Text

Do I actually want to write this fanfic or do I just want to wallow in the delicious daydream like a pig in the mud?

46K notes

·

View notes

Text

10 things I’ve learned about writing over the last year

In the last year, I’ve published very little indeed. I’ve been writing a bit and plotting a lot, but I’ve done a lot of thinking about and analysing the craft of writing, and I thought it might be fun to reflect on the most important lessons I feel l’ve personally learned over the last 12 months. Take ‘em or leave ‘em. They are not necessarily for everyone. Nor are they intended to be a criticism of anyone, including my past self. Some of the mistakes identified below I’ve made, some I haven’t, but these are all now things that are at the forefront of my mind when I write. You don’t have to agree.

1. Characters are not puppets for the plot

The first one is a big one. It has taken me a long time to work out why certain characters end up feeling flat when I read them, or why sometimes their behaviour feels “off” to me at one point or another. The reason is this. If you are making your characters do things just because it suits the plot or what you personally want to happen, you are at risk of having them behave out of character - and then the readers stop identifying with the character. You may achieve your plot point, it may be funny or “cool” or press your own personal buttons to have them act in a certain way, but it is crucial that you step back and think about whether this is actually something the character would do, and why they’re doing it…otherwise the characters are just puppets for your plot. This applies not only to your protagonist, but every single person in the scene. Every person has their own motivations, and you should know why they’re doing something.

2. Twists should be surprising, yet inevitable

I am indebted to Writing Excuses for this one - and as they say on their podcast, if a twist can only be surprising OR inevitable…it should be inevitable. It is more important that you foreshadow something than you surprise the reader. Readers would always rather feel like they’re cleverer than you than you cheated them. And that’s all you’re doing if you spring a surprise on them that you didn’t foreshadow. You cheated.

3. Engage the senses

This is a simple one. When describing, engage as many of the senses as you can. If you only rely on what your character can see, your descriptions will probably fall flat.

4. Use filtering with caution

By “filtering” I mean points that you preface with phrases like “He thought”, “She saw”, “He could hear”, “They knew that”, etc. You are filtering the point you really want to make through these “filter” words. I have read advice from extremely successful authors that says you should always cut these words. It is undoubtedly true that the more of these you cut, the closer to your character’s point of view and voice the reader will feel. But it is not true that you can never use them. There are some authors that use it habitually and their characters still feel like they breathe off the page. Sometimes you might even want to create a sense of distance between the character and the reader. But know what you’re doing when you use it. Proceed with caution.

5. Tie up your threads in the right order

This is another Writing Excuses one - from Mary Robinette Kowal. It originates from the “MICE” quotient, the theory of which is that every plot and subplot can be fitted into 4 categories - milieu, idea, character, event. Without going too much into detail (but it’s worth looking up!), the basic point is: wrap up your plot points in the order you introduced them. If you’ve ever read a story that feels like it keeps ending, and ending, and ending…the points have probably been introduced and then wrapped up out of order. There should be a first-in-last-out policy when it comes to plot points.

6. Decide on your end at the beginning

This is likely a controversial one for pantsers. Look, I’m not saying that one has to plot. But if you want to write a story that feels focused and tight, everything you write should be aimed at getting you from A to B. It’s easy to come up with cool ideas and things that could happen, but you should only include those that are going to progress your characters and plot to where they are going to be at the end, or that are going to serve the underlying point(s) that you are trying to achieve. At the very least, know what point you are trying to make in the story - e.g. the fall of a hero, about learning to trust, about finding love. And be aware that you should be setting up that point from the very beginning of the story. If the story is about two people finding one another, you probably should have set up at the beginning that they lost one another. Which leads me to the next point…

7. Be conscious of the promises you are making to your readers

Admittedly this wasn’t a new lesson to me, but its importance has grown and solidified in my process over the last 12 months. From the very beginning of a story, the opening scene, you are making implied promises to your readers about what the story is about. If your opening gambit is a character being bullied by their mother and not being able to stand up for themselves, you are probably promising the reader that this pattern of behaviour is somehow going to be rectified or addressed in the course of the story. And that means you have to be fair to your readers; don’t mislead them. This applies to everything in your story. Think Chekhov’s gun: if you put a loaded gun on the mantelpiece in Act 1, you better have it fire in Act 3. Now, OK, sometimes your loaded gun will be a red herring. But you MUST NOT cheat your readers. That loaded gun represents a promise, so it might not shoot someone but you can’t just leave it hanging there without ever referring to it again.

8. Be specific

The specific is always better than the general. “He looked round” is OK but isn’t “His head snapped round” so much better? “She ran his fingers through his hair” gets the message across, but “Her fingernails grazed his skull” is something I can really feel. Be as specific as you possibly can. (Note: this does not mean that I need a full blow-by-blow account of the specific type of crane the protagonist is operating and paragraphs of explanation of how it works. Yes, Anthony Horowitz, I’m looking at you.)

9. Tailor your descriptions to the character

This can be a tricky one when your characters are all operating within the same sphere (e.g. they are all police officers), but an easy way to tailor your character voice is to adjust your descriptions to the character’s experience. A teacher might not think of a carpet as blood red; an assassin might. The first thing a teacher sees when he walks into a room isn’t the easiest point of exit; it might be for an assassin. An assassin might not instinctively bother to remember someone’s name; for a teacher, it’s practically in the job description.

10. Asking “why” will fix most of your problems

This is a more general one that loosely ties a lot of this together. But if you’re having problems - whether it’s that the story feels like it’s dragging, or your characters don’t seem to want to do what you wanted them to do - just stop and ask “why”. Why am I including this point, why does it matter, why are the characters wanting to do something else. If you don’t have a clear answer (beyond “I thought it would be cool”), you’ve probably got your answer - which is to throw the point out and try something else. But, otherwise, asking “why” will help you to focus on what you’re trying to achieve - and that’s always going to help you get back on track.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I often wonder what happened to authors of unfinished fanfictions.

170K notes

·

View notes

Text

First lines

I was tagged by @afewbulbsshortofatanningbed. Thank you - this was really interesting! I loved seeing yours.

Rules: list the first line of the last ten (10) stories you published. (Or however many stories you have, if you don’t have 10. I’m including collabs!) Look to see any patterns you notice yourself, and see if anyone else notices any. Then tag some friends.

HAHAHA I do not have 10 to offer. But have 5.

убийца (Reprise)

Yassen is on the other side of the world when it happens - in Tokyo, about to fly to Amsterdam to meet with his latest client: a British pop star whose phone calls are already annoying him. He has been delayed in Japan for two days, tying up some loose ends.

Dividing Lines

When Alex turns up on Kabir’s doorstep a fortnight after their school reunion, Kabir’s not really sure what to make of it and he’s none the wiser when Alex leaves three or four hours later.

Among the Lotus

Alex Rider’s first impressions of Yassen Gregorovich aren’t promising.

Reunion

Sunday mornings were always quiet in the shop.

Retribution

Yassen had known that it was a mistake to send Alex to Russia.

It’s a bit tricky to discern a pattern, I think?! Retribution starts by telling you Yassen made a mistake, and you spend quite a while waiting for what the consequences of the mistake are - i.e. it presents the question of “why was it a mistake?” Likewise, in Dividing Lines (which I wrote with @valaks), it’s deliberately setting up a question of “what should we/Kabir make of Alex turning up on the doorstep?” In other words, they’re both posing a question to answer in the first line. In убийца (Reprise), on the other hand, it’s made clear almost instantly what “it” is that’s happened; it’s creating the setting and backdrop for the story - the mystery isn’t immediately obvious from the first line. That’s also true of Reunion. Among the Lotus is a special case for reasons I can’t explain without spoiling.

One thing that does tie them together (with the exception of Reunion) is that it’s immediately clear who the narrator is. Not a good or bad thing particularly, but I clearly have a preference for making my POV character clear ASAP....

Think most of these have been tagged already but would love to see any or all responses from @valaks @morfoxx @yucasava @ahuuda @pongnosis @irelise @corolune (but no pressure any of you!).

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Lupin, I'm curious about what motivates and/or inspires you to write! Your fics are so fun to read and I adore the plots + themes that you explore. Also — is there a particular part of the writing process that you enjoy and why?

I am woefully behind on answering asks, I'm so sorry. But thank you so much for getting in touch!

Generally, I'm motivated to write because there is something I want to produce; a story I want to tell. When I was younger I had this feeling of "I want to write, but I don't know what!"; now, I tend to pick up my pen very specifically because I have a story in my head that I want to get down on the page. I don't always know when it's coming or where it's coming from - it might be because I've been chewing an idea over with someone in DMs and it suddenly crystallises; it might be because (say) I've been reading/watching a lot of a specific genre and it puts me in the mood to write something in that genre; it might be because (as happened not very long ago) I go somewhere and it gives me a specific idea. So...inspiration comes from lots of different places. But generally there has to be a point to the story. I like exploring characters' motivations, their relationships, their perceptions of one another, and I guess that's often what inspires me to go from vague idea to wanting to write a story.

My favourite part of the writing process - as many people know - is editing. I hate getting the words down on the page in the first place. I hate it so much. I like it when the story is already written down and I get to polish that ugly little lump of coal into something more interesting.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

@valaks Sounds like it’s time to finish that Coffee Shop AU

If you could read any Alex Rider fanfiction.

Any like au or idea

What would it be about?

#alex rider#alex rider fanfiction#what do you mean I have a vested interest#more valak and galimau fic ALWAYS#gimme

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sounds like sound advice to me.

New Habits That Are Making My Fic Writing Much Better

So I spent a little over a year in such a long and terrible writer’s block that I thought I would never be able to write again. And then I started writing again! Here’s how I’m working on making it fun and sustainable

Remind myself that fics don’t have to be good to be good. I’ve enjoyed many a fic that objectively wasn’t great so I don’t have to make it perfect for someone else to get enjoyment out of it.

Only write the fun bits. “Oh wow I really wanna write this scene but I need something to pad it out before I can get there” Do I really? More often than not, the answer has been no. I no longer write anything that I would skip over when reading to get to the good stuff. “But what if your pacing suffers?” First, I don’t care. Second, it tends to improve actually.

Write what I wanna write, no matter how weird it is. There is much more of an audience than I expected for fics that are half conlang infodumping and half body horror

Drop whatever doesn’t spark joy. Writing is a treat for me and I’m sharing it with y’all because I’m nice like that. If it’s not a treat for me, I’m not gonna write it (unless it’s something I really want to put a lot of effort and difficulty into doing well). I am not giving myself any obligation to WIPs. I have gotten too much enjoyment out of dead fics to pretend that finished works are the only ones with merit

Make peace with the time I don’t spend writing. Sometimes (most of the time) a fic idea needs to spend a few days in the Idea Percolator before I can put it on the page. Letting ideas percolate and even just resting from writing are both Part Of The Process and not something to beat myself up over

Fanfiction is an indulgence! Indulge in it! That is all!

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 types of story feedback and what to do with each.

I’ve encountered a lot of feedback over the years.

Feedback that’s good, bad, or cocktail of both — from the 15 workshops I joined in college (including my time in the MFA) to my current experiences as a copywriter.

I’ve also learned how to get the most out of all that feedback. So this week I decided to share six types of story feedback and what do with each.

The Opinion is completely subjective feedback, and its purpose is to gauge what is and isn’t working for readers on a personal level. Isolated opinions offer some insight, but in general, you’ll want to pay attention to the patterns that emerge from multiple readers’ opinions.

Focus on: doubling down on the things your readers tend to like, and consider dialing back the things they don’t like.

Ignore: suggestions for phrasings, story elements, or plot directions that are purely a matter of taste and go counter to your vision.

The Misdiagnosis is feedback where the reader has noticed something wrong in your writing, but they struggle to identify the issue — so they “misdiagnose” the problem. It’s tempting to think this is a False Alarm (#6), but this type of feedback is actually very common and well intentioned, so be on the lookout!

Focus on: reverse engineering the true problem by closely reading the feedback and the passage it applies to. After identifying the real issue, work on a solution.

Ignore: their original diagnosis and any suggestions that are now irrelevant.

The Bad Remedy gets one step further than the Misdiagnosis. Here, the reader correctly identifies the problem, but the solution they provide either doesn’t solve the issue, is overly subjective (see #1), or has a negative ripple effect that the reader didn’t expect.

Focus on: determining a new solution that works for your story and style.

Ignore: any solutions that aren’t right for your story.

The Right Cure is the best kind of feedback, because it not only properly diagnoses a problem in your story, but also provides an effective solution. This feedback is easy to identify when it hits like a lightning-strike revelation — but sometimes the accuracy of the feedback or the tone of its delivery puts us on the defensive. We might try to write it off as an Opinion or False Alarm, but it’s important to accept the Right Cure when it’s offered.

Focus on: following the feedback. You can still tweak or build upon the solution if better ideas come to you; just make sure you’re still solving the problem.

Ignore: any temptation to dismiss the feedback out of pride or a feeling of being wronged due to an uncouth delivery.

The Divination is any feedback that provides the right solution to a problem, even when the reader misdiagnoses (or doesn’t try to diagnose) the problem itself. This often arises when a reader critiques mostly by feel, and while they may struggle to articulate why something is wrong, they feel something is wrong and are able to identify an effective solution. This type of feedback can often look like an Opinion since it lacks justification, but it’s always worth considering.

Focus on: identifying whether their suggestion improves the story, and if it does, implement it.

Ignore: the feedback if you’re confident it’s just an Opinion that doesn’t align with your vision for the story.

The False Alarm is feedback that tries to solve a problem that isn’t there. This type generally comes from a reader who’s distracted, reading too quickly, or trying too hard to find things to criticize (which can occasionally happen in formal critique settings like workshops, where some feel pressure to always contribute). Note, however, that this type of feedback is rare; what you think is a False Alarm is more often than not a Misdiagnosis, a Bad Remedy, or even a poorly delivered Right Cure.

Focus on: identifying whether the feedback actually is a False Alarm or something legitimate.

Ignore: the feedback, but only if you’re absolutely confident it’s a False Alarm. (If you find yourself receiving a lot of False Alarms, reflect on whether you’re dismissing too much feedback, and if you aren’t, consider looping in some new readers.)

Some Parting Rules of Thumb

Now that you have a grasp on these different types of feedback, I want to leave you with some general rules of thumb for revision:

Assume all feedback has the potential to improve your story, even if parts of it are misguided.

Know that everyone is capable of providing helpful feedback, even if they’re less experienced than you are.

Remember your vision as a writer matters, so don’t feel obligated to follow feedback that pushes your story in a direction that contradicts what you set out to create.

Never mistake the need for feedback as a shortcoming; instead, recognize it as an opportunity. Everyone needs feedback, but not everyone is willing to seek it out.

Good luck, and good writing, everybody! I hope this helps you sift through the feedback on your next story.

— — —

You have stories worth telling; I want to help you tell them well. For tips on how to hone your craft and nurture meaningful stories, follow my blog.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Why “Burnout” Is Okay - The Creativity Cycle

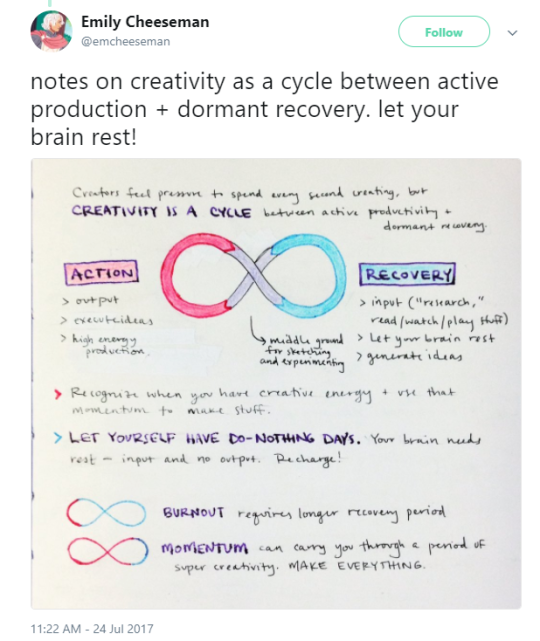

– One of the biggest fears writers face is burnout, or “writer’s block”. However, there’s always a way to look at the positives in a situation. Please take the following to heart: Not actively creating is okay, as long as you continue to your goals in another way.

Do not ever beat yourself up over not having the momentum to keep creating actively, 24/7. You need days where you relax and research and find inspiration. It’s not laziness. It’s an important part of the creative process. There’s a fabulous visual by emcheeseman on Twitter that was made for artists and explains this really well.

The Three Stages Of The Creativity Cycle

There are three stages to the creativity cycle; Action, The Middle, and Recovery.

The Middle Ground

If you’re coming down from the action stage, you’re not quite burnt out, but you’re also not as full of creative energy as you might have been last week. Your creations aren’t popping out as quickly and you’re finding that you take more breaks, do less in one sitting, and would rather take it slow and figure out some world building for upcoming scenes or write some experimental blurbs, rather than keep writing at full speed.

Or, if you’re coming out of the recovery stage, you’re not at 100% yet, but you have the motivation to do something, such as the activities I used as examples above.

During The Action Stage

You’re actively creating. You’re, how one would say, on a roll. Your visions and ideas are coming to life and you’re using all of your energy to create, rather than research or recharge. You should be using the momentum you’ve built up in the middle ground to write, and write a lot.

The Recovery Stage

You have had enough of writing for hours and hours at a time and you need some rest. Your brain is tired and you’re finding it more difficult to get excited about your project. It’s time to let yourself breathe. Give yourself time to do absolutely nothing, distance yourself from your project, and take in some material to help you get inspired again.

You need to input content into your head. Read, watch tv shows, watch movies, go out in the world, try new things, have new experiences, visit new places, etc. This is super important to this stage. If you don’t consume other work or things that will help you generate ideas once you have the energy again, you will not bounce back to the high energy production phase you hope to be on again.

So What?

Just remember that creativity, no matter what art form you practice, is a cycle that you can’t stop in one place. Nobody can always be in a place where they can happily create every single day without faltering. You’re human, you’re an artist, and you need to accept that there are multiple ways you can work toward your goal, even when you’re “burnt out”. It’s all part of the process.

Happy writing!

Support Wordsnstuff!

If you enjoy my blog and wish for it to continue being updated frequently and for me to continue putting my energy toward answering your questions, please consider Buying Me A Coffee.

Request Resources, Tips, Playlists, or Prompt Lists

Instagram // Twitter //Facebook //#wordsnstuff

FAQ //monthly writing challenges // Masterlist

MY CURRENT WORK IN PROGRESS (Check it out, it’s pretty cool. At least I think it is.)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

For all the jesting in the final post, this is 100% how I get myself out of a block. For me, blocks are either caused by lack of confidence, or they lead to a lack of confidence (much as the OP says in the art context - the block doesn’t stop you from writing, it stops you from producing prose the way you want it). I invariably go back to basics, which for me is burying myself in writing advice (podcasts, books, articles): listening to other people on aspects I think are holding me up, or just learning about things I haven’t thought about before, which allows me to think about something other than the issue holding me up. So, for example, if I’m suddenly having a breakdown about whether I’m showing (rather than telling) too much or not enough, I’ll go and read an article on that….or I might read an article on creating vivid characters, because that will get me excited about writing again. Either way, going back to basics always helps.

just so yall know

art block is your brain telling you to do studies.

draw a still life. practice some poses. sketch some naked people. do a color study. try out a different technique on a basic shape.

art block doesnt stop you from drawing, it stops you from making your drawings look the way you want them to. and thats because you need to push your skills to the next level so you can preform at that standard

think of it as level grinding for your next work.

144K notes

·

View notes

Photo

If you try and figure out the rules about creative writing, you’re going to find that established authors and editors often disagree about nuances of the craft. There are, of course, some hard-and-fast rules about punctuation and grammar, but so many rules vary from genre to genre, generation to generation, audience to audience. Sometimes there are rules that boil down, simply, to consistency.

So you might even say that you have your own set of writing rules. Each and every author’s rules are slightly unique. That unique set of “rules” is part of what makes up your author’s voice.

So when are the appropriate times to break those rules, your own rules? They happen, don’t they? In my last post, I gave a list of filler words and overused words that you can consider cutting out of your writing to help sharpen it. But everything–even mediocre vocabulary, poor grammar, and repetitive structure–has a place in writing.

Breaking Your Mold to Write Character Voice

Jordan is an author (hypothetically). She has been writing for years, gotten an English degree, read a zillion books, and written several novel drafts of her own. Over her years of writing, she has finally come into her own voice. When she writes, she no longer feels derivative or inexperienced. It’s freeing and wonderful!

But there’s one thing that Jordan hasn’t figured out yet…and that’s character voice. Her authorial voice, while wonderful and unique, seeps into the voice of all of her characters. The result is that all of her characters, whether speaking or narrating, sound exactly the same: they sound like her.

Part of what makes a multi-POV novel come to life is variation in character voice. Part of what makes an author’s portfolio stand out is the vast scope of voices their characters use across their works. Part of what sets apart side characters as characters instead of tools for the protagonist or plot devices for the narrative is a unique and compelling voice.

So how does one accomplish such a thing?

Well, there are many ways. But today I’m focusing on language and syntax, particularly in the rule-breaking department.

The first exercise you can do is take a piece of dialogue, preferably just a back and forth between two characters, and write it one way, then switch roles. Have the characters say basically the same thing, but in their own voices.

Author Voice Conversation

R: Oh. You’re worried about me

E: I am no such thing. Worrying about you sneaking into enemy territory is like…worrying about a fish drowning in the ocean.

R: You sure seem dead set on stopping me from going.

E: We need to come up with a plan. It would be foolish to just waltz into their territory with no idea what we’re doing.

R: You’re really quite cute when you’re worried.

E: You’d like me to be worried, wouldn’t you? Just go. I don’t know what I’m freaking out about, anyway.

R: Me either. Bye.

E: Bye, idiot. Don’t get caught.

R: *sigh* Is that really what you expect of me?

There’s nothing wrong with this conversation at all. But I’m just writing as if I, personally, was speaking. I know what the personality of these characters are, but that isn’t necessarily enough. I’m going to inject a little bit of their own tics, their own backgrounds, into their speech.

Character Voice Conversations

R: Oh. You’re worried about me, aren’t you?

E: Really? Please. I don’t worry about anyone.

R: But you don’t want me to go.

E: I just…think that we need to come up with a plan first.

R: You’re really kinda cute when you’re worried.

E: I’m NOT—Grah! Fine! Go, then. I don’t know why I’m trying to help you, anyway.

R: Neither do I. I sure as hell didn’t ask for it.

E: See ya, then. Try not to get blood on my shirt.

R: Go drown in the tears of your unborn children, Tiger.

And now, roles switched:

E: Heh. You’re…worried.

R: Fuck off. I don’t have energy to waste worrying about you.

E: You want me to stay. Safe.

R: I mean…having a plan would be a good idea, but what in hell do I know? The fuck are you doing?

E: You’ve got some worry on your face.

R: Don’t touch me. Don’t even talk to me. I’m sorry I mentioned anything about a plan.

E: So am I. I’ll bring you skin of an atosh as a trophy.

R: Bye, Tiger. If you’re not back in one day, I’ll assume you died.

E: Don’t wait that long. I’d love to come back and find peace and quiet waiting for me instead of you.

What sort of things influence the diction of your characters? In example 1, R says, “You’re really quite cute when you’re worried,” whereas in example 2, she says “kinda,” instead. In both of the latter examples, R is more prone to using “fuck” and “hell.”

In one of my novels, I have two narrators: K and B. K is well-read, well-spoken and a little snobbish. B isn’t an idiot, but he dropped out of school in (what amounts to) the fifth grade. He’s spent a large portion of his life outside of society and largely lived his life how he wanted. So when they say basically the same thing, K might say,

“I’ve got this covered. Thank you, but, honestly, it isn’t anything to worry about.”

Where B would say,

“I’ve got this. For real. Thanks.”

In general, as I write their dialogue, B uses more contractions, shorter sentences, and doesn’t use many words beyond the 1000 most commonly used. He makes grammatical mistakes (Saying “me” when he should say “I”) He has more verbal tics, “Um…” “Er–” “Well, it’s just that…” etc. K speaks with much more flowery language and tends to elaborate beyond what is necessary. This means unneeded adverbs, “moment,” “rather/quite/somewhat,” superfluous reflexive pronouns, etc. I have one character who tends to speak in run-on sentences whenever she uses the word “because.” I have one character who compulsively addresses the people he’s speaking to, so much so that other characters make fun of him for it.

These are all things that, in general, I avoid doing. But using them purposefully helps to set character voices apart.

Narrator Voice

To some extent, narrator voice can use these same tactics. If you’re using multi-pov, especially, these kinds of nuances will help your reader really feel like they’re reading the words of multiple characters, rather than just being told they are. If you’re writing an intimate third-person or first person, these same principles can help bring your narrative voice to life, just like the words written in quotes.

Think about these two opening lines and how the voice of the narrator gives you two very different impressions about the same event:

The sun was rising. Though the scent of the overnight dew hung heavy over our tent, the sleeping bag hugged us close together. She smelled warm, and even the scent of our intermingled sweat was pleasant in the early morning. I wondered briefly if the residual alcohol was softening reality, but ultimately it didn’t matter. I was in love.

The sun was coming up. The air was heavy, humid in the muggy morning. Our sleeping bag was wrapped tight around us, the moisture from our breaths clinging around our heads. Sticky and warm, she still smelled like sex. It was probably an objectively terrible smell, but the memories made it nice. I blinked, wondering if that last glass of wine was still hanging over me, but I don’t guess it mattered. I fucking loved this girl.

So think about it! There are tons of factors that could go into how your characters speaks…and thus, what “rules” you break in their dialogue.

How educated or well-read is your character?

What influence does their culture have on their diction?

How wordy do they tend to be?

If they use as few words as possible, maybe mostly grunts, what is the motivation behind that?

How much attention do they like to bring to themselves?

How self-conscious are they about their voice? Their speech patterns? The effect their words have on others?

How long does it take them to get to the meat of what they’re saying?

How much do they make others laugh?

How optimistic or pessimistic are they?

How much do they try to avoid talking about themselves or their emotions?

At what point do they end a conversation they don’t like?

How long does it take them to get angry in a disagreement?

How does anger alter their speech?

How does overwhelming sadness alter their speech?

How does immense joy alter their speech?

What words do they use with noticeable frequency?

Do they speak differently in intimate settings than in public?

Don’t be afraid to use any and every word to give your characters their own voices. As I always say, to anyone in basically any situation: I don’t mind if you break any rule at all…as long as you broke it with deliberated intent.

Happy revising!

767 notes

·

View notes

Text

Behold, A Writer

I’ll get there.

806 notes

·

View notes

Text

….I think this may have just opened up a whole new way of thinking for me.

Drafting: How Not To Do Too Much At Once

I’m about to drop several posts on you about drafting. But drafting is a hard thing to generalize about, because everyone needs their own peculiar system. I only have one piece of advice I give to everybody: draft in a way that doesn’t make you do too much at once.

Let me explain.

A story is unbelievably complex. Each new sentence you lay down involves any number of factors: what your character is thinking, feeling and doing, what’s happening physically in the scene, what other characters are thinking, feeling and doing, what the setting looks, sounds and smells like, what’s happening on a more macro plot level…to say nothing of tone and narrative voice, imagery, word choice, sentence rhythm…etc. I don’t mean to get all dramatic about it, but that is so much shit to think about!

Luckily, you deal with most of it unconsciously. I’m not a psychologist, but my sense is that many of these disparate considerations get funneled into a gestalt of some kind, without our even realizing we’re synthesizing them. That’s why we can write at all. If this unconscious synthesis didn’t happen, our brains would crash every time we tried to write a single word.

The problem—and this is crucial—is that not everything winds up in that gestalt. You can’t unconsciously synthesize everything about your story. So, you might be wrestling with what your character is feeling while also trying to vary your sentence length. Or you might be working out the details of the physical setting while also trying to find your narrative voice. You might not know that’s what you’re doing; in fact, you probably just experience it as this is really fucking hard. But that’s why it’s hard: you’re trying to do too many things at once.

The solution is to break down this incredibly complex task of writing a story into separate tasks and do them one at a time.

This can take an almost infinite number of forms. Look at our most recent process poll and you’ll see three of them. The writer whose first draft is mostly dialogue, for instance, deals with what the characters are thinking and feeling first and works that out on the page via the dialogue. However (and correct me if I’m wrong, @incognitajones ) there’s a lot more in her head for which the dialogue acts as a placeholder, and with the dialogue in place, she can then flesh out the character interactions with interior monologue, physical/gestural business and all the rest, plus anything going on around the characters. The dialogue works for her like a sketch works for a painter: it puts one element of the scene in place and also shows her where all the other elements will go.

I work a little differently. In my drafts, all of the elements of a scene are present except the actual words I want to use in the story. It’s as if I’m making a very detailed outline. I write what happens, what the characters are thinking and feeling, all that stuff—but I write it as if I’m explaining to you what I’m going to write. Then, when I revise, I translate that chatty outline/description into the narrative voice of the story. Because I can’t work out what’s happening in the story and come up with a good way to say it at the same time, I have to do those things separately.

To you, that might sound bizarre. Everyone’s gestalt is different, so tasks that can be separated for one person might be inseparable for another. You might say, “How do you write the story without involving the narrative voice? The story is the narrative voice!” If that’s how your writerly mind works, that’s fine! The trick is to discover these things about yourself and then develop a drafting method that respects the way you think.

I used to hear other writers describing their drafting methods and wonder if I should be doing it their way. I thought certain methods indicated a more genuine literary talent than others. Now I realize what bullshit that is—but you know what? Even if it were true, it wouldn’t matter. Your method is your method. It’s what you have to do to get the work done. There are no “good” or “bad” drafting methods, no “pure” or “impure” ways to write—just ways that work for you and ways that don’t. We don’t have time to worry about how we should write. We gotta face reality and find ways to get the job done with as little pain as possible.

When I switched from my “every word is agony” method to my chatty outline method, I felt like a new person. Like I’d gotten ten years younger. I could have lifted a school bus, I swear to you. I immediately did one of those magical girl transformations and defeated a supervillain. All because I’d figured out a way to reduce my cognitive load and stop forcing my brain to do things it didn’t want to do.

Next post: drafting methods you can try

Ask me a question or send me feedback!

357 notes

·

View notes

Text

The most important writing lesson I ever learned was not in a screenwriting class, but a fiction class.

This was senior year of college. Most of us had already been accepted into grad school of some sort. We felt powerful, we felt talented, and most of all, we felt artistic.

It was the advanced fiction workshop, and we did an entire round of workshops with everyone’s best stories, their most advanced work, their most polished pieces. It was very technical and, most of all, very artistic.

IE: They were boring pieces of pretentious crap.

Now the teacher was either a genius OR was tired of our shit, and decided to give us a challenge. Flash fiction, he said. Write something as quickly as possible. Make it stupid. Make it not mean a thing, just be a quick little blast of words.

And, of course, we all got stupid. Little one and two pages of prose without the barriers that it must be good. Little flashes of characters, little bits of scenarios.

And they were electric. All of them. So interesting, so vivid, not held back by the need to write important things or artistic things.

One sticks in my mind even today. The guys original piece was a thinky, thoughtful piece relating the breaking up of threesomes to volcanoes and uncontrolled eruptions that was just annoying to read. But his flash fiction was this three page bit about a homeless man who stole a truck full of coca cola and had to bribe people to drink the soda so he could return the cans to recycling so he could afford one night with the prostitute he loved.

It was funny, it was heartfelt, and it was so, so, so well written.

And just that one little bit of advice, the write something short and stupid, changed a ton of people’s writing styles for the better.

It was amazing. So go. Go write something small. Go write something that’s not artistic. Go write something stupid. Go have fun.

148K notes

·

View notes

Text

Editing Tip: How to Speed Up or Slow Down Your Pacing

Hey friends. I’ve been thinking a lot about pacing lately, as I’m in the process of editing a few of my own stories, which tend to be too slow in the beginning and too fast in the end. Fortunately I have a ton of experience speeding up or slowing down pacing when I edit my clients’ manuscripts, and I wrote up a whole section about it in my book The Complete Guide to Self-Editing for Fiction Writers.

One important thing to keep in mind about pacing is that there’s no one “right” pace—each story and genre need something different. A crime thriller will usually have faster pacing than a character-driven literary novel; language-focused writers will usually create slower-paced stories than plot-focused writers. So when you’re revising your pacing, It’s about finding the right pace for your story.

At the same time, remember that stories generally build in tension, continually ramping up the conflict until it crests at the climax and falls at the resolution. While you’ll want some ebbs and flows in tension so the reader doesn’t get completely exhausted, the story shouldn’t feel resolved for too long without introducing another problem or further complicating the conflict.

A story’s pace is controlled by a number of factors but luckily, there are pretty much only two problems you can have with your pacing. A story can be too slow (which usually feels boring), too fast (which can produce a lot of anxiety), or a combination—too slow in some parts, too fast in others.

In either case, you’ll need to learn how to put the brakes on or apply the gas as needed to moderate your pacing.

Speeding Up Slow Pacing

If we feel the pacing is too slow, it’s usually either because a scene is too long, too wordy, or not enough is happening. The result is a sense that the story is dragging, and a lot of yawning on the part of the reader. When the pace feels slow, we will naturally start to skim or read ahead to find out “what happens.”

Let’s look at how to address each of the three main causes of slow pacing.

Too long. Sometimes the pace feels slow because your scene is simply too long. To remedy that, you might need to start the scene later, end it earlier, or cut slow transitions where not much is happening. Shorter sentences and more frequent paragraph or scene breaks can also help to break up a lengthy scene and make it feel like it’s moving faster.

Too wordy. The more words you use, the slower the pace. Long passages of description, excessive dialogue or inner monologue, info dumps, repetition, and filler words are often to blame. If you simply can’t bring yourself to cut excess words, you can also try breaking up long sentences or paragraphs to give the illusion of a quicker pace.

Nothing is happening. A lack of goals, conflict, or stakes can lead to the feeling that “nothing is happening” in a story. Has your character slipped into the bathtub to ruminate at length on an issue that she’s already mulled over a thousand times before? Have you used five pages to detail a long, boring traveling sequence that should’ve been summarized in a few sentences of transition? If your scene has scant conflict, and no change by the end of the scene, it may need to be rewritten or cut in order to improve your pacing.

Slowing Down Fast Pacing

On the other hand, if a story’s pace is too fast, an excess of action and dialogue are usually to blame, as well as short, choppy sentences, and a ceaseless maelstrom of conflict. In that case, you have the opposite problem: Your scenes are either too short, too shallow, or too much is happening.

Too short. Short sentences, paragraphs, scenes, and chapters pick up the pace of a story, but can leave readers exhausted when overused. Mix it up, using longer sentences or paragraphs slow the pacing where needed. You can also lengthen action- and dialogue heavy scenes by adding brief spurts of description, inner monologue, or narrative summary.

Too shallow. An action-paced scene often skims over the deeper, more nuanced aspects of the story like theme, emotional depth, and character development. If your too-fast pace is the fault of a flat character, take a moment to let readers know what’s driving her with a few sentences of interiority or narrative summary. The more readers feel like they’re inside your protagonist’s mind and heart, the deeper and slower your scene will feel. Description can also help give depth to a shallow scene—all that action and dialogue isn’t taking place in a vacuum, and writing it that way can shift your story into turbo speed in no time at all.

Too much happening. If your protagonist is fighting off a centaur in a crowded marketplace, resolving a longstanding resentment with her brother who works at the tomato stand, looking for a choice hiding place for a trunk of buried treasure, wooing the delivery boy, and realizing the true nature of love and war all in the same scene, you might need to dial it back to control your pacing. Decide which storyline is the most important to highlight, and push all the others into the background or save them for another scene.

No breathers. If the protagonist never gets a chance to catch her breath, readers won’t either. Look for places where she can pause and reflect, like right after a problem is resolved or a new one is discovered, when new information is revealed, or as your character undergoes an important internal change in her motivation or perspective.

Hope this helps!

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

I always struggle with ending scenes, and suspect a lot of these apply equally to ending scenes as they do to ending stories. What do I want the reader to take away from the scene? Why was it important? Do I suddenly want to yank the rug out from under the reader’s feet to create some suspense that’s going to carry me through the next few scenes? Very helpful list!

I was wondering if there's any thoughts about the last line of a story, be it short or long one, it seems like the last line always eludes me, always feeling the pressure to make it meaningful or somehow final, makes it so very hard to pick! Thank you for all your wonderful advice 💖

Hi :)

How to write the last line

Oh yeah, the elusive last line... the line that ends your whole story and probably the one that gives your reader the emotion they take away from the story.

I would say that you should start by deciding on what you want the reader to take away from the story and if you want the story to be finished, to give a preview of the next one, or leave it relatively open.

So, some options for the last line are:

conclusion/closure - the true last line, the one that finishes up the whole story, without plans for the future or leaving things open

summary - the last line sums up the theme of the whole story

answer - using the last line to answer a question the story started with or that came up during the story

question - ending with a question about something that happened or something that will happen, can keep the reader thinking about the story and their message long after they closed the book

cliffhanger - leaving the reader hanging, not a real ending per se, reader has to read the next story to find out what happens

open end - different to cliffhanger, showing that the fate is not decided yet or leaving it open to the reader’s interpretation or fantasy, it’s a nod to the character’s future, which can lead into the next story, but can also be the end and the character lives that future we get a glimpse of without us

plot twist - everything seems fine, the evil was defeated and the story can end happily, but then the last line turns everything on its head and reveals that it’s not fine and it’s actually the worst possible outcome

the first/last line - using the same line or mirroring the first line you used in the story is a clever way to bring it full circle or get the reader to think about what and how much things have changed since that first line and if the line even means the same thing now after everything that happened

I hope you get to write quite a few of those famous last lines! Good luck!

- Jana

975 notes

·

View notes

Text

@yucadoodledoo always produces such pretty art! Absolutely adore the colours and Sabina’s hair and the way the countdown’s incorporated…!

6 more days to go till season 2 drops !!! so hyped 🙈🥳 here's my piece for the countdown:)

39 notes

·

View notes