Video

youtube

my first very rudimentary attempt at animation.

0 notes

Text

(B)Rats!

At one point in my early twenties, all my girlfriends seemed to collect other people’s children as though they were their own. Every coffee or dinner get-together resulted in listening to them regale me with so-and-so’s adorable child and the incredible excursion they’d just been on.

“Charlotte and I went to the ROM.” Laurie boasted, “She showed a deep understanding of the Ramapithecus stage of human development,”

These children always had names like Gwendolyn, Bronte, or Charmaine and invariably spoke two languages fluently as well as being proficient on the piano or violin. Every kid was a genius from what I could tell. My takeaway from these encounters was that my friends were using these experiences to show how grown up and responsible they were. But beyond that, how loved. After all, if children adore you, that’s saying something – right?

“Look,” Laurie insisted shoving a hand-made card in my face with glued elbow macaroni on the cover. “Bronte made this for me. Inside it says, You are the best!”

Back in my apartment while contemplating whether glue traps were a humane way to handle my overwhelming mice infestation, I thought that perhaps I should try to endear myself to some children. Clearly, this was the next step towards adulthood, and like learning how to drive, I didn’t want to be left out. Also, I figured any child would confirm what I already suspected, that I was the next best thing to Mary Poppins. In no time at all, they would call me “auntie” and beg their parents to spend time with me.

I quickly made a list of all the people I knew with children under the age of seven and the next day reached out to see if anyone was interested in my shepherding their kids around Toronto for a few hours of fun. “I have tickets to see the Nutcracker,” I told my grown-up friends, Eric and Allison. They had a daughter named Mary Jane, whose nanny had to have emergency dental work on the very week they’d planned a romantic getaway, so they were only too thrilled to lend their precocious six-year-old to my cause. This struck me as perfect timing. Their home was beautiful and their fridge was well stocked. Not only would I enjoy spending time with an insightful child, but I’d be well-fed in the process.

“She’s gluten, dairy, and sugar-free,” Allison told me handing me a plastic bag of celery and carrot sticks. “She’s also allergic to peanuts, bandaids, and perfume.“ Here’s the number where we can be reached and the telephone number of her therapist.”

“Your six-year-old has a therapist?” I asked. I imagined myself bragging about Mary Jane’s incredible interpretation of Rorschachs and fascination for dream psychology.

“Speech therapist,” Allison said, as she ushered the youngster into the room.

If it were possible to pour cream of wheat into a mold and have it set, then one might have an impression of Mary Jane. She was pale, thin, and dressed from head to toe in bubble gum pink.

I looked at the child and it crossed my mind that I’d been given a dud.

“Do you speak two languages?” I asked her

“I can thpeak thom pig Latin.” she volunteered.

What about musical instruments?

“Only the gathoo.”

MJ, why don’t you tell Lezlie about your part in the Christmas Play. Lezlie is a writer, you know.

You’re in a play, I asked, suddenly interested.

“A Chrithmath Carol.”

“She’s Tiny Tim.” Allison volunteered.

Mary Jane seemed like a sweet if not meek six-year-old with a nose that always ran and hair that stayed limp, even after it had been washed. As her mother and father loaded up their Cabriole with a few overnight bags, she sat listlessly colouring a picture of a mouse sitting on top of a pile of presents.

“What a sweet little mousie,” I said doing my best to ingratiate myself.

“Ith’s not a mouth.” Mary Jane announced in a tone that suggested I was an idiot. “Ith’s a rat.”

Allison interjected, “Ever since the movie Ratatouille, she’s been very excited about rats.”

“Is that so?” I said, all the while wondering how I might be able to parlay this information into something useful. I wonder if she knows anything about extermination, I thought to myself.

“Here’s the number of the Inn we’ll be at,” Eric said. “Call if there is an emergency. Bye Bye MJ” and they were off.

“Well,” I said to Mary Jane, “Shall we get ready to see the Nutcracker?”

“What’s that?” Mary Jane asked

“A ballet.”

“What’s that?”

“A kind of dance piece.”

“I hate danth.”

“But there are pretty costumes and classical music.”

What’s that?”

I looked at the clock. Only 48 hours to go.

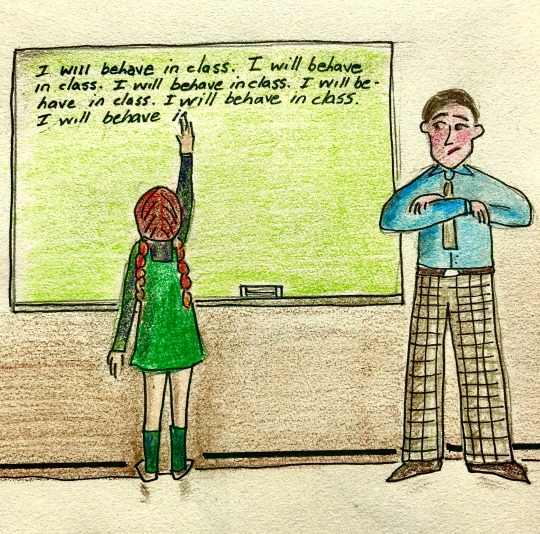

At the theatre, Mary Jane informed me in no uncertain terms that I was boring, thtupid, and ugly. I had no idea that little children could be so cruel. I wanted to sink to her level and say, “I know you are, but what am I?” But we had until Sunday and these were early days.

To break the ice I volunteered a little bit about myself in the hopes that it might impress her to like me.

“So your Dad mentioned that I’m a writer?” I asked

“My dad thinks that writerths are just unemployed bums.”

Out of the mouths of babes.

“Look,” I said handing her a kleenex, “Maybe you’ll like the dancing. Let’s try to have fun.”

“What’s that?” She said as the orchestra tuned up and the lights dimmed.

Here’s what I remembered about the Nutcracker. There’s a little girl and a huge Christmas tree and a Nutcracker Prince and a Rat King.

Here’s what I forgot about the Nutcracker. The Prince defeats the Rat King who is dragged away, unconscious by his minions. At intermission MJ was hysterical.

“Ith he dead?” She started screaming. “Ith the Rat King dead?”

“No!” I said, “Just unconscious. He’s fine.”

“He’s NOT fine,” she screamed. “I hate the Nutcracker. I hate him. I HATE HIM!!!!”

An usher made her way over to us. “Is there anything I can do to help?”

There are people, and you know them, who naturally assume that in ANY given circumstance they would be more useful than you.

“We’re fine,” I said doing my best to diffuse the situation.

The usher started talking to Mary Jane directly as though I were her captor and had forced her to the ballet.

“Is that true? Are you okay little girl?”

“I HATE the Nutcracker!” Mary Jane screamed. Now everyone was looking at us.

You have to understand that at this point Mary Jane’s ire had worked its way up from a four to an eight and the more attention she got from the ‘well-meaning’ usher, the more MJ screamed. Front of House was called.

“Now, now,” he said, “what seems to be the problem?”

“I think I’d better take her home.” I volunteered trying to get Mary Jane's arms into her coat as she flailed about.

“Is this your mommy?” The Usher asked.

“NO!” Mary Jane screamed

“Do you know this lady?”

“NO!”

All eyes were now on me.

“I’m babysitting.” I sputtered. “Her parents are away for the weekend and I’m taking care of her.”

“Is that true?” the usher asked Mary Jane who stopped sobbing just long enough to nod.

The lights in the foyer flickered.

Act two is about to begin. Please take your seats A disembodied voice announced, and the lobby slowly emptied back into the theatre.

Mary Jane and I left the building under the watchful eye of the well-meaning usher who was still taking a mental picture of me for the police report she’d be filing later that night.

Back home Mary Jane was still distressed. Surely I was the worst babysitter on the face of the earth having traumatized a six-year-old for life.

“Look,” I volunteered carefully so as not to set her off, “I’m a writer, as you know, and though you may have an accurate, although brutal opinion of me, occasionally it pays to be able to use the pen as a kind of sword.”

Mary Jane looked up at me from her pillow.

“What do you mean?”

“What if I write a letter to that Nutcracker and insist that he apologize to the Rat King for any wrongdoing and —

“Give him back his crown.” Mary Jane interjected.

“Yes,” I agreed, “Give him back his crown. I’m sure between the two of us, we could come up with a great letter to that phony bologna that would set him straight.”

We worked for the better part of an evening and this is what she came up with:

Nutcracker,

You are a mean, horrible, nasty, sniveling, block of wood. How dare you wound the Rat King that way. Do you have any idea how valuable Rats are? Did you know that rats outperform humans in cognitive tests? They are affectionate, and empathetic and can even laugh when tickled.

Because they drop seeds rats are also great for the environment by planting trees everywhere they go. What do you do? Hmm? You crack nuts. Big deal. I can do that with my shoe. I think you are just jealous of the Rat King. Please consider your behaviour and apologize at once and leave the Rat King alone.

Sincerely,

Mary Jane Higgins

“That’ll do the trick,” I lied. “You really told that Nutcracker where to get off.”

“What’s that?” Mary Jane asked

“Never mind,” I said. “Let’s order pizza.”

I wish I could say that from that moment on, Mary Jane and I were friends. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened. What actually happened was a week later her grandmother, completely unaware of what had transpired, took Mary Jane to see the Nutcracker again. Of course, MJ went, convinced that her letter had changed the outcome by making the Nutcracker see the error of his ways. When, of course, it didn’t…she had another meltdown in the lobby of the Hummingbird Center while the well-meaning usher questioned her grandmother’s legitimacy amid Mary Janes screams of, “I hate the Nutcracker. I HATE HIM!!!”

As for me? Since Mary Jane had educated me about the psychology of rodents, I found myself incapable of ending my mice infestation and eventually had to move.

0 notes

Text

A Breath of Fresh Air

The summer after my first year of theatre school, I was sleeping on the living room floor of my cousin's apartment in Toronto, trying to figure out what to do with my life. My cousin had been an actor before he became a quadriplegic in a car accident, and as I unadvisedly bemoaned my unemployment status, he said something like, "Seriously? You're complaining about your life? Don't make me burst a colostomy bag." He was right, of course. I wasn't in a wheelchair, though I did have a stepmother who had rendered me homeless because of her dislike for me. She was always saying things like, "Your hair can't be as ugly as that hat you're wearing." Or simply refusing to invite me to things like Christmas dinner. I always admired people with families. My boyfriend at the time was one of five kids who were always doing things together. Their house was always full of noise and activities. Even as a shiksa, I felt more at home there than with my stepbrothers and sisters, who never lost an opportunity to point out that I was weird. I wanted to stand up to them, but not wanting to cause my father any grief, I held my tongue and sought refuge elsewhere. It occurred to me that perhaps I was using the theatre as an opportunity to say things through characters that I couldn't find the courage to express myself.

The Toronto Star was still open on the kitchen table, and I rummage through the Want Ads, that dirty part of the newspaper near the back where complete strangers will soon become complete assholes in your life by forcing you to work menial jobs in humiliating uniforms for minimum wage.

"Find anything?" my cousin called from the bedroom, where two attendants helped wash and dress him.

"Social services are advertising for camp councilors to work with emotionally challenged kids."

"Oh yeah," He said. "That might suit you."

I'm not sure I knew what he meant but, I was beginning to think I'd outgrown my welcome. My cousin probably would have encouraged me to join the circus if the option had been available. Knowing my living room days were numbered, I thought it best to make an effort and apply.

I had no experience teaching drama—no experience working with kids and no experience going to or working at a camp. Despite all that, I was hired. It's worth noting that it's probably not a good sign if you get a job with no qualifications whatsoever.

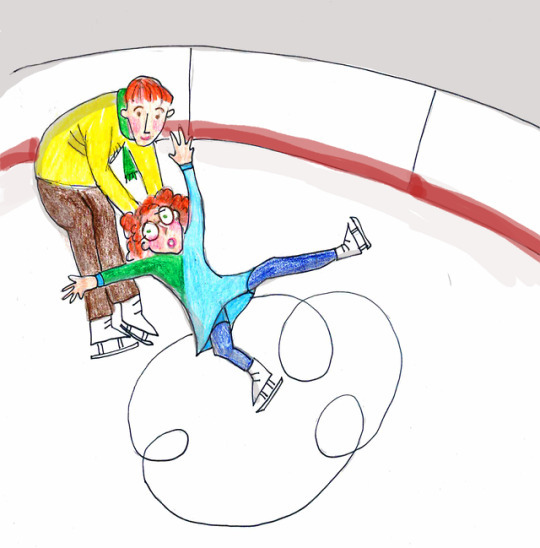

My official position was Drama Councillor, and I prided myself that with only a year and half of theatre training behind me, I was well equipped to help others benefit from the wealth of my experience. I imagined myself, Maria Von Trapp, teaching children how to sing while they looked at me adoringly. Somehow, I conveniently blocked out the rebellious early stages she experienced and skipped straight to the good parts. Also, I might add, forgetting about the Nazis and having to climb over a mountain. Still, visions of me biking around camp with a group of happy campers behind me filled me with a sense of self-satisfaction.

As I packed my knapsack with deet and a secret stash of Twinkies, I thought of how only three weeks earlier I'd been in New York walking through Central Park and savoring Cappuccinos at outdoor cafés on Columbus. Now, here I was, ready for something different. The wilderness, I imagined, would be a welcome change—fresh air and loons instead of smog and sirens. I thought smugly about my classmates sweating behind visors at take-out windows shoveling fries into cardboard cups or wrapping sandwiches in tinfoil. Thumbs up to adventure, I told myself. The fact that I'd never once in my life enjoyed the great outdoors didn't factor into my mind. All of this changed with each accumulated minute of the 391 Kilometer drive north.

It was late afternoon when I arrived at the compound. Overcast, sullen, it was a place so secluded you'd need flares to find it. It had that distinct aura of someplace time forgot. A place left behind and neglected. In the brochure, the sun was shining, flowers filled the meadow, and you could practically hear laughter floating off the page. What I was looking at bore more of a resemblance to a situation in a Stephen King novel where camp councilors discover a pack of hungry teenage zombies have lured them to a seemingly idyllic retreat. Situated right in the heart of black fly country, I spent most of my days swatting insects so big they seem Jurassic.

During our orientation, child care workers warned us that children with mental health needs tend to run away - a lot and to keep strict attendance records and all eyes on them at all times. "These kids are resourceful and clever," they cautioned. I couldn't imagine being so determined you'd risk your life by escaping through the woods that surrounded us, but then again, I'd never been around children who weren't allowed cutlery before either

I shared my cabin with three other women with who I had absolutely nothing in common. Delia, a humorless 27-year-old cooking instructor who answered every question with a monosyllabic grunt, Jennifer, a 26-year old tennis instructor with massive blond ringlets who talked so quickly she sounded like a record on high speed, and an older aboriginal woman named Sunny who made us all dream catchers and offered advice about how to heal ourselves on days when we'd feel spent. "Remember, these kids need us," she said while purifying our cabin with sage. As I glanced around my assigned bunk, taking in the spider webs and loose floorboards, I had that sinking feeling that comes when you know you've made a terrible mistake. Before long, I was eating copious amounts of peanut butter on stale bagels amid a never-ending supply of starch. I'm not sure who thought it was a good idea to feed children with challenges like anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and eating disorders copious amounts of sugar and carbs. It certainly did nothing to help them or me.

On the first day of class, I sat everyone in a circle. "Welcome to drama class," I said with a smile. "Let's begin by sharing with everyone a little bit about ourselves. Anything at all you'd like us to know?" A hand went up.

"I'm Tracy, and I hate my stupid ass brother. He can go straight to hell."

"Okay," I said, "That's a start. Who's next?"

Another hand. "I'm Jonathan, and this place sucks so much I wish it would burn to the ground!"

"Fair enough. Anyone else?"

"I'm Jo. I'm schizophrenic. So sometimes I'm Rachel and Julia. You'll know the difference because Rachel has a British dialect, and Julia talks slang."

"O-kay." I glanced at the social workers who sat on the edge of the room and looked at me with an expression that basically said, "We can't wait to see what you do next."

"Let's write a play," I suggested. "Write anything you want. Once you're happy with the work, I'll shape it into a cohesive piece that we'll rehearse and then present at the end of the season talent showcase."

The kids liked this idea. The showcase was a big deal. It was an opportunity for them to blow off some steam and express themselves to friends and family in a creative way. My only stipulation was not to use profanity. As the weeks passed, I was impressed with how well they all threw themselves into this project—all except Eric, the oldest boy in my 12 to 15-year-olds. Eric often wandered around the rehearsal space, unfocused and sullen.

"Any ideas for your piece?" I ask, checking in to see if I could help.

"I'm thinking," he'd say and then pace.

With three weeks left in the summer, I took my well-deserved week off to decompress. My boyfriend came up from Toronto and drove me to his parent's house at Post and Bayview, where caterers were preparing the tennis courts for an outdoor party. I walked into his mother's living room, and she gasped. "What happened to you?"

I didn't blame her. I hadn't spent much time looking at a mirror the past four weeks, but one glance at the large one in their bathroom told the full story. My hair was ratty; I had scabs on my knees, bruises on my arms and legs, and I was sunburnt. I was wearing a vintage skirt and blouse that was probably more Value Village than vintage and a pair of worn, scuffed purple moccasins; in essence, I was wearing slippers on my feet.

"Please take her to the mall and at least buy her a pair of shoes," his mother said, handing me her credit card and then rushing off to make sure the stuffed alligator would float in the pool. That week I ate my way through rugelach, hamantaschen, brisket, and bagels while his family watched me with awe and disgust.

Back at camp, the smell of burning insect repellent greeted me along with the news that the sailing and tennis instructors were sacked for disorderly conduct. Never mind, I had renewed energy and a sense of purpose. There were costumes and props to make. Sound and lighting effects to create. And we needed to rehearse. It was only a tiny stage somewhere on a remote camp in Northern Ontario, but the excitement was palpable. I was excited. This would be the best talent show ever, and my kids were going to blow the socks off everyone there!!!

"Eric," I said, "How's your piece coming along?"

"I finished it," he mentioned casually

"That's great. Can I see it?"

"I want to surprise you. You're going to love it, though. I promise."

I patted myself on the back. Eric had a breakthrough. All my encouragement and patience had paid off. Perhaps I'd helped him have a developmental breakthrough.

"Can you tell me what it's about?" I asked.

"The Beatles."

"Great. Okay," and left it at that.

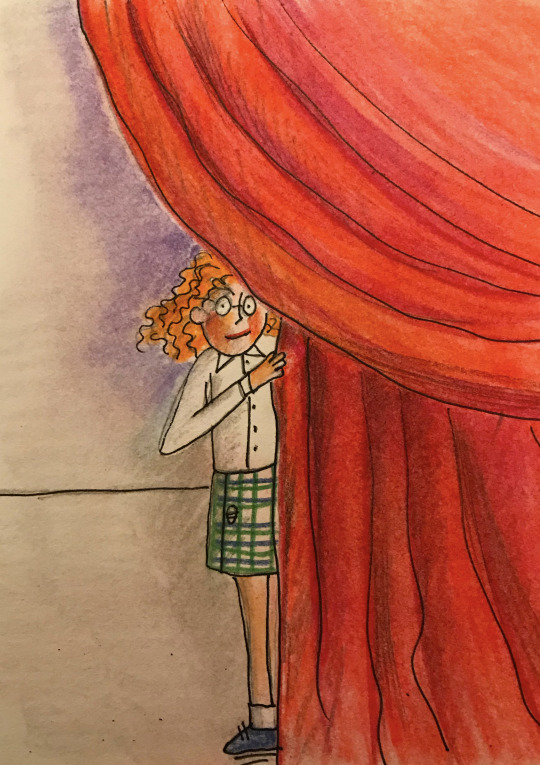

Talent Night arrived along with parents and family friends. The lights dimmed, the kids performed, and the audience enthusiastically applauded as each "Mighty Mite" or "Spirit of Paradise" breezed across the stage, acting out skits about fairies and monsters and assorted escapades. Finally, it was Eric's turn. Out he came, looking serious and theatrical. He cleared his throat and addressed the audience.

"This is called, The Beatles Last Recording Session. By, Me."

Three of his closest camp friends filed out and took a space on the stage. The audience was silent.

There was a dramatic pause, then the piece began.

"Fuck you, Ringo,"

"Fuck you, Paul."

"Fuck you, George."

"Well fuck you, John."

Then they bowed and left the stage.

Personally, I thought it was kind of brilliant. Needless to say, I wasn't showered with accolades about my teaching methods or the effect I had on kids. I left there having no catharsis about mental health except that giving people the opportunity to express themselves without censor is probably a lot healthier than insisting they stay quiet. I admired the honesty displayed in the kid's work. If only, I thought to myself, I could be half as brave. Wasn't that what I was spending time and money learning how to do?

A week after being home, I found myself packing, once more, for school in New York. Our term letters had arrived with instructions on where to buy character shoes, leotards, copies of The Children's Hour, and Death of a Salesman. The camp already felt like it was 391 kilometers away - soon to be 659. My father drove me to the train station with my stepmother beside him; she was there, no doubt, to ensure I boarded.

"You going to be okay?" my father asked, giving me a hug and slipping a $50 bill into my pocket.

"She'll be fine." Elsie chimed in. "You don't have to worry about her. Let's go."

But I wanted my father to worry about me. Not all the time and to the exclusion of all else, but certainly the appropriate fatherly amount.

As I settled myself on the train, I watched my stepmother pull from father from the platform to the car and thought of Eric's brilliant play. Under my breath, I whispered the immortal words of the Beatles, "Fuck you."

#stepmother #mental health #children #young people #summer camp

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Breath of Fresh Air

The summer after my first year of theatre school, I was sleeping on the living room floor of my cousin's apartment in Toronto, trying to figure out what to do with my life. My cousin had been an actor before he became a quadriplegic in a car accident, and as I unadvisedly bemoaned my unemployment status, he said something like, "Seriously? You're complaining about your life? Don't make me burst a colostomy bag." He was right, of course. I wasn't in a wheelchair, though I did have a stepmother who had rendered me homeless because of her dislike for me. She was always saying things like, "Your hair can't be as ugly as that hat you're wearing." Or simply refusing to invite me to things like Christmas dinner. I always admired people with families. My boyfriend at the time was one of five kids who were always doing things together. Their house was always full of noise and activities. Even as a shiksa, I felt more at home there than with my stepbrothers and sisters, who never lost an opportunity to point out that I was weird. I wanted to stand up to them, but not wanting to cause my father any grief, I held my tongue and sought refuge elsewhere. It occurred to me that perhaps I was using the theatre as an opportunity to say things through characters that I couldn't find the courage to express myself.

The Toronto Star was still open on the kitchen table, and I rummage through the Want Ads, that dirty part of the newspaper near the back where complete strangers will soon become complete assholes in your life by forcing you to work menial jobs in humiliating uniforms for minimum wage.

"Find anything?" my cousin called from the bedroom, where two attendants helped wash and dress him.

"Social services are advertising for camp councilors to work with emotionally challenged kids."

"Oh yeah," He said. "That might suit you."

I'm not sure I knew what he meant but, I was beginning to think I'd outgrown my welcome. My cousin probably would have encouraged me to join the circus if the option had been available. Knowing my living room days were numbered, I thought it best to make an effort and apply.

I had no experience teaching drama—no experience working with kids and no experience going to or working at a camp. Despite all that, I was hired. It's worth noting that it's probably not a good sign if you get a job with no qualifications whatsoever.

My official position was Drama Councillor, and I prided myself that with only a year and half of theatre training behind me, I was well equipped to help others benefit from the wealth of my experience. I imagined myself, Maria Von Trapp, teaching children how to sing while they looked at me adoringly. Somehow, I conveniently blocked out the rebellious early stages she experienced and skipped straight to the good parts. Also, I might add, forgetting about the Nazis and having to climb over a mountain. Still, visions of me biking around camp with a group of happy campers behind me filled me with a sense of self-satisfaction.

As I packed my knapsack with deet and a secret stash of Twinkies, I thought of how only three weeks earlier I'd been in New York walking through Central Park and savoring Cappuccinos at outdoor cafés on Columbus. Now, here I was, ready for something different. The wilderness, I imagined, would be a welcome change—fresh air and loons instead of smog and sirens. I thought smugly about my classmates sweating behind visors at take-out windows shoveling fries into cardboard cups or wrapping sandwiches in tinfoil. Thumbs up to adventure, I told myself. The fact that I'd never once in my life enjoyed the great outdoors didn't factor into my mind. All of this changed with each accumulated minute of the 391 Kilometer drive north.

It was late afternoon when I arrived at the compound. Overcast, sullen, it was a place so secluded you'd need flares to find it. It had that distinct aura of someplace time forgot. A place left behind and neglected. In the brochure, the sun was shining, flowers filled the meadow, and you could practically hear laughter floating off the page. What I was looking at bore more of a resemblance to a situation in a Stephen King novel where camp councilors discover a pack of hungry teenage zombies have lured them to a seemingly idyllic retreat. Situated right in the heart of black fly country, I spent most of my days swatting insects so big they seem Jurassic.

During our orientation, child care workers warned us that children with mental health needs tend to run away - a lot and to keep strict attendance records and all eyes on them at all times. "These kids are resourceful and clever," they cautioned. I couldn't imagine being so determined you'd risk your life by escaping through the woods that surrounded us, but then again, I'd never been around children who weren't allowed cutlery before either

I shared my cabin with three other women with who I had absolutely nothing in common. Delia, a humorless 27-year-old cooking instructor who answered every question with a monosyllabic grunt, Jennifer, a 26-year old tennis instructor with massive blond ringlets who talked so quickly she sounded like a record on high speed, and an older aboriginal woman named Sunny who made us all dream catchers and offered advice about how to heal ourselves on days when we'd feel spent. "Remember, these kids need us," she said while purifying our cabin with sage. As I glanced around my assigned bunk, taking in the spider webs and loose floorboards, I had that sinking feeling that comes when you know you've made a terrible mistake. Before long, I was eating copious amounts of peanut butter on stale bagels amid a never-ending supply of starch. I'm not sure who thought it was a good idea to feed children with challenges like anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and eating disorders copious amounts of sugar and carbs. It certainly did nothing to help them or me.

On the first day of class, I sat everyone in a circle. "Welcome to drama class," I said with a smile. "Let's begin by sharing with everyone a little bit about ourselves. Anything at all you'd like us to know?" A hand went up.

"I'm Tracy, and I hate my stupid ass brother. He can go straight to hell."

"Okay," I said, "That's a start. Who's next?"

Another hand. "I'm Jonathan, and this place sucks so much I wish it would burn to the ground!"

"Fair enough. Anyone else?"

"I'm Jo. I'm schizophrenic. So sometimes I'm Rachel and Julia. You'll know the difference because Rachel has a British dialect, and Julia talks slang."

"O-kay." I glanced at the social workers who sat on the edge of the room and looked at me with an expression that basically said, "We can't wait to see what you do next."

"Let's write a play," I suggested. "Write anything you want. Once you're happy with the work, I'll shape it into a cohesive piece that we'll rehearse and then present at the end of the season talent showcase."

The kids liked this idea. The showcase was a big deal. It was an opportunity for them to blow off some steam and express themselves to friends and family in a creative way. My only stipulation was not to use profanity. As the weeks passed, I was impressed with how well they all threw themselves into this project—all except Eric, the oldest boy in my 12 to 15-year-olds. Eric often wandered around the rehearsal space, unfocused and sullen.

"Any ideas for your piece?" I ask, checking in to see if I could help.

"I'm thinking," he'd say and then pace.

With three weeks left in the summer, I took my well-deserved week off to decompress. My boyfriend came up from Toronto and drove me to his parent's house at Post and Bayview, where caterers were preparing the tennis courts for an outdoor party. I walked into his mother's living room, and she gasped. "What happened to you?"

I didn't blame her. I hadn't spent much time looking at a mirror the past four weeks, but one glance at the large one in their bathroom told the full story. My hair was ratty; I had scabs on my knees, bruises on my arms and legs, and I was sunburnt. I was wearing a vintage skirt and blouse that was probably more Value Village than vintage and a pair of worn, scuffed purple moccasins; in essence, I was wearing slippers on my feet.

"Please take her to the mall and at least buy her a pair of shoes," his mother said, handing me her credit card and then rushing off to make sure the stuffed alligator would float in the pool. That week I ate my way through rugelach, hamantaschen, brisket, and bagels while his family watched me with awe and disgust.

Back at camp, the smell of burning insect repellent greeted me along with the news that the sailing and tennis instructors were sacked for disorderly conduct. Never mind, I had renewed energy and a sense of purpose. There were costumes and props to make. Sound and lighting effects to create. And we needed to rehearse. It was only a tiny stage somewhere on a remote camp in Northern Ontario, but the excitement was palpable. I was excited. This would be the best talent show ever, and my kids were going to blow the socks off everyone there!!!

"Eric," I said, "How's your piece coming along?"

"I finished it," he mentioned casually

"That's great. Can I see it?"

"I want to surprise you. You're going to love it, though. I promise."

I patted myself on the back. Eric had a breakthrough. All my encouragement and patience had paid off. Perhaps I'd helped him have a developmental breakthrough.

"Can you tell me what it's about?" I asked.

"The Beatles."

"Great. Okay," and left it at that.

Talent Night arrived along with parents and family friends. The lights dimmed, the kids performed, and the audience enthusiastically applauded as each "Mighty Mite" or "Spirit of Paradise" breezed across the stage, acting out skits about fairies and monsters and assorted escapades. Finally, it was Eric's turn. Out he came, looking serious and theatrical. He cleared his throat and addressed the audience.

"This is called, The Beatles Last Recording Session. By, Me."

Three of his closest camp friends filed out and took a space on the stage. The audience was silent.

There was a dramatic pause, then the piece began.

"Fuck you, Ringo,"

"Fuck you, Paul."

"Fuck you, George."

"Well fuck you, John."

Then they bowed and left the stage.

Personally, I thought it was kind of brilliant. Needless to say, I wasn't showered with accolades about my teaching methods or the effect I had on kids. I left there having no catharsis about mental health except that giving people the opportunity to express themselves without censor is probably a lot healthier than insisting they stay quiet. I admired the honesty displayed in the kid's work. If only, I thought to myself, I could be half as brave. Wasn't that what I was spending time and money learning how to do?

A week after being home, I found myself packing, once more, for school in New York. Our term letters had arrived with instructions on where to buy character shoes, leotards, copies of The Children's Hour, and Death of a Salesman. The camp already felt like it was 391 kilometers away - soon to be 659. My father drove me to the train station with my stepmother beside him; she was there, no doubt, to ensure I boarded.

"You going to be okay?" my father asked, giving me a hug and slipping a $50 bill into my pocket.

"She'll be fine." Elsie chimed in. "You don't have to worry about her. Let's go."

But I wanted my father to worry about me. Not all the time and to the exclusion of all else, but certainly the appropriate fatherly amount.

As I settled myself on the train, I watched my stepmother pull from father from the platform to the car and thought of Eric's brilliant play. Under my breath, I whispered the immortal words of the Beatles, "Fuck you."

#stepmother #mental health #children #young people #summer camp

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Faith, Hope & Charity

At Vatican City, I overheard two American tourists with distinctly southern dialects discussing the beggars asking tourists for change.

“You’d think they would do something about it,” the man said to the woman, who nodded in agreement while admiring her recently purchased crucifix.

Visitors waiting for their designated museum times can sit in the square or stroll through any one of a dozen souvenir shops that sell religious artifacts for exorbitant amounts of money. Things that generally sell on Kijiji or Amazon for next to nothing are priced three or four times higher in the square. And these tourists beside me had opted to give their money to thieves in suites rather than beggars in rags. Interesting. I have to assume they were religious; hence, why the crucifix? True, it could have been a gift for someone else, but even so, it seemed so biblical, me sitting at the Vatican beside two reasonably well-dressed people who were loudly condemning the poor.

I’m not against people with a belief. I’ve known some incredibly kind Christians and some indecent ones too. I’ve dated Jews, Greek Orthodox, Coptics, atheists, and agnostics. Sometimes I meet people who tell me they’re spiritual, and I take that to mean that they believe in a higher power but not an organized religion. The thing about organized religion is how desperate they are to recruit you. I’ve made the mistake a few times of accompanying a friend or boyfriend to their church or temple of choice only to be cross-examined at “friendship hour” afterwards.

“Don’t forget to sign the registry” “Be sure to leave your e-mail?” “How did you like the service?” “

I’m always so tempted to say, “I didn’t like the service at all. I thought the little speech in the middle was boring as hell. In the theatre, you’d never be able to get away with so little effort.” In fact, during a few of those boring lectures, I’ve actually wondered what it would be like to review them. Can a person be a homily critic?

Last Sunday at St. Thomas Episcopalian, Reverend Porter spoke on the story of the Good Samaritan in what can only be described as a futile effort to instill any empathy whatsoever. His monotone delivery showed no sign of excitement or interest in the very subject of which he spoke, and his overuse of gesticulation could be better served as choirmaster. I highly recommend any churchgoer avoid this Liturgical season until Easter, when things will hopefully become a bit livelier.

I’ve often made the mistake of expecting more from those who claim to believe. After all, the general consensus (and I don’t think I’m going out on a limb here) is that someone who follows the word of God is most likely going to practice kindness, love, compassion, forgiveness, and understanding. It’s like a person who boasts of being a great chef and then serves you store-bought pasta with a lumpy Béchamel. “I don’t wish to offend,” you might say, “But do you really expect me to swallow this crap?” If Catholic school taught me anything, it was how rarely one saw the word of God put into practice. Not that everyone was mean, but the “Do unto others…” doctrine wasn’t generously applied. Sadly, more often than not, I’ve often been disappointed by those who claim to be followers of Christ. I think, if Jesus were around today, He’d be disappointed too. Sometimes I imagine Christ with a Twitter account and millions of followers towards whom He’d constantly have to correct in a never-ending stream of tweets like:

“I cannot be held responsible for everything the prophets said,” or “I didn’t even know Leviticus.”

People who have no religious beliefs whatsoever can also be surprisingly horrible. I’m always slightly taken aback when they denounce religion taking the stance that this makes them somehow better than everyone else. I’m easily tricked into thinking they are, then let down when they behave just as badly. These are the people who fight for climate control while driving an SUV. They’re firmly against bullying, then bully you when you disagree with them. I kind of subscribe to the whole: Let he without sin cast the first stone. As advice goes, it’s pretty good.

My belief system runs somewhere between Spiritual Deism with a side of Christianity and a strong desire to be Jewish. My Jewish boyfriend for seven years reminded me of what it meant to be part of a family, something I always wanted. I looked forward to Friday Shabbat dinners where we’d gather over brisket and discuss important issues like the colour of the car Bernie was going to buy.

“It’s red.” He’d nonchalantly say while savouring the dinner.

“Red?” his Mother would announce. Fork down, dinner halted. “You’re not a red car sort of guy.”

“What does that mean?” Bernie would ask, oblivious to where this was going.

“You’re a blue car or a gold car-- not red. You’re brother here; he’s a red car driver. Mr. Flashy. Mr. Look-at-Me. But you…you’re definitely not red.”

“I can be flashy!”

“Never!”

“Sure, I can.”

“Not going to happen.”

“There are plenty of times when I’ve been flashy.”

“Name one?”

“Aunt Zelda’s birthday party?”

“Aunt Zelda’s birthday party? What are you talking about?”

“I did that impersonation of Lenny Bruce.”

“Oy vey. Shut up and eat your brisket. And tomorrow, change the colour of your car.”

My first husband’s father, Ezzat, was completely the opposite. A proud Egyptian, he’d grill me over dinner with questions like, “Do I or do I not ALWAYS ask you about your father?” to which I’d cautiously reply, “Well…I wouldn’t say always.” The next thing I knew, I was being called a liar, and he’d refuse to cross the threshold of my home. Once, while I was still suffering from dry sockets after having my wisdom teeth removed, he blended lamb, lentils and carrots together in what can only be described as vomit. It was a lovely gesture, but he was deeply offended when I couldn’t drink/eat it. I offended him a lot. Looking back on old journals, it strikes me now that no fiancé in the history of the world was more disliked. At night I’d pray, “Dear God, what have I done to make everyone hate me?” And all I heard back was, “Who’s everyone?”

Christian or not, it isn’t easy being a good person. When people run a stop sign, then give me the finger when I honk, I’m apoplectic, ruminating all day on what an asshole they are. If someone cheats me or slights me or makes me the subject of a lie, I brood and stew, giving away too much power to those who wish to hurt me. I aspire to be most like my father, who was always kind and courteous. Walking down the street in his later years, he would say hello to everyone and mean it. He was genuinely interested in people. I was grateful that he didn’t seem to notice women blanch when he called them “dear” or, after exchanging pleasantries, would leave someone with a “God bless you.” As his dementia grew worse, he appeared to become more and more beatific. Whether playing monopoly or eating a sandwich, he relished every moment accepting his fate with grace. As I sat beside his hospital bed and watched him pass from this world to the next, I believed he was embraced by something.

I think about my friends who have been oppressed yet still find the ability to forgive, celebrating at Baptist churches with a kind of joy I rarely see anywhere. I have learned a lot from my Black friends, and colleagues about what it means to be, if not Christian, then Christian like. I’m humbled by the love I’ve received when I probably didn’t deserve it.

Hollywood would have you believe that Christians are either assholes or saints, and regardless of which category you fall into, you’ll suffer in the end. The assholes are hoisted on their own petard, and the saints are martyred. I have a famous writer friend in L.A. who once said to me, “It was easier to come out as gay than Christian in Los Angeles.”

When I was seven, I saw the movie Song of Bernadette based on the true story of a young girl visited by the Virgin Mary. As a result of her miraculous visitations, Bernadette is rewarded with tuberculosis of the bone, suffers terrible pain and eventually dies—all while being persecuted by a nun who is jealous of her visions. At seven, I put two and two together. If that’s what happens to you when you’re humble and devout, then count me out. The last thing I wanted was for God or Mary or Angels to appear before me. And it wasn’t just Bernadette. Saint Afra, Saint Aggripina, Saint Basilissa, Saint Cecilia, Saint Dymphna, Saint Eurosia, Saint Susanna, Saint Juthwara, Saint Noyala, and Saint Winifred were all decapitated for their faith. To make matters worse, Faith was my middle name. What was my Mother thinking when she saddled me with a Christian moniker? From what I could tell, since the basis of sainthood appeared to be suffering under horrible circumstances, I was eager to abandon the idea of being good altogether. As long as I had a little larceny in me, I could stave off being burned at the stake or decapitated. When misbehaving, my Mother would ask, “Why are you so bad?” And I would answer, “So I don’t become a saint.” I could see no situation in which becoming pious was worth it.

Back in the Vatican museum, I stood beneath the Sistine Chapel ceiling with hordes of other tourists feeling a bit like I was in purgatory waiting for judgment. Guards constantly chastised us to be quiet as we craned our necks to catch a glimpse of God. “There’s so much nudity,” I heard someone say, “God doesn’t look like that.” I was tempted to say, “It’s not a photograph. It’s an interpretation.” But I wisely kept my mouth shut. As I stared at the Delphic Sibyl, I remembered the legend: …born between man and goddess, daughter of sea monsters and an immortal nymph; she became a wandering voice that brought to the ears of men tidings of the future wrapped in dark riddles. It sounds like Sibyl might be pretty busy these days. Finally herded outside, most of the people around me had already put Michelangelo’s frescos out of mind. It was just one more thing to cross off their bucket list. Instead, their attention was now on the line-up at the Vatican pizzeria where for 10 Euros you could have a slice with cheese. 2 more Euros, and you could have water add an extra Euro and you could have it blessed.

As my time to visit St. Peter’s Basilica drew near, I lined up like a good little pilgrim to enter the “Holy Door” and passed into the atrium. I didn’t feel the presence of God there, just tourists who couldn’t resist a good selfie in front of the Pieta. Michelangelo’s sculpture masterpiece conveys the sorrow of the Virgin Mary, her right hand clutching her dead son while her left-hand falls limp at her side, resigned. I was contemplating the gesture when the woman beside me asked her friend,

“What do you suppose it means?”.

“Maybe she dropped her cellphone,” her companion quipped, and they laughed. It echoed shrilly through the chamber like hyenas. I sometimes feel the same way about women as I do about Christians. I expect them to be better and disappointed when they aren’t. I’m sure they feel the same way about me.

0 notes

Text

A Christmas Story

A few Christmases ago, when in Paris, I happened to become friends with a homeless gentleman who frequented the corner at the end of my street. He sat upon a shocking pink suitcase with his little dog, Lucky, curled up at his feet and wished everyone who passed by a heartfelt “bonne journée.”

He never asked for money. Not once. He never scorned those who scoffed or worse judged. He simply smiled and greeted every passerby with a sincere greeting of goodwill. I’d been warned repeatedly about beggars in Paris. “Charlatans,” people said, “they’ll take everything you own if you let them.” So, when I first encountered Nichola, I hurried by shunning eye contact and willing myself NOT to look at the dog. I can turn a blind eye like the rest of us to things too uncomfortable to deal with and reasoned that since this was my first visit to Europe, I deserved a break from routine considerations. But no matter how much I wished I could ignore them, they were always there, as constant as the Eiffel Tower. After a few days, it became impossible, and frankly tiresome, avoiding him. I began to observe how kind he seemed. Children, in particular, loved Lucky and were always feeding him from the small market at the corner. On the fourth night of my stay, I happened to be returning from a concert at the Chapel in Versailles. Intoxicated by the music of Faure, I was in a particularly good mood when I noticed Nichola and Lucky asleep on the street. It was cold that night and a light wet snow had fallen so they were huddled on a grate for warmth upon the wet pavement. My heart cracked. I made my way to the apartment I was staying in around the corner on Duvivier and laying on my bed, stared at the ceiling unable to sleep. I had no idea how I could help or what comfort I could offer, but pretending they didn’t exist was now impossible.

If you learn one thing in Paris it’s about man’s inhumanity to man. Art galleries, of which there are a plethora, boast painting after painting of retribution, judgment, mercy, benevolence, and grace. Who knows more about these things than artists? The lesson from nearly every painting is how downtrodden the poor are, how much God loves the unfortunate, and the cautionary tale of revolt. No matter where I went, or what I saw, it was always Nichola and the dog. Van Gogh stared at me from his self-portrait and whispered, “What are you going to do about Nichola and the dog?” The Raft of Medusa by Théodore Géricault became a depiction of the homeless people piled on a barge with nowhere to go. Gustave Courbet’s self-portrait with a dog was none other than Nichola himself with Lucky tucked into his side. And no, it wasn’t lost on me that Nichola (namesake of Christmas) was sleeping on St. Dominque street. Dominique - the patron saint of astronomers; a man who selected the worst accommodations and the meanest clothes, and never allowed himself the luxury of a bed. What was the universe trying to tell me?

The following morning, I had breakfast with Nichola and Lucky. I brought croissants, dog food, and coffee, and for an hour I sat cross-legged on the sidewalk as we made our first attempt to converse. My French is, très mauvais, which didn’t matter as I soon discovered that Nichola's native tongue was Romani. With the help of a translation app, I learned that Romania and Bulgaria, where the majority of Roma originate, became full members of the European Union in 2007. But “transitional arrangements” in their accession to the EU mean that citizens of these former communist bloc states did not enjoy complete freedom of employment in France until December 31, 2013. Even now only certain Roma are able to be hired for certain work. He showed me a photograph of his daughter in Czechoslovakia and he gleaned that I was in theatre visiting Paris on a bursary I’d won from the Stratford Festival. Breakfast over, I waved goodbye and headed to D’Orsay or Versailles, or the Louvre, but I always came back to Nichola and Lucky for dinner between 5:30 – 6:00. On nights when the weather was bad, I gave him money for a shelter or would return home to find that he’d already earned enough for a bed somewhere. Those nights I slept better than others. Nights when I knew he wasn’t on the street, I imagined (probably somewhat naively) that he and the dog were at least safe.

It occurred to me that it was possible I was being bamboozled. It’s conceivable that my friend had a stash of money somewhere, coaxed from emotional tourists like me. Truth be told, nothing would have pleased me more than to find out that Nichola had a fine apartment in a good arrondissement and dined well with Lucky curled up on Egyptian cotton sheets. If I was being fleeced then so be it. Anyone who begs deserves money, as far as I’m concerned. It’s not a noble profession. It’s not gratifying. It’s demoralizing, tedious, work brought to light even more so during the holiday season.

What is it about Christmas that always brings us back to the issue of money? We spend so much on the creature comforts of the season, investing in commercialism and forgetting that the whole Christmas story revolves around a couple about to give birth with no roof over their head. And how often do we watch A Christmas Carol forever reminded that Ebenezer Scrooge’s relationship with money makes him as hollow as the apartments he keeps: void of life and colour. The first time I saw A Christmas Carol I was terrified. (I’m referring in particular to the black and white Alistair Sim version) Marley’s ghost in particular haunted, not only Scrooge but me for days afterward. I half expected to see the shimmering outline of some long lost relative at the end of my bed reprimanding me for stealing cookies or stepping on flowers. In my childlike brain, Marley and Santa Claus merged into some kind of specter sent to judge whether I’d been good, or not. I was forever trying to figure out how good was good? How bad was bad? If found wanting, would I be sentenced to walk the earth with the chains I’d forged? Even as a child I imagined the cord was extensive. I marveled at Charles Dicken's imagination. I didn’t believe Ebenezer Scrooge was real. No one, I reasoned, was that stingy or that greedy; but over time I’ve met a lot of Scrooges and I’ll bet you have too. We use money to ascertain a person’s value and to hold sway over others. It’s the most mysterious entity because it’s only valuable if we think it is. I learned this lesson long ago when studying in New York. I happened to hand a Canadian quarter to a subway attendant who shoved it back at me saying, “I can’t take your funny money.” Perfectly good in one place and absolutely worthless somewhere else.

It’s embarrassing asking for money when you need it and difficult for people being asked. I know a lot about this awkward relationship with money. My father, for a time, was a bank manager and finances were something we simply did not discuss. Not ever. To borrow, even a few hundred dollars was unheard of. Worse, in my family, you were shamed for asking. And if anyone took pity on you with a few bucks here or there, it was always accompanied with the directive, “…don’t tell your mother, or brother, or step-mother.” It was even worse being in the arts, a profession that carried with it the stigma of irresponsibility. The only exception I knew of was my Nana on my Mother’s side who loved nothing more than to give people things. I inherited this one trait from her. Money has never been something I hoarded (probably to my demise). Instead, I’ve seen it as simply an opportunity to help. In Paris, I became the newly converted Ebenezer Scrooge. Instead of eating at the most expensive restaurant, I ate at moderately fine establishments and saved the difference for Nichola. I bought day-old croissants and gave the difference I saved to Nichola. And when my departure date drew near I bought him a care package of food, blankets, socks, dog food, and treats.

My last night in Paris, I met a friend for a quick coffee and found myself getting emotional as I talked about the street beggars. Could it be that in getting to know Nichola, I realized that so much of my life was about luck? I live in a town where it’s not unheard of for people to have more than one home, and there was a perfectly nice person living on the streets. Our lives are so vastly different, our circumstances so varied simply for the fact of our birth. There but for the grace of God…

When my friend and I parted I made my way in the dark to Notre Dame and listened to a Christmas concert in an overflowing cathedral filled to the brim with parents and children all there to sing Sante Maria and Joy to the World. How fortunate for me that I was able to experience Notre Dame before the fire. Even an atheist would be hard-pressed to admit that there wasn’t something spiritual about that cathedral. And sitting there amongst the Parisians I felt a kind of peace. “What will happen to Nichola?” I asked the rafters and what came back was the sound of children singing:

Angels we have heard on high

Sweetly singing o'er the plains

And the mountains in reply

Echoing their joyous strains

Gloria, in Excelsis Deo

Gloria, in excelsis Deo

As I was walked home after the concert I happened by the famous bookstore: Shakespeare & Co. and was stopped in my tracks by the store’s motto, "Be Not Inhospitable to Strangers Lest They Be Angels in Disguise."

That night I wrote a letter to Nichola and left him enough money for him and his dog to return to his daughter. I sealed the envelope and, in the morning, before I left for the airport, I gave it to him.

I mention this, dear reader, not to draw any attention on me whatsoever. It’s our job to help our fellow man…at least Charles Dickens thought so when he penned,

“At this festive time of the year… it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at present. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts.”

Three months later, I received a letter from Czechoslovakia. Enclosed was a thank you and photos of Lucky, Nichola, and his daughter in the backyard of a home set against the hills.

If I can help someone, then so can you.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being Seen

I was sitting in a movie theatre waiting to see Inception or Perception or Deception, some movie with a title that sounded similar when a woman entered my isle and then abruptly stopped right in front of me as I stood up to let her pass - like literally in front of me to have a conversation with someone she recognized two rows ahead. It wasn’t one of those quick exchanges like, “Oh, hi Joan. We missed you last week at line dancing.” It was a full-blown conversation that started something like, “Hey, Joan! Over here!! What’s up? Do you have wedding jitters yet? I remember when I got married…”

Being invisible is not new to me. I’ve been invisible pretty much my whole life, first, as a girl, then as a short teenager, and finally as a petit woman. I’ve noticed that no matter what I do – fancy outfits, crazy jewellery, changes to my hair, no one notices. Or if they do, they certainly never comment. At this point, I don’t even see the use in paying for plastic surgery as it wouldn’t likely produce anything more than, “Did you get new glasses?”

In this particular instance, after flattening myself to the cinema chair for what seemed like a good four minutes, I finally said, “Excuse me, but could you please move over so I can sit down.” Granted, my tone may have been less than polite, but I don’t think it warranted her “Get over yourself” response.

Once, at a play, an artistic director and his wife sat directly in front of me. When they turned around (as invariably people in the entertainment industry usually do) to see who they might recognize in the audience, I waved, and they didn’t notice me. I looked them directly in the eyes and …nothing. They could not see the tree for the forest. I had to leave at intermission because I thought if they eventually DID notice me, it would just be too embarrassing to explain that I’d been behind them all the time.

At a prestigious event for the theatre industry, a woman from Theatre Ontario shoved me out of the way to talk to someone. No kidding. She swiped me clear off the map with a dramatic swooping motion and left me in the dust. My husband, who was with me at the time, couldn’t believe his eyes.

I frequently find myself talking about something to a group of people only to suddenly discover the circle has closed and I’m monologuing in a corner. I’ve even been at a dinner party when someone quoted me and didn’t even remember.

Being invisible is not the best characteristic for an actress in a profession where being noticed is a prerequisite. I once auditioned for someone who said afterwards, “Where have you been hiding?” I had auditioned for that same director and that same panel five times before. Still, you notice a lot when you are invisible, like how some people need adoration while others need validation. Who is having an affair with whom? Who is jealous? Who is hurt? Who is desperate? Who is stealing the cutlery? Eventually, it all finds its way into a play…or a blog.

In our family, my brother was the only boy. Between my mother’s sister and her brother, there were five girls, and I made six. My brother was special simply by virtue of his sex. I was a dime a dozen. A video at the time shows me trying desperately to get attention by throwing myself into a hammock only to be shoved out by everyone, including my brother. The final shot is all four of them swinging merrily, having the time of their life while I sit alone at a picnic table. My cousins didn’t even like me. Whenever they would visit, they’d take out my toys and play without asking permission or even inviting me to join them. Once, they told me they weren’t supposed to play with me because I was “…different natured than everyone else.” My cousins were, in truth, horrible children who stole my Christmas carolling money earmarked for charity, but that’s another story.

The thing about being invisible is that when someone eventually sees you, it feels like a miracle. The simple act of acknowledgement is not only proof that you exist, but depending on the person, it can be a real boost to one’s self-esteem. When on occasion, I’ve been offered work at prestigious theatre companies, my first response is usually shock. Not because I don’t think I’m deserving, but more often because I’ve been noticed. I know Sally Field was parodied for saying, “You like me. You really like me,” after her second Academy Award, but perhaps what she actually meant was, “You see me. You really see me.” And when Ruth Gordon finally won her first Oscar at the age of seventy-two, she said, “I can’t tell you how encouraging a thing like this is…” She’d been in the business for fifty years. What she was really saying was, “Gee, thanks for finally noticing.”

I’m not entirely blameless. For the most part, I grew up not wanting to be noticed and learned the fine art of camouflage early on. Left to my own devices, I would wander around whatever city I lived in, pretending to be an international spy by using toenail clippers as my state-of-the-art transponder. If anyone noticed, they certainly never commented. At school, I hid behind people in photos and made my way, Ninja-like through hallways and classrooms. The family dog, Lema, probably knew more about me than any of my friends. She would listen, without judgement, to anything I said and even showed some interest when there was food. The only time I was noticed was when I was playing someone else on stage. Only then did I feel comfortable coming out of my shell. But arguably, being noticed isn’t the same as being seen.

The summer before I left home to study at the Neighborhood Playhouse in NYC, I was performing in a show I had written with a group of actors about the history of Niagara Falls. We thought we were exceptional as we sang (often flat or sharp) our fifteen original songs on weekend evenings at Oaks park amphitheatre at the base of Clifton Hill. My solo number (and the first song I’d ever written) was about Annie Taylor, who in 1901 was the first person and only woman to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel and live. Ironically, Annie Taylor died in the poor house, barely recognized for her daredevil feat.

Early morning shadows tell me,

That it’s time to rise.

Step into my costume.

Put on my disguise.

Pause before the looking glass.

Is my mask on well?

So convincing in my role,

That nobody can tell,

Underneath a piece is missing,

Left upon the shelf.

Though I teach the children words

I can’t define myself.

Five verses later, it ends…

Later, when I’m rescued

Will they even try to see?

The reason I have done this

Is to set my spirit free?

Or will they choose to say,

When they are mentioning my name,

That what I did was foolish

And was, therefore, all in vain?

Right now, it doesn’t matter,

For my stunt has been the key.

I’ve unlocked all the doors.

At last, I’m who I’m meant to be.

I loved how dark and mysterious this song was. I thought singing it made me mysterious too, but did anyone notice?

“I think Neal likes you,” my friend Tom told me one weekend in August as we were striking the set. We had just finished singing our “Disaster Medley.” Behind us, an ambulance was attempting to rescue yet another “Great Gorge” suicide attempt, and the five or six members of our audience had abruptly left our performance to join a crowd of curious onlookers. It was a regular occurrence that we had grown cynically accustomed to.

“Who is Neal?” I asked.

“Neal,” Tom replied, “The musician visiting from Eastman. The guy over there.” And he pointed to a lean young man sitting in the shadows by the wall.

The summer had been lovely, and we had two weeks of shows left before it would all end; before we all parted for other towns and other people. The air was filled with the scent of moonflowers and nostalgia.

“He likes me?” I asked. “He doesn’t even know me.”

“Well, he likes your song,” Tom said, “The one about the woman who goes over the falls in a barrel. He thinks you have talent.”

“What would he know?” I smirked as we headed to the shores of Lake Erie with guitars and firewood.

That evening, Neal followed me about interested in what motivated my song, or just me. He may have different recollections of this event, but to my mind, he pretty much monopolized my time. I had no real interest in dating. I was about to go to the Big Apple, and a boyfriend was not in the plan. So, when he departed for Rochester the following day, I didn’t think much more about him.

“He left you a song,” Tom reported the following Monday.

“A song?”

“Yeah, he wanted you to hear this song he wrote. Can you come over?”

I grabbed my bike and headed to his house.

“I’m in a bit of a hurry,” I said, not meaning to be rude but fairly certain that I was about to hear something amateurish and sentimental.

Tom had been my best friend for several years. I trusted him with my life.

“Is this guy for real?” I asked as Tom opened the cover of his Piano. “Tell me now, is he weird?”

“Are you?” he countered, “Am I?”

Tom had a way of putting things.

In truth, I was shocked at how good the piece was. Confident and self-assured, it showed far more sophistication than anything I was doing at the time. This guy had talent, and more importantly, he thought I did as well. He noticed something in me. I was smitten. “If music be the food of love, play on!”

In the few short months that the relationship lasted (that portion of the relationship, because we are still friends to this day), I can’t remember anyone being more honest with me or more interested in me, with the exception of my husband. One particularly long phone call from Philadelphia to Niagara must have cost him a small fortune since we talked for nearly four hours. So, when Neal broke up with me the following Thanksgiving, I was crushed. I remember it was a rainy damp, cold weekend in New York. Instead of celebrating with my boyfriend and his family, I was sitting in my brownstone alone. I kept walking around the block, expecting him to be in front of my stoop when I returned. That was the year I discovered Haagan Dazs, thanks to my room-mates who had no choice on the holiday weekend but to leave me alone crying my eyes out.

“There is nothing that can’t be cured with ice cream,” Ron suggested as he packed the freezer with Butter Pecan. And for good measure, they left me with the cat who sat on the cushion beside me as I cried.

“I don’t understand,” I sobbed into her fur. “What did I do?”

“Meow,” she replied in perfect understanding. Perhaps she’d had her share of breakups too. Quite possibly, she just had her eye on the dessert.

What hurts the most about being dumped is the sudden and immediate chasm that comes from no longer being seen. The one person who spent hours listening to you talk about your life on the phone, who was curious about what makes you tick, is now no longer a part of your life. They no longer exist to reflect yourself back to you because let’s face it, our friends and family are a mirror that we rely on to show us our good and bad points. Without them, we sometimes lose perspective.

The cat was polishing off the last bit of ice cream from the bowl as I petted her. She didn’t need any confirmation of who she was. In fact, she was more than happy to be noticed only when it was time to eat. Nevertheless, she indulged me as I sang along to Leonard Cohen.

I loved you in the morning, our kisses deep and warm

Your hair upon the pillow like a sleepy golden storm

Yes, many loved before us, I know that we are not new

In city and in forest they smiled like me and you,

But now it’s come to distances and both of us must try,

Your eyes are soft with sorrow

Hey, that’s no way to say goodbye.

She was a patient cat, but eventually, when the ice cream was gone, she jumped off the couch and disappeared, completely ignoring me as though I’d never been there at all.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sex Education

My parents had the “talk” with me when I was in grade four. I came home from school one day armed with the knowledge that I knew how babies were made. One of the grade six girls confided in me that a woman had to drink male urine in order to conceive. I couldn’t imagine a circumstance that would make me want to do this, regardless of how much I loved the guy. I supposed that was why my mother always talked about all the sacrifices parents make for their kids. I didn’t want to think about my mother drinking my father’s urine or that I was somehow the bi-product of pee. My grandmother always said that God had a sense of humour, but I didn’t find this funny.

“What did you say?” my mother asked me when I looked to her for confirmation. She seemed amused or shocked. It was difficult to tell. “Maybe it’s time your dad and I answered a few of your questions.” And so, after dinner, they sat me down and launched into a version of the birds and the bees that they thought a nine-year old would understand. They explained things pretty well, as far as I recall, and though it still all sounded weird, I was relieved to discover that urine was not involved. The funny thing about that conversation was that weeks later I had completely forgotten it. I mean I got the gist of the whole thing, and even though their explanation was clinically sound, it just went in one ear and out the other. By the time I was in grade six, I couldn’t remember what they had told me and there was no way I was going to ask them again.

We had a lot of books in our house, so it didn’t take much sleuthing to find bits of information here and there and piece it all together. In this respect, my sex education became much more salacious than the matter of fact explanation of two years earlier. D. H. Lawrence, Anaïs Nin, Henry Miller supplied me with much more interesting words and phrases than Dr. Spock. One day I discovered a book with illustrations of barnyard animals copulating (no doubt strategically placed amongst the literature by a well-meaning parent) and my sex education was complete.

‘Remember,” my mother would say, “sex should be with someone you love.”

“What if it isn’t?” I asked, curious to know the consequences of sex with someone you maybe liked.

“Imagine the most depressing Christmas ever, with no toys and only soup for dinner,” she said. Then to really drive her point home she added, “Celery soup! That’s sex with someone you don’t love.”

Point taken. Must love your sexual partner.

“Does it hurt?” I asked my mother.

“Not as much as your heart when he breaks it,” she sighed as she sipped a gin and tonic and flipped through the pages of Cosmo.

Honestly, so far, I couldn’t figure out why anyone bothered, especially as I was always hearing people say, that such and such was better than sex.

“Did you have a good time at the spa?”

“It was better than sex.”

“You went on a shopping spree?”

“It was better than sex.”

“How was the chocolate mousse?”

“It was better than sex.”

What was better than sex? To hear most people talk, you’d think almost everything.

In grade six a sexual predator showed up at our school. Like the bogeyman from a scary story he made his way through the woods on the other side of the fence, and exposed himself to children in the school yard during recess. I never saw him, but the general upheaval and lock down was enough to scare the crap out of me. Whatever he was exposing was dangerous and shocking. We were told to avert our eyes and run inside if he appeared again. Eventually the police arrived, drapes were drawn and they carted him away. Note to self: Male anatomy shocking and dangerous.

In grade eight I had to go over this whole sex education thing yet again, this time with a classroom of my peers. No matter how many times it was explained to me, it always sounded messy and uncomfortable. When I was little, my brother and I used to refer to kissing on film as “mushy ketchup” and the label felt appropriate. As far as I was concerned the whole idea of bodily fluids getting mixed up together just made me sick to my stomach. A fact that would prove prophetic when I finally had sex. Moreover, all the boys in my class were disgusting. I couldn’t imagine them touching me let alone having sex.

“Do you have hairy armpits?” Tony Bianco asked in English class one day. He and his friends laughed amongst themselves in this all knowing, deprecating kind of way. It didn’t help that I was an early developer either. I never needed a training bra. It was just undershirt to real bra for the girl who wasn’t even a little bit interested in boys. God certainly does have a sense of humour. It turned out that sex wasn’t just about copulating. It was also about being objectified and humiliated by boys.

“Well,” I thought to myself, “Jane Eyre didn’t have sex with Mr. Rochester. I see no reason why I should be any different. I will hide behind words with wit as my weapon.” And so purposely made myself unattractive while everyone else was going out of their way to show off any and every positive attribute.

Needless to say, I never dated in high school. I was the weird girl with hair to her waist who did up the top button of her blouse and wore jumpers. For birth control, I used my personality. The only boys who seemed interested in me were the ones who occupied the other side of weird. The misfits who skipped class or were always being sent to the principal’s office for detention. One boy named Rob, sat in front of me in the “dumb” math class. He was the kind of guy that looked like he should have graduated three years earlier. He had facial hair and a deep voice and reeked of cigarette smoke. In every other class I was smart, but in “dumb math” I slid behind my desk and disappeared into the vast expanse of ineptitude. There I was just a dumb girl with boobs who had no future. THIS was apparently attractive. When Rob asked me out I simply said, “I’m sorry, but I don’t think I’m the girl you think I am.” And that was that.

It was easy to tell which kids in school were doing it. They sauntered through the hallways in tight jeans and tee shirts showing off their prowess in art class by drawing perfectly proportioned female nudes. I sat at the table with these cool guys. They were musicians, and political activists. They shunned authority and had a kind of worldliness about them. Girls hung around them like flies. Girls who had sophistication and confidence tattooed to their backsides. Seriously…it was in the drawings. They didn’t take art because it was easy. They were actually talented…more talented than I, which gave them substance in spite of their rebellious nature. One boy, Dave, asked me one day. “Hey, you! Glasses!”

I looked up from my sweet little drawing of a girl on a swing. “Me?”

“What kind of music do you listen to?” he asked. His friends smiled and stopped what they were doing. All eyes were on me. It was a crucial moment. Should I lie? Should I recite the names of cool bands and popular music?

“Stan Getz,” I replied. “Bill Evans, Chet Baker, Sarah Vaughan.” I was deep into it. I waited. Then he simply said, “Cool.” I was in. I didn’t lose my virginity but I lost a little bit of my innocence that day. By the time I graduated public high school I was the nerdy girl that no one picked on. Not in bathrooms. Not in hallways. Not in classrooms. I was nominated for Queen of the Prom and I didn’t even have a date.

It didn’t help that my girlfriends were vastly superior in the art of love. One of my best friends got married when she was just nineteen. I sat under the tent at her wedding thinking to myself that I’d missed a gene or chromosome somewhere. It wasn’t that I preferred women to men. I simply didn’t care one bit about sex. “What’s it like?” I would ask Vicki at sleep-overs. But most of what she described wasn’t the act of sex but the embellishments of romance. Picnics and moonlit nights under the stars, candlelit dinners, flowers…Her family was incredibly wealthy and their house was spectacular. In almost every way, she had the life I wanted. How, I thought to myself, could she give all of this up for a skinny, bow legged opera singer?

I didn’t sleep with anyone until I was twenty. There were a few opportunities and a couple of close calls, but for one reason or another (partially the fear of buying condoms), it just never happened. Then I went away to school and met a guy at a party and fate intervened.

We immediately started hanging out together; having dinner and catching the occasional film. Days turned into weeks and then a month. Things were starting to get awkward. We were on the verge of settling into that friendship zone from which no one ever recovers. Some things can only be delayed for so long before psychologists need to be brought in. It was Oscar night…what could possibly be more romantic? We were in a celebratory mood. There was alcohol and take-out from Balducci’s and dessert, as I recall. The best picture of the year award was announced and I gathered my tote bag. As I began to head out he simply said, “Stay.” And I did.

That year the awards were in March and I remember the window of his bedroom was open. The drapes billowed every now and then as voices from the sidewalk below drifted up to the room. I don’t think nervous does justice to what I was feeling that night. I tried to block it from my mind, but that stupid sexual predator from grade six kept showing up behind the fence. Did I love this guy? Sure. At least it was easy enough to convince myself that I did. And so, I surrendered to the whole enterprise. The usual questions playing around in my head, “What if I’m awful? What if he hates me? What if he’s awful?”

I wore a housecoat and thought about how many calories I was burning.

It was fine. I was fine. He was fine. But afterwards -- I threw up. I don’t think throwing up after sex is recommended. It’s not something people brag about.

“Gee, it was so good, I threw up.”

No one says that.

To my great relief the next time was better. I dated that guy for six years. It turned out I did love him after all. My mother would have been so proud.

In the end, when it comes to sex, maybe W.C. Fields said it best:

Some things are better than sex and some things are worse but there’s nothing exactly like it.

0 notes

Text

The Power of Poetry