#Golden Age of Opera

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

OTD in Music History: Russian composer, pianist, and mystically-inclined artistic visionary Alexander Scriabin (1872 - 1915) dies from blood poisoning in his Moscow apartment 110 years ago, at the age of 43. A few weeks earlier, Scriabin had begun complaining about the return of a very large and painful pimple on his right upper lip. (He had previously complained about an earlier iteration of this troublesome zit in 1914.) Scriabin’s condition gradually worsened, and about a week before his death he took to bed. Scriabin's doctor later recalled that an uncontrollable blood-borne infection began to spread across his face "like a purple fire,” and as Scriabin’s temperature soared up to 41 °C (106 °F), he grew delirious and eventually began to hallucinate. In those days, before antibiotics, there was little that medicine could offer him… In his early years, the young Scriabin wrote works that were heavily inspired by Frederic Chopin (1810 - 1849). Later on, however, he developed a very personal musical language inspired by his mystical inclinations which pushed tonality almost to the breaking point. Scriabin’s stock plummeted after the tragedy of his early death was further compounded by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 – only to rise once again, in the 1960s, when he was rediscovered by a new generation of music lovers who were fascinated by this most “psychedelic” of composers. PICTURED: A (c. 1910s) Russian real photo postcard showing the middle-aged Scriabin.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Golden Age Of Opera#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Alexander Scriabin

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cassius au Bellona

“I am Cassius Bellona, son of Tiberius, son of Julia, brother of Darrow, Morning Knight of the Solar Republic, and my honor remains”

V proud/happy with how this one turned out, definitely one of my favorites!

*Do not copy/steal/print/reupload to any platform.

#red rising#pierce brown#cassius au bellona#cassius#light bringer#book art#fan art#dark age#golden son#iron gold#red god#scifiart#space opera

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Philbin as Christine Daaé The Phantom of the Opera (1925) dir. Gaston Leroux

#christine daae icons#mary philbin icons#old hollywood icons#classic hollywood icons#golden age icons#hollywood icons#icons#film icons#movies icons#twitter icons#the phantom of the opera icons#1920s icons#movies#mary philbin#christine daae#the phantom of the opera#dir: gaston leroux

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐃𝐑𝐀𝐆𝐎𝐍 𝐀𝐆𝐄: 𝐓𝐇𝐄 𝐕𝐄𝐈𝐋𝐆𝐔𝐀𝐑𝐃 ➸ irulanne . the rook .

𝐌𝐎𝐔𝐑𝐍 𝐖𝐀𝐓𝐂𝐇𝐄𝐑𝐒 . 𝐄𝐋𝐅 . 𝐃𝐄𝐀𝐓𝐇 𝐂𝐀𝐋𝐋𝐄𝐑 𝐌𝐀𝐆𝐄 .

-`. template by @kanos . coloring . icons .

✧ ― 𝐓𝐀𝐆𝐋𝐈𝐒𝐓 (ask to be added or removed or interact 𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞!!):

@pavus, @wlwaerith, @shadowsofrose, @grapecaseschoices, @nokstella

@queennymeria, @risingsh0t, @carrionsflower, @leviiackrman, @griffin-wood

@confidentandgood, @aceghosts, @tommyarashikage, @shadowglens, @yharnams

@anoras, @theelderhazelnut, @florbelles, @celticwoman, @pinkfey

@kyberinfinitygems, @cloudofbutterflies92, @carlosoliveiraa, @shellibisshe, @adelaidedrubman

@lavampira, @capelizabeth, @socially-awkward-skeleton, @statichvm, @unholymilf

@aezyrraeshh, @imogenkol, @aceghosts, @full---ofstarlight, @ellierenae

#oc: irulanne#leg.ocs#leg.edits#*myedits#*ocedit#dragon age rook#da:tv#datv#my necromancer !!!!!!! my baby she’s here!!#teehee the first of the rooks !! so far i have 4 on standby for the fall the brainworms are brainwormingg jnhdkhnsk#spot the lucanne reference hehee twas a must to add something of luca in there he and lanna have had me in a CHOKEHOLD all a week hehe <3#colorings by cavalier remainn ICONIC andd SPEAKING OF WHICH THIS TEMPLATE GOLLY HOLLY#ty tyy orion this template was SOO good *screams* i had SO much fun working with it!!!!!#alsoo the official tarot for necromancers / mages / sidony from inky youll always be loved by MEE.#i am not sure if i want to go too much into her lore yet as its so early but the brainrot is brainrotting and i have SOO many thoughts!!#her history her lore how i see her interacting with the world and the world with her lanna's personality and her dynamic with luca AHHHH#*rattling the bars of my cage* FALL COME SOONER !!#lanna has had the braincell for the week STRAIGHT hdbjh <33#the high stakes tennis match between dragon show and dragon game brainrot hehe <33#ill hopefully have something for them too soooon I MISSED THEMM SO MUCHH#her lighthouse outfit + luca's outfit hehe couples that wear *almost* matching outfits thats soulmates or something (im normal) HEHEE#her name (hopefully the last time i change it djksncks) is inspired by i*rulan from d*une !!#an arcane prodigy entering her girlfailure era <33 girlbossed too close to the sun if u will JNDKJDSN#seemingly puts on an air of confidence but hides BIIIG time nervous wreck energy shes gonna take messing things up well i can feel it :')#i feel like a lot of clothes for her are sort of reminiscent of her time in the mourn watchers? all based on aspects of the dead??#like bones or etc?? but i also love that she could be a lightning learning mage with other magic so she takes to that more ethereal nature#to her style !! she’s also a BIG fan of the opera and was sort of praised as this golden child an arcane prodigy#the gifted kid to burnout adult pipeline she is really feeling it now 🥀🤧#hi hi moots if u read all that i am baking you cookies as we speak THERES SO MUCH MORE LOREE on her i have im screaming she’s everythingg#AHH IT WORKED IT POSTED <33 so so happy i can yell about her now HEHE 🥀💌

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

[4 May - Taurus]

Our beloved, sharp-mouthed, insecure fashion designer and tailor, Alois Flitmouse was first introduced as a minor side character in The Golden Age that Never Was and quickly ascended to significant ensemble character, Jack's first friend, and Anton's lover. He hides a past filled with horrendous familial and partner abuse, and is extremely protective of the people he loves.

I want you to be brave and tell me that you’ll lie to your boss and be my companion. But all I really want is a quiet place to be protected before it’s all over. I know it’s terribly uncouth for an omega to speak this way, to behave like this. I think you’ll find I’m rather terrible at being an omega, and I’m no longer interested in being good at it. I don’t want to be knotted by you. I don’t want your cock, though I’m sure omegas lose their minds over it. I don’t want anything except that sweet smile of yours and the promise that you won’t ever hit me.

Underline the Gold

The Golden Age that Never Was (fanfiction) - Alois was an original character, a snippy tailor and double agent for the resistance who gets abducted and taken to an Asylum. We discover that Anton is in love with him, Alois is in love with Anton, and Alois struggles to be friends with everyone due to a rough upbringing and deep insecurities.

Underline the Gold - Finally getting his own proper story in Underline the Gold, it becomes clear that Flitmouse is fighting for his life and fighting against severe mental disorders. His consistent strength and bravery, even in the face of his own despair, becomes the thing that Anton falls hard for from the very beginning.

Underline the Black - Flitmouse appears as a side character here, but a vital one, becoming the first omega to see Efnisien for who he is, and validate him exploring that further.

All the Loose Threads (abandoned) - Flitmouse's first side story, I ended up not continuing it not due to lack of interest, but because over time I became sure that Flitmouse deserved something that would get more eyes on it - an original story for example. That became Underline the Gold!

An exceptionally competent tailor and fashion designer with an excellent eye, Alois Flitmouse wears attractive clothing, is savvy about fashion, and interested in making clothing that is comfortable but also cutting edge and innovative. In Underline the Gold this extends to him sometimes adopting characters as his own personal models.

Flitmouse has hazel eyes, dark brown tufty hair that looks a bit like he's run his hand through it about 15 times, because he usually has. It often looks fashionable, but secretly he thinks it's very untidy. He wears black-rimmed glasses which suit his angular face.

Flitmouse is generally quite short and thin, and he has a fussy disposition. He's quick to cast judgement and even insult, despite possessing extremely thin skin himself.

A lot more politically savvy than he first appears, Flitmouse is usually quite well-read on the politics that concern him most, and able to debate at length about the things he cares about.

In The Golden Age that Never Was, we realise just how desperately Anton and Flitmouse are in love when Anton finds him locked away in the dark, in solitary confinement, dying in an Asylum. Flitmouse is overcome with emotion, not wanting to be seen by the love of his life, and Anton doesn't care what Flitmouse looks like, he's so overwhelmed by his lover still being alive.

In Underline the Black, Flitmouse comes through as a first suspicious and then fiercely protective omega when - in his first meeting with Efnisien - he goes from expecting the worst, to realising that Efnisien has been through the worst, and wanting to shelter him from it. At that point, he becomes ride or die for Efnisien, and Efnisien gains his first omega friend and ally.

In Underline the Gold, Flitmouse, going through a horrendous corrupted heat and in agony, refuses all medical intervention. As a last ditch attempt, Dr Temsen suggests that Flitmouse consume pheromones unconventionally - through saliva, or semen. To everyone's surprise, Flitmouse chooses semen, and is quite happy to do so, reminding everyone that he can be viscerally sensual when he wants to be.

Always a tailor. In Underline the Gold this became expanded to him being a master of the sartorial, working in haute couture. He's no longer a servant, but an exclusive fashion designer selling some of his items for thousands of dollars each.

Flitmouse's appearance doesn't generally change. He has more scars in Underline the Gold. But honestly, not that many more.

Flitmouse's dialogue is always quite sharp and verbally cutting. He can be extremely tender at times, which reveals just how deeply he cares for others, but there are layers of sharpness above it.

Flitmouse's dad is always abusive, and his ex is always Vadim, who was also abusive, and cheated regularly.

Flitmouse lets almost no one call him by his first name. You only know you've reached his inner circle when he permits being called Alois by you.

Flitmouse will use aspects of his abusive past as 'shock value' in conversation, but it's rare for him to genuinely bring up how much he was hurt by his upbringing.

Flitmouse was one of those characters I made because I needed some servant staff and I needed a reason for Jack Frost's 'costume' to come into existence. Enter Flitmouse, who actually had no first name when I first created him - he was literally a spontaneous creation while writing the story. I wanted his name to sound like his personality, sharp, agitated, quick, mousy, insecure.

Flitmouse was an interesting character to me. I rarely write characters who feel jealous to the degree that Flitmouse does, and that was an interesting thing to explore. I tend to think jealousy can be toxic depending on how it's expressed, and Flitmouse can definitely be toxic about it. I liked using Anton and Flitmouse as a good way of showing Anton's uncompromising relationship values, against Flitmouse's jealousy.

I've always had a soft spot for Flitmouse since the very first moment I locked him down. That's why he ended up getting Anton, who I also love.

Flitmouse is a bit different to many of the characters I write. He's not that introverted. He enjoys socialising with safe people and he loves gossip, and even in Underline the Gold he's often travelling out to the nearby towns to meet people and vendors even though he knows that's less safe than staying just with Anton. Flitmouse is probably one of the most social characters I've met outside of Eran who is an outright extrovert. Despite Flitmouse's general disposition, he's actually very good at being charming with strangers in his sharp, wry ways, and is good at making connections.

I was the person everyone came to, to have socks darned or the in-seams of pants mended. It was so useful, but when I said I wanted to take it further, they mocked me. I take after my father. But he was more of a blade than even me. When he mocked me, his words cut.

The Golden Age that Never Was

#birthday spotlight#alois flitmouse#the golden age that never was#underline the rainbow#underline the black#underline the gold#original writing#original works#omegaverse#fantasy#space opera#i've been rereading the golden age that never was to pull quotes#and i love flitmouse so muchhhhh

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Slam Opera (1936)

Top Hat (1935)

#buster keaton#fred astaire#grand slam opera#top hat#comedy#silent movies#1930s#tap dance#ginger rogers#golden age of hollywood#slapstick#hollywood#educational pictures

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve never seen this one before.

youtube

#The Phantom of the Opera#Lon Chaney#Mary Philbin#centennial anniversary#golden age of hollywood#silent film#me first and the gimme gimmes#the last drive in#season 7 premiere#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long-Haired Hare (Warner Bros, 1949) - dir. Chuck Jones

#Chuck Jones#warner brothers#bugs bunny#opera#Hollywood Bowl#1940s#classic cartoon#golden age animation

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

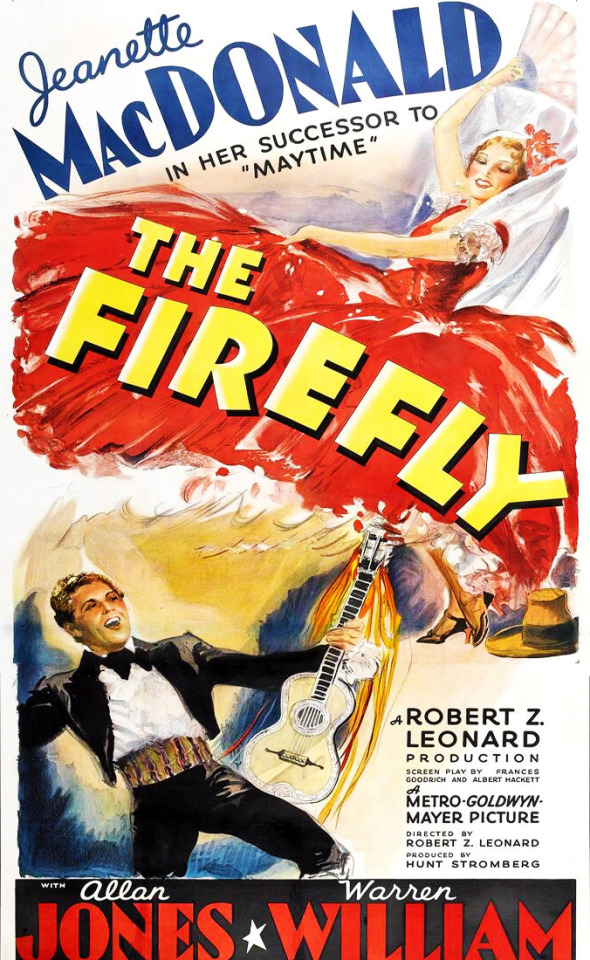

Jeanette MacDonald - The Iron Butterfly

Jeanette Anna MacDonald (born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on June 18, 1903) was an American actress best remembered for her musical films in the 1930s. MacDonald was one of the most influential sopranos of the 20th century, introducing opera to film-going audiences and inspiring a generation of singers. She became known as "The Iron Butterfly", for she was one of the most lady-like and beautiful women in Hollywood, but when it came to contracts, she was tough and kept unwanted advances in check, rarely making a misstep in her career.

She was the third daughter of Scottish-American parents and the younger sister to character actress Blossom Rock ( who was most famous as "Grandmama" on the 1960s TV series The Addams Family), whom she followed to New York for a chorus job on Broadway in 1919.

After working her way up from the chorus to starring roles on Broadway, she was casted as the leading lady in Paramount Studios' The Love Parade (1929), a landmark of early sound films. Despite making many successful films with Paramount, she next signed with the Fox.

MacDonald then took a break from Hollywood in 1931 to embark on a European concert tour, performing at the Empire Theater in Paris and at London's Dominion Theatre. She was even invited to dinner parties with British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald and French newspaper critics. She returned to Paramount the following year and made more films.

In 1933, MacDonald left again for Europe, and while there signed with MGM, which brought her together with Nelson Eddy. The pair made eight pictures together, including Maytime (1937), arguably the best musical of all time. From then on, they were forever known as America's Singing Sweethearts.

In 1943, she left MGM and began pursuing other interests. She made her opera debut singing Juliette in Gounod's Roméo et Juliette in Montreal at His Majesty's Theatre. After the war, MacDonald made two more films, but quit the movies altogether in 1949. The 1950s found MacDonald in the Las Vegas nightclub circuit, on television, in sold-out concert tours, in studio recordings, and on musical stage productions.

In her final years, MacDonald developed a serious heart condition. She died in Houston, Texas while awaiting heart surgery; she was 61 years old.

Legacy:

Won the Screen Actors Guild award for Maytime (1937)

Crowned as the Queen of the Movies in 1939 by 22 million filmgoers in a New York Daily News survey as presented by Ed Sullivan

Has 2 RCA Red Seal gold records (one for "Indian Love Call" (1936) and another for "Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life" (1935)

Has 1 RIAA gold record for Favorites in Hi-Fi (1959)

Was one of the highest-paid actresses in MGM in the 1930s

Listed by the Motion Picture Herald as one of America’s top-10 box office draws in 1936

Co-founded the Army Emergency Relief and raised funds on concert tours in 1941 to support American troops

Awarded an honorary doctor of music degree from Ithaca College in 1956

Named Philadelphia's Woman of the Year in 1961

Is the namesake of the USC Thornton School of Music built a Jeanette MacDonald Recital Hall built in 1975

Has a bronze plaque unveiled in March 1988 on the Philadelphia Music Alliance's Walk of Fame

Honored with a block in the forecourt of Grauman's Chinese Theatre in 1934

Co-wrote an autobiography, Jeanette MacDonald Autobiography: The Lost Manuscript, in the 1950s and which was eventually published in 2004

Honored as Turner Classic Movies Star of the Month for March 2006

Has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame: 6157 Hollywood Blvd for motion picture and 1628 Vine Street for recording

#Jeanette MacDonald#The Iron Butterfly#Opera#Silent Films#Silent Era#Silent Film Stars#Golden Age of Hollywood#Classic Hollywood#Film Classics#Old Hollywood#Vintage Hollywood#Hollywood#Movie Star#Hollywood Walk of Fame#Walk of Fame#Movie Legends#hollywood legend#movie stars#1900s#28 Hollywood Legends Born in the 1900s

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Belgian or French soprano Mariette Mazarin (1874-1953) sang the title rôle in the first American production of Richard Strauss‘ Elektra at the Manhattan Opera in New York on February 1st, 1910. It took more than twenty years till the next production of the one-act piece in New York: On December 3rd in 1932 the German soprano Gertrud Kappel (1884-1971) sang the first Elektra at the MET.

From Interpreters, by Carl Van Vechten:

SOMETIMES the cause of an intense impression in the theatre apparently disappears, leaving "not a rack behind," beyond the trenchant memory of a few precious moments, inclining one to the belief that the whole adventure has been a dream, a particularly vivid dream, and that the characters therein have returned to such places in space as are assigned to dream personages by the makers of men. This reflection comes to me as, sitting before my typewriter, I attempt to recapture the spirit of the performances of Richard Strauss's music drama Elektra at Oscar Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera House in New York. The work remains, if not in the répertoire of any opera house in my vicinity, at least deeply imbedded in my eardrum and, if need be, at any time I can pore again over the score, which is always near at hand. But of the whereabouts of Mariette Mazarin, the remarkable artist who contributed her genius to the interpretation of the crazed Greek princess, I know nothing. As she came to us unheralded, so she went away, after we who had seen her had enshrined her, tardily to be sure, in that small, slow-growing circle of those who have achieved eminence on the lyric stage.

Before the beginning of the opera season of 1909-10, Marietta Mazarin was not even a name in New York. Even during a good part of that season she was recognized only as an able routine singer. She made her début here in Aida and she sang Carmen and Louise without creating a furore, almost, indeed, without arousing attention of any kind, good or bad criticism. Had there been no production of Elektra she would have passed into that long list of forgotten singers who appear here in leading rôles for a few months or a few years and who, when their time is up, vanish, never to be regretted, extolled, or recalled in the memory again. For the disclosure of Mme. Mazarin's true powers an unusual vehicle was required. Elektra gave her her opportunity, and proved her one of the exceptional artists of the stage.

I do not know many of the facts of Mariette Mazarin's career. She studied at the Paris Conservatoire; Leloir, of the Comédie Française, was her professor of acting. She made her début at the Paris Opéra as Aida; later she sang Louise and Carmen at the Opéra-Comique. After that she seems to have been a leading figure at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels, where she appeared in Alceste, Armide, Iphigénie en Tauride and Iphigénie en Aulide, even Orphée, the great Gluck répertoire. She has also sung Salome, the three Brünnhildes, Elsa in Lohengrin, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, in Berlioz's Prise de Troie, La Damnation de Faust, Les Huguenots, Grisélidis, Thais, Il Trovatore, Tosca, Manon Lescaut, Cavalleria Rusticana, Hérodiade, Le Cid, and Salammbô. She has been heard at Nice, and probably on many another provincial French stage. At one time she was the wife of Léon Rothier, the French bass, who has been a member of the Metropolitan Opera Company for several seasons.

Away from the theatre I remember her as a tall woman, rather awkward, but quick in gesture. Her hair was dark, and her eyes were dark and piercing. Her face was all angles; her features were sharp, and when conversing with her one could not but be struck with a certain eerie quality which seemed to give mystic colour to her expression. She was badly dressed, both from an æsthetic and a fashionable point of view. In a group of women you would pick her out to be a doctor, a lawyer, an intellectuelle. When I talked with her, impression followed impression—always I felt her intelligence, the play of her intellect upon the surfaces of her art, but always, too, I felt how narrow a chance had cast her lot upon the stage, how she easily might have been something else than a singing actress, how magnificently accidental her career was!

She was, it would seem, an unusually gifted musician—at least for a singer,—with a physique and a nervous energy which enabled her to perform miracles. For instance, on one occasion she astonished even Oscar Hammerstein by replacing Lina Cavalieri as Salomé in Hérodiade, a rôle she had not previously sung for five years, at an hour's notice on the evening of an afternoon on which she had appeared as Elektra. On another occasion, when Mary Garden was ill she sang Louise with only a short forewarning. She told me that she had learned the music of Elektra between January 1, 1910, and the night of the first performance, January 31. She also told me that without any special effort on her part she had assimilated the music of the other two important feminine rôles in the opera, Chrysothemis and Klytæmnestra, and was quite prepared to sing them. Mme. Mazarin's vocal organ, it must be admitted, was not of a very pleasant quality at all times, although she employed it with variety and usually with taste. There was a good deal of subtle charm in her middle voice, but her upper voice was shrill and sometimes, when emitted forcefully, became in effect a shriek. Faulty intonation often played havoc with her musical interpretation, but do we not read that the great Mme. Pasta seldom sang an opera through without many similar slips from the pitch? Aida, of course, displayed the worst side of her talents. Her Carmen, it seemed to me, was in some ways a very remarkable performance; she appeared, in this rôle, to be possessed by a certain diablerie, a power of evil, which distinguished her from other Carmens, but this characterization created little comment or interest in New York. In Louise, especially in the third act, she betrayed an enmity for the pitch, but in the last act she was magnificent as an actress. In Santuzza she exploited her capacity for unreined intensity of expression. I have never seen her as Salome (in Richard Strauss's opera; her Massenetic Salomé was disclosed to us in New York), but I have a photograph of her in the rôle which might serve as an illustration for the "Méphistophéla" of Catulle Mendès. I can imagine no more sinister and depraved an expression, combined with such potent sexual attraction. It is a remarkable photograph, evoking as it does a succession of lustful ladies, and it is quite unpublishable. If she carried these qualities into her performance of the work, and there is every reason to believe that she did, the evenings on which she sang Salome must have been very terrible for her auditors, hours in which the Aristotle theory of Katharsis must have been amply proven.

Elektra was well advertised in New York. Oscar Hammerstein is as able a showman as the late P. T. Barnum, and he has devoted his talents to higher aims. Without his co-operation, I think it is likely that America would now be a trifle above Australia in its operatic experience. It is from Oscar Hammerstein that New York learned that all the great singers of the world were not singing at the Metropolitan Opera House, a matter which had been considered axiomatic before the redoubtable Oscar introduced us to Alessandro Bonci, Maurice Renaud, Charles Dalmores, Mary Garden, Luisa Tetrazzini, and others. With his productions of Pelléas et Mélisande, Louise, Thais, and other works new to us, he spurred the rival house to an activity which has been maintained ever since to a greater or less degree. New operas are now the order of the day—even with the Chicago and the Boston companies—rather than the exception. And without this impresario's courage and determination I do not think New York would have heard Elektra, at least not before its uncorked essence had quite disappeared. Lover of opera that he indubitably is, Oscar Hammerstein is by nature a showman, and he understands the psychology of the mob. Looking about for a sensation to stir the slow pulse of the New York opera-goer, he saw nothing on the horizon more likely to effect his purpose than Elektra. Salome, spurned by the Metropolitan Opera Company, had been taken to his heart the year before and, with Mary Garden's valuable assistance, he had found the biblical jade extremely efficacious in drawing shekels to his doors. He hoped to accomplish similar results with Elektra....

One of the penalties an inventor of harmonies pays is that his inventions become shopworn. A certain terrible atmosphere, a suggestion of vague dread, of horror, of rank incest, of vile murder, of sordid shame, was conveyed in Elektra by Richard Strauss through the adroit use of what we call discords, for want of a better name. Discord at one time was defined as a combination of sounds that would eternally affront the musical ear. We know better now. Discord is simply the word to describe a never-before or seldom-used chord. Such a juxtaposition of notes naturally startles when it is first heard, but it is a mistake to presume that the effect is unpleasant, even in the beginning.

Now it was by the use of sounds cunningly contrived to displease the ear that Strauss built up his atmosphere of ugliness in Elektra. When it was first performed, the scenes in which the half-mad Greek girl stalked the palace courtyard, and the queen with the blood-stained hands related her dreams, literally reeked with musical frightfulness. I have never seen or heard another music drama which so completely bowled over its first audiences, whether they were street-car conductors or musical pedants. These scenes even inspired a famous passage in "Jean-Christophe" (I quote from the translation of Gilbert Cannon): "Agamemnon was neurasthenic and Achilles impotent; they lamented their condition at length and, naturally, their outcries produced no change. The energy of the drama was concentrated in the rôle of Iphigenia—a nervous, hysterical, and pedantic Iphigenia, who lectured the hero, declaimed furiously, laid bare for the audience her Nietzschian pessimism and, glutted with death, cut her throat, shrieking with laughter."

But will Elektra have the same effect on future audiences? I do not think so. Its terror has, in a measure, been dissipated. Schoenberg, Strawinsky, and Ornstein have employed its discords—and many newer ones—for pleasanter purposes, and our ears are becoming accustomed to these assaults on the casual harmony of our forefathers. Elektra will retain its place as a forerunner, and inevitably it will eventually be considered the most important of Strauss's operatic works, but it can never be listened to again in that same spirit of horror and repentance, with that feeling of utter repugnance, which it found easy to awaken in 1910. Perhaps all of us were a little better for the experience.

An attendant at the opening ceremonies in New York can scarcely forget them. Cast under the spell by the early entrance of Elektra, wild-eyed and menacing, across the terrace of the courtyard of Agamemnon's palace, he must have remained with staring eyes and wide-flung ears, straining for the remainder of the evening to catch the message of this tale of triumphant and utterly holy revenge. The key of von Hofmannsthal's fine play was lost to some reviewers, as it was to Romain Rolland in the passage quoted above, who only saw in the drama a perversion of the Greek idea of Nemesis. That there was something very much finer in the theme, it was left for Bernard Shaw to discover. To him Elektra expressed the regeneration of a race, the destruction of vice, ignorance, and poverty. The play was replete in his mind with sociological and political implications, and, as his views in the matter exactly coincide with my own, I cannot do better than to quote a few lines from them, including, as they do, his interesting prophecies regarding the possibility of war between England and Germany, unfortunately unfulfilled. Strauss could not quite prevent the war with his Elektra. Here is the passage:

"What Hofmannsthal and Strauss have done is to take Klytæmnestra and Ægisthus, and by identifying them with everything evil and cruel, with all that needs must hate the highest when it sees it, with hideous domination and coercion of the higher by the baser, with the murderous rage in which the lust for a lifetime of orgiastic pleasure turns on its slaves in the torture of its disappointment, and the sleepless horror and misery of its neurasthenia, to so rouse in us an overwhelming flood of wrath against it and a ruthless resolution to destroy it that Elektra's vengeance becomes holy to us, and we come to understand how even the gentlest of us could wield the ax of Orestes or twist our firm fingers in the black hair of Klytæmnestra to drag back her head and leave her throat open to the stroke.

"This was a task hardly possible to an ancient Greek, and not easy even for us, who are face to face with the America of the Thaw case and the European plutocracy of which that case was only a trifling symptom, and that is the task that Hofmannsthal and Strauss have achieved. Not even in the third scene of Das Rheingold or in the Klingsor scene in Parsifal is there such an atmosphere of malignant, cancerous evil as we get here and that the power with which it is done is not the power of the evil itself, but of the passion that detests and must and finally can destroy that evil is what makes the work great and makes us rejoice in its horror.

"Whoever understands this, however vaguely, will understand Strauss's music. I have often said, when asked to state the case against the fools and the money changers who are trying to drive us into a war with Germany, that the case consists of the single word 'Beethoven.' To-day I should say with equal confidence 'Strauss.' In this music drama Strauss has done for us with utterly satisfying force what all the noblest powers of life within us are clamouring to have said in protest against and defiance of the omnipresent villainies of our civilization, and this is the highest achievement of the highest art."

Mme. Mazarin was the torch-bearer in New York of this magnificent creation. She is, indeed, the only singer who has ever appeared in the rôle in America, and I have never heard Elektra in Europe. However, those who have seen other interpreters of the rôle assure me that Mme. Mazarin so far outdistanced them as to make comparison impossible. This, in spite of the fact that Elektra in French necessarily lost something of its crude force, and through its mild-mannered conductor at the Manhattan Opera House, who seemed afraid to make a noise, a great deal more. I did not make any notes about this performance at the time, but now, seven years later, it is very vivid to me, an unforgettable impression. Of how many nights in the theatre can I say as much?

Diabolical ecstasy was the keynote of Mme. Mazarin's interpretation, gradually developing into utter frenzy. She afterwards assured me that a visit to a madhouse had given her the inspiration for the gestures and steps of Elektra in the terrible dance in which she celebrates Orestes's bloody but righteous deed. The plane of hysteria upon which this singer carried her heroine by her pure nervous force, indeed reduced many of us in the audience to a similar state. The conventional operatic mode was abandoned; even the grand manner of the theatre was flung aside; with a wide sweep of the imagination, the singer cast the memory of all such baggage from her, and proceeded along vividly direct lines to make her impression.

The first glimpse of the half-mad princess, creeping dirty and ragged, to the accompaniment of cracking whips, across the terraced courtyard of the palace, was indeed not calculated to stir tears in the eyes. The picture was vile and repugnant; so perhaps was the appeal to the sister whose only wish was to bear a child, but Mme. Mazarin had her design; her measurements were well taken. In the wild cry to Agamemnon, the dignity and pathos of the character were established, and these qualities were later emphasized in the scene of her meeting with Orestes, beautiful pages in von Hofmannsthal's play and Strauss's score. And in the dance of the poor demented creature at the close the full beauty and power and meaning of the drama were disclosed in a few incisive strokes. Elektra's mind had indeed given way under the strain of her sufferings, brought about by her long waiting for vengeance, but it had given way under the light of holy triumph. Such indeed were the fundamentals of this tremendously moving characterization, a characterization which one must place, perforce, in that great memory gallery where hang the Mélisande of Mary Garden, the Isolde of Olive Fremstad, and the Boris Godunow of Feodor Chaliapine.

It was not alone in her acting that Mme. Mazarin walked on the heights. I know of no other singer with the force or vocal equipment for this difficult rôle. At the time this music drama was produced its intervals were considered in the guise of unrelated notes. It was the cry that the voice parts were written without reference to the orchestral score, and that these wandered up and down without regard for the limitations of a singer. Since Elektra was first performed we have travelled far, and now that we have heard The Nightingale of Strawinsky, for instance, perusal of Strauss's score shows us a perfectly ordered and understandable series of notes. Even now, however, there are few of our singers who could cope with the music of Elektra without devoting a good many months to its study, and more time to the physical exercise needful to equip one with the force necessary to carry through the undertaking. Mme. Mazarin never faltered. She sang the notes with astonishing accuracy; nay, more, with potent vocal colour. Never did the orchestral flood o'er-top her flow of sound. With consummate skill she realized the composer's intentions as completely as she had those of the poet.

Those who were present at the first American performance of this work will long bear the occasion in mind. The outburst of applause which followed the close of the play was almost hysterical in quality, and after a number of recalls Mme. Mazarin fainted before the curtain. Many in the audience remained long enough to receive the reassuring news that she had recovered. As a reporter of musical doings on the "New York Times," I sought information as to her condition at the dressing-room of the artist. Somewhere between the auditorium and the stage, in a passageway, I encountered Mrs. Patrick Campbell, who, a short time before, had appeared at the Garden Theatre in Arthur Symons's translation of von Hofmannsthal's drama. Although we had never met before, in the excitement of the moment we became engaged in conversation, and I volunteered to escort her to Mme. Mazarin's room, where she attempted to express her enthusiasm. Then I asked her if she would like to meet Mr. Hammerstein, and she replied that it was her great desire at this moment to meet the impresario and to thank him for the indelible impression this evening in the theatre had given her. I led her to the corner of the stage where he sat, in his high hat, smoking his cigar, and I presented her to him. "But Mrs. Campbell was introduced to me only three minutes ago," he said. She stammered her acknowledgment of the fact. "It's true," she said. "I have been so completely carried out of myself that I had forgotten!"

August 22, 1916.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Mariette Mazarin#soprano#Conservatoire de Paris#Opéra Paris#Opéra-Comique#Richard Strauss#Elektra#Golden age of opera#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Philbin as Christine Daaé The Phantom of the Opera (1925) dir. Gaston Leroux

#christine daae icons#mary philbin icons#old hollywood icons#classic hollywood icons#golden age icons#hollywood icons#icons#film icons#movies icons#twitter icons#the phantom of the opera icons#1920s icons#movies#mary philbin#christine daae#the phantom of the opera#dir: gaston leroux

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#*screeches in spn rhymes* (via @dotthings)

#its themes/motifs are like what musical/rock opera enjoyers do when others complain something ''repeats'': YEAA BOII THAT'S MY JAM#dean winchester#spnedit#3.10#9.23#golden age tumblr

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

Buster Shows Italian Opera Singer Amelita Galli-Curci His Microphone

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vintage Sterling Silver Retro 1930’s 1940’s Style Old Timey Nostalgic Tabletop Golden Age of Radio Charm Pendant

Terrific sterling silver charm of an old-time tabletop radio! This wonderful charm is of a retro desktop radio also called “the wireless” from a bygone era. This cute, tiny charm will look terrific on your favorite charm bracelet or necklace!

#retro#radio#nostalgic#boombox#golden age#Boomers#Generation X#old timey#back in the day#back in my day#yesteryear#vintage charms#retirement gift#antique radio#radio show#radio broadcast#news#soap opera#fireside chats#FM radio#AM radio#broadcasting#grandparent gift#ayquebella#bygone#wireless radio#1930s#1940s

0 notes

Text

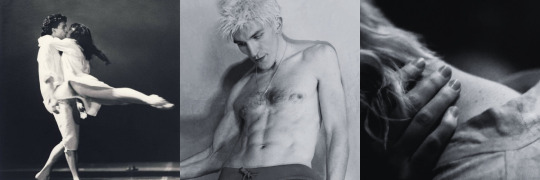

Étoile

summary | Aemond Targaryen has found himself a new star.

pairing | ballet master!aemond targaryen x ballerina!reader

tags | 18+, MINORS DNI! unprotected sex, oral (m), semi-public, slight dubcon, mirror sex, power imbalance, coercion, aemond’s kinda manipulative, slight age difference (reader is in her early 20s, Aemond is in his mid-30s)

wordcount | 4.6k

note | ah finally, some use for a decade and a half worth of ballet training 🙂↕️ i may or may not have written this after watching challengers, so aemond is very mildly inspired by tashi.

likes, comments, reblogs are much appreciated!

(divider by @aqualogia)

The air in the studio was humid with sweat as dancers glided through the floor accompanied by the soft tunes of the piano. Your limbs ached with exertion, your toes cramped in your pointe shoes, yet you continued, turning and leaping with the others as you performed the routine. Your ballet master kept a close eye on everyone, throwing out corrections to every dancer while he stood tall. Everyone was putting in the extra effort, dancing as though they were performing in front of the largest audience. There was a clear tension in the air, brought about by the Paris Opera Ballet’s newest ballet master, Aemond Targaryen.

He was tough, highly critical, and was known to send dancers out the door in tears, but he was one of the best. It was known among your peers he was looking to cast dancers for his repertoire, hence the reason why everyone was on edge during his class.

You couldn’t help the way goosebumps rose on your skin wheneve his eye fell on you, silently willing yourself not to mess up in front of the silver-haired man. You paid extra attention to the finer details of your movements, your mind running an extra mile to keep yourself in check.

Shoulders down. Shift that weight forward. Deep plié. Eyes on your spot, and turn.

Aemond gave you an approving nod as you successfully landed your quadruple pirouette, two extra than what you normally do. You kept your face neutral and composed, despite the glee bursting through your chest. A nod was a high praise in the ballet world, even more so from the stoic Targaryen, and you mentally patted yourself on the back for not falling on your face. Perhaps he would consider you for a role, one where you wouldn’t be lost in the mass of tutus and other dancers in the background. You were a coryphée, second to last in the company's hierarchy, and you had been desperate to rise through the ranks and prove yourself to your superiors. With the arrival of the young ballet master, whose good eye kept shifting towards you as you continued to dance, you had a good feeling your golden opportunity would soon fall into your lap.

Two claps echoed through the studio, cutting through the soft music of the piano. You halted your movements, turning to your ballet master who had paused your rehearsal.

“Not quite, try that again,” he ordered. You and your dance partner, Tomás, returned to your previous position, moving through the choreography to Aemond’s direction as the piano started once more. You were both slick with sweat, breaths equally panting as you continued your rehearsal for Le Parc.

It was a classic piece of the Paris Opera Ballet, a crowd favorite, and you had been bestowed the honor of performing the piece after being cast by the Targaryen himself. It was safe to say the rehearsal wasn’t going well, after only having danced the first two minutes of the nine minute piece in the three hours you had been in the rehearsal studio. Both you and Tomás were under immense pressure, one that only grew with every dissatisfied look and a shake of the head from your ballet master. The danseur beside you was rumored to be up for a nomination to be the company’s next étoile– the star, top of the ballet food chain. One cannot simply climb the ranks through time and effort to be an étoile, they had to be chosen by one of the ballet masters, and what better chance would one have than getting chosen by the Aemond Targaryen himself? Hence the agitation Tomás emanated, its sticky heat rubbing off on you.

“Ah, come on,” your dance partner grunted, sighing when you had failed to grab his arms to be lifted from the air. The pianist stopped playing with another raise of a hand from Aemond, who stayed seated in his seat in front of the mirror. You mumbled an apology, anxiously looking to the silver-haired man who had stood up from his seat. He approached the pair of you, his stance intimidating as was his gaze when he regarded both of you.

“The preparation for the lift is all wrong, Tomás,” he reprimanded. Aemond gestured for the young danseur to step aside, taking his place. The ballet master gestured for you to repeat the movement, and obeyed. You took a step before jumping, turning mid-air before being caught into Aemond’s arms. His grip was tighter than Tomás, more sure. You felt safe while being lifted, your whole body pressed against his taut chest.

“You have to hold her tight. Keep her stable, yes?” Aemond emphasized. He continued to hold you flush to his chest with ease, showing Tomás the exact position he wanted you to to end in.

“How’d that feel?” The silver-haired man asked you, his hot breath fanning the side of your face. He carefully placed you back on your feet, keeping his hand on your waist until you were able to stand. Slightly flustered from thay singular touch, you timidly pushed back the loose strands of hair on your face to look at him.

“Uh, good! Pretty stable,” you squeaked. His touch left a warm imprint on your flesh, lingering even after Aemond walked back to his seat.

“Alright, now try it on your own,” the Targaryen urged. The music started back up, and you tried the lift again with Tomás. You earned a low ‘good’ from Aemond when you had done the lift a little more successfully with his guidance, though the difference in the men’s grip was evident.

You continued on with the rehearsal, flowing through the choreography with Tomás under Aemond’s watchful eye. He caressed his chin as he kept a close eye on your movements, signalling to the pianist to pause when either of you did a step not to his liking. With every partnering trick that came up, Aemond made sure to show Tomás, standing from his chair to turn, hold, and lift you before urging the younger danseur to try. About halfway through the piece, his grip on your body had grown familiar, with the way his large palm covered the expanse of your waist, his touch firm on your thigh, and the featherlight caresses on your arm.

After the endless corrections and directions from Aemond, he made you start from the top once more. You took slow breaths as you presumed your initial position, pacing yourself as you started off the dance with a few counts where danced alone. It was going smoothly, miraculously enough, but you must have jinxed yourself because as you shifted to turn, you felt it. A sharp pain shot up your ankle, making you stop and drop to the floor in an instant. You clutched your ankle, hissing in pain. In a blink of an eye, Aemond was by your side, kneeling beside you.

“Hey, hey, it’s alright. Let me see,” he urged, his tone now softer as he looked at you in concern. It was an old injury, a sprain from the start of your career that continued to haunt you now and then. You shook your head at the silver-haired man, before pushing yourself off the floor.

“It’s fine, Mister Targaryen. This always happens,” you reassured him, waving him off. Aemond stood back to his full height, gripping your elbow to steady.

“Are you sure?”

“Yup, I’m sure. Let’s continue,” you said, keeping the tone of your bright to reassure the silver-haired man before you. However, you could barely take a step forward without hissing in pain, your right ankle unable to bear the weight of your body. Aemond was quick to catch you before you stumbled, and you held onto both of his biceps. They were ridiculously firm under your touch, and if you weren’t in an immense amount of pain you would have ogled at the way they flexed underneath your palms.

“This won’t do, darling. I think this is enough for the day for the two of you,” Aemond sternly ordered, wrapping your arm around his shoulder to keep you stable.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” Tomás grumbled, frustrated with the interruption. Aemond’s eye shot up to the young man, his gaze sharp after hearing his complaint.

“Don’t give me that attitude when you can barely do a decent menáge. Now get the fuck out of my studio.”

You jolted at the sudden rise in Aemond’s voice, watching as Tomás practically shrunk in his skin, hurriedly turning around to grab his bags and leave the studio while the man beside you glared at the young dancer sharply. The moment the door shut behind Tomás, Aemond turned back to you, his gaze now rid of the harshness it had carried.

“Let’s get you to the therapy room, yeah?” He softly urged. When it had still been too mich for you to walk with his support, Aemond swiftly lifted you with his arms underneath your body, carrying you bridal style. Your face burned with embarrassment with having to be carried off by your strict, ridiculously hot ballet master this way, but he had been gentle with you.

Aemond stayed by your side as the physical therapist massaged the joint. His good eye watched you when your face contorted into one of discomfort when your ankle was rotated. You had thanked him profusely for his aid, and had tried to reassure him you were good to be left alone, but the silver-haired man stayed by your side silently, keeping a close eye on you.

You had been out of commission for three days, which you spent anxiously anticipating to be dropped from the role by your ballet master. You were done for, you decided. You had blown your chance, pathetically so in front of Paris Opera’s most influential ballet master.

As soon as you were cleared to return to rehearsals, you immediately jumped to your feet and practicing on your own. You went through the choreography over and over, finetuning your movements as you watched yourself in the mirror. It was late at night and you were the only one left in the building, or at least, you thought you were.

The door to the studio you occupied flew open, making you jump when the silver-haired man casually walked into the room. You stopped in your tracks, heart racing as he regarded you, seemingly unsurprised after finding you.

“You’re supposed to be resting,” Aemond said, his smooth voice cutting through the music you plugged into the speakers.

“The doctor cleared me for rehearsals, Mister Targaryen,” you explained, to which he only responded with a hum. His good eye ran over your form, which was only clad in a leotard and athletic shorts. Your hair was down, as it was supposed to be in Le Parc, and your face was flushed from exertion, damp with sweat. Aemond took slow steps towards you with his hands clasped behind his back, meeting you in the middle of the room.

“You need to take better care of yourself, you know. A tear in your ligament is a tear forever,” he spoke, coming to tower in front of you. It was then you became insecure of your appearance, with your messy hair and sweaty face compared to his well-kept appearance. Your eyes stared into his good one, the other a cloudy white. He was incredibly handsome up close, this you realized, the sight of his sculptured jaw and aquiline nose making you visibly gulp. Your gaze dropped to his thin lips, which pursed before opening to speak once more.

“Yes, I know, Mister Targaryen, I’m sorry,” you muttered, tearing your gaze away to the floor. Two fingers placed themselves on the bottom of your chin, moving your head to look at him once more.

“Why are you apologizing?” Aemond asked. Your cheeks warmed as you stammered, unable to form a response. Truthfully, you were unsure why, perhaps it was for his disappointment for having hurt yourself, or for not having lived up to his expectations. The words you scrambled to find died on your lips when Aemond brushed a stray hair away from your face, before cupping you chin between his fingertips.

“I am only looking out for you. The Paris Opera may have some of the best rehab therapists under our roof, but some injuries just cannot be healed,” he said. Your eyes flickered to his cloudy eye, the rumors of his injury running through your mind.

You had heard in the past of the child protégé that was Aemond Targaryen, a young star destined for greatness. His family was descended from royalty and had been dancing in the King’s courts during the early formation of ballet. It was safe to say the young Targaryen was on his way to becoming one of the biggest stars in the ballet world, winning competitions left and right, receiving offers from the most prestigious ballet schools– Vaganova, Bolshoi, Joffrey, they all wanted him. The young danseur knew this was his legacy, to forge his name with the brightest stars in the ballet world. However, ballet was a deathly competitive sport, and dancers would do anything to climb the ranks, this Aemond had learned the hard way.

At 16, he had landed himself a spot as a finalist for the Prix de Lausanne, the most prestigious competition in the world, just a month before he was to fly off to Russia for training. It was the night before finals, he had been resting in his hotel room when a group of rowdy, inebriated dancers had knocked upon his door, wanting a glimpse of the famous silver-haired danseur. The details of the night remained unclear to the public to this day, but it was said that they had cornered the young Targaryen in his room, engaging in a scrapple that ended with Aemond rushed to the hospital, clutching his bleeding eye. That night, Aemond Targaryen’s dancing career met its tragic end. The ballet companies that once begged for him no longer wanted a scarred dancer who was blind in one eye, and his legacy had been reduced to nothing but a sad story.

And now, the silver-haired man stood before you, clutching your face as he studied your features. You were surely too close to each other to be considered appropriate, even more so when his free hand found its way to the dip in your waist, his warmth exuding through the fabric of your leotard.

“I don’t want to have to see you take your final bow before you reach the top,” he said lowly, his face subtly dipping an inch closer to yours. Your eyes slightly widened at his words, staring into his good eye for any sign of insincerity; you found none.

“You think I can reach the top?” you asked in disbelief, heart hammering in your ears. The corner of Aemond’s lips quirked upwards, his hand squeezing the flesh on your hip.

“Of course, you are one of the company’s most promising dancers,” he said, nodding lightly. You preened at his words, biting your lip as a big smile threatened to break out on your features. Your eyes fell to your fingers, fiddling with them as you turned shy at the ballet master’s high praise. The silver-haired man breathed out a chuckle at your reaction, his hand on your chin caressing the back of your head before settling on the nape of your neck.

“However,” he voiced, making you look back up at him. His face turned serious, making your own smile drop at his change of tone. “You have to go above and beyond to be nominated by your superiors. We have many talented dancers, many of whom are trying to climb the ranks, just like you. You have to make yourself stand out from the rest, do you understand?”

You nodded your head eagerly at him, your eyes displaying your sheer determination. “Yes, I understand, Mister Targaryen. I’m willing to do anything,” you said. There was a shift in Aemond’s eye when you uttered those words, the blues of his good eye brewing something darker. The grip on your waist turned tighter, shifting to rest on the small of your back as he pulled you in close.

“Anything?” he whispered.

“Y-yes, anything,” you replied. It was then you had begun to doubt your words, even more so when Aemond merely stared at you, his gaze analytic. A shudder ran up your spine when his eye dropped to your lips. A hum vibrates from his chest, and then he was pulling away from you, the warmth that engulfed you dissipating into a chill.

“Good. Now, why don’t we start from the top?” Aemond suddenly said, taking you by surprise. He raised his eyebrows at you, urging you to restart the music. You scrambled to where your phone was plugged into the speakers, restarting the music, before taking your starting position. Aemond positioned himself where the male dancer started, right in the center facing you. Your eyebrows furrowed while you did your first movements, clearly not expecting him to dance with you.

“You’re dancing with me?” you asked, confused. He merely smirked at you, watching you slowly move to the music towards him.

“Of course, you need to have a partner for this one, don’t you?”

The moment you touched him, Aemond started to move along with you. You flowed around him, soft and gentle. His moves were fluid, with textbook perfect technique and beautiful artistry. It was clear Aemond knew the choreography by heart, dancing along with you with ease. You subtly watched him through the mirror, amazement clear in your eyes. You were dancing with the Aemond Targaryen, being held and lifted by his strong hands. He danced like he had never left, flowing through the soft music while still clad in his boots and trousers.

“Don’t overthink it, little star, just move,” he encouraged, noticing how you were too focused on getting the movements right. With his advice, you willed yourself to let the tension in your shoulders go, gliding along the floor with Aemond’s guidance.

“There you go, well done.” Your face visibly brightened at his praise, meeting his eye in the mirror. A flush ran down from your cheeks down to your chest as he winked at you, a roguish smirk on his handsome features.

An incredulous smile broke out on your face as Aemond lifted you high up into the air with ease, still in disbelief with having found yourself in such a position. The dance was passionate, requiring great trust with your partner which you found with the silver-haired man with no trouble. You hadn’t felt this way when dancing with Tomás, nor with anyone really, with the way your muscles took a mind of its own and your body moved automatically with Aemond’s. To dance with the silver-haired man was something electric, filling you with an invigorating sensation as you sailed through the tunes of Mozart. You were lost in the music, you were lost in him, with the way his hands lingered a second too long after lifting you, his breath fanning over your face from your close proximity.

“Beautiful,” he whispered in your ear, snaking his arm around your waist when you leaned against him. Your heart raced as your chest heaved, from the exertion or from the adrenaline of dancing with the Targaryen man, you knew not. You missed the way Aemond’s eye raked down your form through the mirror, his gaze stuck on the sight of your nipples pebbled against the fabric of your leotard.

You stepped away from Aemond as you neared the climax of the piece, and it was then you faltered. You knew what was coming – the kiss. It was the highlight of Le Parc, with the dancers engaging in a long, passionate kiss as the man turned them around continuously. Your eyes were filled with uncertainty as you stood before Aemond, who was still watching your every move. Your fingers slightly trembled as you ran a hand down his body, and your breath shuddered when he did the same. You continued your movements around him, mind racing whether or not you should go through with the kiss. It was inappropriate, with him being your superior… but it was part of the choreography, was it not?

You faltered when you face to face before him, and for a second, you figured he wouldn’t want you to do it, but then you see it. A subtle dip of his head, and a flicker of his good eye towards your lips, waiting. You rose to the balls of your feet, planting your lips against his.

Aemond’s lips stayed on yours while your arms crossed at the back of his neck. His torso leaned back as you lifted your feet up the air, your whole weight leaned against his. You felt his lips move against yours as he spun you around, faster and faster around the room. You felt breathless and dizzy when he placed you back to the ground, but before you could continue with the choreography, Aemond’s hand grabbed the back of your neck to pull you back into his lips.

A gasp left your lips in shock, parting on instinct. Aemond’s tongue forced its way into the cavern of your mouth, the hot, wet muscle caressing your own. You pushed him away by the chest, but his stronger grip on you rendered you unable to pull away.

“Aem– Mister Targaryen, please,” you panted, trying to tear away the forceful hold on your waist. His other hand grabbed the hair on the back of your head, pulling on your damp tresses to make you look at him.

“You said you would do anything, wouldn’t you? Don’t you want to shine, my little star?” Aemond growled, before latching his lips on your sweaty neck. He groaned at the taste of your salty flesh, biting and sucking on the soft skin. You whimpered, your pulse thrumming dangerously against Aemond’s lips as you continued to push him off.

“I can make you shine. You’ll be first cast in any role you desire. You know I can make that happen for you,” he continued, pulling away to meet your teary gaze. The corners of your lips quivered downward when he caressed the side of your face, the touch giving you little comfort. Your whole body tensed when he pressed you flush into him, a stiffness poking into your thigh. He pressed a kiss to your forehead, swaying both of your bodies to the music that still continued to play through the speakers.

“You will be a star, my shining star. You want that, don’t you?” Aemond asked, his tone sticky sweet. As you met his sharp gaze, you weighed your options. He was right, he held the power to place you on top of one of the most prestigious ballet companies in the world, but you didn’t want to do it this way. You had the talent, and you wanted to prove your worth for the role, but he also had the power to take everything away from you. He can demote you, fire you, crush your entire career to nothing but dust. You couldn’t let that happen.

With a gulp and a soft nod, you shuddered when Aemond smirked down at you. His hand pushed your shoulder down, urging you to your knees. Shame coursed through you as you watched him unbuckle his dress pants to pull out his cock. A gasp left your lips when you were met with the sight of his impressive length. A throbbing vein ran the underside of his shaft, its cockhead flushed a deep red as it weeped a clear liquid. His hand guided the tip to your lips, but you kept them closed, turning your head away in refusal. With a frustrated grunt, Aemond’s free hand cupped your face, roughly turning it back to his cock. With your cheeks squeezed and your lips slightly parted, he slipped his length in. A delighted hum reverberated from your ballet master’s chest as he thrusted languidly into your mouth, adding inch by inch until he bottomed out. Your eyes squeezed shut when his tip hit the back of your throat, unable to resist the gag that squeezed his cockhead when it touched your uvula. Gathering your hair into a makeshift ponytail, Aemond barely gave you a chance to take a breath before setting a steady pace of his hips. Your hands gripped his muscular thighs to balance yourself, hot tears dripping down your cheeks.

“Use your tongue,” the Targaryen ordered. You complied obediently, even going so far as hollowing your cheeks to please him further. You were starting to resign to your faith, if this is what it took to make you an étoile, fuck it. Aemond threw his head back, groaning in delight at the added pleasure.

“Fuck, that’s it. My obedient little star,” he praised. His hips picked up their pace, pushing in and out of your mouth fast. The sound of your mouth taking his cock filled the studio, coupled with the music that continued to play from the speakers. His grunts continued to fall from his lips, his thrusts growing desperate as he neared his release. All of a sudden, Aemond pulled you off his cock. You coughed as you struggled to catch your breath, wiping off the pre-cum left on the side of your cheek. The flesh of your arm was gripped tight when the Targaryen pulled you to your feet, guiding you towards the mirror.

He turned you to face the reflection, your eyes meeting the sight of your flushed, teary face, lips swollen and cheeks stained with tears. Aemond caressed the exposed flesh of your arms softly, dipping his neck into the crook of your neck to suck a mark into the soft skin. You couldn’t help the way your eyes rolled back at the sensation, cursing your own body for its traitorous ways. His fingertips came up to hook into the straps of your leotard, pulling them down in one motion along with your bottoms. You crossed your arms instinctively to cover your parts, but Aemond was quick to stop you, grabbing your wrists to keep them by your sides.

“Don’t hide yourself from me now,” he scolded, tutting in mocking disapproval. You watched in the mirror as his eye took in your bare form hungrily, your body growing warm at his lingering gaze on your exposed breasts. His fingertips held a featherlike touch while they glided up the length of your arm, before grabbing hold of your plump tits firmly. A breath is hitched in your throat when he squeezed the soft flesh, a whine falling from your lips when he squeezed your perky nipples between his fingertips. You felt his cock jump behind you, hitting your rear. His touch traveled downwards, to your waist, your hips, and then cupping your sex with his large palm. A satisfied smirk spread on Aemond’s features when he pulled away his hand, the tips of his long fingers visibly wet and stick with your arousal when he spread them.

“Well, well, it seems like you’re enjoying yourself, little star,” he bragged, chuckling darkly when you meekly shook your head. “Deny yourself all you want, but your body will be thanking me by the end of this.”

“Please,” you pleaded. What you pleaded for, you didn’t know at this point, but you knew it wouldn’t get you anywhere good at that point. You let him bend you over, pressing your hands to the cool mirror to steady yourself. You waited with bated breath as you felt Aemond line himself with your slit, gasping when he began to breach. The slick from your saliva on his cock helped lubricate his length, coupled with the slick that dripped from your core against your will. Your jaw fell slack at the almost painful stretch of your walls, a small whimper falling from your lips when he finally bottomed out. Aemond let out a groan when his hips met your ass, his hand leaving your waist to deliver a smack to the plump flesh. His aquiline nose pressed into your cheek, breathing in the sweet scent of your warm, damp flesh. His pace was unforgiving from the start, forceful and aggressive. The silver-haired man’s gripped your breasts in his large hands to ground himself, reaching deeper and deeper into your walls.

“Ah, ‘s so good, baby,” Aemond praised, biting the shell of your ear as he groaned. Despite how much you fought your own urges, you barely registered when your lips started to emit soft sounds that echoed through the room. The music had already ended, the only sound left being the smacking of skin against skin, and the sounds coming from you and Aemond. You both watched the way his length disappeared into your cunt, your chest starting to grow speckled with a red flush the more your body grew heated. His cock drove into the rough spot that made your skin tingle, sending sparks up your spine despite your wishes. Your hips moved on their own accord, subtly meeting his thrusts. Aemond let out a breathy chuckle in your ear, planting a kiss to the side of your head.

“Yeah, you like it, don’t you? Like my cock, pretty girl?” You bit your lip as you nodded your head, squeezing your eyes shut in humiliation. The Targaryen tutted in your ear, grabbing your face to make you meet his gaze in the mirror.

“Look at me,” he ordered. You opened your hesitantly to meet his, though they threatened to close once more when his fingertips dipped down to circle your clit. Soft moans fell from your lips as he played with the bundle of nerves, the heat in your belly disgracefully growing the more he rubbed on your nub. “It’s okay, baby, no need to be ashamed. I’m making you feel good, aren’t I? Hm? Taking good care of my little star.”

Aemond was mindlessly rambling in your ear, his words making your stomach flip at the lewdness. His hips never faltered, snapping harshly into your ass continuously. The air in the room was hot and humid, droplets of sweat beading off of yours and Aemond’s skin. You whined as the heat in your belly rapidly grew upwards, rising to your chest. Your walls began to clamp down on Aemond’s cock, squeezing his length deliciously. He groaned into your ear, his fingertips still circling your clit hard.

“F-fucking hell, you gonna come?” The danseur asked. You grabbed his taut bicep in one hand, leaning your head back against his shoulder as a series of whiny ‘yesses’ fell from your lips. He continued to spurn you further, keeping his good eye on you when a particularly harsh thrust had you falling apart on his arms. The sight of your teary face scrunched up in pleasure, coupled with the sound of the sweet moan echoing through the quiet studio was what drove Aemond to his own release. He came with a loud grunt, spilling his hot seed into your walls. His strong grip around your waist held you up when your knees grew weak from the weight of your climax. Regaining your senses, you held onto Aemond for support, your eyes meeting his in the mirror. The imprint of your hands stained the glass, the gravity of the situation dawning on you as you stood in the aftermath. Shame washed over you for having debased yourself for leverage, and for finding pleasure in Aemond’s corrupted wickedness. The silver-haired man behind you held a smug look on his face, releasing a satisfied sigh before leaning his head against yours.

“Perfect.”

The cheers and applause of the crowd threatened to deafen your senses, yet it was a welcome sensation. You had taken your bow after a successful performance, standing with the numerous dancers on stage. Everyone waited with bated breath for the upcoming announcement, the air buzzing with equal excitement and nerves.

“Ladies and gentlemen, join us in congratulating the Paris Opera Ballet’s newest étoile,” the voice boomed through the theater. You turned to look at a nervous Tomás, giving him an encouraging squeeze of the hand. However, it wasn’t his name that was called, but yours.

The shock was visible on everyone’s features, as it was in yours. You felt their heated stares behind you while you stayed rooted to your spot, frozen in disbelief.

A tall figure walked onto the stage, holding a bouquet of flowers. The applause only thundered louder as the crowd is blessed with the sight of Aemond Targaryen, who was walking towards you with a smile on his face. Having been responsible for your promotion, he was the first to congratulate you, handing you the extravagant arrangement of flowers. He kissed both your cheeks respectfully, before whispering, “Congratulations, my little star. I trust I shall be seeing more of your graceful talents soon enough, yes?”

You looked up to meet his gaze, taking in the suggestive tone in his voice. It was then you realized what you had gotten to, what you had paid for greatness. Your lips widened to a sweet smile, giving Aemond a small nod, much to his satisfaction.

#bella writes ✍️#aemond targaryen x reader#aemond targaryen x you#aemond targaryen#aemond targaryen imagine#aemond targaryen smut#ewan mitchell#hotd x reader

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Claudia Muzio, nicknamed 'the divine' before Maria Callas, as Tosca at the Met (12/16/1918)

From More legendary voices by Douglas, Nigel:

She was born in a house on the Piazza del Duomo in the university town of Pavia, some twenty miles south of Milan, on 7 February 1889, and she was registered as Claudina Versati of unknown parentage. In fact her mother, a chorus singer, and her father, an operatic stage manager named Carlo Muzio, married at some later date, so that by the time their daughter’s career began she had been officially legitimised. She had a strange childhood, much of it spent backstage in the various opera houses where her father worked — all over Italy, at Covent Garden, where he was often engaged for the summer season, and at the Met, where he spent many of his winters. Most of her formal schooling took place in London, which gave her the ability, unusual in an Italian singer, to speak fluent English, and in her late teens she was sent back to live with relatives in Italy. She studied the piano and the harp in a music college in Turin, and subsequently moved to Milan where she continued her piano lessons with a lady named Annetta Casaloni.

Signora Casaloni was a most unusual piano teacher. She was at that time ninety years old, and in her younger days she had been a well-known operatic mezzo; indeed, back in 1851 she had created the role of Maddalena in RIGOLETTO. It is she who is usually credited with the discovery of Muzio’s voice, though Carlo Muzio had long predicted a great career for her in opera. ‘Since she began to toddle’, one journalist reported him as saying, ‘she has been in the wings watching my rehearsals. She knows all the dramatic roles, the lyric roles and the coloratura roles — nothing will come amiss to her.’ Certainly the extraordinary range of parts which Muzio did subsequently undertake, from the coloratura of Gilda in RIGOLETTO to the unbridled dramatic outpourings of Turandot, bears witness to his prescience, and few if any of her roles could be said to have ‘come amiss’.

Muzio’s début took place at Arezzo, near Florence, on 15 January 1910 as Massenet’s Manon, and within a couple of months she was singing Gilda and Traviata in Messina partnered by Tito Schipa— both of them had just celebrated their twenty-first birthdays. Muzio had no difficulty in establishing herself on the circuit of Italy’s smaller opera houses and it can clearly be taken as proof of her exceptional promise that only eighteen months after her début she was invited by the Gramophone Company in Milan to make her first two recordings. One of these, ‘Si, mi chiamano Mimi’ from LA BOHEME (the other was a passage from LA TRAVIATA), features on a Nimbus recital, NJ 7814, and it provides a fascinating glimpse of a great artist in the making. To set against the brilliant freshness of the tone there is a strange and not entirely attractive edge on the vowel sounds. They are very open and unrounded and in the upper register there is more than a hint of shrillness. The wonderful cornucopia of vocal shadings for which Muzio was to become famous is entirely absent, and although she does attempt an emotional gearchange as she glides into the big tune on ‘Ma quando vien lo sgelo’ — the phrase which to me is the litmus test for whether or not a soprano is worthy of this heaven-sent role — it is almost touchingly unsubtle. The same CD also offers us her recording of this aria made twenty-four years later, within a short time of her death. I shall return to it later; the difference between the two versions encapsulates a lifetime.

My strictures concerning this youthful recording would not be half so severe were it not for the standard which Muzio herself was to set as a mature artist, and the speed of her rise to prominence is a clear indication that even in those early days her virtues greatly outweighed her shortcomings. In the season of 1911-12 she reaped a rich harvest of success in Milan’s Teatro Dal Verme and by 1913 she was considered ready for her début in that holy of holies, La Scala. Her Desdemona there made a deep impression, and she was invited to repeat it the following year in Paris, where she was heard in rehearsal by Mr H. V. Higgins of the Covent Garden Syndicate. Mr Higgins surprised her by asking if she would come over to London the following week and sing Puccini’s Manon, which she did to the delight of one and all — ‘In turn voluptuous, seductive, defiant, passionate and tender, Mlle Muzio promises to be a great acquisition to Italian Opera,’ wrote the Pall Mall Gazette - and it is an indication of the short-term planning which characterised international opera at that time that she stayed in London to sing no less than six different roles at Covent Garden during the next ten weeks. Three times she stepped in as a last-minute replacement — once in OTELLO for Melba, who had to return to Australia because her father had been taken ill, once in LA BOHEME for Claire Dux who had eye trouble, and once in TOSCA for Louise Edvina, who was ‘indisposed’. For the TOSCA she found herself in formidable company — Antonio Scotti as Baron Scarpia and Enrico Caruso as Cavaradossi — but as one of the critics expressed it: ‘Edvina’s misfortune was Miss Claudia Muzio’s opportunity and right excellently she seized it. It was no light ordeal for a young and comparatively inexperienced artist to essay such a role in such circumstances, but Miss Muzio rose gallantly to the occasion and gave a very good account of herself indeed. Her acting and her singing were both really remarkably fine.’

The 1914 season at Covent Garden was an eventful one in many ways. At a Royal Command performance, in the presence of King George V and Queen Mary, a suffragette attempted to address the monarch, and when prevented from doing so locked her arms to a metal rail. According to The Daily Telegraph, when an attendant eventually succeeded in releasing her she struck him for his pains, and when she was bundled out of the building the crowd which had gathered outside ‘denounced her action in vigorous terms’. In sharp contrast to these unseemly goings-on the outstanding event of the season in an operatic rather than a political sense passed unnoticed. As Caruso took his curtain-call after the last performance of TOSCA no one could know that this was his final bow before the London public; nor indeed could anyone have guessed that after such a row of successes as Muzio had enjoyed, her first Covent Garden season would also turn out to have been her last. She was invited to return in 1915, but as things turned out it was to be five years before another season was mounted there, and inexplicably the post-war management never asked her back.