Text

There have been a lot of hot takes following the journal eLife's announcement that they will get rid of peer review . Most have been doubtful or weirdly filled with righteous outrage; the supportive takes have been mostly lacking in clear reasons for support. This Twitter provides some more concrete food for thought about the process of peer review, and why it might be time to transition away from it. https://twitter.com/JACoates/status/1583822377498341377?t=mUJ_2HCvc1AXZ2lnlqIV-Q&s=19

0 notes

Quote

In this lab, mistakes are expected, respected, inspected, and corrected.

#one of my favorite quotes#I can't remember where it's from#but it's awesome.#quotes#inspirational quotes#science quotes#mistakes#failure

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I consider my graduate students my colleagues.”

This is a sentiment I have heard from graduate advisors. The intent behind this statement is generally positive; it is often meant to be uplifting to graduate students, to let them know that their mentor respects them and that they consider themselves on an even playing field. However, I think statements like this belie an ignorance on the part of the mentor.

Firstly, this kind of statement blatantly disregards the power dynamic in mentor-mentee relationships in academia. One part inherently holds more power than the other--- in particular, decisive job power. A graduate mentor can kick a student out of their lab, colleague or no. A graduate mentor can ignore a student’s wishes and give them a shitty project, colleague or no.

Secondly, I would argue that, no, in the traditional sense, a mentor and mentee are not colleagues, and that is 100% okay. According to Merriam-Webster, the definition of “colleague” is: an associate or coworker typically in a profession or in a civil or ecclesiastical office and often of similar rank or status. The graduate student is not of a similar rank or status as the graduate mentor, and that is the whole point. The student is there to learn from a higher-ranked, more experienced individual.

And, ultimately, it doesn’t matter if you (the mentor) consider your graduate students “colleagues” unless they also consider you a colleague.

Whether a student considers their graduate mentor a colleague depends on a variety of factors, including: Their experience level, their status as a graduate student, and their gender identity.

For example: When I asked fellow female graduate students whether they thought of their mentors as “colleagues” they answered with a vehement “no” (and most of them looked rather perplexed by the question). When I asked the same question of male graduate students, they generally answered: “I mean, yeah, sure.”

As another example: At the very beginning of my graduate studies, I would not, under any circumstances, feel comfortable calling my mentor a “colleague”. As far as I was concerned, they were my “boss”. Why did I think that? I was young. I was inexperienced. My knowledge base was very small by comparison to my mentor’s. And, further more, I worked for him.

However, now, as a 6th year Ph.D. candidate, I find myself thinking of us more as equals. Why? I’ve gained in experience. My knowledge on my own research topics exceeds that of my mentor’s--- I am the authority on those subjects. And, now, I don’t work for him--- I work for myself.

My point is that a graduate mentor shouldn’t use a blanket statement like this to convey a sense of collegiality. Mentors should be aware of the status that they occupy in the eyes of students and handle it accordingly. A mentor can, and should, show their students respect and try to bolster their confidence: But that should come through levelling with the student, teaching them, and giving them confidence in themselves and their work.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

a succinct definition of premotor cortex function:

“That is, while it does not directly drive muscle specific responses, it plays an invaluable function: it sets the stage for action by making some actions more or less likely. In other words, it influences motor function by potentiating or depotentiating actions.”

- Fine & Hayden 2021. “The whole prefrontal cortex is premotor cortex”

0 notes

Video

@tomlumperson 🦇 Mustached Bats vs The Doppler Effect #learnontiktok #science101 #cogsci

♬ original sound - Tom Lum

tiktok

This is probably one of my favorite TikToks of all time.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

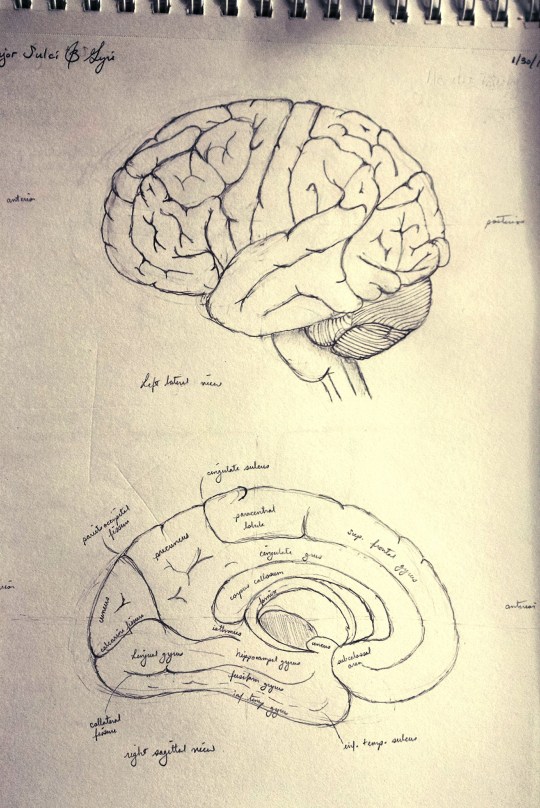

Drew some brains for neuroanatomy class. On the top, you have a left lateral view with all typical gyri and sulci. On the bottom, a right sagittal view, same. I still need to finish labeling.

1 note

·

View note

Link

“History demonstrates decades of strong bipartisan support for NIH research, a trend that should be sustained.... Less well known, perhaps, is the reality that America’s medical research sector has been a powerhouse of jobs and economic returns in every state for decades — precisely because we have invested in maintaining the nation’s status as the world’s leader in biomedical research.”

1 note

·

View note

Conversation

me: *writes adult email*

me: *hits send while screaming loudly*

289K notes

·

View notes

Photo

How I’m feeling about finals right about now.

0 notes

Link

Ever wonder what a dead fish has to do with statistics and neuroscience? Click on the link to find out!

0 notes

Text

panic! at the deadline

741K notes

·

View notes

Link

This is actually something that, as a young scientist, I worry about a lot. Not only does it make parsing through articles and research difficult (having to constantly wonder if you’re reading something legitimate) but it degrades scientific study as a whole. Is this indeed a crisis? This article (and the associated paper) picks specifically on the “soft” sciences -- psychology, humanities, sociology-- where small sample sizes are fairly normal. Do we have reason to be concerned in other areas, as in the STEM sciences? I would argue yes. The pressure to produce novel and titillating results exists in all fields. Remember the Columbia scandal? Yeah. Still happening. You can get the latest of Nature retractions here.

The push to “publish or perish” isn’t the only peril faced by researchers, particularly those in academia. Many professors must successfully mentor and produce future scientists. I am talking, of course, about graduate students. Programs are required to set up guidelines and milestones that students must pass in order to matriculate. This should theoretically either a) weed out anyone who is just not cut out for it, and b) instill some sort of rigor in training.

My personal experience and conversations I have had with other students and a few professors tells me that this system is flawed. Students are pushed through programs and are graduated whether or not they truly have gained the skills to be a successful researcher, much less one with integrity. This in and of itself does not bode well for the future of science.

Thoughts?

#peer review and scientific publishing#science#psychology#research funding#research#academia#mentoring#publish or perish#replication crisis#reproducability crisis

1 note

·

View note

Link

When you think about it, the vocalization and auditory learning capabilities of birds is pretty incredible, given their brain size. However, as we know, small does not necessarily mean simple.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

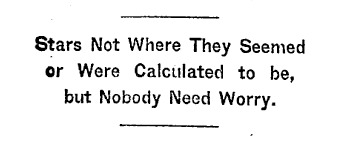

An actual headline from The New York Times in 1919

186K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to: Contact a Professor about Lab Rotations

In my little rant about Lab Rotations a few days ago, I neglected to mention how I was actually getting in touch with people. This may seem like a no-brainer (hehe) but I’d rather post this and maybe help someone out. I’m aware that a lot of people deal with anxiety when it comes to talking to strangers, especially strangers you are trying to impress.

First of all, email is usually the preferred mode of communication. Almost no professor I know picks up their phone unless they’re expecting a call.

Secondly: in my experience, the best things to include in an email about rotation are...

1. Formally address the prof, as in “Dr. Smith” or “Dear Dr. Smith”. I know a lot of professors that insist everyone call them by their first name, but I like to establish that formal respect from the get-go (and it’s common courtesy); if the professor replies with their first name only in the signature line, then I will call them by that name.*

2. Tell them who you are. Something along the lines of “I’m a first year student in the ___ program” will suffice. Also, tell them (in a phrase or term) what you’re interested in. I usually tell them I’m interested in “systems neuroscience, with an emphasis on audition”.

2.5. Tell them why you are interested in working with their lab. This is actually optional, given the above, so I’m listing it as 2.5. You can incorporate this into 2.

3. Ask them a) if they are currently taking students, and b) to set up a meeting to discuss current research and rotation projects. This is the point of the email; you really want to talk to people in person about their research and rotation projects. It also gives them an opportunity to evaluate you, your personality, strengths, skills, experience, etc.

4. Sign off in your typical polite manner. A “Thank you for your time; I look forward to your response” is perfectly fine.

Okay. So you’ve got a meeting set up. A few recommendations for said meeting:

1. Dress moderately nice. More difficult to do in hotter weather, but make an effort. You may be accepted into the program, but no one likes to meet with a slob.

2. Familiarize yourself with their research. Theoretically, you would have done this previously, but I would recommend reading their faculty profile AND 1-2 articles they’ve recently published. Take notes.

3. Have questions prepared. Research-related questions are best, but other questions about working in the lab, if phrased correctly, are also fine. I would have at least 5 questions at the ready.

4. Practice telling them about your interest. True story, I did prepare this point, and totally put my foot in my mouth. But still.

5. Don’t stress it. The professor will not expect you to be an expert in their subject area. That’s what you get a Ph.D. for. Just make sure you communicate your interest.

And there you have it.

#PhD advice#grad school advice#lab rotations#grad student advice#grad advice#graduate school#grad school

0 notes

Text

Orientation Week

I am trying my very best not to overtly insult anyone or make a complete ass of myself but, well. I think my foot basically lives in my mouth. And people are very sensitive.

0 notes