Text

I don't know how well I can put my thoughts about this exchange into words, but I'm gonna try.

Kate has resolutely kept her walls up around Tyler for the majority of their interactions, but she just chose to be incredibly vulnerable with him. She let him see a fraction of how much pain she carries with her and it stops him in his tracks. (The camera literally stops panning around them the moment her dam bursts, and he stands completely still as she pours out her guilt over her past failure.)

Tyler respects Kate. He admires her capacity to read and to tackle this thing they both love. But now, for the first time, he's beginning to understand just how challenging storm chasing again actually is for her. How much fear and sorrow, how much trauma and torment it carries for her. He is stilled by the realization that this clever, fascinating woman is trapped under the weight of her past, and he gently encourages her to consider taking ownership of that pain by acting rather than surrendering.

But she's not ready. She side-steps his question entirely, stating that he should rest so he doesn't miss any storms the next day while wiping her tears away and trying for a bit of a smile.

And look at the way that shatters him.

He cuts himself off from replying and the grief in his face as he shakes his head and looks down shreds my heartstrings. Storm chasing is absolutely the last thing on his mind right now; he's concerned for her. He has taken every possible opportunity to seek her out in an effort to understand her since the moment their paths crossed. So maybe he's blindsided by the idea that she thinks his primary concern is not missing any storms. Normally, that might be true. He absolutely loves his job. The joy he finds out in the field chasing tornadoes radiates from his entire being every time he does it. And yet none of that passion comes close to how much he is centered on her and her pain in this moment.

But he can't tell her that. He's not ready to admit she is his primary concern and I think he recognizes in this moment that she's not ready to hear that yet either. She has effectively ended the conversation and dismissed him for the night. So he raises his eyebrows in a subtle agreement to go along with what she has said and he clamps his mouth shut. He returns her research notes to her and silently exits the barn to give her space.

And I cannot stop thinking about how much he just conveyed about the depth of his feelings for her with just a few micro expressions.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Scenes without Conflict: Incidents, Happenings, Sequels & More

Ideally, nearly every scene in a story will have conflict, because nearly every scene should have these primary plot elements: goal, antagonist, conflict, and consequences. And nearly every scene should have a turning point, which will be its climactic moment. With these things in their proper places, nearly every scene will follow basic structure:

In writing, all of these elements work in fractals. Yes, the overall narrative arc should have these things, but so should each act, and so should each scene.

. . . Generally speaking, anyway, because every rule is made to be broken.

As long as you know why and how you are breaking it.

With that in mind, sometimes you may have a scene that has no conflict.

Or no important goal, or antagonist, or consequences.

And on rare occasions, no turning point (though almost always there should at least be a turning point).

But these are exceptions, and the writer should implement them intentionally, not out of laziness or ignorance.

And when I say that most scenes should have conflict, I'm not saying they need shouting matches or flying fists. Conflict is simply what happens when a character runs into and deals with resistance (antagonistic forces).

In any case, let's go through some types of scenes that don't require much, if any, conflict.

Incidents

This term comes from Dwight V. Swain in his book, Techniques of the Selling Writer, but his writing on the subject there is surprisingly slim. Swain simply says:

An incident is a sort of abortive scene, in which your character attempts to reach a goal. But is met with no resistance, no conflict.

Incidents still have goals and consequences, but they lack antagonists and conflict. They almost always have turning points.

As K. M. Weiland points out, you could turn an incident into a full-blown scene. You could put in antagonists and conflict, but sometimes that's not what the story is about. Sometimes your character needs to simply succeed in a goal in order to progress to the next part of her journey (which is what the story is really about).

For example, say your character needs more information on a mythical monster (goal) so she knows where to look for it. Your character meets up with a professor who knows the myths. Now, you could turn this moment into a full-blown scene by having the professor be antagonistic--he doesn't want to give this information away. Or, perhaps, a third party is getting in the way of the professor giving your character this information. Now you have a scene with conflict, as your character tries to overcome that.

Or maybe you don't really need all that, because it distracts from the main story by adding length and weight to things that don't deserve them. It would emphasize pieces that aren't critical to the plot. So you write an incident. Your character meets up with the professor, gets the myths with the info, then heads off into the Murky Woods to find the monster.

Of course, there may be other ways to handle this situation. You could try to fit the information into another scene, or summarize the character getting the information instead. But if the myths themselves are important, then probably this conversation needs to be dramatized in a scene.

The turn happens when the character gets the final information and resolves what to do next with it.

Incidents can also be action-oriented. Let's say our story isn't really about catching this mythical monster. It's about what unfolds once this monster is caught. So an incident may be our character heading into the Murky Woods and successfully tracking and trapping the beast--no obstacles, no resistance, no conflict. The turn is just that, trapping the beast.

Again, I could turn this into a typical scene, by placing antagonistic forces in it. Maybe our character encounters a ruthless thunderstorm, trips and sprains an ankle, and almost gets eaten by the monster. Now it has conflict. It also now takes up more space and carries more weight. It also now shows how our protagonist is struggling, and maybe that's not what I want.

Incidents can be used to show off a character's prowess. If the character easily tracks and traps the monster without a hitch, then I'm showing she's skilled and/or experienced in that.

Sometimes there are scenes that seem to arguably fit between an incident and a typical scene, where there are technically antagonists, but they are non-threatening, and the character navigates them easily. Ruthless thunderstorm? No sweat. The monster wants to eat me? It'll be trapped before it takes another step. These can also be used to show off the character's skills.

And other times such moments are nice, because you can then undermine them later. They lull the audience into thinking everything is fine or great . . . until something bad and unexpected happens, bringing the character to her knees.

Almost always, an incident will still progress the plot. And there will almost always be some sort of shift, a change from how things were at the beginning of the scene to how things are at the end of the scene.

Happenings

As Swain writes, "A happening brings people together. But it's non-dramatic, because no goal or conflict is involved." Usually this is used to introduce characters who will be important later in the story, so in this sense, it's often also a meet cute.

With that said, though, not all meet cutes are happenings, and not all happenings are meet cutes.

I like to think of this as sort of the relationship version of the incident.

In a relationship plotline, the character either wants to draw closer to or push away from the other person (or maintain the relationship as is)--that's the goal. The antagonist is what gets in the way of that, which can be something outside the relationship, within the character, or even the other person in the relationship. The turn happens when the characters grow closer or more distant (or in some cases, successfully fends off the antagonist to maintain the relationship) in a defining way.

In a happening, the characters are interacting, but there isn't any antagonism or notable objective really.

As K. M. Weiland points out, a happening may also be used to relay information (that the character isn't actively seeking) or work as a distraction (which can be great to use when you want misdirection).

It should go without saying, that happenings should still be interesting and somehow contribute to the story. Frequently they are setting up what will happen in the story later, which brings me to my next section. . . .

Setup / Prequel Scenes

Some scenes are simply setups for payoffs later. Usually for most stories, we want to integrate setups into full-scale scenes, but I'd be lying if I said setup scenes didn't exist, or didn't exist in some successful manner. Like incidents and happenings, they are likely to be short. You often can't sustain a scene that doesn't have the primary plot elements for very long.

In some ways, the setup scene overlaps with happenings, because happenings are often about establishing a relationship that will be important later. But sometimes what is being established, isn't related to people.

Comedies, like Seinfeld or The Office often use setup scenes to deliver humorous payoffs later. In one episode of Seinfeld, Kramer stumbles upon the set of The Merv Griffin Show in a dumpster and begins curiously looking through the items. There isn't any real antagonist or conflict. There is hardly a meaningful goal (arguably). The true purpose of the scene is to set up the humorous payoff of Kramer's apartment looking like The Merv Griffin Show later, and then him behaving as a television host when people come over.

In his book The Structure of Story, Ross Hartmann refers to setup scenes as "prequels." And he notes that they can also be used to provide the context needed to understand or appreciate an upcoming scene. In this sense, the scene is foreshadowing and making promises about what is to come. He gives this example:

In Outbreak, a team of virologists is about to land in a "hot zone" full of infected patients. Dustin Hoffman's character warns Cuba Gooding Jr.'s character not to be afraid of what he's going to see. If anyone panics, it'll put the whole team in danger. Gooding's character is book-smart but has never seen a nasty disease in the flesh. He acknowledges the warning and promises that he's ready.

This sets up the upcoming scene where Gooding's character does panic. It also gives the audience context, so they can better appreciate the situation with the disease.

If you aren't careful though, such scenes can easily turn into info-dumps.

Almost always it's best to integrate exposition into a full scene, by following Robert McKee's adage: convert exposition into ammunition. That certainly leads to better writing. Still, it may not be realistic or possible to do that all the time. Sometimes you may want to insert exposition into a prequel scene.

Sequel Scenes

A sequel is a reactionary segment that follows a typical scene, but sometimes that reaction is important and long enough to make up its own scene. I already did a whole post on sequels, so you can learn about them in more detail here.

In short, they are made up of three phases: reaction (emotional response), dilemma (logical response), and decision (which leads to a new goal).

Because sequels are about how a character is responding to situation, they function a little differently. They often don't start with a scene goal, but are about the character finding a goal for the next scene. In some sequels, you can argue that the goal is figuring out a new goal, a new way of moving forward. If there is an antagonist and conflict, they will usually show up during the dilemma stage of a sequel. The character may be in conflict with himself, as he debates which path to take next. Or he may be in conflict with an ally where they argue the same thing. Or he may be seeking more knowledge to help him make up his mind, and find some resistance there.

Or maybe he doesn't, and there is no antagonist or conflict. That's okay too. In a sequel the character may simply be going through emotional and logical responses until he makes up his mind about what to do next.

Sequels are all about the reaction.

Thematic Scenes

Some scenes are only about exploring the theme. They may not progress the plot. They may not even relate directly to the character's arc. They may not have antagonists and conflict.

Of course, most thematic moments will also have all those things.

But some don't.

In A Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, Coriolanus must capture and cage birds to send back to the Capitol. So there is a goal, and I suppose you could say it's an incident, but it's really more about progressing the theme than about the plot. It actually doesn't contribute anything to the plot. It's about showing the birds, which are symbolic of humankind thriving on freedom, locked up. It's about discussing whether or not they are better off this way. Is it bad they can no longer fly free? Or is it good that they will now be kept safe?

In short, it's about exploring the thematic arguments.

Not every scene is about plot or character.

Victim Scenes

This is in some ways the dark version of the incident. In an incident, the character has a goal and meets no antagonistic resistance. As I mentioned, this is sometimes a good way to show off a character's skill.

But a sort of opposite can also exist, where an antagonist simply blocks the character, who can do nothing but wait for a moment of mercy. This puts the character into a passive state, a victim state, which almost never works. Passive characters lead to poor plots, and as counterintuitive as it sounds, their victimhood actually makes them less sympathetic.

But "almost never" isn't "never." Like anything, victim scenes can work well if you know how and when to use them, and like these other types, they often need to be short, because the audience won't be interested in them for very long.

Showing your protagonist helpless as he gets pummeled by an archnemesis can go a long way in showing off the antagonist's prowess. This can be particularly effective if we show how greatly skilled the protagonist is earlier. It'd be like Moriarty leaving Sherlock running with his "tail between his legs."

Victim scenes can also be useful in establishing the passive pain and unfairness your protagonist suffers in his day-to-day life. Sometimes we need to show the protagonist is helplessly trapped in a situation before something like the inciting incident comes along and offers him a way out.

Sure, you can argue that victim scenes still have conflict, but it's not really much of a "conflict" if the character can't do anything to fight back, if they are just waiting for a reprieve. So, I call them victim scenes.

In closing, not every scene literally needs conflict, it's just that, more often than not, in most stories, the scenes will be better if what's happening is framed with a goal, antagonist, conflict, and consequences. Too many new writers simply write conflict-less scenes because they don't know any better yet, or haven't learned the skills they need to. While we all start at the beginning, conflict-less scenes are there for when they enhance your story, not take away from it. They aren't there for you to overuse and abuse. They're there to make stories better.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surviving the Wilderness: Writing Realistic 'Lost in the Woods' Scenarios

The wilderness, with its vastness and unpredictability, can turn from serene to menacing in an instant. For writers, depicting a character who is lost in the woods offers a rich tapestry of emotions, challenges, and survival instincts to explore. But to do so effectively requires a blend of authenticity, attention to detail, and understanding the real-world repercussions of such an event.

Whether your character is an experienced outdoorsman or a city dweller thrown into the wild, this guide will help you craft a realistic narrative that resonates with readers.

1. Setting Up the Scenario

A. Choosing the Right Wilderness Environment

The first step in creating a believable lost-in-the-woods scenario is choosing the appropriate setting. Different types of wilderness present different challenges, and the environment you choose will shape the narrative.

Type of Forest: Consider the differences between dense forests, temperate rainforests, boreal woods, and tropical jungles. A dense forest might offer limited visibility and a disorienting array of trees, while a tropical jungle could present humidity, dangerous wildlife, and thick undergrowth. Each environment comes with unique hazards and characteristics that will impact your character’s journey.

Seasonal Considerations: The time of year plays a significant role in the story. In winter, your character might face snow, freezing temperatures, and the challenge of finding food. In summer, they might struggle with dehydration, heat exhaustion, or the difficulty of navigating through thick foliage. The season will also affect the availability of resources, like water and shelter.

Location-Specific Details: Consider the unique features of the chosen location. Is it known for dangerous wildlife, such as bears or wolves? Does the terrain include steep cliffs, rivers, or swamps? Researching the specific area can add layers of realism to your story, providing challenges that are true to the environment.

B. Character Background

The character’s background is crucial in determining how they will respond to being lost. Their level of experience, purpose for being in the woods, and psychological state all influence their actions.

Experience Level: Are they an experienced hiker with survival skills, or are they a city dweller with little knowledge of the outdoors? An experienced character might know how to build a shelter and find water, while an inexperienced one might make dangerous mistakes. Balancing their skills with the challenges they face can create tension and interest.

Purpose of the Trip: Why is your character in the woods? Whether they’re on a leisurely hike, conducting research, or fleeing from danger, their purpose will affect their preparedness and mindset. A hiker might have a map and supplies, while someone fleeing might have nothing but the clothes on their back.

Psychological State: Consider the character’s mental condition before they get lost. Are they overconfident, stressed, or fearful? Their psychological state will influence their decisions—overconfidence might lead to risky choices, while fear could cause them to panic. Understanding their mindset will help you write a more nuanced and realistic portrayal.

C. The Catalyst: How They Get Lost

The moment when a character realizes they are lost is a critical point in the narrative. How this happens can be gradual or sudden, depending on the story you want to tell.

Common Triggers: Characters can become lost for various reasons, such as deviating from a marked trail, encountering sudden weather changes, sustaining an injury, or simply having poor navigation skills. Each trigger offers different narrative possibilities—an injury might limit their mobility, while poor navigation could lead them deeper into danger.

Pacing: Decide how quickly your character realizes they are lost. It could be a slow realization as they fail to find familiar landmarks, or it could be immediate, such as after an unexpected event like a storm or injury. The pacing of this moment will set the tone for the rest of the story.

2. Writing the Experience of Being Lost

A. The Initial Panic

When a character first realizes they are lost, their initial reactions are often driven by panic. This moment is crucial for establishing the tone of the story and the character’s mental state.

Physical Reactions: Describe the character’s immediate physical responses, such as an elevated heart rate, adrenaline rush, sweating, and shortness of breath. These physiological reactions are the body’s natural response to fear and uncertainty.

Mental Reactions: Mentally, the character might experience denial, anxiety, or confusion. They might try to convince themselves that they aren’t really lost or that they’ll find their way back soon. This denial can lead to irrational decisions, like wandering in circles or making impulsive choices.

Immediate Actions: The character’s first actions after realizing they’re lost are critical. They might attempt to retrace their steps, call for help if they have a phone signal, or check the time to gauge how long they’ve been lost. These actions are often driven by the hope of quickly resolving the situation.

B. The Descent into Survival Mode

Once the character accepts that they are truly lost, the story shifts from panic to survival. This is where the character’s skills, or lack thereof, come into play.

Acceptance of the Situation: The character moves from panic to a more rational state of mind. They begin to assess their situation and prioritize their needs. This shift marks the beginning of their survival journey.

Basic Needs: The character will need to address their most immediate survival needs: shelter, water, food, and fire. Describe their efforts to find or create shelter, locate water sources, forage for food, and start a fire. Each of these tasks presents its own challenges and dangers.

Navigational Challenges: As the character tries to find their way, they will face navigational challenges. Dense foliage, fog, and the lack of clear landmarks can make it difficult to maintain a sense of direction. The character might struggle with the disorientation that comes from being surrounded by identical trees or losing sight of the sun.

C. Emotional and Psychological Effects

The emotional and psychological toll of being lost is significant and should be explored in depth.

Isolation and Fear: The character’s sense of isolation can amplify their fear. The fear of predators, injuries, or never being found can become overwhelming. This fear might cause the character to make rash decisions, or it could paralyze them, preventing them from taking action.

Hope vs. Despair: The character’s emotional journey will likely fluctuate between moments of hope and despair. They might find something that gives them hope, such as a sign of civilization or a source of water, only to be crushed when they realize it was a false lead.

Hallucinations and Delusions: In extreme situations, such as severe dehydration or starvation, the character might experience hallucinations or delusions. These can add an element of psychological horror to the narrative and further illustrate the severity of their situation.

D. Interaction with Nature

The character’s interaction with the natural environment is a key aspect of their survival story.

Wildlife Encounters: Depending on the location, the character might encounter dangerous wildlife, such as bears, wolves, or snakes. Describe these encounters realistically, focusing on the character’s fear and the steps they take to avoid or confront these animals.

Environmental Hazards: The natural environment presents its own set of dangers, such as quicksand, poisonous plants, and unstable terrain. The character might have to navigate these hazards while dealing with their growing exhaustion and fear.

Natural Resources: The character can use nature to their advantage by finding water, edible plants, or materials for building a shelter. This not only adds realism to the story but also gives the character moments of small victories that can keep them going.

3. Survival Tactics: What Works and What Doesn't

A. Basic Survival Skills

Understanding and depicting basic survival skills is crucial for writing a realistic lost-in-the-woods scenario.

Finding Water: Water is the most critical resource for survival. Describe how the character identifies potential water sources, such as streams or dew on leaves, and how they purify water to make it safe to drink. If they can’t find water, their condition will deteriorate rapidly, leading to severe dehydration.

Building Shelter: The character needs shelter to protect themselves from the elements. Whether they find a natural shelter, like a cave, or build one from branches and leaves, this task is essential for their survival. The process of building shelter also gives the character a sense of purpose and control over their situation.

Starting a Fire: Fire is essential for warmth, cooking, and protection from predators. Describe the challenges of starting a fire in the wild, especially if the wood is wet or the character lacks the proper tools. The ability to start and maintain a fire can be a turning point in the character’s survival story.

Foraging for Food: Finding food in the wild is difficult and dangerous. The character might forage for berries, roots, or small animals. Describe the risks of eating unknown plants or the difficulty of catching and preparing small game.

B. Navigational Techniques

Navigation is a critical aspect of survival, and the character’s ability to orient themselves can mean the difference between life and death.

Reading the Environment: The character might use the sun, stars, or natural landmarks to navigate. Describe how they attempt to determine their direction, and the challenges they face if the sky is cloudy or if they’re in a dense forest where the canopy blocks out the sun. Their ability to read the environment will depend on their prior knowledge and experience.

Using Makeshift Tools: If the character has access to materials like sticks, rocks, or even a piece of reflective metal, they might create makeshift tools like a compass or use shadows to determine direction. These improvisational skills can add a layer of resourcefulness to the character’s survival tactics.

Trail Marking: If the character decides to explore the area in hopes of finding a way out, they might mark their trail to avoid walking in circles. They could use stones, branches, or even carve symbols into trees. This tactic not only helps with navigation but also adds to the tension if they realize they’ve returned to a previously marked spot, indicating they’ve been moving in circles.

C. Mistakes and Misconceptions

Realistic survival stories often include mistakes that characters make, especially if they are inexperienced.

Following Streams Incorrectly: A common misconception is that following a stream will always lead to civilization. While it can lead to water sources, it might also take the character deeper into the wilderness. Highlight the risks of relying on this tactic without proper knowledge.

Overestimating Stamina: Characters might push themselves too hard, assuming they can keep going without rest. Overestimating their stamina can lead to exhaustion, injuries, or even fatal mistakes. Describing the physical toll of these decisions can add realism and tension to the narrative.

Eating Dangerous Plants: Foraging for food can be deadly if the character lacks knowledge of the local flora. Describe how they might mistake poisonous plants for edible ones, leading to illness or hallucinations. This mistake can be a significant plot point, demonstrating the dangers of the wilderness.

4. Realistic Repercussions of Being Lost

A. Physical Consequences

Being lost in the wilderness for an extended period can have severe physical repercussions.

Dehydration and Starvation: The longer the character is lost, the more their body will deteriorate. Dehydration can set in within a few days, leading to confusion, dizziness, and eventually death. Starvation takes longer but will cause weakness, muscle loss, and an inability to think clearly.

Injuries: Describe any injuries the character sustains, such as sprains, cuts, or broken bones. These injuries will hinder their ability to move and survive. If left untreated, even minor injuries can become infected, leading to serious complications.

Exposure: Depending on the environment, the character might suffer from exposure to the elements. Hypothermia can occur in cold conditions, while heatstroke is a risk in hot climates. Both conditions are life-threatening and require immediate attention.

B. Psychological Consequences

The psychological toll of being lost is often as severe as the physical consequences.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Even after being rescued, the character might suffer from PTSD, experiencing flashbacks, nightmares, and severe anxiety. Describe how their ordeal has changed them, affecting their ability to return to normal life.

Survivor’s Guilt: If the character was lost with others who didn’t survive, they might experience survivor’s guilt. This emotional burden can be overwhelming, leading to depression and difficulty coping with their survival.

Long-Term Anxiety: The fear of being lost again can cause long-term anxiety and phobias. The character might avoid certain environments or experience panic attacks in similar situations.

C. Legal Consequences

There are also legal and financial repercussions to consider, especially if the character’s actions led to their getting lost.

Search and Rescue Costs: In many places, the cost of search and rescue operations can be billed to the person who was lost, especially if they were negligent or broke the law. This can be a significant financial burden and add a layer of realism to your story.

Negligence and Liability: If the character’s actions endangered others, such as leaving a marked trail or ignoring warnings, they might face legal consequences for negligence. This could include fines, community service, or even jail time, depending on the severity of their actions.

Impact on Relationships: The ordeal of getting lost can strain relationships with family and friends. Describe how their loved ones react—do they blame the character, or are they just relieved they’re safe? The legal and financial consequences can also impact these relationships, leading to tension and conflict.

5. Writing Tips: Making It Believable

Crafting a realistic and compelling lost-in-the-woods narrative requires attention to detail and an understanding of the human experience in such extreme situations. Here are some tips to make your story believable:

A. Research and Authenticity

Understand the Terrain: Before writing, research the specific environment where your character will be lost. Whether it's a dense forest, a mountainous region, or a desert, understanding the flora, fauna, and climate will help you create an authentic setting. Pay attention to details like the types of trees, animals, weather patterns, and geographical features.

Learn Basic Survival Techniques: Familiarize yourself with basic survival skills, such as building a shelter, finding water, and starting a fire. Even if your character is inexperienced, knowing the correct methods will allow you to portray their struggles accurately.

Incorporate Local Myths and Folklore: If your story is set in a particular region, consider integrating local myths or folklore about the wilderness. This can add depth to the narrative and give the environment a more ominous or mystical feel.

B. Character Realism

Establish Their Skills Early: If your character has any survival skills, establish them early in the story. This could be through flashbacks, previous experiences, or hints in their background. This will make their actions in the woods more believable.

Show Their Vulnerability: Even the most prepared individuals can make mistakes. Show your character’s vulnerability by having them face setbacks, make poor decisions, or struggle with their emotions. This makes them more relatable and human.

Reflect Their Mental State: The character's psychological state should evolve throughout the story. Show how their thoughts shift from initial panic to determination, despair, and finally, either acceptance or a desperate push for survival. Use internal monologue, dreams, or hallucinations to illustrate their mental state.

C. Plot and Pacing

Balance Action with Reflection: While the physical actions of survival are crucial, so is the internal journey of the character. Balance scenes of intense activity, like building a shelter or escaping a predator, with quieter moments of reflection or memory.

Use Sensory Details: Engage the reader’s senses by describing the environment through sights, sounds, smells, and even touch. The rustling of leaves, the scent of pine, or the rough bark of a tree can immerse readers in the setting and heighten the tension.

Avoid Convenient Resolutions: Survival stories are often about struggle and perseverance. Avoid giving your character an easy way out, such as a sudden rescue or finding a cabin with supplies. Instead, focus on their gradual adaptation and the hard choices they have to make.

D. Dialogue and Interactions

Internal Dialogue: In situations where the character is alone, internal dialogue becomes crucial. Use it to explore their fears, hopes, and regrets. This can also be a way to explain their thought process and decision-making.

Flashbacks and Memories: If your character is alone, use flashbacks or memories to develop their backstory and explain their motivations. These can also serve as a contrast to their current situation, highlighting how far they’ve come or what they’ve lost.

Interactions with the Environment: Treat the wilderness as a character in itself. The environment should interact with the character, creating obstacles, providing resources, and affecting their mood and decisions.

Looking For More Writing Tips And Tricks?

Are you an author looking for writing tips and tricks to better your manuscript? Or do you want to learn about how to get a literary agent, get published and properly market your book? Consider checking out the rest of Quillology with Haya Sameer; a blog dedicated to writing and publishing tips for authors! While you’re at it, don’t forget to head over to my TikTok and Instagram profiles @hayatheauthor to learn more about my WIP and writing journey!

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, it's that time of the year again! ♥

At this point, I'd say that this has already become a tradition so here it is, the prompt list I'll use this year.

Like always, feel free to use it, mix the prompts, skip them, or do whatever you want with them: art, writing, edits, moodboards… it's your choice!

And, of course, tag me if you feel like it (here or on Twitter, @/LuaSpicyHours), or use #StarsAndSkiesKinktober if you want me to share your creations!

Transcript of the list under the cut ♥

Day 1: Dirty talk

Day 2: Against a wall

Day 3: Orgasm control

Day 4: Stockings

Day 5: Praise kink

Day 6: Thigh riding

Day 7: Risky places

Day 8: Threesome/Moresome

Day 9: Naked-Clothed

Day 10: Knife play

Day 11: Leather/Latex

Day 12: Role reversal

Day 13: Oral

Day 14: Sensory deprivation/Sensory play

Day 15: Cock rings/Cages

Day 16: Flashing

Day 17: Biting/Biting marks

Day 18: Body writing

Day 19: Pegging/Strap-ons

Day 20: Facesitting

Day 21: Masturbation

Day 22: Breeding kink

Day 23: Bondage/Restraints

Day 24: Dom/Sub dynamics

Day 25: Impact play/Spanking

Day 26: Voyeurism/Exhibitionism

Day 27: Choking/Breathplay

Day 28: Lap dance

Day 29: Masks/Costumes

Day 30: Hair pulling

Day 31: Aftercare

534 notes

·

View notes

Note

I feel like my writing is too choppy. Like I’m writing from one action to the next with nothing in between. I think it’s jumping around to much and isn’t really that smooth. It could just be a writer critiquing their own work too hard but I’m not sure. Any tips to avoid this or make it less choppy?

How to Write a Smooth, Rhythmic Narrative

A lot of people have trouble with their writing style, especially new writers who haven’t been practicing for long. The words come out choppy, the sentences jolt and stutter, and the words never seem to fit quite right.

Usually, this goes away with practice. It’s like how artists have a style that they settle into when they’ve experimented for long enough.

This post is to help anyone who may be having trouble with their writing style or perhaps don’t even have a writing style at all!

Keep reading

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Prompts for Fictober 2024

Fictober Event, The prompts for 2024

Here is the list for October this year. Write something short (or long) and tag it with #fictober24 in the first five tags. Let’s see your creativity!

"that was good work"

"it's been a long time"

"I know you better"

"no, we're not doing that"

"it's a new day, let's go"

"I'm not giving up"

"follow me if you want to live"

"are we happy?"

"don't listen to me, listen to them"

"is this normal?"

"well, that worked out great"

"did you hear that?"

"that's not the point"

"did you stick to the plan?"

"let's try this"

"no, I'm not okay"

"strangest thing I ever heard"

"you always have a plan"

"this is getting ridiculous"

"I saw your eyes light up"

"we've done worse"

"why are we doing this again?"

"we can fix this, I know we can"

"you didn't do anything wrong"

"it consumes me"

"you were the first"

"let me remind you"

"just say what you want"

"how did this happen?"

"I won't let you down"

"it's always been you"

This event is open to fanfiction and original fiction.

Start the first of October. You do not have to do the prompts in order. Tag your posts with #fictober24.

Please state at the top if your entry is original fiction or fanfiction and what fandom. State common warnings and triggers at the top and tag accordingly. No AI generated text or art.

I reserve the right to not reblog fics that I find inappropriate. I will reblog things here on @fictober-event, follow this blog to see all the entries.

Go forth and write!

559 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing extreme emotions

Just some things to think about

How they cry

—This is extreme emotions, not a dainty tear down their face. Are they crying silent tears of rage as they pour down their face, eyes wide and unblinking? Or are they choking on every word as their voice cracks? Describe it in detail.

How they try to calm down

—They don’t have to STAY calm, but see if you could get them to THINK they’ve got their emotions under control. Are they with/thinking about a loved one? Or are they just trying to push the event out of their head as they try to regain their breath? Now, should someone walk in who SHOULDN’T, then by all means, have them just go back to whatever they were doing before, or even worse.

Body language

—How do they behave? Are they jumping around and cheering, or do they quietly shake their fist in rage as they stare through the other people? Depending on the character, one can mean a lot more than another. For example, a quiet, shy character getting worked up means a lot more to the audience because we get to see a new side to them

Breathing

—Obviously everyone breathes. But irregular breathing patterns (especially when they’re noticed by someone who’s not the MC) can tell a lot about what their reaction is. Are they losing their breath from laughing to the point where they begin to laugh and cry? Or is the world spinning around them as they begin to hyperventilate, going lightheaded and feeling overwhelmed

How they interact with the setting

—Are they throwing things, staring straight through all of the beautiful scenery, or are the bright colors blinding them? The more public and busy the location is, the less they may feel inclined to really act out, or maybe part of it is that they’re so emotional that they don’t care. Just try to keep the setting in mind for any dramatic, emotional scenes.

Other people’s reactions

—Consider how much the outburst is out-of-character when thinking about reactions. Do people run to console the anti-hero when they break down into tears, or do they stand there awkwardly not knowing what to do? Or, does this happen so often that others know exactly what to say and do, or are they so tired that they stand in the corner, defeated?

Remember to stay in character

—If you want this scene to stand out, you need to remember the characters themselves. Everybody gets emotional and breaks down, and when you can make it true to the character, you will make it real to the audience

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

every once in a while, someone asks me, "where's the best place to buy your books?" -- specifically, they want to know which platform takes the lowest cut, so the largest percentage of the cover price goes to me.

this is a very cool, kind thing to ask, and i appreciate it every time. but if you really want to make sure an indie author you like makes money, here's the two biggest things you can do for their book:

rate/review. leave a star rating on whichever storefront you bought the book from. write a quick review on goodreads or the storygraph.

signal boost. post about the book on social media. recommend it to friends who like the same stuff.

these two things, either alone or together, put the book in front of more eyeballs. that translates to more sales, which translates to more eyeballs, which translates to more sales.

this is a big help even on platforms that pay smaller royalties--35% of 10 sales is still more money than 95% of 1 sale.

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

A Guide to Productive Filler

I was going to write this post about the wonders of fanfic and how it does not do the “forced miscommunication for cheap drama” trope, and it did not stay that post for long.

I’m sure it’s out there, but it’s not saturated in the most popular fics and I think I know why: Fanfic exists in contrast to the established canon, and the canon has forced miscommunication, thus fanfic looks at the perpetual failure of those plotlines and ignores it.

Nobody likes this trope, yet it keeps happening. In TV, at least in the old days when we had full seasons with appropriate and satisfying filler episodes and actual good stories and such (you know, before Disney +) TV shows were contracted to fill a minimum number of episodes and didn’t always have enough content to fill it, especially CW shows.

Enter filler episodes, which, when productive, still entertained the audience with off-beat side quests or gave more screen time to beloved side characters or explored more of the world and the lore. Filler plots meant that you could casually check in on your favorite show once a week, or miss an episode, and not feel completely lost because the plot wasn’t super tight and lean. Some of my favorite episodes of all my favorite TV shows are filler plots and just because they’re “filler,” as in, not a plot-heavy element to advance the narrative, doesn’t mean they were lacking in story.

That was good writing.

Bad filler elements were sh*t like forced miscommunication for cheap drama and it still exists even in the “mini series” that are really just long movies extended to keep people from canceling their subscriptions. TV shows may have one or two head writers, but they’re still written by committee and producers and production companies trying to milk as much from a profitable product as possible, which means they couldn’t write an efficient, epic romance that ended too quickly. They had to faff about for a few seasons before delivering to keep butts on couches tuning in to generate sweet, sweet ad revenue.

Forced miscommunication in TV shows have always made sense in that light. Yeah it’s a product of bad writing, but I can’t point at the head writer or even the staff writer alone and criticize their writing ability because it likely wasn’t their decision.

Forced miscommunication in books, however—that I have no excuse for. Books aren’t written by committee. In this case, I really can just blame the author for their bad choices, which, in turn, maybe came from their favorite TV shows and how they executed similar plot lines.

Fanfic does not do this, usually. It’s not written by committee and has no quota to fulfill to beef up the narrative with extra chapters.

—

So. You want your story to be longer, fanfic or otherwise, but you’re struggling because your plot is too thin and you don’t know where to go from here.

First, a disclaimer: Novellas exist and can be as short as they need to be.

“If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter,” means that just because it’s long doesn’t mean every word serves a purpose. With enough time, the writer can trim down their thoughts for conciseness and clarity, and say the same thing with better impact with less beating around the bush.

So just because it’s short doesn’t make it bad, just because it’s long doesn’t make it good. It’s about what you do with the words you’ve written.

However, if it really is a thin story lacking substance and oomph, here’s some suggestions that are not sh*t like “forced miscommunication”. These are not meant for generalized application and should be considered heavily before implementing, because any one of them can change your book for the worse by adding in unnecessary detail that distracts from the main story.

1. Consider multiple narrators

Now. I just read a rather bad book that could have lost about ⅔ of its story for a variety of reasons and told the same story in a fraction of the page count. One of those issues was giving the villain several POVs that ruined the suspense and the tension because the reader became privy to their grand plan long before the protagonist and instead of having all our questions dying to be answered with the protagonist, we were waiting around for them to stop fooling around and figure it out already.

With that said, if you have a character of second importance to the protagonist whose perspective would benefit and enrich the story, consider giving them POVs to explore either when the protagonist couldn’t be present, or in contrast to the main narrator’s thoughts on the story and conflict.

I’ve never written anything without multiple POVs and still get carried away sometimes just trying to fill in all the missing time that didn’t add enough to the story to make it worth it. I have deleted POVs from ENNS that were better left up to audience interpretation then all laid out on the table.

This technique very much necessitates restraint, but giving your foil character, your deuteragonist, even your villain some narration “screen time” might help you beef up your word count and tell more than just one biased side of the same story. Fanfic tends to be very efficient with this because, again, one writer working for free tends to want to be efficient and not give pages upon pages of useless prose.

2. Side-quests and character studies

My all time favorite filler episode of any TV show is LOST’s “The Constant”. It focuses entirely on the side character Desmond. He’s an unwilling time-traveler and throughout season 4, struggles to control his temporal displacement and risks dying if he can’t find a “constant” to anchor him to the correct timeline.

This episode is often praised as one of, if not the show’s finest hour. Desmond spends most of the runtime flipping erratically between the past and the present as his romantic relationship spirals for other plot reasons. He ends up making his “constant” his fraught relationship and is able to revert to the past with knowledge of the future to get his then-ex girlfriend’s new phone number so he can call her at an exact date in the future to prove he won’t have given up on them. When Des finally makes that call 8 years later, it’s so emotional, so full of catharsis, so exciting to see him finally reach her after struggling since we met him.

And it has absolutely nothing to do with the plot at large, only Desmond’s arc. It explores some of the world’s lore but doesn’t answer any of the main plot questions or progress any other major character, and Des is the only time traveler so all the risk surrounding time travel is only for him. Critically, it still adheres to the themes of the show and fulfills much of the promises of this character’s role in it.

The show’s worst episode, “Stranger in a Strange Land,” is also filler about protagonist Jack’s tattoos. He makes a relationship with a woman nobody cares about and spends the entirety of the episode’s flashbacks, which is most of the episode’s runtime, dicking around in Thailand. With this quasi-wise woman’s tattoo techniques. Nobody cares what they mean, they didn’t connect with the themes of the show, didn’t tell us anything substantial about Jack or the world, lore, or story, and just felt like a massive waste of time.

If you’re going to write side quests, be more like “The Constant” and less like “Stranger in a Strange Land”.

3. “Slice of Life” moments

A repeat of referencing this scene and this movie but I don’t care: “Doc Racing” from Cars is just one example. Adding in scenes like these won’t give you tens of thousands of words, but maybe you only need a couple hundred to feel satisfied.

Slice of life moments slow the pacing down, so place them wisely, and just let your characters be people in their world. Small things, human things. In Cars, it’s an old man letting himself enjoy life again when he thinks nobody’s watching. I have a scene in my sci-fi WIP series where two brothers, plagued by their family’s social status, take a drive and pick up greasy drive-thru food to park on a mountain overlook and just watch the city while licking salt off their fingers. I think Across the Spiderverse is about 20 minutes too long, but that scene of Miles and Gwen upside down on the roof before the plot ramps up is another quiet, human moment.

It could be a character who needs a break from the breakneck speed of the plot and the stress to listen to music, walk away from the project and enjoy the sun, anything. Do try to not get overly pretentious trying to make it super metaphorical and poetic, let the audience do it for you. These quiet scenes could end up being the audience’s favorite.

—

If you’re trying to make your book longer, don’t be like Bilbo Baggins, okay? Don’t let your characters be spread thin, like butter scraped over too much bread. Add, don’t stretch. If the romance is on track to come together sooner, let it, or figure out a more meaningful way to delay it than throwing in a dumb argument that won’t mean anything in 20 pages anyway.

This wasn’t an exhaustive list, just what I think could be the most effective with the widest applications across genres.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Goals In 3 Steps

Remember kids: For every major character, especially your protagonist, you need to know the following:

What do they want?

What’s in their way?

What are they willing to do to get it?

Recently beta’d a story where the protagonist’s only goals were what was right in front of their face at any given moment, no dreams or aspirations beyond what could be achieved in an evening, and whose wants would flip-flop and contradict each other, leaving them very confusing and frustrating to follow.

Your protagonist needs to have these goals established as quickly as possible, and ideally, every major scene and decision they make should reflect back on that goal, either working toward it or sacrificing gains and having to work backward. This establishes conflict, and, high stakes or low, every story has conflict.

Your side characters, especially the mysterious type, don’t need their hopes and dreams told to the audience with any haste, but you, the author, should still know them so that these characters don’t unintentionally contradict their own desires.

Examples:

A wants to buy this really cool bicycle

But it’s really expensive and they don’t have enough money

So they work odd jobs and sell trinkets in garage sales and make a lemonade stand, counting up their coins with each sale

.

B is secretly in love with C

But C is the barista at a coffee shop and possibly only nice as part of their job

So B must find a way to determine if C likes them back, without looking like a fool if they’re wrong, attempting to charm their way into a date

.

D just wants to live a normal happy life

But they’re dragged into a whirlwind adventure and are the long-lost heir

They sure don’t want this responsibility and fight hard against it, but eventually realize that their boring, normal life isn’t as satisfying as they thought, and then have to fight for their place in the plot

.

E is unhappy in their marriage and wants out

But societal expectations demand they stay put

So ensues E’s journey of self-discovery, and the pressures both internal and external to either leave or see through their commitment

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

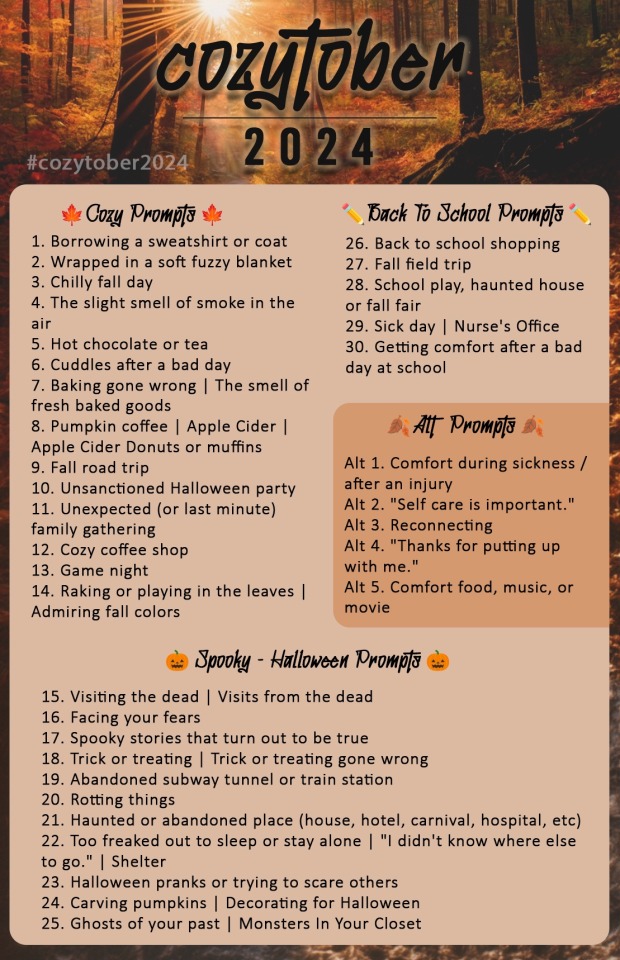

Hey writer friends! There's a fun, all-fandom, writing/art event taking place for fall. Cozytober! This is their second year and since they don't have a tumblr page, I thought I'd share the prompts!

For anyone participating in any of the other big fall events (@sicktember @whumptober @flufftober ) these prompts actually meld really well with those.

For more information about Cozytober rules, as well as a text version of the prompts, check out their AO3 Collection page [Here]

Happy writing!!

612 notes

·

View notes

Text

PLEASE for the love of the universe read anti-colonial science fiction and fantasy written from marginalized perspectives. Y’all (you know who you are) are killing me. To see people praise books about empire written exclusively by white women and then turn around and say you don’t know who Octavia Butler is or that you haven’t read any NK Jemisin or that Babel was too heavy-handed just kills me! I’m not saying you HAVE to enjoy specific books but there is such an obvious pattern here

Some of y’all love marginalized stories but you don’t give a fuck about marginalized creators and characters, and it shows. Like damn

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

That Rolling Stone article about Chappell Roan... the bits about the shit she went through are already wild, but what really gets me is when the article starts listing. every. single. singer. who reached out to her, worried, to commiserate, to give tips, to agree that the harassment of fame is indeed hell. I'm like. "So y'all agree?? All of y'all agree being famous is horrible???" Good LORD.

Fellow stars have reached out to see if she’s OK. Charli XCX was one of the first to do so (..). Eilish has been keeping tabs on Roan (...). Hayley Williams DM’d her, offering to chat with Roan anytime. Katy Perry told her to never read the comments. Lorde gave her a helpful list of things to do at an airport to fly under the radar. The band Muna hosted her for dinner. Miley Cyrus invited her to a party. Lady Gaga has passed along her phone number (...). Roan went on walks and grabbed coffees with Lucy Dacus and Julien Baker. Their boygenius bandmate Phoebe Bridgers came over to Roan’s just to hang, commiserating on how fandom behavior has become increasingly “abusive and violent.”

Sabrina Carpenter, who’s also had a shockingly massive year, suggested they meet up and unpack their summers. “We’re both going through something so fucking hard … she just feels like everything is flying, and she’s just barely hanging on,” Roan says. “It was just good to know someone else feels that way.” Backstage at the Vic Theatre in Chicago, Roan flashes her phone to show a lengthy email from Mitski she received that morning. “I just wanted to humbly welcome you to the shittiest exclusive club in the world, the club where strangers think you belong to them and they find and harass your family members,” it reads.

I?? MEAN???

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

if you're trying to get into the head of your story's antagonist, try writing an "Am I the Asshole" reddit post from their perspective, explaining their problems and their plans for solving them. Let the voice and logic come through.

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you to the writers that write even though they don’t get a lot of notes. It’s very easy to continue to write when you can see tangible success. It’s very very hard to continue to write when you feel like you’re alone in your own echo chamber. I admire you and I love your work and I hope that you never stop writing, because fandom needs you.

4K notes

·

View notes