Nidodileda is not only about clothing. It's a philosophy, an idea which makes you feel free… #nidoblog curated by Marianna Serveta \\ shop worldwide here // www.nidodileda.com

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Why can’t I have my ice-cream cone in my back-pocket?

Who wouldn't want to make love to an automobile? Who wouldn't be angry if (s)he was stopped from licking the head of a toad? Wouldn't it be crazy to be told by the police to carry your coins in your pockets, instead of your ears? Who wouldn't be driven mad if (s)he had to pay a fine for spitting on a seagull? And I mean.. who wouldn't feel offended for being prosecuted for carrying their violin in a paper bag? But is the punishment of the action or the action per se that is mostly weird?

This kind of questioning may sound paranoid. What is most paranoid though, is that what was just mentioned, among other statements of similar oddity, constitutes actual incentives of the American penal code. Olivia Locher, the 27 year-old sarcastic-conceptual photographer initiated some research on unusual laws and bizarre regulations across all 50 states of America. Without necessarily distinguishing between fact and myth, due to the ambiguity which is nevertheless embedded into the particular (leftovers of earlier times’) need to regulate and constrain offensive action, Locher brought together her Warholian Pop Art aesthetics and her Jodorowskian-inspired fictitious story telling, to pictorially enact these odd laws.

After going through law books, tracking the archaic background of fantastical rumours and cross-examining her various sources, Locher investigated laws like: In Kansas it is illegal to serve wine in teacups, In Nevada it is illegal to put an American flag on a bar of soap, In Texas it is illegal for children to have unusual haircuts, In South Dakota it is illegal to cause static, In Washington it is illegal to paint polka dots on the American flag, In Oregon it is illegal to test your physical endurance while driving a car on the highway, In Maine it is Unlawful to tickle women under the chin with a feather duster. Although all the laws she tracked down might now be outdated and so detached from the needs that justify their emergence (if these can ever be justified) and despite the fact that these are, most of the times, even hard to be enforced in the current context, still some of them are registered in the law books. That does not necessarily bear direct consequences for the rights of the people who might find themselves committed into activities addressed by the odd laws, but it signals quite an arbitrary yet delightfully outlandish character of the legal system -even if that is only in a discursive plan-.

What followed Olivia Locher’s investigation of the twists and transformations of the particular laws and her research on which of them are factual or fictional -yet actualised and reaffirmed by the widespread paranoia-, is her project called “I Fought the Law”. That includes 50 (on of each American state) pictorial enactments of the addressed prohibitions, through her blithe, candy-coloured photographic style. Her cutting-edge irony, her whimsical framing and the cheery insanity that characterises her series, may not only count as a critical commentary on the American penal system but it may even be considered as an iconic tale, aiming to bring attention to the blurred line between actual and believed truths.

The 10 pictures that are presented, are named according to order as following:

In Alabama it is illegal to have an ice-cream cone in your back pocket In Ohio it is illegal to disrobe in front of a man’s portrait In Pennsylvania it is illegal to tie a dollar bill to a string and pull it away when someone tries to pick it up In California it is illegal to ride a bicycle in a swimming pool In Michigan it is illegal to paint sparrows to sell them as parakeets In Missouri it is illegal to deface a milk carton In Delaware it is illegal to serve perfume as liquor In Kentucky it is illegal to paint your lawn red In Hawaii it is illegal to place coins in your ear In Florida it is illegal to appear in public clothed in liquid latex

All pictures are taken from Olivia Locher’s book “I Fought the Law”. No right infringement intended.

Written and curated by Marianna Serveta

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Radiance

“What’s most beautiful, is what disappears before your eyes”

That was the leading directive of Naomi Kawase’s latest film, Radiance (2017), a thoughtful study and meditation on senses and cinema. In the storyline, we are following a writer of audio versions of films for the visually impaired audience, during the processing of the descriptions of her latest movie with a focus-group of blind or partially sighted individuals. Among the individuals of the focus-group is a photographer, who is gradually losing his sight, yet desperately struggling to hang on to the fragments of the visual world. While the plot unravels itself, we are following various layers of narrative and story-telling in forms of synecdoche (interrelated levels of analysis), quite untypical for the Japanese style of film-making.

The dimensions that mostly touched me though, are the multifarious narrative of the relationship between the photographer and his camera and the essentiality of “visual silence” so that to trust the other senses with a similar devotion. The first dimension, is gradually explored through the observation of the character’s drama: while watching and, in cooperation with the writer, processing “Radiance” (a film within the film) the photographer who is slowly losing his sight, gives the mostly harsh criticism to the writer’s work. That brings about the mistake that is often made, when people give overly detailed analyses to blind individuals and by that underestimating the rest of their senses, that are actually working overtime. But most importantly, it gives rise to the fear of a person who has built his life on the power of his vision and gradually feels it fading away. Despite the various compelling scenes where the actions of fatalism he is progressively driven to, are explored, there is one line wherein his camera is metaphorically parallelised with his heart and he simply yet disarmingly states: ““I still carry it with me, although I cannot use it anymore”.

The second dimension and the “visual silence” which was mentioned, falls better in place with the Japanese life- and film-making style. That entails the tight connection of the Japanese people with nature and the realisation of their bodily functions as coordinated with those of the Earth, in consonance with the spiritual and cultural specialities of Japan. Both technically in the film-making process: where the natural autumnal light and the forest sounds were used, and theoretically, in the attributes of the story: where the completeness of the characters is determined by a wide array of elements that lie outside the limitations of the visual reality, what is created as a need for each respective subject is to just pause whatever they are doing for a while, close their eyes and “listen” to all the other forms/parts of reality that are spinning around them. In order for that understanding to be enabled, silence is both a prerequisite and a consequence. However, silence is not conceptualised as an empty space of stillness, but as the most inclusive form of meaning, where there is no need for it to be explicitly displayed. Thus, the use of it for making full use of our senses, was gracefully summarised in one of the characters’ statements, an old man (otherwise the iconic Japanese actor Tatsuya Fujiwho) who is acting in the film within the film and whose silence is tried to be understood by the writer in order to be better described for the blind audience: “I will be deeply touched if a young woman like you can appreciate the poetic nature of the view of an old man’s silhouette walking away”.

Naomi Kawase’s film will be criticised in various ways by film-critics due to its multilevel structure and wide thematic outreach, including the view of it as a “manual” of how to watch cinema, of how to incorporate handicapped people in artistic narratives, of how to view the self as a result of, or as emerging from complex realities. Yet, my appreciation of it lies mainly with the complementary function of the quote lastly presented with the one initially used: “What’s most beautiful, is what disappears before your eyes”. By the parallel reading of these two, it becomes clear that it is not the self-destructive element of the material substance which was to be focused, but the evanescent character of existence, and due to that, the need of it to be grasped by the activation of all the body’s senses.

Photographed by Vahe Hovhannisyan Written and curated by Marianna Serveta Feat. “Compass” embroidered faux fur coat and “Elio” velvet embroidered top/dress.

#nidodileda#nidoblog#stockholm#gamla stan#elio#compass#embroidery#radiance#film#light play#storyteller

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Where did the sound go?

I was slowly walking on the wooden floor of the Hallwyl hall, staring around mesmerised at the medieval Renaissancian elements of the architectural design. Letting the touch of the thick light on the colourful ceiling, narrate through iridescent haze the scent of the stories of the people who similarly walked down this halls, since the medieval times. Yet, the melancholic hues inside me were not fuelled by the realisation of the passage of time, nor by the typical longing of eras and elements of these eras, which although are past feel much more real and actual than the present. My melancholy was mainly aroused by the realisation of sounds, that die away and die out because in one way or the other, nobody needs them anymore.

All this was initiated by the stable creaking sound, made by my heels on the aged floor, coupled with the sporadic soft tinkling sound the metal objects decorating the heavy furniture in the rooms were making, as I shook the floor under them. It was the sound that enabled me realising my own slight, basically unimportant imprint on the room or the time: there and then. I reckoned that otherwise, I cause that sound only when I am at an old person’s house, as if the creak-tinkle sound combination is age or era specific. As if our modern time, in order to lighten up its luggage of inherited properties for the sake of functionality, decided to gradually leave behind sounds that do nothing more that sealing the moment with signs of physical consciousness.

Thus, I allowed myself to embrace that kind of melancholy by reckoning similar sounds. Probably due to the atmosphere of the Hall, what came to my mind straight was that plopping, hiss-like sound caused when a bottle of wine is opened. The shortest sound of celebration, which aims to control the escaping airflow, while what the ear grasps is a sound similar to a liquid exploding behind someone’s lips. Then, I thought about the rustle sound of sheets of paper when they move because of the air coming in from an open window, or because you sit too close to someone at the library. Someone who is not maniacally typing on a computer, but gently turns the pages of his notebook. A sound that is as soft as the landing of his breathe on you would have felt, if you sat even closer to him

A less material-related sound that came to me straight after, is the crunchy, crackling squelch sound of winter boots walking on fresh snow on a sunny day, when everything is still and glittery quiet. Or my personal favourite, that of the fizzing, bubble-bursting, crawling sound of the waves licking the shore of the beach. Even the chirping, short-whooping sound of sudden surprise when unexpectedly stumbling across a loved one from the past and feel freed-from-social-conventions enough, to out-loud cheer about it. A sound that I hardly ever hear or notice anymore and probably dies out, along with the principles of spontaneity. All of these sounds, and others that are probably more meaningful to each and every one of us, may not be era-specific in the same terms, but their gradual disappearance may be warning for the transition to the minimalistic or reductive tendencies of functionality. It might not necessarily be that the modern-age needs will gradually eliminate them, but still by detecting them within our pleasure-basket, by addressing and specifying them and locating them in time and space, so that for their detection -even in gradually less occasions- to be facilitated, their maintenance, at least within our consciousness, can be safeguarded.

Featuring “Alba” embroidered lace dress Written and curated by Marianna Serveta Photographed by Emma Sundkvist. Special thanks to the warm and worried heart of L., to whom this is dedicated.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Wrapped but unbuttoned

Ronald Barthes, the French pioneer literary theorist, philosopher and linguist whose work had a paramount impact on the history of structuralism, semiotics and anthropology, asks in his book The Language of Fashion the following rhetoric question: “Are not couturiers the poets who, from year to year, from strophe to strophe, write the anthem of the feminine body?”

What was succeeded with that inquiry, is for the semiology, or the symbolic capacity of clothing per se and the normative character of such a capacity, to be given the appropriate attention. That is because despite the so far tendency to first view the body and after the garment, Barthes, managed to summarise in his statement some decades ago, the reality of our age: that in order for the body to be realised, the garment becomes the precondition of attention. Every season that fashion changes, new types of bodies and womanhood are generated, and so the body becomes a canvas, a systematic space of alternating signs. The way that is proposed in order for that to be understood, is to observe some classic examples of the big screen. That is because since Barthes addresses the semiotics of symbolic representation, then the symbolic construction of standards of beauty through an important vehicle of mass culture, which is cinema, is found most relevant.

Layers as statements: 10 coats that are hard to be forgotten The examples are countless, but the collection chosen hereafter does not aim to solely reflect stylistically strong pieces, which would necessitate for Fransoice Hardy’s famous mod-touched trench or Sean Connery’s landmark-for-costume-design Victorian coat in the “first great train robbery”, even Gene Hackman’s seemingly rudimentary raincoat in Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Conversation”, or Rita Hayworth’s lavish couture in “Cover Girl” to be mentioned, in order for the influence on the fashion design to be merely emphasised. Instead, some examples that are evaluated as highly influential both for a quick fashion-history of the big screen overview and for the actual film-plot unravelling and furtherance, are the following:

1.Tippi Hedren’s green hip-length, Chanel-like coat at Alfred Hitchcock’s “Birds”, which aesthetically connects it to the dateless simplicity of Grace Kelly’s celadon-green suit in “Rear Window”. In the Birds, the shade of green, which matches the love-birds’ colour that the protagonist buys for her sister, ironically signify the character identification of the protagonist with the birds: as reckless and playful, yet of mysterious and noxious nature.

2. Julie Christie’s breathtaking light-brown fur coat in David Lean’s “Dr Zhivago”, which was used to semiotically illustrate social change in Russia, after the ideological upheaval following from war and revolution.

3. Anne Bancroft’s heavy and glorious Cheetah coat in Mike Nichol’s “The Graduate”, which is the stylistic embodiment of temptation and allurement, while it brilliantly signals the maturation it will lead to, when it comes to the plot.

4.Louise Brook’s white, see-through light kimono-coat in Georg Wilhelm Pabst’s silent “Pandora’s Box”, depict in the most suitable way, the protagonist’s insouciant, innocent yet dazzling and lustful eroticism, which does not only summarise her character but also gives incredible hints about the film’s plot.

5.Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep’s composite mix of tan and beige, cotton-weave Burberry trench coats in Robert Benton’s “Kramer vs. Kramer”, where Streep’s trench maintains the contemporary version of the classic noir silhouette and where similarly Hoffman as a symbolic victim of the “femme fatale”, has given his uniform to her. Figuratively, the straight and classic lines of the Burberrian creations, parallelise the strict coats with control mechanisms, while at the same time the gradual colour shifts of Streep’s coats signal a discreet pro-feminist gradual message of the chosen couture, as reflected on the plot.

6.Catherine Deneuve’s effortless, Parisian-chic light grey trench coat in Jacques Demy’s “Umbrellas of Cherbourg”, which epitomised the simplicity yet strength of the representational narrative.

7.Sigourney Weaver’s big buttoned, oversized, wide check, dramatically dark blue cape coat in Ivan Reitman’s “Ghostbusters”, felicitously illustrating the frosty yet eventually melted character of the protagonist, within the storyline.

8.Angelina Jolie’s plush-fur trimmed coat in Clint Eastwood’s “Changeling” which seems to be allegorically wrapping and muzzling in a conservative 1920’s-inspired way, the frail and exhausted body of a driven-to-paranoia mother, in search of her son.

9. Gwyneth Paltrow’s toffee coloured, Fendi, fur coat in Wes Anderson’s “The Royal Tenenbaums”, beautifully summarising the difficulty of the estranged characters to meaningfully interact with each other.

10. Sharon Stone’s white shawl neck wrap-over coat in Paul Verhoeven’s “Basic Instinct” with its obvious stylistic reference to the Hitchcockian “Vertigo”, which exposed in the most representative way the protagonist’s core element: that her intelligence can be hidden in plain sight.

The discussion regarding the effects of such a semiology of representation on the shared view of aesthetics within a culture, in consonance with Barthes theorisation, could be extended and of great interest. Yet, for now, I may conclude that the powerful element of a coat contra a photograph, is that the former necessitate touch and scent to evoke memories and create impression, while the impression-ability of the later, rests on its pure dynamic of representation.

Written and curated by Marianna Serveta Photographed by Emma Sundkvist

Featuring “Pascal” white wool lace light coat.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

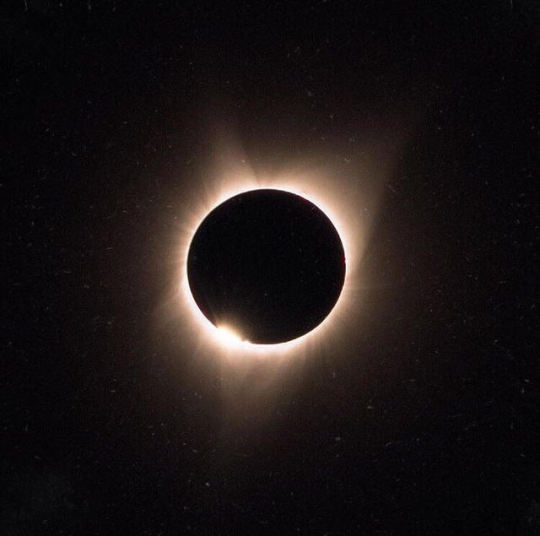

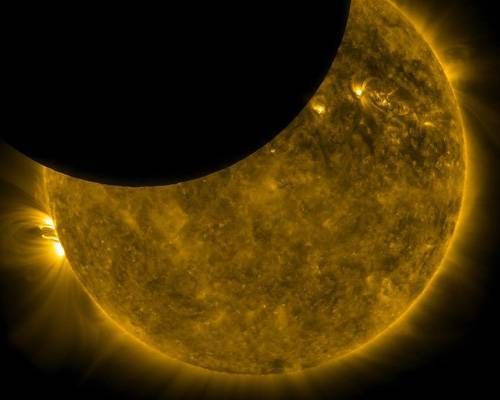

Lunar Eclipse elements

What is it that makes people enchanted by glow? What is it that makes them slow down when passing by small, light bulbs in the middle of the night when they have so much light spread over everything around them, during the day? Is it the light’s attitude when it concentrates itself in small spaces and proudly stands against cosmic darkness, laughing at this world of dust, that makes it so special? Or is it that despite its evanescent, slender character, it still finds the way to celebrate its multifold nuances which signal its gradual surcease? Despite our common yet natural agony in absence of light, when a sunset is over, when the lights go off, there has always been the same amount of light in the world, something that should be guaranteeing that despite its periodical absence, even in the case of an eclipse, the light returns and the eclipse does not become endless night. Because, as H.D. Thoreau has stated, the new and missing starts, the comets and eclipses do not affect the general illumination, nor the light circulation. Yet, there are two kinds of people: the ones who use that guarantee as an excuse for not paying particular attention to the moon and the light circles, since.. “they will be there to examine even tomorrow”, and the others, who sometimes wake up early enough to see the sunrise, who plan their afternoons according to the sunset and when there’s full moon, they insist in trying to solve Paulo Coelho’s enigma about what the relationship between the lunatics and the moon is, so that for insanity to be dressed in moonlight gowns, in most tales.

This last category of people, who also happen to identify with Anton Chekhov’s quote “Don't tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass”, who deeply appreciate its delicate, precise, like a paper-thin-slice-from-a-cabochon-jewel form, and try to find ways to bring it down to their own terms, these are the ones who appreciate the silent way it bathes the earth with solitude and who keep track of its travel, its orbit and its hues. Alternatively, if we are to use the rhetoric of the planets, these are the people who choose the lunar over the solar eclipse. And that can be explained: During the lunar eclipse, the moon acknowledges its adornment for the periodical darkness, it passes behind the earth and slips for sometime into the earth’s shadow. That necessitates two things: a full moon, and the earth to be exactly in the middle of the fully aligned sun and moon. This is the moment, when the natural reflections of sudden fear would come about, because the sunlight is blocked by the earth’s shadow. Yet, there is some reddish light, a kind of light that resembles that of the sunsets, which escapes the shadow and makes the sunny halo around the moon, visible. Unlike the few-minutes-long and harmful for the eyes solar eclipse, the lunar eclipse lasts for some hours and due to its dim yet star-borrowed pearly glow, it can be stared at with a naked, brave and dream-prone eye.

For the ones who embrace darkness with the mental visualisation of a sky of silver, with a crescent, lavender moon. For the ones who identify symmetry with the random plays between the sun and the moon -where although the sun is 400 times larger than the moon, it is also 400 times farther from Earth, making the two bodies appear the exact same size in the sky-. For the ones who see in the reddish hues of the moon -when the sunlight is filtered through the atmosphere-, the cumulative glow of all the world’s sunsets. For the ones who find truth in Tom Robbin’s statement, that “there is no point in saving the world if it means losing the moon”. For the ones who can welcome autumn as we do, with colours easier to be seen in the night, with textures soft as the immaculate purity of hanging-in-the-sky astronomical bodies, with a balance borrowed from the moon phases.

Lunar Eclipse.

Written and curated by Marianna Serveta, Photos taken from the upcoming collection gallery (including details from Elen Aivali’s photo-campaign)

#lunar eclipse#nidodileda#nidoblog#collection launch#new collection#moon phases#lunar eclipse elements#black#gold#presentation#ourphilosophy#details#coming soon

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What the water gave me Time it took us

To where the water was

That’s what the water gave me

And time goes quicker

Between the two of us

Oh, my love, don’t forsake me

Take what the water gave me

And oh, poor Atlas

The world’s a beast of a burden

You’ve been holding on a long time

And all this longing

And the ships are left to rust

That’s what the water gave us

Because they took your loved ones

But returned them in exchange for you

But would you have it any other way?

Would you have it any other way?

You couldn’t have it any other way

Because she’s a cruel mistress

And a bargain must be made

But oh, my love, don’t forget me

While I let the water take me

So lay me down

Let the only sound

Be the overflow

Pockets full of stones

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=am6rArVPip8

Out of personal evaluation, one of the first and probably most important songs made by Florence Welch, the lead singer of Florence and the Machine, is “What the water gave me”, whose lyrics are attached above. This is because she managed in such an early stage of her songwriting career to already summarize the highlights of her musical genre, the softness of her aesthetics and the strength of her image- and word making. It is not only the power of the musical mastery, but the combination of the sources of inspiration that basically succeed to blow my mind: That is Frida Kahlo’s series of paintings that are depicting herself lying in the bottom of her bath, surrounded by nightmarish imaginary, coupled with the image of Virginia Woolf, who drowned herself after walking into a river with her pockets filled with stones. Although the element of water is continuously repeated throughout the album “Ceremonials” for different reasons, the focus on drowning that distinguishes this one from the rest of the collection, gives water an interesting quality: that of the punisher and the daredevil at the same time.

Florence parallelizes the overwhelming feeling of drowning with that of utterly falling in love for the first time. She even describes during her interview for NME how she sat at the bottom of a swimming pool, while on family-holiday, screaming at the top of her voice, to manically express her encapsulated feelings for the first boy she fell in love with. Despite such a parallelization, the most dramatic description she gives in her lyrics, out of issues of personal concern (in the statement: “They took your loved ones and returned them in exchange for you but would you have it any other way”) is that of the parents who dive into the sea to rescue their children, yet due to their weight, if it is for the one party to survive, then that will now be the parents: as if the survival of the one necessitates the sacrifice of the other. Because of the erotic aura that swings above the feeling of the song, even that sacrifice can be appreciated as a sort of self-abnegation, or as an indication of the realism which nevertheless underlies the relationships that are characterized by intense emotion.

However, the part of the song that fully captures me, is the lyric “So lay me down, Let the only sound, Be the overflow” due to its cruel simplicity and its penetrating allurement, which summarizes the feeling of the long summer-dives that take your breath away and make the water-plop the only affordable sound. It summarizes the moments of honest and all-embracing solitude: when the body gets loose under the mild oscillation of the water streams, when the eyes are only opened to perceive the play of light on the upper levels of the water-curves, when the fingers wrinkle in order to make the grasping of the slippery water-form elements still possible, when the lungs are ready to explode yet their destruction feels more right than ever before. When there is no guilt and no worries because the heavy weight of both, dissolves under the very rules of the nature. When disappearance is enabled for as long as the lungs permit: ironically revealing how magic can still be employed by the abilities of the body. When the shadows of the bottom cannot be terrifying, since the pure coordination of the rules of nature with those of the body, leave one way possible: and that is to be lifted upwards.

Dedicated to A. together with whom I was introduced to the mesmerizing world of Florence, which keeps us connected despite the long pathways of the actual world. Lensed and written by Marianna Serveta,

Special thanks to Eleni Konidari for modelling for me.

Featuring “Echo” Bikini.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

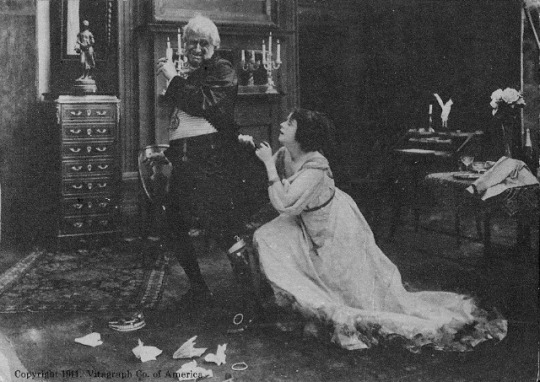

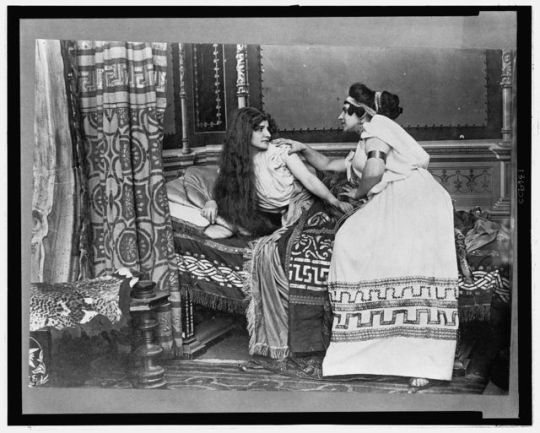

Silence A Silent-Screen Overview: Part 2.

Completing this journey across the period when the images were strong and meaningful enough to leave no space for the need of auditory input, the overview will start from 1916 and will continue up to 1929, although the last pieces that are mentioned regard 1936. Following the highlights of the years mentioned and gradually observing the replacement of the purity in emotion with the exaggeration in its portrayal, the swan song of the cinematographic naivety will be discreetly mentioned as well.

1916: D.W. Griffith’s second large scale production after “the Birth of a Nation”, is “Intolerance” with the out-of-space Lillian Gish and the rare persona of Douglas Fairbanks, which undoubtedly made 1916 an essential cinematographic year. What contributed to this, is the ongoing success of Mary Pickford, whose pictures were even distributed by the Artcraft Picture Corporation. Moreover, it is now that Charles Chaplin is considered the highest priced film star in the industry, after having signed with the Mutual Film Corporation. “Sherlock Holmes” with William Gillette is signed by Essanay this year, Norma Talmadge stars in “Going Straight” and Triangle releases the Fine art production of the Shakespearean “Macbeth”.

1917: Important contributions to the history of the silent screen were made in 1917, including the first all-colour feature film “A Tale of Two Nations” and the Williamson Brothers’ “The Submarine Eye” due to its underwater scenes. The charismatic director and storyteller Herbert Brenon made his exceptional “The Fall of the Romanoffs” this year and the Mack Sennett “Keystone Comedies” were released, including the “Bathing Beauties” as a means to cheer up the World War soldiers. Despite the cinematographic quality of the following films, what is also a contribution of this year, is the alluring costume creation, all evident on Theda Bara, throughout all her performances, as for instance in “Cleopatra”, “Camille”, “Du Barry”, “Cigarette”, as well as on Valeska Surratt and Virginia Pearson. Although the serial days were almost over, the “Seven Deadly Sins”, “Patria” with the astonishing Irene Castle and the “Mystery Ship” were created this year.

1918-1919: The war was gradually having greater influence on the film production. 1918 may be called the year of Propaganda, which is obvious through “Lafayette, We Come”, “To Hell with the Kaiser”, “The Beast of Berlin”, even Griffith’s “Hearts of the World”. What basically relates these two years when it comes to the practical matters of film production, is the combination of firstly the downturn that important colosseums of production were taking (like Vitagraph and Pathe) and secondly, the meaningful handling of Adolph Zukor. Zukor, whose philosophy was that important actors should reinforce through their fame the success of the film, did his best to keep in the game the corporations he participated into. During that, important movies were released like “Les Miserables” with William Farnum, “The Danger Game”, “Captain Kidd Junior”, “The Sheriff’s Son”. Moreover, essential Griffith creations were “The Girl Who Stayed at Home” and the unforgettable “Broken Blossoms” where Lillian Gish, an abused by her father daughter, is taken care by a Chinese immigrant, (the unbelievably expressive and eloquent Richard Barthelmess) something which ended up having even worse social effects on her. Many actors were given contracts from the newly established corporations, among them was the talented Nazimova (who stars in “The Red Latern”, “Out of the Fog” and “The Brat” this year), Gloria Swanson (staring in “For Better for Worse”, “Male and Female”) who were to considerably affect the world scenes.

1920-1921: The United Artists Corporation was now created, by the four most important names in the pictures: Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, D.W. Griffith and Charles Chaplin. Another highlight of the year, was the random discovery of Jackie Coogan by Chaplin, who played “The Kid” and became a star immediately. 1920 may be called the year of the great talent discoveries, because apart from Coogan, the actress Pola Negri and the director Ernst Lubitsch were bought into attention after Griffith’s “Way Down East” and “Passion”. Similarly, an outstanding talent discovery of the next year is that of Rudolph Valentino who gets the full attention of the audiences through his performance in “The Four Horsemen of Apocalypse”, “The Conquering Power” and “the Sheik”. Two radically different productions of 1921 that worth mentioning, are the ultra sensual “Camille” with Nazimova and Valentino and the purely naive “Coincidence” with June Walker and Robert Harron. Other than that, after the success of “Passion”, there were plenty German productions that managed to hit the box office, among them my personal favourites are “The Cabinet of Dr.Caligari” and “Deception”.

1922: If it can be stated that there has been a year where experiments took place before the silent screen, then 1922 is undoubtedly that. The charismatic Mexican dancer Ramon Samanyagos who changed his name to Ramon Navarro, performed outstandingly for “The Prisoner of Zenda” and Robert J. Flaherty’s “Nanook of the North” is categorised among the very first documentaries of all times. That indicates how even history can be narrated by the simplicity yet mastery of the bodily movement. Moreover, Nazimova’s “Salome” whose sets were based on the drawings of Beardsley can be evaluated as an artistic orgasm, although it was not a box-office success. Since theatricality was boosted even further through Salome, Marion Davies continued to create her extravagant elaborate costume pictures and D.W. Griffith did a remake of the “Two Orphans” as “Orphans of the Storm” which was even more expressive and complete than before, and where Lillian and Dorothy Gish’s stills can be easily mixed up with black and white paintings.

1923: Greta Gustafsson or Greta Garbo: The name that was to shake and reshape the film history, firstly appeared this year, and this is probably enough to mention. Her performance in “The Atonement of Gösta Berling” was followed the same year by “The Hunchback of Notre Dam”, where it is made clear that the weird make-ups and genres are what fit her fine. Other than that, the heartrending Pola Negri, after her feature in “Bella Donna” justifiably becomes the only honest rival of Gloria Swanson. Despite the wide film production of the year, what may count as an essential contribution to the film evolution, is Fritz Lang’s “Siegfried”, due to its flawless photography which although inspired and was referred to in movies some decades later, had a direct effect on Chaplin’s “A Woman of Paris”, in the same year.

1924-1925: The public demand for big pictures made only the large-scale efforts of these two years to be appreciated by the audience. This indicated that it was all about the survival of the “bigger”. On 1924 such syllogism is proven right through the success of Fairbanks’ “The Thief of Bagdad”, Pickford’s “Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall”, Davies’ “Yolanda” and “Janice Meredith”, Griffith’s “America” and First National’s “The Sea Hawk”. Similarly, on 1925 it was basically “The Phantom of the Opera” with the brilliant oddity of Lon Chaney, Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush”, “Stella Dallas” and the astonishing “Last Laugh” by F.W. Murnau which is considered as the most complete and perfect film ever made, as it didn't even have descriptive subtitles.

1926 and the gradual death of silence: The beginning of the end of the silent screen was signalled by the creation of the Vitaphone, bought by the Warner Brothers, to reproduce sound after being synchronised with the film projector. The first trial of the Vitaphone was through “Don Juan” with Barrymore, followed by the “Jazz Singer” with Al Jolson the year after. Apart from that, with the colour process called technicolour Fairbanks created his film “The Black Pirate”, slowly bringing about another indicator of the end of the silent screen as it was known. “Ben Hur” and “Variety” were the aesthetically highlights of this year, together with the sealed stardom of Gary Cooper and Greta Garbo.

1927-1929: During 1927 and probably due to the increasing technical support, the standards of success were reshaped. Yet, a reminder of the straightforward mastery of the silent screen is “It” with Clara Bow, when “It” became synonymous with sex appeal and for a short time the constructed needs for technical evolution, were forgotten. Step by step, the “talkies” came to replace the silent pieces: dialogues were more often added and musical backgrounds were more and more synchronised to the motion. “Abie’s Irish Rose” was a “part-talkie” movie, followed by “Our Modern Maidens”, “The Kiss”, even “Wild Orchids”. Silent screen actors started taking voice lessons and by the end of 1929 the majority of the theatres and production companies were “wired for sound”. The farewell to the art through which everything was fully expressed even without the help of words, were given by Charles Chaplin through his “City Lights” and “Modern Times”, as the last silent but dignified cry for the simplicity of communication.

This overview was not to glorify the characteristics of the film-period mentioned, as if those could apply to the needs of the present. Instead, by observing the gradual evolution of the cinematographic genres, the themes that were more common, and the standards that were set through the specific types of performance, it was made clear that, back then, when the technical means of impression-making were lacking, the strength that the actual feeling was having, stripped down to its simplest form and expressed by the abilities of the body, was what really mattered. It is probably a massive collection of films to watch, but in case any of the readers decides to give some a try, then the question that can be thought over is: If the technical means that are now used for the impression- and atmosphere making, affect the complexity of the feeling portrayed, what is sacrificed so that for that feeling to still seem the same?

By Marianna Serveta Photos taken from the British Film Institute Gallery, no rights infringement intended.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Silence

A silent-screen overview: Part 1.

Crawling through my parents’ treasure-house, which is their library, I always stumble across pieces that form the right excuse to periodically detach from the world. This time, Daniel Blum’s pictorial history of the silent screen made me watch or re-watch films that might sound outdated, but they actually formed a reference point or security zone for me. This regards issues that seem to be happening mechanically, yet the knowledge for their performance cannot but have derived from the simplest form of storytelling: the silent screen. If this sounds too cliche, then I have no other answer than a question: How would we know how to kiss if it wasn’t for the first, black and white, voiceless film kisses?

This piece will be a view over the very beginning of the early classic period of film history, mostly centred around the American production. It will start from Thomas Alva Edison’s invention of the kinetoscope on 1889, which was initially used by Alexander Black’s photographic slides -projecting four slides a minute, where each one of the four pictures was a step forward in action- to give the cinematographic highlights of the years following and end up around 1936, when the last silent film was released and when the plans for the new audible screen took completely over. The overview will be divided into two parts, one indicating the highlights of the period 1908-1915 and the other, of the period 1916-1936, so that for the reader to better keep track of the information.

Ironically, the very first recorded film was that of Fred Ott, an assistant in the motion picture studio, who kept sneezing before the Edison camera and because of that, the need of maintaining and depicting the simplest kinds of motion, became more evident that ever. This was followed by simple motion pictures, including among other, the classic “Buffalo Bill” and the astonishingly simple but hard to erase from one’s memory “Annabelle’s Butterfly Dance”. On 1894, the year when the first film was made, Woodville Latham created the first projector, called Pantoptikon, followed by a similar attempt in France by Louis and Auguste Lumiere, which formed the base for the evolution of film making, as the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, the Vitagraph Company of America and other French and American pioneers started actively entering the stage of competition. During this period, the unforgettable kiss of Irwin and Rice in “the Widow Jones” formed the building blocks of the romantic visual narrative and Edison’s “The Great Train Robbery” along with Melies’ “Trip to the Moon” framed the beginning of the action filmography.

1908: During these first years of film making, most of the film studios (including Biograph, Selig, Vitagraph) were turning out one to two films per week, after hiring actors and actresses as their stable cast. It was then when Lawrence Griffith, Linda Arvidson, Mack Sennett, Violet Mersereau, Kathlyn Williams officially started their careers, although the names of the actors were not allowed to be given out. The choice of topics were theme-based, including mostly Shakespearean adaptations of for example “Antony and Cleopatra”, “Romeo and Juliet” or accordingly “the Roman”, “Ingomar, the Barbarian” or the outstanding “When Knights were Bold”.

1909: The audience started showing increasing interest and so more and more people came into the production, bringing their own cultural background and taste and creating gradually more studios and even independent companies. “A true Indian’s heart”, “The Slave”, “The Violin Maker of Cremona”, are some of the exceptional creations of this period, whilst the theme-based choices were continued with the example of Tolstoi’s “Redemption”. Among the beautiful one-reel features of 1909 were “King Lear”, “Oliver Twist”, and “The Prince and the Pauper”.

1910: The scepticism regarding the anonymity of the actors was brought about this year, exhibitors were searching for new kinds of attractions and the element of colour was bidding for attention. Pathe, started their colour-films, with most important ones those of “In Ancient Greece”, and “Carmen”. Other outstanding pieces were: “The Life of Moses”, “Comrades”, and the “Angel of the Studio” where Florence Lawrence proves with her great looks how essential the specific costume design for the film industry has already become.

1911: The value of the actors as stable players started increasing and they started switching among the film companies in terms of business. Companies continued filming the classics: “David Copperfield”, “The Three Musketeers”, the jaw dropping “Faust” and Dante’s “Inferno” and two versions of “Cinderella” -with personal favourite that by Selig-, were among them. Vitagraph’s highlights of contribution this year were “Vanity Fair”, “Mother” with the heartbreaking Mary Maurice and “A Tale of two Cities”.

1912: This was undoubtedly an essential year for the growth of this type of art. Better theatres were being built, the famous stage actors of the period began to look on motion pictures with more favour and technically, the means were greatly evolving: the one and two reelers were gradually replaced by three and four-reel pictures. This practically meant a better continuity of the storyline through/and a better emphasis on the actors’ skills. Marcus Law Enterprises which was in charge of screen and vaudeville theatres was created, through which the rights of “Queen Elisabeth” with the exceptional Sarah Bernhardt were purchased. A handful of films that form milestones of the silent screen were imported this year through this movement, including “Camille”, “Last Round -Up”, and “The Merchant of Venice” with the astonishing Harry Benham. Moreover, the Mutual Film Corporation was formed this year which brought together various (independent) companies, broadening even further the types of production. It is in 1912 that the Keystone Comedies were initiated, beginning with “Cohen at Coney Island” on September 23.

1913: The import of foreign films continues with the great successes of “Quo Vadis”, “The Last Days of Pompeii”, “Les Miserables”. Yet, the American production grows even further with the examples of “Judith of Bethulia”, “Caprice”, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, even “Ivanhoe” with Herbert Brenon who later made a meritorious career s director. “Rainey’s African Hunt” which was a mixture of real-footage documentary and adventure, was the actual forerunner of the Johnson’s famous adventure films. During this year, there are two actors who appeared before the camera and were about to shake for real the world of film: Kathlyn Williams with her debut “The Adventures of Kathlyn” and Charles Chaplin with “Kid’s Auto Races”.

1914: The attempt of creating serials was initiated for once again, this time by Pathe with the great success of “the Perils of Pauline” with Pearl White, whose honest aggression, pure guts and passionate play gave her the title of the “serial queen”. Other series of the year were “Lucille Love”, “the Million Dollar Mystery” and “Dolly of the Dailies”. Important pieces that are hard to forget are “Samson” with the extraordinary performance of Kerrigan and “the Spoilers” with the historic fight scene between William Farnum and Thomas Santschi. In 1914, both the Paramount Picture Corporation and Alco Film Corporation were formed releasing the “Famous Players”, “Lasky” the former and the remarkable “Nightingale” with the glorious Ethel Barrymore, “The Last Vampire” with Petrova and another classic Keystone Comedy called “Tillie’s Punctured Romance” with Chaplin, Normand and Dressler, by the later. Also, it was during this year that Francis Bushman the Ladies World Hero contest over, among other, the exceptional Maurice Costello. D.W. Griffith, the man who is known for his innovations and special practices, among which the fact that he was the fist to use the long shots, the close-up, the fade-in and the fade-out, filmed at this time “the Battle of the Sexes” and “Home Sweet Home”.

1915: The last year to be reviewed in this article, is 1915 an ultra productive and essential year for the history of cinema, mainly because of the actors that it shed light on. Starting from one of the most famous films in the tradition of the silent-movies, “the Birth of a Nation” by Griffith, it worths mentioning that it did not only break all theatre records wherever it was shown around the world, but it also involved actors that were to belong in the star system thereafter: among them, the authentically melancholic Miriam Cooper, the hunting Mae Marsh and the smashing Henry B. Walthall. The idea of using famous cast in famous plays, pushed even further the importance the star system was acquiring. The stage personalities that were beyond comparison, due to the offers they got were John Barrymore, Hazel Dawn, Marie Doro and Mary Pickford. To add to this promotion of the star system, the opera star Geraldine Farrar was signed to play in films this year, -with a personal favourite her feature in “Carmen”- which gave even further advertisement to her cast.

Another great personality of the year, was the producer Oliver Morosco who, together with Bosworth, produced “Jane” with Charlotte Greenwood, “Kilmeny” with Lenore Ulrik, and the beautiful “the Yankee Girl”, “Captain Courtesy” and the “Alien” with the thrilling George Beban. Other independent releases were “The Dragon’s Claw”, “The Devil’s Darling” and the “Whirl of Life” that may be categorised in the all-time-classics. From the stardom of the year, Theda Bara cannot be excluded, since her appearance in “A Fool There Was” guaranteed her position within the star system as well. Pearl White, who was mentioned before due to her success in the “Perils of Pauline” continued her success through her feature in the serial “The Exploits of Elaine”, reminding her name in the public. World War 1 was in progress, and that for sure had an effect on the topic choice, although with discreet references at this point. Despite the fact that it is not necessarily representative, an example of that can be “The Battle Cry of Peace” made by Vitagraph. Nevertheless, it is in 1915 that Chaplin makes “His New Job”, “A Night Out” and “The Champion”. In this year, the Triangle Film Corporation was established, a fact which worths mentioning due to the fact that Douglas Fairbanks, one of the greatest features of the silent screen and William S. Hart the cowboy star, were included in the outstanding array of names of the corporation.

Concluding this first part of the silent-screen overview, it should be stated that despite the focus on mainly the American production and by acknowledging that there has also been tremendous influence from the global scene, it is exactly these films above that have formed the visual aesthetics of the present screen. The vitality of this silent depiction is felicitously portrayed by Alfred Hitchcock, who is given the last word: “In many of the films now being made, there is very little cinema: they are mostly what I call 'photographs of people talking.' When we tell a story in cinema we should resort to dialogue only when it's impossible to do otherwise. I always try to tell a story in the cinematic way, through a succession of shots and bits of film in between.”

By Marianna Serveta Photos taken from the British Film Institute Gallery, no rights infringement intended.

#silent movies#silent screen#daniel blum#alva edison#d.w.griffith#review#chronicle#nidodileda#nidoblog#pictorial history

1 note

·

View note

Photo

On the edge

There are some films whose sensuous delight reminds us of the rules of seduction that we desire for our erotic stories. And there are some feelings that regardless of how much we believe that we own them, they eternally bear the need to be maintained unspoken, due to the risk of destruction their addressing and emergence into the world of desires, may entail. Sometimes there are films that you are asked to recall and describe in detail. The kind of film that you remember how intensively shook your world, and so you are certain that, upon request, you can outline all the small features that make it so special for you. But then, when the time comes, ‘feelings creep up on you unawares’, and make the memory feel like a perplexing blend of aesthetic and emotional expectations from the cinematic smorgasbord of lush romantic fatalism. This is exactly how Kar Wai Wong’s “2046” affected me, with the mystifying seduction the interplay among three different levels of reality created, as it is probably these three levels that were guaranteeing the protection of the feelings described. With the confusion which was created by the bright Asian colour schemes as alloyed with the unexpected musical sounds of the West, typical in Wong’s filmography.

Such a blend, is an attribute which although has been perceived as a characteristic of his cinematographic mastery in the past by me, after having lived in Hong Kong, -the reference point of his work-, for long enough, it came to be understood as an actual and realistic depiction and representation of the leftovers that colonialism has left on the city. This means that regardless the alluring aura that the director aims to create by his technical means, the aftertaste that the film leaves you with, is similar to what is felt after waking up from a short nap in a summer afternoon: the desire of something that has not revealed itself yet, whose strength though keeps the body tense and in check, under the feeling of a discreet melancholy. “2046” is a hotel room number, a year or a place where everything stays the same, where time is frozen. The fragmentary way in which the film is shot, can be set as a micrography of the meaning of the story itself: the vain hunt of memories that run away from us, due to the burdens that the time sets, due to the shock the reality creates after having dismantled all sort of idealisations, or due to the conscious decision to maintain internal warranties of destruction. It is a matter of fact that nobody can fully recall the sequence of the storyline. Yet, what can be agreed upon, is that “2046” should be put in the end of a Kar Wai Wong-marathon. That is mainly because the teeming and determinant manner in which the characters are constructed, can be realised as a conclusive anthem to that unceasing trial to recapture lost memories.

After watching any of Wong’s movies, I am most likely able to recall a bunch of lines, since they tend to leave an influential imprint on me. The tempting maze in which “2046” forced me in though, made it possible only for two lines to survive the venery of oblivion. The first one is “love is all a matter of timing”, which even if may sound cliche and predictable, is redefined by the particular attributes of the film. Those, make it sound more like a precursor of rage against the illusionary belief that things can work out as long as memories can be still recalled and so be kept fresh.The triumph of lyricism over narrative that characterises the film exhaust all possibilities of unrealistic expectations, and so it leaves only one way for the line to be appreciated: that constructed conditions which facilitate the emergence of new ‘timings’, are even more counterfeit than the aimless hunt of memories. The second line is that: “When you don’t take no for an answer, there is still a chance you’ll get what you want”, a line which could have been used in a range of different cinematographic occasions, with most possible those of gangster movies. That makes Wong’s tender romanticism seem more like a matter of pure realism due to the wholehearted devotion to the deepest recesses of human emotion. When it comes to real life though, it makes edges or conditions of uncertainty feel like the only resource and guarantee of erotic constancy.

To E. who similarly with Wong has the power to create luscious conditions of lust within me and leaves me with no chance of doubt, although our objective timing is a matter of the past.

Written and curated by Marianna Serveta Lensed by Elen Aivali Special thanks to Diana Kavallieri for the graphic designs of the blog.

Featuring “June” wrap sheer dress.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rocky Mountain Blues

When mentioning China, what can be easily brought in mind regarding the scenery, is large, exhausted-in-fumes cities, wrapped in the grey colours that are created when over-productivity and decay are necessitating each other. Yet, there are still some pieces of rural areas that are not only falsifying the above mentioned point, but their aesthetic strength can be even able to reset the rules of the nation’s standards of beauty. Two of them are Guilin and Yangshuo, the cities that make Avatar’s setup a product of realism instead of science fiction.

Guilin, a city in the northeast of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, has its borders determined by Li River and in her name she bears the smell of spring, as Guilin means “the forest of sweet Osmanthus”. Although the consequences of industrialism which rules the rest of China are evident into Guilin’s cruel poverty, the sweetness of these Osmanthuses is maintained by the smooth way the locals are leaning on whatever can bear their noon-daze and nap in the middle of the street. By their magic way to treat the insanity of the traffic as if it does not happen to them, staring at you in confusion if you reveal your panic. By the way they appreciate rain, creating the belief that they can hear the raindrops way louder than they hear the car honks.

Yangshuo country though, makes you continuously question how the locals can live in a place that alluring, and if they ever wonder what will happen if they neutralise that beauty, to the point that it will be hard for them to be thereafter surprised by anything else. It even makes you incessantly muse on what the thinking patterns and content of thought of the locals can be, if the first thing they face when they wake up is such orgasmic formations of their ground, of what they are simply supposed to walk on. Located one hour away from Guilin, Yangshuo may count as the city’s countryside, since it maintains the best parts of Guilin, yet detached from its character as a city. What is the most mesmerising aspect of it though, is that it is not only the river which shocks you with its blue-green colour, but the reflection of the massive karst peaks too, making you feel tiny under the spell of the nature. Moreover, such reflections seem to be summarising the Chinese tradition of building pagodas in the water, so that for the reflection of the temple to illustrate the extension of it when reaching out for the goddess of nature.

The dissolution of the rocks, is not only compelling in view, but interesting from a topographic and geologic standpoint too, since the cone-like hills of limestone karst are unique in China, although belonging to the tropical category of kegelkarst, found in other forms in Indonesia, Cuba, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Malaysia, Philippines and Vietnam. The dramatic formations that are surrounding the local community of Yangshuo though, are not only haunting because of the atmosphere they are creating but also because in fact, they are fossilised prehistoric sea floor sediments, shaped by the circulation of water. The sharpness of the scenery though, is smoothened by a variety of means. Not only by the soft touch of the water of the river, but by the fine curves that are shaped after so many years too. This is evident by the awe the “Moon Hill” peak inspires, which regardless of it’s violent angles, it contains a smooth circular shape, as if the moon is provided with a protector. Furthermore, the glorious rice fields that are all over the region, and are taken care by the Zhuang people and the minority groups throughout decades, are a pure reminder of their empirical wisdom and their strenuous labour which is only in consonance with the nature’s capabilities rather than the profit’s disastrous incentives. The precious ethnic minorities of the Zhuang, Yao, Miao and Dong people are living around the earth curves of the rice fields which are located on the mountains of 2400 feet, recognisable from the long distances due to their colourful dresses and their characteristic hats: occupied by their farming, or detected by the captivating smell of their cooking, or even after inviting you to sit by them when their sewing. That may be set as the last example of how the aggressive scenery is smoothened by the local populations’ ways of handling it, leaving the visitor with a melancholic aftertaste, after having seen that such a way of life is possible, and it actually brings the best out of both the earth and its inhabitants.

Devoted to M. whose enthusiasm every time even a tiny bit of my travel stories is revealed to her, feeds my longing for the collection of more memories. Or as Billie Holiday sings, to set off on a new journey, “Hide on these mountains, Gaze and catch the deep blues”.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=on4aO1nPIWM

Written and Photographed by Marianna Serveta Special thanks to Natalie Larsson, for making the scenery even more beautiful with her presence and devotion, and Diana Kavalieri for the graphic designs of the blog. Discreetly featuring Maddox top dress

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Spirits of Aeriform

I lost myself on a cool damp night I gave myself in that misty light Was hypnotised by a strange delight Under a lilac tree

I made wine from the lilac tree Put my heart in its recipe It makes me see what I want to see And be what I want to be

When I think more than I want to think I do things I never should do I drink much more that I ought to drink Because it brings me back you

Lilac wine is sweet and heady, like my love Lilac wine, I feel unsteady, like my love Listen to me, I cannot see clearly Isn't that she, coming to me nearly here?

Lilac wine is sweet and heady where's my love? Lilac wine, I feel unsteady, where's my love? Listen to me, why is everything so hazy? Isn't that she, or am I just going crazy, dear?

Lilac wine, I feel unready for my love Feel unready for my love

James H. Shelton, the lyricist of “Lilac Wine|, this spellbinding love- and grief prayer, goes back to 1925, referring to the author Ronald Firbank and the French fin-de-siècle style in his “Sorrow in Sunlight” storyline. Although many artists have included this song in their covers, among them Eartha Kitt and Elkie Brooks, even contemporary ones like John Legend and the Cinematic Orchestra, the two covers that are beyond comparison are those of Nina Simone and Jeff Buckley. This is because apart from the spiritual restlessness, what also characterises airiness is that it signifies delusion, insignificance, even madness. And that can be detected in the superficially similar, yet radically different way Simone and Buckley emotionally -and vocally- embraced the struggle of self-imposed oblivion, the reality which hides behind the lyrics’ meaning.

What Jeff Buckley succeeded, due to his rock ’n roll-soaked, sorrow-sentenced, anarchy-structured voice attributes, was to find a form which accommodated the mess included in the struggle for resisting memories. Although trying not to be biased by his lifestyle specialties which are displayed in his musical violence, -typical example of which, is the mysticism which characterises his striking single “Tongue”-, when it comes to Lilac Wine, he seems to stress more the parts that indicate delusion and hallucinating detachment. That refers to his tension when mentioning the atmospheric misty light of detachment from reality, the hypnotic delight of selective memory and the aggressive practices which compel the body to the spirit of relieflessness. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5PC68rEfF-o And then, Nina Simone. With her hoarse, gloomy, rasping voice, which bears all the meaning of the song in the very tremble of her pitch. With her violently mournful yearning in the lyric “Where’s my love?”. With the “black-classic music” features rousingly emphasising the vocal acrobatics of the lyric “Listen to me, I cannot see clearly”. With the existential dimension of the meaning which is merely focused, due to her mastery in letting emotion dictate what the arrangement should be. With the notorious aeriform of her vocal attributes that, as felicitously illustrated by Daphne Brooks in her book “Grace”: “would go belly deep or off key because the melody can’t carry all of her feeling. Her voice vibrates like a “motor running,” moving with a “rich, deep thrumming under the cracked surface.” It can be unpleasant at times, but it’s these “cracks” that allow the raw vulnerability within her voice to shine through.” The woman who has all her life sung injustice, stripping whichever orchestral arrangement down to her voice and the soft piano sound, emphasises the inequality which underlies every romantic relationship. Every violently emotional erotic subject, whose madness for sentimental tension rips apart any possibility of power-balance within his love stories. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LT38CIgRse4

With that said, Simone and Buckley’s covers cannot be compared to any other before or after, simply because the feeling of war that their stories and voices bear, is embodied in a way that necessitates its self-destructiveness; leaving no clues of the recipe of escape for the musical descendants.

To all the melodies that explain nothing, but thanks to them our feelings become explicable, and K., because if anyone, she can do better than Simone.

Written and Curated by Marianna Serveta Lensed by Elen Aivali Special thanks to Diana Kavalieri for the graphic designs of the blog

Featuring “Meadow” Lace Manteau

#nidoblog#nidodileda#spirits of aeriform#nina simone#jeff buckley#lilac wine#review#meadow#lace#manteau#ledasnest#collection

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Naked

“To see you naked, is to recall the Earth” There are some lines we all tend to agree with, and without having been given the chance to challenge them, they end up sinking in our subconscious, wrapped in the paralysing blanket of banality. Yet, the line mentioned above, is written by the man who also wrote “I am the immense shadow of my tears”, and that could be no-one else but Federico Garcia Lorca. The trite way of perceiving his first line, would have easily been the stodgy argument which holds that “we are all born this way”. But Lorca could not have meant just that, and until recently, that Mike Leigh’s brilliant sardonicism in his movie Naked (1993) emerged to me, I was not able to elaborate further on the argument either.

Despite the otherwise controversial aesthetics of Leigh, as if he has for long secretly mastered and carefully stored his skills on addressing grotesque romanticism with the most distorted tools of realism, he managed to illustrate the difference between nakedness and nudity. He managed to allegorically summarise in an 130 minutes masterpiece, how nakedness graciously reveals itself whilst nudity can only be placed on display. How the nude is lifetime sentenced to wear the heavy dress of spiritual homelessness, and never succeed to be naked. Two sexually frustrated men (David Thewlis and Gregg Cruttwell) represent the two poles of the dispute: the first roams around the cities, driven by an inexhaustible inner-aggression and an inability to conform to the rules of tenderness, and the second mentally and physically abuses women, being in a far more straightforward position of distorted reality. Since women’s reactions are chosen not to be problematised here, since that was not the point of the film either, when reasoning men’s handling, in the first case cruelty is appreciated as a cry of pain, yet at the second as a demonstration of power, constructed in aberrant terms.

Although a belligerent feeling which realism would easily inspire, characterises the film, -seen from the micrography of the cheap eroticism the permanently torn fishnet-tights of the female protagonist signal, to the terror of the cruelty-smelling and the darkness-grasped streets-, its urban existentialism should not be confused with other examples of radical realist cinematography. Bearing traces of Luc Godard’'s ‘Breathless’, in the way Thewlis is drifting by wit and instinct and fading through a ‘moral wasteland’, what is more felicitous to state is a poetic existentialism, periodically veiled under the most violent dimension of it. The characters are continuously interchanged in a Brechtian manner, as Mike Leigh uses to do, yet although he always creates caricatures whose possible trait is irritation, in this case, regardless their mood variations, characters are forced to generate and be soaked into irritation. In an interplay of sarcasm with nihilism, of artificiality with intellectual manipulation, where the characters are making fun of seeing their self-created hell falling down in pieces and being generated again, the naked flesh of feeling is absolutely reached. Yet, paradoxically, what is mostly brutal of all, is not the edges the characters are standing on, but the hysterical sounds of loneliness each and one of them finds himself within.The feature (and the condition which differentiates not only the protagonists with each other, but nakedness from nudity too) which makes Thewlis’s aggressive eroticism not to refer to or reinforce any sort of sterile hedonism, is his disillusioned, fully-conscious and intelligence identity as an outlaw. Not necessarily away from law, but away from social conventions.

That kind of nakedness, in consonance with Lorca’s quote, does not point to any wilderness of primitive reflections, but to a well-aimed, acknowledgement that when drain and naked, the violent curvy paths of real life, are better to be followed than any well-paved, secure path of constructed pleasure.

Written and curated by Marianna Serveta Lensed by Elen Aivali

Special thanks to Diana Kavallieri for the graphic designs of the blog

Featuring “Lily” Dress

#nidodileda#nidoblog#naked#mike leigh#federico garcia lorca#film review#ledasnest#collection#pleated dress#lily

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Her heart was made of liquid sunsets •

#nidodileda#nidoblog#bangkong#thailand#virginiawoolf#golden#hour#bangkokiansunsets#ancientmarket#buddisttemples

1 note

·

View note

Photo

You that in far-off countries of the sky can dwell secure, look back upon me here; for I am weary of this frail world's decay •

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I'll meet you in the maze •

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dancing shoes

She had them dancing shoes that never let her stay. And she had a war painted on her face. She was always afraid of simplicity because she was a prism, through which sadness could be divided into its infinite spectrum, and people would know. So she preferred to entrap herself into nets of complexity, setting impossible goals, hurting herself with her choices, laughing loudly- hysterically- violently.

But then laughter can’t but be irresistibly contagious. And there are others too that are born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world is mad. And madly broke into peals of laughter along with her, for a short while, joining her ride and poisoning fear away. Making the line which separates comedy and tragedy feel thiner. But she knew, because she has laughed before a clown early in life. And she was told that the joke loses everything when the joker laughs himself.

And so it was her habit to build up her laughter out of inadequate materials so that to dissolve itself. And although laughter is the shortest distance between two people and makes the rooms feel safer too, she was not to stay. Because she did not want them see within her prism. She wanted to keep them in good belly-shaking-tear-jerking-snot-producing laughs so that to silently put them shoes on and gracefully sneak out, making her absence feel milder and pain deafen itself in the sounds of her castanets. She had them dancing shoes and sounds of war in her laughter.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ViKFHj_4S88

To the girl who can ‘make the mountains swing, who can make me clip my wing and can get my tears to sing’. The one who cries when she’s given a flower as a friend and she has the whole world’s roads paved for her with lights.

Written and curated by Marianna Serveta Special thanks to Natalie Maldiv for modelling for me and Diana Kavallieri for the graphic designs of the blog.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Word-bound blues

Listen to Flaubert’s lament, in Madame Bovary: “Whereas the truth is that fullness of soul can sometimes overflow in utter vapidity of language, for none of us can ever express the exact measure of his needs, or his thoughts or his sorrows, and human speech is like a cracked kettle on which we tap crude rhythms for bears to dance to, while we long to make music that will melt the stars.”

Although Flaubert was supporting that the nature of speech is a rolling press that always amplifies one's emotions, in his contradicting quote mentioned above, words are viewed as feeble approximations of the rich and complex images and feelings desired to be given form and expression. I kept this quote within me this past week, processing and swirling it around in an attempt to figure out if it worths sharing with significant others, small details like this one, which at least made our heart melt for short periods of time. And in that case, how to do it by protecting this stimulation from the other’s possible lack of interest or inability of understanding.

Flaubert used to support that the faster the word (or stimulation) sticks to the thought, the more beautiful the effect is. Because this is how you keep it unpolluted from the damage of overthinking and the wounds the fearful projections regarding its consequences, may include. This is probably why, strangers or people who have experienced -or caused- limited moments of our pleasure, seem to appreciate in higher extent the simplicity we found beauty into, since their appreciation is based on our immediate explosive reaction and their phantasy of what lies behind such sentimental outburst. Higher, than those to whom our soul has revealed its ruined sides as well and can see how our gratitude of such a stimulus, is a matter of bruised enthusiasm which seeks its way to hope again.

In these terms, Flaubert’s quote can be alternatively interpreted as well. Exactly like Woody Allen’s movies praise sentimental fervour just because the way characters are created constitutes their inability to be a part of that intensity, here, the ones who are unable to express their insides are given the chance to praise that inability through language’s deficient nature. By its turn, such use of it as an exculpatory method for the ones who feel less, exposes the ones who feel more to the struggle of having to fit in words their chagrin, their ambition and their yearning, although they might themselves feel like strangers when using those tools of expression.

And exactly this view of the quote, summarises the consistent disappointment of facing the person for whom your phantasies, regarding the expectations of actualisation, are proved more satisfactory than the actualisation per se. Because regardless the presumption that the expectation will be rewarded with fulfilment, the actual touch makes you feel even more empty. By reason of it being felt as an expectations’ waste. Because you have not found the word yet where intention, expectancies, aspiration and desire can be crammed within. Because hearing is also a sense, which desires to be fed and pleased by words, but if those words are empty of meaning then it wishes to have wallowed in the magic of silence instead. And if silence is appreciated, then you regret for not having claimed it properly for the mutual desires to be heard within, before hearing the salacious scream of personal sentimental greed, which unfairly demands by the other what he cannot provide you with. Because feeling empty and lonely, is preferable when facing the maze in the middle of the street, than when facing your significant other. And all this is because if I ever contrive a word which will fit the magic of avidity and the fulfilment of hope, it will be after he has felt it when facing me.

By Marianna Serveta Lensed by Nikos Servetas// Special thanks to Diana Kavallieri for the graphic designs of the blog.

0 notes