Quote

The thing is, it’s patriarchy that says men are stupid and monolithic and unchanging and incapable. It’s patriarchy that says men have animalistic instincts and just can’t stop themselves from harassing and assaulting. It’s patriarchy that says men can only be attracted by certain qualities, can only have particular kinds of responses, can only experience the world in narrow ways. Feminism holds that men are capable of more – are more than that. Feminism says that men are better than that, can change, are capable of learning, and have the capacity to be decent and wonderful people.

On claiming to be a stupid man who doesn’t know anything « Zero at the Bone (via cultureofresistance

)

7K notes

·

View notes

Quote

A right is always a privilege, if "right" means something that has to be dispensed by some program, and "privilege" means something scarce and supposedly good that's tied into a depriving system. A right is just a privilege that well-meaning shallow-sighted people try to give to everyone. But if we define a "right" as something that's implicit in the basic structure of society, so that everyone has it without anyone making any effort -- clean water because there are no poisons, freedom because there's no authority, equality because there are no means to concentrate wealth or power -- then that's really the opposite of the other kind of "right," and we wouldn't ever have a reason to declare it a right. For example, maybe no one has ever spoken of the right to see color. Some people are colorblind but they don't think of it as deprivation of a right. But suppose we all had a chip put in our heads, by the ColorSee Corporation, that blocked us from seeing color unless we paid ColorSee a monthly fee. Then we would talk about "rights," and liberals would not try to get the chips taken out, because that's just naive romanticism and we can't go back you know; instead they would demand a government subsidy so that everyone could pay ColorSee. And then the rich would hate the liberals and the poor, because damn it we had to spend years at painful schooling and jobs to afford to see color, and now the poor are going to get it for free which means we wasted our lives. And while we're all fighting about this, someone is inventing a wonderful new technology that, for a reasonable fee, allows us to breathe... If you think this is all a ridiculous nightmare fantasy, I think so too. Welcome to it.

Ran Prieur,

Against Rights

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The rest of the population ought to be deprived of any form of organization, because organization just causes trouble. They ought to be sitting alone in front of the TV and having drilled into their heads the message, which says, the only value in life is to have more commodities or live like that rich middle class family you’re watching and to have nice values like harmony and Americanism.

Noam Chomsky, Media Control: The Spectacular Achievements of Propaganda (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2nd ed, 2002), p. 27. (via 08-23-47)

53 notes

·

View notes

Quote

A revolution does not listen to the old language of law and order. It creates a new language….But a revolution is inarticulate at first. In war both warring parties have their sets of language. Two languages which exist clash. In a revolution the revolutionary language is not yet in existence. Revolutionaries are called young for this very reason. Their language must be grown in the process of the revolution. We might even call a revolution the birth of a new language…. In a revolution old speech is rejected by a new shout which struggles to become articulate. The revolutionaries make a terrific noise but nine tenths of their whoops will evaporate and the final language spoken by the bourgeoisie or the proletarians thirty years later will have cleared of these shouts of the beginning. But during the revolution suffering results from this very fact that the revolution is still inarticulate. The conflict lies between an over-articulate but dead old language and an inarticulate new life. War is a conflict between here and there, the languages of friend and foe, revolution between old and new, between the languages of yesterday and tomorrow, with the language group of tomorrow attacking…. The opposite of revolution is tyranny or counterrevolution. In a counterrevolution the old attack the young, and yesterday murders tomorrow; yesterday is attacking. Its technique is significant. While the young revolutionary group shouts because it is still inarticulate, any reactionary counterrevolution is so hyperarticulate as to become hypocritical. The disease of reaction is hypocrisy. Law and order are on everybody’s lips even where circumstances of a different truth prevail. Trusts and monopolies call themselves free enterprise. Unions cartelizing labor speak of freedom of contract. Decadent families speak of the family’s splendor and claims to privilege, and so on…. Lipservice is the cause of tyranny. An old order is degenerate, abusing future life wherever lipservice takes the place of shouting. The equilibrium between yesterday and tomorrow consists of an interplay between articulate namedness and inarticulate unknown-ness.

Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, The Origins of Speech, p. 12-3.

15 notes

·

View notes

Quote

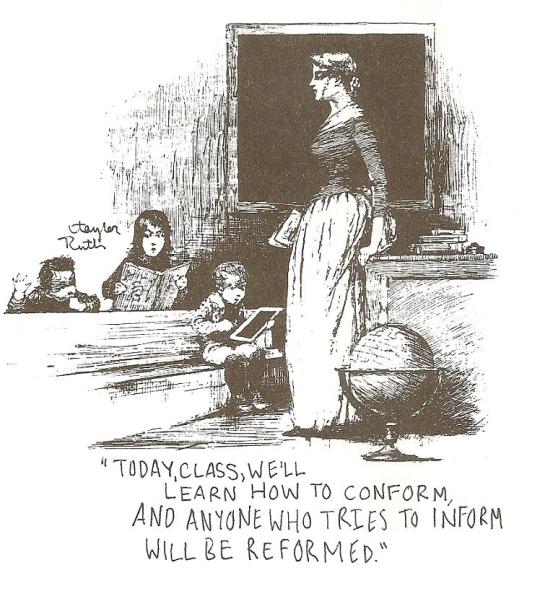

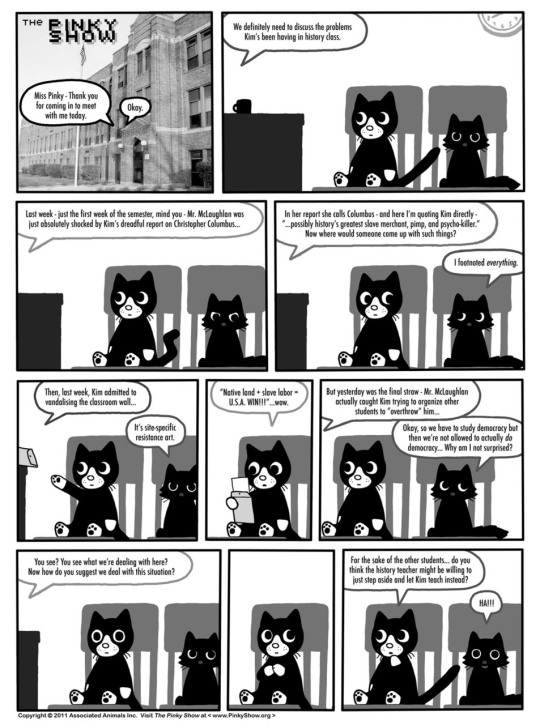

Parents, teachers, bosses and cops… they all achieve control by mimicking the binary system of threats (absolute law and punishment) that the state uses. Rather than an organic system of constant, decentralized give and take that rewards wider attention, the archist approach seeks to ideally shrink the subject’s attention down to a single, controllable input. This creates an artificial environment that rewards habits of rigidity and punishes persistent inquiry. And of course these habits are replicated in the communities and structures they create with their peers. Little has broken my heart more than going from teaching third graders who delightedly took to advanced algebra and calculus to jaded and broken middle schoolers whose priorities were social survival and escape from misery. Suffice to say, people would place far more value in science if they weren’t constantly beaten down for having an open mind.

William Gillis, "Every Scientist Should Be An Anarchist"

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

n fact, just take a look at the history of “trucking and bartering” itself; look at the history of modern capitalism, about which we know a lot. The first thing you’ll notice is, peasants had to be driven by force and violence into a wage-labor system they did not want; then major efforts were undertaken - conscious efforts - to create wants. In fact, if you look back, there’s a whole interesting literature of conscious discussion of the need to manifacture wants in the general population. It’s happened over the whole long stretch of capitalism of course, but one place where you can see it very nicely encapsulated is around the time when slavery was terminated. It’s very dramatic too at cases like these. For example, in 1831 there was a big slave revolt in Jamaica - which was one of the things that led the British to decide to give up slavery in their colonies: after some slave revolts, they basically said, “It’s not paying anymore.” So within a couple of years the British wanted to move from a slave economy to a so-called “free” economy, but they still wanted the basic structure to remain exactly the same - and if you take a look back at the parliamentary debates in England at the time, they were talking very consciously about all this. They were saying: look, we’ve got to keep it the way it is, the masters have to become the owners, the slave have to become the happy workers - somehow we’ve got to work it all out. Well, there was a little problem in Jamaica: since there was a lot of open land there, when the British let the slaves go free they just wanted to move out onto the land and be perfectly happy, they didn’t want to work for the British sugar plantations anymore. So what everyone was asking in Parliament in London was, “How can we force them to keep working for us, even when they’re no longer enslaved into it?” Alright, two things were decided upon: first, they would use state force to close off the open land and prevent people from going and surviving on their own. And secondly, they realized that since all these workers didn’t really want a lot of things - they just wanted to satisfy their basic needs, which they could easily do in that tropical climate - the British capitalists would have to start creating a whole set of wants for them, and make them start desiring things they didn’t then desire, so then the only way they’d be able to satisfy their new material desires would be by working for wages in the British sugar plantations. There was very conscious discussion of the need to create wants - and in fact, extensive efforts were then undertaken to do exactly what they do on T.V. today: to create wants, to make you want the latest pair of sneakers you don’t really need, so then people will be driven into a wage-labor society. And that pattern has been repeated over and over again through the whole entire history of capitalism. In fact, what the whole history of capitalism shows is that people have had to be driven into situations which are then claimed to be their nature. But if the history of capitalism shows anything, it shows it’s not their nature, that they’ve had to be forced into it, and that that effort has had to be maintained right until this day.

Understanding Power - Noam Chomsky (via noam-chomsky)

29 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Our analysis relies heavily on Ivan Illich’s concept of counter-productivity (also called “net social disutility,” the “second threshold,” or “second watershed”). These terms all refer to the adoption of a technology past the point of negative net returns. Each major sector of the economy “necessarily effects the opposite of that for which it was structured.” ... Beyond a certain point medicine generates disease, transportation spending generates congestion and stagnation, and “education turns into the major generator of a disabling division of labor” in which basic subsistence becomes impossible without paying tolls to the credentialing gatekeepers. The first threshold of a technology results in net social benefit. Beyond a certain point, which Illich calls the second threshold, increasing reliance on technology results in net social costs and increased dependency and disempowerment to those relying on it. The technology or tool, rather than being a service to the individual, reduces him to an accessory to a machine or bureaucracy. ... Illich mistakenly contrasted counterproductivity with the traditional economic concept of externality, treating them as “negative internalities” entailed within the act of consumption. But counter-productivity is very much an externality. The presence of disutility in consumption is nothing new: all actions, all consumption, normally involve both utilities and disutilities intrinsic to the act of consumption. When the consumer internalizes all the costs and benefits, he makes a rational decision to stop consuming at the point where the disutilities of the marginal unit of consumption exceed its utilities. In the case of counterproductivity, the net social disutility occurs precisely because the real consumer’s benefit is not leavened with any of the cost. Illich’s mistake lies in his confusion over who the actual consumer is. Counterproductivity is not a “negative internality,” but the negative externality of others’ subsidized consumption. The real “consumer” is the party who profits from the adoption of a technology beyond the second watershed—as opposed to the ostensible consumer, who may have no choice but to make physical use of the technology in his daily life. The real consumer is the party for whose sake the system exists; the ostensible consumer who is forced to adjust to the technology is simply a means to an end. In the case of all of the “modern institutions” Illich discusses, the actual consumer is the institutions themselves, not their conscript clienteles. In the case of the car culture, the primary consumer is the real estate industry and the big box stores, and the negative externality is suffered by the person whose feet, bicycle, etc., are rendered useless as a source of access to shopping and work. Rather than saying that “society” suffers a net cost or is enslaved to a new technology, it is more accurate to say that the non-privileged portion of society becomes enslaved to the privileged portion and pays increased costs for their benefit. ... The counterproductive adoption of technology results in what Illich calls a “radical monopoly”: "I speak about radical monopoly when one industrial production process exercises an exclusive control over the satisfaction of a pressing need, and excludes nonindustrial activities from competition . . . . Radical monopoly exists where a major tool rules out natural competence. Radical monopoly imposes compulsory consumption and thereby restricts personal autonomy. It constitutes a special kind of social control because it is enforced by means of the imposed consumption of a standard product that only large institutions can provide. Radical monopoly is first established by a rearrangement of society for the benefit of those who have access to the larger quanta; then it is enforced by compelling all to consume the minimum quantum in which the output is currently produced . . . . ... The effect of radical monopoly is that capital-, credential- and tech-intensive ways of doing things crowd out cheaper and more user-friendly, more libertarian and decentralist, technologies. The individual becomes increasingly dependent on credentialed professionals, and on unnecessarily complex and expensive gadgets, for all the needs of daily life. Closely related is Leopold Kohr’s concept of “density commodities,” consumption dictated by “the technological difficulties caused by the scale and density of modern life.” Subsidized fuel, freeways, and automobiles mean that “[a] city built around wheels becomes inappropriate for feet.” A subsidized and state-established educational bureaucracy leads to “the universal schoolhouse, hospital ward, or prison.” In car culture-dominated cities like Los Angeles and Houston, to say that the environment has become “inappropriate for feet” is a considerable understatement. The mere fact of traveling on foot stands out as a cause for alarm, and can invite police harrassment. ... Subsidies to highways and urban sprawl also erect barriers to cheap subsistence. Under the old pattern of mixed-use development, when people lived within easy walking or bicycle distance of businesses and streetcar systems served compact population centers, the minimum requirements for locomotion could be met by the working poor at little or no expense. As subsidies to transportation generate greater distances between the bedroom community and places of work and shopping, the car becomes an expensive necessity; feet and bicycle are rendered virtually useless, and the working poor are forced to earn the additional wages to own and maintain a car just to be able to work at all.

excerpts from Organization Theory: A Libertarian Perspective, by Kevin Carson (2008), p. 107-117

#kevincarson#cars#transportation#ivanillich#counterproductivity#radicalmonopoly#technology#economics#enantiodromia

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

For the sake of the earth itself, I evolved a philosophy close to Taoism from my experiences with natural systems. As it was stated in Permaculture Two, it is a philosophy of working with rather than against nature; of protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless action; of looking at systems and people in all their functions, rather than asking only one yield of them; and of allowing systems to demonstrate their own evolutions. A basic question that can be asked in two ways is: "What can I get from this land, or person?" or "What does this person, or land, have to give if I cooperate with them?" Of these two approaches, the former leads to war and waste, the latter to peace and plenty.

from Permaculture: A Designer's Manual by Bill Mollison

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Given what sometimes seems the terribly undercritical and overgeneralized techno-fetishization and techno-philia of some who read Amor Mundi regularly and occasionally comment here (and of course all are emphatically welcome here!), I can already imagine the protests that Shiva is really just a "Luddite" (by the way, the historical Luddites were right to fear for their lives and lifeways and that should possibly matter in our assessments of them) that she is engaged in a shrill "anti-technology" discourse, and so on. I want to stress in the most emphatic terms that it is my view that Shiva is offering up (or at any rate providing indispensable material from which can be formulated) a technoscientifically literate, technodevelopmentally democratizing advocacy of planetary permaculture-polyculture. Advocating for appropriate technology is not "anti-technology," directing our attention to politically pernicious deployments of technodevelopment exploiting the vulnerable and profiting elite-incumbents is not "anti-technology," delineating the catastrophic impacts of false models and marketing hype is not "anti-technology." As I keep on insisting, time and time again, "technology" doesn't exist at a level of generality that properly enables one to affirm a "pro-technology" or "anti-technology" stance in any kind of monolithic way. Technology is better conceived not as an idol to affirm or as an ethos with which to identify but as an interminable process of collective technodevelopmental social struggle in which a diversity of stakeholders (not all of them necessarily even human) are constantly contesting, collaborating, educating, agitating, organizing, appropriating, and coping with ongoing and proximately emerging technoscientific changes, costs, risks, and benefits.

from Dale Carrico, "Vandava Shiva on Resource Descent and Permaculture Politics"

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In his essay “Labor Struggle: A Free Market Model,” Kevin A. Carson argues that the Wagner Act was designed to centralize, bureaucratize, and tame the unions to the advantage of big business, which was already no stranger to privilege and subsidy. That is why some of the most vigorous advocates for modern unionism were leaders of industry, such as Gerard Swope, president of General Electric. By specifying who could negotiate terms and how strikes could occur, Wagner removed some of the most powerful tactics from the labor movement. Carson comments, “The primary purpose of Wagner, in making the conventional strike the normal method of settling labor disputes, was to create stability and predictability in the workplace in between strikes, and thereby secure management’s control of production” (emphasis in original). Certification created labor monopolies that eliminated the need for business to negotiate contracts with multiple groups or individuals within the same company. Business also benefited from the unions’ acting as enforcement agents, policing their own memberships’ compliance with contracts. They prevented wildcat strikes and punished boycotts, work slowdowns, and other labor tactics that had proven both popular and effective in the past. Leaders of modern unionism were aware of the benefits they offered to big business. In Ethics and American Unionism (1958), Sam Dolgoff wrote of John Lewis, president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) from 1920 to 1960, “In 1937, Lewis assured the employers that ‘a CIO contract is adequate to protect against sit-downs, lie-downs, or any other kind of strike’. . . . [T]he corporations accepted . . . ‘industrial unionism’ because as a matter of policy, the mass-production industries prefer to bargain with a strong international union able to dominate its locals and keep them from disrupting production” (emphasis added). Dolgoff outlined the impact of the Wagner Act on grassroots labor federations such as the UMWA. The National Federation of Mine Laborers had been the parent union of the UMWA, and by its constitution, “the Federation consisted of Lodges (Locals) and districts which vigilantly defended their independence from the domination of the National Office. Their insistence on autonomy and unity through federation (free agreement) was in keeping with the finest libertarian traditions of the American Labor Movement. . . . When Lewis became President in 1919 he did away with the federalist structure of the union, rooted out autonomy and self-determination of locals, centralized and took complete control of the union.” The Wagner Act completed the centralization. Thus both Carson and Dolgoff argue convincingly that the modern union was an arrangement of shared advantage between big labor, big business, and big government. The relationship between business and unions was not necessarily cordial but it was often convenient.

from Wendy McElroy, "The Modern Union versus Workers' Rights"

Always good to see decent union/labor commentary from a free market libertarian publication. That's it written by McElroy provides an element of surprise as well.

15 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Jensen: Is advertising ethically neutral? Lasn: If you ask ad executives, "How can you possibly work on a campaign for Ford suvs?" and you begin to explain to them about smog and the paving of the planet and global warming, they'll cut you off in midsentence with: "That's not our problem. We're artists, technicians, highly creative people. We provide a service to clients, and we don't take sides. Sure, we'll work for Ford, but we'll just as quickly do a job for Greenpeace, so stop bugging us about it." Advertising people are morally detached - and proud of it. That's why they can, with an untroubled conscience, promote even a killer product like tobacco. Jensen: That reminds me of what Robert Jay Lifton wrote about physicians at Auschwitz. Many of them, he said, acted as ethically as they could without questioning what he called "the Auschwitz mentality." Perhaps many of these ad people and designers can consider what they do ethical so long as they ignore the fact that the economic system they serve is grossly unethical. Lasn: Yes, they have to remain cool, detached professionals to hide the unethical nature of the business. But once you realize that consumer capitalism is by its nature unethical, then you realize that it's not unethical to jam it any way you can. Last year, in collaboration with six other graphic-design magazines, we launched a "First Things First" manifesto, which calls for a reversal of priorities in favor of more useful, lasting, and democratic forms of communication - a mind-shift away from product marketing and toward the exploration and production of a new kind of meaning. We asked designers to confront the unprecedented environmental, social, and cultural crises that flow out of the corporate and commercial work they do. It was a curveball to the heart of the profession, and it caused quite a stir. I think almost all the professions - engineering, journalism, medicine, law - need a wake-up call and a period of soul-searching about the role they play in the larger scheme of things.

from Truth in Advertising: Breaking the Spell of Consumerism: An Interview with Kalle Lasn by Derrick Jensen

7 notes

·

View notes

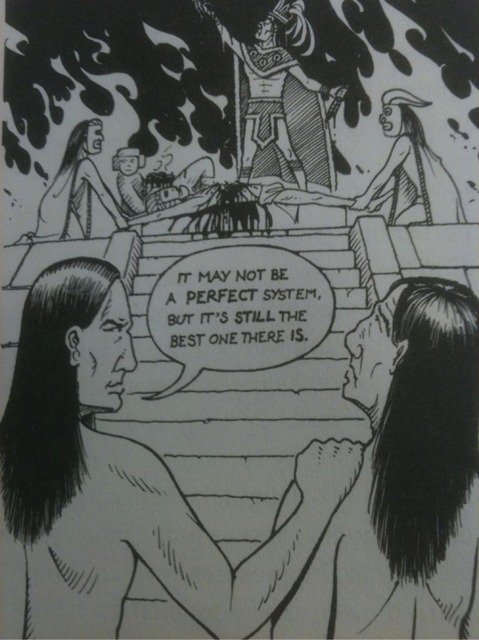

Quote

It is one of the big differences between the propaganda system of a totalitarian state and the way democratic societies go about things. Exaggerating slightly, in totalitarian countries the state decides the official line and everyone must then comply. Democratic societies operate differently. The line is never presented as such, merely implied. This involves brainwashing people who are still at liberty. Even the passionate debates in the main media stay within the bounds of commonly accepted, implicit rules, which sideline a large number of contrary views. The system of control in democratic societies is extremely effective. We do not notice the line any more than we notice the air we breathe. We sometimes even imagine we are seeing a lively debate. The system of control is much more powerful than in totalitarian systems.

Noam Chomsky - Democracy’s Invisible Line (via noam-chomsky)

50 notes

·

View notes

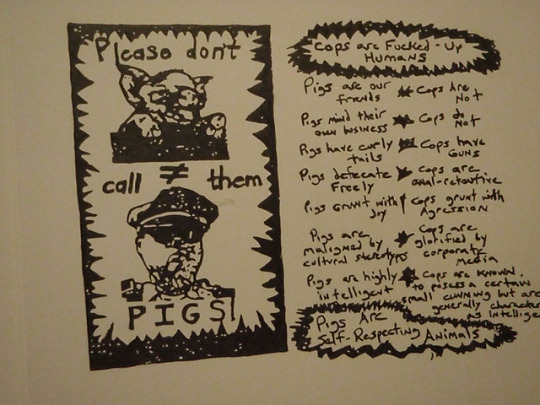

Photo

liberationfrequency:

Enough excuses.

441 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The discipline of economics achieves its formidable resolving power by transforming what might otherwise be considered qualitative matters into quantitative issues with a single metric and, as it were, a bottom line: profit and loss.

James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State, p.346

11 notes

·

View notes