me where I don’t breathe. A condensed sky-blue. Shine a light and it’s all just a tire-slick in the mud, ready to sift into minerals, into plant roots; a desire to remember, but like a shopper on a spree with just one more thing than he can carry, dropping the last. I’m not a container—I’m a vessel. For every breath I run out of just a bit more space. And in each heartbeat, another cell is carried with the stream, replaced by a more inexact piece: a copy of a copy, trying to remember itself from yesteryear, passed just a pulse ago.

I cut a finger on the color and risk tetanus. Tisk tisk. I sip it to clear the wound; autovampiritic.

0 notes

Text

Hybridism

Art Source: Eugenia Firs - Alexandria

A hybrid wasn’t the same thing as a human with a mechanical augmentation. It was common to have alternate limbs, either to counter a disability or to extend a pre-existing ability. Prosthetics, after all, had been around for millenia. What made a hybrid different was that it wasn’t just their body that was modified, but their consciousness. Hybridism was a punishment reserved for convicts.

The Accord of Consciousness specifically forbade humans mindsharing with dominant, artificial egos. It was agreed and signed onto by all post-nation-state entities after disastrous experiments that led to derangement, hallucination, and brain-death, after which it was enforced by all major players.

Of course, the fine line between a hybrid and an assisted, natural ego was difficult to determine. After all, didn’t most citizens mindshare with a programmed intelligence of some sort? The authors of the Accord maintained that the “wholeness” of human consciousness was reflected in the relationship of the body-brain system to the augmentation, and thus modifying the biological portion beyond a certain point would yield a different kind of organism.

In truth, it was an issue of rights and privileges. If an organism is hooked up to an apparatus that keeps it in constant conversation—and that conversation is one in which the human portion can’t get a word in edgewise—can that organism make decisions wholly on its own volition? And if it can’t, is that organism still human? The contract between assisted humans and their adjunct egos was voluntary and could be opted out of at any time. There was no such voluntary condition in hybridism. Hybrids could be hooked up to a network against their will with no right afforded them to protest it. They might be aware of their choices, but they couldn’t control them. They might have an experience, but it would be truncated, like seeing through a dim peephole. Perhaps, by force of sheer will, they could dredge up one impulse while suppressing another. It depended on the degree to which they were modified—and so there were many gradations of the procedure, often doled out according to the degree of punishment.

This gave detractors of the Accord leverage in the debate: after all, if hybrids have an experience of suffering at all, aren’t they still sentient and worthy of compassion? If the point of penitence is to cause suffering for a human ego, doesn’t the ego have to remain human to make recompense?

Those in favor of the Accord argued that it was a distinction without a difference. The procedure was permanent, so recompense was unremittable for a hybrid. As such, hybridism among those who signed onto the the Accord was reserved for individuals who would otherwise get a death penalty, and they were deployed to do menial tasks like guarding citadels, mining in dangerous conditions, and scouting treacherous terrains. These were human willpowers held in mechanical limbos, leftovers or even recombinations of many, woven by something alien to them and inserted against their will into a new body by a powerful third party, puppeteered by superconsciousnesses that commanded them beyond certain thresholds of otherwise natural will.

The condition was similar to an addict’s, but without the chemical dependency. Instead, the impulse was programmatic, instinctive, and predictable. If a hybrid was owned by an enterprise, it might be forced to do things that its human portion might not agree with—of course. But that always left the possibility that the hybrid could be manipulated by a yet more invasive force, like a being cursed with an induced alien hand syndrome from multiple puppeteers. So there was always an air of suspiciousness about them that added to the punitive stigma: after all, if I’m induced to serve a mental master other than myself, isn’t it possible that I could be induced a second or third time? How would an observer know my real allegiance?

So detractors of the Accord of Consciousness often hacked hybrids in an effort to “liberate” them. Freedom fighters insisted by the Rights of Compassion and Sentience, clauses within the Accord itself, that hybrids should either be destroyed or made wholly human again, if not banned outright. Since the procedure was supposed to be irreversible, they usually pursued the former strategy, viewing it as euthanasia. Whether their latter attempts at disentangling the human psychologies implanted in their mechanized carapaces were successful or not was up for debate with no clear winner on either side. But it was clear that once the process of hybridism was invented, it was possible to have gradations of humanity, gradations of free will, and thus degrees of rights. Those who lauded the Accord proposed that those who deserved hybridism had already given up their rights and privileges by committing atrocities against other free, humanborn agents. But the mandate of who judged this ultimately fell to the powerful, regardless of whether their decisions were justified.

#writing#prompt#dystopian#posthuman#scifi#sciencefiction#robots#cyberpunk#philosophy#consciousness#worldbuilding

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunrise in Vetreun

Art Source: Annibale Siconolfi | Inward - Urban Dream

Sunrise in Vetreun was a curious thing. Urban chasms allowed light to filter down to even the lowest levels. He would climb outside during the mornings to catch the first star’s light as the planet rotated. Theirs was a binary star system: the first, a yellow dwarf like Sol, was the closest, and to a tourist from Gaia would’ve seemed the most natural. But Angrabotha, the red giant, would rise first. It was distant, and so appeared much smaller, like the size of a moon, but every two years the stars would switch roles, and Varbauthi, the main dwarf, would appear to be the same size as his stellar daughter-in-law, shrinking smaller and smaller as she swelled in the sky like a monstrous egg.

During those biennial winters, Vin would hang from the rafters that crisscrossed between the chasms, much like how those steel workers in Philadelphia and New York did in the archival footages. How nice that must’ve been—to climb an under-construction skyscraper, metal girds the only enclosures for an urban organism’s ribcage, pull open a lunchbox, and laugh at the antics of traffic down below. Horses pulling buggies, mixing with Model-Ts, trying to sort out for themselves who went first; drivers complaining about horseshit on their brand new wheels, the sound of engines scaring the animals. At least, that’s how Vin thought it must’ve been.

Here, in Vetreun, a big city, there were no animals. But they did have the skyscrapers. Instead of horses and beasts of burden they had trees—trees did the vital work of making air breathable, and so were precious and expensive. Vetreun was in the business of making oxygen, and on Lodesea, an arid planet with two moisture-killing stars, water and its chemical components were chief capital.

He tapped the visor’s setting on the side of his mask, switching from infrared vision to visible light. Varbauthi was rising, spreading golden light down the chasm. Trees dotting the terraced buildings were already washed in ‘Botha’s reddish and lavender glow, giving the crevices between urban modules the appearance of ruddy fur between bones. Lights in windows flickered on. With the rise of the second sun, the city proper woke. Early birds and laborers like him were already up—for them, first sunset was the signal to start. But he didn’t mind the early hours. He liked watching the lightplay between two alien stars on this colonial planet. He’d remembered what it was like on Gaia as a boy. Sunrises and sunsets were straightforward, simple. At noon, you could watch your shadow disappear beneath your feet. On Lodesea, you always had two shadows: one deep red, another the color of smokey amethyst. One told you the time of day, the other the time of year.

He got the notification on his mask. Tapping it again, the message came up, scrolling, but he switched it off again. Just the automated reminder to start work. He swung his legs off the ledge of the scaffolding just as Varbauthi was conquering the last of Angrabotha’s shadows, and the leaves were starting to reflect the golden light like dull mirrors.

It was time to tend to the gardens—another day in the long effort to turn Lodesea from a world of rock and sand to one with seas of trees.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeing Ritual

Photo Source: Album Cover for Dreadnaught – Caught the Vultures Sleeping

“Let my hands become your eyes. See through my fingers—not in the spaces between, but through them.”

I felt the cold touch of her skin over my brows and nose, but her palms were warm over my ears. I could feel the chalk nestled between her skin and mine.

“See,” she said. “See—“

I tried to see, but all I could do was feel; felt the chalk dust on my cheeks and lips. I entertained memories of just minutes ago when they painted my body with thick oil, dripping from brushes, colored by ash from the fire. It was rough against my skin. I felt uncomfortable, naked in front of so many people, embarrassed, and wishing that I hadn’t gone and asked for new sight.

“You’re entertaining thoughts,” said the old seer behind me. She adjusted her fingers on my face. I felt the prick of a long nail against my nostril. “Let go of them. Listen to the sound of your breath. Press into the space ahead—see.”

She pressed harder against my ears. But I wanted to leave suddenly, toss off her hands and cover myself with my favorite shawl draped at my feet. I could just reach down and throw it over my head. Was it always like this for someone new?

“Remember what you came here for,” she intoned.

I remembered my grandfather’s farm. I remembered the chickens below the hill. I remembered the forest fire, and how we had to move across the plains and cross the mountain. I missed those chickens. Now, my only friend was a crow who came to peck up the seeds that didn’t germinate in the rough soil.

“And what did he say?” Asked the seer.

He said that my grandfather knew I missed him, and that he did his best to move us before it was too late, even though I didn’t want to. I was too young then. Even as a young woman, I didn’t understand why until it was late. After the sun had set, causing the sky to glow through the smoke. I watched it set—rise and set, rise and set. I watched the crow come and go, pecking at the ground. I watched vines overtake the ground, and the wisteria blooms fade and grow back again. I wanted the angel’s trumpets that unfurled in pinwheels, and I watched the seer mash their thorny apples to paste.

Continue, she said.

Rains. Rains replaced glaciers. Ice-flows moved quicker and met the sea, melting away. I couldn’t stand it. Was this how the future would be? The old men wouldn’t find their fish and would have to go further and further south. The white bears would go further and further north. The new tools we made set in motion a new civilization, and we’d never be around to see it; our wisdom would be buried with us. New generations with powers to count and collect, but not one of them remembering the struggles that brought them there—our struggles.

I saw a woman off in the distance, combing her gray hair by a hearth. The seer? She walked into a mound hut. I followed, and inside it smelled like mildew, straw, and stew. Dried herbs hung from the ceiling; purple flowers shriveled but still fast with color, and a mortar and pestle in the far corner.

I asked: For what? Where will we moor this moldy seaship? The whole land is drifting in a wine-black gap, and there isn’t a destination except where we are, spinning: dust motes on dirtballs among games of gods.

I approached the seer at her hearth, pounding the seeds. Pungency. A taste of cinnamon and star anise between my teeth. Or was it a tang of iron—blood in the mouth?

I reached to touch her hair—to comb it with my fingers. Its waves were like the dull waters of the lakeshore at calm.

She stopped popping the shells of those apples as I touched her, and she pricked her finger on its horn. She brought the pierced pad to her lips, sucking the blood up. She turned to look behind her, to look at me—but it wasn’t her. It was me decades hence.

Good, said the seer behind me. I felt the chalky hands wrapped around my head release, trembling. Now you see through the fingers. Open up.

I opened my eyes, blinking, my vision blurry and doubled. The chalky smoke felt dry up my nose. When it cleared, I looked down at my hands.

The fingers were wrinkled: an old woman’s hands. The nails were long, black, and split.

I looked over my shoulder. There was no one. The seeress was gone and the witnesses too.

It was just me.

#writing#prompt#ritual#dark#seer#seeress#prophet#prophetess#shaman#shamanism#dream#gothic#ancient#hallucination#surreal#horror#climate fiction

0 notes